Amy Julia Becker's Blog, page 140

April 4, 2019

What Keeps Us from Love?

What keeps us from living the most meaningful life we could live? From experiencing God’s love?

What keeps us from healing our social divisions?

What keeps us from joy and peace?

As anyone who reads this blog regularly knows, I spent a few years wrestling with the problem of privilege, wondering whether there was any possibility of a hopeful and meaningful response to the problems of social divisions in our nation. I finally landed on an answer of sorts, an answer that can be summed up in one word: love. I wrote a few chapters in White Picket Fences about love—the ways we can understand our common identity as beloved ones, the reality of love as the most true force in the universe, and the way sacrifice always comes with love. (See chapters 10 – through 12.)

I believe that if we lived in the fullness of the love of God, we would experience personal healing and we would participate in social healing that accomplished “immeasurably more than all we asked or imagined” (Ephesians 3). But we aren’t experiencing that healing. Why not?

I gave a talk last weekend about how fear keeps us from God’s love. I looked at 1John 4, where John writes, “There is no fear in love, because fear is about punishment.” I talked about all the contemporary fears (aka anxieties) that surround finances and achievement, marriage and parenting, violence and prosperity, even the fears surrounding pleasing God or religiosity.

But after I gave that talk I was struck by something else that keeps people from God’s love: the church.

I don’t mean the doctrines of the faith, though of course doctrine can and has been used as a cudgel rather than a guide to life.

I don’t mean the scandals of sexual abuse by clergy, though of course those too have kept people from knowing the powerful healing and invitation of God’s love.

But recently I’ve been learning more and more about the history of the church in America, and especially the white Protestant church in America. The white church as a whole has condoned the oppression of marginalized people—the very people Jesus instructs us to look out for and value most—from its beginning. The white church has also segregated itself from brothers and sisters of color throughout our history. Both the injustice and the exclusion keep us from the love of God.

To cite a few examples:

In the 1600s, an enslaved woman named Elizabeth Key successfully sued the state of Virginia for her freedom based on the fact that her father was a free Englishman and that she was a baptized Christian. Eventually the state passed two laws—one to establish that a person’s free or enslaved status passed through the mother, and another to say that Christian baptism no longer guaranteed freedom. (This is documented widely, but I first learned it in the podcast series Seeing White.)

Jonathan Edwards, the great revivalist from Massachusetts who sparked the Great Awakening, owned slaves. (I learned this in Jemar Tisby’s The Color of Compromise .)

White churches throughout the north opposed the abolitionist cause, even running abolitionists out of their churches (including Frederick Gunn, the founder of the school where we now live).

The majority of white churches failed to condemn lynching and failed to actively support the civil rights of African Americans throughout the 20th century. (An American Lent details much of this history)

Even still, black Christians throughout the United States are crying out for justice while many of their white brothers and sisters ignore their pleas. One part of the body of Christ is crying out in pain—why is the rest of the body not feeling that pain? (see Arrabon’s Race, Class, and the Kingdom of God video series for more on this point)

The gospel of Jesus Christ has more to say about healing social divisions, about the power of God’s love to transform brokenness and overcome animosity and establish a new way of being together in the world, than any other philosophical or religious system. The entire book of Ephesians was written as a cry for unity among the socially divided Christians of Paul’s days—the Jews and the Gentiles. Jesus’ final prayer for his followers was that they be one. Reconciliation across dividing lines is central to the gospel. And yet we remain divided.

What keeps secular liberals who care about justice from the love of God? What keeps spiritual-but-not-religious folks from the love of God in Jesus Christ? What keeps white and black Christians from experiencing the full healing power of the love of God?

We do.

But we are also invited to receive God’s powerful love and to participate in an ongoing work of healing.

I’ll be sharing five ways to receive God’s love in my next newsletter, which comes out next week. Sign up here to receive it.

The post What Keeps Us from Love? appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

How We Keep God’s Love

What keeps us from living the most meaningful life we could live? From experiencing God’s love?

What keeps us from healing our social divisions?

What keeps us from joy and peace?

As anyone who reads this blog regularly knows, I spent a few years wrestling with the problem of privilege, wondering whether there was any possibility of a hopeful and meaningful response to the problems of social divisions in our nation. I finally landed on an answer of sorts, an answer that can be summed up in one word: love. I wrote a few chapters in White Picket Fences about love—the ways we can understand our common identity as beloved ones, the reality of love as the most true force in the universe, and the way sacrifice always comes with love. (See chapters 10 – through 12.)

I believe that if we lived in the fullness of the love of God, we would experience personal healing and we would participate in social healing that accomplished “immeasurably more than all we asked or imagined” (Ephesians 3). But we aren’t experiencing that healing. Why not?

I gave a talk last weekend about how fear keeps us from God’s love. I looked at 1John 4, where John writes, “There is no fear in love, because fear is about punishment.” I talked about all the contemporary fears (aka anxieties) that surround finances and achievement, marriage and parenting, violence and prosperity, even the fears surrounding pleasing God or religiosity.

But after I gave that talk I was struck by something else that keeps people from God’s love: the church.

I don’t mean the doctrines of the faith, though of course doctrine can and has been used as a cudgel rather than a guide to life.

I don’t mean the scandals of sexual abuse by clergy, though of course those too have kept people from knowing the powerful healing and invitation of God’s love.

But recently I’ve been learning more and more about the history of the church in America, and especially the white Protestant church in America. The white church as a whole has condoned the oppression of marginalized people—the very people Jesus instructs us to look out for and value most—from its beginning. The white church has also segregated itself from brothers and sisters of color throughout our history. Both the injustice and the exclusion keep us from the love of God.

To cite a few examples:

In the 1600s, an enslaved woman named Elizabeth Key successfully sued the state of Virginia for her freedom based on the fact that her father was a free Englishman and that she was a baptized Christian. Eventually the state passed two laws—one to establish that a person’s free or enslaved status passed through the mother, and another to say that Christian baptism no longer guaranteed freedom. (This is documented widely, but I first learned it in the podcast series Seeing White.)Jonathan Edwards, the great revivalist from Massachusetts who sparked the Great Awakening, owned slaves. (I learned this in Jemar Tisby’s The Color of Compromise .) White churches throughout the north opposed the abolitionist cause, even running abolitionists out of their churches (including Frederick Gunn, the founder of the school where we now live). The majority of white churches failed to condemn lynching and failed to actively support the civil rights of African Americans throughout the 20th century. (An American Lent details much of this history)Even still, black Christians throughout the United States are crying out for justice while many of their white brothers and sisters ignore their pleas. One part of the body of Christ is crying out in pain—why is the rest of the body not feeling that pain? (see Arrabon’s Race, Class, and the Kingdom of God video series for more on this point)

The gospel of Jesus Christ has more to say about healing social divisions, about the power of God’s love to transform brokenness and overcome animosity and establish a new way of being together in the world, than any other philosophical or religious system. The entire book of Ephesians was written as a cry for unity among the socially divided Christians of Paul’s days—the Jews and the Gentiles. Jesus’ final prayer for his followers was that they be one. Reconciliation across dividing lines is central to the gospel. And yet we remain divided.

What keeps secular liberals who care about justice from the love of God? What keeps spiritual-but-not-religious folks from the love of God in Jesus Christ? What keeps white and black Christians from experiencing the full healing power of the love of God?

We do.

But we are also invited to receive God’s powerful love and to participate in an ongoing work of healing.

I’ll be sharing five ways to receive God’s love in my next newsletter, which comes out next week. Sign up here to receive it.

The post How We Keep God’s Love appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

March 28, 2019

The Bad News About Changing the World

I visited the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, PA with William and Marilee last week. The whole museum is terrific (yes, especially for kids but I really enjoyed it too), with exhibits about the human body, the earth, outer space, and tons of other topics with hands-on opportunities for learning that feel more like recess than school.

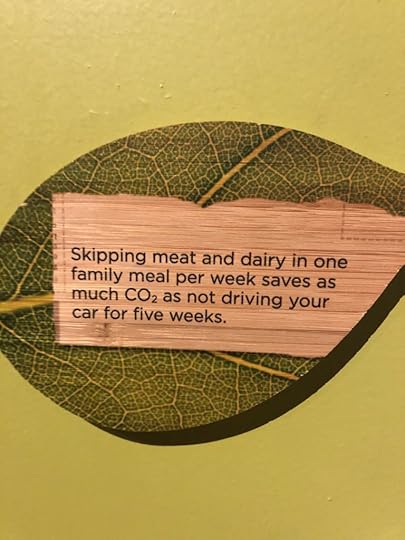

At the end of our time there, however, we came across a statement that wasn’t so playful: “Skipping meat and dairy in one family meal per week saves as much CO2 as not driving your car for five weeks.”

WHAT?!?

William knew a little bit about this already—“It’s because of methane. All those pooping and farting cows let methane into the atmosphere and it contributes a lot to climate change.” (Ten-year old boys pay attention when they learn anything that has to do with flatulence.)

I had heard about the methane problem before, but this statistic astonished me. William was pretty impressed by it too. “I need to change how much milk I drink,” he said. When we got home, he dutifully took out a measuring cup and poured one cup of milk, his new self-imposed ration for the day.

We are five days into this experiment. Last night, a big sigh. A shoulder slump. “I just really love milk,” he said. (And let me be clear that William can go through a half gallon a day. He chugs milk. He gets many, many calories from milk.)

I want to make it better for him. I want to tell him his efforts won’t really make a difference. I want to tell him that there’s a way for him to get all the enjoyment he wants and still help save the planet. But the reality is that for him to participate in reducing methane, he needs to drink less milk. For him to love this planet, he has to pay a cost, however meager it may be. I want to promise him that he will reap the benefits of this small sacrifice, and perhaps that’s true in some very broad sense. But for now at least, he just needs to drink less milk and feel a little bummed about it. He needs to be inconvenienced.

And the same is true for me, not just when it comes to making choices about food, but also when it comes to consumption and entertainment and relationships. For me to live based on what I value, on what I believe to be true and real and good and just, I will need to sacrifice what I want sometimes. I will need to be inconvenienced. And in this land of plenty, the message I receive all around and every day is that convenience is God.

I want to live on a cleaner planet, where we create less waste and recycle more of the waste we create and invest in clean energy sources. I want to live in a more just society, where everyone has their basic needs met and has access to education and opportunity. I want to live in a way that honors the humanity of myself, my kids, my neighbors. I want to live the way of love, and love is inconvenient.

I must stop worshiping the god of convenience if I want to worship the God of truth, beauty, justice, and love.

Love is inconvenient. But love is also beautiful.

Love is not coercive. Love doesn’t force me to give up my third LaCroix of the day in honor of less waste and a deeper connectedness to and respect for creation. Love doesn’t scold me for my irritation at the grocery store clerk who is slowly accounting for my purchases. Love doesn’t punish me for snapping at the kids when they’ve done nothing wrong and I’m just feeling lonely and worried and tired. Rather, love invites me. Invites me to relinquish my hold on convenience, my hold on power and control, my hold on satisfying every desire as it arises. Invites me into a slower, less productive, less “successful” life. And one way to practice this inconvenient, life-giving, loving way is through little choices, like drinking less milk.

As an addendum, anyone who is thinking about taking on habits of being that shape who you are in the way of love rather than the way of convenience should check out Justin Earley’s new book The Common Rule: Habits of Purpose for an Age of Distraction.

The post The Bad News About Changing the World appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

March 21, 2019

World Down Syndrome Day 2019

Today we celebrate World Down Syndrome Day and the lives of millions of people with Down syndrome around the globe. (It’s March 21, 3/21, and Down syndrome is the genetic condition in which people have three copies of the 21st chromosome. Someone pointed out that A Good and Perfect Gift, my book about what it took for us to receive Penny as a gift, was written in 21 chapters over three parts. I wish I could claim that was intentional!)

I don’t actually think a lot about Down syndrome these days. Penny is 13. She’s healthy and happy and learning and growing. We couldn’t be more grateful for her. And it is increasingly challenging to figure out how to tell her whole story while also honoring her privacy and personhood. But for some reason, World Down Syndrome Day was a spark for me, and I wrote three different essays, which have been published in three different places today.

First, in honor of Penny, I wrote an essay for the Washington Post about the ways she has opened my eyes to the reality of privilege and exclusion and the chance to participate in healing social harms. Here’s a taste: “But something else happened as I got to know my child. I stopped wanting Penny, and other kids like her, to be shoehorned into my world of privilege. I began to see Penny’s life as an invitation to step out of my fenced-in existence. I read theologians of disability, such as Jean Vanier, Hans Reinders and Henri Nouwen, who wrote about vulnerability as a gift we give one another, a way of expressing our humanity through love and through recognizing the inherent value of every human.” Read more here.

And then, an essay for the Hartford Courant related to the recent college admissions scandal. Here’s the back story:

Last fall, I had a conversation with William about college. It was premature, I know. He’s ten. But it was a conversation about how he doesn’t need to go to a top-tier school. And in fact, about how it would be awesome if someone from a less advantaged background is able to go to that school instead.

I have become increasingly aware of the fact that kids like ours–kids with white, married, affluent, educated parents–already have a tremendous advantage when it comes to their own education. And also increasingly aware of the dangers to those affluent, educated kids when life becomes a pressure cooker headed towards endless achievement. The scandals last week about parents bribing their children’s way into schools only underscored my own thoughts.

Our family has a legacy of college admissions at “prestigious” schools. We also have a child with Down syndrome who has provided a different way to view value, success, and purpose. I had a chance to write for the Hartford Courant today about how having Penny in our family has affected our view on “success”. I write, “Penny will not enroll at Yale or Princeton, but she has offered us a chance to begin a different family legacy. Penny, like many people with intellectual disabilities, does not move quickly or efficiently. She will never take the SAT. She struggles with many abstract concepts. And her presence in this overachieving family has served as an invitation to us all.” Click here to read more.

Finally, I’ve been struck recently by the fact that Penny has a positive perspective on her life even as her life gets harder. Even in the midst of the reality of middle school–social rejection and loneliness and identity formation–she is loving and kind (and sad and moody). So I wrote about that dynamic, about happiness in the midst of grief and joy in the midst of sorrow and an embodiment of patient love that I hope one day to learn, for the Christian Century. As I write there, “If this is what love looks like, then I have spent much of my life rejecting love. I have been too busy and too careless to be inconvenienced, challenged, slowed down by it. I have been too ready to grab knowledge rather than receive wisdom. I have been too eager to prove myself, to receive accolades rather than turn my gaze beyond myself to the beauty of my neighbors.” Read the whole story here.

Thirteen years ago, I might have been surprised to think of saying “Happy World Down Syndrome Day,” but I say it today with sincerity and immense gratitude that I have the privilege of raising our daughter.

The post World Down Syndrome Day 2019 appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

March 14, 2019

Digging Up Old Wounds

It often seems like talking about the wounds of our past—whether our family’s past or our nation’s past—is an exercise in self-flagellation. Why revisit pain and suffering? Why draw attention away from what might be a pleasant and peaceful present moment?

But I’ve come to believe that acknowledging the wounds of the past is the first step towards healing.

Isabel Wilkerson, author of The Warmth of Other Suns, offers a helpful analogy in talking about acknowledging the pain of our past. In an interview with On Being host Krista Tippett, she mentions that we don’t resist talking to doctors about our family health history, even if the reality of that history is painful. I, for example, tell my physician that my mother had colon cancer in her 50s, as did my paternal grandmother. This is not fun news to share, especially because it leads to the reminder every year that I will be receiving colonoscopies ahead of the typical schedule for such undignified bodily screening for abnormal growths. And yet I willingly share this information because I know that it might help me maintain the very health and well-being I’m experiencing right now, or it might help me recognize a potentially fatal problem that I didn’t even know was there.

Similarly, when we acknowledge the harm that has been done throughout our history, we accomplish two necessary goals. One, we potentially prevent the same harm from occurring again. And two, we identify potentially fatal problems that might exist right now without our knowing it.

I write in White Picket Fences about researching the history of my hometown of Edenton, North Carolina. It was painful for me to recognize the extent of the injustices that had occurred in a place so dear to me. But it was also helpful for me to understand more clearly the way my path as an affluent white American was shaped and formed in the context of that injustice.

More recently, I’ve been reading about the history of my current town of Washington, CT. Our family lives at a boarding school, and I’ve known that the founder of the school, Frederick Gunn, was an abolitionist. I’ve been reading Mr. Gunn’s letters and learning more about the fierce support of the institution of slavery not only in our town but specifically through the church in our town at the time.

In Mr. Gunn’s words (written in 1846): “No institution nor all institutions are doing so much to perpetuate slavery as the churches in America… Here is a man who is enslaving our brothers, chaining them down to a mere animal existence, trampling on their hearts, treating them as mere nothings… He is upholding a system by which this is done on a giant scale. He, and others like him, have enlisted the nation in defense of the system… this man is called a Christian…”

It’s easy for me to look back and see that Mr. Gunn was right, that any church support of the institution of slavery should have been challenged and renounced. And yet reading these words nearly 200 years later also makes me wonder about the times I have disregarded my fellow Christians who have called the contemporary church out for silence in the face of injustice.

In reading White Picket Fences, people have asked me about how to respond to the problem of privilege and social division in our nation. I’ve written about how we need a holistic response, involving head, heart, and hands. For people who are ready to embark on a journey of healing, one step is to use your head to ask questions and learn: What do you know about the history of the place where you grew up, or the place you live now, as it pertains to race, disability, and other markers of social advantage? Is there anything that might be different from what you assumed (or were taught) when you were young? What do you want to learn about the history of our nation, your town, your faith community, as it pertains to these topics? Are there ongoing wounds in your community related to this history?

The purpose of bringing up the wounds of the past is not condemnation. There is no part of me that condemns my mother or my grandmother for having colon cancer. But I am going to dredge up that uncomfortable and unfortunate reality every year when I get a physical, because acknowledging the disease of the past may be crucial to preventing or discovering the same disease in my future. Similarly, the purpose of acknowledging the harm of the past in our families, our towns, and our nation is that we might prevent further harm and participate in ongoing healing.

***We’re working on a page with resources for learning more—through books, websites, film, podcasts, and stories—and we would love to hear from you if and as you begin to ask these questions and discover local answers. (You can comment below or email amyjuliabeckerwriter [at] gmail [dot] com)

The post Digging Up Old Wounds appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

March 6, 2019

The Call of Lent (And the Temptation)

You know that empty container inside the back door where you throw your keys? And maybe also your sunglasses and earbuds and a hair-tie and some loose change and whatever else is in your hands or your pockets when you walk in the door? Chewing gum, Chapstick, an occasional stray dose of Dayquil—they all end up in that container for stray items.

As the months of the year go by Lent becomes kind of like that empty container. When it comes into my head that there’s a habit or practice in my life that I want to change in some way, some day, I throw it into the Lent bucket. The possibilities accumulate: I should drink less wine. I should take social media off my phone. I should pray at regular intervals throughout the day. I should try vegetarianism. Netflix, shopping in general, shopping on Amazon, French fries—the list of possible ways to self-improvement pile upon one another until the time comes to bring order to the clutter.

Lent has arrived, and I’m inclined to line up the detritus of my good intentions and select the one that will be “best” for me. But Lent isn’t meant to be a season of self-improvement. Not a diet plan. Not a 12-step program. It’s meant to be a season of preparation for Good Friday and Easter, for these three days that stand at the center of Christian faith, for this remembrance of Jesus’ death and resurrection from the dead.

So I assess the possibilities and ask myself—exactly what is it about giving up shopping that helps me get ready for Easter? What is it about not drinking wine that prepares me for the crucifixion?

Lent can certainly be the equivalent of a New Year’s resolution or another self-help strategy. But it also can be an opportunity to use these very small and seemingly superficial habits to help me see the world differently.

For me to “set my mind” and “set my heart” “above,” as Paul admonishes the Colossians, I almost always have to make a physical, bodily change. The way for me to turn my thoughts towards Christ is to turn my body that way, whether through acts of small self-denial like forgoing chocolate covered almonds with sea salt from Trader Joe’s or through setting a timer that reminds me it is time to close the computer and pray for five minutes.

In the past, I’ve used Lent to confront my habits of mindless consumption, whether that’s of food, wine, or material things. This year, I’m confronting my habits of forgetting who I am and who God is. My plan for Lent is to pray with intentionality three times a day—morning, noon, and night. By this I mean I’ll change my posture, whether by kneeling, closing my eyes, sitting upright and cross-legged, or getting out of my chair and lying supine on the floor. I’ll use my body to remind my mind and heart that we’re paying attention to the whispers of the Spirit all day long.

There’s nothing magical about this season, but it is an opportunity to use my body to train my heart and mind on the very good news that God is God and I am not, that God loves me, and that I am invited to live every day in that expansive, welcoming, humble love.

**I also want to recommend, for anyone who is ready and willing to learn more about the history of racial injustice and social division in our nation, “An American Lent,” a free prayer and devotional guide through this history available here.

The post The Call of Lent (And the Temptation) appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

February 28, 2019

4 Books About Our Common Humanity

Societies have drawn dividing lines throughout all of human history that demonstrate who is “in” and who is “out.” In Western culture, we’ve seen those lines through the history of racial categorization, beginning with what was then a new concept in the 1600s of “black” and “white” people. We’ve also seen those lines drawn when it comes to gender, ability, ethnicity, and religion.

The Christian understanding of humanity, however, insists that these social divisions are unjust and harmful, and that following God’s way of love means being ministers of healing and reconciliation. When the Christian Scriptures were written, Jewish people were socially divided from Gentiles (anyone who wasn’t Jewish), men were divided from women, slaves were divided from free people, and different ethnic groups were also divided from one another. Paul writes in multiple places about the ways in which all people are invited into the family of God. “The mystery of Christ,” Paul writes, “is that through the gospel the Gentiles are heirs together with Israel.”

In other words, because of the work Jesus did to reconcile humanity to God, to restore human beings to their original status as creatures in the image of God, everyone is included. The dividing social walls are eradicated. The family of God is not just for Jewish people, but for Gentiles as well. This is the big, good news.

It was hard for people to understand this news 2,000 years ago. It’s hard for us now. We still erect social walls and our churches still reflect social divisions. And I don’t pretend to be someone who has figured it all out.

That said, when our daughter Penny was diagnosed with Down syndrome thirteen years ago, I began a process of wrestling with what it means to be human. I had an internal categorization system that excluded my daughter from my understanding of full humanity, and I was pretty sure it was my system that was wrong and not my daughter. So I began to learn more about what it means to be human from a theological perspective. Over time, understanding Penny’s full humanity meant better understanding my own and that of everyone around me.

So if you would like to think more about what it means to be human, what it means to express diversity within our common humanity, what it means to understand yourself and others as both vulnerable and beloved, needy and gifted, broken and beautiful, I wanted to offer four books that have helped me:

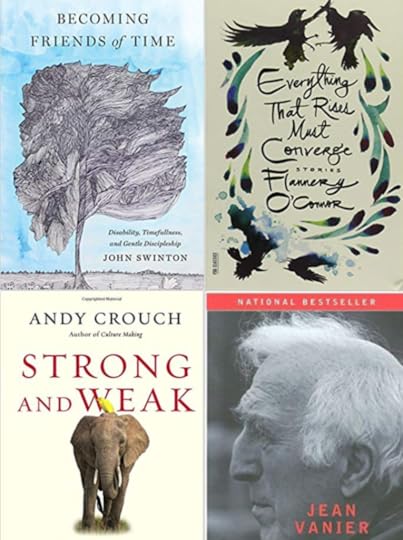

Becoming Human by Jean Vanier. Vanier is the founder of L’Arche, a worldwide movement of people with intellectual disabilities living in community with typical people. Vanier’s understanding of the humanity that can emerge in the context of vulnerability and mutual giving and receiving has deeply shaped my understanding of exactly the title of this book, the invitation to become human.

Strong and Weak by Andy Crouch. This book does not deal directly with social divisions, but Andy’s understanding of the conditions under which human beings flourish–authority plus vulnerability–is both a challenge and a source of hope for me. He offers a simple grid and very easy to understand but profound insights into who we are and who we can become.

“Revelation” by Flannery O’Connor (found in Everything that Rises Must Converge). Honestly, anything written by O’Connor points in the direction of what it means to be a human being before God, and what it takes for us to recognize our common humanity, but “Revelation,” in which a self-satisfied, religious, respectable white woman recognizes that she will be entering the gates of heaven alongside all sorts of people she deems unacceptable, disreputable, and “less” than her. This fictional portrait of humanity accords with the other more directly theological books on this list.

Becoming Friends of Time by John Swinton. Swinton is a professor of theology. He is also a trained nurse. I had the chance to spend some time with him recently, and he embodies the gentleness, thoughtfulness, and humility that run through his writing and teaching. His most recent book discusses the three-mile-per-hour God (aka Jesus, who walked at a pace far slower than our busy and frantic world) and the ways in which people with intellectual disability and memory loss can point busy, frantic people towards the heart of God.

As an addendum, there’s also a host of beautiful memoirs that I love on this topic: Dancing with Max, by Emily Colson about her experience with her son Max, who has autism (I reviewed this book for Christianity Today here); Expecting Adam by Martha Beck, about surrendering to Love in bringing her son Adam into the world with a prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome, and both Adam and The Road to Daybreak, memoirs by Henri Nouwen about the year he spent in a L’Arche community with an adult with intellectual disabilities and the way he and Adam learn to care for one another.

The post 4 Books About Our Common Humanity appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

February 20, 2019

The Problem with “Noblesse Oblige”

After George H.W. Bush died, we heard a lot about how he modeled the idea of “noblesse oblige.” It’s a French term that translates as “nobility obligates.” In other words, anyone born into the upper economic class should feel a sense of obligation toward his or her fellow humans, and particularly to those less fortunate.

There are obvious positives to this concept. At least in theory, it motivates generosity and philanthropy. It hints at the idea that socioeconomic positions are not exclusively or necessarily a matter of hard work. It even acknowledges some measure of luck or privilege. The concept extends beyond wealth into the concentric circles of education. Princeton University’s unofficial motto, for instance, is “In the nation’s service.” Princeton graduates are urged to use their status, earning potential, and intellectual knowledge on behalf of others.

But there are problems with this ethos of “noblesse oblige,” and over time those problems eroded the concept. “Noblesse oblige” can lead to assumptions of superiority, the idea that the upper class has gifts to offer the rest of the world, and those poor, marginalized underprivileged people are grateful recipients of this beneficence. It’s a generosity that perpetuates a hierarchy. It keeps the privileged behind a wall of wealth, education and power. It also keeps the “noblesse” out of touch with the reality of life outside that wall, out of touch with economic hardship, out of touch with hard work that doesn’t lead to economic success, out of touch with human suffering and a broader array of human diversity.

The concept of “noblesse oblige” has fallen out of favor in recent years as social scientists have demonstrated the systems that perpetuate wealth gaps and education gaps and income inequality among different demographic groups. Americans have never been too comfortable with the idea of nobility anyway. We want to believe in equal opportunity. We want to believe in meritocracy. We want to believe that anyone who works hard will be rewarded, and anyone with wealth earned it and deserves to keep it.

And yet America continues to see a stubbornly fixed upper class, as two lengthy and compelling articles in last year’s TIME and Atlantic magazines demonstrated. In other words, we have ended up with the “noblesse” without the “oblige.” In fact, what we might have instead is something along the lines of “noblesse shame” or “noblesse cynicism.”

Multiple recent studies have demonstrated the ways in which affluent people have cut themselves off from other people and the ways they downplay the extent of their wealth. Other studies have demonstrated the ways that even the people with the highest incomes give less, as a percentage of their income, than those in the lowest economic bracket.

I wonder whether the truth to be extracted from this old idea is simply the word “oblige.” That all human beings are, in fact, obliged to one another. All interconnected. All obligated to give not out of a sense of superiority, but out of a sense of community and reciprocity.

TIME ran a story at the end of 2018 in which they identified five heroes of the year. The list included the men who rescued the boys who were stuck in an underground cave in Thailand. The man who disarmed a shooter at a Waffle House. The hospital chaplain who drove through fire to save patients. These weren’t stories about people who had been trained in nobility, but rather people who had some inherent sense of community, some ethos of mutual giving and receiving, something that provoked them to care for others as much as themselves.

I’m grateful that the era of noblesse oblige is over. I hope it makes way for a greater questioning of income disparities and wage gaps and less satisfaction with the economic status quo. But, also, I hope we can resurrect the idea of obligation to one another.

The post The Problem with “Noblesse Oblige” appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

February 14, 2019

Love That Never Fails

On Valentine’s Day, it’s easy to think of love as a weak and meaningless force symbolized by pink candy hearts and carnations. But for people of faith, it’s worth remembering that the Biblical picture of love is very different than the romanticized versions of love that we see in our culture. Love is one of the words that comes up most often in the Bible—more than faith, more than prayer. And the way love is described is as the most true and real thing about existence. One Biblical writer says “God is love,” (1 John 4:1) and if this is true it means that at the core of reality, at the center of existence, before anything was created, for all eternity, existed love and only love. We human beings are invited to receive that love for ourselves, and then we are invited to allow that love to free us from fear and empower us to love other people.

It is easy to think that we can overcome our fears by working harder—working harder to become a good person, working harder in school or in the office, working harder in the social realm. But in one of the most famous Biblical passages on love, from Paul’s first letter to the church in Corinth (1 Cor 13), Paul claims that without love, none of our work will amount to anything. What Paul is saying here is that even the highest public honors, even the highest spiritual powers, even the most amazing life of service is worth nothing without love.

As both a teenager and an adult, I have often retreated into a place of anxiety, which, when I have dug a little deeper, is a place of fear. Fear of failure. Fear of rejection. Fear of never measuring up. I can now see that those fears are driven by the fact that I often don’t feel sure that I am loved. Having a daughter with a disability exposed my fears, which opened me up to the possibility of love. Love breaks through the walls built up by fear and connects us to God, connects us to our true selves, connects us to one another. Love also connects us to the pain inside of us and the pain of a hurting and broken world. It connects us to pain and invites us to participate in the work of love, which is the work of healing.

We celebrate people like Martin Luther King, Mother Teresa, Ghandi, Malala Yousafzai– people in history who have chosen to trust love instead of fear. Most of us will never have anything like their global impact. But just imagine the small but meaningful impact you could have in your school, your family, your town, if you were free to choose love instead of fear.

If we want to be people who live in love and not in fear, we need to reshape our thinking. I want to suggest three ways you could start to do this:

Admit your fears and the ways they fence you in. Then tell yourself that “love is stronger than fear” and envision the ways those fences are opened up.Spend five minutes every morning in a prayerful or meditative posture, reminding yourself that you are loved. Memorize a passage from the Bible about love and call it to mind whenever you are overcome with fear. 1 Corinthians 13, Ephesians 3:14-21, or 1 John 4 are good places to start.

What would it mean in your life to believe that you are deeply loved, and that love, not fear, can define your existence? Loved not because of your job performance or the cute treats you made for your kids on Valentine’s Day or the number on the scale. Loved not because of how many likes your Instagram post got today. Loved not because you prayed or read the Bible or cared for others. But loved because you were created by a God who is love, who loves you, and who will always love you with patience, with kindness, and with a love that never fails. When we sink our lives into the reality of that love, we then become free to love others with patience, with kindness, and with a love that never fails.

This post is a modified and shortened version of the chapel talk I gave at St. Mary’s school in Raleigh, NC last week.

The post Love That Never Fails appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.

February 8, 2019

Guest Post: Cara Meredith

Cara Meredith’s new book, The Color of Life, is a memoir about race, justice, and love. I so appreciated Cara’s story—her marriage to James Meredith, a black man who came from a prominent southern family, and her journey to understand racial identity and love as they began their own family together. Cara writes with candor and grace. I hope you’ll check out her book. Here’s a short glimpse at some of the ways she has sought to make small changes, in this case, in terms of seeking out friends who come from different ethnic backgrounds than her own:

It was just another night at our dining room table, or so I thought. Three other couples gathered with my husband James and me for an informal night of friendship and conversation. We ate taco soup loaded with and cheese and crumbled tortilla chips; we clinked glasses of wine and laughed so hard tears rolled down our cheeks.

A funny thing happened that night, though: I began to notice those sitting around the table with us, maybe for the first time. James wasn’t the only person of color in our home that evening – instead, a Latinx couple, a black couple and a white couple gathered with us. We shared a commonality of being new to the institution of marriage, new to unearthing simultaneous feelings of exhilaration and loneliness that come with saying yes to the one who holds your heart.

But in that noticing, I also felt a kind of exclusion, the majority for once becoming the minority, at least for a single evening. As I write about in my new memoir, The Color of Life, that night changed the way I interact with the world around me, for I saw firsthand the common bonds of injustice:

“Theologians and philosophers often call it a commonality of oppression. If I were to dust off an old book from seminary, I’d remember that in liberation theology, the eyes of culture always count, for the oppressed are always on the lookout for a redeemer, a liberator, a savior of spirits and souls. As we ate together that night, soup dribbling down our chins, the stories that rang solely of injustice to me became a common, binding experience for those who shared their pain aloud. The “I” became the “we,” the tangled roots of oppression and injustice the stuff of shared experience.

“As a white woman who lives and breathes a predominantly white existence, I have never – nor will I ever – experienced oppression, at least not because of the color of my skin. I might see the effects of racial oppression firsthand because my life is intertwined with a man who has fought against the grave realities of injustice, but I will never fully experience what it means to be slighted for having darker skin” (81).

I started noticing something new that night – a noticing of who was and wasn’t sitting at our table, a noticing of who had and hadn’t been invited to join us for a meal. Years later, I would read about a study from the Public Religion Research Institute that confirmed the normalcy of my friendships. Although the study is nearly five years old now, the report mirrored my experience when it reported that “in a 100-friend scenario, the average white person has 91 white friends; one each of black, Latino, Asian, mixed race and other races; and three friends of unknown race. The average black person, on the other hand, has 83 black friends, eight white friends, two Latino friends, zero Asian friends, three mixed race friends, one other race friend and four friends of unknown race.” My own journey, one of equal parts comfort and ignorance. I suppose that’s when I began to notice who hadn’t been sitting at my table all along.

So, I started to do something about it, because when it comes to taking steps toward combating racism and fighting injustice, noticing matters, but doing something about this noticing matters even more.

After all, if we only fill our tables and our living rooms and our backyards with people who look and think and act mostly like us, then we miss out – for we know and we are changed by the stories we hear, by the accounts we read and by the tales we absorb.

And I don’t know about you, but I’m hungry for a little bit of change to happen in my heart and in the world around me.

The post Guest Post: Cara Meredith appeared first on Amy Julia Becker.