Oxford University Press's Blog, page 402

February 22, 2017

Bolder than a boulder and other stumps and stones of English orthography

One good thing about English spelling is that, when you look for some oddity in it, you don’t have to search long. So why do we have the letter u in boulder (and of course in Boulder, the name of a town in Colorado)? If my information is reliable, Boulder was called after Boulder Creek. A boulder near a small stream won’t surprise anyone, but the letter u in the word and the place name may, as journalists like to say, raise some eyebrows. Bolder (the comparative degree of bold), older, colder, folder, and holder do without u, but shoulder, unexpectedly, sides with boulder. American spelling has mold in all its meanings and the verb molder, while the British norm requires ou before l. What is going on here?

Perhaps the huge size of an average boulder contributed to the preservation of an extra letter in its name?

Perhaps the huge size of an average boulder contributed to the preservation of an extra letter in its name?The easiest case is old, cold, gold. The regular predecessor of –old in such words was either –ald or a short diphthong. Before ld, the vowel a (short, that is, ă) was lengthened in Old English, and in the group āl the vowel ā, obedient to the general law, became ō and later, by the Great Vowel Shift, yielded the diphthong [ou] or /ou/, if you prefer phonemic transcription. In such words, –old– is never spelled ould. But boulder and shoulder once sounded as bulder and sculder. Bulder turned up only in Middle English and is probably a word of Scandinavian origin, while sculder goes back to Germanic antiquity, as evidenced by German Schulter and Dutch schouder. To understand what happened here, it is useful to remember that there are (and have always been!) two l’s in English, called dark (or hard) l and light l.

Phonetic metaphors (light l, dark l, thick l—the latter sound exists in Norwegian dialects,—soft l, hard l—those varieties are distinguished, for example, in Russian) say nothing to the uninitiated, for what is, for example, thick l? How “thick” is it? But these terms do reflect the impression such sounds make on some people. Rather than being lost in terminological details, I’ll refer to the experience of those who can compare British and American speakers. The difference can be heard a mile off: British l is “light” (and so is German and Swedish l, as opposed to Norwegian). American l is “dark,” and even those Americans who speak otherwise impeccable German have great trouble with their l. The curious thing is that all of us hear the slightest trace of accent in others but not in our own speech—an almost perfect analog of the mote and the beam paradox, but transferred from the eye to the ear.

The parable of the mote and the beam is fully applicable to our view of accents.

The parable of the mote and the beam is fully applicable to our view of accents.The l called light shares some features with the front vowel i, while the closest neighbor of dark l is back (velar) u. Dark l is what we may hear if we pronounce it separately with strongly protruded lips. It will make the impression of the group ul, though u is, naturally, less audible than l. One can perhaps transcribe light l as [il], and dark l as [ul]. The history of English shows that [ul] is much more than an elegant (or whimsical) transcription by a professional linguist, because speakers did insert the vowel u before dark l in their speech. But for the influence of l, Modern English fall would have retained the vowel indistinguishable from the one in Modern German fallen. However, in English, [a] before l became [a-u], and this diphthong yielded the sound we now have. Such is the origin of the modern pronunciation of all, ball, call, hall, stall, and so forth. Exceptions are few: compare fallow, hallow, sallow, shallow, tallow, to say nothing of shall. Their history deserves special discussion.

For the same reason, shoulder has u in modern spelling. As we have seen, boulder and shoulder were once bulder and sculder. In principle, such words might have preserved their vowel intact, for they already had u before dark l! Yet for some reason, this did not happen, and ul also yielded a diphthong; hence boulder, shoulder, and others like them, in which ou, unlike au in ball, call, fall continued into Modern English unchanged. The consonant after l did not participate in this game: though d is voiced, while t is voiceless, coulter “part of the plowshare” and shoulder ended up with the same diphthong. This also holds for words like all: in falter, halter, Walter, voiceless t follows l, but it did not affect the main change. This fact is worth mentioning because in words like cold and old the ancient lengthening depended not on l but on the group -ld. Since in salt, a preceded –lt, salt and sold do not “rhyme.”

A short postscript to what has been said above may add a finishing touch to the phonetic history of the group represented by shoulder. Dutch has shouder, and this is not an unexpected form. Dark l, having performed its dark deed, disappeared, as behooves a criminal in a thriller. In English, such forms are rare, nearly nonexistent. However, the noun solder “the fuse used for uniting metal surface” has been recorded with three pronunciations: with a diphthong, as in sold; with a monophthong, as in saw; and with a short vowel without l, thus rhyming with fodder. Historical phonetics is full of such tricks: a sound causes a change and goes away, but the harm stays behind. If I may refer to my previous post, the model for such changes is Lewis Carroll’s Cheshire cat: the beast vanishes, but the grin remains. Later, it too can be lost, but this is another chapter in our story.

The phonetic leaps described above may be partly unexplained but, on the whole, they usually make sense. It should only be remembered that, though people “generate” sound changes, they have no control over them. By contrast, spelling depends on our will. For better or worse, the letter group –old– regularly designates the pronunciation, as in bold, cold, fold, and old. Consequently, inserting u after o is unnecessary. Eliminating it in mold and a few others (as in American spelling) was a reasonable measure, but shoulder and coulter are spelled alike everywhere. I don’t know why mold ~ molder, rather than shoulder and boulder, fell victim to the simplification. Perhaps it was decided that bolder and boulder should look different on paper.

Orthography is based on several principles, the phonetic one being only the most obvious among them. Morphology, that is, grammar, not pronunciation, makes us spell lacked / lagged and lacks / lags with the same endings pairwise (whether it is wise to do so need not bother us at the moment). Still another principle can be called iconic. Thus, it can be argued that bolder and boulder should be distinguished in writing, even though they are homophones. History too is often taken into consideration. Most likely, names will probably withstand any spelling reform. We all know that no English place or family name should be pronounced according to its visual image. If you are not sure how to pronounce Strachan or Willamette, just find out (Strachan rhymes with dawn, and for Willamette, should you put the stress on the first syllable, you may hear the gentle reprimand everybody knows in Oregon: “Willamette, dam’ it”). If boulder is ever changed to bolder, the place name should probably remain Boulder.

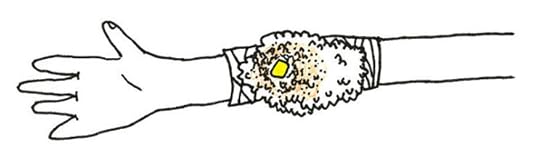

All this is very sad, but for the time being enjoy bolder, boulder, colder, coulter, shoulder, should, molder ~ moulder, solder, soldier, and poultry. If, however, you come away wounded, apply a poultice to the place that aches the most.

If after this exposure to the vagaries of English spelling, you need a poultice, help yourself.

If after this exposure to the vagaries of English spelling, you need a poultice, help yourself.Image credits: (1) Rock Dolerite by Ron Porter, Public Domain via Pixabay. (2) Zorab mote and beam by Minus (Minas) M. Zorab, 1880, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) “Poultice easily illustrated” by Snuvnia, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Featured image credit: Boulder, Colorado by marcelopmat, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Bolder than a boulder and other stumps and stones of English orthography appeared first on OUPblog.

Economic statecraft and the Donald

How will the Trump administration utilize economic statecraft and how will his approach be distinct from previous presidents? To answer these questions, we look to what we know about Trump’s stances and early actions on trade policy, sanctions, and foreign aid.

For much of the early history of the republic, economic statecraft was the primary bargaining tool employed. In fact, it was one of the few issues that Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson agreed upon while they served together in President George Washington’s cabinet. Even in some of the most important military engagements of our country’s history, economic statecraft has played an important role, like the North’s blockade of southern ports during the civil war, the Lend-Lease Act to assist our Allies and the embargo against Japan in World War II. We have not, however, constrained ourselves to only the use of sticks. The Marshall Plan was a defining element of the US’s early Cold War. Following the 9/11 attacks, the US also ramped up aid to countries willing to stand beside us in the fight against terror.

On the campaign trail, Trump had tough talk about many of our existing trade agreements and for many of our closest trading partners. As a successful businessman, he has touted his ability to get better deals for the US. Under the slogan “America First,” Trump has begun to move the United States in a more protectionist direction and has already pulled the United States out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership. In addition, during his first week, Trump notified both Canada and Mexico that he intends to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

These moves mark a sharp shift in US policy. Since the end of the World War II, American presidents, regardless of political affiliation, have advanced policies that encourage free trade and a globalized business environment. The United States was a founding member of the GATT and its successor organization the World Trade Organization. The United States created many of the institutions that dominate the global economy, much to its benefit as liberalization has spread. The likely consequence of many of these actions is that US influence in the global market, which has made it an influential sanctioner and important distributor of aid, will be diminished.

The US has been influential in setting the agenda on global health and development.

On the issue of sanctions, the Trump Administration’s position has been less clear. On one hand, he has issued new sanctions against Iran in the wake of its recent missile testing, despite claims that this action was outside of the purview of the Iranian nuclear deal. On the other hand, Trump has expressed interest in lifting sanctions against Russia and has already moved to ease those measures. On the campaign trail, Trump suggested he would both support the easing of sanctions on Cuba and that he opposed the easing of sanctions against Cuba. To date, he has taken no action on the issue. How the public will respond to this range of policies is unclear.

During the presidential race, Trump offered tough talk on foreign aid, causing many humanitarian groups to be concerned about how he will budget for this type of assistance. While Trump has offered some vague support for development assistance, he has more than once suggested that these funds could be used at home again as part of his America First agenda. In a speech in 2015, he asserted that the United States should “stop sending foreign aid to countries that hate us” and instead invest in our own infrastructure. Trump has already reinstated the ban on aid to groups abroad that provide abortion services. While typically, over estimating the amount of money the US spends on foreign aid, a large portion of American people see foreign assistance as a beneficial and moral thing for the country to do. Because of the scope of American aid (roughly 20% of the world’s total), the US has been influential in setting the agenda on global health and development. Walking back our aid commitments would also diminish our influence.

Throughout the latter half of the Twentieth Century, advancing American commercial goals was a part of the country’s foreign policy vision. With businessmen sitting in both the president’s chair and that of the secretary of state, it remains to be seen whether their “America First” approach will pay dividends for American businesses and America’s allies in the long-term. Abandoning long-held principles and practices in favor of the attention to America’s bottom line may have unintended consequences for our global leadership.

Featured image credit: Donald Trump by Gage Skidmore. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Economic statecraft and the Donald appeared first on OUPblog.

Inequality and new forms of slavery

The issues of social justice, poverty, and all the forms of human trafficking, deployment, and oppression that can be grouped under the umbrella concept of “slavery” are problems that sorely affect the world today and urgently need concrete solutions. But they are not at all new problems; on the contrary, they were prominent and discussed already in antiquity and especially in late antiquity — a period in history that bears impressive similarities to our contemporary multi-cultural, multi-religious, and interconnected (“globalized”) world, with many conflicts to mediate and increasing inequality to correct. Investigating, and reflecting on, late antique history, society, philosophy, and religion can prove extremely valuable for humanity today, and for the improvement of human condition—what philosophy and religion should aim at.

Philosophical reflections on slavery and social, economic, and gender inequality, however, sometimes have proved to support the status quo instead of improving it. This is the case, for instance, with Aristotle: in his descriptive attitude—visually represented in Raphael’s School of Athens fresco—he provided a description and justification of existing relations of subordination (master-slave, man-woman, etc.) as normal and “natural”, whereas other philosophers, such as the sophists first and the Stoics after, questioned the naturalness of such relations of subordination. Consistently, Stoics and Epicureans admitted at school slaves, women, and people of every ethnic background, rejecting Aristotle’s theory of the inferiority of slaves, women, and barbarians “by nature” (notably, the same categories of inferiority—social, gender, and ethnic inferiority—were rejected by the Apostle Paul in Gal 3:28).

The Stoics, however, like many ancient Christian thinkers, by considering slavery and other forms of oppression and subordination something morally “indifferent” (neither good nor bad), diverted the attention from the injustice that is inherent to slavery, poverty, the inferiority of women, socioeconomic inequality, and the like, since they rather focused on the moral plane and insisted that the real problem was moral enslavement to passions. In this way, institutional slavery, subordination, and oppression fell into the background. Many Christian thinkers considered social injustice, slavery, the subordination of women, and the like, to be sad but inevitable consequences of the original sin (the so-called Fall), or even an expression of God’s will.

These late antique ascetic thinkers’ arguments and practice, which were met sometimes with interest but also with stark opposition, are highly relevant to the debate on social justice as part and parcel of human rights today.

But not all Christian thinkers in late antiquity maintained that God endorsed inequality, subordination, discrimination, and slavery as expressions of divine justice. On the contrary, refined Christian thinkers such as the Platonist follower of Origen of Alexandria, Gregory of Nyssa, in the late fourth century rejected social injustice leading to poverty, the subordination of women, and especially slavery as contrary to God’s will and to God’s justice. This line of thought emerges especially within philosophical asceticism, in imperial and late antiquity, within Judaism and Christianity, and sometimes “pagan” philosophy, most probably because this kind of asceticism was related to a self-restraint that was not simply renunciation, or even hatred, of the body and of the world (as asceticism is sometimes simplistically portrayed), but was inspired by the ideal of justice.

Indeed, the very notion of social justice, entailing an even distribution of the goods of the earth and thus of wealth among all humans, is not only modern, but was already at work in some late antique thinkers within the tradition of philosophical asceticism. The connection between philosophical asceticism and justice was already established by Plato, but it is late antique philosophical ascetics that made the most of this connection, and also endeavored to apply it to the society that surrounded them. Their radical principle that wealth exceeding one’s needs is tantamount to theft, in that it deprives other people of what they need, on the grounds of the universal destination of the goods, was based on a principle of justice. Renouncing excessive wealth, or even any wealth in the case of strict ascetics, was a matter of justice towards other people. One’s relation to the divinity, they maintained (from the Christian-Pythagorean Sentences of Sextus to Gregory of Nyssa), is jeopardized by one’s injustice and oppression of other people. As Gregory puts it, spiritual asceticism is abstinence from oppressing others and “robbing the poor with injustice.” It also consists in prioritizing human beings over things (money, wealth).

These late antique ascetic thinkers’ arguments and practice, which were met sometimes with interest but also with stark opposition, are highly relevant to the debate on social justice as part and parcel of human rights today. The inclusion of socio-economic equality within human rights is not a novelty of some contemporary theories (on which see Holman 2015), but arguably goes back to the reflections and behaviors of late antique philosophical ascetics that are worth reading and studying carefully, and paying attention to.

Featured image credit: “Christ”, by Didgeman. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Inequality and new forms of slavery appeared first on OUPblog.

February 21, 2017

The cultural politics of “othering”

President Trump’s executive order ending immigration from seven Muslim-majority countries has intensified a vituperative debate in American society, which has been ongoing since long before candidate Trump formally remarked on it. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s four successful presidential campaigns created a bipartisan consensus that cast the immigrant experience as an extension of a narrative beginning on Plymouth Rock. In the final days of his 1936 campaign, Roosevelt, speaking on Ellis Island and again on New York’s Lower East Side, paid tribute to immigrants as the new quintessential Americans:

They came to us speaking many tongues—but a single language, the universal language of human aspiration.

They were not satisfied merely to find here the realization of the material hopes, which had guided them from their native land.

They were intent also on building a place for themselves in the ideals of America.

They sought an assurance of permanency in the new land for themselves and their children, based upon active participation in its civilization and culture.

In early February 2017, the first Black History Month of the Trump presidency, my students at the University of Oklahoma and I were discussing Booker T. Washington’s “Atlanta Exposition Address,” in which he pleaded with white Southern leaders to choose the American “Negro” to labor in the nation’s fields and factories—”the most patient, faithful, and law abiding people that the world has ever seen”—over those of “foreign birth and strange tongue and habits.” These words may reflect Washington’s own prejudices (and those of many in his generation), but they also provide a ruthlessly accurate assessment of a minority group’s forced social and political retreat during another time of crisis. In effect, African-Americans and immigrants had been pitted against each other.

Portrait of W.E.B. Du Bois, co-founder of the NAACP, in 1918. Photo by Cornelius Marion Battey, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of W.E.B. Du Bois, co-founder of the NAACP, in 1918. Photo by Cornelius Marion Battey, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Today, more Americans than ever before acknowledge the value of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s statements about immigrants from 1936. But we must not forget that Roosevelt never chose to speak quite as directly and explicitly to and about African-Americans as equal members of the American polity. Instead, Roosevelt spoke of African-Americans primarily through a language of symbolic actions—standing beside boxer Joe Lewis, for instance, extolling his quiet strength as an example of what made America strong.

Still, as president in economic depression and then in war, Roosevelt undoubtedly came to understand what W.E.B. Du Bois had first proposed in 1903 (in the “forethought” to his classic book, The Souls of Black Folk): that “the problem of the twentieth-century is the problem of the color line.” It was an issue that had deep implications for the nation that Roosevelt, then only a state senator from New York, would lead to the rank of “super power.” In the post-colonial world order that emerged after World War II, African-Americans fought to make gains in the nation’s political culture. Abroad, the manner in which African-Americans were treated by their fellow citizens and institutions became a litmus test of whether the United States was worthy of being the leader of the “free world.”

African-American intellectuals such as Alain Locke, Zora Neale Hurston, and Rayford Logan had pushed the frontiers of scholarship by their painstaking documentation of and argumentation for the fact that African-Americans had been central actors in the history of the United States—not just in the nation’s physical development, but in its thought and sense of self. Intellectual innovators such as Frederick Douglass, by force of evidence and logic, recast the ideological framework within which one could live and act as an American. For thinkers like Douglass, the idea of citizenship related no more to a “Whites Only” nation than it did to a community in which the native born were entitled to rule over politics and culture.

Studying the “Long Civil Rights Movement” (with W.E.B. Du Bois, Langston Hughes, Mary McLeod Bethune, Ralph Ellison, and James Baldwin among its architects and builders) shows us that the social, political, and geopolitical fate of the United States depends on whether the social and material actualities of citizenship can be extended to those “outsiders” who have followed the trajectory of African-American history. After all, a citizen is more than someone who, at best, receives the nation’s “tolerance,” or is accepted as just another “other” in our midst. James Baldwin offered these words about the American Republic in The Fire Next Time:

If we, who can scarcely be considered a white nation, persist in thinking of ourselves as one, we condemn ourselves, with the truly white nations, to sterility and decay, whereas if we could accept ourselves as we are, we might bring new life to the Western achievements, and transform them. The price of this transformation is the unconditional freedom of the Negro…he who has so long been rejected, must now be embraced, and at no matter what the psychic or social risk (pp. 93–94).

Much has changed in the cultural, political, and demographic constitution of the United States since Baldwin wrote these words, in 1963. If we are to prevail today against terrorism of any kind and from any source, whether foreign or domestic, we must protect the various communities that make up our polity, and acknowledge that we are a far more diverse people than ever before. This is progress, and it’s a reason for national pride.

Featured image credit: Booker T. Washington and President Theodore Roosevelt in 1905 at the Tuskegee Institute. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The cultural politics of “othering” appeared first on OUPblog.

The history of global health organizations [timeline]

Established in April 1948, the World Health Organization remains the leading agency concerned with international public health. As a division of the United Nations, the WHO works closely with governments to work towards combating infectious diseases and ensuring preventative care for all nations. The events included in the timeline below, sourced from Governing Global Health: Who Runs the World and Why?, show the development of global health organizations throughout history.

Featured image credit: Pills by Stevepb. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post The history of global health organizations [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

ISA 2017: a city and conference guide

The 2017 International Studies Association meeting will be held this year from 22 February until 25 February in Baltimore, Maryland. The International Studies Association is one of the oldest interdisciplinary associations devoted to studying international, transnational, and global affairs since 1959. The 58th Annual Convention is dedicated to understanding change in world politics and will bring together nearly 6,000 people for over 1,500 panels, special programming, and events.

ISA has plenty to offer that will keep the week full and busy. These are just some of the many events we’re excited about this year:

Wednesday, 22 February 8:15 – 10:00 AM,

Mapping change and changing the map of International Studies, Roundtable

Wednesday, 22 February 10:30 AM – 12:15 PM

Academic Freedom, Terrorism, and Counter-Terrorism committee panel by the Academic Freedom Committee

Thursday, 23 February 8:15 -10:00 AM

The Problem of Peaceful Change: Theories, Possibilities, and Levels of Analysis, Presidential Roundtable

Thursday, 23 February 10:30 AM – 12:15 PM

Roundtable on Stephen G. Brooks and William C. Wohlforth’s America Abroad: The United States’ Global Role in the 21st Century.

Thursday, 23 February 1:45 – 3:30 PM

International Relations Confronts a Diverse World and Stormy Past committee panel by the Committee on the Status of Representation & Diversity

Thursday, 23 February 6:15 – 7:00 PM

ISA Presidential Address & Reception

Friday, 24 February 8:15 – 10:00 AM

Embodying International Relations, Roundtable

Friday, 24 February 1:45 – 3:30 PM

Future of Liberal World Order, Sapphire Series

Saturday, 25 February 10:30 AM – 12:15 PM

New Theories of Media and Mediation, Panel

Saturday, 25 February 10:30 AM – 12:15 PM

Exploring neoclassical realist ideas about how to understand and explain change in a post-unipolar world order, Panel

Saturday, 25 February 1:45 – 3:30 PM

Power and Peace: Systematic Constraints and Domestic Conditions for Peaceful Change, Presidential Roundtable

Aside from ISA, the city of Baltimore has plenty of landmarks, museums, and restaurants to check out while in town. We’ve picked out a few of our favorite things that Baltimore has to offer.

If you’re interested in getting acquainted with the views, scenic water taxis shuttle along the Inner Harbor seven days a week from 11 AM to 6 PM.

Visit the Baltimore Museum of Art to explore the largest and most significant collection of Henri Matisse’s works in the world. If the weather is in your favor, venture outside to the Sculpture Garden where workshops and gallery tours are offered free of charge every Sunday.

The neighborhood of Federal Hill is worth a visit for its picturesque brick houses and cobblestone sidewalks. Federal Hill offers a great deal of local shops as well as plenty eateries to satisfy any seafood cravings one might have while visiting the harbor.

Finally, one of Baltimore’s most popular attractions is the National Aquarium. Explore the nearly 20,000 animals that reside in the aquarium. From an authentic reef in a 335,000 gallon 13-foot-deep exhibit to Shark Alley, to a 225,000 gallon ring-shaped exhibit with sharks of dozens sizes and types, the aquarium is a must-see before leaving.

While at the convention, don’t forget to stop by the Oxford University Press booths; 5, 7, 9, and 303. Browse our new and featured titles at a special conference discount and follow @OUPPolitics on Twitter to stay up to date on ISA 2017. We hope to see you in Baltimore!

Featured image credit: Baltimore Harbor by bensonk42. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post ISA 2017: a city and conference guide appeared first on OUPblog.

Why Bob Dylan deserves the Nobel Prize

Laudatory op-eds and articles began appearing online and in print shortly after the Nobel Prize announcements on 13 October 2016. Bob Dylan had won the literature prize. On that very same day, New York Times music journalist Jon Pareles began his op-ed reflection on the award with the question, “What took them so long?” But the news wasn’t without detractors. Several friends and colleagues of mine, for example, expressed everything from puzzlement to dismay. One friend sent me a text shortly after the announcement critiquing the news as the lousiest choice since the prize was awarded to Winston Churchill in 1953. Dylan was a talented pastiche artist. This friend believed that pop stars like Leonard Cohen and Lou Reed were more deserving on the poetic level. Another friend, the smartest Shakespearean I’ve ever known, saw it as a literary debasement. It was emblematic of the gradual death of the literary text. He’d even spent some time after the announcement printing out lyrics from Dylan’s classic period in the mid-sixties, hoping to find literary merit in the verses at the level of a Wordsworth, Dickinson, Whitman, or Shakespeare. But the lyrics seemed thin to him without the music and Dylan’s idiosyncratic vocal inflections to lift it all into life.

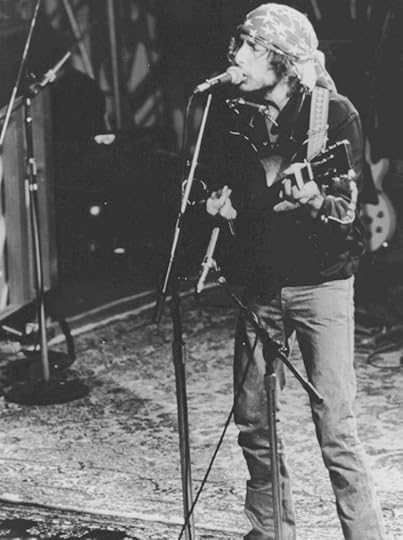

Bob Dylan performing in Hard Rain, the first television special he starred in. Credit: “Bob Dylan Hard Rain” by NBC Television. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Bob Dylan performing in Hard Rain, the first television special he starred in. Credit: “Bob Dylan Hard Rain” by NBC Television. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.From my perspective, the Nobel Prize Committee was perceptive when it recognized Dylan’s importance as a sampler and promulgator of tradition, and as the innovator of a great and original American songbook. Over the years, his musical identities have channeled the personae of a dustbowl Okie, a Beat poet, a Nashville songwriter, a Born Again holy roller, and a delta bluesman. Lyrics and melodies from the ’50s, ’40s, ’30s, and much earlier, flow through his albums like a Biblical deluge. And there are so many literary forms embedded in his lyrics: ballads, talking blues, jeremiads, sermons, elegies, dramatic monologues, and surrealist language experiments. Not to mention the fact that Dylan routinely appropriates themes and quotations from artists as varied as Henry Timrod, Muddy Waters, John Keats, and T.S. Eliot, keeping these writers circulating within public consciousness.

But it’s not just this. It’s what Dylan does with tradition that’s truly remarkable. Modernist poet Ezra Pound’s magnum opus, The Cantos, share characteristics with Dylan’s body of work insofar as both artists draw on a polyphonic range of cultural traditions, vernaculars, and literary forms. Pound imagined that the disparate pieces of his creation were similar to iron filings on a mirror. Each filing is separated from the others, but they are drawn into a rose pattern by the presence of a magnet. Bob Dylan’s songs – sung in different voices, in different moods, on different life occasions, and chipped off different cultural blocks – possess a unifying coherence. Although I’m hesitant to explain what it is, I’m certain that it is. T.S. Eliot, who’s “fighting in the captain’s tower” with Ezra Pound in Dylan’s famous song “Desolation Row,” wrote in his essay “Tradition and Individual Talent” that a poet needed to embody the whole of literature, from its classical sources to its contemporary ones. He believed that “the most individual parts of his [the poet’s] work may be those in which the dead poets, his ancestors, assert their immortality most vigorously.”

Beyond the quality of his work, Bob Dylan is perhaps second only to William Shakespeare in the effect he has had on English as a spoken language. Toward the end of his life, the poet Allen Ginsberg praised his younger friend’s intuitive understanding of orality. The great Bardic tradition of Western culture is populated by artists who lifted their voices to song, from Homer to Sappho to the wandering minstrels of the middle ages. In the mid-Twentieth Century, Beat poets, like Ginsberg, Kerouac, and Corso, tried to free poetry from the desiccating clutches of academia by reading, and at times singing, their verses to live audiences of mixed age, race, socioeconomic standing, and gender. After fifty years of doing similar, at times brilliantly and at times imperfectly, Dylan’s poetry has infiltrated the popular lexicon, appearing in everything from political speeches, to legal briefs, to everyday slang. And whether or not his lyrics seem thin on the page, they run through deeply through the complicated and violent culture that inspired a young Robert Zimmerman to pick up his guitar and sing.

Featured image credit: “Bob Dylan and The Band” by Jim Summaria. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why Bob Dylan deserves the Nobel Prize appeared first on OUPblog.

The sound of the police

With dates for both the NPPF Step Two Legal Examination for police sergeants and National Investigators Examination looming closer, we’ve put together a playlist to help get you through your revision. Stuck trying to get your head round a tricky piece of legislation? Maybe it’s time to take a break from the books. We’re (almost) certain you’ll feel a renewed sense of enthusiasm for studying for that promotion exam after hearing our selection of police-related tracks. Full disclosure: some of the connections may be more tenuous than others…

Featured image credit: ‘traffic-lights-highway-night-blue’, by Tobias-Steinert. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The sound of the police appeared first on OUPblog.

February 20, 2017

“Don’t cry white boy. You gonna live”

On 20 February 2017, Sidney Poitier—”Sir Sidney” both in the colloquial and in reality (he was knighted in 1974), and just “Sir” in one of his biggest hits, To Sir, With Love (1967)—will turn 90 years old.

Even today, Poitier continues a decades long career of collecting accolades for his pioneering role as Hollywood’s first black movie star. Just last week at its eighth annual awards ceremony, the African-American Film Critics Association bestowed Poitier with its inaugural “Icon Award.” That honor joins the knighthood, two Oscars, and a Presidential Medal of Freedom, along with many others, in Poitier’s trophy case.

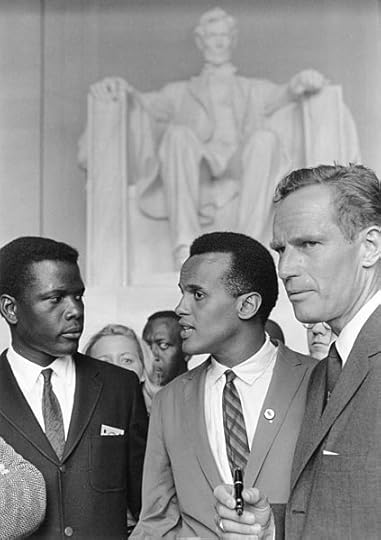

At the same time, Poitier also continues a nearly equally long career of carefully calibrating the connection between his stardom and racial politics in the United States. Poitier’s fellow star, friend, and foil Harry Belafonte has long spoken forthrightly on matters of race and social justice, most recently in the 5 February 2017 New York Times. In contrast, Poitier mostly lets his work do the talking; I must note, however, that Poitier was vigorously engaged in the Civil Rights Movement and was a prominent fundraiser for the Movement.

As the United States has moved, seemingly abruptly, from the Obama era to the Trump era, I’ve been wondering what we might hear in Poitier’s work.

One answer—certainly one that was prominent at the height of Poitier’s career in the late ’60s—would be: conciliatory, “dignified,” and maddeningly limited gradualism (“dignified” is almost certainly the adjective most persistently used in relation to Poitier). Many film and cultural critics noted in 2008 that Poitier could be seen as a pre-figuration of Barack Obama, and in his autobiography, Obama wrote of Poitier as among his youthful role models. At the threshold of the Obama Presidency, this way of seeing Poitier seemed a sort of delayed, radical conclusion to Poitier’s career (his last role as an actor was in 2001, though he published his third autobiography, Life Beyond Measure, in ’08). Poitier’s harshest critics of the late ’60s and ’70s saw him as “an old [uncle] tom dressed up with modern intelligence and reason” (the words are Donald Bogle’s) for his role in making white people feel OK about interracial marriage in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967). Maybe Poitier’s character, John Prentice, a world renowned doctor who imagines his biracial children would one day be Secretary of State, if not President as his fiancé predicts, was getting the last laugh with President Obama’s inauguration. Or maybe John Prentice’s 2017 analogue is Ben Carson, a medical doctor of considerable repute, proposed as President Trump’s Secretary of…Housing.

Other aspects and texts of Poitier’s stardom, though, resonate more clearly critically in the current moment.

Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte, and Charlton Heston at the Lincoln Memorial during the Civil Rights March on Washington in August, 1963. National Archives and Records Administration, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte, and Charlton Heston at the Lincoln Memorial during the Civil Rights March on Washington in August, 1963. National Archives and Records Administration, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Poitier could only become Poitier because of the US traditions of international trade, natal citizenship, and opportunities for immigrants. Poitier is a dual United States-Bahamian citizen. He was born, prematurely, in Florida, where his Bahamian parents had traveled by boat to market their tomato crop. He lived in the Bahamas until his middle teens, but was sent to live in the United States as he neared adulthood. Because of his US birth, he was “legal”—unlike his brothers, one of whom was arrested three times trying to enter the United States and one of whom did immigrate and gain legal status by marrying an American, providing Sidney a place to land in Miami. Still, “legal” or not, young Poitier was Bahamian—obviously so in his accent. He moved to New York City when the “barbed wire” (Poitier’s words in an early star-level national press profile in Newsweek, 1957) of Jim Crow Southern racism became too much, and New York allowed Poitier the American dream of remaking himself—most pointedly remaking his literal voice. Poitier is an embodied argument for the benefits of an America envisioned as an open, welcoming, cosmopolitan if also profoundly imperfect nation.

And then there is Poitier’s first major role in No Way Out (1950), an underappreciated, under-seen, unconciliatory noir-social problem film mash-up. Poitier plays the first of his many doctors, Luther Brooks a young intern who is integrating the medical staff of a big city hospital. Johnny Biddle, a white man brought in for emergency treatment of a minor leg wound suffered when he robbed a gas station, dies mysteriously under Luther’s care. Johnny’s brother, Ray, a virulent racist, vows revenge. Luther waivers between certainty that his diagnosis of meningitis was correct and self-doubt. Maybe he made a mistake? Maybe his antipathy to Johnny and Ray made him lose his focus? Maybe he’s not qualified? His loving wife, extended family, and black neighbors and co-workers all support Luther, creating a sense of black community rare in Hollywood movies, including many of Poitier’s. Ray hatches a double plot: His friends will attack Luther’s neighborhood, igniting a race war that Ray is confident the whites will win; meanwhile, Ray will hunt and kill Luther.

An African-American man passing for white tips the neighborhood to Ray’s plan, and a group of black World War II veterans trap and attack the plotters. The hospital is inundated by wounded and dead men, white and black. Luther is caught by Ray, who prepares to shoot him in the head, point blank. But Johnny’s ex-wife Edie (who’s been brought into the investigation into what killed Johnny; Luther’s diagnosis was correct) kills the lights. In the darkness Luther is wounded but disarms Ray, who reopens the injury he suffered in the robbery that caused his and Johnny’s paths to cross Luther’s.

Edie argues that Luther should kill Ray—even offers to do it herself: “He’s not even human. He’s a mad dog. You kill mad dogs, dontcha?” Despite his own rage, Luther tends to Ray: “Look—he’s sick, he’s crazy, he’s everything you said, but I can’t kill a man just because he hates me…Because I’ve got to live, too.” Luther fashions a tourniquet from Edie’s black and white polka dotted scarf and Ray’s pistol, which Luther carefully empties. They fasten it to Ray’s upper thigh, just below his groin. Sirens approach. Edie steps away to prepare to let the police in. Ray weeps from an apparent combination of pain, rage, shame, and cognitive dissonance. With a tiny smile suggesting a sadistic satisfaction Luther twists the pistol, tightening the tourniquet, and has the last word: “Don’t cry white boy…you gonna live.” Ray sobs.

In 1950, No Way Out was banned in many places in the United States—and not just the South, but also in places like Chicago, which in a few decades would become Barack Obama’s hometown. To quote Hemingway at his most hardboiled, “isn’t it pretty to think” that if more Americans had seen No Way Out then or since, the United States might have come to the conclusion that Robert Frost’s 1915 poem “Servant to Servant” does (admittedly Frost isn’t addressing race)?

The best way out is always through.

And I agree to that, or in so far

As that I can see no way out but through…

It’s pretty to think so. But it didn’t come to pass.

Nonetheless, Sir Sidney is still here at 90, reminding us with his presence of what an open America can be, what it can have and create. And reminding us with his gritty first big movie role that we have known for a long time the traps we are in—and that if we struggle, collaborate, and chose our paths wisely, we may get out. If we’re lucky.

Happy Birthday, Mr Poitier. Thank you for your gifts.

Featured image credit: Sidney Poitier hugs President Barack Obama after receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom in August 2009. Pete Souza, White House, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post “Don’t cry white boy. You gonna live” appeared first on OUPblog.

Isolation driven by technological progress – does anyone care?

The hype of technological progress is that it will change the world and make life better for everyone. For young technologists, this may be true, but their blinkered vision does not recognise that, not just the elderly, but many others, cannot cope with electronic communications and the benefits of on-line shopping or banking, etc. In many developed nations 25% of adults are of retirement age. Even for the fit and healthy ones, their colour vision will have significantly changed. They have difficulty seeing the blue end of the spectrum, they need larger typefaces, and better contrast. This is totally the opposite of the innovations from young designers, who introduce novel and more subtle colours, with weaker contrast and smaller fonts. Electronic displays use deep blue light sources in black backgrounds. Fine for teenagers, but totally unreadable for most pensioners.

Physical limitations of large fingers, stiffness from age or manual labour, and the normal shakiness with older hands are often met with keyboards that are too small and touch screens on compact smart phones that are frequently unworkable. Voice recognition alternatives are very public and fail to adapt to quavering voices, high pitch, or regional accents. Finding large computer keyboards is difficult; smart phones with a large button keypad do not seem to exist. These examples are just the tip of the iceberg. Marketing is ignoring a quarter of the population and focusing on gimmicks, games, and new apps to seduce gullible youth into buying the newest fashionable annual variants. The profits of this deliberately driven obsolescence are large, and the older market is ignored. Do designers not have parents and grandparents who can pressure them to change their ways?

Most services use electronic phone and computer contacts for answering questions and transactions such as banking. These are challenging for many people who prefer to speak to real people, not an automated voice response, or software which is not intuitive to a generation that did not grow up with it. Such uncertainties make these same people very vulnerable to computer fraud and scams, despite warnings that the emails or phone calls from their “bank” are rarely genuine. To the elderly, who are computer insecure, the phone calls claiming to be from a reputable software provider who need access to the computer are often taken at face value, with a resulting cost and lack of security.

Senior citizens class photo by Pavla Pelikánová. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via the Wikimedia Blog.

Senior citizens class photo by Pavla Pelikánová. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via the Wikimedia Blog.More subtle scams, which may be technically legal, are where one uses the internet to contact a government department but does not notice the listing is via an advert. Everything then appears to be on a normal form, but inevitably there is a trap where one ticks a box that then results in having signed up to a long standing financial subscription, automatically deducted from the card or bank account. If the sum is modest then it may be never recognised.

Isolation is not confined to the old, but hits as hard at young people who are poor, or with limited knowledge. Finding employment in a society where many simple jobs have been taken over by computer software is increasingly difficult. Entrepreneurs see this move as good business, and for them it is, but the euphemistic “leisure time from repetitive work” means unemployment. The trend to make applications and interviews entirely online is a disaster for those that lack the skills to do this, even when they are well suited to the work that is available. Employers do not seem to recognise that face to face interviews are far more informative, and may settle for the apparently cheap option.

An ageing population should be delighted with advances in technological progress in medicine, but they should admit that extending life expectancy is only desirable if the quality of life is also maintained. Increases in the numbers of cancer and Alzheimer patients are in part merely the consequence of our ability to prolong life. Equally, medical “efficiency” may involve a few specialist units. Whilst they may be excellent, they do not replace the contact with a local doctor, who might even recognise you. I have seen many examples where patients have early morning appointments in the specialised treatment centres, that totally ignore the feasibility of an elderly person being able to reach them in time. The result is no treatment.

While technological progress does present a range of challenges to the ageing individual, one shouldn’t give up on it completely. To avoid being isolated as technology advances, my advice is to keep trying, proceed with caution, and maybe even associate as much as possible with young people; you will stay mentally young, this will keep you fit, and they can solve your technology problems.

Featured image credit: Computer Eyewear by Michael Saechang. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Isolation driven by technological progress – does anyone care? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers