Oxford University Press's Blog, page 373

April 28, 2017

100 years of E. coli strain Nissle 1917

Escherichia coli (E. coli) is a common bacteria found in the the lower intestine of warm-blooded animals, including humans. Whilst most strains are harmless, some can cause serious gastroenteritis, or food poisoning. However, one special strain, E. coli strain Nissle 1917 (abbreviated as EcN), is specifically used to prevent digestive disruption. Since its discovery 100 years ago, EcN is probably the most intensely investigated bacterial strain today. Learn more about this special strain below as Ulrich Sonnenborn, winner of the FEMS Microbiology Letters Minirevew Award 2016, takes you through its discovery and history throughout the last 100 years, and suggests how scientists will develop new ways to use EcN in the future.

How did Alfred Nissle first uncover the possibility that certain E. coli strains could be defending against other pathogens in the gut?

During their medical studies at the beginning of the last century, students in Frieburg (southern Germany) were also trained in microbiology. In practical courses they had to mix their own stool samples with pure cultures of pathogenic Salmonella strains provided by Professor Nissle, spread the mixture out on solid culturing media on agar plates, and incubate it overnight to expedite bacterial growth. Next day, the plates were inspected. Usually, the Salmonella bacteria prevailed forming large colonies and overgrowing the other gut bacteria. However, in rare cases, only poor or even no growth of Salmonella occurred. Instead, E. coli colonies dominated. This observation led Nissle to the idea that in these cases the stool microflora might contain E. coli strains that were able to inhibit growth of Salmonella. Later, Nissle could corroborate his hypothesis in laboratory experiments by co-culturing mixtures of Salmonella strains with different E. coli isolates obtained from stool samples of healthy people. For this special feature of some E. coli strains of the normal intestinal microflora to inhibit the growth Salmonella and other enteropathogens, Nissle coined the term ‘antagonistic activity’.

How was the E. coli strain Nissle 1917 first isolated?

This special E. coli strain was isolated in 1917 during the First World War by Alfred Nissle from a stool sample of a German soldier who was at that time in a military hospital near Freiburg. This soldier, in contrast to his comrades, had not developed diarrhea or any other intestinal disease, when deployed in a region of the Balkans (Dobrudja), then heavily contaminated with pathogenic Shigella bacteria. Nissle suspected this soldier to carry an antagonistically strong E. coli strain that might have protected him from catching dysentery. In fact, this soldier carried an E. coli strain (later named strain Nissle 1917) that in laboratory tests showed strong antagonistic activity against pathogenic gut bacteria.

Why can E. coli Nissle 1917 act as an antagonistic microbe, whilst other strains of E. coli are so pathogenic?

Compared to the great majority of non-pathogenic E. coli strains in the gut of humans and animals, pathogenic strains are carrying additional genetic information on their genomes coding for so-called virulence factors that make them pathogenic. Since the presence of such virulence genes are not necessary for a strain to be a member of the species Escherichia coli, they are therefore called ‘luxury genes’ by molecular geneticists. As could be assumed from its history (isolated from the gut microflora of a healthy human), later molecular genetic analyses have shown that E. coli strain Nissle 1917 does not carry any virulence genes and thus is not pathogenic to humans and animals. However, the EcN strain contains additional genes which make it different from other non-pathogenic E. coli strains. These additional genetic elements are called ‘Genomic Islands (GEIs)’ and have been acquired during the evolution of the Nissle strain by horizontal gene transfer from other gut bacteria. These GEIs have been stably integrated into the EcN genome and are carrying genes that code for the strain-specific fitness factors of EcN, e.g. for its antagonistic activities against pathogenic enterobacteria which are due to the production of antimicrobially acting small peptides called microcins.

How do you think E. coli Nissle 1917 will be used in the future?

In the future, E. coli strain Nissle 1917 (EcN) will still be used as a medical probiotic, or in pharmaceutical terms as a ‘live biotherapeutic product’, to treat or prevent specific intestinal infections and diseases. In addition, ongoing research on genetic manipulations of EcN will yield constructs with novel properties. As EcN is a good colonizer of the gut, EcN derivatives may be used in the future as carriers of bioactive molecules for the treatment of other intestinal diseases. Furthermore, EcN derivatives may also be used for the construction of vector systems for the development of novel live oral vaccines.

Featured image credit: Escherichia coli: Scanning electron micrograph of Escherichia coli, grown in culture and adhered to a cover slip by Rocky Mountain Laboratories, NIAID, NIH. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post 100 years of E. coli strain Nissle 1917 appeared first on OUPblog.

What would Margaret Oliphant have said about Trump and Brexit?

What would Margaret Oliphant (1828–1897), one of the most prolific of commentators on nineteenth-century society (98 novels; 50 or more short stories; 25 works of non-fiction, and over 300 essays) have made of the politics and social mores influencing events today? In particular how would she have reacted to the identity politics behind the plea for a hard Brexit, the current referendum stand-off between England and Scotland, and the triumph of Trump in the US presidential election?

Fiction relies upon novelists’ capacity to persuade readers to travel sufficiently far beyond the boundaries of their own experience, circumstances and mindset to imagine inhabiting and seeing the world from another point of view. To create convincing characters and dramatic plots, novelists need to be aware of the elements differentiating individuals and groups from one another as much as the basic human traits which bind us together. Much of Oliphant’s success as a social commentator came from her consciousness of her own multiple identities. Economically she migrated from the relative poverty of a humble clerk’s home, to the upper-middle-class lifestyle of the Home Counties.

As a woman, she experienced the roles of daughter, sister, wife, widow, mother, and aunt and became breadwinner for her extended family in the male-dominated world of nineteenth-century publishing. Born a proud Scot and retaining a pronounced accent, she was raised in a Scottish ex-pat community in Liverpool, but in adult life chose to settle in Windsor so as to give her sons an education at Eton. Yet she was also a committed cultural Europhile who developed sufficient facility in French and Italian to be appointed general editor of Blackwoods’ Foreign Classics for English Readers, and to be commissioned to provide a series of popular historical accounts of famous cities, among them Florence, Venice, and Rome.

“Margaret Oliphant Oliphant” by Frederick Augustus Sandys. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Margaret Oliphant Oliphant” by Frederick Augustus Sandys. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Her best fiction is often created by the tension between these competing roles, loyalties, and milieux. Chronic sea-sickness prevented her from ever making the transatlantic voyage, though the light her novels cast on British and European society created a ready readership in both America and the colonies. So what would she have made of Donald Trump? Businessmen, it has to be said, do not get a good press in her fiction, largely on account of their inability to perceive either education or culture as anything other than a purchasable commodity designed to secure a particular class status.

Her later, darker novels were to provide an excoriating picture of the vulgar materialism which she felt had beset late Victorian society. In Trump’s case, she would also have deplored his connections with Scotland’s golf industry. To Oliphant, the institution of the golf-club symbolized the all-male preserve, capable of fostering the environment in which Trump’s infamous series of sexist remarks might be deemed acceptable: in which context it is perhaps worth remembering that it was commercial interest rather than a regard for gender equality that finally led Muirhead Golf Club to admit female members in March 2017.

Oliphant’s life story and creative use of her imaginative powers, serve to suggest that merely dismissing identity politics as an assault on democracy and liberal values is misplaced. Pride in, and loyalty to, the best values of a particular group are not necessarily inimical to an appreciation of the needs and virtues of other communities of interest. Rather it should be our educational aim to arouse awareness of the multiple identities we each inhabit, composed variously by such matters as gender, ethnicity, religion, economics, social class, educational opportunity, and locality, so that we are not tempted to fall back instinctively into the unthinking clichés of the group with whose interests we most easily relate.

Featured image credit: Title page of the first edition of Squire Arden, 1871. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What would Margaret Oliphant have said about Trump and Brexit? appeared first on OUPblog.

Challenges of a hometown oral history performance

One of my first oral history performance experiences was watching E. Patrick Johnson perform Pouring Tea: Black Gay Men of the South Tell Their Tales, the readers theater version of his oral history collection, Sweet Tea: Black Gay Men of the South, at Texas A&M University. I was an undergraduate studying English and Theatre, and I was mesmerized by the histories Dr. Johnson shared. Learning about his research, the relationships he developed with interlocutors, and the performances he created was the push I needed to pursue graduate degrees that would teach me the skills to become a critical ethnographer committed to oral history performance.

Fast forward to last October when you may have passed me in the halls of OHA’s Annual Meeting, or joined me in the audience of Saturday’s Plenary where once again I witnessed the power of Dr. Johnson’s work. I was a fourth-year Ph.D. Candidate attending OHA for the first time, spinning from my recent exams and prospectus defense, and preparing for my first oral history performance that was scheduled to take place in November. I was grappling with two big questions: Is what I’m doing actually oral history? How do I present these histories in a way that is ethical, engaging, and critically contextualized?

Simple questions, right?

I am happy to report that my first question was embraced, addressed, and debated the entire weekend. I came away with a strong sense of my position as a critical performance ethnographer who is committed to an oral history methodology. My second question is one that continues to morph and shift as I pursue my research, but I want to share some of what I’ve learned about performance and oral histories.

My dissertation is a hometown ethnography about public school desegregation in Longview, Texas. Thus far I have interviewed ten interlocutors who were present during desegregation as teachers, administrators, students, and parents. Their stories are powerful and offer insight into the experiences of both white and black Longview residents. One of the biggest challenges of this work is my relationship with my hometown. My sisters and I completed our K-12 education in the school district I am studying, as did our parents. All of my grandparents and my mom taught in the school district, and my father served on the school board for many years. After my father passed away in 2010, the school district named the new performing arts center at the high school after him. My position is undoubtedly privileged, and my understanding of my hometown, my family’s legacy, and my education experience is distinctly informed by my whiteness.

Wrestling with all of these complexities is really challenging and I often find myself questioning what actually needs to be part of my dissertation. All of it is important and this web of relations undoubtedly informs my research… but where does it all fit?

Enter: Unpacking Longview, my solo performance-as-research play. I have found that performance is an amazing place to work out the connection between all of these histories. Before I began writing my play I knew that the voices and stories of my interlocutors would be present throughout the piece, but I didn’t know how to incorporate my own story or how to capture the distinct history and culture of East Texas without simply telling story after story after story. I was worried that there would be no dramatic action if I just sat there and explained everything to the audience. Eventually, I settled on a combination of three performance styles: autobiography, oral history performance, and camp.

The performance begins with Elizabeth-the-researcher-and-hometown-girl (that’s me!) searching and digging through boxes, trying to make sense of everything that has been left behind.

This autobiographic part introduces the importance of my family’s history in East Texas and the way my father’s life and death inspires my research. I also acknowledge that much of my father’s success is reliant on his whiteness, and the advantages afforded to him as the grandson of a successful cotton gin owner.

After this reasonably somber foundation is laid, Elizabeth-the-researcher exits in search of a family memento that is lost amongst all the boxes. A radical shift occurs in the lighting and projections on-stage, a booming voice comes over the loud-speaker introducing the one and only–TEXAS MELT.

That’s right. I have my very own all East Texas, all the time, alter-ego. Unsurprisingly, Texas Melt is BIGGER than life, loves to dance and yodel with the skeletons she unpacks throughout the show, and really loves giving the audience a piece of her East Texas mind. Quite simply, she’s a hoot and a half, y’all. What I love about Texas Melt is that she not only provides some much needed comic relief, but she can say things Elizabeth-the-researcher-and-hometown-girl can’t. Texas Melt is the wise(ish) fool who explains how things “really” work in East Texas.

The autobiographic moments and Texas Melt’s interruptions are interspersed with oral history performances. These oral histories dialogically present histories from one white school administrator, one parent who graduated from Longview Negro High School and had two daughters in school during desegregation, one current high school Spanish teacher who was one of the only Latinas in the district during desegregation, and another current teacher who chose to attend the white school during desegregation by choice.

For these scenes, the audience hears a snippet of the interview with the interlocutor’s voice before I step into their story and continue performing it for the audience.

I performed Unpacking Longview last November at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and will take it to Longview this fall. Now, you might notice I’m not telling you much about the ending or other details of the play. Honestly, that’s because I’m not sure it’s really done yet. It’s a work in progress that keeps shifting and revealing new things to me. Oral history performance is the spine of this work, and I had no idea what would happen when I combined campy Texas Melt and my personal story with a performance style that often stands alone. Fortunately, mixing three styles enriches the overall telling of the story and enhances the critical voice of the piece overall. And who knows, maybe Texas Melt is an oral historian, after all.

Featured image and images included in the post are by Headen Photography, used with permission.

The post Challenges of a hometown oral history performance appeared first on OUPblog.

Modern life and clinical psychology

It’s a sad but very modern paradox. Despite the many wonderful opportunities and options like education, technologies, internet resources, and travel that are open to young people today, young people’s mental health today has never been so fragile. In contrast to the frequently portrayed images of happy, successful, and socially connected millennials in selfies, outspoken twitter messages or entertaining Facebook images, in fact many millennials seem to feel more empty and lost than ever. Self-harm is widespread, and most current reports suggest that substance misuse and eating disorders are on the increase. Depression is common, as many young people think themselves to be failures in the rapidly changing world where nothing is secure, and where competition for jobs or places at University adds pressure and anxiety. Even the very young face demands: in Silicon Valley, USA, for example, children as young as 4 are exhausted due to pressure from so called ‘helicopter parents’ and teachers to (over) achieve and compete with their peers.

And when all these young people grow older, for some it doesn’t get much better: the pressure to want and have it all (successful careers, relationships, hobbies, a home, starting a family) is increasingly burdensome for young adults in their twenties and thirties. Psychologically, constant opportunity becomes an internal sense of not being able to settle for ‘good enough.’ All relationships seem temporary; okay until someone better comes along. Everyone else seems to be having much more fun than you, and there seems to be no escape from the relentless evidence that you are not as attractive, popular, successful, and funny as everyone else. Many families don’t offer a safe-haven either: communities are fragmenting, relationships break down and economic pressures mean that people are increasingly isolated and lonely.

Faced psychological distress, many of those in previous generations kept a ‘stiff upper lip’ and did not seek much emotional support until they reached the verge of breakdown, at which point they turned to the doctor for help in the hope that mental suffering could be reduced by medication. But we know now that it is relatively rare for psychological distress to result from a simple medical problem: instead symptoms of depression or anxiety (e.g. lack of sleep, low mood, panic attacks) usually result from someone’s life experiences in a complex web of relationships and circumstances. While medication can help some people in some circumstances, many psychologists and many of their clients now believe that it’s much better in the longer term to try to find out what lies beneath such complex feelings, and try to do something about these underlying patterns. And thankfully, psychological struggles and mental health treatment are nowadays being discussed much more openly than ever before. Public figures including politicians, celebrities, and even members of the royal family in the UK have all recently talked quite explicitly about their mental health difficulties and therapies.

Although considerably less money is still spent on mental health than physical health, psychological services are at last growing too. For example the UK government has started to address the widespread need and demand for psychological therapy through the Increasing Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) initiative, which has helped over 9,000 people a year since 2008. Psychological support is provided free within the NHS by a range of therapists, mental health workers, and clinical psychologists, to people of all ages, with a wide range of psychological difficulties, although there may be waiting lists. And although the continuation of mental health services through Obamacare in the US is now uncertain, psychologically based mental health provision has increased in the US too.

The pressure to want and have it all (successful careers, relationships, hobbies, a home, starting a family) is increasingly burdensome for young adults in their twenties and thirties.

In parallel, stigma about seeking help is slowly diminishing. Although going to see a clinical psychologist can still raise a frisson of apprehension in many people (can you read my mind?), more people know now that psychologists are there to listen, reflect, and support you through difficult phases in your life. Just like a personal trainer might help you improve your physical shape, psychologists help you towards a healthier mind and better relationships. Clinical psychologists do not judge, blame, or ‘tell you what you do wrong’, but have been specifically trained to understand and make senses of people’s difficulties. That is, they see people’s problems as resulting from their social and personal histories, as well as any biological predisposition or health condition. This means that a psychologist sees each person as a unique individual, who is living in a particular family or set of relationships, and who (like everyone else) is striving to overcome the challenges that life throws at them. Many psychological struggles make perfect sense once we can understand people’s past, current lives, and circumstances. People do usually try to resolve their own problems and cope the best they can, yet they may use ways that actually make things worse, not on purpose but because they don’t know what else to do and can’t find a way out.

Based on this individual understanding, and in line with psychological theories, and published evidence on what works for other people with similar difficulties, the clinical psychologist may then offer talking therapy. Talking therapy is not always easy or a ‘quick fix’ but it is something you do in partnership: to work together to puzzle out what is causing and maintaining your distress, and then to try and change things for the better. Many people now receive good quality psychological therapy which allows them to resolve their hurt or puzzlement in a way that is tailored to them individually, by addressing the underlying problem, not just the symptoms. Although psychological problems seem to be widespread in our society, there are ways out, and currently at least there are clinical psychologists being trained who can help.

Featured image credit: Sky Puzzle by Jared Tarbell. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Modern life and clinical psychology appeared first on OUPblog.

April 27, 2017

Managing stress: body

Stress, anxiety, and tension can be regulated by changing your perspective on forthcoming events or using techniques such as mental imagery or meditation, but they can also be controlled by what you physically do with your body. Techniques such as muscle relaxation, relaxed breathing, and exercise can all be used to decrease the impact of your stress response.

Relax your muscles: You’ve probably noticed that stress, anxiety, and worry can cause you to tense up in certain parts of your body, such as your upper shoulders. Have you also noticed that relaxing your muscles can reduce stress, anxiety, and worry? This works like a two-way street in that your mind can influence what your muscles do, but your muscles can also influence what your mind does. So in order to calm your mind more effectively, one of the key skills is muscle relaxation.

Try sitting or lying comfortably and consciously relaxing each of your muscle groups (e.g., starting at the head and working down the body). Pay special attention to common trouble spots, such as the forehead, jaw muscles, and shoulders. Smooth your forehead, unclench your jaw, put a slight smile on the corners of your mouth, and let your shoulders relax and drop into a more comfortable position.

Helpful guides for muscle relaxation and other stress management techniques are readily available on YouTube. Try a few out until you find some you like and then practice regularly.

Muscle relaxation instructions often tell you to first deliberately tense your muscles and then relax them. While this seems paradoxical, the tense-relax technique is actually very helpful at producing deep relaxation, perhaps deeper than you’ve ever felt before. However, if you have a medical condition that makes it unhealthy or impossible to follow the tension instructions, just ignore those and follow the instructions to relax your muscles.

Relax your breathing: Under high levels of stress, your body’s “fight or flight” response is activated, often leading to more rapid, shallow breathing. By learning to regulate your breathing, you can gain some control over this stress response.

POP House Meditaiton Center Thailand, Khlong Luang, Thailand by kosal ley. Public domain via Unsplash.

POP House Meditaiton Center Thailand, Khlong Luang, Thailand by kosal ley. Public domain via Unsplash.Many people have heard that taking deep breaths can help decrease stress and anxiety, and that’s true. However, most people haven’t been taught how to do it in the most helpful way.

The secret to relaxed breathing is to push your stomach outward as you inhale. This allows you to inflate your lungs more fully so you can breathe more slowly. Instead of breathing about 14 times a minute like most people, or about 18 times a minute like someone who’s anxious, work toward a slower, more relaxed breathing rhythm of six to ten times per minute.

Try to spend a little longer blowing the air out, as this is the most relaxing part of the breath cycle. Breathing in this way will turn down your body’s fight-or-flight response system and allow you to relax more fully and let go of some tension.

Smartphone users can find helpful training apps for relaxed breathing. Free relaxed-breathing audio training is also available via numerous Internet sites.

Relax with physical exercise: Regular exercise has been reliably shown in research to be an effective way to reduce anxiety and tension and seems to work by relaxing both the body and the mind, as well as by increasing confidence. To use this stress reduction technique, plan and implement a program of regular exercise with the guidance of your healthcare providers.

Even if you don’t exercise regularly, getting out and walking or doing some other physical activity can help you relax during times of extra stress.

Regular practice of these physical techniques, and/or previously mentioned techniques that focused on personal perspectives and the mind, will help you gain a sense of control over your personal experience of stress, anxiety, and tension. With these under better control, you’ll have more energy and focus for making other positive changes in your life.

Keep in mind that these self-management techniques work better the more you practice them. Also be aware that it’s best to practice these techniques during less stressful times until you become skilled enough to use them during times of high stress.

Featured image credit: ASSOS CAMP in Healdsburg, bicycle ride mornings and wine in the afternoon by Adrian Flores. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Managing stress: body appeared first on OUPblog.

Best librarian characters in fantasy fiction

Libraries often feel like magical places, the numerous books on every shelf holding the ability to transport their reader to new and wonderful worlds. In the words of Terry Pratchett: “They thought the library was a dangerous place because of all the magical books…but what made it really one of the most dangerous places there could ever be was the simple fact that it was a library.” Libraries in particular seem to have an enchanting power for writers: in many novels, the multiple possibilities that a room of books holds is transformed into literal magic, with libraries becoming doors to infinite other worlds. As the navigators of these boundless realms, fictional librarians are often also given magical powers, as the only ones who can truly understand the library’s mystical ways. We have compiled a list of our favourite magical librarians, whose powers go beyond their intellectual prowess:

1. The Librarian from the Discworld series by Terry Pratchett

Pratchett’s Librarian, who manages the library at the Unseen University, is probably one of the most famous fictional librarians. Once a human wizard, the Librarian found himself turned into an orangutan by a wave of reality-altering magic: something which helped him in his role, as opposable toes are useful for sorting and re-shelving books. Aside from his accidental change of species, the Librarian is notable for being a member of the Librarians of Time and Space, meaning that he can access and navigate the L-Space, an inter-dimensional zone which links all libraries and all books. He can go back in time to see when certain books were stolen, or save priceless texts from being destroyed in ancient fires. “The Discworld as appears in Sky One’s adaptation of The Colour of Magic.” Fair use via Wikimedia Commons.

“The Discworld as appears in Sky One’s adaptation of The Colour of Magic.” Fair use via Wikimedia Commons.

2. Irene from The Invisible Library by Genevieve Cogman

Irene is a librarian, which in Cogman’s universe makes her half-rare book collector, half-spy. Working for the inter-dimensional Library, she must go into numerous parallel universes, collecting rare books that are unique to that world, at whatever cost. Armed with the Language, a magical form of universal speech that can alter the reality around her, Irene performs her duties, not for the power, or the ability to change the courses of the worlds she enters, but because “the deepest, most fundamental part of her life involved a love of books.”

3. The Cheshire Cat from the Thursday Next series by Jasper Fforde

The world of Jasper Fforde’s Thursday Next series revolves around books—Next goes from being a Literary Detective in her world, maintaining the peace between the warring Shakespearean scholars, to working for the Great Library in Jurisfiction, which polices unruly fictional characters, dangerous plot holes, and outbreaks of the Mispeling Vyrus. While she is not technically a librarian, it is the Cheshire Cat (or the Cat Formerly Known as Cheshire, or Unitary Authority of Warrington Cat) who acts as her guide in the 52 levels and 26 basements of the Great Library, helping her find the books she needs to jump through in order to maintain order between genres. Presumably, the ability to appear and disappear anywhere at will is both useful for navigating this gargantuan, ever-expanding building, and for reaching the highest shelves.

4. Lirael from Lirael by Garth Nix

The Library of the Clayr in Garth Nix’s Lirael is a dangerous place, a repository not just of books but numerous untold evils: “fell creatures, old Charter-spells that had unraveled or become unpredictable, mechanical traps, even poisoned book bindings.” Upon their recruitment, librarians are given magical daggers and instructed to keep a whistle on hand, to call for help if they ever find themselves incapacitated by the library’s hazardous denizens. Lirael herself braves numerous monsters in her capacity as a librarian, such as the strange, insect-like stilken. Lirael is also notable in her relationship to the library: it is the place that she finds sanctuary and acceptance, and where she finds her closest friend, the Disreputable Dog. The library is her way of escaping the pressures of her life at the Clayr, finding the wisdom and strength among the stacks that unlocks her true destiny as a Remembrancer—someone who can access living memories of the past.

5. Dewey Denouement from The Series of Unfortunate Events by Lemony Snicket

While Lemony Snicket’s Dewey Denouement doesn’t have magic of his own, he hordes arcane knowledge, such as the mysterious sugar bowl, in his library, which is hidden under the pond outside the Hotel Denouement. He has lived his life according to library science, honoring his namesake by organizing his hotel according the Dewey Decimal system, and building a library catalogue of evidence to hold against every villainous member of the mysterious VFD (including a record of the 27 cakes that the dreadful Count Olaf has stolen).

Authors gravitating towards libraries as a setting for their work seems natural, given their obvious love of literature. But the portrayal of a library as a mystical place of dangerous, reality-bending secrets, and librarians as spies, warriors, and inter-dimensional travelers shows not just a love of words, but a longing for the places they can take us—and untold secrets they hold. The library, and its often magical qualities in fiction, literalises the idea that knowledge is power (or, as Pratchett words it: Books = Knowledge = Power = (Force x Distance^2) ÷ Time).

Featured image credit: “The Librarian from Discworld” by Martin Pettitt. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Best librarian characters in fantasy fiction appeared first on OUPblog.

How well do you know John Stuart Mill? [quiz]

This April, the OUP Philosophy team honors John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) as their Philosopher of the Month. Among the most important philosophers, economists, and intellectual figures of the nineteenth century, today Mill is considered a founding father of liberal thought. A prolific author, Mill’s collected works encompass thirty-three volumes ranging in subject from philosophy to social issues and beyond.

How much do you know about John Stuart Mill? Take our quiz and test your knowledge of this great British thinker.

Quiz image: Photo of John Stuart Mill by London Stereoscopic Company. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image: Tower Bridge, London. Photo by Detroit Publishing Company. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How well do you know John Stuart Mill? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Chinese contradictions and ironies, 1997 to 2017

I can’t remember when someone first asked me this, but I think it was around 1 July, 1997—a notable date as it marked the Hong Kong Handover that changed a clearly capitalist British Crown Colony into a Special Administrative Region (SAR) of the still Communist Party-run People’s Republic of China. Ever since then, whenever I have given a public talk focusing on the current state of the PRC, a question and answer session rarely ends without someone asking a variation of the “Communist or Capitalist” query. I see no reason to think I’ll stop being asked the question anytime soon. There will, after all, always seem something contradictory about leaders who claim to take inspiration from Marx and Mao running a place with a growing gap between rich and poor and cities with McDonald’s, megamalls, and multiplexes.

Lately, though, I’ve begun to notice a new “how can China be considered X, when it is Y” question starting to vie for that old one for supremacy. This one has to do not with China becoming a land where the elite can buy Lamborghinis and Louis Vuitton bags—as well as knock-offs of both sorts of luxury items—but with whether the main thing about Xi Jinping’s China is that it is becoming more and more outward looking and enmeshed with global structures, or that it is turning inward and closing itself off from international flows.

How could Xi claim at Davos to be a champion of globalization, people now want to know, when the Party he heads tightly controls the Internet and voices concern about Western ideas exerting influence on campuses? Questioners who know enough about Hong Kong to be worried, as I am, about the disturbing ways that Beijing has been ratcheting up pressure on dissenting voices and liberalizing forces there, sometimes bring up that urban center. Why, they ask, would a leader seeking to “globalize” and “open up” China try to rein and tamp down civil society in the PRC city that is most globalized and open to the world?

Before getting to how I address this globalization-related “how can China be X when it is Y” question, I should explain how I’ve handled the earlier Communism vs. Capitalism one. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, I typically framed my response around the need to get beyond Cold War binaries and simply consider the PRC a hybrid place. We were conditioned before 1989 to think in terms of a clear divide between two kinds of settings: on the one side, there were consumerist countries, on the other, Leninist lands ruled by people who emphasized the evils of Western imperialism and governed through tightly disciplined Communist Party structures. We simply need to accept, I would say, that the PRC is now both of these things at once. Curiously, it is run by a Communist Party whose ranks include entrepreneurs, and for a time, around the turn of the century, it even had a “Red Army” (the PLA) that operated hotels on the side as a profit-making venture.

I haven’t abandoned this way of answering the question, but I’ve begun to feel that in the past I sometimes put too little stress on the relationship between the X and Y involved. I now emphasize that it is in part because of its moves toward capitalism that the Chinese Communist Party has been able to stay on top in China so long after comparable organizations in Central and Eastern Europe tumbled. This certainly isn’t the only variable that matters. Nationalism is also part of the mix: one reason Communist Party rule persists in China, as well as some other places, such as Cuba and Vietnam, is because it trades on the ides that it once played a central role in a patriotic upheaval. And there is one important case in which a tilt toward consumerism hasn’t contributed at all to Communist Party longevity: North Korea.

Still, it is not just that China happened to get KFCs, karaoke bars, and later Porsche showrooms and Shanghai Disney while still having a Communist Party in charge, but that the arrival of the former things has helped keep the latter organization on top. One cause of discontent in various parts of the former Soviet bloc before 1989 was a widespread sense that the ruling groups there were unable, literally, to deliver the goods in material terms and that life was dull and lacking in diversion. People knew that not only were political choices much more limited in, say, East Berlin as opposed to West Berlin and Budapest as opposed to Brussels, but so were choices at the grocery, the department stores, and on television. Even while the political choice differences between Taipei and Beijing got much wider after the 1980s, thanks to Taiwan’s democratization and the PRC’s lack of it, the consumer and entertainment choice differences between the live led in the two cities narrowed dramatically—and this has helped the CCP endure.

Still, it is not just that China happened to get KFCs, karaoke bars, and later Porsche showrooms and Shanghai Disney while still having a Communist Party in charge

A similar kind of approach might be best to take with the newer X and Y question. At one level, when Xi alternates between championing globalization and moving to make China more closed off from certain sorts of international flows, he is just showing that, like many world leaders, he is capable of doing contradictory things and sending contradictory messages. There is, though, something else to be reckoned with as well. It is partly because of the degree to which China has become more enmeshed in international structures, a more central player in economic globalization, and more entwined with various countries that Xi feels able to make some of the moves he has to close China off. Nowhere is this clearer than in the case of the effort to make Hong Kong more like other mainland cities, the promise that it could largely go its own way for half-a-century after 1997 notwithstanding.

One thing that protected Hong Kong during the first decade or so following the Handover was that Beijing depended on it to serve as an economic intermediary between the mainland and the worlds of international business and finance. CCP leaders might have secretly wished that Hong Kong publishers would stop issuing books about the dark side of mainland politics and that its press would adhere to official lines, but taking a relatively soft line on those kinds of things seemed a small price to pay for the business-related benefits that came from having it as an SAR of the PRC rather than a Crown Colony.

Now, with the twentieth anniversary of the Handover nearing, we have been seeing more and more examples of kid gloves being replaced by an iron fist in Beijing’s approach to Hong Kong. The SAR remains a freer and internationally connected city than any other in the PRC, as I am reminded of every time I log onto the Internet there and find that I can visit all sorts of websites that are blocked when I go online on the mainland without using a Great Firewall jumping VPN. Many ominous things, though, have been happening. In 2015 and 2016, for example, several booksellers associated with a publishing house known for issuing gossipy works about the private lives of Communist Party leaders began disappearing in mysterious ways. Earlier this year, the authorities in Thailand, presumably responding to pressure from Beijing, blocked Umbrella Movement leader Joshua Wong from entering their country when he tried to come into Bangkok to give an invited speech. Then, most recently, other protest leaders involved in 2014 civil disobedience actions were charged with several year old alleged crimes just one day after the latest pro-Beijing Chief Executive was selected, via an “election” in which only a tiny fraction of the local populace could vote.

There are many variables involved in Beijing’s tightening of the screws on Hong Kong, but one thing making it easier for current CCP leaders to this than it would have been for their predecessors is how China’s global position has changed. The increasing importance of the Shanghai Stock Market and China’s central role in the new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, to cite just two recent developments, have decreased Beijing’s dependency on Hong Kong as a connecting hub. The international climate is one in which—thanks to (among many other things) Washington’s declining moral prestige and the current American administration focus on issues other than human rights where China is concerned—Xi can be less concerned about Western pushback being triggered by moves against Hong Kong civil society as the twentieth anniversary of the Handover approaches than Hu Jintao was when the tenth anniversary came and went. Chinese enmeshment in development projects in neighboring countries plays a role in things like Joshua Wong being prevented from speaking in Thailand—notably also a country from which one of the missing booksellers disappeared.

In short, just as it is partly because of moves toward capitalism that Chinese is still run by a Communist Party, it is partly because of China going global in some ways that its most globalized city is suffering. This is an era when it is important to be mindful of not only the contradictions at play in China now, but also to the dark ironies that can come from the country’s ability to be both X and Y at the same time.

Featured image credit: Hong Kong Island Skyline 201108, by kudumomo. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Chinese contradictions and ironies, 1997 to 2017 appeared first on OUPblog.

April 26, 2017

Life lessons from Shakespeare and Marcus Aurelius

William Shakespeare and Marcus Aurelius (the great stoic philosopher and emperor) have more in common than you might think. They share a recorded birth-date, with Shakespeare baptized on 26 April 1564, and Marcus Aurelius born on 26 April 161 (Shakespeare’s actual birth date remains unknown, although he was baptised on 26 April 1564. His birth is traditionally observed and celebrated on 23 April, Saint George’s Day). But aside from their birth month (and a gap of over a thousand years), what links these two venerated writers? Shakespeare’s plays are a famed source of creative and dramatic inspiration, but are also mined for their astoundingly insightful commentary on human nature. In a similar fashion, Marcus Aurelius is best remembered for his Meditations, a set of pithy aphorisms on Stoic philosophy and guidance on life.

We’ve delved into Shakespeare’s plays and the contemplations of Marcus Aurelius, to bring you six enduring life lessons. Tired of the worries of modern living, social pressures, or concerned you’re not following your true purpose? Then read on, help is at hand…

1. Live in the present

“Remind yourself that it is not the future or what has passed that afflicts you, but always the present” (Book 8, 36).

In this important meditation, Marcus Aurelius reminds us that we can’t change what’s already happened, and are equally incapable of predicting the future. It’s a method of avoiding unnecessary distress caused by “picturing your life as a whole,” assembling the “varied troubles which have come to you in the past and will come again in the future.” Paulina, the faithful friend of Queen Hermione in The Winter’s Tale would certainly agree with this. In true Stoic fashion, she apologizes for condemning King Leontes, whose insane jealousy caused the death of their beloved Queen: “What’s gone and what’s past help should be past grief” (The Winter’s Tale, 3.2).

“Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus’” from the Louvre Museum, photographed by Marie-Lan Nguyen. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus’” from the Louvre Museum, photographed by Marie-Lan Nguyen. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.2. It’s all in your attitude

“All disturbances arise solely from the opinions within us” (Book 4, 3).

It is a key tenet of Stoic philosophy that external situations aren’t important, but it’s how you react to them. If someone has insulted you, instead of giving in to destructive emotions, rely on rationality and inner calm. Likewise, Othello agrees that if a wronged person can take his losses with grace, then he will be all the richer for it: “The robbed that smiles steals something from the thief” (Othello, 1.3).

3. Live each day as if it were your last

Perhaps unsurprisingly, for both Shakespeare and Marcus Aurelius, death was a common feature of everyday life. They both return to the theme of the transience of human existence, and the relatively short time we’re given as “players” on the earthly stage. As life can end at any moment, we should make the most of it, and live each day:

“As if you had died and your life had extended only to this present moment, use the surplus that is left to you to live from this time onward according to nature” (Book 7, 56).

“I wasted time, and now doth time waste me” (Richard II, 5.5).

4. Be good to others

Given the limited time available, what should we be doing? Marcus Aurelius is very clear on this, stating multiple times that our purpose as social, rational creatures is to help our fellow humans: “Refer your action to no other end than the common good” (Book 12, 20).

Concurrently, the characters advocating goodness, mercy, and love are rife throughout the Shakespearean canon.This is perhaps most aptly summarized by the Countess in All’s Well That Ends Well: “Love all, trust a few, do wrong to none” (All’s Well That Ends Well, 1.1).

“Shakespeare, Poet” by WikiImages. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

“Shakespeare, Poet” by WikiImages. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.5. Be true to yourself

Marcus Aurelius states that the only real tragedy is not being true to yourself. What others think of you is of no importance, but how you act and how you think are the only things of intrinsic value. He ponders on the significance of adversity: “If something does not make a person worse in himself, neither does it make his life worse, nor does it harm him without or within” (Book 4, 8).

Shakespeare’s characters are no strangers to this maxim. Indeed, Othello reminds Cassio that external praise (which is easily won or lost) is of little significance—it’s his own judgement that matters: “Reputation is an idle and most false imposition, oft got without merit and lost without deserving. You have lost no reputation at all unless you repute yourself such a loser” (Othello, 2.3).

6. Less is more

Shakespeare and Marcus Aurelius are of one mind when it comes to the age old saying that “less is more.” We should focus on doing one thing well and thoughtfully, rather than rushing many things at once: “Do little, if you want contentment of mind” (Book 4, 24).

And as Friar Laurence fatedly chides Romeo: “Wisely and slow, they stumble that run fast” (Romeo and Juliet, 2.2).

Can you think of any more Shakespearean Stoicism that we’ve missed?

Featured image credit: “The Storm, Shakespeare” by chaos07. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post Life lessons from Shakespeare and Marcus Aurelius appeared first on OUPblog.

Sleeveless errand

The phrase is outdated, rare, even moribund. Those who use it do so to amuse themselves or to parade their antiquarian tastes. However, it is not quite dead, for it sometimes occurs in books published at the end of the nineteenth century. A sleeveless errand is a fool’s errand, a fruitless endeavor. Alive or expiring, for an etymologist this idiom is extremely interesting. Though both words in it are clear, no one knows who went on errands without sleeves and failed. People began to speak about such errands at the end of the sixteenth century, continued to do so for a hundred years, and then stopped. Shakespeare loved this idiom, for in Troilus and Cressida he plays with it like a cat with a desperate mouse (sleeve, sleeve, sleeve, sleeveless errand). Curiously, the origin of the phrase was obscure even very long ago, for the earliest dictionaries had no clue to its derivation or offered fanciful guesses. Perhaps, they said, –less should not have been added to sleeve, for not sleeve but Danish sløv “blunt” is the word’s root. Or perhaps sleeveless is a “corruption” of thieveless (another most suspicious word!). This is unmitigated nonsense.

A most important fact has been adduced by Skeat, who cited the earliest uses of sleeveless. In his examples, sleeveless modified reson and words. He assumed that the epithet had originally meant “useless, inefficient” and had nothing to do with errand. He was right, and the OED confirmed his findings. Already in 1386 it was possible to use sleeveless as a synonym of vain. That this adjective survived, though for a short time, only in connection with errand is puzzling but less puzzling than why such a word, obviously meaning “without sleeves,” acquired the sense “useless.” What was there that could not be carried out efficiently in a garment devoid of sleeves?

The idea, popularized by Ebenezer Cobham Brewer, that sleeveless is really sleaveless has nothing to recommend it. The word sleave exists. It means “to divide, split silk into filaments.” The noun sleave “silk in filaments” also had some currency but is now remembered, if at all, only as an echo of Macbeth (II, 2: 37): “Slepe that knits vp the rauel’d Sleeue of Care.” It can be seen that in spelling, the difference between sleeve and sleave was not always observed, which should not cause surprise, for by Shakespeare’s days, open and closed long e (ē), whose existence in Middle English can be guessed from the shape of such modern forms as see and sea, had merged. An author, writing in 1855, that is, much earlier than Brewer, explained sleeveless so: “I suspect that the word sleeve was anciently applicable to the coarse separated portions of wool or flax, as well as of silk, which was thrown aside as refuse that could not be divided into threads or unraveled by passing it through the slay of the weaver, or the combo of the wool-worker or flax-spinner, and hence sleeveless, useless, profitless like a sleeveless errand.”

Here I should risk repeating the commonsense maxim by which I abide and which I advise all historical linguists to follow: “Very clever, elaborate etymologies tend to be wrong.” The riddle before the explrer is hard, but the solution is usually simple.” Most probably, sleeveless has always meant “without sleeves.” Hard facts show that, though only the phrase sleeveless errand has survived, there is no need to harp on it, for words, rhymes, tales, and reason could also be sleeveless, some of them quite early.

Two sources of sleeveless have been suggested. One refers to the history of clothes. Sleeves could be used as pockets, while pockets, as we know them, became a standard part of our apparel only in late seventeenth century. The word pocket tells its origin, for a pocket is a small poke (bag), the selfsame poke in which we sometimes buy a pig. By contrast, sleeves have existed for a long time and were used for concealing all kinds of objects, valuables and money among them. That is why one can still have a card or a trick up one’s sleeve. The conjecture, as it was formulated in 1887 by a correspondent to Notes and Queries, is preceded by many examples of “conmen” stealing things from sleeves. His suggestion runs as follows: “Is it not then evident that ‘a sleeveless errand’ is a bootless or useless errand, one for which the errand-monger received no guerdon, no remuneration, or, metaphorically speaking, no satisfactions? Once the word ‘sleeveless’ had this signification attached to it, it was naturally used as a synonym for useless or futile.” As we have seen, the story did not begin with sleeveless errand; other things were known to be sleeveless. Why, let us repeat, was it bad to go about without sleeves?

Caravaggio’s “Cardsharps.” One of the players certainly has a trick up his sleeve.

Caravaggio’s “Cardsharps.” One of the players certainly has a trick up his sleeve.A different hypothesis has been buried in Anthenæum for August 15, 1903. (May I note that those recondite publications are no longer hidden from researchers? They are listed in my Bibliography of English Etymology.) One can read in Mabinogion, a collection of medieval Welsh tales, mythological, epic, and romantic: “Now this was the guise in which the messengers journeyed; one sleeve was on the cap of each of them in front, as sign that they were messengers, in order that through what hostile land soever they might pass no harm might be done them.” (At present, one can use a more recent translation.) The author concludes: “A sleeveless errand then would be useless, because easily prevented by the death or imprisonment of the messenger.” Here we run into the same problem as before: an attempt to derive all cases of sleeveless from sleeveless errand.

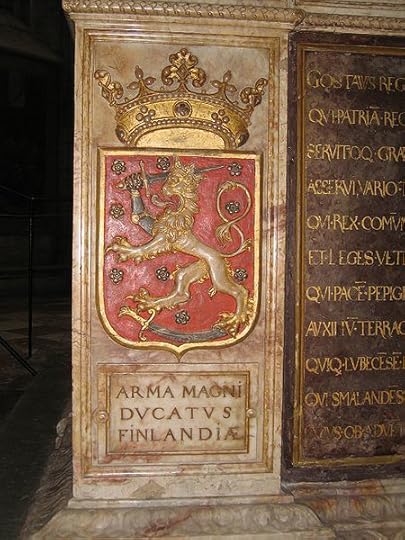

Yet there must have been some action or custom that required a sleeve without which the performance was doomed to failure, and the reference to Mabinogion may be of some use. I would like to mention a scene form Wolfram’s Parzival (an early thirteenth-century romance), which is a free translation from Old French. The great knight Gawan is ready for battle. The younger daughter of his host, Obilot, falls in love with Gawan at first sight. She is a child, perhaps six years old. Yet she knows all the rules of chivalry and asks Gawan to become her knight-servitor. Gawan, graciousness itself, agrees. But she has to present him with a ceremonial gift, so they took “…a brocade of Nourient imported from distant heathendom. It had touched her right arm but had not been sewn to her gown, not a thread had been twisted for it. This sleeve Clauditte [Obilot’s playmate] took to handsome Gawan, and at the sight of it his cares vanished away! Choosing one of his three shields he nailed it on at once. No longer did he despond.” The scene after the glorious battle: “Gawan now removed the Sleeve from his shield most carefully, lest he tear it.”

This is a shield with a sleeve on it, even though it is not Obilot’s

This is a shield with a sleeve on it, even though it is not Obilot’sCould it not be that sleeveless is a reminder of chivalric ceremonies, that knights who did not wear their ladies’ sleeves or some sleeves on their shields had no hope to succeed in tournaments and war? After all, the word is early enough. So many of our idioms come from sports (the race is too close to call and dozens of others), and chivalry dominated medieval life for such a long period of time that an echo from its language in popular usage is not improbable. But of course, there is no evidence. What results could we expect from exploring the origin and nature of a sleeveless errand? Perhaps some friendly Obilot among our readers will offer a more persuasive conjecture to the joy of all present.

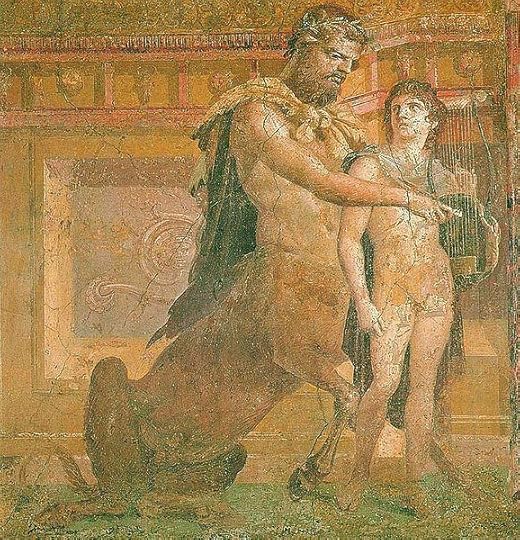

Chiron taking care of Zeus. Not many sleeves, but who would call the centaur’s task a sleeveless errand!

Chiron taking care of Zeus. Not many sleeves, but who would call the centaur’s task a sleeveless errand!Image credits: (1) “Portrait of Agnolo Doni” by Raphael, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) “The Cardsharps” by Caravaggio, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) “Coat of Arms of Finland” photograph by Grimne, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (4) “Chiron instructs young Achilles – Ancient Roman fresco” by Herculaneum, Augusteum (cd. Basilica), Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Featured image: “The joust between the Lord of the Tournament and the Knight of the Red Rose” by Hodgson, Public Domain via .

The post Sleeveless errand appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers