Amy Julia Becker's Blog, page 149

December 29, 2016

When God Doesn’t Clean Up the Mess in Your Life

Photo courtesy of Don McCullough

There are two ways for light to shine. There is overpowering light. Like the light of highbeams on a road at night. The light of the sun that makes us forget the stars and the rest of the universe even exist. Light so bright it hurts our eyes. Light that can even, ironically, blind us. And although there are a few times in the Bible when Jesus appears as a light like the sun, blazing in glory, those are very rare. We human beings can’t handle the dazzling reality of God’s holiness and glory and power and might.

But on Christmas we celebrate the light. We celebrate the days that follow the darkest day of the year, in eager expectation that more and more light will come each day. We celebrate every instance of good triumphing over evil. But it gets more specific. We celebrate the one who claimed to be “the light of the world.”

Jesus, the light of the world, does not come in blazing glory, bur rather, like a candle, like a star in the night sky, a light that shines in the midst of the darkness, not a light that extinguishes all the darkness, at least not yet. But even though he shines like a candle, we are invited to live in the light. If we choose to live in the light, we are promised two things. One, that darkness will be exposed. And two, that the light will guide our way.

By my reckoning, there are three types of darkness. There’s the darkness of personal moral failing, all the ways in which we wound others and ourselves, all our self-centered desires. It’s darkness that isn’t always easy to see, like a shirt that got a dribble of oil on it. When you look at the shirt in the dim light of your closet, it looks clean. And then you walk into the sunshine and realize that there’s a trail of oil for all the world to see. Jesus’ light exposes the “oil” on our shirt. Sometimes Jesus cleans that oil, those personal moral failings, right up. All of a sudden we no longer struggle with gossip, or anger, or alcohol, or impatience. But sometimes Jesus just exposes that stain for what it is and says, come with me anyway, even if you do have a mess on your shirt, even if you are a sinner, even if you haven’t got your act together.

Then there’s the darkness of the world around us—of war and orphans and poverty and depression and despair. Following Jesus means that we see the darkness, and we are invited to participate in shining light in those dark places, in changing the patterns of injustice.

And finally, there is the darkness of heartache. Of loved ones who have died. Of abandonment. Of natural disaster. Of things entirely out of our control that nevertheless snatch away the light. Jesus offers to shine his gentle light into that darkness too. He promises not to snuff out the smoldering candle, not to extinguish the fire that burns low. But rather to be the light of comfort, of peace, and of hope in that darkness.

So Jesus’ light exposes the darkness for what it is, and sometimes that feels uncomfortable, like walking around with a big stain on your shirt. But Jesus’ light also shows us the way. Light gives us comfort, guidance, reassurance that we are not alone on the path we walk. Light shows us how to walk in the darkness with sure feet, with confidence and purpose. Light draws us home. In this season of Christmas, as we celebrate the light of the world, let us give thanks that he exposes the darkness and invites us to walk in the light.

When God Doesn’t Clean Up the Mess in Your Life

Photo courtesy of Don McCullough

There are two ways for light to shine. There is overpowering light. Like the light of highbeams on a road at night. The light of the sun that makes us forget the stars and the rest of the universe even exist. Light so bright it hurts our eyes. Light that can even, ironically, blind us. And although there are a few times in the Bible when Jesus appears as a light like the sun, blazing in glory, those are very rare. We human beings can’t handle the dazzling reality of God’s holiness and glory and power and might.

But on Christmas we celebrate the light. We celebrate the days that follow the darkest day of the year, in eager expectation that more and more light will come each day. We celebrate every instance of good triumphing over evil. But it gets more specific. We celebrate the one who claimed to be “the light of the world.”

Jesus, the light of the world, does not come in blazing glory, bur rather, like a candle, like a star in the night sky, a light that shines in the midst of the darkness, not a light that extinguishes all the darkness, at least not yet. But even though he shines like a candle, we are invited to live in the light. If we choose to live in the light, we are promised two things. One, that darkness will be exposed. And two, that the light will guide our way.

By my reckoning, there are three types of darkness. There’s the darkness of personal moral failing, all the ways in which we wound others and ourselves, all our self-centered desires. It’s darkness that isn’t always easy to see, like a shirt that got a dribble of oil on it. When you look at the shirt in the dim light of your closet, it looks clean. And then you walk into the sunshine and realize that there’s a trail of oil for all the world to see. Jesus’ light exposes the “oil” on our shirt. Sometimes Jesus cleans that oil, those personal moral failings, right up. All of a sudden we no longer struggle with gossip, or anger, or alcohol, or impatience. But sometimes Jesus just exposes that stain for what it is and says, come with me anyway, even if you do have a mess on your shirt, even if you are a sinner, even if you haven’t got your act together.

Then there’s the darkness of the world around us—of war and orphans and poverty and depression and despair. Following Jesus means that we see the darkness, and we are invited to participate in shining light in those dark places, in changing the patterns of injustice.

And finally, there is the darkness of heartache. Of loved ones who have died. Of abandonment. Of natural disaster. Of things entirely out of our control that nevertheless snatch away the light. Jesus offers to shine his gentle light into that darkness too. He promises not to snuff out the smoldering candle, not to extinguish the fire that burns low. But rather to be the light of comfort, of peace, and of hope in that darkness.

So Jesus’ light exposes the darkness for what it is, and sometimes that feels uncomfortable, like walking around with a big stain on your shirt. But Jesus’ light also shows us the way. Light gives us comfort, guidance, reassurance that we are not alone on the path we walk. Light shows us how to walk in the darkness with sure feet, with confidence and purpose. Light draws us home. In this season of Christmas, as we celebrate the light of the world, let us give thanks that he exposes the darkness and invites us to walk in the light.

December 22, 2016

What if You Don’t Need to Be Successful? (Or, Advent Reflections on Joy)

I was grumpy for a few years. Maybe not every day. But most days. And at the core of my being, deep inside my heart, lay a stone, a slowly growing bitter stone of resentment and self-pity. I told myself it was because of my circumstances. In 2012, we moved with three children six and under, to a new house and a new town for my husband’s new job. I found myself in a cold, dark rental property while the house that came with the job was under renovation. I found myself spending hours every day consulting about fabric and paint samples and not writing. I found myself known as the “wife of” and the “mother of” rather than as someone with my own personality, my own passions, my own abilities. I found myself yelling at the children. I found myself unable (unwilling?) to pray.

I’ve written about those years—ones marked for me by dark, cold nights and a growing friendship with wine and nachos—before, but I was reminded of them last week when we watched It’s a Wonderful Life as a family. If you haven’t seen it, first of all—run, don’t walk, to the nearest library and check out a copy. But in case you don’t follow that fabulous advice or in case you forget, It’s a Wonderful Life is the story of George Bailey, a man who grows up in small town Bedford Falls. George is smart and handsome and filled with hope for his future. He’s going to college and then he’s going to travel the globe and become an engineer and build things and change the world.

He never achieves any of his goals. He never goes to college. He never travels anywhere. He never becomes an engineer. He never builds anything. Instead, he marries a hometown girl and takes over his father’s floundering business and has four kids. And one Christmas Eve, he comes face to face with the failure of his life. He sees how pointless it all has been. He realizes that he never fulfilled his potential and maybe he didn’t even have the potential in the first place. He wishes he had never been born.

Then Clarence, an angel second class, appears. Clarence shows George what the world would have been like without him in it. He shows him how small acts of kindness and self-sacrifice and duty change the world. He shows him the beauty of faithfulness in small things, like trusting a neighbor, like loaning a little money to a friend, like employing his Uncle Billy even though he is slightly incompetent. George’s life seems so inconsequential, so small, until he sees how the small acts of love add up to a life that matters. His resentment and self-pity and self-loathing turn to joy.

Photo courtesy of Liberty Films

Watching it for the umpteenth time, I wept. With each decision to serve someone else instead of himself, with each opportunity to make it big that George gives up, with the dawning recognition that his life was never valuable because of his aspirations or abilities, but was always valuable because of love, I wept.There’s a passage in the Bible that I think is related to George Bailey, and to me, and to all of us who think we need impressive resumes and accomplishments in order to prove our worth to the world. It’s a passage that has puzzled me for years. It comes at the end of Paul’s letter to the Philippians, where he writes, “I have learned the secret of being content in all circumstances.” Paul is writing from prison, so he clearly is not in the midst of fantastic circumstances. He’s been beaten and shipwrecked and deprived of food. He’s uncertain whether he will be released or be executed. And yet he claims to be content. He also claims that being content in all circumstances is something “secret,” something he had to learn. In the midst of my many years of discontent, I figured I just hadn’t learned the secret yet.

But when I read through Philippians again last summer I realized Paul had been trying to teach me the secret too. He hints at it when he says, just a sentence later, “I can do everything through Christ who strengthens me.” And, sure, the reason Paul is content even in the midst of prison and even when facing death has to do with his faith in Jesus. But the whole book of Philippians offers the key to this secret of contentment. And the theme of Philippians is joy.

For Paul, joy is a verb. “Rejoice!” he writes, over and over. “I say it again, rejoice!” As if joy is something to practice. Not a response to something fabulous happening, not a feeling, but an active way of being in the world. A choice. A choice even in the face of prison, death, failure, or the long and lonely nights of winter.

George Bailey’s circumstances didn’t change, but his view of his life changed. He went from despair to joy without ever leaving his disappointing little town. He found the secret to contentment whatever his circumstances.

I don’t know if I were to go back in time to four years ago, to that cold dark house with small children and an identity crisis, if I would be able to carry Paul’s exhortation with me and rejoice. I hope I would. Even now, I can’t claim to have learned the secret to being content in full. (Was it just this morning that I grumbled at my husband for not rinsing the crud out of the sink after he did the dishes?) But I know contentment begins with the choice to be joyful. What better time to start practicing joy but now?

What if You Don’t Need to Be Successful? (Or, Advent Reflections on Joy)

I was grumpy for a few years. Maybe not every day. But most days. And at the core of my being, deep inside my heart, lay a stone, a slowly growing bitter stone of resentment and self-pity. I told myself it was because of my circumstances. In 2012, we moved with three children six and under, to a new house and a new town for my husband’s new job. I found myself in a cold, dark rental property while the house that came with the job was under renovation. I found myself spending hours every day consulting about fabric and paint samples and not writing. I found myself known as the “wife of” and the “mother of” rather than as someone with my own personality, my own passions, my own abilities. I found myself yelling at the children. I found myself unable (unwilling?) to pray.

I’ve written about those years—ones marked for me by dark, cold nights and a growing friendship with wine and nachos—before, but I was reminded of them last week when we watched It’s a Wonderful Life as a family. If you haven’t seen it, first of all—run, don’t walk, to the nearest library and check out a copy. But in case you don’t follow that fabulous advice or in case you forget, It’s a Wonderful Life is the story of George Bailey, a man who grows up in small town Bedford Falls. George is smart and handsome and filled with hope for his future. He’s going to college and then he’s going to travel the globe and become an engineer and build things and change the world.

He never achieves any of his goals. He never goes to college. He never travels anywhere. He never becomes an engineer. He never builds anything. Instead, he marries a hometown girl and takes over his father’s floundering business and has four kids. And one Christmas Eve, he comes face to face with the failure of his life. He sees how pointless it all has been. He realizes that he never fulfilled his potential and maybe he didn’t even have the potential in the first place. He wishes he had never been born.

Then Clarence, an angel second class, appears. Clarence shows George what the world would have been like without him in it. He shows him how small acts of kindness and self-sacrifice and duty change the world. He shows him the beauty of faithfulness in small things, like trusting a neighbor, like loaning a little money to a friend, like employing his Uncle Billy even though he is slightly incompetent. George’s life seems so inconsequential, so small, until he sees how the small acts of love add up to a life that matters. His resentment and self-pity and self-loathing turn to joy.

Photo courtesy of Liberty Films

Watching it for the umpteenth time, I wept. With each decision to serve someone else instead of himself, with each opportunity to make it big that George gives up, with the dawning recognition that his life was never valuable because of his aspirations or abilities, but was always valuable because of love, I wept.There’s a passage in the Bible that I think is related to George Bailey, and to me, and to all of us who think we need impressive resumes and accomplishments in order to prove our worth to the world. It’s a passage that has puzzled me for years. It comes at the end of Paul’s letter to the Philippians, where he writes, “I have learned the secret of being content in all circumstances.” Paul is writing from prison, so he clearly is not in the midst of fantastic circumstances. He’s been beaten and shipwrecked and deprived of food. He’s uncertain whether he will be released or be executed. And yet he claims to be content. He also claims that being content in all circumstances is something “secret,” something he had to learn. In the midst of my many years of discontent, I figured I just hadn’t learned the secret yet.

But when I read through Philippians again last summer I realized Paul had been trying to teach me the secret too. He hints at it when he says, just a sentence later, “I can do everything through Christ who strengthens me.” And, sure, the reason Paul is content even in the midst of prison and even when facing death has to do with his faith in Jesus. But the whole book of Philippians offers the key to this secret of contentment. And the theme of Philippians is joy.

For Paul, joy is a verb. “Rejoice!” he writes, over and over. “I say it again, rejoice!” As if joy is something to practice. Not a response to something fabulous happening, not a feeling, but an active way of being in the world. A choice. A choice even in the face of prison, death, failure, or the long and lonely nights of winter.

George Bailey’s circumstances didn’t change, but his view of his life changed. He went from despair to joy without ever leaving his disappointing little town. He found the secret to contentment whatever his circumstances.

I don’t know if I were to go back in time to four years ago, to that cold dark house with small children and an identity crisis, if I would be able to carry Paul’s exhortation with me and rejoice. I hope I would. Even now, I can’t claim to have learned the secret to being content in full. (Was it just this morning that I grumbled at my husband for not rinsing the crud out of the sink after he did the dishes?) But I know contentment begins with the choice to be joyful. What better time to start practicing joy but now?

When You Want to Say “&%$!” to God (Or: Advent Reflections on Hope)

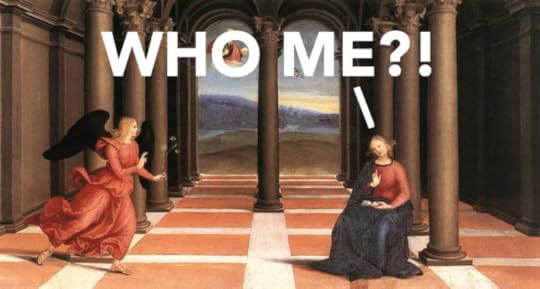

The Annunciation, Raphael

I was reading from the early chapters of Luke as a part of getting ready for Christmas, and I came to the moment when the angel appears to Mary. So the Bible translation I read says that when the angel appears Mary feels “greatly troubled.” Translating that into what I might say inside my head if an I were her is something along the lines of, “Oh, crap.” Then the angel tells Mary she’s going to have a baby, and Mary says, “Who, me? Are you sure you have the right person? I, um, I haven’t had sex yet and even though we don’t have sex ed here in Nazareth, I’m pretty sure I can’t have a baby unless I, um, you know… with someone?” And then the angel says, “Yep. That is correct. But in this case, God’s going to make it happen. That’s what you get to do when you’re God. Congratulations!” And Mary says, “Um, okay. I’m not going to disagree with God” (Luke 1: 26-38, my very loose translation).

I read that story one morning last week, and then we watched The Best Christmas Pageant Ever, in which a group of delinquent kids—the Herdmans—take over the Christmas pageant from the typical cast of characters. So instead of Mary being an angelic, blonde-haired, blue-eyed and rather self-righteous doll of a girl (Alice Wilkerson), she becomes a scared and confused kid who yells and cries and has dirt on her cheeks and under her fingernails (Imogene Herdman). All of a sudden Mary is a kid who is desperately trying to figure out how to take care of this baby entrusted to her, this baby she didn’t ask for and didn’t expect, this baby who may very well ruin her upcoming marriage to Joseph and leave her destitute and unable to provide for herself or the child.

We know Mary was frightened, because the angel says she doesn’t need to be afraid. We know Mary was confused, because she asks questions. And we might even be right in speculating that Mary was not thrilled about this news. That even with an angelic visitation, the situation felt pretty hopeless. She will soon be a poor, unmarried, teenage mother.

And then Mary goes to visit her cousin Elizabeth. Just imagine. You’re going to see your older relative, and you’re filled with this news that might be from God and also might have been a dream and might mean the end of your marriage that hasn’t even begun, and might mean your death (you could be stoned for having sex outside of marriage in those days). So, you, Mary, have no idea how to tell Elizabeth or what she will say. Maybe she will think you’re losing your mind and hallucinating. Maybe she will shun you like your religion says she should. Maybe however she responds will be a signal of how the rest of the world will respond.

So Mary gets there, and she doesn’t say anything to Elizabeth about being pregnant. She simply says hello. As soon as she says hello, Elizabeth says, “Blessed are you and blessed is the fruit of your womb!” Elizabeth, without knowing that an angel has visited, without knowing any of the details, echoes the words the angel has spoken.

Only now, only after Elizabeth has given affirmation to the angel’s words, does Mary rejoice. She proclaims what she has only dared hope up to this point: that God is actually going to do something beautiful and merciful and just and right and true in and through her, through the birth of this unexpected baby.

So what does it take for Mary to have hope? It takes God’s word, sure. But it also takes Elizabeth. It takes another person to affirm God’s work in Mary’s life. Hope depends upon God’s promises, but the way we have access to hope is as we speak the truth of those promises into one another’s lives.

This Christmas season, let us be Elizabeth to one another. Let us see what God has promised through Jesus and name that. Let’s call it forth. Let’s remind each other of what is true. That the God who is just and right and good hates injustice. That the God who is grace and mercy and light loves all people. That the God who spoke creation into being can handle our sins and sorrows. That the God who came to us as a baby helpless in a manger can handle our helplessness.

Once Elizabeth speaks that affirmation, Mary rejoices. And then she goes on to fulfill the purpose for which she has been chosen. She gives birth to a little boy, the light who shines hope for all the world to see.

When You Want to Say “&%$!” to God (Or: Advent Reflections on Hope)

The Annunciation, Raphael

I was reading from the early chapters of Luke as a part of getting ready for Christmas, and I came to the moment when the angel appears to Mary. So the Bible translation I read says that when the angel appears Mary feels “greatly troubled.” Translating that into what I might say inside my head if an I were her is something along the lines of, “Oh, crap.” Then the angel tells Mary she’s going to have a baby, and Mary says, “Who, me? Are you sure you have the right person? I, um, I haven’t had sex yet and even though we don’t have sex ed here in Nazareth, I’m pretty sure I can’t have a baby unless I, um, you know… with someone?” And then the angel says, “Yep. That is correct. But in this case, God’s going to make it happen. That’s what you get to do when you’re God. Congratulations!” And Mary says, “Um, okay. I’m not going to disagree with God” (Luke 1: 26-38, my very loose translation).

I read that story one morning last week, and then we watched The Best Christmas Pageant Ever, in which a group of delinquent kids—the Herdmans—take over the Christmas pageant from the typical cast of characters. So instead of Mary being an angelic, blonde-haired, blue-eyed and rather self-righteous doll of a girl (Alice Wilkerson), she becomes a scared and confused kid who yells and cries and has dirt on her cheeks and under her fingernails (Imogene Herdman). All of a sudden Mary is a kid who is desperately trying to figure out how to take care of this baby entrusted to her, this baby she didn’t ask for and didn’t expect, this baby who may very well ruin her upcoming marriage to Joseph and leave her destitute and unable to provide for herself or the child.

We know Mary was frightened, because the angel says she doesn’t need to be afraid. We know Mary was confused, because she asks questions. And we might even be right in speculating that Mary was not thrilled about this news. That even with an angelic visitation, the situation felt pretty hopeless. She will soon be a poor, unmarried, teenage mother.

And then Mary goes to visit her cousin Elizabeth. Just imagine. You’re going to see your older relative, and you’re filled with this news that might be from God and also might have been a dream and might mean the end of your marriage that hasn’t even begun, and might mean your death (you could be stoned for having sex outside of marriage in those days). So, you, Mary, have no idea how to tell Elizabeth or what she will say. Maybe she will think you’re losing your mind and hallucinating. Maybe she will shun you like your religion says she should. Maybe however she responds will be a signal of how the rest of the world will respond.

So Mary gets there, and she doesn’t say anything to Elizabeth about being pregnant. She simply says hello. As soon as she says hello, Elizabeth says, “Blessed are you and blessed is the fruit of your womb!” Elizabeth, without knowing that an angel has visited, without knowing any of the details, echoes the words the angel has spoken.

Only now, only after Elizabeth has given affirmation to the angel’s words, does Mary rejoice. She proclaims what she has only dared hope up to this point: that God is actually going to do something beautiful and merciful and just and right and true in and through her, through the birth of this unexpected baby.

So what does it take for Mary to have hope? It takes God’s word, sure. But it also takes Elizabeth. It takes another person to affirm God’s work in Mary’s life. Hope depends upon God’s promises, but the way we have access to hope is as we speak the truth of those promises into one another’s lives.

This Christmas season, let us be Elizabeth to one another. Let us see what God has promised through Jesus and name that. Let’s call it forth. Let’s remind each other of what is true. That the God who is just and right and good hates injustice. That the God who is grace and mercy and light loves all people. That the God who spoke creation into being can handle our sins and sorrows. That the God who came to us as a baby helpless in a manger can handle our helplessness.

Once Elizabeth speaks that affirmation, Mary rejoices. And then she goes on to fulfill the purpose for which she has been chosen. She gives birth to a little boy, the light who shines hope for all the world to see.