Aperture's Blog, page 99

July 12, 2018

The Threat of Being Seen

In her latest series, Alex Prager conjures the drama of Golden Age Hollywood.

By Rebecca Bengal

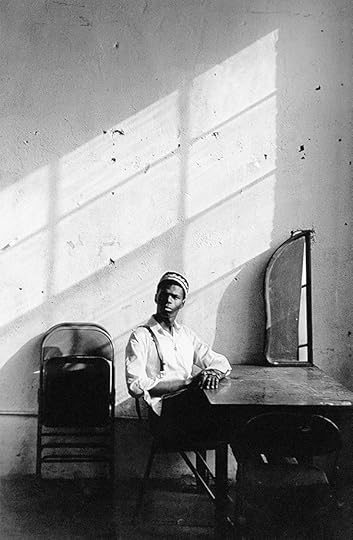

Mark Williams and Sara Hirakawa, Alex Prager, 2017

© the artists

When Alex Prager first began teaching herself photography, at the age of twenty-one, in 2000, printing black-and-white pictures in a home darkroom in Koreatown, Los Angeles, she’d hang them in the laundry room of her apartment building. Some prints disappeared; this was intentional. “I was curious to find out what people liked, which pictures they were drawn to,” Prager says from her studio in LA. Since those formative days, the artist’s work has radically transformed—most visibly in her emergent predilection for lurid, captivating color and a consciously narrative approach. Prager is known for photographing psychological, hypervivid, theatrically constructed scenes that evoke stills from classic Hollywood films, as evident in her new monograph Silver Lake Drive (2018). Cinematic and filmic are adjectives frequently applied to Prager’s photographs, but for Prager that means more than a purely aesthetic quality. “It’s about sparking a story in peoples’ minds,” she says. “I’m most interested in the way people connect to my work based on something that happened to them, on life experiences I’ve never had. For me, emotion trumps everything else in the picture.”

Alex Prager, Hand Model, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

Over the years, Prager’s work has earned comparisons to Cindy Sherman, Philip-Lorca diCorcia, and filmmaker Douglas Sirk. When citing her influences, it’s filmmakers she mentions first—Maya Deren, Federico Fellini, Jean-Luc Godard, Sidney Lumet. When her work was featured in the Museum of Modern Art’s New Photography 2010 exhibition, Prager debuted her first short film, Despair (2010), and the earliest images from her dynamic and tableau-like photographic series Face in the Crowd (2013), which contain so many interworking storylines that they give the sensation of being moving pictures, in the purest sense of the words. Among Prager’s other abiding influences are the films Jaws (1975) and The Wizard of Oz (1939); she identifies with their psychological, visceral depictions of crowds.

Alex Prager, Radio Hill, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

With Radio Hill (2017), shot from above, the viewer is given an omniscient overview of the bizarre constructs and strange, heightened characters in the street below: a woman in curlers walks through the rain with a half-eaten hotdog; a cop brandishes an ice-cream cone; three smartly dressed men, all in fedoras, look as if they’ve wandered in from some other era. “I’m looking at real life and figuring out how to amplify and exaggerate and add humor and drama and make it more palatable,” Prager says. And yet, in this image, she directs emotional attention to her main character, the lone figure in the picture who gazes upward and toward the camera, her anxiety palpable, aware of having been seen.

Alex Prager, Cats, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

The thread, and threat, of seeing and being seen is one Prager continues to explore in photographs of crowds, including ones composed of nonhumans, as in Cats (2017), and in short films, as with the haunting La Grande Sortie (2016), which stars Émilie Cozette as a ballerina who becomes overwhelmed by her awareness of her audience. Film, Prager explains, enables her to approach still photography in novel directions, incorporating a narrative sense of interconnectedness in her pictures in literal ways too. “I’m fascinated with finding ways of bringing these fabricated worlds together,” Prager says.

Rebecca Bengal is a writer based in New York.

Read more from Aperture Issue 231, “Film & Foto,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post The Threat of Being Seen appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 11, 2018

The Radical Poetics of David Wojnarowicz

A preview of the Whitney Museum’s survey of the iconoclastic New York artist.

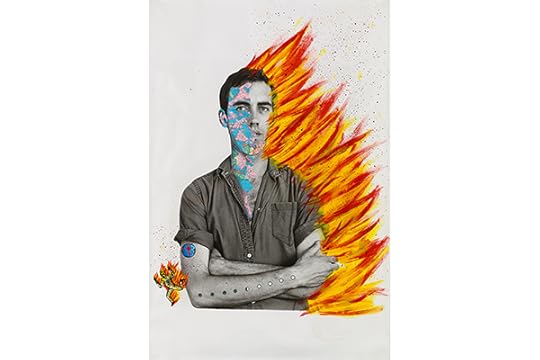

David Wojnarowicz with Tom Warren, Self-Portrait of David Wojnarowicz 1983–84Courtesy the collection of Brooke Garber Neidich and Daniel Neidich

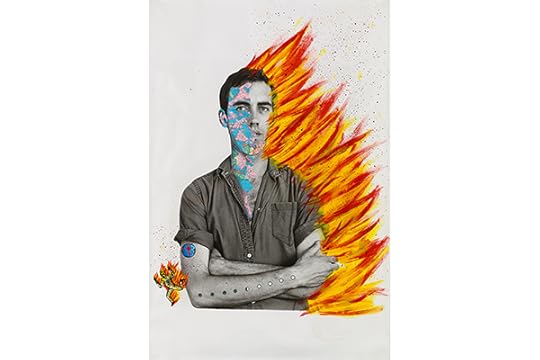

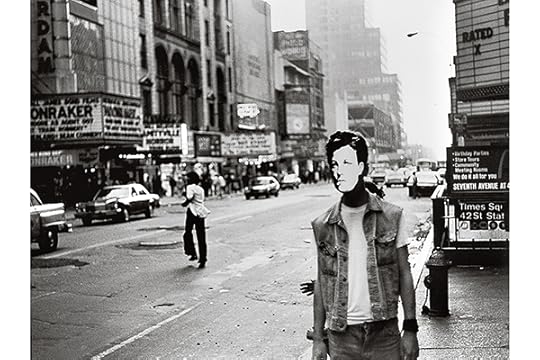

David Wojnarowicz, Arthur Rimbaud in New York, 1978–79, 1990Courtesy the estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W, New York

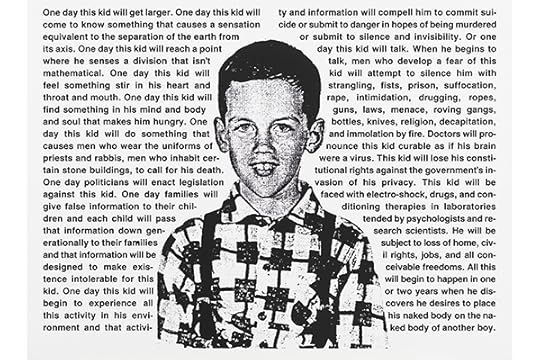

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (One day this kid . . .), 1990Courtesy the estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W, New York

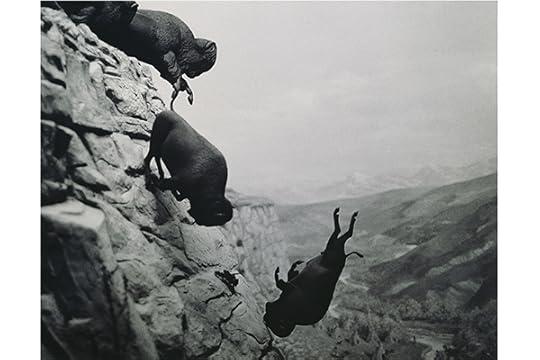

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled, 1988–89Courtesy the estate of David Wojnarowicz, P.P.O.W, New York, and Second Ward Foundation

David Wojnarowicz, Arthur Rimbaud in New York, 1978–79, 1990Courtesy the estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W, New York

The first major monographic exhibition of David Wojnarowicz’s work will bring his artistic output—including photo-text collages—to a new generation. “Few people are familiar with the visual side of his unfortunately short career,” says exhibition cocurator David Kiehl. “Wojnarowicz used the camera as other artists would use a sketchbook: a source for images to be used and readapted within his work, as well as an early tool—even if borrowed—to express visually his literary notions.” In the late ’70s, Wojnarowicz photographed himself and his friends around New York with a picture of Arthur Rimbaud’s face covering each of their own—a conceptual intervention. But the series is also personal: Wojnarowicz strongly identified with the French poet, who was born almost exactly one hundred years before him and, like Wojnarowicz, was gay.

David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night is on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, from July 13–September 30, 2018.

The post The Radical Poetics of David Wojnarowicz appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

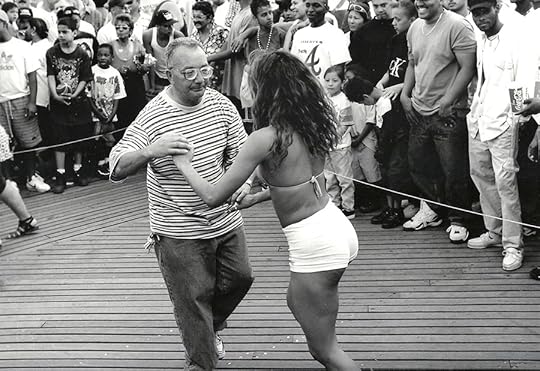

Jamel Shabazz: On the Streets

Join Jamel Shabazz for a two-day workshop available to photographers of all levels. Shabazz, best known for his iconic photographs of New York City during the 1980s, will teach photographers the necessary skills one must have when photographing on the street. During the first day, participants will view the work of noted street photographers and images created by prominent writers. Participants will then venture onto the streets of Midtown Manhattan, learning various aspects of street photography. On the second day, participants will review each other’s work and have a discussion about the experiences and challenges they faced when photographing.

Some of the areas that will be discussed during the workshop are preparation, themes, composition, body language, techniques, and career opportunities.

No prior knowledge is needed. Participants should come with an open mind.

Jamel Shabazz is a documentary, fashion, and street photographer who has authored eight monographs. His work has been exhibited in Italy, France, Korea, Turkey, Germany, Ethiopia, Brazil, and Japan and throughout the United States. Shabazz’s work is housed within the permanent collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, and the Bronx Museum of the Arts. Shabazz was the 2018 recipient of the Gordon Parks Documentary Photographer award.

Image: Jamel Shabazz, Dancers, Brooklyn, NY. 1997. Courtesy of Jamel Shabazz. All rights reserved.

div.important {

background-color: #eeeff3;

color: black;

margin: 20px 0 20px 0;

padding: 20px;

}

Objectives:

Become comfortable with photographing people on the street

Learn how to prepare and compose images

Leave with a better understanding of street photography

Materials to bring:

Participants must bring a digital camera to use during the workshop

Tuition:

Tuition for this two-day workshop is $500 and includes lunch and light refreshments for both days.

Currently enrolled students and Aperture Members at the $250 level and above receive a 10% discount on workshop tuition. Please contact education@aperture.org for a discount code. Students will need to provide proper documentation of enrollment.

REGISTER HERE

Registration ends on Wednesday, October 10

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

GENERAL TERMS AND CONDITIONS

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements. Please contact us at education@aperture.org.

If participants choose to purchase Aperture publications during the workshop they will receive a 20% discount. Aperture Members of all levels will receive a 30% discount.

RELEASE AND WAIVER OF LIABILITY

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

REFUND AND CANCELLATION

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

LOST, STOLEN, OR DAMAGED EQUIPMENT, BOOKS, PRINTS, ETC.

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture or when in the presence of books, prints etc. belonging to other participants or the instructor(s). We recommend that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all such objects.

The post Jamel Shabazz: On the Streets appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 10, 2018

America’s Desert Dystopia

Susan Lipper’s sun-bleached pictures reimagine a stereotypically masculine landscape.

By Adam Bell

Susan Lipper, Untitled, from the book Domesticated Land, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Higher Pictures, New York

The American desert has always been contested and occupied. Full of masculine self-aggrandizement, the stories Americans tell themselves about these landscapes and their past do little to clarify matters. Despite the belief otherwise, the desert is not a clean slate that absorbs the sins of America. Atom bombs, genocidal slaughter, military exercises and secrets are all reduced to dots on a map, hidden in the expansive terrain, but their erasure is never complete. Constructed from a pointedly feminist perspective, Susan Lipper’s Domesticated Land (MACK, 2018) offers a subtle but insistent counternarrative. Lipper’s project shares an affinity with the diaries of women who traveled west in the nineteenth century, but also draws on the deep photographic history that has addressed the American desert, joining a long (and continuous) narrative of settlement and resistance in a hostile and alien landscape. What Lipper finds there is unsettling yet all too familiar, but she offers hope. That we’re not slaves to the narratives or aggressive forces surrounding us. That we can carve out a space amidst the madness and the stark light, a space we can cultivate and perhaps someday call a home.

Adam Bell: Domesticated Land is the final part of a trilogy that includes the books Grapevine (1994) and trip (1999). You’ve talked about how the three projects form a “synthetic road trip.” How did you come to see these projects as a trilogy? And what led you to the American desert?

Susan Lipper: I am taking some creative license. Although Grapevine and trip were basically consecutive, there is a thirteen-year gap before Domesticated Land starts. Some time after finishing Grapevine, I manufactured a photographic persona, and it is through her eyes that we see. Like myself, my persona is a liberal native New Yorker (but probably, as a more romantic type, doesn’t obsess over the news), looking for a reason to believe in the myth of new beginnings. She has not lost faith in America fulfilling its utopian promise—or at least in some regional or geographic part of it retaining the promise. She is also looking for something pure and viable outside of global consumerism and all-encroaching mainstream culture. This unrelenting search for freedom and transparency leads her to the West, as it has led Americans since the country’s inception. In addition, she is fascinated by the well-trodden, mostly male trope of the American road trip.

Susan Lipper, Untitled, from the book Domesticated Land, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Higher Pictures, New York

Bell: The American desert is a vast, complex landscape, often associated with Hollywood Westerns and other traditionally masculine narratives of conquest, settlement, and militarization. You shot these images primarily in the Southern California desert, east of LA and west of Las Vegas. What drew you to this particular American desert, and how do you see your work reacting to or pushing back against more dominant narratives of the U.S. desert and Western landscape?

Lipper: Deborah Bright, in her famous 1985 essay “Of Mother Nature and Marlboro Men,” threw down the gauntlet asking why “the art of landscape photography remains so singularly identified with a masculine eye,” and referring to the American landscape as “an exclusive white male preserve.” My interest was in revealing my persona’s subjective response to the California desert and in adding her voice to the canon. I believed this voice to be subversive and antipatriarchal. When researching, my only parameters were that I/my persona needed to be in California and the desert. What mattered was that California represented the end of the line both historically for emigration and also the end of the line, period. The desert too is obviously a very loaded metaphor. Sure, there are American and photographic references, but also less concrete ones that relate to the Bible and science fiction. It’s been said somewhere, I think by the theorist Dick Hebdige, that the desert continues to be a blank slate for multiple contradictory projections.

Susan Lipper, Untitled, from the book Domesticated Land, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Higher Pictures, New York

Bell: Although the landscapes appear empty at times, the spaces are full of people or human presence—abandoned foundations, piles of rusty food cans, solar panels, and, most dominantly, the U.S. military. While the U.S. military has long used the deserts of California and other western states as staging grounds for military exercises, civilians have also settled the landscape and sought to carve out a “domestic” space, to borrow a word from your title. One of the protagonists in the work appears to be a group of friends (or family) with a dog, who seem to be searching through the sparse settlements they find—looking for clues, or perhaps looking for a place to settle down. Contrasting images show large crowds moving towards a military base under the watchful guidance of men in desert fatigues, perhaps tacitly accepting the occupation, or their presence. How do you see these two impulses playing out in the work?

Lipper: One of the things I am playing with in Domesticated Land is a somewhat fantastical apocalyptic narrative, a bit like Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, where there is a story told sequentially, but embellished by transhistorical leaps both forward and back. Besides asking the viewer to construct their own tale, I am also asking them to reject seeing only the descriptive power of the medium—the eternal and knowable present.

Additionally, embedded in Domesticated Land is a subplot featuring actual people, a rock band, who interacted with my persona—a family who took her in. This bonus content is a bit like finding an Easter egg in computer software. Awareness of these individuals might only emerge to the obsessed or careful reader after the multiple readings that are allowed and encouraged by the photobook format.

In the course of events, my persona comes to understand that the desert homesteader group/mankind is living on borrowed time, and that it is only military conglomerates or governmental forces that can assemble enough technology to sustainably survive the harsh conditions that exist in the desert/free world. The men in fatigues you mention represent those as-yet-undefined factions.

Susan Lipper, Untitled, from the book Domesticated Land, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Higher Pictures, New York

Bell: Despite the high-key light, there is an underlying darkness to the work. The light is unrelenting; it obscures details, burning them out, but also forcing us to pay attention. What drew you to the light in the desert? And what, if any, metaphoric role do you see it playing in the work?

Lipper: In the novel The Stranger, by Albert Camus, the hero, or antihero, commits a random murder solely because he has become disoriented by the elements, namely the extreme bright light. His exposure to the glaring whiteness creates some kind of psychic transformation, classified as neither good nor evil. Like famed mirages, things in the desert are not what they seem. I am also reminded of the surreal sun-drenched dueling scorpion scene that opens Luis Buñuel’s L’Age d’Or, where there is no explanation offered. La Jetée by Chris Marker also alternates between light and dark worlds, but does not give preference to either one.

Susan Lipper, Untitled, from the book Domesticated Land, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Higher Pictures, New York

Bell: Your book is interspersed with several quotes by female authors—Margaret Atwood, the noted author; Annette Kolodny, an academic writing about female pioneers; and Catherine Haun, a woman from that period who wrote a diary. There are also lyrics from the rock band The Sibleys’ song “Cold Duck.” Can you talk a little about how you picked these quotes (and lyrics), their authors, and how you see them functioning in the book?

Lipper: The beginning and final passages pertain to largely forgotten female pioneers from the 1800s who kicked off my persona’s quest from the East to the West. These quotations are startlingly relevant today, especially when one considers that ours is still a broken and noncontiguous nation. As for Margaret Atwood, she popularized the term speculative fiction, tangible dystopian happenings in the near future that are not beyond imagining. The rock band’s lyrics, which one is presently able to listen to on Spotify and YouTube, frame a state of mind or vibe that embraces an inertia ubiquitous among current desert dwellers.

The texts and photographs are independent of each other and amongst themselves. Meaning is ordered in the mind of the reader. I suppose I was attempting to create a picture of ideas and emotions that were relevant in and around the time of the book’s assembling. I finished photographing in 2016, just before the U.S. election. The final edit and sequence took place during its aftermath.

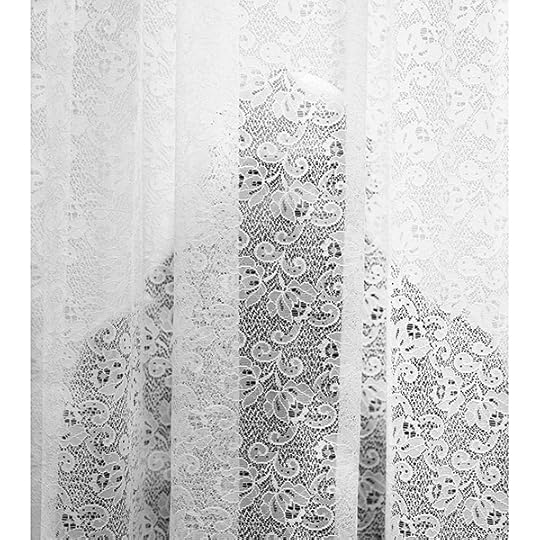

Bell: The book ends on a slightly hopeful, albeit open-ended, note. The final sequence begins with an image shot from a window, looking past a curtain, out onto a sparsely inhabited landscape. The group of people we’ve been following may have found a spot to call their own, but may still be passing through, searching. What do you see as the trajectory of the book, and is the ending really an ending?

Lipper: The tale is meant to remain open-ended and be seen as a premonition relevant to these times. Though, it is not one without hope.

Adam Bell is a photographer and writer based in New York.

Susan Lipper: Domesticated Land was published by MACK in 2018.

The post America’s Desert Dystopia appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 5, 2018

On the Front Lines of Art and Fashion

Aperture Foundation announces the five finalists for the New Vanguard Photography Prize.

Photograph by Igor Pjörrt. Courtesy of Document

This spring, Aperture Foundation, in partnership with Document Journal, Calvin Klein, and Ford Models, welcomed applicants from around the world to submit their work to the New Vanguard Photography Prize. Having received the support of thirteen esteemed judges, including Aperture editor Michael Famighetti, and over 17,000 total public votes from around the world, Document is excited to announce the five finalists. Each finalist will get the chance to shoot a Document story, with one select winner receiving the chance to photograph a special cover of the Fall/Winter 2018 edition of Document Journal. The twenty-five semifinalists will be showcased in an exhibition at Aperture Foundation in October 2018.

Photograph by Quil Lemons. Courtesy of Document

Quil Lemons

American, based in New York

A student at The New School in New York, Lemon creates an expanding vision of what it means to be African American in America.

Photograph by Jan Philipzen. Courtesy of Document

Jan Philipzen

German, based in Antwerp

For the past three years, Philipzen has been working on an autobiographical project: raw, intimate images which capture the stories of the photographer’s close friends as well as the physicality and fragility of the photographic medium.

Photograph by Lucie Khahoutian. Courtesy of Document

Lucie Khahoutian

Armernian, based in Paris

Khahoutian’s work creates encounters between western contemporary culture and traditional Armenian references. Khahoutian tends to go back and forth between collage and photography to emphasize the magical and spiritual qualities in her work.

Photograph by Igor Pjörrt. Courtesy of Document

Igor Pjörrt

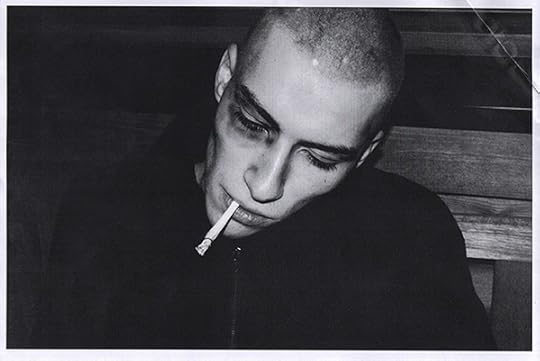

Portuguese, based in London

Pjörrt traverses the intersections of masculinity, intimacy, and temporality through his work. Pjörrt often takes inspiration from his own experiences of isolation and trauma, approaching photography as a tool of exploration as he seeks avenues of personal and collective healing.

Photograph by Ward Roberts. Courtesy of Document

Ward Roberts

Australian, based in the United States

Roberts’s images draw on themes like the effects of loneliness and isolation in the modern world, but he still maintains a fresh and engaging perspective. Roberts’s ornate style is often contradicted by life’s unscripted moments.

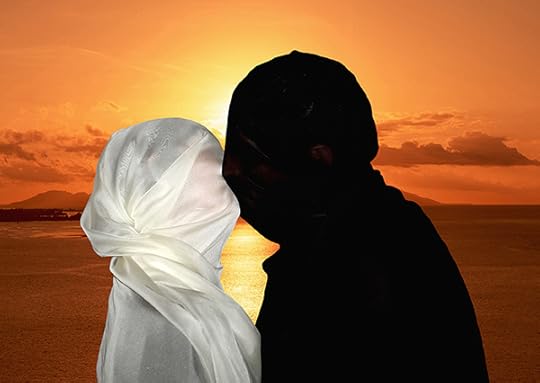

Photograph by Tahia Farhin Haque. Courtesy of Document

Special Reportage Prize: Tahia Farhin Haque

Bengali, based in Dhaka

Originally a biochemistry major, Haque switched her focus when she was awarded a full scholarship to photography school in Dhaka. Haque wants her work to shatter traditional stereotypes about women Islamic countries and bring their unique perspectives to the forefront.

The Jury

Nick Vogelson, Document

Sarah Richardson, Document

Olivier Rizzo, Stylist

Mario Sorrenti, Photographer

Doug Lloyd, Lloyd & Co.

Christopher Michael, Ford Models

Michael Famighetti, Aperture

Drew Sawyer, Brooklyn Museum

Lorna Simpson, Artist

Roxana Marcoci, The Museum of Modern Art

Candice Marks, Art Partner

Willy Vanderperre, Photographer

Peter Fitzpatrick, Swipecast

The post On the Front Lines of Art and Fashion appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 3, 2018

9 Swimming Pools

Beat the heat wave with these scenes of poolside splendor.

Slim Aarons, A poolside party at a desert house, Palm Springs, 1970

© the artist/Getty Images

Slim Aarons

A former army photographer, Slim Aarons came back from the front lines with a mantra: to photograph “attractive people doing attractive things in attractive places.” True to his word, Aarons’s scenes show tony sunbathers dotting sublime landscapes from Palm Springs to Marbella.

Nan Goldin, Simon and Jessica kissing in the pool, Avignon, 2001

© the artist and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York and Los Angeles

Nan Goldin

In the early 2000s, Nan Goldin traveled to Europe, where she photographed couples making love. Heartbeat, the resulting slideshow, features 245 images—all in her intimate, signature style.

Jodi Bieber, Orlando West Swimming Pool, Orlando West, Soweto, December 19, 2009, from the book Soweto

Courtesy the artist

Jodi Bieber

Soweto, a township of Johannesburg, is often defined by its shantytown origins and as a site of resistance to apartheid. But South African photographer Jodi Bieber adds nuance to these views with her dynamic portrayal of daily life and leisure, such as this bathing beauty caught in the chaos of a crowded pool.

Martine Franck, Pool designed by Alain Capeilleres, Town of Le Brusc, France, 1976

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Martine Franck

This iconic photograph departs from Martine Franck’s primary pursuit of humanitarian reportage. Her dexterity with form, composition, and shadow is immortalized in a moment of summer bliss.

Larry Sultan, Untitled, 1982, from the series Swimmers, 1978–82

© the artist and courtesy the Estate of Larry Sultan and Casemore Kirkeby, San Francisco

Larry Sultan

“Between 1978 and 1982 I photographed people learning to swim in several pools in San Francisco. I was interested in making pictures that were excessively physical, sensual, and painterly,” said Larry Sultan. Unlike the composed work Sultan is best known for, these snapshots invite the viewer to jump on in.

René Burri, Stable, horse pool and house planned by Luis Barragan and Andres Casillas, Mexico City, 1976

© the artist/Magnum Photos

René Burri

Throughout the 1960s and ’70s, René Burri visited his friend and Pritzker prize winner Luis Barragán several times, often photographing the architect’s buildings and gardens, including his home. The resulting photographs are an ode to Barragán’s keen sense of shape, depth, color, and beauty.

Martin Parr, The Artificial Beach inside the Ocean Dome, Miyazaki, Japan, 1996, from the series Small World, 1996

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Martin Parr

Martin Parr, famous for his satirical photographs of tourists, fully embraces the cliché of the overcrowded beachfront in Ocean Dome. The indoor pool comically masquerades as a natural body of water, as the horizon line smashes up against the far wall, painted to look like the sky.

Deanna Templeton, Ed, 2008

© the artist and courtesy Gallery Fifty One

Deanna Templeton

For eight summers, Deanna Templeton photographed her friends skinny-dipping in her pool, beginning with this image of her husband, Ed. The photograph is a graceful testament to summer and the nude form.

Hannah Starkey, Untitled, September 2006

Courtesy of the artist; Maureen Paley, London; and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York and Los

Angeles

Hannah Starkey

Hannah Starkey has been making singular, large-scale photographs of women throughout her career. In this scene, at once peaceful and full of anticipation, the central figure is an icon of beauty and desire.

The post 9 Swimming Pools appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 27, 2018

Pushing the Boundaries

A preview of the artist Loredana Nemes’s first major museum exhibition.

Loredana Nemes, Rasim, Neukölln, 2009, from the series beyond © the artist

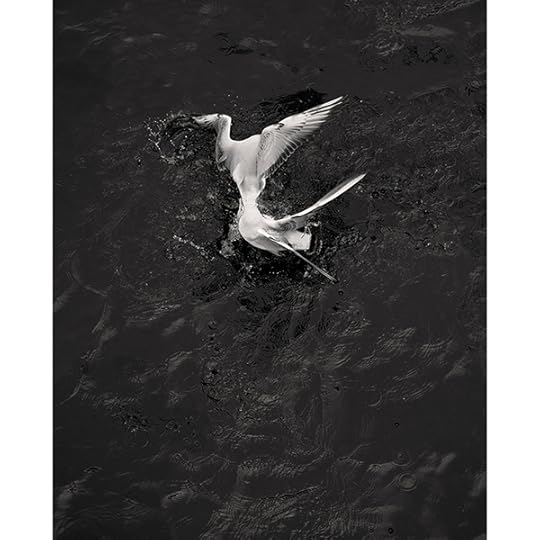

Loredana Nemes, Gier #07, 2014–17 © the artist

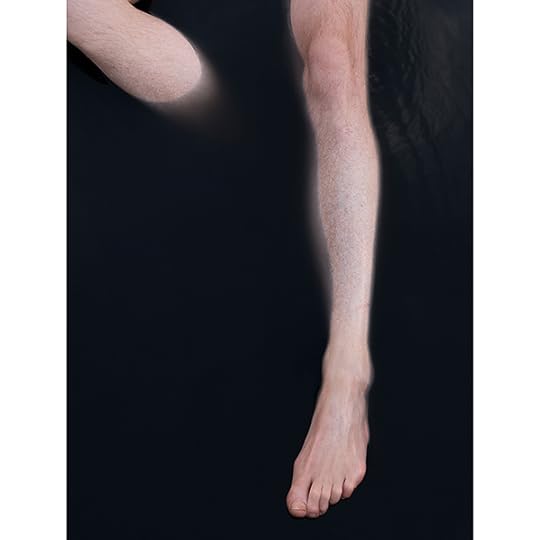

Loredana Nemes, Beine, from the series Ocna. Eine Annäherung, 2017 © the artist

Loredana Nemes, Café Esto, Neukölln, 2008, from the series beyond, 2008-10 © the artist

Loredana Nemes, Fatih, Kreuzberg, 2009, from the series beyond, 2008-10 © the artist

In her first major solo museum show, the Romanian-born artist Loredana Nemes pushes the boundaries of portrait photography, frequently landing on unusual approaches. In the series beyond (2008–10), which explores the male world of Turkish and Arab cafés, Nemes experiments with blur in portraits and enigmatic depictions of cloudy facades. She draws on cinematic effects in the group portraits of teenagers that make up her series Blossom Time (2012). Recently, Nemes has utilized abstraction as a means of “visualizing basic feelings,” says curator Ulrich Domröse. The exhibition will include a new politically relevant series, 23197 (2017), in which Nemes employs abstraction to explore ideas of fear, and Greed (2014–17), which engages with themes of desire in its black-and-white images of tangled seagulls.

Loredana Nemes: Greed, Fear, Love: Photographs, 2008–2017 is on view at the Berlinische Galerie, Berlin, from June 22 to October 15, 2018.

The post Pushing the Boundaries appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 25, 2018

The Land and the Landscape

A conversation with David Goldblatt, who throughout his long career used the camera to reflect the social realities of South Africa.

By Jonathan Cane

David Goldblatt, Mrs. Miriam Diale in her bedroom, 5357 Orlando East, Soweto, October 1972, from the series Soweto

Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town

“Events in themselves are not so much interesting to me as the conditions that led to the events,” David Goldblatt says to interviewer Jonathan Cane. While other photographers have focused on the turmoil of South Africa’s colonial and apartheid years, Goldblatt, who is now eighty-four, tends to train his lens on quieter subjects emblematic of the prevailing social order. He will soon be republishing his series In Boksburg (1979–80), in which he looked at daily life in a white middle-class community in the years of apartheid. Among his many series are Some Afrikaners Photographed (1961–68); On the Mines (1973), documenting South Africa’s mining industry; and The Transported of KwaNdebele (1989), addressing the plight of black workers forced to travel great distances for employment. More recently, for Ex-Offenders (2010–present), he photographs individuals on parole at the scene of their crimes.

The conversation that follows took place last May at Goldblatt’s home in an old Johannesburg suburb; like much of Goldblatt’s work, it was framed by events in the news—the controversy over a statue of Cecil John Rhodes, the mining magnate and imperialist symbol, at the University of Cape Town, for instance. In protest of the university’s faculty, overwhelmingly dominated by white men, an activist threw human feces on the Rhodes statue in March 2015; the statue was subsequently removed, and has since become a symbol for “decolonizing” the university. This concern with monuments has been central to Goldblatt’s work for many years. Also happening around the time of Goldblatt and Cane’s talks were xenophobic conflagrations across South Africa—deeply unsettling violence involving exiles and refugees from other African countries. The photojournalism documenting these recent conflicts throws into relief the incisive work Goldblatt made during the most violent times in South Africa, and which he continues to make still.

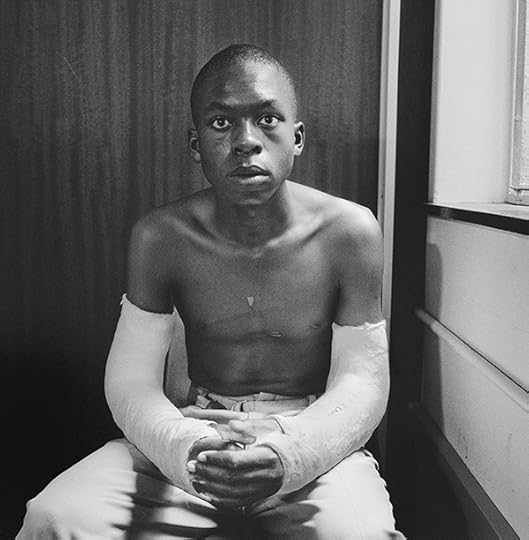

David Goldblatt, Fifteen-year-old Lawrence Matjee after his assault and detention by the Security Police, Khotso House, de Villiers Street, October 25, 1985, from the series Joburg

Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town

Jonathan Cane: You’ve photographed many walls, fences, boundaries. I think of your 1986 photograph Die Heldeakker, The Heroes’ Acre: cemetery for White members of the security forces killed in “The Total Onslaught,” Ventersdorp, Transvaal, or any of the precast fences in your iconic 1982 book In Boksburg.

David Goldblatt: They occur in my work because they are part of our life, absolutely. But I haven’t particularly sought them out. I am very conscious when I drive around the country of the number of game fences we have, and what the effect of those are, and I have photographed those. A lot of farmers have switched to farming with game, because they save on labor and they are able then to fence off their land in such a way that they make it virtually impossible for people to walk over it, and to use their land as a means of getting from point A to point B, never mind doing anything else on the land. So there are these very high fences dotted around the country now, many of them electrified, and it’s not clear to me whether the electrification is to keep the game from moving too close to the fence or to keep people out.

Cane: You live in a gated community, which is typical in South Africa. How do you feel about that?

Goldblatt: I feel very negative about it. We have a boom at the only motorcar entrance in the suburb, and a guard there, and by municipal regulation he’s not allowed to stop anybody, so it’s meaningless, really. And he might question a person coming through but he’s not really supposed to. We have an electrified fence that we put up after my wife and I were held up inside our house by men with pistols. It protects us, but I don’t kid myself. We’re not in Fort Knox. It would be very easy to break in again. I just think that I’m not a very tempting take, you know.

David Goldblatt, A plot-holder, his wife and their eldest son at lunch, Wheatlands, Randfontein, September 1962, from the series Some Afrikaners Photographed

Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town

Cane: The vibracrete fence of prefabricated, modular concrete slats and pillars, for me as a Joburger, is emblematic. My father always said we must turn the fence outward—have the good side out and the crappy one facing in. That was our civic duty to our neighbors.

Goldblatt: I’ve never thought about that subtle variation on the use of the vibracrete fence. I think they are very significant as part of our makeup, really. It’s a cheap way of fencing your property, and obviously very popular. If I had to refence our property, I might be tempted to use it, but I would most certainly reject it. And I have photographed some in the course of my work.

Cane: You’re republishing In Boksburg. Why republish this book three decades later?

Goldblatt: Well, there’s a man in Germany by the name of Gerhard Steidl, who is probably the prince or the king of photographic books, who is totally obsessed by quality. And I am in the very fortunate position of having become a sort of favored photographer of Gerhard. He told me at lunch a few years ago, “I want twenty books from you in the next twenty years.” So I’ve got an extensive program to fulfill [laughs]. Of course, it’s not possible to do it; it would be quite impossible to do. But he more or less accepts whatever I suggest we publish.

David Goldblatt, Die Heldeakker, The Heroes’ Acre: cemetery for White members of the security forces killed in “The Total Onslaught,” Ventersdorp, Transvaal, November 1, 1986, from the series Structures

Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town

Cane: You wrote in your original introduction to that book that in Boksburg you observed the “wholly uneventful flow of commonplace, orderly life.” This included weddings, garden maintenance, and sports in a whites-only town. Observers have noted that you are interested in the commonplace rather than the dramatic, that your violence is the violence of a vibracrete fence rather than “necklacing” [the apartheidera style of execution where aggressors forced gasoline-filled tires around their victims’ torsos and then set them alight].

Goldblatt: Yes. This is perfectly true. First of all, I am a physical coward. I shun violence. And I wouldn’t know how to handle it if I was a photographer in a violent scene such as James Oatway photographed last week for the Sunday Times [of the so-called xenophobic violence]. I think he is very brave. But then I’ve long since realized—it took me a few years to realize—that events in themselves are not so interesting to me as the conditions that led to the events. These conditions are often quite commonplace, and yet full of what is imminent. Immanent and imminent.

In Boksburg was partly about the banality of ordinary, law-abiding, and also, on the whole, moral people, who were knowingly living in a system that was quite immoral and, indeed, insane. We were all complicit in it. And that complicity is, I suppose, what In Boksburg is about.

Cane: Do you think by republishing it you’re saying something about a kind of continued complicity?

Goldblatt: I wouldn’t. First of all, I claim nothing for my book.

Cane: That seems like a spurious claim to me.

Goldblatt: No, I don’t think it is. I would claim that the work is done with some insight, and that possibly these insights are relevant, and possibly these insights will percolate and, by osmosis, become part of the consciousness. But I’ve never, ever thought that what I do will actually directly influence someone to do or not to do something.

David Goldblatt, Girl with purse, Joubert Park, Johannesburg, 1975, from the series Particulars

Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town

Cane: Is that why you’ve always claimed you’re not an activist?

Goldblatt: Because I am not an activist. An activist takes an active part in propagating their views. My colleagues in photography in the 1980s were activists, undeniably. They acknowledged it. They claimed that this was their role. And I respect them greatly for that.

Cane: Some people disrespected you because they felt you weren’t enough of an activist.

Goldblatt: Yes. That’s par for the course. I have to accept that. But I wasn’t prepared to compromise what I regarded as my particular needs. For a time, I think some of the people who later became very good friends of mine, and who are still my best friends, were rather suspicious . . .

Cane: . . . because the world was burning, and you were taking photographs of people mowing their lawns. Did that seem to you at the time to be a very interesting, strange approach?

Goldblatt: I thought it not only strange, but very uncomfortable. I mean, just now with Alexandra burning and Soweto burning, and parts of KwaZulu-Natal, I have felt what I often felt during those years, that what I was doing was probably irrelevant, but I had to accept that this was the way I am. I am not James Oatway or Paul Weinberg or John Liebenberg, who went right into the depths. I am what I am.

Cane: You talk to the people you photograph, in the sense that you don’t sneak a photograph of them.

Goldblatt: I don’t sneak a photograph of them, but I often don’t talk.

David Goldblatt, Paul Tuge where he hid after shooting a policeman in 2001, February 18, 2010, from the series Ex-Offenders

Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town

Cane: But do you always ask permission?

Goldblatt: Oh, yes, invariably I ask. But in general, I try not to talk. The reason being that I want the subject to be very aware of the situation, and conscious that he or she is being looked at. I set up the camera, and then I don’t look through the camera, because I want the subject and me to be in eyeball-to-eyeball contact. It’s sometimes quite difficult, because you’re dealing with a powerful person. You are really trying to assert your mastery of the situation. And you have to be in control of the situation. That’s quite tricky. I want the subject to feel tension. I don’t want the subject to feel particularly comfortable with me. I used to do a lot of portraiture of leading people: Mandela. [Joaquim] Chissano. [Robert] Mugabe. [Kenneth] Kaunda. And so on. Not [Samora] Machel. I never photographed Machel. I would insist—often at the cost of serious differences with security, police officers, and the like—on putting the subject into a straight-back chair, something like that, rather than an armchair, or what I call a goma goma chair, which you sink into.

We had an interview with Mandela just before he became president. It was in the house in Houghton where he was living then. Anyway, he’d been up since four o’clock in the morning doing exercises and whatever else he did. He came down at five for that appointment, and I had insisted—because the house was full of goma goma chairs—that I wanted the straight-back kitchen chair. The press officer, Carl Niehaus, who was later in disgrace [for his financial improprieties], said, “You can’t put Mr. Mandela onto a kitchen chair.” I said, “I insist.” I said, “I’ve come to photograph Mr. Mandela, not the furniture: I want a kitchen chair, and I insist.” Eventually, when he saw the photograph, he conceded that it was the right thing to do. You’ve got to take control of the situation. Otherwise, it’s a runaway.

Cane: Language is fundamental to what you do.

Goldblatt: Well, the kind of photography that I am interested in is much closer to writing than to painting. Because making a photograph is rather like writing a paragraph or a short piece, and putting together a whole string of photographs is like producing a piece of writing in many ways. There is the possibility of making coherent statements in an interesting, subtle, complex way.

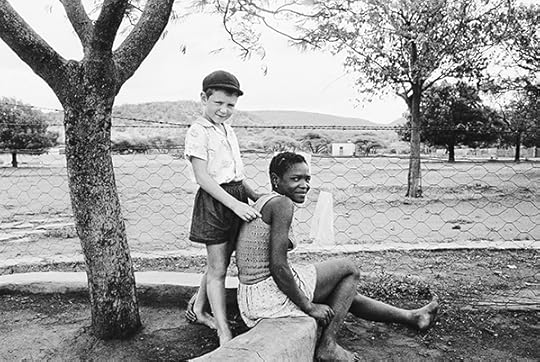

David Goldblatt, A farmer’s son with his nursemaid, Heimweeberg, Nietverdiend, Western Transvaal, 1964, from the series Some Afrikaners Photographed

Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town

Cane: You are known for your long captions.

Goldblatt: I usually offer them in a form where they can be split. I learned from Life, Look, and Picture Post, which were expert at conveying information on three, four levels really. There were the photographs, which were the simple focus of what the magazines were doing, and then there were three layers of wordy information. There was the main caption, which was short, pithy, and gave you some basic text. There was a subsidiary caption, usually written in a lighter face or a smaller point size. Then there was a text. By means of these three layers of information, or verbal information, or written information, they conveyed a great deal in a really digestible way.

Cane: You have collaborated with some of the most respected South African writers: Nobel Prize–winner Nadine Gordimer wrote an essay for your first book, On the Mines, from 1973, and recently you published TJ & Double Negative with Ivan Vladislavic. Tell me about your relationship with Ivan.

Goldblatt: I admire him greatly, first of all, his ability to write books. But perhaps more relevant and more important is his ability to seize upon often insignificant details of our life here that are key to an extrapolation of our life. So in one of his books, there’s a man who is the proofreader for the Johannesburg telephone directory. I mean, you’ve got to have an extraordinary imagination to imagine that. In the book that came out of what we did together, he exhibits a similar kind of imagination. Part of the story involved [the collection of misaddressed] “dead” letters of a Portuguese man who used to be a doctor, and one of the highly qualified men in Mozambique, who comes here and can’t get work but becomes a letter sorter.

Ivan has this ability to, I don’t know, to somehow extrapolate our life in terms that are often amusing and yet tragic, and always, always relevant to our life.

David Goldblatt, Saturday afternoon in Sunward Park, 1979, from the series In Boksburg

Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town

Cane: Which writers do you still hope to work with?

Goldblatt: I would say that there are two people with whom I would love to collaborate. Marlene van Niekerk [Afrikaans novelist, poet, and professor]. I can’t imagine what we might collaborate on, but I’d dearly love to. And Njabulo S. Ndebele [author and former vice chancellor of the University of Cape Town].

Marlene and I have had a couple of public discussions. That was when I realized what a formidable person she is, and her grasp of things. She knew my work intimately, and she asked questions that penetrated right to the heart of things and yet without harassing me. Subsequent to that, I asked whether I could meet her. At that time, as an extension of what I had done in Particulars [made in 1975 and published as a series in 2003], I was attempting to do some nudes, and I had done one or two, and then formed the idea that I would like to do portraits of people in the nude. So we made a date to meet outside Cape Town for lunch, at which I told her my undisguised and unlimited admiration for her, and I said to her, “I would like to do a portrait of you in the nude.” She laughed. She said, “Absolutely out of the question.” She said, “First of all, I am in the academic world here and that just would be unacceptable, but secondly, I am a very shy person, and I just wouldn’t do it.”

Cane: Do you have an archive of projects that could not or should not be done?

Goldblatt: Over the years, there have been things that I have wanted to do, but, for one reason or another, couldn’t. Mainly these have been things that were just very difficult to do. For example, in the 1980s I wanted to photograph subjects who had been detained and tortured, and I photographed some of them in the course of providing visual evidence for a court case. A number of photographers did this. Lawyers would want pictures of people who’d been shamboked [whipped] in prison; they’d want pictures showing the wounds. I did a number of those. But I wanted more than that. I wanted to do portraits of people who had been tortured. I did one or two, and it was terribly difficult because people were afraid. There is one picture that has been published quite often of a young man with his arms in plaster. I did two photographs of him, one front and back, and I photographed one of his colleagues. But I gave it up. It was just too difficult to get people who were prepared to accede to this.

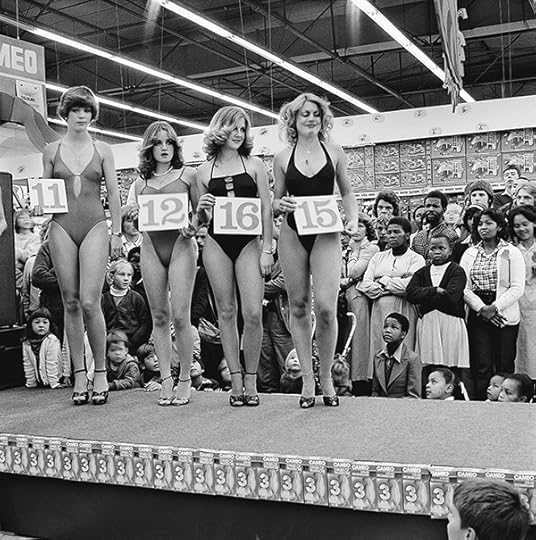

David Goldblatt, Saturday morning at the Hypermarket: Semi-final of the Miss Lovely Legs Competition, June 28, 1980, from the series In Boksburg

Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town

Cane: You mentioned that you are digging back into your archive. What does it feel like to look back—and to still have twenty books planned?

Goldblatt: Well, I wish I had twenty books still planned. Every now and again I catch myself and say, “Am I really this old?” I don’t feel very old. But at the same time, I am aware that my body is changing, and my ability to handle complexities. Age has affected me. I think it would be true to say that when I was younger, the sex drive was a very potent force in what I did. That is less the case now, partly because of physical changes in the body. Do you know the work of Borges, the Argentine writer? He said something marvelous once, and I can never quite remember it, but basically he said that in your youth—this referred to a writer—if the stars are right, and everything is in place, then in his or her maturity, his work might contain a subtle, hidden complexity.

Cane: You’ve always insisted on a strict boundary between your “professional” work done for clients—including the powerful South African mining houses—and what you call your “personal” work. After the 2012 Marikana massacre, when thirty-four striking miners were shot dead by the South African police, did you have occasion to reflect on that dividing line in your work?

Goldblatt: Well, I don’t think I fully grasped the depth and extent of the exploitation of migrant men working in this country. That became clear to me during this incident at Marikana. It was clear that the migrant workers were in the position of sellers of their labor, in a very weak position, whereas the mining houses were immensely powerful, and there’s no question that they exploited that difference in power, if you like, over many years. They exploited it. There is currently a class-action suit against the large mining houses for the damage done by silicosis, which is a chronic lung disease caused by the silica dust miners breathe in while working. I photographed some aspects of this. I came along at the end of this long, sorry tale. They had stopped mining asbestos when I came into it. I have to acknowledge that I did things for the mining houses that, in the light of what I now understand better, I should not have done, and should have refused those assignments, those commissions. Or I should have handled them differently.

In my own personal work, in my book On the Mines, I have touched on these things in quite brutal photographs. But I didn’t sufficiently illustrate that much. And we’re not out of that yet. The relationships still stand. Just in the last week or two, there was an announcement of the take-home pay of the executives. It was appalling. Not one of them came up and met the strikers and sat down and talked to them. Not one.

David Goldblatt, Team leader and mine captain on a pedal car, Rustenburg Platinum Mine, Rustenburg, 1971, from the series On the Mines

Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town

Cane: What has age taught you?

Goldblatt: I will say that I’ve learned to be a good craftsman. That goes without saying. I don’t think you can seriously engage in photography if you’re not a craftsperson. You have to be reasonably competent at handling situations, and the camera obviously. But I have to say that as I’ve entered my ancient years, my craftsmanship has deteriorated. I forget too much. I take too much for granted. I had a very good friend who was a great architectural photographer, Ezra Stoller, an American man, who was so famous for his architectural photography that great architects would want to “Stollerize” their buildings. And he said to me once—and he was then about the age that I am now—he said that he had lost the ability, the critical faculty to make judgments of prints. Ja, I’m sad to confess that I think this is happening to me. I’ve been printing now for the last few months, and I’ve reestablished my connection with my work that I had lost for a time.

Cane: I always wanted to be old. Does that sound silly to you?

Goldblatt: No, no, not at all. I had a brother, Nick, ten years older than me, and I loved the lines in his face. I had a smooth face. I used to envy him to no end. In many ways, I wish I were younger. But I think, on the whole, I accept growing old. What I am very conscious of is that I probably don’t have many years left of active work. I have to be able to climb onto the roof of my camper. I have to be able to drive fourteen hundred kilometers to Cape Town. I must be able to do these things. And my ability to do that is probably limited within the years left. When I was forty, fifty, sixty, and seventy, it seemed like there was an unbroken span in front of me. Now that I am eighty-four, it’s a bit unrealistic to hope that it’s still an unlimited span. Gerhard Steidl’s twenty books in twenty years is somewhat unrealistic maybe.

David Goldblatt, Drum majorette, Cup final, Orlando Stadium, Soweto, 1972, from the series Soweto

Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town

Cane: Did you know that you are very much in fashion right now? If you visit any fashionable person in South Africa they will have a David Goldblatt in their lounge.

Goldblatt: I didn’t know that. My sales figures don’t bear that out.

Cane: They even have a particular way they’re framed and they’ll be hanging next to, like, a Zander Blom or maybe an early William Kentridge print. How do you feel if I tell you that you are at the height of fashion right now?

Goldblatt: I feel very vulnerable, because that’s bound to change. Fashion is essentially a passing phenomenon, and ja, I am absolutely not at peace with it.

Cane: I want to talk about the South African veld. I was driving across the country the last two days and was struck by how exquisite, how devastating it is in some ways. J.M. Coetzee wrote in White Writing that whites lacked a vocabulary for the light and the color of the place. I think some people would say—you said it yourself, I think, once—that there was a time when you stopped running away from the light of this place, and tried to find, or did find, a language for that here.

Goldblatt: I think that’s true. Just now, in the Karoo, where I went after photographing the student dethroning [of Cecil John Rhodes’s statue at the University of Cape Town], I went up to an area near Langford that I’ve often looked at with the idea of photographing it. I once went there about four years ago, five years maybe, and got permission from the farmer to go over his land. I was in my camper, and I drove in there, and I did a photograph that I’ve never really liked. But I knew that there was something there that I wanted to explore. Just a few weeks ago, I went back there, and for two days, when I had a weekend, I went back to that farm and walked over it, found a koppie [a small hill], drove along the Cape Town–Johannesburg railway and did some photographs, which I think are the beginning perhaps of something. For me there is no question that the land itself, that “land” as opposed to “the landscape,” is something that I would like to explore. I don’t quite know how. But when we speak of “the landscape,” that already is a value judgment. It considers that you have looked at the land, and formed a picture around it that makes it into a scape.

David Goldblatt, The monument at left celebrates the fifth anniversary of the Republic of South Africa. The one at right is to JG Strijdom, militant protagonist of White supremacy and of an Afrikaner republic, who died in 1958. At rear is the headquarters building of Volkskas (“The People’s Bank”) founded in 1934 to mobilize Afrikaner capital and to break the monopoly of the “English” banks. Pretoria, April 25, 1982, from the series Structures

Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town

Cane: Making a photo of the land without making a landscape.

Goldblatt: A photographer who I really admire, Guy Tillim, has done that in São Paulo, in Tahiti, and he has done it in Johannesburg. The photographs that he did in Johannesburg are amazing. They appear to be fuck all. I think they are great. It’s something that, ja, I’ve been conscious of for a long time.

How do you resist this need to find order? And yet, how do you do that so the photographs are not just chaotic?

Jonathan Cane is a writer and researcher who lives between São Paulo and Cape Town.

This interview was originally published in Aperture Issue 220, “The Interview Issue” and republished in Aperture Conversations: 1985 to the Present.

The post The Land and the Landscape appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 21, 2018

Gardens of Earthly Delight

Wander through cherry trees and orange shrubs with photographers such as Joel Meyerowitz, Collier Schorr, and Luigi Ghirri.

By Sarah Anne McNear

Joel Meyerowitz, Vivian, Bronx Botanical Gardens, New York City, 1966

© the artist and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Though it is impossible to state unequivocally that the biblical Garden of Eden is a referent for all photographers working in the garden, the idea of Eden, or rather its cultural hallmarks—innocence, tranquility, simplicity, abundance, florescence, and, above all, beauty—are found in many photographs made in the garden, such as this one. Here, Joel Meyerowitz photographs a young woman on the verge of adulthood posed against a profusion of azalea blossoms that seem to spread their transformative and seductive color across her chest in a magical embrace.

Sam Abell, Picnic Table, with Hail Stones, Colorado Springs, CO, 1980

© the artist/National Geographic Creative

While not a gardener, by his own admission, Sam Abell is among the ranks of people who look to gardens as places for inspiration, recreation, and pleasure: “I’m not a gardener or even a garden photographer. I’m a traveler who visits gardens for solace and visual inspiration. That means I seek from gardens what I seek from life itself—visually layered scenes that hold the possibility for meaningful photographic moments.” In this picture, Abell captures a transformative act of nature—a hailstorm in high summer—as a moment of enchanted incongruity.

Lori Nix, Wasps, 2002

Courtesy the artist; ClampArt Gallery, New York; and George Eastman Museum

Photographed from the perspective of a child, Lori Nix’s Wasps appears to be a picture of insects buzzing above the handlebars of an abandoned bike in an overgrown garden. In fact, the picture is a constructed image, made by photographing a small studio diorama created by Nix and her collaborator, Kathleen Gerber. Even so, the picture functions as a very effective aide-mémoire, recalling dreamy summer evenings when real magic seemed possible.

Luigi Ghirri, Versailles, 1985

© the Estate of Luigi Ghirri and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York and Los Angeles

The modern landscape of Europe and its mooring in history were both blessing and burden to photographer Luigi Ghirri. At Versailles, Ghirri grappled with how to represent a historical landmark and its expansive garden as they are experienced by tourists in the present day. In this picture, the visitors, tiny figures in the landscape, serve as a gauge of both the scale and the marvel of the place.

Martin Parr, Loders Street Fair, England, 1999

© the artist and courtesy Magnum Photos

In Martin Parr’s photograph of Loders Street Fair, the flowers, not the humans, are the focus. The unusual composition, which crops out the women’s faces and any other signifiers of place, turns a quotidian sight into a surreal fantasy. Parr explains, “I placed the flowers into some form of social context by making the backdrop as important as the flower in the foreground. I wanted to turn the image of the flower, so often regarded just as a beautiful object, into a social landscape.”

John Pfahl, Threadleaf Japanese Maple Tree, Hershey Gardens, Pennsylvania, October 1999, from the series Extreme Horticulture

© the artist and courtesy George Eastman Museum

John Pfahl was looking for “the unusual, the bizarre, the abundant, and the exuberant” when he created the series that he calls Extreme Horticulture. Pfahl worked with a 4-by-5 field camera and a wide-angle lens to achieve both expansive and highly detailed images, explaining, “Perceptually, when one walks through a garden, one looks at specific plants sequentially while everything else becomes a blur. However, having everything from foreground to infinity in focus creates a surreal dream-like image where everything is equally seductive and inspectable in minute detail.”

Sheron Rupp, Trudy in Annie’s Sunflower Maze, Amherst, MA, 2000

© the artist

Sheron Rupp has lived in the foothills of the Berkshires in western Massachusetts for over forty years, where she made this photograph of an elderly woman strolling through a sunflower maze. Dressed as if for church, the woman, while identified as Trudy, is a mysterious presence on an equally mysterious quest.

Virginia Beahan and Laura McPhee, White Lilacs, Emigrant Gulch, Montana, 2001

© the artist

“The work insists on restarting a complex conversation about the ways our lives are intertwined with the spaces and substances of the earth, a conversation that seems to have its origins behind the camera, with two visions and voices rather than one shaping each image,” writes Rebecca Solnit on Virginia Beahan and Laura McPhee’s series No Ordinary Land. Here, the photographers capture a mundane garden gate made briefly magical by its lilac mantel.

Jacqueline Hassink, Haradani-en 1, Northwest Kyoto, 2010, from the series View, Kyoto

© the artist

Jacqueline Hassink photographed Zen Buddhist gardens in Japan for ten years for her series View, Kyoto. Haradani-en 1, Northwest Kyoto (2010) represents one of the most famous gardens in Japan at the peak of sakura matsuri, or the cherry blossom festival. Traditionally, visitors at this time will picnic under the blossoms, a centuries-old tradition known as hanami. Hassink, having taken her camera off the prescribed path, eschews a more cultivated image of the cherry blossoms in favor of celebrating their wild embrace and florescent abundance.

Collier Schorr, Lily Pads 3, 2006, from the series Blumen

© the artist and courtesy 303 Gallery, New York

For her series Blumen, Collier Schorr pushed the notion of flower arranging out into the field—quite literally—where she would playfully construct still lifes with flowers, string, and sticks, making a game of creating her own ephemeral garden. Schorr admits to stealing the flowers that she used from other people’s gardens, in order to create this small temporary tableau in which, according to Schorr, “the flowers begin to wilt, changing shape and color. And inevitably, the wind blows them down.”

Abelardo Morell, Tent Camera Image: View of Monet’s Gardens with Wheelbarrow, Giverny, France, 2015

© the artist and Courtesy Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York and Zürich

In the series After Monet, Abelardo Morell borrows from an existing garden, Monet’s garden at Giverny, to make something entirely new. Working in a tent that he transforms into a camera obscura, Morell rephotographs the image of Monet’s brightly patterned garden as it is projected onto the gravel of the garden path. The texture of the gravel dissolves the otherwise straightforward image into something decidedly more impressionistic and paradisiacal.

These photographs are included in The Photographer in the Garden by Jamie M. Allen and Sarah Anne McNear.

The post Gardens of Earthly Delight appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 19, 2018

At Least They’ll See the Black

In two recent films, Kahlil Joseph and Arthur Jafa consider the poetics of African American life.

By Antwaun Sargent

Kahlil Joseph, Fly Paper, 2017. HD monochrome digital video and 35mm film with Funktion-One sonic universe. Installation at the New Museum, New York. Photograph by Maris Hutchinson/EPW Studio

Courtesy the artist and the New Museum

In 1953, the renowned Harlem photographer Roy DeCarava snapped David, a black-and-white portrait of a young black boy from the neighborhood: Hair nappy, his hands are folded behind his back as he leans against a lamppost. A single button holds his shirt closed, and yet the frown he wears allows him to peer, fully represented, directly into the camera’s eye. “He don’t never smile,” observed the Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes when the image appeared in The Sweet Flypaper of Life, a 1955 admixture of 140 of DeCarava’s quotidian images—of black men, women, and children going about their days and celebrated jazz luminaries playing music—paired with Hughes’s narrative. It’s DeCarava’s impressionistic image of black interiority that sits at the center of filmmaker and artist Kahlil Joseph’s film Fly Paper (2017), a monumental, twenty-three-minute ode to black Harlem, past and present.

In Fly Paper’s rapidly moving sequences, you can see DeCarava’s influence in the light and shadow Joseph builds into his portrayal of Harlem as a place of black cultural triumph and loss. Presented last year in a pitch-black installation in the exhibition Kahlil Joseph: Shadow Play (2017), at the New Museum, New York, Fly Paper contains a nonlinear narrative that expands upon the director’s use of the postwar black photographic image to, as DeCarava did, present Harlem as both a real mecca of black America and a fantastic and psychic region of the black imagination. In this way, Fly Paper recalls not only DeCarava’s pictures of black life, but also those of image makers who were part of the Kamoinge Workshop, a group DeCarava led in the early 1960s, including Ming Smith, Louis Draper, Anthony Barboza, and Ray Francis, and other documentarians of black life, such as Gordon Parks, Pittsburgh’s Charles “Teenie” Harris, Dawoud Bey, and Andre D. Wagner. These black artists’ photographs poetically employ light, shadow, and darkness to portray the ordinary and the sublime. Images like DeCarava’s portrait Elvin Jones (1961), of the jazz musician, reveal the varied textures of blackness, and push the boundaries of what can be seen and imagined in the black spaces and faces of a photograph. They are part of a contemporary canon of black images that provide what DeCarava once described as “the kind of penetrating insight and understanding of Negroes which …only a Negro photographer can interpret.”

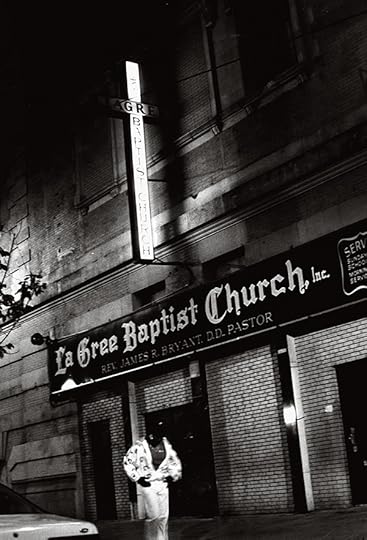

Ming Smith, Lagree Baptist Church, Harlem, New York, ca. 1985

© the artist and courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery, New York

“Black people are light-years more advanced than the ideas and images that circulate would have you believe,” Joseph said in 2013, in an interview with Nowness. “The spaces we control and exist are my zero for filming.” It’s a sentiment running throughout his depictions that blends the essence of what DeCarava and other photographers see in black skin and the absorbing fantasy at the heart of the hip-hop music video. Joseph remixes and distorts both media to produce black cinema rooted in the structural photographic. It is like nothing we have ever seen before, because often photography and film center whiteness even in depictions of blackness. As one of the directors of Beyoncé Knowles’s visual album Lemonade (2016), the artist behind Flying Lotus’s Until the Quiet Comes (2012), and the creator of Alice Smith: Black Mary (2017), Joseph uses film as a container to show the multiplicity of blackness by creating small black worlds. Time is suspended, space is distorted, light on black skin is a metaphor, and black music, cut into sounds of salvation, carries the narrative. It’s a cinematic experience that displays on-screen something that mirrors real black life.

This approach is seen clearly in Joseph’s Wildcat (2013), a black-and-white film that makes visible the erasure of the black American cowboy, which largely occurred through Westerns, a genre of film that whitewashed the American cowboy story. Wildcat takes us to Grayson, Oklahoma, during its annual August rodeo, an event that brings African American cowboys and cowgirls from across the Midwest to this small town. In one moment, Joseph’s camera hovers on a young girl wearing a white gown, representing the spirit of Aunt Janet, her late elder who started the rodeo; her eyes are small and searching. These few seconds of film, which appear to upset an entire genre that would have us believe she doesn’t exist, also represent what the gender and race theorist Tina Campt calls a “still moving image.” Wildcat is filled with the stillness one would find in a DeCarava image. There’s no dialogue, a decision that seems to reinforce the idea that Joseph wants us to watch blackness unfold on film in ways we have rarely observed. Guiding us is the melodic score by Flying Lotus, a frequent collaborator of the artist, as we watch contemporary black American cowboys, bull riders, and barrel racers create majestic new images of blackness.

Ray Francis, Harlem, New York, late 1960s, from the book Timeless: Photographs by Kamoinge

Courtesy the artist and Schiffer Publishing

Fly Paper is also filled with scene after scene of black images, retracing bits and pieces of the history of America as it played out in Harlem and the contours of history that placed black people in starring roles. The film opens with the self-determination of civil rights leader Malcolm X as he is delivering a speech on a Harlem street corner. His seriousness brings to mind DeCarava’s famous picture of stony-faced determination, Mississippi Freedom Marcher, Washington, D.C., 1963, and also Parks’s black-and-white portrait Malcolm X Gives Speech at Rally, Harlem, New York (1963). Soon the screen is flooded with mercurial, strange, and ghostly moving images that tease out the complex emotions embedded in black space: the surrealism of Smith’s Sun Ra space II (1978); singer Lauryn Hill jamming; a black mother and child in repose; a dreamlike rendering of the late painter Barkley L. Hendricks’s Lawdy Mama (1969) seen at the Studio Museum in Harlem; black fictive characters, captured in poses that evoke DeCarava’s Dancers (1956), in a darkly lit room flexing in slow motion. At one moment, the legendary performer Ben Vereen lies in a bathtub, fully clothed. These short sequences collide with the bombastic and disorienting sounds of drums, Harlem’s trains, the hustle of 125th Street, and melodies Joseph skillfully turns inside out. Joseph’s personal home videos fade in and out too. We meet Joseph’s father, Keven Davis, gossiping on the street with hip-hop pioneer Fab 5 Freddy, and after surgery at home in his uptown New York apartment before his death, at the age of fifty-four, in 2012. Joseph’s mixing of his family videos with newer original footage is reminiscent of the artist’s m.A.A.d (2014), a fourteen-minute film he made for Kendrick Lamar that blends the rapper’s personal home videos with fresh scenes of his native Compton, California.

“I wanted people to feel like they saw a Harlem that they can’t see,” Joseph recently told the New York Times. He achieves this by showing what another of Joseph’s influences, the artist and filmmaker Arthur Jafa, calls “the power, beauty, and alienation” of black Harlem. Jafa believes Joseph achieves his humane representation of black sociality because “he’s self-authorizing. He’s not waiting for things to become canonical,” Jafa said last year before an audience at the New Museum. “I would say I have a little of this as well. If we like the shit, it’s in the canon.”

Kahlil Joseph, Still from Fly Paper, 2017

Courtesy the artist

In 2016, Jafa created the film Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death, a tour de force that, like Fly Paper, reimagines the possibilities of narrative, sound, and movement in the construction of the moving image by relying on the black photographic, hip-hop music videos, and memory’s ability to create montage. Jafa’s Love Is the Message draws on a two-decade-long photographic study into what the filmmaker, who was the cinematographer for Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust (1991) and Spike Lee’s Crooklyn (1994), calls “black expressive modalities,” which resulted in two hundred notebooks of cataloged clippings of images from magazines of black athletes, entertainers, and ordinary people in motion. In twenty-four frames per second, soundtracked to an elongated mix of Kanye West’s 2016 rap gospel “Ultralight Beam,” Jafa seamlessly pulls together disparate images of violence and creativity. Before our eyes appear samplings of clips from YouTube of black voguers dipping, dash-cam video of Walter Scott being gunned down, former president Barack Obama emotionally singing “Amazing Grace,” LeBron James, Nina Simone, and black-and-white B-roll from his 2014 documentary Dreams Are Colder Than Death and Joseph’s Wildcat.

“How come we can’t be as black as we are and still be universal?” Jafa asked, in 2016, after the release of Love Is the Message. “How come we have to refuse who we are in order for someone to be able to identify with us? How come the audience can’t see themselves in that thing, whether or not it looks just like them or not?” He said, “It’s what black people do because most of what we see are white people. It’s what women have developed the muscle to do because mostly what they see are men. It’s what gay people are able to do because mostly what they see is heteronormative stuff. It’s a muscle that everybody needs to develop: the ability to see themselves in someone else’s circumstances without having to paint that person white, make that person straight, or a man.” Jafa added, “I’m trying to make my shit as black as possible and still have you deal with my humanity.”

Arthur Jafa, Still from Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death, 2016

Courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York/Rome

In the final sequence of Fly Paper, the sound of a woman’s voice, lifted from photographer and filmmaker Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil (1983), makes a declaration. As the screen flickers black, and the sound of striking lightning crashes, she says, as if responding to Jafa, “If they don’t see happiness in the picture, at least they’ll see the black.”

Fly Paper and Love Is the Message are works of black cinema that use available images of blackness in film and photography to probe the lack of full representations of blackness in the frame and on the screen. When Jafa presented his film in a recent solo exhibition, Arthur Jafa: A Series of Utterly Improbable, Yet Extraordinary Renditions at the Serpentine Galleries, London (2017), he displayed the photography of Ming Smith as an exhibition within an exhibition that showed, as the art historian W. J. T. Mitchell observed in his 2005 book, What Do Pictures Want?, that black pictures, like all pictures, “arise in all other media—in the assemblage of fleeting, evanescent shadows and material supports that constitute the cinema as a ‘picture show.’” Joseph’s Fly Paper is a new kind of picture show, one using the still black image to help us see more.

Antwaun Sargent is a writer based in New York.

Read more from Aperture Issue 231 “Film & Foto,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post At Least They’ll See the Black appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers