Oxford University Press's Blog, page 358

June 7, 2017

Accommodating religion in the workplace

In March, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) generated controversy (and confusion) when it ruled that a workplace ban on wearing the Islamic headscarf did not necessarily constitute direct discrimination. Employers could not single out Muslim employees, the ECJ found, but they could enforce general policies restricting religious dress so long as they applied equally to all.

This issue has played out differently in the US In a 2015 decision, for example, the US Supreme Court found that the retail clothing company, Abercrombie & Fitch, had violated Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by refusing to hire a female applicant who wore a headscarf. The store’s managers were concerned about having to accommodate her under a company policy that prohibited all employees from wearing “caps” in the workplace. But, the Court explained, it was not enough for all workers to be treated in the same way, for Title VII did not demand “mere neutrality.” Instead, it promised religion “favored treatment” by prohibiting employers from refusing to hire an individual “because of such individual’s religious observance and practice.’” By taking this applicant’s prospective need for a religious accommodation into account, Abercrombie had run afoul of US law.

In recent years, the private workplace has emerged as a critical site for working out issues of religious difference in pluralistic societies. Workplace discrimination complaints have spiked over the last decade, thanks to a range of factors, including globalization, changes to immigration laws, post-9/11 Islamophobia, public Christian evangelism, Baby Boomer “spiritual seeking,” and the “new” politics of religious freedom. Employees have sought accommodations for special clothing and attire, food and dietary practices, prayer and festival observance, decorations in personal workspaces, and refusing to fulfill certain tasks, like selling contraception or alcohol. As the two cases cited above make clear, different countries have regulated these issues in different ways, reflecting different underlying assumptions about how best to manage religious differences in ostensibly secular societies.

Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, as amended in 1972, requires US employers to provide “reasonable accommodations” for the religious beliefs and practices of their employees unless doing so would create “undue hardship on the conduct of the employer’s business.” US law thus promises relatively robust protection for the religious rights of American workers. It also places workplace managers in a surprisingly precarious position, forcing them to make a number of delicate but fraught determinations. How far must they go in accommodating their employees? What constitutes “undue” hardship? And how should they assess which employee claims are valid? How are they to know, for example, whether a male employee actually “needs” to grow a beard, and whether he does so for “religious” reasons or others? According to settled case law, beliefs and practices qualifying for accommodation need not be logical, comprehensible, or widely shared. They must only be “sincerely held.” Yet how ought an employer determine the “sincerity” of her employees?

In part for these reasons, religion has typically appeared in scholarship on workplace diversity as a problem, requiring careful management and delicate negotiation. The literature makes clear that employers should tread cautiously in deciding what counts as a legitimate claim, how to go about accommodating it, and how to handle intra-workplace conflicts when they arise. Given all the potential pitfalls, managers might be forgiven for thinking of religion primarily as a disruption, as an obstacle to the proper functioning of business, and thus best left at home.

Yet there has been a notable shift in recent years. Business scholarship has grown more attentive to religion, urging corporate leaders to “take religion more seriously” and make space for its practice. Employers have made more proactive efforts to create inclusive environments in which workers might more readily reconcile their commitments to work and faith. Businesses have hired workplace chaplains, created designated interfaith prayer spaces, introduced more flexible work schedules, and adopted policies encouraging co-workers to step in when an employee is unable to carry out their responsibilities for religious reasons. A recent article in Bloomberg News, for example, specifically noted the rise of “Muslim-friendly workplaces in corporate America.” More and more, it seems, businesses have been treating religious diversity not as a problem to be managed but as a resource to be capitalized.

There are a variety of factors accounting for these shifts. Most notably, they stem from what Winnifred Fallers Sullivan has described as the “naturalization” of religion, or the shift from legal separationist paradigms to more formal acknowledgment of spirituality as a universally shared feature of human life. They also reflect what Mariana Valverde has described as a shift in contemporary discourse about diversity, from a “rainbow nation” notion grounded in a commitment to social justice to a “neoliberal” or “corporate” model, which interprets diversity as a resource to be capitalized for maximum efficiency and gain in a competitive marketplace. According to this conception, accommodating religious differences becomes less a problem or challenge and more a sign of effective management, even a means for promoting a more productive labor force. Accommodating religious diversity is understood not just as a way of meeting a legal mandate, but of bolstering the bottom line. Accommodations function as a sign of the corporation’s own good faith, a marker of its status as a conscientious employer. They become part of what it means to run a good business.

These trends are mostly worth celebrating, as they manifest a distinctly American commitment to pluralism and religious liberty. Yet it is also worth taking seriously their unintended consequences, to ask, for example, what it means when employers are understood as having an important role to play in bolstering and nurturing the religious commitments of their employees, or to consider how proactive policies might encourage workers to bring their religion to work in ways they otherwise might not have done. In other words, we ought to interrogate the possibility that “taking religion seriously” could give rise to the very conflicts that accommodations are meant to resolve.

It is unclear how these issues will play out, but they are worth our close attention, especially as American workplaces continue to grow more “diverse,” and as more and more sectors of society are encouraged to operate like “businesses.” What, precisely, will we ask of our nation’s leaders, and what will this mean for the accommodation—and production—of religious differences?

Featured image credit: Image by Jerry Seon, CC0 Public domain Pixabay

The post Accommodating religion in the workplace appeared first on OUPblog.

June 6, 2017

Dying to prove themselves

The Wonder, the latest work of Irish-Canadian author Emma Donoghue to light up the fiction best sellers’ list (Donoghue’s prize-winning 2010 novel Room was the basis for the 2015 Academy-Award winning film), draws upon a very real, very disturbing Victorian phenomenon: the young women and men—but mostly pubescent females—who starved themselves to death to prove some kind of divine or spiritual presence in their lives. One person quite prepared to believe in the truth of a “fasting girl” was the English poet and Jesuit priest, Gerard Manley Hopkins.

Hopkins was introduced to the religious efficacy of closely restricting or refusing beverages and food in the writings of Reverend Edward Pusey and John Henry Newman, who, as Anglican members of the “Oxford Movement” (or Tractarians), published tracts advocating the benefits of physical mortification. As an Oxford undergraduate in the early 1860s, Hopkins read both Pusey’s 1833 Thoughts on the Benefits of the System of Fasting (Tract 18) and Newman’s 1833 Mortification of the Flesh a Scripture Duty (Tract 21, also given as a sermon). In the latter, Newman recommended fasting as a necessary means of “humiliation” and a bodily “duty.” After converting to Roman Catholicism in 1866 (Newman ‘received’ Hopkins into the Church) and joining the Society of Jesus in 1868, Hopkins embraced any and all opportunities to master his body’s needs and desires—to the point where Jesuit superiors had to restrict his self-punished practices. (Hopkins first proved his ability to abstain from fluids as a young student at Highgate School, where, according to his brother Cyril, he refused water for a week).

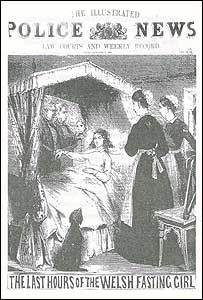

In his diary for Winter 1870, Hopkins lists several important “events” from the last few months of 1869, including “Dec. 17— Fasting girl died: her parents were afterwards convicted of manslaughter.” As always, Hopkins had an eye for sensational news stories. Sarah Jacob (12 May 1857–17 December 1869), the daughter of Welsh Roman Catholic farmers in the Dyfed village of Llanfihangel-ar-arth, claimed not to have eaten any food for almost two years. On 10 October 1867, reportedly, she ceased to eat; bed-bound, she dedicated herself to religious reading and prayer. She was seen “lying on her bed, decorated as a bride, having round her head a wreath of flowers” (“Fasting Girls,” All the Year Round, no. 45, 9 October 1869). Pilgrims came to visit, assuming that Sarah’s life was miraculous; tributes of flowers and coins were presented. Articles in The Times and the Lancet, however, were explicitly critical and implicitly anti-Welsh and anti-Catholic.

Image Credit: ‘Sarah Jacob’ from news.bbc.co.uk, Public Domain via Wikipedia.

Image Credit: ‘Sarah Jacob’ from news.bbc.co.uk, Public Domain via Wikipedia.In late 1869, her parents were pressured to agree to a “Watchers’ Committee” consisting of medical people from London’s Guy’s Hospital and a local vicar to ensure that she was not receiving food surreptitiously. After eight days of strict supervision, she died. Following her death, there was an inquest; the verdict, “Died from starvation, caused by negligence”, resulted in her parents, Hannah and Evan Jones, being charged with manslaughter (members of the ‘Watchers’ Committee were exempt from criminal allegations). Found guilty at trial, Hannah and Evan Jones were sentenced to six months and twelve months of hard labour, respectively. The Times suggested that Sarah Jones suffered from “simulative hysteria” and added that if she “had chanced to be born in some corner of France or Italy in which Romanism flourished unchecked, her prolonged fasting, after a great devotion to religious reading and a pious submission to ecclesiastical ordinances, would have assumed all the circumstances of a miracle” (“A Strange and Obscure Story,” The Times, 18 December 1869).

The Victorians did not invent extreme “fasting,” of course: ancient, biblical, and medieval examples of severe askesis were plentiful. In the later nineteenth-century, among commentators claiming a socio-scientific expertise on the subject were Robert Fowler, who published ‘The Fasting Girl of Wales’ in The Times (7 September 1869) and A Complete History of the Welsh Fasting Girl (Sarah Jacobs) with Comments Thereon, and Observations on Death from Starvation (1871), and Dr. William A. Hammond, whose Fasting Girls: Their Physiology and Pathology (1879) was designed for American audiences. More recently, Joan Jacobs Brumberg has studied Sarah Jones and those like her in the clinical context of anorexia nervosa: Fasting Girls: The History of Anorexia Nervosa (2000).

From morbid Victorian enthrallment, and even earlier biblical references, to twenty-first-century scholarly studies, the strange fascination with self-mortification is not likely to abate any time soon.

Featured image credit: “Arthur Rackham, Vintage, Book Illustration” from Prawny, CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post Dying to prove themselves appeared first on OUPblog.

A better way to model cancer

Later this year, the first US-based clinical trial to test whether an organoid model of prostate cancer can predict drug response will begin recruiting patients. Researchers will grow the organoids—miniorgans coaxed to develop from stem cells—from each patient’s cancer tissues and expose the organoids to the patient’s planned course of therapy.

If the organoids mirror patients’ drug responses, the results would support the model’s use as a tool to help guide therapy. “We are aiming for a precision-medicine system to treat prostate cancer,” said Hatem Sabaawy, MD, PhD—a co–principal investigator of the trial.

Organoid models were first described more than 40 years ago, but cancer researchers began studying them as better models of cancer only in the last decade. An organoid closely resembles the organ or tissue from which it was derived. Cancer cells grown in a dish—the standard method used to study the effect of cancer therapies—“can’t represent the complexity of cancer,” said Jeremy Rich, MD, of the department of stem cell biology and regenerative medicine at Ohio’s Cleveland Clinic Lerner Research Institute. Those conventional models are two-dimensional and bear little physical, molecular, or physiological similarity to their tissue of origin. With the high failure rate of cancer drugs in clinical trials, existing models do a poor job of predicting how patients will respond to treatment, he added.

Several research groups have shown that organoids grown from a patient’s own tumor cells mirror those tumors in terms of genes and other biochemicals expressed. Those findings suggest that such models can help guide personalized treatment decisions, Sabaawy said. Organoids from cancer tissues can be grown within 2–3 weeks and frozen for later study.

The prostate cancer clinical trial, which will take place at the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey in New Brunswick, will exploit tissues removed from patients with advanced metastatic prostate cancer. Researchers will sequence the DNA of each cancer tissue to create its molecular profile. They will also extract stem cells to grow organoids, which they will treat with the same therapy devised for the patients. Researchers will see whether using organoids can predict how patients will respond to treatment. The results will become part of a biobank of clinical profiles that will serve as a resource for future patients.

A similar trial of colon cancer patients in the Netherlands is ongoing, said Hans Clevers, MD, PhD, director of the Hubrecht Institute in Utrecht, Holland, and founder of Hubrecht Organoid Technology. Though results from the first few patients look promising, Clevers added, the study is in its early stages. Two more such trials, one in colon cancer and another in breast cancer, will launch in Holland later this year.

“It’s a system where you can test aspects of human biology that you can’t test in a dish.”

But although organoids hold hope of taking some guesswork out of cancer treatment, they don’t completely model cancer behavior in the body. Because they have no immune system or blood vessels, organoids can’t be used to evaluate whether immunotherapies or angiogenesis blockers will work, nor can they hint at whether a patient’s immune system will help or hinder cancer. To address those concerns, some researchers are using tests on mice to complement organoid models. Sabaawy, for example, is working with colleagues to implant patient-derived colon cancer organoids into mouse colons. The mice have been engrafted with a human immune system by using bone marrow cells from the same patient. The mice could serve as predictive models of immune therapy for each patient, he said.

Jatin Roper, MD, director of the Center for Hereditary Gastrointestinal Cancer at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, is working on a mouse model of human colon cancer as a research tool. Growing human colon organoids in mouse colons, where they are exposed to other cells found in the colon, allows researchers to observe the cancer in a more natural environment, he said. In his model of immune-deficient mice implanted with human-derived organoids, Roper has observed colon cancer metastasizing to the liver, which often occurs in human colon cancer. “It’s a system where you can test aspects of human biology that you can’t test in a dish,” he added. Roper and others are also using the gene-editing technology CRISPR (clustered, regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) to induce specific mutations into organoids and then implanting them in mice to better understand how they drive cancer.

Such research has already highlighted cancer’s complexity. When Clevers grows organoids from different cancer cells from the same patient, he often sees some clones that are resistant to all drugs, even in patients who have never been treated. “The level of genetic diversity in these tumors is frightening,” he said. “It will be extremely difficult to find a cure.”

Nevertheless, better models can help tailor cancer therapy to each patient, reducing unnecessary treatments and the anxiety of waiting to learn whether a therapy worked. Clevers sees organoids playing a role in making targeted drugs more precise. Most chemotherapy drugs used in the clinic are not specific to any kind of mutation, he said. For older therapies, Clevers said he hopes that organoids can be used to help separate responders from nonresponders. Having the “tumor cells literally in our hands” offers many advantages, he said.

A version of this article originally appeared in the Journal of the Nation Cancer Institute.

Featured image credit: Intestinal organoid grown from Lgr5+ stem cells. St Johnston D (2015) The Renaissance of Developmental Biology. PLoS Biol 13(5): e1002149. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1002149 by Meritxell Huch. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A better way to model cancer appeared first on OUPblog.

How well do you know the Hollywood musical? [quiz]

In Hollywood Aesthetic: Pleasure in American Cinema, film studies professor Todd Berliner explains how Hollywood delivers aesthetic pleasure to mass audiences. The following quiz is based on information found in chapter 11, “Bursting into Song in the Hollywood Musical.” The chapter traces the history of the convention that characters in Hollywood musicals burst into song without realistic motivation. And it studies the ways in which Hollywood filmmakers developed novel conventions, in both musicals and non-musicals, that exploited the aesthetic possibilities of song in cinema.

How well do you know this popular Hollywood genre? Put your knowledge to the test with the quiz below.

Quiz image credit: Billie Burke and Judy Garland The Wizard of Oz. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image credit: Hollywood sign. Photo by Thomas Wolf. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How well do you know the Hollywood musical? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

June 5, 2017

Presidential pensions as broken windows

The complex (and often tragic) saga of post-presidential retirements is well-known. Some presidents, such as Herbert Hoover, were independently-wealthy and thus spent their years after the White House in economic security. Other presidents, such as Woodrow Wilson, lived only briefly after their service in the Oval Office.

Yet other former presidents experienced great financial difficulties in retirement. The story of Ulysses Grant’s post-presidential travails is an iconic part of American history: at the end of his life, dying of cancer, an impoverished Grant wrote his now-celebrated memoirs to provide posthumously for the wife he adored.

Congress first authorized presidential pensions in 1958 in response to reports of President Truman’s financial problems in retirement. We now know that Truman’s economic situation was more complex than it appeared at the time: Truman had received substantial payments for his memoirs. But Truman declined most opportunities for post-White House remuneration as degrading the presidency and his post-presidential income was quite minimal.

Today, the presidential retirement package is generous. Former presidents receive for the rest of their lives the annual salary of a cabinet officer, today it is $207,800 per year. Former presidents also receive taxpayer-provided offices and office staffs as well as Secret Service protection. President Gerald Ford broke the Truman-mold of former presidents eschewing compensated employment to protect the dignity of the presidency. After leaving the White House, Ford aggressively sought income-producing opportunities.

If President Ford redefined the post-presidency, President Bill Clinton took the income of a former president to new and controversial levels. And now former President Obama seems to be opening the door to the Ford-Clinton approach. Published reports indicate that Mr. Obama will deliver a speech to the Wall Street firm Cantor Fitzgerald for $400,000. Harry Truman would not have approved.

Why should federal taxpayers pay a post-presidential pension to a former President who is willing and able to enrich himself after he leaves the White House? The rationale for presidential pensions was to prevent the financial straits which Grant and Truman experienced, not to provide a taxpayer-financed platform from which to pursue a post-White House fortune.

Perhaps, it might be retorted, the presidential pension, while an ample retirement for most of us, is small potatoes in a federal budget measured in hundreds of billions of dollars. But the presidential pension presents the classic case of a “broken window,” the relatively small incident which suggests deeper disarray.

The same “broken windows” effect occurs when former state legislators manipulate state pension laws, taking short-term but highly paid state executive positions to boost their retirement pensions.

Such manipulation of state pension systems, like presidential retirement payments, may be a tiny fraction of total government pension costs. But the message being conveyed to the hardworking taxpayer is the same: The system is stacked against you. Just as state pension systems should be reformed to prevent state legislators’ late career pension spikes, the presidential pension should be modified to account for the reality that some former presidents choose to monetize the aura of the presidency. In any year when a former president’s outside income exceeds some threshold amount (e.g., $200,000), his or her pension and office allowance should decrease by fifty cents for each dollar earned above this threshold.

Under this, or any similar formula, former presidents would remain generously compensated for their service to the nation. But, when such presidents make fortunes unfathomable to most Americans, they should return to the federal fiscal part or return all of the taxpayer’s subsidy designed to keep them from being impoverished.

This is a broken window which can be fixed.

Featured image credit: The Oval Office by US National Archives and Records Administration. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Presidential pensions as broken windows appeared first on OUPblog.

Saving old forests

Sustainable forestry aims to maintain wood supply whilst preserving biodiversity and the integrity of the ecosystem. Research shows that boreal forests, like those across much of Northern Europe and Canada, have higher levels of variability in their structure and dynamics when unmanaged, improving their biodiversity and the stability of their ecosystems. These unmanaged forests also have a higher proportion of older trees than those used in industrial forest rotation – around 70-100 years in Canadian boreal forests.

Why should we maintain old forests?

Old forests are important in terms of sustainability, as larger trees have a more complex structure, and provide more dead wood vital for certain aspects of the ecosystem. Old forests are gradually decreasing across the world as demand for wood supply increases, and the majority are located in boreal and temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere. Many species of these forests are red-listed in Fenno-Scandinavia, partly because intensive silviculture has eliminated most of the old forests in these areas.

North American boreal forests

In North America, the increased demand for wood products has led to the expansion of commercial logging activities towards fire-sensitive northern boreal regions. Despite recognition of the importance of preserving old forests, forest management in these regions still predominantly employs clear-cut harvesting – a method of forestry in which all the trees in an area is cut down – with short rotations relevant to the average intervals between natural disturbances. However, it is unlikely that these forest ecosystems will be able to sustain these rates of logging and fire disturbances. According to current research, if rates of both continue, by 2050 the proportion of old forests could reach a minimum level rarely or never seen in the natural landscape in the past.

Impact of climate change

The situation is set to become even more critical, as with current rates of climate change, in the best case scenario, fire activity is projected to double. Indeed, the predicted global climate will not only be warmer, but also more prone to summer drought events. With an earlier thaw in spring, higher summer temperatures, and changing levels of precipitation, soil will be drier for longer and therefore more prone to fires. These conditions also increase the likelihood that fires will burn hotter, and for longer, increasing the amount of damage caused. Climate change will therefore probably reduce the trade-off space currently existing between supply targets for profitable forest industry and biodiversity conservation. However, further results indicate that with the current rate of harvesting, the predicted decrease in old forest has more to do with clear-cutting than increased fire activity. Maintaining old forests to a minimum sustainable value would require significant reductions of clear-cut harvesting, which will have an important economic impact.

Burnt Forest at Rocky Point Trail of Glacier National Park USA by Wing-Chi Poon. CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

Burnt Forest at Rocky Point Trail of Glacier National Park USA by Wing-Chi Poon. CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.Old forest as insurance

Not only are old forests important for biodiversity, they also decrease the risk of regeneration failure following fire events. The passage of fire often triggers boreal forest trees to undergo seed release. As a result, the trees need time to replenish their aerial seed banks, the seed stored in a plant’s canopy. Management practices that rejuvenate forests frequently increase the probability that a fire occurs before trees have produced enough cones, which leads to regeneration failure. In view of this, maintaining parts of the landscape as old forest could serve as an insurance policy in an uncertain future.

Moving towards a solution

Mitigating solutions will involve changes in the way forestry is planned, taking into account both wood production and ecosystem durability. Fortunately, it is not too late and several potential solutions exist: increasing rotation length, implementing diversified silviculture, using a fire-smart approach to decrease fire hazard, or improving the balance between intensive management and conservation of old forests. However, current management plans include very few alternatives to clear-cutting. We advocate the rapid implementation of alternative management strategies which would begin to reverse the projected decrease in the proportion of old forests. Without these strategies in place, we may face a future of costly restoration in order to maintain the health of the boreal forest industry.

Featured image credit: Boreal forest by bourgajd. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Saving old forests appeared first on OUPblog.

Church and nature: sex and sin

The Sin of Abbé Mouret reworks the Genesis story of the Fall of Man, with the abbé, Serge Mouret as Adam, and the young Albine his Eve. Fifth of the twenty novels of Zola’s Rougon-Macquart cycle, the novel follows on almost directly from The Conquest of Plassans, in which the young Serge Mouret decides to become a priest.

The novel is divided into three books like the three acts of a tragedy. The opening of the novel takes the reader straight into the central theme of the novel, the conflict between nature and the Church with the celebration of the Mass. The use of an ancient language, the carefully measured, meticulously choreographed ritual, its preordained chants and responses, are set in striking contrast to the unmeasured abundance and freedom of Nature. Trees thrust their branches through the broken windows, cheeky sparrows fly in and flutter about, and Désirée, the abbé’s retarded sister, arrives with an apron full of newly-hatched chicks.

That contrast between regulated Church and unregulated Nature becomes an intense conflict within the abbé himself. His excessive devotion to the Virgin, and his extravagant pursuit of sanctity lead him to deny his own physical nature and every aspect of carnality. Disgusted alike by the fertility of farmyard animals and by human procreation, he yearns for total purity, denying even the basic needs of his body. An encounter with the free-thinking ‘philosopher,’ Jeanbernat, and his wild, untaught, gipsy-like niece Albine, makes a powerful impact on the priest, leaving him haunted and tormented by the memory of the laughing Albine, in her brightly-coloured skirt, and a forest glimpsed through a suddenly opened door. In the Abbé’s consciousness too it seems a door has suddenly opened—a door through which unfamiliar sensations and feelings begin to flow, transforming the very landscape around him into disturbing, erotic shapes. More and more tormented and feverish, his body weakened by his obstinate refusal of its needs, he collapses at the end of Book One, and succumbs to a devastating illness that leaves him with total amnesia.

Book Two takes the reader into a totally new environment, a room in the park of the ‘Paradou,’ where the abbé first saw the girl, Albine. No longer ‘abbé Mouret’, he is now simply ‘Serge,’ a young man recovering from a serious illness, and nursed by an Albine dressed only in white, with her formerly wild hair tied back. Serge has no memory of his previous life as an abbé. His memory now is the memory of an Adam, for whom Albine is the Eve born of his flesh: ‘You were in my chest and I gave you my blood, my muscles and my bones.’ The two fall in love, and this second book becomes a lyrical love poem and a hymn to Nature.

The once ordered and now wild park of the aptly-named Paradou will be the lovers’ paradise, their garden of Eden, and it is a very beautiful, luxuriant garden, filled with every kind of plant, tree and flower. They pick flowers, climb trees, gather fruit and leap across streams of sunlit water. Zola gives lyrical descriptions of this abandoned garden with its extravagantly prolific flowers and foliage. In the midst of this lavish abundance of natural beauty, Zola shows the naïve tenderness of the awakening of love between Serge and Albine, and the first stirrings of sexuality. The changing moods and emotions of the couple are reflected in the descriptions of the garden, where the flowers become increasingly sexualized: roses open out ‘like naked flesh, like bodices revealing the treasures of the bosom.’ Tormented by a frustration, a sense of incompleteness, that they do not understand, the couple’s innocent love turns to anguish, until at last Serge and Albine make love beneath a tree earlier said to be ‘forbidden.’ The whole park, the trees, the grasses, the very sky, all participate in that consummation, a consummation willed by the garden, willed by Nature, whose victory Zola here celebrates. It is the victory of fertility over sterility, of Nature over the Church, but the victory comes at a terrible price. The garden is no longer the safe haven of the lovers; it has been broken into, and the two are driven out like Adam and Eve from Eden. Love has now become Sin. And Serge, through the gap in the wall of the Paradou, hears the church bell that tells of his broken vows, and calls him back to being once more the abbé Mouret.

Book Three opens with cruel irony in a marriage ceremony the abbé is conducting, in the course of which he will speak words about love and constancy to the newly-weds that he had himself spoken to Albine. The end can only be tragic, but the sheer beauty and poetry of Zola’s descriptions of the garden, and the wonderful interweaving of themes and patterns, the swift changes of mood and tone, the sharply contrasting scenes, make the whole novel a deeply moving and enriching experience. This is a richly textured novel, multi-layered, with embedded stories, dreams and hallucinations. With so rich and complex a novel on so fundamental a subject, questions are bound to arise about Zola’s own rather troubled and complex view of sex, and his view of women. In following the story of Adam and Eve, how far is Zola endorsing a view of Eve/Albine as the temptress, and sex as sin? Zola’s long-standing view of maternity and fertility as ideals suggest that he is always on the side of life, and in this novel it is Serge/Adam who is castigated, as Zola rapturously celebrates the fertility of Nature.

The post Church and nature: sex and sin appeared first on OUPblog.

An economist views the UK’s snap general election

There is something unusual about the 2017 UK general election. It is the way in which all the manifestos clearly make their promises conditional on the ‘good Brexit deal’ that they claim to be able to secure. They are not the only ones. On 11 May the Governor of the Bank of England Mark Carney reassured the markets that the ‘good Brexit deal’ would stabilise our economy after 2019, and the markets were duly sedated. So they would like us to think. But all this stands in the way of serious politics.

In fact there is no ‘good Brexit deal’ available. The whole concept says more about the chronic nostalgia of the British public than it does about any differences between the political parties. It is this nostalgia for the state before we entered the European Union that has distracted the British public from the responsibility that should be placed at the door of successive British administrations since 1973, rather than Brussels, for a failing economy and insecure society. For the Europeans, this will be the fourth ‘deal’ that Britain will have secured: the first on entry in 1973; the second under Margaret Thatcher in 1984 when ‘we got our money back’; the third obtained by David Cameron in 2016; and the fourth that is to come resulting from our exit from the European Union.

Our historical record, therefore, cannot reassure our European partners that Britain will not come back for more when things go badly after the deal. After all, Euro-scepticism trades on the notion that our ills are due to the ‘deal’ we got from Europe. Indeed the more our politicians demand that we give them ‘a strong negotiating position’ with Europe, the more they are hedging their electoral promises with the alibi that, if they do not deliver, it will be because we did not give them a sufficiently ‘strong negotiating position’, or they were taken advantage of by the Europeans. And the more our politicians predicate their promises on ‘a good Brexit deal’ the more those promises are unlikely to be fulfilled.

I will still be voting, for whichever candidate can convince me that she or he is seeking relationships rather than deals in Europe.

In this respect the election is not needed at this moment, in particular for the Brexit process which leaves our government only 21 months to settle the complex questions arising out of Brexit. Out of these questions, the more obviously insoluble conundrums are Northern Ireland, where the border promises to reignite civil war; immigration, which owes more to the failure of professional and technical education that none of the political parties have properly addressed; and trade agreements, where any British agreements with non-EU trading partners can only exacerbate any trading agreement with Europe. Trade agreements that we might secure outside the European Union would have to be incorporated in our EU trade agreement because the Europeans would not want us to blow a hole in their customs union.

All of these complexities will come back to haunt us after the election. They indicate that there is no ‘good Brexit deal’ out there. And when the actual deal is exposed, our government, no matter who wins the election, will no doubt place on the table its alibi that we did not give them a sufficiently ‘strong negotiating position’ or they were taken advantage of by Europeans. Maybe our politicians are not so dishonest, but the Euro-sceptics have form on convincing the British public that their problems were created in Brussels rather than Westminster.

In the meantime the great middle class consumption machine continues to power our economy. That it did not shudder as expected after the EU referendum clearly shows, as far as the public is concerned, that all economic forecasts are wrong, so that the marginalised and ‘left behind’ can dream on about the revival of their prelapsarian industrial communities.

I will still be voting, for whichever candidate can convince me that she or he is seeking relationships rather than deals in Europe, and knowing that whoever wins will be losing in the long run. We have an economy that is desperately in need of modernisation, re-equipment, and expansion. But for too long our political establishment has been only too willing to sub-contract economy policy to the City of London, by now a protectorate of the American banking establishment. We have an educational system that dominated by the traditional, non-technical education enjoyed by our political elite, and therefore making our labour market over-dependent on technical education in foreign countries. Finally we have a political establishment dominated by feudal hierarchy and dilettantish schooling.

As long as we are not dealing with the backwardness and dysfunction of our economy and institutions, that backwardness and dysfunction will ensure that the winning promises go unfulfilled. In this situation the promise of the deal that will make things right may be attractive. But in the reality of industrial and economic decline, the art of the deal is an endless cycle of bargain, pact, and regret.

The only way out of the cycle is a durable commitment with our neighbours in Europe to work together to resolve our common problems: the Europe-wide problem of refugees and the civil wars in the Middle East that lie behind the problem of terrorism, the continental-wide coordination necessary for economic revival, and the renewal of the European Social Model.

Featured image credit: Polling Day by cchana. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post An economist views the UK’s snap general election appeared first on OUPblog.

En Marche: Macron’s France and the European Union

On the evening of 7 May, Emmanuel Macron walked, almost marched, slowly across the courtyard of the Louvre to make his first speech as the President elect of the French Fifth Republic. He did so not, as others would have done, to the music of the “Marseillaise” but to the final movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony – the “Ode to Joy”, the anthem of the European Union. It was, wrote Natalie Nougayrède in the Guardian, “the most meaningful, inspiring symbol Macron could choose”.

The gesture, and the speeches which have followed, have been ringing endorsements of the Union and all that it stands for: tolerance, trans-national justice, open borders, free trade, increased opportunities, personal economic, cultural and political for all. In a word: internationalism. Since his election Macron has been speaking not only to and for a large sector of the French people; he has been speaking for and to both Europe and – as he made clear – the world. “Europe and the world”, he declared, “are waiting for us to defend the spirit of the Enlightenment”. His victory is the latest in series of defeats for the populist parties of the far right in Europe.

This is a reason to rejoice, but it is no cause for complacency. Brexit has not, as many hoped it might, been overturned, and Donald Trump has yet to be impeached. Marine Le Pen lost massively; but she still made substantial gains. Geert Wilders, the populist, with the dyed blond quiff, won fewer votes than expected in the Netherlands in March; but he is still better placed that he was before the elections. So too are a handful of other smaller parties with similar views. The “Alternative for Germany” has not been doing well in past few months, but neither has it disappeared. With Viktor Orbán firmly entrenched in Hungary, and elections due in Italy before next spring in which, according to recent polls, the “Five-Star Movement” could win over 32% of the vote placing it ahead of any of the major parties – Europe is still in urgent need of defense.

The EU is the outcome of a long, slow process which took its modern form in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries – the term “international” was coined by Jeremy Bentham in 1789 – of the possibility of an international rule of law, and of the trans-national agencies and courts to uphold it.

London Brexit, Pro-EU. CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

London Brexit, Pro-EU. CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The problem with international law, however, is that, by its very nature, it demands at a least a re-evaluation, if not an outright rejection, of what has been ever since the seventeenth century one of the foundations of the modern state: sovereignty. The power of the sovereign – be it a monarch or a popular assembly – wrote Thomas Hobbes is “to prescribe the Rules of discerning Good and Evil and therefore in him is the Legislative Power”. It was crucial, that that power should be what he called “incommunicable and inseparable”, by which he meant that it could not be divided nor shared with any other sovereign. This is the legal basis on which the modern nation state, constructed along what has come to be known as the “Westphalian model”, has been based. But while indivisibility operates well enough within individual states, it cannot, as another Englishman, the great jurist Henry Sumner Maine, wrote in 1888, “belong to International Law”. International law is based upon treaties, and the power to enforce those treaties can only ever be divided up among the nations which agree to abide by them. (The example Maine gave, paradoxically in the light of Brexit, was the British relationship with the Indian princely states.) Without divided sovereignty no international law can exist. It is one of the basic marks of western civilization.

European Union Law is an inter-national law, and it governs what all the member states share in common and, like all international law it assumes priority over any conflicting laws enacted by individual member states. The penal code, family and labor laws, the laws governing succession, inheritance and marriage, property and taxation – indeed all those laws which govern the daily life of the citizens of Europe – are all matters for domestic not EU law, so long as they conform to EU and international norms. Of course, dividing sovereignty inevitably means relinquishing some part of it, most contentiously, in the case of the EU, the right to close your borders against those with whom you are dividing it. But as the Greeks discovered at Salamis in 480 BCE, and Europeans have discovered time and time again over the centuries ever since, cooperation generally brings far more benefits that it does losses.

To be willing to divide sovereignty in this way, however, demands that you trust in and are prepared to work with those with whom you divide it, and this means sharing their same basic political, social, ethical and legal values. The European project, which Macron described as “our civilization” and “our common enterprises and our hopes” is nothing if not a grand exercise in sharing: sovereignty, administrative responsibilities, educational and cultural goals, citizenship and of course each other’s populations. And that, in turn, means trusting in what it can achieve. So far, for all its difficulties it has not let us down. The continent has been at peace now for over seventy years – the longest period in its entire history. For all the populist talk of “forgotten ones”, for all the justifiable fear of terrorism, its peoples live better, safer, more just and more equitable lives than they have ever done. Of course the EU is in need of reform. The power of the parliament, needs to be extended, and so, too, does the reach of the ECJ. European citizenship needs to be more clearly defined and strengthened. The Euro-zone requires a proper common budget – something already on Macron’s agenda. Military dependence on an unpredictable United States should be reduced and the long dormant plan for a European Defense Force revived. Above all perhaps the nature of the European project, its demands and its benefits, need to be better explained. A massive ignorance as to what Europe is has already robbed future generations of one European nation of a brighter future. Everything should now be done to prevent any of the others from going the same way.

The forces of populism and obscurantism may have been defeated; but they have not been annihilated. At the moment it would seem to be up to France to lead the way. En marche!

Featured image credit: “Emmanuel Macron at Sommet éco franco-chinois” by Pablo Tupin-Noriega. CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post En Marche: Macron’s France and the European Union appeared first on OUPblog.

June 4, 2017

Using novel gas observations to probe exocomet composition

Space missions like the Rosetta space probe built by the European Space Agency, that recently reached and studied the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, address the profound question of how life came to Earth by quantifying the composition of comets in the Solar System. Comets are made of the pristine material from which planets were formed. By exploring the composition of comets, we can thus access the pristine composition of the building blocks of planets. Such experiments can also tell us whether a planet is likely to be habitable as, for instance, water is thought to have been delivered to Earth by asteroids/comets. Using comets as probes of the primordial Solar System leads to the exciting prospect of addressing the even broader question “can the physical characteristics, including possible habitability, of exoplanets be determined by measuring the composition of the comets in exoplanetary systems, i.e. exocomets?”

Recently, we gave predictions of the amount of gas (created from these exocomets) surrounding nearby planetary systems for which we can detect exoplanets. Using ALMA, a new facility able to detect tens of new systems with exocometary gas, we started comparing our predictions to actual observations to deduce the composition of exocomets in these extrasolar systems. From this, we eventually obtained significant constraints on the composition of exocomets, and thus on the material from which exoplanets were formed, in a large number of planetary systems.

The complexity of our method arises in actually detecting exocomets; imaging individual comets is difficult even in our own Solar System because these objects are cold and dark, but one solution is to observe signals from large systems of comets. In the Solar System, comets are constantly colliding within the Kuiper belt (a ring of comets just beyond Neptune), producing large amounts of dust and gas from the pulverised rock and ice. The same process occurs in other stars that are similar to the Sun, and the dusty remnants of these collisions have been observed for more than 30 years now. However, the gas component – which is critical for determining the amount of ice in comets – has remained too faint to be observed.

An extra-solar system composed of five planets and a belt composed of exocomets (similar to the Kuiper belt in our Solar System). Graphic by Amanda Smith, Institute of Astronomy. Used with permission.

An extra-solar system composed of five planets and a belt composed of exocomets (similar to the Kuiper belt in our Solar System). Graphic by Amanda Smith, Institute of Astronomy. Used with permission.This problem has been resolved recently with the ALMA interferometer, located in the Atacama Desert in Chile, which can now detect the gas in these extrasolar Kuiper belts. We recently showed the feasibility of extracting the composition of exocomets by observing extrasolar Kuiper belts (via emission lines of key species such as CO, oxygen, or carbon), and we now propose to extend this experiment to a plethora of systems to determine their cometary rock-to-ice ratios and compare with our own Solar System.

To do so, we predict the amount of gas around each planetary system that hosts its own version of a Kuiper belt. CO gas is released from the exocomets at the belt location. Due to strong impinging UV photons, CO is destroyed into carbon and oxygen atoms that then spread all the way to the star. The CO and atomic gas discs can be observed with ALMA, and with our model, we can quantify the gas production rate of these belts and then compare to what is observed. Doing this comparison allows us to fit the composition of comets in each system. Thanks to the ALMA facility, we hope that the number of gas detections will greatly increase in the next few years. Our work is the first step towards understanding the composition of exocomets for a large number of different planetary systems. And this will generate the first significant constraints on the building blocks of exoplanetary systems and will provide a census of the diversity of compositions beyond our own Solar System.

Featured image credit: Comet falling into white dwarf (artist’s impression) by NASA, ESA, and Z. Levy (STScI). CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Using novel gas observations to probe exocomet composition appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers