Oxford University Press's Blog, page 370

May 5, 2017

Are Americans in danger of losing their Internet?

It’s hard to imagine life without the Internet: no smart phones, tablets, PCs, Netflix, the kids without their games. Impossible, you say? Not really, because we have the Internet thanks to a series of conditions in the United States that made it possible to create it in the first place and that continue to influence its availability. There is no law that says it must stay, nor any economic reason why it should, if someone cannot make a profit from it. It exists because people, public institutions, and corporations want it, pay for its use by subscribing to an Internet service, and purchased a device that accesses it, such as a smart phone. As long as these communities can live with each other, we will have the Internet. Maybe.

American history teaches us that availability of the Internet is a precarious one, constantly undergoing good and bad changes and that routinely needs the attention of all three constituencies—citizens, public institutions, and corporations—to sustain it. Corporations are very active, because there are revenues and profits to be made off the Internet. Regulators and lawmakers are a bit less active, trying to keep up and deal with the corporations. And the least involved are the people. Normally, the history lesson is that the balance of involvement works “good enough,” but periodically everyone has to engage in an information policy issue more intensely than normal. We are at one of those times now.

After the 2016 national elections, the nation is trying to get back to the concerns of daily life. A new administration is picking up on issues placed on hold during the campaign; a new Congress is turning its attention to new policy issues, reflecting the nature of its political makeup, while federal regulatory agencies are busy as well. Lobbyists have returned to work on their clients’ interests. Citizens must do so as well, as historians consider them to be some of the most intense users of information in the world.

The role of the Internet is a subset of a bigger issue, that of the role of information in society. Facts were as important in shaping how the nation evolved as any other factor: democracy, good economy, education, immigrants populating our continent, and so forth. For over two hundred years, Americans promoted access to information because availability made it possible for them to thrive economically, to lead better quality lives, and to deal with the threats to the nation’s health, military security, and environmental conditions. We can skim off history its top lessons that to apply to the Internet today.

Seal of the former United States Department of the Post Office. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Seal of the former United States Department of the Post Office. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.One certainty is that Americans will continue to rely extensively on information to assist in all that they do. But, in so far as the role of information goes, the United States is at a crossroads, having to decide whether information stays roughly “more-or-less” as it has been or begins to make conscious decisions about what should change. Historical evidence—not cynicism—suggests that the United States will move incrementally through one information-related issue to another, changing its collective practices and policies in an evolutionary manner to satisfy whatever constituencies want or can give ground on. We have the experience of using PCs for over 40 years, computers for over 75 years, and telecommunications for over 150 years from the telegraph to the Internet. The discussion is bigger than just Republican vs. Democratic perspectives, because it involves all three constituencies, each of which is larger than any major political party. And people will take action in support of their viewpoints.

Taking proactive actions is not without precedence. The process by which the constitution was developed in the eighteenth century offers an exemplary precedent, but even then it was a two-stage process: the base document followed by a dozen amendments. Decisions were consciously made in support of the free flow of information. With the constitution in place and yet an entire governmental infrastructure to create from scratch, the Congress made it a high priority to establish the US Post Office, the nation’s first country-wide information infrastructure. It was easier in those days to be overt in policy matters as the number of people needed convincing to sign on to a policy was smaller and the number of citizens engaged in debates were more muted than today. The Revolutionary War Era was not a onetime event. Proactive action would be taken at other times, and even in today’s complex social and information ecosystem it still can be.

Passage of the Land Grant College Act (1862) was another one of those moments. What is now evident is that the genius of that law was not how Congress funded universities, but in crafting their mission. Universities had to have far more than an educational mission of teaching students. These had to create new information, innovative ways of doing things, and proactively put those developments in front of American citizens. That is why, for example, a national network of county agents climbed on their horses, hitched up their carriages, or drove their cars and pickup trucks and visited most, if not all, family farms in America over the next century. Much New Deal legislation in the 1930s offers other examples. In time, we may come to see some of the decisions of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) that opened up the Internet to growing swaths of the public in the 1970s-early 2000s as important milestones. The FCC did this as new tools became available which made using the Internet easier.

But history teaches one other lesson: if you want to keep your Internet, pay attention to what the national government and companies do, engaging in the political and economic activism, because that activity has always shaped access to information. Protecting it today is as important for the future of information in the United States as was the protection Americans gave to the Post Office for over two centuries. Most certain is that what gets done on the Internet will keep changing, for better or for worse, and that reality is driven by what the three constituencies do.

Featured image credit: “Laptop, Work” by Unsplash. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Are Americans in danger of losing their Internet? appeared first on OUPblog.

The less mentioned opioid crisis

You’ve probably seen the dramatic photo of the Ohio couple slouched, overdosed, in the front seats of a car, with a little kid sitting in the back seat.

Even if you haven’t seen that picture, images and words of America’s opioid overdose epidemic have captured headlines and TV news feeds for the last several years.

But there’s a different image seared into my mind, a mental picture of a different little kid and two adults. This one never made it into the news, but it’s just as real. I can’t get this “picture” out of my mind.

It took place in India, on 1 June 2014. The little boy in this scene had been suffering unbearable pain for most of his eight years, pain triggered by a severe genetic disorder. The hospital he was in, like most hospitals in India, had no morphine.

Eventually, the parents did the only thing they could think of to stop his pain. They killed him. Then they committed suicide, leaving behind a note saying they could not stand to watch him suffer any longer.

In this country, mention the word “opioid” and people think “overdose,” “abuse,” or “death.” But in much of the rest of the world, the problem is quite different: A massive shortage of available morphine for millions of people suffering in pain, people like this Indian boy.

Morphine costs just three cents a dose. It is safe, when used properly, and effective. Yet tens of millions of people around the world suffer in pain because of the lack of access to controlled medicines, according to the World Health Organization. That’s not just people at the end of life, but people who’ve had accidents or been the victims of violence, people with chronic illnesses, people recovering from surgery, women in labor.

In some countries, according to Treat the Pain, part of the American Cancer Society, the situation is truly desperate. Take Ethiopia, a nation of 90 million people. For that huge population, there is only one ward (with 10 beds) offering morphine in the entire country.

5mg/ml vial of Morphine Sulfate manufactured by Baxter Healthcare. Photo by Vaprotan. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

5mg/ml vial of Morphine Sulfate manufactured by Baxter Healthcare. Photo by Vaprotan. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The problem we face today is excessive regulations governing morphine and other “essential medicines.” Back in 1961, the world community adopted an international agreement called the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, which then set up the International Narcotics Control Board.

The board has two jobs. One is to control drug abuse and diversion. The other is to ensure access to opioid drugs for people in pain. Essentially, it only does the former. Yet failure to treat pain amounts to “torture by omission” in the eyes of some medical ethicists.

Clearly, as the tragic Ohio photo shows, there is a need to curtail abuse of opioids. But there is also, just as clearly, a need to make morphine and other powerful pain-relievers available to the millions of people who need them.

With all the other tragedies competing for the world’s attention – war, terrorism, dictators, economic problems – the lack of access to morphine never makes it to the headlines.

But it should. There is no question that we should try to keep powerful drugs out of the hands of would-be abusers and that we should provide much better treatment for people who become addicted.

There is also no question that a little boy in India should have had access to morphine. His death, and the deaths of his parents, didn’t make the news.

I wish it had.

Featured image credit: First Aid Kit by Tomasz_Mikolajczyk. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post The less mentioned opioid crisis appeared first on OUPblog.

Innovation in Aging: A Q&A with editor-in-chief Laura P. Sands

At the start of every emerging technology, at the heart of every scientific breakthrough, is an original idea that ignites like a spark. And soon, if we’re lucky, the spark spreads into an all-encompassing flame of ingenuity. This innovation is the key to progress and GSA’s newest journal Innovation in Aging is devoted to fanning the flame of progress in gerontology. In the interview below, the inaugural editor-in-chief Laura P. Sands discusses GSA’s newest journal and the future of gerontology.

How did you get involved with Innovation in Aging ?

Rosemary Blieszner, a colleague and a former President of The Gerontological Society of America (GSA), suggested that I apply for the position of Editor in Chief. The application process involved a letter of introduction. As I composed the letter, I became excited about the opportunities a new journal could capture. The new journal will publish innovative research on aging that is outside the scope of GSA’s current journals. The new journal also offers the opportunity to enhance readers’ understanding of journal content. Each article includes a blue box immediately beneath the abstract that describes the translational significance of the study. Who better to explain the importance of research on aging than scientists who study aging?

Describe what you think the journal will look like in 20 years and the type of articles it will publish.

Visually, we will strive to take advantage of its online format to increase readers’ interaction with journal content. For example, embedded search features will allow quick comparison of a study’s methods and results with other published studies. Advanced graphics will free researchers from presenting results in static two-dimensional formats. For example, presentation of results may include visualization of multiple processes simultaneously interacting. Description of methods could include visual presentations of experimental procedures to increase accurate translation of methods across studies. Topically, I expect that we will be moving away from research that focuses on single systems. Instead, research in 20 years will be describing interaction between complex systems. For example, we are likely to see more research that describes the complex interplay between biological, social, and environmental influences on aging. In addition, I expect we will see more international teams working together to tackle global challenges and opportunities of aging.

Laura Sands Courtesy of Virginia Tech/Logan Wallace. Used with permission.

Laura Sands Courtesy of Virginia Tech/Logan Wallace. Used with permission.How would you describe IA in three words?

Innovative – because the journal seeks to attract research that describes original principles, implements novel methods, assesses emerging technology, and describes innovative care pathways.

Interdisciplinary – because we will consider scientific articles representing expertise from multiple disciplines.

Immediate – because we strive to make a first decision within 30 days of submission and an article will be published online as soon as it is typeset. In addition, the Open Access model allows immediate online and free access to articles for every interested reader.

Do you think there are misconceptions regarding the journal? If so, what?

Innovation in Aging adopted the fully Open Access model of publishing. Two features distinguish the Open Access model from traditional subscription journals. First, readers have free, unrestricted online access to articles. Second, the journal does not have subscription fees; instead, the journal’s costs are covered by author publication charges. Research societies have widely adopted the Open Access model in the past decade. The most common Open Access journals in which GSA members publish include the BMC, PLoS ONE, and Frontiers journals. However, some scientists continue to have concerns about this model. One concern is that Open Access journals may be predatory. Qualities that distinguish reputable Open Access journals from predatory journals are as follows:

1. The journal is included in reputable databases.

2. The journal is owned by a scientifically reputable company or research society.

3. The editorial board includes scientific expertise required to thoroughly review manuscripts relevant to its mission.

4. The peer review process is clearly stated on the journal website.

5. The policies for human and animal subjects and conflict of interest are clearly articulated.

6. The journal has a Creative Commons Attribution License.

Another concern about Open access journals is that authors pay a publication fee. Innovation in Aging will waive the author publication fee for the first 200 accepted articles. Thereafter, 25% of author publication fees will be waived. A 2014 case study of an Open Access journal revealed that only 19% of authors requested waivers for author publication fees. A market survey commissioned by the GSA revealed that of respondents who published in Open Access journals, nearly half had their author publication fees covered by institutional funding.

Featured image credit: Steel Curves by Ricardo Gomez Angel. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Innovation in Aging: A Q&A with editor-in-chief Laura P. Sands appeared first on OUPblog.

Will there be justice for Syria?

The war in Syria has wreaked havoc on the lives of the Syrian people, and affected many others. Since the war began in March 2011, several hundred thousand people have been killed. Some 13.5 million people require humanitarian assistance, and over 10 million people have fled their homes – with 4 million fleeing Syria altogether. This has led to further tragedies, with displaced populations vulnerable to exploitation and death in their search for refuge, even as militants in Syria plot attacks on foreign soil from within Syrian territory.

The war has also witnessed untold depravity and systematic disrespect for the most basic rules of international humanitarian law, ranging from the promotion of enslavement on an industrial scale, to indiscriminate attacks on medical facilities. An Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic (CoI) established by the United Nations Human Rights Council in 2011 has documented these atrocities in harrowing detail. Another UN special inquiry established by the UN Security Council five years later has identified ‘sufficient information’ of use of chemical weapons to amount to war crimes or crimes against humanity.

Yet the prospects of accountability for these crimes have seemed poor. In the past, the UN Security Council has used its enforcement powers under Chapter VII of the UN Charter to create international war crimes tribunals – as it did for Yugoslavia and Rwanda – or to refer situations to the permanent International Criminal Court – as it has for Darfur. But efforts to do something similar for Syria have failed miserably, running directly into Russian and Chinese vetoes. The most recent such failures to encourage accountability came in March and April 2017. And while there have been isolated national prosecutions, for example in Germany and Spain, these have been understandably rare, given the complexity of the investigation and prosecution of such crimes.

Enter the General Assembly

It took many by surprise, therefore, when the UN General Assembly recently decided to get involved. On 21 December 2016, after a brief but animated debate, the General Assembly adopted Resolution 71/248 establishing an ‘International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism to Assist in the Investigation and Prosecution of Those Responsible for the Most Serious Crimes under International Law Committed in the Syrian Arab Republic since March 2011’, commonly known as the ‘IIIM’.

The IIIM, which will be based in Geneva, is mandated to

collect, consolidate, preserve and analyse evidence of violations of international humanitarian law and human rights violations and abuses; and

prepare files in order to facilitate and expedite fair and independent criminal proceedings, in accordance with international law standards, in national, regional or international courts or tribunals that have or may in the future have jurisdiction over these crimes, in accordance with international law.

The Mechanism prepares material for use by other actors in criminal proceedings. It is not itself an actor in those criminal proceedings. As a report subsequently issued by the UN Secretary-General makes clear, it ‘provides assistance’, developing criminal files to facilitate and expedite future criminal proceedings — wherever they may take place. The IIIM will serve as a centre for international criminal and judicial cooperation.

Was it legal?

The Resolution creating the IIIM passed with 105 affirmative votes, 52 abstentions and 15 negative votes. Those countries voting against the Resolution were, however, outspoken in their opposition. Several delegations, notably those of the Syrian Arab Republic itself, and the Russian Federation, questioned the legality of the move.

Many of the complaints were neatly summarized in a note verbale – a diplomatic letter – that the Russian Permanent Representative later sent to the General Assembly through the UN Secretary-General. First, they argued, the move broke the ban in Article 2(7) of the UN Charter on non-interference in domestic affairs. Second, it violated Article 12 of the Charter, which limits the power of the General Assembly to deal with matters already being considered by the Security Council. And third, the dissenters argued, the General Assembly did not have power to create a body with prosecutorial powers.

The IIIM is neither an international prosecutorial body, nor a court, but, as the Secretary-General’s Report puts it, a ‘quasi-prosecutorial body’, intended to serve as a specialized legal assistant to help states and other bodies that already enjoy the prosecutorial power or jurisdiction necessary to handle such crimes. The IIIM does not interfere in Syria’s internal affairs, because it is available to any actor to that already enjoys such jurisdiction – including the universal jurisdiction available to prosecute war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide.

Nor does the Security Council’s consideration of the broad issues around the war in Syria preclude the General Assembly from making recommendations on specific issues, such as accountability. In fact, there is more than fifty years of General Assembly precedent – and two recent cases in the International Court of Justice – that support this approach.

That precedent harks back at least to the early 1960s, when the UN Legal Adviser made clear that Article 12 does not prevent the General Assembly addressing a matter unless the Security Council is also addressing it ‘at that moment’. As ICJ judge Bruno Simma and colleagues have conclude in their authoritative Commentary on the UN Charter, subsequent practice in the General Assembly suggests that Article 12(1) permits action by the General Assembly where such action neither directly contradicts the position of the Security Council nor has been expressly rejected by it. That view seems to find support in two recent cases in the International Court of Justice, dealing with General Assembly requests for advisory opinions on the Israeli wall and on the declaration of independence of Kosovo.

Nor is this the first time that the General Assembly has supported international mechanisms providing legal assistance for the prosecution of serious, international and transnational crimes. Other examples of such support – including the use of UN funds – include the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL), the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), and the Independent Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG). And there are also parallels between the legal assistance to prosecution of international crimes that will be provided by the IIIM and the legal aid provided to the prosecution of transnational crimes by the UN Trust Fund for Victims of Trafficking in Persons, another General Assembly-backed body.

Some of those criticizing the creation of the IIIM have also argued that it verges on a judicial body, and that the General Assembly cannot create judicial bodies. This is not correct: the IIIM supports other judicial bodies, it does not exercise judicial powers itself. Yet these critics overlook another important precedent; the General Assembly has already, over 60 years ago, created a judicial tribunal – a move that was reviewed and approved by the UN system’s highest judicial body, the International Court of Justice.

Justice for Syria – and others?

So, will the IIIM provide justice for Syria? It is probably too soon to say. It faces considerable legal, practical and political hurdles, including its reliance (at this point) on voluntary funding. Unlike some past wars, however, there are extensive archives of official records, documentary and film evidence, and survivor testimonies (see for example here and here) that have been carefully pieced together in anticipation of future investigations and trials for perpetrators of atrocities during the war in Syria. These private initiatives face their own constraints, but may prove a boon to official investigators in the months and years ahead.

Perhaps almost as important, however, in the General Assembly’s intervention, is the new avenue it points to for international accountability. The IIIM relies not on accountability imposed by the UN Security Council, but through a more cooperative approach, supported by the General Assembly. In this approach, states use the framework of international cooperation offered by the UN to more effectively exercise their own, already existing jurisdiction. If the IIIM does succeed, it may come to be seen as providing a powerful example for victims of war elsewhere about how they, too, can achieve justice. Given the likelihood of continuing Great Power rivalry in the UN Security Council in the years ahead and the consequently diminished prospects for the Council to play a central role in international criminal justice, the General Assembly’s creation of the IIIM may in time be revealed as an important new departure in the continuing story of efforts to ensure accountability and uphold respect for the rule of law.

Featured image credit: UN Photo by Evan Schneider. General Assembly Adopts Resolution Establishing International Mechanism Concerning Syria. Published under fair use via United Nations .

The post Will there be justice for Syria? appeared first on OUPblog.

Slaves to the rhythm

I met up with Russell Foster in 1996 when I was writing a book on the social impact of the 24 hour society. I wanted to know what effect working nights had on human biology and health.

At the time Russell was Reader at Imperial College. Since then he has become professor of circadian neuroscience at Oxford University; a Fellow of the Royal Society; and he has a shelf full of medals from scientific societies around the world. We have written three books together and done our best to popularise the fascinating science of circadian rhythms and their impact on human health and behaviour.

Put simply, while we like to think that we eat when we are hungry, sleep when we are tired, and drink when we are thirsty, it is only a thin veneer of civilisation that gives us the pretence of choice. Left to our natural devices and bereft of our smartphones and alarm clocks, we would tend to eat, sleep, and drink, along with many more biological functions, not when we decide to but when the biological clock inside us tells us to. It is not only our physical behaviours that are dictated by this tyrannical time lord. Our moods and emotions also swing in time to a daily rhythm.

Most of what happens in our bodies, our physiology and biochemistry, is rhythmic, showing strong day–night differences. Heart beat and blood pressure, liver function, the generation of new cells, body temperature, and the production of many hormones such as cortisol and melatonin all show daily changes.

Biological clocks and rhythms can be found everywhere, from bacteria through to fungi, plants, insects, fishes, reptiles, birds, and us. The reason for this ubiquity is clear: all life evolved and lives on a planet that goes around the sun once a day, and so is exposed to large periods of day and night, light and dark. A trillion dawns and dusks since life began have imprinted a daily rhythm on all living creatures.

The big difference between us and other living things is that to some extent we can cognitively override these ancient hard-wired rhythms. Instead of sleeping as our bodies dictate, we drink another cup of coffee, turn up the radio, roll down the car window and kid ourselves that we can beat a few billion years of evolution. But we pay a price in both our physical and mental well-being.

We beaver away in our offices, shops, and factories, but even a cloudy day outside is some forty times brighter than the artificial light in which we live and work. On a sunny summer day it may be 400 times brighter. Daylight helps us stay healthy because it is the signal that keeps our daily body rhythms ticking over in time with the outside world, in the same way as a watch receives a radio signal that resets it every day to a super-accurate atomic clock.

The big difference between us and other living things is that to some extent we can cognitively override these ancient hard-wired rhythms.

Trouble starts when this alignment breaks down, which may be the problem with Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD). In Britain about 2-3% of adults suffer from it while a further 10% of have a mild depression known as the winter blues. SAD is perhaps the most common mood disturbance in women of childbearing age in Britain, unremittingly experienced year after year during the six months between the autumnal and vernal equinoxes.

Misalignment of the internal clock may well play a role in a startling list of illnesses including; Bipolar depression, Premenstrual syndrome, Attention deficit disorder (ADDH), Schizophrenia, Chronic fatigue syndrome, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s.

The relationship between circadian rhythms and many illnesses, including diabetes; heart disease; strokes; cancer; sleep disorders, is slowly being unravelled. We are some way from new drugs being available, but circadian rhythm research is now in a translational stage, whereby enough is known to suggest therapeutic routes.

A critical area where time of day matters to the individual is the optimum time to take medication, a branch of medicine that has been termed ‘chronotherapy.’ For instance, by varying the timing of medication to the individual, higher doses of anti-cancer drugs can be administered.

We are on the verge of very different medical care for cancer patients, where personalized treatments will be tailored to the most effective time of the day based upon the circadian chronotype of the patient and the timing of cell division within the tumour.

It all makes for an exciting time in circadian rhythm research.

Featured image credit: the eleventh hour disaster by Alexas_Foto. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Slaves to the rhythm appeared first on OUPblog.

May 4, 2017

Johnny had Parkinson’s…and music helped him walk

I was 20 years old when I had my first encounter with someone who has Parkinson’s Disease (PD). “Johnny” was a retired dentist, pianist, and former big band leader. I was an undergraduate student, music therapy major, and his home health aide. Johnny did not present with the most recognizable symptom of PD, the resting tremor—he would raise his arm, holding it parallel to the floor, and as it floated say, “My doctor says I have Parkinson’s Disease, but I’m not sure. See? No tremor!”—but he did have the bradykinesia (slow movement) and muscle rigidity. It was difficult for Johnny to get around his house, be independent with his daily activities like eating and dressing, and he sorely missed playing the beautiful grand piano resting in the middle of the living room.

Johnny is responsible for illustrating to me the link between the human auditory and motor systems. As mentioned, it was difficult for Johnny to get around his house. He lived in a long ranch, with his bedroom at one end of the house, and a dayroom at the other. Every morning, once ready for the day, Johnny and his walker would begin the trek down the length of his house, starting from the bedroom, walking on carpet, then shifting to the wood foyer, then back to carpet, before reaching the dayroom at the far end. And every day it would take Johnny time to begin (initiate) his walk, then he would falter (freeze) every time the flooring changed, then stall when needing to turn and enter the dayroom. The whole process would begin again at night, as Johnny worked his way from the dayroom back to his bedroom at the other end of the house.

One day we stumbled upon something that would end up helping Johnny on this twice daily haul. Given our shared history as musicians, it’ll come as no surprise that Johnny and I often talked about music. As Johnny was prepping to take the first step, we joked about singing a march so he could march his way down the hall. It was Johnny’s idea to use Sousa’s “Stars and Stripes Forever”, a march he liked. As I sang through the musical introduction, Johnny sang along and started marching in place. On the downbeat of measure five, when the first theme begins, Johnny moved his steps forward, and began marching (and singing) his way to the dayroom. No freezing of his gait as the flooring changed, no difficulties with initiation, and a smoother transition turning into the dayroom at the end of the hall. It was an instantaneous difference in the speed, length, and smoothness of Johnny’s gait.

An elderly couple walks on the street, Brasov, Romania. June 2007. Photo by Adam Jones adamjones.freeservers.com. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

An elderly couple walks on the street, Brasov, Romania. June 2007. Photo by Adam Jones adamjones.freeservers.com. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.What Johnny and my 20-year-old self stumbled upon was nothing new. Marching band members, military leaders, and dancers can all speak to the ability for the human motor system to entrain, or synchronize, to a steady rhythmic pulse. Furthermore, this connection has clinical applications. For example, in 2013, Lindaman and Abiru published a review of literature exploring the effect of Rhythmic Auditory Stimulation (RAS: a specific music-based intervention designed to improve gait through the application of a steady rhythmic beat) on gait patterns in individuals with PD. In general, they reported that RAS resulted in improvements in gait velocity, cadence, stride length, and balance, and decreased freezing during turns.

Furthermore, suggestions were made regarding how best to use music, such as utilizing a slower tempo for those who present with gait freeze, but a faster tempo for those who do not.

Gait is not the only area in which music-based interventions might make a difference. Many individuals with PD present with hypokinetic dysarthria, a term which describes speech and voice abnormalities associated with PD, such as reduced loudness, fast speech rate (which leads to poor intelligibility), and monotone voice (i.e., decreased vocal range). Given these connections, some researchers have explored the impact of a group singing intervention on these parameters. Overall, these singing-based interventions resulted in improvements in speech intelligibility and articulatory control, and well as in vocal intensity and vocal range.

The third area of study concerns the influence of music-based interventions on mood and quality of life. Though these often seem of secondary interest, researchers have noted connections between poor communication skills or living with a degenerative disease with depression and quality of life. Overall, research indicates that variables of depression and quality of life seem to improve following music-based interventions such as RAS, group singing, and general group music therapy.

In closing, we’ve touched on several evidence-based ways in which music interventions can be used to improve the physical, communication, and emotional skills of individuals living with PD. As I sit here and remember Johnny and our Sousa-singing walks down the hall, I’m struck by the thought that these experiences we shared went beyond helping Johnny walk more quickly and easily down the hall—they were also done while singing (during walking, no less!) and with smiles on our faces.

So perhaps there were other musically-driven benefits for Johnny of which my 20-year-old self was unaware.

Featured Image Credit: piano, music by Lukas Budimaier. CC0 Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Johnny had Parkinson’s…and music helped him walk appeared first on OUPblog.

Heartthrobs and happy endings

Popular romance is often written to a formula. Our heroine falls for the attractions of the hero. Stuff gets in the way. They get through this and marry. We assume that they are happy thereafter. Most of the books published by Mills and Boon or Harlequin have some variation on this kind of narrative, centring on heartthrobs and happy endings.

More ‘literary’ classics tend to present more complexity, but this isn’t always the case. Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice is a perfect example of the romance plot, and Fitzwilliam Darcy has constituted the perfect archetype of a romantic hero in many women’s eyes since the novel was first published in 1813. Darcy’s attraction has proved so enduring to generations of women that, two centuries later, when scientists working on pheromones in mice discovered a protein in the urine of the male mouse that was irresistible to females, they named it ‘Darcin.’

How did Austen come to imagine him? Darcy is a man of substance, master of Pemberley, a large estate in Derbyshire. It is precisely at the moment when Lizzy Bennet drives through the gates of Pemberley that she begins to realize that she fancies him. She’d previously thought him pompous and rude. It’s hard not to think of this change of heart as a touch mercenary, but we must remember that the Bennet’s were financially embarrassed, and that for women, marriage to someone with money and means was a key strategy for survival. A century or so later, prolific writer of romance Barbara Cartland referred to women who made ‘good’ marriages as having ‘married park gates.’

Austen was an avid reader, and in her portrayal of Darcy she drew upon her knowledge of works by Lord Byron and Samuel Richardson. Darcy incorporates many of the traits we associate with the Byronic hero: arrogance, hauteur, and a sardonic eye. The history of the novel is riven through with sexual politics, and male and female writers often had very different ideas about what was desirable in a man. In Pamela (1740), and Clarissa (1748), Richardson had given his contemporaries two examples of ‘heroes’ who were highly eligible in terms of status and substance but not at all respectable in their conduct towards women. Richardson was bothered when his female readers showed a soft spot for the charms of rakish seducer Lovelace, and he was irked by the success of his rival, Henry Fielding’s loveable rogue figure Tom Jones. So he set out to imagine a gentlemanly hero whose conduct would be above reproach, and whom women could safely desire. The result was the seven volume History of Sir Charles Grandison (1753).

Image at the beginning of Chapter 32. Darcy and Elizabeth at Charlotte (nee Lucas) Collins’ house. Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice. London: George Allen, 1894. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image at the beginning of Chapter 32. Darcy and Elizabeth at Charlotte (nee Lucas) Collins’ house. Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice. London: George Allen, 1894. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.References to this work recur regularly in women’s writing through the next century and more, although now it is rarely read. But we know that Jane Austen perused it carefully, even though she parodied it and made fun of its hero in her own dramatic adaptation, Sir Charles Grandison. The trouble was that Grandison emerged as a prig, too good to be true.

We don’t lack literary heartthrob types who bring heartache rather than happy endings. Think of Heathcliff – an exemplar of dark passion, but full of brutality towards women and dogs. Emily Brontë makes Heathcliff himself sneer at Isabella as deluded for making him into a ‘hero of romance’, and for feeling soft-hearted about him. Or think of Charlotte Brontë’s Mr Rochester. A potential bigamist, who becomes eligible only when he’s nearly burned to death along with his mad wife. There’s a kind of happy ending, but Rochester’s injuries are serious, and Jane has to take on the heavy duties of carer, even though this gives her some kind of power over him. And there are many heartthrobs in literature who slip through the heroine’s hands: George Eliot’s Gwendolen loses Daniel Deronda to Mirah; Rhett Butler tires of Scarlett O’Hara just when she realises she fancies him badly, Amber St Clare in Kathleen Winsor’s 1944 blockbuster Forever Amber never does secure her hold on the snobbish, opportunistic, but to her, devastatingly sexy Bruce Carlton.

What we have in Pride and Prejudice is a finely wrought and elegant essay in wish fulfilment. And this at a time when women’s options were severely constrained, and we are given to understand that Lizzy has very few resources aside from her intelligence and her quick wit. Darcy is consummately eligible. He exudes dark hints of sexual energy, even before he was unforgettably played by Colin Firth, emerging from a lake in a wet shirt in Andrew Davies’ adaptation of the novel for television in 1995. But however rich and sexy, he’s still an arrant snob, with the capacity to wound those he considers his inferiors. With nothing more than alchemy of spirit, intelligence – and her fine eyes – Lizzy manages to bring about a personality change in Darcy and to bring him to his knees. We – and women readers especially – suspend our disbelief because we want to imagine that this could happen, that patriarchy can be made to work for women, that life can be a fairy tale.

Featured image credit: The Orangery, a Grade II* listed building, part of the Lyme Park estate in Cheshire by Julie Anne Workman. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Heartthrobs and happy endings appeared first on OUPblog.

The unprecedented difficulty of B(e)

A dictionary is in indeed a collection of stories. Each word entry has a unique tale to tell. Whichever word we choose, we find ourselves engaging with the story of the language as a whole. And if we choose be, we encounter a special insight into English, and into the society and thought that has shaped it over the past 1,500 years.

My title for this post, the unprecedented difficulty of B(e) is an adaptation of Peter Gilliver’s remark, in The Making of the Oxford English Dictionary (p. 197), when he describes James Murray’s ‘pain and vexation’ at criticism of his rate of progress at the beginning of letter B. Be is not the only item mentioned in Murray’s listing of the complicated words in this section of the alphabet, but it must surely have been the main lexical mountain he had to climb at that point.

Or at any point? With its various historical antecedents (seen in am/is, are/art, be/being/been, and was/were/wert), ‘Be’ has more variant forms (1,812 is the OED lexicographers’ count) than any other English verb. Then there are the complications arising from three persons, variations in stress, contracted forms, standard and nonstandard variants, and its double function as full verb and auxiliary verb. There’s nothing else that measures up to it.

But it’s the semantic complexity of this word that has always fascinated me. The day I decided to tell its story was the day I was passing a mum shovelling her little boy into the back of a car and saying at the same time: ‘Have you been?’ One ‘goes’ to the toilet. More elegantly one might ‘visit’ it. But, having gone, we do not usually say I’ve gone or ask children if they have gone. We can say I went an hour ago, but not I’ve gone an hour ago. Been does the job instead. I’ve been. Been as a past form of go. Unusual.

‘Were there any more like that?’ I asked myself. And of course there were. The OED entry on be is full of fascinating semantic nuances, but the fascination can remain unnoticed within all the detail. And in such a long and complex entry, it’s not only easy to lose sight of the wood, it’s difficult to see all the trees. Can one tell the story of an entire OED entry like this in an accessible and interesting way? I decided that I would try.

So, amongst my research and alongside the ‘lavatorial be‘, I discovered some two dozen different semantic usages, such as ‘nominal be‘ (wannabes and has-beens), ‘identifying be‘ (business is business), ‘eventive be’ (been and done it), and ‘sexual be’ (I’ve been with him/her). All human life is bound up in this little verb, it seems.

What I wasn’t expecting was to see the extent to which an exposition of its various senses would lead me into other areas of the language. In fact most of English linguistic life is represented, including phonology (contemporary and historical), graphology, regional and social dialectology, grammar, pragmatics, stylistics, sociolinguistics… and a remarkable array of illustrative contexts, going well beyond the literary sources normally used in lexicographical citations, such as advertising, newspaper headlines, pop music, music halls, pantomimes, road signs, and text messaging. Understanding the story of be really does give one a ‘verb’s-eye’ view of the English language.

There is an old story of a reader who brings a dictionary back to a lending library and comments to the librarian: ‘Quite enjoyable, but the stories are rather short, aren’t they’. Not in this case.

Featured image credit: Bee, by Victoria Kurtovich. CC0 Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post The unprecedented difficulty of B(e) appeared first on OUPblog.

May 3, 2017

Two posts on “sin”: a sequel

This sequel has been inspired by a letter from a colleague and by a comment.

Sin all over the world

The colleague who wrote me a letter is a specialist in Turkic and a proponent of Nostratic linguistics. He mentioned the Turkic root syn-, which, according to him, can mean “to test, prove; compete; prophesy; observe; body, image, outward appearance,” and wondered whether, within the framework of Nostratic linguistics, this root can be compared with the root of Engl. sin. At least some of the senses listed above (“body, image, outward appearance”) remind one of “be,” while the others bear some resemblance to “guilt,” discussed in some detail in my posts. For obvious reasons, I can have no opinion about a word in the language family I have never studied. I could only consult the books in my office (Allan S. Bomhard and John C. Kern, The Nostratic Macrofamily…, 1994, and V. M. Illich-Svitych’s major work (Opyt…, 1971), which has an index, published in 1974. Neither sin/syn nor the concepts covered by those roots turn up there. However, I thought that saying something about the nature of the question, that is, about Nostratic linguistics, may be of interest to our readers. I don’t have to go into detail, because Wikipedia offers a highly professional article on Nostratic, and will only touch on the main principle.

It has always been known that some languages are related. The anthologized examples are Swedish and Norwegian, German and Dutch, Italian and Spanish, Russian and Ukrainian. The existence of more distant relationships was also clear to linguists long ago. In the eighteenth century, the term Scythian languages was coined. It did not mean what it means today, for at that time it partly overlapped with what is now designated as Indo-European. The school-text division of the Eurasian languages into families and of families into groups goes back to the nineteenth century. Some families are huge; the largest of them is Indo-European, while others, such as Semitic, Paleo-Siberian, and Finno-Ugric, are smaller. To establish the relationship, linguists compare grammatical forms and some basic words, especially kin terms and the first numerals.

The beginning is hard to reconstruct. For example, how did the Indo-European family come about? Was it once a solid language that, as time went on, split into dialects? Does a picture of a tree with branches, twigs, and leaves (a putative model of Proto-Indo-European) give justice to the initial state? Or have there always been dialects that interacted like overlapping waves? Who spoke the most ancient form of Indo-European and where? How did the early forms of it spread over such an enormous territory? Those questions have never been answered to everybody’s satisfaction. Since words tend to change beyond recognition, the especially important forms for reconstruction are the most ancient ones. But in the remote past, there was no literacy. Therefore, we depend on relatively late evidence. Besides, figuratively speaking, some languages were recorded only “the day before yesterday.” If we disregard the runes, the earliest written text in Germanic goes back to the fourth century AD (Gothic). English was recorded much later. In the past, the ancestors of the speakers of Indo-European were nomads, which means that language contact was the order of the day. That is why so-called language unions were formed, and we often do not know whether a certain word is related to another one or is a borrowing of it.

The less we know, the easier it is to indulge in breathtakingly bold speculation. Scholars often have clear notions of what happened five thousand years ago but are at a loss when they have to explain some process in Middle or early Modern English. The lay public and journalists usually prefer daring hypotheses and sensational theories. Yet this does not mean that such theories are wrong by definition! Thus, quite some time ago, attempts were made to show that the Indo-European and the Semitic languages are related. Some similarities between them are beyond doubt. The question is whether those are due to common origin or borrowing (contact). Still later, some scholars went farther and posited the relationship of very many languages of Eurasia and Africa. This is how the Nostratic hypothesis was born.

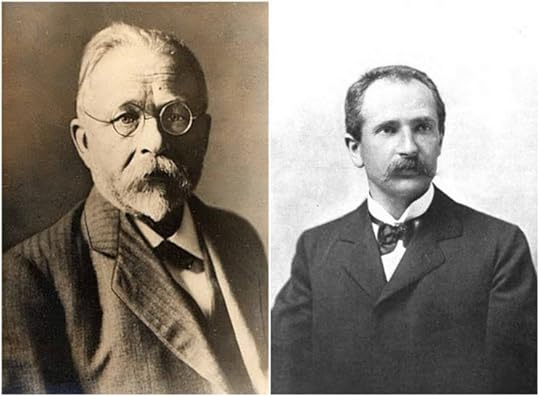

The names of the founders are Holger Pedersen (a Dane) and Alfredo Trombetti (an Italian). Trombetti’s works are rather hard to get in the United States, but Holger Pedersen’s publications are easily available. The Nostratic idea owes its second lease on/of life to a group of Moscow linguists. Its founder was Vladislav Illich-Svitich, whose early death in a car accident (he was killed by a drunken driver) was an irreparable loss to historical linguistics. Fortunately, his school in Moscow, Israel, and the United States is very much alive. We should agree that, if even the genesis of Indo-European is highly problematic, the history of an allegedly united family that encompasses a much greater number of languages from North Africa to Korea and Japan is much harder to present in a convincing way. For comparison, I can recommend those interested in this subject to consult the entry “Altaic languages” in Wikipedia. Part of it is devoted to the furious controversy over the existence of the so-called Altaic family. In the late nineteen-sixties and early seventies, I witnessed the acrimonious debate on this question and do not cherish those memories. Finally, look up Joseph Greenberg. His work is highly relevant to our subject.

Holger Pedersen and Alfredo Trombetti

Holger Pedersen and Alfredo TrombettiSo did the Nostratic family exist? One finds ardent advocates, contemptuous opponents, and quite a few scholars who sit on the fence. Caution is either a virtue or a vice, depending on the observer’s point of view. Hence the answer to my correspondent can be neither “yes” nor “no.” Those who reject the Nostratic hypothesis will find the very question useless. But if some of the leading proponents of the Nostratic idea read this blog, it will be interesting to know their opinion. Let me repeat: it is about Turkic syn and its problematic Indo-European analog.

Sin in Slavic and Latvian

The Russian for “sin” is grekh. Its cognates in Slavic sound similar, but its posited cognates in the rest of Indo-European are dubious, to say the least. The multivolume etymological dictionary of Slavic (vol. 7, 1980, pp. 114-116) prefers to compare grekh with Latvian grèzs “crooked” (not a new idea). If this comparison is allowed to stand, the traditional reference of the Germanic word for “lie, falsehood” (Engl. lie, etc.) to Latvian lùgt gains some credence, provided that word ever meant “bending.” Lies and sins are the opposite of straight words and actions. The semantic base for the words designating “sin” varies from language to language: compare Latin peccatum (possibly from “false step,” but this may be a case of folk etymology), Sanskrit pātaka (from “a fall”), Gothic frawaurhts, literally “perverse act,” and so forth. The modern concept of sin is a product of Christianity.

By contrast, Russian sud “judgment; court” does not belong to our story, because sud consists of the prefix s- (the stub of ancient som-, Russian su-) and the root meaning “to do,” reconstructed as dhē-. This division of the short, monosyllabic word sud belongs to the remote past and is made clear only through etymological analysis. It appears that the idea of Latvian sods “punishment” as a borrowing from Slavic need not be called into question.

Image credits: (1) “Holger Pedersen 1867-1953” by unknown, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Portrait of Alfredo Trombetti by unknown, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) “Portrait of Alexander Wedderburn, 1st Earl of Rosslyn (1733-1805)” by Joshua Reynolds, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Two posts on “sin”: a sequel appeared first on OUPblog.

Brando, Obama, and The Brando

Just days before Marlon Brando’s 93rd birthday on 3 April, Barack Obama announced that he will write his presidential memoirs at an exotic South Pacific hideaway once owned by Brando. Thirty miles north of Tahiti and accessible only by boat or small aircraft, the island of Tetiaroa was transformed into a high-end resort after Brando died in 2004. In fact, Obama will be staying at what is now called The Brando.

The actor discovered the island when he was scouting locations for his 1962 film, Mutiny on the Bounty. Feeling that he was about as close to paradise as possible, he bought the island for $270,000 in 1966. He would spend most of the rest of his life there, emerging reluctantly to appear in films, some of them less memorable than others.

In the 1950s Brando transformed the art of film acting. By the 1960s, however, he had begun to hold his talent in disdain. He had even less respect for people deceived by Hollywood mythology. When he received an Oscar nomination for his performance in The Godfather (1972), he boycotted the festivities. After he was declared the winner, an actress named Marie Cruz stepped up to the podium. Appearing in Native American garb and identifying herself as “Sacheen Littlefeather,” she read Brando’s denunciations of the industry’s treatment of Native Americans.

Barack Obama, with a multi-million dollar advance from Crown Publishing, will be enjoying the peace, quiet, and luxury that Tetiaroa abundantly offers. In many ways, Obama’s move to The Brando makes sense, and not just because Brando had worked hard to make the island environmentally-friendly and self-sustainable. The President surely knows Marlon Brando’s history as a civil rights activist, one that preceded Obama’s own activism by a generation. Brando marched with the movement’s leaders and did not hesitate to embrace the cause, even if he offended those who may have shared his values, as when he sent Ms. Cruz to lecture a crowd that included many Hollywood liberals.

Earlier, in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., Brando actively supported the Poor People’s March on Washington sponsored by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. In his memoir White Dog (1970), diplomat and novelist Romain Gary describes how Brando sought to raise money at a meeting of celebrities prior to the march. When Brando asked for volunteers for a steering committee, thirty hands went up in a crowd of about three hundred. According to Gary, Brando than said, “Those who didn’t raise their hands, get the hell out of here!”

Although he was raised by his white mother and her parents, Obama was drawn to African American culture and found his voice listening to black preachers and activists. Born in Nebraska and raised in white America, Brando was also fascinated by African American culture. In the late 1940s he joined Katherine Dunham’s School of Dance, where sixty-five percent of the students were black. He also learned to play congas and bongos with a Haitian drum master. I am convinced that his early filmic impressions of inarticulate working-class men was inspired by black artists for whom inarticulacy was a survival strategy. Nathaniel Mackey has described “the telling inarticulacy” of blues artists who speak of their oppression not with words but with cries, groans, and shrugs.

Similarly, Brando learned a great deal about improvisation from black jazz artists. Yes, we know that improv was essential to the Method acting of which he is the inevitable exemplar, but Brando was much more like a jazz musician with his surprising and even playful improvisations. In Streetcar Named Desire (1951) Brando is Stanley Kowalski, a confused, often-violent man child like many of the characters he played in the 1950s. Early in the film, he explores the items in a trunk that belongs to his wife’s sister, Blanche. Not at all happy with the amount of family money that Blanche seems to have spent on her clothes, he manhandles a white stole. As tiny white feathers drift away, and as Stanley is in the midst of an argument with his wife, he picks feathers out of the air with the purposeful purposelessness of a child. Brando found a way to react in character outside of any scripted directions. Like jazz improvisers working out their ideas “in the moment,” he was fully in control of his craft as an actor.

Press publicity photo of Marlon Brando and Vivien Leigh in the play A Streetcar Named Desire, 1951 Source ebay, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Press publicity photo of Marlon Brando and Vivien Leigh in the play A Streetcar Named Desire, 1951 Source ebay, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.I should also point out that in The Wild One (1953) Brando plays a member of the “Black Rebels Motorcycle Club” and that he is almost lynched by a group of white townspeople. After several memorable performances in which he channeled his fantasies of blackness, Brando made a career decision and appeared as Napoleon in Désirée (1954). Although many praised his performance, Brando affected a British accent and deployed acting techniques that had little to do with the Method and everything to do with his personal magnetism. There would be a handful of extraordinary performances during the half-century of work that followed, but by this time Brando cared little about the art of the actor and was simply phoning it in. He was much more interested in turning Tetiaroa into his own personal utopia.

Between writing sessions, Barack Obama will be strolling the beaches and gardens where Marlon Brando had hoped to live in paradise. I wonder if he’ll have anything to say about Brando in his much-awaited memoir.

Featured Image credit: Onetahi, Tetiaroa, in French Polynesia, February 2003. Tom Dhaene at nl.wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Brando, Obama, and The Brando appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers