Amy Julia Becker's Blog, page 8

June 3, 2025

S8 E19 | The Cost of Ambition with Miroslav Volf, PhD

Ambition is the air we breathe—but what is it costing us? In this episode, Amy Julia Becker and theologian Miroslav Volf discuss his latest book, The Cost of Ambition. They unpack the hidden damage of a culture obsessed with competition and invite us to imagine a new way of being, for ourselves and our society, rooted not in achievement, but in love, mutuality, and genuine abundance. They explore:

Striving for superiority in American cultureThe dark side of competitionLonging for what we haveStriving for excellence vs. striving for superiorityThe illusion of individual achievementPractices for embracing love and generosityReimagining human relationships beyond superiority SHOW NOTESMENTIONED IN THIS EPISODE:

The Cost of Ambition: How Striving to Be Better Than Others Makes Us Worse by Miroslav Volf Abundance by Ezra Klein The Sabbath by Abraham HeschelLuke 18:9-14, Philippians 2, 1 Corinthians 12:21-26, Mark 10:35-45The Magnificat (Luke 1:46-55) Works of Love by Søren KierkegaardSubscribe to Amy Julia’s newsletter_

WATCH this conversation on YouTube by clicking here.

_

ABOUT:

Miroslav Volf (DrTheol, University of Tübingen) is the Henry B. Wright Professor of Theology at Yale Divinity School and founding director of the Yale Center for Faith and Culture in New Haven, Connecticut. He has written or edited more than two dozen books, including the New York Times bestseller Life Worth Living, A Public Faith, Public Faith in Action, and Exclusion and Embrace (winner of the Grawemeyer Award in Religion and selected as among the 100 best religious books of the 20th century by Christianity Today). Educated in his native Croatia, the United States, and Germany, Volf regularly lectures around the world. CONNECT with Miroslav Volf on X at @miroslavvolf.

Photo Credit: © Christopher Capozziello

___

Let’s stay in touch. Subscribe to my newsletter to receive weekly reflections that challenge assumptions about the good life, proclaim the inherent belovedness of every human being, and envision a world of belonging where everyone matters.

TRANSCRIPTNote: This transcript is autogenerated and does contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Amy Julia (00:05)

I’m Amy Julia Becker and this is Reimagining the Good Life, a podcast about challenging the assumptions about what makes life good, proclaiming the inherent belovedness of every human being, and envisioning

I saw the title of Mircea Wolff’s latest book, I immediately asked if he would come on the show. Usually I read a book before I invite an author, but in this case, that is not what happened. I did want him to join us simply based on who he is. He’s insightful, he’s thoughtful. I have followed his work for years. He has written multiple really important books. He’s also the founding director of the Yale Center for Faith and Culture, and I appreciate his story and his work.

But I was also struck very specifically by the title and the topic of this particular book, which is called The Cost of Ambition, How Striving to be Better than Others Makes Us Worse. I am really grateful for this book, for this conversation. It helps me to think about a different way of being in this world, a way that allows for greater collaboration and community and less competition and comparison.

a way that doesn’t denigrate achievement, but also doesn’t overvalue ability. It’s a way that invites us to live out of love, which is what I want to do, even if it’s not always how I am able to live. I hope you enjoy this conversation as much as I did. Well, I am sitting here today with Professor Mirzlof Wolff, and I’m so delighted to finally have you on the show. Thank you for being here.

Miroslav (01:47)

I’m delighted that I can be talking to you, Amy Julia. ⁓ We’ve known each other for a while and it’s the first time we’re talking in this format.

Amy Julia (01:58)

Exactly. And that’s why I’m particularly excited. But I also told you this when I saw the title of your new book, which I’m going to read here, The Cost of Ambition, How Striving to be Better than Others Makes Us Worse, I just thought, my gosh, I have to read that book. I need to talk about this book ⁓ personally, but also on this podcast. So I really am just personally excited to be having this conversation.

And I thought we might start with that idea of striving to be better than others, that in some ways is the shorthand for ambition, or maybe ambition is the shorthand for that. But either way, I’m curious if you could just speak to how we see ⁓ that all of us, more or less in American culture, are actually taught to be strivers, to be better than others. That’s something that’s kind of in the water that we swim in, so we might not see it very easily. ⁓ But it also is something I think you point out in the book is like,

pervasive and I thought we’d just start there. Like where do you see it? How does it manifest itself in our culture?

Miroslav (02:57)

Yeah, your comment, it’s like the water in which we swim and so we don’t see it is very true. ⁓ And I think it’s pervasive. ⁓ If one thinks about it in terms of ⁓ living in a competitive world, ⁓ then it immediately surfaces ⁓ and we see it ⁓ and that competition in which we are involved.

Is competition, then you ask yourself for what? And when you try to answer, what is the competition for? ⁓ I think competition is at least one of its important goals on which many other goals depend is to be better than others. When you apply for a job, there is a competition of this kind. When you are going through ⁓ educational processes, there is a competition.

of this sort. ⁓ And you can run through all the domains of politics, for instance, economics, sports, not to speak of that, because that ⁓ kind of defines the culture. And in some ways, a lot of people see then sports precisely in this domain to be ⁓ paradigmatic, kind of the image of the society as a whole.

Now I want to say people have always compared themselves and people have always striven to outdo one another. That’s not something new. But for many centuries there has been always a sense that there’s something not exactly quite right about it. There is a danger in this. There is a cost that’s being paid by doing this.

And it’s only in very recent centuries that we have, even centuries, plural, in recent century or so, from what I could tell, that has become that we just simply say, this is life. ⁓ And we don’t call that into question, virtually at all. ⁓ And do not see the dark side. And just one more brief comment, the dark side of it came very clear to me ⁓

when over the years that I was teaching, especially Yale undergrads, they graduate, they’re at the top of their class, they’re really bright ⁓ people, great achievers, they come to Yale and they’re one in 5,000 of the same people and suddenly they’ve built this image of themselves, who they are, as being on the top. And they come and they’re just your average…

person here at Yale and suddenly their self-image can plummet because the comparisons really never end. And in that sense, it seems to me that you can kind of have the, be a great achiever and yet internally see yourself as inferiorized, as somebody who isn’t quite

good enough who can’t embrace oneself and love oneself ⁓ because it depends on where I am. Status.

Amy Julia (06:24)

I want to like piece apart everything you just said and talk more about it. So ⁓ let’s start here. The you you as you mentioned, our professor at Yale University, I know you’ve worked in other spaces as well. ⁓ But that seems like it would be, although undergraduates might get there and have an experience of, my gosh, I’m just one among many. Then I would think that the striving for superiority starts all over again.

And then the same thing happens upon graduation. I would also imagine that that’s not an unusual experience as a faculty member at Yale to be looking for the award and to need to publish the paper that is considered better than the other person. ⁓ And I’m curious in terms of just your own experience personally and with students, how do you see the cost, not only for like your own self, but actually, and maybe you want to say more to that, but also in terms of the community.

Like what happens in a community that is continually striving to be better than each other?

Miroslav (07:27)

⁓ So the cost for oneself is a kind of self-loathing. ⁓ And self-loathing that’s detached actually from actual state in which one finds oneself. But you imagine then the self-loather, person who loads themselves. Socially, it’s very difficult to be ⁓ generous to others.

because you don’t have sufficient ⁓ capital, so to speak, of self-love in order to be able to ⁓ extend the hand ⁓ of friendship, to support others, to elevate others as is appropriate to rejoice in what others do, you in extreme cases become a kind of sociopath.

⁓ everything has to be nourishing your own sense of self or feeding your self-loathing so that it wouldn’t, or the right word is not feeding, but kind of ⁓ pushing away, ⁓ subduing the sense of self-loathing, and therefore you just draw everything into yourself. Those are extreme situations and we can…

see those extreme situations, recognize it in world of politics, we can recognize them in the world of sports, we can recognize it in many, many places. So that the toxic effects that it has on community is our terrible price to pay. We are hyper individualists. ⁓ Yeah.

Amy Julia (09:14)

So I’m, this is backing up a little bit within what you’re talking about. ⁓ This is from the book you write, in striving for superiority, the self is lost. And I think you’ve described some of how that happens, like that true sense of self. And then in the same section, you write about love as a different primary reference for our identities. And I wanted to ask you to speak a little bit about that. I guess, what is the reference for our identities if it’s not love? And then how do we…

make a move towards actually ⁓ love as the primary reference for identities.

Miroslav (09:51)

It seems like that we live as human beings well if we have this fundamental trust in reality and if we feel that we ourselves are affirmed in our being. Not so much affirmed in different things that we do and do well, but in there just being us in the world.

And in many ways that happens with every child that is wanted. When the child is born, there is this ⁓ incredible joy that simply says, without knowing how the child will develop, what will happen, that simply says, is good that you are and that you are here with us. And I think that’s a kind of sense that we see in…

I’ve come to think that we see it in the first book of the Bible, when God creates the world one thing after another, and there are very good things, one kind of thing after another, and there are very good things, and then at the end, God says, and look, it was very good. Now this and look, is His call, God’s calling us to take the perspective of God and affirm the creation as good. And now you might ask yourself,

It’s just been created. What is it good? In what sense is it good? Is it primarily functioning well? It hasn’t hardly functioned. Is it morally good? Well, I don’t know. ⁓ It hasn’t done anything yet, right? So moral goodness doesn’t necessarily apply. Is it aesthetically good? Yes, all three of them, right? But I think most fundamentally, it is good that it exists. And this is kind of existential kind

goodness that cannot be undermined by performance or enhanced by performance. And in that sense, ⁓ that’s how each one of us, I think, are loved by God. And out of this love ⁓ comes the space in which I can breathe and be myself without looking over my shoulder, without comparing myself with others necessarily. And I can just grow into the fullness.

Amy Julia (12:17)

I was talking with my son who’s a junior in high school and so he’s starting the college process and we were talking about if your identity comes from a source of love for exactly the way you just described it, although I didn’t say it as eloquently. then how does that change the way you apply to colleges? ⁓ And one of the things he said, because I was like, isn’t it freeing? Like you don’t have to get into X, Y or Z in order to be OK. He said it is freeing, but it’s also motivating.

because I can go for X, Y, and Z. And if I don’t get in, I’m still okay. But I can also, I just loved what you just said in terms of it both, kind of, yeah, it doesn’t put you below or above. Like there’s just a being you and a goodness to that that does not have to operate in this place of constant comparison because, and one of the things that comes out of striving is it really is never enough because I have to stay where I’ve,

I either have to get better from where I already am or I have to stay there, which is going to involve more and more striving to be better than others than, you know, and that at some point is going to exhaust itself. I mean, at some point that is not going to work anymore.

Miroslav (13:30)

Yeah, you must have been very eloquent because you’ve had the proper response from your son to the point that you were making. And I can only imagine that it wasn’t the first time you made that point and that you related to him in such a way so that he could articulate ⁓ in the crucial and critical time of his life ⁓ just that way of living, which is wonderful.

Amy Julia (13:56)

Well,

thank you. mean, I do think for us having and for him having a you he has a big sister who has Down syndrome. And so her she does not live a life of striving. I mean, period. Like, I mean, it’s actually this really beautiful ⁓ counter example for the rest of the family who are much more inclined towards the comparisons and the striving. And she is ⁓ much more ⁓ intuitively.

able to both accept herself and others as they are. ⁓ And I think all of us have really been ⁓ almost invited into a different way of being as a result of that. And I’m very grateful for that. And I guess that kind of gets me to my next question, which is I’m thinking about how a culture of striving for superiority, a culture of ambitions and competition,

how it might deform our understanding of humanity more broadly, just the way, and this is again, kind of an existential question, but the way it deforms our understanding of ourselves, but also of others.

Miroslav (14:59)

Yeah, in many ways it… I mean, you mentioned earlier that you said never enough. And in many ways it makes us kind of never enough people. ⁓ I personally don’t have anything against striving, striving toward a good goal.

⁓ I think we are invited into this, even when we speak in Christian terms about sanctification, in greater Christ-likeness. It’s more that we are invited not to necessarily compare ourselves with others and judge our achievements in comparative terms. But I think…

is if one doesn’t, it goes away from the comparisons, one can then see that at certain point things can be enough of certain things. I don’t have in everything that I do, somehow be better than others to feel okay about myself. And this being enough and having enough,

We have been partly through striving for superiority, but partly also through advertising, which is in some ways also feeding onto our sense of inferiority and superiority. We have been conditioned to think, and we can have accepted that conditioning to think that if somebody has something better than I have, I’ve got to get that at least as good or if not better. And so we don’t know.

what it means to long for what we have. It’s very interesting passage. I’m using it in my Gifford ⁓ lectures from Dante’s ⁓ Divine Comedy in the Paradiso. The souls who are fairly low in the ranks of heaven ⁓ early on.

Dante comes to them and then he asks the question, ⁓ how can you be satisfied where you are? Aren’t you unhappy? Because when you compare yourself, you can kind of imagine and that’s the question I remember asking myself early on, how come these people are, everybody can be happy but they have all different crowns and different jewels in the crowns because, and so forth when I was growing up. But the answer of the souls is very interesting.

They say, we long for what we have.

Amy Julia (17:45)

That is so interesting. And I’m just thinking to your point about so there’s like this kind of innate human ⁓ sense, as you said, that’s always been there of striving for superiority. And we can see that in ancient literature and we can see it in the Bible and we can see it in, you know, Renaissance literature. But there’s also this conditioning that is particular to the past, you the modern era, the past hundred years, whatever it is.

that comes at us and tells us, and that’s how you’re supposed to be. ⁓ And that’s very different from longing for what we have. I would love to hear your thoughts on this. I’ve been thinking a little bit about ⁓ like a scarcity mindset versus an abundance mindset, right? And so I’ve heard about that actually in the political realm right now. Ezra Klein has this new book, Abundance, about how we need to have a political imagination shaped by abundance. I’ve for a long time heard about…

God from a theological perspective as a God of abundance. You described Genesis one and it was very good. And there’s this teeming world of beauty and abundance. But I’ve also been thinking about the difference between abundance and excess and how when we are, I think excess is what we are striving for, like for having more than we actually need. And within this idea that somebody else is not like it, there’s a zero sum game, right? ⁓

There’s not going to be enough for all of us. So I better work really hard to have more than I need to have excess because there’s not abundance and there is scarcity. And so I just wonder how much that longing for what I have, that sense of like contentment, some measure of like a simplicity. ⁓ And as you were saying, like an ability to both have compassion and celebration in our lives rather than comparison where I can celebrate the

triumphs of other people or the really good things they’re doing. I can have compassion when things aren’t going particularly well rather than this judgment of I’m higher or lower on a ladder than you are.

Miroslav (19:46)

Yeah, I think that’s exactly right. You put it really well. ⁓ What seems to me also to be the case, and that example of the souls in Paradiso seems to suggest, it’s not simply the question of things out there that we either have or not. It is also…

and in many ways, maybe primarily, a matter of how I relate to what I have. What does that symbolize for me? What does that do to my self-image and how I situate myself in context of other people? And I think there is a really important place where we can nurture the spirituality of appreciation.

of that which is, and not simply almost, it’s almost like a flight away from what is into what isn’t yet. And we think it would be better. A sense that I can appreciate what it is, celebrate what it is. I think that that’s also one of the purposes for celebrating Sabbath, Sabbath command.

And one of my favorite books on Sabbath, you will probably know it and you’re listeners, ⁓ Abraham Heschel’s Sabbath, the book Sabbath, which is a kind of ⁓ ode to Sabbath. And he has this example of a rabbi who goes into his garden and it’s now on the Sabbath and he’s praising God for all the goods. And then suddenly he sees there that his fence is torn.

⁓ And then he starts thinking, well, I’ve got to know. As soon as Sabbath is over, I’m going to get and repair that fence, right? And so there is this immediately shift into the mode from appreciation to tasks that I have to accomplish and not having enough time to sit with the beauty of what is, even if the fence is torn. And so my sense ⁓ is.

that we need to rediscover ⁓ the two are not really alternatives, exclusive alternatives, both improving without comparison necessarily with others ⁓ and also being satisfied with celebrating what is and this movement of the two seems to me really essential. And when it comes from within, when I’m satisfied from within,

when I’m moving from within to achieve something better, it seems to me that we live a much healthier life.

Amy Julia (22:39)

Yeah, you write about the difference between striving for superiority and striving for excellence. And I wondered if you could say a little bit more about that difference and whether there’s ever a problem embedded within striving for excellence. I think we’ve talked about the problem within striving for superiority, but ⁓ or whether that is kind of in and of itself a good and natural aspect of our humanity.

Miroslav (23:05)

I personally would say that striving for excellence, ⁓ if the goods in which you want to be excellent are themselves excellent, one can strive for excellence in all sorts of things, right? In the wrong ways. But if the goals are correct and if in the process of striving for excellence we can attend to multiple…

other relationships that we have not just to ourselves and to that goal, but to other aspects of our lives, then striving for excellence, I think, is a very good thing. ⁓ striving for superiority is in some situations precisely striving for excellence in comparison with others. And so if one thinks about ⁓

the prayer in the Gospel of ⁓ Luke, of that Pharisee and ⁓ the tax collector. And presumably what the Pharisee is saying ⁓ is true before God, he keeps the commandment, he’s upright, a good person. But what’s bad about it is not that he has striven to become such an excellent specimen of a devout ⁓ Jew.

which is great. What’s bad is that that served for him as a comparative judgment to put somebody else down.

Amy Julia (24:42)

Yeah, and it’s to your point earlier that if he were tomorrow to not be so great at what he was doing, it would also be the beginning of, or perhaps the continuation of that sense of self-loathing. It’s an identity builder on my behavior in comparison to others, but also as a way of proving myself as good enough rather than receiving that and from there living a life of gratitude and

⁓ Yeah, compassion and being able to again strive for excellence without excellence being a marker of my worthiness.

Miroslav (25:24)

Yeah, and in a sense, this is a very important point that you’re making, and that has to do with the question of genuine merit. Because there a lot of people that have genuine merit, but the problem then becomes when they ascribe the entirety of their merit to themselves. There is not only something, you know, comparative,

seeking ⁓ my own identity and to elevate myself at the expense of another. But there’s also that that kind of ascription of merit to myself is generally about 99 % a lie. In the sense that if I ⁓ think of myself, I’m a professor at Yale, if you ask me, genuinely close your eyes, think, and tell me what percentage.

of the achievement that that, let’s say, represents should be ascribed to you, Miroslav. And I would say, whoa!

⁓ 2 %?

Amy Julia (26:41)

One? Yeah.

Miroslav (26:42)

And then I wouldn’t know how to draw the line where my contribution and others’ contributions come. ⁓ And so it seems to me that this kind of comparative judgements are just… They’re existential lies that we tell ourselves to bolster our identity. I think Paul was saying…

Something like that when in 1 Corinthians, he talks to the Corinthians who had this sense that they wanted to have a God of power, a God of resurrection, and he asks the question, what do you have that you haven’t received? ⁓ And then doesn’t wait for the answer, because he assumes that they will answer in the way in which it’s proper to answer. Not much. Because the next question he asked…

If you have received everything, why do you boast?

And that seems to me that every time I talk about my merit and I kind of feel good about myself in my merit, I am kind of boasting. ⁓ Sometimes I have audience of one, it’s myself, but sometimes implicitly I have a broader audience as well. So there is a kind of boasting that occurs that I believe is really a lie. In that sense, this is that there’s a falsity.

of our lives of this sort. And it has tremendous negative influence also on others.

Amy Julia (28:24)

So one of the things kind of picking up on what you were just saying that I was really struck by and really appreciated in the book is that ⁓ speaking about this from like a particularly Christian perspective, you bring up a passage in Philippians where Paul writes, we’re meant to consider others better than ourselves. And it can seem like what that leads to is a new status hierarchy where we put ourselves on the bottom and others on top.

⁓ And that, in my mind, especially if I think through, particularly over the course of history, maybe less so in this current moment, but for example, the roles of women or other people who have been seen as like in more service oriented professions or status places, there’s been the sense of like, yeah, consider others better than yourselves, keep serving, right? So there’s that element of things and almost like a self denigration that

It doesn’t seem to line up with what we were talking about as far as an identity that is rooted in the common belovedness and the gifted, the gift that we receive from being. So I wanted to ask you just to explain your take on that idea of what Paul’s really getting at when he says consider others better than ourselves and so much language around mutuality and submitting to one another, for example, would be another place where that comes up. So could you just speak to that a little bit?

Miroslav (29:49)

Yeah, I think to me the interesting ⁓ aspect of this ⁓ command that the Apostle Paul issues. By the way, I don’t think it’s translated as consider others better than yourself. I think the better translation is relate to others as if they were more important than you. Now, the larger point that you are making still holds, right?

But it’s important because if you consider somebody better than you, it seems like often it’s a lie. There aren’t better. I’m better. So this is not a point of, ⁓ okay, I’m going to tell a lie about my abilities and consider somebody better than I am in something. But back to your point, it seems to me that it’s important that it is a general command.

where it becomes problematic is if you apply it to particular groups of people, whether in ancient world to the slaves, whether in ⁓ much contemporary world to servants, to women. And so you categorize people who should consider other people to be important than themselves, and then others who should not, who should be feeling more important than they are, right?

And that runs completely counter the passage as a whole. And then you’ve got the prime example of who does that is the one who de facto was the most important of all. Which is to say Jesus who did not graspingly hold onto equality with God but served. So it seems to me that that’s a, it really is an invitation

especially to those who are on the top, to serve those who seem to be less important than they. And when you look at how Paul applies this, ⁓ he applies it in 1 Corinthians 12, when he talks about the body and different members. And then there are these unseemly members who have to be shown particular kind of honor, and then he says, so that there would be equality.

So my reading of that passage is that in Philippians, is that actually the aim is at equality and not in stabilizing kind of hierarchies of service or then making simply ⁓ service to be the badge of honor.

⁓ because Christ doesn’t end up simply being crucified, he ends up being resurrected. And so I think the entire journey of Christ from equality with God to the shameful death, to resurrection, is the story of one who considers others to be more important than he is himself. And it aims to establish pattern for behavior of each of us and therefore to help.

⁓ other people and helping our relationship to other people to be suffused by love, in fact.

Amy Julia (33:15)

I spent a lot of time in recent years, I guess, during the Christmas season, thinking about Mary’s song, The Magnificat, in which she’s talking about both the lowly being lifted up and the rulers being brought down from their thrones. And that, to me, was actually really helpful in this idea of, wait a second, she’s not actually saying everyone should be seeing themselves as lower than someone else, but actually that

God wants to lift the lowly up and it made me think about the ways in which and I think you get to this in the book as well This is not a reversal of power It is not now we just have a power inversion and there’s always a subjugated class and an elevated class It’s actually a new way of understanding where status is actually not a marker. It’s not a thing And the way of jesus actually is talking about a new reality in which everyone is lifted up

in which everyone has an experience of in themselves and in each other goodness and belovedness that allows us to have these relationships of mutual giving and receiving. ⁓ And so I appreciated just the way that your work, I guess kind of ⁓ underscored, also like brought me farther in my own thinking.

about those things and what that looks like. And one of the places in particular, towards the end of the book, you were writing about James and John when they say to Jesus, can we sit at your right and left hand? basically, will you lift us up? And he’s like, I don’t think you’re ready to do that. And in part of what you were describing there, what it made me think about was this idea of servant leadership and how I, in the past, have thought about, like I’ve been a little confused about the idea of servant leadership because I’m like, wait,

are leaders really supposed to just like go and do, let’s call it like janitorial work because it seems like no, they’re supposed to be leading the company. Like they’re supposed to end. And so, but I think what you were saying, and I’d love for you to speak a little bit to this, is that what it looks like to not put yourself in this kind of striving and hierarchical position, even when you are a leader, is to be leading in such a way that it is in service of others. It is for the sake of others.

out of a place of love for others. ⁓ But yeah, could you speak a little bit about that idea? I mean, you don’t use the words servant leadership, but that’s what I’m kind of wondering about.

Miroslav (35:43)

But there are positions of leadership and those positions of leadership need not be given up ⁓ if one is to obey this command to treat others as if they were more important than yourself. ⁓ And it seems to me that it’s precisely what it does is a servant, a leader is there to serve ⁓

not just individual person, but the entire community that the leader ⁓ leads. And to put the ⁓ good of the entirety of the company ahead of their own particular good ⁓ and how they experience it. And I think the best leaders are just such leaders. And by this, they don’t become emptied of themselves,

⁓ of almost like shells from which the self has ⁓ departed, but in fact come into their own as leaders and as a sturdy and strong selves. And I think it’s a kind of lie. The lie I think that is understandable because ⁓ people often oscillate between the alternative. Either I kind of either I suppress you and

assert myself ⁓ or I completely disappear and let you be. There’s a kind of competitive relationship that has been established. What seems to me clear ⁓ is that, and often not emphasized enough, that we should, each of us, should love ourselves with the same love with which God loves us, with agapic love.

not on the basis of our performance, but on the basis of fact that we simply are. And Kierkegaard has this wonderful ⁓ line in his great book, Works of Love, that he says, you should love yourself with the same love which you’re commanded to love your neighbor, with the same kind of love with which you’re commanded to love your neighbor. That is to say,

we belong to the community and we are to the beloved community, which is to say each one of us ought to be loved by each other and each one of us ought to love ourselves as we love others.

Amy Julia (38:25)

So how do we do that? Like, does all of this actually look like in the world of striving for superiority that is both coming at us from the inside and the outside? Do you have any thoughts on just the, ⁓ whether it’s spiritual practices or habits or ⁓ ways of thinking or being in the world that allow us both to understand and kind of claim that identity in love and also to operate in the world not

in this less competitive, hierarchical, status-seeking way.

Miroslav (39:00)

Yeah, it’s a great question. I think I need to write another book, which would be spirituality. I’m not sure I’m capable of writing one like that. ⁓ Sometimes when I ask questions like that, how does one do it? And I say, well, I’m a systematic theologian. I’m not practical theologian. I’m impractical theologian.

So I don’t think I can give you a kind of five points how one does that, but it seems to me that for the first and for myself what was important is to be aware when I see somebody who is pointing away from themselves and rejoicing in the successes of others who nurtures.

⁓ others in a way that isn’t so deprecating themselves, but that is genuinely delighting in the successes of other people and how incredibly ⁓ elevating to me, at least that feels. So there is something that responds well in us to ⁓ seeing generosity at work. ⁓

When we observe that, seems I always ask the Lord help me to be ⁓ this kind of a person, which then requires certain kind of interior work so that ⁓ I can quiet this voice which always craves attention to oneself, which always craves for me to be first or whatever that might be. ⁓

And it seems that it is ⁓ a process. Some of us have an easier job doing that. I think that some of us are more generous characters to begin with than others. And ⁓ it requires kind of spiritual growth that we need to ⁓ undergo. I think the best ⁓ to me is follow the examples. ⁓

And for me, example is of course Jesus Christ. And they’re kind of a verse examples. Look at the ugliness of a person who might be brilliant and cannot stop boasting about their brilliance. In the world of sports, Michael Jordan was known for just doing that.

You compare him with some other ⁓ athletes who were equally brilliant in their own ways, always ⁓ friendly to those who were less successful, always not talking about themselves, but talking about others. And we see it in all domains of life.

Amy Julia (42:09)

I’ve been more and more struck in reading the gospels in recent years at how much, just back to your look at Jesus and his example, how much he is talking about the status systems of the world and saying, is not the way God ⁓ does it. It’s just not the way it works. This is a quotation from the book. Jesus tells them that a key part of his mission is to establish an alternative social order in which those with power and wealth.

do not rule over the weak and the poor, but all serve each other. And it’s hard for us to even imagine that happening. I think that goes back to your image of Dante’s souls who are longing for what they already have ⁓ and trying to, yeah, understand. And I guess that’s something that we don’t ask others to do in the same way as we might ask of ourselves. Just the sense of, if I can start to long for what I have, to live in that place of appreciation.

⁓ There’s a degree of humility that’s going to come in there, but also a degree of ⁓ not humility that’s coming from humiliation, but actually from that place of appreciation and recognizing ⁓ of the gift.

Miroslav (43:18)

And the kind of, especially in a close relationship, a relationship to children, to one’s spouse, to one’s friends, how much damage actually one does when one does not appreciate what one has. When one doesn’t appreciate a child one has, but always wants to have a different child than that child is, to be different than that child is. ⁓ That’s not against raising.

the children, but that’s against this sense of appreciating of who they are and working with that beautiful thing that they are. And that applies across ⁓ all domains. And if we don’t do that, we are lousy teachers, are lousy bosses, we are lousy parents. And it just does not add up to the good and rich life that we can have.

Amy Julia (44:15)

One of the early things you write, this is in like the preface or something to the book is striving for superiority is a dominant theme in the story of human suffering and wrongdoing. And I think that’s kind of the inverse or related to what you just said that there’s actually a, yeah, an insidious nature to striving for superiority, both within ourselves and within the relationships we have. You gave such a great one as far as family.

And the same would be true in any of our relationships when we want other people to be not who they are. And we’re always wanting them to be better rather than receiving them for who they are, which actually frees them up to ⁓ pursue excellence or to pursue the good. I thought I’d maybe ask as a final question, though, on the flip side of that. if, you know, striving for superiority is a dominant theme in the story of human suffering. Well, what happens if we

stop striving for superiority? What does the human story look like when we reimagine a social order and act and think and see the world this way? What are some of the goods that come from that?

Miroslav (45:28)

Well, Cain then hasn’t killed his brother Abel. I haven’t then lifted myself and make another person feel bad about themselves. I’m not boasting. I’m not deriving my identity from any of the…

achievements that can be overtaken at any point. I don’t have a fragile identity that at any moment can crumble and then has to raise from the dead in order to claw itself up higher than somebody else to be somebody and then fear for that position that one has.

I can breathe the fresh air freely and be who I am. I mean, it’s amazing. It’s almost we live in a paradise when we give up on striving for superiority. That seems maybe too much to say. There are other elements, of course, of what would need to be there for it to be a paradise. But in many situations, we will experience

genuine abundance of the goods, which we are blind and do not see because what’s valuable to us is only that which serves to give me comparative advantage. We are garbageing the world by using it simply as a means of shoring up our fragile self.

Amy Julia (47:23)

⁓ I love the just very particular examples you gave and the different images and stories that come to mind, again, that are so countercultural and yet there’s almost like a sense of peace in just naming the idea of not boasting of, yeah, living with contentment and gratitude and real celebration for…

the goods, whether they’re in my life or in others. So I love that. It’s such a beautiful picture. And I think this book is a part of it’s a contribution towards perhaps some culture change in that area. And at least ⁓ I think about often the idea of a sign where, ⁓ you know, we might not be establishing exactly the kingdom that Jesus talked about in some the fullness of it, but we can point towards it in the way that we live our lives. And

how freeing it is not just for us but those around us if we can live in a way that is not about making ourselves superior but is actually about lifting everyone up.

Miroslav (48:29)

You’ve said it so well.

Amy Julia (48:30)

Well, you’ve said it so well and I’m really grateful for it. Thank you for your time here, but also for this beautiful book.

Miroslav (48:38)

Good to talk to you. You too.

Amy Julia (48:44)

Thanks as always for listening to this episode of Reimagining the Good Life. We have one more episode this season with my friend Heather Avis, so that will come to you in two weeks. So at this moment, I wanted to take this opportunity to invite you to become a subscriber, yes, to this podcast, so you know when a new season ⁓ begins to drop, but also to my newsletter. So the newsletter reports on the podcast when it’s happening.

but it also gives a weekly email from me with some thoughts on topics related to reimagining the good life. I also offer book and movie and show and podcast recommendations there on a weekly basis. You’ll see some photos and get some news and insights. If you are interested in becoming a subscriber, you can go to the show notes and click the link or go to my website, amyjuliabecker.com in order to sign up.

As we do start thinking ahead to the next season of the podcast, I would love to hear your thoughts, questions, suggestions. My email is amyjuliabeckerwriter at gmail.com. I also, I always say this, but I mean it every time. We appreciate it when you share this conversation with others and when you rate or review this podcast. It allows more people just to know that these, ⁓ yeah, thoughtful and…

⁓ deep and hopefully meaningful and encouraging conversations are out in the world. I want to end by thanking Jake Hansen for editing this podcast and Amber Beery, my social media coordinator, for doing everything else to make sure that it happens. I hope this conversation helps you to challenge assumptions, proclaim belovedness, and envision a world of belonging where everyone matters. Let’s reimagine the good life together.

SUBSCRIBE TO PODCAST

[image error]Apple Podcasts[image error]Spotify[image error]CastBox More!

More!

Learn more with Amy Julia:

To Be Made Well: An Invitation to Wholeness, Healing, and Hope S7 E18 | Exploring the Good Life with Meghan Sullivan, Ph.D.S8 E14 | Want to Change Culture? Show Up With Care with Andy CrouchLet’s stay in touch. Subscribe to my newsletter to receive weekly reflections that challenge assumptions about the good life, proclaim the inherent belovedness of every human being, and envision a world of belonging where everyone matters. Follow me on Facebook , Instagram , and YouTube and subscribe to my Reimagining the Good Life podcast for conversations with guests centered around disability, faith, and culture.

The post S8 E19 | The Cost of Ambition with Miroslav Volf, PhD appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

May 28, 2025

It’s Good to Have Fun!

As some of you know, my husband is the Head of School at a boarding school in Connecticut. Last week, we joined the senior class at a local amusement park. I was reminded of two things. One, that my body can’t handle things like swings or freefalls anymore. And two, that there’s such goodness in experiencing fun stuff together. I did make it onto the tamest of rides.

The post It’s Good to Have Fun! appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

May 27, 2025

How We Spend Our Money as a Nation Says A Lot

“Your checkbook is a spiritual document,” the priest said. Peter and I were young and newlywed. We had been invited to a fundraiser for our local church. It was long enough ago that most people did most of their financial transactions through paper checks. And the speaker that night wanted us to understand that where we put our money tells us something about the state of our souls.

I’ve returned to his simple words over the years as a helpful statement of spiritual reality. What does my purchase of a new dress, or our decision to pay for a trip to Disney World tell me about who I am and what I believe? What does our commitment to giving money to charitable causes or to people in need signify? When is it good to spend, save, and give money away? What do those decisions reflect about who we are and who we are becoming?

It’s a question we might want to ask collectively right now, as the One Big, Beautiful Bill Act makes its way through Congress. I had a chance to write about the implications of this bill on families affected by disability, and the way we as a nation choose to spend, or restrict spending for Cognoscenti this week:

I am losing my confidence that each year is a better year for people like our daughter.

Since Trump’s return to the White House in January, the Social Security Administration has ceased funding the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium, which was instrumental in fostering “research, communication and education on matters relating to disability policy.” Reduced funding for research at the National Institutes of Health disproportionately affects disabled people. The proposed reorganization of the Department of Education and the Department of Health and Human Services puts the rights of disabled students in jeopardy. Early drafts of the bill under consideration show that the Trump administration wants to eliminate funding for state councils of developmental disabilities, lifespan respite programs and advocacy organizations, among other programs.

I’m disheartened by the choices we are on track to make as a nation when it comes to funding care for our most vulnerable members. I’m also aware that money does not buy happiness or connection. Only love—manifested in embodied care for one another—can do that.

Read the full essay here: For people with disabilities: Kindness is nice. Legal protections are necessaryLet’s stay in touch. Subscribe to my newsletter to receive weekly reflections that challenge assumptions about the good life, proclaim the inherent belovedness of every human being, and envision a world of belonging where everyone matters. Follow me on Facebook , Instagram , and YouTube and subscribe to my Reimagining the Good Life podcast for conversations with guests centered around disability, faith, and culture.

The post How We Spend Our Money as a Nation Says A Lot appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

COGNOSCENTI | For people with disabilities: Kindness is nice. Legal protections are necessary

Grateful to write today for Cognoscenti/WBUR, Boston’s NPR station (read the full essay here): President Trump’s domestic policy agenda, backed by Republicans, jeopardizes protections, research and support for people with disabilities, writes Amy Julia Becker.

…as the Republican-led Congress moves to pass President Trump’s domestic agenda in the so-called One Big Beautiful Bill Act, I am losing my confidence that each year is a better year for people like our daughter…

Throughout our experience as parents, we have needed individuals who believed in Penny, cared for her and supported her and us. But goodwill and kindness are not enough. We also need the government to protect her right to learn in the “least restrictive environment.” We need the government to support research, to provide job training opportunities and to protect her against discrimination. The policy changes pursued by the Trump administration put those rights and services in jeopardy in our schools, workplaces and social support systems…

Keep Reading: For people with disabilities: Kindness is nice. Legal protections are necessary

MORE WITH AMY JULIA:

Free Resource: From Exclusion to Belonging(a free guide to help you identify and create spaces of belonging and welcome)S8 E6 | A Life Worth Living? Reimagining Life, Choice, and Disability with Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, Ph.D.S8 E10 | The Myth of a Colorblind, Meritocratic Society with David M. Bailey

Let’s stay in touch. Subscribe to my newsletter to receive weekly reflections that challenge assumptions about the good life, proclaim the inherent belovedness of every human being, and envision a world of belonging where everyone matters. Follow me on Facebook , Instagram , and YouTube and subscribe to my Reimagining the Good Life podcast for conversations with guests centered around disability, faith, and culture.

The post COGNOSCENTI | For people with disabilities: Kindness is nice. Legal protections are necessary appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

May 23, 2025

Delivered Into Rest: From Pharaoh to Peace

What happens when our identities emerge from resting in the love of God rather than obeying the demands of our cultural gods? Walter Brueggemann writes at the end of his book, Delivered Into Covenant, that the book of Exodus is all about Sabbath rest. It’s about how the Israelites couldn’t receive rest until they were outside Pharaoh’s dominion. And about how the invitation to rest in the love of God moves us into a new way of being. According to Brueggemann, the way of Pharaoh is a way of anxiety, acquisitiveness, and relentless productivity. The Israelites can never make enough bricks. They can never satisfy the demands on them. They can never feel secure. And Pharaoh will never have enough.

In contrast, the way of YHWH is a way of peace, abundance, and creativity. Themes from the Genesis story of creation run through the book of Exodus, and run in contrast to the self-destructive way of Pharaoh. (The plagues, for instance, are often seen as a sign of decreation, an undoing of God’s good work.)

When we rest in the love of God, we receive the peace of knowing that we don’t have to prove ourselves in order to belong. We live in abundance, where there is enough time, enough money, enough food, enough care for all. This peace and abundance doesn’t leave us lazy or without purpose. Rather, this way gives us a different motivation for our work. Rather than working as creatures striving to produce, we work as image-bearers who reflect the goodness of God.

Let’s stay in touch. Subscribe to my newsletter to receive weekly reflections that challenge assumptions about the good life, proclaim the inherent belovedness of every human being, and envision a world of belonging where everyone matters. Follow me on Facebook , Instagram , and YouTube and subscribe to my Reimagining the Good Life podcast for conversations with guests centered around disability, faith, and culture.

The post Delivered Into Rest: From Pharaoh to Peace appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

May 22, 2025

How to Find Freedom From the Myth We Keep Chasing

If your family is anything like mine, you have some area in your house where holiday cards accumulate until we decide it is time to recycle them, or, as happened this year, our daughter Penny decides to take them all up to her room and look through a few each day for the rest of the year.

We love these little snapshots of families and friends from around the country and around the world, but I’m also always aware that these cards don’t tell even the beginning of the whole story. And I wonder how much those cards, and the images we see daily on Instagram and Facebook, contribute to a misunderstanding of American family life. I wonder how much they create a shiny, happy ideal that doesn’t reflect how most of us actually experience family.

I invited author and theologian (PhD, University of Dayton) to join me on the podcast to examine the question:

What if the perfect family doesn’t exist—and what if it never was supposed to?

LISTEN OR WATCH:

Apple

|

Spotify

|

Spotify

|

YouTube

|

YouTube

We explore:

the idealized version of the American familythe misconceptions surrounding a biblical blueprint for familycreating a home centered on love, not expectationsapprenticing ourselves to love through daily household practicesHere are a few practical insights that Emily offers households (and it’s helpful to note that households in her definition “are not limited to just the biological nuclear family… [They] can be multigenerational households of married and single, with or without children).”

1. Let go of the “ideal” family myth.The “ideal” American family is a recent cultural model. It’s not a biblical blueprint for blessing or a promise of happiness.

An invitation: Resist measuring your home against a TV-script ideal. Instead, name and celebrate the actual gifts of your household.

2. Jesus redefines what a full life looks like.Jesus—unmarried, childless, without property—did not embody the typical vision of “success” in his day (or ours). Emily points out:

“He demonstrates that the fullness of human life doesn’t actually require all of the things that we tend to occupy most of our time, attention, and effort with, especially in the American culture.”

An invitation: Reflect on the ways your household might be called to embody love and hospitality outside conventional milestones.

3. Homes are for love, not status.Home is not just where we live. It’s where we become “apprentices to love,” compassion, and radical hospitality. Love is formed not in competitions for superiority but in the mundane, like cereal bowls, laundry piles, and sibling squabbles.

An invitation: Shift family goals from perfection and appearance to formation and faithfulness. What practices help your household grow in love?

4. Subversion is part of the household calling.Families are called not to blend in but to quietly subvert the surrounding culture by living differently—prioritizing love, presence, and community over hurry, consumption, and constant productivity. Subversion doesn’t have to be loud. It can look like lingering around a dinner table, choosing connection over convenience. When our homes become places of peace, they quietly challenge the chaos outside.

An invitation: Set aside a block of time to go screen-free and obligation-free, where your household can intentionally slow down and embody a different set of values. Take a walk, read, nap, or be together without doing or buying. Even a few hours of rest or connection can push back against the dominant narratives.

I hope you’ll listen (or watch), and then share this episode with a friend. And I want to hear from you. Have you ever felt tempted to measure your life against the myth of the perfect American family? What has helped you break free from that myth? Leave a comment! I read every reflection from you. Also, Emily’s book, Households of Faith, is encouraging, thoughtful, and practical. Check it out!

Let’s stay in touch. Subscribe to my newsletter to receive weekly reflections that challenge assumptions about the good life, proclaim the inherent belovedness of every human being, and envision a world of belonging where everyone matters. Follow me on Facebook , Instagram , and YouTube and subscribe to my Reimagining the Good Life podcast for conversations with guests centered around disability, faith, and culture.

The post How to Find Freedom From the Myth We Keep Chasing appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

Penny Told Me I Could Share This

Penny has given me permission to tell you that she has a boyfriend! And I finally got to see a picture of him. They go to school together, so I haven’t met him in person, but I do know they are good friends who have fun conversations, enjoy playing Uno, and do not share the same taste in music, although she tells me she has gotten him into Taylor Swift.

It has also been really sweet to watch Penny grow up in this area. She had a boyfriend in high school, and without getting into details, it was a bit dramatic. She was really careful in assessing this relationship and talked about how she wanted to date him but she didn’t want to hurt him or hurt their friendship. She’s been great about setting good boundaries and asking for help from trusted adults in navigating some ups and downs. I still can’t believe I’m getting photos texted to me from my daughter with her BOYFRIEND, but I can say I’m grateful that she’s growing up with thoughtfulness and kindness.

Shared as always with Penny’s permission

Let’s stay in touch. Subscribe to my newsletter to receive weekly reflections that challenge assumptions about the good life, proclaim the inherent belovedness of every human being, and envision a world of belonging where everyone matters. Follow me on Facebook , Instagram , and YouTube and subscribe to my Reimagining the Good Life podcast for conversations with guests centered around disability, faith, and culture.

The post Penny Told Me I Could Share This appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

May 16, 2025

Having a Disabled Child Doesn’t Doom a Marriage

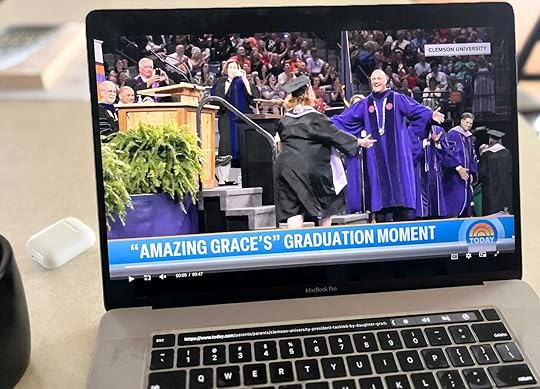

I watched the viral video of Grace Clements embracing her dad, the President of Clemson University. They tumble onto the stage together and get up for a more subdued, though still exuberant, hug, on the day marking Grace’s graduation from the ClemsonLIFE program. (Penny’s dream is to attend the ClemsonLIFE program, just like Grace.)

I also watched Grace and her parents on the Today Show, and I heard Beth Clements say that “80% of parents of kids with special needs get a divorce.”

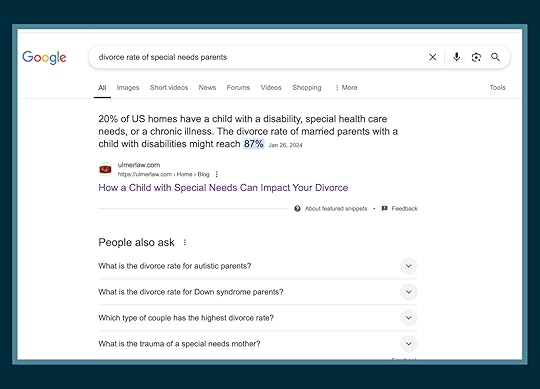

When I Googled “divorce rate of special needs parents,” the top result reads:

“20% of US homes have a child with a disability, special health care needs, or a chronic illness. The divorce rate of married parents with a child with disabilities might reach 87%”

Marriage and parenting kids with disabilities can be challenging. That’s true. And yet a deeper dive into the literature reveals a far more complex, and far more positive, story. (If you’re reading this and currently facing a difficult challenge, please know that you’re not alone. This essay isn’t about offering specific solutions to your situation, but I do want to gently encourage you to reach out for support and ask for help where you are.)

The 80% number seems to emerge from a 2023 article in Psychology Today that links to a Special Needs Law essay that references a documentary film about autism. In other words, the source of this information is quite unclear, and it originates only as a comment about families with kids with autism.

More Hopeful DataA 2015 study by the National Institutes of Health reached very different conclusions about the stability of marriages in families affected by disability, including autism. This study tracked nearly 200 families (compared to a control group of 7,200 families with typically-developing kids) over 50 years. Here’s what they report:

A 2004 meta-analysis of 13 different studies about divorce saw only a slight difference in marriage survival between families with kids with disabilities and families with typically developing kidsA 2007 study found a significantly LOWER rate of divorce among parents of children with Down syndrome than the general populationA 2010 study found that the rate of divorce of parents with autistic children is comparable to the general population, but there is a higher rate of divorce during the adolescent yearsFamilies with more children who include a child with a disability seem to have a lower rate of divorce than smaller families who include a disabled childThe researchers write:

The Importance of the Stories We Tell“In conclusion, we found that divorce rates were not elevated, on average, in families with a child with developmental disabilities.”

I can’t say for sure why the 80% statistic gets thrown about so often. Maybe it’s simply because of what comes up on a Google search. Maybe it’s because 80% feels so dramatic, and we tend to focus on, remember, and pass along dramatic data. Maybe it’s because well-meaning people want to send out a warning so that parents don’t forget to take care of their own needs, including the need to stay connected to and supportive of each other. Maybe it’s because we as a culture tell a story of disability as a tragedy and a burden, and this statistic supports that story.

I’ve said it before, and you’ll hear it from me again: we need to tell a new—and true and accurate—story about disability. We need to reimagine disability. And those of us in families affected by disability need to tell stories like that of Grace Clements and her family, stories of hope and resilience and limitations and possibilities and hardship and growth.

An Imagination for a Good Life 2024 | Photo by Cloe Poisson

2024 | Photo by Cloe PoissonFor nearly two decades, I’ve also been telling the story of our family in public, not in order to hold us up as exemplars, but in order to help shape an imagination for a good life for families affected by disability. Yes, there are hardships associated with the particularities of our family life, and I’m unlikely to share most of those here out of respect for our teenagers’ privacy. But there is also a lot of joy.

Recently, I was taking a walk with William, our 16-year-old son and Penny’s younger brother. I asked him if he ever felt like he needed support in light of having a sister with Down syndrome. “No, Mom,” he said. “If anything, I see it as a positive aspect of my life.”

I asked Marilee, our 14-year-old, the same question. She said, “I don’t really feel like it’s affected me that Penny has Down syndrome. I mean, maybe it makes me more empathetic to people who are excluded.”

Our family is just one example of the reality of marriage and parenting with a disabled child. We are among those who experience gratitude, strength, and growth here. And we are not alone.

If you are in a marriage with a child with disabilities, please know that your marriage can grow and thrive. Your kids can grow up in mutually beneficial relationships of love with one another. Your family can be a blessing to your community.

Let’s stay in touch. Subscribe to my newsletter to receive weekly reflections that challenge assumptions about the good life, proclaim the inherent belovedness of every human being, and envision a world of belonging where everyone matters. Follow me on Facebook , Instagram , and YouTube and subscribe to my Reimagining the Good Life podcast for conversations with guests centered around disability, faith, and culture.

The post Having a Disabled Child Doesn’t Doom a Marriage appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

May 9, 2025

May 2025 Favorites

Favorite books, essays, podcasts episodes, and more that I enjoyed in the month of April, plus recent cultural news that I’m paying attention to…

BOOKSNOVEL: Tell Me Everything by Elizabeth StroutThis novel is my favorite of Strout’s that I’ve read so far, telling the story of very ordinary people living ordinary lives of care and selfishness and love and pain in a lovely but also rather ordinary town in Maine.

MOVIES AND SHOWSMOVIE: A Complete UnknownPeter and I both loved this biopic about Bob Dylan’s early years in New York City as he rose to stardom and refused to be boxed in as an artist. I was reminded of the reasons Dylan won the Nobel Prize for literature, and it also made me wonder whether genius comes along with misanthropy by necessity.

PODCAST EPISODESEPISODE: Lisa Damour: How to Talk to TeenagersI sent this podcast episode to all my friends who are parents of or work with teenagers.

THE BIBLE PROJECT: The Seven Women Who Rescued Moses—and Israel

If you’ve ever wondered whether the Bible has a subversive message within a patriarchal culture about the significance of women, this podcast episode is for you. Such an amazing and powerful and encouraging exploration of the role of women in the Exodus story and throughout the Bible

ESSAYSSTUDY: Measuring the Good LifeI’m so fascinated by the human flourishing study out of Harvard and Baylor, particularly when it comes to the factors that make up a “good life.” The data suggests that “economically developed countries have high average scores for self-rated financial well-being, access to education, and life evaluation. Yet poorer countries have higher scores for positive emotions, meaning and purpose, character and virtue, and social connection and relationships.” In other words, money doesn’t buy happiness, and it certainly doesn’t buy connection. Moreover, the data suggests that

“countries with the greatest wealth and longevity may have achieved these goods at the cost of a fulfilling life… for most people, flourishing is found above all in dense and overlapping networks of loving relationships.”

The post May 2025 Favorites appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

Grief and Disability

When a family receives a diagnosis—when they learn their child has a disability—grief often follows.

Matthew and Ginny Mooney define grief as:

“when the reality of life does not meet the expectations that you had.”

Grief shows up in the gap between what you expected… and what actually is.

That gap can be painful. We must have grace and tenderness for families in that space of grief. As friends, as a community—we come alongside them in love.

BUT this needs to be said:

The world should never grieve our children.

Our communities do not have the right to expect who our children “should” be. Instead…

The responsibility of our churches and of our society and of our cultures—when they meet our children—is:

to embrace themto provide them whatever support they needto meet them just as they are.TO OUR COMMUNITIES:

Our children are not less.

Our children are not tragedies.

They are not yours to grieve.

They are yours to love and welcome and support.

Let’s stay in touch. Subscribe to my newsletter to receive weekly reflections that challenge assumptions about the good life, proclaim the inherent belovedness of every human being, and envision a world of belonging where everyone matters. Follow me on Facebook , Instagram , and YouTube and subscribe to my Reimagining the Good Life podcast for conversations with guests centered around disability, faith, and culture.

The post Grief and Disability appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.