Aperture's Blog, page 2

October 17, 2025

A Miraculous Trove of Pre-Stonewall Secrets

In a photograph from the mid-1960s, identified as a “photo shoot with Lili, Wilma, and friends, Casa Susanna, Hunter, NY,” three women spill out from what appears to be the wooden slats of a closet door. The walls are clad in period-perfect knotty-wood paneling. The women, too, look fabulously of the moment, all kicky little mod dresses and gently curling bobs and headbands and horn-rimmed glasses and pearls. A fourth woman reclines, and yet another stands, filling the tiny room. All are holding cameras pointed at one another. In the corner, a blond with a wicked gleam in her eye trains her pocket-size camera on the person taking the picture. But she’s also winking at her future viewer, whom, one might imagine, every person in this photograph assumed would be someone like them: someone the world saw as a man but who found pleasure in seeing themselves as a woman. Which makes this photo not only joyous but dangerous. Because in appearing as women, each of them, in that moment, was committing a crime. And having the time of their life.

Andrea Susan, Photo shoot with Lili, Wilma, and friends, Casa Susanna, Hunter, NY, 1964–1968

Andrea Susan, Photo shoot with Lili, Wilma, and friends, Casa Susanna, Hunter, NY, 1964–1968The exhibition Casa Susanna at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, organized in collaboration with the Art Gallery of Ontario and Les Rencontres d’Arles, showcases this image alongside some 160 other works made by and for a community of cross-dressers in New York and beyond throughout the 1960s. (While many of these folks identified as “transvestites,” the exhibition’s curators use the term cross-dressers, and this text follows suit. All identifying pronouns are used per the curators’ direction.) This community had a series of hubs. The first was a wig shop on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue, run by Marie Tornell. One day in the mid-1950s, Humberto (Tito) Arriagada, who had moved to New York after serving in the United States’ Foreign Information Service during World War II, walked into the shop. It was love at first sight between Arriagada and Tornell—and love at second sight when Tornell met Susanna Valenti, the person Tito had been cross-dressing as since teenage years. The pair transformed Tornell’s shop into a dear, clandestine resource for cross-dressers at a time when New York’s so-called masquerade laws still criminalized wearing clothes associated with the “opposite” gender.

Andrea Susan, Daphne sitting on a lawn chair with Ann, Susanna and a friend outside, Casa Susanna, Hunter, 1964–1968

Andrea Susan, Daphne sitting on a lawn chair with Ann, Susanna and a friend outside, Casa Susanna, Hunter, 1964–1968 Susanna standing by the mirror in her New York City apartment, 1960 – 1963

Susanna standing by the mirror in her New York City apartment, 1960 – 1963Once this close-knit underground community had the looks, it needed somewhere to show them off. Tornell and Arriagada—now free to be Susanna Valenti more regularly—made their apartment a safe space. In a photograph of “Susanna standing by the mirror in her New York City apartment” (1960–63), the home is a charming hall of mirrors. At the forefront, Valenti poses seductively in a lavender-pink dress not far from the shade of the painted walls, her eyes burning with confidence through the chromogenic print. Behind her, her reflection shows off the elegant cut of her lavender dress; farther back still, another woman stands in front of another mirror, bent over some distant domestic task as a lamp gently illuminates the back of her neck. That lamp, too, is reflected, forming a pair that frames the woman’s dark hair. These photographs are charged. They are proof that their subjects could live as they wanted, happily. They electrify the viewer. They urge the viewer to take charge of their own lives.

The exhibition design groups photographs of women engaged in similar pursuits—posing in front of televisions, for example, or for Christmas cards complete with girly, curliecue well-wishes in ink. The subjects assert their identities through action. They are women because they look and act like women. Femininity is an achievement, and these photographs advertise the spoils. In these images, “wish I was her” becomes “wish you were here.”

Susanna and Felicity in the kitchen, Chevalier d’Éon, Hunter, NY, 1960–1963

Susanna and Felicity in the kitchen, Chevalier d’Éon, Hunter, NY, 1960–1963 Andrea Susan, Carlene playing scrabble, Chevalier d’Éon, Hunter, NY, 1960–1963

Andrea Susan, Carlene playing scrabble, Chevalier d’Éon, Hunter, NY, 1960–1963  Lili on the diving board, Casa Susanna, Hunter, NY, September 1966

Lili on the diving board, Casa Susanna, Hunter, NY, September 1966 Arriagada and Tornell certainly took charge of their own lives. In 1960, they began transforming a humble cluster of bungalows and a barn in the Catskill Mountains into Chevalier d’Éon—named for the eighteenth-century cross-dressing French spy Chevalière d’Éon—and invited their community to visit and stay. A photograph of “Susanna and Felicity in the kitchen, Chevalier d’Éon, Hunter, NY” (1960–63) shows two women thrilled to be in their element, the former camping it up with her leg on a stool while the latter, cross-legged, laughs and cuts her food as if at dinner theater. Like “Lili on the diving board, Casa Susanna, Hunter, NY” (1966), taken at the second resort Arriagada and Tornell set up in 1964, these are holiday snapshots. They’re proto-selfies. But they’re also performances: moments of people willing themselves into the kind of person and life they desire.

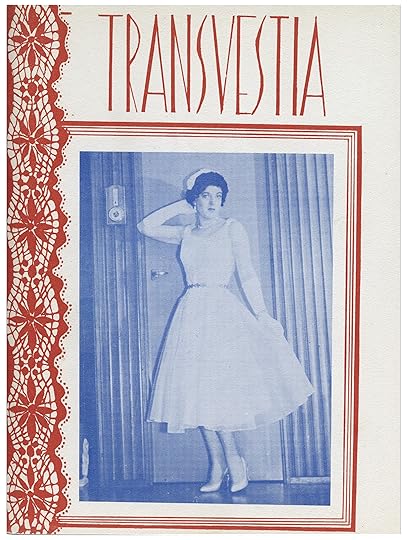

Transvestia vol II, no 8, March 1961

Transvestia vol II, no 8, March 1961All photographs © AGO

Casa Susanna surrounds these photographs with others taken in their friend Gail’s Greenwich Village apartment, along with copies of the groundbreaking Transvestia magazine, founded in 1960 by Virginia Prince to connect and celebrate cross-dressers across the country. Arriagada starred as Susanna herself for its December 1961 cover. The ephemera, alongside the photographs, help shape our contemporary understanding of transgender identity. Some of these individuals later took further steps towards living as women—medically and legally. Whether or not all the people in these images fit our current categories, the community they built offered the chance to experiment and escape the narrow confines of gender before the modern gay rights movement exploded.

Moreover, the exhibition emphasizes how Transvestia and its photographers seized the means of production: Before the DIY freedom of the Polaroid arrived, they must have had to find sympathetic photo-lab workers to develop their chromogenic and gelatin-silver prints. They certainly kept these photographs safe. Although countless images have been lost, much of this show draws from a cache discovered at a Manhattan flea market in 2004. The pictures are in such exemplary condition that there’s no doubt they were held dear, and perhaps close to the vest. This exhibition is proof not only that people have always refused the despicable gender laws now resurfacing in this country, but also that remaking the world in your own image is possible, vital, and a hell of a lot of fun.

Casa Susana is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, through January 25, 2026.

How Diane Keaton Moonlighted as a Photographer

Since Diane Keaton’s death last Saturday at age seventy-nine, much has been said about her great depths as an actor, one who brought to her best performances a vivacious vulnerability and flustered grace. She was other things too: an openhearted memoirist, a designer, an androgynous icon, a single mother. Less discussed is Keaton’s surprising contribution to photography, a medium she held close throughout her life.

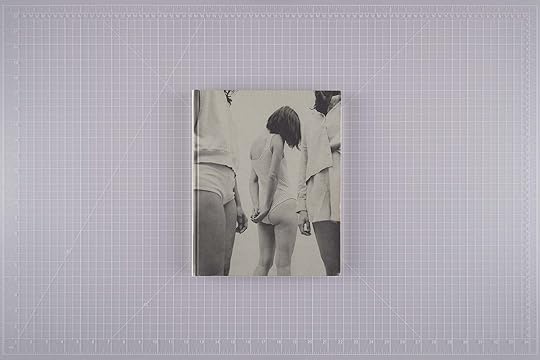

Cover and interior spread of Reservations by Diane Keaton (1980, Knopf)

Cover and interior spread of Reservations by Diane Keaton (1980, Knopf)A couple of years ago, a friend with unimpeachable taste gifted me Keaton’s first photobook, Reservations, published in 1980 by Knopf, and I’ve treasured it ever since. Like all great photobooks, it seems endowed with talismanic powers. Clad in a flamingo-pink cover, the monograph consists of forty-five black-and-white photographs of deserted lobbies and banquet halls in luxury hotels across the United States, taken during the 1970s—presumably as Keaton traveled around the country promoting New Hollywood classics like The Godfather, Annie Hall, Looking for Mr. Goodbar, and Reds, which had begun production in 1979.

When trying to describe the nervy warmth of Keaton’s performances, people often resort to “lived-in,” that film-criticism cliché. Her photographs are seemingly the opposite: unpeopled, icily observed interiors that announce a “strong, direct photographer with a cool and deadly eye,” as the jacket copy puts it. The book makes no mention of her acting credits, and why should it? No mere vanity project, Reservations is an angular meditation on American emptiness, the kind Todd Hido would thematize to enormous success two decades later. Keaton locates a wry, forlorn comedy in awkward furniture, plastic plants, florid wallpaper, ersatz backdrops, quirky light fixtures, and conspicuous cables snaking down white walls, all shot deadpan (a word coined in the 1920s for that other Keaton, Buster) and gilded with a harsh flash that renders surfaces slightly unreal.

Interior spread of Reservations by Diane Keaton (1980, Knopf)

Interior spread of Reservations by Diane Keaton (1980, Knopf) Interior spread of Reservations by Diane Keaton (1980, Knopf)

Interior spread of Reservations by Diane Keaton (1980, Knopf)Certainly, the other Diane looms large in the perturbing directness of these photographs. Like Arbus, Keaton favored Rolleiflex cameras, though she was probably less fussy about film type. One especially Arbus-like image finds two cheerless Christmas trees installed atop a pair of tables at the Ambassador, a hotel whose demolition Keaton fought passionately against as a member of the Los Angeles Conservancy. That several of these hotels have since met the wrecking ball or changed to overseas ownership lends the photographs an elegiac air. This quality finds its fullest expression in a phalanx of stacked chairs in the ballroom of the Waldorf Astoria, or perhaps in a photograph of a small dining table, marooned in a sea of plush carpet at what was then the Fontainebleau Hilton in Miami Beach.

Keaton’s interest in photography was wide-ranging. In the late 1970s, she struck up a friendship with the curator and writer Marvin Heiferman, who was then working at Castelli Graphics gallery in New York. They went on to collaborate on several books and exhibitions, including Still Life: Hollywood Photographs (1983), Local News: Tabloid Pictures from the Los Angeles Herald Express (1999), and Bill Wood’s Business (2008), which features the work of a Fort Worth studio photographer whose negatives—all ten thousand of them—had sat in Keaton’s closet for twenty years.

Interior spread of Reservations by Diane Keaton (1980, Knopf)

Interior spread of Reservations by Diane Keaton (1980, Knopf) Interior spread of Reservations by Diane Keaton (1980, Knopf)

Interior spread of Reservations by Diane Keaton (1980, Knopf)All photographs by Madison Carroll

“She was so smart about pictures,” Heiferman told me. “We would go into archives and sit there and be elbowing each other, laughing, pointing at things, going, ‘Oh wow, isn’t this weird?’” Her taste, he said, helped spur a wave of interest in commercial and vernacular photography. She was an obsessive collector and a habitué of flea markets on both coasts. Her ultimate fantasy, she once told an interviewer, was to purchase every photography book ever published. “My mission is to buy an old warehouse I can transform into a massive library of image-driven books and open it to the public.”

In 2007, Keaton’s friend Larry McMurtry wrote an essay in The New York Review of Books calling attention to her writing on photography. In a letter to the editor, none other than Janet Malcolm chided the Lonesome Dove author for failing to note Keaton’s own work as a photographer. Malcolm praised the “mordant melancholy” of her Reservations images, arguing that they “established her place in contemporary photography” and “form the pendant to Keaton’s wonderful acting career.” Diane Keaton’s place in the photographic canon is hardly assured, of course. She probably wouldn’t mind. Long out of print, Reservations and her other photobooks endure nonetheless, as yet another testament to the compulsive creativity and liberated spirit of an artist who inhabited many different roles in life, all of them herself.

October 10, 2025

Nikki S. Lee Stays in the Picture

Nikki S. Lee’s name carries a strange currency in the Korean art world, sparking instant recognition but also a sense of enduring mystery. After all, Lee’s breakout series, Projects (1997–2001), which began as a graduate-school project and was first exhibited while she was in her twenties and living in New York, saw the artist assume the guise of over a dozen of characters as she descended into different US subcultures, photographing herself amid drag queens, punks, skateboarders, strippers, and other communities mostly on the fringes of society. The series catapulted Lee to international stardom, while establishing her as something of an enfant terrible, all while raising a question that was never really answered: Who is the “real” Nikki S. Lee? Her mystique deepened in the aughts when Lee, whose work is so preoccupied with what it means to belong, chose to walk away from the New York art world entirely.

I encountered Lee and her art for the first time through a part-time job. In 2013, as an undergraduate art history student, I worked as a gallery guide at one of her solo exhibitions in Seoul, where she has long been based. Day after day, I stood among her large-scale prints, reciting information to visitors while observing how they responded—some with recognition, some with confusion, and others with quiet reverence. By then, series such as Projects, Parts (2002–5), and Layers (2008) had already cemented Lee’s reputation. For Korean students of photography and visual art, she was foundational. Unlike many contemporaries whose imagery was geared toward geopolitical history, political activism, or typical national narratives, Lee’s gaze turned inward, exploring identity as something performative, fluid, and unresolved. Her reputation as an artist who was even more famous overseas made her career particularly fascinating.

Nikki S. Lee, The Ohio Project (6), 1999

Nikki S. Lee, The Ohio Project (6), 1999  Nikki S. Lee, The Punk Project (1), 1997

Nikki S. Lee, The Punk Project (1), 1997 When I met Lee again this past spring at her studio in Seoul’s Itaewon neighborhood, over a decade later, she was radiant and quietly reflective, generous with her stories but never indulgent. Our conversation stretched across a long afternoon in her studio, touching on her singular practice, her relationship with identity, and her enduring desire to remain in motion, always chasing the present while never quite escaping the past. Her father was a photographer, and Lee, who was born in 1970, grew up surrounded by images. “I was ambitious, driven,” she said. “I wasn’t afraid to throw myself into whatever I wanted to do. But at the same time, I had a strong literary sensibility. Even as I chased my goals, I often felt a deep emptiness about life. There was always this quiet sadness inside me—a tenderness, maybe.” Still, she never really thought of picking up the camera herself until she decided to study photography at Seoul’s Chung-Ang University, where the curriculum was highly technical and traditional. She grew curious about other creative fields and, after graduating, moved to the United States and enrolled at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology, where she took fashion-design classes alongside her photography studies. It was the era of supermodels and grunge, and the line between art and commerce, and art and life, was becoming harder to find. Lee had hopes of becoming a fashion photographer, and she needed an English name. One day, flipping through an issue of Vogue while applying for an assistant position with David LaChapelle (a job she would get), she came across the model Niki Taylor. For some reason, the name spoke to her.

Lee subjected the New York art world’s newfound ideals of inclusivity to an ambiguous acid test.

During her graduate studies in photography at New York University, Lee’s practice took a sharp turn. At NYU she was given space to step away from commercial work and focus on defining her own language as a fine artist. But more than any institution, the city itself changed her. “I lived in the East Village. It was rough but also magical,” she said. “From 1994 to around 2009, I think New York had this golden period. There was a balance between freedom and safety, between chaos and creativity. There was energy in the streets, a sense that anything was possible. You could live however you wanted and invent your own rules. It was a place where fixed ideas didn’t really exist. It felt like the right place for someone like me, who didn’t want to follow convention.”

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

After finishing her MFA at NYU, Lee rose to prominence with Projects, her now-iconic series documenting her immersion into various demimondes: skateboarders, punks, yuppies, lesbians, hip-hop fans, high-school students, seniors, and more. Like the New York–based artists Cindy Sherman and Adrian Piper, Lee used performance to negotiate the construction of gender, race, and the self. Yet unlike them, Lee didn’t emerge from the context of American second-wave feminism, and her images, which at first glance resemble candid snapshots, were, in fact, the result of monthslong embedding and assimilation. Lee would adopt the clothing, gestures, slang, and social rituals of each group, documenting her transformations with the help of a friend or stranger who would release the shutter. Lee began Projects in 1997, at a time of reckoning around issues of representation and identity within the US art world, and her chameleonic provocations, teetering between irony and sincerity, seemed to subject its newfound ideals of multiculturalism and inclusivity to an ambiguous acid test.

One of the most physically grueling chapters of the series was The Skateboarders Project (2000). “I fell so many times,” Lee said. “My body was sore the entire time. I had to wear patches on my arms and legs. Physically, it was exhausting. I remember skating near the East River—there were a lot of makeshift skate parks there. Usually, my projects last about three or four months, but this one took a real toll on me.” Another challenging chapter was The Exotic Dancers Project (2000), for which Lee worked at a strip club on the outskirts of Hartford, Connecticut, and undertook a strict dietary and training regimen. “That one was so lonely,” she remembered. “I stayed in a motel near a highway, in this desolate, isolated place. The motel was in the middle of nowhere. Every night, I went out to the clubs, and during the day, I was alone. That solitude really got to me.”

Nikki S. Lee, The Exotic Dancers Project (20), 2000

Nikki S. Lee, The Exotic Dancers Project (20), 2000  Nikki S. Lee, The Yuppie Project (19), 1998

Nikki S. Lee, The Yuppie Project (19), 1998 With Projects, Lee became a star almost overnight. “My very first work was reviewed by The New York Times,” she recalled. “Honestly, I didn’t even know I was going to become an artist. I was just doing a school project. Suddenly, everyone was calling me an artist.”

The attention, though thrilling, was disorienting. The pressure was less about being in the spotlight than about the fear of being a one-hit wonder. “I remember thinking, If I don’t do well with my next project, maybe I was just lucky. Maybe it’ll all fade away. I didn’t want to be that kind of artist—the kind who peaks early and disappears.”

Lee’s embrace of stereotypes, especially in Projects, has drawn accusations of cultural appropriation, and she could sometimes resort to racist caricature, as in The Hip Hop Project, for which she appeared in blackface. Such photographs reveal less about the limits of assimilation than they do about the limits of Lee’s own series, whose often nuanced commentary on power dynamics and liberal visibility politics could, without a sense of emotional authenticity, succumb to empty farce. But Lee remains unfazed. “Projects is timeless,” she said, laughing. “I think I did well. Depending on the political climate, sure, it could be controversial. But that’s not the point. The point is, people are still talking about it twenty, twenty-five years later. That’s what matters.” There’s a saying in Korea: What’s scarier than criticism is silence. In other words, indifference is more humiliating than disapproval.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

That pressure led to Parts, a series in which Lee photographed herself with various male partners, later cropping the men out of the frame so that only fragments of their bodies remained. The gesture underscored the idea that identity, especially in intimate relationships, is shaped relationally, sometimes even erased in the process. She followed that line of inquiry with Layers, made the year Lee moved from New York back to Seoul. For Layers, Lee traveled to various cities around the world, asking local street artists to draw her portrait. She then superimposed three of these interpretations in a single light box, creating a hybrid image that was at once hers and not hers—a visual echo of the mutability she has always explored.

While many critics and curators have framed her work as an inquiry into Asian American identity, Lee resists that reading. “People always say my work is about identity,” she said. “But I’ve never questioned my own identity. I was born in Korea. I grew up Korean. That’s never been in doubt. My sense of self has always been fluid but not uncertain. I wasn’t searching for an identity—I was just trying to show that identity is something you can perform, mold, and play with. It wasn’t about proving anything. It was about saying, ‘Look—I can do this too.’”

Nikki S. Lee, Part (3), 2003

Nikki S. Lee, Part (3), 2003  Nikki S. Lee, Wedding (8), 2005

Nikki S. Lee, Wedding (8), 2005All photographs © the artist and courtesy Sikkema Malloy Jenkins, New York

Though best known for her photographic series, Lee was never entirely comfortable with the label of photographer. “I’ve never once dreamed of being a photographer,” she stated. “To me, photography was just one medium I happened to use. I never saw it as the end goal.” This is probably why Lee took a break from still photography for a while, turning instead to video and painting. An emblematic 2006 video piece, a.k.a. Nikki S. Lee, is a pseudodocumentary in which she plays herself—or rather, several versions of herself, blurring the line between fiction and reality. More recently, she has returned to painting, a medium she rarely discusses publicly. “The paintings I’m working on now are totally different in character from my earlier works,” she said. “They’re not even related, really. But I’m following my instincts.”

This year, Lee will release a new video, exhibit in a group show, and publish a book cowritten with the essayist Im Ji-eun, a close friend. “We meet almost every day,” Lee said. “We start with lunch and end up talking until dinner. One day, we joked about starting a podcast, but then we thought, Why not turn these conversations into a book?” The result is about artificial beauty, a meditation on aesthetics, artifice, and the human-made. “People always talk about the beauty of nature,” Lee said. “But I love artificial beauty. Art is human. It’s artificial by definition. And I think there’s something really beautiful about that.” Seoul—a site of ceaseless reinvention, and now a viable candidate for the plastic surgery capital of the world—is perhaps a fitting home for an artist so invested in the malleability of the self.

Recently, Lee founded a creative management agency called Beatnik in the city. Currently, Beatnik manages one actor—her partner, Teo Yoo—and is preparing to sign a young actress. “It’s not a separate thing from my art,” Lee said. “It’s just another way of being in the world creatively.” Lee and Yoo married in 2007, and Yoo’s recent success with films such as Celine Song’s Past Lives (2023) has rekindled interest in Lee’s work locally, though her art has long been circulating in Korea, and was featured in the 1999 Gwangju Biennale.

When I asked what her long-term goals are, she laughed. “I don’t usually set big goals. I focus on short-term things . . . I just want to make sure I’m enjoying the moment. If I don’t want to do something, I won’t do it.” She added, “But there is one big goal. When I’m on my deathbed, I want to be able to say: ‘I lived as an artist.’ If I can say that, I think I’ll be at peace.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 260, “The Seoul Issue.”

A Native American Artist’s Prayer for Home

An earlier version of this article was originally published in Aperture, fall 2020, “Native America,” and was updated and expanded for Kimowan Metcheswais: A Kind of Prayer (Aperture, 2023).

For the 2002 installation Without Ground, the Cree artist Kimowan Metchewais transferred dozens of small photographic self-portraits to the white walls of the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) at the University of Pennsylvania. The full-length likenesses were posed in the ICA’s Ramp Space, as if they were searching the empty expanse for something hidden from both artist and viewer. By cleverly using scale and gently fading some of the photo transfers, Metchewais, who went by his stepfather’s surname, McLain, at the time, created the illusion of figures receding into space. Treating the walls of the museum as the “ribcage of a living animal,” he felt that his photographs were like “tattoos etched onto the bones of the beast,” anticipating their burial within the institution’s architectural memory, covered by future layers of accumulated paint.

Over a decade later, in 2014, the Omaskêko Cree artist Duane Linklater meticulously scraped away layers of paint from the ICA’s walls, creating stratified craters in search of the installation. The effort to uncover these photographic traces was akin to a search for Metchewais himself, an attempt to connect with the artist who had passed away only a few years earlier, in 2011. The hunt for evidence was forensic, replicating the investigatory nature of Metchewais’s wandering figures. “I think North America is a crime scene,” Metchewais said of Without Ground in 2006. “Something was lost and it needed to be found. The figures were detectives, a search party. I wanted them to be looking for the crime itself. . . . I hate to say it, but what happened to the land and people here was/is a crime. People today don’t see that. They understand it, they know it, but it doesn’t seem to mean that much to them. To me, it means a lot, in many ways.”

Without Ground lacks perspectival space or a defined horizon line, evoking the Pueblo watercolors of the Studio style—which typically favored depicting costumed dancers on neutral grounds—that developed out of the Santa Fe Indian School in the early twentieth century. Metchewais, however, insisted that the land in these paintings was not actually absent but rather “unseen,” a symbolic denial of ground taught to the Studio painters that corresponded with the historic displacement of Indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands. His installation at the ICA was thus about seeking an invisible landscape and the crime behind its loss and continued absence. The white museum wall, rather than a neutral ground, became a site at which to consider the theft of Indigenous land, underscored by the installation’s title, an example of the ways in which Metchewais rearticulates colonial memory through photography. “I am concerned about how people see the landscape of North America,” Metchewais said while speaking about Without Ground. “I want the land to be omniscient.” In this statement lies the breadth of his practice, which moved between perception, representation, and understanding the capacity of the land to sense and speak for itself. His work explores the ground, aesthetic and territorial, on which contemporary Native art and communities might stand, and his images propose a new intellectual space that exceeds the mere subversion of stereotypical representation.

Kimowan Metchewais, Raincloud Over-the-Head, Masque Collection, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, ca. 2010

Kimowan Metchewais, Raincloud Over-the-Head, Masque Collection, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, ca. 2010  Kimowan Metchewais, Lucky Strike/Green, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, ca. 2002

Kimowan Metchewais, Lucky Strike/Green, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, ca. 2002 Consider Metchewais’s most lauded work: the Cold Lake series (2004–6). It consists of photographs of children and other community members from the artist’s homeland of Cold Lake First Nations, a Cree and Dene reservation in Alberta, Canada, pictured in the style of straight photography on the street or wading in the namesake Cold Lake. Metchewais returned repeatedly to his home to take thousands of photographs of Indigenous children, who he sought to depict as a youthful and emergent force. These works form the bulk of the sub-series that the artist titled Child Nation. Notes in Metchewais’s sketchbooks from about 2000 also propose what he called “post-Curtis portraits,” works that are empty of ethnographic baggage and instead emote “reclamation” and “a desperate, pathetic attempt to restore” and “elevate human status. It seeks to be heroic. It wants to be owned.”

This label is a reference to and an attempt to move beyond the outsize influence of the photographer Edward Curtis, whose staged and romanticized portraits from the twenty-volume anthropological series The North American Indian (1907–30) have permeated the visual imaginary. The post-Curtis portrait is also about community, place, and belonging. “To be Indian, Inuit,” Metchewais writes, “that is in the heart.” In Young Mothers at Cold Lake (2005), four women gather knee-deep in the water, smiling and laughing together; one looks backward to keep an eye on her children, who are outside the frame. Other images from the series are taken on the streets of Edmonton and at powwows. But the artist’s attention was mainly reserved for creating striking three-quarter length or closely cropped portraits of children in the lake waters.

His most well-known image from the series, Cold Lake Venus (2005), features a young girl facing the camera, hip-deep in water that stretches behind her to meet the sky at the horizon. The photograph is saturated with what Metchewais calls “divine beauty,” which emanates from the girl like the ripples in the lake water. “Look at us emerge. We are beautiful, standing in a magical place, just back from the Wal-Mart [sic],” Metchewais writes of the work. His wry superstore reference dispels the tendency in the popular imagination to take Indigenous communities out of time when romanticizing their ties to the landscape. He succeeds in picturing new image worlds to express a fundamental connection to home and place while evoking Indigenous and Greek creation myths.

Kimowan Metchewais, Cold Lake Venus, Cold Lake First Nations, Alberta, Canada, 2005

Kimowan Metchewais, Cold Lake Venus, Cold Lake First Nations, Alberta, Canada, 2005Born in 1963, in Oxbow, Saskatchewan, Metchewais adopted his mother’s maiden name in the latter part of his life. He began his career making political cartoons and graphics for Windspeaker, Canada’s most widely distributed Indigenous-content newspaper, before receiving a BFA from the University of Alberta in 1996. His early work tackled the legal and cultural frameworks of Indigenous identity and tribal membership, questioning the means by which identity is defined and challenging the demand, still present today, for Indigenous artists to perform a so-called authentic connection to land, language, and community. His 1989 painting A Guide to Doing Contemporary Indian Art pokes fun at the collage aesthetic prevalent in the work of First Nations contemporary artists in the 1980s, such as George Longfish, Jane Ash Poitras, and Joane Cardinal-Schubert (who was a mentor and purchased the piece). Handwritten penciled text on a red-painted rectangle instructs: “Place images below . . .” “old photographs,” “some modern stuff for contrast,” “syllabics,” “buffalo(s),” “a few tipis,” and so forth.

Metchewais received his MFA from the University of New Mexico (UNM) in 1999. He was attracted by the school’s well-regarded photography and Native American art history programs, and found there a network of Indigenous classmates including Larry McNeil, Will Wilson, and Rosalie Favell. While at UNM he began to rigorously develop the photographic and mixed-media practice he is known for today. He challenged the authority of fixed representation while pursuing answers to the question of authenticity that he asked of himself and his work: “What makes Indian people Indian?” His mixed-media compositions and elaborate photo collages incorporate references to Native art history: winter counts, ledger paper, and parfleche designs juxtaposed with images of urban and natural landscapes in Sandias (1998); portraits of Plains elders mined from archives and popular culture, and those taken with his own lens, in The Origin of Tobacco (2000). His 1999 installation After, first exhibited in his MFA thesis show at UNM’s John Sommers Gallery, featured illusionistic photo transfers depicting birds, insects, and bowls on the gallery walls, a process Metchewais called “photographic gallery tattoos.” It was an antecedent to the later ICA installation Without Ground and exemplified his “search of elegant solutions to challenges of narrative in space.”

Kimowan Metchewais: A Kind of Prayer 75.00 A Kind of Prayer presents the first-ever survey dedicated to the late Cree artist Kimowan Metchewais and his singular body of work on Indigenous identity, community, and colonial memory.

Kimowan Metchewais: A Kind of Prayer 75.00 A Kind of Prayer presents the first-ever survey dedicated to the late Cree artist Kimowan Metchewais and his singular body of work on Indigenous identity, community, and colonial memory. $75.0011Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

Kimowan Metchewais: A Kind of PrayerPhotographs by Kimowan Metchewais. Text by Christopher T. Green, Kimowan Metchewais, Emily Moazami, and Jeff Whetstone. Designed by A2/SW/HK, London.

$ 75.00 –1+$75.0011Add to cart

View cart Description A Kind of Prayer presents the first-ever survey dedicated to the late Cree artist Kimowan Metchewais and his singular body of work on Indigenous identity, community, and colonial memory.After his untimely death at age forty-seven in 2011, Metchewais left behind a wholly original and expansive body of photographic and mixed-media work. At the center of his practice is an extensive Polaroid archive, which addresses a range of themes—including the artist’s body, performative self-portraiture, language, landscapes, and everyday subjects—and served as the source material for works in other media, such as painting and collage. Metchewais’s exquisitely layered works offer a poetic meditation on his connection to home and land, while challenging conventional narratives and representations of Indigeneity.

Metchewais was a contemporary artist of stunning originality, and until now, his work has been woefully understudied and underexposed. A Kind of Prayer is a comprehensive overview that showcases this essential artist’s astonishing vision. Details

Format: Hardback

Number of pages: 268

Number of images: 150

Publication date: 2023-01-10

Measurements: 7.75 x 10.55 x 1 inches

ISBN: 9781597115322

“Kimowan is a gift – an important voice for Native artists and the contemporary art world. He left us before he got the recognition he so deserved, but we can continue to learn and gain inspiration from the work he left behind.” —Wendy Red Star, The New York Times.

“A Kind of Prayer presents the first-ever survey dedicated to the late Cree artist Kimowan Metchewais and his singular body of work on Indigenous identity, community, and colonial memory.” —Photo London

“The Photographer 2000, a mixed-media artwork by Kimowan Metchewais, whose monograph A Kind of Prayer was published in January by Aperture. Metchewais’s work is on view this month as part of the exhibition Native America: In Translation at the Milwaukee Art Museum.” —Laena Wilder, Harper’s Magazine

“A Kind of Prayer is an exploration of Indigenous identity and community, as seen through photography and multi-media work of the late Cree artist Kimowan Metchewais.” —International Center of Photography

“A monograph that is both a photobook and a scholarly publication but, as its subtitle suggests, also an expression of something that lies beyond analysis of the physical world.” —Maymanah Farhat, The Brooklyn Rail

ContributorsKimowan Metchewais (1963–2011; born in Oxbow, Saskatchewan, Canada) was a multidisciplinary Cree artist who began his artistic career working as an illustrator and editor at the Native newspaper Windspeaker. He later received his bachelor of fine arts at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada, before completing his master of fine arts at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. In 1995, Metchewais received the Ellen Battell Stoeckel Fellowship to spend the summer at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, and in 1996, a national award from the Canadian Native Arts Foundation. At the time of his death, he was associate professor in the art department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Christopher Green is a writer and art historian whose research focuses on modern and contemporary Native American art and material culture. His work has appeared in Aperture, Artforum, Art in America, and Frieze, among other publications.

Emily Moazami is assistant head archivist at the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC.

Jeff Whetstone is professor and head of photography at Princeton University, New Jersey.

Essays Can the Photo-album Hold Cultures Together?

Essays Can the Photo-album Hold Cultures Together?  From the Editors How Can Native Artists Challenge the Story of North America Today?

From the Editors How Can Native Artists Challenge the Story of North America Today? The Polaroid was core to Metchewais’s process, and while at UNM he began amassing an extensive personal archive, meticulously organized during his lifetime by subject and alphabetized in boxes. He used these photographs as references for his paintings and embedded them in his mixed-media collages and as transfers to large-scale works on paper. He cut up, rearranged, and taped them back together before rephotographing and reentering them into the collection as a shifting and circulating living archive. The tactility of the cut-up photographs, with conspicuous scratches, creases, and Scotch tape fastenings, distinguishes them from digital images, and Metchewais sought to maintain these qualities even when he rephotographed his Polaroids and digitally printed them. He commented at the 2009 conference Visual Sovereignty at the University of California, Davis, that “few things compare to the silky touch of a newly developed print in the palm of one’s hand.” His Polaroids also freed him from a reliance on archival images from outside sources. Instead, Metchewais’s use of personal imagery avoided the need for intervention, interrogation, and reinscription that weighs down some work by contemporary Native photographers who explore museum and institutional archives as sites of privileged access, subjugation, and colonial violence.

Kimowan Metchewais, Storyteller, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 2000

Kimowan Metchewais, Storyteller, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 2000  Kimowan Metchewais, Structure 07, New Mexico, 1997

Kimowan Metchewais, Structure 07, New Mexico, 1997 Metchewais’s Polaroids contain many series: toy buildings and animals shot in a studio; smokestacks and mountain ranges; flowers, cars, and other quotidian objects. Many are portraits depicting family, friends, classmates, and colleagues, and being from many periods of his life they serve as both an essential precursor to and extension of the deep exploration of community seen in the Cold Lake series. Portraits include his brothers, Hans and Luther; Archie Seelkoke, an Alaska Native man that Metchewais met in Albuquerque; fellow photographer and friend Laena Wilder; and many more faces from his home, his time at UNM, and his later colleagues in North Carolina. These individual portraits are an archive of stories, personalities, and bodies, occasionally cut up, rearranged, and accompanied by biographic annotations in Metchewais’s notebooks.

The artist frequently includes his own body in this archive. In one undated set of Polaroids, he photographed his own hand in a series of gestures, some of which were later modified and digitally printed under the title Indian Handsign. Loosely held poses of fingers and arm recall anatomical studies, while distinct hand shapes suggest a form of sign language. On these Polaroids, Metchewais penciled labels directly below the images: a trigger-finger pose is labeled “GO”; an upward-facing palm is labeled “OPEN.” The hand signs function as study and reference materials while also triangulating a relationship between body, language, and image. The signs do not appear to be based on American Sign Language but rather obliquely reference Plains Sign Talk, a historical sign language used by Indigenous peoples across central North America in trade and oratory. Purported manuals for Plains Indian Sign Language were published throughout the twentieth century, and the language was widely appropriated by the Boy Scouts and other non-Native summer camps and societies. The images also recall the hand signals from the rapidly paced Cree handgame (or “stick game”) that Metchewais played with his uncles on Cold Lake First Nations. Eraser smudges on the Polaroids suggest that Metchewais wrote and rewrote the labels, drafting his own language for this series of universal gestures, countering appropriations with a new baseline of bodily signs. In some instances, he printed multiple photographs on single sheets of paper in three-by-four arrangements of hand gestures, forming a kind of visual dictionary or record.

Metchewais images propose a new intellectual space that exceeds the mere subversion of stereotypical representation.

Metchewais circulated language throughout his work, often in deeply personal ways. Images of his grandmother’s Cree-language Bible recur in his oeuvre, including in works that reproduce its worn leather cover and front matter, namely a page of the Cree syllabic alphabet with French phonetic translations. Metchewais often signed his name Kimowan in Western Cree syllabics, ᑭᒧᐘᐣ, which means “it is raining.” In several versions of his 2004 photo collage Cold Lake, the Cree name for the lake, atakamew-sakihikan, appears in syllabics underneath the English. These works are examples of what he called his “paper walls,” photographs printed on paper sheets taped together into wall-size constructions. Emulating Plains parfleches, Metchewais designed such works to be mobile, foldable into transportable packets that can be tucked under one’s arm as a carry-on until unfurled into nearly room-size installations. They also make clear why Metchewais identified himself not as a photographer but rather as “a sculptor of flat, rectangular objects of various textures and tone.” Some of the pieces of tape are in fact photographic images of paper taped together, such that the simulation of texture blurs reality with representation. The papers were dipped in water colored by rust and tobacco, “baptized,” in the artist’s words, as a ritual act. Because tobacco is a sacred substance among many Indigenous peoples, the material of the work might be considered animate. “Tobacco is a handshake. It signals honesty and honorable intention. Cold Lake is a kind of prayer,” Metchewais said.

Kimowan Metchewais, Cold Lake, Cold Lake First Nations, Alberta, Canada, 2006

Kimowan Metchewais, Cold Lake, Cold Lake First Nations, Alberta, Canada, 2006  Kimowan Metchewais, Goodwill, 118 Avenue, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, 2005

Kimowan Metchewais, Goodwill, 118 Avenue, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, 2005 That prayer is about home, family, and memory. Cold Lake includes multiple iterations of a scene of Metchewais and his cousin Conrad wading below the long horizon line of the lake. It combines several snapshots taken from shore by the artist’s mother. The photographs are “a record of family love,” binding Metchewais, his family members, and the lake and sky in kinship relations. Given the installation’s wall-size scale, the close viewer becomes wrapped in the experience and memory of that place. These works are less about the recovery or performance of memory than a living relation to the land. They also situate home and place as terms that escape essentialism. In Goodwill, 118 Avenue, Edmonton (2005), Metchewais captured a scene of furniture donations awaiting pickup along a wall in an urban Native neighborhood. The orderly rectangles evoke modernist compositions in what Metchewais called “a Mondrian and serendipitous scene.” For the artist, they also stand in as one of many incarnations of home, both territorial and adopted. His shadow appears on the right edge of the photograph, an index of his presence in the Edmonton neighborhood that he called “an unofficial reservation in the city.”

Kimowan Metchewais, Striped Man, Brother Luther McLain, Albuquerque, 1998

Kimowan Metchewais, Striped Man, Brother Luther McLain, Albuquerque, 1998  Kimowan Metchewais, The Marlboro Man/ A Man Named Lucky, The Origin of Tobacco, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 2000

Kimowan Metchewais, The Marlboro Man/ A Man Named Lucky, The Origin of Tobacco, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 2000 Metchewais was ever conscious of the pitfalls of representation and stereotypes. In 1999 he began a post-doctoral fellowship at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and taught in the studio art program there until 2011, reaching the rank of associate professor. When he arrived in North Carolina, the birthplace of his white stepfather, he began to more regularly go by his mother’s maiden name, Metchewais, reflecting his difficult relationship with Mr. McLain. His course-planning notes include outlines of the histories of depicting Native America, from the trope of the noble savage to the erroneous notion of the vanishing race. His sketchbooks contain drawings based on art-historical representations, such as copies of the famous portraits of Native American delegates and visitors to Washington, DC, drawn by Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin, from 1804–7.

Yet Metchewais’s fully realized works show little of the typically overwhelming concern among Native American photographers of his generation with debunking and overturning such stereotypes. Instead, his self-portraits pursue the kind of “self-made Native imagery” he saw in online culture, as he wrote on Facebook in 2009. He fashioned a host of such characters as the Marlboro Indian smoking a cigarette in a cowboy hat (Marlboro Indian, 2000). In a series of self-portraits from 2000, Metchewais’s shirtless upper body, painted dark blue from the chin down, sparkles with starry points of light like the cosmological images from the late nineteenth-century ledger art of the Itázipčho Lakota artist and visionary Čhetáŋ Sápa’ (Black Hawk). Several photographs from Metchewais’s graduate-school period, Ghostdancer (1998) and Striped Man 02 (1998), depict his brother, Luther, wrapped head to toe in a black-and-white striped textile—a body that, while abstracted, evokes the heavily romanticized image of the Plains Indian wrapped in a chief’s blanket and the loaded history of disease-laden trade blankets.

Kimowan Metchewais, Self-portrait with long hair, Albuquerque, 1998

Kimowan Metchewais, Self-portrait with long hair, Albuquerque, 1998  Kimowan Metchewais, Self-portrait with long hair, Albuquerque, 1998

Kimowan Metchewais, Self-portrait with long hair, Albuquerque, 1998 In 1993, Metchewais was diagnosed with a brain tumor that chased him for the rest of his life. Surgery and subsequent treatments left him with a permanent bald spot on the back of his head. In a series of Polaroid self-portraits, Metchewais, in a white tank top and faded jeans, dons a hairpiece that stretches to the floor. In two Polaroids that he took to fully capture the length, he drapes the hair over one arm and allows it to drag along the floor beside his bare feet. In another Polaroid, the hairpiece is pictured lying snakelike on the floor. Long hair was a sign of Indianness to Metchewais, and he incorporated his own hair into some of his sculptural installations. In a 1984 comic for Windspeaker, a cartoonish Native man with long braided hair, perhaps representing the artist, asks, “Tell me . . . what is the true essence of being an Indian?!” A guru on a mountaintop replies, “That all depends . . . on if your mother married off the reserve before or after 1950 . . . how long yer hair is . . . how much pure blood you have.” Visual markers and the “poetics of identity”—hair, tobacco, place—were of great interest to Metchewais, who noted in the proposal for his University of North Carolina postdoc that it would be worthwhile to “question what it is to be an Indian with a white father.” The exaggerated length of the hairpiece and its visible artificiality compose an ironic take on this sign of Native identity while highlighting what was both a vulnerable feature for the artist and a site, as he explained, to investigate his “bi-racial identity and the ensuing ambiguity [that] falls in line with my interest in contradiction.”

Kimowan Metchewais, Indian Handsign, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1997

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }Following complications from one such surgery, in 2007, Metchewais lost the capacity for movement and feeling in the left side of his body. One notices that his hand-sign Polaroids are almost exclusively of his right hand. Many of the words labeling the Polaroids—“TOUCH,” “FLIGHT,” “RECALL,” “CHANGE”—took on a different valence in the wake of his partial paralysis. Metchewais called his studio “a laboratory” where he conducted an “archeology of the self,” and in the years following his surgery, he seemed to come to terms with his body, identity, and artistic practice. As curator Lois Taylor Biggs adeptly observes, “Metchewais blurred the boundaries of the body and the archive for the purpose of healing,” and his practice as personal archive served as medicine, both a “site of healing” and “a living body.”

Grow All Over Again (2008), a short film by Christina Wegs, intimately documents Metchewais discussing this process and his return to the studio after a hospital stay and period of rehabilitation. In the film, he describes a desire to revisit his old works and “to paint white and black rectangles over all the shit that I don’t like, and then go from there.” In a mixed-media work, Self-Portrait with Peach Brain Tumor (ca. 2006) the upper right and lower left sides of his face are split between two cut Polaroids that cast his skin color in different tones, one pink and the other bronze. Amid the Scotch tape is a series of inked black and beige rectangles that spread across the artist’s face but don’t mask his features. The original Polaroids were taken in 2000, prior to his 2007 surgery, but the modifications suggest he continued to explore his body as a site of the etched cultural markers of ethnic and corporeal identity.

Kimowan Metchewais, Self-portrait, ca. 2006

Kimowan Metchewais, Self-portrait, ca. 2006As Metchewais rehabilitated and worked his way back into the physical studio, he began to transition his attention from analog photographic processes to the digital space, which he understood as a natural site for Indigenous subjectivity. “It turns out the thing in the modern world that most matches the Indian psyche is the web,” he wrote in 2009. His personal website and blog, “Images & Other Curios,” became a space to share his work, personal reflections on art and the artistic process, updates on his health, and other musings. He often gave his website background the texture of his folded paper works, bringing his love of photography’s tactility to the screen. He began a vibrant experimental video practice on YouTube, including kaleidoscopic treatments of his own face and banal videos of him shaving, and used Facebook and his blog as galleries for found images, not unlike his self-made Polaroid archive. The Facebook image portfolio labeled “Cree beadwork and modern color tactics” provocatively juxtaposes intricate abstract beadwork designs with artworks by the likes of Piet Mondrian, Josef Albers, and Fernand Léger. The internet, Metchewais astutely observed, could be a site where one could collide modernist and Indigenous histories to sovereign visual ends. “Indians exist in impossible spaces,” he noted, “and [the web] has given us a purchase on the power of our space.”

In the composition Hymn over Water (2000), syllabics hover over the horizon line of Cold Lake, and above them is the phrase “Air: Vole au plus tôt” (Fly as soon as possible). The French phrase and syllabics are sourced from a Dene hymnal; the receding water, slightly out of focus, is sourced from one of the many trips Metchewais took back home. In this portrait of Cold Lake, there are no figures bathing in its waters, only the hymn, which hangs like a caption, an ode to the land. Language and the translation of word to image are central themes of Metchewais’s work, and here the French and Dene texts transition into the rhythmic pattern of the waves, an attempt by Metchewais, perhaps, to translate words into the omniscient language of the land.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

In early 2009, Metchewais posted an image of Self-portrait with Peach Brain Tumor to his online blog alongside a text addressing the return of symptoms from his brain tumor. “Now that it’s been confirmed with a brain scan that my brain tumor has changed its shape, I can stop playing games of self-denial. . . . Things move quickly now. My brain surgeon already called this morning to set up a consult this coming Tuesday morning. My main questions are these: Can I decide not to have surgery? And, if I opt out of surgery, what then happens? I noticed that I saw a prism rainbow on the wall and felt a little delight, which leads me to believe that my good spirit is still intact, not to mention my artistic vision.”

In July 2011, Metchewais passed away at his mother’s home in Alberta. The artist gifted his personal collection and archive to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, which finalized the accession in 2015. In addition to this legacy, traces of his presence remain online. The photographer and scholar Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie said shortly after the artist’s passing that “Kimowan’s creative spirit did not hesitate about living with death, and it was with a genuine thoughtfulness he has bequeathed his digital presence so that we may consider our own existence.” Metchewais’s final works move between digital, photographic, and earthly spaces, like the hymnal syllabics hovering between celestial and watery realms. In a July 2008 YouTube video diary, “tellytwoface returns from the rez,” Metchewais recounts a recent trip to Cold Lake following his recovery from surgery. He describes in near baptismal terms a full-bodied plunge into its cool waters, dipping his body as a kind of prayer. “To go in the water and come back out, and see that view. That’s good medicine. . . . I’m back and I feel full. I’m really full.”

This essay originally originally appeared in Kimowan Metchewais: A Kind of Prayer (Aperture, 2023).

October 3, 2025

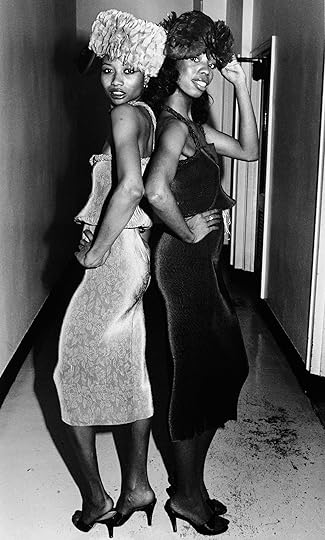

The Lives of Coreen Simpson

Coreen Simpson—photographer, writer, jeweler—has done it all.

Working for publications such as Essence, Unique New York, and The Village Voice, from the late 1970s onward, Simpson covered New York’s art and fashion scenes, producing portraits of a wide range of Black artists, literary figures, and celebrities. Her iconic jewelry, the Black Cameo, has been worn by everyone from the model Iman to civil-rights leader Rosa Parks.

The second title in Aperture’s Vision & Justice Book Series, created and coedited by Drs. Sarah Lewis, Leigh Raiford, and Deborah Willis, Coreen Simpson: A Monograph showcases the luminous, wide-ranging contributions of an essential artist. This long-awaited volume, Simpson’s first, features her celebrated B-Boys series—portraits of young people coming of age during the early years of hip-hop—as well as her experiments with collage and other formal interventions. An assortment of essays and an extended interview offer powerful reflections on Simpson’s unique blend of portraiture, sartorial politics, and her riveting story of an intrepid life in journalism, art, and fashion. Below, read a conversation from the volume between Simpson and Willis.

Coreen Simpson, Self-portrait, New York, 1970s

Coreen Simpson, Self-portrait, New York, 1970sDeborah Willis: Thank you for this opportunity to discuss your work for our Vision & Justice project as we remember the impact photography had on our lives as young girls until now. I recall us living as neighbors on the Upper West Side in the 1980s when we would run into each other going to events, shopping, and participating fully in the arts movements around New York. We always respected each other and our work.

I also remember the time we took our first trip together to Detroit, Michigan, for an exhibition I curated in 1982 with Dan Dawson, Photography: Image and Imagination, held at the Jazzonia Gallery. George N’Namdi and Rosalind Reed were the owners. It was a long road trip, but it was an exciting time as we began to reshape ideas about photography and its meaning to social justice, migration, and art. The photographers included Joan Byrd, Dawoud Bey, Albert Chong, Frank Stewart, Adger Cowans, Jules Allen, Bob Fletcher, and John Pinderhughes, naming only a few of the twenty artists. We were committed to bringing diverse stories to the exhibition. I remember with great fondness being inspired by your work because they were large-scale images of women, strikingly beautiful, and you painted on the photographs.

I also will never forget the time we spent on the 1989 artists’ trip that included David Avalos and Yong Soon Min, among many other artists, to Palestine, Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, and Gaza, particularly the difficult moments when the men didn’t understand our focus as women. Geno Rodriguez, then director of the Alternative Museum in New York, organized it with the invitation of Palestinian and Israeli artists. We visited these and other cities for the exhibition Occupation and Resistance: American Impressions of the Intifada, which was on display at the Alternative Museum, in 1990. Some of the people in the group challenged us because we took photographs of items and objects that were of interest to us: We focused our cameras on the land, interiors of homes, and I searched for Black Palestinians and children in hospitals. Some thought our work was apolitical because we were looking at the land in a totally different way. We saw Molotov cocktails on window ledges and photographed them.

Coreen Simpson: On that trip, we thought as mothers because we were also mothers. We saw how the Palestinian women lived under adversity and yet kept a home filled with color, and domesticity, despite lack of finances. This was truly inspiring.

Coreen Simpson, My Sister Is Dead, Palestine, 1989

Coreen Simpson, My Sister Is Dead, Palestine, 1989  Coreen Simpson, Egypt, 1989

Coreen Simpson, Egypt, 1989 Willis: In New York, we spent days and nights attending openings in the Village and on the West Side, and, of course, at Just Above Midtown gallery. The 1980s were, indeed, an exciting time, especially for Black artists. We were all together—photographers, painters, sculptors, writers, performance artists, musicians. Getting to know you affirmed my interest in imagining a biographical narrative in your portraits.

Simpson: That was a great time.

Willis: It was.

Simpson: We didn’t know that we were living in such a great time. We were just going with the flow.

Willis: It was normal. Everything was just love.

Simpson: That’s right.

Willis: You were recognized as a photographer and jewelry designer. If you agree that is the case, and I’m leaving it to you to decide if it is, what would you say has been your lifelong quest?

Simpson: I think my quest was to really be independent and just to do something that I would enjoy. I worked as an executive secretary. I always had good jobs. But I was tired of that. And I realized one day—Coreen, you’ve got to get a career, this is not working.

So, I interviewed myself: “Well, what do you like to do?” I was freelancing, writing little lifestyle articles for Unique NY and stuff like that. But I wanted to do something that I enjoyed doing, where I could be free to do what I wanted to do. That is my lifelong quest. I haven’t worked for anybody in many, many years. I can’t believe I pulled that off.

Willis: How did your interest in visual culture and photography begin?

Simpson: I was doing freelance writing, and I didn’t like the photographs that people were sending in or taking of my subjects. I just thought, My articles would look better if I could photograph the way I see my subjects. So when I told Vy Higginsen that I wanted to take my own pictures, she replied, “We didn’t know you took photographs.” I called up Walter Johnson, who became one of my mentors, and I said, “Show me how to use this 35mm camera.” He came over, loaned me a Canon 35mm, and showed me how to use the light meter inside the camera. That’s how I started, just like that. And then I liked taking pictures better than writing. To me, it was more interesting.

[image error] Coreen Simpson, Street Preacher, Harlem, 1979 Coreen Simpson, Think Positive, Harlem, 1980

Coreen Simpson, Think Positive, Harlem, 1980 Willis: Tell us more about Vy Higginsen.

Simpson: Vy Higginsen was a Broadway producer at this point. But she was a very well-known New York DJ on the radio, with Frankie Crocker on WBLS. And she had a magazine called Unique NY. I loved the magazine. It was a long vertical magazine, very thin, and it had little articles about the uniqueness of New York.

I called her up one day. I didn’t even know Vy at the time. I said, “I have an idea for an article.” Because I was dating a bartender at the time—he was an actor, a very handsome guy—I told her, “I’ve met a lot of bartenders. Why don’t you do an article about bartenders? I could do it. I could interview four bartenders for you.” So she said, “Oh, that sounds great. Can you make it three typewritten pages?” So that’s how I started writing for her. That’s when I decided I didn’t like the photographs. The next time they called me to do an article, I told them, “I want to take the pictures; I will do the article only if you use my photographs.” That’s how I got started.

Willis: Sounds like you created your first photographic assignment, do you agree?

Simpson: Yes. That taught me a lesson. Don’t wait for anyone to give you an assignment. Never wait. Just do what you want to do, then sell it. That’s what I’ve always done.

Willis: Did you continue writing?

Simpson: A little bit here and there. The Village Voice asked me to do little things.

Willis: But you did a lot of lifestyle and fashion stories?

Simpson: Style things and lifestyle pieces. I’m very curious about how people live.

Coreen Simpson, Untitled, 1979

Coreen Simpson, Untitled, 1979  Coreen Simpson, Cooking Is My Game (Lady Chef), Velma James, Hotel Roosevelt, New York, 1977

Coreen Simpson, Cooking Is My Game (Lady Chef), Velma James, Hotel Roosevelt, New York, 1977 Willis: But during that time, did the photography of the civil rights movement and the activists from the Black Arts movement change your perception of how you wanted to see Black people in print? Your portraits reveal identities that had not been seen.

Simpson: I just didn’t want to see Black people all downtrodden. I was very inspired by Richard Avedon when I saw his work, his fabulous work. He made a big impression on me. I said, I want to do this with Black people. Because that’s how I always saw my own people. I was raised in a foster home, two foster homes, but really there was the main one later on that raised us. I always saw Black people, my people, as heroic in many ways. The women that I met were fabulous, and I just always wanted to take pictures to show the beauty, the grace, the dignity. I always wanted to put that in my pictures.

Willis: You described in an interview recently that you sat on the stoop in Brooklyn when your mother combed your hair.

Simpson: Yes.

Willis: As if the stoop was your auditorium seating.

Simpson: It was like the theater. And it was up a little high. She would part my hair. And other neighbors would sit on the stoop in Brooklyn. As a young kid, I would see these fabulous people walking by, dressed so beautifully. I said, Oh, did I just see that? I saw a man one time in an orange suit. I mean, can you imagine?

Willis: You still remember that.

Simpson: I still remember that, and the swagger. I just wanted to capture it. But I didn’t know how because I knew nothing about photography. I have no pictures of myself as a baby, as a young kid, my brother and I—because we were in an orphanage and then in foster homes. So the camera was very important to me. I would love to see a picture of my parents, my biological parents. I have none. So the value of the photograph . . . I always think it’s so important, the document that you have. And I wish I had that.

Coreen Simpson, The Three Greats, James Van Der Zee (seated), Gordon Parks (left), and P. H. Polk (right), 1980

Coreen Simpson, The Three Greats, James Van Der Zee (seated), Gordon Parks (left), and P. H. Polk (right), 1980  Coreen Simpson, Grace Jones, 1980s, from the series Nitebirds/Nightlife

Coreen Simpson, Grace Jones, 1980s, from the series Nitebirds/Nightlife Willis: I love that story of thinking about how you viewed the world and your desire to document and change the visual experience of how Black people have been portrayed. What other photographers influenced you?

Simpson: Gordon Parks. James Van Der Zee, of course.

When I was studying at the Studio Museum, in Frank Stewart’s darkroom classes, he would always come to me and say, “Oh, have you seen this book?” He did it so casually. He planted the seed in me that we must study the history of what we’re doing. Then I learned about Baron de Meyer, and I loved the lighting techniques. Cartier-Bresson. All those I learned. And I started collecting my own books.

I have quite a big library of photobooks.

Willis: It’s amazing, because when I think of your work, I always connected it to Henri Cartier-Bresson.

Simpson: Capturing the moment!

Willis: Moments at night.

Simpson: Oh, I love it.

Willis: How to rethink joy and pleasure. It’s not just everyday night moments, but the way that you visualize how women dress. Can you talk about how you began to think about fashion and photography?

Simpson: Well, fashion has always been something I was interested in. I remember as a teenager, I worked for a camera store, never realizing one day I would be a photographer. I never had a really good wardrobe. So I saved my money and bought clothes for my junior year. No one really paid me any attention until I had these nice clothes that I saved for. I remember going out one day in my neighborhood, and I had a fake pink leather jacket on, and I just remember how people were looking at me. I thought, Oh, that’s powerful. Fashion is a powerful thing.

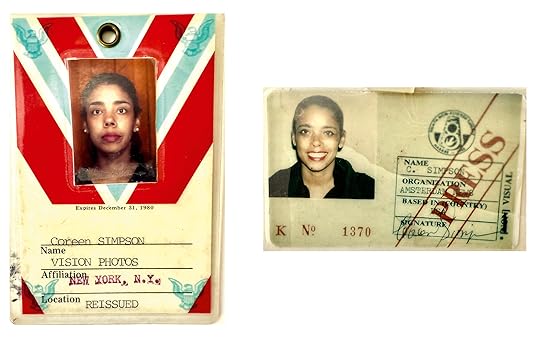

Left to right: Vision Photos press pass, 1980; Amsterdam News press pass, 1980s

Left to right: Vision Photos press pass, 1980; Amsterdam News press pass, 1980sWillis: What made you decide to take a class at the Studio Museum in Harlem?

Simpson: Because I was taking pictures, taking them to the lab, but I didn’t know how to develop my pictures. Frank was teaching that class in the late ’70s. Carrie Mae Weems was in my class. Isn’t that amazing?

Willis: In 1970, I took my first class at the Studio Museum in Harlem, and I studied with the filmmaker Randy Abbott. He led filmmaking and editing workshops there, and Toni Cade Bambara was one of the student-participants at Studio then. I wanted to make films. Studio Museum has been a core for many of us. Did you have any early exhibitions at the Studio Museum in Harlem during that time?

Simpson: I had a show there in the late 1970s with John Pinderhughes, a two-person show, Encounters. I remember showing at the Urban League’s Gallery 62. They gave me a one-woman show.

Willis: I remember that show and another exhibition Photographs: Coreen Simpson and Jacqueline LaVetta Patten (1980). The Urban League supported artists by hosting exhibitions in the lobby gallery.

Simpson: Yeah. So long ago. I had those big photographs up. I showed the Nitebirds/Nightlife because I liked a lot of night stuff, parties and stuff like that. I blew up pictures of the characters that I met at night.

Willis: Where did you go out then?

Simpson: All those clubs. I can’t even remember. The Mudd Club was one. Different little clubs. When I would go to the clubs, I would see a lot of different people and just click, click, click, click, you know.

Coreen Simpson, Man with Curl, 1990s, from the series B-Boys

Coreen Simpson, Man with Curl, 1990s, from the series B-Boys  Coreen Simpson, Helene, Roxy Club, 1985, from the series B-Boys

Coreen Simpson, Helene, Roxy Club, 1985, from the series B-Boys Willis: One of the points of your work is that directness of the gaze. People posing, wanting to be seen, and you see them!

Simpson: I always tell people to look right in the camera lens. Like when I did the B-Boys series in the 1980s, I would just pull people off to the side that I thought looked fabulous and put them into the studio that I set up. I always had to give them a little pep talk. I would say, “You look so fantastic and I want to photograph you,” then very briefly tell them what I’m trying to do, and have them sign releases. I would tell them that this is for posterity.

Willis: Why the title B-Boys? There are girls in there as well.

Simpson: Well, the girls came later. I was really focusing on the hip-hop scene, the breakdancers. That’s why I called them B-Boys. I saw a guy on the train. I gave him my card and said, “Come to my apartment,” because I wanted to photograph him. Richard. That was my first B-boy. Then he brought his friend with him, and he was gorgeous.

I showed the pictures to my daughter and asked, “Where do I find more?” She said, “Oh, go to the Roxy, Mommy, because that’s where they hang out—at the Roxy.” I went to the owner of the club and told him what I was trying to do. “I want to do this as a project. Would you help me do this as a project? Can I set up a studio here?” They went along with it. Everybody liked to be photographed. People go out at night, and they look great. They want to be documented.

Willis: You had the camera and the backdrop, and the studio was set up at the club?

Simpson: I had a big backdrop for the portraits that I did at the Roxy. The Roxy was huge. So they gave me a space, and I just put the backdrop up real quick, the lights and everything, the tripod and all that. But people like that attention. So I had no problem. And then a man came over to me one day, and he said, “These photographs are going to be very important one day.” He told me that. This was the early part of hip-hop, and I wasn’t really that interested in the music. I was more interested in the style. I like jazz.

Willis: I love how some of the kids use style from the ’50s in terms of dress.

Simpson: They had their own unique style.

Coreen Simpson, Ntozake Shange, 1997/2021, from the series Aboutface

Coreen Simpson, Ntozake Shange, 1997/2021, from the series Aboutface  Coreen Simpson, Alva with Clock, 1992/2021, from the series Aboutface

Coreen Simpson, Alva with Clock, 1992/2021, from the series Aboutface Willis: I see your portraits as stories. They’re storytelling in the most profound ways. It is fascinating that you moved toward enhancing your stories, from direct portraits to collage work. What led you to enhance the images?

Simpson: In the early 1990s, I wanted to do some new work, and I was looking at old photographs in my archives, just looking through things. Some were extras from test prints. They weren’t the prints that I really liked because it takes a while to get the print that you like when you’re printing in the darkroom. I had kept the test prints, and then I wondered, What am I going to do with them? So I began to fool around. At one time, I was doing actual collages. I got very caught up in it.

As a photographer, you want your own language. And it took me years to come to my own language. When I was fooling around with those test prints, little did I know I was creating my own language with the AboutFace series (1991–ongoing). I was just having a little fun. I think I wasn’t feeling so good at one time, maybe it was the wintertime, and I wanted to photograph, but I didn’t want to go out, or I couldn’t go out. So I said, Well, I’ll create a new body of work—I’ll do some collages with these test prints.

Willis: Did you look at Romare Bearden, at his collages as inspiration?

Simpson: Of course. But his were more stories. They were linear.

Coreen Simpson: A Monograph 65.00 The comprehensive survey of a singular, creative force who interweaves photography, design, and explorations of identity.

Coreen Simpson: A Monograph 65.00 The comprehensive survey of a singular, creative force who interweaves photography, design, and explorations of identity. $65.0011Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

Coreen Simpson: A MonographPhotographs by Coreen Simpson. Edited by Sarah Lewis, Leigh Raiford, and Deborah Willis. Text by Bridget R. Cooks, Awol Erizku, Doreen St. Félix, Rujeko Hockley, Sarah Lewis, Valerie Cassel Oliver, Jonathan Michael Square, and Salamishah Tillet. Interviewer Deborah Willis.

$ 65.00 –1+$65.0011Add to cart

View cart DescriptionThe second title in Aperture’s Vision & Justice Book Series, created and coedited by Drs. Sarah Lewis, Leigh Raiford, and Deborah Willis, showcases the luminous, wide-ranging contributions of an essential artist.

Coreen Simpson—photographer, writer, jeweler—has done it all. Working for publications such as Essence, Unique New York, and The Village Voice, from the late 1970s onward, Simpson covered New York’s art and fashion scenes, producing portraits of a wide range of Black artists, literary figures, and celebrities. Her iconic jewelry, the Black Cameo, has been worn by everyone from the model Iman to civil-rights leader Rosa Parks.

This long-awaited volume, Simpson’s first, features her celebrated B-Boys series—portraits of young people coming of age during the early years of hip-hop—as well as her experiments with collage and other formal interventions. An assortment of essays and an extended interview offer powerful reflections on Simpson’s unique blend of portraiture, sartorial politics, and her riveting story of an intrepid life in journalism, art, and fashion.

DetailsFormat: Hardback

Number of pages: 236

Number of images: 179

Publication date: 2025-10-14

Measurements: 8.5 x 10.75 x 1 inches

ISBN: 9781597115858