Amy Julia Becker's Blog, page 147

October 9, 2017

Missing Out on Beautiful: New Free Ebook about Down Syndrome and other thoughts

As many of you know, I stopped blogging two years ago, mostly because blogging consumed the time that I had for writing, and I chose to write books instead of blog posts. But I still enjoy sharing thoughts with readers in a more immediate way, so I have been using my Facebook author Page to share book recommendations, reflections on culture, stories from our family, and updates about the books I’m working on. For those of you who don’t use Facebook, or who don’t want to check the page daily, I’m going to start posting a weekly compilation of those thoughts here on my website. I hope you enjoy!

As many of you know, I stopped blogging two years ago, mostly because blogging consumed the time that I had for writing, and I chose to write books instead of blog posts. But I still enjoy sharing thoughts with readers in a more immediate way, so I have been using my Facebook author Page to share book recommendations, reflections on culture, stories from our family, and updates about the books I’m working on. For those of you who don’t use Facebook, or who don’t want to check the page daily, I’m going to start posting a weekly compilation of those thoughts here on my website. I hope you enjoy!

Friday, October 6, 2017

October is Down Syndrome Awareness Month. I’ve created an eBook called “Missing Out on Beautiful: 7 Essays about Raising a Child with Down Syndrome” as my way of helping to raise awareness about this genetic condition. The eBook is FREE.

That’s right–you do not need to pay a dime, or even a penny, to receive it. You just need to go to my website and enter your email address where it says, “Signup here and receive my new free eBook,” and the link will be sent automatically to your inbox.

The book compiles six essays I’ve written over the years as well as new material, including an interview with Penny herself. It is filled with beautiful photos. And yes, it is great for people with children with special needs. But these essays are for all of us because they are reflections on where we find meaning and purpose in life, how we understand value, how children help us grow up, and what it means to base life on love instead of achievement.

Please click on this link to get your free copy of this eBook, and please share this link with anyone else who would benefit from a reminder about what makes life worth living today.

As Penny herself says, “Don’t be scared because your child’s life could be easier than expected. My life is filled with caring, loving people and joyful happiness.”

Thanks,

Amy Julia

Tuesday, October 3, 2017

“Prepare the child for the path, not the path for the child.”

That’s my little gem of wisdom for the day (that a friend shared with me), along with a confession that I am inclined, like many of my fellow “helicopter” parents, to make that path as smooth as humanly possible for our kids. I still wake them up in the morning and pack up their lunchboxes if they/we are running late and give in to many requests for sweets and treats.

But I also see the joy and freedom they experience when they encounter some small measure of adversity and work to overcome it–William forgetting to study for his spelling quiz one week and missing a few words and then becoming more attentive to his homework the following week, Penny getting hot at school and starting to check the weather the night before so she’s prepared for our 30 degree temperature swings, Marilee heading out the door to school even though she has a cold.

To prepare the child for the path pretty much ensures that the child will fall down, will be bruised sometimes. It also pretty much ensures that the child will learn how to navigate small obstacles, how to pick themselves up from a fall, and when to ask for help because they truly need it.

As with everything I try to teach our kids, I want to learn as well. What am I doing to prepare my mind, body, and spirit for the path ahead, whatever twists and turns, stones and obstacles, it might hold?

Monday, October 2, 2017

“God’s love is like my neighbor’s vegetable garden.”

I had the chance to preach last week on being called to love one another, and among other things I had a chance to talk about Where the Red Fern Grows and our neighbor’s plentiful and generous supply of kale, tomatoes, leeks, and herbs. If you’re interested in hearing more, here’s the audio.

And in case you don’t have time to listen, here’s the vegetable garden part. God’s love is abundant (and for anyone who has ever planted tomatoes or zucchini, you know what I mean). God’s love is freely given (I have done absolutely no work to grow these vegetables next door). And God’s love tastes so good you want to share it (my neighbor is so excited about these vegetables that he will even pick them himself and bring them to my door).

The sermon says more about the source of love, how to receive that love, and ONLY then, how to give that love away.

September 30, 2017

Love, White Picket Fences, and Notes from Penny

As many of you know, I stopped blogging two years ago, mostly because blogging consumed the time that I had for writing, and I chose to write books instead of blog posts. But I still enjoy sharing thoughts with readers in a more immediate way, so I have been using my Facebook author Page to share book recommendations, reflections on culture, stories from our family, and updates about the books I’m working on. For those of you who don’t use Facebook, or who don’t want to check the page daily, I’m going to start posting a weekly compilation of those thoughts here on my website. I hope you enjoy!

As many of you know, I stopped blogging two years ago, mostly because blogging consumed the time that I had for writing, and I chose to write books instead of blog posts. But I still enjoy sharing thoughts with readers in a more immediate way, so I have been using my Facebook author Page to share book recommendations, reflections on culture, stories from our family, and updates about the books I’m working on. For those of you who don’t use Facebook, or who don’t want to check the page daily, I’m going to start posting a weekly compilation of those thoughts here on my website. I hope you enjoy!

Friday, September 29, 2017

I preached a sermon on love last Sunday (I’ll share it here when the audio is available), and one passage I used comes from Ephesians 5:1-2, where Paul writes, “Be imitators of God, as dearly loved children, and live a life of love.” Impossible if we see this as something we need to do on our own. An invitation to intimacy with God if we see this as a natural reaction to spending time with Him.

Three years ago this month, my second book, Small Talk: Learning from My Children about What Matters Most came out. I wrote about this verse in that book too:

“I begin to think that this impossible command to imitate God is really an invitation to intimacy–even to the particular intimacy of a child with a parent. The intimacy of Marilee asking me to brush her nose with powder as I put on makeup. Of William standing next to me while I wash my face, just to have his body next to mine. Of Penny starting each morning with a smile and a hug and a request to cuddle for a minute. The intimacy of my children asking me for what they need without apology because they assume that my affection and care for them will last forever, no matter what they do. The intimacy that has room for anger and sadness and laziness and mistakes. The intimacy that assumes agape, a love that never fails.”

Thursday, September 28, 2017

One of Penny’s gifts is caring for other people. She is quick to respond to anyone who is in need, whether that be through praying for them or writing them a note. She learned, for example, that friends of ours would be moving a few days ago. Two days later, with no prompting from us, she said, “Oh, Mom, I wanted to write Jack and Susan a note, just to thank them for what they’ve done for us and tell them I hope they have a good move.” I was out with Marilee all afternoon, but when I came home, sure enough there was Penny’s note to Jack and Susan as well as a get well note for my aunt who had recently had surgery.

One of my favorite notes was from last summer. Penny had been asking if we could get frozen yogurt, and I finally took them all for dessert one evening. The next morning, on my pillow, I found her words: “Dear Amy Julia, thank you for taking us to sweet frog. it was amazing. inspired. dream come true. Penny”

Amazing. Inspired. Dream come true. Penny.

Wednesday, September 27, 2017

My friend Sharon Hodde Miller has written an essential and excellent book. It comes out next week, and I had the privilege of reading an early draft. I will give this book away to friends. I will recommend it to pastors, to friends, to small groups of people. The title says a lot: Free of Me: Why Life is Better When It’s Not about You. We want freedom and fulfillment and joy. We want to take care of ourselves and our families. This book explores the ironic dynamic that the more we focus on ourselves the more miserable we can become, but if we “raise our gaze” to a bigger purpose and plan it frees us to take care of ourselves, our families, participate in our communities with greater peace and joy. Sharon is smart and insightful while also writing in highly readable and accessible prose with funny and poignant stories and examples throughout. I highly recommend this book!

Tuesday, September 26, 2017

Even as someone who never watches football, I’m thinking about the implications of kneeling during the national anthem these days. I love living in a country where non-violent protest is a protected form of expression. In fact, I see the act of kneeling as a tribute to the anthem itself and to the ideals we espouse as a nation, ideals that include the right of citizens to speak and act when we haven’t fully lived into our own ideals.

Two articles to recommend in thinking about what’s going on here. One from the Washington Post, in which the author compares Colin Kaepernick and Tim Tebow. I appreciated this article because I thought he was going to compare and contrast these two Christian football players and ultimately conclude that one expresses his faith well and the other poorly. But that’s not what this article does at all. Rather, it points out the richness and diversity of the Christian faith and talks about why the Tebows of the world need the Kaepernicks and vice versa.

(Along similar lines, I just picked up an old book by Richard Foster called Streams of Living Water, which examines the six great historical “streams” of Christianity.

For another good, if sobering, read about our cultural moment and the disruption we are experiencing as a nation, I also recommend David Brooks’ piece from today’s New York Times.

Monday, September 25, 2017

I went for a run this summer and I was struck by how many white picket fences I passed. Some were fancy, others plain. Some were well-kept, others with paint peeling. My upcoming book is titled White Picket Fences: Confessions of Privilege, and this week’s work consists entirely of finishing the final chapters and then editing the book as a whole. As I spend my week thinking about White Picket Fences, I’m curious to hear what you think of when you hear or see pictures of white picket fences. What comes to mind? Are they positive, negative? Memories of childhood? Depictions of a foreign land?

When Your Daughter with Down Syndrome Changes Who You Are and other thoughts on mass incarceration, limiting technology, and hurricanes

As many of you know, I stopped blogging two years ago, mostly because blogging consumed the time that I had for writing, and I chose to write books instead of blog posts. But I still enjoy sharing thoughts with readers in a more immediate way, so I have been using my Facebook author Page to share book recommendations, reflections on culture, stories from our family, and updates about the books I’m working on. For those of you who don’t use Facebook, or who don’t want to check the page daily, I’m going to start posting a weekly compilation of those thoughts here on my website. I hope you enjoy!

As many of you know, I stopped blogging two years ago, mostly because blogging consumed the time that I had for writing, and I chose to write books instead of blog posts. But I still enjoy sharing thoughts with readers in a more immediate way, so I have been using my Facebook author Page to share book recommendations, reflections on culture, stories from our family, and updates about the books I’m working on. For those of you who don’t use Facebook, or who don’t want to check the page daily, I’m going to start posting a weekly compilation of those thoughts here on my website. I hope you enjoy!

Friday, September 22, 2017

For your reading pleasure… (I may say more about some of these next week, but for now, I invite you to enjoy these thought-provoking and helpful articles):

1. “Donald Trump is the First White President” by Ta Nehisi Coates in the Atlantic. This article came out a few weeks ago, but I just had the chance to read Coates’ argument that Donald Trump won because of identity politics, which is to say the politics of whiteness.

2. “Facing Our Legacy of Lynching” by D.L. Mayfield in Christianity Today. I read these two articles one after the other and was grateful to have Mayfield’s honest look at the harsh reality of white and even Christian racism within the context of hope and even redemption. She leans on Bryan Stevenson, author of Just Mercy (a book I also highly recommend), to talk about the Christian possibilities for repentance and transformation.

3. “When Life Asks for Everything” by David Brooks in the New York Times. Brooks argues that we don’t want individualism as much as we think we do. What we want is a self that gives to others in such a way that we find ourselves in a larger whole–in a marriage, a family, a friendship, even in a church, a nation, etc. Again, I read it with hope that we can indeed find ourselves by giving ourselves to others.

Thursday, September 21, 2017

Earthquakes and hurricanes have brought many of us back to the age-old questions about how a loving and powerful God could stand by and not prevent so much human suffering. Especially for people who believe that God is “in control” or who believe in the “providence” of God, how can we explain any devastation?

Without getting into the many arguments around these questions, I was grateful to read this passage from John Swinton’s book Becoming Friends of Time: Disability, Timefullness, and Gentle Discipleship: Rather than providence being a “way of describing God’s involvement in every incident that occurs in the world–a perspective that makes God responsible for the most terrible events–Bader-Saye proposes providence is the way we come to ‘name our conviction that our futures can be trusted to God’s care, even when we cannot believe that God is the direct cause of all that happens.’ . . . Providence provides a powerful narrative that ensures that in the midst of the fallenness, brokenness and confusion or God’s creation, God’s story is not lost.”

In the midst of earthquakes, hurricanes, war, and all the more individual suffering people are experiencing right now, God’s story is not lost.

Wednesday, September 20, 2017

I mentioned a few weeks ago that Penny has started middle school and that I was experiencing far more anxiety about it than she ever did. She is holding steady, and her confidence, maturity, and poise as she navigates remembering which six of her nine classes will meet each day, whether or not she’s choosing the hot lunch option, meeting new friends, and learning new material. She is happy, and stable, and we are grateful.

I know this isn’t the way the story always goes for kids in middle school, for kids with disabilities in particular, and I can’t assume it will stay smooth forever. But I was thinking back to the questions I was asking years ago about who Penny would become. I used to feel sadness and fear when I thought about Penny’s future, and here we are–grateful and peaceful instead.

In A Good and Perfect Gift, I wrote, “After weeks of thinking about Penny and about what was not good in her, I finally realized that there was just as much–no, there was more–that was not good in me. All the pettiness, all the judgment, all the bias. Over and over again, I had thought about who she might have been if that extra chromosome hadn’t gotten stuck in that first moment of conception. I couldn’t escape wondering about the ‘real’ Penny, my daughter who seemed hidden behind her diagnosis. I had wanted to be able to change her instead of receiving change myself.

“Penny and I might never talk about literature together. But I had to trust that we would continue to communicate love to each other. That the way she nestled against my chest and calmed under my touch would one day translate into words that said the same. And I had to trust that she would keep growing up and become even more who she was: bright, delightful, a joy. I had to trust that I, too, would keep growing up. It wasn’t hard to believe that love would keep changing me.”

I just noticed that A Good and Perfect Gift is currently for sale at $2.99 as an ebook, and I thought I should mention it is also available for one credit on Audible. I’m so grateful, seven years after those words were first published, to be able to say that Penny and I have continued to grow up and yes, love has kept changing me.

Tuesday, September 19, 2017

As a white person who grew up in neighborhoods with very little crime, the police and the court system seemed utterly trustworthy. Sure, mistakes were made sometimes but that’s just human, I thought.

When I was in college, I signed up to be a pen pal with a woman in prison. I corresponded with one woman for about a year, but we fell out of touch when she was moved from one prison to another and I couldn’t obtain her new address. Truth be told, I felt uncomfortable when she wrote about how she had been imprisoned unjustly. She described the situation behind her arrest, which came down to being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Her story didn’t shake my view of the courts or police work. I just assumed she was lying.

I signed up to correspond with another prisoner in my early twenties, and we established a longer friendship. She was a mom already, so she had wisdom and comfort to offer me when Penny was born and she loved telling me about her own teenage daughter’s accomplishments. She, too, described the details of her imprisonment in terms that made no sense to me. She admitted what seemed to me a very minor drug infraction. I knew plenty of people who had used drugs in high school and college. I even knew some who had sold them. None of them had ever gone to jail. Certainly not for a decade. The crime she described seemed parallel to those friends’, nothing worthy of all that time behind bars, all that time away from her daughter. Nothing worthy of naming her a felon for life. In this situation, because of the friendship that had developed, and because I had begun to learn a little more about how our criminal justice system can bend in unjust directions, I felt uncomfortable with the story not because I thought she was lying but because I thought she might be telling the truth.

For her to be telling the truth–that possessing a small amount of an illegal substance would take her away from her daughter and put her behind bars for a decade–didn’t just make my heart heavy for my friend. It disrupted my view of the world. Where was the justice in the incarceration of a young mom who screwed up? And what if there were hundreds and thousands of other women (and men) like my friend, who had committed crimes and yet were experiencing punishments that far outweighed the severity of the crime? Meanwhile, my friends from college who had done similar things were working in investment banks and going to law school. My college friends were white. My friend in prison was black.

But then she got out of prison. Her daughter graduated from high school with honors. They moved. We fell out of touch. And I buried my distrust of the system, needing to believe that this nation I love is really and truly a nation of liberty, a nation of justice, a nation for all.

I still very much believe in the principles of our nation, and I still believe we can live into those principles. But I also believe that the brokenness in our system is very real and amounts to real injustice disproportionately directed towards men and women of color. The book The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander was probably the most helpful read (though I have also heard that James Foreman’s Locking Up Our Own is worth reading and if you are a more visual person Ava Duverney’s film 13th summarizes a lot of The New Jim Crow but just can’t provide the same depth due to time constraints). Alexander details story after story that parallel my friend’s experience. For a shorter introduction to some of the problems with the system you can also check out an article from the Atlantic regarding plea bargains.

I still feel pretty paralyzed as a white person who enjoys the protections of the law and the courts. I don’t worry about minor infractions like driving over the speed limit. I am grateful for the sacrificial service so many men and women in uniform and in the legal profession offer to my fellow Americans. And yet I also deeply long for the same protections I enjoy to be distributed among communities of color. I long for people like my friend who was in prison to be given a second chance instead of being branded a felon for the rest of her life.

Monday, September 18, 2017

Do you put any intentional limits on your use of technology? Do you have an age when your kids get their own device?

We’ve been talking about it in our family–is it 12? 14? Is it a phone without internet connectivity? An iPad that can text but not call? I don’t bring my phone to the dinner table, and our kids have permission to call us out when we (too often) allow ourselves the distraction of “just quickly responding” to a text or email. When I try to be disciplined about putting away the phone for a time, and I find that we want to play music or check the weather or use the timer on it. I am contemplating a “rule” of ten hours in airplane mode–from 10pm to 6am–as a self-imposed limit since I find myself checking the New York Times website, Facebook, and email habitually before I turn out the light and (this is hard to admit) before I even turn on the light in the morning.

Over the weekend, I read an article about the Amish and how they are navigating some of the same waters and asking questions about how much, if any, they should allow the use of cell phones and computers in their workplaces (they seem pretty clear that these devices don’t belong at home, which is a lesson to me in itself). What struck me most in reading the article, however, was not the questions or even the different conclusions different Amish people reached. Rather, I was struck by the way they thought about their lives. One man, when talking about driving a horse and buggy instead of a car, said, “Not using cars is a way of keeping us together.” In other words, I don’t have anything against cars, per se. I just am committed to our community more than the efficiency that cars would allow. We don’t use cars because of what we are for, not because of what we are against.

Even though I plan to keep driving my car and using my cell phone, it was a good reminder to do so through the lens of what I am for: thoughtfulness, rest, peace, joy, family, friendship, contemplation, among other things. Then I can consider if/how technology serves those purposes.

(On a related note, if you haven’t read the widely read article from last month’s Atlantic “Have Cell Phones Destroyed a Generation?”, it’s worth reading right now. The bottom line is that higher rates of phone usage correlate in a remarkable way with unhappiness.)

All of these leads me to conclude that we will keep pushing back the time when our kids get their own personal devices, and that I need to implement a nighttime airplane mode on my phone. I am not against technology but I am for relationships.

September 15, 2017

“How Does Racism Relate to Privilege? And Other Thoughts on Boarding School, the Whole 30, and Julian of Norwich

As many of you know, I stopped blogging two years ago, mostly because blogging consumed the time that I had for writing, and I chose to write books instead of blog posts. But I still enjoy sharing thoughts with readers in a more immediate way, so I have been using my Facebook author Page to share book recommendations, reflections on culture, stories from our family, and updates about the books I’m working on. For those of you who don’t use Facebook, or who don’t want to check the page daily, I’m going to start posting a weekly compilation of those thoughts here on my website. This week includes links to articles about the relationship between privilege and racism, the history of a boarding school that admitted African American children as well as white children back in 1847, some thoughts on a new-ish eating program called the Whole 30, and words of comfort from Julian of Norwich in a time of calamity. I hope you enjoy!

As many of you know, I stopped blogging two years ago, mostly because blogging consumed the time that I had for writing, and I chose to write books instead of blog posts. But I still enjoy sharing thoughts with readers in a more immediate way, so I have been using my Facebook author Page to share book recommendations, reflections on culture, stories from our family, and updates about the books I’m working on. For those of you who don’t use Facebook, or who don’t want to check the page daily, I’m going to start posting a weekly compilation of those thoughts here on my website. This week includes links to articles about the relationship between privilege and racism, the history of a boarding school that admitted African American children as well as white children back in 1847, some thoughts on a new-ish eating program called the Whole 30, and words of comfort from Julian of Norwich in a time of calamity. I hope you enjoy!

Monday, September 11, 2017

As someone who spent the bulk of my educational years, and now the bulk of my adult years, in and around independent schools, I often wonder about the positive and negative that comes along with this type of education.

On a boarding school campus, there’s the possibility for lots of engagement with people from all over the country and the world (20 countries represented at the school where we live now, and that’s with only 300 students), the opportunities for more interaction with faculty when they also live on campus, and the opportunity for kids to grow in independence, away from parents, while also having structure and mentors to provide accountability and guidance. On the flip side, these schools are expensive. They are open only to those who get in, and many of them have a legacy of exclusion.

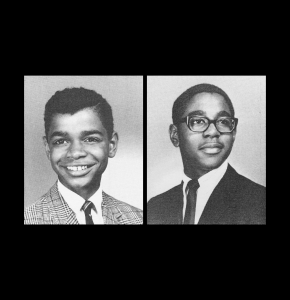

I’ll say more about the legacy of exclusion in a post tomorrow (one of the encouraging aspects of the school where we are now–the Gunnery–is our founder’s commitment to educating kids of all races and genders, starting in the 1840’s). But for today, I want to draw your attention to this article from the New York Times about the first African American students to attend Virginia Episcopal School, a boarding school in Lynchburg, VA. It raises great questions about motivation (Were these students admitted simply to benefit the white students or because they were considered worthy in their own right?), about possibilities (Even amidst some instances of awful discrimination and bullying, the graduates today still talk about the way this education allowed them to prosper, and some of them were exemplary leaders and students and demonstrated to themselves and their white peers the lies of the segregated South), and–more on this tomorrow–about what it means to work towards schools today that aren’t simply inviting students of color but creating spaces where students of color belong just as much as anyone else. “‘The Way to SurviveIt Was to Make A’s’”

Tuesday, September 12, 2017

I wrote yesterday about the legacy many independent schools carry of denying admission to people based upon race (or religion or gender). I am often inclined to forgive those wrongs with a simple, “They just didn’t understand.” “They didn’t know any better.”

But recently my husband, who is the headmaster of the Gunnery, an independent boarding school in Washington, CT, has been reading through the letters of the school’s founder, Frederick Gunn. Gunn was an abolitionist and a radical in many ways, but he was also a man who was trying to build a school, and he needed students to attend the school in order to succeed. Back in 1847, most people assumed that white and black children wouldn’t and shouldn’t go to school together.

As my husband tells it:

One day Mr. Gunn was asked by a prominent local whether he would be willing to admit the children of a black family who didn’t have other school options for their kids because no other schools would admit them. The man who asked Mr. Gunn, Henry Booth, admitted to Mr. Gunn that if Mr. Gunn admitted these students, “it might cause an excitement; it might cause many parents to take their children out; it might break up the school.”

Mr. Gunn, writing to his future wife to relate this interaction, says, “Immediately all our plans of happiness shot through my head; I saw them all dashed to the ground at one blow, and the period of our union postponed to an indefinite future; for, if I fail here, what am I to do? Where shall we find a home?”

Mr. Gunn admits that it’s possible that if he admits these kids, his school could fall apart and their dreams would be dashed. Then, Mr. Gunn writes, “On the other hand, I saw our brethren groping in ignorance, groveling in low debasement, unable to rise to the light which we enjoy, because they are crushed by this spirit of ferocious hate, without a friend and without a comforter, shut from the steamboat, the railroad car, from the school and college,”

And so, Mr. Gunn writes to Abigail, “I answered [Mr. Booth], of course, that I am no critic of skins; that I teach all who come to receive my instructions, and who conduct themselves in such a manner as to promote the ends of the institution; that I never can or will give way to this inhuman and infernal prejudice, — no, not for one hour!”

And if the consequence of admitting these students is that “I am compelled to relinquish my situation here because I cannot sell myself to the skin-aristocrats to help them in heaping contempt upon those whom God loves as well as he does you and me, — why, then so be it, so be it!”

It was clear to Mr. Gunn even 170 years ago that black children and white children deserved the same education because they had the same inherent dignity, the same inherent potential, and he was willing to forfeit his own position, his own dreams, in order to live out those principles.

As much as we are tempted to contextualize the moral wrongs of the past (and present), reading this again makes me recognize what our founders also named, that it is self-evident that all men (and women!) are created equal. And, I might add, it harms us all when we fail to live up to that truth. We have always known better. (For more about the Gunnery’s history)

Wednesday, September 13, 2017

Has anyone here tried the Whole 30?

Wikipedia calls it a fad diet, and I’m inclined to agree, BUT I’m also on Day 10 of a modified version of it. No dairy, grains, legumes, corn. I’ve opted for limited added sugar (I’m still putting honey in my tea and I’m not making every sauce from scratch) and for very limited alcohol (once a week one glass of wine on date night).

Anyway, the point of eating this way is to figure out what various foods do in our bodies. Do they increase joint pain or fatigue? Cause skin problems or digestive discomfort? And this isn’t really they way the founders talk about it, but the other point for me is to figure out how food functions emotionally and spiritually–does it cover up feelings and needs that might need deeper attention?

I’ve already figured out from a 30day alcohol fast last spring that alcohol makes me sick (sinus congestion) if it is allergy season or if I am stressed out. I’m curious to know whether dairy or gluten/grains have any negative effects. (I’m clear on their positive effects–the whole milk yogurt I used to eat every morning brings me enormous pleasure, and the gift of fresh bread, quinoa, granola and summer corn is hard to even put into words.)

Perhaps it is already clear that I’m not planing to stay on the Whole 30 forever, but the experience has also, and already, given me lots to think about. Food brings me a lot of pleasure and contentment and gratitude. On the one hand, it’s good to have to seek out a deeper source of joy and peace than yogurt and granola or a glass of wine. On the other hand, I am also reminded that we are humans who live in bodies. We don’t need a compact pill of nourishment or a tasteless shake. We need real food, not just to nourish us but as a part of the sweetness, the pleasure, the gift of living on this planet.

These 10 days have given me a chance to turn towards a deeper source of both peace and joy than the food I eat–peace and joy that is available no matter what my material circumstances. In the future, I want food to be a reminder of, not a replacement for, that same peace and joy.

And if you are in the slightest bit interested in thinking about things like this, you must read my friend Katherine Willis Pershey’s reflections on doing the Whole 30.

How about you? Have you ever fasted from something for Lent or for other reasons? What has it taught you about yourself?

Thursday, September 14, 2017

People are talking about the hurricanes and floods and threat of nuclear war, and for good reason asking “Where is God in the midst of all of this?” It’s not the first time we’ve asked the question, but the answers aren’t easy or obvious. I was so grateful to happen upon an interview with a scholar of Julian of Norwich as at least the beginning of a response to these questions:

I had heard of Julian before–she’s the first woman to have written anything in English that has survived, and she gave us the famous quotation that “all will be well, and all manner of things will be well” which quite frankly, never felt in any way satisfying to me until I heard this interview. Anyway, I learned from Mimi Dixon on this podcast that Julian lived in a town that lost 75% of their population during the plague, probably including her husband and children. The plague came to their town repeatedly and repeatedly decimated the population. If there was ever a time to question God’s goodness and love, God’s concern about human suffering, this was it.

Julian herself fell gravely ill and was considered to be on her deathbed. A priest came to pray last rites with her, but she wasn’t close enough to death yet so he left her with a crucifix and went on his way because so many others were dying all around. She lay with the crucifix for ten hours and experienced a series of “showings” in which she talked with Jesus about sin and suffering and was ultimately convinced of his enduring and faithful love for her and for all humankind.

Listening to this interview not only taught me a lot about the past, but it encouraged me for the here and now and made me want to read Julian’s work (here’s a link to a version of her Revelations of Divine Love in modern English). I hope you’ll have a chance to listen (or read) and be encouraged too.

Friday, September 15, 2017

I’ve read a number of articles this week about racial disparities in our country that are important for people like me (white, affluent) to read in order to understand our current political and social climate. Here are a few that will get you thinking:

Before I even share this article (What I Said When My White Friend Asked for My Black Opinion on Privilege), can I point out that it is written by a woman who founded a website called goodblacknews.com. First of all, how cool. Second of all, how sad that she needed to start that website—she explains why in the post.

Next, an article about real estate and the racial injustice embedded in our current system: (Real Estate and the Realities of Racial Injustice). Here’s the quotation that has kept me thinking: “Florida notes, “The federal government provides an estimated $200 billion in annual subsidies for home ownership via tax deductions for mortgage interest.” The deduction has remained remarkably popular, to the point that McCabe describes it as “one of the most sacrosanct public welfare programs.” More than that, if we account for indirect expenses, it may be that the subsidy costs the federal government as much as $600 billion per year. Calculated in this manner, it could be argued that federal government spends thirteen times as much on home ownership subsidies as it does on “housing assistance to those in need ($46 billion a year).” Rothstein corroborates that claim, noting that the popular rental assistance subsidy known as Section 8 functions not as an entitlement—in fact, the budget remains far too meagre: in 2015, while one million families used the vouchers, another six million qualified but went without because of insufficient budget appropriations. The tax deduction for property taxes and mortgage insurance, however, does act as an entitlement given “to middle-class (mostly white) homeowners” because it has no budgetary limitations.”

I am one of the homeowners who benefits from a government program (tax break/incentive), and I think it is compelling to think of that program as an entitlement program akin to public housing. What about you? Do you see these things as comparable?

Finally, an article about the legacy of racism in the North, which can all too often be overshadowed by the legacy in the South. On a side note, I was struck when researching my upcoming book by the fact that a plantation in the town where I grew up in North Carolina had procured socks and mittens from a clothing company 15 minutes away from where I now live in western Connecticut. In other words, the economy of the nation—North and South—was linked to slavery, and the legacy of racism can be found in all these places too: (The South Doesn’t Own Slavery).

September 9, 2017

Is Privilege Just about Race? (and other thoughts on kids, disability, and faith)

As many of you know, I stopped blogging two years ago, mostly because blogging consumed the time that I had for writing, and I chose to write books instead of blog posts. But I still enjoy sharing thoughts with readers in a more immediate way, so I have been using my Facebook author Page to share book recommendations, reflections on culture, stories from our family, and updates about the books I’m working on. For those of you who don’t use Facebook, or who don’t want to check the page daily, I’m going to start posting a weekly compilation of those thoughts here on my website. This week includes thoughts on how kids bring grace into our lives, hopeful futures for children with disabilities, a book recommendation, and questions about the nature of privilege.

As many of you know, I stopped blogging two years ago, mostly because blogging consumed the time that I had for writing, and I chose to write books instead of blog posts. But I still enjoy sharing thoughts with readers in a more immediate way, so I have been using my Facebook author Page to share book recommendations, reflections on culture, stories from our family, and updates about the books I’m working on. For those of you who don’t use Facebook, or who don’t want to check the page daily, I’m going to start posting a weekly compilation of those thoughts here on my website. This week includes thoughts on how kids bring grace into our lives, hopeful futures for children with disabilities, a book recommendation, and questions about the nature of privilege.

Tuesday, September 5, 2017

Does anyone else operate on a school-year schedule, and thus feel like September is the beginning of a new year? I have spent the past few weeks setting “goals” for the upcoming school year, which is more or less the same as setting new year’s resolutions in January. For me, those include spiritual, physical, and professional goals.

If any of you are thinking about things that you want to see change in the year ahead, I want to bring your attention to a new book (came out today) by Keri Wyatt Kent, called GodSpace: Embracing the Inconvenient Adventure of Intimacy with God. My review: “We have filled our homes with stuff, our calendars with activities, and our hearts with a desire for more.” Keri Wyatt Kent’s GodSpace invites us to declutter our hearts, our homes, and our calendars in order to make room for the inconvenient wonder of God’s presence. Kent tells stories from her own life and offers practical suggestions on how we can open ourselves up to God’s work in our homes, our communities, and the world. With humor, insight, and concrete examples, Keri Wyatt Kent has written a book that encourages me to make meaningful changes that will enable less space for disappointment and more space for God.

Wednesday, September 6, 2017

Yesterday Penny decided she wanted to start reading Small Talk. I should preface what happened next by saying that yesterday was also a day when I was grumpy. I snapped at Marilee for licking pesto off a knife. I snapped at Pen for not putting her homework back in its folder. William steered clear of me. So I found myself in front of the computer, trying to keep up with email, with Penny reading Small Talk next to me.

The first chapter takes place about four years ago, when the kids were so much younger and Marilee couldn’t pronounce “l” or “r” yet. It’s a day with a delayed opening for school, a day where we had a lovely time as a family that just as quickly became a grumpy shouting match.

As Penny read, she asked, “What does it mean that you clunked the guitar?” and I told her that I’m a pretty bad guitar player. She then asked, “Mom, what does it mean when you say, ‘They are the vehicles of grace’?” And I said, “Oh, so you know how God loves us even when we are grumpy and even when we are mean and messy and don’t do anything right? It means that God’s love, God’s forgiveness, comes into our lives even in the midst of those times. And it means that you all are often the way that grace comes in. It’s like you’re a car carrying God’s grace to me.”

She took my hand and squeezed it and smiled.Photo Credit: Chris Capozziello

Here’s the full quotation, which needless to say I needed to be reminded of yesterday: “For a long time, I thought my children were a distraction from the work God was doing in my life and in the world around me. I am starting to realize they are the work God is doing in my life. They are the invitation to give, to receive, to be humbled, to grow. They are the vehicles of grace.”

In case you want to read more, here’s the link.

Thursday, September 7, 2017

As the school year begins and many parents–especially, perhaps, parents of children with special needs–begin to wonder about their children’s futures, this article is a wonderful reminder of the world of possibilities available if only we stop and listen and respond to who our kids are rather than who we (or their peers, or school system, or teachers) expect them to be: Looking Into the Future for a Child with Autism.

Friday, September 8, 2017

Two questions this morning. One, does “privilege” consist of racial demarcations alone (“white privilege”) or is it more than that? Is privilege a Venn diagram that includes race, wealth, religion, genetics, family, and/or education?

Second question for the morning: to what degree is privilege (see first question) about morality? I am thinking about the conclusion of an article I read in the New York Times this morning about wealthy people who try to downplay their wealth: “we should talk not about the moral worth of individuals but about the moral worth of particular social arrangements. Is the society we want one in which it is acceptable for some people to have tens of millions or billions of dollars as long as they are hardworking, generous, not materialistic and down to earth? Or should there be some other moral rubric, that would strive for a society in which such high levels of inequality were morally unacceptable, regardless of how nice or moderate its beneficiaries are?”

What do you think? Is it acceptable for some people to have a ton of money? If not, what should be done about it?

September 1, 2017

What Going to Middle School Taught Me about Love (and other reflections)

For eight years, I blogged regularly. It started as a once a week post about our family. In time I moved to Beliefnet, then Patheos, then Christianity Today, where I was asked to write at least three posts every week. Eventually I realized that I could either blog or write books, but I couldn’t do both at the same time. I abandoned the blogging and for the past few years have focused on the longer-form writing work of articles and a new book. But last spring I realized that I still have thoughts that might be worth passing along to readers–articles I read that you would find interesting, reflections on Scripture, books to recommend, stories about our family, and updates on White Picket Fences (my upcoming book). So I began posting those snippets of recommendations and reflections on my Facebook Page. It was like a mini-blog. A few minutes every morning to share something I found interesting or inspiring or thought provoking with readers who are interested in faith, family, disability, and/or culture. I’ve decided now to compile those daily thoughts into one weekly blog post for people who aren’t on Facebook or who don’t want to check my page every day. If you read this and have any suggestions about how to make it more reader-friendly, please let me know. Meanwhile, here’s this week’s thoughts on middle school, the love of God, and some books and articles worth reading.

For eight years, I blogged regularly. It started as a once a week post about our family. In time I moved to Beliefnet, then Patheos, then Christianity Today, where I was asked to write at least three posts every week. Eventually I realized that I could either blog or write books, but I couldn’t do both at the same time. I abandoned the blogging and for the past few years have focused on the longer-form writing work of articles and a new book. But last spring I realized that I still have thoughts that might be worth passing along to readers–articles I read that you would find interesting, reflections on Scripture, books to recommend, stories about our family, and updates on White Picket Fences (my upcoming book). So I began posting those snippets of recommendations and reflections on my Facebook Page. It was like a mini-blog. A few minutes every morning to share something I found interesting or inspiring or thought provoking with readers who are interested in faith, family, disability, and/or culture. I’ve decided now to compile those daily thoughts into one weekly blog post for people who aren’t on Facebook or who don’t want to check my page every day. If you read this and have any suggestions about how to make it more reader-friendly, please let me know. Meanwhile, here’s this week’s thoughts on middle school, the love of God, and some books and articles worth reading.

Friday, September 1, 2017

Today is day five of middle school for Penny. She has weathered it better than I have–great attitude, tremendous excitement about the prospect of hot lunch (which wasn’t available daily at her elementary school), multiple opportunities to show us that she really and truly is growing up and can make decisions for herself and can keep a 7 day rotating class schedule in her head without a problem. She got sad once because her two best friends aren’t at school any longer, but even from that she bounced back pretty quickly. I, on the other hand, cried in my minivan when I got a call from the school nurse yesterday because Penny had spilled on herself and didn’t have a change of clothes and I felt like I had failed her. Penny told me about it later with her usual matter-of-fact reporting. “It was no big deal, Mom.”

Any transition for any kid has the potential to raise anxiety levels for everyone. I suspect that for parents of kids with special needs, once again this process is magnified. For me, old questions about Penny’s future–questions that I have been able to put off for the past five years because her life has been stable and she has been growing and loving life–have resurfaced. Will she get a job? Will she be able to live independently? Will she make new friends? Will she be happy?

Yesterday, before the phone call from the nurse, I was thinking about a verse from a Psalm, “Whoever is wise, let him heed these things and consider the great love of the Lord” (Psalm 107:43). Wisdom–knowledge combined with goodness and hope and peace–comes from considering, from pausing to think about and remember and rest in, the great love of the Lord. I needed to go back in time to think about God’s love for Penny, God’s love for me, God’s love for this world. First I was reminded of a Psalm that came to me when she was one and needed heart surgery: “The Lord protects the simple hearted… Be at rest once more, O my soul, for the Lord has been good to you” (Psalm 116:6-7, and for the whole story you’ll need to read A Good and Perfect Gift). Then I was reminded of the clear promise I heard when we were decided whether to move to Connecticut, “Even if you make the wrong decision, I will take care of Penny.” (For that whole story, see Small Talk!) And finally, of the verse that our pastor read at her dedication as an infant: “She is like a tree planted by streams of water, which yields its fruit in season and whose leaf does not wither. Whatever she does prospers” (Psalm 1:3).

Nothing has changed about this particular week. Penny still has scoliosis. She is still in transition. She still has to find new friends and figure out a rotating schedule and changing clothes for gym and a combination lock on her locker with only three minutes between classes and getting on a bus with high school kids.

After my tears in the minivan, my mind went back to that Psalm–consider the great love of the Lord– and I thought, that’s my job right now. Not to get her backpack packed perfectly every morning. Not to manipulate a new friendship for her. Not to work harder to straighten her back. Not to make sure she looks great or does well in school. But to consider the great love of the Lord, for me and for our daughter, and to rest in that unfailing, enduring, never-giving-up love.

Thursday, August 31, 2017

One of the perks of being an author is that people send me books for free. I have a stack on my desk right now that I’m eager to look through, but there is one that I want to tell you about right now. I read this book in manuscript form a few months ago, and I am eager to read it again. It’s written by my friend, author and blogger Sara Hagerty, and it is called Unseen: The Gift of Being Hidden in a World That Loves to be Noticed. Here’s what I wrote after I read it: “Sara Hagerty has written a beautiful and powerful book that I will give to any Christian who wonders what God is up to in times of trial, stress, or monotony. It might seem as though Sara’s story won’t connect–she’s managed four international adoptions, for starters–and yet Unseen managed to draw forth the desires and fears and dreams we have in common. I will return to this book in the future when I need a reminder of God’s faithfulness, God’s purposes, and God’s love for me.” And I will give this book to many friends who feel alone or as if they are living lives that fade into the background, lives that don’t matter, lives that aren’t significant because of small children or no children or hopes and dreams that haven’t been realized. I highly recommend this beautiful book.

Wednesday, August 30, 2017

This story is worth reading in full, but the short version is that a 20-year old white man named Abraham participated in an act of hateful vandalism against a mosque in his community. When he went to jail and was awaiting trial, he wrote the mosque to express his remorse, and the Muslim leaders in the community responded with forgiveness and compassion. They even petitioned for leniency in sentencing. Again, I recommend reading the whole article but want to share this conclusion as a beacon of hope and a reminder of who we are, at our best, as a nation:

“After he got out of jail, Abraham posted a note on Facebook.

“Well, I’m home now,” he wrote. “I just want to say thank you to all those who have been supporting me and a big thanks to the guys at the mosque who have been supportive and helpful and I pray blessings over them.”

The next day, he saw a response from Wasim, Hisham’s son.

“Bro move on with life we forgave you from the first time you apologized don’t let that mistake bring you down,” he had written. And then, Abraham’s favorite line: “I speak for the whole Muslim community of fort smith we love you and want you to be the best example in life we don’t hold grudges against anybody!”

It was the nicest thing anyone had ever said to him.” – At an Arkansas Mosque, a Vandal Spreads Hate and Finds Mercy

Tuesday, August 29, 2017

Penny started middle school yesterday. She got on a bus with 6th-12th graders, walked into a big new school, went to her seven different classes with seven different teachers, discovered that one of her best friends moved away over the summer, came home, went to an orthopedist appointment where we found out her scoliosis has progressed, ate a big dinner of spaghetti bolognese, and fell soundly asleep. My attitude about her friend: To Penny, “Oh that’s so sad that your friend moved away!” Penny’s attitude: “I have plenty of friends, Mom.” My attitude about her scoliosis (To Peter), “I’m so discouraged that her scoliosis progressed.” Penny’s attitude: “The goal is to prevent surgery so I’ll just wear my brace more.” She understands perseverance better than I do, and I marvel at her positive perspective.

It reminded me of this story that a friend shared recently, of Andrew Harris, a man with Down syndrome who recently climbed Grand Teton:

The Story Behind the First Person With Down Syndrome to Climb the Grand

Andrew Harris and Penny both show me a little bit about what it takes to accomplish goals and thrive in life. I am grateful for them both.

Monday, August 28, 2017

Are you a churchgoer? If so, why do you go?

If not, why not? Church is finally a part of our family’s regular weekly rhythm (for years we went, but it still surprised me that we got out of bed every week and went there with our squirmy kids and tired bodies and sat through services that were sometimes lovely and other times boring and sometimes felt pointless because we were just shushing and rocking babies the whole time) and we are so grateful for the invitation to worship God, rest our souls, connect to our community, and participate in something bigger than ourselves as a family. I appreciated Marilyn McIntyre’s take on this question too: CHOOSING CHURCH: There are lots of reasons to avoid church, but here are the reasons to look again.

Sunday, August 24, 2017

The original idea for the summer was to spend a lot of time with our children and also edit the book I’m working on, White Picket Fences: Confessions of Privilege. I thought I needed a few hours for each chapter, so I could get through two chapters a week without disrupting family time too much. By this point in the summer, I was supposed to be done with the second draft and ready to revise the whole thing. Well, let’s just say it didn’t go as planned. I threw away one chapter altogether. I moved chapters ten and eleven and turned them into chapters one and two. I wrote an introduction. I combined chapters one and twelve to become chapter six. I’ve still got six chapters left to edit (or, though I hope not, rewrite) and my deadline is fast approaching. I took some solace in this Atlantic article’s description of a somewhat similar writing process, and I can only hope and pray that this second draft is a lot closer to the final draft than the first one was…

“The first draft is for the writer. The second draft is for the editor. The last draft is for the reader.” – The Book He Wasn’t Supposed to Write: A best-selling author submits a draft to his editor. Hijinks ensue.

May 25, 2017

Why We Must Insist Upon Knowledge Tethered to Love (Reflection Three on Love and Knowledge and a Baby Girl with Down Syndrome)

I was invited to share some thoughts on disability and theology with the student body of St. Paul’s School, a boarding school in Concord, New Hampshire. I offered three reflections on the theme of love and knowledge, along with three readings. I have modified them slightly for this blogging format, but I wanted to share the thoughts with you. Here’s the third post (and here are links to the first and second):

One of the ways we combine love and knowledge is by putting facts in the context of experience. I’ve included photos of Penny and our family here to demonstrate what the abstract factual knowledge about Down syndrome looks like in the context of love.

If I speak in the tongues of men or of angels, but do not have love, I am only a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal. If I have the gift of prophecy and can fathom all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have a faith that can move mountains, but do not have love, I am nothing. If I give all I possess to the poor and give over my body to hardship that I may boast, but do not have love, I gain nothing.

Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It does not dishonor others, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres.

Love never fails. But where there are prophecies, they will cease; where there are tongues, they will be stilled; where there is knowledge, it will pass away. For we know in part and we prophesy in part, but when completeness comes, what is in part disappears. When I was a child, I talked like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child. When I became a man, I put the ways of childhood behind me. For now we see only a reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known.

And now these three remain: faith, hope and love. But the greatest of these is love.

–the Apostle Paul, 1 Corinthians 13

Reflection Three:

Sometimes I wonder whether my love for my daughter discredits me when I try to argue for her value or for the value of human beings with Down syndrome and other disabilities all over the world. Because of Penny, I am biased, and I know from my many years of schooling that arguments can seem less valid when they arise from a position of bias. I have been taught to divorce love from knowledge and to argue positions based upon facts alone.

Sometimes I wonder whether my love for my daughter discredits me when I try to argue for her value or for the value of human beings with Down syndrome and other disabilities all over the world. Because of Penny, I am biased, and I know from my many years of schooling that arguments can seem less valid when they arise from a position of bias. I have been taught to divorce love from knowledge and to argue positions based upon facts alone.

There’s some validity to this approach. If I argue a point based only upon emotion, only upon sentimental allegiances, then I run the risk of ignoring facts or distorting truth. Love without knowledge can lead to destruction.

But I am learning that knowledge without love, like St. Paul said in the reading we just heard, is also problematic. Paul calls knowledge without love a clanging cymbal, a useless and irritating noise. He says wisdom and insight, without love, is nothing. We’ve all met uptight religious people who know the moral rules but don’t love the people the moral rules are meant to protect and liberate. Such knowledge without love leads to restriction, repression, and even abuse. Outside of the religious sphere, knowledge without love can lead to war (think of any dictator). Knowledge about how to use resources from our earth without love for the earth has led to destruction of air and water and forests. The list could go on.

Love without knowledge leads to destruction by way of sentimentality. Knowledge without love leads to destruction by way of data points.

Penny and her family at Epcot, or what love and knowledge together look like

But what happens when knowledge and love walk hand in hand? What would happen in your life if you were known—in all your fears and doubts and dreams and gifts—and you were loved? What if you were accepted as valuable and significant not because of the grades you got or the goals you scored or the community service you offered? What if you were accepted as valuable simply because the truth at the foundation of the universe is love, and all our knowledge of ourselves and one another and the world around us is incomplete without love at its core?

When it comes to usefulness, Penny’s life might not measure up, and mine might. But our lives are equally valuable, equally filled with potential to give and receive love from our fellow human beings, equally filled with potential to bring more light and life, freedom and joy, hope and healing to the world. What if the same is true of you?

Having a child with disabilities has expanded my capacity to love and value others, but it has also expanded my ability to believe that I am loved not because of my achievements but because of my humanity, in all my vulnerabilities and weaknesses and beauty and gifts. You too are limited and needy, gifted and glorious. And your value comes not because of your SAT scores or your likelihood of becoming an investment banker someday. Your value—like Penny’s, like mine—comes because you are known and you are loved, with a love that is patient and kind, a love that always hopes, always protects, always trusts, always perseveres. Our value comes because we are loved by a love that never fails.

Why We Must Insist Upon Knowledge Tethered to Love (Reflection Three on Love and Knowledge and a Baby Girl with Down Syndrome)

I was invited to share some thoughts on disability and theology with the student body of St. Paul’s School, a boarding school in Concord, New Hampshire. I offered three reflections on the theme of love and knowledge, along with three readings. I have modified them slightly for this blogging format, but I wanted to share the thoughts with you. Here’s the third post (and here are links to the first and second):

One of the ways we combine love and knowledge is by putting facts in the context of experience. I’ve included photos of Penny and our family here to demonstrate what the abstract factual knowledge about Down syndrome looks like in the context of love.

If I speak in the tongues of men or of angels, but do not have love, I am only a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal. If I have the gift of prophecy and can fathom all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have a faith that can move mountains, but do not have love, I am nothing. If I give all I possess to the poor and give over my body to hardship that I may boast, but do not have love, I gain nothing.

Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It does not dishonor others, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres.

Love never fails. But where there are prophecies, they will cease; where there are tongues, they will be stilled; where there is knowledge, it will pass away. For we know in part and we prophesy in part, but when completeness comes, what is in part disappears. When I was a child, I talked like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child. When I became a man, I put the ways of childhood behind me. For now we see only a reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known.

And now these three remain: faith, hope and love. But the greatest of these is love.

–the Apostle Paul, 1 Corinthians 13

Reflection Three:

Sometimes I wonder whether my love for my daughter discredits me when I try to argue for her value or for the value of human beings with Down syndrome and other disabilities all over the world. Because of Penny, I am biased, and I know from my many years of schooling that arguments can seem less valid when they arise from a position of bias. I have been taught to divorce love from knowledge and to argue positions based upon facts alone.

Sometimes I wonder whether my love for my daughter discredits me when I try to argue for her value or for the value of human beings with Down syndrome and other disabilities all over the world. Because of Penny, I am biased, and I know from my many years of schooling that arguments can seem less valid when they arise from a position of bias. I have been taught to divorce love from knowledge and to argue positions based upon facts alone.

There’s some validity to this approach. If I argue a point based only upon emotion, only upon sentimental allegiances, then I run the risk of ignoring facts or distorting truth. Love without knowledge can lead to destruction.

But I am learning that knowledge without love, like St. Paul said in the reading we just heard, is also problematic. Paul calls knowledge without love a clanging cymbal, a useless and irritating noise. He says wisdom and insight, without love, is nothing. We’ve all met uptight religious people who know the moral rules but don’t love the people the moral rules are meant to protect and liberate. Such knowledge without love leads to restriction, repression, and even abuse. Outside of the religious sphere, knowledge without love can lead to war (think of any dictator). Knowledge about how to use resources from our earth without love for the earth has led to destruction of air and water and forests. The list could go on.

Love without knowledge leads to destruction by way of sentimentality. Knowledge without love leads to destruction by way of data points.

Penny and her family at Epcot, or what love and knowledge together look like

But what happens when knowledge and love walk hand in hand? What would happen in your life if you were known—in all your fears and doubts and dreams and gifts—and you were loved? What if you were accepted as valuable and significant not because of the grades you got or the goals you scored or the community service you offered? What if you were accepted as valuable simply because the truth at the foundation of the universe is love, and all our knowledge of ourselves and one another and the world around us is incomplete without love at its core?

When it comes to usefulness, Penny’s life might not measure up, and mine might. But our lives are equally valuable, equally filled with potential to give and receive love from our fellow human beings, equally filled with potential to bring more light and life, freedom and joy, hope and healing to the world. What if the same is true of you?

Having a child with disabilities has expanded my capacity to love and value others, but it has also expanded my ability to believe that I am loved not because of my achievements but because of my humanity, in all my vulnerabilities and weaknesses and beauty and gifts. You too are limited and needy, gifted and glorious. And your value comes not because of your SAT scores or your likelihood of becoming an investment banker someday. Your value—like Penny’s, like mine—comes because you are known and you are loved, with a love that is patient and kind, a love that always hopes, always protects, always trusts, always perseveres. Our value comes because we are loved by a love that never fails.

What if Usefulness is Not the Measure of our Humanity? (Reflection Two on Love and Knowledge and a Baby Girl with Down Syndrome)

Penny and her family at Epcot, or what love and knowledge together look like

I was invited to share some thoughts on disability and theology with the student body of St. Paul’s School, a boarding school in Concord, New Hampshire. I offered three reflections on the theme of love and knowledge, along with three readings. I have modified them slightly for this blogging format, but I wanted to share the thoughts with you. Here’s the second post (and here are links to the first and third):

One of the ways we combine love and knowledge is by putting facts in the context of experience. I’ve included photos of Penny and our family here to demonstrate what the abstract factual knowledge about Down syndrome looks like in the context of love.

Paul says in 1 Corinthians 1 that God has chosen the weak, the foolish and the crazy to shame the clever and the powerful; he has chosen the most despised, the people right at the bottom of society. Through this teaching we see a vision unfold in which a pyramid of hierarchy is changed into a body, beginning at the bottom. One might ask if that means Jesus loves the weak more than the strong. No; that is not it. The mystery of people with disabilities is that they long for authentic and loving relationships more than power. They are not obsessed with being well-situated in a group that offers acclaim and promotion. They are crying for what mattes most: love. And God hears their cry because in some way they respond to the cry of God, which is to give love.

–Jean Vanier, Living Gently in a Violent World

Reflection Two:

A few months ago, I was listening to the poet Michael Longley in an interview on NPR with Krista Tippett. At one point he said, “Poetry is useless,” and he wasn’t kidding. He went on to say, “Poetry is useless, but it has great value.” I thought about what poetry has to offer—beauty, peace, insight into the human condition, questions about meaning and purpose, a connection to something transcendent and bigger than ourselves. And then my mind moved from poetry to people.

A few months ago, I was listening to the poet Michael Longley in an interview on NPR with Krista Tippett. At one point he said, “Poetry is useless,” and he wasn’t kidding. He went on to say, “Poetry is useless, but it has great value.” I thought about what poetry has to offer—beauty, peace, insight into the human condition, questions about meaning and purpose, a connection to something transcendent and bigger than ourselves. And then my mind moved from poetry to people.

Our culture is constructed around an idea that people need to be useful in order to be considered valuable. They need to be able to solve problems. They need to work in a productive—which is to say, economically viable—way. They need to not impose a financial, emotional, or legal burden on others. Our culture prizes usefulness.

We see this exaltation of usefulness in the way we reward hard work that achieves good grades, athletic accomplishments, and high-salaried jobs. So we approach learning not so much as an opportunity to explore notions of truth and beauty and justice but rather as an economic problem in which we go to the best schools so we can get the best job so we can make the most money so we can be independent, so that we will not need other people.

In our culture, we don’t only see the exaltation of usefulness. We also see the disdain of uselessness. Instead of honoring the wisdom of elderly people, we see them as burdens who take away resources from the rest of the population. Instead of wondering what people with intellectual disabilities have to offer, we for many years shuttled them to institutions, and we now offer women the option of terminating any pregnancy in which the fetus has Down syndrome or other genetic conditions. We fear or shun people with mental illness instead of believing they might be able to offer insights into our common human condition.

I have often succumbed to this line of thinking, assuming that my value as a human being comes from my usefulness, from my good grades and my awards and high job performance reviews. But after Penny was born, two things happened.

One, I started to meet people with Down syndrome and other intellectual disabilities, and over time I started to recognize not just their needs—things like therapy or doctors visits or help with cooking dinner—but also their gifts. I discovered Jean Vanier, founder of the L’Arche communities where adults with intellectual disabilities and typical adults live side by side, and author of numerous books. I also read books by Henri Nouwen, a Yale Professor who decided to move to a L’Arche community and live among adults with intellectual disabilities.

One, I started to meet people with Down syndrome and other intellectual disabilities, and over time I started to recognize not just their needs—things like therapy or doctors visits or help with cooking dinner—but also their gifts. I discovered Jean Vanier, founder of the L’Arche communities where adults with intellectual disabilities and typical adults live side by side, and author of numerous books. I also read books by Henri Nouwen, a Yale Professor who decided to move to a L’Arche community and live among adults with intellectual disabilities.

Nouwen, whose entire life had been built upon his usefulness as an intellectual, began to recognize how much he needed to know that he was loved not because he was useful, but because he was valuable. Imagine meeting someone who doesn’t care about your grades or what college you’re going to or what exclusive internship you got for the summer. Imagine that person seeing beneath all the layers of achievement, and loving you. That’s what happened when Henri Nouwen spent years with Adam, a young man who had no regard for Nouwen’s academic credentials, a young man who needed Nouwen’s help for basic tasks like bathing and eating, a young man who was able to communicate love and care for Nouwen in a way none of his fellow intellectuals had ever been able to do.

I recognized myself in Henri Nouwen, and I too began to see the poverty of the intellect when the intellect was not guarded and informed by love.

At the same time that I was reading these books and meeting adults with Down syndrome, I also was becoming Penny’s mother. My knowledge about what she might or might not be able to do, what diseases and vulnerabilities might slow her down, what likelihood she had of being useful in the world, my knowledge became intertwined with my love for her, my delight in her, my gratitude for her.

I wrote an essay for the New York Times when I was pregnant with our third child about how I had decided not to pursue prenatal testing because I would welcome another child with Down syndrome. Although many people expressed support of my perspective, others commented on how it was unethical of me to even consider bringing another child with Down syndrome into the world because of the burden that child would place upon his or her family and society. The logic went something like this: If they can’t provide for themselves, then they shouldn’t exist. If they are too vulnerable, too needy, then they are useless, and we have no place for them.

I wrote an essay for the New York Times when I was pregnant with our third child about how I had decided not to pursue prenatal testing because I would welcome another child with Down syndrome. Although many people expressed support of my perspective, others commented on how it was unethical of me to even consider bringing another child with Down syndrome into the world because of the burden that child would place upon his or her family and society. The logic went something like this: If they can’t provide for themselves, then they shouldn’t exist. If they are too vulnerable, too needy, then they are useless, and we have no place for them.

But what if usefulness is not the measure of our humanity? And what if one of the most important things Penny and other people with intellectual disabilities have to offer is the affirmation that our value as human beings arises from our belovedness, not our usefulness? What if to be human means to be loved, and what if this is the most important truth for any of us to ever learn?

What if Usefulness is Not the Measure of our Humanity? (Reflection Two on Love and Knowledge and a Baby Girl with Down Syndrome)

Penny and her family at Epcot, or what love and knowledge together look like

I was invited to share some thoughts on disability and theology with the student body of St. Paul’s School, a boarding school in Concord, New Hampshire. I offered three reflections on the theme of love and knowledge, along with three readings. I have modified them slightly for this blogging format, but I wanted to share the thoughts with you. Here’s the second post (and here are links to the first and third):

One of the ways we combine love and knowledge is by putting facts in the context of experience. I’ve included photos of Penny and our family here to demonstrate what the abstract factual knowledge about Down syndrome looks like in the context of love.

Paul says in 1 Corinthians 1 that God has chosen the weak, the foolish and the crazy to shame the clever and the powerful; he has chosen the most despised, the people right at the bottom of society. Through this teaching we see a vision unfold in which a pyramid of hierarchy is changed into a body, beginning at the bottom. One might ask if that means Jesus loves the weak more than the strong. No; that is not it. The mystery of people with disabilities is that they long for authentic and loving relationships more than power. They are not obsessed with being well-situated in a group that offers acclaim and promotion. They are crying for what mattes most: love. And God hears their cry because in some way they respond to the cry of God, which is to give love.