Oxford University Press's Blog, page 354

June 20, 2017

New bank resolution regime as an engine of EU integration

On 1 June 2017 the European Commission and Italy reached an agreement ‘in principle’ on the recapitalization of Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena (MPS). A mere week later, the Single Resolution Board (SRB) put Banco Popular Español (BPE) into resolution, and had its shares transferred to Banco Santander. Both cases must be understood in the context of the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) and both can be considered as examples of how the new European bank resolution regime performs as an engine of European integration.

1. Bank resolution as part of the Banking Union

First, the Banking Union as originally intended included, besides a new bank insolvency regime, also a common European deposit guarantee scheme (DSG) and a Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM). The founders of the Banking Union believed that banking supervision would only be credible if it could allow banks to become insolvent. This would entail that the burden of bank insolvencies should be shared amongst Member States, because individual Member States might not wish or be able to carry the burden of a major bank insolvency in their jurisdictions. However, for political reasons, a common European deposit guarantee scheme has until now apparently been a step too far. Yet, in November 2015, a new initiative has been introduced that should bring about a ‘European Deposit Insurance Scheme’ (EDIS). Emmanuel Macron, who was elected president of France only a couple of weeks ago, seems to endorse it. Such an EDIS would mean an important step in the direction of further European (or at least: Eurozone) integration, not only economically, but also politically and morally.

2. Cross-border bank resolutions in court

Second, the new pan-European bank resolution regime has been ‘consolidated’ by two relatively recent court decisions, although these cases paint a nuanced picture. In both court decisions, the central question was whether certain decisions by (national) government authorities would qualify as ‘resolution measures’. If they would, they would have to be recognized in all other Member States of the EU as per the BRRD. In both decisions, such recognition was challenged by creditors in another Member State, who would suffer damages as a consequence of an insolvency measure taken by a government body in the Member State where the failing bank was located. In the judgment of the Regional Court Munich I of 8 May 2015, the court held that a certain form of cancellation of debt by the Austrian resolution authority of Austrian bank Hypo Alpe Adria was not to qualify as a resolution measure. Consequently, there needed not be any recognition in Germany, and hence the creditor, Bayern LB, was not to suffer damages as a consequence.

In the Banco Espírito Santo (BES) case, on the other hand, it was contested before an English court whether the Portuguese Central Bank had transferred a facility agreement that had been concluded between Goldman Sachs International and BES to Novo Banco (NB). The Central Bank had incorporated NB to function as a bridge institution in the context of BES’s resolution, and BES was to be liquidated. Goldman Sachs contended that the facility agreement was effectively transferred, and the Central Bank said it was not. In its judgment of 4 November 2016, the Appeal Court held, in short, that whether the facility agreement was effectively transferred was first and foremost a matter of Portuguese law, and that resolution measures such as these should be recognized under the CIWUD. It also found support in the Kotnik case, in which the CJEU decided on 19 July 2016 that resolution measures that were taken by the Slovenia government pre-BRRD should nonetheless be recognized.

These two cases indicated at the least that measures taken by a resolution authority in the context of bank insolvency are not always recognized throughout the EU. But if they are recognized (and this seems increasingly to be the case), that has an integrational effect: it means measures taken in a Member State under that Member State’s law have effect in other Member States.

3. Harmonization of national insolvency laws

Third, the new bank resolution regime has also led to harmonization of national insolvency laws. On the one hand, for many EU jurisdictions, the new bank resolution regime has meant a major shift in that crisis management for banks has been taken away from the bankruptcy courts (and ‘normal’, ie general, corporate insolvency law), and been put in the hands of government authorities, viz. resolution authorities.

On the other hand, national insolvency laws continue to play an important role in the new regime. Not only does the new regime rely, in several instances, on normal insolvency law (for instance because parts of a bank in resolution must be liquidated under normal insolvency law), but also as regards creditors and shareholders, the leading principle is that they must not be worse off than they would have been if the bank had been subjected to national insolvency laws. In order to retain a level playing field in the EU, this No-Creditor-Worse-Off (NCWO) rule has required the European legislator to harmonize, besides bank resolution law, also national insolvency laws.

There are various reasons to believe that the new bank resolution regime will give further impetus to European integration. But, as many commentators have rightly noted, only a real-life case will show whether the new resolution regime actually works.

Moreover, under a recent Commission draft Directive of 23 November 2016, Article 108 BRRD is to be amended. Pursuant to this draft Directive, Member States must amend their insolvency laws so that a new category of ordinary unsecured claims is inserted into the national priority order. These claims follow from a specific type of debt instruments, and are to have a lower priority ranking than that of ordinary unsecured, non-preferred claims , but higher than statutory or contractually subordinated claims. The proposal is currently being debated in the European Parliament. But it signifies a trend, viz. the trend that the common bank resolution regime will require more harmonization and even unification as regards the national priority order under general insolvency law.

4. Resolution regimes for non-banks

A fourth development concerns the initiatives of national as well as of European legislators to introduce resolution regimes, à la BRRD/SRMR, for financial institutions other than banks. Several weeks ago, for instance, the Dutch Council of State has advised on a draft bill that would create a resolution regime for insurers that is similar to the current bank resolution regime as established by the BRRD and SRMR.

Similarly, on 28 November 2016, the Commission published a draft resolution regime for Central Counter Parties (CCPs). Partly as a consequence of the 2012 European Market Infrastructure Regulation (EMIR), a ‘large proportion of the EUR 500 trillion of derivatives contracts that are outstanding globally are cleared by 17 CCPs across Europe’ (dixit the Commission). Thus, enormous risks have been centralised at CCPs, so that an appropriate resolution regime for these institutions seemed warranted.

5. Resolution in practice

The above has shown that there are various reasons to believe that the new bank resolution regime will give further impetus to European integration. But, as many commentators have rightly noted, only a real-life case will show whether the new resolution regime actually works. More specifically, only then will it become clear whether the new regime will prevent governments from choosing the way of the least resistance by bailing-out failing banks. Thus, the costs of those bank failures would continue to be borne by all tax payers together, rather than by a specific group of investors. The recent cases of MPS and BPE are cases in point.

In December, the ECB required MPS to recapitalize EUR 8.8b and denied an extension of the period to raise extra capital. The Commission has also been involved, for any ‘precautionary measure’ must be approved under the State-aid rules by the Commission. On 1 June 2017, the Commission and Italy announced that an agreement was reached under which subordinated bonds will be wiped-out, although retail investors may be compensated on the grounds of miss-selling. MPS represents an instance where the workings of the SSM and the new resolution regime have been put to the test. It proves the reluctance of governments to trigger resolution, but it also has required the relevant EU authorities to investigate, together with the Member State concerned, the limits of the new regime. This was all the more true for BPE, where the SRB did take a resolution measure which had to be implemented by the national resolution authority. Quite different from the solution chosen for MPS, as of 7 June 2017, all shareholders of BPE have been wiped out. Moreover, subordinated debt were converted into shares and subsequently transferred to Banco Santander for the price of 1 EUR, which effectively meant a wipe-out and expropriation of both shareholders and subordinated debtholders.

Whilst it remains to be seen how the current plight of Banca Popolare di Vicenza and Veneto Banca will be handled, I think it is fair to conclude that the new EU bank resolution regime proves to be an engine of integration with respect to the institutions tasked with resolving bank insolvencies, but also regarding national insolvency laws, and also for financial institutions other than banks.

This post was originally posted on the Oxford Business Law Blog on 14 June 2017. This is a cross-post of the original article.

Featured image credit: ‘Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena, Siena, Italy’, by DV. CC BY-SA via Wikimedia Commons

The post New bank resolution regime as an engine of EU integration appeared first on OUPblog.

June 19, 2017

Shining evolutionary light: Q&A with EMPH EIC Charles Nunn

Evolutionary biology is a basic science that reaches across many disciplines and as such, may provide numerous applications in the fields of medicine and public health. To further the evolutionary medicine landscape, we’re thrilled to welcome Dr. Charles Nunn of Duke University as the new Editor-in-Chief of Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health, the open access journal that aims to connect evolutionary biology with the health sciences to produce insights that may reduce suffering and save lives. Dr. Nunn sat down with us recently to discuss his vision for EMPH’s future and his work in evolutionary medicine, including studies on the evolution of sleep and research in rural Madagascar.

How and when did you get involved with Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health ?

I became involved in EMPH at its founding by serving on the Editorial Board, at the invitation of the first editor, Stephen Stearns. In addition, I think that I hold the honor of having the first research paper published in EMPH, or at least the first to be assigned a DOI. This was my research article with Natalie Cooper, “Identifying future zoonotic disease threats: Where are the gaps in our understanding of primate infectious diseases?” Since that time, I have become steadily more involved with the journal, and have published five articles of four different article types in EMPH.

What led you to the field of evolutionary medicine?

Immediately after my Ph.D. research, I began studying the ecology and evolution of infectious disease in a postdoc position with Drs. Janis Antonovics and John Gittleman. From the world of infectious disease, it was a natural progression to become more aware of evolutionary medicine, and I was heavily influenced by books such as Nesse and Williams’ Why we get sick. However, my real breakthrough into evolutionary medicine came when, as an associate professor at Harvard, I taught a course on Evolutionary Medicine with Prof. Peter Ellison. Co-teaching with Peter opened my eyes to many nuances of the field of evolutionary medicine. Importantly, we taught the course as a part of the General Education curriculum at Harvard. Our goal was to provide any student – from any major – a course that would introduce them to a new way of thinking about the evolutionary origins of health and disease: how and why has evolution made us susceptible to disease? I continue to believe that this is basic knowledge that all students should know, as we will all inevitably deal with many kinds of disease in our lives and those of our loved ones. I have moved to Duke University, but I continue to teach an entry-level course on evolutionary medicine, with no prerequisites.

Describe what you think the journal will look like in 20 years and the type of articles it will publish.

I hope that we will continue to build a community of scholars interested in clinical and basic research at the intersection of evolution, ecology, and health, including the health of non-human animals. I do think we are still at the beginning of a large and impactful research enterprise, with many exciting findings ahead, and ideally the application of those findings to both understand human health and to improve it. While it is interesting to publish commentaries that lay out new hypotheses and predictions, we need more research to test those predictions and, eventually, review articles and meta-analyses that synthesize the findings; hopefully the next 20 years will bring us closer to those systematic reviews and the stronger foundations they provide for policy and medical application. Of course, to move toward having real application, we need more engagement with researchers in medicine, public health, dentistry, nursing, and even veterinary medicine. I hope we will see more researchers from those fields publishing in EMPH in the next 20 years. We are working on it!

What is the most important issue in the field right now?

There are so many areas that are “hot” and important that it is hard to know where to start. Let’s start by considering what “important” means. If we judge importance by the impact on human lives, then research on the evolution of antimicrobial resistance should rank highly. This is a challenge that keeps me up at night, and with good reason, given the rapid evolution of resistance and the shortage of viable solutions. Similarly, cancer is an evolutionary process in the body; evolutionary approaches are crucial to understanding this process, and to coming up with solutions to treat cancer (including again, the evolution of resistance). Finally, I’d put in an argument for global health research. The lives of people around the world are changing radically. We need to better understand how those changes are affecting health, including unintended consequences. We need to consider, for example, whether and how similar changes in developed countries led to the growing epidemic of autoimmune diseases.

How would you describe EMPH in three words?

Innovative, international, and rigorous.

Photo of Dr. Charles Nunn, used with permission.

Photo of Dr. Charles Nunn, used with permission.Tell us about your work outside the journal.

I research a wide range of topics, including the ecology and evolution of infectious disease, the evolution of sleep, and the application of phylogenetic methods to a wide range of questions in biology. Much of this research takes place in rural Madagascar, where I run a project that links global health, conservation biology, and evolutionary anthropology. We loosely call this project, “Shining evolutionary light on global health challenges,” and we investigate questions that include dental health, the skin microbiome, human sleep, and the emergence of infectious disease in the context of anthropogenic habitat change. We also conduct research on household air pollution in Madagascar, driven by cooking indoors with wood, and its influence on both deforestation and human health. In all of these projects, we consider human behavioral ecology, and also the societal factors that are leading to behavioral changes in these communities that impact health both positively and negatively.

How do you think this journal influences research today in your field of study?

Evolutionary anthropologists are actively engaging with evolutionary medicine. Many members of our editorial board come from evolutionary anthropology, and we have a solid collection of articles from this field – although far from exclusively, and we are working hard to maintain a breadth of areas in the EMPH portfolio. This interdisciplinarity is also characteristic of evolutionary anthropology. As such, I think the journal is having a strong impact on my field, and hope it will continue to do so, while also reaching out to many other fields.

Featured image credit: The order of caos by Joel Filipe. CC0 Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Shining evolutionary light: Q&A with EMPH EIC Charles Nunn appeared first on OUPblog.

How much do you know about refugees?

The United Nations’ (UN) World Refugee Day is observed on 20 June each year. This event celebrates the courage, strength, and determination of women, men, and children who are forced to flee their homeland under threat of persecution, conflict, and violence. The United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), the UN, and countless civic groups around the world host World Refugee Day events in order to draw the public’s attention to the millions of refugees and internally displaced persons.

In honour of the UN World Refugee Day, we have compiled the following quiz about the extraordinary achievements of well-known people who have all had to flee their homelands. From artists to sportspeople, writers, and scientists of world renown, take our quiz to raise awareness and celebrate their talent and courage at a time when this has never been more important.

Thank you very much for taking our World Refugee Day Quiz. We hope you have enjoyed answering our selected questions about the extraordinary achievements of well-known refugees.

Featured image credit: “Refugee Camp, Beirut” by George Grantham Bain Collection. CCO Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post How much do you know about refugees? appeared first on OUPblog.

June 18, 2017

Climate change: are you an expert? [Quiz]

Climate change is one of the most significant and far-reaching problems of the twenty-first century and it is a frequent topic of discussion everywhere from scientific journals to the Senate floor. Because climate change is often the subject of heated debate, it’s easy to mistake political stands for scientific facts.

Inspired by The Death of Expertise, in which Tom Nichols explores the dangers of the public rejection of expertise, we’ve created a series of quizzes to test your knowledge. Take this quiz to see how much you know about climate change. Then watch the video below to see how OUP employees fared against climate change expert Joseph Romm.

Featured image credit: “life-beauty-scene-arctic-iceberg” by Unsplash. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Climate change: are you an expert? [Quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

How can we measure political leadership?

Understanding and measuring political leadership is a complex business. Though we all have ideals of what makes a ‘good’ leader, they are often complex, contradictory, and more than a little partisan. Is it about their skills, their morality or just ‘getting things done’? And how can we know if they succeed or fail (and why?). From Machiavelli onwards we have wrestled with our idea of what a perfect leader should look like and what makes them succeed or fail.

Taking the idea of ‘political capital’ we can evaluate what sort of authority a leader is granted and how they choose to ‘spend’ their capital. We can think of political capital as a stock of ‘credit’ accumulated by and gifted to politicians, in this case, leaders. Political capital is often used as a shorthand to describe if leaders are ‘up’ or ‘down’, how popular they are, and how much ‘credit’ they have in the political sphere. As with financial capital, commentators and politicians speak of it being ‘gained’ or, much more commonly, ‘lost.’ Most importantly, it’s viewed as something finite;– you only have so much and it quickly depreciates under pressure. This presents us with alternative method of understanding why political leaders succeed or fail.

Politicians are acutely aware of their finite stock of authority. Having plenty of this ‘credit’ means a leader can utilise it to achieve policies through spending or leveraging – think Tony Blair in 1997 or Barack Obama in 2009, when their support, popularity, and momentum temporarily made them politically unassailable. They believe they can pass laws, set agendas, and dominate the ‘narrative.’ Tony Blair, reflecting in his autobiography, spoke of how he was a capital ‘hoarder’, trying not to spend his authority in his early years as Prime Minister: “At first, in those early months and perhaps in much of that initial term of office, I had political capital that I tended to hoard. I was risking it but within strict limits and looking to recoup it as swiftly as possible… in domestic terms, I tried to reform with the grain of opinion not against it.”

Understanding leadership capital

Academics have defined political capital in a variety of ways. It can be about trust, networks, and ‘moral’ or ethical reputation. By incorporating many of these ideas, we have developed a notion of leadership capital as a measure of the extent to which political office-holders can effectively attain and wield authority.

We define leadership capital as an aggregate of three leadership components: skills, relations, and reputation. We have worked this is into a Leadership Capital Index (LCI) with 10 simple variables to enable leaders to be scored, to capture both quantitative data and qualitative assessments.

The measure of a leader’s skills refers to the required leadership abilities, from the communicative to the managerial and cognitive. We include the power of a leader’s vision, their communication, and popularity. The difficulty for many leaders is that they have, of course, some of these but not all –both Cameron and Blair for example were accused of having the communication skills and (relative) popularity, but not the vision. Theresa May has looked like she has neither of the skill set.

David Cameron and Barack Obama at G8 summit, 2013 by White House. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

David Cameron and Barack Obama at G8 summit, 2013 by White House. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Leadership is also a relational activity. Leaders mobilise support through loyalty from their colleagues, their party, and the public. Part of the challenge is to retain these ties for as long as possible or, at least, as one scholar put it, to disappoint followers at a rate they can accept. But how they do this can depend on their leadership style. The most obvious and talked about way is through personal charisma; Blair and Obama offered what JM Burns famously termed ‘transformational’ leadership. But effective leadership can also be exercised with quiet, technocratic competence and delivery, more in the style of Angela Merkel, suiting the cultural norms of the country and the context.

Third, leadership is continually judged by reputation. Leaders create their own performance measurements – have they done what they promised? Each type of leadership claim sets up its own performance test. We look at whether a leader is trusted by the public, subject to challenge or not, and to what extent they saw through party policy or their legislative agenda.

Looking across these three areas allows us to understand how they influence each other in ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ cycles. Successful leaders communicate, achieve aims, and strengthen relations and reputation. Failing leaders poorly communicate or never map out a vision, then often lose confidence, control, and credit.

David Cameron’s EU strategy 2013-2016 provides a neat mini-example of capital loss, where he gambled his capital on a series of high stakes policies with diminishing returns. His failure to communicate his European vision, and tendency for a series of ‘Hail Mary Passes’ with a promised 2017 referendum and EU reform, eroded already ambivalent relations with parts of the Conservative party. This left him with less control over EU policy as party rebels exerted more and more influence. So attempts to regain the high ground weakened his capital. This lead directly to Cameron losing the referendum and resigning in June 2016.

Where next for leadership?

Leadership capital offers one way of understanding how leaders succeed and fail. The LCI can measure and identify the ebb and flow of the leadership trajectory over time. It can be used to compare leaders and leadership within and between countries. Comparison across different systems is however a challenge within often contrasting structural frameworks.

There is also the fascinating issue of comeback. If all leaders only have a limited ‘stock’ what of those who bounce back? Bill Clinton, Tony Blair (to an extent), or John Howard in Australia all managed to turn around their political fortunes and reinvigorate their leadership. Winston Churchill may be the prime example of leader who squandered skills, reputation, and relations over and over until late in his life-his career up until 1939 was famously described as a study in failure. Perhaps leadership capital can help us to understand why and how this happens.

A version of this article orginally appeared on Democratic Audit UK.

Featured image credit: Chess Board by PublicDomainPictures. Public Domain via Pixabay

The post How can we measure political leadership? appeared first on OUPblog.

The representation of fathers in children’s fiction

There aren’t many areas in literature where men are under-represented, but it’s safe to say that in children’s fiction, men – and fathers in particular – have been largely overlooked.

And deliberately so. Adult carers with a sense of responsibility have been ousted from the action because of their exasperating tendency to step in and take control. Children’s authors don’t want competent adults interfering and solving problems all over the place. Heavens! When it comes to annoying plot-stoppers they can prove even trickier than mobile phones.

No. Fathers were much better mown down early on by rhinos (James and the Giant Peach), staying in London and evacuating their children to the sketchy care of absent-minded professors (The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe), or dying in India, leaving their only daughter destitute at an expensive boarding school run by the most heartless of headmistresses (A Little Princess).

Even where the father was of more focus it was preferable to keep him at a safe distance, languishing in prison, say, his offspring banished to the countryside and tasked with clearing his name. Only at the very end of The Railway Children does Bobbie get her “Daddy! My daddy!” moment, when through their own magnificent efforts, the children have caused the smoke and steam to clear and it’s safe to reveal their exonerated father.

But recently we’ve seen a surge in stories where fathers are much more central to the action. I think one reason for this is the change in approaches to parenting. There’s much less of a ‘them and us’ feel in the way we parent now. In fact, there’s a tendency for parents to cast themselves as their children’s friends rather than simply as authority figures – however loving – from the distant race of Adults. This lessening of formality, perhaps particularly where fathers are concerned, encourages children to see their parents as complete people with their individual character traits more on show, both qualities and failings. And they’re more likely to allow them that bit further into their own worlds.

Trends in writing style have also allowed dads to be drawn more to the centre stage. Where the narrator was once omniscient and had an almost tangible presence, the telling of more and more stories has been handed over fully to their child protagonists. Narratives are often in the first person and even when they’re not, events are recounted in ‘up close’ third person, whereby the reader sees everything from the main character’s point of view, and rarely, if ever, seeing further than the hero sees themselves.

Recently we’ve seen a surge in stories where fathers are much more central to the action. I think one reason for this is the change in approaches to parenting.

With this child’s microscopic eye turned onto fathers we have a chance to explore their characters in depth; there are new opportunities to create genuine, realistic relationships between father and child. And the joy of realistic characters who, like real people, make mistakes and can’t solve problems immediately – thus putting the dampers on vital jeopardy – is that they can be allowed to stay central to the story. This is so from picture books like The Dressing-Up Dad where Danny’s playful dad unwittingly takes his enthusiasm for dressing-up games a little too far – and all the way up through early readers, middle grade, teenage and young adult fiction.

And there are some fabulous dads to discover.

Timothy Knapman and Joe Berger’s colourful Superhero Dad wears his pants outside his trousers in time-honoured superhero fashion, but that’s where the similarity with such fantasy characters ends. The feats he carries out are described in bold rhyme and splashy primary colours, but they are all reassuringly everyday. Superhero Dad is truly super rather than truly heroic.

Bob Graham’s picture book dads, like those in Jethro Byrde, Fairy Child, are delightfully woolly and fallible, whether they are human, homely ones struggling with deck chairs, or slightly scruffy fairy ones, crash-landing their tiny battered ice cream vans. These are picture book celebrations of today’s modern, hands-on dads.

From Sarah Ogilvie’s vibrant cover illustration for The Demolition Dad we might expect a two dimensional character in the amateur wrestler, big bellied, wrecking ball-swinging George Biggs, but George’s appearance belies his nature. This is what Jake has to learn about his gentle, sometimes anxious dad, and Phil Earle’s middle grade tale is beautifully balanced between the loyal, sensitive, and ultimately very brave father and the extravagant ideas his adoring son has about him.

David Almond (My Dad’s a Bird Man), Simon Mason (Moon Pie), and Horatio Clare (Aubrey and the Terrible Yoot) have been able to delve further with stories which, while still child-led, manage to explore the impact of, respectively, a father’s grief, alcoholism, and depression. Almost anything can be examined in children’s fiction, provided it is told from the point of view of a child. Adults can step into the spotlight at any time, but in modern storytelling it is the child who is in charge of directing the light.

It’s good to see so many real dads: Not just stay-at-home dads, but also estranged dads like Anne Fine’s Daniel alias Madam Doubtfire, and adoptive dads like Osh in Lauren Wolk’s Beyond the Bright Sea. We’re seeing step-dads too: good, reliable ones such as Uncle Derek in Fleur Hitchcock’s Dear Scarlett, terrible, terrifying ones like Dean in Joanna Nadin’s Joe All Alone and would-be new ones, like Rob in Anna Wilson’s The Family Fiasco – men-next-door types doing their best and bumbling along like the rest of us.

So turn around Dad. Step out of the steam and show us who you really are, flaws and foibles, warts and wishes, dreams and all.

Oh yes, and it’s Father’s Day, so do enjoy your day in the spotlight.

Featured image credit: reading school education by laterjay. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The representation of fathers in children’s fiction appeared first on OUPblog.

June 17, 2017

Why do I wake up every morning feeling so tired?

The alarm rings, you awaken, and you are still drowsy: why? Being sleepy in the morning does not make any sense; after all, you have just been asleep for the past eight hours. Shouldn’t you wake up refreshed, aroused, and attentive? No, and there are a series of ways to explain why.

The neurobiological answer:

During the previous few hours before waking in the morning, you have spent most of your time in REM sleep, dreaming. Your brain was very active during dreaming and quickly consumed large quantities of the energy molecule ATP. The “A” in ATP stands for adenosine. The production and release of adenosine in your brain is linked to metabolic activity while you are sleeping. There is a direct correlation between increasing levels of adenosine in your brain and increasing levels of drowsiness. Why? Adenosine is a neurotransmitter that inhibits, i.e. turns off, the activity of neurons responsible for making you aroused and attentive. You wake up drowsy because of the adenosine debris that collected within your brain while you were dreaming.

Who did you sleep with last night?

Couples sleeping in pairs were investigated for sleep quality, that is, for the correct balance of non-REM and REM, as well as their own subjective view of how they slept. For women, sharing a bed with a man had a negative effect on sleep quality. However, having sex prior to sleeping mitigated the women’s negative subjective report, without changing the objective results, that is, her balance of non-REM and REM was still abnormal. In contrast, the sleep efficiency of the men was not reduced by the presence of a female partner, regardless of whether they had sexual contact. In contrast to the women, the men’s subjective assessments of sleep quality were lower when sleeping alone. Thus, men benefit by sleeping with women; women do not benefit from sleeping with men, unless sexual contact precedes sleep—and then their sleep still suffers for doing so.

An illustration to showcase the brainactivity during REM-sleep by Lorenza Walker. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

An illustration to showcase the brainactivity during REM-sleep by Lorenza Walker. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Did you go to bed late last night?

People who prefer to stay out late (evening types), get up at a later time, and perform best, both mentally and physically, in the late afternoon or evening. Evening-type individuals were significantly more likely to suffer from poor sleep quality, daytime dysfunction, and sleep-related anxiety as compared with morning-type individuals. Even more disconcerting is that late bedtime is associated with decreased hippocampal volume in young healthy subjects. Shrinkage of the hippocampus has been associated with impaired learning and memory abilities.

Did you go to bed hungry last night?

What you eat before bedtime also might improve your chances of getting a good night’s sleep. A recent study suggests that eating something sweet might help induce drowsiness. Elevated blood sugar levels have been shown to increase the activity of neurons that promote sleep. These neurons live in a region of the brain that lacks a blood–brain barrier; thus, when they sense the presence of sugar in the blood they make you feel drowsy. This might explain why we feel like taking a nap after eating a large meal. This is just one more bit of evidence demonstrating your brain’s significant requirement for sugar in order to maintain normal function.

Getting a good night’s sleep is not always easy for most people. With aging, normal sleep rhythms become increasingly disrupted leading to daytime sleepiness.

What if you do not get enough sleep?

Although scientists have not discovered why we sleep, they have discovered that we need between six and eight hours every night. Not getting enough sleep makes us more likely to pick fights and focus on negative memories and feelings. The emotional volatility is possibly due to the impaired ability of the frontal lobes to maintain control over our emotional limbic system. We also become less able to follow conversations and more likely to lose focus during those conversations. Sleep deprivation impairs memory storage and also makes it more likely that we will “remember” events that did not actually occur. Extreme sleep deprivation also may lead to impaired decision-making and possibly to visual hallucinations. Not getting enough sleep on a consistent basis places you at risk of developing autoimmune disorders, cancer, metabolic syndrome, and depression. Why? Some recent studies have reported that sleep is important for purging the brain of abnormal, and possibly toxic, proteins that can accumulate and increase the probability of developing dementia in old age. Whatever you are doing right now, stop and go take a nap. Preferably alone.

Featured image credit: “Alarm Clock” by Congerdesign. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Why do I wake up every morning feeling so tired? appeared first on OUPblog.

June 16, 2017

Understanding the Democratic Unionist Party

Theresa May’s desperate search for an ally after a calamitous 2017 General Election saw the Democratic Unionist Party come under scrutiny like never before. The DUP is a party which has moved from its fundamentalist Protestant Paisleyite past – but not at a pace always noticeable to outsiders.

The DUP is comfortable in its own skin. When it allowed myself and four other academics to conduct a survey of the views of its members, we expected the party leadership to ask for some findings to be suppressed. Not at all – go ahead and publish your book we were told. We were talking about power in Belfast though. We did not imagine its extension to Westminster.

So, who are the DUP’s members and what do they think?

One-third of the DUP are drawn from the tiny Free Presbyterian Church, founded by Ian Paisley. The Church accounts for only 1% of Northern Ireland’s population. The DUP was created as a form of politicised Protestantism to espouse the ideas of that Church, opposing ecumenism and Romanism. Catholic membership amounts to 0.6%. In terms of actual numbers, let’s just say I’ve got more fingers on the hand that is typing this piece. The religious and social conservatism of DUP members is apparent. Most DUP members go to church weekly and describe themselves as very religious. 54% of the DUP say they would ‘mind a lot’ if a close relative married someone from a different religion. A majority believe homosexuality to be wrong, let alone support same-sex marriage. The DUP have vetoed the legalisation of same-sex marriage 5 times in Northern Ireland Assembly votes. A majority of DUP members also oppose the legalisation of abortion, prohibited in Northern Ireland unless the mother’s life is at risk.

It will come down to what money the Conservatives can offer Northern Ireland. And the Conservatives will have to offer plenty.

However, contrary to some of the wilder reports in the immediate post-election aftermath, the DUP wishes to confine its religious and moral conservatism to Northern Ireland. Moreover, the DUP’s primary demands in return for supporting an ailing Conservative government were designed to help the Northern Ireland economy, still short of private sector investment. The old DUP put Protestantism first. The new, modern DUP puts pounds first. The old Protestant party of protest still occasionally shows its hand, but the ‘new DUP’ of greater pragmatism is more commonly seen.

Historically, the DUP liked to say no – until it became top dog in Northern Ireland and did a jaw-dropping deal to share power with Sinn Fein in 2007. They opposed the Good Friday/Belfast Agreement in 1998 – and most members still say they would oppose it if a referendum was held today. For many DUP members, the peace and political processes have meant political and cultural retreat. 61% feel that policing reforms have ‘gone too far’. Most DUP members believe that there is considerable prejudice against Protestants in Northern Ireland.

The same percentage believes that the Orange Order – a controversial organisation which prohibits its members from marrying Catholics or participating in Catholic religious services – should have unfettered marching rights in Northern Ireland, rather than have parades re-routed away from nationalist areas. It remains DUP policy to get rid of the Parades Commission, the regulatory body on such issues. That comes as little surprise when one considers that half of DUP elected representatives are members of the Orange Order.

How much Theresa May knew or cared about the views of her new friends is unknown. Westminster arithmetic was all that mattered. The DUP’s monopoly status as the friend of the Conservative Party (DUP members prefer the Tories to Labour by 7 to 1 ) meant the DUP could demand a high price. It will come down to what money the Conservatives can offer Northern Ireland. And the Conservatives will have to offer plenty.

Featured image credit: Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) office, Castle Street, Lisburn, County Antrim, Northern Ireland, November 2010 by Ardfern. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Understanding the Democratic Unionist Party appeared first on OUPblog.

Bipolar disorder and addictions

Bipolar disorder is characterized by significant fluctuations in a person’s mood, which may occur for no apparent reason. It tends to persist and people affected by it have phases when they are very happy and active, and phases when they are feeling very sad and hopeless, with often normal moods in between. Some people with bipolar disorder like the “high” phase so much that they may take no action until their mood is so elevated that they are hypomanic or even manic. In the “down” phase the person feels pervasively sad and may slump into a severe depression and feel life is closing in around them. Bipolar disorder typically starts in a person’s late teen or early adult years.

Bipolar disorder consists of two major types. Bipolar disorder, type I is the classical and well-known disorder, which used to be called manic-depressive illness. Episodes of hypomania and depression tend to alternate, with each phase lasting for days or weeks. Bipolar disorder, type II, is characterized by shorter-lived episodes of abnormal mood (it is sometimes termed “rapid cycling”) and there is a predominance of depressive phases. Bipolar disorder, type I occurs in approximately 1% of the adult population. Bipolar disorder, type II is more common and estimates vary from 2-3% to up to 6% of the general population. Some people use the term bipolar disorder, type III to indicate a disorder where hypomanic episodes are precipitated by antidepressant medications. A form of bipolar disorder can also be induced by substance use. Sometimes it can be difficult to distinguish between bipolar disorder and certain forms of post-traumatic stress disorder and some authorities argue that there can be an overlap between these disorders.

Responding to bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder is a significant illness and it is vital that it is identified early and treated effectively. Self-management is a key aspect of mastering the disorder and people with the disorder can manage and modify its phases much more effectively if they are actively involved in monitoring their mood (preferably with the help of family or close friends) and taking steps to contact their psychiatrist, general practitioner, or health professional if they (or their family/friends) sense a deviation in how they are feeling or acting from their usual self.

Many people have experienced bipolar disorder, and although it is a challenge to manage it over several years, there is effective treatment, which typically combines medication and psychological therapy. Well known historical figures, such as Winston Churchill, are thought to have had bipolar disorder and there are many others who have made major contributions to life, in particular to the creative arts, while managing their bipolar disorder.

Bipolar’s links with alcohol and drug use

Gambling by meineresterampe. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Gambling by meineresterampe. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.Bipolar disorder is also strongly associated with alcohol and drug and other addictive disorders, such as gambling. The relationship can be a two-way one. Substance disorders can induce bipolar-type disorders, with phases of hypomania and depression resembling the classical condition. Some substances, because of their pharmacological effects, will induce mood changes with alternating elevations and declines in mood. The use of psychostimulants such as methamphetamine and cocaine characteristically produces successive episodes of alternating moods.

More commonly, the phases of bipolar disorder can lead to episodes of substantial substance use which may persist until the mood normalises, or may lead to such a repetitive pattern of use that dependence (addiction) is induced. The most frequent time for substance use to “take off” is when the person has a hypomanic (or manic) episode. As part of the over activity and bright over-euphoric mood, the person may indulge in alcohol and drug use to a far greater extent than they would normally do. The person can also lose judgement and do things they later regret. A person in the hypomanic phase can overspend, which may involve illicit substances or gambling excessively. Substance use tends to continue unchecked until the hypomanic phase is treated. Serious disturbance to the person’s health and well being, finances, and personal relationships can ensue. Sometimes these phases are accompanied by excessive gambling and sexual activity, or sometimes bursts of gambling can occur without substance use or the other features.

Somewhat less commonly, substance use may become problematic in the depressed phase of the bipolar illness. Here the motive tends to be “medicinal”: people try to boost their mood or numb their emotions. Various substances may be used in this phase. Depression may be temporarily relieved by a psychostimulant – however, the “down” phase when stimulant use is terminated is usually more severe in the presence of a bipolar disorder. Sometimes people drink alcohol excessively, take sedative drugs such as benzodiazepines or smoke cannabis in an effort to numb themselves and to avoid the worst of the depressive experience. Such so-called benefits are only temporary and the bipolar illness tends to be worsened when such substances are used in this way.

Treatment

Early diagnosis and effective treatment are key to the management of bipolar disorder. A history of trauma should be elicited to see if this is a contributory factor or whether the illness conforms more to a complex form of post-traumatic stress disorder. Mood stabilizers, such as lithium, valproate, and some anti-psychotic drugs are central to treatment. Caution needs to be taken if antidepressants are being considered because they can precipitate hypomania or mania (bipolar disorder, type III).

The treatment for accompanying substance use depends on its relationship with the bipolar illness and also, importantly, on whether it has been so repetitive and persistent that dependence has developed. In the earlier phases of bipolar disorder with superadded substance use, the focus should be on effective management of the bipolar disorder, and substance use will generally respond to this as the hypomanic and depressive phases come under better control.

When dependence has developed, the substance disorder has to be treated in its own right so that parallel and integrated treatment of the two disorders is undertaken. Mostly, appropriate treatment for the substance dependence can be provided using the same combination of medications, therapies, and involvement with self-help fellowships that apply when substance disorders occur without any psychiatric comorbidities.

The value of a treatment program

The combination of bipolar disorder and a substance disorder is a challenging one, both for the person affected, for their close family and friends, and for health professionals. One of the advantages of a period of inpatient treatment is that the relationship between the bipolar disorder and the substance disorder can be thoroughly examined, and a conclusion drawn as to whether the substance disorder is symptomatic of the bipolar condition or has developed into a disorder in its own right. Furthermore, integrated treatment and therapy can be more effectively marshalled when the patient has a period of in-hospital treatment. One of the great rewards for mental health and substance use professionals is to see a patient who was disabled by this combination address their dual disorders, gain increased confidence in monitoring themselves and their treatment, and re-establishing themselves in productive employment and life beyond that.

Featured image credit: Faces By Geralt. CC0 Public Domain Via Pixabay.

The post Bipolar disorder and addictions appeared first on OUPblog.

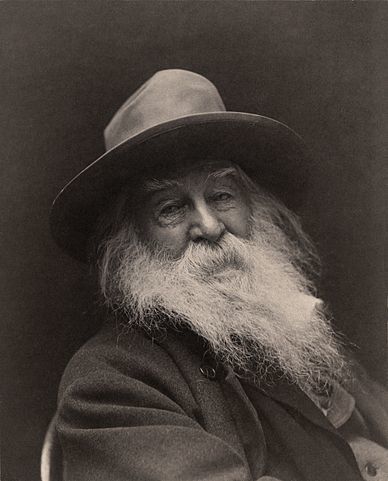

Where did Leaves of Grass come from?

One of the most enduring (if not most entertaining) games that Walt Whitman scholars like to play begins with a single question: Where did Leaves of Grass come from? Before Whitman released the first edition of his now-iconic book of poetry in 1855, he had published only a handful of rather conventional poems in local newspapers, which makes it seem as if the groundbreaking free-verse form in Leaves of Grass appeared virtually out of nowhere. Ralph Waldo Emerson was first to play the game of pondering the origin of poems such as “Song of Myself” when he wrote a letter to Whitman mere weeks after the initial publication of Leaves of Grass in the summer of 1855. “I greet you at the beginning of a great career,” he wrote, “which yet must have had a long foreground somewhere, for such a start.” Whitman published an open-letter reply to Emerson the following year that conveniently neglected to identify a foreground of any sort that would account for what Emerson had called “the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed.”

While Whitman may have ignored Emerson’s query regarding the origins of Leaves of Grass, it has not stopped scholars from trying to identify the elusive long foreground of his poems. Most of these scholars, however, are less concerned with finding a single, definitive piece of evidence that accounts for the genesis of Leaves of Grass than they are with cataloging the various cultural materials that could have influenced in one way or another the poet who famously said, “I am large, I contain multitudes.” Recently, University of Houston PhD Candidate Zachary Turpin discovered a long-lost 1852 novella by Whitman that has scholars and journalists eager to play a new round of “Where did Leaves of Grass come from?” The novella, titled Life and Adventures of Jack Engle, is a game-changing document that University of Iowa scholar Ed Folsom identifies as “the only piece of Whitman fiction that we know of that was written after Whitman began working on Leaves of Grass.” Jennifer Schuessler, writing in the New York Times, notes in particular a moment where “the madcap plot [of Jack Engle] grinds to a halt in favor of reveries about nature, immortality and the oneness of being that strikingly echo the imagery of Whitman’s great work [Leaves of Grass].” Folsom calls this swerve from narrative plot to poetic musing, “discovering the process of Whitman’s own discovery,” as the poet appears to have hit the limits of fictional prose and commenced experimenting with what was to become his idiosyncratic, free-verse poetic language.

American poet Walt Whitman, photo by George C. Cox. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

American poet Walt Whitman, photo by George C. Cox. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Setting aside for a moment what Jack Engle may or may not have to tell us about the birth of Leaves of Grass is another “process of discovery” that merits our attention: the process by which Turpin himself discovered the 165-year-old text. When I had lunch with Zack last fall in Philadelphia, he told me how the journey towards discovering Jack Engle began with puzzling over some unfamiliar names in Whitman’s notebooks—names that ended up belonging to the characters in Jack Engle—and then using those names as search terms to comb through electronic databases of digitized newspapers until he found an issue of The Sunday Dispatch where an installment of Whitman’s long-lost novella had first been published. When Zack told me that he had employed some online search tricks that he had learned from his previous life working for an Internet company, it brought to mind one of the ideas that I had recently written about for a special issue of the academic journal American Literary History on scholarly research in digital archives. Specifically, Zack’s clever use of search techniques to shake up the documents in the archive in such a way that the material he was looking for rose to the surface reminded me of what Lauren Klein, a web developer-turned-English professor, has said about using techniques derived from data visualization to “stir the archive” of digitized texts from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Digital archives are immensely valuable resources for scholars attempting to reconstruct our cultural past, but the information in these archives is often obfuscated simply by virtue of the volume of materials they contain. Scholars such as Professor Klein have invited us to use a variety of digital analysis tools—from data mining to network visualization—as a way to “stir up” the contents of an archive in hopes that some valuable new document will come into view. I had taken Professor Klein’s invitation and, with the help of my colleague Rob Weidman, found a bar song that had been written in the late 1850s that identified Whitman as a philosopher, rather than a poet. My sense is that this song says more about the people reading Whitman’s poetry in the 1850s than it does about the poetry itself, but maybe with this lead an enterprising scholar could stir the right archive and find a long-lost philosophical tract written by Whitman that would start up the next round of “Where did Leaves of Grass come from?”

Featured image credit: “Books” by Syd Wachs. CC0 Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Where did Leaves of Grass come from? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers