Oxford University Press's Blog, page 363

May 23, 2017

Why are world food problems so hard to solve?

More than 20 million people in Yemen, South Sudan, Somalia, and northeast Nigeria are now facing extreme hunger, with the potential for not just widespread death, but also the deepening of long-term political and military crises in East Africa. United Nations humanitarian coordinator Stephen O’Brien has called this food crisis the world’s greatest humanitarian crisis since 1945. Observers are asking, given all the progress that has been made since the end of World War II in international assistance and development, how can the world be faced again with a large-scale food crisis?

The answer is complex, as food crises arise from a number of causes, including poverty, war, politics, and disease. Yet one of the key reasons the world community has a hard time responding to famine lies in the structure of global food relations. Policymakers and people often talk about a global food system, but we are living in a time where food relations, rather than being a system—an integrated and governed whole—are instead a “partially self-organized collection of interacting parts,” to use the words of the UK’s Foresight Group.

Another way to describe the structure that stretches from farms to forks around the world would be to call it a network. This food network encompasses activities involved in producing, gathering, harvesting, processing, transporting, preparing, and consuming food. Why is this distinction between a system and a network important? It matters because the food network is, in comparison to a food system, less responsive to straightforward policy or market-based solutions.

There were efforts following World War II to create a unified international food system. John Boyd Orr, a Scottish nutritionist who became the first Director General of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, proposed the creation of a World Food Board to manage the global food supply, harmonizing global production and consumption of food. He was responding to a sense that food insecurity contributed to causing World War II and was a central experience for soldiers and civilians during and after the war. Boyd Orr’s plan failed because nations were unwilling to cede authority over food production to an international body. As a result, while international organizations like FAO play important coordinating functions in world food, production and distribution activities remain under the control of national governments and increasingly private actors like multinational corporations.

President Kennedy with George McGovern, Director, Food for Peace, 1961. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

President Kennedy with George McGovern, Director, Food for Peace, 1961. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The resulting food network has critical implications for international responses to food crises, because those responses are dependent on national choices. For countries such as the United States, food aid emerged in the post-war years as a critical component of diplomatic efforts to promote peace and stability. President Eisenhower formalized the use of what has been called “food power” when he signed the 1954 Agricultural Trade Development and Assistance Act (most often called PL-480 or Public Law 480), which created America’s first permanent program to provide food as foreign assistance. While PL-480 was initially intended to reduce the cost of storing surplus food, in the 1960s Presidents Kennedy and Johnson emphasized the humanitarian aspects of providing food aid both at home and overseas. Since the 1960s, the name and structure of government food assistance programs has changed, but the idea of food aid has been supported by both Republican and Democratic presidential administrations.

As a result, international food assistance depends on the actions and politics of individual nations. This means that when a food crisis like the current one in North Africa and the Middle East develops, the United Nations and other non-governmental organizations must raise funds from individuals and member nations rather than just focusing on assisting people who urgently and desperately need aid.

Boyd Orr’s idea of a world food system would have tried to bring food supply and demand into balance to avoid food crisis. In contrast, the current world food network is locked in a reactive posture, waiting for food crises to arise and then struggling to raise funds and gather supplies while people suffer and die from hunger. Beyond causing death and illness, food insecurity can undercut progress on development goals like education and improving the status of women, which can have effects that linger long after a food crisis has ended.

There is an unfortunate tendency for food to gain attention during crisis and then fade into the background until a new crisis arises. Food is too critical a component in global peace and prosperity to be left to brief spans of attention. Commitments can be made to develop a food network that is more sustainable, adaptable, and resilient, one that is able to anticipate and respond to food problems. The cultivation of such a network however, will take years and likely even decades, requiring sustained allocations of resources.

There is good reason to expect that world food problems will become more rather than less challenging in the future. While historians like myself are hesitant to use the past to predict the future and forecasting the future is always a tricky business, a range of recent assessments have concluded that future impacts on agriculture and food production from sources such as change and variability in global climate and environmental systems are highly probable. Combined with ongoing population growth, demographic changes, and linkages between global food, energy, and water networks, simply hoping that food production will keep up with demand seems a dangerous bet to make.

Given the range of global challenges we face, people and policymakers would be wise to reconsider the lessons about food and war learned by postwar policymakers like President Eisenhower and Sir John Boyd Orr and recognize that there are practical as well as moral reasons to address world food problems.

Featured image credit: United Nations Economic and Social Council chamber in New York City by MusikAnimal. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why are world food problems so hard to solve? appeared first on OUPblog.

How well do you know early video game history?

From their genesis in the development of computers after World War II to the ubiquity of mobile phones today, video games have had an extensive rise in a relatively short period of time. What started as the experimental hobbies of MIT students and US government scientists of the 1950s and 60s became a burgeoning industry with the emergence of home consoles and arcades in the 1970s. A market crash came in the early 1980s, but the revolutionary games and marketing of Nintendo saw the industry rebound and grow into the thriving, billion-dollar market that still exists today.

We’ve created a quiz to test your knowledge of their history and their cultural impact…do you know the story of early video and arcade games?

Featured Image credit: Pac-Man mosaic in Bilbao near the Guggenheim Museum, 2008. Kurtxio, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post How well do you know early video game history? appeared first on OUPblog.

Why are giant pandas black and white?

Most people in the western world learn that the giant panda has striking black and white colouration at kindergarten; but are never told why! The question is problematic because there are virtually no other mammals with this sort of colouration pattern, making analogies difficult.

At UC Davis and CSU Long Beach, we instead decided to break up the external appearance of giant pandas into different regions roughly aligned with the species’ white back, rump, and face; and its black legs, shoulders, ears, and eye patches. This then enabled us to compare these body areas with those of other carnivores and bear subspecies (the giant panda is one of eight bears).

We scored each of these body areas on a light to darkness scale across 195 species of carnivores and 43 subspecies of bears, using about 2,500 photographs, and then asked what environmental variables are associated with light coloured backs and rumps? The answer is snow cover – white carnivores are found in areas where snow lies for much of the year – think of polar bears. Now we asked what variables are associated with dark legs and dark shoulders across species –deep shade. There was no association between temperature and the lightness or darkness of these areas.

Given that the giant panda occupies areas covered in snow for some of the year as well as dark subtropical rainforest at other times, it seems reasonable to argue that its external coloration has evolved to be cryptic in two different environments. Why does it have to make this compromise? The answer lies in its diet. Giant pandas eat 98% bamboo of extremely low quality. This prevents them from being able to put on enough fat to see them through a period of winter hibernation, so they will encounter snow. Think of a grizzly bear living in Canada. It puts on enough weight over the summer to allow it to sleep in a den throughout winter and thereby avoids moving in snow: it has a brown coat. The polar bear on the other hand does not hibernate and has white pelage.

In contrast to findings regarding the panda’s torso, we could find no associations between dark ears and dark eyes and living in shady habitats.

Instead, we discovered that pugnacious carnivore species often have black ears! Dark eye patches are found in species that are out in daylight (like the giant panda) suggesting they are used in communication. Interestingly the shape and size of the giant panda eye mask is highly variable (pear shaped or round) and laboratory work from Germany shows that giant pandas can remember the shape of these eye markings for up to a year. Thus dark eye markings may be involved in individual recognition. George Schaller, the great wildlife biologist who studied giant pandas in the wild, reported that losers in confrontations with other pandas covered their eyes with their forearms suggesting that these markings may be signals of dominance too.

So now parents can tell their children that giant pandas are black and white for at least three reasons! Nature just gets more and more interesting.

For more information, hover over the different areas of the panda below.

Featured image credit: Giant Pandas having a snack by Chi King. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why are giant pandas black and white? appeared first on OUPblog.

Analyzing genre in Star Wars

In Hollywood Aesthetic: Pleasure in American Cinema, film studies professor Todd Berliner explains how Hollywood delivers aesthetic pleasure to mass audiences. Along the way, Professor Berliner offers numerous aesthetic analyses of both routine Hollywood movies and exceptional ones. His analyses, one of which we excerpt here, illustrate how to study a film’s aesthetic properties. In honor of the 40th anniversary of the release of the original Star Wars (1977), we are posting the following excerpt from Chapter 10, “The Hollywood Genre System.”

Inaugurating the most financially successful franchise in the history of entertainment, the original Star Wars (1977) has become one of the most widely and intensely loved movies of all time. Film scholars, however, lambasted Star Wars for its simplicity. Peter Lev calls it one of the “simple, optimistic genre films in the late 1970s.” David Cook says it privileges “a juvenile mythos.” Jonathan Rosenbaum calls the movie mostly “fireworks and pinball machines,” a deliberately silly film that offers only “narcissistic pleasures.” In his book on Star Wars, Will Brooker summarizes the scorn that scholars show toward the film: “Cinema scholarship seems embarrassed by Star Wars — embarrassed that a movie series so popular, successful and influential is also, apparently, so childishly simple.”

How do we explain the discrepancy between scholars’ opinion of the film and its popular success? What pleasure do mass audiences get from Star Wars that scholars do not? What aesthetic weaknesses do scholars find in the film that mass audiences don’t? I hope to demonstrate that we can attribute much of the discrepancy between Star Wars’s popular and scholarly reception to the two audiences’ differing levels of genre expertise. Hollywood’s genre system makes routine filmgoers into experts, but filmgoers do not share the same level of genre expertise, and more expert filmgoers require greater novelty and complexity to feel an exhilarated aesthetic response.

For an average spectator, Star Wars exhibits more challenging and diverse genre properties than most scholars recognize…A simple list of genres that figure fairly prominently in the film would include fairy tales, adventure films, and swashbucklers (swinging on ropes, rescuing a princess, Leia’s wardrobe, light saber fights); the Western (a cantina scene, desert landscapes, shots of a burning homestead, bounty hunters); the 1930s science fiction serial Flash Gordon (ray guns and explosions, an episode format, an opening text that explains previous events); fantasy comics and novels, such as John Carter of Mars, Buck Rogers, and The Lord of the Rings (alien creatures, monsters, a hero on a quest, a world in peril, battles and adventures in far-off lands); samurai movies (obsolete warriors, light sabers); a comic duo, such as Abbot and Costello and Laurel and Hardy, that pairs a neurotic skinny straight-man with a fat clown (C3PO and R2D2); the philosophical fantasy film, such as Lost Horizon (1937) (the Force, spiritual training); horror (Darth Vader, Hammer horror-film actor Peter Cushing); gangster (Han’s debt to Jabba the Hutt); Nazi documentaries and World War II films (soldiers in formation, air battles, a prison escape, rebels planning an invasion in a war room, the uniforms of Grand Moff Tarkin and other officers in the Galactic Empire); the foreign film (subtitled dialogue); the historical epic, such as The Ten Commandments (1956), Ben-Hur (1959), Spartacus (1960) and Lawrence of Arabia (1962) (nation building, spectacular settings, a small band of rebels fighting a mighty empire); and, of course, science fiction film and television, such as Forbidden Planet (1956) and Lost in Space (robots, interstellar travel), Star Trek (photon torpedoes, light-speed space travel, tractor beams, outer space cultures), and Planet of the Apes (Chewbacca).

The film finds fortuitous linkages between diverse genre topoi. The figures of C3PO and R2D2 blend the tin man from The Wizard of Oz, the comic duo of Abbot and Costello, and the space robot of Forbidden Planet in a way that feels unified and inevitable. The figure of Han Solo makes the Western’s quick drawing gun-for-hire — decked out in a vest, boots, and a gun by his side — seem a lot like both the captain of a pirate ship in an Errol Flynn adventure and, when matched against Princess Leia, one half of a screwball comedy pair. The light saber makes something like a samurai’s sword a natural supplement to a Star Trek phaser. The imagery in an early scene with Princess Leia and Darth Vader (figures 10.1 and 10.2) combines a science fiction setting with elements from fairytale (Leia’s flowing white gown), horror (Vader’s bug-like metallic mask), and the WWII prison movie (handcuffed Leia led by Storm Troopers and the Nazi-like garb of a solider standing beside Vader). “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away” is apropos because Lucas’s futuristic science fiction film feels like the past.

Figure 10.1. Still image from Star Wars (1977), pg 197 of Hollywood Aesthetic by Todd Berliner. Used with permission.

Figure 10.1. Still image from Star Wars (1977), pg 197 of Hollywood Aesthetic by Todd Berliner. Used with permission. Figure 10.2. Still image from Star Wars (1977), pg 197 of Hollywood Aesthetic by Todd Berliner. Used with permission.

Figure 10.2. Still image from Star Wars (1977), pg 197 of Hollywood Aesthetic by Todd Berliner. Used with permission.I propose that many film scholars find Star Wars simplistic and unoriginal because they have too much experience with the film’s multifarious genre conventions — conventions that viewers with extensive knowledge of film genres can identify too easily. True film experts have seen it all before, which explains why scholars often celebrate the more self-conscious genre films of the same period, such as The Long Goodbye and All that Jazz (1979). Ironic and disdainful of Hollywood formula, such films reflect an expert’s weariness with mainstream American cinema.

Star Wars reflects no such weariness, irony, or disdain. Although it relies heavily on conventions that film experts have seen many times, average spectators would not so easily identify its genre properties. Rosenbaum’s blistering review of the film is largely a complaint about cinematic poaching from Triumph of the Will (1935), Flash Gordon (1936), The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T (1953), This Island Earth (1955), The Searchers (1956), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Samurai movies, and other films so familiar to Rosenbaum that, to his mind, the plot could have been regurgitated by “any well-behaved computer fed with the right amount of pulp.” Robin Wood calls the pleasures of Star Wars “mindless and automatic.” … He says that spectators find reassurance in “the extreme familiarity of plot, characterization, situation, and character relations.”

Such conventions may be extremely familiar to Wood and Rosenbaum, but I suspect that their scorn for Star Wars results in part from the fact that they have chunked so much film knowledge that they can identify the film’s genre properties too easily. Wood thinks he is criticizing Star Wars fans for taking pleasure in an “undemanding,” “reassuring,” “childish” fantasy, but really he might only be condemning their limited cinema expertise. For spectators who have only moderate familiarity with Hollywood genre conventions, Star Wars requires cognitive work. Wood would no doubt describe most Hollywood movies as “mindless and automatic” because they are for him. However, Wood’s critique cannot explain the enduring and exhilarated passion that we see in generations of Star Wars fans, whose engagement with the film does not by any means look “mindless and automatic”; Star Wars fans are engrossed and elated. For an average viewer, the film finds the optimal area between unity and complexity, familiarity and novelty, easy recognition and cognitive challenge.

Featured image:Figure 10.1. Still image from Star Wars (1977), pg 197 of Hollywood Aesthetic by Todd Berliner. Used with permission.

The post Analyzing genre in Star Wars appeared first on OUPblog.

Challenges for critical human rights institutions in the Americas

Across the Americas, authoritarian leaders are jailing opponents, firing key investigators, and displacing indigenous communities in efforts to consolidate power. The political turmoil has led to critical challenges for the 35-nation Organization of American States, the world’s oldest regional governmental alliance.

Venezuela recently announced its withdrawal from the OAS; a member state has not willingly left the organization since its founding in 1948. In March, the Trump Administration boycotted hearings in Washington, D.C., before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. This marked the first time the U.S. government failed to participate in a hearing called by the Commission.

If member states turn away from the OAS, this will seriously debilitate its vital human rights institutions: the Inter-American Commission and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. For decades the Commission and Court have saved lives, secured redress for victims of rights violations, bolstered the rule of law, and provided crucial opposition to despotic regimes in the hemisphere.

Through the 1980s, the Commission shined a spotlight on the widespread abuses of Latin American dictatorships. Subsequently, during the region’s transition to democracy, the Commission and the Court confronted the dark legacy of these regimes. By striking down amnesty laws and urging investigations, both institutions fostered accountability for serious rights violations. Currently, the Inter-American Human Rights System has sharpened its focus on the marginalized of the Americas: indigenous communities, victims of gender violence, and many others who suffer discrimination.

“Inter-American Commision on Human Rights” by Daniel Cim. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

“Inter-American Commision on Human Rights” by Daniel Cim. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.As a result of their bold rulings, the Court and the Commission have often strengthened the protections of the American Convention on Human Rights, the hemisphere’s main rights treaty. They have also developed a creative jurisprudence that has become influential beyond Latin America – inspiring the major human rights institutions of the United Nations, Europe, and Africa.

The Court and the Commission are far from perfect, of course, and their decisions can disappoint for a variety of reasons. Still, in our era darkened by rampant nationalism, violence, and discrimination, these rights monitors are needed now as much as ever before. Throughout the Americas, we must demand that our governments recommit to the OAS institutions and their principles of democracy and rule of law. Whenever our political leaders deviate from these fundamental norms, we will need the support of our steadfast allies, the Commission and the Court, to oppose authoritarians and redress victims of rights abuse.

Featured image credit: “Secretary Kerry Delivers Remarks on U.S. Policy in the Western Hemisphere” by State Department. CC0 public domain by Wikimedia Commons .

The post Challenges for critical human rights institutions in the Americas appeared first on OUPblog.

May 22, 2017

Julius Evola in the White House

Conjecture and supposition tend to dog public figures who avoid the press. But the attention paid to Trump’s embattled Chief Strategist Steve Bannon is uncanny. Bannon’s reluctance to speak with the media—combined with a steady stream of commentary on him from anonymous associates and friends—is fueling speculation about his agenda and ideology. Adding to the frenzy are reports of Bannon’s eccentric reading habits that are forcing journalists and lay readers to explore bizarre and enigmatic literatures few have experience interpreting. Most notably, New York Times writer Jason Horowitz highlighted Bannon’s reference to an esoteric ultraconservative with complicated ties to Italian fascism and Nazi Germany named Julius Evola. In this and similar instances, hyperbole about Bannon flourishes, all while potential for real insights about his thinking goes unnoticed.

Let’s focus on Julius Evola. He is a figure who today is “referenced more than read” according to John Morgan, former editor and director at Arktos Media—the press responsible for most recent English-language translations of Evola’s work. That seems true of both of the Italian thinker’s avid followers, as well as of Bannon. We have only one piece of evidence suggesting that Bannon knows of Evola. During a 2014 speech he gave to a group assembled at the Vatican, he was discussing Vladimir Putin (in unfavorable terms) and moved to describe the Russian president’s alleged ideological adviser, Alexander Dugin, as a figure “who hearkens back to Julius Evola and different writers of the early 20th century who are really the supporters of what’s called the traditionalist movement, which really eventually metastasized into Italian fascism.”

That’s it. In no way does the comment suggests that Bannon is well-versed in the Italian thinker’s writings. Instead, Bannon’s suggestion that Evola and like-minded thinkers established an ideological foundation on which WWII fascism grew shows that he knows little about Evola or the history of fascism. The absence of substantive reference to Evola in Bannon’s statements has not tempered commentary, however. Evola’s writing includes unmistakable racism, and contemporary white nationalists and mainstream journalists alike look to him when linking Bannon with racism. True to form, the Italian thinker’s concept of race was arcane and inconsistent, declaring—in contrast with National Socialists—that race might “be differentiated in an individual’s body, soul, and spirit.” His thinking repelled prominent racists and anti-Semites during the fascist era: Guido Landra, racial theorist under Mussolini, claimed Evola’s concept of race would “certainly be of exclusive benefit to the Jew,” and documents on Evola prepared by Heinrich Hilmer’s S.S. staff labeled him a “pseudoscientist” with the potential to cause “ideological entanglements” in the Third Reich. Nonetheless, his references to Aryanism, contempt for Africans and Jews, and fetishizing of segregation drew him the adoration of future generations of fascist sympathizers.

Julius Evola by Anton Giulio Bragaglia (1889-1963). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Julius Evola by Anton Giulio Bragaglia (1889-1963). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.So too did Evola’s hatred for Christianity. He regarded the Levantine religion as a perverting force in Europe—one that undermined entrenched masculinist ideals and promoted an embryonic form of liberal egalitarianism at the expense of traditional hierarchy. To regain past European virtues, Evola advocated a return to pre-Christian Indo-European paganism while also showing sympathy for Islam and Buddhism. His anti-Christianism resonated, not only with German Nazism, but also neo-paganist strains in the contemporary far right. But his adoption by such forces was limited: he regarded fascism, National Socialism, and nationalism at large as sentimental populism—movements for the masses inadequate to forge the hierarchical society he coveted.

Is this the stuff of Bannonism? Hardly. Bannon famously identifies himself as an economic nationalist and a populist striving to undo elitism. Born to an Irish Catholic family, his worldview also involves fighting on behalf of a “Judeo-Christian west” opposite radical Islam. More intrigue surrounds his attitudes toward race and Judaism: In legal proceedings following Bannon’s trail for domestic abuse and battery in 1996, his former wife accused him of making anti-Semitic statements in private. But there are no serious indications that he partakes of the theorized racism or anti-Semitism one finds in Evola. On the contrary, Bannon spent part of his speech to the Vatican assembly urging European nationalist parties to drop their racialized agendas in favor of a culturally and religiously based nationalism.

Linking Bannon to Evola’s most sensational thinking requires a great deal of strain, and we shouldn’t be surprised that journalistic attempts to do so unravel into games of six-degrees-of-separation. But what is most unfortunate about this commentary is that, while pursuing elusive silver-bullet ammunition, it pays scant attention to actual lessons that can be learned from Bannon’s interest in Evola however dilettantish it may be. For in the obscure Italian thinker’s concept of history we find replication of a theme common to other authors who Bannon is known to read and recommend.

In a Politico article, Eliana Johnson and Eli Stokols explore Bannon’s purported admiration for writers such as William Strauss, Neil Howe, Nassim Taleb, Curtis Yarvin, and Michael Anton. These authors share, in the words of the Politico journalists, “the view that technocrats have put Western civilization on a downward trajectory and that only a shock to the system can reverse its decline.” And if that is the feature uniting Bannon’s reading and informing his agenda, it is most likely to have also drawn him to Evola. Evola referenced a wide body of religious traditions to argue that western society is decaying, and claimed that the rise of liberal modernity aligns with what Hinduism calls the Kali Yuga, or the dark age—the final in a four-age time cycle where spirituality is replaced with materialism and the structures and hierarchies that previously ordered societies disintegrate into a leveled (or egalitarian) social chaos. Evola would eventually embrace the fatalism inherent in this concept of history, anticipating that nothing could stop the destruction of the Kali Yuga and that its full realization could bring a fiery end to liberalism and reset the time cycle to a golden age. Earlier in his life, however, Evola believed that societies could rally against the cycle through will and industry; he supported fascism with the hope that its militaristic ideals and aesthetics signaled a retreat from liberal values, and that it might someday be imbued with spiritual content, returning society to virtue and righteousness.

That sounds more like the Bannon we are coming to know. Far from introducing new perspectives, his reference to Evola adds to existing impressions. It provides additional suggestion that Bannon operates with an apocalyptic vision for western society and a will toward radical change. One wonders, in that case, whether his activism is that of the older Evola—a fatalistic, anti-activism–or that of the younger; a man raging, with reckless optimism, against time.

Featured image credit: White House by Sean Hayford Oleary. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Julius Evola in the White House appeared first on OUPblog.

Aristophanes: Frogs and other plays [extract]

In this extract from the introduction to Aristophanes: Frogs and Other Plays, Stephen Halliwell describes the Theatre of Dionysos in Athens and provides readers with insight about the performance space, actors, and stage directions from ancient dramas.

The Theatre of Dionysos in Athens, on the south-east slope of the Akropolis, was the location for the dramatic performances at both the City Dionysia and, almost certainly, the Lenaia too (cf.‘Aristophanes’ Career’, above). The details of its fifth-century form are contentious, since the archaeological remains are mostly of much later date and literary evidence is scanty. But in recent years there has been an emergent consensus that the area for the audience’s wooden benches on the hillside, and therefore the size of the audience, was smaller in the late-fifth century than previously supposed. Many scholars now believe that Aristophanes’ comedies would have been watched by around 5,000–7,000 spectators (including some non-Athenians at the Dionysia, fewer at the Lenaia). That is still, however, a substantial proportion of the citizen body, representing approximately the same scale of attendance as at political Assembly meetings.

As for the performance space itself in the Theatre of Dionysos, the main components were a substantial, probably wooden stage building (skênê), and, in front of it, a large area, possibly rectilinear and elongated (trapezoidal) rather than circular in shape (as it was later to be), known as the orchêstra (lit. ‘dancing-floor’), and used by both actors and chorus. The dimensions of the orchêstra were perhaps of the order of some twenty metres in diameter and eight in depth, and to either side of it was an entrance/exit (eisodos, pl. eisodoi) for the performers. The stage building had a main central door (which could change its identity in the course of a play: see Women at the Thesmophoria and Frogs in this volume), a usable roof (e.g. Wasps 136 ff., Birds 267 ff., Lysistrata 829 ff., and perhaps Clouds 275 ff.), windows (cf. Wasps 156 ff., 317 ff., Assembly-Women 884 ff.), and, when required (Acharnians, Clouds, Assembly-Women), a second door. It is possible that there was a low wooden stage in front of the stage building, connected to the orchêstra by two or three steps; if so, it did nothing to impede the physical interaction between characters and chorus which is often evident in Old Comedy, for example in the confrontational parodoi of plays such as Knights (247 ff.) and Birds (352 ff.). Also available, though employed by Aristophanes purely for the purposes of paratragedy, were both the mêchanê (‘machine’), a sort of crane which suspended characters in simulated flight (see Sokrates’entry at Clouds 219 ff., plus Peace 174, Birds 1199 ff., and, just possibly, Women at the Thesmophoria 1009–14), and the ekkuklêma or wheeled platform, which represented interior scenes (Acharnians 407–79, Women at the Thesmophoria 101–265).

Most comedies were performed by three main actors, taking more than one role each when necessary, but occasionally supplemented by a fourth and even fifth actor for smaller parts; mute parts were additional. Masks, typically exaggerated and often grotesquely so, were always worn. All roles were played by males, and this probably held even for silent female figures such as the pipe-girl at Wasps 1326 ff., Reconciliation at Lysistrata 1114 ff., or Euripides’ Muse at Frogs 1308 ff. Even when such roles were notionally ‘naked’, as with the first two of those just mentioned, the body-stockings which formed a standard part of comic actors’ costumes would simply be designed to represent bare flesh and the appropriate anatomical externals. A body-stocking also allowed for the padding of the actor’s belly and rump, which seems to have been a frequent practice augmenting the general sense of grotesqueness. A visible phallus was a conventional appendage for male characters; it could be more or less prominent (cf. Clouds 537–9) and lent itself to stage business of various kinds (e.g. Women at the Thesmophoria 62, 239–48, 638–48, 1187–8). Those three accoutrements of the comic performer—(grotesque) mask, padding, and phallus—must have created a pervasive and inescapable sense of vulgar absurdity for Athenian audiences, ensuring that the action of a play was always visually suspended in a kind of misshapen world of its own.

The chorus, as mentioned in previous sections, consisted of twenty-four singers/dancers, including a chorus-leader who spoke and declaimed certain sections solo, especially when in dialogue with individual actors. Many of the choral dance-sections took symmetrical strophic form, involving the musically and rhythmically matching pairing of strophe and antistrophe, as indicated in the margins of my translation. Musical accompaniment was provided by a piper, whose instrument was a pair of auloi or reed-pipes (akin to oboes). Comedy sometimes draws the piper temporarily into the sphere of the dramatic action, as with the sounds of Prokne at Birds 209 ff., Euripides’ use of Teredon as part of his ruse at Women at the Thesmophoria 1176 ff., or the old hag’s address to the player at Assembly-Women 890–2.

When the plays of Aristophanes were written down, they contained, like virtually all ancient dramatic texts, no stage directions. We are therefore left to make our own inferences about the kind of staging which they could or would have been given, guiding ourselves, wherever possible, by other sources of information about the Athenian theatre. So the reader of this, as of any other, translation of Aristophanes (or of Greek tragedy) should keep in mind that all stage directions are a matter of interpretation, not independent fact, even though a fair number of them can be established uncontroversially, and more still can be persuasively justified from clues in the text. Readers should themselves cultivate the habit of picturing the realization of the script in an open-air theatrical space, and by a cast of grotesquely attired players, of the kind described above.

Featured image credit: “Greece, Athens” by michelmondadori. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Aristophanes: Frogs and other plays [extract] appeared first on OUPblog.

Mental health at all ages

This May, Mental Health Awareness Month turns 68. To raise awareness of the fact that mental health issues affect individuals at all stages of the life course, we have put together a brief reading list of articles from The Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences Series B. These articles also explore aspects of mental health that may be under-appreciated in the traditional social psychological literature as they address sociological theories, the roles that institutions, culture, and social structure play in shaping mental health.

The Impacts of Service Related Exposures on Trajectories of Mental Health Among Aging Veterans by Stephanie Ureña, Miles G. Taylor, and Ben Lennox Kail in The Journals of Gerontology: Series B.

One of the great lessons from life course sociology is that early life conditions affect late life health outcomes. This is as true for physical health as it is for mental health. As a result, psychological traumas experienced early in life can have long-term mental health repercussions in old age. Take wartime combat exposure, for example. Urena, Taylor, and Kail (2017) report that WWII and Vietnam veterans who witnessed the mortal injuries of others during combat experienced greater and longer-lasting psychiatric problems in late life when compared to veterans that did not experience these traumas. Their paper is an example of how sociological factors–institutionalization, social structure, and conflict between world powers–can have substantial consequences on mental health and well-being in entire cohorts over long spans of time.

Widowhood and Depression in a Cross-National Perspective: Evidence from the United States, Europe, Korea, and China by Apoorva Jadhav and David Weir in The Journals of Gerontology: Series B.

While mental health issues are inherently intimate and personal they also span relationships through social connections. Disruption to social networks, can be a source of depression and feelings of isolation as people age. Jadhav and Weir (2017) reveal that such disruption, vis-a-vis the death of a spouse, can lead to long-lasting depression that differs in trajectory for men and women. Interestingly, their paper demonstrates strong evidence that such interpersonal trauma affects people similarly across very different cultural contexts, suggesting that the links between depression and widowhood are global. Moreover, their findings suggest that interventions targeting the alleviation of depression following the loss of a spouse should focus on different aspects of symptoms for men and women.

Passive Suicide Ideation Among Older Adults in Europe: A Multilevel Regression Analysis of Individual and Societal Determinants in 12 Countries (SHARE) by Erwin Stolz, Beat Fux, Hannes Mayerl, Éva Rásky, and Wolfgang Freidl in The Journals of Gerontology: Series B.

Mental health and psychiatric issues are especially concerning when those problems lead to physical injury and death. Crude rates of suicide are highest after middle age and remain high well into late life. One indicator for the risk of suicide is having passive suicidal ideation–fleeting thoughts of killing oneself that are relatively common in old age. Stolz, Fux, Mayerl, Rasky, and Freidl (2016) evaluated whether regional differences (by European country) or individual differences better predict passive suicidal ideation among older respondents to the Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe. Their question is as old as sociology itself: Durkheim famously described regional variation in crude suicide rates across Europe. Stolz et al., however had the advantage of individual-level data that Durkheim did not: for the most part, regional variation was found to play only a minor role in passive suicidal ideation, with most of the effect explained by individual-level factors (such as being in poor health, having a history of psychiatric problems, and being socially isolated). By identifying significant predictors of having these thoughts, medical and social welfare professionals may be able intervene earlier in the lives of aging people.

Long-Term Effects of Age Discrimination on Mental Health: The Role of Perceived Financial Strain by Tetyana P. Shippee, Lindsay R. Wilkinson, Markus H. Schafer, and Nathan D. Shippee in The Journals of Gerontology: Series B.

Reducing the stigma and discrimination experienced by people affected by psychiatric problems is one of the goals of Mental Health Awareness Month. In old age, such stigma may be compounded by age-discrimination, leading to a double-jeopardy situation for declines in well-being for older adults. Recent work by Shippee, Wilkinson, Schafer, and Shippee (2017) investigated the effect that long-term exposure to age-discrimination among workforce participating women had on later-life depressive symptoms and life satisfaction. They found that, while there was a direct negative effect of experiencing age-discrimination in the workforce on depressive symptoms, this was partially offset by perceived financial strain: worrying about money partly explained having more depressive symptoms. Holding worry about finances aside, reducing age-discrimination in the workplace may alleviate some of the causes of depression in an aging workforce, improving productivity and well-being along the way.

Using and Interpreting Mental Health Measures in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project by Carolyn Payne, E. C. Hedberg, Michael Kozloski, William Dale, and Martha K. McClintock in The Journals of Gerontology: Series B.

Finally, an important and easily accessible way to advance awareness of mental health conditions across the life course is to support ongoing longitudinal research on the subject. To that end, Payne, Hedberg, Kozloski, Dale, and McClintock (2014) describe five unique measures of mental health status used to assess older adults born between 1920 and 1947 in Waves 1 and 2 of the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP). These included age validated scales of depressive symptoms, happiness, anxiety symptoms, perceived stress, and feelings of loneliness. In their summary of preliminary findings from the data, they report remarkable stability of these measures within individuals over time. This suggests that, among the population of community-dwelling older adults, mental health status may be representative of long-term well-being and not of episodic spells varying between good and poor outcomes over time. If you’re interested in using the data to address your own questions about aging and mental health, this dataset is available to the public for use in research and teaching.

Featured image credit: Adult Affection Eldery by Matthias Zomer. Public domain via Pexels.

The post Mental health at all ages appeared first on OUPblog.

What more can could be done to protect the protectors?

“Something that ought not to be happening and about which someone had better do something now”. In 1974 this was the definition given to the policing mission by US Sociologist, Bittner. We can debate it but it neatly captures the complexity and dangers that police face every day.

Whatever people view of the police, in the UK, when the wheel starts to come off the police will be called – they are always the bottom line. Bittner went on say that policing is like Florence Nightingale being in pursuit of Wille Sutton (a famous US robber). It’s not a bad metaphor of the public expectations of policing. We will never eliminate risk to police officers, similarly you can’t have police officers dressed like Power Rangers all the time. So where is the balance between scrutiny and empowerment? Where is the balance between officer protection and police officers representing the community they serve?

Where we can start is looking at these questions not ideologically but based on evidence. Let’s accurately measure what and where the threat is, let’s next understand what intervention mitigates that threat, and importantly what are the consequences of that intervention? Stress, shifts, assaults, exposure to child abuse imagery, being subject to sometimes vexatious complaints – accurate measurement of these factors is the first thing that needs to happen – and then understanding what interventions are effective. Here is a great example when West Midlands Police was looking at how and whether we should invest in Body Worn Video (the debate around BWV all feels very yesterday but at the time it was live). A response shift Inspector called Darren Henstock (now been pinched by Western Australia Police) decided to work out what the effects of BWV would be. Rather than opine in the finest traditions of experience-based policing, he decided to test. Linking in with Barak Ariel from Cambridge University he randomly allocated shifts to use body worn videos and then not. Once he had enough data he looked at aggregated outcomes for all those shifts when there was body worn videos and when not. Figure 1 shows the result.

Graph produced by Alex Murray. Do not re-use without permission.

Graph produced by Alex Murray. Do not re-use without permission.Use of force was much less when the video was on. Further to that, when the video was off, there were 10 complaints, and when on…zero. And a 12% increase in charges. I am not sure why (further evidence comparing results over many different experiments nuances this picture). Do the cameras moderate the public’s behaviour or vice versa? The difference was clear all the same. This evidence informed the decision makers about investment decisions – because it was not opinion, or even correlation – but a causal link between a tactic (video) and an outcome (safety).

It is perhaps not fair to compare the firearms issue in the UK and the US because of the wholly different contexts – but just look at what a UK based firearms operations needs to go through before deployment. Is the subject with the gun emotionally or mentally distressed? How will your tactic ameliorate risk then (i.e. back off without exposing others to harm)? Are you going to pursue the offender (mostly no, because of the huge risk to the public)? The tactical firearms commander assesses risk on all groups including the subjects and potential victims – they have a tactical advisor and have to get the agreement of a senior officer before launching an operation. How do we minimise risk to others whilst maximising the safety of police officers in this firearms operation? This is the central concern – rightly – of the commanders. Being unfair then – is there a similar process across the 12,135 US police agencies who use guns, or could there be opportunities to reduce the death rate of both police officers and citizens? I don’t know, but there could be.

Let’s start with the evidence then. This is what we need to know and use if we are going to protect the protectors…

Featured image credit: Met Officers. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What more can could be done to protect the protectors? appeared first on OUPblog.

May 21, 2017

A photographer’s guide to solar eclipses

On 21 August, millions of Americans will flock to a narrow strip along the country – the path of totality – to witness a rare event: a total solar eclipse. Many will try to capture the beauty of the phenomenon in their minds, but a great number will attempt preserving physical documentation of the eclipse. The following shortened excerpt from Totality: The Great American Eclipses of 2017 and 2024 shares photography tips for the upcoming 2017 total eclipse to help enthusiasts make the most of this event.

How do you capture the spectacle of a total eclipse with a camera? Photographing an eclipse isn’t difficult. It doesn’t take fancy or expensive equipment. You can take a snapshot of an eclipse with a simple camera (even a smartphone) if you can hold the camera steady or place it on a tripod.

The first step in eclipse photography is to decide what kind of pictures you want. Are you partial to scenes with people and trees in the foreground and a small but distinct eclipsed Sun overhead? Or do you prefer a closeup in which the radiant corona or vivid red prominences of the eclipsed.

Sun fill the frame? Your decision will determine what kind of equipment you need.

New technologies in cameras and electronics are making eclipse photography easier than ever before. Even beginners can take great eclipse photos with some careful planning. Planning is the key. The day of the eclipse is not the time to try out a new tripod or lens. You need to be completely familiar with your camera and equipment, and you need to rehearse with them weeks before the eclipse. A total eclipse grants you only a few precious minutes and everything must work perfectly. Nature does not provide instant replays.

Digital Photography

In less than a decade, digital cameras have revolutionized the way we shoot pictures. The price of electronic image sensors and memory cards has plunged while the ability to capture fine detail has leapt into many megapixels. The result: Digital cameras have completely replaced film cameras. But perhaps you are too young to remember film cameras! Back in the old days of film, eclipse photographers had to carefully pace themselves because there were only 36 exposures on a roll of film. To capture the diamond ring effect at the beginning of totality, the corona during totality, and the second diamond ring at the end of totality, you had to take pictures sparingly to make your film last. Today, with a large memory card, you can shoot hundreds of digital eclipse images in a few minutes and see your results immediately after totality ends.

Simple Cameras

Point-and-shoot or compact cameras are the simplest digital cameras you can buy. They usually have autofocus lenses, automatic exposure modes, and a small built-in flash. Although the most basic cameras have a single-focal-length lens, more advanced models include a zoom lens.

Many point-and-shoots are small enough to fit in a pocket, making them perfect for snapshots of vacations, parties, and other events. They are popular with people who do not consider themselves photographers but want an easy-to-use camera.

Smart phones are rapidly replacing point-and-shoot cameras as the most popular type of digital camera. These ingenious devices were the stuff of science fiction only a decade ago. Besides shooting photos, they have downloadable applications or apps for almost everything imaginable: texting, e-mail, web browsing, music, games, and alarm clock, just to mention a few. You can even use them to make phone calls! Both point-and-shoots and smart phones are great for capturing simple snapshots of an eclipse. You can also use them to shoot a panorama around the horizon during totality. Although you can handhold either one, a tripod is a better choice for support, especially during the subdued twilight of totality. Point-and-shoots have a threaded socket on the bottom for tripod attachment, while smart phones will require a special bracket to securely attach them to a tripod.

After the eclipse, you can quickly review your photos. Of course, a smart phone also lets you share them immediately with friends and family via Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Flickr.

Diamond ring effect

This hand-held shot of the diamond ring effect was made from the deck of rocking ship in the Pacific Ocean during the total solar eclipse of April 9, 2005.

Nikon D100 DSLR, Sigma 170-500 zoom lens, fl = 400 mm, f/6.3, 1/1000 second, ISO 800. ©2005 Patricia Totten Espenak

Moments before totality

This diamond ring effect is captured 10 seconds before totality begins during the total solar eclipse of August 1, 2008, from Jinta, China.

Nikon D300, Vixen 90 mm fluorite refractor, fl = 810 mm, f/9, 1/250 second, ISO 320. ©2008 Fred Espenak

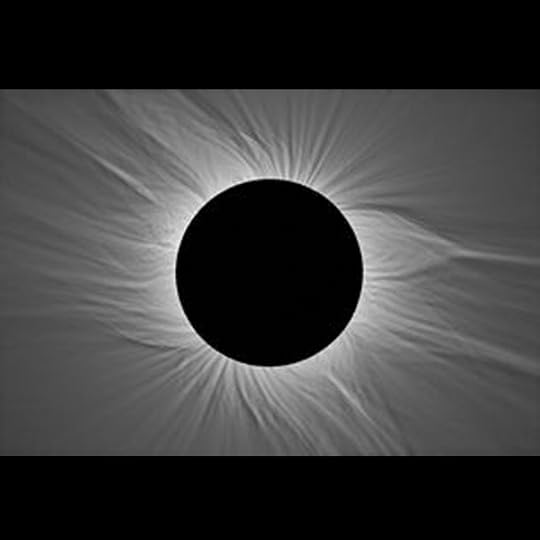

Details in the corona

Details in the corona are revealed in this Photoshop composite that was processed to emphasize fine structure. The images were obtained during the March 29, 2006, total eclipse from Jalu, Libya.

Nikon D200 DSLR, Vixen 90 mm fluorite refractor,

fl = 820 mm, f/9, composite of 22 exposures: 1/1000 second to 1 second, ISO 200. ©2006 Fred Espenak

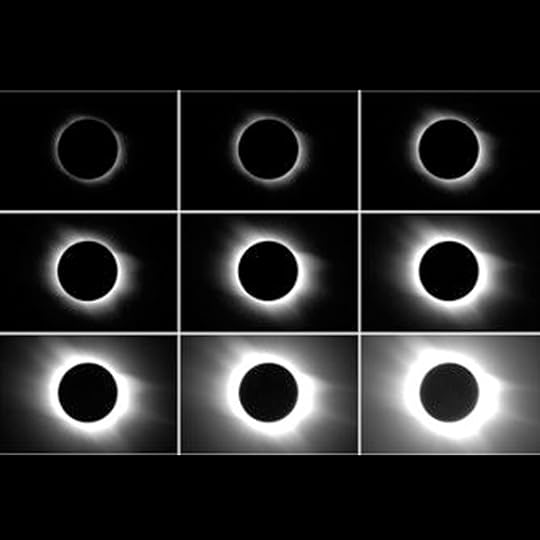

Sequence of Libyan eclipse

Some photographers shoot a series of exposures to capture the wide range of brightness in the corona. This sequence was made with a DSLR during the March 29, 2006, total solar eclipse from Libya.

Nikon D200 DSLR, Vixen 90 mm fluorite refractor, fl = 810 mm, f/9, 9 exposures: 1/125 to 2 seconds, ISO 400. ©2006 Fred Espenak

Large sunspot visible during partial solar eclipse

The photosphere of the Sun has sunspots that vary in number and size over an 11-year period. The biggest sunspot to grace the face of the Sun in more than two decades just happened to be visible during the partial solar eclipse of October 23, 2014. The sunspot was as big as the planet Jupiter. The enormous

amount of energy stored in its twisted magnetic fields was responsible for producing several major solar flares.

Vixen 90 mm fluorite refractor, fl =

810 mm, f/9, 1/2500 second, ISO 100, Thousand Oaks Type III filter, ©2014 Fred Espenak

Early mythology

To many early people, the eerie twilight sky of totality was interpreted as the end of the world. A wide-angle view of totality was shot from Dundlod, India, on October 24, 1995.

Nikon FE SLR, Nikkor 50 mm, Ektachrome 100, f/5.6, 1/4 second. ©1995 Fred Espenak

Safely projecting images with binoculars

Binoculars can be used to safely project a magnified image of the Sun onto a piece of white cardboard. Never look at the Sun directly through binoculars unless they are equipped with solar filters.

©2000 Fred Espenak

Eye safety during solar eclipses

Inexpensive eclipse glasses are a great way to share the eclipse with others and make new friends. Bring extras to hand out on eclipse day.

©1997 Fred Espenak

Landscape Eclipse Photography

The easiest way to capture the eclipse is to take a few wide-angle shots of the sky, horizon, and landscape before, during, and after totality. This sequence might show the Moon’s dark, fast-moving shadow approaching from the west or racing away over the horizon to the east. Place yourself or some other interesting subjects in the foreground to give the photos some scale. If your camera has a zoom lens, the widest-angle setting will produce the most dramatic images. Your camera’s built-in auto-exposure feature should work well. Just be sure to turn off the automatic flash feature so you don’t annoy observers nearby. If your camera has an exposure bracketing feature, use it for insurance to get the best exposure of the total eclipse. You’ll also capture any bright planets near the Sun during totality.

You might even discover a new comet!

Photographing Pinhole Crescents

Eclipses provide other phenomena that make interesting pictures, such as the crescent images of the partially eclipsed Sun produced by tree foliage. The narrow gaps between leaves act as “pinhole cameras” and each projects its own tiny (and inverted) image of the crescent Sun on

the ground. This pinhole camera effect becomes more pronounced as the eclipse progresses. You can make your own pinhole camera to project the crescent Sun with pinholes punched in thin cardboard, or with a wide-brimmed straw hat.

You can even produce the effect in the shadow of your hands by loosely lacing your fingers together. Watch the crescents form when the light passes through the gaps between your fingers. The profusion of crescents on a white wall or on a person’s face makes a nice photographic memento. Once again, you’ll want to disengage the automatic flash on your camera.

Eclipse Close-Ups

If your goal is to shoot close-ups of the Sun and Moon during the eclipse, a little more effort is required. These kinds of eclipse images are more challenging than wide-angle landscapes and pinhole crescents. You will need a more expensive camera, a powerful telephoto lens or small telescope, a strong tripod and a special solar filter (for partial phases only).

Successfully capturing magnified views of the eclipse also requires a basic understanding of how digital cameras work as well as careful planning and preparation before eclipse day.

All slideshow images were provided by Fred Espenak and Patricia Totten Espenak. Please do not use without permission.

Featured image credit: ©2006 Patricia Totten Espenak.

The post A photographer’s guide to solar eclipses appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers