Amy Julia Becker's Blog, page 139

June 21, 2019

“Take Courage” Podcast Episode: Hope and Healing

Matt Miller is a pastor and communicator in Memphis, TN. He has a new podcast called Take Courage. In the recent “Hope and Healing” episode he interviewed me about writing White Picket Fences.

I guess it’s fair to call it courageous to write this book, only because, as Matt points out, I have the luxury as an educated, affluent, white person to ignore issues related to race and class and privilege if I want to. It feels like a pretty small, and safe, offering to tell our story, but I was grateful for the chance to talk with Matt about how having a child with a disability has changed my understanding of a good life, how I began to reevaluate the “goodness” of my childhood as an adult, and the invitation we all have to enter into healing.

Listen to the podcast here (or if you use Apple podcasts here)

The post “Take Courage” Podcast Episode: Hope and Healing appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

June 19, 2019

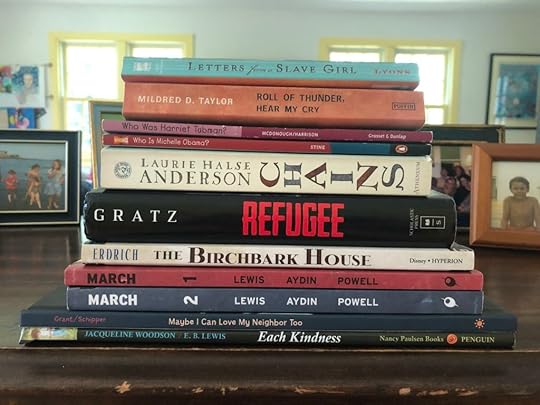

7 More Diverse Book Recommendations & A Deeper Look

In a previous post, I set out to select 20 diverse books from a few of our children’s favorites in various age groups: toddler, pre-school, early elementary, later elementary, middle school. It seemed like an easy task. But then when I was compiling this list, I decided to look up the author photos. I realized that I was suggesting a number of books with characters who were people of color that were written by white women and men.

Our bookshelves are far more diverse than they once were, but I still have a lot to learn.

This discovery prompted a set of questions:

Is it important for books to be written by people who share the experience of the main characters?

What do we do with “classic” books when they don’t accord with our contemporary standards?

What about historical fiction?

What about books with a white main character and diverse others?

The history of the publishing industry is one of whiteness, where even books that included people of color as characters were almost always depicted by white people. For Ezra Keats to depict Peter in The Snowy Day as an African American boy could be seen as cultural appropriation. It also could be seen as the move of an ally, a white man using his influence to open doors for the representation of African American children on the pages of picture books.

For parents or teachers to select Little House on the Prairie for younger students or To Kill a Mockingbird for older kids could, in both cases, perpetuate an historical narrative of white dominance. Or we could pair these classic texts with other books written from diverse perspectives about the same time period.

Louise Erdrich, a National Book Award winning author and Native American, has written a series of novels for kids that depict a Native American family in the midwest around the same time as the Little House books.

Roll of Thunder Hear my Cry is set in a similar time and place as To Kill a Mockingbird. Our present experience can be in conversation with these books from the past, just as these books can speak to each other and help us to see both their limitations and the possibilities for understanding that they open up to us.

One of the gifts of great literature is yes, I find a doorway into another time, place, and culture. But the deeper gift is that as I walk through that doorway, I also find myself looking into a mirror because this “other” in fact, knows me well. And so I see myself in Chloe, who regrets her failure to welcome a new student in Woodson’s Each Kindness. I recognize myself in Cassie Logan, who wants nothing more than a stack of books on Christmas morning in Roll of Thunder Hear my Cry. I see our daughter Marilee as we read about Omakays in The Birchbark House, with her passion and her grief and her determination and her irrepressible spirit.

It has taken decades for the publishing industry to begin to change (see #weneeddiversebooks), but in recent years authors like Christopher Paul Curtis, Jacquelyn Woodson, Kwame Alexander, and Angie Thomas have published novels and stories that represent the experience of people of color. And yet, the best of these books don’t only represent the experiences of people of color. They also represent the human experience of suffering and heartache and betrayal and connection and love and joy.

In response to my original post, many of you offered further suggestions, and I thought of a few more myself. So here’s an additional list of mirrors and doorways for us all:

Picture Books:

God’s Very Big Idea by Trillia Newbell

Last Stop on Market Street by Matt de la Pena

And for older middle school and high school students:

House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros

Roll of Thunder Hear my Cry by Mildred Taylor

The Hate U Give and On the Come Up by Angie Thomas

Where the Line Bleeds by Jesmyn Ward

Song Yet Sung by James McBride

I also have book recommendations for adults in these previous posts:

Five Memoirs to Read Alongside White Picket Fences, and

Seven Non-Fiction Books I Recommend for (White) People Who Want to Understand Our Racial Divides.

(For more thoughts about representation in children’s literature, see Christopher Meyer’s article, The Apartheid of Children’s Literature, and Kwame Alexander’s short piece On Children’s Books and the Colors of their Characters.)

And keep the diverse book recommendations coming!

The post 7 More Diverse Book Recommendations & A Deeper Look appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

June 13, 2019

4 Simple Lessons to Stay Connected to Your Spouse

Peter and I have been married for 20 years this week. I am grateful in a way that words cannot convey for the ways we have grown up together. I’m not going to proclaim publicly the specific reasons I’m grateful for him, but I will offer four things that have helped us to stay connected to each other and also to grow into ourselves:

REORIENTATION

One, when we were still dating, we reoriented our relationship so that it wasn’t only about the two of us loving each other, but rather about the two of us rooted in a love that was deeper and wider and broader, more patient, more kind, and more everlasting than ours would ever be. (See Ephesians 3:14-21 and 1 Corinthians 13).

Also, I should note, this didn’t happen because we were super awesome spiritual people, but rather because I decided to walk away from our relationship and hang out with another boy for a while and when I came back to Peter we both knew we needed a deeper foundation for our relationship than each other.

We stopped allowing our worlds to revolve solely around each other and instead wondered how we might be called to love and serve others side by side and support each other in lives of love. That deeper love has sustained us, anchored us, nourished us, and connected us. That deeper love also has kept us from thinking that we have to save each other, be enough for each other, guide or lead each other, or perfectly love each other.

DATE NIGHT

Two, we have a weekly date night. I know. It’s hard. It costs money. Who has that kind of time? And how do you even find, much less pay babysitters? And there are so many other obligations, and the kids sometimes feel neglected, and do we even still have things to talk about after two decades? We’ve all been there.

But week after week, usually on Thursday nights, we make a reservation, get a little bit dressed up, and go out to dinner. It sounds romantic, and sometimes it is. Sometimes it’s routine–I hear about his meetings, his frustrations, his exhaustion. Then he hears about my meetings, my frustrations, my exhaustion. Sometimes it’s terribly painful–I end up crying regularly at those dinners, and he’s been known to shed a tear or two as well.

And yet the cumulative effect of valuing that time with each other more than any other recurring event has built a base of trust and support and love that has carried us through the tedium and the pain and has often offered us life and joy. (And sometimes evenings just won’t work, so we schedule another time together–lunch, a Saturday morning hike, a weekday morning walk.)

CALENDAR MEETINGS

Three, we have a weekly(ish) calendar meeting. We sit down for an hour once a week and talk about who is driving William to soccer practice and how Marilee will get to sleepaway camp this summer and whether Penny can have an iMessage account so she stops texting people from my phone. We talk about our finances and when the garage is going to get cleaned out and how much to spend on outdoor furniture. That way all that stuff doesn’t overtake date night, and our five minutes of seeing each other in between shuttling children hither and yon in the evenings doesn’t become the only chance to schedule things or ask who will take responsibility for whatever chore/errand/task needs doing.

PROTECT SUNDAYS

And finally, we protect Sundays. It took us years to settle into this rhythm, and now our bodies, minds, and spirits expect a respite from the busy of the week. These days are almost embarrassingly simple. We go to church in the morning. We eat lunch as a family. Peter takes a nap and the kids and I read. We go for a family walk if it’s nice and play a game if it’s raining or cold. We sometimes have a full family meeting (at least once a month), which includes items various family members have flagged for discussion and giving out allowances. We always take a quick look at the week ahead. We eat dinner. We go to bed.

Peter and I have an imperfect marriage now, and the same will be true in another twenty years. But we have established some practices that have helped us grow along the way. And we have been sustained and nurtured by a deep, abiding, perfect love, a powerful love that comes from outside ourselves and yet connects us to each other all the more.

The post 4 Simple Lessons to Stay Connected to Your Spouse appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

June 5, 2019

Trying to Expand Your Bookshelf? Here Are 20 Diverse Books for Kids of All Ages

Four years ago, I was working on a book about children’s literature. I loved the experience of reading out loud to our kids, especially reading chapter books, and I wanted to write about it. It seemed like a sweet and safe topic–the friendship that develops between parent and child through a shared story, the power of story to communicate truth across time and place, the learning that happens without feeling like instruction. I researched Beverly Cleary and E.B. White. I reread classics from my childhood. I recorded interactions with Penny and William and Marilee as we read together.

But over time, that sweet and safe topic began to feel more complicated. I noticed my own assumptions about parents having time and ability to read out loud with their kids. I noticed the fact that the gift of reading had been passed to me by my own parents. And I noticed the whiteness of the books on my children’s bookshelves.

This safe and simple story about reading became a very different book (aka White Picket Fences), albeit a book that still talks about the problems and possibilities of reading out loud to children. And perhaps it is because of these beginnings that I get asked regularly for a set of recommendations for children’s books with diverse characters and experiences.

I recommend two websites for a broad list of these types of books– The Brown Bookshelf and the American Library Association’s Coretta Scott King Award list.

But I also thought I would offer a few specific suggestions from our own family as we head into the summer:

(It’s worth noting that many of these books are written and illustrated by white people, which underlines a historical problem in the publishing industry. First, there’s the problem of not representing non-white experiences on the page but then there’s the problem of only employing white people to offer those depictions and stories. I’m still working to expand our bookshelf not only through representation on the page but also through a more diverse array of authors and illustrators.)

For the very little ones, board books like Everywhere Babies are terrific because they offer visual representations of diverse children and parents.

For pre-school age kids, of course there are classics like The Snowy Day and Corduroy, but also more contemporary depictions of everyday life like Dancing in the Wings by Debbie Allen and Jennifer Grant’s Maybe God is Like that Too and Maybe I Can Love My Neighbor Too.

For early elementary picture books, our favorite is The Story of Ruby Bridges, which is both a hopeful story and also a hard one as it details the hateful discrimination experienced by a young child going to school. Marilee also really likes Each Kindness by Jacqueline Woodson, a picture book about a group of girls who aren’t kind to a new girl in school.

For early elementary chapter books, we also enjoyed The Birchbark House by Louise Erdrich, a story set around the same time period as the Little House books, but this time told from the perspective of Native Americans. We also read Song of the Trees by Mildred Taylor, about a black family in the Jim Crow south struggling to retain ownership of their land in the face of white opposition. And we recommend many of the biographical books in the “Who Was?” series, including Harriet Tubman, Martin Luther King, Michelle Obama, Barack Obama, and Frederick Douglass.

For later elementary school, William particularly enjoyed John Lewis’ graphic novels about the Civil Rights movement (three volumes, all called March), Letters from a Slave Girl, a fictionalized account of Harriet Jacobs’ experience of growing up as an enslaved person in Edenton, North Carolina (my home town) and then hiding for seven years in an attic crawl space before finally securing her freedom. We’ve also liked Laurie Halse Anderson’s Chains, about an enslaved girl in the northern states during the time of the revolutionary war. I’ll note that with many of these books, our kids haven’t wanted to read them on their own, but they have happily listened as we’ve read them out loud and discussed them together.

And for middle school, so far I recommend the classic Roll of Thunder Hear My Cry by Mildred Taylor and the more recent Refugee by Alan Gratz.

I’d love to expand my own list of books for our kids! If you have any personal favorites or suggestions, please share in the comments below!

Also, if you are looking for adult books, here are 4 books I love about our common humanity, as well as 7 Non-Fiction Books I Recommend for (White) People Who Want to Understand our Racial Divides.

The post Trying to Expand Your Bookshelf? Here Are 20 Diverse Books for Kids of All Ages appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

May 29, 2019

How Do I Figure Out Where To Go?

On my run a few weeks ago, I was thinking about how I am in a period of “figuring out what I want to do next.” The book tour for White Picket Fences has ended, with a sprint through April and then talks at the Summer Institute on Theology and Disability and the headquarters of Christianity Today. I have ideas for another book. I have thoughts about creating video, podcasts, curriculum, and conferences. I know my website could use some improvements. I know my social media “look” could be more consistent. And so it is easy for me to think exactly what I thought that morning: I need to figure out what to do next.

Thankfully, as quickly as I heard that thought, I heard another. “Or,” this other voice seemed to say, “I could look for where God is leading me next.”

Right. You lead. I follow.

This is what I want, but I forget that I want it. I forget that I’m not alone. I forget that it’s not all about me. I forget that it takes attentiveness to the gentle whispers and motions of the Spirit in order for me to know where to go. And I forget that following where God leads doesn’t guarantee that I will know where I, where we, are going.

I’m still doing the practical work of seeking out help about next steps. I’m talking with people who do marketing and brand development and others who design websites. I’m reading books and brainstorming about writing and video and audio. I’m considering different funding models for the work that I do.

But what struck me as I ran was that far more crucial than the proper marketing strategy is staying close to the Spirit. Listening, and watching, and waiting.

We talked in our Bible study last week about following Jesus, and I asked what it means to follow someone. In our social media culture, following can simply mean we notice what someone is doing out of the corner of our eye. We keep tabs on that person. We push a button with a heart on it every so often and keep the image of their endeavors in the background of our mind.

But following can also mean something really different, in which we place our trust in someone else and allow them to lead. In which we notice what they are doing and seek to do it in turn. In which we stop when they stop and go when they go. In which we stop insisting on the destination and attend to the next step on the journey.

I want to follow the Spirit in that way. With attentiveness. And patience. And trust.

When I try to figure it out, I feel panicked inside. I am aware that there will never be enough time, that I will never know how to reach enough people, that I will never have enough marketing prowess. But when I stop trying to figure it out, when I stop to listen to the Spirit, you know what I hear?

I hear, “Love is patient.”

I hear the 23rd Psalm, and I notice the progression of thought.

First, “The Lord makes me lie down in green pastures.” An insistence on delightful rest.

Second, “He leads me beside the still waters.” An invitation to more rest, more peace, more patience.

Third, “He restores my soul.” Yet again, rest, restoration, peace, exhalation, quiet, patience, love.

And only then: “He leads me in paths of righteousness for His name’s sake.”

Only once I have lay down in the grass, enjoyed the peaceful waters, received the gift

of abundant and restorative life, only then is it time to follow on the path of righteousness.

I do not want to generate content and create a brand and establish a name for myself.

But I do want to participate in this abundant and life-giving work that God is doing.

The most important time for me each day has become a time of listening prayer. Sitting cross-legged with my eyes closed, breathing deeply, and envisioning myself lying in a field of grass, hugging my knees to my chest by the shores of a placid lake, cuddled up in the lap of a God who loves me. Trusting that whatever comes next can emerge out of rest and patience and love, not from having it all figured out.

I want to become attentive to the shepherd’s voice.

I want to notice where the Spirit leads.

And without even having to think about it, I want to follow.

The post How Do I Figure Out Where To Go? appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

May 15, 2019

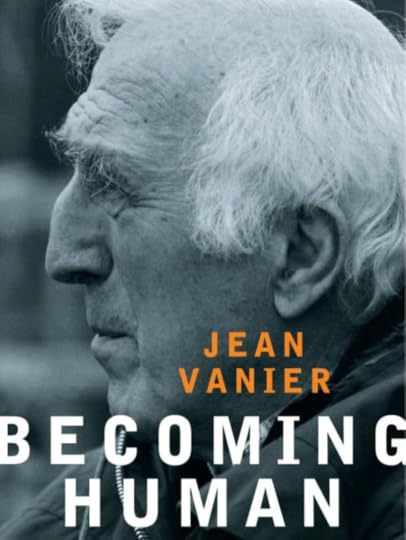

Love Is Patient: In Memory of Jean Vanier

“Love is patient.” This simple statement has been on my heart and mind this past week after I learned of the death of Jean Vanier, the founder of the L’Arche communities.

L’Arche is an organization in which people with intellectual disabilities and typical people lived side by side in community, and Vanier wrote about the ways in which these spaces of belonging and friendship (and sadness and suffering and arguing and forgiving and loving and laughing) stand as signs. He wasn’t an idealistic dreamer who thought that the “success” of L’Arche was dependent upon everyone living in intentional loving communities. Rather, he saw these communities as visible manifestations of what God looks like, what love looks like. Glimmers of light for those who had eyes to see.

Vanier wrote many books, and I have read many of them over these past thirteen years of being the mother of a child with a disability. The strange thing about these books is that I often don’t realize that I’m learning anything until I walk away from them. Vanier’s simple prose and simple stories often leave me waiting for the drama or for the brilliant insight that never comes. And yet, every time, I am changed by what I have read.

I look back on the places where I underlined sentences in Vanier’s bestselling book, Becoming Human, and I start to realize how much his patient and gentle words have taught me. To cite a few:

“We human beings are all fundamentally the same. We all belong to a common, broken humanity. We all have wounded, vulnerable hearts…” (37).

“The discovery of our common humanity, beneath our differences, seems for many to be dangerous. It not only means that we have to lose some of our power, privilege, and self-image, but also that we have to look at the shadow side in ourselves, the brokenness, and even the evil in our own hearts and culture; it implies moving into a certain insecurity” (49).

“It is not just a question of performing good deeds for those who are excluded but of being open and vulnerable to them in order to receive the life that they can offer; it is to become their friends” (84).

Over and over again, throughout his many books and speeches, Vanier comes back to love. Love as the basis of all reality. Love as the deepest human need. Love as the greatest gift, the one gift we are all capable of giving to one another.

And love, Paul writes in 1 Corinthians 13, is patient. Love waits. Waits in suffering. Waits in rejection. Waits in anticipation. Love is willing for “progress” to take time. It is willing for time to move slowly. Living among people with intellectual disabilities taught Vanier about the patient, tender, hidden nature of love.

I am only beginning to learn the nature of love. I am far more often impatient. I want problems to be fixed right now. I want to accomplish everything on my to do list today. I want efficiency and speed. But God offers us a different way, a way that is slow and gentle, a way that waits with patience, a way that is more often visible in the lives of people with disabilities than in typical people like me.

A few months ago, a group of faculty members at a Christian college asked me what I would recommend as they tried to have conversations with their students about privilege and racism. I recommended Jean Vanier’s books and the theology of disability. In order to understand privilege and racism and all the barriers that divide us, we need to first understand our humanity, and Vanier’s work is an invitation into an understanding of common humanity.

In a series of talks between Vanier and Stanley Hauerwas, collected in a book called Living Gently in a Violent World, Vanier writes, “The mystery of people with disabilities is that they long for authentic and loving relationships more than for power. They are not obsessed with being well-situated in a group that offers acclaim and promotion. They are crying for what matters most: love. And God hears their cry because in some way they respond to the cry of God, which is to give love.”

Jean Vanier slowed down and learned how to love. He lived that love. He wrote about that love. He received it, and he gave it away.

PS. I share more about Becoming Human in this post.

The post Love Is Patient: In Memory of Jean Vanier appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

May 9, 2019

How to Talk with Your Children (and Friends) about Faith Pt. 2

Years ago, I wanted to pray for some friends of ours, a married couple who had a great interest in spirituality but who hadn’t landed in any one particular faith. I wanted them to get to know Jesus. I thought that relationship would bless them and delight them and that they would experience the fullness of God’s love for them and their purpose in the world by coming to know Jesus personally. I still believe this is true.

And yet I also felt icky praying for them, and I couldn’t figure out why.

Eventually I realized it was because I was praying with an attitude of superiority. I had cut myself off from my friends in my heart, as if I had something to offer and they had nothing to give. Once I realized that attitude, it didn’t change my desire for them. I still wanted them to know Jesus, and I still prayed for that. But I was able to pray with a posture of receptivity, with a desire to see their particular gifts and to receive those from them, whether or not we ever shared the same faith. I started to assume not only that I had something to offer but also that I had needs that they could meet, if only I would approach them with humility and love.

Over time, I’ve come to understand that God has made us as people who are designed to give and receive love. I’ve come to understand that love is not coercive but receptive, not insistent but invitational. I’ve come to learn that love is relational.

Jesus models the way of love in his interactions with people in all sorts of ways, but one primary way he models love is in the way he talks with people. He doesn’t shy away from what he knows to be true. He isn’t afraid of offending people. He isn’t reluctant to teach, but he doesn’t need to win arguments or convert people to his way of seeing. He operates with humble confidence. And he does this largely through questions.

I haven’t taken the time to do the counting myself, but I’ve heard that Jesus asks 307 questions over the course of the four books of the Bible that contain stories about him, and 183 questions are asked of him. Nearly 500 questions go back and forth between Jesus and the people around him.

According to James Danaher, Jesus only offers direct answers to 3 of those questions.

Jesus hardly ever offered direct answers, and yet he was argu

ably the best teacher and guide into a relationship with God who has ever lived. What can we learn from him?

I wrote a post last week about how understanding ourselves as children of God will help us to have conversations with our own children about faith. Today’s post is part two, and here I want to suggest that asking and receiving questions is also central to having meaningful and long-lasting conversations with our kids (and anyone else for that matter) about faith.

We can take Jesus’ way of talking about faith–in the form of questions, in ongoing discourse that opens up relationships rather than commandments, in loving exchanges–and we can follow his gentle, confident way as we talk with our kids.

We don’t need to have all the answers. We don’t need them to understand everything all at once. We don’t need to force belief upon them.

Jesus invites us to love our kids by asking questions, by taking their questions seriously, and by walking together in love.

On a practical note, I’ve recently found a guide to Faith Conversations that might be helpful to you, as it poses four sets of questions we can ask our kids. Then again, it might not be helpful because these questions can be tough even for me to answer. “When did you feel God’s love today?” is one of the questions, for example, and that can be a bit abstract for all of us. And yet when we think about what Paul tells us about what God’s love looks like: patient, kind, forgiving, or about what the fruit of God’s Spirit looks like: lov

e, peace, joy–then that abstraction becomes a little more concrete.

So perhaps begin by asking, “When did you feel peace (or love, hope, joy) today?”

What if every time we feel love, joy, and peace, we are feeling God’s presence? What if every time we give or receive forgiveness we are participating in God’s work in the world? These are the types of questions that guide me toward seeing God in unexpected corners of my day. I hope that’s true for our kids too.

I’m going to offer 5 other ways to put these ideas into practice in my newsletter next week. If you’re interested in thinking more about how to talk with your kids (or friends) about faith, you can sign up for my newsletter here.

The post How to Talk with Your Children (and Friends) about Faith Pt. 2 appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

May 1, 2019

How to Talk with Your Children (and Friends) about Faith Pt. 1

“I’m just not interested in the Bible,” Penny said a few weeks ago.

“I will never understand how evolution and creation can both be true,” William has told me more than once.

“Why didn’t God light up my darkness?” asked Marilee, at the end of a day of fighting with her siblings without any reconciliation.

I’ve felt the same way as each of our kids at times. I’ve asked those questions and many more. I’ve been to seminary and read tons of books and studied the Bible and taught about these things. I’ve been a “professional Christian” for many years, and still I often feel like I can’t give my kids the guidance they need to express doubt and encounter God personally.

I’ve learned that having the right answers isn’t the key to talking about faith. But understanding myself as a child before God, and modeling the way of Jesus in conversation has helped to keep those doors for conversation open.

Jesus is surprisingly insistent that his disciples understand themselves as children of God. First of all, Jesus refers to God as Father almost exclusively. While other Jewish people in his time would have referred to God as Creator or Master of the Universe, and while the Old Testament Scriptures are filled with references to God as Lord, Judge, and King, Jesus repeatedly calls God Father. He tells story after story in which God is portrayed as a loving parent (see, for example, Matthew 7:7-11 and Luke 15:11-32). He instructs his disciples to refer to God as “Our Father” whenever they pray. After his resurrection, he invites them once again to think of God as their shared Father.

Jesus also refers to his disciples as children, little ones, over and over again. He even goes so far as to say, “Unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 18:3).

In other words, according to Jesus (and later, Paul picks up this language as well), the primary way for adult humans to understand their relationship to God is as little kids. The primary way to understand God is as a good and loving Father (and yes, there are all sorts of potential patriarchal and misogynistic problems that could be explored here, but Jesus’ point was to suggest the intimate love and acceptance God has for God’s children).

In our household, my children have grown up with a dad who is also the headmaster of a school. Their dad has a role which includes the authority to fire employees and to expel students. As a result, many teenagers and grownups in our community are on their best behavior when they encounter my husband. They interact with him in his role as headmaster.

He is no less a headmaster when he walks into our home at the end of the day. He’s still wearing his jacket and tie, still holding all the authority he had when he left the office a few minutes earlier. But our kids do not relate to him as a headmaster. They relate to him as a father. As a result, they complain to him. They ask him to wrestle with them, snuggle with them, create secret handshakes, and dance to Taylor Swift with them.

Jesus invites all of us to come to God as children. Yes, in dependence and need. But also to come with a knowledge of God’s deep acceptance and love and care for us.

When a baby takes her first steps and topples over–how does her dad react? Does he point out the fact that she didn’t even make it a few feet across the room? Does he berate her for not working hard enough or not getting it right? Not at all. He cheers. He helps her back on her feet. He gets out the phone to record the next attempt. What if God does the same for us?

What if what we perceive as our bumbling attempts through life bring God a smile as he sets us on our feet again?

For us to have conversations with our children (or anyone else) about faith, we need to remember that we are first and foremost children ourselves before God. We won’t get it all right. We will fall down plenty. But we can also rest assured in the security of God’s love for us– and that love will free us up to admit our own doubts, receive the questions and thoughts of our kids, and invite them to find their own place in the family of God.

This post is part one in a two part series. Next week I’ll write about how modeling Jesus’ way of conversation helps us to have conversations about faith. And then–right around Mother’s Day– I will send a newsletter offering 6 ways for parents to talk with their kids (or other people) about faith. If you aren’t already a newsletter subscriber, you can sign up here .

The post How to Talk with Your Children (and Friends) about Faith Pt. 1 appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

April 17, 2019

Rethinking Disability

One of the reasons we travel to cities as a family is simply for the experiences our kids have walking through the streets of highly populated areas. They’ve grown up in the country–with the Shepaug river in closer proximity than the nearest stoplight. They don’t know the smell of the city. They don’t know the press of people or traffic at rush hour. They don’t know the needs that become more visible in cities. They don’t know the diversity that becomes more visible in cities. We want to introduce them to the pain and the beauty of humanity, and cities are one way to do this. (I’m reminded of what Tim Keller reportedly said—that there is more of the image of God smashed into one New York City subway car than the entire Grand Canyon…)

So when we were in Washington, D.C. last month for a short spring break trip, I wasn’t surprised by Marilee’s questions: “Why is that man holding a sign saying he’s hungry?” “Is that lady with lots of bags homeless?” “Why are there so many police cars?”

But then she asked, “Isn’t it sad that man is in a wheelchair?”

I looked ahead and saw a man wheeling himself down the street with a friend walking next to him. He didn’t look sad. He didn’t look like he was in pain.

So I said, “I actually think it’s pretty cool that man has a wheelchair that can help him get around.”

She wrinkled her forehead.

I’m pretty sure I know what she was thinking.

“Marilee,” I said, “I don’t feel sad that you have glasses.”

Her forehead stayed wrinkled.

“In fact, I feel happy that you have glasses because they help you see clearly. And I can’t say for sure how he feels about being in a wheelchair. But right now he doesn’t look sad, and it doesn’t look like he’s in pain, and it looks like he’s getting where he wants to go with his friend.”

Ah. She nodded slowly.

“You mean, my glasses are like wheelchairs for my eyes?”

Yes.

Scholars write about the “social construct of disability”– all the ways that our society teaches us to understand both physical and intellectual disability as categorically negative, and even tragic. The old way of signifying parking spaces for people in wheelchairs exemplifies this view, with a static image:

The new icon of an empowered person in motion in a wheelchair reflects a new understanding of the possibilities inherent for people in wheelchairs:

Even still, reporters will refer to people who are “confined” to a wheelchair rather than using more neutral language like “using” a wheelchair, just as they will write that children “suffer from” Down syndrome rather than “live with” Down syndrome.

The language we hear and the images we see reinforce and even help to shape what we believe is true.

It’s now a month later, and I just asked Marilee for permission to tell this story. Her face lit up at the thought of being included in something I write. But she also said, “you mean that time when I learned glasses are like wheelchairs for my eyes?” It was a small moment and a subtle shift of perception that might help her—and me—to see the world more clearly.

The post Rethinking Disability appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

April 10, 2019

Participating in Love

A few weeks ago, I was giving a series of talks about the love of God to a group of women in Ocean City, New Jersey. The talks had a natural progression with straightforward titles: The Love of God as the Foundation of Reality, What Keeps Us from the Love of God?, Receiving the Love of God, and Giving God’s Love Away.

The main points were fairly obvious:

Love is real and present.

We are separated from it.

We can, however, receive it into our lives.

Then we are invited to give it away.

But as I was in the middle of speaking during the final talk, I realized that I disagreed with my own title for two reasons. One, when we give something away, it implies that we don’t have it anymore. But that’s the mysterious beauty of the love of God. It is so abundant, so “high and long and wide and deep” (as Paul reflects in Ephesians 3), that we can offer to others love that overflows. We aren’t sucked dry as we give love away. In fact, if we are sucked dry it means we are giving of ourselves, not of the endless and eternal source of love that God provides. (And if you find yourself in this place—which I do, often—let it be an invitation to return to the source of love and receive that love all over again.)

Two, to say that we “give away” God’s love makes the action seem one dimensional, but one of the wonders of love is the possibility of reciprocity. I give help and care to someone without any openness as to what I might receive from that same person. That’s not love. That’s pity in disguise. One-dimensional love allows distance and superiority to remain in place between the two parties.

In other words, when I got to that final talk, I wasn’t really reflecting on giving love away. What I was really talking about was participating in the love of God.

If love is the foundation of all reality, as the various writers of the Biblical books declare, then the more we access that love and participate within it, the more we live in reality, the more we connect with our true selves, with God, and with others. The more we say yes to healing and light and goodness all around us.

When we participate in God’s love, we receive it and offer it to others, and this cycle repeats and loops around and enfolds us in an eternal embrace.

I’ll be sending an email only to newsletter subscribers later this week that offers 5 ways to receive God’s love. If you’re looking for an endless source of love that equips you to know yourself as beloved and to love others, sign up to receive my newsletter now.

The post Participating in Love appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.