Amy Julia Becker's Blog, page 141

February 1, 2019

White Picket Fences Discussion Guides Are Here!

“Are you going to tell me I have to sell my house?”

“How should I respond when people tell me I am a burden to society?”

“The word privilege doesn’t come up in the Bible. Why should Christians be talking about it?”

“What’s the relationship between being generous and believing in reparations?”

“Should I be ashamed of being a white man?”

Over the past few months, I’ve been traveling around to different schools, bookstores, and churches talking about the themes of White Picket Fences, and these are some of the earnest questions I’ve received. In every location, people haven’t simply wanted to talk about the book. They’ve wanted to talk about their own lives, their own communities, and the possibilities for their own engagement with the social divisions we see in our culture right now.

In other words, most people want to do more than read this book. They want to talk about it. Moreover, they want to respond to it with more than conversation. They want to participate in meaningful change. Are you one of them? (Sign up here.)

People who have never attended a book club before, people who aren’t already in a small group, people from all walks of life–men and women, old and young, north and south, black and white– feel a need right now to engage with the social divisions in our culture. White Picket Fences offers a place to start.

In addition to ongoing blog posts and other supplemental materials at amyjuliabecker.com, we have put together two discussion guides, one for a group that will meet one time, and another for three meetings. (We are also working on a 7-week discussion guide for Lent which will be available in mid- February.)

All of these guides will lead participants through a three-step process of response to the content of WPF including:

Responding with your Head: acknowledging of the problems and wounds associated with privilege

Responding with your Heart: connecting spiritually, emotionally, and relationally with the problems of social division

Responding with your Hands: actively participating in healing in your own life and community

Over the course of this next year, we will be creating additional materials to correspond with each of these three steps, and we will send a monthly email to inform you about these new resources.

If you are ready to gather a group to read and reflect upon White Picket Fences , sign up here .

Once you sign up:

We will email you the discussion guide you requested (which includes guidelines for forming a group and establishing norms for conversation within the group)

Once you have established a date for your group’s meeting, you are invited to set up a 30-minute video call with Amy Julia individually or as a group. (For at least the first 50 people who sign up)

You will be invited to join a private Facebook group of other discussion leaders .

Many people in our culture are concerned about the harm inflicted by privilege. Reading White Picket Fences and talking with others about it offers hope that a meaningful and loving response is possible. Thank you for taking one small step towards healing.

The post White Picket Fences Discussion Guides Are Here! appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

January 25, 2019

Brian Allain: Why I Started Publishing in Color

Many people are troubled by the social divisions in our nation, and many people want ways to respond to these divisions. I’ve written about the need for holistic and lifelong responses that involve our heads, hearts, and hands , and I will continue to write about all of these aspects of responding to the pain that continues to divide our nation. In addition, over the next few months, I’m going to offer reflections from a few people on how they have responded to the reality of their privilege on either an individual, influential, or institutional level. I asked my friend Brian Allain to share here today about how he used his influence to connect writers of color to a predominantly white publishing industry. I hope you’ll appreciate his story. I also hope you’ll use it as a way to consider where you could use your own influence in your own community.

Why I Started Publishing in Color

It was a long journey to get from working as an engineer at Bell Laboratories to putting on spiritual writers conferences!

I worked in many different communication technology businesses, both large and small, and enjoyed them immensely. Twice in my life I considered going into ministry, but in both cases I ended up concluding that it was not the best fit for my skill set. I think I could come up with a grand total of one good sermon in my entire life.

Then what literally fell in my lap was the opportunity to establish and lead the Frederick Buechner Center. I didn’t go looking for it; I didn’t apply for the job. It found me. What an amazing blessing! Then two years ago when I turned 60, I asked myself how I wanted to spend the rest of my productive time on this planet. I decided to start Writing for Your Life in order to help other spiritual writers.

I needed to gain some contacts in the Christian publishing industry in order to establish these new writing workshops, so I attended an industry conference where a panel of CEOs from Christian publishing houses took place. An African American woman in the audience asked them why they didn’t publish more books from people of color. All the executives on the panel basically said the same thing: “We realize it is a problem; we just don’t know how to solve it.”

Throughout my business career, I’ve seen time and again how important “who you know” is, or really “who knows you.” I am not a publisher; I cannot force books to happen. HOWEVER, I thought to myself, I CAN put together a conference that fosters relationships between writers of color and representatives from the publishing industry. I ran the concept past a few authors of color and publishing industry people whose judgement I respected. They all thought it was a great idea.

Thus far we’ve held two Publishing in Color conferences and they’ve been very well received. You can read some of the comments from attendees here. Between the two conferences we’ve had over 200 attendees and speakers. Several book deals, agent relationships, and article invitations have already taken place as a result. Additional Publishing in Color conferences will take place this year in Los Angeles and New Jersey.

Judging from the feedback and results, it’s a good thing. We’ve all been blessed.

Profits, if any, from the Publishing in Color conferences go into the Publishing in Color Scholarship Fund so that selected scholarship recipients can attend future conferences at no charge. If you would like to contribute here that would be greatly appreciated!

Brian Allain

The post Brian Allain: Why I Started Publishing in Color appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

January 18, 2019

Can My Little Efforts Make Any Difference in an Angry and Divided World?

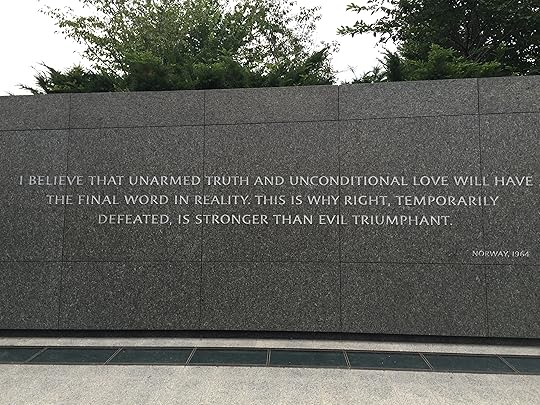

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial in DC

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial in DCJanuary brings with it the promise of change: all those New Year’s resolutions and 365 days to implement plans and hopes and dreams of a better future. Three weeks in, and we find ourselves reflecting on the life and legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr., a man who proclaimed a vision of change before our entire nation, a vision many of us have longed for, a vision of justice, compassion, and unity amidst diversity that even still seems out of reach. There’s a gap between King’s rhetoric and our day to day reality, a gap between what we desire and aspire to and how we actually live. According to US News and World Report, 80% of New Year’s resolutions fail. And those are goals we set for ourselves, not lofty aspirations for our entire nation. Still, psychologists have studied the reasons our resolutions fail us and what we can do instead. One way to affect change is to start small.

To give a personal and mundane example, a few years ago, I decided to wake up 20 minutes earlier than usual one morning each week to work out. I had been gaining weight, feeling lethargic, and longing for change. I decided to take one small step.

I won’t bore you with the details, but that first step towards health eventually led to a regular early morning workout. Then it led me to consider how I was eating. Eventually, I reduced my alcohol consumption. I increased my fruits and vegetables. I eliminated Diet Coke, which had been my drink of choice for decades. I lost weight. I gained strength. I slept better. I felt happier. It all feels habitual now, but it took years of small steps that became like dominoes. One barrier fell and hit another and another and another until the entire edifice had been leveled.

Sometimes change happens dramatically—with a catastrophic health event or a sudden revelation or revolution. But sometimes change happens in small, gradual, steps that build upon one another and almost unwittingly bring us to an entirely new place.

I have never marched in support of a cause. I haven’t read all the books I could read or taken all the classes I could take to learn about injustice. I haven’t given away as much money as I could. I don’t work for a non-profit. I have never visited someone in prison. I live in a predominantly wealthy, white community. I haven’t even been an active member of our public school’s PTA.

But here’s the thing. A few years ago, I noticed that the chapter books we were reading to our kids were filled with white characters. It bothered me enough that I took the small step of going to the library, and our bookshelves started to change. That little decision led to conversations with friends who are people of color that led me to change the way I talk with our kids about the news. It led to conversations in our household about whiteness and about the ugly aspects of our nation’s history that we probably wouldn’t have had otherwise. It led to planning a spring break trip to the African American History museum in Washington, D.C. It led to writing a book about the wounds of privilege and the hope for healing.

At the start of a new year, we can resolve to be better people—lose ten pounds, read 100 books, solve the world’s problems. Most studies show that almost all of us will fail in our lofty goals. But we can also decide to take one small step towards goodness, truth, and light, one small step towards generosity, humility, and hope. Small steps, in fact, may be our very best hope in overcoming anger, fear, and shame with hope, truth, and love. As we honor the dream of Martin Luther King, Jr. this year, let us take small steps towards making that dream a reality.

The post Can My Little Efforts Make Any Difference in an Angry and Divided World? appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

January 10, 2019

Five Memoirs to Read Alongside White Picket Fences

Last night, Natasha Sistrunk Robinson, author of A Sojourner’s Truth: Choosing Freedom and Courage in a Divided World, and I read passages from our respective memoirs side by side at Trinity Presbyterian Church in Herndon, Virginia. We read and spoke about two very different life experiences–she as a black woman growing up in a hardworking household that struggled to get by in South Carolina, I as a white woman growing up with all the opportunities handed to me through wealth and whiteness and educational opportunities. Natasha’s story is well worth reading in and of itself. She not only tells of her own journey through success (Naval Academy, Marine Corps, working for the Department of Homeland Security, seminary, founding a non-profit, becoming an author…) and suffering, but she does so in conjunction with the story of Moses and the people of Israel in Exodus.

Reading these books together forces a comparison between our experiences. We have much in common–we are both women of faith who grew up in the south with loving parents and strong and supportive communities. And yet the social divisions of race and class also permeate these stories of two woman who are both asking what it means to pursue the ideals of truth and love and grace in a broken world.

I’m working on a discussion guide for groups who want to read White Picket Fences right now (my next post will tell you more about that and offer an invitation to participate).In addition to Natasha’s book, here’s a list of four others that could serve as companions for discussion:

I’m Still Here, by Austin Channing Brown. Another powerful memoir by a black Christian woman. Brown attended independent schools, so her book also gives a look at being black in predominantly white spaces. Brown is a terrific storyteller and makes it easy for a reader to enter into these pages. While this book offers a piercing critique of white culture, Brown also writes that she stands in the “shadow of hope” as she looks towards the future.

Becoming, by Michelle Obama. Yes, it feels very presumptuous to suggest reading a book by the former First Lady of the Unied States alongside my own story! Still, the contrast in what it took for Obama to receive the education she deserved and end up at Princeton University brings up disparities in educational opportunities in America as a whole. It’s also well written and honest and offers a window on the challenges and possibilities we face.

Men We Reaped, by Jesmyn Ward. I’m a big fan of Jesmyn Ward in general (her other books are novels, two of which have won the National Book Award). Her memoir focuses on five men in her life who died over the span of a short period of time, and she offers the story of her own life growing up in Gulf Coast Louisiana as she narrates those losses. Ward also attended private school. She did well in school and left home for college and an eventual career as one of the most significant novelists of our time. She wrestles with the knowledge that she had opportunities so many others in her same social situation do not, and she wrestles with leaving and returning to her beloved hometown.

My First White Friend, by Patricia Raybon. This book is now twenty years old, so it doesn’t speak as directly to our present moment, but it remains a gentle and honest story of a black woman who grew up with the specter of overt racism and looked for ways to choose love and hope in the midst of it. Patricia Raybon is a friend and mentor of both mine and Natasha’s, and she wrote the foreword to both of our books.

There are plenty of other books that could be on this list (Real American by Julie Lythcott Hayes, Disunity in Christ by Christena Cleveland, which isn’t a memoir but could still offer a great conversation partner to WPF, Between the World and Me by Ta Nehisi Coates, which is worth reading for the struggle of encountering a story that refuses to be hopeful about the future in light of the ongoing injustice of our history and our present moment, Educated by Tara Westover and Hillbilly Elegy by JD Vance as examples of a very different white experience of American life), and then there’s a host of reading in the area of disability that I will put together for another post.

I offer these five for now, with gratitude for the way these women have shaped my understanding of the world and of myself, and in hopes that you too might find them helpful companions in entering into the hard truths of our past.

Last night, Natasha spoke about the “cognitive dissonance” that exists between the reality of our lives and the ideal of a life of liberty and justice for all. We talked about the natural responses to that dissonance: cynicism, anger, despair, bitterness, ignorance. But there is another option, which is to continue to insist that we can–with thought, and prayer, and love–move towards the ideal. We can face reality–and these books are one way to do so–while also longing for, praying for, and taking small steps of love towards a better world.

The post Five Memoirs to Read Alongside White Picket Fences appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

December 19, 2018

Silence, Solitude, Stillness, and…Sickness

I usually love Sunday mornings. I sleep until I wake up, and then I make a cup of tea and sit in front of the fireplace and read and journal and review the past week and eventually look to the week ahead. This practice usually gives me a sense of peace. I decide which mornings I’ll exercise and which nights we will all be home for dinner. I get a sense of where I have chunks of time to write. Then I make a plan and things fall into place.

Except that’s not what happened last weekend. Ten days ago, I sat down to plan the week, and I could feel my shoulders tightening with every item I added to the to do list. There was no way to make exercise, prayer, Christmas shopping, social events, and work fit into the hours available. The thought flashed through my head: “This would be a good week to get sick.”

For years, when I’ve felt anxious and overwhelmed, when warning signals have pinged through my consciousness because I have started to forget things, lose things, snap at our children and distance myself from Peter– I’ve pushed. In the past, the only thing that has stopped me is illness.

And here I was again. I invited a cold, and promptly received what I had asked for.

Except this time, I didn’t use it as a reason to climb under my covers and go to sleep, to avoid the parties and escape the obligations. Instead, as my head filled up with fluid, I thought about how sickness might not be the only way to respond to feeling overwhelmed. What if, instead, I had paused? Listened? Prayed? What if I decided not to get everything done, or decided not to attend a social event, or decided to simplify the shopping, or just asked God for help?

The sickness didn’t linger. And in the midst of my sniffles, I heard a podcast with Phileena Huertz and Andy Hale in which she talked about the disciplines of silence, solitude, and stillness. She mentioned that silence teaches us to listen, solitude teaches us to be present, and stillness teaches us when to act.

From the perspective of the church calendar, Advent is the perfect time for these three habits. From the perspective of a mom getting ready for Christmas, December is diametrically opposed to anything approaching contemplation. But for me, getting sick was an invitation to go back to Advent. To wake up and sit in front of our gas fireplace and repeat the words, “Be still and know that I am God,” and to offer all the restless activity and frantic doing to the babe in the manger.

Silence, solitude, and stillness. Invitations to receive hope, peace, and trust from the still small voice of love. May you hear that voice this season.

In keeping with this invitation, I’m going to be taking a break from blogging for the next two weeks. I look forward to seeing you again in the New Year!

The post Silence, Solitude, Stillness, and…Sickness appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

December 12, 2018

‘Tis the Season for Stress

I woke up at 4:32 this morning. I had set the alarm for 5:30, but my body seemed to think that would not do. There was the knowledge that American Girl orders had to be processed by today in order to ensure delivery by Christmas. There was the overflowing email inbox. There was the intention to exercise regularly throughout this season, especially after two nights in a row (and early on in the week, no less) with parties that involved two glasses of wine.

‘Tis the season for stress, and yet I also love this time of year. Yes, I love the lights on the trees and the scent of wood burning fires and the almond cake our neighbors send. Yes, I love the cards and music and festivities. Yes, I love Marilee’s elf pajamas and William’s Carol of the Bells on the piano and Penny’s desire to buy gifts for all her friends. But beneath it all, beneath the noise and lights and clutter and busyness, I also love the story of the baby in the manger, the story of God with us.

I’ve been thinking this year about what this phrase– God with us –actually means. It comes from the word “Emmanuel,” first mentioned in the Old Testament book of Isaiah, and later given to Jesus by Matthew. John hints at the same idea when he says that “the Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us.”

I have been thinking about how easy it is to pretend to be with other people. I pretend to be with our kids every time I nod as if I’m listening but wander away in my thoughts or allow my eyes to linger on my phone. In the years when we considered moving into a low-income, predominantly black neighborhood, I wondered whether in moving there I would be pretending to be with those neighbors, pretending to experience life in a different socio-economic sphere. I imagined transporting myself–with the furniture and paintings we’ve inherited from grandparents–into a new house and new location, and I wondered whether I would really be moving into the neighborhood or just pretending to be there and then heading off to the shore for a vacation with my family.

I remember hearing a story about a missionary who went to a leper colony in order to tell the lepers about Jesus. According to the story, it was only once that missionary contracted leprosy himself, only when he was truly with them, that he understood them, that they listened to him.

God with us. God not pretending, but actually living with us. Not going on vacation from being human. Not escaping the reality of poverty and discomfort and danger but fully immersing himself in human suffering and joy, learning and loving. God with us, from birth to death.

And so I get to the end of days that feel consumed by incidental stresses–wrapping paper and gingerbread houses and remembering to pay the life insurance bill–and I consider what it means for Jesus to be with me. In this. In the waking up early and the to do list and the food and drink. In the busyness and the stress and the delight of it. I pray for Christ to once again enter in to the humanity of my sleepless nights and my anxious days, to be with me where I am. And I trust that somehow, his presence will change me. He is willing to be with me where I am, but he also invites me to be with him where he is. He invites me out of 4:30 am wake ups and into rest, out of relentless to do lists and into peace, out of overindulgence and into joy.

The post ‘Tis the Season for Stress appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

December 5, 2018

Jesus Came From A Dysfunctional Family

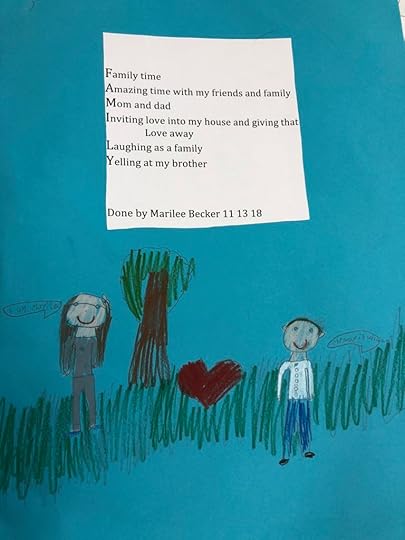

We had Marilee’s parent/teacher conference yesterday morning. We heard about her leadership in the classroom and the play she is writing with her friend Nathan. She’s kind to the other kids. She loves math. And she loves writing–especially acrostic poems.

At the end of our time together, her teacher pulled out one poem written to the theme of FAMILY. It begins as expected–sweet and happy, something any child of the 21st century might write and share on social media. As it continues, it builds to a crescendo of perfect-family-ness with the line “Inviting love into my house and giving love away.” I must admit my heart swelled when I read it, and I thought, Maybe we are doing something right as parents!

And then I read the conclusion: “Laughing as a family. Yelling at my brother.”

The end.

I love this poem.

Why? I love it because it isn’t the fake version of our family–I love it because it represents who we are. We are family that laughs and yells. We are a family that sometimes thinks nasty thoughts about other people. We are a family that prays for other people. We are a family with high ideals and expectations and also a family that recently watched the movie Major League together (definitely NOT one for the seven-year old!). We screw up sometimes, we get it right sometimes. We laugh. We yell.

Family is often on my mind this time of year. The time between Thanksgiving and Christmas is rife with decisions about which family members we want (or are obligated?) to see. For so many of us, going home for the holidays means walking back into old patterns of teenage petulance, codependency, resentment, and snarky remarks toward siblings. We laugh. We yell.

I’ve taken comfort in an unusual Biblical text as I’ve thought about our little band of dysfunctional human trying (and often failing) to love each other, love God, love our neighbors. As I wrangle with extended family about who is going where on what day, who is disagreeing with who about how the presents should be purchased, who is offending who by not staying long enough or staying too long, or who is worried about this person’s drinking problem and that person’s parenting and that one’s passive aggressive nature–in the midst of it all, I take comfort in Jesus’ family tree.

The Gospel of Matthew begins with a rendering of Jesus’ lineage that ends with Joseph. While this is a list of names I am tempted to skip past, I have been pausing to consider them and the truth they offer: Jesus came from a dysfunctional family. He emerged out of people who yelled at each other. He, light and life, came from people who betrayed one another, who had adulterous affairs, and who turned their back on God.

Furthermore, these weren’t just Jesus’ distant relatives. Jesus was born as an illegitimate son, to an unmarried mother, with a human father who had considered divorce. Jesus was born as an outcast from society, with parents who seem to have been cut off from their family. It seems likely that the rest of the clan thought Joseph and Mary were delusional, since they claimed that God himself had put a stamp of approval on what seemed to be Mary’s obvious sexual sin.

So in the midst of the intrigue and rumors, Jesus is born. Jesus, the one who will “save the people from their sins.” The one who fulfills the promise that God will be with us. God will be with us in the laughter and the yelling, in the sin and in the glory.

I take great comfort and great hope that Jesus can be born in our midst day after day. That light and life and salvation, good news for us and for all people, can enter into our dysfunction and pain, enter into our extended family’s dysfunction and pain, enter into our world’s dysfunction and pain. Advent is a season of waiting, a season of longing, a season of anticipation.

In the midst of the argument over who needs to sit next to Aunt Gertrude and listen to her stories, the pain over loved ones who aren’t here to gather around the table, the unhealthy decisions about food and drink, the glitz and glitter and spending too much and caring too much about appearances, Jesus promises to be God with us. He promises to welcome us, as we are, into the family of God.

If you are looking for more reflections like this one during this Advent season, sign up to receive my free Advent ebook here (scroll down to the bottom of the page).

The post Jesus Came From A Dysfunctional Family appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

November 26, 2018

A Note on the Terms in White Picket Fences

White Picket Fences addresses the topic of privilege, giving particular attention to race, class, and disability. I chose to use the term “African American” most of the time within these pages because studies show that white people implicitly associate the word “black” with negative ideas, whereas the word “African American” connotes more positive and respectful attitudes to a white audience. That said, I’m aware that “African American” is not nearly as descriptive or positive among the people it purportedly describes.

Many “African American” people choose to describe themselves as “people of color” or as “black” because these words demonstrate an affiliation with a broader spectrum of minority racial and ethnic groups and with people from the Caribbean. In addition, the term “African American” underscores an imbalance in our language (and our culture). Most people don’t use the word “European American” to describe white people, especially white people whose relatives have been in this country for generations. For “African Americans” and “European Americans” who have lived on this soil for hundreds of years, identifying us by our continent of origin many centuries ago seems anachronistic and imprecise.

Precise language poses a problem because it reflects a problem that already exists. Language can shape culture, but it also reflects culture. The past century has seen a progression of terms to describe non-white people, and the fact that no term quite works only serves to demonstrate the ongoing discomfort we have as a culture in figuring out the intersection of national identity and racial identity and personal identity and all the other ways we identify ourselves. A similar story can be told in looking at the language used to describe people with what we now call “intellectual disabilities.” White Picket Fences certainly doesn’t begin to solve the problem of language, but I hope to avoid contributing it.

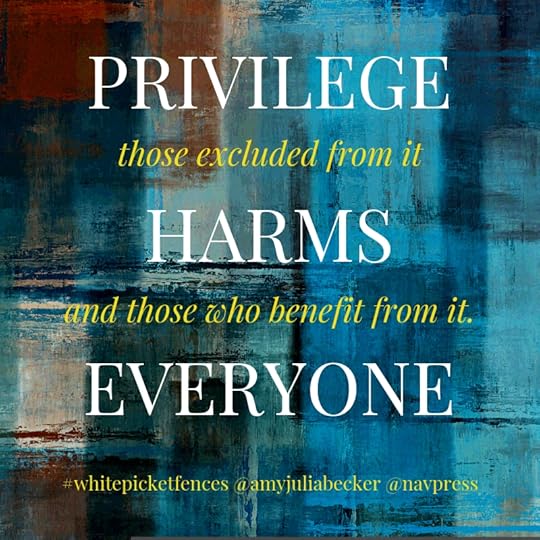

The other term that deserves some explanation comes up even in the subtitle of this book, and it is used throughout. The dictionary defines privilege as “a right, immunity, or benefit enjoyed only by a person beyond the advantages of most.” An online etymology search tells me privilege is a word that has been around for centuries, and it initially indicated a legal way one person had a leg up in comparison to another. Historically in America, whiteness has meant privilege, with laws that granted white men the right to vote, laws that decreed white people counted as full human beings while those of African descent did not, laws that dictated who could, and could not, marry. Even in more recent years, laws have made housing and education more available to white people than others. People in possession of powder cocaine (who happened to be far more likely to be white than black) received significantly shorter prison sentences than people in possession of the same amount of crack cocaine (far more likely to be black than white). These examples don’t even touch the ways in which the law is unevenly applied depending upon racial status—the statistics that demonstrate that skin color often correlates with who will be pulled over on the highway or at an intersection, the numbers that tell us white drug use is higher than drug use among African Americans and yet black men face incarceration over drug offenses at a much higher rate than their white contemporaries.

Racial inequity is a fact of American history and of American contemporary life. Still, whiteness is only one aspect of privilege. Some people use the word privilege to mean affluence, which speaks to the ways wealth can buy opportunities and education and access to work, all of which can translate into glorified social status. Wealth is often, but not always, associated with whiteness. Privilege still functions within our legal code, but it also functions as a social code, a code that offers membership to private clubs or schools or job opportunities only to those with certain cultural backgrounds or, sometimes, the ability to pay for admission.

When I write about privilege, I am writing about both the legal and historical meaning of the word and the social meaning. I have started to think of privilege as a Venn diagram of race, socioeconomic class, religion, and genetics (and various other factors) that both protects and constrains those who fall within its boundaries.

The post A Note on the Terms in White Picket Fences appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

November 14, 2018

Hope for Healing: Engaging with the Problem of Privilege

When I started to really engage with the problem of privilege, I wanted to figure out how to fix it. I studied the issues by reading books and listening to podcasts and watching documentary films. I prayed and even fasted and read Bible verses about mercy and justice. I talked with other people who shared my concerns. Eventually, I decided to write a book about it.

But if there is anything I have learned from thinking and reading and writing and praying about the reality of harmful and undeserved social divisions in our world, it is that this problem has no easy solutions. There are no quick fixes. No lists of action items to work through one by one. Rather, this is a lifelong work of transformation, a lifelong work of turning toward love and away from fear, a lifelong work of longing for all to be well.

Still, many readers have asked me what to do after reading White Picket Fences. How do we move from thinking about the harm of privilege into participation in the healing process?

In a subsequent post, I plan to write about people and institutions who have committed themselves to this type of participation, but I also want to explain my resistance to offering any sense that there are solutions to the problem of social division and privilege.

One, the attitude I have had in the past of wanting to “fix” things betrays an arrogance in me rather than a willingness to listen, to engage with the centuries of harm and exclusion, and to examine my own role in this harm.

Two, it implies that problems are solved by individuals in positions of power rather than through cultures transformed through relationships of mutual dependence. Our social divisions will only be overcome through collective and connected action that grows out of relationships of love, powered by a love that is bigger than any one of us.

And three, because action is the last step in a long process that will only be effective if it involves the whole self—the action, thoughts, and feelings—of the person involved.

Human beings consist of mind, body, and spirit. Put another way, of head, hands, and heart. All three of these aspects of who we are as humans need to be engaged in order for healing to happen.

The Head

We need to use our minds to consider the historical and contemporary reality of privilege—what it is, how it operates, who it excludes, and what damage it does. Engaging our minds can take the shape of reading books (yes, books like White Picket Fences, but also other memoirs and histories and works of sociology) and discussing them with others, listening to speakers, researching local history, and asking questions. Without this work of the mind, anyone engaging in the work of racial justice runs the risk of well-meaning but harmful and ignorant action.

The Heart

The “heart”—the seat of our emotions and the soul—needs to be engaged through relationships of mutual dependence. As a Christian, I see those relationships as both vertical and horizontal. There is the vertical relationship with God expressed through prayer: both the confession of corporate, historic, and individual sin, and the crying out to God for help in knowing how to participate in the work of restoration and repair. Then there are horizontal relationships, not relationships that perpetuate a power dynamic, but relationships that involve giving and receiving, recognizing our common humanity, trusting that each of us has gifts to offer and needs that only other people can fill. Without engaging our hearts, we run the risk of an arrogant approach to social problems that ignores love and perpetuates existing power structures.

The Hands

And finally, once the head and the heart are engaged, the hands can get to work and move lovingly into the world (more on what that might look like in a later post). But our actions in isolation run the risk of burnout or despair, action not grounded in a love outside ourselves, actions not connected to other people working towards the same end.

So my hope for myself, and for anyone who hears me speak or who reads White Picket Fences, is a patient and humble engagement with the issues of social division, starting slowly and quietly. Engagement that doesn’t rush to action but sits patiently and learns and listens, grieves and connects, asks for guidance, pursues friendship, and begins to trust in love instead of fear.

This is not charitable work of service or financial aid. This is not removed intellectualism that studies a problem without grieving the harm inherent in our history. This is not emotionalism that means well but accomplishes little. Rather, this is a work of body, mind, and spirit, of hands, head, and heart, of the whole self engaged in relationships with others and with God. It is lifelong, transformative work.

If you are someone who wants to participate in the healing work of social change, then let it take time. My hope would be that you would:

Use your head. Read White Picket Fences (and other books) and discuss it with other people. Learn about the historical and contemporary realities of racial, economic, and other social divisions in your communities.

Use your heart. Confess your role in the pain. Pray for guidance. Pursue friendships outside your typical social group. Look for a mentor who is a person of color. Look for a mentor who has an intellectual disability.

And then, use your hands: Take small steps towards change in your individual life. Look at areas in which you have influence or power and consider how you could use that influence for the common good, for breaking down social barriers, for healing. Connect with other people—through institutions and organizations—who are working towards justice and healing.

I will be writing more about all of these things and beginning to offer resources for engagement with these issues and topics. And I will be praying for each of our small choices to help us participate in this ongoing and lifelong work that changes us, makes us more dependent upon each other and upon God, prompts us to take risks to connect to one another, and moves us away from fear and towards love.

The post Hope for Healing: Engaging with the Problem of Privilege appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

The Head, the Heart, the Hands: Engaging with the Problem of Privilege

When I started to really engage with the problem of privilege, I wanted to figure out how to fix it. I studied the issues by reading books and listening to podcasts and watching documentary films. I prayed and even fasted and read Bible verses about mercy and justice. I talked with other people who shared my concerns. Eventually, I decided to write a book about it.

But if there is anything I have learned from thinking and reading and writing and praying about the reality of harmful and undeserved social divisions in our world, it is that this problem has no easy solutions. There are no quick fixes. No lists of action items to work through one by one. Rather, this is a lifelong work of transformation, a lifelong work of turning toward love and away from fear, a lifelong work of longing for all to be well.

Still, many readers have asked me what to do after reading White Picket Fences. How do we move from thinking about the harm of privilege into participation in the healing process?

In a subsequent post, I plan to write about people and institutions who have committed themselves to this type of participation, but I also want to explain my resistance to offering any sense that there are solutions to the problem of social division and privilege.

One, the attitude I have had in the past of wanting to “fix” things betrays an arrogance in me rather than a willingness to listen, to engage with the centuries of harm and exclusion, and to examine my own role in this harm.

Two, it implies that problems are solved by individuals in positions of power rather than through cultures transformed through relationships of mutual dependence. Our social divisions will only be overcome through collective and connected action that grows out of relationships of love, powered by a love that is bigger than any one of us.

And three, because action is the last step in a long process that will only be effective if it involves the whole self—the action, thoughts, and feelings—of the person involved.

Human beings consist of mind, body, and spirit. Put another way, of head, hands, and heart. All three of these aspects of who we are as humans need to be engaged in order for healing to happen.

The Head

We need to use our minds to consider the historical and contemporary reality of privilege—what it is, how it operates, who it excludes, and what damage it does. Engaging our minds can take the shape of reading books (yes, books like White Picket Fences, but also other memoirs and histories and works of sociology) and discussing them with others, listening to speakers, researching local history, and asking questions. Without this work of the mind, anyone engaging in the work of racial justice runs the risk of well-meaning but harmful and ignorant action.

The Heart

The “heart”—the seat of our emotions and the soul—needs to be engaged through relationships of mutual dependence. As a Christian, I see those relationships as both vertical and horizontal. There is the vertical relationship with God expressed through prayer: both the confession of corporate, historic, and individual sin, and the crying out to God for help in knowing how to participate in the work of restoration and repair. Then there are horizontal relationships, not relationships that perpetuate a power dynamic, but relationships that involve giving and receiving, recognizing our common humanity, trusting that each of us has gifts to offer and needs that only other people can fill. Without engaging our hearts, we run the risk of an arrogant approach to social problems that ignores love and perpetuates existing power structures.

The Hands

And finally, once the head and the heart are engaged, the hands can get to work and move lovingly into the world (more on what that might look like in a later post). But our actions in isolation run the risk of burnout or despair, action not grounded in a love outside ourselves, actions not connected to other people working towards the same end.

So my hope for myself, and for anyone who hears me speak or who reads White Picket Fences, is a patient and humble engagement with the issues of social division, starting slowly and quietly. Engagement that doesn’t rush to action but sits patiently and learns and listens, grieves and connects, asks for guidance, pursues friendship, and begins to trust in love instead of fear.

This is not charitable work of service or financial aid. This is not removed intellectualism that studies a problem without grieving the harm inherent in our history. This is not emotionalism that means well but accomplishes little. Rather, this is a work of body, mind, and spirit, of hands, head, and heart, of the whole self engaged in relationships with others and with God. It is lifelong, transformative work.

If you are someone who wants to participate in the healing work of social change, then let it take time. My hope would be that you would:

Use your head. Read White Picket Fences (and other books) and discuss it with other people. Learn about the historical and contemporary realities of racial, economic, and other social divisions in your communities.

Use your heart. Confess your role in the pain. Pray for guidance. Pursue friendships outside your typical social group. Look for a mentor who is a person of color. Look for a mentor who has an intellectual disability.

And then, use your hands: Take small steps towards change in your individual life. Look at areas in which you have influence or power and consider how you could use that influence for the common good, for breaking down social barriers, for healing. Connect with other people—through institutions and organizations—who are working towards justice and healing.

I will be writing more about all of these things and beginning to offer resources for engagement with these issues and topics. And I will be praying for each of our small choices to help us participate in this ongoing and lifelong work that changes us, makes us more dependent upon each other and upon God, prompts us to take risks to connect to one another, and moves us away from fear and towards love.

The post The Head, the Heart, the Hands: Engaging with the Problem of Privilege appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.