Amy Julia Becker's Blog, page 142

November 8, 2018

Revisiting: Deep Calls Out To Deep, But I Long To Stay Shallow

Candy, mindless scrolling through my phone, checking email instead of working on something of substance, avoiding exercise and time outside, keeping conversation light instead of asking the deeper and more interesting questions… I so often live in this shallow place, but the reason I write is as an invitation to myself and to others to go deeper and to find the wonder and joy of that deeper place. A reader reminded me of what I wrote about this topic a few years ago for Christianity Today, and I wanted to share it again here:

In March, we went on vacation as a family. It was a beautiful trip—clear skies, blue water, white sandy beaches. The resort where we stayed offered a “kids club” in the morning, so I had time for walks by myself and with Peter, for naps in the shade of a palm tree, for times of prayer, for reading lots of books. It was extravagant and luxurious and strangely challenging all at the same time.

Every day after camp, our kids wanted to go to the pool. They wanted to jump into the safe, contained, semi-toxic water. They wanted to dive for rings on the pool’s concrete floor. They wanted to get a drink at the poolside bar. Every day, we tried to cajole them toward the ocean instead. The ocean, filled with rocks and coral, teeming with life. This vast expanse of water required our respect and our attention with its powerful waves, its constant motion. They liked it once we were there—the feeling of their toes in the sand, the sight of hermit crabs scuttling across the beach, the pulsing rhythm of the water. But even then, every day, they wanted to go back to the pool.

I want to teach our children, and I want to challenge myself, to swim in the ocean. I mean this literally, but I also mean it in every other aspect of our lives.

The easiest area to see this tension in our lives is with food. Recently, our kids have been offered candy at every turn—Easter eggs in the backyard from the church youth group, Easter candy from aunts and uncles, Easter candy in Sunday school, and more from a family egg hunt. Jellybeans, Starburst, Twix, Peeps. Tastes great. Rots their teeth. Gives a burst of energy. And then a crash. They would always choose candy over, say, the lentil soup I offered last night. They would always choose donuts over scrambled eggs, cake over a turkey sandwich. And yet it’s the eggs, the soup, the sandwich that actually fuel their bodies, and that ultimately allow them to develop an appreciation for the glories of the diversity of tastes and textures out there for them to enjoy.

The same can be said for television. My kids have all figured out how to navigate the kids section of Netflix on our TV. They gravitate toward shows that resemble those same candies I mentioned above—big-eyed cartoon figures with colorful outfits and valley girl accents. But I tell them they have to watch shows where they actually learn something, like Wild Kratts, or where there’s a semi-substantial story line, like Angelina Ballerina. They usually try to come up with some reason why Strawberry Shortcake is educational, but I’m not buying it. When it comes to books, there’s also plenty of junk out there, words that are easy to consume without thought.

As an adult, I find myself gravitating towards these same places—eating the candy bar, scrolling through Facebook instead of reading one of the novels on my bedside table, letting a dinner conversation stay light instead of engaging topics that might challenge us. It’s not just me, and it’s not just my kids. The books that fly off the shelves are the ones that keep us on the surface of a mystery or a scintillating adventure. The movies that make millions generally do so via sex and violence. The food companies that make billions aren’t selling organic produce.

It all makes me wonder—why are we so afraid of the ocean?

In Psalm 42, the psalmist writes, “Deep calls to deep in the roar of your waterfalls.” It’s a bit of a cryptic line, in the midst of a psalm about loss and longing and a soul that is inexplicably downcast. And yet I wonder whether this poetic phrase might tell us something about why we all are tempted to stay away from deep water.

To stay in God’s presence is like swimming in the ocean. Immense. Frightening. Powerful. Beautiful. Where deep calls to deep. Where answers don’t come easily. Where pain is exposed rather than covered over. Where healing requires transformation.

I think the reason I gravitate toward sugar and fluff, and the reason my kids do, and the reason our culture does, is that we want to avoid the dangerous truth that God is God and we are not. Whether it’s food, chitchat, hours on Pinterest, or watching mindless television, we have constructed countless ways to avoid looking at the mess and brokenness within our souls.

We live in a world where it is easy to avoid the hard questions, to ignore our own selfishness, to fill our days with busy but meaningless activity. Deep calls out to deep, but sometimes I long to stay shallow.

Every day on vacation, we let our kids swim in the pool. But we also insisted that they spend some time near the ocean—looking at it or swimming in it or just squatting as the waves rolled toward their toes. I hope we were cultivating in them, and in ourselves, respect for its power, humility in the face of its beauty, and joy in its delightful and ongoing invitation to play. Deep calls out to deep, even in the midst of internet distractions and fast food restaurants and mind numbing entertainment. Deep calls out to deep, and we are all invited to enter in.

The post Revisiting: Deep Calls Out To Deep, But I Long To Stay Shallow appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

October 31, 2018

On Political Correctness and Learning the Language of Love

Today was Halloween, and Halloween is now a holiday, like many others, that brings up the subject of political correctness. Some costumes obviously disrespect people of other races and cultures. Others unintentionally appropriate traditions that cheapen symbols and minimize attire of its cultural significance. Especially for people who have grown up in the majority culture (which is to say, people like me), it can be easy to be confused or annoyed or bewildered by it all.

A few weeks ago, I heard about a teacher who described how she taught kids to hold a pencil and she said, “The mom and dad are up front, and the child is in the backseat of the car.” Someone later pointed out to her that she had made an assumption about family structure that wouldn’t apply to all the kids in her class. Her language was unintentionally excluding some students.

The list of similar examples could take up the rest of the page, and we could wage a healthy debate over freedom of speech and common humanity and when and whether people are being overly sensitive. But as I’ve thought about my own posture, whether or not to change the way I speak, and the illustrations I use, the costumes I encourage our kids to wear, I’ve thought about why we might choose to be as careful and thoughtful as we know how in this area. I don’t want change to come because of fear. I don’t want to live behind a wall of defensiveness or shame. Rather, I want to live in the freedom of knowing I will make mistakes and many people will be gracious to me when I do.

The reason I want to pay attention to language and costumes and other ways political correctness can manifest itself is out of love. I want to demonstrate love for my neighbors, broadly speaking. I want our language to reflect respect. I want our costumes to be fun and celebratory not just for our kids but, to the degree that it is possible, for everyone they encounter.

I was speaking in a classroom last week with a diverse group of students. At one point I described the experience of taking African American studies classes in college, and I said that I was “a minority” in those classes. I realized later that I misspoke. When it came to racial identity, as a white person I was in the numerical minority. But as a white student on an Ivy League campus, I was never—even in those classrooms—carrying the weight of history and contemporary events that communicated to me that I was on the outside. I will be more careful about my use of the word “minority” in the future, not because I am afraid of what other people will say, but because I want to demonstrate thoughtfulness, love, and respect in how I speak.

This leads to my final point about costumes and language. Over the years, various people who are dear to me have used un-politically correct language to talk about Penny or people with intellectual disabilities or Down syndrome. Some of them have later apologized for it. I’m not going to say I don’t notice the language, or that it doesn’t matter. But the apology, the care for us that emerges out of love, matters much more. I hope the same is true for me, for my bumbling attempts to live in a way that honors my friends and neighbors from different religious traditions than mine, different cultural backgrounds than mine, different abilities than mine, and on down the list. I want to be a person who makes mistakes and makes corrections not out of fear, but out of a desire to speak a language of love.

The post On Political Correctness and Learning the Language of Love appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

On Halloween and Learning the Language of Love

Today was Halloween, and Halloween is now a holiday, like many others, that brings up the subject of political correctness. Some costumes obviously disrespect people of other races and cultures. Others unintentionally appropriate traditions that cheapen symbols and minimize attire of its cultural significance. Especially for people who have grown up in the majority culture (which is to say, people like me), it can be easy to be confused or annoyed or bewildered by it all.

A few weeks ago, I heard about a teacher who described how she taught kids to hold a pencil and she said, “The mom and dad are up front, and the child is in the backseat of the car.” Someone later pointed out to her that she had made an assumption about family structure that wouldn’t apply to all the kids in her class. Her language was unintentionally excluding some students.

The list of similar examples could take up the rest of the page, and we could wage a healthy debate over freedom of speech and common humanity and when and whether people are being overly sensitive. But as I’ve thought about my own posture, whether or not to change the way I speak, and the illustrations I use, the costumes I encourage our kids to wear, I’ve thought about why we might choose to be as careful and thoughtful as we know how in this area. I don’t want change to come because of fear. I don’t want to live behind a wall of defensiveness or shame. Rather, I want to live in the freedom of knowing I will make mistakes and many people will be gracious to me when I do.

The reason I want to pay attention to language and costumes and other ways political correctness can manifest itself is out of love. I want to demonstrate love for my neighbors, broadly speaking. I want our language to reflect respect. I want our costumes to be fun and celebratory not just for our kids but, to the degree that it is possible, for everyone they encounter.

I was speaking in a classroom last week with a diverse group of students. At one point I described the experience of taking African American studies classes in college, and I said that I was “a minority” in those classes. I realized later that I misspoke. When it came to racial identity, as a white person I was in the numerical minority. But as a white student on an Ivy League campus, I was never—even in those classrooms—carrying the weight of history and contemporary events that communicated to me that I was on the outside. I will be more careful about my use of the word “minority” in the future, not because I am afraid of what other people will say, but because I want to demonstrate thoughtfulness, love, and respect in how I speak.

This leads to my final point about costumes and language. Over the years, various people who are dear to me have used un-politically correct language to talk about Penny or people with intellectual disabilities or Down syndrome. Some of them have later apologized for it. I’m not going to say I don’t notice the language, or that it doesn’t matter. But the apology, the care for us that emerges out of love, matters much more. I hope the same is true for me, for my bumbling attempts to live in a way that honors my friends and neighbors from different religious traditions than mine, different cultural backgrounds than mine, different abilities than mine, and on down the list. I want to be a person who makes mistakes and makes corrections not out of fear, but out of a desire to speak a language of love.

The post On Halloween and Learning the Language of Love appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

October 25, 2018

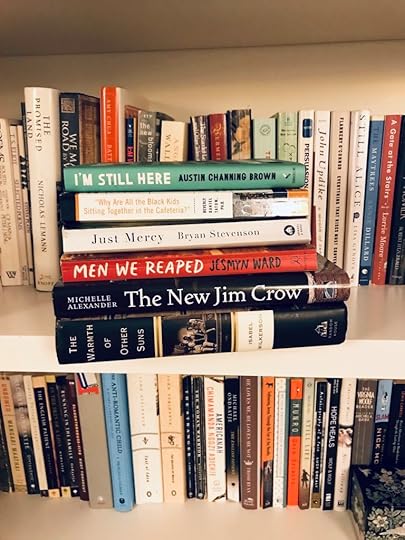

7 Non-Fiction Books I Recommend for (White) People Who Want to Understand Our Racial Divides

Lately I have been getting a lot of questions about books that I recommend for people who want to further understand our racial divides, and that have helped shape my thinking. There are dozens of other books worth reading, and this is by no means a comprehensive sample, but these are books that informed my thinking as well as my feelings about where we are as a nation when it comes to racial division, and how we can move forward towards systems of justice, housing, education, and life experience that offer comparable opportunities for all the people.

The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson. This Pulitzer Prize-winning, comprehensive history of the Great Migration of African American men and women from the South to the West, Midwest, and Northeast of the United States is by turns riveting and heartbreaking. Told through the lens of three main narrators who head to Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York City, this narrative is both intimately connected to individuals and sweeping in its scope. It gives a compelling overview of the past hundred years of African American history and offers a helpful background for understanding where we are in the present day.

Locking Up Our Own by James Foreman. Foreman, a lawyer and the son of a civil rights activist, offers a nuanced perspective of the criminal justice and mass incarceration system in America. He addresses the questions he faced as a young lawyer defending young men in a system that seemed to be stacked against people of color, and examines the policies that got us there. He not only exposes the white power structures at work but also the ways in which black communities supported laws and policies that have led to a disproportionate number of black men especially behind bars. I also recommend The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander (and I have Rethinking Incarceration by Dominique Gilliard on my list), but Locking Up Our Own offers the broadest view I’ve seen of the system, its problems, and the urgent need for reform.

Just Mercy by Bryan Stevenson. Another black lawyer writing about the criminal justice system, though this one is from the perspective of a man who has been defending largely poor, black, southern men facing the death penalty for most of his career. Stevenson’s grim portrayal of an unjust system comes alongside his hope for a better future. Stevenson not only wrote a powerful and compelling book, but he has also led the initiative to create the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, a memorial in Alabama that acknowledges and honors the thousands of men and women of color who died by way of lynching throughout our history.

Why are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria ? by Beverly Daniel Tatum. This classic book, now 20 years old, offers a winsome and helpful guide through the concept of developing a racial identity.

I’m Still Here by Austin Channing Brown. An inside look at what it feels like to be a black woman in American society. Brown is a terrific storyteller and makes it easy for a reader to enter into these pages. While this book offers a piercing critique, Brown also writes that she stands in the “shadow of hope” as she looks towards the future.

Men We Reaped by Jesmyn Ward. Ward is a two-time National Book Award winner for her two most recent novels (which are very much worth reading in their own right), but this book is a memoir about her adolescence and young adulthood in Mississippi. She suffered the loss of five men she loved over the course of a few years, and this memoir traces those years and those deaths and places them in the larger context of the precarious nature of being a black man in America.

Between the World and Me by Ta Nehisi Coates. Coates’ memoir stands alongside Brown’s and Ward’s as a work that bears witness to the oppression black people experience simply for being black. Coates, a national correspondent for the Atlantic, offers the most bleak portrait of American life as he writes a letter to his son about what it is like to be a black man in America. And as much as I believe in the need to have hope, and to work towards justice, and to see the light shining even in the midst of grim realities, Coates’ book challenged me to acknowledge the reasons for despair.

The post 7 Non-Fiction Books I Recommend for (White) People Who Want to Understand Our Racial Divides appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

October 17, 2018

For Those Who Worry

I used to have a hard time calling myself a sinner. It wasn’t that I didn’t believe in sin. Conceptually, I’m on board. Sin is everything that separates me from God, from Love, from good and free relationships with self, creation, and other human beings. I see sin’s effects on a global level: every day when I scroll through the New York Times headlines. I see sin on a mundane and local level: every day when Penny asks William to stop making noises and he persists and she yells and he persists and she yells again, every day when William asks Penny to stop reading out loud and she persists and he yells and she persists and he yells again. . .

Our kids are pretty good at admitting that they got mad, that they responded badly, that they need to ask for forgiveness. Me, not so much.

As a type-A, perfectionistic, enneagram 1 personality, I have a hard time seeing my own sin (and probably, truth be told, an even harder time admitting it). Peter and I once got in an argument and he said, “It’s just hard to be married to someone who is always right.” I know what he means. It’s hard to see myself as a sinner when I’m always right. (Now, by “right,” I mean that I do things in a way that is correct and proper, but not necessarily in a way that is loving or gracious or good. Just in a way that is almost impossible to criticize or name as wrong.)

The other thing that goes with not being able to see myself as a sinner is that it’s hard to receive forgiveness. It’s hard, therefore, to know myself as loved for who I am, not how I perform, and hard to love others that way too.

But recently I’ve noticed two things. One, worry is a sin. Worry might even be one of the very worst sins–the thing that keeps me most distanced from God. I’ve quoted before the guy who said that worry is a prayer I pray to myself, and I’ve noticed the multiple admonitions in the Bible to not worry and instead trust in God. But I’ve only recently put two and two together and realized that the opposite of worry is faith. The opposite of anxiety is trust.

The other thing I’ve noticed lately is that I worry a lot. I worry about getting things done. I worry about each one of our kids and their friendships and learning and socialization. I worry about what people think of me. I worry about how I look. I worry about spending too much money. I worry about being too serious. I worry about eating crappy food. I worry a lot. All of which is to say, I sin a lot. I don’t trust in God, a lot.

Here’s the beauty of recognizing that worry is a sin at the same time that I recognize that I worry a lot: I can confess it. I can turn away from it. I can ask for forgiveness and replace the worry with trust, with humble confidence in God’s goodness and provision and protection for me. And I can rejoice in the promise that God’s mercies are new every morning, because somehow my worries seem to be new every morning as well.

The post For Those Who Worry appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

October 10, 2018

An Erroneous S and the Power of Language: Why My Book Had to be Reprinted at the Last Second

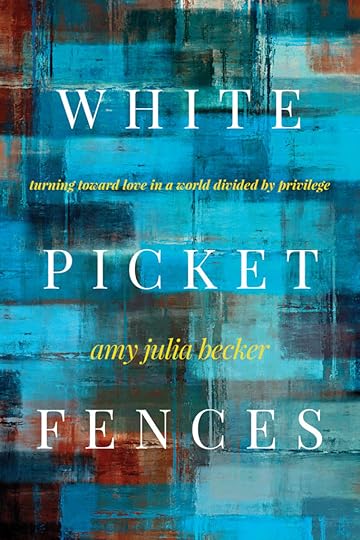

For the past few years, I’ve been working on a memoir about race, class and disability called White Picket Fences: Turning toward Love in a World Divided by Privilege. Getting the language right around these sensitive topics matters in any context, but as a white Christian woman writing for a Christian publishing house, careful attention to every word seemed imperative. The political alignment of evangelicals with the Republican party and President Trump has raised concerns that evangelicals dismiss politically correct language out of hand. And yet evangelical Christians are also known as people with a high view of the authority of the Bible, a text that includes admonitions such as “honor everyone” (the Bible, 1 Peter 2:17, NRSV) and “the only thing that counts is faith working through love” (Galatians 5:6). Both the Old and New Testaments encourage believers to be careful and thoughtful with our speech, restricting hateful words, slander, and gossip, and being “slow to speak” and “quick to listen.” In this cultural climate, Christians need to be doubly careful that language does not create a barrier to conversation.

So when I discovered that a proofreader had accidentally typed in the word “whites” instead of “white” when describing people in my book, my editor and publisher agreed that the books needed to be reprinted. Thousands of books were thrown away two weeks ago, and the publication of the book was delayed as a result of one erroneous “s.” It was a matter of integrity, credibility, hospitality, and hope.

Throughout the writing process, I tried to avoid catch-phrases that might signal I was taking political “sides.” Words like “systemic injustice” and “white hegemony” can function as code to demonstrate progressive ideology, just as words like “law and order” can signal conservative leanings. Religious language can also exclude: phrases like “born again” or “Bible study” warrant explanation. Clarity in language is essential to welcoming an audience of readers, and I wanted an audience that spanned the political and social divides within our nation.

When it came to the particular error of the word “whites,” we insisted on the correction because, as Daniel King and Dodai Stewart have pointed out: Nouns define. Adjectives describe. I am a white person, not a white. My friend Patricia is a black person, not a black. Our personhood defines us. Our ethnic heritage, our religious beliefs, our physical features—they describe us. In a book devoted to upholding the view that we can only explore and understand our differences once we have embraced our common humanity, the language had to reflect that commitment.

I’ve learned about the significance of even subtle shifts in language personally. When our daughter Penny was diagnosed with Down syndrome at birth twelve years ago, I saw the way medical terminology and common speech dehumanized her, reducing her to a problem instead of a little girl. I learned about “person-first language, and I started to say “We have a baby with Down syndrome” rather than, “We have a Down’s baby.”

This “person-first” language more accurately described Penny, but in using that language I also found myself perceiving her differently. Language reflects reality, but it also shapes our perception of reality. In time, her diagnosis receded into the background and her individuality came forth. When I think of Penny now, her diagnosis is one aspect of her personhood that comes to mind, alongside her love for reading, her obsession with weddings, her willingness to risk being late for school because she is practicing the steps she learned in ballet class last night, and her new seventh-grade friendships that involve giggles and nail polish and occasional tears.

Christians have a distinct opportunity to offer a message of hope and love in the midst of gaping cultural divides and wounds that have to do with historical and current racism, economic inequality, and bias. The Christian tradition teaches that we are created in the image of God, in the image of Love, and that our purpose on this earth is to love our neighbors with sacrificial, healing, patient and enduring love. Stories are one way to convey that message, but in order for those stories to convey that message with credibility and integrity, we must demonstrate sensitivity with every word. Language is an act of hospitality. Language provides a way to name what is true about our common humanity, even if it means that thousands of books needed to be thrown away.

Two additional notes: One, if you received a pre-ordered copy of White Picket Fences from Amazon, chances are you received a copy with the erroneous s (a few hundred were already in the Amazon pipeline when we discovered the problem). Check page 18. If you want a new copy of the book, please let me know and I will put you in touch with my publisher.

Two, I discovered the erroneous S, which was an error typed in by someone else. I also discovered that my About the Author at the back of the book contains an error. It says I received a Masters in English from Princeton University, which is not true. I received a Bachelors in English from Princeton University and a Masters of Divinity from Princeton Theological Seminary. When I read this error, I assumed someone on the production-side of the book had created it. But no. It was me. I just accidentally misrepresented myself. It will be fixed in subsequent printings of the book. I write this both to try to correct it in public and also to make it clear that we all make mistakes with language and we all need grace!

The post An Erroneous S and the Power of Language: Why My Book Had to be Reprinted at the Last Second appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

October 3, 2018

Why I Wrote White Picket Fences

One of the questions I get asked a lot about White Picket Fences: Turning toward Love in a World Divided by Privilege is why I wrote it. Why would I want to turn a mirror on my own privileged existence as an affluent, educated, white American woman? It’s a challenge to be vulnerable and publicly self-reflective at any time, and we currently live in a particularly polarized social climate. Warring left- and right-wing views seem to dominate the airwaves, and saying the wrong thing in front of either audience can escalate quickly and hurt people.

I don’t have a great answer as to why I wrote it. All I can say is that I felt compelled to do so. It wasn’t so much that I decided to write White Picket Fences as that I discovered it was the book I was already writing.

But what I can say is what I hope this book offers. I hope it offers a different way to navigate the questions that come up when talking about privilege, a way of hope instead of fear, a way of healing instead of guilt, a way of growth instead of despair.

As I see it, the predominant responses to the concept of privilege among privileged people consist of shame and denial. For anyone who is willing to admit that privilege exists—that some of us were born into opportunities denied to others by virtue of history, genetics, family, ethnicity, and so forth—acknowledging that privilege and how it operates can lead to guilt, to shame, and to despair because the forces that got us here are big and often invisible and seem very much out of our personal control.

Others respond to the idea of privilege with denial and defensiveness, arguing about the ways they have worked hard for their position in life or identifying ways that whiteness and wealth seem like disadvantages in a politically correct climate.

Neither shame nor denial motivate positive change, and neither shame nor denial honor the full humanity of the people involved. I have believed for a long time that hope allows us to envision a better future, and that love is stronger than fear. White Picket Fences is an attempt to think those ideas through and offer a way for people to understand privilege and then to respond to it not with shame or denial, but with hope, with love.

It sounds like Kumbaya, like a call to individual kind actions that will never amount to pervasive social change. It might even sound like encouragement for people in power to solve social problems. But this book fails if it leads in those directions.

Rather, I hope this book is an invitation to humbly acknowledge what we have been given that we do not deserve, and to gratefully consider how we can use those gifts for the good of others. I hope this book is a call to connect—to God, to one another—rather than a call to act as individuals. And I hope this book is one small step away from shame, away from fear, away from denial, one small step towards love.

The post Why I Wrote White Picket Fences appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

September 27, 2018

When Serving Others Means Letting Yourself Be Served

So there’s this famous verse in the Bible where Jesus says he came “not to be served but to serve.” It’s a verse that crept out of the Bible and into literature and even schools—when I was in high school, the Latin version of this saying was our motto. For me, it became a nice saying, a nice ideal. But recently these words have puzzled me. I’ve been thinking about what these words actually mean.

Jesus did indeed serve others, but he also allowed himself to be served. There’s the story of Mary and Martha, where Martha toils in the kitchen while Jesus is teaching and presumably Jesus allows Martha to serve him dinner afterwards. There’s the story of the woman with perfume who pours it at Jesus’ feet and serves him . He reclines at the table on various occasions—Simon the Pharisee serves him dinner, he goes to parties.

Jesus is also the most consistent human being I know. He does what he says. He lives out his teaching. But on this point he seems inconsistent. Why did the guy who said he was there not to be served but to serve let other people serve him, repeatedly?

Here’s what I think:

One, I think Jesus meant that he didn’t come to be superior to others but rather to be right alongside us, with us.

Two, I think he knew that one form of superiority comes in the unwillingness to be served. When we are unwilling to receive anything from others, we cut ourselves off from them.

Three, I think Jesus let other people serve him because sometimes that was the more humble, generous, kind, and human thing to do. It honored their gifts and their offerings. It established reciprocal relationships.

The bottom line is that Jesus both taught and embodied love, and love is about both giving and receiving.

Which means for those of us who are seeking to follow Jesus, sometimes we need to humble ourselves by serving others, and sometimes we need to humble ourselves by being served.

The post When Serving Others Means Letting Yourself Be Served appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

When Serving Other Means Letting Yourself Be Served

So there’s this famous verse in the Bible where Jesus says he came “not to be served but to serve.” It’s a verse that crept out of the Bible and into literature and even schools—when I was in high school, the Latin version of this saying was our motto. For me, it became a nice saying, a nice ideal. But recently these words have puzzled me. I’ve been thinking about what these words actually mean.

Jesus did indeed serve others, but he also allowed himself to be served. There’s the story of Mary and Martha, where Martha toils in the kitchen while Jesus is teaching and presumably Jesus allows Martha to serve him dinner afterwards. There’s the story of the woman with perfume who pours it at Jesus’ feet and serves him . He reclines at the table on various occasions—Simon the Pharisee serves him dinner, he goes to parties.

Jesus is also the most consistent human being I know. He does what he says. He lives out his teaching. But on this point he seems inconsistent. Why did the guy who said he was there not to be served but to serve let other people serve him, repeatedly?

Here’s what I think:

One, I think Jesus meant that he didn’t come to be superior to others but rather to be right alongside us, with us.

Two, I think he knew that one form of superiority comes in the unwillingness to be served. When we are unwilling to receive anything from others, we cut ourselves off from them.

Three, I think Jesus let other people serve him because sometimes that was the more humble, generous, kind, and human thing to do. It honored their gifts and their offerings. It established reciprocal relationships.

The bottom line is that Jesus both taught and embodied love, and love is about both giving and receiving.

Which means for those of us who are seeking to follow Jesus, sometimes we need to humble ourselves by serving others, and sometimes we need to humble ourselves by being served.

The post When Serving Other Means Letting Yourself Be Served appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

September 19, 2018

Why Instagram?

A few years ago, I stopped blogging. I had never been great on social media. I like to take time to think about things. (Which can be a liability—especially when small human beings are in crisis situations and I’m reflecting on the seriousness of the situation. Thankfully I have a husband who reacts very quickly to crisis while his wife ponders.) I like long sentences. I like timeless truths. I don’t watch the news. So I stopped blogging and I kept a toe in the water of Facebook and even less of me on Twitter and let that be that.

Along came Instagram, and I ignored it. It just seemed like too much to try to learn something new and add something new and follow people and post stuff and all the rest. There’s also the fact that I’m also not a very visual person. I gravitate to a world of abstract ideas, and I so appreciate people who can capture moments visually instead of in words. I just don’t think of myself as one of those people.

But at the same time, I keep hearing that the things I really love—reflective stories, whether visual or text—are happening on Instagram. My friend Micha (@acefaceismyfriend) talked about the community of mothers with kids who have Down syndrome she found via Instagram. My other friends and my sisters and so many other people have talked about how much they prefer Instagram to Facebook. My writer friends talk about how important it is for an author.

I still resisted. There was my reluctance to try new things, my desire to set limits and stick to them, and the general sense of overwhelm that the internet presents me on a daily basis. There was also my concern that I might make our children into props in the fabricated story of my life. And there was what one friend called the risk that I would ruin a moment by trying to capture that moment.

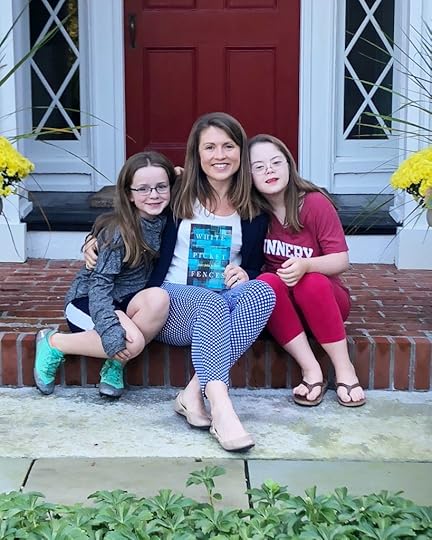

With all that said, I decided to start an Instagram account. Some of that comes down to having a new writing assistant who knows what she’s doing on social media (thank you, Emily!). Some of it comes down to the desire to get White Picket Fences out into the world even if it does stretch me. But it also goes back to what I do hope to create by telling the story of my life and our family in such a public forum. Yes, I love words. I’ve written four books now, and the words don’t seem to stop. Still, I’ve always also wanted to share photos, especially of our daughter Penny, because I know that seeing a family with a child with Down syndrome bears witness to the truth of the words I have been writing. In fact, early on I realized that I had trouble envisioning a life with a child with Down syndrome and as a result I had trouble imagining a life with a child with Down syndrome. As I have written elsewhere, the imagination is a vehicle for hope. My hope is that these photographs tell a story of possibility, that they invite followers to imagine a good future, that they invite hope.

So if you are on Instagram, I’d love to see you there! You can find me at @amyjuliabecker.

The post Why Instagram? appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.