Oxford University Press's Blog, page 368

May 12, 2017

Punishing Peccadilloes? Illicit sex at the early Stuart courts

At the Tudor and early Stuart royal courts, the careers of influential politicians and courtiers often depended on the preferences of the monarchs: being in the king’s good graces often mattered as much or more for advancements than ability and training. The personality and quirks of the rulers affected many aspects of a courtier’s life, including what today might be considered the most private: their sex lives. When King James I died in 1625, ambitious persons jostling for positions in the formation of Charles’s court would soon learn that the son had different tastes from the father, and expected different behaviors from those around him. While James mostly ignored or tacitly accepted the philandering of his courtiers as long as they kept up a modicum of discretion, Charles was not so forgiving. Under his reign, courtiers soon learned that they had to “keep their virginities,” or “at least lose them not avowedly,” as one courtier wryly remarked. If Charles found out, offenders could face serious consequences.

Sex outside of marriage constituted a criminal offense during the early Stuart period. Crimes like adultery and fornication were punishable by both secular and ecclesiastical courts. Adulterers could be imprisoned, whipped, put in the stocks, fined, and forced to do public penance. The nobility tended to be largely shielded from the strong arm of the law of church and state: it was rare that members of the elite were legally charged with sexual offenses. That did not mean that they could not face consequences for their actions: men and women serving at the royal courts were instead punished directly by the monarch.

Coming to England after the austere period of the ageing and ill Queen Elizabeth, Scottish King James and his queen introduced a rather boisterous courtly culture. Their celebrations gave the court a reputation for debauchery, although historians have often overemphasized it in the past. James’ courtiers did not necessarily engage in more instances of illicit sex, but the king’s reaction to them certainly signaled a relaxing of the strictness and severity Elizabeth had enforced. Where Elizabeth had both imprisoned and exiled courtiers who engaged in illicit sex, James tended to look the other way, as long as those involved had not committed additional crimes. Men like William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, experienced the differences first hand. In Elizabeth’s reign, Pembroke impregnated one of the Queen’s maids of honor and then refused to marry her. He was imprisoned for a time, and then exiled from court for the remainder of the reign. In James’s reign, Pembroke returned to court, and to royal favor. Although he had an affair with his first cousin, the writer Mary Wroth, and even had two children with her, he suffered no negative consequences at James’s court as a result.

Portrait of King Charles I in his robes of state, after an original by Anthony van Dyck. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of King Charles I in his robes of state, after an original by Anthony van Dyck. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.King Charles, a highly principled and stubborn man, firmly believed that he, his family, and his court should serve as a model for his subjects, and reflect the benign –but absolute – rule of the patriarch and sovereign. Charles introduced a strict court protocol, limiting access only to those who had the proper credentials, and organizing his days in minute details. Passions, drunkenness, and sexual improprieties should be banished from an orderly court, in Charles’s view. Sir Henry Jermyn, Queen Henrietta Maria’s Vice Chamberlain, would learn the consequences of testing King Charles’s lack of understanding for sexual missteps. When Eleanor Villiers, a maid of honor, found herself pregnant, Charles set about to investigate what had happened. Eleanor told the king that Jermyn was the father of her unborn child. Jermyn admitted to the unlawful sexual relations, but, like Pembroke a generation earlier, refused to marry her. Also like Pembroke at the Elizabethan court, Jermyn found himself behind bars for several months. Then, he had to leave England altogether for two years, before Charles begrudgingly allowed him back, largely as a result of the queen’s lobbying for his cause. Eleanor had to leave court and never returned.

Interestingly, the king appears to have made an exception for his favorite, George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, who had also been the last great favorite (and probably lover) of King James. Buckingham was a well-known womanizer, who even managed to convince Charles to appoint his mistress as a lady-in-waiting to the reluctant queen. Charles accepted Buckingham’s behavior mostly because he was the king’s closest friend and unshakeable ally. During the three years between his ascension to the throne and Buckingham’s assassination in 1628, Charles always stood by his friend, even at great political and financial cost.

Charles’s acceptance of Buckingham’s peccadilloes did not extend to the duke’s sister-in-law, Frances Coke Villiers. She was the wife of John Villiers, Viscount Purbeck, Buckingham’s elder brother. After her husband succumbed to mental illness, Lady Purbeck took a lover and gave birth to a son. The scandal broke at the very end of King James’s reign. While James, true to form, initially hesitated to punish Lady Purbeck, an outraged Buckingham insisted. The ill and dying James eventually acquiesced, and an investigation began. After James’s death, Buckingham, now aided by an equally outraged King Charles, worked to punish and shame his wayward sister-in-law. He would find it surprisingly difficult, as Lady Purbeck simply refused to accept her punishment. After Buckingham’s premature death, Charles continued to pursue her, and she continued to refuse to acquiesce. Charles was a stubborn man: once he had his mind set on a matter, he rarely changed it. He strongly disliked illicit sex, but he disliked challenges to his authority even more. The equally stubborn Lady Purbeck managed to do both, albeit at great cost.

Featured image credit: 16:58 Hampton Court Palace by brian gillman. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Punishing Peccadilloes? Illicit sex at the early Stuart courts appeared first on OUPblog.

The best baby money can buy: are you sure about that?

Take a look at the back page advertisements in any college newspaper. Dotted among the classified ads, there will invariably be an invitation or two to male undergraduates to sell their sperm. It’s an easy and hardly arduous way to make money, and pretty speedy too. Masturbate, ejaculate, hand over the results, and you’re on your way with a little money in your pocket.

Go online and you’ll find many sperm banks seeking donors as well as selling their product. Sperm banks are now part of the reproductive landscape, with Denmark and the USA as the leading providers. Sperm from those with sought-after talents or other desirable characteristics is more expensive, and needless to say the gap between the cost of donating and the cost of accessing a donation is vast. On average, donors are paid $35-$50 per specimen in the US, and about £35 in the UK. The buyer, however, is looking (and that’s just for the product) at around $400 at the low end, rising to about $1,000; in Europe you’re looking at anything from €70 to €750, depending on whether the donor remains anonymous. Sperm from an identified donor costs a lot more than anonymous sperm, and one donor’s donation can potentially service multiple customers. In Denmark, the largest sperm market, the industry turned over 1 billion Danish krone ($152m) in 2012 alone, and one recent report anticipated that by 2025, the global sperm bank market will be valued at US$4.96 billion. Running a sperm bank is clearly a profitable venture, and make no mistake, this is a for-profit industry.

The modern sperm bank emerged in the 1980s, but artificial insemination (or as it was known in the inter-war period, eutelegenesis, a fantastically science fiction-y name) certainly isn’t new. Artificial insemination by homologous donor, which used the sperm of a woman’s partner, had been tried in the mid-nineteenth century, but the horrific slaughter of young men in World War I got people thinking about the possibility of insemination by donor. In his 1935 book Out of the Night, geneticist Herman J. Muller (who would go on to win a Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1946) proposed active intervention in reproduction “to rear selectively–or even to multiply–those embryo which have received a superior heredity.” The idea was one among many in the then popular science of eugenics which looked to improve the human stock. Muller argued that actively selecting from the “best” in the population would raise the level of physical and intellectual fitness in the population. His plan sputtered at the time but as reproductive technologies advanced, Muller returned to the idea in the early 1960s.

Spurred by the first successful freezing of sperm shortly after World War II, Muller teamed up with a wealthy Californian eyeglass lens manufacture, Robert Graham, who bankrolled the venture. Muller and Graham fell out, but after Muller’s death Graham founded what he called the Repository for Germinal Choice in 1971. It was a highly exclusive venture, collecting and freezing only the sperm of Nobel Laureates, and it closed its doors in 1999. It wasn’t too long, however, before entrepreneurs realized there was money to be made in this venture. Sperm banks have since proliferated. Sperm from those with sought-after talents or other desirable characteristics remains the most desirable and therefore more expensive, with anonymous sperm (not legal in some countries) being the cheapest. One of the main reasons the US and Denmark lead the field is because both these countries allow anonymous donorship.

Muller and Graham, and many others, dreamed of perfecting not just a science, but the human race. But what does that look like on the ground? What traits do people think they’re buying? People dream of parenting the next great athlete or musical super-star, just as Muller and Graham fantasized that the offspring from their venture would grow up to win Nobel Prizes. Even if this were possible (and geneticists’ warnings that it’s not fall mostly on deaf ears), the commercialization of baby-making allows the affluent to exercise a choice unavailable to the vast majority. They may end up disappointed when their child fails to become the next Stephen Curry, but the illusion of choice is powerful. Artificial insemination is without doubt a boon to those who can’t conceive and to same-sex couples, but there are ethical issues that remain unresolved, and as long as artificial insemination is driven largely by profit, nothing will change.

Featured image credit: sperm egg fertilization sex cell by TBIT. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The best baby money can buy: are you sure about that? appeared first on OUPblog.

May 11, 2017

What to do with a simple-minded ruler: a medieval solution

The thirteenth century saw the reigns of several rulers ill-equipped for the task of government, decried not as tyrants but incompetents. Sancho II of Portugal (1223–48), his critics said, let his kingdom fall to ruin on account of his “idleness,” “timidity of spirit,” and “simplicity”. The last term, simplex, could mean straightforward, but here it meant only simple-minded, foolish, stupid. The same term was used to describe the English king Henry III (1216–72), as well as John Balliol, the hapless king of Scotland (1292–96) appointed by England’s Edward I. As the elites of these kingdoms knew too well, it could happen on occasion that a man rose to office—whether he had been born to claim it, had won the right to hold it, or had found it thrust upon him—who did not have the intelligence to wield power.

Such a situation was dangerous, for subjects would suffer. In Portugal, it was claimed that Sancho’s inability to govern had allowed Church liberties to be attacked, women to be defiled, and the common folk to be oppressed. England’s Henry III had frittered away his resources, monies needed desperately to maintain his government; the result, it was claimed, was that Henry did not even have the cash to buy food and drink for his household and had turned to seizing victuals from his people, leaving them impoverished. The subjects of John Balliol had, perhaps, the most to fear from their king’s simplicity: John was incapable of standing up to Edward I, when a stand was needed urgently to defend his people from the bullying English king.

The people of Portugal, England, and Scotland knew of a potential solution to the problem of their simple-minded rulers: the rex inutilis theory (literally, “useless king”). This was a tenet of Church law that provided, when a bishop was too infirm to fulfill his duties, for the appointment of a coadjutor to exercise power on his behalf. The theory could be applied to lay rulers too, though it addressed here the problem of incompetence rather than infirmity.

King John, his crown and sceptre symbolically broken and with an empty coat of arms as depicted in the 1562 Forman Armorial, produced for Mary, Queen of Scots. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

King John, his crown and sceptre symbolically broken and with an empty coat of arms as depicted in the 1562 Forman Armorial, produced for Mary, Queen of Scots. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.It was the pope who held the power to pronounce a king rex inutilis. The papal court was like a medieval United Nations: its interests ranged from the making of peace between polities to the proper conduct of rulers, and the well-being of all those under the Church’s care. To this end, the pope had a mighty moral weapon in his arsenal: he could depose rulers and free subjects from their oaths of fealty or, as in the case of a rex inutilis, take effective power from his hands.

This supreme authority was utilised by Innocent IV in 1245 to pronounce Sancho II rex inutilis. Innocent was responding to the complaints of Sancho’s subjects, though the decision was eased by Sancho’s failure to advance the ongoing war against the Muslim rulers of southern Iberia, a war invested with a high priority by the papacy. The subjects of other foolish rulers could not be so confident of papal sympathy. The pope was never likely to act thus against England’s Henry III, for example, a papal vassal who, it was hoped, would lead an army to conquer Sicily on the papacy’s behalf.

What, then, was to be done? In England, and later in Scotland, a group of bishops and barons took matters into their own hands. In 1258, a gang of England’s barons marched on the King’s Hall and forced a cowering Henry III to hand the reins of government to a council. Although Henry recovered power briefly, he was soon defeated in battle by Simon de Montfort, earl of Leicester, who established a new council to rule the kingdom on a permanent basis. The council only lasted 15 months, however, for its baronial leaders were cut down in battle in 1265. This episode, in which subjects sought to solve the problem of an incompetent ruler by seizing power and establishing conciliar government, has been justifiably called the first English revolution.

Such a move was completely radical. There was no ideological framework authorising subjects to remove their ruler (this right lay solely with the pope), let alone to replace the existing system of government. Those seizing power were driven by a sense of urgency, the belief that “something must be done,” rather than by theoretical justifications. This meant that those revolutionaries tasked with producing a justificatory case—the Montfortian bishops and prelates—faced a near-impossible task. They had to produce arguments from scratch, in the crucible of political crisis. Despite their prodigious learning, they could find no persuasive precedent, biblical or historical, that justified a revolution.

This was one instance, albeit extreme, of the many attempts made in the Middle Ages to constrain rulers whose inability to rule justly and wisely threatened the well-being and liberty of their subjects. “For since the governance of the realm is the safety or ruin of all,” argued the Montfortians, “it matters much whose is the guardianship of the realm; just as it is on the sea, all things are confounded if fools are in command.”

Featured image credit: Detail of a miniature of John, king of Scotland, being brought before Edward I. Public Domain via the British Library.

The post What to do with a simple-minded ruler: a medieval solution appeared first on OUPblog.

Which fictional detective are you?

The classic Golden Age of Detective Fiction in the 1920s and 30s brought us such legendary characters as Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple and Hercule Poirot, and detective stories on page and screen have kept audiences guessing ever since. How often do you solve the mystery before the story ends? Do you figure it out before the fictional detectives or do they beat you to the punch?

If you fancy yourself as a bit of a detective, find out which fictional sleuth you might be in our quiz.

Featured image credit: “ƎVITƆƎTƎᗡ” by allen. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Which fictional detective are you? appeared first on OUPblog.

May 10, 2017

Monthly gleanings for April 2017

The previous post on Nostratic linguistics was also part of the “gleanings,” because the inspiration for it came from a query, but a few more tidbits have to be taken care of before summer sets in.

Sleeveless errand

(See the post for 26 April 2017.) Skeat’s idea that sleeveless means “imperfect; hence poor, like a garment without sleeves” does not go much farther than Horne Tooke’s suggestion that sleeveless should be understood as “without a cover or pretence.” Skeat dismissed Tooke’s idea as making little sense, but the difficulty lies elsewhere. We have to find out where it was bad, dangerous, or silly to wear a sleeveless piece of clothing. Stephen Goranson wrote me a letter and cited several examples in which sleeveless referred to knights-errant or arrant. In some way, those examples, though late, may confirm the idea that the figurative sense of sleeveless emerged in connection with chivalry. Also, perhaps errant evoked the idea of errand. But many details remain hidden. As for the joke on bootless—sleeveless, I thought of it too! I even looked up capless, hatless, and shoeless, but found nothing of any use.

A kindhearted knight errant on a sleeveless, helmet-less, and armor-less errand.

A kindhearted knight errant on a sleeveless, helmet-less, and armor-less errand.Swedish lem

The question runs as follows: “Swedish lem for ‘penis’ or any sense of ‘member’: ‘member of an organization or the human body?’ Is lem ‘penis’ perhaps a euphemism?” The answer depends on how we define “euphemism.” Unmentionables for “trousers” is certainly a euphemism, but is tool for penis also a euphemism? People are surprisingly imaginative when it comes to coining synonyms for the names of the genitals, but some such coinages are really anti-euphemisms, so much so that in the modern editions of folk tales, rooster has superseded cock (fortunately, cocktail and cockroach have survived). The Latin for “penis” is membrum virile. This phrase may be the source of limb, lem, and so forth in the European languages.

Very little is new under the sun

Americans are well aware of the filler you know. It is an indestructible weed. Since I have no regular contacts with British speakers, I cannot judge to what extent this weed has choked their communication, but the place of origin of you know is England. I was amused to see it in Little Dorrit (1857). “He wants to know… you know,” said a member of the Barnacles family about the feckless Arthur Clennam (I am quoting from memory). Like Thackeray, Dickens was extremely sensitive to slang and recent usage. By 1855, you know may not have bloomed into a pest it has become now. But in Notes and Queries for November and December 1879, the purists complained bitterly about the phrase and tried to explain it: “There is doubtless a psychological reason for even the most trivial expression. A man desires to place himself en rapport with his interlocutor, to please or conciliate him; and from some such half-conscious motive he says ‘you know’ or ‘of course’ even when the words are irrelevant. Then comes Habit, with her chains, and he says it still oftener and less appropriately. Habit? Yes, and convenience too; for with the cultivated as well as with the uncultivated it is found extremely convenient to have some facile word or phrase in the mind, which will come without thought to the lips, and round off a sentence in no time.” Modern specialists in sociolinguistcs have not said anything more profound. Here are the examples given by another correspondent. They are divided into “superfluous” and “aggravating”: (1) “We were staying at Mrs. Smith’s, you know, and we went in the waggonette, you know, to the top of the high hill, you know, to see the sun set, you know” and (2) “No, he is not in London; he is somewhere else, you know” and “She mentioned that affair, you know, of poor Frank’s, you know.” Yes, indeed, that is exactly what I hear from morning till night (except waggonette, of course). (And ah, how well those people wrote! One of the discussants remarked that people use fillers without malice prepense. I wish I could express myself so.)

Know thyself, you know.

Know thyself, you know.And this is how we speak…

“In these cases, students, no matter their status, no matter if they are an athlete, must be held accountable.” (In the case under discussion, they were indeed an athlete in trouble.) “As the daughter of a NWS pilot, we understood the rules for traveling on a pass….” (Is this the honorific plural or a case of politically correct deafness?) “This past week, a friend described to me their experience…. For my friend, it meant popping into various student groups, where they felt out of place or intrusive.” Obviously, someone who can split into several persons should look intrusive. But there is a reward: the statement is gender neutral, and we’ll never guess whether the fried was (were?) a man of a woman. The note is titled: “Striving for diversity is great but challenging in practice.” The same holds for pluralism.

They are an athlete.

They are an athlete.Last but not least

Many thanks for the warm personal comments. It was most gratifying to discover that some of our readers like the illustrations. I remember distinctly how they appeared in this blog. I wrote something on the origin of the word teetotal and mentioned the existence of a monument to the first teetotaler (in Preston, I believe), and, lo and behold, a reader from Lancashire sent us a photo of the statue. I asked the editor whether we can post it. She (they?) said “yes,” and this is how the idea of illustrating every text was born. First we posted one picture, then two, and later three and occasionally even four. As a rule, I try to find such pictures as are either attractive or can be used as comments on the story (often just for fun) and send the suggestions to the editor. We exchange several letters, choosing the most attractive “images” that have not been copyrighted (a perennial problem), select one for the header, and agree on the outcome.

I do not always respond to the comments. Sometimes it happens because I agree wholeheartedly with what I find in the readers’ remarks (so that there is no need to beat/flog a willing horse), sometimes because I have nothing quotable to say or simply don’t know the answer (for instance, I am also a bit puzzled by the word order in some place names: why, for instance, the River Thames but the Mississippi River: yes, perhaps the French influence in the first case, but I was unable to find an authoritative explanation). What saddens me is the appearance of late comments after very old posts. I, naturally, can catch them only by chance and usually have no idea that they exist. When I make mistakes, it is a pleasure to be hauled over the coals almost at once, for nothing is more irritating than being ignored. Doing this work is the source of great joy to me and, I hope, to everybody else, including the hard-working editors at OUP.

Image credits: (1) “Grandville: Illustration to Don Quixote (Book 1, Chapter 52), 1848” by Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard Grandville, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) “Roman-mosaic-know-thyself” by Unknown, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3)

“The Discobolus Lancellotti, Roman copy of a 5th century BC Greek original by Myron, Hadrianic period, Palazzo Massimo alle Terme” photo by Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Featured image: “Westminster, Big Ben, London” by eisteddfod_37, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Monthly gleanings for April 2017 appeared first on OUPblog.

Preparing for CISTM15 with the CDC

This weekend, the 15th Conference of the International Society of Travel Medicine (CISTM15) will be hosted in sunny Barcelona. It is a historical moment for the International Society of Travel Medicine who will also be celebrating its 25th anniversary during the conference on Tuesday, 16 May. The latest findings in travel medicine will be presented in a range of lecturers, workshops, and debates.

We asked Phyllis Kozarsky, Professor of medicine and chief medical editor for the CDC Yellow Book 2018, a few questions around the connections between travelers and antimicrobial resistance, environmental crises, new vaccines and pre-travel medical checks, and extreme altitudes.

What is the role of travelers in the spread of resistant organisms, and what can travelers do to prevent the spread of antimicrobial resistance?

In recent years, there have been reports of travelers becoming infected with drug-resistant travelers’ diarrhea and spreading it in their home countries. Using antibiotics to treat diarrhea while traveling increases a person’s risk of acquiring a drug-resistant organism, and a traveler can decrease this risk by limiting the use of antibiotics. Travelers’ diarrhea almost always goes away by itself in a couple of days, so travelers may want to just manage their symptoms with bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol or Kaopectate) or loperamide (Imodium) for mild or moderate cases. For severe diarrhea, however, antibiotics can be an important tool to prevent someone’s business travel or vacation from being ruined.

How might environmental crises (such as natural disasters or air pollution) impact a traveler’s health, and what precautions can they take?

Natural disasters present physical risks to travelers (damaged infrastructure, downed power lines) and strain local health systems. Flooding from a natural disaster can compromise water quality and prompt outbreaks of waterborne diseases such as cholera or leptospirosis in areas where these diseases are a risk. As much as possible, travelers should avoid areas that have experienced a natural disaster unless they are part of a group that is engaged in aid activities and have received appropriate health guidance. If travel is unavoidable, they should know the risks, ensure they have access to a health kit, and have a plan for getting medical care if they need it.

Pollution by Jason Blackeye. CC BY 2.0 via Unsplash.

Pollution by Jason Blackeye. CC BY 2.0 via Unsplash.Air pollution has decreased in many parts of the world but is increasing in some industrializing countries. Polluted air can be impossible to avoid, but the risk to healthy short-term travelers is low. People with pre-existing conditions such as asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease should limit strenuous or prolonged outdoor activity in polluted areas.

What are some significant ways that extreme altitudes can affect travelers who aren’t used to these conditions?

Travelers who go from a low altitude to a very high altitude (higher than 8,000 feet [2,500 m] above sea level) quickly can develop altitude illness. Symptoms are similar to those of a hangover—headache, feeling tired, nausea, and vomiting. Mild cases should go away after a few days, but if symptoms get worse at the same altitude, the traveler should descend to a lower altitude. Severe manifestations of altitude illness can include symptoms of extreme fatigue, confusion, loss of coordination, and being out of breath. Travelers with severe complications should descend to a lower altitude right away.

The best way to prevent altitude illness is to ascend gradually so that travelers can become accustomed to the decreased oxygen level. If the itinerary doesn’t allow gradual ascent, medications are available that can prevent altitude illness.

Mountain by Georg Nietsch. CC BY 2.0 via UnSplash.

Mountain by Georg Nietsch. CC BY 2.0 via UnSplash.How is the development of new vaccines going to affect people’s pretravel medical checks?

As new vaccines become available, clinicians will need to carefully weigh the risks and benefits of vaccination in the context of the traveler’s risk. For example, a new cholera vaccine was recently licensed in the United States. Cholera can be severe, but it is extremely rare in travelers, and areas of active transmission may be limited to specific regions within a country. When counseling a person who is traveling to a country where cholera is a potential risk, the clinician will need to assess the person’s risk of cholera, risk of developing severe disease, and whether there is active cholera transmission at the destination.

It remains true that the vast majority of travel-related illnesses cannot be prevented with a vaccine. There are ongoing efforts to develop vaccines to prevent other travel-related illnesses, but the process can take years. Travelers should be counseled on preventative behaviors and encouraged to take action to protect their health during their trip.

The 15th Conference of the International Society of Travel Medicine (CISTM15) starts on Sunday 14 May 2017 to 18 May 2017 in Barcelona, Spain.

Featured image credit: Launching by Dominik Scythe. CC BY 2.0 via Unsplash.

The post Preparing for CISTM15 with the CDC appeared first on OUPblog.

Fame, race, Nella Larsen, and Nella the Princess Knight

Certainly my oddest moment as a scholar of the biracial woman novelist Nella Larsen (1891–1964) was the day I ran across her in the guise of a pink-clad children’s cartoon character, profiled in the New York Times.

The unusual name “Nella” drew my eye to Nella the Princess Knight, but as I read further, the character’s similarities to the literary figure multiplied. Like the novelist, Nick Jr’s new heroine has a black father, a white mother, and a baby sister, and she lives in a multiracial community. Also like Larsen, who despite racism and sexism had three different professional careers (nurse, librarian, and novelist), the Princess transforms herself and fights. When someone needs saving, she recites a little poem, her magic necklace glows, and Princess Nella becomes a Princess Knight, armored and carrying a sword, to mete out justice.

Such links between a high modernist and the protagonist of an educational program for three to five-year-olds could be pure coincidence, or the little joke of a rogue English major toiling in some fluorescent-lit writers’ room. On my inquiry, Nickelodeon representatives stated unequivocally that no homage or reference was intended—they liked, rather, the alliterative N-sound of “Nella” and “Knight.” But whether accidental or intentional, these uncanny similarities raise questions about the novelist’s canonical status. How famous is Nella Larsen, exactly? Does her reputation influence culture beyond the academy?

These questions are particularly interesting because Larsen is a “rediscovered” author, newly valued for her works’ germinal social critique. Quicksand (1928) and Passing (1929) are both psychological studies of middle-class black women, “New Negroes” who live in an urban, modern, and mass-mediated United States. Although they refer frequently to anti-black racism, these novels are not protest fiction in the received sense of the term: they do not make moral appeals. Indeed, their characters routinely mock traditional African-American anti-racist advocacy: “Uplift, sniffed [Quicksand’s autobiographical protagonist] Helga contemptuously, and fled before the onslaught of [her friend’s] harangue on the needs and ills of the race.”

Nella Larsen, photographed by James Allen in 1928, age 37. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Nella Larsen, photographed by James Allen in 1928, age 37. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Instead, Larsen’s works immerse readers in the complexities of black and biracial women’s experiences of colorism, misogyny, homophobia, and sexual repression. They teach readers, in other words, that black racial identification is not simple, and black women are often left off liberationist agendas. These themes have been increasingly well-received by critics and teachers. Since the late 1980’s, black feminist, queer, and psychoanalytic literary scholars have represented, polished, and responded creatively to Larsen’s insights, while Larsen herself became the subject of no fewer than three biographies. Today, Quicksand and Passing are included in full in market-dominating Norton Anthology textbooks, and widely available in many cheap classroom editions. Some very recent scholarship explores her works’ theoretical relevance to mixed-race and disability studies.

Both Larsen’s own goals, and those of recovery scholars, seem to have been accomplished, in other words. Not only has the canon been demonstrably diversified, but new areas of critical inquiry have been permanently opened. The world has changed.

This seemingly-complete revolution brings me back to Nella the Princess Knight, though. Whatever the cartoon’s relationship to the novelist, its creators likewise wish to advance more complex images of racial difference, trouble the gender binary, and generally reflect the true diversity of human experience. It’s instructive, therefore, to note what is not present in the cartoon. Translated thus into childhood kitsch, the pedagogy of subtle difference that motivated scholars’ recovery of Larsen reveals its stark limitations. To assert that gender and racial categories are overlapping and mutable is not to question those categories.

For one thing, the “Princess Knight” is still a princess; she gains masculine, martial behaviors, but also retains pink femininity. For another, she has few connections to black culture; despite her darker skin color, the character speaks a deracinated television English, hangs out with a white male friend, and displays a very long, flowing hairstyle more typical of European than African descent. In her world, girls are always at least a little girly, and heroes always somewhat white. There are real limits to what this “Princess Knight” can overcome.

Are Larsen’s novels similarly limited? Do they tend to preserve gender and racial hierarchy even as they describe and explicate boundary-crossing? We routinely ask similar questions of more established canonical authors, such as Mark Twain and William Faulkner, so perhaps it’s time to examine Quicksand, Passing, and the stories in similar wise.

It’s also true, though, that Larsen’s black women boundary-crossers, unlike Huck Finn or Jake Barnes, are met not with love and recognition, but with killing violence. Most famously, Passing’s Clare Kendry, a glamorous and courageous light-skinned woman who passes for white, is literally pushed out the window by another black woman, to expire on the snow like a dropped cigarette.

Many scholars identify Passing’s final scene as conservative: a danger to the social order was eliminated. Yet we may also read Larsen as avoiding the “Princess Knight” syndrome here. Her novels’ negative, disturbing endings leave us, not with hero(in)es to emulate but with a hole, an empty place to spur thinking. They don’t tell us that we can be both black and white, both masculine and feminine; instead, they ask us to think about what is missing from our schemata of identity.

Featured image credit: Joan of Arc depicted in The Maid of Orléans by Jan Matejko (1838–1893). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Fame, race, Nella Larsen, and Nella the Princess Knight appeared first on OUPblog.

May 9, 2017

The free press in the “Good War”

When the president declares war on the media, dubbing it the “enemy of the people,” the first instinct of its defenders is to take to Twitter to emphasize how many reporters have sacrificed their lives in reporting the news. The second is to hark back to two eye-catching events: the Vietnam War, when uncensored media reporting exposed the lies about how the conflict was being waged; and the Watergate scandal, when the Washington Post helped to uncover the massive attempt to cover-up the Nixon administration’s illegal bugging of the Democrats.

Yet, on close inspection, World War II offers a much more instructive example, not only for reasserting the necessity of a vibrant free press, but also for convincing critics of this basic fact.

Even the media’s staunchest adversaries tend to laud its role during World War II. According to popular myth, the 1940s were a time when America’s “golden generation” of reporters didn’t carp or criticize. Rather, legendary figures like Ernie Pyle, Walter Cronkite, and Ed Murrow patriotically joined the “team,” helping to forge a domestic consensus that endured until Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan were destroyed.

When the legend is stripped away, a much more intriguing story emerges. There can be no doubt of the bravery of these World War II reporters. They flew on bombing missions to Germany and landed on the D-Day beaches in Normandy, they froze during the Battle of the Bulge and sweltered on Iwo Jima and Okinawa—and all the time they were armed with little more than their typewriters.

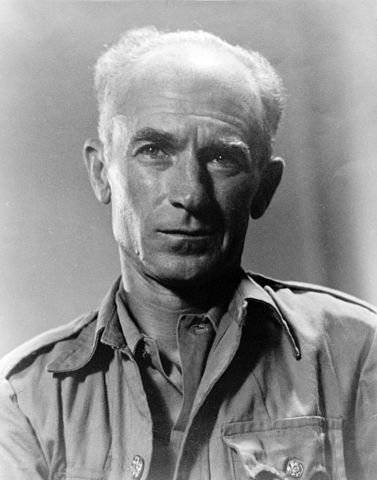

Ernie Pyle, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing right by Milton J. Pike. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Ernie Pyle, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing right by Milton J. Pike. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Only rarely, however, did these reporters become meek mouthpieces for official propaganda. Some saw their job as investigating the reason for critical shortages in weapons, supplies, and troops. Others sought to expose obvious military mistakes, from friendly-fire incidents that killed hundreds of GIs to ill-planned offensives that threatened disaster. Even Ernie Pyle, who spent much of his time writing about the average soldier’s daily battle to survive, could be a thorn in the military’s side, exposing false official claims that an easy victory would soon be achieved.

When these reporters did pull their punches, their motive was invariably to avoid handing sensitive information to the enemy. But they only knew what information was sensitive because officials, rather than angrily dismissing their criticisms, still decided to take reporters into their confidence. General Dwight Eisenhower, in particular, made a habit of briefing his correspondents before major operations, justifying his candor with a shrewd insight: “Every once in a while I like to tell you fellows something [strictly off the record], because you might hear it from somebody else, and if I tell you, it shuts you up!”

The result was a healthy relationship between the two sides, although it was rarely harmonious. Generals, like politicians, rarely relish having their mistakes aired in public. Nor do correspondents cherish having their hard-won copy being eviscerated by a censor.

These tensions existed even when the stakes were as a high as in World War II. The difference then was not that the reporters were more patriotic. Instead, senior officers were prepared to take the media into their confidence, treating them as allies, not enemies. Crucially, senior officers were also prepared to listen to well-documented critiques of their blunders, recognizing that there is often a good reason for the media’s contentiousness: even the most well-oiled machines—which America’s World War II military surely was—make mistakes, and that these can only be rectified when they are exposed. Which is the main job of a vigorous free press.

Featured image credit: “Into the Jaws of Death—US Troops wading through water and Nazi gunfire” by Robert F. Sargent. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The free press in the “Good War” appeared first on OUPblog.

The legacy of William Powell and The Anarchist Cookbook

In February 1971, Lyle Stuart, known for publishing racy, unconventional books, held a press conference to announce his latest foray into testing the limits of free speech. With him was William Powell, the son of a diplomat and a former English major at Windham College, who had written what would become the most infamous of mayhem manuals: The Anarchist Cookbook. At the event, a heckler set off a cherry bomb as Stuart and Powell spoke against surveillance and censorship attempts by the federal government. Within days, The Anarchist Cookbook had become what the nineteenth-century anarchist Johann Most–himself an author of an infamous weapons manual–called a “literary Satan,” broadly associated with armed resistance.

In his recently released documentary American Anarchist, director Charlie Siskel conducts a lengthy interview with the sixty-six-year-old Powell who died last year of a heart attack, just before the film’s release. Siskel’s goal is to get Powell to express remorse for writing The Anarchist Cookbook and to hint at a larger theme of atonement for the 1970s’ days of rage, when small underground revolutionary groups turned to bomb-making as an illicit craft. Such a theme is appropriate to the rolling anniversaries of the long Sixties, as the participants enter their twilight years and assess their legacies. This history is strongly suggested in American Anarchist, but it is mostly a very human story of personal culpability for the past. Siskel keeps pushing Powell to express a mea maxima culpa for his youthful mistakes, leading to a cinematically satisfying climax, but his effort is ultimately thwarted by Powell’s meandering sense of the history and social implication of his own book. From his individual perspective, having left the United States and dedicated himself to a life of service, Powell is obviously unsure of what it all meant.

I briefly appear in this movie in a clip of a talk I gave. Siskel included this clip to show how Powell was facing increasing public exposure and pressure to feel regret beyond his few public statements disowning the book as youthful folly. But I am interested not so much in personal, or even political regret, as in radical speech’s complex history that led to The Anarchist Cookbook, and has given it such an astonishing longevity.

Although Powell said that he had written The Anarchist Cookbook in protest of the Vietnam War, it found a home with all kinds of rebellions and political persuasions.

I understand Siskel’s motivation to push for remorse. As I studied mayhem manuals, I often wondered whether the writers ever considered or felt regret for the unintended consequences of their dangerous information sharing. Most of these popular manuals are not written for practical use, but to demonstrate that, in a democracy with free speech protections, the writer can get away with thumbing a nose at the government or other powerful authorities by explaining how to build a bomb. The tenor is sometimes mocking and adolescent, as in the very dangerous “How to Make a Bomb in the Kitchen of Your Mom,” which appeared in the first issue of Al Qaeda’s online magazine and was used by the Boston Marathon bombers. The speech itself is a weapon, attempting to wildly inflate fears of a lawless, rebellious underdog, dangerously armed through easily understandable recipes. That someone might actually carry out dangerous experimentation with explosives or even build a bomb is not the most important initial consideration. And, in fact, only a handful out of millions of readers will ever attempt to use the instructions and almost never effectively.

With its unreliable DIY ideas for making bombs, handling guns, growing and cooking drugs, hacking phones, and other kinds of illicit crafts, The Anarchist Cookbook was not the first manual to challenge social tolerance for this distinct form of speech. The book itself was jerry rigged from other official and unofficial sources of information, like police books on bomb disposal and reprints of military manuals. Nothing in it was new, but it couched the information in an abstract political diatribe about resistance to the government, for whatever reason. Its aim was to arm the people by freeing information, much along the lines of Abby Hoffman’s satirical Steal This Book, published in the same year.

Although Powell said that he had written The Anarchist Cookbook in protest of the Vietnam War, it found a home with all kinds of rebellions and political persuasions. It became a broad symbol of armed resistance and anomic rebellion, even though it was very rarely proven to have led to any actual crimes. However, just the mention of The Anarchist Cookbook, either by police investigators or the news media, was enough to conjure instant criminality and agents of chaos.

One of the disturbing features of The Anarchist Cookbook is its guilt by association. Many discussions of the book tie it to a series of mass murders. The implication is that the book inspired the murderers who owned it, like Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh, school shooters Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, and Jared Loughner, who attempted to kill Representative Gabrielle Giffords. But these crimes do not directly involve the book at all. Sometimes, the book is claimed to be an actual source of such murders: a complete falsehood. The Anarchist Cookbook is an easy symbol of malevolence, chaos, and social deviance for the media, politicians, terror consultants, and police investigators, who beg the question of whether reading a book causes a person to murder his neighbors. This guilt by association has serious implications for the courts, where reading materials, like The Anarchist Cookbook, have historically been used to paint a damning psychological portrait of the (sometimes innocent) accused. We do not understand enough about reading inspiration to make such claims in courts of law.

Should Powell have felt guilty for writing The Anarchist Cookbook? Should he have repented in his final days and more fully atoned for his destructive youthful passions through a cinematic confession? Because of the mythologization of The Anarchist Cookbook and its dubious associations, the basis for Powell’s guilt remains mysterious. As Siskel’s American Anarchist probes its subject for psychological avoidance of the sins of the past, it leaves the question: What was William Powell guilty of?

Featured image credit: Anarchy by Jeff Meyer. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post The legacy of William Powell and The Anarchist Cookbook appeared first on OUPblog.

Reading landscapes of violence

As we drove to a hotel in Manesar in the state of Haryana for a meeting with our Governing Board the memory of the massacres against the Mewatis in 1947 returned. The hills in the distance were those to which the Mewatis had fled after their villages were attacked by mobs. Women did not even have the time to put out their hearths – among them were those who would soon give birth in the open, but not those had been abducted by the mobs. The National Archives has a list naming the abducted women – Mewati women comprise the largest single group. The mobs comprised neighbours, not strangers who joined the AJGAR caste alliance of Ahirs, Jats, Gujars, Rajputs. Dalits also participated in the land grab that followed.

The Mewatis sought shelter on the Kala Pahar, the Black Mountain, as the Aravallis are called, but the very next day there was firing from an aircraft sent by the Bharatpur State. Azadi was no freedom but is instead locally called bhaga-bhagi (exodus) and kati (killing) in 1947.

The survivors sought refuge with their kin in British India or in Delhi’s many camps at Purana Qila, Lal Qila and Basti Nizamuddin. Even though they had not been part of the demand for Pakistan many Mewatis were prepared to now make the journey. It was Gandhi who reversed the tide – his famous speech at Ghasera affirmed the Meos’ right to their homeland. As he put it, they were its spinal cord.

There was phenomenal demographic change at the inaugural moment of the Indian state – organised killing in Mehrauli and in the large number of Mewati villages within Delhi. Mewati villages such as Raisena – one of the nine hills that Delhi is celebrated for – had already been colonised by the imperial city. Neighbourhoods of the city such as Jor Bagh, Nizamuddin, and Chandni Chowk were deeply affected by Partition.

Both the states of India and Pakistan internalised the idea of the perpetually insurgent Mewati from Persian statist histories written in the wake of the formation of the Turko-Afghan Sultanate in the late twelfth century.

In India, a strong concentration of Muslims so close to the new national capital was feared and in rehabilitation policy refugees (from across the border) were given priority over displaced persons. The Meos who wanted their old lands back got only inferior and degraded lands. Their status as a dominant caste was destroyed forever.

In Pakistan, the Meos were seen as a potential source of discontent and hence distributed along the border from Punjab to the Sind so as to defend the border as a “martial race.”

National boundaries created continuous trauma. I visited Pakistan for a lecture tour organised by Meos in Lahore, Islamabad, and Karachi. A young woman from Karachi spoke to me of her Mewati mother who died with the names of her brother and sister on her lips, not those of her children. A young lawyer who gifted his book in Urdu to me recounts in it his visit to India to meet his father’s sister and his visit to the Siva temple, a pilgrimage for Mewatis. For the Mirasis, the poet-musicians and genealogist-historians of the Meos, the journey to Pakistan seemed to have meant a death of poetic memory. None of the Mirasis I met could recite verses from the epics of their traditional repertoire. In their case it was as if the journey to Pakistan was the erasure for some of their cultural memory.

In Gurgaon, Sohna, and Taoru there is now a new world of clubs and resorts with golf courses and villas where precious ground water is harvested that will soon deplete peasant wells and even the single wheat crop will no longer be possible. Mewat (like Gujarvati and Ahirvati) has witnessed massive land transfer.

What is required is a ‘New Peasant Studies’ in both India and China quite different from the ‘Old Peasant Studies’ that developed in the wake of Maoism, as also of (Rural) Urban Studies that will cognize the new Empire of Metropolitan Cities.

Featured image credit: Seven Mewatis, originally published in Delhi. CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Reading landscapes of violence appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers