Oxford University Press's Blog, page 364

May 21, 2017

The Walking Dead and the security state

Did The Walking Dead television series help get President Donald J. Trump elected? During the presidential campaign, pro-Trump ads regularly interrupted episodes of the AMC series. Jared Kushner, who ran the campaign’s data program, explained to Forbes that the campaign’s predictive data analysis suggested it could optimize voter targeting by selectively buying ad-space in shows such as The Walking Dead. The data indicated that a large segment of the show’s audience was already worried about immigration. Perhaps its zombie hordes, scavengers, and survivalist communities spoke to the immigration anxieties the Trump campaign mobilized. Whether this is true or not, the series played a small but interesting role in what appears in retrospect to be a redefinition of migration as a state security problem, which in itself is hardly a new development. The Trump presidency would soon vehemently insist that the world outside of Fortress America is filled with dangerous hordes, and that travel bans, walls, and undocumented migrant sweeps are necessary for its protection.

Dystopian fictions like The Walking Dead and security both seem like growth industries today. In fact, dystopia has becomes the “default narrative of the generation” according to the novelist Junot Díaz, whose next novel seems likely to include zombies and border walls. Zombies shamble across our TV screens while older dystopias like Mad Max have been refurbished for new audiences. Just like Hollywood, serious contemporary novelists including Margaret Atwood with The Handmaid’s Tale, Cormac McCarthy, Chang-Rae Lee, and Colson Whitehead continue to update the dystopian genre. Meanwhile young adult fiction editors are tired of the flood of dystopian fiction. At least there dystopia has become a hard sell. Everywhere else the world always seems to be ending for somebody.

The hyperinflation in the fortunes of dystopian fiction is matched perhaps only by the growth of security. Promising to protect us (and our property) from harm, security is invoked everywhere as an irrefutable need for a less risky future. The word has attached itself to numerous fields ranging from national and human security to climate, cyber and food security. Recently, we were reminded of the expansion of surveillance by a WikiLeaks info dump revealing how the CIA can now hack Apple, Samsung, and Microsoft devices in the name of security. Inaugurated with the National Security Act of 1947 that established the CIA, the US national security state too has grown rapidly with the establishment of the Department of Homeland Security and the expansion of governmental data capabilities. By 2010 the security state had developed into a network comprising “1,271 government organizations and 1,931 private companies” as Dana Priest and William M. Arkin uncovered. With the Trump administration ready to invest vast sums in border security and the Pentagon, while cutting everything else, fortune favors the security state.

Something is happening here. Perhaps the dystopias and proliferating threats of contemporary fiction (and policy forecasts) have a pedagogical force, offering instruction in insecurity even while feeding into a desire for more security. Or is it that the expanding security state can only justify itself by projecting and standing against a world of growing threat and dystopian presentiments? It is not difficult to speculate that dystopian effects—feelings of insecurity and vulnerability—are the residues left behind by this viciously circular motion. In this sense, security produces not just safety, if it does so at all, but insecurity, which is captured by the dystopian mood of shows like The Walking Dead. What then came first, the zombie or the wall? Wherever you come down on that question, security and narrative of insecurity are inextricably intertwined in the contemporary political and literary landscape. We can see the results in more places than just within dystopian fictions. Think here of Ben Lerner assuming the role of the Walt Whitman of Manhattan’s “vulnerable grid” in 10:04, or Dana Spiotta exploring in Stone Arabia the terrors nightly news bring into the home. But it wouldn’t do to associate contemporary US fiction just with experiences of insecurity. Dave Eggers, Atticus Lish, Nathaniel Rich, Amy Waldman, and Jess Walter have all written about one side or another of the security sector. Once upon a time literature was meant to cure terror, Don DeLillo has a character say in Point Omega. Perhaps, but that hardly seems to do justice to the contemporary fictions of (in)security.

Featured image credit: cinema film movie theater by coombesy. Public domain from Pixabay.

The post The Walking Dead and the security state appeared first on OUPblog.

What everyone needs to know about Russian hacking

A generation ago, “cyberspace” was just a term from science fiction, used to describe the nascent network of computers linking a few university labs. Today, our entire modern way of life, from communication to commerce to conflict, fundamentally depends on the Internet. The cybersecurity issues that result challenge literally everyone: politicians wrestling with everything from cybercrime to online freedom; generals protecting the nation from new forms of attack, while planning new cyberwars; business executives defending firms from once unimaginable threats, and looking to make money off of them; lawyers and ethicists building new frameworks for right and wrong. Most of all, cybersecurity issues affect us as individuals.

Ever since the 2016 election in the United States, the mention of Russia and cybersecurity in the news has been inescapable. In the following testimony, PW Singer acknowledges the fact that the attacks by the Russian government are only one aspect of a larger threat landscape. He explains that these threats are not only dangerous because of their past impact, but also because of how they will serve as a guidepost to others in the future, stressing that as the internet and technology continue to change, the United States needs to build a new set of approaches to protect ourselves better.

Hackers working on behalf of the Russian government have attacked a wide variety of American citizens and institutions. They include political targets of both parties, like the Democratic National Committee, and also the Republican National Committee, as well as prominent Democrat and Republican leaders, civil society groups like various American universities and academic research programs. These attacks started years back, but have continued after the 2016 election. They have hit clearly government sites, like the Pentagon’s email system, as well as clearly private networks, like US banks.

In addition to attacking this range of public and private American targets, over an extended period of time, this Russian campaign has also been reported as targeting a wide variety of American allies. These include government, military, and civilian targets in the United Kingdom, Czech, and Norway, as well as now trying to influence upcoming elections in Germany, France, and Netherlands. Overall, reports are that Russian cyber attacks on NATO targets are up 60%, against EU institutions up 20%, in the last year.

This is not the kind of “cyber war” often envisioned, with power grids going down in fiery “cyber Pearl Harbors.” Instead, it is a competition more akin to the Cold War’s pre-digital battles that crossed influence and subversion operations with espionage. Just as then, there is a new need for new approaches to deterrence that must reflect a dual goal to defend the nation, as well as keep an ongoing conflict from escalating into physical damage and destruction.

“Nor is cybersecurity a concern for only one political party. It is an issue for Everyone.”

While Vladimir Putin has denied the existence of this campaign, its activities have been identified by groups that include all the different agencies in the US intelligence community, the FBI, as well as multiple allied intelligence agencies, who have seen the very same Russian efforts hit their nations and various international organizations (most notably the World Anti-Doping Agency). This campaign has also been established by the marketplace; five different well-regarded cybersecurity firms (Crowdstrike, Mandiant, Fidelis, ThreatConnect, and Secureworks) have identified it. This diversity of firms is notable, as such businesses are competitors and incentivized instead to debunk each other’s work. Indeed, even the most prominent individuals, who first denied the existence of the hacks and then the role of the Russian government in them, now acknowledge this campaign; this now includes even the US president (“As far as hacking, I think it was Russia.” President Trump stated at his January press conference).

It is time to move past the debate that consumed us for the last year. The issue at hand is not whether Russia conducted a series of cyberattacks on the United States and its allies. We know it did. Nor is cybersecurity a concern for only one political party. It is an issue for Everyone. The real question now is whether the United States will ever respond?

This excerpt of Singer’s testimony was originally published as “Cyber-Deterrence And The Goal of Resilience: 30 New Actions That Congress Can Take To Improve U.S. Cybersecurity” at the hearing on “Cyber Warfare in the 21st Century: Threats, Challenges, and Opportunities” before the House Armed Services Committee.

Featured image credit: “Hacked, Cyber Crime” by HypnoArt. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post What everyone needs to know about Russian hacking appeared first on OUPblog.

How well do you know Simone de Beauvoir? [quiz]

This May, the OUP Philosophy team honors Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986) as their Philosopher of the Month. A French existentialist philosopher, novelist, and feminist theoretician, Beauvoir’s essays on ethics and politics engage with questions about freedom and responsibility in human existence. She is perhaps best known for Le deuxième sexe (The Second Sex), a groundbreaking examination of the female condition through an existentialist lens and a key text to the Second Wave feminist movement of the 1960s and 70s. Even among her critics, Beauvoir is widely considered the most significant influence on feminist theory and politics during the course of the twentieth century.

You may have read her work, but how much do you really know about Simone de Beauvoir? Test your knowledge with our quiz below.

Quiz image: Jean Paul Sartre and Simone De Beauvoir. Photo by Moshe Milner. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image: Pont des Arts, Paris. Photo by Benh LIEU SONG. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How well do you know Simone de Beauvoir? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

May 20, 2017

Catching up with Nicole Piendel, Multimedia Producer

Another week, another great staff member to get to know. When you think of the world of publishing, the work of videos, podcasts, photography, and animated GIFs doesn’t immediately come to mind. But here at Oxford University Press we have Nicole Piendel, who joined the Social Media team as a Multimedia Producer at the start of this year.

When did you start working at OUP?

January 2017.

What is the most exciting project you have been part of while working at OUP?

During my second month, I had the pleasure of filming an interview with Chelsea Clinton and Devi Sridhar for their book Governing Global Health. Also, I filmed a video for National Puppy Day in Madison Square Park; we got to hang out with some of the cutest dogs in NYC.

What’s the first thing you do when you get to work in the morning?

Grab a coffee, check my emails, and then straight to video editing.

If you didn’t work in publishing, what would you be doing?

Image provided by Nicole Piendel.

Image provided by Nicole Piendel.I would be pursuing my career as a Producer for a network like NBC or HBO. Or, I would love to be the first female coach in the National Football League.

What is your most obscure talent or hobby?

I don’t mean to brag, but I am incredibly good at Fantasy Football. I won last season in a team full of nine men and myself (girl power).

What is your favorite animal?

Hands down a sea lion. Have you ever pet a sea lion? It’s life changing.

What’s your favorite book?

For Today I Am a Boy by Kim Fu

If you could trade places with any one person for a week, who would it be and why?

I would change lives with Anthony Bourdain in a heartbeat. That man gets paid to travel, eat, and explore while having his own TV show. I am convinced he is the most interesting man in the world.

What is the strangest thing currently on or in your desk?

I wouldn’t say strange but seasonal; chocolate covered matzos.

If you were stranded on a desert island, what three items would you take with you?

Green tea ice cream, my iPod, and my cat Thor.

Featured image credit: Camera by republica. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Catching up with Nicole Piendel, Multimedia Producer appeared first on OUPblog.

Looking for Toussaint Louverture

I have a confession to make: I have a personal obsession with the Haitian revolutionary hero Toussaint Louverture, which has taken me from continent to continent in search of the “real” Toussaint Louverture.

My pilgrimage started outside Cap-Haïtien, Haiti’s second-largest town, in the suburb of Haut-du-Cap, where Toussaint Louverture was born a slave in what was then known as French Saint-Domingue. The spot is difficult to miss: a statue of Toussaint Louverture stands just off the road and the high school that now occupies the site bears his name. Toussaint Louverture’s presence is inescapable in Haiti: the main airport in Port-au-Prince is named after him and his likeness adorns various stamp issues and the 20-gourde note.

The man behind the myth is more difficult to trace. The sugar plantation where he was born has mostly disappeared (the last walls were bulldozed a few years ago because the high school principal wanted to extend the recess area). According to most books, he was born on 20 May 1743, exactly 274 years ago. But there is no evidence for this claim in the archives: early sources list various years ranging from 1737 to 1756. His first name, which means “All Saints Day” in French, also suggests that he was born on 1 November, not 20 May. His full name, typically rendered as François Dominique Toussaint Louverture, also owes more to legend than fact: no baptismal record has survived. Like all slaves, he only had a first name (he took on the surname of “Louverture” in the 1790s).

Sources about Toussaint Louverture only become plentiful with the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution in 1791, by which time he was about 50 years old. But his years as a revolutionary did nothing to clarify his record: he defeated French planters, as well as the British and Spanish invaders who tried to re-enslave his people, but he also opposed attempts to export the slave revolt to nearby isles and enforced a strict discipline on the workforce he had helped emancipate. His rhetoric changed markedly whether he addressed elite planters or rebel slaves.

Toussaint Louverture on horseback. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Toussaint Louverture on horseback. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Artistic depictions of Toussaint Louverture at his apex, when he became governor of Haiti in 1801, are equally confounding. They vary widely in appearance, his skin color ranging from very dark to almost white. Most were drawn by people who had never met him; he refused to have his likeness taken.

Archival sources should fill in the blanks, but the many official documents that bear his name often contradict one another. Forced to adapt to the changing circumstances of a revolution, he preferred to hide his true intentions.

Only after Toussaint Louverture was overthrown from office by Napoléon Bonaparte in 1802 did he reflect on his record. Exiled to the fort of Joux on the French-Swiss border, he drafted a lengthy account of his career in his own hand. But even that memoir was more remarkable for its omissions than its revelations: “I was a slave, I dare to declare it”—such was the only reference to his pre-revolutionary life in the text. He passed away on 7 April 1803, taking his secrets with him.

Toussaint Louverture’s cell can still be visited today. It is damp, dark, and gloomy—and mostly empty. For a time, a skull fragment allegedly taken from his remains was on display for the benefit of tourists. That relic was likely a fake—his actual body has been lost.

From Haut-du-Cap to Fort de Joux, Toussaint Louverture is at once omnipresent and elusive. This was intentional—he was purposely deceitful and secretive, which is why it’s so difficult (and fascinating) to pin him down.

As a result, the “real” Toussaint Louverture has been subsumed by mythical alter egos in popular memory. During the revolutionary era, British artists gave him a British officer’s uniform to claim him as their own. Nineteenth-century abolitionists also admired him as an apostle of emancipation, though they chose to Europeanize his features to make him less threatening to white audiences. By contrast, it was his very blackness and martial bearing that made him appealing to US black nationalists and to Haitians, who typically represented him as a black general striking a heroic pose.

Toussaint Louverture’s indefinability has made it easy to re-appropriate him. He is now an international icon. France, which has recently reexamined its implication in plantation slavery, has adopted him as a revolutionary hero: various government-commissioned statues now honor him from Bordeaux (where his son died) to La Rochelle (a prominent slave-trading center). Even Benin, which he never visited, now has a statue honoring “the proud son of Allada” to honor the millions of Africans (including his parents) who were victimized by the slave trade.

These conflicting interpretations of Toussaint Louverture tell us little about the real man. Instead, they serve as a Rorschach test. Tell me which Toussaint Louverture you like, and I’ll tell you who you are.

Full disclosure: the portrait I chose for my office features him as a French revolutionary officer fighting for emancipation and the rights of men.

Featured image credit: “Attack and take of the Crête-à-Pierrot” by Auguste Raffet. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Looking for Toussaint Louverture appeared first on OUPblog.

Analyzing “Expressiveness” in Frankenstein (1931)

In Hollywood Aesthetic: Pleasure in American Cinema, film studies professor Todd Berliner explains how Hollywood delivers aesthetic pleasure to mass audiences. Along the way, Professor Berliner offers numerous aesthetic analyses of scenes, clips, and images from both routine Hollywood movies and exceptional ones. His analyses, one of which we excerpt here, illustrate how to study a film’s aesthetic properties.

In Hollywood cinema, style does more than deliver story information. It also increases the expressive power of a story by establishing mood, emphasizing the story’s meaning, enlivening characterization, enhancing the narrative’s emotional development, and intensifying the story’s cognitive and affective impact.

Take, for example, the scene in Frankenstein (1931) in which a father carries his daughter’s lifeless body through town. After the Monster kills the little girl, the father interrupts a festive outdoor celebration as other villagers carouse and dance. Story information alone emphasizes the intrusion of horror on the festivity, but the challenge for the filmmakers is to shoot the scene in a style that maximizes its expressiveness, both stressing the point of the scene and enhancing its emotional impact. The obvious solution would be to show the appearance of the father at the celebration and then cut to the villagers’ reactions, a stylistic choice that would clearly and immediately express the shock of the event. The film could sustain that moment for 5 or 10 seconds, cutting to various astonished villagers to fully express the transition from festivity to horror. Cinematographer Arthur Edeson and director James Whale, however, use an even more expressive stylistic solution, one that both communicates shock and extends the instant of transition for almost a minute of screen time.

The filmmakers stage the event so that villagers see the dead girl not all at the same time but rather one after another. In two long takes, lasting a total of 48 seconds, the camera tracks sideways and backward with the distraught father as he carries his daughter’s corpse through the celebration (video 5.2). The framing and deep focus of these shots enable spectators to witness again and again each moment when different villagers at the party first see the dead child, their expressions turning from merriment to gaping horror. Notice in figures 5.3 and 5.4, for instance, that all of the characters on the right side of the frame express shock on their faces, whereas the characters on the left side of the frame, who have not yet seen the father and the dead girl, are still celebrating; their faces, too, will soon turn to shock as the father and tracking camera pass them by.

https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/05.2Frankenstein.mp4

Figure 5.2. Video clip from Frankenstein (1931). Featured on the companion website to Hollywood Aesthetic: Pleasure in American Cinema by Todd Berliner. Used with permission.

Figure 5.3. Still image from Frankenstein (1931). Pg. 93 of Hollywood Aesthetic: Pleasure in American Cinema by Todd Berliner. Used with permission.

Figure 5.3. Still image from Frankenstein (1931). Pg. 93 of Hollywood Aesthetic: Pleasure in American Cinema by Todd Berliner. Used with permission. Figure 5.4. Still image from Frankenstein (1931). Pg. 93 of Hollywood Aesthetic: Pleasure in American Cinema by Todd Berliner. Used with permission.

Figure 5.4. Still image from Frankenstein (1931). Pg. 93 of Hollywood Aesthetic: Pleasure in American Cinema by Todd Berliner. Used with permission.The filmmakers have selected a staging and cinematography style that intensifies the emotional expressiveness of the moment by sequentially portraying, for dozens of characters, the instant of shock. This stylistic choice also enables the film to depict festivity and shock at the same time, rather than replacing one with the other, since at each moment during these two shots we see in the frame some villagers celebrating and others suddenly in dismay. Throughout the sequence, moreover, we hear some voices expressing shock (“Look, Maria!”) and others whooping and cheering in celebration. Talented filmmakers, such as Edeson and Whale, find creative techniques that enhance a scene’s expressiveness while conforming to Hollywood’s general stylistic parameters.

Featured image: Frankenstein (1931) movie poster. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Analyzing “Expressiveness” in Frankenstein (1931) appeared first on OUPblog.

The illegitimate open-mindedness of arithmetic

We are often told that we should be open-minded. In other words, we should be open to the idea that even our most cherished, most certain, most secure, most well-justified beliefs might be wrong. But this is, in one sense, puzzling. After all, aren’t those beliefs that we hold most dearly–those that we feel are best supported–exactly the one’s we should not feel are open to doubt? If we found ourselves able to doubt those beliefs – that is, if we are able to be open-minded about them–then they aren’t all that cherished, certain, secure, or well-justified after all!

This has led some philosophers to treat open-mindedness, not as an attitude that applies to particular beliefs, but rather as a second-order attitude that applies to our body of beliefs as a whole. I can’t do full justice to this sort of approach here, but the following should give one an idea of what is going on.

To make things concrete, let’s let Φ(x) be a predicate that applies to numbers, and let’s say that I have checked each number from 1 to n individually, and verified that it has the property expressed by Φ(x) (perhaps by a lengthy pen-and-paper computation).

In such a situation, I can (and probably should) strongly believe each of:

Φ(1), Φ(2), Φ(3),… Φ(n)

that is:

Φ holds of 1, Φ holds of 2, Φ holds of 3,… Φ holds of n.

After all, I have checked each one.

Now, on a second-order approach, open-mindedness with regard to my judgements about Φ(x)-ness doesn’t involve my having doubts about some particular number m between 1 and n. Rather, it amounts to my being open to the idea that I might have made a mistake somewhere, even if I don’t know where (and even if, further, for each particular number between 1 and n, I am certain I didn’t make a mistake there). In other words, open-mindedness on this account amounts to rejecting (or, at the very least, not strongly believing):

For every m between 1 and n, Φ(m)

Thus, if we are open-minded about our judgments regarding Φ(x), then I can be extremely confident in each of my individual judgements regarding a particular number satisfying Φ(x), but I should be far less confident in the single judgement codifying the thought that I got all of them right.

Now, in real life there are very good reasons for being open-minded in this way–after all, we are fallible, and no matter how careful we are, mistakes slip in (especially in real-life examples more complicated that our toy example above). But it turns out that formal Peano arithmetic is open-minded in a similar way, even though (unlike us mere humans) arithmetic has no good reason to be open-minded.

So let’s just assume that we are working with Peano arithmetic, or some similar system of axioms for arithmetic. The crucial facts we need for what follows are that our axioms (i) are consistent (do not allow us to prove any contradictions, (ii) are sufficiently strong (in technical jargon: they allow us to represent recursive functions and relations), and (iii) can be finitely described (in technical jargon: they are themselves recursive). Then it follows that our system of arithmetic is w-incomplete: there is some predicate Φ(x) in the language of arithmetic such that each of:

Φ(1), Φ(2), Φ(3),… Φ(n), Φ(n+1),…

is provable from our axioms, yet:

For any number n, Φ(n) is not provable.

In other words, for any consistent, sufficiently strong recursive set of axioms for arithmetic, there is a predicate Φ(x) such that, for each particular number n, we can prove the sentence that says that n satisfies Φ(x), but we cannot prove the single sentence that says that all numbers satisfy Φ(x). This is one of the important corollaries of Gödel’s incompleteness theorems (as well as other important results in the metatheory of arithmetic).

Note that, other than the fact that we are now talking about the infinite list of all numbers, rather than merely a finite initial segment of the natural numbers, this has exactly the same structure as our toy example of open-mindedness above (except with “strong belief” replaced with “provability”). In the original example we had a case where we strongly believed each of a (finite) list of sentences, but (if we are being open-minded) we do not strongly believe the single sentence expressing the claim that we are right about all of these particular instances. In the second example we have a case where our theory proves each member of a list of sentences (infinite) but does not prove the single sentence codifying the claim that all of these particular instances are true.

In other words, it seems very natural to understand the phenomenon of w-incompleteness as an instance of open-mindedness in arithmetic: no matter which axioms for arithmetic we pick (so long as they are consistent and recursive) there is a predicate such that arithmetic ‘strongly believes’ (that is: proves) each instance of the form Φ(m), but does not ‘strongly believe’ (i.e. prove) the single claim expressing all of these at once (i.e. “For all n, Φ(n)”)

This is deeply puzzling, however. Human beings, as we already noted, are extremely fallible. Thus, it makes sense that, for us, open-mindedness is a virtue. But the standard axioms for arithmetic–Peano arithmetic–are true, and hence only allow us to prove true claims. In other words, arithmetic (unlike any human being) is infallible, so it has no need to be open-minded. But Peano arithmetic is nevertheless (something very much like) open-minded about what it can prove.

So, while human beings, who are fallible, often fail to be open-minded about their beliefs, arithmetic, which isn’t fallible, and thus has no reason to be open-minded, is, as a matter of mathematical necessity, open-minded about what it can prove.

Featured Image: Formula mathematics blackboard. Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post The illegitimate open-mindedness of arithmetic appeared first on OUPblog.

May 19, 2017

The Eurovision Song Contest over the years: OUP staff select their favorite hits [a playlist]

It’s that time of year again for the unique, bizarre, extravagant and often politically charged spectacle that is the Eurovision Song Contest. The contest which began in 1956 is popular worldwide, with viewer ratings increasing each year (reaching over 200 million in 2016). Whether you love it or hate it, the musical contest has a global appeal that can neither be denied nor ignored.

To help celebrate the eccentricity of European pop culture in light of the big evening in Kiev, Ukraine, Oxford University Press staff have selected a list of their favorite Eurovision hits from across the decades; from the addictive to the utterly ridiculous. Fly your flags and enjoy!

An OUP approved playlist:

Featured image credit: “Kiev” by tpsdave. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post The Eurovision Song Contest over the years: OUP staff select their favorite hits [a playlist] appeared first on OUPblog.

Lactate: the forgotten cancer master regulator

In 1923 Nobel laureate Otto Warburg observed that cancer cells expressed accelerated glycolysis and excessive lactate formation even under fully oxygenated conditions. His discovery, which is expressed in about 80% of cancers, was named the “Warburg Effect” in 1972 by Efraim Racker. The Warburg Effect in cancer and its role in carcinogenesis has been neither understood nor explained for almost a century. Warburg started the field of cancer metabolism, which became the predominant field in cancer research for several decades after. However, the entire research in cancer took a dramatic turn upon the arrival of genetics when in 1953 Nobel laureates James Watson and Francis Crick discovered the structure of DNA. By the 1980s and onwards, cancer research was fully embedded in the genetics field around the world due to the excitement of genetics and all of its possibilities to cure diseases. In the meantime, cancer metabolism was forgotten and buried at the bottom of the ocean.

Unfortunately, the fight against cancer solely through genetics has probably been one of the biggest mistakes in medical research history, after half a century of research and hundreds of billions of dollars deployed, the cure against cancer through genetics remains elusive and far away from a reality. James Watson himself, who started the fire in cancer genetics, is now criticizing the field for not living up to the expectations, stating that locating the genes that cause cancer has been “remarkably unhelpful”. Watson also acknowledges that targeting cancer metabolism is a more promising avenue than cancer genetics and that if he were to do it over again he would have focused his research on cancer biochemistry and metabolism. In the last 5-10 years, more and more researchers around the world are starting to think like Watson and therefore the field of cancer metabolism is experiencing a renaissance which is believed by many to be the final door to corner and defeat cancer.

However, in order to understand cancer metabolism, it is necessary to go back in time almost a century to what Otto Warburg already tried to tell us. Although the Warburg Effect is seen in the light of excessive and dysregulated glucose consumption, what struck Warburg the most was the aberrant production of lactate from cancer cells which lead Warburg to posit that the etiology of cancer was a mitochondrial injury leading to lactate production. These thoughts were not understood by most scientists during Warburg’s days and a century later most cancer researchers still don’t understand what lactate is.

A sample of DL-Lactic acid by LHcheM. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

A sample of DL-Lactic acid by LHcheM. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Nevertheless, back in Warburg’s days, lactate was studied by some of the most prominent scientists of the time. Already in 1857, Louis Pasteur described lactic acid as the result of microbial fermentation due to lack of oxygen. In 1907 Nobel laureate Frederick Hopkins and his colleague Walter Fletcher demonstrated that lactate accumulated when frog muscles were stimulated to contract, and that when fatigued muscles were placed in oxygen-rich environments, lactate disappeared. In 1920 Nobel Laureate Otto Meyerhof identified glycogen precursor to lactate formed in frog muscles electrically stimulated to fatigue with much of the lactate restored to glycogen during aerobic recovery. In 1923 another Nobel Laureate, Archibald Vivian (AV) Hill and his colleague Walter Morley Lupton described the term “O2 Debt” in which they linked lactate production during exercise to oxygen-limited lactate production. Subsequently, Warburg astutely described that lactate production in cancer cells was due to an injury to mitochondria, which we may call today mitochondrial dysfunction. However, neither the knowledge of genetics nor the sufficient technologies to study lactate metabolism were available to Warburg and his contemporaries during his time. Further, because of the stature of the first investigators in lactate, the concept of lactate production as a result of oxygen lack and as a waste product was immortalized in textbooks of physiology and biochemistry for about a century.

However, in the mid-1980s George Brooks from the University of California at Berkeley, decided to unbury lactate from the bottom of the ocean and embarked on a fascinating adventure to understand lactate and its role in skeletal muscle during exercise. Over the years, George Brooks has been able to prove that lactate is not a waste product but a highly active molecule, one of the most important gluconeogenic precursors, a major substrate for almost every cell in the body including the brain or the heart, a major regulator of intermediary metabolism, especially fatty acid metabolism, a highly active signaling molecule with hormone-like properties, and probably even a transcription factor.

When I first read about the Warburg Effect in cancer over two years ago, I was surprised to see that it was not about genetics but about metabolism. Nevertheless, I was more surprised when I saw that it was the main subject of my doctorate thesis although in skeletal muscle, we call it “cytosolic glycolysis” or simply “glycolysis” (under aerobic or anaerobic conditions). The players of glycolysis both in cancer and skeletal muscle are the same except that in cancer cells they are completely dysregulated probably by a primarily genetic dysregulation. In skeletal muscle, however, glycolysis players are perfectly regulated where in fact, despite being the largest structure in the body, skeletal muscle cancer (rhabdomyosarcoma) is rare and due to its embryonal nature it is usually encountered in children accounting only for ~3% of all cancers. The heart, which is the most oxidative form of muscle in the body with a great capacity to uptake lactate, barely ever develops cancer. Angiosarcomas are extremely rare and barely reported clinically as a primary tumor.

As experts in exercise metabolism and especially in glycolysis (“Warburg Effect”), lactate metabolism and skeletal muscle mitochondrial function, Brooks and I decided to take a crack at the Warburg Effect in cancer, and mainly, the role of its obligatory end product, lactate. Through our “Lactagenesis Hypothesis”, we decipher how lactate is probably the only metabolic compound involved and necessary as a master regulator in all main sequela for carcinogenesis. If dysregulated lactate production in glycolytic tumors can be haltered, most forms of cancer could be cured. Accordingly, therapies to limit and disrupt lactate exchange and signaling within, between and among cancer cells should be priorities for discovery.

Featured image credit: University of Northern Iowa by Drew Hays. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Lactate: the forgotten cancer master regulator appeared first on OUPblog.

Marcel Duchamp’s most political work of art

A hundred years ago last month, two of the most influential historical events of the twentieth century occurred within a span of three days. The first of these took place on 6 April 1917, when the United States declared war on Germany and, in doing so, thrust the USA into a leading role on the world stage for the first time in its history. America and American foreign policy would be forever changed as the nation tasted imperial grandeur it would never again relinquish.

War led to the passage of espionage and sedition laws that restricted free speech and authorized government surveillance of private citizens. From this exigency, the national security state was born. So too was the military-industrial-entertainment complex, in which the armed forces, the federal government, corporate America, and the popular arts consciously and unconsciously conspired to transform the nation into a powerhouse unlike any in the history of mankind.

The other earth-rattling event occurred three days later, on April 9, 1917, when an expatriate French artist named Marcel Duchamp affixed a false name (“R. Mutt”) to a white porcelain urinal that he had purchased in a Manhattan plumbing supply outfit and, under the droll title Fountain, submitted to the first annual exhibition of the American Society of Independent Artists.

The liberal members of the Society had proudly announced that this was to be an egalitarian exhibition, with no judges, juries, or rejections; anyone who paid the nominal membership dues and entry fee would be guaranteed a place. Duchamp, under his pseudonym, paid the required fees, but his submission was rejected all the same, and with vehement indignation, because a signed, store-bought plumbing fixture could not be countenanced as “art.”

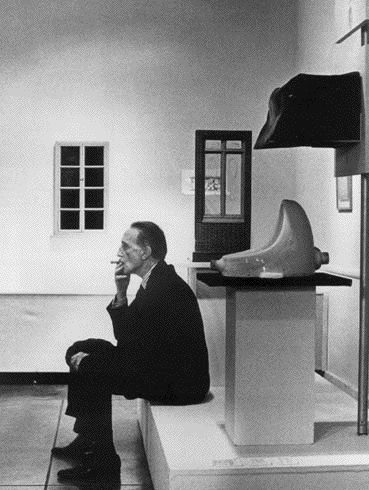

Duchamp at the Fountai. Photo by Salim Virji. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Duchamp at the Fountai. Photo by Salim Virji. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.The organizers of the exhibition did not know that the urbane Frenchman who had gained international notoriety four years earlier at the Armory Show for his cubo-futurist painting Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 was among them that spring morning when the urinal was unpacked from its shipping crate. Thus they did not hold back in their scorn.

They rightly understood that Mutt (even the name was intended as an insult) was “pissing” on their time-honored beliefs about artistic authenticity, originality, and beauty, insolently demanding reconsideration of such beliefs. As one of his few allies of the time contended, “Whether Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view—created a new thought for that object.”

Surprisingly, no one ever made a direct connection between America’s declaration of war on Germany on 6 April 1917, and Duchamp’s declaration of war on traditional art and its value systems a mere two or three days later. Surely that has something to do with the still-commanding formalism in the art world, especially the elite, theoretically dominated art world, preventing us from grasping how the most acclaimed artwork of the twentieth century, famous for its Dada overturning of conventional aesthetics, could also and at the same time, have been a blistering counter-response to America’s brash entrance into the global war.

Another reason the highly political nature of Fountain, its “obscene” comment on the obscene nature of the war, has long gone unrecognized is that Duchamp, as an artist, gentleman, and dandy, cultivated a persona of impeccable detachment. The persistence of that persona in the half century since the artist’s death in 1968 has made it difficult to regard him as anything but perfectly suave and preternaturally untroubled by the external political world erupting into flames around him.

Mythology aside, Duchamp was anything but indifferent about the politics of the moment. He despised the war in particular, having fled his homeland two years earlier because, as he explained in an interview, “Everywhere the talk turned upon war. Nothing but war was talked about from morning until night. In such an atmosphere, especially for one who holds war to be an abomination, it may readily be conceived existence was heavy and dull.” A grand understatement!

Now, in 1917, with his adopted homeland plunging hysterically into a conflict he thought barbarous and unnecessary, Duchamp wanted to take the mickey out of two intertwined organizations. One was the state, with its pretentious and hypocritical claim that it was going to war against Germany to “make the world safe for democracy,” when, as a member of the Left, he believed quite the contrary. The other was the so-called progressive art world that self-flatteringly claimed to be democratic and non-hierarchical in its support of artists and new forms of art but was in fact not that way at all.

Fountain was the insolent response of a resident alien to his adopted homeland’s vulgar and disgusting embrace of war. It was a “piss on both your houses” gesture of antagonism.

The gallery owner, photographer, and champion of avant-garde art Alfred Stieglitz understood it as such when he had the rejected Fountain hauled up to his Gallery 291, where he photographed it for posterity (the original readymade disappeared almost immediately after that, probably discarded by Duchamp as no longer serving a need). In choosing a backdrop for the photograph, the art impresario could have used a plain white background, as would become typical later in the century for displaying sculptural objects in pristine isolation from the world around them—the white cube approach. Or he could have photographed it in front of one of the semi-abstract paintings of the newly discovered artist to whom he as giving a solo exhibition at the time, Georgia O’Keeffe.

Instead, the gallery owner photographed it against an unsold canvas by his protégé Marsden Hartley, who, in love with a German cavalry officer, had lived in Berlin on the eve of the war and painted a series of radiant quasi-abstractions of Prussian horsemen in tight white breeches parading on imperial review. Stielgitz “posed” Fountain directly in front of a Hartley oil painting called Warriors, establishing a powerful, if highly ambiguous, link between militarism, as celebrated by the American modernist painter, America’s declaration of war against Germany, and Duchamp’s declaration of war against the art establishment. The urinal is placed in front of Warriors in such a way as to invite the viewer to urinate on militancy, be it German, American, or any other kind.

Several years earlier, the Italian poet F. T. Marinetti, in his first Futurist manifesto, had proclaimed that war is good because it purifies society; he called it the “the hygiene of the state.” Strange as it may seem to us today, many of Marinetti’s fellow artists and intellectuals looked forward to the Great War, naively believing it would overturn stale, outmoded ways of thinking, wash away the sediments of the past, and launch society into a better, purer, more ideal future.

Fountain rejected futurist rhetoric. It condemned Wilsonian progressivism, too, and spat on—or, more specifically, pissed on—idealism of any sort, be it political, military, or aesthetic.

Thus the two birthdays we are about to commemorate—that of America’s military-industrial complex, as inaugurated by the nation’s leap into the fray of the First World War, and of the Duchampian strain of modern art, as marked by the submission and rejection of Fountain—are twinned episodes in the lives we collectively lead. To understand how Fountain, in the context of its electrifying historical moment, was not only anti-art but also anti-war is to help artists today better understand the extent to which making art can, or cannot, be an alternative to making war.

Featured image: Fountain by Marcel Duchamp. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Marcel Duchamp’s most political work of art appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers