Oxford University Press's Blog, page 372

May 1, 2017

Sean Spicer’s Hitler comments: a warning from the history of speech and atrocity

Earlier this month, during a media briefing, Donald Trump’s Press Secretary, Sean Spicer, engaged in what some have referred to as a form of Holocaust denial. In referencing Bashar al-Assad’s most recent alleged use of chemical weapons on his own citizens, Spicer made an unprompted reference to Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler: “We didn’t use chemical weapons in World War II. You know, you had a, you know, someone as despicable as Hitler who didn’t even sink to using chemical weapons.” Given that Hitler notoriously used chemicals as part of gas chamber mass murder operations against Jews, many in the room seemed aghast. When later asked to clarify this comment, Spicer only added to the sense of disbelief, noting that Hitler “was not using the gas on his own people the same way Assad is doing…” Hitler, he stated, “brought [the chemicals] into the Holocaust center” while Assad “dropped them down to innocent, in the middle of towns…”

Ghetto of World War II by WikiImages. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Ghetto of World War II by WikiImages. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.The implications of Spicer’s words are chilling. He began by suggesting Hitler did not use Zyklon B against the Jews. When confronted with this apparent whitewash of history, he tried to distinguish Hitler from Assad by emphasizing that the former did not use chemicals against “his own people,” despite the fact that over one hundred thousand murdered German Jews were among Hitler’s victims. His characterization of grisly extermination camps, such as Auschwitz, as “Holocaust centers” could give one the impression that they were innocuous administrative units. In describing Assad’s victims as “innocent” when contrasting them with Jewish victims, one could infer that the latter were perhaps being perceived as “not innocent.”

Steven Goldstein, executive director of the Anne Frank Center for Mutual Respect, accused Spicer of having “engaged in Holocaust denial, the most offensive form of fake news imaginable, by denying Hitler gassed millions of Jews to death.” Apart from the anti-Semitic implications of Spicer’s statements, some have noted their value as a diversion in reference to Trump’s many failings as president. Francine Prose points out that this latest controversy allows us “to stop thinking about the damage being done to our environment and our schools, about the mass deportations of hard-working immigrants … about the ways in which our democracy is being undermined, every minute, every hour.”

But it would be a mistake to focus on these short-term implications of Spicer’s statements without understanding the broader harms they could engender. The history of speech and atrocity reveals that the most effective persecution campaigns can begin with relatively ordinary words with more subtle negative connotations. On their own, and in the abstract, they seem innocent enough. But in the larger context, they anesthetize the majority individual to the idea that the minority is an alien “other,” as opposed to a fellow citizen. And combined with other words and actions, they can eventually lead to tragic ends. For example, before ultimately falling victim to genocidal violence in Rwanda, Tutsis were at first chided by extremist Hutus for their alleged Ethiopian origins or their supposed accumulation of great wealth. But as Rwanda inexorably ramped up for genocide, such rhetoric intensified, with Tutsis eventually reduced to the vile caricature of “cockroaches” bent on liquidating the Hutus.

This is not to say that Spicer’s comments augur violence of such a scale. But it is important to remember that they are part of a larger, disturbing trend. One of Trump’s key advisers is Steve Bannon, “whose Breitbart news is a wellspring of bigotry and propaganda.” During his campaign, in bashing Hillary Clinton, Trump tweeted the image of a Star of David over a pile of money, which allegedly emerged from a neo-Nazi message board. In January, the White House omitted reference to the Jewish victims of the Holocaust in a statement to commemorate International Holocaust Remembrance Day. And this is all in the context of a rising tide of anti-Semitism and hate crimes against Jews in the U.S. and around the world. In this sense, Spicer’s oafish Holocaust denial could be part of a larger, emerging mosaic of anti-Semitism.

Steve Bannon by Gage Skidmore. CCO Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Steve Bannon by Gage Skidmore. CCO Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.As conditions deteriorate, when anchored to more direct calls for violence, Holocaust denial can morph into a technique for incitement to genocide. And in the context of a widespread or systematic attack against a civilian population, it can be part of the conduct element of persecution as a crime against humanity. Genocide denial is not merely an ugly reminder of a bloody past but should also be treated as a potential harbinger of a violent future. We are not anywhere close to that stage now, but we have been given notice and we ignore the larger context at our own peril.

Featured image credit: Sean Spicer, by Gage Skidmore. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Sean Spicer’s Hitler comments: a warning from the history of speech and atrocity appeared first on OUPblog.

April 30, 2017

Revisiting Douglas Sirk’s A Time to Love and a Time to Die

The Russian Front, 1944. A group of German soldiers happen upon a corpse encased in snow, apparent only by a frostbitten hand reaching towards them from the ground. “Looks like spring is coming,” one of the soldiers remarks. “That’s the one sure way to tell. The sun digs them up.” When the soldiers brush away the snow to find a man wearing a German uniform, they uncover the body and realize he is an officer from their regiment. “He looks like he’s crying,” one of the soldiers observes. Another replies with the blunt corrective, “His eyeballs are frozen and they’re thawing now.” So begins Universal International’s melodrama of love among the ruins, A Time to Love and a Time to Die (1958), an adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque’s novel published in 1954.

To commemorate the birthday of German-born director Detlef Sierck (1897-1987), better known to U.S. audiences by his professional name in Hollywood, Douglas Sirk, I want to revisit his penultimate film—also, I would argue, his greatest. Along with the making of The Tarnished Angels, another late career masterpiece released the previous year, Sirk was never allowed as much creative freedom on a production. A Time to Love and a Time to Die concerns a young, disillusioned German soldier, who falls in love with a woman in his family’s bombed-out village while searching for his parents during a three week furlough before returning to the Russian Front.

On location in Germany, the spectacular Eastmancolor and CinemaScope shooting gives the film the visual weight of an epic, but its focus is more intimate and, in fact, quite personal for the director. Sirk was a leftist intellectual living in Germany during Hitler’s rise to power. His ex-wife joined the Nazi party and legally forbade him from seeing their son, Klaus Detlef Sierck, as he had remarried a Jewish woman. Over the years, his son attained stardom as the leading child actor of Nazi Germany, and the only way for Sirk to see him was to go to the movies. In the spring of 1944, Klaus was killed on the Russian Front, and Sirk viewed A Time to Love and a Time to Die as an opportunity to imagine his son’s last weeks onscreen: a story Sirk would never know and a film that the Nazis would have most certainly prohibited.

The film has generated enough support to ensure a reputation among cinephiles, including important publications by Jean-Loup Bourget, Fred Camper, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, and, most prominently, Jean-Luc Godard. At the time of their original release, Sirk’s Hollywood films were dismissed by reviewers in the U.S. who equated their melodramatic style with bad taste, but Godard’s review in a 1959 issue of the French film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma represented one of the first critical attempts to take Sirk seriously as a film artist (an “auteur”).

However, following Jon Halliday’s book-length interview Sirk on Sirk (1972) and Sirk’s subsequent take-up in English-language film scholarship of the 1970s, films such as All That Heaven Allows (1955), Written on the Wind (1956), and Imitation of Life (1959) were reclaimed as exemplary of the Brechtian approach that he brought to his Hollywood projects, imbuing studio-assigned material with irony and contradictions at the level of film form. The midcentury family melodrama is thought to be the primary locus for his signature style and personal vision, as well as a genre that could be manipulated for progressive or subversive critique of postwar America’s bourgeois ideology. Thus, Sirk became a favorite both for auteurist film criticism and for Marxist, feminist, and psychoanalytic film theory, although perhaps at the expense of a film such as A Time to Love and a Time to Die, which belongs to the tradition of the romantic rather than the domestic melodrama and now occupies a marginal place in the Sirk canon.

As the title promises, the film is about love as much as it is about death, and they are inextricably linked in the film’s exploration of what it means to live and accept personal responsibility under the persistent threat of annihilation. The visual motif of cherry blossoms introduced in the opening credits metaphorically compares lovers Ernst (John Gavin) and Elizabeth (Liselotte Pulver) to a tree forced to bloom from the heat of a bomb’s explosion. Yet, as their blossoming romance is both enabled and interrupted by the war around them, they are constantly uprooted in their pursuit of a sustainable environment to make a home, from a one-room apartment to the rubble of an art museum to the cottage of a benevolent stranger (even a gourmet restaurant provides a temporary refuge as bombs are about to drop). The florid beauty almost overwhelms the story, and that seems to be the point. Sirk insists that self-discovery and emotional fulfillment may be born in these hostile conditions, if only apprehended in fleeting moments, for we know that the inevitable full bloom of spring has a moribund irony in this film.

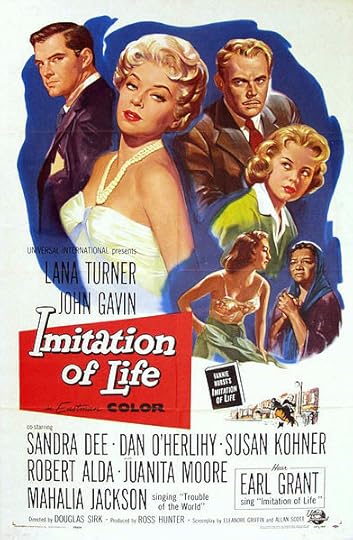

Poster for the film Imitation of Life (1959 film) Artwork by Reynold Brown, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Poster for the film Imitation of Life (1959 film) Artwork by Reynold Brown, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The United States, 2017. An executive order barred travelers from seven predominantly Muslim nations from entering the country. The federal budget plan proposed de-funding the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the National Endowmnet for the Humanities, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Academic integrity has been attacked by anti-tenure legislation and the appointment of an unqualified Secretary of Education who supports the privatization of public schools, to say nothing of the current administration’s claims of “alternative facts.” In these threatening political times, a case for revisiting a Classical Hollywood melodrama might be seen as a retreat from the present (at worst) or a quaint, even romantic appeal in the name of aesthetics (at best). But as historian Timothy Snyder warns us, “Post-factuality is pre-facism.” A Time to Love and a Time to Die is not only an anti-Nazi period piece and an underrated work of a canonical director, but a reminder of immigrant contributions to U.S. culture, the urgency for art and critical thinking to understand the world we live in, and the ongoing potential for cinema as a response to institutionalized oppression. Sirk may be relevant for us now more than ever before.

Featured Image credit: Soviet soldiers in Jelgava, August 1944. Доренский Л, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Revisiting Douglas Sirk’s A Time to Love and a Time to Die appeared first on OUPblog.

Witches and Walpurgis Night

In modern British and American popular culture, Halloween is the night most associated with the nocturnal activities of witches and the souls of the dead. But in much of Europe the 30 April or May Eve, otherwise known as Walpurgis Night, was another moment when spirits and witches were thought to roam abroad. The life and death of Saint Walpurga, who was born in Dorset, England, in the eight century, has nothing to do with witchcraft or magic, though. She travelled to Germany on missionary work, and became abbess of a nunnery at Heidenheim, dying there in the late 770s. The 1 May became her feast day because it was when her relics were transferred to Eichstätt in the 870s. The association of witchcraft with May Eve is actually to do with venerable rituals for protecting livestock at a time in the agricultural calendar when animals were traditionally moved to summer pastures. Bonfires were lit by communities across Europe to scare aware predators. In sixteenth-century Ireland, hares were killed on May Day, in the belief that they were shape-shifting witches bent on sucking cows dry and stealing butter. In Scotland, pieces of Rowan tree were placed above the doors of cow byres to keep witches away.

In the era of the witch trials, the Danish Law Code of 1521 observed that witches were active at holy times such as ‘Maundy Thursday and Walpurgis Night, and that they are said to spend more time on these than on other (festive) times during the year.’ In 1579, the town council of Mitterteich, Bavaria, ordered a patrol on Walpurgis Night ‘in expectation of such people, but nothing happened.’ In one Swedish village, in 1727, youths gathered under the window of a suspected witch on Walpurgis Night to chant ‘Our Lord free us from this evil troll.’

In German folklore, though, Walpurgis Night is particularly associated with the tradition that witches gathered from across the land for a great sabbat on the top of the Blocksberg (now Brocken), a summit in the Harz Mountains of central Germany. This great witches’ meeting may have been much depicted in nineteenth- and twentieth-century art and literature, but look closely at the early-modern witch trial records, and one finds little evidence for it. From the hundreds of confessions, most produced under torture, it is clear that sabbats were thought to take place at any time of the year and not Walpurgis Night in particular. From the records we also find that nocturnal sabbats were believed as likely to take place in clearings and meadows as on mountain tops.

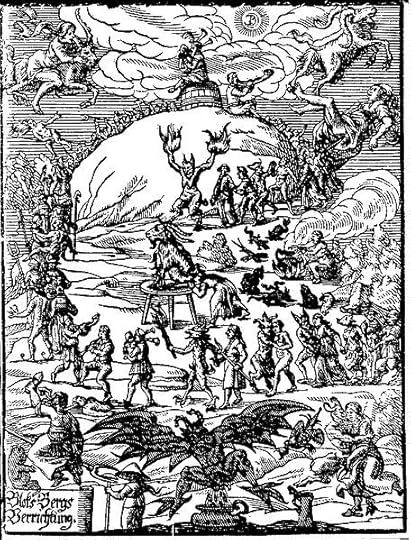

Praetorius Blocksberg Verrichtung. Witches’ Sabbath by Johannes Praetorius. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Praetorius Blocksberg Verrichtung. Witches’ Sabbath by Johannes Praetorius. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.It was in 1668 that the Walpurgis Sabbath was first firmly located at the Brocken in a weighty tome about the history and geography of the mountain and the region, called The Blocksberg Performance by Johannes Präetorius. It included an illustration of orgiastic celebrations taking place around the mountain top. But the spread of the archetypal Walpurgis Night sabbat on the Brocken owes much to the creative mind of the German philosopher and poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832). He drew upon Präetorius’s book for his famous play Faust (1808), in which he depicts the legendary sixteenth-century magician and Mephistopheles travelling to the summit of the Brocken, accompanied by witches and demons. The witches strike up a chorus:

“Witches bound for the Brocken are we,

The stubble is yellow, the new grain is green.

All our number will gather there,

And You-Know-Who will take the chair.

So we race on over hedges and ditches,

The he-goats stink and so do the witches.”

Faust later reflects:

“It seems, forsooth, a little strange,

When we the Brocken came to range,

And this Walpurgis night to see,

That we should quit this company.”

Widely lauded and translated, Goethe’s Faust, provided inspiration for subsequent artists, including the likes of the writers Bram Stoker and Thomas Mann, and composers such as Brahms and Mendelssohn. The Walpurgis Night sabbat on the Brocken continues to be referenced in popular culture today by the likes of heavy metal bands and in horror films, while the tradition has also been adopted into the Neo-pagan calendar as an analogue of the supposed Celtic festival of Beltane.

So watch out this Bank Holiday weekend, for there might be witches abroad.

Featured image credit: Lewis Morrison as “Mephistopheles” in Faust! – “The Brocken”. Theatrical performance poster for Faust, 1887. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Witches and Walpurgis Night appeared first on OUPblog.

Fielding and fake news

Fake news is not only a phenomenon of post-truth politics in the Trump era. It’s as old as newspapers themselves—or as old, Robert Darnton suggests, as the scurrilous Anecdota of Procopius in sixth-century Byzantium. In England, the first great age of alternative facts was the later seventeenth century, when they clustered especially around crises of dynastic succession. The biggest political lie was the widely believed Popish Plot of 1678, a fictitious Jesuit conspiracy to assassinate King Charles II that played into the Whig campaign to exclude Charles’s Catholic brother from succession to the throne. Conspiracy theorists of all political stripes got in on the act. At one point in his history of the period, David Hume writes wearily that “this was no less than the fifteenth false plot, or sham plot, as they were then called, with which the court, it was imagined, had endeavoured to load their adversaries.”

Daniel Defoe, before his career as a novelist began with Robinson Crusoe (1719), was among the journalists who fought fierce running battles in rival newspapers during the reign of Queen Anne. In 1703, he was convicted of seditious libel for fabricating an incendiary pamphlet in the voice of his Tory opponents, and a year later his political stablemate John Tutchin was arrested and tried as “a daily inventor and publisher of false novelties, and of horrible and false lies” in his journal the Observator. Tutchin got off on a technicality, but was later beaten up to order (evidence points to the Duke of Marlborough) and died of his injuries. Defoe continued to flourish with his journal the Review, berating rival journalists for their own fabrications. One target was George Ridpath’s rabble-rousing newspaper the Flying Post, which Defoe called simply the “Lying Post.”

Etching of Henry Fielding from 1920, originally based on drawing by William Hogarth, 1798. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Etching of Henry Fielding from 1920, originally based on drawing by William Hogarth, 1798. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.We think of Henry Fielding, in the next generation, as a novelist above all else. But before writing Joseph Andrews (1742) and his masterpiece Tom Jones (1749), he was London’s foremost comic playwright, and, in the Champion (1739–41) and later periodicals, the funniest satirical journalist of the day. It was a gift to Fielding’s career that it coincided with the heyday of Sir Robert Walpole, the powerful, charismatic “Great Man” and longest-serving Prime Minister in history—if “serving” is the right word for a politician so thoroughly committed, his enemies alleged, to corruption and self-enrichment.

Fielding’s relations with Walpole make up a complex story including periods in which he sought Walpole’s patronage and ending, very possibly, with his acceptance of a bribe to desist. As a well-placed insider reported shortly before Walpole fell from power in 1742, Fielding “is actually reconciled to the great Man, and as he says upon very advantageous Terms.” Satirical hostility, however, is central to the story. At the height of his celebrity as a playwright, Fielding targeted Walpole’s ministry with innovative, incendiary dramas including Pasquin (1736) and The Historical Register for the Year 1736 (1737), a farce teasingly named after one of the period’s few objective news sources. These plays were not the sole cause of Walpole’s Stage Licensing Act of 1737, which required pre-performance approval of playtexts and prohibited improvisation, but they were a major catalyst. When Fielding then turned to journalism, it was widely feared that print censorship would follow. In 1740, another insider reported impending legislation to control “the Licentiousness (as they call it) of the press. There is not one of the Courtiers but I hear talk of such a Bill. The champion’s way of writing, they say, makes it necessary.”

Among the Champion’s most damaging themes was its ridicule of Walpole’s propaganda machine. One barbed issue (29 January 1740) offers spoof instructions in the “Art of Lying,” a word which “as it regards our interest, however it came to be scandalous I will not determine, comprehends Flattery and Scandal, a false Defence of ourselves, and a false Accusation of other People.” Fielding then outlines a poetics of disinformation in all its varieties (“the Lie Scandalous,” “the Lie Panagyrical,” etc.), necessary to the exercise of which is a brazen fearlessness of being contradicted. Flexibility is crucial, and sometimes the accomplished political liar must even “quit his Occupation, and dabble in Truth.” Preparation is essential—no careless ad libs about alternative facts—and “in spreading false News, especially Defamation, Care should be taken in laying the Scene.” In a precept discarded today, Fielding warns his ambitious politician “never to publish any Lie in the Presence of one who knows the Falsehood of it.”

The attack also spilled over into Fielding’s fiction. Shamela (1741) is on the face of it a parody of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela (1740), subverting that novel’s premise by turning Richardson’s virtuous heroine (a servant rewarded by marriage to her master) into a cynical gold-digger. But Fielding also likens his falsifying anti-heroine, who has “endeavoured by perverting and misrepresenting Facts to be thought to deserve what she now enjoys,” to Walpole-era ministers whose “worldly Honours…are often the Purchase of Force and Fraud.” In Tom Jones, the mendacious villain Blifil (his name suggests both “lie” and “fib”) ends up as Member of Parliament for a rotten borough. Fielding’s most sustained political fiction, Jonathan Wild (1743), builds on a longstanding analogy in opposition journalism between Prime Minister Walpole and the historical Wild, an underworld kingpin. Politicians and thieves are engaged alike in “the great and glorious…Undertaking…of robbing the Publick.” Both succeed by clever ruses to distract the public’s attention, so that “while they are listening to your Jargon, you may with the greater Ease and Safety, pick their Pockets.”

Walpole was now out of office, but he remained a formidable operator. His last and most engaging imposture was to pretend that none of this had anything to do with him—or, if it did, that even a satirist as brilliant as Fielding couldn’t hurt him. Jonathan Wild was published in Fielding’s Miscellanies, preceded by a list of subscribers who could show special approval by buying expensive “royal paper” sets, sometimes in multiple copies. The most generous patron of all, subscribing for ten sets in royal paper, was Walpole himself.

Featured image credit: Anonymous Interior of a London Coffee House, 1668. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Fielding and fake news appeared first on OUPblog.

April 29, 2017

From the Bastille to Trump Tower?

Since his inauguration, President Donald J. Trump has courted controversy by issuing a series of tweets or executive orders. His endorsement of the efficacy of waterboarding, an illegal and degrading form of torture, or the decision to close the US frontiers to citizens of seven predominantly Muslim countries provoked outrage amongst his many opponents. When the courts overturned that order, the President’s condemnation of the judges who had countermanded his action led to further hand-wringing, even if it also provided a perfect illustration of the checks and balances in the American Constitution. President Trump’s attempts to shut the border and his faith in the efficacy of torture form part of what he, and many others, interpret as part of a necessary and on-going struggle against “Islamic Terrorism”.

His immediate predecessors were also responsible for extra-judicial methods, as the continued existence of Guantanamo Bay, which still holds prisoners detained without trial, demonstrates. Nevertheless, that the freely elected head of the world’s most powerful democracy should advocate the methods of the Inquisition is depressing, and it means that hopes of persuading authoritarian regimes in, for example, China, North Korea, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Syria or Turkey, to shy away from waterboarding or any of the other repulsive items in the despot’s repertoire are slim indeed. Of course, those who defend torture or detention without trial will cite the blood-curdling nihilism of ISIS, and claim that they are only targeting the “bad dudes” in order to protect the lives of their fellow citizens. Yet no matter how tempting those arguments might appear, we should not forget that all too often in the past one person’s “bad guy” has been someone else’s “freedom fighter”.

Photograph of Donald Trump. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Photograph of Donald Trump. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Ultimately President Trump is merely the latest in a long line of rulers to look to the doctrine of raison d’état to justify his stance, and in doing so he unconsciously echoes debates that had a profound influence on the development of the American Constitution and our broader understanding of individual rights. In 1648, after nearly a century of intermittent civil war and sectarian strife, the ministers of the young Louis XIV found themselves once more staring into the abyss. Desperate to uphold the crumbling royal authority, Chancellor Pierre Séguier had sought to persuade an assembly of mutinous judges that if the crown was denied the right to imprison without trial the very existence of the state would be in peril. Better, he argued, “that a hundred innocents suffer than that the state should perish from the impunity of an individual,” a stance that has been echoed globally in the detention of millions on the grounds of suspicion ever since. Séguier’s opponents challenged his claims in the name of public safety, arguing that no one should be subject to punishment without trial, calling instead for a law of habeas corpus. It was only fleetingly established, and Louis XIV would soon lay the foundations of a strong monarchical authority that would endure until the eve of the French Revolution.

Neither Louis XIV, nor his successors, could be described as tyrannical, or even particularly authoritarian, especially when compared to the horrors of the last 100 years, but the Bourbon monarchs did put Séguier’s words into practice and the Bastille became a symbol for the punishment of those who had displeased them. By issuing lettres de cachet, simple written orders signed by the king, individuals could be detained or banished for an indeterminate period, without charge, trial, or hope of legal redress. While generally accepted as a legitimate royal prerogative, perceived abuse of the system in the course of the eighteenth century led to fierce criticism of what, for many, was the arbitrary and despotic treatment of the citizen. Drawing upon the legacy of Séguier’s critics, Montesquieu argued persuasively for the separation of powers, and for an independent judiciary to prevent monarchical power from becoming fickle or capricious. Others inspired by his writings, including the Enlightened jurist and minister, Lamoignon de Malesherbes, or future revolutionaries such as Mirabeau or Billaud-Varenne, denounced lettres de cachet which had become a tool in the hands of ministers, administrators, tax officials and even clerks to imprison those who displeased them in the name of the king.

It was against this background that Voltaire set spines tingling with his tale of the Man in the Iron Mask, the seemingly tragic history of a prince, Louis XIV’s twin or older brother, who had been locked away in diabolical fashion by Mazarin and Anne of Austria. Quite remarkably, there really was a Man in the Iron Mask, or to be more accurate a velvet one, who was imprisoned for decades on the orders of Louis XIV. Although we are sure the victim was not a sibling of the king, historians are still divided about his precise identity and it was that very uncertainty that added to contemporary unease. Fear that an anonymous denunciation might lead to an innocent man or woman suffering the awful fate of the masked prisoner was widespread, and victims, real or imagined, of lettres de cachet helped to reinforce a campaign for their abolition. Central to that struggle was a belief in the separation of powers.

The executive, whether the king, or more commonly those acting in his name, should not act as both judge and jury, and to imprison or banish individuals without trial was an offence to natural rights and the principles of justice and liberty. Thanks to a constitution written against the intellectual background of these debates, the American judiciary will preserve its independence in the new era of the “executive tweet.” Yet Trump’s unorthodox introduction to high office is a reminder that in all too many other societies imprisoning, torturing, or simply refusing freedom of movement is not a clumsy threat, but a daily reality, and, that today, as in the eighteenth century, without the rule of law there is neither justice nor liberty.

Featured image credit: The Bastille in the first days of its demolition. Painting by Hubert Robert, 1789. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post From the Bastille to Trump Tower? appeared first on OUPblog.

Slipping expectations for child outcomes

The movie Moonlight, best-picture Academy Award winner in 2017, was described as epitomizing resilience, a common focus in psychological circles. After experiencing bullying from peers for years and a neglectful and emotionally abusive home life throughout childhood, the main character, Chiron, as an adult forgives his drug-addicted mother when she apologizes to him and he reconnects with his only childhood friend. He was no longer in prison but is a “business man,” a drug dealer. Many would call this resilience. Resiliency is the ability to ‘bounce back’ from significant stresses such as poverty, divorce, and abuse. But we should ask: bounce back to what?

Certainly we should be happy that kids from “at risk” environments graduate from high school and do not end up in prison for life. But is this enough to aim for? We may not score their life outcome as minus 5 (on a -10 to +10 scale), but Chiron’s life outcome does not warrant much more than a zero. Why? Because his intelligence, unique gifts, and potential were not fostered (which would go on the plus side of zero). Worse, he is hardly prepared to be a citizen who can tackle the many crises facing humanity and the planet.

Both psychologists and the general public have lowered their standards for what counts as a good outcome for children.

The slippage in expectations for child outcomes in “at risk” environments (and even in non-risky environments!) represents one of several interrelated shifting baselines regarding wellbeing and a good life.

The first shifted baseline is lowered expectations for raising children generally. Though every animal—including humans—has a nest for its young, this is largely forgotten in nations like the United States. The evolved nest for young children minimally includes soothing perinatal experiences (no separation of baby from mother, no painful procedures); responsiveness to infant needs to prevent distress; extensive on-request breastfeeding; extensive positive (no negative) touch and holding; positive climate and social support for the mother, the child, and the dyad, including multiple responsive familiar caregivers; and self-directed social play. Each of these characteristics has known neurobiological effects on the child.

“Both psychologists and the general public have lowered their standards for what counts as a good outcome for children.”

And they influence children’s thriving and sociomoral development.

As you may have noticed, these things are rarely provided to children in the United States. In fact, instead of providing the nest of care that humans evolved to need, the culture’s focus is on minimal provision. Communities do not support families to provide much else. And cultural narratives justify this minimal care routinely (“don’t spoil the baby;” “teach the baby independence”). Instead of understanding that babies need intensive support, children often seem to be considered bags of genes in need of strong external controls to keep them from taking over a parent’s life. But the fact is that humans are largely shaped after birth, with greater epigenetic effects (genes “turned on” by experience) than for any other animal, with lifelong implications for health, sociality, and morality.

The second slippage is lowered expectations for children’s biopsychosocial wellbeing. Members of nations like the United States often expect children to be selfish and aggressive, needing coercion and control—the unsurprising results of a degraded early nest. Denying young children satisfaction of their needs through nest provision is a form of trauma—it makes for toxic stress when neurobiological systems are self-organizing around experience.

The third slippage is lowered expectations for adult biopsychosocial wellbeing and morality. Just as with “un-nested” children, we expect adults to be selfish and aggressive. Instead of demonstrating self-governing virtue, un-nested children and adults require external rules and sanctions to behave well. Again, because troublesome adults are expected, it is not a surprise when they lie, cheat, and grab resources for themselves.

The fourth slippage is lowered expectations for the culture. Un-nested adults create a society like the one they experienced, only worse. Poor parenting gets worse over generations and it may be that cultures do too, largely because of the missing foundations for flourishing that the evolved nest provides. The effects cascade and snowball over generations. The culture rationalizes the poor behavior as evolution’s fault (“selfish genes”) or flawed human nature (“original sin”), with the resulting belief that “there is nothing we can do.”

However, there is something to be done. Humanity has a long history of providing the evolved nest to their young with resulting flourishing outcomes. Nomadic foragers represent 99% of human genus existence and their recurring patterns of behavior have been studied by anthropologists. They provide a better baseline for understanding what is normal for a human being and how providing the nest influences personality and human nature. These societies are still found all over the world and have been well described by anthropologists and others as largely peaceful, content, and at ease with living sustainably on the earth. They show what happens when communities provide the evolved nest: children and adults with high sociality, wellbeing, cooperative and communal capacities, accompanied by a culture that provides for basic needs. Charles Darwin noted that such societies demonstrated the evolved “moral sense,” whereas his male British compatriots not so much. The type of moral self one develops may depend on the evolved nest.

Instead of only focusing on survival within high-risk environments, a crisis mentality, what our culture needs now are visions of optimal flourishing. We need films that depict species-typical flourishing—i.e., what children, adults, and cultures are like when communities provide children with the evolved nest. If such children are impossible to find, then it is a signal that psychologists, parents, and communities have work to do—in changing their ideas of what to aim for and in helping communities provide the evolved nest. We can move past maintaining low expectations and aim for optimizing every child’s unique gifts.

Featured image credit: Orphan by WenPhotos. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Slipping expectations for child outcomes appeared first on OUPblog.

Celebrating 100 years of Urie Brofenbrenner

In the United States, currently, about 15 million children (almost a quarter of the global child population) live in families whose income falls below the federally established poverty level. The damaging effects on children’s and families’ development were something that was a life-long concern of Urie Bronfenbrenner, the Jacob Gould Schurman Professor of Human Development at Cornell University, until his death in 2005. Had he lived, he’d be turning 100 on 29 April 2017.

Among his significant accomplishments, he was one of the founders of the Head Start movement (a federal US program designed to provide quality child-care experiences to children of poor families) in the 1960s and developed what came to be known as the bioecological theory of human development. When I arrived as a doctoral student at Cornell in 1981, to study under Bronfenbrenner, his widely cited book The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design (1979) had only recently been published, but I knew nothing about it. I’d been attracted to work with him because of his writing on Soviet child-rearing practices. He’d been born in Moscow, and though he left with his family for the United States, aged six, as an adult he travelled frequently to the Soviet Union to meet with child psychologists. He was convinced that some contemporary Soviet practices, if incorporated into the American way of life, would help in the process of “making human beings human.” He was unhappy with the negative perception that Americans and Russians had of the “other side” and felt that approaches such as group – rather than individual – competition and greater integration of children into the broader community would benefit American youth.

Much of his writing about children and families involved the same theme; he felt that American children and adolescents spent too much time either in front of the television or with same-age peers. This approach, he felt, would lead to increasing alienation. Instead, he drew from European ideas about child rearing, ideas that involved community and governmental support for parents, particularly single mothers and parents living in poverty. Quality child care, he believed, needed a broad supportive framework, one in which children and parents were integrated into the wider community. He therefore called for longer maternal and paternal leave policies, child-care centers to be established in workplaces, and for flexible work time for parents. His overall concern, reflected in the title of one of his articles, was that “Our system for making human beings human is breaking down.” He didn’t blame families for these problems: “Most families are doing the best they can under the circumstances; we need to try to change the circumstances and not the families.”

Brofenbrenner’s ecological Model of development by Alyla.k. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Brofenbrenner’s ecological Model of development by Alyla.k. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.He was invited to testify before Congress in 1964 about the effects of poverty on children’s development, and that led to a meeting at the White House with the then President’s wife, “Lady Bird” Johnson. He was subsequently asked to discuss his ideas with a federal panel whose aim was to find a way to counteract the negative impact of poverty and put children of poor families on a more equal footing with those being raised in wealthier families. Giving poor children a “head start” was intended to give them a chance to compete more equally. Although others were involved in planning the educational and nutritional aspects of the Head Start program, it was Bronfenbrenner who encouraged the idea that this program would greatly benefit not only from government support, but from the active and engaged participation of the parents themselves, and the involvement of the entire community.

This integration of the individual and the broader context is of course one of the hallmarks of his theoretical work. For Bronfenbrenner, the practical and the theoretical were always linked. He was fond of quoting one of his intellectual forebears, Kurt Lewin, to the effect that “there is nothing so practical as a good theory”). He initially termed his theory an “ecological” theory of human development to stress the dialectical nature of person–context relations. Given contemporary notions in American psychology that strongly emphasized the role in development of individual characteristics, Bronfenbrenner’s 1979 book paid more attention to the role of context, leading to the popularization of the famous four layers of context – microsystem, mesosytem, exosystem, and macrosystem.

The theory developed greatly over the next twenty years, however. Terming it a bioecological theory was far more than a mere change of names. Context was but one of four interconnecting concepts linked in the Process–Person–Context–Time model. Of these four, it is proximal processes – typically occurring activities and interactions that become more complex over time – that are key to the model. Proximal processes are simultaneously influenced both by characteristics of the person and the context, with the latter viewed as local (e.g., home, school, or workplace) and distal (e.g., class, ethnicity, or culture).

Unfortunately, too little attention has been paid to these changes. Almost any internet site that appears when typing “Bronfenbrenner’s theory” into the search engine will reveal images of concentric rings and information about context, as though context is all that’s important. Child development textbooks make the same mistake. Even scholars who state that they are using Bronfenbrenner’s theory in their research are likely to treat it as one that primarily focuses on context. Yes, context is important; Federal and State policies should be designed to help families and children move out of poverty. However, changing the overarching context is not sufficient.

As Bronfenbrenner loved to point out throughout his life, it is the active engagement of individuals (children, parents, teachers, community members) in the course of activities with others, over time, that makes human beings truly human.

Featured image credit: Cornell University from McGraw Tower by Maeshima hiroki. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Celebrating 100 years of Urie Brofenbrenner appeared first on OUPblog.

The origins of dance styles

There is an amazing variety of types, styles, and genres of dancing – from street to disco, to folk dancing and ballroom. Some are recent inventions, stemming from social and political changes, whilst others have origins as old as civilisation itself. Archaeological evidence for early dancing has been found in 9000 year old Indian cave paintings, as well as Egyptian tombs with dancing figures decorating the walls, dated to around 3300 BC. Society’s love of dance has never waned, and it is just as popular now as ever. With the rise of dancing television shows, official competitions, and public events around the world, we thought we’d take a look at some of the most widespread types of dance and how they started.

Do you know your Jive from your Jazz, your Salsa from your Samba? Read on to discover the surprisingly controversial origins of the Waltz, and the dark history of the American Tango.

The Charleston was especially popular in 1920s America, as a fast-paced and strongly syncopated dance (i.e. emphasizing unstressed musical beats with the steps and movements). Its name derived from Charleston in South Carolina, and although it is usually danced by two or more people, was originally a solo dance performed by African-Americans. The Charleston was accepted as a ballroom dance in 1926, with Josephine Baker being one of its most celebrated performers.

Like the Charleston, the Foxtrot is another popular ballroom dance of American origin. It is danced to a march-like ragtime (which can be either slow or fast, with alternating slow and quick steps). This is a type of music usually played on the piano, evolved by African-American musicians in the 1890s. Similarly to the Charleston, this music also features syncopated melodies, with accented accompaniments. From around 1913 onwards, the Foxtrot was widely danced around the world.

The Lindyhop is another dance of American origin, performed by couples to Swing music. It first appeared at Harlem’s Savoy Ballroom in the 1920s, where black dancers embellished the choppy steps of the Charleston with increasingly flamboyant improvised moves. These include fast spins, cartwheels, throws, and jumps, where the woman leaps with her legs straddling her partner’s waist or shoulders. After the Lindyhop became popular with white dancers, it became known as the Jitterbug, and enjoyed a revival in Britain and the United States during the 1980s and 1990s.

Josephine Baker dancing the Charleston at the Folies-Bergère, Paris’ by Walery French, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Josephine Baker dancing the Charleston at the Folies-Bergère, Paris’ by Walery French, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The Rumba is an incredibly distinctive Latin American dance, in 4/4 time (the most common musical form). It originally evolved as a courtship dance popular in Cuba, and was introduced to the United States in the 1930s. It is danced by a lone couple, and is characterized by a swaying motion of the hips.

Akin to the Rumba, the Salsa is also a Latin American dance performed in 4/4 time. Quite literally meaning sauce (with spicy connotations), Salsa combines both Caribbean and European elements. Although the name itself is quite a recent invention (coined in the 1960s), the origins of the dance go back to older dances, most notably Son, from Cuba. It is usually danced by couples and is characterized by rhythmic footwork, fluid turns, and quick changes of balance. Salsa achieved international popularity in the 1980s, and has continued to evolve ever since.

Samba is a generic form of Brazilian music and dance, which can include many varied forms and styles. Unlike the Salsa which usually involves dancing with a partner, a Samba is often danced solo or in a group, as well as with a partner. It is usually in a steady 2/4 time rhythm, featuring a syncopated accompaniment.

The Tango is a South American dance performed to a slow 2/4 time. It is characterized by sensual partnering and fast interlocking footwork, based on dances brought to Argentina by African slaves. It was originally performed in the slums of Buenos Aires in the 1860s, closely linked to Tango music and song. In the 1920s however, the Tango became popular worldwide as a form of ballroom dancing, later popularised in stage-shows and Hollywood films, as well as musicals and ballets.

The origins of the Waltz are unclear, but it is a German-Austrian turning dance (with many similar precedents), performed in 3/4 or 3/8 time. The name Waltz appeared in the late 18th century, and it quickly gained in popularity through the music of Lanner and the Strausses. Some European authorities tried to ban it however, in the beginning, on account of the daringly close embrace required between the male and female dancers. It features prominently in many ballets, including Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty, and The Nutcracker.

Featured image credit: ‘Tango Street Art, Buenos Aires’ by Rod Waddington. CC-BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons .

The post The origins of dance styles appeared first on OUPblog.

Let’s end the first hundred days

The 30 April marks the one hundredth day of the Trump presidency. The media will be deluged with assessments about what Donald Trump accomplished — or didn’t — during his first one hundred days. But this an arbitrary, and even damaging, way to think about presidential performance.

“The first hundred days” is embedded in American political culture. During the presidential race, Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton made big promises about what they would accomplish in their first hundred days in office. As president, Trump has kept score of his accomplishments in that period. The media has kept a steady watch on his triumphs and setbacks as well. MSNBC has used a “first 100 days” chyron on its broadcasts for the last several weeks.

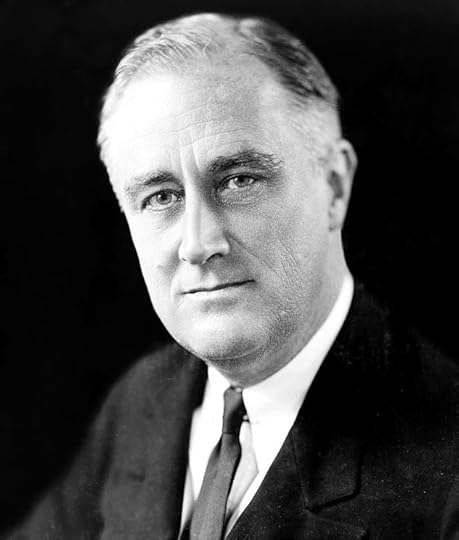

Two people are to blame for this marker. The first is Franklin Delano Roosevelt. At his inauguration in March 1933, FDR promised bold action to address the “national emergency” of the Great Depression. FDR didn’t say anything about 100 days. By the end of June, however, his allies were boasting about the administration’s accomplishments. Senator Clarence Dill bragged that “these first 100 days of Roosevelt will be known in history as the greatest peaceful revolution in the annals of organized government.”

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Fair Use via the US Library of Congress.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Fair Use via the US Library of Congress.Still, that wasn’t enough to fix “100 days” in America’s political consciousness. For the next quarter century, it didn’t matter much at all. The Truman administration tried to recreate the magic of 1933 without success. Most people recognized that FDR had been given unusual leeway because he faced an extraordinary crisis. Dwight Eisenhower also faced a few “100 days” appraisals in 1953. But pundits refused to get on the bandwagon. “It’s just a relic of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration,” one wrote. “Actually 100 days is too little time in which to size up any administration.”

The 100-day benchmark really gained traction after 1959, when the Harvard historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. published the second volume of his history of the FDR years. The book converted the first months of FDR’s presidency into a myth. Schlesinger called that period “The Hundred Days” — a time of “intense drama and prodigious legislation.” Schlesinger was a key advisor to John F. Kennedy, whose campaign seized on the idea of recreating FDR’s glory. One veteran of the Kennedy administration recalled the prevailing mood after JFK’s election: “We’ve got to make the first hundred days impressive. We’ve got to do a lot of things fast and differently.”

The political scientist Richard Neustadt, who worked for Truman, tried to warn Kennedy against setting unreasonable expectations. But the effort was futile. The benchmark became fixed in everyday conversation about national politics. “The Hundred Days,” one columnist explained in 1961, “are any President’s grand opportunity to create the atmosphere for himself to establish leadership.” Over the next half-century, presidents wrestled with the 100-day standard. If they did not adopt it themselves, others imposed it on them.

But there are good reasons to be skeptical about the 100-day benchmark. FDR faced truly extraordinary conditions. He won the 1932 election in a landslide, while Democrats won solid majorities in both house of Congress. People were desperate for strong leadership. Some even played with the idea of dictatorship. Few disagreed when Roosevelt compared the economic emergency to a state of war. Under those circumstances, people weren’t fussy about whether the content of federal policies was exactly right. They were happy to see the government do anything. “The country demands bold experimentation,” Roosevelt said during the campaign. “Above all, try something.”

No president after FDR has faced similar conditions. As a matter of practical politics, no later president has enjoyed such an immense political mandate, or led a nation that was so hungry for strong leadership. And as a matter of policy, no later president has faced such a simple playing field. FDR wasn’t worried about overhauling established policies and bureaucracies. He had a blank slate, and anything he might do seemed better than doing nothing at all.

The world is different today. Both politics and policies are more complex. And yet we persist in revering the myth of The Hundred Days. This isn’t just unfortunate: it’s dangerous. It leads presidents and legislators into debacles like the attempts to repeal Obamacare. President Trump should have allowed more time for an overhaul of the complicated healthcare law. But Trump had already added this to his extensive list of 100-day promises. The rush — and eventual failure — has only aggravated the perception that Washington is dysfunctional.

In fact, we ought to be especially wary about the 100-day benchmark today. In an era of political polarization, rushing to action is a bad idea. Not only is it unlikely to be successful, it also stokes anxiety within the large bloc of voters who happen to be on the losing side of an election. It heightens fear that everything they care about is in immediate danger.

In 1787, the drafters of the Constitution debated how long the President’s term should be. They settled on four years for good reason. As Alexander Hamilton explained, presidents need time to make and execute well-crafted plans. The 100-day benchmark undermines that logic. Perhaps it made sense at one special moment in history, when rapid action was key to national recovery. Today, the 100-day marker doesn’t bring the country together. It drives the nation apart.

Featured image credit: 1933 Franklin D. Roosevelt’s First Inauguration by US Capitol. Fair use via US government works .

The post Let’s end the first hundred days appeared first on OUPblog.

Remembering Charlie Chaplin, citizen of the world

Early in the 1957 film A King in New York, the second-to-last feature that Charlie Chaplin would write and direct and the last in which he would star, an unusual debate erupts between the two principal characters, one an exiled monarch and the other a precocious schoolboy. The subject at hand is passports, of all things, and the exchange is ferocious. Governments, the boy declares, “have every man in a straightjacket and without a passport he can’t move a toe…. To leave a country is like breaking out of jail and to enter a country is like going through an eye of a needle.” “Of course you are free to travel,” replies the indignant king. “Only with a passport!” the boy retorts. “It’s incorrigible that in this atomic age of speed we are shut in and shut out by passport!”

Chaplin, then 68, plays the sputtering old monarch arguing for the current world order, but the aging star’s true sentiments were those of the radical youngster (played by his son, Michael Chaplin). If today this frenzy about passports seems all a bit mysterious, audiences at the time would have understood the reference immediately. Though he lived and worked for nearly forty years in the United States, the British-born Chaplin never applied for an American passport; A King in New York was released just five years after the star’s de facto exile from his adopted homeland when his re-entry permit to the country was denied for political reasons. (For audiences in the U.S., who didn’t see the film until 1973, the issue would have been equally in mind, with the film’s release coming just one year after Chaplin’s long-awaited return to the United States to accept an honorary Academy Award.) The question of passports and the issue of the free movement of individuals across international borders was one of the preeminent concerns of Chaplin’s later life.

This month marks the 128th anniversary of Chaplin’s birth in England and this year the 65th anniversary of his proscription from re-entering the United States; both anniversaries afford an opportunity to reflect on Chaplin’s passionate internationalism and its relevance to our world today. Chaplin was a victim of the red scare of the 1950s, to be sure; his unabashedly left-leaning political sympathies made him vulnerable to charges of communism and prompted both FBI and MI5 investigations into his background and allegiances. But political systems aside, he was also an outspoken advocate for a kind of radical internationalism that didn’t sit well with early Cold War sensitivities. “I consider myself a citizen of the world,” Chaplin declared to the American press in the late 1940s when questions about his refusal to apply for American citizenship began to circulate.

For Chaplin, claiming to be a “citizen of the world” was no mere rhetorical gambit: it was to some degree actually true, in the sense that Chaplin was known and beloved in countries around the world. Rising to stardom in the midst of film’s ascendency as an internationally popular medium of entertainment, Chaplin was one of the first global celebrities. By the height of his fame during the 1920s, there was not a habitable continent on the planet where people didn’t clamor to see his films. Movie palaces in the British colonial city of Accra (now the capital of Ghana) teemed with spectators watching unlicensed re-cuts of Chaplin’s films; his famous Tramp character spurred home-grown imitators in Japan. Chaplin himself estimated that seventy percent of his income derived from revenue generated outside of the United States. “My business is an international one,” he proudly declared in his autobiography.

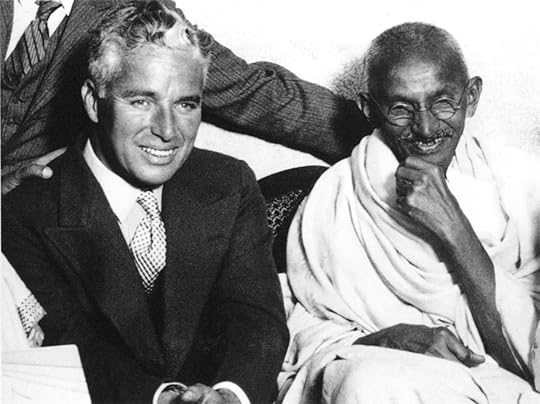

Gandhi meets with Charlie Chaplin at the home of Dr. Kaitial in Canning Town, London, September 22, 1931. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Gandhi meets with Charlie Chaplin at the home of Dr. Kaitial in Canning Town, London, September 22, 1931. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.More than just a monetary concern, that near-universal popular acclaim clearly spurred or reinforced in Chaplin a vision of a cooperative international community. The filmmaker’s very life and livelihood in fact depended on the free movement of individuals and the free exchange of goods. Born into extreme poverty in the south of London at the close of the Victorian age, he rose to fame across the Atlantic in the American film industry and grew his fortune distributing his films abroad as co-founder and part-owner of United Artists. Yet Chaplin, who made his living telling stories drawn in large part from his own impoverished background, was always an uneasy capitalist. His enthusiasm for the free flow of people and goods across borders had less to do with enriching the few and more to do with empowering the many. In an unpublished essay called “The Road to Peace” that he wrote around 1960, Chaplin asks whether, in an age of international media and film distribution when images and stories are shared around the world, it is “any wonder … that vast masses of people are desiring a better way of life?” For Chaplin, internationalism in its truest sense meant the pursuit of international equity. “World peace will never be secure unless all nations have a fair share of the raw materials vitally essential to their economic existence,” he mused. For nation-states, that meant the support of international bodies like the fledgling United Nations with the hopes of creating a world where “we settle all international differences at the conference table.” For individuals, it meant the freedom of travel extolled in A King in New York, the same freedom on which Chaplin’s own fortune rested.

For Chaplin, being a citizen of the world meant thinking of his allegiances in international rather than local terms and of thinking equitably about nations and individuals alike. His was an economically progressive internationalism, even a populist internationalism. “The monopoly of power is a menace to freedom,” he has his radical alter-ego declare in A King in New York, arguing against consolidated power in companies and nation-states alike. It was a sentiment closely reflected in Chaplin’s own statements off the screen. “I believe in liberty—that is all my politics,” he told the press at the time of his exile. Chaplin was undoubtedly an idealist in his outlook, but that idealism was based in a tangible reality: once, he himself had actually succeeded in bringing the world together, if only in laughter.

Featured Image credit: Statue of Charlie Chaplin in front of the Alimentarium on the Vevey, Switzerland lakefront promenade. Henk Bekker from Copenhagen, Denmark, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Remembering Charlie Chaplin, citizen of the world appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers