Oxford University Press's Blog, page 361

May 29, 2017

Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice: an audio guide

2017 marks the 200th anniversary of Jane Austen’s death. In honor of Austen, listen to Fiona Stafford of Somerville College, Oxford, as she introduces and discusses Pride and Prejudice.

Pride and Prejudice has delighted generations of readers with its unforgettable cast of characters, carefully choreographed plot, and a hugely entertaining view of the world and its absurdities. With the arrival of eligible young men in their neighborhood, the lives of Mr. and Mrs. Bennet and their five daughters are turned inside out and upside down.

Featured image credit: “Morning Coffee” by Mira DeShazer. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice: an audio guide appeared first on OUPblog.

The International Day of UN Peacekeepers

The twenty-ninth of May marks the ‘International Day of UN Peacekeepers’. Today, there are approximately 100,000 UN peacekeepers deployed across the globe, and these individuals’ contribution to the restoration and maintenance of international peace and security – often undertaken in exceptionally difficult circumstances – must be acknowledged. However, recent sexual abuse and exploitation scandals involving UN peacekeepers (see, these three examples), and the less than exemplary response of the UN itself, have tarnished the reputation of the UN and individual peacekeeping forces, undermining their legitimacy and that of their mandate.

Moving forward, it is suggested that the UN should actively engage with international human rights law. This body of law provides an effective overall framework, capable of guiding the activities of UN Peace Support Operations (PSOs), and ensuring that these forces demonstrate international best practice. This blog will discuss why PSOs should think about human rights law, before briefly highlighting the role that human rights law could play with respect to detention operations and investigations.

Why UN PSOs should think about human rights law:

From an international legal perspective, it is widely accepted that UN PSOs are subject to obligations under human rights law. This applies to the PSO itself, as a subsidiary organ of the United Nations (see WHO and Egypt, para 37), and to individual Troop Contributing Countries (TCCs), who carry their States’ international obligations with them on deployment. To-date, however, there has been a discernible hesitancy to actively engage with human rights law. This must change.

“International Day of Peacekeepers” by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“International Day of Peacekeepers” by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.For those TCCs who have recognised a right of individual petition before human rights bodies, such as States Parties to the European Convention on Human Rights, or States that have made the necessary declaration in accordance with Article 34 of the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, human rights compliance is a very real requirement. This is a result of both the extraterritorial application of human rights law, and the fact that TCCs – and not just the UN – may be responsible for the actions of PSO forces (See, Jaloud paras. 149-51, Al-Jedda paras. 84-5, compare with Behrami and Behrami, para. 151).

For other States, it must be acknowledged that the possibility of real human rights scrutiny is remote. However, for a PSO force to function effectively all national contingents must work together. This means that all contributing States, and the Force Commander, must be aware of individual States’ human rights obligations, as this will affect the management of the mission. The issue is therefore one of interoperability. Just as military coalitions such as NATO must be aware of contributing State’s legal obligations, so that tasks can be allocated and operations planned to ensure legal compliance, so too must PSO forces be aware of TCCs’ human rights obligations.

Perhaps most importantly, however, and moving beyond strict legal and practical considerations, the UN’s role as an agent of the international community must be acknowledged. While the UN is not a human rights organisation per se, the UN is undeniably associated with the protection and promotion of human rights. If the UN is to maintain its credibility, impartiality, and legitimacy – elements essential to the fulfillment of PSO mandates – it must not only act in a human rights compliant manner, but it must also be seen to act in such in a manner. It is difficult, if not impossible, for PSOs to develop links with affected populations, or to convince actors to end human rights violations, while being themselves accused of violating human rights.

If the UN is to engage with human rights law, it must begin to more effectively incorporate human rights compliance into its mission planning and standard operating procedures. Human rights law will affect numerous components of a PSO’s activities, from the fulfilment of a protection of civilians mandate, to the use of force, or the planning of individual operations. For the purposes of this post, however, I will briefly focus on the detention and investigations. Detention is an issue that the UN has yet to consider from a human rights perspective, while engagement with human rights in the context of investigations could be of real practical assistance to the UN.

Detention:

It is inevitable that PSOs will be required to conduct some form of detention during operations. Detention is a central element of any response to internal disturbances or tensions, and is also essential for security reasons during hostilities. Indeed, if a UN force engages in hostilities, but does not conduct detention operations, serious questions relating to the protection of the right to life should be asked.

However, PSOs do not appear to have undertaken and implemented effective detention planning in order to ensure compliance with the requirements of international human rights law. For example, a core element of human rights law is the prohibition of arbitrary detention. To protect against arbitrariness an explicit legal basis for detention must be established. Satisfying this obligation is relatively straightforward, but to-date the UN Security Council Resolutions establishing PSOs have not addressed detention authority, and this is not a feature of the UN Model Status of Forces Agreement. It is therefore likely that any detention operation conducted by PSO forces will be arbitrary, and in violation of the right to liberty and security.

International human rights law also establishes explicit safeguards relating to the transfer of detainees from UN custody to the authorities of the host State. Human rights law expressly prohibits such transfer if there is a real risk of torture, or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Given the context in which PSOs inevitably operate, the possibility that detainees cannot be legally transferred to the host State must be considered, and the resultant implications for the PSO force thought through and planned for.

Investigations:

Recent sexual abuse scandals, and the UN’s inadequate response, have underscored the need for an effective investigative system. As the UN comes to terms with how it should move forward in this regard, international human rights law can be of real, practical assistance. For instance, human rights law details the steps necessary to the conduct of an effective investigation – including in difficult security environments (see Al-Skeini, paras. 161-67) – while associated requirements relating to public scrutiny can facilitate transparency vis-à-vis the affected community, thereby ensuring that justice is seen to be done, and helping to restore the UN’s legitimacy.

The UN and individual TCCs must begin to effectively engage with human rights, and to ensure that human rights requirements are fully incorporated into all stages of PSO design, generation and deployment. This is, of course, important both as a legal obligation for TCCs and as demonstrative of the UN’s commitment to human rights. Equally important, however, is the possibility that human rights law can be used to guide PSO activity, by providing an overall frame of reference, and much needed answers when it comes to addressing issues such as detention or investigations.

Featured image credit: “Flags before UN building”, by Yann Forget. CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The International Day of UN Peacekeepers appeared first on OUPblog.

May 28, 2017

Protecting half: a plan to save life on Earth

Recently, a number of the world’s leading scientists, indigenous leaders, and advocates have been engaged in something bold: asking exactly what is required to stop the mass extinction of life on Earth and save a living planet. And the answer, after numerous reviews of the evidence for what it would take to achieve comprehensive biodiversity conservation, has become clear: fully protect half the Earth (or more) in an interconnected way. The vision is bold because it far surpasses globally agreed upon targets for establishing nature reserves (which today are at 17%) and because rather than asking for what appears possible, it is asking for what is needed. In several advocacy communities, this goal has been coined “Nature Needs Half” (NNH) — a concept that is meant to be inclusive of people in its definition of nature as well as in its definition of protection. NNH acknowledges that nature can be conserved not only in government-run protected areas, but also on private lands and indigenous reserves.

Protecting half offers a grand vision—and endgame—under which all conservation efforts could rally. Such a grand plan is desperately needed. Many vertebrate species have vanished over the past five decades or have become critically endangered and the rate of extinction is accelerating. If habitat conversion continues unabated, key ecosystems could collapse, disrupting the biosphere upon which we all—humans and wildlife—depend. We need a grand solution, and until recently nobody had been bold enough to offer up what it would take to conserve the wealth of diversity on Earth.

With the vision in place—protect at least half the Earth in an interconnected way—we felt that two basic questions must be addressed:

1) Is the aspirational goal of protecting half of nature in the terrestrial realm possible?

2) Which half should be protected, and how much of it has already been conserved?

We tackled answering these two questions recently, and addressed just how feasible this grand vision of protecting half the Earth may be.

Hawaii waterfall by kuszapro. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Hawaii waterfall by kuszapro. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.After revising a map of the world’s 846 ecoregions, we determined how much habitat remains and how much is protected in each of these places. 98 ecoregions (12%) already have at least half of the land areas protected for the conservation of nature. Another 313 ecoregions fall short of half-protected but have sufficient unaltered habitat remaining to protect the target.

Further, our results were surprisingly positive for many of the world’s most species-rich regions in the subtropical and tropical forests. Covering only 14% of the Earth’s surface, this biome supports more than half of life on Earth and 140 of the ecoregions in this biome are either already half-protected or have sufficient habitat to do so.

In contrast, the situation is dire for a quarter of the world’s ecoregions, where an average of only 4% natural habitat remains. In these places, which include much of Madagascar, the Southeastern United States, and the mixed forests of China, we need to be focused on saving the last remnants in the short term and then undergoing a massive restoration over the next 30 years.

At the current rate, the amount of land under formal protection increases by about 4% per decade. If the rate of increase doubled to achieve 8 or 10% per decade, the goal, supported by a Global Deal for Nature, could be within reach. This should be feasible if we can help indigenous groups and private landowners in key areas to conserve their lands—and ultimately include these areas in the global protected area system.

While Nature Needs Half is a top down idea, it will only be achieved through bottom-up efforts, as conservation efforts will happen at local and community levels as people call on their leaders to conserve more land. Conservation should be achieved through careful planning while respecting rights, improving livelihoods, and sharing decision-making. As such, we are building a network that will support implementation of the grand vision through communications, mapping, and technical solutions, and by providing financial resources to places that are striving to protect half. The vision is aspirational, but with the right focus and dedication of resources, it is also feasible. Protecting half would pay incredible dividends for not just the other ten million life forms on planet Earth, but for future generations of people as well.

Photo by Harvey Locke on behalf of Nature Needs Half. Used with permission.

The post Protecting half: a plan to save life on Earth appeared first on OUPblog.

Brazil’s long-standing global aspirations: what is next?

Brazil has had a strong diplomatic tradition of being involved in international affairs, and has recently intensified its efforts to acquire more prominence and leverage in global issues. At the beginning of the 2000s, and under the leadership and popularity of former president ‘Lula’ da Silva, all eyes were on this country. Brazil was portrayed as a promising emerging market and rising power. The efforts to reduce poverty and inequality, as well as increasing democratic participation, were seen as the ideal complementary steps to set Brazil in the way to finally pass the threshold that separates developed from developing countries.

In the current decade, those high expectations have been questioned. The global economic crisis, shortcomings in the multilateral system, the falling of global commodity prices, slow national economic growth, corruption scandals, and social protests cast serious doubts on Brazil’s capacity to achieve its global ambitions, and even reconcile domestic and foreign policy goals. Since the controversial presidential impeachment of 2016, there is increasing contestation in domestic politics and uncertainty on foreign policy orientation. To what extent is Brazil able to effectively influence international negotiations and global governance mechanisms today? And how can we expect its influence to evolve in the future?

A tentative response has to consider these questions in a historical context. This will show that, as Brazil has attempted increase its presence in global affairs, its foreign policy agenda and policymaking process have become more diversified and complex; there have also been variations in the foreign policy discourse, not necessarily linked to changes in administration, and intense disagreements within Brazilian elites about foreign policy goals have become evident. Moreover, recognition of Brazil’s foreign policy ambitions and role by peers has increased but has also fluctuated. In addition, foreign policy engagements are being shaped by a highly unstable political context which tends to be neglected in most foreign policy analysis elsewhere. And the volatility of courses of actions is further exacerbated by the fact that foreign policymaking has to be negotiated with a number of actors outside of the Foreign Ministry on a regular basis.

As Brazil has attempted increase its presence in global affairs, its foreign policy agenda and policymaking process have become more diversified and complex.

Scholars have revisited assumptions and forecasts accordingly. In particular, the need to understand the unpredictability and open-ended transformations of these processes and scenarios has been acknowledged. Suggestions have been made to move beyond traditional accounts of rising powers and use the term “graduation dilemma” to understand Brazil’s long-standing search for a higher status in the international arena, and the contested nature of those ambitions and strategies today. The term represents a departure from existing studies as it conceptualises gaining global leverage as a process rather than an outcome, and observes the process in its fluidity and changing nature across policy areas and various faces of power. It takes into account material capacities and symbolic, interpretative elements too. Thus, rather than assuming a linear path to a higher status and the capacity to achieve goals, it seems helpful to explore the tensions surrounding foreign policy issues, the meaning that policymakers assign to different scenarios and strategies, the actual implementation (or lack of) of foreign policy decisions, and the unexpected paths that the present juncture might open. In this way, academic and policy analysis may unveil how state bureaucratic politics and domestic contestation affect Brazil’s international ambitions and actions, and how this impinges on negotiations with others at the international level.

A warning is in order: there is lack of consensus about the path to ‘graduation,’ as well as a gap between stated policy goals and implementation. Moreover, generalizations are futile and analyses are better-served by empirical observation of specific policy areas within foreign policy, such as security and involvement in peacekeeping missions, trade, democracy and human rights promotion, regional integration, transnational migration, international cooperation on education, and more. In some areas, there is considerable adaptation of foreign policy techniques to new realities and still more room for projecting the country’s influence in international affairs despite the apparent slowdown of its global rise. Overall, there is a clear challenge: to produce a conceptual refinement of foreign policy analysis and provide practitioners with novel insights that allow them to better cope with the uncertainty that instability brings to foreign policy strategies and negotiations.

Featured image credit: Christ the Redeemer by Lima Andruška. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Brazil’s long-standing global aspirations: what is next? appeared first on OUPblog.

Is suicide rationalizable? Evidence from Italian prisons.

After cancer and heart disease, suicide accounts for more years of life lost than any other cause of death, both in the United States and in Europe. In 2013 there were 41,149 suicides (12.6 every 100,000 inhabitants) in the US. To contextualize this number just think that the number of motor vehicle deaths was, in the same year, around 32,719 (10.3 every 100,000 inhabitants). Non-fatal injuries due to self-harm cost an estimated 2 billion dollars annually for medical care. Another 4.3 billion dollars is spent for indirect costs, such as lost wages and productivity. In the EU (at 27 member countries) statistics are very similar to those of the US: in 2010 there were around 60,000 suicides (12.3 every 100,000 inhabitants) and 38,119 motor vehicle deaths (7.8 every 100,000 inhabitants).

Since Durkheim’s famous study (Suicides, 1897) there has been extensive quantitative evidence in sociology, psychology, and psychiatry, as well as economics on the personal, social, and economic conditions associated with suicides.

The modern approach to suicide stresses its immorality and its connection with mental illness. This approach is in contrast with Greeks and Romans as well as Asian cultures (especially Japanese and Indian) that consider suicide to be a rational response to illness, disgrace, and other pain and suffering. David Hume, one of the most prominent British empiricists, and Arthur Schopenhauer, the famous German philosopher, looked upon suicide as a perfectly reasonable response to bad circumstances. Hume (Of Suicide, 1783) writes: “I believe that no man ever threw away life, while it was worth keeping” while Schopenhauer (Studies in Pessimism,1891) says: “It will generally be found that, as soon as the terrors of life reach the point at which they outweigh the terrors of death, a man will put an end to his life.”

Economists have tried to rationalize the decision to commit suicides, looking at the correlation with contemporaneous socio-economic factors being unable to identify a causal link so far. In particular, they have analyzed social contagion (an emulation of someone else suicide), unemployment, income, economic recession, education (as an important determinant of income), age, gender, monetary incentives (e.g. insurance coverage), female labor force participation, alcohol consumption, divorce and marriage rates, social isolation, population density and trends, health and health care, cultural factors/norms (such as ethnicity, religion, social capital, or the social stigma that suicide may carry), homicide rates, geographical and climatic conditions, lifestyle, civil liberties and quality of government. Typically they have found a positive correlation between suicides and adverse economic conditions.

One of the main obstacles to identify a causal relationship is the difficulty to measure expectations about one’s future wellbeing.

expectations and uncertainty about future conditions play an essential role in the decision whether to commit suicide in prison.

Starting from the Becker and Posner (Suicide: An Economic Approach, 2004) definition of rationality “people maximize their utility in a forward looking fashion taking account of the uncertainty of future events and the consequences of their action,” we tested whether there is a rational component in the decision to commit suicides. It is very hard to measure suicides and expectations because there are sparse data on suicides and there are no data on expectations. We mimicked a controlled experiment, looking at prisons, which are closed and isolated environments, where expectations can arguably be measured.

It is fairly easy to determine the inmates’ present discounted utility because it depends on how soon they will get released. To get out of jail is their main concern. We measured inmates’ changes in expectations using the timing of proposals of an unusual policy: nationwide large sentence reductions (collective pardons or amnesties). They must be proposed by a member of the Parliament and issued by the legislator (both the parliamentary chambers) with an absolute majority requirement of 2/3 (simple majority before 1992). When collective pardons and amnesties are granted, inmates with a residual sentence length of a given number of years, usually 2 or 3, are altogether released within a few weeks. In the last pardon, beginning of August 2006, more than 20,000 inmates were released within 1 week. Very few criminals are excluded from these sentence reductions (sexual offenses, mafia related crimes, terrorist attacks, and kidnapping). What we find is that suicide rates fall, on average, when new pardons are proposed. This means that suicide rates in Italian prisons particularly, do respond to changes in expectations about the time of release. Pardon proposals represent “good news” for inmates because they change the expectations of reduction in their sentence length.

We provided evidence that expectations and uncertainty about future conditions play an essential role in the decision whether to commit suicide in prison. Criminals who are spending time in prison exhibit forward looking behavior that proves that suicides have a rationalisable component. Furthermore we showed that criminals, who are often viewed as boundedly-rational or even irrational individuals are, indeed, rational.

Our results suggest that providing inmates with hope (perhaps through programs of “early release for good behavior”) can effectively reduce the risk of suicide in prison. Whether this can be generalized to the rest of the population remains an open question though it is highly likely that even there the decision to commit suicide contains a rational component. If this is the case those treatments that improves someone’s present wellbeing or future expected wellbeing could be effective in, to some extent, discouraging people from making the irreversible choice of killing themselves.

Featured image credit: silhouette of a man in window by Donald Tong. Public Domain via Pexels.

The post Is suicide rationalizable? Evidence from Italian prisons. appeared first on OUPblog.

May 27, 2017

Coincidences are underrated

“When a coincidence seems amazing, that’s because the human mind isn’t wired to naturally comprehend probability and statistics.” [Neil deGrasse Tyson] “Ralph, it’s remarkable that you should call. I was just thinking about you. It must be ESP.” Woman using telephone, c. 1910 “Candlestick style” phone. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Ralph, it’s remarkable that you should call. I was just thinking about you. It must be ESP.” Woman using telephone, c. 1910 “Candlestick style” phone. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The unreasonable popularity of pseudosciences such as ESP or astrology often stems from personal experience. We’ve all had that “Ralph” phone call or some other happening that seems well beyond the range of normal probability, at least according to what we consider to be common sense. But how accurately does common sense forecast probabilities and how much of it is fuzzy math? As we will see, fuzzy math holds its own.

Let’s try to de-fuzz the math a bit, starting with a classic example: the birthday problem. Perhaps you’ve encountered this problem in a math class that dealt with probabilities. In a group of people, what is the probability that two people would have the same birthday? Certainly it must depend on the size of the group. If we start with only two people, the chance would be one out of 365 – well, OK, one in 366 for leap years. If the group included more people, common sense might suggest that the probability would just increase linearly. So, to get a 50% chance, you might think it would take 183 people in the group. Wrong. That’s where common sense goes off the rails. It turns out that, in a group of only 23 people, the probability of two having the same birthday is 50%.

Birthday by profivideos. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Birthday by profivideos. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.Details of the logic required to arrive at this result are unnecessary here, but a clue is given by a group of three. The third person might match the birthday of either of the first two, so you might think to just double the first probability. But think about this from the inverse point of view. The probability of the second person’s birthday NOT matching the first is 364/365. But the third person could match either of the first two, so the probability of NOT matching is only 363/365. Since NOT matching is thus less probable, matching becomes more probable. Working this out involves a bit of number crunching, but math classes have calculators galore, and since many classes have 23 or more members, real data are available to support the probability calculation. As you can see, what we take to be common sense often yields inaccurate solutions.

Meanwhile, back at the “Ralph” problem, a math textbook might tackle this problem in terms of drawing different colored pebbles from a large urn. Let’s forego that approach, and set the “Ralph” problem in more realistic terms. Suppose you know N people. During the course of a single day, a number of those people, k, cross your mind on a purely random basis. For this illustration, let’s agree to ignore close relatives and friends that you think about almost every day. Next, a certain number of people, L, contact you in a given day by any means, including phone calls, e-mails and electronic messages, social media, snail mail, and random meetings.

Working though this problem (actually kind of fun if you like mathematical puzzles) yields an equation for the number of days that will elapse before the probability of getting a contact from someone you thought about reaches a given level. Of course, it depends on the variables N, k, and L, not the easiest quantities to obtain.

An estimate of N, the number of people that an average person knows, is available from various sources, and ranges from 200 to 1500, but k, the number of people one would think about is highly subjective, as is L, the number of contacts one receives in an average day. Yet, all these numbers are necessary to find an estimate of the time required for someone you thought about to contact you shortly after you thought about them. Unscientific surveys of students, neighbors, and friends produced numbers of thoughts from 10 to 100 and contacts from 5 to 30. Substituting these numbers into the appropriate derived equation and requiring that it be 90% probable yields a remarkable result. Such coincidences would happen anywhere from once a week to once every other month. Most people’s fuzzy math would probably have estimated a much longer time period.

If you are curious about how often you might expect such coincidences to occur, e-mail your numbers for N, k, and L to me and I’ll calculate the estimate for your case and send it to you.

Next time you get that “Ralph” call, rather than attributing it to ESP, you might tell Ralph: “Hey, I was just thinking about you, so you can consider yourself my coincidence of the month.”

Featured image: Ancient Planet by PIRO4D. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post Coincidences are underrated appeared first on OUPblog.

10 times that Jane Austen was ahead of her time

To some people the name ‘Jane Austen’ conjures up images of tea parties, stuffy fashions, and high-society events where women are swept off their feet by dashing gentlemen. But despite these widespread perceptions, Austen is an author equally celebrated for her notoriously sharp mind, frank descriptions, and acerbic social commentary. In the repressed atmosphere of Georgian England, Austen and her characters found many ways to circumvent the strict moral codes of the day. Through veiled satire and carefully constructed plots, social conventions were examined, re-assessed, and frequently mocked — often in a manner that was truly ahead of their times.

In light of these contradictions, we’ve highlighted 10 examples of Austen’s writing — all demonstrating her truly unique style. From post-truth sensibilities to taking time to slow down in our everyday lives, and from true love to the fight for female education, discover 10 times that Austen was ahead of the times…

Instead of gauging success through strict social conventions, Austen’s Edward Ferrars suggests that happiness is an entirely individual affair:

“I wish, as well as everybody else, to be perfectly happy; but, like everybody else it must be in my own way.” (Sense and Sensibility, Chapter XVII)

In reply, still on the topic of happiness but quite out-of-step with Georgian sensibilities, Austen’s Marianne wryly reminds us that material gains are no balm for the soul:

“What have wealth or grandeur to do with happiness?” (Sense and Sensibility, Chapter XVII)

From happiness to politics, Austen provides an important reminder for our twenty-first century ‘post-truth’ world. She notes that “seldom can it happen that something is not a little disguised, or a little mistaken”:

‘Back view of Jane Austen, Watercolor’, by Cassandra Austen (1804), Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

‘Back view of Jane Austen, Watercolor’, by Cassandra Austen (1804), Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.“Seldom, very seldom, does complete truth belong to any human disclosure.” (Emma, Chapter XIII)

Again, in words which can easily be applied to the modern age and our current ‘climate of fear’, Austen’s Mr. Gardiner berates the doom-mongers:

“Do not give way to useless alarm… though it is right to be prepared for the worst, there is no occasion to look on it as certain.” (Pride and Prejudice, Chapter V)

Pre-dating much of the nineteenth-century fight for women’s rights, Austen was a pioneer in suggesting that women should marry for love, with an intrinsic right to their own happiness:

“She had been forced into prudence in her youth, she learned romance as she grew older — the natural sequence of an unnatural beginning.” (Persuasion, Chapter IV)

Austen was not only a forerunner regarding marriage, but unusually for the times repeatedly highlighted the true intelligence, rationality, and wisdom (in the face of often difficult circumstances) of her female characters:

“I hate to hear you talking so… as if women were all fine ladies, instead of rational creatures.” (Persuasion, Chapter VIII)

In an increasingly separated society, and in a lesson just as applicable to cultural attitudes as it is to generational divides, Austen’s Mr Woodhouse reminds us that it is important to understand and respect the needs of all:

“One half of the world cannot understand the pleasures of the other.” (Emma, Chapter IX)

In an important message given the ubiquity of technology and social media in our day-to-day lives, Austen’s reminder to guard against the “busy nothings” is more imperative now than ever:

“From the time of their sitting down to table, it was a quick succession of busy nothings.” (Mansfield Park, Chapter X)

The fight for female education still continues today, and Austen was no stranger to the benefits of scholarly edification. In Mansfield Park, Mrs. Norris somewhat ironically argues for the case for female empowerment:

“Give a girl an education… and ten to one but she has the means of settling well.” (Mansfield Park, Chapter I)

And last but not least, in a letter to her sister, Cassandra Austen Jane Austen demonstrates the ever important skill of couching bad news!

“I will not say that your mulberry-trees are dead, but I am afraid they are not alive.” (Letter to Cassandra Austen, 31st May 1811)

Featured image credit: Jane Austen. CC0 public domain.

The post 10 times that Jane Austen was ahead of her time appeared first on OUPblog.

Unity without objecthood, in art and in natural language

What makes something we see or something we talk about a single thing, or simply a unit that we can identify and that we can distinguish from others and compare to them? For ordinary objects like trees, chairs, mountains, and lakes, the answer seems obvious. We regard something as an object if it has a form, that is, a shape, a structure, or at least boundaries, and it endures through time maintaining that form (more or less). An apple is what it is as long as maintains its form. Once it is cut into small pieces it is no longer an apple, but just ‘apple’. Some objects individuated by a form may be very temporary, for example waves and clouds.

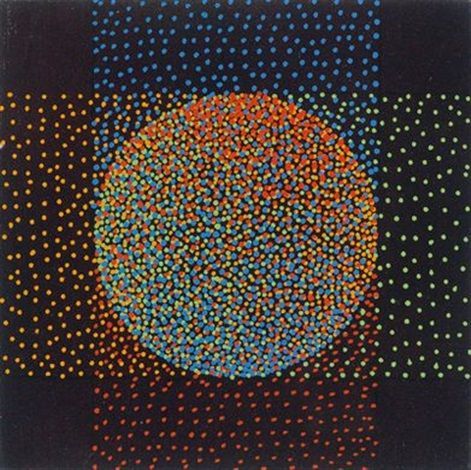

Apart from the question of the form that individuates objects, one can ask the weaker question of makes something a unit, given is presented to us, for example visually. Abstract art has addressed that question and optical art has played with our ways of perceiving something as a unit. Let us look at the paintings from the series “Alchemie” by the Argeninian op artist Julio Le Parc.

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Figure 2.

Figure 2. Figure 3.

Figure 3.Paintings from Le Parc’s “Alchemie” series, copyright Atelier Julio Le Parc. Used with permission.

Painting 1 clearly represents a single object, if unfamiliar, with a stable structure guaranteeing the objects endurance. In painting 2, we do not see an object that we would attribute an enduring structure to, but rather just something we may call a ‘unit’, something that has some form of integrity, in virtue of the closeness of light dots and a boundary separating it from an area with darker dots. In painting 3, again, we do not see objects, but various units. In fact, we can discriminate different units, depending on what we focus on, color or intensity of distribution of dots.

What makes us see something as a unit? In the last two paintings, the units are all parts of the painting that are maximal with respect to some property shared by dots (color of dots, color of background), or a relation among them, such as being connected with respect to a minimal distance. Such conditions define something as an integrated whole. Conditions defining an entity as an integrated whole or as having ‘gestalt’ are not always easy to make explicit, but they drive our perception in the way we individuate objects and we discriminate units in what is presented to us. Conditions of integrity help us discriminate an object or a unit, something that endures with a particular form or something that just has a form without thereby even being an object.

Language is not so different from painting. With language we can refer to objects with an enduring form, apples or houses, for example. The conditions of structure or form are generally expressed by the nouns we are using to refer to objects, more precisely by count nouns such as apple or house. But there is another important level of meaning where integrity conditions play a role, namely with complex constructions involving mass nouns and plurals. At that level, language operates in a way that is much closer to the art we just looked at. When we use mass nouns and plurals, we now longer can count on an enduring form being conveyed by the noun. Yet, we may refer to things that are divided into units, in the context of the linguistic information that goes along with the construction that is used. For example, when we refer to something as the rice, we do not differentiate between different portions of rice. However, when we refer to it as the white rice and the brown rice, we refer to it being divided into two units. Similarly, when we refer to the rice as the rice in the various dishes, we refer to the rice as being divided into as many units as there being dishes. In both cases, though, we do not refer to a plurality of objects. We do not refer to ‘two entities’, the white rice and the brown rice. The rice is never a thing and neither is the white rice or the brown rice, and the white rice and the brown rice are not two things, unlike an apple and a pear. The different ways of referring to the rice matter for the semantics of natural language, in particular the application and understanding of predicates. Thus (1a) does not sound very good, whereas (1b) is perfectly fine and has a single reading, and similarly (2a) does not sound very good, whereas (2b) is fine and has a single reading:

(1) a. ??? John compared the rice.

John compared the white and the brown rice.

(2) a. ??? John cannot distinguish the rice.

John cannot distinguish the rice in the various dishes.

(1b) means John compared the white rice to the brown rice, and (2b) means John cannot distinguish the rice in dish one from the rice in dish 2 and from the rice in dish 3 etc. It is not entirely impossible to get such readings also for (1a) and (2a), but these sentences also allow for other readings, depending on what sort of division of the rice into units is relevant in the context of the discourse. By contrast, when we use the predicate count instead of compare in (1a) (John counted the rice), a reading is entirely excluded on which contextually relevant portions are being counted.

The sensitivity of predicates like to compare and distinguish to the contextual division of a portion means that such predicates do not apply to entities or portions as such, or to pluralities. Rather when they apply to something like a portion of rice, they apply to it as divided into units given the information given by the descriptive content of the construction that is used or else nonlinguistic contextually relevant information.

What sorts of conditions are constitutive of the division of a portion into units? These are generally the same sorts of conditions as apply in the case of the painting: the units are maximal units of rice that share a contextually given property, such as the property of being white or the property of being brown in the case of (1b), and the property of being located in a particular dish in the case of (1b).

The same phenomena appear with plurals:

(3) a. John compared / cannot distinguish the students.

John compared / cannot distinguish the male student and the female students.

John compared the students in the different classes.

Compare applies to a plurality relative to a contextually given division into subpluralities, which is enforced by the use of a complex construction as in (3b) and (3c). Again pluralities are not single things, but they may count as units in the context.

Language also dislays unit-dissolving and unit-preventing modifiers, for example the adjectives whole, and individual in English:

(6) a. The whole collection is expensive.

John compared the individual students.

Whole in (6a) allows a distributive reading of expensive that would be impossible if only the count noun was used (the collection is expensive). Individual in (6b) prevents a reading on which proper subgroups are the object of comparison.

In natural language, as in abstract art, we thus see the importance of conditions of unity without objecthood. These conditions may be crucial for the understanding of what is said in the utterance of sentences, as just as they are crucial for the understanding or appreciation of a painting.

Featured image: painting by Atelier Julio Le Parc from the “Alchemie” series. Copyright Atelier Julio Le Parc. Used with permission.

The post Unity without objecthood, in art and in natural language appeared first on OUPblog.

May 26, 2017

The conflicts of Classical translation

Any translation is bound to be only partially faithful to the original. Translation is, as the Latin root of the word shows, transference from one language to another. It is not, or should not be, slavish imitation. The Italians have a saying: “Traduttore traditore”–“the translator is a traitor” – and one has to accept from the start that this is bound to be the case. The trick is to betray the original text as little as possible, but that always involves compromise. A translator balances on a tightrope between several conflicting demands. Every sentence that a translator comes across presents all of these demands in various proportions, and he or she has to find the right balance.

First, there is the conflict between over-translation and crib-style translation. How exactly should one echo the phraseology, word order, sentence structure, metaphors, and so on of the original? Though one can think of a number of supposed translations of ancient texts where the translators have imagined that they knew better than the original author what he was trying to say, it is the other extreme which is all too common in this field: over-literal translation – translation that reads like the first draft of a schoolchild’s exercise, or a 1950s’ phrasebook for Eastern European tourists. Astonishingly, such translations do still get published.

This was all very well in the days when most of the audience for such translations were familiar with the ancient language, and were even using them as cribs to help them through texts, but that is not the case today. Over-translation tends to underestimate the intelligence of the original author: if they had wanted those extra flourishes, they would have put them in. Crib-style translations tend to underestimate the intelligence of the reader, by assuming, for instance, that they have to have the same Greek word translated every time by the same English word – which is to assume that readers cannot recognize family resemblances between English concepts with different names.

A second potential conflict facing the translator is more metaphysical. It is possible to programme a computer these days to come up with translations that are accurate, grammatically correct … and total abominations! Why? Because computers can’t tell the difference between translationese and real English; they can’t sense the weight of words and place them accordingly within a sentence, which is weighed within a paragraph, which is weighed within a chapter. Most surviving classical authors were capable of achieving this kind of harmony (as we may call it), and their translators therefore have to try to encompass as well. This is where sensitivity to English (or any other modern language) is as important to the translator as sensitivity to ancient languages. It is no embarrassment to a translator to absorb the English of Cormac McCarthy as well as Charles Dickens, of Robert B. Parker as well as Robert Graves. Extremely wide reading in both languages is an absolute prerequisite for a translator.

Image Credit: ‘Dog, Sleep, Sleeping’ by JuliaMussarelli, CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Image Credit: ‘Dog, Sleep, Sleeping’ by JuliaMussarelli, CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.A third balancing act lies between the two languages and cultures involved. If one translates aulos as “flute” rather than “reed pipe”, how misleading is it? Should one use words such as “penniless” or “quixotic”, given that at the time there were no pennies and no Cervantes? There’s an ancient Greek proverb which says “Don’t move something bad when it’s fine where it is.” This clearly means the same as “Let sleeping dogs lie” – but should one use this contemporary English version? What connotations might it trigger in the English reader’s mind? If language consisted entirely of publicly accessible objects such as tables and dogs, a translator’s life would be much easier. But a great deal of language consists of abstract terms and ways of attempting to express less publicly available feelings and thoughts, conditioned by an alien culture.

From a personal perspective, my purpose as a translator is to perpetuate some of the greatest European books ever written. I try, then, to make them as readable and enjoyable by a modern audience as I can – obviously while sacrificing accuracy as little as possible. This is a controversial position. Many working academics prefer translators to produce more literal translations, which they can then annotate, so to speak, to their classes in their lectures. I would enjoy reading responses from both lay readers, untrained in the original languages, from students, and from working teachers at all levels.

Featured Image Credit: ‘Wonderland Walker 2’ by kevint3141, CC by –SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons .

The post The conflicts of Classical translation appeared first on OUPblog.

Remembering veterans

With Memorial Day in the U.S. right around the corner, we’re bringing you a glimpse into a handful of oral history projects focused on collecting and preserving the memories of military veterans. Check them out, and mention your favorite projects in the comments below.

The Wisconsin Veterans Museum Oral History Program

The Wisconsin Veterans Museum (WVM)’s mission is to affirm, commemorate, and acknowledge the achievements and sacrifices of Wisconsin veterans in America’s military past. The WVM Oral History Program, which I have had the privilege of coordinating for over three years, honors those who served by recording and preserving their stories and experiences. Since 1994 our staff members and volunteers have conducted and collected over 2,100 interviews with veterans from around the state. Our collection represents all branches and all conflicts and eras since World War I to the present day. The Oral History Program focuses not only on creating a record of our veteran-narrators’ stories, but also on the preservation and accessibility of these narratives for future generations. The interviews are housed in WVM’s Research Center, where they are easily available to teachers, students, researchers, the media, and veterans groups. In addition, great strides are being made to make the interviews, both the recordings and associated transcripts, more discoverable and accessible through WVM’s website. We also strive to promote these primary sources by using them for public programming, exhibits, and educational activities.

WVM recently opened a new temporary exhibit entitled “WWI Beyond the Trenches: Stories From The Front.” Throughout the next two years we will be offering programming and events that feature Wisconsin’s contribution to the Great War – in which 122,000 people from Wisconsin served. As part of these efforts, we have been working on ways to showcase our small but exciting collection of World War I oral history interviews:

Eleven of our World War I interviews are accessible online via our website’s Featured Interviews page. We recently started using OHMS as an access tool and this is the third collection that we’ve featured through OHMS.

Excerpts from several of the interviews are available to listen to in the new exhibit through an audio device that visitors can pick up before going into the gallery.

We have partnered with the producer of Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life to feature stories and audio from our collections on the show. We will be these airing stories through next November.

We are always looking for new ways to use and feature all of our interviews and to inspire others to do so as well. These narratives put a human, individual face on war and military service, so that visitors and researchers get an opportunity to meet these veterans and perhaps put themselves in their shoes.

Learn more about the WVM Oral History Program, and search the Collection.

–Ellen Brooks, Oral Historian, Wisconsin Veterans Museum

U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center’s Oral History Programs

In 1970 General William Westmoreland started the Senior Officer Oral History Program (SOOHP) to provide insights into the command and management techniques utilized by senior Army officers in key positions and to further scholarly research on the history of the U.S. Army. Today that program is spearheaded by the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center (USAHEC) in Carlisle, Pennsylvania and has since inspired the creation of three additional oral history programs, all of which capture the history of U.S. Army Soldiers in their own words.

The USAHEC is the Army’s preeminent archive, academic library, and research complex with expansive historical resources for Soldiers, researchers, and visitors. The organization, originally founded in 1969 as the U.S. Army Military History Institute (USAMHI), now includes that original organization as a subordinate division and is an important part of the U.S. Army War College (USAWC), which educates and develops leaders for service at the strategic level while advancing knowledge in the global application of Landpower. As the USAHEC aims to preserve the stories of all Soldiers, it makes sense that these oral history programs are an important focus of the institution. Once completed, all interview transcripts are placed in the archives of the USAMHI for use by USAWC students and faculty, researchers, headquarters, agencies, and the general public in accordance with interview access agreements and the USAHEC’s mission of making contemporary and historical materials available.

The purpose of the original oral history program, SOOHP, is three fold. First, to record the management and leadership techniques of senior Army officers and Department of the Army Civilians and their recollections and opinions on key persons, events, and decisions. Second, to provide a comprehensive biography of senior leaders for the historical record, or to record information about significant events, ideas, and decisions as seen from the perspectives of key participants. Lastly, to supplement written records, clarify obscure aspects of significant events and decisions, and provide material where manuscript or printed sources are inadequate or unavailable.

Learn more about the project, and how to get involved, through the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center’s website.

–LTC (R) Brent C. Bankus, Chief, Oral History Branch, U.S. Army Military History Institute

University of Oregon Veterans Oral History Project

The University of Oregon Veterans Oral History Project began about a decade ago when I realized that our university archive had virtually nothing documenting the experience of our students who had served in the military. This was at a time when the numbers of veterans at the university was increasing quite substantially. Because most of my teaching is in the field of military history, I have always had significant numbers of veterans in my classes. My thinking was quite simple: why not try to document the experiences of an important part of our student body?

I had read somewhere (probably Donald Ritchie’s handbook) that oral histories that are not transcribed almost always go unused. I knew that I could not pay for transcriptions, so I decided that I would offer a class that would serve as a platform for the project. Students would do the work of both interviewing our veterans and, equally important, transcribing those interviews. What started in my mind primarily as a documentary project thus developed both documentary and pedagogical aims. Over the last six years we have interviewed about one hundred twenty-five servicemen and women; as of this writing about fifty of those interviews are available via the university library’s website.

Probably the biggest practical difficulty I have faced with the project is the recruitment of veterans, either to participate in the class or to be interviewed. When I talk to people about interviewing, one of objections I often get is, “You don’t want to interview me; I didn’t do anything interesting.” What they usually mean by “not interesting” is “I didn’t see combat.” Even soldiers who served in combat zones but whose job was in a support capacity will sometimes tell me that.

The entire point of the project, however, is to document the full range of experience in the services. Our motto is “anytime, anyplace, anywhere, any job.” Many veterans appreciate the fact that the project offers public recognition of military service, not just the service of those who happened to serve in places of danger, but of anyone who served: any rank, anytime, anyplace. The rank, I think, is especially important. Most of those we interview were enlisted. They are used to what we might think of as generic recognition of their service – in the way that, say, we “honor” those who served and sometimes give them special benefits and recognition. What I think those who participate especially like about this project is the way it personalizes the service of those whose service might otherwise fade into anonymity.

As a result, how I view the project has changed. I originally saw it primarily as a documentary project; today I also regard it as a kind of online memorial that allows veterans to present their service as they want it presented to and recognized by the wider public.

Read more about the project, and explore the archive.

–Alex Dracobly, Senior Instructor II, Department of History, University of Oregon

Chime into the discussion in the comments below or on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or Google+.

Featured image credit: “Remember” by Ian Sane CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Remembering veterans appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers