Oxford University Press's Blog, page 366

May 17, 2017

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow on birds, poetry, and immigration

On 26 February this year, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, the most popular poet America has ever had, turned 210. The lines from Longfellow everyone remembers, often without knowing who actually wrote them (“into each life a little rain must fall”; “Let us, then, be up and doing”; “Each thing in its place is best”), point to an author who wanted to help us live our lives, not exactly change them. Longfellow was, by critical consensus, not a political poet. A famous double portrait shows Longfellow seated next to his friend, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, exemplifying, as the caption stated, two separate realms, the “Poetry and Politics of New England.”

And yet, that’s precisely the point: Longfellow was friends with Sumner, one of the most outspoken politicians of this time, a fierce opponent of slavery and advocate for civil rights. Some of Longfellow’s most touching poems are tributes to Sumner, a man he admired and loved and, occasion, teased. In a hilarious episode recounted in one of Longfellow’s journals, Sumner had come for a visit at Craigie House, Longfellow’s residence in Cambridge. After dinner, they went for a walk in the garden, where the enthusiastic Sumner, more at home in the chambers of the Senate than the fields of Cambridge, spied a tethered calf. He enthusiastically approached the animal and grabbed the rope around its neck: “Come here! Come here!” Things happened very fast then: the calf jumped, the rope swept through the grass, and Longfellow saw a “brief glimmer of gray gaiters high in air, and prone lies the philanthropist in the sod.” The Longfellows laughed, but Sumner, rising bedraggled from the dirt, was not amused: “When a friend meets with an accident you ought to laugh at him; you ought to pity and sympathize with him!”

Portrait of Senator Charles Sumner and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow by Alexander Gardner (1821–1882), Library of Congress. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Senator Charles Sumner and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow by Alexander Gardner (1821–1882), Library of Congress. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Longfellow’s Cambridge was still stubbornly rural. Gazing out his study window, past old trees, Longfellow would see the boats pass by on the Charles River, a shimmering band of water wending its silvery way through the lush meadows. In 1868, when a group of butchers from Brighton got together to plan the construction of a large slaughterhouse on the other bank of the Charles, Longfellow sprang into action and collected enough money from friends, relatives, and neighbors to buy the land. He gave it to Harvard University, asking that it be kept open for the free enjoyment of the public. By 1898, the Brighton Meadows had become the Charles River Speedway, used for horse and bicycle races.

Longfellow kept careful track of the changes in his environment. In one of his most prescient and, yes, political poems, “The Birds of Killingworth” (1863), a poem so outspoken that it would have made Sumner proud, he imagined what nature would be like if all the birds were gone. In Longfellow’s clever fable, the citizens of the fictitious New England town of Killingworth decide to rid their fields of all marauding birds. Profit is not the only motive at play. The Parson, for example, simply loves to kill: “His favorite pastime was to slay the deer / In summer on some Adirondack hill.” The pompous Squire is too full of himself to think about the consequences of his actions, while the ponderous Deacon is so proud of his ability to forecast the future that he’s not worried about inaction in the present. At a quickly convened town hall meeting, the only one willing to defend the birds is the local schoolteacher. “You slay them all! And wherefore?” The dismal vision that he paints for his listeners anticipates the dystopian story that opens Rachel Carson’s famous bestseller Silent Spring (1962): “Think of your woods and orchards without birds! / Of empty nests that cling to boughs and beams.” But he doesn’t convince anyone, and the “ceaseless fusillade of terror” commences, “a slaughter to be told in groans, not words.”

What is left is an ecological disaster site. The grounds have turned ashen, caterpillars rule the garden beds, and the beetles, with no one to keep them in check, have seized the farmers’ fields. Come spring, the anxious citizens of Killingworth have begun re-importing birds from elsewhere. At the end of the poem, the birds sing again, but to the experienced ear it seems as if they were mocking the people.

Longfellow’s poem tells a familiar story—unfettered greed taking precedence over ecological wisdom, with funds then lavished sheepishly on schemes that are intended to undo, however imperfectly, what should never have happened in the first place. The residents of Killingworth can still fix, sort of, what they foolishly destroyed. Today our chances to do the same diminish with each passing year. But Longfellow’s poem is more than a cautionary tale about environmental destruction. He was a poet, and it is no coincidence that he describes the assault on the birds of Killingworth, those troubadours of the treetops chanting their “madrigals of love,” as an attempt to do away with literature or, more generally, with everything that makes our lives beautiful and livable.

But there’s yet another level to Longfellow’s critique, which makes this old poem so chillingly modern. For so many of the birds that come to Killingworth each spring are visitors from far away, birds of passage, “speaking some unknown language strange and sweet.” They are foreigners, greeting us with welcome news from abroad. They are, Longfellow tells us, essential to our spiritual as well as material survival. Longfellow, who spoke ten languages fluently and read at least a dozen more, was famously hospitable to every foreigner who showed up at his house, from German revolutionaries and Italian nationalists to Cuban poets. He once joked that he was everyone’s “oncle d’Amérique.” But he in fact relished that role, and his quip masked a serious concern: that any limits imposed on immigration would limit and, indeed, kill the exciting linguistic and cultural variety that had made his native country so wonderfully exciting and, yes, worth living in.

Featured image credit: Drawing of Longfellow by William Edgar Marshall, c. 1881. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Henry Wadsworth Longfellow on birds, poetry, and immigration appeared first on OUPblog.

A decalogue of moments in America’s history with the Ten Commandments

Although we are told that Moses received the Ten Commandments at Mount Sinai, their presence has always been particularly strong in America. Regardless of who invokes them and for what purpose, the Ten Commandments have proved to be incredibly versatile and enduring in our cultural idiom. Below you’ll find ten moments in American history where the Decalogue has made its presence felt.

1. In June 1860, a man in Ohio named David Wyrick found an oddly shaped stone in one of the many Native American burial sites in the area which had indecipherable markings on it. He claimed to have found one of the stone tablets that God had bestowed upon Moses. Largely ridiculed at first, he then discovered another stone, shaped like the top of a church window which was covered in what was later confirmed as a variant of Hebrew script. When brought to experts the script did indeed feature a form of the Ten Commandments, abbreviated, but still the basic text. Was it authentic or an elaborate hoax? You can go to the Johnson-Humrickhouse Museum in Coschocton, Ohio to see the stones for yourself.

2. In 1897, Alabama Senator John Tyler Morgan proposed that all immigrants be given a test to display mastery of the Ten Commandments in order to gain American citizenship. He claimed that it was not a religious test but rather a “test that goes to the constitution of society.”

3. In 1905, the Congregation Sherith Israel in San Francisco revealed the stain glass window of its newly constructed synagogue. At first glance, the window seemed to depict a traditional scene of Moses descending from Mount Sinai with the stone tablets in his hand. Closer examination, however, revealed that the mountain in the background was not Mount Sinai, nor were the flora and fauna that of Israel. Rather, El Capitan of the Yosemite Valley loomed in the background, complete with the plant and animal life of central California, refiguring the Golden State as the Promised Land.

4. In 1921, the Chicago Tribune’s “Inquiring Reporter” asked people on the street if they could recite the Ten Commandments. Most could not. One man, G.H. Moy, a railroad employee, claimed as a boy he could “recite them backwards,” but with the passing of enough time, he “just naturally forgot them.”

The Ten Commandments by Breve Storia del Cinema. CC-by-2.0 via Flickr.

The Ten Commandments by Breve Storia del Cinema. CC-by-2.0 via Flickr.5. The original 1923 Cecil B. DeMille film The Ten Commandments cost $1.5 million dollars to make (around $21.3 million dollars today) and utilized the largest set ever built at the time in the desert of Guadalupe, California. The cast numbered in the thousands, plus some three thousand animals, including camels, horses, mules, goats, and guinea hens. The parting of the Red Sea scene was filmed in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, and was a source of awe for all who saw it. Regarding the scene where Moses receives the Ten Commandments, The New York Times wrote, “There has been nothing on film so utterly impressive as the thundering and belching forth of one commandment after another.”

6. In the early to mid-1950s, Cecil B. DeMille enlisted the Fraternal Order of Eagles to help in the production of life-size stone tablets to be placed in cities around the country. The goal was two-pronged: to spread the message of the Ten Commandments in alignment with the history of the Eagles’ tradition of do-gooding and also to promote DeMille’s soon to be released film. For Judge E.J. Ruegemer, a Minnesotoan and Eagle, who had successfully pushed for paper versions of the Ten Commandments to be posted in juvenile courts throughout America, DeMille had a copy of the Ten Commandments carved out of the red granite of Mount Sinai itself.

7. The remake and expansion of The Ten Commandments cost $13.5 million dollars to make and was filmed on location in Egypt and Mt. Sinai, outdoing its own initial extravagance, and debuted to unanimous praise in 1956. In interviews, DeMille frequently claimed that The Ten Commandments was “as modern as this morning’s newspaper” and that one reason for the films massive success was because it was a testament to the power of democracy and the imperatives of brotherhood. Historically speaking, the film’s subject matter, although ancient, was utilized at a time when America needed a lodestone to unite itself internally and differentiate itself from the other postwar (and Godless) hegemon, the USSR.

8. In 1963, during the Birmingham demonstrations, Martin Luther King, Jr. required every participant, ranging from the demonstrators to those working the phones, to sign a pledge of nonviolence modeled on the Ten Commandments. For example, “WALK AND TALK in the manner of love, for God is love. SEEK to perform regular service for others and for the world. FOLLOW the directions of the movement and of the caption on a demonstration.”

9. Laura Schlessinger’s 1998 bestseller, The Ten Commandments: The Significance of God’s Laws in Everyday Life, co-written with Rabbi Stewart Vogel, took the format and traditional basis of the Ten Commandments and mixed them with pop psychology and self-help panache to repackage the Decalogue for contemporary life. Featuring catchphrases like “Have you hugged your kids lately?,” “Adultery: just say no,” and “Time-out!,” the original brevity and list format of the Decalogue have made it particularly conducive to the sorts of quick and punchy phrases that continue to thrive under the reign of advertising and the commercialization of everyday life.

10. In 2005, the Supreme Court heard two cases relating to the display of the Ten Commandments and its relationship to the Establishment Clause of the 1st Amendment. The court ruled in favor of removing the Decalogue from two county courthouses in Kentucky, but then ruled against removing a stone display on the grounds of the Texas state capitol building. The rationale of the court was based in a distinction between active and passive displays. The association of the Kentucky courts with the Decalogue “actively” promoted its role in the government, whereas the display on the grounds of the capitol building “passively” recognized the role that the Ten Commandments have played in the history of America.

All material has been derived and adapted from Set in Stone: America’s Embrace of the Ten Commandments by Jenna Weissman Joselit .

Featured image credit: Tablet with ten commandments, Civic Center Park, Denver, Colorado, USA by Daderot. CC0 public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A decalogue of moments in America’s history with the Ten Commandments appeared first on OUPblog.

May 16, 2017

What the WannaCry attack means for all of us

As the aftershocks of last week’s big “WannaCry” cyberattack reverberate, it’s worth taking a moment to think about what it all means.

First, ransomware is a growing menace, and this may be the case that gets it global attention. The idea behind ransomware is simple: no one is willing to pay as much as you for your data. Instead of copying critical data and trying to sell it to others, ransomware authors will simply deny their target access until payment is made. Documents or medical records might not have much resale value, but if a hospital needs them to operate, suddenly they become very valuable. With data decryption usually priced in the hundreds of dollars, many organizations find it easier to pay and move on; the leading cybersecurity firm Trend Micro recently researched UK organizations who have received ransomware in the past two years and found that almost two-thirds of those it surveyed paid the ransom. Organizations that have paid include hospitals and police departments, as well as countless companies.

Second, what made the WannaCry ransomware so powerful is how quickly it spread. It took advantage of a vulnerability in a part of the Windows operating system known as Server Message Block—the same vulnerability that had been previously exploited by the United States National Security Agency and that was made public by an unknown group known as The Shadow Brokers. It appears that the WannaCry ransomware was often delivered by a social engineering email. Once it was opened, this vulnerability in Windows systems enabled the malicious code to spread quickly across an organization’s network, infecting not just one computer, but many.

Screenshot of Wana Decrypt0r 2.0 by securelist.com. Fair use via Wikimedia Commons.

Screenshot of Wana Decrypt0r 2.0 by securelist.com. Fair use via Wikimedia Commons.Pieces of malicious code that employ this self-spreading technique are called “worms.” While the cybersecurity world has seen worms before—the Stuxnet attack carried out against the Iranian nuclear program is probably the most famous—WannaCry quickly became the most significant piece of “wormable” ransomware to exist. It probably won’t be the last.

Third, and perhaps more important: like the emperor’s new clothes, even this new-fangled ransomware isn’t as sophisticated as it’s cracked up to be. Most ransomware attacks can be prevented by good cybersecurity practices. In this case, the Server Message Block vulnerability in Windows that WannaCry exploited had been fixed by Microsoft before the details became public and before the WannaCry code was written. Anyone who applied the March security update to Windows didn’t have any trouble with WannaCry. Most fortunate of all, the authors of WannaCry seemed to make a fairly basic mistake that bought network defenders critical hours. When a security researcher—who remains anonymous and goes by the pseudonym MalwareTech—registered a domain name to which the malicious code was attempting to connect, he rendered the code inert. This likely spared thousands of people from having their data locked away.

There is a clear lesson for all of us from this incident: cybersecurity can be hard, complex, time-consuming, and expensive—but not impossible, especially against comparatively unsophisticated criminals. There is never a silver bullet solution, but there are a lot of small things that can go a long way. For organizations and individuals, chief among these is making sure that the software they run is kept up to date. Patching is often harder than it sounds, but it is a task that deserves significant attention by network defenders. In systems that aren’t easily patched—such as some medical devices—network defenders should take care to make sure those systems aren’t easily accessible. In an era of wormable ransomware, it’s too dangerous to have any one computer be an entry point to the entire network and a single point of failure. If that lesson wasn’t clear before, perhaps this past week will be a much-needed wake up call.

Featured image credit: Cyber Security by typographyimages. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post What the WannaCry attack means for all of us appeared first on OUPblog.

Student debt: not just a millennial problem

When I was interviewed on the Kathleen Dunn Show, I was prepared to talk about the health implications of educational debt for students. That changed when a father called in and shared his story about helping his children pay for college. This father wanted to protect his children from debt and was trying to do the “right” thing by his children, and it almost resulted in the loss of his home. At that moment, I realized we – myself, the media, policy makers – were thinking too narrowly about who is affected by student debt.

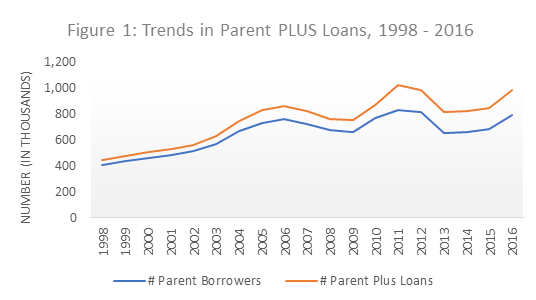

It soon became clear that parents had been ignored in discussions about student debt because there was little data about their experiences helping their children pay for college. While we had some indication that more parents today were borrowing to pay for their children’s college education than in the past (see Figure 1), we still did not know which parents were more likely to borrow. I, along with my colleague, Jennifer Ailshire, set out to answer this question.

Figure 1 by Katrina Walsemann. Used with permission.

Figure 1 by Katrina Walsemann. Used with permission.We found that among mid-life parents of college-aged children, 13% borrowed to help their child(ren) attend college. These parent borrowers, on average, borrowed about $21,000.

A number of factors were associated with whether parents borrowed or not. Some of these were expected; for instance, parents who had 2 or more college-aged children were more likely to borrow than parents with just 1 college-aged child. We also found that parents with at least a high school diploma and who earned more income were more likely to borrow than parents with less than a high school diploma or who were making less than $30,000 a year. At first glance, these may seem like less than intuitive findings – why would parents making more money borrow to pay for college? Two possibilities come readily to mind. First, higher SES children may attend more selective universities that require greater financial investment than lower SES children. We were unable to examine this directly because information on institutional characteristics was unavailable, however. Second, compared to lower SES parents, higher SES parents could be in a better financial position to borrow as a way to help their children avoid taking on student debt. For example, the Parent PLUS loans program will not lend to a parent who has an adverse credit history, which includes events such as foreclosure, bankruptcy, wage garnishment, tax liens, or being delinquent on loans or credit cards.

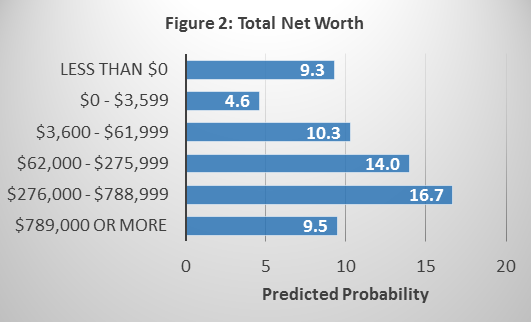

The pattern for household wealth, on the other hand, suggested that the wealthiest parents were no more likely than the least wealthy parents to borrow. Rather, it was the parents in the middle of the wealth distribution who were the most likely to borrow (see Figure 2). Because our measure of wealth included home equity, it may be that these parents had to rely on loans to help their children pay for college because they did not have ready access to their home equity, but felt financially secure enough to borrow because of the home equity.

Figure 2 by Katrina Walsemann. Used with permission.

Figure 2 by Katrina Walsemann. Used with permission.Fewer factors predicted how much parents borrowed, but household income over $120,000 (compared to less than $30,000) and having 2 college-aged children versus only 1 were associated with borrowing more.

As college tuition continues to rise and state investment in higher education declines, more students will rely on loans to finance their education. Since undergraduate students can borrow a maximum of $31,000 in federal loans, universities may increasingly look upon parents to cover the remaining cost of college. As a result, more and more parents will have to decide if they are in a position to borrow to pay for their children’s college tuition. Some parents will not be adversely affected if they decide to borrow, but other parents will have to make trade-offs between saving for retirement and servicing their student debt. This is concerning because 50% of midlife adults have saved $12,000 or less for retirement. What is more, student debt typically cannot be discharged, even in standard bankruptcy filings. As a result, student debt has the potential to increase financial stress and negatively impact physical and mental health and well-being, particularly among those parents who financially struggle to repay the debt.

In the end, parents should carefully consider if borrowing to pay for their children’s college is the right decision to make given their financial situation. Policy makers should recognize the importance of including parents in policy discussions around student debt, and must pay attention to the tradeoffs that parents often make because of it.

Featured image credit: university education school by TeroVesalainen. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Student debt: not just a millennial problem appeared first on OUPblog.

Learning to read emotions in oral history

The most recent issue of the OHR featured two stories on understanding emotion in oral history interviews. In one piece, Julian Simpson and Stephanie Snow asked what role humor plays in healthcare, and how to locate it in oral history. In another piece, Katie Holmes asks how to locate historical emotion during an interview and how to interpret these feelings. Today on the blog we bring you a short interview with Holmes where we ask about her interest in studying emotions, explore the experience of listening for emotion, and hear more about how she uses this investigation in her historical analysis. Enjoy the interview below, and check out the full piece in the OHR 44.1.

What prompted your interest in reading emotion in oral histories?

Many of us have had the experience of interviewing someone who can become quite unexpectedly distressed or “emotional” during an interview and it’s not always clear what is going on for them. I’d conducted a number of interviews for the Australian Generations project where this had happened, or where the interview had dealt with some highly emotional memories, including one where the participant seemed to spend much of the time in tears but seemed quite happy to keep recording. I was struck in my interviews by the different ways in which different generations responded to their emotional distress. Older interviewees usually wanted to turn the recorder off whereas younger ones seemed happy to emote all over the place! This in itself suggested different ways in which emotions had been “managed” historically. So I started to read more of the history of emotions literature, very little of which dealt with oral history or memory and emotions. That which did seemed very inadequate, and dismissive of the idea that the expression of emotion in an interview–and I guess I’m talking here about painful emotions rather than joyful ones–could really tell us anything about past emotion. This seemed quite contrary to the albeit limited psychoanalytic understanding that I had, and so I wanted to explore it further.

You invite oral historians to try to locate “historical emotion” by paying attention both to the content and the context of the interview–the bodily movements, setting, and even your own emotional state. Can you talk more about what this looks like in practice?

It means being very attentive to the non-verbal clues that your interviewee gives. So you need to listen beyond the words and pick up on what else is happening. It’s like operating on a number of different channels. There’s the information that the interviewee is sharing with you, then there’s the non-verbal communication that is going on–how they are sitting, how does that change, the pace and volume of their voice, what they are not talking about–and then there’s what you as an interviewer are feeling. This last one can be tricky but sometimes we can have quite strong reactions to our interviewees, or to the information they are sharing. What I suggest in the article is that we need to be attentive to our own responses because they can give us clues about what is happening for the interviewee. Maybe you are reminded of something or someone in your own life. Maybe you suddenly start to feel very uncomfortable or sad or want to move the narrator along when they want to linger on a topic–all these responses can be helpful in trying to work out what is going on for the interviewee and then gently asking further questions about it. So one of the channels we have to tune into is our own, and while not letting our own responses get in the way of the narrator’s recollection, use them as a possible insight into what might be happening for our interviewee. Our role is not to play therapist, but to learn as much as our interviewees are willing to share about their past life in all its complexities.

Our role is not to play therapist, but to learn as much as our interviewees are willing to share about their past life in all its complexities.

You note that you “re-experienced” some of your narrator’s trauma alongside her, as she shared her personal history. What is that experience like as an interviewer?

It can be pretty intense! And the challenge is to maintain the professional boundaries at the same time as attending to what is going on for the narrator. In the interview I discuss, I really could sense her fear and distress as she recalled a very difficult and confusing time in her childhood. Her projection of those emotions was palpable. And that’s when the listening on all channels comes in because I was suddenly struck by how young she would have been–the same age as my daughter during a very difficult time in my family–and I could see the way my daughter watched me so closely during that time. I write in the article about being pulled out of being an interviewer into being a person and a mother and, drawing on that experience, I asked a question about watching her mother. It seems like a really odd question to ask, and I asked it a bit too quickly, but at that moment I was responding from my own subjectivity.

When our interviewees are disclosing difficult or painful emotions that affect us, it’s really important that we can sit with that discomfort and not try and steer the interview away because of our need. That does mean being both aware of how we are responding and being able to manage our own emotional response. It requires a level of self-awareness and good intuition. As I said, it can be both intense and exhausting, but it can also be very satisfying and rewarding as an interviewer to feel that you’ve facilitated a rich and complex life narration.

Part of your ability to read the emotions your narrator is expressing comes from being physically in the room during the interview. How can you do similar work when listening to an interview recorded by someone else, or when there is only a transcript available?

This can be very difficult. I have listened to a number of the Australian Generations interviews where the interviewer has noted that the narrator became distressed or emotional at times, and have found it really hard to hear it. Sometimes the recorder has just suddenly been switched off, at other times you have to assume that the narrator is still talking while tears are falling, but you can’t hear those silent drops. At other times the distress is really evident–it can depend on how much the narrator is trying to control their emotional responses. Joyful emotions can be easier to hear in the tone of voice and pace of narration. For more painful emotions, you can listen for the faltering voice, the long pauses, the sniffles, but even then they can be hard to pick up and you have to listen really carefully. Visual clues tell us so much! A transcript can be even harder, unless someone has usefully annotated it to indicate changes in volume and pace, or long pauses etc. A transcript has other benefits of course and they are much easier to work with, and help you pick up the silences and the repetitions more readily. With the Australian Generations project we decided that listening to an interview and having a transcript was the best way to work with an interview. Of course you still don’t get the visual clues but if you are working with oral rather than video interview, that is the trade off.

What role does emotion play in your current projects?

Once you start getting interested in the history of emotions, you start to see them everywhere! I’m currently working on an environmental history of an area known in Victoria and South Australia as the “Mallee.” It’s pretty marginal farming country which has been a wheat and sheep growing area since Europeans first began settling it in the late 19th century. I’ve been really struck by the emotional cycles that have driven first the settlement of the area, and then the periods of drought and extreme hardship that periodically afflict it. These emotional cycles can be affected by national developments or by the invention of a new strain of wheat or a new method of sowing and harvesting, and climate plays an important role as well – periods of extended drought are remembered as times of great strain and hardship. So there are historical periods that are marked by particular emotions. Then depending on the season when you might be visiting and interviewing a farmer from the area, the emotional tone of the interview will be very different. If you are visiting in autumn and the start to the sowing season has been good, the mood will be positive and hopes high. Return in spring after the rains have failed to deliver, and it’s a completely different scenario. And then there are the emotional connections that people have for their land or the area itself, or maybe a particular paddock or place on their property. For me what is fascinating about all this is not so much that these emotional responses are there, but that they drive the decisions people make. With farmers who are farming land that has been in their family for generations, the emotional legacy of that land and history is huge and it can often shape the ways people farm, sometimes preventing them from making decisions that might be in the best economic interests of the farm. And it’s really interesting to explore the connections between personal and community emotional fluctuations. In times of optimism people behave differently and make different decisions–maybe they will buy that land next door after all because the future is looking brighter. Climate change is now influencing emotional responses as well–uncertainty about the future is now apparent in conversations, and fear about what that will mean for the Mallee area. In my next project I am planning to bring together my interests in oral history and environmental history even more directly, interviewing people about living with environmental change. I am looking forward to exploring the issues around emotion and memory more fully in that work.

Is there anything you couldn’t address in the article that you’d like to share here?

I think if anything I could have made my argument about the possibility of accessing historical emotions through oral history even more strongly, but I was being cautious. I chose not to include links to the audio of the interview in order to protect the anonymity of my narrator, but some of what I try to describe in the article in terms of the sound of her voice, its cadences and pauses etc, is even more evident when you can hear it.

I’d also reinforce my point that this kind of interviewing is hard work! It’s emotionally demanding, it requires self-reflection and knowledge, and honesty. And not every interview, or even every interview where there is a lot of emotion expressed, is going to generate the kind of transference and counter-transference that I think happened between myself and Jana. But being quietly alert to the possibility is important.

How did you feel reading this interview, or the article in the OHR? Chime into the discussion in the comments below or on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or Google+.

Featured image credit: “Headphones” by Nickolai Kashirin, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Learning to read emotions in oral history appeared first on OUPblog.

Friends with benefits?

Before Theresa May decided to go to the country, the election result many observers of UK politics were most looking forward to was the outcome of ‘super-union’ Unite’s bitter leadership contest between the incumbent, Len McCluskey, and his challenger, Gerard Coyne – a contest which, rightly or wrongly, had been viewed through the prism of its potential impact on the Labour Party.

Drawing on a newly published cross-national study of the relationship between left of centre parties and trade unions, it is possible to cast a little comparative light on what Lewis Minkin famously termed ‘the contentious alliance’. Here are nine things worth knowing about the links between centre-left parties like Labour and trade unions.

1. Links between centre-left parties and unions remain strong in some places

The British Labour Party has always been intimately bound up with trade unions: after all, as Ernie Bevin famously put it, the party ‘grew out of the bowels of the Trade Union Congress’ back at the beginning of the twentieth century. But it’s important to realise that it’s by no means unique. There are centre-left parties all over the world whose traditional ties to their respective labour movements remain pretty strong – in Australia, in the Nordic countries, in Austria and in Switzerland, for instance. What’s unusual about Labour, notwithstanding Bevin’s remark, is that the party’s relationship with the Labour movement is, formally anyway, only with individual unions rather than with an overarching congress which encompasses many constituent unions.

2. It is unusual for union leaders to become political leaders

Bevin, together with Alan Johnson, is unusual in having made the transition from powerful union leader to big-beast Labour politician. Others have tried it – most notably Frank Cousins of Unite’s forerunner, the TGWU, back in the sixties – but failed miserably, since when British union leaders have generally preferred to stick to exercising influence in the party indirectly, using their money, their guaranteed places on various party bodies, and votes on policy and candidates to push Labour in their direction.

That’s generally been the case, too, in other countries. True, Bob Hawke, who was Labour prime minister of Australia between 1983 and 1991, had also been president of the country’s Council of Trade Unions. But he was another exception proving the rule. Even in Sweden, where the relationship between the social democratic SAP and the main union congress, the LO, has traditionally been strong, the current prime minister, Stefan Löfven, is very unusual in having led a trade union before taking charge of the Social Democrats back in 2012.

3. MPs with a strong union background are in the minority – often a small one

Like Löfven, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn dropped out of university, even if, unlike Löfven, he grew up in a middle class (indeed, some would say upper-middle class) family so can hardly claim to be a horny-handed son of toil. He can claim, however, to have a pukka union background, working as an organiser for forerunners of UNISON and Amicus in the seventies before becoming an MP. In that sense (if not in many others) he’s not alone, although there has almost certainly been a decline in the number of people in the Parliamentary Labour Party with a union background.

Theresa May in 2007. By Andrew Burdett. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Theresa May in 2007. By Andrew Burdett. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.And most of those who have such a background will have been, say, researchers rather than the working class, former elected officials who, back in the fifties, sixties and seventies, provided much of the ballast on the Labour benches. These days, Shadow Secretary of State for Education, Angela Rayner, having left school at sixteen and working in social care before being elected to serve her union UNISON full-time, stands out from the crowd. Still, Labour isn’t so unusual in this respect: countries like Finland and especially Switzerland, where a fair few MPs from the main centre-left parties still have union backgrounds, are probably outliers, and even there, we’re only talking between a fifth and a quarter of them.

4. Labour’s highly-institutionalised relationship with unions is not the norm

Labour is unusual among its international counterparts in there being an organisation, TULO (The Trade Union & Labour Party Liaison Organisation), whose job it is to help coordinate and manage the link between the party and the 14 unions (with over 3 million members between them) currently affiliated to it. Moreover, outside Australia, the system of collective affiliation, seen as the norm in the UK, has either never been replicated or else has long since been abandoned in other countries.

In the US, the Democrats and the unions have never enjoyed anything like the sort of institutionalised relationship seen in the UK. And the same can be said of France and Italy, although there the absence of a stand-out, single party on the centre-left had a lot to do with it. In other places – Israel and the Netherlands, for instance – what was a fairly close relationship has all but completely collapsed or is a shadow of its former self. In Germany, where the SPD suddenly seems back in contention electorally now that Martin Schulz has become its candidate for Chancellor, things are nowhere near so bad, even if ties aren’t what they are in, say, Scandinavia or, even closer to home if you’re in Berlin, Austria and Switzerland.

5. It’s not all about money

In the UK, the unions, despite Ed Miliband abolishing the electoral college which gave them a special say in electing Labour’s leader, are still organisationally-speaking, effectively part and parcel of the party. That means that, outside Australia, they retain more influence over it than their counterparts in other countries exercise over their traditional political ally.

Clearly, the fact that UK unions, even if they gave up sponsoring individual MPs in the mid-1990s, still play a major part in bankrolling the party also makes a difference. However, we need to be careful not to assume that ties between centre-left parties and trade unions ultimately come down to cold hard cash. Organisational ties continue to persist in many countries where unions are not a significant source of finance for social democratic parties, although they do tend to be weaker in countries where state subsidies to parties are generous and in countries that heavily regulate party finance.

6. History matters – but so do the benefits

This is not to say, of course, that continuing close ties between centre-left parties and trade unions are merely a matter of sentiment. True, looking around the world it is clear, as is the case in the UK, that historical legacies matter: those parties and union movements that had the strongest links with each other in the decades following the end of World War Two still tend to have the strongest links today, both formally and informally, and whether we look at the parliamentary or the extra-parliamentary party (which in many countries outside the UK is where power lies and where the links are strongest). But that does not mean that the relationships they enjoy right now are unaffected by a belief that each partner gets something useful out of them.

7. Membership of trade unions is falling in many countries, but relationships with parties persist

This raises the question of precisely what benefits parties like Labour, as well as the unions to which they’re linked, derive from those links, beyond (for some of them anyway) financial support. Certainly, they’re not as obvious as they once were – for either side. Centre-left parties cannot fail to have noticed that trade unions’ ability to persuade their members to vote for them at elections, while it hasn’t disappeared altogether, seems to have declined, especially as cultural issues like immigration have become as (or even more) important as the economy as drivers of electoral behaviour. But even if that were not the case, unions’ ability to deliver their members as voters would be worth less to Labour since not only has the blue-collar working class declined precipitously over the decades (as it has everywhere) but far fewer people now belong to unions than they used to.

Trade union density in the UK has declined from a post-war high of just over 50% in 1979 to around 25% now. This isn’t bad compared to some countries: in Germany the figure is just under 20%, in the US just over 10%, and in France well under that. But it’s nowhere near as high as in, say, Sweden, where because unions still seem to be able to recruit pretty well in the private as well as the public sector, two-thirds of employees belong to one. Indeed, countries where more people are trade union members, as well as where the trade union movement is more concentrated, do seem to see stronger party-union links. That said, density isn’t destiny: links persist in some places despite some sizable drops in the number of people joining unions.

8. Parties often seem to benefit more than unions

What then do trade unions get out of Labour and parties like it – and how much does that determine the closeness of the relationship between the two sides? ‘Not very much’ seems to be the answer on both counts. You don’t have to swallow the radical orthodoxy that the centre-left has somehow prostrated itself before the gods of neo-liberalism to recognise that, as well as finding it more difficult of late to get itself elected to power, it doesn’t like to intervene as much in the economy or spend as freely on welfare as it used to when it does get there.

Nor is it the case, anyway, that the more left-wing, the larger, or the more likely a social democratic party is to be in government or to recommend its members join a union, the more likely it is to enjoy strong links with the unions. It is therefore difficult to avoid the conclusion that the relationship is a little lop-sided: in as much as that relationship is transactional and based on an exchange of resources, neither side gets as much out of it as it used to; but centre-left parties probably do a little better out of the deal, especially if finance and/or election volunteers are part of it, than do the unions.

9. …but the alternative for unions could be worse

But there’s a but – and one that will be familiar to anyone familiar with the UK since 2010. Comparative analysis suggests that when centre-left parties are in power, unions with weaker links to them find it harder (though, as France and Italy show, not impossible) to stop those parties trying to push through liberal reforms. On the other hand, it also suggests that the strongest of organisational links are no guarantee that social democratic governments will deliver whatever unions want.

But not getting everything they want from the centre-left is still likely to be better, as far as most trade unions are concerned, than ceding power and the initiative to the centre-right. Faute de mieux may not be a particularly inspiring reason to maintain relationships with centre-left parties, but it may explain why trade unions – particularly perhaps in two party-systems like the UK where there are no other serious options on the left – continue to invest time, effort and, as in Labour’s case, money, in maintaining them.

Featured Image Credit: Protest march for a $15/hour minimum wage at the MSP airport by Fibonacci Blue. CC 2.0 via Flickr.

With thanks to Europp for allowing us to cross-post – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics , original publisher of this article.

The post Friends with benefits? appeared first on OUPblog.

May 15, 2017

Edwin Muir and a story of Europe

While reading recently British Library correspondence files relating to the poet Edwin Muir—the 130th anniversary of whose birth will be on 15 May this year—I was struck, as I have often been, by the important part played in his development as man and poet by his contact with the life of Europe—a continent that is currently high on the agenda of many of us with a possible British Brexit in view. Orkney-born Muir first came to public attention as a contributor to The New Age magazine edited by A. R. Orage, and his first book, We Moderns (1918), initially appeared as a series of articles in the magazine. Its success was followed by an American edition in 1920 introduced by H. L. Mencken and this in turn led to his engagement as a regular contributor to the newly established American Freeman magazine. The prospect of a regular income from the Freeman gave him the courage to go adventuring in Europe—a continent of the imagination previously known to him only through books. His European travels not only led to his own development as poet but also to him bringing Europe to the English-speaking world through his translations with his wife Willa of European writers, including in 1930 the first translation into English of the German-language fiction of Franz Kafka.

Muir’s contact with Europe is significant, however, not only in a personal and literary sense, but also in a wider political context which resonates with our own early twenty-first century times. His travels in the 1920s immediately after the end of World War One, and again at the end of World War Two, tell a story of Europe itself at critical points in its history. In the 1920s, his first stop was in Prague, the capital of the new Czechoslovakia which had achieved independence as a result of the Treaty of Versailles. There he was befriended by the Čapek brothers—playwright Karel and painter Josef—who were active in the cultural life of the city. At that time, Karel was probably the best-known Czech writer internationally while through his writings and his association with Czechoslovakia’s first President T. G. Masaryk he contributed significantly to the building up of the new republic. His play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots) gave the world the word “robot” and was such a success at home and abroad that in England its popularity apparently resulted in a spate of new businesses making toy robots for sale, while in Prague children “played robots” for months after its first performances. With R.U.R. and other plays of the 1920s such as From the Life of the Insects and The Makropolous Case, Čapek anticipated Huxley’s dystopian Brave New World of 1932 and Orwell’s Animal Farm and 1984 published in 1945 and 1949. But while all these works to some extent grew out of fears and uncertainties in a century in which advances in science and technology as well as the consequences of warfare were changing human relationships and environments, Čapek’s human-centred as opposed to ideological perspectives enabled his work to tackle such issues in ways that were meaningful in a positive way for his contemporary audiences. Čapek’s situation changed for the worse in the 1930s, with writings such as his novel War with the Newts banned by the Nazis for their anti-fascist themes. He died of pneumonia in 1938 shortly after the Munich Agreement (some said of a broken heart) and so could not be arrested when the Nazis came looking for him when they later invaded Czechoslovakia. They found his artist brother Josef, who died in Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, but Josef’s paintings, now well displayed in the National Gallery of Art in Prague, bear witness to the creativity and promise of that new 1920s Czech Republic.

Photo of Edwin Muir, courtesy of the Orkney Library Photographic Archive. Used with permission.

Photo of Edwin Muir, courtesy of the Orkney Library Photographic Archive. Used with permission.It was a very different Prague—what one might call a Kafkaesque Prague—which awaited Muir when he went there as Director of the British Council Institute immediately after World War Two. Muir had heard nothing about Kafka when he first went to Prague in the late summer of 1921; and nothing about the German-speaking Jewish inhabitants of the city, the group to which Kafka belonged. Yet Kafka’s The Castle, the book which Muir and his wife first translated into English in 1930 was both begun and abandoned unfinished during their time in Prague. Now, after years of Nazi occupation, the Prague which they had enjoyed in the company of the Čapeks seemed the “ghost of a vanished age,” as Kafka himself had described the disappearance of the old Jewish ghetto of the city. Muir had driven with a colleague across Europe to his new appointment in Prague, and in his later autobiography he described the conditions they found during their journey in terms that speak freshly today in relation to Syria and Iraq and other war zones we witness nightly on our television screens:

When we reached Germany there seemed to be nothing unmarked by the war: the towns in ruins, the roads and fields scarred and deserted. It was like a country where the population had become homeless, and when we met occasional family groups on the roads they seemed to be on a pilgrimage from nowhere to nowhere.

He continues in words which suggest a possible continuous cycle of warfare throughout human history, an idea which had become a theme of his own war poetry in the 1940s:

Few trains were running; the great machine was broken; and the men, but for the women and children following them, might have been survivors of one of the medieval crusades wandering back across Europe to seek their homes. Now by all appearances there were no homes for them to seek. (An Autobiography, 251)

The poetry Muir wrote about 1940s Prague spoke not only of the effects of the recent war, but also of the subsequent political absorption of Czechoslovakia into the Soviet sphere of influence with the consequences that meant for its people. Seamus Heaney described him as a European poet in relation to this Prague poetry; but all Muir’s writings about Europe, in prose and poetry, tell a story about a period in our wider shared European history that is still relevant to us today. On his 130th birthday, Edwin Muir is also a poet for our own time.

Featured image credit: Prague, Czechoslovakia in 1920. Frank and Frances Carpenter Collection (Library of Congress). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Edwin Muir and a story of Europe appeared first on OUPblog.

Preparing clinical laboratories for future pandemics

The rapid flourishing of the Ebola outbreak in 2014 caught clinical laboratories in the United States off-guard, and exposed a general lack of preparedness to handle collection and testing of samples in patients with such a highly lethal infectious disease. While the outbreak was largely limited to West Africa, fears in the United States became heightened in September of 2014 with the first reported imported case diagnosed in Texas. Most concerning to healthcare professionals was the subsequent news that two healthcare workers involved in caring for the Texas patient contracted Ebola virus disease in mid-October.

Ebola is known to be transmitted via direct contact with body fluids, including but not limited to blood, urine, saliva, and feces. Clinical laboratory personnel routinely collect, process, and test body fluids and thus risk of exposure to Ebola was an immediate concern following news of infected healthcare workers in Texas. While clinical laboratory personnel view all specimens as potentially infectious, it was clear that Ebola virus represented a higher level of risk and concern amongst those in the healthcare community, which led to a rapid effort to implement new procedures, processes, and guidelines for handling specimens from patients with suspected or known Ebola virus disease.

Several questions quickly arose within the clinical laboratory community:

Should clinical laboratories test specimens from patients with suspected or known Ebola virus disease in their main laboratory facilities, on instruments used for routine patient care, or should testing of these specimens be quarantined?

What laboratory tests are necessary for adequate evaluation of patients with suspected or known Ebola virus disease?

Should clinical laboratory personnel be allowed to opt out of collection, processing and/or testing of specimens potentially infected with Ebola virus due to concerns for personal safety?

What level of personal protective equipment, or PPE, should be worn by clinical laboratory workers handling these specimens?

How should specimens be transported for testing within the clinic/hospital or for shipment to outside testing facilities?

In the summer of 2014, the University of Minnesota Medical Center and its affiliated non-profit healthcare system, Fairview Health Services, determined that establishing a stand-alone clinical care unit and laboratory for the care of Ebola patients was a priority. With no firm consensus guidelines published on how to set up a containment laboratory from scratch, we set forth to answer the above questions in consultation with the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). We also referred to the first publication with details on providing quarantined laboratory testing for Ebola patients, published by providers at Emory University Hospital on their high-containment facility.

We then established our own process for a stand-alone laboratory for the care of patients with Ebola virus disease. The first step was deciding that all clinical laboratory testing on suspected or known Ebola patients would be quarantined and performed on instruments dedicated for use on Ebola patients only. Given the high level of risk and concern surrounding Ebola, we did not feel comfortable requiring all laboratory staff to work in the containment lab. Instead, we decided to seek volunteers amongst our clinical laboratory personnel to staff the facility. We were fortunate to have an adequate number of volunteers who were able to provide on-call coverage for the laboratory 24/7.

Soldier-scientists begin closure of Ebola testing labs by Army Medicine. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Soldier-scientists begin closure of Ebola testing labs by Army Medicine. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Out of concern for the safety of our laboratory personnel, we decided that laboratory staff would wear head-to-toe personal protective equipment (PPE) that included a hooded respirator, impermeable gown, boot covers, and double layer of gloves. We also purchased two level 2 biosafety cabinets where staff would work when handling or manipulating samples for testing, for added protection. Since our Ebola care unit was quarantined, transport of samples within our hospital was minimized and only required movement across a small hallway from the patient care room to the laboratory space. The only testing performed outside our hospital involved screening or confirmation for the presence of Ebola virus; this testing was performed by the MDH and CDC, and we followed their instructions for specimen collection and transport.

While the 2014 Ebola outbreak caused some momentary chaos for clinical laboratories in the United States who were unprepared to initially handle these specimens, the chaos of that time has borne fruit with several detailed publications and guidelines outlining how to safely and effectively perform clinical laboratory testing on patients with suspected or known Ebola or other highly infectious diseases. This includes detailed guidance from the CDC on specimen collection, transport and submission of specimens, packing and shipping of specimens, and managing and testing routine clinical specimens. These guidelines provide a robust framework that can be used if and when future pandemics arise. Additionally, our facility at the University of Minnesota Medical Center was selected to serve as one of nine regional treatment centers for Ebola or other severe, highly infectious diseases, with support funding awarded from the US Department of Health and Human Services. The clinical laboratories at these centers are currently ready and able to provide immediate quarantined testing, and thanks to the lessons learned from the Ebola outbreak, we are better prepared to handle future pandemics, should they arise.

Featured image credit: “Medic Hospital Laboratory” by DarkoStojanovic. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post Preparing clinical laboratories for future pandemics appeared first on OUPblog.

Hamilton: the man and the musical

For the past two years, the hip-hop musical Hamilton has been the toast of New York, winning all the awards—Grammys, Tonys, and even a Pulitzer Prize—and grossing higher receipts than any Broadway show in history. It’s coming to London later this year, November 2017, and judging by the interest and hype is already guaranteed to be a sell-out success for years to come. But this is not a musical biography of a town called Hamilton, nor of that most scholarly of Scottish football teams, Hamilton Academicals, nor of the Formula One driver of that name, who might seem on the face of it to live the kind of exciting life that would lend itself to the drama of musical theatrics. Rather, the subject of this blockbuster show is an ideologist, politician, statesman, soldier, and author who lived in the American colonies in the middle of the eighteenth century and took a leading role in achieving American Independence. How come? Who cares?

A biopic on George Washington might carry the day; a show devoted to Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, he of the lightning rod and other experiments with electricity, and another Revolutionary hero, might have its interest. But to make a musical out of the life of the Secretary of the US Treasury, even the first such, must surely be a recipe for disaster, one of those shows that opens and closes inside three days, never even reaching a Saturday matinee. Imagine an equivalent in Britain about the life of a chancellor of the exchequer: thrill to the thoughts of Gordon Brown, set to music the search for George Osborne’s political identity, or explore the tragic inner world of Philip Hammond. No, they wouldn’t work, would they? But very many people will spend considerable sums on tickets to see a show about a man no one had heard of before the author of the piece, Lin-Manuel Miranda, set Alexander Hamilton’s life to music.

In fact, for aficionados of early American History and of the history of finance more generally, Alexander Hamilton holds a special place in our affections. For he had the early vision to see the future of America as industrial, commercial and urban while many of the colleagues with whom he had made the revolution, such as Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, the third and fourth Presidents respectively, thought of the new United States as an agrarian republic of farmers. Hamilton not only saw the future correctly; he helped to make it happen by controversial but far-sighted measures when in office in the early 1790s, and by writing three famous reports on national credit, a national bank, and manufactures which charted the course to the future. He saw something else, as well, in these formative years of the Republic: the utility of public debt. Americans had to be given a reason to support their new national government, established by the Federal Constitution of 1787, and debt could help in this. By encouraging them to lend to the new United States, to become its creditors, the national debt thus established would bind the people to the health and durability of their new institutions, giving them a stake in the “great experiment” in popular self-government that is America. If it failed, they’d lose their shirts.

But though these ideas were controversial and gave Hamilton a reputation for financial trickery not unlike that of unloved bankers today, they are hardly the stuff of which a musical is composed. Try setting the national debt to music. Nor can much be made, it might be thought, from Hamilton’s most enduring literary legacy, his contributions to the Federalist Papers, the most important commentary on the principles of the American Constitution and the workings of American government ever published. In the winter of 1787–8, Hamilton joined with John Jay and James Madison, two other federalists—supporters of a federal government and a union of the American states to make a new nation—to write a long series of essays, some 84 in all, to persuade the citizens of New York City to support the new political structures devised the previous summer at a four-month convention in Philadelphia. Dissecting and explaining the Constitution in minute detail, these essays take us into the minds of the founding fathers of America and stand for all time as a commentary on the political thought of the Revolutionary generation. But hip-hop they are not. It’s difficult to imagine many citizens of New York making clear sense of these difficult academic articles which were published three times a week in the city’s newspapers in 1788, let alone setting them and their ideas to music and serving them hot to audiences in New York and London, the cities where America was won and lost, nearly 250 years later.

So what’s going on here? In fact, Hamilton’s life has human interest in abundance. He was born in the British West Indies, found his way to New York, attended what became later Columbia University, and like many graduates after him, became a lawyer. So far, it’s a story of hard work, determination, talent and upward social mobility. Drawn into revolutionary circles, Hamilton volunteered to fight in George Washington’s Continental Army and his abilities swiftly saw him appointed as aide de camp – first assistant – to the great general who became America’s first president. Victory over the British was in some measure Hamilton’s victory.

Unity among those who made the revolution was fractured, however, once the United States came into being and the hard business began of governing a new nation in the 1790s. Hamilton’s vision of the future was not shared by his erstwhile colleagues and collaborators, Madison and Jefferson. They favoured France in the wars that erupted in Europe in the 1790s, while Hamilton openly admired the British flair for finance and stable government. They saw rolling fields of corn stretching across America—“those who labour in the earth are the chosen people of God” wrote Jefferson—while Hamilton foresaw roads, ports, and factories. Hamilton could see how finance could be set to work to secure support for the Revolution; his opponents looked on banks, bankers, and debt as the devil’s work. The revolutionary elite, who had fought and schemed together, now parted ways, and Hamilton resigned as Secretary of the Treasury in 1794. Personal tragedy was to follow: Hamilton’s son was killed in a duel trying to defend his father’s reputation. Meanwhile, Hamilton himself developed a bitter animosity towards a political opponent and rival, one Aaron Burr. While Burr was serving as the third Vice President of the United States, he killed Hamilton in a duel in 1804.

Historians may find fault with the details of this musical, but they always will. That’s their job. That’s why we have historians, to tell us what’s wrong when people use and abuse the past. The issue here is not the small liberties that the show takes with Hamilton’s life and the details of the Revolution. Rather, it’s the difference between what historians prize in Hamilton’s biography—his ideas, his reports, his stewardship of the infant nation’s money, his vision of the American future—and the focus of the show on the personal details of family, love, betrayal, and death.

Yet one thing has united the historians and the mass audience for Hamilton: the campaign to keep his thoughtful, patrician features on the face of a $10 bill. Most of those who grace US dollar denomination bills—Washington ($1), Jefferson ($2), Lincoln ($5), Jackson ($20) and Grant ($50)—are presidents. The only other exception to this rule is the $100 bill bearing the engaging image of Ben Franklin. Long ago, the US Treasury had the wit to understand the enormous contribution made by Hamilton to the American future and to immortalise him as the personification of $10. But when the federal government decided that this male club should be broken up and an image of the escaped slave and abolitionist Harriet Tubman substituted for the image of a male statesman at some time after 2020, it was Hamilton they chose to stand down. However, the very success of the show and the resulting public outcry from the fans has led to his reinstatement, an outcome welcomed by the scholars. Now it is Andrew Jackson on the $20 bill who will be lost, which is surely a better choice because Jackson was a notorious and violent opponent of native Americans and a slaveholder to boot.

Hundreds of millions of people will continue to see Hamilton’s face as they pull out money from a pocket or purse to pay for a beer or a burger. They will think of a brave man with flaws, regrets, and enemies as the tunes from the show flow through their heads and out through their lips. Expect to hear singalongs at the checkout in American stores rather than recitations from the Federalist Papers. But will it matter that the author of fifty-one of those famous essays is remembered in this way? Better surely, that he should be remembered at all, than that his achievements should be overlooked and his life forgotten. Who knows, it may start a trend: Lincoln on ice; Roosevelt the ballet; Clinton the movie. On second thought…

Featured image credit: “Constitution” by wynpnt. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post Hamilton: the man and the musical appeared first on OUPblog.

The mixed messages teens hear about sex and how they matter

Although they start having sex at similar ages to teens in many other developed countries, US teens’ rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), pregnancies, abortions, and births are unusually high. Besides high levels of socioeconomic inequality, a major reason is their inconsistent use of contraceptive methods and low uptake of highly effective contraception. After investigating the cultural messages teens are hearing about sex, contraception, and pregnancy, I am convinced that these social norms and the social control of teens that comes with them are important culprits.

My research team interviewed college students and teen parents from many different places and backgrounds, asking them about the norms and social control around sex and pregnancy they experienced in high school. The interviewees depicted a complex social world of potent messages, inconsistencies, gossip, silence, conflicting control by others, and push back from teens themselves. Several normative dynamics undermine teens’ ability to use highly effective contraception consistently, these include:

1. Adults’ strong negative norms are usually paired with a lack of support for avoiding pregnancy and STIs. Parents, peers, and other adults uniformly discouraged teen pregnancy, as well as teen sex in most cases. But strong negative norms were rarely accompanied by concrete support for how to use contraception or say “no” to sex. Isaac told us that parents in his community said to teens, “Don’t get pregnant. I don’t care how you do it. I’m not going to give you condoms. You’re not supposed to get pregnant when you’re seventeen.” Alana’s mother’s message was similar in its strong discouragement paired with no concrete advice or support: “Every weekend when I would go out with my friends, she would say, ‘Don’t do anything stupid. Don’t do anything I wouldn’t do. Be responsible. I hope you’re not fooling around.’” These strong messages left young people afraid to turn to adults for help about how to avoid sex or pregnancy, for fear of the social judgment that might follow.

Although some close friends help each other access contraception or share information about sex, peers are mostly a threat rather than a source of support.

2. So that the teen can avoid negative sanctions, teens and the people who care about them are motivated to avoid sharing information about the teen’s violations of norms. This encourages conspiracies of silence between teens and adults. At the same time, like their US peers, most of my interviewees were sexually active during high school, but nearly all families avoided having the “me having sex talk.” When teens can’t acknowledge their sexual activity to their parents, it’s hard to use effective long-acting contraceptives like birth control pills or intrauterine devices. Teens may even avoid planning for sex with having contraception available, thus being able to claim the sex was a mistake and they didn’t set out to violate any norms. Such a strategy puts teens at risk for pregnancy and STIs.

3. Many schools are not filling this information vacuum around sex and pregnancy. Most US parents would like schools to teach teens both to wait with sex and how to avoid pregnancy and STIs if they are sexually active. According to our interviewees, some schools teach this information, but many do not. Instruction involving slide shows with pictures of STIs and lists of the failure rates of different types of contraception were common, but learning how to use contraception effectively was less so. It seems that many schools try to avoid controversy around teen sex and abstinence by reducing the information they provide. This may help a curriculum seem politically neutral, but also results in teens learning less about how to avoid sexual risks.

4. Peers aren’t filling the gap either. Although some close friends help each other access contraception or share information about sex, peers are mostly a threat rather than a source of support. The facts about teens’ sexual behaviors often have little to do with the rumors other teens believe. People make assumptions about teenagers’ (especially girls’) sexuality based on their race, class, and academic achievements. Over and over, participants discussing pregnant girls assumed that they were promiscuous, even though research shows that they’re more likely to be in a long-term romantic relationship. Ella expressed fear around teen pregnancy that “people will think I’m a slut. I think that’s what girls were more afraid of, the fact they’d be labeled a slut more than being pregnant.” Boys were almost never labeled this way, even when they were fathers. Wealthier White teens were more able to label their sexual behavior as a regrettable “mistake” and avoid getting stuck with a stigmatizing label. The loose link between facts and social judgments strengthens the climate of fear for many teens, making them less likely to seek support among peers.

What can be done? One option is to increase contraception access without parental involvement. Interventions like this one in Colorado have made highly effective contraception available to young women at no cost, driving steep drops in the teen birth rate. Another is to change norms to focus on encouraging teens to make deliberate, mature decisions about sexual behaviors and seek support from adults when they do become sexually active. A similar shift in norms occurred in the Netherlands after widespread public discussion, with subsequent improvements in teens’ sexual health. Paradoxically, by giving teens more power over their own decisions, we may be able to bring their sexual behaviors more in line with our goals for their futures.

Featured image credit: people teenagers young group by Unsplash. Public domain via Pexels.

The post The mixed messages teens hear about sex and how they matter appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers