Oxford University Press's Blog, page 374

April 26, 2017

What we talk about when we talk about capitalism

For more than a century, capitalism has been the dominant planetary system for supplying people with, quite literally, their daily bread. It transformed our cultures and knit us together in a global network of buying and selling. But how do we understand it? How do we make sense of it? What do we talk about when we talk about capitalism?

Recently we did a study to track talk of capitalism over two hundred years and in three major newspapers in Britain, American, and the Netherlands. (The Dutch make a natural choice as co-originators of capitalism in Europe.) The idea has — at least historically — been linked to democracy: free markets and free speech; consumers and voters; the choices one makes in the shop, and the choices one makes at the ballot box. And so we’ll track them both together.

The answers are surprising. It is events, not philosophies, that drive the words into our daily lives. Talk of capitalism peaks at times of economic crisis. Talk of democracy peaks at times of war. More ominously yet, while the three nations began the twentieth century with distinct ways of linking the concepts together, they enter the twenty-first in the grip of an American-style neoliberal consensus: today we separate discussion of capitalism and democracy in ways never seen before.

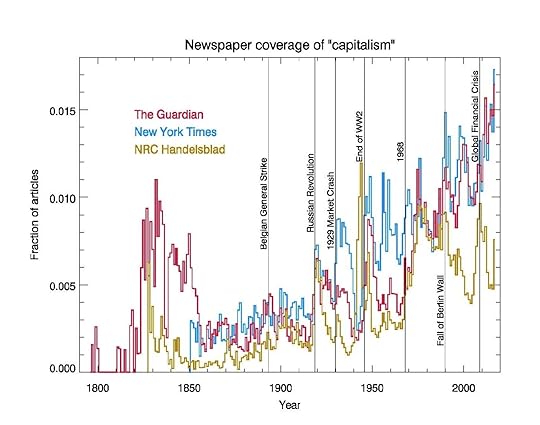

Figure One shows the raw data: the rates at which the word “capitalism” appears in the Guardian, the New York Times, and the (liberal) Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad.

Figure One: the fraction of articles in the Guardian, the New York Times, and NRC Handelsblad, mentioning the word ‘capitalism’ at least once by Simon DeDeo. Used with permission.

Figure One: the fraction of articles in the Guardian, the New York Times, and NRC Handelsblad, mentioning the word ‘capitalism’ at least once by Simon DeDeo. Used with permission.Capitalism, and talk about capitalism, is everywhere today. So it is surprising to see how little we talked about it at first. The British get there first: it is the Guardian, then the Manchester Guardian, covering the cotton factories and the strife between worker and owner. Yet by 1850 — and under new management — Yet by 1850, and under new management, the Brits are as sound asleep as the Americans and Dutch. The Dutch appear to joint in the conversation as well, but they, too, lose interest, showing only the slightest flicker of recognition, beginning perhaps in 1893, the year of Europe’s first general strike.

For all three nations, that long sleep ends in the Russian revolution of 1917. The event leaves a spike in all three archives, beginning a rise that continues today. At least four crises leave similar marks — the market crash of 1929, the end of World War II, the Fall of the Berlin Wall, and the global financial crisis of 2008. Like a ratchet with a slippery pawl, movement upwards is not uniform. Newspapers forget. But the forgetting is imperfect, and by 2017, capitalism (and its cognates) occur at rates ten times higher than a century before.

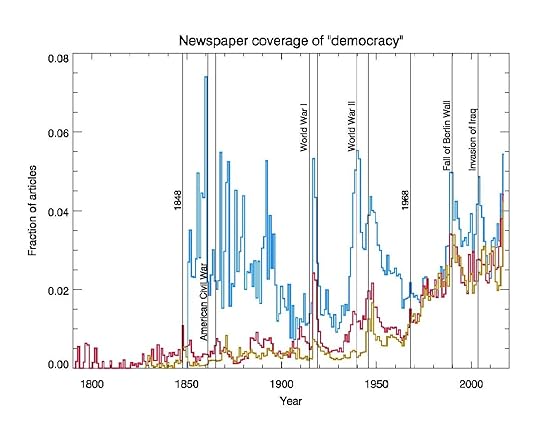

Figure Two: the fraction of articles mentioning the word ‘democracy’ at least once by Simon DeDeo. Used with permission.

Figure Two: the fraction of articles mentioning the word ‘democracy’ at least once by Simon DeDeo. Used with permission.As with capitalism, talk of democracy comes in bursts. Particularly in the Times, the pattern is clear: when the newspapers use the word, it’s usually around a war. The American Civil War, World War I, World War II, the 2003 invasion of Iraq: if you’re reading the paper and see the word a little too much, it often means that somebody, somewhere, is reaching for a gun. The fall of the Berlin Wall is perhaps an exception to this rule.

It’s hard not to reach for a cynical explanation of the association of democracy and war: in an era of mass mobilization, elites tell the public they’ll be dying for a system that belongs to them. Given that, the signs today are ominous indeed. Since the election of Donald Trump, talk of democracy in all three newspapers is at its highest level since the beginning of World War II.

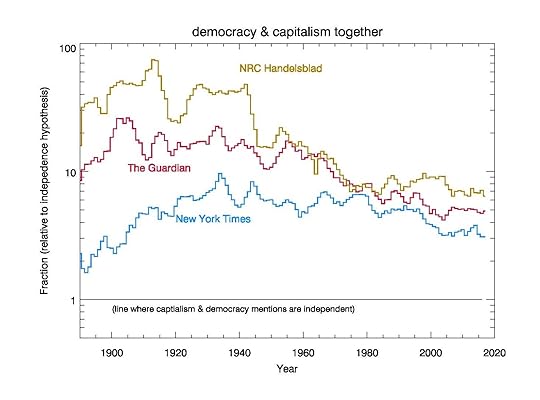

Figure three counts the times the words capitalism and democracy appear in the same newspaper article. And compares this to the number of times they would hypothetically appear in the same article if they were used independently.

Figure Three: The marriage of “capitalism” and “democracy”: the frequency of the two words appearing in the same article by Simon DeDeo. Used with permission.

Figure Three: The marriage of “capitalism” and “democracy”: the frequency of the two words appearing in the same article by Simon DeDeo. Used with permission.Now differences between nations are clear. For the Dutch, capitalism begins as an essentially political concept; it appears with “democracy” at rates almost a hundred times higher than chance. For the Americans, by contrast, the two are close to independent: how you get your bread, and how you get your president, are distinct. Linkages are made during the Depression of the 1930s, when the Times talks about a “present emergency” and philanthropists and college professors fret, but are forgotten with the rise of FDR.

The Guardian, of course, splits the difference between the European and American world-view. Yet by 1979, there is not much difference left to split: Dutch and British have converged on the American model. No paper ever treated the concepts as truly independent. But the days when capitalism and democracy were reliably linked are over by the end of the Cold War. In the year of Brexit and Trump, the New York Times separated discussions about the two in a way not seen since the roaring twenties. NRC and the Guardian were not far behind.

The sins of one seem to encourage the sins of the other — populism and economic corruption, coastal elitism and perceptible inequality. If it is time to talk about the two worlds together again, as we did in the 1930s, that moment has yet to arrive. If today’s readers of the Times, the Guardian, and NRC see their respective institutions safely into the twenty-second century, and our descendants make a similar plot, which way will these curves have gone?

As one man wrote in 1848: “all that is solid melts into air.” That man was Karl Marx, who at the very least understood that the need for bread, and the need for political dignity, could not be as easily separated as we do today.

I thank Wendy Carlin and Sam Bowles at the CORE Econ project, and Alex Ware of the Guardian Tech Team, for helpful conversations during the course of this work.

Featured image credit: architecture buildings city by pexels. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post What we talk about when we talk about capitalism appeared first on OUPblog.

So, you think you know Darwin?

Charles Darwin, the English naturalist, geologist, and biologist is known the world over for his contributions to the science of evolution, and his theory of natural selection. Described as one of the most influential figures in human history, his ideas have invited as much controversy as they have scientific debate, with religious, social, and cultural ramifications. Darwin’s theory of evolution was famously published in On the Origin of Species, but did you know that in order to formulate these ground-breaking ideas, Darwin also had some rather more unusual pastimes?

Did you know that Darwin published an entire book on the “action of worms”? He conducted various experiments to gauge their responses, including testing their hearing with the “deepest and loudest tones of a bassoon.”

Darwin also studied emotions in both humans and animals, with a tome investigating various expressions (which also included some of the earliest printed photographs), and three volumes solely on barnacles. Although he is generally known as a serious scientist, in his younger days Darwin was also a fearless adventurer, and undertook a five-year voyage around the world, with no previous experience of sailing.

If you think you know Darwin, take a look at some of his lesser-known writings, and think again…

Habits of worms

Although the subject matter may seem unusual, this text is actually a classic piece of Darwinian science. Darwin conducted many ingenious experiments designed to learn about earthworm behaviour and to test the powers of earthworm intelligence. He was attempting to prove that some degree of intelligence existed across the animal kingdom, even in the lowliest creatures. The book was published just six months before Darwin’s death, and shows the naturalist at his finest and most curious: Worms do not possess any sense of hearing.

They took not the least notice of the shrill notes from a metal whistle, which was repeatedly sounded near them; nor did they of the deepest and loudest tones of a bassoon. They were indifferent to shouts, if care was taken that the breath did not strike them. When placed on a table close to the keys of a piano, which was played as loudly as possible, they remained perfectly quiet.

“Mussels, Barnacles” by stux, CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

“Mussels, Barnacles” by stux, CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.Darwin on despair

Would you have thought of Darwin as a photographic pioneer? The Expressions of the Emotions in Man and Animals was one of the first books to feature illustrative photographs, with a series of heliotype plates. The study attempted to demonstrate the similarities of human psychology with animal behaviour, which would in turn provide further evidence for Darwin’s theory of evolution. The most difficult part was the “metaphysical” aspects of humans (emotions such as depression, hope, or devotion) which Darwin dealt with in particular detail:

If we expect to suffer, we are anxious; if we have no hope of relief, we despair…The circulation becomes languid; the face pale; the muscles flaccid; the eyelids droop; the head hangs on the contracted chest; the lips, cheeks, and lower jaw all sink downwards from their own weight.

Captain Barnacles…

Darwin is best known as a zoologist focusing on vertebrates, but he also had a substantial interest in marine invertebrates, and barnacles in particular. They were badly understood at the time, with muddled nomenclature, and hence made the perfect study. He published three volumes on The Sub-Class Cirripedia , describing the animals in a letter of 1849 as his “beloved Barnacles.” The novelty turned into monotony towards the end of this massive taxonomical project, with Darwin writing in 1852 “I hate a Barnacle as no man ever did before.” After this experience, Darwin never conducted any formal taxonomy again.

I believe the Cirripedia do not approach, by a single character, any animal beyond the confines of the Crustacea: where such an approach has been imagined, it has been founded on erroneous observations.

Darwin the adventurer

At the age of 22, Darwin set off on a round-the-world expedition on the HMS Beagle. It was a trip which was meant to take two years, but lasted almost five (from 27 December 1831 to 2 October 1836). Captain Robert FitzRoy was in need of an expert on geology to join the survey mission, and consequently the young Charles Darwin (who intended becoming a rural clergyman) was invited to join the circumnavigation. Darwin was a complete novice to life at sea and suffered badly from sea-sickness in the early days of the voyage. In a particularly amusing passage, he describes trying to mount his hammock:

I […] experienced a most ludicrous difficulty in getting into it; my great fault of jockeyship was in trying to put my legs in first. The hammock being suspended, I thus only suceeded in pushing [it] away without making any progress in inserting my own body. The correct method is to sit accurately in centre of bed, then give yourself a dexterous twist and your head and feet come into their respective places. After a little time I daresay I shall, like others, find it very comfortable.

Featured image credit: “Darwin, Natural History” by aitoff. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post So, you think you know Darwin? appeared first on OUPblog.

Whose Qur’an?

The Qur’an has emerged as a rich resource for liberation. Over the past several decades, Muslims across the world have interpreted the Qur’an to address the pressing problem of oppression, discerning in the text a progressive message of social justice that can speak to contexts of marginalization, from poverty and patriarchy to racism, empire, and interreligious communal violence. These justice-based interpreters of the Qur’an have produced a complex and sophisticated body of work. I won’t even attempt here to summarize their extensive scholarship. But the core, the conceptual heart of their work, can be summed up in two main points.

The first point is this: religious understanding and practice is never neutral. Religions don’t fall out of the sky. Rather, religions are shaped by people, and people are social beings: they are the products of environments conditioned by factors like race, gender, sexuality, class, language, culture, time, and place. Consider the position of women in patriarchal Muslim societies. Gender egalitarian interpreters of the Qur’an, such as the African American Amina Wadud and the Pakistani American Asma Barlas, have stressed that the Qur’an has historically been (and continues to be) interpreted by men. As a result, male experiences and subjectivities have shaped how normative gender relations are understood in Islam. Because of the patriarchal contexts in which the Qur’an has been interpreted, “man” has become the norm of Islamic thought, and – they argue – we need to deconstruct that claim by showing how different Qur’anic verses and rulings relating to gender have been understood through the particular, socially privileged gaze of men, which is anything but neutral and universal.

Photo by Shadaab Rahemtulla. Used with permission.

Photo by Shadaab Rahemtulla. Used with permission.And this brings us to the second point: whereas privileged groups have historically interpreted the Qur’an, it is imperative for marginalized communities to enter the interpretive circle, to partake in the task of producing normative Islamic thought and practice. In terms of gender, Wadud and Barlas have emphasized, time and again, that women need to participate fully in the process of interpretation, bringing their own lived experiences, subjectivities, and insights to understanding the Word of God. This, they argue, will produce a more inclusive and egalitarian expression of the Muslim faith. In other words, women can no longer be spoken about by men, whether those men are “conservative”, “liberal”, or otherwise. Instead, women must exercise agency by becoming the subjects of Qur’anic knowledge production.

Let’s shift to questions of class. Farid Esack, a South African anti-apartheid activist and liberation theologian, gives the example of Ramadan to tease out the classism of mainstream Muslim discourse. He takes issue with how numerous Muslims, particularly in the West, rationalize the purpose of fasting in the holy month: namely, to empathize with the poor. But this rationale, Esack points out, is anything but neutral. It’s based on an underlying assumption: that the Muslim who is fasting has a full stomach outside of Ramadan. That is, this discourse presumes an affluent, middle-class subject, one who does not experience the pangs of hunger and want throughout the rest of the year.

Interestingly, when you look up the fasting verse in the Qur’an, it simply states that the purpose of fasting is to attain “piety” (taqwa): “O you who believe! Fasting has been prescribed for you as it was prescribed for those before you, so that you may attain piety”. (Q. 2:183).

Photo by Shadaab Rahemtulla. Used with permission.

Photo by Shadaab Rahemtulla. Used with permission.Esack’s point here is not, of course, that the Qur’an is against charitable works. On the contrary, spending in the way of the poor is a major theme in the sacred text. Rather, the point is that the fasting verse, significantly, does not presume an affluent subject and audience. It is the class privilege, the lived experience of a minority that has projected a charitable discourse of empathy onto this verse, and it is Esack’s own lived experience of growing up in a poor, marginalized community in apartheid South Africa that enabled him to discern and call out that interpretive classism.

To sum up, while the first task is one of critical deconstruction – how is this commentator’s contextual baggage (gender, culture, ethnicity, time, place) influencing his exclusionary understanding of the Qur’an? – the second task is one of critical (re)construction, building a more just and inclusive understanding of the sacred text, and thus of Islam as a whole, by bringing everyone’s experiences to the table.

This is the message of Islamic liberation theology.

Featured image credit: The Holy Qur’an, by Amr Fayez. CC-BY-2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Whose Qur’an? appeared first on OUPblog.

April 25, 2017

Digging for the truth?: Mother and Baby Homes in Ireland

In the summer of 2014, reports that a ‘septic tank grave’ containing the skeletal remains of ‘800 babies’ was discovered within the grounds of a former home for ‘unmarried mothers’ in Tuam, County Galway, featured prominently as an international news ‘story.’ Interest in the issue was prompted by the tireless and tenacious work of a local amateur historian, Catherine Corless, whose research revealed that, during the 36 years between the Home’s foundation in 1925 and its closure in 1961, 796 children had died.

In June 2014, The Taoiseach (prime minister) Enda Kenny told the Dáil (Irish parliament), that the treatment of many unmarried women and their babies from the 1920s onwards was an ‘abomination.’ A Commission of Investigation was set up with a report due in 2018. Costing an estimated €21 million, it is clearly to be welcomed because issues, including high infant mortality rates in these Homes, warrants forensic analysis.

Connections can be made between the treatment of ‘unmarried mothers’ in the past and women’s lack of reproductive rights in contemporary Ireland. The Protection of Life During Pregnancy Act 2013 permits abortion in Irish hospitals, only under limited circumstances: if medical experts assess that a woman’s life would be endangered were the pregnancy to go full term, or, following instances of rape or incest, if she appears suicidal. As a consequence of the lack of reproductive rights in the Irish Republic, thousands of women still travel to England for abortions.

Turning to the past in 1927, five years after Irish independence, the report of the Commission on the Relief of the Poor identified responses to ‘unmarried mothers.’ It delineated ‘two classes’ of ‘unmarried mothers’: ‘those who may be amenable to reform’, so-called ‘first offenders’, and ‘the less hopeful cases.’ For the latter, a lengthy detention was recommended. For example, in circumstances where an ‘unmarried mother’, pregnant for a third time, applied for relief to a poor law institution, the Board of Health should have the ‘power to detain’ for ‘such a period as they think fit, having considered the recommendation of the Superior or Matron of the Home.’ In contrast, the treatment of those amenable to reform would focus on ‘moral upbringing’ and be characterised by the ‘traits of firmness and discipline, but also charity and sympathy.’ They would be dealt with by special institutions, a prototype of which was founded in 1922 by the Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary in Bessborough, Cork.

Being sent to a Mother and Baby Home had substantial disadvantages for women, as these institutions were designed to serve male interests and reinforce the power and social advantages of men. Whilst the secrecy inherent in the arrangement was likely to intensify women’s sense of shame and guilt surrounding the pregnancy, it preserved the anonymity of putative fathers, safeguarding male reputations. Although nuns were in charge of the day-to-day management of the establishments, it was men, particularly those laden with ‘symbolic capital’ such as priests and doctors, who referred women to the Homes and acted as gate-keepers.

Dáil Chamber by Tommy Kavanagh. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Dáil Chamber by Tommy Kavanagh. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Many women refused to go to such Homes because it meant, in effect, two years quasi-imprisonment. Many took ferries to England, hoping to spend a shorter period of time in a Mother and Baby Home and to have their children adopted. This specific type of Irish female migration had, moreover, featured as a recurring, if minor, theme in a number of official reports produced by the Irish government since the formation of the state in the early 1920s. Pre-occupation with the flight of the ‘unmarried mothers’ became especially more marked in the 1950s and 1960s, and this was reflected in the increased number of ‘repatriations’ with such women being sent back to Ireland.

Even in the 1930s, the Irish State was alert to the high mortality rate in the Mother and Baby Homes. The Department of Local Government and Public Health stated that the ‘abnormal death-rate’ amongst ‘illegitimate infants’ was a matter of ‘grave concern.’ There is also also suspicion that some deaths may have been bogus because of the practice of children in the Homes being taken to the United States by ‘adopters’.

Attitudinal changes began occurring in the 1970s. The Social Welfare Act 1973 ushered in the introduction of the Unmarried Mothers Allowance. The Unfair Dismissals Act 1977 ensured that women would not lose their jobs as a result of pregnancy, and in so doing provided some protection against social prejudice. The Status of Children Act, 1987 abolished the concept of illegitimacy and sought to equalise the rights of children including those born outside marriage. Such measures were due, in part, to the pressure applied by the embryonic women’s movement from the late-1960s.

Many women who spent time in these Homes are still alive and some of the allegations which have been made provide reasonable ground to believe that if not acts of torture, then acts of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment may have been committed. Similarly, some children born in these establishments are alive today. However, there is a need to remain alert to how an emerging narrative on the Mother and Baby Homes may now be seeking to relegate the issue to Ireland’s troubled past. It is vital, therefore, that social work practitioners and educators make the connection between the treatment accorded to ‘unmarried mothers’ during the twentieth century and women’s lack of reproductive rights today.

Featured image credit: Lackagh, Ireland by Richard Nolan. Public Domain via Unsplash

The post Digging for the truth?: Mother and Baby Homes in Ireland appeared first on OUPblog.

Are the microbes in our gut affecting how fast we age?

The collection of microbial life in the gut, known as the microbiota, may be considered an accessory organ of the gastrointestinal tract. It is a self-contained, multi-cellular, biochemically active mass with specialized functions. Some functions are important for life such as vitamin K synthesis, an essential molecule in blood clotting. Others are responsible for training and maintaining a healthy immune system or digesting indigestible food products such as insoluble fiber. Like other organs, the microbiota has physiologic reserve (i.e., the capacity to regenerate). It may be harvested from one host for transplant into another. It is thus no surprise that as our other organs age, such as our heart, brain, and kidneys, our gut microbiota ages, too.

Recently, our group has contributed to a growing body of evidence suggesting that the microbial ecology of the human gut differs according to estimated host biological age. A consistent finding between studies is a loss of gut bacterial diversity observed in human subjects of increasing biological age due to factors not otherwise explained by antibiotic use, diet, or host genetics. To date, this link between microbial diversity and biological aging has been reported in European and North American human cohorts. Animal models of frailty have made similar observations. The lifespan of at least one model organism of aging has been extended through fecal microbiota transfer. Overall, these studies implicate gut microbiota community remodeling as an aging-associated and aging-accelerating phenomenon.

The health consequences of losing microbial species in our gut are easy to speculate. The gastrointestinal tract is home to the largest and most diverse population of mutualistic organisms in the human body. Species of bacteria that inhabit the gut can vary widely in biochemical or metabolic function, producing a spectrum of nutrients that we are otherwise unable to produce ourselves. Groups of taxonomically disparate bacteria competitively exclude or repress bacteria with pathogenic behaviors that may harm the host and the microbial community at large. A sparse or shallow gut microbiota, one lacking in the richness of interacting and competing microbial species, is commonly considered unhealthy or unstable. A loss of gut diversity has been attributed to a number of disease states such as inflammatory bowel disease, metabolic syndrome or obesity, and Clostridium difficile (C. diff) infection.

This stability-through-diversity phenomenon may arise as a natural consequence of a Nash Equilibrium. In this theoretical model, one organism’s unilateral action fails to improve its standing over other organisms so long as the others maintain their normal, optimal behavior. A loss in the number of players in the equilibrium, such as what has been observed in biologically aging persons, may undermine these stabilizing forces leading to the growth of rare or low-abundance organisms. In time, this may contribute to age-related decompensation-like phenomena such as the translocation and invasion of normal flora into sensitive anatomic compartments such as the blood stream.

Beneficial Gut Bacteria by National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI). CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Beneficial Gut Bacteria by National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI). CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.How much change in diversity puts us at risk? This is, no doubt, a topic of on-going research and a question in need of answering. In a commentary published last month by the New York Times, Dr. Aaron Carroll cautions us to use our discretion when translating the results of the latest microbiota studies to human health. In particular, he cites a meta-analysis that pooled data from multiple studies assessing the association between gut microbial diversity and obesity in human subjects. The authors of the analysis found that obesity and markers of diversity were indeed significantly and negatively correlated in these studies, although the extent to which changes in markers of diversity reflected weight status was found to be weaker than what has been promulgated in the media and the scientific community.

We really do not know how much quantitative change in, say, the diversity of gut microbial communities is tolerated by the human body before the risk for problems emerges. At present, diversity markers and metrics are most useful to test qualitative hypotheses such as whether microbial diversity is or is not statistically associated with disease and when it is associated, whether the direction of the association is negative or positive. In the case of obesity in humans, harboring 2% less gut diversity (as observed in the meta-analysis) may lead to meaningful weight change or it may not. At present, we simply do not know. We do know, however, that obesity is a complex disease and a chronic one that develops over months and years, and a small yet sustained perturbation in the gut flora stretched over time may, indeed, lead to real, physiological effects such as involuntary weight gain.

Ultimately, the preliminary conclusions drawn by diversity metrics help scientists and physicians rule-in a potential role for the microbiota as justification to invest in confirmatory trials involving animal models and/or human subjects. A reasonably high potential for success is crucial to establish before risking the wellbeing of animals or human subjects in, say, an experimental fecal transplant or probiotic study that seeks to confirm a role for the microbiota in the etiology of a disease. Fecal transplant studies and related interventional human trials along with continued advancement in the accuracy and precision of sequencing technology will be key to translating quantitative changes in markers of diversity into medically useful data. It is critical that we define the clinical relevance of the human microbiota in future research studies for the development of clinical models of microbiota-mediated disease and subsequent, appropriate corrective therapy.

Featured image credit: Microscopic. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Are the microbes in our gut affecting how fast we age? appeared first on OUPblog.

Intercultural communication and considering a different perspective

With the ever-increasing rise of globalization, the need to communicate more effectively across cultures becomes all the more important. In a hyper-connected world, we need to learn how to better understand the perspectives of others, and how to make accommodations in conversations that support both parties being on the same page.

Simply put, different cultures see things differently. Contrastive cultural values and thought patterns can lead two people seeing the same picture to describe it in fundamentally distinctive ways. One person might discuss seeing a picture of clownfish, sea turtles, and a yellow tang with great focus on their physical characteristics; while the other person may highlight the coral reef in the background and talk about the relationships in the oceanic environment. What one person might see as being very apparent, the other might disregard.

In failing to notice the important “subtleties” in conversation, groups can turn simple misunderstandings in communication styles and thought processes into conflicts. Words, tone, thought process, and context to various degrees all play critical roles in intercultural communication.

To understand better how these factors come into play when communicating across cultures, here are some things to keep in mind when communicating across cultures.

Analytical thinking vs. Holistic thinking

Western society emphasizes analytical thinking, which pays more attention to focal objects and specific details, and not as much to what is going on in the environment. Analytical thinkers tend to believe that there are clearly definable, specific causes leading to the observed effects. For instance, if a woman receives a promotion at work, that woman would receive almost, if not all, the credit for the promotion. Her promotion was the result of her hard work. The outcome is a clear result of a cause and effect relationship.

Eastern societies typically process events holistically or within a large context. They assume that individual parts cannot be fully understood unless they are placed within the interdependent relationships. Since everything is connected, one entity cannot be fully understood unless we take into account how it effects and is affected by everything else. If a woman receives a promotion at work, her promotion could be viewed as the result of her hard work, the support of her colleagues, the current office environment, the beliefs of her managers, and so on.

Holistic thinkers tend to be dialectical thinkers and seek to reconcile opposing views as existing in a middle ground; meanwhile analytical thinkers would prefer to avoid a middle ground. Dialectical thinkers accept grey areas, assuming that things constantly change. In one study when two apparently contradictory propositions were presented to logical and holistic thinkers, the former polarized their views, while the latter accepted both propositions.

In failing to notice the important “subtleties” in conversation, groups can turn simple misunderstandings in communication styles and thought processes into conflicts.

High-context culture vs. Low-context culture

Members of high-context communication cultures (typically Eastern societies) rely on their pre-existing knowledge of each other and the setting to convey or interpret meaning. The personal characteristics of the parties involved and the nature of the interpersonal relationships are to be considered. Without the contextual bases, the speakers’ verbal messages are perceived to be pointless, awkward, or even deceitful. Explicit, direct messages are perceived to be either unnecessary or even threatening. The listener is to assume responsibility in understanding the message based on context and past knowledge.

In low-context communication cultures (typically Western societies) meaning is conveyed mainly through explicit words. The speaker should be direct in his or her communication, provide detailed information, and use unambiguous language. He or she does not assume pre-existing knowledge on the part of listener or expect the listener to consider heavily the setting. If a misunderstanding occurs, the sender of the message is often held responsible; he or she did not construct a clear, direct, and unambiguous message for the listener to decode easily.

Members of collectivistic cultures typically believe that courtesy often takes precedence over truthfulness to maintaining social harmony which is at the core of collectivist interpersonal interactions. As a result, members from collectivistic cultures may give agreeable and pleasant answers to questions when literal, factual answers might be perceived as unpleasant or embarrassing. For example, a Japanese man who is invited to a party but cannot go, or does not feel like going, would say yes, but then simply not go; a direct refusal could be seen as more threatening. The receiver of the message is expected to detect contextual clues and appreciate that the man did not directly refuse attendance.

Self-enhancement vs. Self-effacement

In individualistic, low-context communication cultures, socialization emphasizes the use of encouragement to promote individuals’ self-esteem and self-efficacy. Individuals directly express their desires and promote their self-images. They are open and direct about their abilities and accomplishments.

In collectivistic cultures, such as Japan and China, much of socialization emphasizes the use of self-criticism. Individuals use restraints, hesitations, modest talk, and self-deprecation when discussing their own abilities and accomplishments, as well as when responding to others’ praises. Self-effacement helps maintain group harmony because modesty may allow an individual to avoid offense. By playing down one’s individual performance and stressing the contribution of others, no one can be threatened or offended. The listener is expected to detect and appreciate the speaker’s modesty and intention to give more credit to others through self-effacement.

Elaboration vs. Understating

An elaborate style of communication refers to the use of expressive language, sometimes with exaggeration or animation, in everyday conversations. The French, Arabs, Latin Americans, and Africans tend to use an exaggerated communication style. For example, in Arab cultures, individuals often feel compelled to over-assert in almost all types of communication because in their culture, simple assertions may be interpreted to mean the opposite. The Arab tendency to use verbal exaggerations is considered responsible for many diplomatic misunderstandings between the United States and Arab countries.

The understated communication style involves the extensive use of silence, pauses, and understatements in conversations. The Chinese tend to see silence as a control strategy. People who speak little tend to be trusted more than people who speak a great deal; in understated style cultures, silence allows an individual to be socially discreet, gain social acceptance, and avoid social penalty. It can also save individuals from embarrassment. When conflict arises, using silence as an initial reaction allows people to calm down, exhibit emotional maturity, and take time to identify better conflict management strategies. Additionally, silence may indicate disagreement, refusal, or anger.

Featured image credit: Puzzle ball globe by Alexas_Fotos. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Intercultural communication and considering a different perspective appeared first on OUPblog.

Ireland in 1922 and Brexit in 2017

In 1922 most of the people of Ireland left the larger UK, but the Irish were divided. The UK today is leaving the larger European Union. The comparison gives grounds both for hope and for fear. The hope is for a speedy negotiation ending in agreed terms meeting the needs of the UK as the leaving state. The fear is for a secession of Scotland from England and Wales, similar to the secession of Ulster from the Irish Free State.

The Kingdoms of Ireland and Great Britain were united in 1801 by Acts of the Irish and British Parliaments. The Anglo-Irish Treaty of 6 December 1921, negotiated since the truce in July 1921, marked the start of the secession of Ireland – the nearest equivalent of Art 50 today.

The Irish Free State Constitution Act 1922 passed in Westminster on 5 December 1922, and the corresponding statute in Ireland, marked the formal legal separation of one state into two. The separation was completed in less than two years.

The Irish Free State Constitution Act 1922 foreshadowed the Great Repeal Bill contemplated by the UK Government’s White Paper of March 2017Legislating for the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union (CM 9446). It returned power to Irish politicians and institutions, it preserved UK law in Ireland where it stood at the moment before the Irish Free State left the UK of Great Britain and Ireland, and it made some changes to Irish law. Article 73 of the Irish Constitution of 1922 simply stated that the laws in force in Ireland at the time when the Union was dissolved were to “continue to be of full force and effect until the same or any of them shall have been repealed or amended by enactment of the Oireachtas” (the new Irish Parliament). As explained in the White Paper at para 2.5, the Great Repeal Bill will be similar in principle, but more complicated in practice. It will not only enable people to rely on rights in the EU treaties which can now be relied on directly, and convert directly-applicable EU law into UK law. It will also preserve all the laws made in the UK to implement EU obligations, and provide that historic case law of the Court of Justice of the EU shall have the status of binding precedents.

The British and Irish also took care to protect the reciprocal treatment of each other’s nationals, and to share public debt and pension liabilities.

The British and Irish also took care to protect the reciprocal treatment of each other’s nationals, and to share public debt and pension liabilities. The UK did not use the occasion to punish Ireland for leaving the UK, nor to deter other peoples of the British Empire from seeking independence.

The White Paper The United Kingdom’s exit from and new partnership with the European Union of February 2017 (Cm 9417) refers to 1922, explaining that the Common Travel Area (CTA) was linked to the establishment of the Irish Free State. The CTA is a special travel zone for the movement of people between the UK, Ireland, the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands. The effect of the arrangements between the UK and Ireland in 1922 is that, since then, the people of Ireland, both the Free State and the Republic, have enjoyed the freedoms of movement which are central to the EU: people, goods and services, and capital have generally moved freely between the UK and Ireland since 1922.

The British sought protection of fundamental rights for the minority in the new Irish Free State. Art 73 of the Constitution extended to the Irish Free State all the existing rights of individuals under UK law. But since UK law did not guarantee rights by means of a written constitution, the British feared that the Protestants might suffer discrimination under future Irish laws of the kind which the Irish Catholics had suffered under British legislation in the past.

The agreement between the UK and Ireland in 1922 foreshadowed the post War enthronement of human rights.

So, the Treaty of 1921 included that the Irish Free State would not enact any law discriminating on grounds of religion. The Irish Constitution of 1922 not only gave a constitutional guarantee to freedom of religion, but also to other British fundamental rights dating back to Magna Carta. They included rights to personal liberty, inviolability of the home, freedom of expression, freedom of assembly and more.

The agreement between the UK and Ireland in 1922 foreshadowed the post War enthronement of human rights. This facilitated the peaceful transfer of power to many British Overseas Territories, and a continuing, but different, close relationship between them and the UK. In 1950 the UK adhered to the European Convention on Human Rights. And from 1959 UK governments included guarantees of fundamental rights in the constitutions of Nigeria and other British Overseas Territories, most of which were to become independent, the latest being Hong Kong. Relations between the UK and the Republic of Ireland are exceptionally close to this day. Although the world is more complicated now, the arrangements made in 1922 should be a model for the UK’s future relationship with the EU.

There is a real fear of secession by Scotland. But, happily, there is not, between England and Scotland, the recent history of internal divisions, of coercion by the UK Government, and of the violent measures adopted in Ireland, that prevailed in 1922.

Featured image credit: “ Giants causeway, Belfast” by llee_wu. CC BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Ireland in 1922 and Brexit in 2017 appeared first on OUPblog.

April 24, 2017

Should firms assume responsibility for individuals’ actions?

VW may have taken a big step towards resolving its emissions scandal in the United States with its recent guilty plea (at a cost of more than US$4.3 billion), but its troubles in Europe are far from over. Luxembourg has launched criminal proceedings and more countries may follow after the European Commission made it clear it felt member states had not done enough to crack down on emissions test cheating.

It seems safe to assume that VW’s cheating was not the act of a single rogue engineer, but when scandals like this occur, where does the moral responsibility lie? Is it solely the responsibility of the individuals who developed and implemented the software? Or is the firm itself, which likely put pressure on employees in various ways, also to blame? If so, to what extent? And what does it mean to say that a business as an entity is morally responsible?

Is there a “corporate person”?

It has become common parlance to talk about how BP destroyed the Gulf of Mexico, or pharmaceutical companies misled doctors or banks were to blame for the global financial crisis. But the idea that corporations act as if they are human seems initially quite implausible. Although companies are composed of real people, there is hardly reason to believe that individuals who place themselves into structured groups create a new and separate human-like moral agent with its own beliefs and desires. Can we really identify a corporation or any other business entity as a moral agent that can intend actions and be held accountable for its decisions? Can it act autonomously, form moral judgments and respond in light of those judgments?

No guilt, no blame

Amy Sepinwall, a professor at the Wharton School, suggests that corporations themselves have no capacity for emotion or responsiveness to moral reasoning are therefore unable to experience guilt, and, as it makes sense only to blame those who can experience guilt, corporations do not qualify for moral agency. In other words, it is the individuals inside the corporation, not the corporation itself, who should take responsibility for actions taken in the name of a firm. This is supported by arguments put forward by David Rönnegard, a visiting scholar at INSEAD, and Manuel Velasquez, a professor of management at Santa Clara University, who insist that individual members of corporations are “autonomous and free.” Company-level policies and procedures may influence people in firms, but it is individuals who are ultimately responsible for their decisions and actions.

What then, does this view say about the role of corporate culture? If we were to scrutinise the banks, whose sale of US mortgage-backed securities sparked the global financial crisis, is it sufficient to attribute all the blame to the autonomous actions of greedy individuals or should we consider the culture that facilitated it contributed to the disaster? To what extent, if any, are there grounds for laying some of the responsibility in the hands of the organisation that allowed the misbehaviour to happen and company leaders like VW’s Martin Winterkorn who may have tacitly, if not actively, encouraged it?

The dangers of blaming the firm

There is a danger that by allowing a firm to take responsibility for wrongdoings, innocent people will be penalised and the individuals responsible for the misbehaviour will get off scot-free. According to Ian Maitland, a professor at the Carlson School of Management, University of Minnesota, holding corporations morally and legally responsible can encourage firms to create opaque organisations allowing individuals to act with impunity, effectively creating “a scapegoat which diverts legal responsibility from the executives, managers, and employees who have committed wrongful acts.”

In addition, rendering corporations liable to criminal punishment as collective entities can be seen to contravene the most fundamental principles of a liberal society. John Hasnas, a business professor at Georgetown University, notes that by punishing the firm, through fines or business restrictions, we are more likely to be punishing those innocent of wrong-doing, including employees, consumers and shareholders.

Meeting expectations

Taking an opposing view, others argue that a corporation has a voice of its own, distinct, if not different, from those of its members. It is this organisational voice which prompts Philip Pettit, a professor of Politics and Human Values at Princeton University, to insist that corporations are indeed fit to be held morally responsible, particularly in regard to actions that breach commonly shared expectations.

It is also worth considering the possibility that a firm may be morally responsible even if its intentions are not fully shared by all of its members, as suggested by Michael Bratman, a philosophy professor at Stanford University. This brings to mind banks as described by John Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath: “faceless monsters, something more than men …every man in a bank hates what the bank does, and yet the bank does it.”

This is not to suggest that individuals cannot be held responsible at the same time. It is fair, for example, to expect that a corporation should be held responsible for distributing contaminated food, while simultaneously arguing that employees who were negligent in the exercise of their duties should be held responsible for their part in the scandal as well.

The idea of corporate moral agency and whether corporations can be treated as individuals was first raised by Peter French, a philosophy professor at Arizona State University, in his 1979 paper, ‘The Corporation as a Moral Person.’ Although much has been written since this seminal work, the practical consequences of the issue have expanded and the debate continues to rage.

Common ground

Despite philosophical differences that will continue in the years to come, most scholars of business ethics agree that corporations should be doing more to create a culture where bad behaviour is neither condoned nor ignored, and where misdeeds are not covered up but are attributable to both individuals and organisational factors. Better appreciation of moral responsibility in firms will allow managers to structure internal incentives, rules and policies to achieve the economic objectives of firms in an ethical manner. It will also help in providing an appropriate external legal framework to encourage good business conduct.

A version of this post originally appeared on INSEAD knowledge.

Featured image credit: architecture bridge building by Pexels. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Should firms assume responsibility for individuals’ actions? appeared first on OUPblog.

Robert Penn Warren, Democracy and Poetry, and America after 2016

Born in 1905, Robert Penn Warren’s life spanned most of the twentieth century, and his work made him America’s foremost person of letters before his death in 1989. His literary prowess is evidenced by his many awards and honors that include three Pulitzer Prizes, one for fiction and two for poetry, so that Warren remains the only writer to have won them in these two major categories. The first of Warren’s Pulitzers was for All the King’s Men (1946), his epic novel loosely based on the Huey Long era in 1930s Louisiana. Several critics have named it America’s finest political novel, and I agree as a Warren scholar myself. In fact, I often thought of Willie Stark, a fraudulent populist from an unnamed southern state at the center of Warren’s novel, during the election cycle of 2016.

Although Warren’s earlier recognition was largely in terms of his fiction, his later reputation is posited more often on his poetry and nonfiction. In the contexts of this later work, as well as of the recent election year, a more positive political text may be found in the expanded version of his 1974 NEH Jefferson Lecture for the Humanities published as Democracy and Poetry (1975). Rereading it in this historical moment, I was struck once more by Warren’s prescience concerning politics in America. He is willing to admit our political failures, including the then recent Watergate fiasco, yet he is still able to project a vision for the preservation of American democracy even in the face of future scandals and impeachments.

In his brief “Foreword” to Democracy and Poetry, Warren narrows the universal terms of his title and defines the relation of the self to its society. By democracy, he means the political balance of the individual and the state that has eventuated during American history. Poetry here refers to serious American literature, in prose as well as in verse, which connects the individual writer and the national readership within our literary heritage. Most of this prefatory matter considers a third definition though, that of selfhood. For real democracy and for meaningful literature, Warren believes that a fully developed individual is the prime necessity. In Warren’s view, this sort of evolved self must realize a felt principle of unity defined by personal responsibility exercised over time.

For real democracy and for meaningful literature, Warren believes that a fully developed individual is the prime necessity.

Warren divides his consideration of democracy and poetry into two sequential essays, “America and the Diminished Self” and “Poetry and Selfhood.” The first essay reviews the history of our creative literature as a harsh indictment of the successive failures that have plagued the American democratic experiment. Warren frames this literary critique as a diagnosis that sees the source of our national malaise in the stunting of individual development by our society. No one familiar with Warren’s fiction, poetry, or criticism would be surprised by this diagnosis; the body politic is corrupt in his novels, while in his poetry, the individual is restricted by social structures. In his literary and cultural criticism, Warren is drawn to earlier American writers and thinkers like himself.

Warren’s second essay, “Poetry and Selfhood,” is intended as therapeutic, and as autobiographical. He insists at the outset that “each of us must live his own life,” and as he extrapolates from his own knowledge, “perhaps I can find some echo in your experience.” For Warren, poetry—that is all serious literature generally—proves naturally democratic as diagnosis and therapy in regard to both the individual self and the social group. On the personal level, a work of the literary imagination may provide an image and an affirmation of selfhood for writer and for reader. These imaginative literary texts also organize and express the tensions between self and society, becoming a image, or “a dialectic of the social process” that may even affect social change, as with the literature of abolition in the nineteenth century or that of civil rights in the twentieth century.

At his conclusion, Warren reiterates, correctly I believe, that “the basis of our democracy is the conviction of the worth of the individual.” Certainly, he led his own life as a model and an assertion of his beliefs. Warren viewed the individuals he created from within and without, as separate selves struggling to define themselves against community and culture. In a way, Warren was his own best creation, projecting himself into the characters of his narratives and defining himself in the personae of his lyrics. As his literary canon developed over a long and distinguished career, Warren lived into what he called “the shadowy autobiography” found in his poetry and prose. Robert Penn Warren’s life and work, including Democracy and Poetry, thus provides a model of the sort of achieved selfhood and individuality that will be required of all to make democracy live through the troubling evolution of American politics in 2016 and beyond.

Featured image credit: “Robert Penn Warren birthplace museum historic marker” by Randy Pritchett. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Robert Penn Warren, Democracy and Poetry, and America after 2016 appeared first on OUPblog.

Resisting change: understanding obstacles to social progress

The People’s Climate Movement, made up of dozens of organizations working to fight the climate crisis, held their first march in September 2014. On Saturday, 29 April, activists will once again march to demand climate action. As they protest the Trump administration’s drastic approach to climate change, the People’s Climate Movement will aim to “show the world and our leaders that we will resist attacks on our people, our communities and our planet.”

In this shortened excerpt from How Change Happens, Duncan Green, Oxfam Great Britain’s Senior Strategic Adviser, discusses the complexities behind social activism, and breaks down the underlying factors that fuel the resistance to change.

Systems, whether in thought, politics, or the economy, can be remarkably resistant to change. I like to get at the root of the “i-word” (inertia) through three other “i-words”: institutions, ideas, and interests. A combination of these often underlies the resistance to change, even when evidence makes a compelling case.

Institutions: Sometimes the obstacle to change lies in the institutions through which decisions are made or implemented. Even when no one in particular benefits materially from defending the status quo, management systems and corporate culture can be powerful obstacles to change. Although I love Oxfam dearly, I also wrestle with its institutional blockages, including multi-layered processes of sign-off and a tendency to make decisions in ever-expanding loops of emails where it is never clear who has the final say. I guess I need to work on my internal power analysis.

Ideas: Often inertia is rooted in the conceptions and prejudices held by decision makers, even when their own material interest is not at risk. In Malawi, researchers found that ideas about ‘the poor’—the ‘deserving’ vs. the ‘undeserving’ poor—had a significant impact on individuals’ readiness to support cash transfers to people living in poverty. The elites interviewed—which included civil society, religious leaders, and academics as well as politicians, bureaucrats, and private sector leaders—all believed that redistributive policies make the poor lazy (or lazier). The overwhelming evidence for the effectiveness of cash transfers made no difference; neither did the fact that the elites stand to lose little from such reforms (and could even gain electorally, in the case of politicians).

People’s Climate March in Melbourne. View down Bourke St from the top of Parliament House steps as the march turns into Spring St. Photo by Takver from Australia. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

People’s Climate March in Melbourne. View down Bourke St from the top of Parliament House steps as the march turns into Spring St. Photo by Takver from Australia. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.I witnessed the obstructive power of ideas during my brief spell working in DFID’s International Trade Department. We received a visit from a senior official at the Treasury, worried that we were going off message. Radiating the suave self-assurance of a Whitehall mandarin, he informed us that, while he was happy to discuss UK trade policy, we should first agree that there were certain ‘universal truths’, namely that trade liberalization leads to more trade; more trade leads to less poverty. Both claims were highly debatable, but no-one was going to change the mandarin’s habit of regurgitating what he had learned at university some decades back. I recalled Keynes’ wonderful line: “Practical men who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.” Not much room for evidence-based policy making there. It is always possible, of course, that madmen in authority can be persuaded to change their minds, but it is uphill work: a steady drip-drip of contrary evidence, public criticism, pressure from their peers, and exposure to failures and crises all help. In the end, I fear that really deep-rooted ideas only change with generational turnover.

Interests: The writer Upton Sinclair once remarked “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.” Powerful players who stand to lose money or status from reform can be very adept at blocking it. Especially when a small number of players stand to lose a lot, whereas a large number of players stand to gain a little, the blockers are likely to be much better organized than the proponents. Billions of people could benefit from a reduction in carbon emissions that reduces the threat of climate change, but they will have to overcome opposition from a handful of fossil fuel companies first.

Interests are not always malign—after all, a great deal of progressive social change comes from poor people fighting for their own interests. Nor are interests always material. Masood Mulk, who runs the Sarhad Rural Support Programme in Pakistan, told me a wonderful story that harks back to the importance of psychology and personal relations:

I remember a valley where all the poor united to build the road, which they believed would change their lives totally. Unfortunately the road had to pass through the land of a person who had once been powerful in the valley, and he was totally unwilling to allow it. Frustrated, the villagers asked me to come to the valley and go to his house to resolve the problem. It was a remote place so we flew in a helicopter. For hours I tried to persuade him to be generous and give his permission but he would not budge. He did not like the way the communities behaved now that they were powerful. In the end he said he would relent, but only if we would fly around his house three times in the helicopter. I realized that it was all about egos. The villagers were unwilling to go to him because their pride did not allow it, and he was not willing to concede to them unless he could reemphasize his importance

In recent years, the glacial pace of progress on climate change illustrates all three i’s to a depressing extent: vested interests lobby to frustrate attempts to reduce carbon emissions and support spurious “science” to throw mud at the evidence that underpins the call for action; an unshakable belief in the value of economic growth limits any attempts to imagine a “beyond-growth” approach to the economy; and global institutions governed by national politicians with short time horizons are poorly suited to solving the greatest collective action problem in history.

Studying and understanding that force field is an essential part of trying to influence change. Though largely invisible to the newcomer, power sets parameters on how social and political relationships evolve. Who are likely allies or enemies of change? Who are the uppers and lowers in this relationship? Who listens or defers to whom? How have they treated each other in the past?

Starting with power should induce a welcome sense of optimism about the possibilities for change. Many of the great success stories in human progress—universal suffrage, access to knowledge, freedom from sickness, oppression and hunger, are at their root, a story of the progressive redistribution of power.

Featured image credit: “People’s Climate March” by Alejandro Alvarez. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Resisting change: understanding obstacles to social progress appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers