Oxford University Press's Blog, page 369

May 8, 2017

Storm Stella and New York’s double taxation of nonresidents

The physical aftermath of Storm Stella is now over. The tax aftermath of Storm Stella, however, has just begun.

How can a winter storm cause taxes? Because New York State, under its so-called “convenience of the employer” doctrine, subjects nonresidents to state income taxation on the days such nonresidents work at their out-of-state homes for their New York employers. Nonresident commuters, who worked from their out-of-state homes during Storm Stella, consequently owe income taxes to New York even though, on that snowy day, they did not set foot in New York.

For many commuters, New York’s extraterritorial taxation of nonresidents results in double state income taxation. Connecticut, for example, correctly imposes its income tax on its residents for the days these residents work at home in the Nutmeg State since, on a day when a Connecticut resident works at home, Connecticut and its municipalities provide public amenities such as fire and police services to these Connecticut residents working at home.

When a Connecticut resident works at home for a New York employer, neither state provides a credit for the taxes paid to the other. Consequently, the Connecticut resident who wisely worked at home during Storm Stella will pay income taxes to both Connecticut and New York – even though New York provided no public services to them on that work-at-home day.

As for other states, New York’s “convenience of the employer” doctrine unfairly causes the state of residence to subsidize New York. For example, a New Jersey commuter who worked at home during Storm Stella can take a credit against their New Jersey income taxes for the day she worked at home in the Garden State. By this credit, New Jersey’s treasury (and thus its taxpayers) effectively subsidize New York’s extraterritorial taxation of income earned across the border in the Garden State. New Jersey effectively surrenders income tax revenue on days when New Jersey, not New York, provides services to the New Jersey resident who works at her home.

For many commuters subject to New York’s double taxing “convenience of the employer” rule, the financial consequences of Stella lie in wait to appear on their 2017 state income tax returns.

Every independent legal commentator on New York’s “convenience of the employer” doctrine concludes that this doctrine violates the US Constitution, since, on the day a nonresident works at his out-of-state home, New York taxes income is earned outside its borders. When New York’s “convenience of the employer” doctrine was last tested in the courts, three judges of the Court of Appeals (New York’s highest court) agreed that New York’s extraterritorial taxation of income earned in other states is unconstitutional. Unfortunately, four of their colleagues ignored these compelling constitutional concerns under the Due Process and Commerce Clauses, and instead upheld New York’s taxation of nonresidents’ incomes earned at their out-of-state homes.

Governor Cuomo eloquently declares that he no longer wants New York to be the “tax capital of the United States.” The Governor’s commendable goal will remain beyond reach as long as New York unconstitutionally taxes nonresidents’ incomes on the days they work at their out-of-state homes.

At a minimum, Governor Cuomo should announce that New York will not assert income taxes against nonresident commuters who worked at home during the week of Storm Stella. More fundamentally, the Governor should instruct the New York Department of Revenue and Taxation to revoke the administrative regulation which promulgates the “convenience of the employer” rule and the extraterritorial taxation the rule causes.

Given the unlikelihood of Governor Cuomo pursuing either course, Congress should legislate, as it has in other similar instances to rationalize the system of interstate income taxation. In prior Congresses, senators and representatives concerned about New York’s extraterritorial taxation of nonresident telecommuters have introduced the Multi-State Worker Tax Fairness Act. If enacted into law, this legislation would forbid New York (or any other state) from taxing nonresidents on income earned working at their out-of-state homes.

In an age when telecommuting is a norm of the workplace, such federal legislation, if enacted into law, would sensibly forbid double state income taxation of the sort caused by New York’s overreaching beyond its borders. Storm Stella should now be a memory. Instead, for many commuters subject to New York’s double taxing “convenience of the employer” rule, the financial consequences of Stella lie in wait to appear on their 2017 state income tax returns.

Featured image credit: New York by Anthony Delanoix. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Storm Stella and New York’s double taxation of nonresidents appeared first on OUPblog.

How libraries served soldiers and civilians during WWI and WWII

Essentials for war: supplies, soldiers, strategy, and…libraries? For the United States Army during both World War I and World War II, libraries were not only requested and appreciated by soldiers, but also established as a priority during times of war. In the midst of battle and bloodshed, libraries continued to serve American soldiers and citizens in the several different factions of their lives.

“Their purposes reached far beyond housing a collection of books,” explained Cara Setsu Bertram, Visiting Archival Operations and Reference Specialist at the American Library Association Archives.

During World War I and World War II, camp libraries popped up everywhere at military bases in the United States and all over Europe, stretching as far east as Siberia. These camp libraries were originally established by the American Library Association (ALA), and at the end of World War I, ALA transferred control of them to the war department, which maintains them to this day. ALA worked with the YMCA, the Knights of Columbus, and the American Red Cross to provide library services to other organizations, such as hospitals and rehabilitation centers.

These libraries were nothing glamorous—usually a shed, shack, or a hut built of wood and other available materials. They were run by librarians who volunteered to travel overseas to care for the libraries. Responsibilities included circulating the collections, maintaining them, weeding out books, and acquiring new ones. More than 1,000 librarians volunteered during World War I, and that number only increased with World War II.

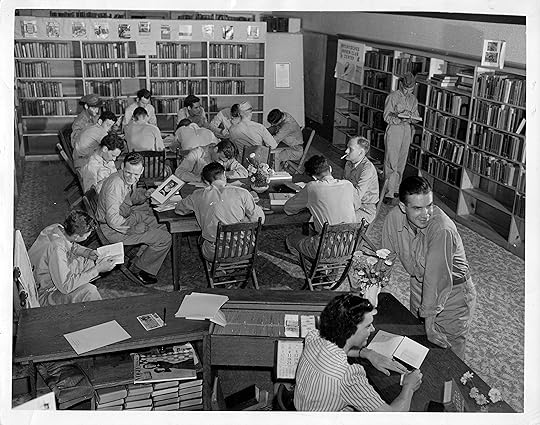

“Servicemen at a Louisiana Library, circa 1942” courtesy of the American Library Association Archives. Used with permission.

“Servicemen at a Louisiana Library, circa 1942” courtesy of the American Library Association Archives. Used with permission.For many soldiers, Bertram explained, libraries were a place to relax, read, boost their morale, and educate themselves. Many soldiers were thinking about which jobs they wanted when they returned home toward end of the war, so they read about skills for various lines of work. For a few, this was the first exposure these soldiers had to books of any kind, and many illiterate men gained the opportunity to learn to read.

“What’s really interesting is that soldiers were interested in non-fiction, technical books,” Bertram added. “You would think they’d want to read a fiction book, something to take their minds elsewhere, but they were really interested in non-fiction.”

Despite the overwhelming interest in non-fiction, there were a few fiction books that resurfaced as favorites amongst military personnel, such as A Tree Grows in Brooklyn and The Great Gatsby. “These books were almost pulled out of obscurity and brought into popularity during WWII,” Bertram notes. “They were already classics, but they regained popularity during this time thanks to the soldiers.”

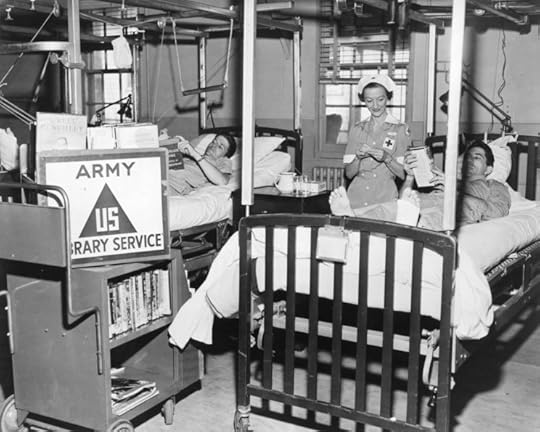

The practice of bibliotherapy gained traction during the two World Wars, as many soldiers used reading to treat PTSD, paranoia, insomnia, and other psychological disorders commonly suffered by veterans. Nurses read to injured and blinded soldiers to ease their suffering.

“US Army Hospital Ward Service, circa 1945” courtesy of the American Library Association Archives. Used with permission.

“US Army Hospital Ward Service, circa 1945” courtesy of the American Library Association Archives. Used with permission.Paranoia seeped into these libraries as well, in the form of censorship. Certain books were banned from the libraries in camps, several of them being pro-German sentiment books, pro-socialist books, and books about pacifism. The war department wanted them pulled from libraries or completely destroyed. For citizens in the United States, the military demanded that all books on explosives, invisible ink, and ciphers be removed from libraries, and that any patron who requested such materials have their name put on a list to submit to the FBI for questioning.

Even with the careful curation by high-ranking officials, ALA sent over 10 million books to the armed services camps during its Victory Book Campaign from 1942–1943. Reading materials were distributed to various military branches, such as the Army, Navy, American Red Cross, prisoners of war, and even the “war relocation centers,” a euphemism for the Japanese-American internment camps in the United States.

At the end of World War I, these camp libraries were taken over by the military, but one library in particular was created independently to serve the American ex-pats who remained in Europe after the war. ALA founded the American Library in Paris in 1920 to serve in part as a memorial for Alan Seeger, a young American poet, who was the son of Charles Seeger, a leader in the group of American ex-pats. The library was meant to be a haven for armed forces personnel serving their allies in World War I.

“One of the original missions of the library was to teach and show off the advances Americans had made in the field of library science,” said Charles Trueheart, current Director of the American Library in Paris. Library science was a very progressive subject, and the United States was far ahead of the French in that regard at the time. The library was a symbol of the United States becoming a true world power.

Photo of the American Library in Paris in 1926. Photo “10 rue de l’Elysée” from the American Library in Paris. Used with permission.

Photo of the American Library in Paris in 1926. Photo “10 rue de l’Elysée” from the American Library in Paris. Used with permission.“Americans moved to France in large numbers to build these big institutions that they didn’t build anywhere else in the world,” Trueheart admitted.

After the First World War came the second, and the purpose of the library morphed. “It was the only library in Paris or France that had books in English and could stay open because of Vichy connection,” said Trueheart. That connection is slightly controversial.

Throughout WWII, the library survived in large part due to Countess Clara Longworth de Chambrun. After the first director, Dorothy Reeder, was instructed to return home to the United States for her safety, Countess de Chambrun took over control of the library as the Nazis occupied France in 1940. Due to her son’s marriage to the daughter of the Vichy Prime Minister, Pierre Laval, the library was able to remain open throughout the war. The library continued to operate with occasional confrontations with the Nazis, and even though her family was tied to the enemy, she aided in the resistance. While the library remained open under the guise of being compliant with the Nazi cause, de Chambrun ran an underground book service to Jewish patrons.

The value of this library, and the other camp libraries, throughout both World Wars was immeasurable. The American Library of Paris was a lending library, where people came to read and borrow books, and it was the only library in Paris or France that had books in English and could stay open during World War II.

“There wasn’t anything like this and it was a treasure,” echoed Trueheart.

These libraries were safe havens for soldiers and civilians alike, and their existence during times of war is a true testament to the constant need for libraries.

Featured image credit: Photo of military personnel and a librarian in a camp library in France in 1919 from the American Library in Paris. Used with permission.

The post How libraries served soldiers and civilians during WWI and WWII appeared first on OUPblog.

The impact of intergenerational conflict at work

Recently, several colleagues and I noted that conflict in the workplace can emerge as a result of perceptions of differences related to what members of various generations care about, how they engage in work, and how they define self and others. We also noted several ways in which these conflicts might be resolved including achieving results, managing image in the workplace, and focusing on self in challenging interactions. But some readers may wonder as to the importance of positive intergenerational actions in the workplace. They may ask: why is it important to improve intergenerational conflict at work?

Intergenerational communication is often apparent in popular culture. In a recent article, I reviewed several movies that highlighted intergenerational mentorship. For example, Han Solo mentors a younger Rey in Star Wars: The Force Awakens. Similarly (and perhaps more realistically), Anne Hathway’s and Robert DeNiro’s characters engage in highly effective mutual intergenerational mentorship after overcoming challenging interactions upon initially meeting in the film, The Intern.

Yet, not all intergenerational interactions are positive. Nor are they occurring in fiction. In a recent survey, business leaders report a lack of preparation in preparing younger generations for future leadership roles, in part, because appropriate mentorship is not occurring. Furthermore, talent development initiatives in workplaces appear to be ineffective in preparing younger workers for future roles. This is especially problematic given that, as older generations leave the workplace, there will be a substantial knowledge, skill, and experience gap as younger generations inherent their roles and responsibilities. The major logical outcome is that organizations will not be able to perform as efficiently and effectively. Furthermore, they will not be able to maintain the same level of service that customers have come to expect.

“In a recent survey, business leaders report a lack of preparation in preparing younger generations for future leadership roles, in part, because appropriate mentorship is not occurring.”

In our research, though, we found that some older generation workers remove themselves from challenging interactions with younger colleagues – a privilege that younger employees may not possess as they are more likely to be junior-level workers that rely on more experienced colleagues for advice, assistance, and workplace assignments. Older workers that reported engaging in walking away from challenging interactions often did so because of negative perceptions that they had of younger workers, often in spite of never having proof of their less-than-positive impressions.

By walking away, multigenerational workforces will continue to experience a breakdown in communication, a lack of mentorship, and reduced opportunities for intergenerational knowledge transfer. So, what are some ways to improve intergenerational interactions so that organizations will not see decreased functionality as younger employees inherent more decision making and leadership roles? Below are three suggestions.

Forget stereotypes. It’s perhaps not surprising that many people hold onto their stereotypes when they engage in workplace interactions and generational-based stereotypes are no exceptions. Yet, when people use stereotypes to guide how they interact with others, they take out the individuality inherent in each person. In essence, they don’t learn what’s unique about the other person in order to have a truly positive interaction with them. By focusing on people as individuals, workplaces are able to become much more collaborative and organizations can leverage each person’s knowledge, skills, and abilities.

Provide realistic training. Intergenerational workplace interactions can be challenging if employees don’t understand solid techniques for interacting or the benefits of positive interactions. Furthermore, interactions may not occur at all if they view individuals of other generations to be completely unalike from themselves. Proper training, however, can solve many of these issues. Training can provide soft skills to improve communication and knowledge of benefits of positives interaction. Training can also help to breakdown stereotypes that may be inaccurate.

Engage in proper conflict management activities. As multiple generations work together, each with differing perceptions of others, conflict is likely to emerge. Organizations must, therefore, help to facilitate proper conflict management techniques. Organizations may also consider using other academically supported methods including Rothman’s ARIA conflict engagement model. This particular model is useful to engage identity-based conflict (in which conflict is caused by how an in-group defines self within the context of other out-groups). Because generational tensions can emerge on identity lines as we note in our research, this is a potentially useful approach.

So, have you ever experienced intergenerational conflict? What was helpful in improving your situation? I’m interested to hear your thoughts in the comments below.

Featured image credit: Nice But Not Special: The Intern Review by BagoGames. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The impact of intergenerational conflict at work appeared first on OUPblog.

Which Jane Austen mother are you?

Jane Austen novels are noted for their emphasis on female relationships. They are often portrayed as multi-dimensional–formative and yet not always so rosy. In celebration of Mother’s Day, and in honor of the 200th anniversary of Jane Austen’s death, we decided to create a quiz to help you determine which of our favorite Jane Austen mothers you are. Will you be the type to encourage romance? Can you offer advice to your children when they need it? Take the quiz to find out which matriarch you are.

Featured image: “Tulips…” by aanca. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Which Jane Austen mother are you? appeared first on OUPblog.

On criminal justice reform, keep fighting

In the late 1970s, many people studying and working inside criminal justice institutions in the US felt that they had awoken to a whole new world. Everything suddenly seemed different: rampant talk of “rehabilitation” had been replaced with politicians shouting about locking up “super predators.” Across the country, states’ prison systems swelled to capacity—and well beyond—as police, prosecutors, and judges enacted “tough on crime” policies. This was not the first time those paying attention to criminal justice felt the world had shifted suddenly and irrevocably under their feet—and not always in the direction of harsher punishment. Indeed, just a few decades earlier, in the wake of World War II, many reformers and those working inside newly dubbed “corrections” departments believed they could transform prisons, probation, and parole into therapeutic communities that provided individualized treatment. At the time, advocates of the punitive status quo worried that liberals were trying to “coddle” criminals and wreck havoc on the system.

Today, criminal justice advocates, bureaucrats, policy-makers, and scholars are anxious as the world rotates once again. What looked like a formidable new movement toward moderating the penal system has increasingly given way to law-and-order redux. Trump’s appointment of Jeff Sessions as Attorney General has emblemized this trend, with Sessions helming a series of Department of Justice reversals including halting federal consent decrees with local police departments and dismantling the nonpartisan National Commission on Forensic Science. The recent hiring of former prosecutor Steven H. Cook to “bring back” the war on drugs continued this trend. Among Cook’s worst ideas are a crackdown on marijuana and the end of Obama-era decisions to scale-back harsh sentences for low-level, non-violent drug offenses.

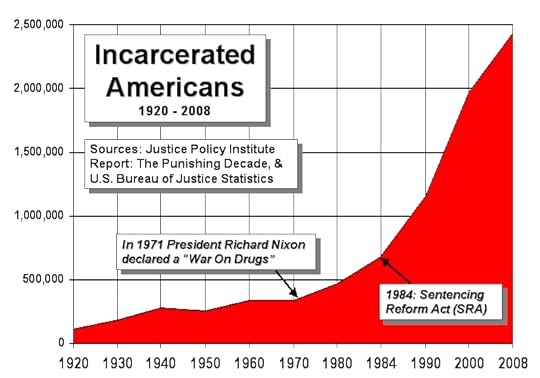

Timeline of total number of inmates in U.S. prisons and jails by November Coalition. CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Timeline of total number of inmates in U.S. prisons and jails by November Coalition. CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Pessimism in the face of these regressive (and, in some cases, deeply unpopular) decisions is understandable. In addition, this account of rapid and immediate change fits a narrative popular in the press and among academics: that U.S. criminal justice swings like a pendulum, moving rapidly and completely between harsh punishment (focused on retribution) and more lenient treatment (focused on redemption or reformation). In this view, Trump’s election represents a swing of the pendulum back to the punitive side of the ledger.

Despite the popularity of this metaphor, it obscures more than it reveals. The pendulum metaphor hides the long history behind such changes and over-states the degree of coherence in criminal justice practices at any given place and time. Punishment has always been both punitive and ameliorative, with shifts propelled by ongoing political contestation that shapes penal policies and practices on the ground—often in ways that go against declarations from the White House, Congress, and State Houses. Rather than a sudden “swing,” criminal justice change is the slow, often piecemeal result of this multi-faceted struggle. Thus, those seeking a more moderate criminal justice system should not give up hope Consider mass incarceration, which many scholars and policy-makers see as a critical swing of the pendulum. The prison boom of the late 20th century didn’t occur overnight: politicians, activists, and interest groups fought for harsher punishment and slowly built institutional and political capacity over decades. Even as treatment-oriented bureaucrats and policy-makers gained political dominance in the 1950s and ‘60s, those who favored tough punishment retained significant power inside prisons—including guards and administrators who thwarted the implementation of liberal reforms. At the same time, conservative lawmakers accrued power, steadily pushing for longer prison sentences and less judicial discretion. Eventually, this diverse coalition had paved a path for the “tough on crime” sentencing policies, prosecution practices, and policing patterns that fueled incarceration rates in the 1980s and ‘90s.

Prison by Babawawa. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Prison by Babawawa. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.Similarly, the ongoing fight against the punitive build-up has long been underway. Groups like the Sentencing Project and Families Against Mandatory Minimums have worked for decades to promote progressive sentencing reform, for example, while academics and legal advocacy groups have long challenged practices like the expansion of solitary confinement. Even in the 1980s and ‘90s, punitive decades of fiscal austerity and over-crowded prisons and jails, correctionalists continued to fight for rehabilitative programs inside prisons—winning key concessions. At the same time, scholars, policy analysts, and journalists documented extreme racial disproportionality in imprisonment, as well as the “collateral consequences” affecting prisoners’ families and communities. While such efforts rarely made the headlines in the late twentieth century, they eventually gained bi-partisan traction in the context of the Great Recession and historically low crime rates.

Today is no different. Trump’s administration will be able to make important changes (rolling back federal sentencing reform, increasing federal prosecutions for drug and immigration-related offenses, expanding federal private prisons, and the list goes on). But they can no more end criminal justice reform than a Democratic president could have “ended” mass incarceration from the White House. Policy-makers, police and corrections leaders, prosecutors, judges, advocacy groups, and everyday citizens will continue to fight (as they always have fought) for a more moderate, humane, and rational criminal justice system.

We can see evidence of these successes in the number of progressive prosecutors who won recent elections and the increasing power and voice of groups like Law Enforcement Leaders to Reduce Crime and Incarceration. We see it also in the resistance of local authorities (in Baltimore and elsewhere) against Sessions’ attempt to halt police reform. Their efforts won’t kill Trump’s regressive criminal justice agenda, but they will collectively blunt the administration’s impact and even create unexpected positive reform at every level.

In short, criminal justice will continue to transform (often in contradictory directions) under Trump. The grinding political and legal struggle we’re seeing now throughout the country will drive such change—even when it’s buried below headlines declaring that the “pendulum” has swung away from reform and rehabilitation. The history of criminal justice gives us hope: together, citizens, advocacy groups, and policy-makers can resist the second coming of retributive “law and order” and push for a safer and saner system. We always have.

Featured image credit: Donald Trump, by Gage Skidmore. CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post On criminal justice reform, keep fighting appeared first on OUPblog.

May 7, 2017

How apostrophes came to confuse us

A colleague of mine recently retired from teaching. As she began her last semester, she announced to her students that she hoped they would finally be the class where no one confused “its” and “it’s.” Her wish did not come true.

The apostrophe rules of English are built to confuse us. Not intentionally. But they have evolved in a way that can confuse even the most observant readers and writers.

How did that happen? Apostrophes made their way into English in the early 16th century, first to indicate an omitted letter or letters. The printed editions of Shakespeare’s plays, for example, use apostrophes to show words contracted such as ’tis, ’twill, and ’twas, and pronunciations such as ’cause, strok’st, and o’er. They were even used to shorten articles and possessives as in th’imperial jointress or by’r lady.

The printed plays also show the apostrophe used to indicate the possessive, as in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. But sometimes the apostrophe could indicate a simple plural. When Camillo in the Winter’s Tale refuses to assassinate the King of Bohemia, the text reads:

“If I could find example of thousand’s that had struck anointed Kings And flourish’d after I’ld not do’t.”

And the play Love’s Labor’s Lost was variously printed with no apostrophes, just one apostrophe (indicating a contraction of “labor” and “is”), or with pair of apostrophes. In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, the editorial conventions were pretty clearly in flux. Over time, the function of the apostrophe has become somewhat more codified, but there is still plenty of flux.

The apostrophe rules of English are built to confuse us. Not intentionally. But they have evolved in a way that can confuse even the most observant readers and writers.

Willard Strunk and E. B White’s Elements of Style begin their discussion of rules of usage with the dictum: “Form the possessive singular of nouns by adding ‘s.” Sounds simple enough, but it’s a rule with plenty of exceptions. Strunk and White mention some, such as the possessive of ancient proper names ending in –es and –is, and the possessive Jesus‘. They go on to call out the “common error” of writing “it’s” for “its” and “its” for “it’s,” giving the pneumonic device: “It’s a wise dog that scratches its own fleas.”

Why is the apostrophe with the pronoun an error? Well, since personal pronouns have their own possessive forms (his, hers, its, theirs, yours, ours, and whose), the apostrophe is redundant. But only the personal pronouns are exceptions. Indefinite pronouns do use them (as in “someone’s bright idea”).

Got it?

Of course, English also continues to use the apostrophe for common contractions of words like: will, am, have, are, is, and more, yielding the apostrophized forms: I’ll, I’m, I’ve, you’re, she’s, let’s, they’re, there’re, won’t, ain’t, who’s, and it’s. So it’s and its, who’s and whose, and they’re, their, and there are homophones. It’s an easy pattern to mislearn.

Plural possessive offer some challenges as well. Regular plural possessives take the apostrophe alone (so “the Fredericks’ car” but “Frederick’s car”), while irregular plurals take the apostrophe plus s (the people’s choice, women’s rights).

There are plenty more opportunities for confusion. In some editorial practice the apostrophe is used for the plurals of letters, as in “be sure to dot the i’s and cross the t’s,” or for the plurals of cited words such as do’s and don’t’s. Practice seems to have moved away from using apostrophes for the plurals of numbers and abbreviations. The Oxford Guide to Style recommends using italics or single quotes instead (but the Oxford Guide uses apostrophes for abbreviations that are made into verbs, like OK’d or KO’d). The New York Times Style Guide suggests apostrophes for plurals of abbreviations that have capital letters and periods but not for abbreviations without periods (so C.P.A.’s but DVDs).

To make matters even worse, institutionalized spellings often remove apostrophes for possessives, like the United States government’s spelling of Pikes Peak, Hells Canyon, Harpers Ferry, Toms River, and Grants Pass. Presidents Day is anyone’s guess and the Veterans’ Administration seems to have solved the problem by renaming itself the Department of Veterans Affairs.

So what’s a writer to do? If you learn all the rules and exceptions, manage to remember them in the heat of prose, and can thread your way among various editorial practices, you are probably okay. That’s a lot of work. Many of us learn our apostrophes by inferring patterns from what we read. If so, textual evidence almost certainly leads to confusion.

It’s little wonder that the apostrophes have had their detractors. George Bernard Shaw called them “uncouth bacilli.” They certainly seem to have evolved to trouble us.

Featured image credit: “Adult, blur, book” by Pexels. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post How apostrophes came to confuse us appeared first on OUPblog.

Opening the door for the next Ramanujan

As a 17-year old, I was whisked away from my little country town in Australia to study mathematics at the Australian National University in Canberra. Granted a marvellous scholarship, all my needs were met. Over the next ten years, with some detours along the way, all my living expenses were provided for as I proceeded to PhD level. At the age of 22 I married a woman that I met while on a bus going to Oxford who had just finished her studies at one of the London colleges. We had little money but nor had we any debt. That was 1979. In 2017, a corresponding couple will begin their lives together burdened by a joint student-related debt approaching £100,000, which they must try to repay, with interest, for most of their working lives.

It is still possible to learn mathematics to a high standard at a British university but there is no doubt that the fun and satisfaction the subject affords to those who naturally enjoy it has taken a hit. Students are constantly reminded about the lifelong debts they are incurring and how they need to be thoroughly aware of the demands of their future employers. The fretting over this within universities is relentless. To be fair, students generally report high to very high levels of satisfaction with their courses right throughout the university system. Certainly university staff are kept on their toes by being annually called to account by the National Student Survey, which is a data set that offers no hiding place. We should bear in mind, however, that this key performance indicator does not measure the extent to which students have mastered their degree subject. What is important here is getting everyone to say they are happy, which is quite another matter.

Srinivasa Ramanujan. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Srinivasa Ramanujan. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.This all contrasts with the life of the main character, Sri Ramanujan in the recent film The Man Who Knew Infinity. The Indian genius of the early twentieth century had a reasonable high school education after which he was almost self-taught. It seems he got hold of a handful of British mathematics books, amongst them Synopsis of Pure Mathematics by G. S. Carr, written in 1886. I understand that this was not even a very good book in the ordinary sense for it merely listed around five thousand mathematical facts in a rather disjointed fashion with little in the way of example or proof. This compendium, however, suited the young Ramanujan perfectly for he devoured it, filling in the gaps and making new additions of his own. Through this process of learning he emerged as a master of deep and difficult aspects of mathematics, although inevitably he remained quite ignorant of some other important fields within the subject.

It would therefore be a very good thing if everyone had unfettered online access to the contents of a British general mathematics degree. Mathematics is the subject among the sciences that most lends itself to learning through books and online sources alone. There is nothing fake or phoney when it comes to maths. The content of the subject, being completely and undeniably true, does not date. Mathematics texts and lectures from many decades ago remain as valuable as ever. Indeed, older texts are often refreshing to read because they are so free from clutter. There are new developments of course but learning from high quality older material will never lead you astray.

I had thought this had already been taken care of as for ten years or more, many universities, for example MIT in the United States, have granted open online access to all their teaching materials, completely free of charge. There is no need to even register your interest — just go to their website and help yourself. Modern day Ramanujans would seem not to have a problem coming to grips with the subject.

The reality, however, is somewhat different and softer barriers remain. The attitude of these admirable institutions is relaxed but not necessarily that helpful to the private student who is left very much to their own devices. There is little guidance as to what you need to know, and what is available online depends on the decisions of individual lecturers so there is no consistency of presentation. Acquiring an overall picture of mainstream mathematics is not as straightforward as one might expect. It would be a relatively easy thing to remedy this and the rather rigid framework of British degrees could be useful. In Britain, a degree normally consists of 24 modules (eight per year), each demanding a minimum of 50 hours of study (coffee breaks not included). If we were to set up a suite of 24 modules for a general mathematics degree that met the so-called QAA Benchmark and placed the collection online for anyone on the planet to access, it would be welcomed by poor would-be mathematicians from everywhere around the globe. The simplicity and clarity of that setting would be understood and appreciated.

This modern day Ramanujan Project would require some work by the mathematical community but it would largely be a one-off task. As I have explained, the basic content of a mathematical undergraduate degree has no need to change rapidly over time for here we are talking about fundamental advanced mathematics and not cutting-edge research. Everyone, even a Ramanujan, needs to learn to walk before they can run and the helping hand we will be offering will long be remembered with gratitude and be a force for good in the world.

Featured image credit: Black-and-white by Pexels. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Opening the door for the next Ramanujan appeared first on OUPblog.

Edward Gibbon, Enlightenment historian of religion

On 8 May 1788, Edward Gibbon celebrated the publication of the final three volumes of his History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire at a dinner given by his publisher Thomas Cadell. Gibbon (born 27 April 1737) was just 51; he had completed perhaps the greatest work of history ever written by an Englishman, and certainly the greatest history of what his contemporary David Hume called the “historical age,” and we think of as the Enlightenment.

What made Gibbon’s Decline and Fall an Enlightenment history? One obvious answer is its apparent hostility towards religion, Christianity in particular. That hostility was manifest above all in the notorious chapters 15 and 16 with which Gibbon ended the first volume, published in 1776. In these, Gibbon treated, first, “the progress of the Christian religion” between the death of Jesus and the ascent of Constantine to the Empire, and then the persecutions to which Christians had been subject since the reign of Nero. Gibbon gave offence from the very beginning of chapter 15, by ostentatiously setting aside any explanation for the rise of Christianity as the work of divine providence, and focusing instead on five “secondary causes,” including the “intolerant zeal” of the Christians (a zeal they inherited from the Jews), their beliefs in the immortal soul and in miracles, their pretension to purity of morals, and their discipline, which quickly made the Church an independent state within the Empire.

Worse still were Gibbon’s footnotes—a relatively recent scholarly and printing innovation, which Gibbon effectively weaponised. The irony may seem gentle—as in St Augustine’s “gradual progress from reason to faith” (ch. 15, n. 37)—but it also kicks, as in the later observation that Augustine’s “learning is too often borrowed, and his arguments are too often his own” (ch 28, n. 79). To Gibbon’s clerical contemporaries (some of them his friends), this, and much else, was no better than a sneer.

But was it as simple as that? We know that Gibbon himself was taken aback by the clerical response. He issued a famous Vindication (1779) of his scholarship, but in re-issues of volume I, he also muted his sneers. Modern Gibbon scholars, notably John Pocock, David Womersley, and Brian Young, believe that we should take another look at his treatment of religion.

For Gibbon had an abundance of the historian’s greatest attribute—curiosity. That too is evident in his decision to write chapters 15 and 16. Before he tackled the conversion of Constantine and the adoption of Christianity as an Imperial religion, he needed to explain why Christianity had grown strong enough to attract Constantine’s allegiance, and why the Christians had so wilfully refused the toleration extended to them by Roman paganism. But it was once the Church had established itself that Gibbon faced his major challenge.

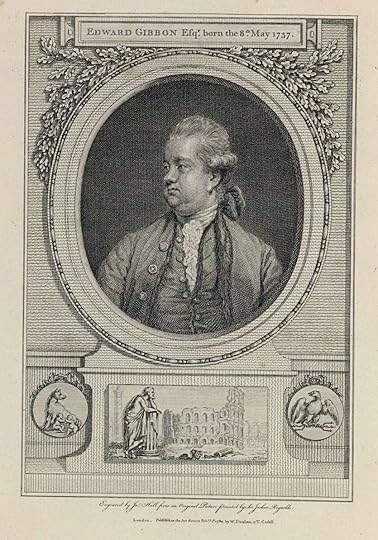

Portrait of Edward Gibbon (1737–1794): The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Edward Gibbon (1737–1794): The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.For he now engaged with ecclesiastical history as a form of “sacred history.” To its adherents, the Church was the “body of Christ” and heir to Christ’s mission; to write its history, the task undertaken by Eusebius in his History of the Church (c.300–325), was to perpetuate the truth claims of that mission. Gibbon may have been indifferent to those truth claims, but he realised that there could be no history of the Christian Church which did not do justice to its theology, and the fierce disputes which accompanied the establishment of “orthodoxy”.

Read with one eye chapter 21, in which Gibbon recounted the great controversy over the Trinity, or chapter 48, in which he did the same for the Incarnation, may appear master-classes in keeping a skeptical, disbelieving distance. But read with both eyes, they reveal Gibbon’s effort to understand Christianity as its adherents did. If Gibbon were only a critic who had not made the effort to understand the history of the Church from within, he could never have explained not merely the “triumph” of Christianity, but the extent to which it went on to sustain the Empire it had come to subvert, and to facilitate the transmission of the culture of the ancient world to the modern.

Even so, Gibbon’s most remarkable exercise of historical curiosity was still to come. When he turned in volumes 4–6, to consider the fate of the Byzantine Empire, he realised that “the triumph of barbarism and religion” over the Roman Empire had been as much the achievement of Islam as of Christianity. Gibbon took up the challenge of understanding Islam, and its even more rapid rise, in Volume 5, chapters 50–52. To do so, he had to overcome unaccustomed obstacles, not least that he did not know Arabic: he was therefore reliant on Christian scholarship in Latin and modern European languages, much of it hostile to its subject. But as his footnotes show, he was on the alert for bias, while drawing on the observations of curious travellers to depict the context in which Muhammad (“Mahomet”) had successfully gathered support for his message.

The role of Mecca and Medina as rival cities, strategically placed for trans-desert commerce, along with the martial culture and tactical flexibility of the pastoralist “Bedoweens,” helped him to explain the Prophet’s initial survival and eventual triumph. But here too Gibbon recognised the need to understand the content of the new religion, the extent to which it was a response to both Judaism (from whose Patriarch, Abraham, the Arabs too were descended, through his first-born, Ismael), and an increasingly sectarian Christianity. Amidst their ever more convoluted disputes, the appeal of Muhammad’s simple, “unitarian” idea of God was clear. But if Islam was a religion of enthusiasts, it was also strikingly tolerant by comparison with Christianity: “the passages of the Koran in behalf of toleration—Gibbon noted—are strong and numerous” (ch. 50, n. 114).

History as Gibbon wrote it in the Decline and Fall was thus far from a simple exercise in the subversion of religion. At the least, curiosity was combined with scepticism, and translated into a willingness to engage with the “sacred”. Gibbon was not, of course, every Enlightenment historian. He stands out even from his greatest contemporaries, Voltaire, David Hume, and William Robertson, in his curiosity as well as in his scholarship and his style. But he is representative of the Enlightenment’s commitment to understanding as well as to criticism, and not least to understanding the power of religion.

Featured image credit: The Emblem of Christ Appearing to Constantine / Constantine’s conversion Peter Paul Rubens, 1622. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Edward Gibbon, Enlightenment historian of religion appeared first on OUPblog.

Philosopher of the month: Simone de Beauvoir [timeline]

This May, the OUP Philosophy team honors Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986) as their Philosopher of the Month. A French existentialist philosopher, novelist, and feminist theoretician, Beauvoir’s essays on ethics and politics engage with questions about freedom and responsibility in human existence. She is perhaps best known for Le deuxième sexe (The Second Sex), a groundbreaking examination of the female condition through an existentialist lens and a key text to the Second Wave feminist movement of the 1960s and 70s. Even among her critics, Beauvoir is widely considered the most significant influence on feminist theory and politics during the course of the twentieth century.

Simone de Beauvoir earned her degree from the Sorbonne at a time when higher education was just becoming accessible to French women. When she was twenty‐one, she became the ninth woman to obtain the prestigious agrégation from the École Normale Supérieur, the youngest ever to do so in philosophy. There, Beauvoir met young philosophy student Jean‐Paul Sartre, who would soon be known as the founder of existentialist philosophy. Throughout their lifetime partnership, Beauvoir and Sartre collaborated intellectually and produced several projects, including founding the French political journal Les Temps Modernes, which Beauvoir edited all her life. From 1931 to 1943, Beauvoir taught at several institutions, after which she concentrated on her writing. She was the author of several novels, including She Came to Stay, The Blood of Others, and The Mandarins, for which she won the prestigious Prix Goncourt. She also produced philosophical treatises such as The Ethics of Ambiguity, a multivolume autobiography, travelogues, and The Second Sex, which became her best-known work.

In The Second Sex, De Beauvoir explains, women are cast as “the other” in relation to men. A patriarchal society imposes upon women an alienated, objectified image of themselves, rather than accepting women as free subjects acting in their own right. The process of alienation, embedded in the earliest childhood experiences, may result in the internalization of and identification with the patriarchal image imposed upon women. In the framework of this analysis, De Beauvoir addresses history, psychoanalysis, and biology, before offering a complex analyses of topics including childhood, heterosexuality, lesbianism, marriage, childbirth, menopause, housework, abortion, contraception, women’s work outside the home, women’s creativity, and women’s efforts to combine independence with authentic sexual freedom. From its publication in 1949 to the present day, while The Second Sex has not been without its critics, the issues it raised were to become central to feminist thought in the late 1960s.

For more on De Beauvoir’s life and work, browse our interactive timeline below.

Featured image: Bridge over the Seine River in Paris. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Philosopher of the month: Simone de Beauvoir [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

May 6, 2017

Reflections on Freud, the first “wild analyst”

Sigmund Freud was a more radical and speculative thinker than many have been willing to concede. This is apparent in his many discussions of childhood sexuality. For example, few really understand how Freud’s conclusions about childhood sexuality predate by decades the clinical observations of actual children – later done by dutiful analysis, most often by women analysts like Melanie Klein and Freud’s own daughter Anna Freud, most often of children within their own families or close friends. Beyond that, readers sometimes forget that Freud’s commitment to speculation is practically institutionalized within psychoanalysis as the “metapsychology,” Freud at his most theoretical – and also most misunderstood. But it’s really very simple: the metapsychological speculations of the middle period (1912-1920), culminating with the death drive theory of Beyond the Pleasure Principle, simply developed the late Romantic philosophy and materialism of the early (1897-1912) and pre-psychoanalytic periods (before 1897); while the cultural works of the final period (1920-1939) simply developed and ratified the metapsychology of the previous three periods.

Yet instead of finding continuities between these four periods, scholars routinely favor a history characterized by disruption, internal revolution, and discontinuity. Instead of simply accepting the role that Freud himself assigned to metabiological speculation, scholars have spent a lot of effort minimizing or effacing it (thus ‘saving Freud from Freud’). Consequently, instead of seeing Freud’s final phase of cultural works as the natural culmination of Freud’s thinking about history and psychoanalysis, scholars have mostly treated it as a sideshow, sometimes an embarrassing sideshow, of incidental importance to the basic ‘discoveries’ of psychoanalysis.

But these scholars are wrong, as informed readers have known since the publication of Jones’s Freud biography in 1957; or since the publication of Frank Sulloway’s Freud, Biologist of the Mind in 1979. In both works one is left with a very clear picture of Freud’s commitments to biology. Take Freud’s last complete work, Moses and Monotheism, which has at times been dismissed as the ramblings of a self-loathing misanthrope with failing intellect. While that’s a convenient way to avoid thinking about Freud’s lifelong investment in biology, there’s no evidence at all that the quality of Freud’s thinking declined with age and sickness – only its quantity. The Moses is not, furthermore, a reassuring example of the so-called “late style” – as claimed by Edward Said – since Freud’s misanthropy and brooding late Romanticism didn’t just pop up at the end. On the contrary, and as Said should have known, the so-called “late style” is practically a staple of Freud’s thought throughout his life. Far from disposable, therefore, Moses and Monotheism is the inevitable consequence and, indeed, crowning achievement of Freud’s lifelong Lamarckianism.

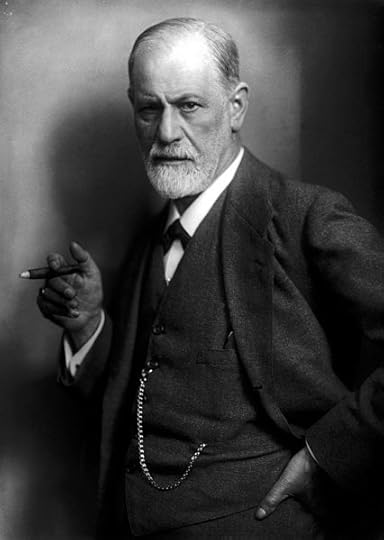

Sigmund Freud, founder of psychoanalysis, holding cigar. Photo by Max Halberstadt. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Sigmund Freud, founder of psychoanalysis, holding cigar. Photo by Max Halberstadt. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Freud’s rude quip that an American patient was unsuited for psychoanalysis because he ‘had no unconscious’ doubles as my own quip to scholars, who refuse to follow Freud down the path of his own most radical speculations. Freud’s own version of the unconscious, based on psycho-Lamarckianism, is mostly missing from the literature – American and European.

This motivated gap in the literature on psychoanalysis, fueled by an incuriosity bordering on professional malpractice, is easily addressed by simply reading Freud. In Moses and Monotheism, Freud playfully enacts, through his rhetoric of repetition, the very theory of Lamarckian inheritance that characterizes his thinking. Such amused yet meaningful playfulness is hardly new in Freud’s work, and its appearance in his last major publication should reassure us that we are very far from an aberrant and therefore disposable ‘old Freud’. In fact, I think just the opposite. In my view the late Freud is very plainly and expertly instructing readers about the meaning of psychoanalysis, the meaning of his own legacy, and the foundation of his life’s work – all of it. And yet his playful discussion of repetition and recapitulation has never, to my knowledge, been fully interpreted in the vast literature on psychoanalysis – nor has it been understood. That’s pretty stunning for a work that was published about 80 years ago.

So why, again, was it missed? Well, the “American” tradition of psychoanalysis – notoriously practical-minded, optimistic about cure, love, and work, and more generally about the future – has made this work of interpretation, based on the fact of Freud’s psycho-biologism, especially difficult. The metabiology, even after Sulloway’s landmark book, remains nearly invisible. Yet Freud was always inclined toward abstraction and philosophy, always driven toward a brooding view of human nature, and, on the basis of his analysis of prehistory, was always pessimistic about change, cure, and the future. Freud’s psychoanalysis was not, in short, “American.” It was perversely European, but on its own terms, in its own way, always eccentrically (so much so that European thinkers of Freud have rarely understood this Freud any better than the Americans).

Freud was the first and only authorized ‘wild analyst’. This isn’t a complaint. The radicality of Freud’s vision, however dated and scientifically untenable, remains the most compelling and interesting aspect of his contested legacy. His passion for thinking is what outlives all his mistakes. It behooves us to respect that legacy, and not simply ignore or transform it into something else, something convenient, something un-Freudian.

Featured image credit: Group photo 1909 in front of Clark University. Front row: Sigmund Freud, G. Stanley Hall, Carl Jung; back row: Abraham A. Brill, Ernest Jones, Sándor Ferenczi. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Reflections on Freud, the first “wild analyst” appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers