Oxford University Press's Blog, page 362

May 26, 2017

Responsibility and attribution: Criminal law and film

Many of us have been intrigued this year by two powerful films which explore the difficulty of escaping a troubled past. In Oscar-winning Moonlight, we gradually discover why a small African-American boy is picked on as ‘different’ by his classmates, and follow his path from school-yard harassment and violence through drug dealing, a prison term and a painful achievement of liberation which nonetheless leaves the scars of the past deeply etched on his personality. In Manchester by the Sea, a man is haunted by the terrible consequences of a past mistake for which he is unable to forgive himself. Adding to his misery is the fact that many of his neighbors, unwilling to consign his tragedy to the past, shun or even taunt him. Yet bleaker than Moonlight, such resolution as the main character achieves consists in coming to terms with the fact that his ability to transcend the past is – notwithstanding a fair array of opportunities and acts of kindness – strictly limited.

Each of these films convey a vivid sense of how deeply human choices are shaped by history and context – and of how hard it can be to escape the social opprobrium, as well as the sense of personal failure, which comes with having stepped outside established social conventions. These themes may seem far removed from questions about the nature of criminal responsibility, but they are in fact exemplary of the way in which ideas of responsibility for crime have changed since the eighteenth century. In particular, the notion that what grounds criminal responsibility is a judgment of bad character – judging a person by the company they keep, identifying bad apples, giving a dog a bad name – have enjoyed a revival, notably Britain and the United States, in the late twentieth century, with troubling consequences for the quality of criminal justice.

While multiple patterns of responsibility-attribution in criminal law can be discerned throughout the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries, we can nonetheless discern some broad trends in the alignment of these different patterns. Practices of criminal responsibility-attribution have long exhibited a concern with some combination of character, capacity, and outcome: with ‘character’ standing in for a particular conception of how criminal evaluation attaches to persons and relates to identity; ‘capacity’ standing in for the concern with agency, choice, and personal autonomy; and outcome standing in for the concern with the social harms produced by crime. In recent years, a pattern founded in assessments of risk has also emerged.

Squad Car by Unsplash. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Squad Car by Unsplash. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.In the eighteenth century, criminal law was dominated by character and outcome responsibility; but the former was gradually displaced during the modernization of criminal justice in the nineteenth century and early twentieth centuries. For much for the twentieth century, English criminal justice assumed a capable, responsible subject whose agency could be deployed in the service of reform, rehabilitation, culturally legitimated within a ‘civilized’ scientific discourse, as well as efforts at social inclusion. This system however began to be disrupted in the latter part of the twentieth century with the increasing politicization of criminal justice and an intensified focus on insecurity. This period saw the emergence of a new alignment of principles, with capacity responsibility still occupying a secure role among core criminal offences, but a new discourse of responsibility founded in the presentation of risk promoting a hybrid practice of responsibility-attribution based on a combination of putative outcome and a new sense of bad character not as sinfulness but rather as the status of presenting risk or being ‘dangerous.’

Arguably driven, not only by the feelings of insecurity associated with life in late modern societies but also by rapidly developing technologies of risk assessment in medicine, psychiatry, geography, and demography, this new hybrid form of character responsibility has been particularly evident in the areas of both terrorism and drug regulation, in the revival of status offences, and in the expansion of preventive justice through inchoate and ‘pre-inchoate’ offences. Indeed the revival of ‘character’ in contemporary criminal justice might be seen as the criminal law manifestation of what David Garland has called ‘the culture of control’: a reverberation of anxiety in a world marked by renewed economic and social insecurity, and one in which some countries have manifested an impulse to ever greater criminalization and penal harshness. These developments have been facilitated by the dramatic rise in the discretionary power of police and prosecutors accorded by the emergence of plea-bargaining as a fundamental mechanism in criminal justice. Moreover plea-bargaining might justly stand as the key symbol of contemporary criminal justice: at once subject to the formal consent of individual, ‘responsible’ offenders, yet embracing discretionary practices founded on unstated assumptions of dangerous-ness or bad character; rendering an extensive system of regulatory criminalization affordable while at the same time preserving an aura of constitutional propriety and respect for individual responsibility. Further examples of character-based responsibility –attribution include mandatory sentencing laws applying to particular categories of ‘dangerous’ offender, sex offender notification requirements and probation orders based on risk factors.

Moonlight and Manchester by the Sea therefore tap into an aspect of the contemporary zeitgeist which is of key significance to criminal law. Indeed the resources of popular culture have a great deal to tell us about the ways in which our formal practices of blame and punishment speak to, and are shaped by, deeper social currents. For example, it is also possible to draw on novels to illuminate and explain the gradual marginalization of women in the English criminal process. In the early eighteenth century, Daniel Defoe found it natural to write a novel whose heroine was a sexually adventurous, socially marginal property offender. Only half a century later, this would have been next to unthinkable. One might think of the disappearance of Moll Flanders, and her supersession in the annals of literary female offenders in the realist tradition by heroines like Tess of the d’Urbervilles, as a metaphor for fundamental changes in ideas of self-hood, gender and social order in eighteenth and nineteenth century England. One can draw on law, literature, philosophy and social and economic history to show how these broad changes underpinned a radical shift in mechanisms of responsibility-attribution, with decisive implications for the criminalization of women.

In a nutshell, it may have been easier to insert women into the (of course highly gendered) conceptions of criminal character which drove early eighteenth century attribution practices than to accommodate them within a conception of responsibility as founded in choice and capacity – a framework which was moreover emerging just as the acceptance of women’s capacity and entitlement to exercise their agency was becoming more constrained.

Featured image credit: Defense by diegoattorney. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Responsibility and attribution: Criminal law and film appeared first on OUPblog.

Pandemics in the age of Trump

If Donald Trump’s administration maintains its commitments to stoking nationalism, reducing foreign aid, and ignoring or denying science, the United States and the world will be increasingly vulnerable to pandemics.

When these positions are reversed—that is, when foreign aid is increased; when, in times of pandemics, national interests are subservient to global cooperation; and when science and evidence are our guides—great strides have been made in ridding the world of epidemic and pandemic diseases and relieving the suffering felt by millions. History is not a blueprint for future action—history, after all, never offers perfect analogies. However, there is little dispute among historians of medicine and science that the past has taught us a lot about what works and what doesn’t.

When it comes to pandemic disease focusing on nationalist interests is exactly the wrong approach to take. But during the height of the Ebola crisis in 2014, in a series of Tweets, that’s exactly what Donald Trump advocated—he called President Obama “psycho” for not stopping all flights from West Africa. Fomenting fear and taking an isolationist position is reckless and will put many millions at risk. It’s been clear for centuries that taking a nation-centric approach to pandemic disease is fruitless. Take a look at cholera in the nineteenth century. When it first appeared in Europe in the early 1830s, Russia attempted to close its borders—among other measures, soldiers formed a human wall in an attempt to stop cholera from entering the country. While it was surely a show of force, and demonstrated the country’s military might, as a tactic against cholera it was utterly useless. As global travel sped up with advances in rail and steamship technology, it became clear that cholera was a global concern and focusing on it as a national problem would not work. Early on this often meant restricting travel from heavily effected countries—often in xenophobic form.

At the 1872 international sanitary conference called to cooperate on cholera, the Italian delegate said: “We have to stop that cursed traveller who lives in India, everyone knows it, from taking his trips; at least we have to stop its progress as closely as possible to its departure point.” This kind of ethnocentrism was always present in discussions of disease control, and as long as international cooperation focused solely on immigration restrictions, cholera kept coming. But as medical knowledge of cholera and plague (which erupted in pandemic form in the 1890s and 1910s) became more sophisticated, control of pandemic disease increasingly followed more scientific routes. It became less about labeling people ‘unclean’ or ‘naturally prone to illness’ and more about greater efforts at instituting sanitary measures, working on vector control, and increasing disease surveillance. To insure that the next Ebola epidemic does not spread to the United States, to say nothing of West Africa and the rest of the world, the US must commit itself to bolstering health systems in places like Liberia and Sierra Leone. The US will only be safe from pandemic threats once robust health systems exist in the places most likely to be sources of pandemic diseases.

USG/FHI/PEPFAR Stands at the Fair, demonstrating Ghana and United States partnership to fight HIV/AIDS by official photographer of the U.S. Embassy in Ghana. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

USG/FHI/PEPFAR Stands at the Fair, demonstrating Ghana and United States partnership to fight HIV/AIDS by official photographer of the U.S. Embassy in Ghana. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.But controlling pandemic disease cannot be done if drastic cuts in foreign aid and basic scientific research are made. The massive increase in foreign aid directed towards HIV/AIDS by Republican President George W. Bush has arguably done more to combat the pandemic than any other single initiative. When Bush announced the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) on 28 January 2003, during his State of the Union Address, he signaled a strong US commitment to the disease. As Bush said: “AIDS can be prevented….Seldom has history offered a greater opportunity to do so much for so many. . . . [T]o meet a severe and urgent crisis abroad, tonight I propose the Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief—a work of mercy beyond all current international efforts to help the people of Africa. . . . I ask the Congress to commit $15 billion over the next five years…to turn the tide against AIDS.” This unprecedented program has saved many lives. Recently, however, the new administration has wondered: “Is PEPFAR worth the massive investment when there are so many security concerns in Africa? Is PEPFAR becoming a massive, international entitlement program?”

The US now seems poised to relinquish its leadership role. In America First: A Budget Blueprint to Make America Great Again, President Trump wrote that the US must make “deep cuts to foreign aid. It is time to prioritize the security and well-being of Americans, and to ask the rest of the world to step up and pay its fair share.” The potentially good news is that “America First” does say that PEPFAR and the Global Fund won’t be affected by the “deep cuts”—for now. But with the overall foreign aid budget to be cut by just over 30%, other key components in the US’s global health armamentarium, however, are not as lucky. The US Agency for International AID will have its budget slashed. And the Fogarty International Center at the National Institutes of Health—whose mission statement reads: “To protect the health and safety of Americans, Fogarty programs build scientific expertise in developing countries, ensuring there is local capacity to detect and address pandemics at their point of origin; accelerate scientific discovery; and provide national and international health leadership”—will be eliminated. Weakening developing countries’ capacity to respond to burgeoning pandemics will put the US and the world at risk.

It’s impossible to know exactly what the new administration is going to do. What does seem clear is that there is little concern for shoring up the basics of pandemic preparedness: investing in science and insuring that developing countries have adequate resources.

Featured image credit: Syringe, World medicine by qimono. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Pandemics in the age of Trump appeared first on OUPblog.

May 25, 2017

Police violence: a risk factor for psychosis

Police victimization of US civilians has moved from the shadows to the spotlight following the widespread adaptation of smartphone technology and rapid availability of video footage through social media. The American Public Health Association recently issued a policy statement outlining the putative health and mental health costs of police violence, and declared the need to increase efforts towards understanding and preventing the effects of such victimization. The Survey of Police-Public Encounters was conducted to provide empirical data to guide this discussion, and found an elevated rate of various mental health outcomes among people exposed to police victimization. A recent report specifically addressed the increased prevalence of psychotic experiences among people who report exposure to various forms of police violence. The following reflects on some frequently asked questions regarding this subject.

What is defined as police violence, abuse, or victimization?

These terms refer to the victimization of civilians by police officers that goes beyond the use of reasonable force. Reasonable force itself is a highly debatable term, as the rates of violence considered “reasonable” vary widely between countries (for example, police killings of civilians are exceedingly rare in Europe, even in situations where such action would be considered justifiable in the United States). In addition to physical violence, police abuse may also include sexual violence (ranging public strip searches to assault), psychological abuse (e.g., discriminatory language and threats), or neglect, in which officers fail to respond to a crime quickly or properly, thereby indirectly exposing civilians to violence.

Is police abuse a common problem in the United States?

The prevalence of police violence in the United States has been difficult to estimate due to varying reporting standards across states and across police departments. In the Survey of Police-Public Encounters, a standardized measure of community-reported police abuse was developed in order to estimate prevalence in four US cities. The lifetime prevalence rates of police abuse among survey respondents (adult residents of Baltimore, New York City, Philadelphia, and Washington D.C.; N=1615) were 6.1% for physical violence, 3.3% for physical violence with a weapon, 2.8% for sexual violence, 18.6% for psychological abuse, and 18.8% for neglect.

Police cars by diegoparra. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Police cars by diegoparra. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.Why would police violence be linked to mental health and, in particular, psychosis?

There is substantial evidence that stress, trauma, and violence exposure are associated with a broad range of mental health outcomes. People with psychotic disorders report very high rates of past and ongoing trauma exposure, and psychosis risk is particularly tied to interpersonal stressors. For example, the social defeat hypothesis posits that most environmental risk factors for psychosis share an underlying factor in which the exposed person is made to feel defeated and excluded from the majority group. Such effects may be exacerbated when the perpetrator is in a position of power relative to the victim, as in police-civilian interactions.

What are psychotic experiences?

Psychotic experiences resemble the core symptoms of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders (i.e., hallucinations and delusions), but are typically of lesser intensity, persistence, or associated functional impairment. Reported by approximately 7.2% of the general population, they typically remit over time and only rarely worsen sufficiently to develop into schizophrenia. Nonetheless, they are associated with a broad range of other clinical and functional outcomes. Importantly, they are easily measured and therefore serve as a useful proxy for studying risk factors associated with psychosis in epidemiological samples.

What new evidence links police violence to psychosis?

Data from the Survey of Police-Public Encounters provided the first evidence that exposure to police victimization is associated with psychotic experiences in a general population sample. Specifically, 14.4% of people reported psychotic experiences if they have never been exposed to police violence, compared to 31.0% of people who had been exposed to one type of police violence, ranging all the way up to 66.7% among those who reported all five police abuse sub-type exposures. While it has previously been known that people with schizophrenia are more likely to be mistreated by police officers, this association had not previously been studied with psychotic experiences. Sub-threshold psychotic experiences are unlikely to be of sufficient severity to draw police attention, suggesting that this association is due to police violence exposure leading to greater risk for psychosis (rather than the other way around).

What are potential next steps in this area of research?

The idea that police violence may cause psychosis, alluded to above, still needs to be born out in methodologically stronger longitudinal studies, which follow individuals over time with multiple assessments. We also need to start exploring ways to prevent such violent incidents from occurring at such a high rate or, if primary prevention proves unfeasible, explore ways to alleviate their impact on health and mental health.

What are the public health and clinical implications of these findings?

First, there is a significant need for more uniform data on the nature of police-public interactions across the country, both from the perspective of police departments and civilians. Second, efforts to reform police departments to prevent civilian victimization are critical, which may include greater accountability for police officer actions, the widespread adaptation of body cameras, improved psychological testing of new recruits, and reduced usage of invasive and inequitable practices such as “stop and frisk.” Third, it is reasonable to begin exploring alternatives to police intervention in responding to minor crimes, which may be better handled through community-based restorative justice practices.

Featured Image Credit: police by Matt Popovich. CC0 Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Police violence: a risk factor for psychosis appeared first on OUPblog.

Emerson’s canonization and the perils of sainthood

Ralph Waldo Emerson–who died 135 years ago in Concord, Massachusetts–was a victim of his own good reputation. Essayist, poet, lecturer, and purported leader of the American transcendental movement, he was known in his lifetime as the “Sage of Concord,” the “wisest American,” or (after one of his most famous early addresses) the “America Scholar.” The names stuck, and expectations ratcheted up accordingly, with one scholar claiming in an 1899 biography, “his whole life, however closely examined, shows no flaw of temper or of foible. It was serene and lovely to the end.” By the time of his bicentennial celebration in 1903, the firebrand once associated with the “latest form of infidelity” had become canonized, as Emerson scholar Wesley T. Mott puts it, as “Saint Waldo.”

It was, of course, a reputation impossible to live up to.

To be sure, some of his contemporaries idolized Emerson with a warmth exceeding veneration. Louisa May Alcott, whose family lived up the road from the Emersons, had a teenaged crush on the “great, good man, untempted and unspoiled by the world.” Henry James, Sr. (the father of the novelist) said in the 1860s that “if this man were only a woman, I should be sure to fall in love with him.” But as the philosopher George Santayana once said of Emerson and his admirers, “veneration for his person…had nothing to do with their understanding or acceptance of his opinions.” Chief among those “opinions” was his transcendental idealism, which struck many readers as an avoidance of the real world–okay for saints, not so good for philosophers. “Reality eluded him,” Santayana said flatly; his mind was “a fairyland of thoughts and fancies.” James regretted his friend’s constitutional ignorance of the “fierce warfare of good and evil.”

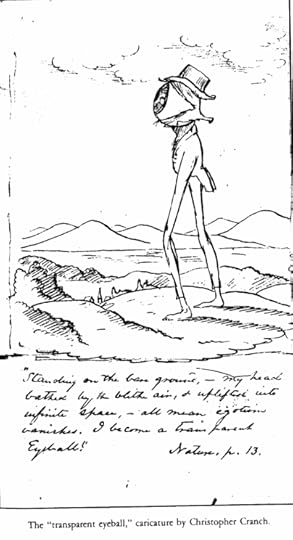

Caricature by Christopher Pearse Cranch illustrating Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “transparent eyeball” passage. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Caricature by Christopher Pearse Cranch illustrating Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “transparent eyeball” passage. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.In 2003 Emersonians gathered again in Boston and Concord, this time to commemorate his two-hundredth birthday with an academic conference and a private reception in the Emerson house hosted by his heirs. It was (I make no apologies) a moving event: we stepped across the velvet ropes, sat in Emerson’s reading chair, pulled family books off the shelves, saw his lecturing robe hanging in a bedroom closet.

But these sorts of commemorations tend to draw fire, especially for a slow-moving target like Emerson. John Updike, noted author and spoil-sport, weighed in with a 2003 article for the New Yorker, “Big Dead White Male,” that once again castigated Emerson for “waving aside evil” and “mak[ing] light of the world and its usual trials.” (As if the man who lost his father, his wife, two brothers, and first-born son—all before his fortieth birthday—had somehow escaped life’s sorrows.) In recent years we’ve seen similar appraisals: “Giving Emerson the Boot,” “Ralph Waldo Emerson, Big Talker” (both 2010), “Where’s Waldo? There is Less to the Bard of Concord than Meets the Eye” (2015), and “What is Emerson For?” (2016). Emerson comes off as a starry-eyed naïf with nothing to teach us beyond (in the words of a recent critic) “a set of contradictory, baffling, radical, reactionary ideas that offer no practical guidelines for actual human behavior.” If he’s such a sage, we ask, how about some answers?

Several years ago I wrote an account of the attempts to construct Emerson’s early reputation by biographers who “built their own Waldos” according to personal politics, family agendas, Gilded Age ideologies, and the commerce of publication. They challenged Emerson’s reputation as teacher-in-chief, and with good reason. He didn’t have much use for received wisdom unless it struck the individual soul as true. Lessons imposed are not lessons learned. Emerson insisted in his 1838 “Divinity School Address,” it is “not instruction, but provocation” that we can offer each other. “Trust thyself,” “Build your own world,” “Whoso would be a man, must be a nonconformist”–even his most hortatory life lessons may be seen as provocations in disguise, daring us to think, not just consent. His essays are dramatic monologues, performances of minds in turmoil, joy, despair, or rebellion. He was much more comfortable as the skeptic described in his 1850 essay “Montaigne,” always “try[ing] the case” rather than settling it.

In a little book on the American character, The Exploring Spirit (1976), the historian Daniel J. Boorstin distinguishes discoverers–those who know what they are looking for but not where to find it–from explorers, whose purpose is to set out for the unknown and see what turns up. Emerson was in Boorstin’s sense an explorer, following the terrain where it took him, fashioning metaphors to help make sense of the unfamiliar. For the “wisest American,” pushing us to search for ourselves the rich and complex frontiers of human experience was a calling more appropriate than sainthood.

Featured Image credit: Statue of Ralph Waldo Emerson by Frank Duvaneck at the Cincinnati Art Museum. Library of Congress, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Emerson’s canonization and the perils of sainthood appeared first on OUPblog.

Looking forward to Hay Festival 2017

Spring has sprung! For me this means a multitude of happenings – lambs in the fields, ducklings at work, and Hay festival! Each year I am lucky enough to take a week’s working holiday in the world famous book town that is Hay-on-Wye supporting, entertaining, and generally looking after our OUP authors. It also gets me up close and personal with media and publishing chums as we munch cake and drink coffee in the Green Room which positively bustles with activity each day.

This year Hay Festival is celebrating its 30th anniversary – cooked up round the kitchen table all those years ago it is now a global phenomenon. As part of their celebrations this year they have schedule 30 Reformation speakers, one of whom is Sarah Harper who will be focusing on ‘Ageing’. She will also be recording one of BBC Radio 3’s Essays.

The festival is very good at celebrating not only new writers but also young writers who ‘inspire and astonish’ and I am thrilled that they have selected Devi Sridhar who co-authored a recent book on global health with Chelsea Clinton to be one of the Hay 30!

Whilst I enjoy attending all our author’s events there are inevitably some highlights that I particularly wanted to draw attention to. Kicking off with the world leading moral philosopher Peter Singer in conversation with the fabulously entertaining Stephen Fry, and wrapping up at the end of the week with Eleanor Rosamund Barraclough whose immensely fascinating and entertaining book on Viking history will end a week of guaranteed entertainment.

If you, too, are planning to head to the Hay Festival in Wales at the end of this month then do take a look at the schedule below of our OUP author events:

Saturday 27 May

2.30pm, Peter Singer – Famine, Affluence, and Morality

Sunday 28 May

10am, Devi Sridhar – Governing Global Health

Monday 29 May

10am, Kathleen Taylor – The Fragile Brain

4pm, Sarah Harper – Reformation

8.30pm, David Allen Green – to join Bronwen Maddox, Terry Burns, and Vicky Pryce “How To Do Brexit”

Tuesday 30 May

1pm, Luciano Floridi – The Fourth Revolution

Wednesday 31 May

10am, Iwan Rhys Morus – Oxford Illustrated History of Science

2.30pm, Tony Verity – Homer

Thursday 1 June

10am, Catherine Barnard on European Law

2.30pm, Mark Maslin – The Cradle of Humanity

7pm, John Parrington – Redesigning Life

Friday 2 June

10am, Colin Jones – Smile Revolution

10am, Robin Hanson – Age of EM

4pm, Rhodri Jeffreys-Jones – We Know all About You

5.30pm, Leif Wenar – Blood Oil

5.30pm, Anabel Inge – The Making of a Salafi Muslim Woman

Saturday 3 June

10am, Barbara Sahakian & Julia Gottwald – Sex, Lies, and Brain Scans

7pm, Eleanor Rosamund Barraclough – Beyond the Northlands

Featured image credit: Hay on Wye literary festival by ‘Peter’. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Looking forward to Hay Festival 2017 appeared first on OUPblog.

May 24, 2017

From the life of words, part 1

From time to time, various organizations invite me to speak about the history of words. The main question I hear is why words change their meaning. Obviously, I have nothing new to say on this subject, for there is a chapter on semantic change in countless books, both popular and special. However, some of the examples I have collected over the years may pique the curiosity of our readers.

An especially striking phenomenon in the war of words or, more properly, the war of senses is how one, often accidental, meaning kills all the others. The result produces such a strong impression, because language change, a trivial phenomenon to a historical linguist, is seldom easy to observe, and amateurs often express surprise when told that language changes. Usually “the harm is done” behind the scenes.

The most noticeable examples occur in the tabooed sphere. I am a lifelong admirer of A. T. Hatto’s translations of the great Middle High German poems The Lay of the Nibelungen, Tristan, and Parzival. Gay knights are mentioned regularly in the three books. The translations appeared in the middle of the twentieth century. I remember that time well. Dickens’s character Walter Gay (Dombey and Son), the name of the poet John Gay (the author of The Beggar’s Opera), and the traditional rhyme May ~ gay sounded absolutely neutral. Today, students smile when they read about gay knights, though they of course know that gay here means “dressed for battle, in full gear and happy” (gaily and gaiety with reference to joy are still neutral!) and that in this context gay is a standard epithet. But the suppression of the traditional senses by the sense “homosexual” is remarkable. Even lay “song” provokes merriment.

John Gay, 1685-1732.

John Gay, 1685-1732.A truly catastrophic case is Horny Siegfried. The history of queer, a synonym for “odd,” is less dramatic. Both gay and queer are words of French origin, and both seem to have meant “bad, licentious” quite early, so that the family name Gay might have originated as an offensive “moniker,” but surely, Dickens had no intention of humiliating Florence Dombey’s prospective husband. Be that as it may, today, queer has only one meaning and cannot be used in any context outside the one so familiar to us.

A scene from John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera.

A scene from John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera.Not only semantics but also phonetics may fall victim to unwanted associations. Cony (or coney) has existed in English since the Middle period, and for a long time it rhymed with money, but the word occurs in the Bible and (the horror of it!) made people who read or heard Psalm CIV: 18 have less pious thoughts than expected, and the pronunciation of cony rhyming with bony was introduced. Hence the now accepted vowel in this word and in Coney Island.

I read in a nineteenth-century story: “Friendship matures with intercourse.” It certainly does, but who would write such a sentence today? The same shift, that is, the conquest of one sense to the destruction of all the others, is not a uniquely English phenomenon. German Verkehr can still be used with the traditional meaning “traffic, transportation”; yet one should be on one’s guard in using it elsewhere. Outside the genital sphere, I may mention the embarrassing word poop “the stern of the ship,” probably called this for good reason. In any case, stern is a more dignified name for the same part of the vessel. By contrast, unwanted associations may be forgotten. This is what, quite probably, happened in the history of the noun cake (think of caked with mud). As a general rule, ignorance of etymology is a blessing.

Such examples can be easily multiplied. One more will suffice. Today, if you say that your friend Mr. X is very liberal, you probably imply that the said gentleman has strongly pronounced leftist views. Yet a liberal college, whatever its avowed aim, teaches the art considered “worthy of freeborn men”. This interpretation won’t surprise anyone who knows the words liberate and liberty. Both refer to freedom. But a free person may also be free in bestowing money (hence a liberal donation) and in not being restricted by a dogmatic interpretation of rules (hence a liberal interpretation of a law). We still understand all those senses. Yet out of context, liberal means “the opposite of conservative.” It may take the life of one or two generations for liberal “generous” to become as obsolete as gay “merry” and queer “odd” are to us. Queer studies has only one meaning. Soon liberal arts may be restricted to “arts opposed to conservative politics.” Words change, and words follow suit.

This is a flourishing liberal college.

This is a flourishing liberal college.A curious case is the recent history of the adjective niggardly “stingy.” The issue keeps turning up like a bad coin. The word, which is of Scandinavian origin, has been current in English since Chaucer’s days. The verb niggle “to cause small discomfort, etc.” is also an import from the north. Again and again somebody feels offended by this adjective. The thesis about the blessings of etymological ignorance is irrefutable (if we always knew the extinct senses of the words we use, we would be unable to understand one another). Yet sometimes ignorance of etymology may have detrimental results. Nothing in the world is perfect, as the Fox said to Saint-Exépury’s Little Prince.

The word jury, a homophone of Jewry, does not seem to irritate anyone. Also, Americans usually pronounce due as do, and that is why undergraduates (and perhaps not only they) constantly write: “Is the paper do by the end of the semester?” But British speakers tend to pronounce due as Jew, and I am always amused to hear from them that, in order to join a certain learned society, one should only pay one’s “Jews.” Am I supposed to be offended? I hope not. Anyway, I live in America and pay my “do’s.”

The most traditional chapters on historical semantics deal with the deterioration and the amelioration of meaning. Yet the truly enigmatic situation occurs when the reference goes neither up nor down, but rather in an unpredictable direction. For example, there can be little doubt that the adjective quaint and the verb acquaint are related. The Medieval Latin etymon of acquaint is accognitare. Quite consistently, acquaint, also via Old French, goes back to Latin cognitus “known.” The root is immediately recognizable: consider cognate, cognition, recognize, and the less obvious reconnaissance. But the progression of senses in English is a riddle: “skilled, clever; skillfully made, fine, elegant” (so far, so good, even though we are already rather far from “known”), “proud, fastidious” (all those senses were recorded in the thirteenth century), then “strange, unfamiliar” (a century later), and finally, in the 1700’s, “uncommon but attractive.” Queer, isn’t it? The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, from which I borrowed the glosses for quaint, states: “The development of the main senses took place in Old French; some of the stages are obscure.” And so they are. If something is known, why should it become unfamiliar?

Your good acquaintance, a quaint old gentleman.

Your good acquaintance, a quaint old gentleman.More along the same lines next week.

Image credits: (1) “John Gay” from a sketch by Sir Godfrey Kneller in the National Portrait Gallery, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) “Painting of John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera, Act 5” by William Hogarth, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) “2016 Brooklyn College Library” by Beyond My Ken, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (4) “Aged black and white cane elderly” by Nikola Savic, Public Domain via Pixabay. Featured image credit: “Jousting at the Pennsylvania Renaissance Faire” by Glenn Brunette, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post From the life of words, part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

12 Star Wars facts from a galaxy far, far away

On 25 May 1977, a small budget science fiction movie by a promising director premiered on less than 50 screens across the United States and immediately became a cultural phenomenon. Star Wars, George Lucas’ space opera depicting the galactic struggle between an evil Empire and a scrappy group of rebels, became the highest-grossing movie of the year and changed the course of movie history and American pop culture.

On a budget of $11 million, Star Wars garnered 10 Academy Award nominations (winning 6 plus a Special Achievement Oscar), changed how films were marketed and merchandized, revolutionized special effects, and spawned a franchise of movies – an original trilogy, a prequel trilogy, and a sequel trilogy/series of spinoff films currently in progress – that altogether have grossed over $7 billion. For many, Star Wars is the epitome of the science fiction genre, appealing to diehard fans and mainstream audiences alike, and its characters, music, and quotes have entered the collective pop cultural zeitgeist. To celebrate one of the most influential and beloved movies in history, we’ve assembled some fascinating Star Wars facts:

1. Star Wars was among the first 25 films to be inducted into the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry in 1989.

2. Peter Cushing (who played the calculating Grand Moff Tarkin) wore carpet slippers in most of his scenes as his boots were too small, a fact that puts his dastardly act of ordering the destruction of Alderaan in a new light.

3. Star Wars’ most famous phrase, “May the Force be with you,” became a police recruiting slogan in 1970s’ England.

4. Ronald Reagan’s “Strategic Defense Initiative” was nicknamed Star Wars, as it was planned as a defense against a hypothetical Soviet missile attack from the vantage point of space. It was scrapped in 1993 due to the end of the Cold War, after costing the US government $30 million.

5. Leigh Brackett, famed screenwriter of the Howard Hawks noir film The Big Sleep, wrote an early draft of the first Star Wars sequel, The Empire Strikes Back, which drew upon her science fiction novels such as The Sword of Rhiannon. She died in 1978 and never saw the completed, re-written film, which premiered in 1980.

Statue of Atlas (with a passing resemblence to George Lucas) holding the Death Star. Pazo de Bendaña, Toural, Santiago de Compostela. Photo by Toural Imperial, added by Amio Cajander, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Statue of Atlas (with a passing resemblence to George Lucas) holding the Death Star. Pazo de Bendaña, Toural, Santiago de Compostela. Photo by Toural Imperial, added by Amio Cajander, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.6. Record producer Meco Monardo reworked John Williams’ main theme as well as the Cantina Band music into a disco track that spent 2 weeks at the top of US music charts in 1977.

7. Acclaimed Academy Award-winner Alec Guinness (Obi-Wan Kenobi) once made a small boy cry when he traded an autograph for a promise that the young fan would never see Star Wars again. Guinness was embarrassed that he was famous for what he believed to be a banal reason.

8. George Lucas drew on the Westerns of John Ford and the samurai films of Akira Kurosawa for the themes and aesthetics of his film, especially Kurosawa’s 1958 classic, The Hidden Fortress. The theories and works of mythologist Joseph Campbell also served as a major influence, which were later presented to the general public in a seminal 6-part television series with Bill Moyers titled The Power of Myth.

9. In 1970, only 5% of all films were science fiction, but by 1980, this figure reached 35%, in large part due to the success of Star Wars and contemporary films such as Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

10. The hologram message of Princess Leia that R2D2 plays for Luke (”Help me, Obi-Wan Kenobi. You’re my only hope.”) was the first-well known instance of using a 3-D projection for communication in a film. Most previous science fiction movies and television shows like Star Trek had used communication devices that resembled telephones or televisions. Forbidden Planet from 1956 was an early example that used holograms.

11. Fittingly, with Lucas’ affinity for myth and allegory, the names of many of the main Star Wars characters have symbolic meaning. Darth Vader evokes “death invader” but actually means “dark father,” whereas Luke Skywalker’s name comes from the Greek “leukos,” meaning light. Obi-Wan Kenobi’s name has Japanese influence, and rogue Han Solo’s name confirms that he is a loner.

12. The action figure was popularized by Star Wars in the late 1970s and the toy industry never looked back. The Star Wars franchise itself has grossed billions of dollars in themed merchandise since the first film’s premiere.

Featured Image credit: model of R2D2 at Star Wars Exhibitition Argentina, FAIL, July 2009. Roger Schultz, CC BY 2.0 via flickr .

The post 12 Star Wars facts from a galaxy far, far away appeared first on OUPblog.

Wilfrid Sellars and the nature of normativity

Wilfrid Sellars would have been 105 this month. He stands out as one of the more ambitiously systematic philosophers of the last century, with contributions to ethics, metaphysics, epistemology, and philosophy of language, alongside incisive historical examinations of Kant, and several others. We can read him as a philosopher in a classical mode, always in conversation with figures from the past. But he also had a very modern set of concerns: what is it to construct scientific theories, and how do we fit into the “image” of the world that they generate? This ambitious project was what first drew me to Sellars’s work.

One focus running across his work is the nature of normativity – what we ought to do, what is good, correct, etc. Sellars demonstrated the indispensability of normative dimensions of our concept usage, not only to moral reasoning, but also to epistemic facts. This dimension of his work would be folded into equally robust commitments to naturalism and scientific realism. There would be no appeals to mysterious (“queer” as J.L. Mackie would have said) normative entities. But he was not proposing an anemic normativity, awaiting reduction; that would be “a radical mistake” (Empiricism and the Philosophy of the Mind, §5). Instead, much of his work can be read as anticipating themes and maneuvers that would later be taken up by some expressivists in ethics, and broader expressivist projects in philosophers such as Robert Brandom and Huw Price. Once we recognize that our words can play roles beyond the descriptive and the logical, we see that “many expressions which empiricists have relegated to second-class citizenship in discourse are not inferior, just different” (Counterfactuals, Dispositions, and the Causal Modalities, §79). Normative terms that initially appear to be descriptions of an agent instead function as ascriptions of normative status – crediting, demanding, permitting and entitling agents to their beliefs and the actions that this might license.

This might feel underwhelming if it ended here – normativity as “what folks around you let you get away with.” Can there be substantial normative truths without violating those naturalist commitments? Sellars suggested that this should be pursued by an analysis of the structure of intentions. Were we to express our own subjective intentions overtly, we might say something of the form “I shall do A in C” where A is some action and C is some set of conditions. But we might also express some intentions in the form of “It shall be the case that C,” in which case my commitment to take future actions is more open-ended. Compare, for example, “I’ll feed Lauryn’s cats this weekend,” with “My students will learn Fitch notation this semester.” We often undertake such intentions because they are subjectively reasonable to us, if not to others. But theoretical reason in all its domains has an intersubjective quality. What proves a conjecture, or warrants for a hypothesis is not a matter of personal conviction, but of satisfying standards that rational agents engaged in those theoretical projects would ideally agree upon and adopt. Sellars would characterize this as categorical reasonableness in practical reasoning and strive to “make intelligible the intersubjectivity and truth of moral oughts” (Science and Metaphysics: Variations on Kantian Themes VII.4). This intersubjective agreement could be expressed as what Sellars would call “we-intentions,” e.g. “We shall do A in C.” Moral principles would be generalizations we could derive from empirical knowledge of ourselves and the world, given a we-intention to maximize general welfare.

Two slightly tricky questions remain, though: who are “we,” and what is good for us? Sellars’s proposal rides on there being some unifying account of general welfare, from which to derive thicker moral principles. This notion is thin by design, and when we look under the hood, I would say that we do not find neatly delineated human goods around which directives can be formulated. Rather, we find layer after layer of interests, conditioned by race, gender, class, and other dimensions of our social practices. The pluralism this suggests preceded Sellars, of course, and was a feature of the pragmatist side of his intellectual ancestry. This plurality of interests has led many to calls the objectivity and universality of normative claims into question, leaving us to coalesce into smaller communities where agreement comes more easily, but in which we are immune to the reasons of others and insulated from compelling concern for their welfare. (No one embraced this view with more gusto than Richard Rorty).

I believe we should embrace the sort of pluralism described here, but reject the view that it entails this sort of fragmenting of normativity. There is great value in Sellars’s vision of unifying intentions, so long as we can see that they must be shaped by many different voices, that we have often failed to heed them in the past, and that their development is a perpetual self-critical, self-correcting process. “We” are not something to be discovered, “we” are something to be achieved. But many academic philosophers do meagre service to this even when they genuinely embrace more inclusive, “progressive” values. Even where race, gender, and class are recognized as concerns in thinking about knowledge and value, they are often treated as parallel, perhaps secondary problems, rather than central concerns. (This is not simply to wag my finger at fellow philosophers; I have drifted in these directions myself over the years.) Philosophers love the universality and necessity, and we tend to reach for them by subtraction, constructing agents in general terms by eliminating specifics. But even our best efforts to imagine what “everyone” is like will tend to look most like ourselves, recapitulating our own assumptions and ideologies in the process. To do better requires taking voices other than our own seriously, and engaging with the messy complexity that pluralism suggests. These are not idle academic concerns. To read the news of late is to see fissures between different communities in the west yawning more widely, and tearing away at practices and institutions that would challenge them. This is not a moment for those engaged in philosophy to punt on the social and political dimensions of their work.

The post Wilfrid Sellars and the nature of normativity appeared first on OUPblog.

Asking Gandhi tough questions

Why did Gandhi exclude black South Africans from his movement? Could Gandhi reconcile his service in the Boer War with his later anti-imperialism? Why did Gandhi oppose untouchability, but not caste?

These are questions contemporary historians are asking as they rethink Gandhi’s legacy. In 1936, Howard Thurman and Benjamin Mays asked Gandhi himself. Thurman and Mays were good friends and colleagues at Howard University’s School of Religion, and they were part of a network of black American Christian intellectuals and activists who looked abroad, even in other religious traditions, for resources to spark a racial justice movement in the United States. Their international travels—including asking Gandhi tough questions—became vital to the later civil rights movement.

Thurman met Gandhi in March 1936. Thurman’s first question was whether black South Africans took part in Gandhi’s movement. Thurman was referring to the first phase of Gandhi’s career, when he organized against excessive taxing and British restrictions on free movement of Indians between South African states. The simple answer to Thurman’s question was no; Gandhi clarified, “I purposely did not invite them. It would have endangered their cause. They would not have understood the technique of our struggle nor could they have seen the purpose or utility of nonviolence.”

Gandhi did not explain why he thought black South Africans would not have understood nonviolence, but Howard Thurman wanted to learn more. “How are we to train individuals or communities in this difficult art?” Thurman asked. It requires “living the creed in your life which must be a living sermon,” Gandhi replied. There is no easy path; ahimsa requires persistence and perseverance. Gandhi went on to explain the moral logic of noncooperation as it might apply in the context of Jim Crow.

Photo courtesy of Howard Thurman Estate. Do not re-use without permission.

Photo courtesy of Howard Thurman Estate. Do not re-use without permission.In December 1936, Mays met the Mahatma. He pressed Gandhi to reconcile nonviolence with what he did in the Boer War, when Gandhi organized and participated in an ambulance corps in support of British forces. Mays wondered why Gandhi had declared war on untouchability but not on caste. “For the most part it is a good thing for sons to follow in the footsteps of their parents,” Gandhi replied; it was the idea that castes are hierarchical that must be abolished. Mays was not persuaded. Born to poor tenant farmers in South Carolina, Mays had not wanted to follow his parents into the equivalent of a racialized American peasantry.

Mays also asked Gandhi about nonviolence. He reported on his discussions with Gandhi in his weekly column in the Norfolk Journal and Guide, a regional black paper with a wide readership. Therein Mays specified cultural and religious roots of Gandhi’s approach. The doctrine of ahimsa, Mays explained, is in Hinduism but Gandhi seemed to draw direct lessons about it from Jainism, an ancient non-theistic South Asian religious tradition about which Mays’s readers were likely unaware.

Thurman and Mays saw significant shortcomings in Gandhi’s work and in his moral vision; nevertheless they believed that Gandhi’s program held promise for black American activism. Asking Gandhi tough questions was critical if they were to take ideas and practices from one context to apply in their own. After extensive travels in India, Thurman and Mays returned to the U.S. where they lectured widely about Gandhi’s activism, Indian religions, and transformative possibilities of black Christian nonviolence. In the 1940s, their students and protégés James Farmer, Bayard Rustin, and Pauli Murray experimented with nonviolent direct action by integrating buses, organizing sit-ins, and theorizing noncooperation—all of which became mainstays of the later movement.

Howard Thurman and Benjamin Mays became mentors to the person who would become known as the “American Gandhi,” and Martin Luther King, Jr. cherished their lessons. He famously carried with him everywhere Thurman’s Jesus and the Disinherited, the book Thurman wrote in the wake of his travels through South Asia. And King would later remember Mays’s experience of visiting a Dalit school as King’s own experience, thus underscoring Mays was indeed what King called “one of the great influences in my life.”

This network of black Christian intellectuals and activists brought lessons from independence movements in Asia and in Africa that stoked an American freedom movement. Indeed, In 1959 King affirmed that Americans had much to learn from activists around the world: “what we are trying to do in the South and in the United States is part of this worldwide struggle for freedom and human dignity.”

Featured image credit: “Howard University chapel – detail of stained glass window” by Fourandsixty. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Asking Gandhi tough questions appeared first on OUPblog.

May 23, 2017

Agricultural policy after Brexit

A majority of Britain’s farmers voted for Brexit in the referendum. This is perhaps surprising in the context of an industry which receives around £3 billion in subsidies from the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), and yet comprises only about 0.7% GDP. Of all the vested interests, British farmers have more to lose from Brexit than almost any other industry.

From the public interest perspective, there is much to gain. The CAP pays the bulk of the subsidies as a payment for owning land (called Pillar I). The economic effects of Pillar I subsidies are obvious: increasing the revenues per hectare raises the price of a hectare. Land prices capitalise the subsidies, creating barriers to entry. As a result, the CAP has also now established a fund to help young farmers get into the industry, in the face of the obstacles the CAP itself creates. The rest of the subsidy goes on rural development and environmental schemes (called Pillar II). These are often poorly designed.

It would be hard to make a new British agricultural policy worse than the CAP, short of reverting to the subsidising production directly, which created the notorious wine lakes and butter mountains of the past.

There are several options for reform because of Brexit. Discounting reverting to more of the same, the first option is to shift some of the subsidy from paying to own land towards more spending on the environment – i.e. shifting the balance from Pillar I to Pillar II.

The second is more radical, switching to a system of paying public money for public goods. The second meets the economic efficiency criterion: it would start with identifying the market failures, and then use a combination of taxes and subsidies to address them. The public goods, which the market will not deliver unaided, are mostly environmental, and are concentrated on the small farms mostly, but not exclusively, in the uplands. By happy coincidence it would therefore direct subsidies to poorer and more marginal farmers, rather than large scale producers. This could be tied in with the government’s manifesto commitment to a 25-year environment plan to ensure the next generation inherits a better environment.

The farming lobby resist this more radical option for at least three reasons: they will suffer capital loses on land prices; they will face considerable international competition; and the speed of the change will be disruptive.

On the capital losses, this is a distributional impact, which would fall most heavily on the better off landowners. It is likely in any event that the 2020 reforms of the CAP in Europe will reduce the subsidy to the larger landowners in any event.

Brexit is a once in a generation opportunity to get rid of one of the most inefficient policies the EEC, and then the EU came up with upon which most of the EU’s money has been spent.

On the trade issues, these are substantive, but can and should be dealt with independently of the subsidy regime, through tariffs and trade agreements. The sad fact is that almost all of British agriculture is uncompetitive in global markets in the absence of tariffs. This is especially true for sheep and other meat production, even if issue of animal welfare is taken into account. It is for the government to decide whether consumers should pay a premium through tariffs and trade barriers in order that more expensive food is produced in the UK. If, as the government has suggested, it is looking for free trade agreements with the US and others, as well as with the EU after Brexit, the trade consequences for British farmers are likely to be much more detrimental than the loss of the CAP subsidies.

On the disruptive impacts of a sudden withdrawal of Pillar I subsidies in 2020, these arise because of the time horizons in crop choice and farm management. In order to enable farmers to plan their strategy ahead, the government would need to signal now what the post 2020 regime may look like. There is however no evidence that there is any government clarity, let alone decisions, on agriculture policy yet, or indeed that there is going to be soon. Hence the case for transitionary arrangements is considerable. One possibility is to set out a clear framework from 2025 onwards, and taper a transitionary path from 2020 to 2025.

Brexit is a once in a generation opportunity to get rid of one of the most inefficient policies the EEC, and then the EU came up with upon which most of the EU’s money has been spent. There is no obvious case to spend £3 billion, given all the other calls on public expenditure. There is however a strong case for using some of the money freed up on more environmental public benefits. This should be developed as a core part of the over arching 25-year environment plan. Indeed it must be if the 25-year plan is to be delivered since around 70% of the land is subject to agricultural use.

A remaining puzzle is why the farmers voted for Brexit. It turns out to be one of the rare cases where one of the most effective lobby groups Britain has ever seen voted for the public interest against their private ones. They cannot possibly have believed their subsidies would not be reduced as a result of the choice they made through the ballot box.

Featured image credit: Agriculture cereal clouds by Pexels. Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post Agricultural policy after Brexit appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers