Etymology gleanings for March 2017

Many thanks for the comments. One of the questions was about the dialect that could be used for the foundation of a new norm. No spelling can reflect the pronunciation of all English speakers. An ideal system, that is, phonetic transcription ([nou] or [neu], or [nöu] for no; [faiv], [foiv], or [fahv/ fa:v] for five) is out of the question. The hope is to retain what we have but rid it of the most obvious silliness and redundancies (mute and double letters, among others). There is no consensus about how far the reform should go, but all English speakers pronounce give, you, and done in approximately the same way, so that, if we respell such words as giv, u, and dun, no one will be “marginalized.” At this stage, reformers should only try to persuade the public that they are doing something beneficial to the world. Judging by the experience of other countries, I, for one, see no harm in abolishing the letters q and x (siks, kwite), leaving them, if necessary, in Quentin and Xerxes; replacing sc with sk, and so forth.

Truly instructive is Mr. Jevgēnij Kuktiņš’s story of the Latvian spelling reform. As an outsider, I am not a fan of the Latvian alphabet, because all diacritics are a nuisance. French children have a hard time even learning their é’s and è’s, while Latvian offers a veritable feast of special signs. This, however, is not my point. It appears that in recent history, Latvians agreed to introduce radical changes and are now “kwite” happy with what they have. To be sure, there is a difference: English is spoken by many million people all over the world, so that the odds are long, but Webster had his way with the changes of –ise to –ize, mould to mold, and colour to color. Perhaps the battle is not yet lost. The main thing is to begin it.

(By the way, Ouida’s name is pronounced wee-dah!)

Two ways of shutting up

I do know the history of u in words like but and put. When the Great Vowel Shift turned long u (that is, ū or [u:]) into the diphthong most modern speakers have in how, now, vow, short u followed suit and changed to an a-like vowel (a, as in Italian or German), because in the history of the Germanic languages, short vowels usually take their cue from their long partners. The change was not consistent, especially after the labial consonants b, p, f; hence bulb versus bull and fun versus full. The north of England did not participate in the change of short u. When our family lived in Cambridge (England), the science teacher in our son’s school began every lesson with the words SHOOT OOP. He was obviously a northerner. The famous philologist Joseph Wright grew up in Yorkshire, and his son used to mock him gently for his accent. There is a two-volume biography of Wright, written by his wife. Personal touches are few in it, but it is still a good book to read. And, yes, I also know about the present-day administrative division of Yorkshire, but thank you for the remarks: all comments are appreciated.

Cheshire cat and chessie/chessy

I was happy to read the comments on the impenetrable grin. After years of working with the origin of idioms, I have come to the conclusion that the beginning of our proverbial sayings, unless they go back to so-called familiar quotations, is beyond recovery. This may surprise even historical linguists: no phonetic laws or grammatical classes, no shaky semantic bridges, no protolanguage, and yet complete obscurity. Just try to explain why we should mind our p’s and q’s! Even more surprising is the circumstance that words are often extremely old, while idioms are usually not, and still their etymology is unknown.

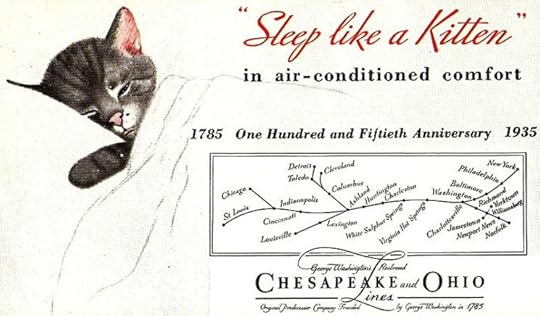

This is the famous Chessie kitten, unsmiling but cute.

This is the famous Chessie kitten, unsmiling but cute.Peter Maher reminded me of Chesapeake & Ohio Railway and of Chessie Systems in connection with the chessy cat, mentioned in my post. My search for the chessy cat immediately yielded C&O Railway, but the famous label (a cute kitten) is too late for explaining the origin of chessy. However, it does prove that the word chessy was known far away from Philadelphia, where it may have originated. Other than that, cat folklore is rich, and the grin of the Cheshire cat surely reminds one of a chain. But where do we go from this indubitable fact? To smile like a basket of chips, mentioned in the comment by Stephen Goranson, is a well-known idiom. I once heard it from an American speaker, and, if I remember correctly, he used it without reference to smiling (the meaning was “on a grand scale”), more or less synonymous with like a house on fire. I can imagine chips lying in two rows and resembling a mouth full of teeth—a captivating smile. But a grinning cat from Cheshire? Perhaps one of the explanations I quoted is correct after all. By the way, one can also smile like a brewer’s horse. Is the brewer’s horse always drunk?

A basket of chips: it will make you and your dentist smile.

A basket of chips: it will make you and your dentist smile.Odds and ends

To dine with Duke Humphrey “to stay without dinner.” Yes, indeed, the usual form of the idiom is to dine with Duke (not Earl) Humphrey, but in my database, the phrase turned up in its rare form, and I decided to quote it. I am sure many people share my experience and remember where they first encountered a rare word or an exotic idiom. In the introductory chapter to Martin Chuzzlewit, Dickens relates the glorious history of Martin’s ancestors. According to the extant records, one of them was especially distinguished, for he often dined with Duke Humphrey. But for a footnote, I, at that time a student, would not have understood the joke, which goes a long way toward repeating the truth, worn-out almost threadbare: “Don’t reprint classics without comments!”

Gerhard, the Devil’s name. Thank you for the reference to Geeraard de Duivelsteen, a 13th-century castle. Nothing is said about Geeraard’s reputation: he was swarthy, rather than evil. If Gerhard had already been known as one of the Devil’s many names, the dark-complexioned knight sheds no light on the idiom, and, if the name is more recent, it hardly refers to the castle’s owner.

Geerard de Duivelsteen, a 13th-century building, named after the knight Geerard Vilain. The owner was neither a devil nor a villain.

Geerard de Duivelsteen, a 13th-century building, named after the knight Geerard Vilain. The owner was neither a devil nor a villain.Bother and copacetic. I did try to find a Dutch etymon for bother! Nothing turned up. And the information on copacetic warms the cockles of my heart, for I am busy working on the letter C of my etymological dictionary, which shows what remarkable progress I am making toward the end of the alphabet.

Apostrophizing the overkill. One of the things Spelling Reform should fix is the use of the apostrophe. It is almost impossible to teach undergraduates the use of this nefarious sign. In my course “German Folklore,” I spend a whole semester imploring the students to write the Grimms’ Tales rather than the Grimm’s Tales (though they know that there were two brothers and agree that the Grimm is nonsense, they keep writing the phrase their way). But lo and behold! A correspondent sent me a text with the words y’all’re. He wonders whether there is not too much of muchness in it. I am afraid there is.

More answers in April, after its sweet showers have pierced March.

Image credits: (1) “Chesapeake and Ohio 150th anniversary 1935” by Chesapeake and Ohio Railway, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) “handful of biomass” by Oregon Department of Forestry, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr. (3)”Geeraard de Duivelsteen” by Paul Hermans, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Featured image credit: “Latvia 1998 CIA map” Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Etymology gleanings for March 2017 appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers