Aperture's Blog

November 14, 2025

Announcing the Winners of the 2025 PhotoBook Awards

Paris Photo and Aperture are pleased to announce the winners of the 2025 Paris Photo–Aperture PhotoBook Awards—an annual celebration of the photobook’s contributions to the evolving narrative of photography. A jury met in Paris on November 13, 2025, to select this year’s winners. The jury included Coralie Gauthier, director of programming, communications, and events, Librairie 7L; Shanay Jhaveri, head of visual arts, Barbican Centre; Manuel Krebs, designer and publisher, NORM; Emily LaBarge, contributing writer, The New York Times; and Guinevere Ras, curator, Nederlands Fotomuseum.

“Across the thirty-seven books that we had the incredible opportunity to spend time with and deliberate on, some things that surfaced were a sense of investigating the archive and intergenerational conversations,” says juror Shanay Jhaveri. “The shortlist and the winners show the vitality of the form of the book itself, one that is essential today in a culture where images have been dematerialized.”

This year, the Paris Photo–Aperture PhotoBook Awards received over one thousand books from fifty-five countries around the world, including standout entries from Ecuador, Lesotho, Uruguay, and Vietnam. Previously, on September 17–19, 2025, a shortlist jury, comprised of an international team, met in New York for three concentrated days of review and deliberation: Brendan Embser, senior editor, Aperture; Florian Koenigsberger, technologist and photographer; Paul Moakley, executive producer, The New Yorker; Anna Planas, artistic director, Paris Photo; and Keisha Scarville, artist.

Related Stories PhotoBook Awards A Look Inside the 2025 PhotoBook Awards Shortlist

PhotoBook Awards A Look Inside the 2025 PhotoBook Awards Shortlist A presentation of the thirty-seven books shortlisted for the 2025 PhotoBook Awards, including the winners, is currently on view at Paris Photo through November 16 and will travel to Printed Matter, New York, in January 2026, and then to the Leipzig Photobook Festival, with additional venues to be announced.

Below, read about this year’s winning titles.

Photography Catalog of the Year

Generalized Visual Resistance: Photobooks and Liberation Movements, Edited by Catarina Boieiro and Raquel Schefer

ATLAS, Lisbon, Design by Teo Furtado and Ana Schefer

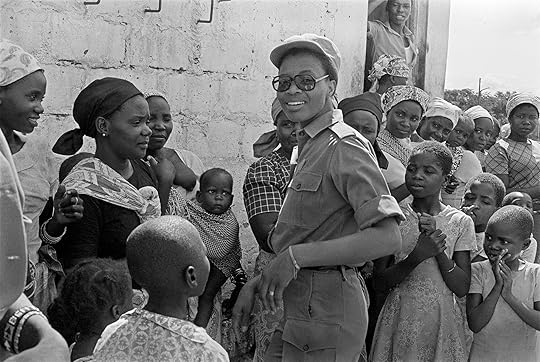

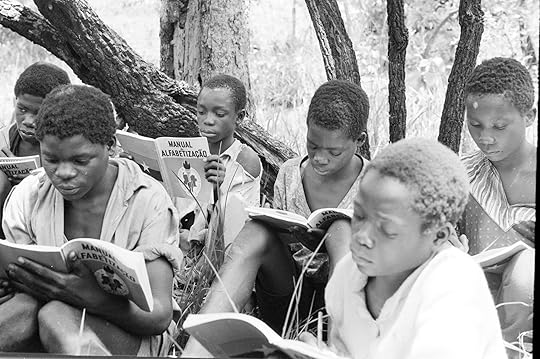

“The history of photobooks looks different from the vantage point of the African continent,” Drew Thompson writes in Generalized Visual Resistance: Photobooks and Liberation Movements, a vigorous anthology about the links between photography and anticolonial politics from the 1960s to the 1980s, when Portugal’s former colonies in Africa fought for independence. The product of a research initiative begun in 2018—with texts in English, French, and Portuguese—this book spotlights organizations such as the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (FRELIMO), which was instrumental in producing photobooks wielded by activists to inspire international solidarity. Covers and spreads from rare publications are reproduced throughout, displaying an immense range of visual communication strategies that often put a premium on dramatic, high-impact images, and showing how politically motivated publishers in Maputo, Mozambique, as well as Amsterdam, Moscow, San Francisco, and Tokyo, envisioned Africa’s freedom and self-determination.

Augusta Conchiglia, from Generalized Visual Resistance: Photobooks and Liberation Movements, 2025

Augusta Conchiglia, from Generalized Visual Resistance: Photobooks and Liberation Movements, 2025

First PhotoBook Award

A Study on Waitressing by Eleonora Agostini

Witty Books, Turin, Italy, Design by Massimiliano Pace

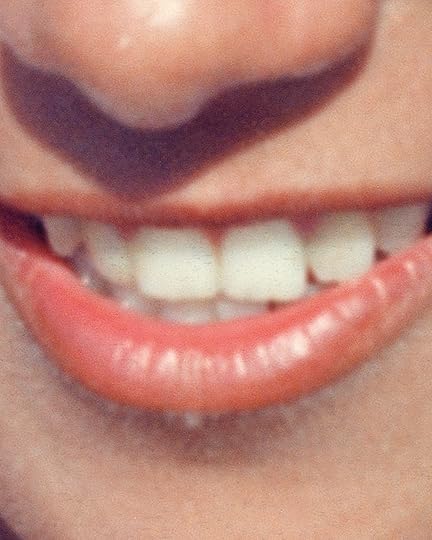

Eleonora Agostini’s A Study on Waitressing is a timely, multilayered interrogation of the roles that women are asked to play within the regime of self-presentation in the labor market. Agostini approaches this conceptual study by making fictionalized images of a waitress, played by her own mother. The book is divided into six chapters, each featuring a series of staccato-like sequences that layer upon one another ingeniously, narrowing in on mundane details of gesture, movement, and behavior. These visuals are mixed in with semitransparent pages to mark the transition between sections, featuring small, handwritten notes in her mother’s native Italian. Midway through a sequence of cropped close-ups of a woman’s smile, the book shifts to a manual-like text describing how a waitress is to appear, dress, speak, and maintain herself. The phrase “Always Smile While Speaking” is punctuated throughout—a stern reminder that the customer is always right.

Eleonora Agostini, from A Study on Waitressing, 2025

Eleonora Agostini, from A Study on Waitressing, 2025

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

PhotoBook of the Year

The Classroom by Hicham Benohoud

Loose Joints Publishing, Marseille, France / London, Design by Loose Joints Studio

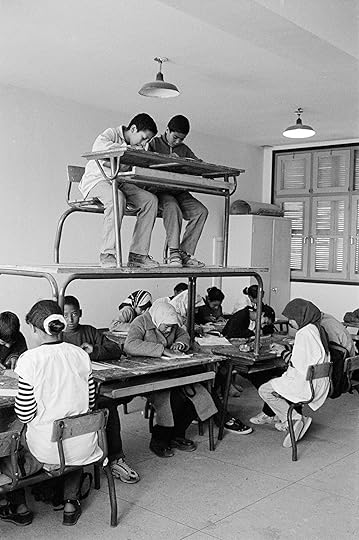

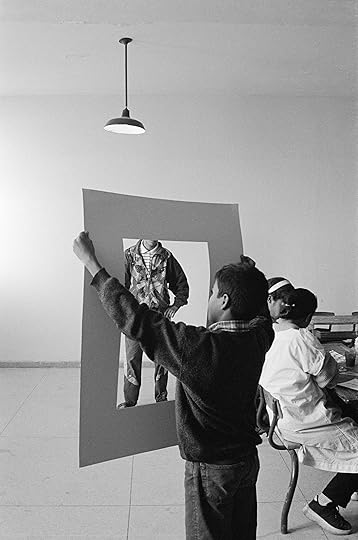

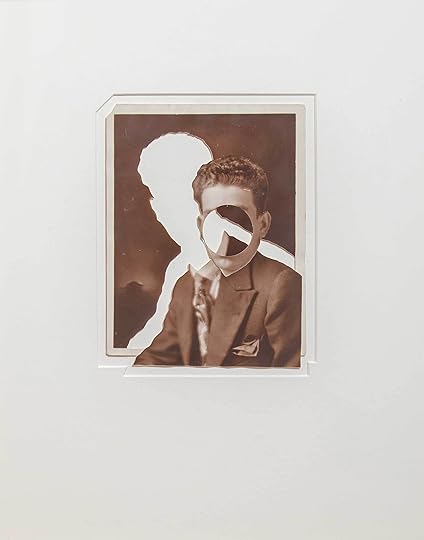

In the early 1990s, Hicham Benohoud was a jaded high school art teacher in Marrakech. Like his students, who came from underprivileged backgrounds, he felt trapped by the stultifyingly rigid power structures of postcolonial Morocco. So he started to improvise photoshoots to pass the time, transforming his four-hour class into a site of joyful photographic ingenuity and hands-on learning. Made between 1992 and 2002, the black-and-white photographs of The Classroom show Benohoud’s pupils posing against makeshift backdrops and behind paper cages, at desks stacked atop other desks, with Hula-Hoops and in surreal outfits crafted with long cardboard tubes or plastic bags, their faces often playfully obscured. “This book stopped me in my tracks,” says juror Florian Koenigsberger. “Above all, I’m attracted to the resourcefulness of the work. I think it’s a model for creativity in a lot of ways, of making the most of what you have. It offers a beautiful perspective on imagination.”

Hicham Benohoud, from The Classroom, 2025

Hicham Benohoud, from The Classroom, 2025

Jurors’ Special Mention

Flowers Drink the River by Pia-Paulina Guilmoth

STANLEY/BARKER, London, Design by ramel·luzoir

Under the moonlight, in the dark cover of the night, Pia-Paulina Guilmoth guides us into a nocturnal dreamscape that reveals the beauty and resilience born from transformation. Flowers Drink the River spans the first two years of Guilmoth’s gender transition, when she began photographing her community in rural Maine, exploring both the joy and terror of life as a trans woman in a small right-wing town. Using a large-format camera and a heavy flash, Guilmoth oscillates between the mystical and ominous, and each frame feels as if it’s a small moment captured mid-ritual, leaving us to imagine what transpires outside the frame. Spiderwebs and moths sparkle against darkness; mud-drenched bodies intertwine in fields; and landscapes shimmer with an almost ethereal haze. Flowers Drink the River blends Guilmoth’s mystical yet exacting view upon her own search for resistance, magic, and safety in a world often devoid of it.

Pia-Paulina Guilmoth, from Flowers Drink the River, 2025

Pia-Paulina Guilmoth, from Flowers Drink the River, 2025

An exhibition of 2025 PhotoBook Awards Shortlist will be on view at Paris Photo through November 16 and will travel to Printed Matter, New York, in January 2026.

Anastasia Samoylova Maps a Decaying American Dream

How to see America—in all its vast, messy contradictions, in a way that makes an argument, even a partial one—for what it is without smoothing over the simultaneous glory and pain that have structured the nation since its founding, not silencing any part of it, not allowing ourselves to maintain our comforting, myopic, partial views of our little slice of a much larger American pie?

If you were Berenice Abbott, say, or Robert Frank or Stephen Shore, you might go on a road trip—cut through the country, using roads that crisscross the land, sometimes in ways that replicate how Native Americans and early European colonizers traversed it—as a way of mapping the nearly unmappable: not just the space but the place, the sum of geography and politics and culture and economy and power and history that shapes it. For Abbott, it was a trip down US Route 1 from Fort Kent, Maine, to Key West, Florida, and back again, in 1954. Abbott made it with the hope of recording what she suspected would be imminently lost: namely, the small-town ways of life, and even the culture of larger cities, in the face of the expansion of the Interstate Highway System. For Frank, it was a tour across the country in 1955 and 1956 with the aim of recording every stratum in American society, where his outsider view—he was a Swiss immigrant—gave his pictures an air of critique, a refusal of romanticism and nostalgia. They registered disapproval, even, of the ways in which the harrowing class and racial disparities of American society were—and still are—papered over by the shiny optimism of the new that defines American consumer culture. And for Shore, it was a 1972 trip along Route 66 that turned into a photographic diary—“every meal I ate, every person I met, every bed I slept in, every toilet I used, every town I drove to”—shot not in black and white, but in color.

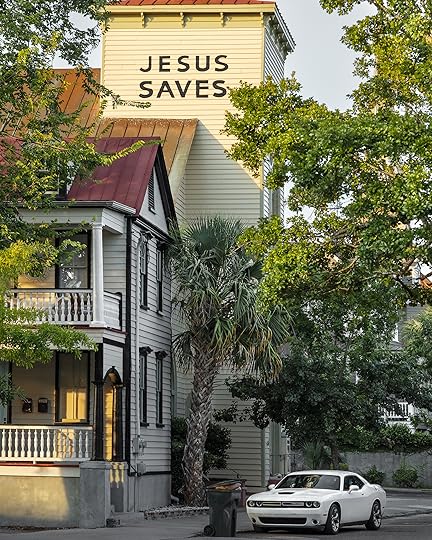

Anastasia Samoylova, Jesus Saves, Charleston, South Carolina, 2020

Anastasia Samoylova, Jesus Saves, Charleston, South Carolina, 2020  Anastasia Samoylova, Historic Reenactor, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 2024

Anastasia Samoylova, Historic Reenactor, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 2024 Like Frank, Anastasia Samoylova has an immigrant’s view of the United States, one conditioned by a life outside it. But in 2023, when she began roughly retracing Abbott’s route from the tip of Florida, her adopted state, to Maine, her status as an “outsider” documenting aspects of American life was conditioned, too, by the photographic history of the American road trip. It functioned as both an inspiration and a foil, the way, say, Walker Evans’s photographs in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941) functioned for Robert Frank’s The Americans (1958). To get in the car with a camera in hand now, not quite two hundred years since the invention of photography, is an act of looking outward, yet it’s also looking inward to the very terms of the medium and its past.

Samoylova notices these relics of the past without falling into the trap of nostalgia.

This self-referentiality shows up in the way the past bumps up against the present in Atlantic Coast. It is a comment on the way this country has never truly reckoned with the original sins of its founding—slavery and genocide above all—so that the past appears, like the return of the repressed, in many of Samoylova’s images. But it is also an engagement with photography’s development over time. One could point to Historic Reenactor, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, for example—a woman whose outfit looks to be out of the 1940s, pin curls and headscarf, white collar and jolly printed apron—behind the counter of an old-fashioned sweet shop. Samoylova doesn’t underline the artificiality of the scene or give us any means to recognize it as a fiction; there is no obvious “tell” to let us know that this isn’t a historical photograph, other than the title and the technical qualities of the photograph and print themselves. Samoylova takes up the documentary approach of someone like Abbott or Frank or even Evans; she takes up the challenge of the road trip with all its historical freight, but even more, she allows her subject to occupy a time closer to those forebears than her own.

Anastasia Samoylova, Reflection in Black Thunderbird, Palm Beach, Florida, 2024

Anastasia Samoylova, Reflection in Black Thunderbird, Palm Beach, Florida, 2024  Anastasia Samoylova, Two Cars, East Harlem, New York, 2024

Anastasia Samoylova, Two Cars, East Harlem, New York, 2024 Automobiles play a large role in this confusion of timelines. The massive, grumpy hog in Hog, Old Lyme, Connecticut, stands in the back of an old-timey pickup truck. A vintage blue Oldsmobile sedan looks out from a shed like garage in Brunswick, Georgia. A rusted-out jalopy is parked next to equally antiquated gas pumps at an abandoned Esso station near Lubec, Maine. (The levels of obsolescence here are myriad—the place is falling apart, and the company itself, long ago absorbed into ExxonMobil, no longer exists in the US.) Palm trees are reflected in the hood of a lovingly maintained Thunderbird in Palm Beach. An out-of-date hearse sits forlorn, “For Sale by Owner” sign in its windshield, near Orient, Maine. In East Harlem, Samoylova picks out two old cars parked nose to tail—Cutlasses, I think—whose colors (cream and copper brown) echo the depressing, small-windowed, low-income housing aesthetics of the brick apartment blocks behind them. Even in her photograph of a diner in Raleigh, North Carolina, the view is dominated by the pictures on the wall rather than the work going on in the kitchen, which is seen through a framed cutout on the lower left. Of those pictures, the most prominent is a painting of a man posing proudly by his 1950s-era blue truck.

Blue Corvette 1800.00 Collect this limited edition by Anastasia Samoylova, which retraces Berenice Abbott’s 1954 photographic journey along the Eastern Seaboard, documenting dislocation, loss, and a shifting American dream.

Blue Corvette 1800.00 Collect this limited edition by Anastasia Samoylova, which retraces Berenice Abbott’s 1954 photographic journey along the Eastern Seaboard, documenting dislocation, loss, and a shifting American dream. $1,800.0011Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

Blue CorvetteCollect this exclusive limited-edition print by Anastasia Samoylova.

$ 1800.00 –1+$1,800.0011Add to cart

View cart DescriptionIn Atlantic Coast, Anastasia Samoylova retraces Berenice Abbott’s 1954 photographic journey along the Eastern Seaboard, documenting dislocation, loss, and a shifting American dream.

Inspired by Abbott’s acute and poetic observations on life along US Route 1 and on the seventieth anniversary of her project, the Florida-based photographer ventures on her own journey to revisit those communities forever transformed by the interstate. In this photograph, Samoylova turns her eye to a medley of roadside Americana: the undulating American flag, the bald eagle, a powder-blue Corvette, and their eccentric juxtaposition. A nearly shadowless light lends the scene a timeless quality, one punctuated by a stark reminder of nostalgia’s bewildering allure. Details

Anastasia Samoylova

Blue Corvette

Archival pigment print

12 x 15 in.

Edition of 15

Signed and numbered by the artist

Anastasia Samoylova (born in Moscow, 1984) is a Miami-based photographer who explores the intersections of environmentalism, consumerism, politics, and the picturesque. Her work has been exhibited internationally, including at the Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, Florida; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Nasher Museum of Art, Durham, North Carolina; C/O Berlin; Victoria and Albert Museum, Dundee, Scotland; Fundación MAPFRE, Madrid and Barcelona; Amerikahaus Munich; George Eastman Museum, Rochester, New York; Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia; and Kunst Haus Wien, Vienna. She has published four critically acclaimed books: FloodZone (2019); Floridas (2022); Image Cities (2023), published in conjunction with her winning the inaugural KBr Photo Award; and Adaptation (2024).

It’s not that there weren’t lots of late-model cars to photograph—Samoylova’s eye was caught by them, too, but in fewer numbers. Rather, she seems to have been interested not in the relentless sameness of American consumer culture that she was inevitably confronted with during her travels (a feature that Ed Ruscha pushed to the extreme in his 1963 photobook Twentysix Gasoline Stations) but on the singular detail. She notices these relics of the past without falling into the trap of nostalgia. Yes, the repetition of old cars, old churches, old movie theaters, old houses throws us back to the 1950s. This is more or less the heyday of what we now imagine as Americana. But in Samoylova’s hands Americana is portrayed not so much as a golden age but as a ruin.

Anastasia Samoylova, Fifth-Generation Farmer, Garysburg, North Carolina, 2024

Anastasia Samoylova, Fifth-Generation Farmer, Garysburg, North Carolina, 2024  Anastasia Samoylova, House by Water, Lubec, Maine, 2024

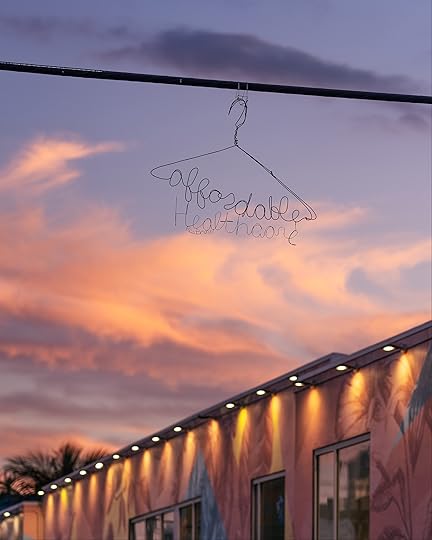

Anastasia Samoylova, House by Water, Lubec, Maine, 2024 Ruination is not simply the entropic erosion of the past but a condition of life in the present, according to the photographs in Atlantic Coast. Witness the collapsed Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore, a shocking failure of infrastructure that caused havoc for weeks in 2024 near the I-95 corridor (a successor to US Route 1), and among the most heavily trafficked interstates in the country. Or a wire clothes hanger that has been twisted to read “Affordable Healthcare,” dangling from a metal pole against a twilit sky in Miami. Or denim jeans drying on a fence in Fort Lauderdale, in a yard that has been flooded knee-high due to climate change. Or a leaflet taped to a pole near a marina in Bar Harbor, Maine, that reads: “LOOKING FOR WORK.” “Healthy, Hard Worker, Sober,” it continues. All of these are records of the insupportability of daily existence in the now.

Anastasia Samoylova, House Flag, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 2024

Anastasia Samoylova, House Flag, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 2024  Anastasia Samoylova, Sculpted Hanger, Miami, Florida, 2025

Anastasia Samoylova, Sculpted Hanger, Miami, Florida, 2025 We are living in a state of collapse. We also live among ghosts. We are haunted. A wall in West Palm Beach shows the barely visible remnants of decals that have been removed: “Sell New & Used Guns Ammo.” In Charleston, we see the removal of a statue of John C. Calhoun, vice president of the United States from 1825 to 1832, slaveholder, and ardent defender of the institution of slavery. A church spire in Savannah, viewed through an elevator window, is blurred, made inchoate, like an imperfect memory, by layers of dirt and peeling, weathered glass coating. If these are manifestations of history at large welling up in the present, there are moments when art history does, too, most strikingly in House Flag, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where a figure is partially obscured by an American flag and backlit, so that we see only their silhouette. The image is a subtle echo of one of the most famous images from Frank’s Americans in which two women watch an unseen parade from adjacent apartment windows, one of their faces obscured by a large flag floating across the facade.

Anastasia Samoylova, Ruin, Barboursville, Virginia, 2024

Anastasia Samoylova, Ruin, Barboursville, Virginia, 2024  Anastasia Samoylova, Civil War Reenactor, Fort Knox, Prospect, Maine, 2024

Anastasia Samoylova, Civil War Reenactor, Fort Knox, Prospect, Maine, 2024 I’ve emphasized the bleakness that Atlantic Coast portrays, and perhaps that is because of my own experience of this country as a person of color. I am uneasy, even low-key terrified, when I look at the stained glass window in a church in Pooler, Georgia. Three bomber planes roar above an angry—perhaps even vengeful—Jesus; a coat of arms for the 448th Bomb Group sits at the top of the composition, in tribute to its actions during World War II. Below the armorial, their motto reads “Destroy.” I feel the same sense of unease when I see a close-up of a woman’s hand resting on her woven American flag shawl. Her wrist is adorned with friendship bead bracelets, and her index finger sports a ring in the form of a rhinestone-encrusted gun. I feel it again when I meet the steely, suspicious gaze of the Civil War reenactor whom Samoylova encountered in Fort Knox, in Prospect, Maine. This is the America that I fear—the one that cannot let go of the idealization of war, whether wars of the past or an imagined war of enemies within. In the face of these encounters, unlike Frank’s, Samoylova’s point of view is not explicitly critical or judgmental—but ironically, this makes her pictures all the more troubling. While Frank took stealthy snapshots of people going about their business (showing us, in effect, what they were doing when they thought they weren’t being observed), Samoylova photographs people who are active participants in their self-presentation. They want to be seen this way.

Anastasia Samoylova, Woman in Pink Hat, Homestead, Florida, 2025

Anastasia Samoylova, Woman in Pink Hat, Homestead, Florida, 2025  Anastasia Samoylova, Fireworks, Fort Knox, Prospect, Maine, 2024

Anastasia Samoylova, Fireworks, Fort Knox, Prospect, Maine, 2024All photographs © the artist

But there is vividness too—reminders that life persists in the United States, that joy persists, that pleasure persists. An extravagantly flowering wisteria tree growing from inside an abandoned blue brick building in Baltimore, reaching out from a broken window. A young man, shirtless, soaking up the sun in front of the White House, and in another image, an older woman in a Barbie-pink Western getup—suede cowboy hat, satin shirt fringed with beads and sequins—doing the same in Homestead, Florida. And then there are two women, both Black, one in Darien, Georgia, and the other in Miami. The woman from Georgia looks up to the sky, eyes fringed by press-on lashes and a mouth in a wide smile as she shows off her utterly fabulous sweater with an appliquéd design of a nineteenth-century Japanese Ukiyo-e woodcut print. We see the Florida woman only from behind, as she poses in a sexy contrapposto, wearing a shimmering, formfitting dress cinched at the waist by a wide belt. The color here is sublime, equal parts heaven and hell: the crimson of her garment, the indigo of the shadows framing and defining her figure, the orangey yellows and teals and greens seen further afield, and over her shoulder, the deep darkness of silhouettes of fellow partiers; her Afro is like a halo. If so many of the images in Atlantic Coast make me painfully aware of the America I live in, these crucial few offer a picture of what America could be—a place that celebrates uniqueness, individuality, and the pursuit of happiness.

This essay originally appeared in Anastasia Samoylova: Atlantic Coast (Aperture, 2025).

November 7, 2025

Is Photography Yorgos Lanthimos’s True Calling?

Yorgos Lanthimos, the filmmaker known for stylized, pitch-black comedies rife with disfigurement, deadpan dialogue, and transgressive gamesmanship, is an acquired taste. Hollywood acquired it a few years ago, catapulting the Athenian from art house infamy to global celebrity with The Favourite (2018), followed by Poor Things (2023) and Kinds of Kindness (2024), and the newly released Bugonia (2025), all of which star Emma Stone (she insists that he’s her muse, not the other way around).

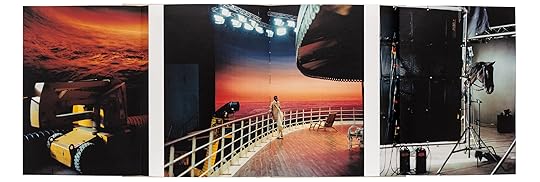

His experimental spirit undiminished by mainstream success, Lanthimos has recently branched out to a new venture: the photobook. Although the images in Dear God, the Parthenon is still broken (Void, 2024) and i shall sing these songs beautifully (MACK, 2024) were taken during the making of Poor Things and Kinds of Kindness, respectively, these books are far from simple behind-the-scenes companion volumes. Instead, they allude to their own narratives and worlds, hovering somewhere between photography and cinema. Below, the director talks about how these books came to be, and what might come next.

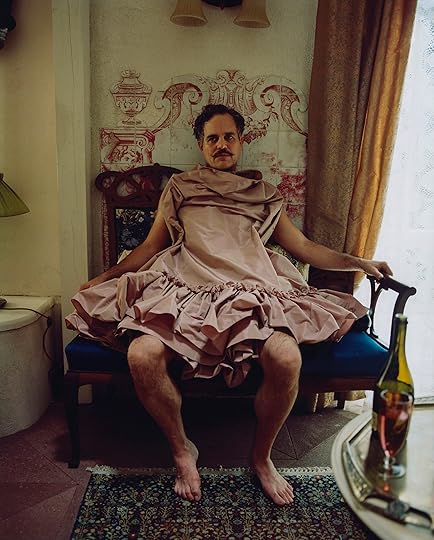

Yorgos Lanthimos, Untitled, from Dear God, the Parthenon is still broken (Void, 2024)

Yorgos Lanthimos, Untitled, from Dear God, the Parthenon is still broken (Void, 2024)© the artist

Yorgos Lanthimos, Untitled, from Dear God, the Parthenon is still broken (Void, 2024)

Yorgos Lanthimos, Untitled, from Dear God, the Parthenon is still broken (Void, 2024)© the artist

Zack Hatfield: When did your interest in still photography begin?

Yorgos Lanthimos: I went to film school when I was nineteen. I bought a camera and started taking pictures randomly, without any purpose. This was in the ’90s, before the internet. I was looking at Robert Frank, Diane Arbus, Stephen Shore, the classics. When I started making movies, I began taking pictures on set. I’m very shy when it comes to approaching or photographing people I don’t know, so this felt like a more normal, accessible thing to do. I’ve become more drawn to photography, in general, in the past few years. I even built my own darkroom next to my editing room, in Athens.

Hatfield: For years, you’ve enlisted the photographer Atsushi Nishijima to document the making of your films. But your own images are up to something else. They’re autonomous artworks, existing both inside and outside those cinematic worlds.

Lanthimos: The beautiful thing about photobooks is that they often allow for a story that’s not tied to the conventions of narrative. With Dear God, I didn’t want to make something that was in addition to Poor Things, but something that could stand on its own. Even more so with the second book. When I was making Kinds of Kindness, shot on location in New Orleans, it was already in my mind that I was taking pictures that weren’t necessarily related to the film. In the book, there are all these details that you’ll never get a sense of while watching the movie.

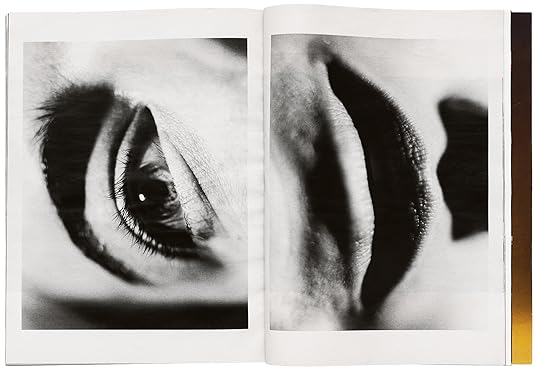

Interior spread of Yorgos Lanthimos, Dear God, the Parthenon is still broken (Void, 2024)

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }Hatfield: i shall sing these songs beautifully feels more classical, whereas Dear God makes use of double gatefolds, which often reveal evidence of artifice—rigs, scaffolding, boom stands, cycloramas.

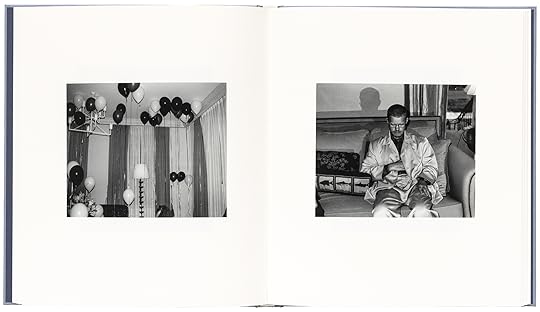

Lanthimos: I love how different the books are. Michael Mack hadn’t seen the Dear God book when we began the project, hadn’t seen a lot of my pictures. I showed him Dear God, and he said that the Kinds of Kindness book needs something different. The first book is a very complex, designed book. The second one includes way more black and white, a lot of flash. I wanted to make a more traditional photobook, in a more American tradition. And I wanted to create a narrative that has a more mysterious relationship to the pictures, that exists more in the gaps between pictures. At Michael’s suggestion, I added some of my own fragmentary texts. I would look at a photograph and let random thoughts, observations, and experiences take over. There’s one little text that is inspired by an R. D. Laing Knots type of style and structure. That’s a book I love.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Yorgos Lanthimos, Untitled, from Dear God, the Parthenon is still broken (Void, 2024)

Yorgos Lanthimos, Untitled, from Dear God, the Parthenon is still broken (Void, 2024)© the artist

Hatfield: Can you talk about the role collaboration played in creating the books?

Lanthimos: It was very liberating to work with these other people, Myrto Steirou and João Linneu of Void and then Michael at MACK. I relied on them because it’s not a process I’ve done before, sequencing a photobook. There is some overlap with how you edit a film with images, but it’s so much freer. It feels like there are fewer rules tied to conventional narrative.

Hatfield: How did the actors help you make these pictures?

Lanthimos: The experiences were quite different. Dear God was a very particular experience. We were in Hungary in huge film studios surrounded by sets. I used a large-format camera to make all those black-and-white photographs, and medium format to make the color portraits. Photography became a punctuation in between scenes. It was called “portrait time.” Whenever I had a few seconds between setups, I shouted, “Portrait time!” and brought out the large-format camera. Sometimes, Atsushi would see that I was frustrated with something that didn’t work while trying to film a scene and would suggest to me, “Portrait time?” I tried to do it really fast, which, of course, is counterintuitive with a large-format camera. At the same time, it was this little bit of frozen time within making a film and performing. It was a kind of game that we enjoyed.

Interior spread of W: The Art Issue (2023)

Interior spread of W: The Art Issue (2023)  Interior spread of Yorgos Lanthimos, i shall sing these songs beautifully (MACK, 2024)

Interior spread of Yorgos Lanthimos, i shall sing these songs beautifully (MACK, 2024) Hatfield: I read that Emma Stone helped you develop the photographs in the bathtub of a Budapest hotel.

Lanthimos: Emma got really interested in the process of loading film and processing the negatives, even though she has no interest in taking pictures. She likes the technical aspect of printing. She basically printed the black-and-white photos for a project we did for W magazine. I don’t know how we had the strength to do it—after a whole day of filming, twelve hours, going back to the hotel room, processing film and scanning it. But it really gave us strength. It helped us forget about the stress of filmmaking. You get the result of it immediately: “Look, we just processed this portrait that we got this morning, and we’re looking at it!” Or, “We fucked it up and scratched it, but it’s still beautiful.” It enriched our experience of making that film.

I take pride in having gotten a lot of people shooting film again. Jesse Plemons, who starred in Kinds of Kindness, has become an obsessive film photographer. Will Tracy, the writer on Bugonia, the new film we just shot, has taken up film photography. He goes out and takes night pictures with a tripod. I think my excitement about photography is a little contagious.

The beautiful thing about photobooks is that they often allow for a story that’s not tied to the conventions of narrative.

Hatfield: Are other artists’ photographs and photobooks important to your creative process? I noticed that Richard Misrach’s 1983 photograph Diving Board, Salton Sea, from his 1987 book, Desert Cantos, was cited in the credits for Kinds of Kindness.

Lanthimos: I have been moved over the years by many photographers. I think that in itself is a great influence, without necessarily being a visible, obvious one. I love the work of Sage Sohier, Mary Frey, Chris Killip, Rosalind Fox Solomon—her latest is a very powerful, moving masterpiece—Mark Steinmetz, Robert Adams, Lee Friedlander, Larry Sultan, Alec Soth, Gregory Halpern, Alessandra Sanguinetti, Masahisa Fukase. I can go on forever. I really loved Melinda Blauvelt’s book. Michael Mack introduced me to Lewis Baltz only recently. I was gifted an incredible book, Sex. Death. Transcendence. (2024) by Linda Troeller. Paul Graham’s a shimmer of possibility (2018). Whenever I look at it, I tear up.

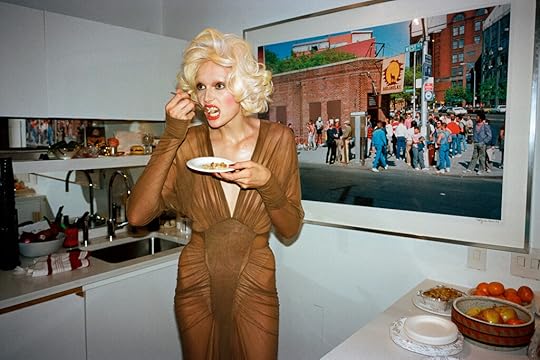

Yorgos Lanthimos, from i shall sing these songs beautifully (MACK, 2024)

Yorgos Lanthimos, from i shall sing these songs beautifully (MACK, 2024)Courtesy the artist and MACK

Yorgos Lanthimos, from i shall sing these songs beautifully (MACK, 2024)

Yorgos Lanthimos, from i shall sing these songs beautifully (MACK, 2024)Courtesy the artist and MACK

Hatfield: It’s hard to think of other photobooks that merge cinema and photography in such an open-ended way. Do you know about Annie on Camera?

Lanthimos: What’s that?

Hatfield: In 1982, John Huston invited nine photographers, including William Eggleston, Joel Meyerowitz, and Stephen Shore, to take images on the set of Annie. It’s great.

Lanthimos: I’m writing that down.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Hatfield: Do you consider a particular audience for your photobooks?

Lanthimos: Not really. I don’t think I could try to make something for an audience. You do something you want to make or see, and then you hope for the best.

Hatfield: Right now, you’re editing Bugonia, a sci-fi satire. Did you have another book in mind while filming it?

Lanthimos: I’m not sure. It’s a very contained film, so it might be harder to make a photography book that can feel independent from the film and strong in its own right. I’m trying to concentrate more on doing photography which is not film related. Lately, I’ve been taking landscape photographs in my travels around Greece, but also in Athens. I want to start taking more portraits but I need to ask people, so I’m very slow at it, procrastinating. Hopefully at one point I’ll make a book that’s not related at all to one of my films.

This interview originally appeared in Aperture No. 260, “The Seoul Issue,” in The PhotoBook Review.

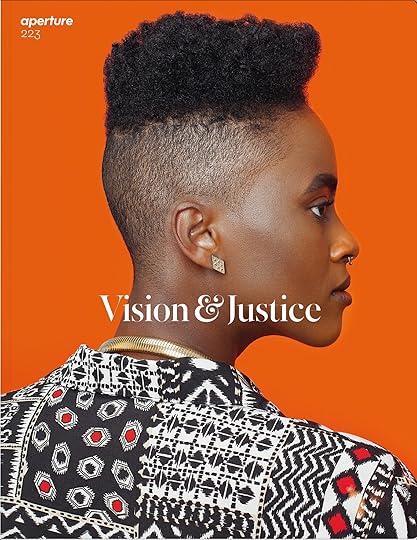

October 30, 2025

Aperture Celebrates 2025 Gala

On Wednesday, October 29, Aperture celebrated its 2025 Gala in the Appel Room of Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York City. The elegant annual benefit raised over $1 million, essential funding that sustains and advances Aperture’s established history of supporting artists and creating landmark publications. The joyful evening honored art and cultural historian Sarah Lewis, artist Tyler Mitchell, and Vision & Justice in recognition of their collective and dynamic impact on culture through their influential advocacy, art, and scholarship. Looking toward the year ahead, the benefit also toasted Aperture’s move to a permanent new home on the Upper West Side in 2026.

Aperture Board of Trustees with Tyler Mitchell and Sarah Lewis

Aperture Board of Trustees with Tyler Mitchell and Sarah LewisGala cochairs were Dr. Kathryn Beal, Dawoud Bey, Agnes Gund and Catherine Gund, Judy and Leonard Lauder, Jon Stryker and Slobodan Randjelović, Hank Willis Thomas, Olivia Walton, and Deborah Willis. To introduce the esteemed honorees, Deborah Willis saluted Tyler Mitchell, and Dr. Chelsea Clinton, Vice Chair of the Clinton Foundation, presented Sarah Lewis.

Complementing the inspiring program and the spirit of the venue, the Wynton Marsalis Quartet delighted guests with a surprise musical performance. A live auction expertly animated by Sarah Krueger, Head of Photographs at Phillips, featured prints by five major artists who have been central to Aperture’s past and present: Kwame Brathwaite, Lee Friedlander, Lyle Ashton Harris, Wendy Red Star, and Carrie Mae Weems. Additional funds were raised through bidding on two exclusive works of art: a limited-edition copy of Tyler Mitchell’s book Wish This Was Real (Aperture, 2025), bound with custom metallic covers and posters, and a specially commissioned photograph of Aperture’s new home at 380 Columbus Avenue by acclaimed photographer Gail Albert Halaban, known for her luminous images of cities at night.

Tyler Mitchell

Catherine Gund, Dawoud Bey, Sarah Lewis, Sarah Meister, Tyler Mitchell

Leigh Raiford, Sarah Lewis, Deborah Willis, Coreen Simpson, Michael Famighetti

Dr. Kathryn Beal, Tyler Mitchell, Sarah Meister, Yesim Philip

Mary Ellen Goeke, Cathy Kaplan, Thomas Schiff, Sarah Meister

Slobodan Randjelovic, Tyler Mitchell, Catherine Gund, Biljana Simic

Previous NextGuests were addressed by New York City Council Member Gale A. Brewer, with a rally of appreciation for Aperture’s work and excitement around the 2026 move to the Upper West Side. Joining the festivities were a host of artists who have collaborated with Aperture on publications and programs in support of their work over the years, including David Alekhuogie, Tina Barney, Dawoud Bey, McKayla Chandler, Awol Erizku, Ethan James Green, Lyle Ashton Harris, Balarama Heller, Rashid Johnson, Susan Meiselas, Anastasia Samoylova, Antwaun Sargent, Coreen Simpson, Ming Smith, Wendy Red Star, Alex Webb, Rebecca Norris Webb, and Deborah Willis.

Kellie McLaughlin, Judy Lauder, Bonnie Lautenberg, Sarah Meister

Kellie McLaughlin, Judy Lauder, Bonnie Lautenberg, Sarah Meister Dr. Bruce M. Halpryn, Chas Riebe

Dr. Bruce M. Halpryn, Chas Riebe Sarah Meister, Rashid Johnson, Sarah Lewis, Catherine Gund

Sarah Meister, Rashid Johnson, Sarah Lewis, Catherine Gund Michael Famighetti, David Alekhuogie, Coreen Simpson, Awol Erizku

Michael Famighetti, David Alekhuogie, Coreen Simpson, Awol Erizku Hank Willis Thomas, Deborah Willis

Hank Willis Thomas, Deborah Willis Gail Albert Halaban, Dr. Stephen W. Nicholas

Gail Albert Halaban, Dr. Stephen W. Nicholas Chelsea Clinton, Sarah Lewis

Chelsea Clinton, Sarah Lewis Helen Mitchell, Tyler Mitchell

Helen Mitchell, Tyler Mitchell Lisa Rosenblum, Allan Chapin, Nina Rosenblum

Lisa Rosenblum, Allan Chapin, Nina Rosenblum Katie Adams Schaeffer, Peter Barbur, Tim Doody, Stuart Cooper

Katie Adams Schaeffer, Peter Barbur, Tim Doody, Stuart CooperProceeds from the gala and auction sustain Aperture’s work as a nonprofit leader in the field of photography, including its award-winning publications, educational initiatives, touring exhibitions, and public programming. Aperture relies on contributions not only from the gala but also from dedicated readers and enthusiasts, and gratefully accepts donations of any amount through aperture.org/support.

Sarah Meister, Wynton Marsalis, Sarah Lewis, Tyler Mitchell, Ming Smith

Sarah Meister, Wynton Marsalis, Sarah Lewis, Tyler Mitchell, Ming Smith Pauline Vermare, Andrew Lewin, Kristen Lubben

Pauline Vermare, Andrew Lewin, Kristen Lubben Sarah Lewis

Sarah Lewis Tyler Mitchell, Anastasia Samoylova

Tyler Mitchell, Anastasia Samoylova Wynton Marsalis

Wynton Marsalis Wynton Marsalis

Wynton MarsalisAperture thanks all of the 2025 Gala supporters, including Aperture Legacy Stars: Thomas R. Schiff and Mary Ellen Goeke, Jon Stryker and Slobodan Randjelović, and Olivia Walton; Minor White Visionaries: Dr. Kathryn Beal, Agnes Gund and Catherine Gund, Dr. Bruce M. Halpryn and Chas Riebe, Judy and Leonard Lauder, Lisa Rosenblum and Georgina Celebic; Dorothea Lange Leaders: Peter Barbur and Tim Doody, Allan and Anna Chapin, Mark Gimbel and Dede Welles, Ingram Content Group, Elizabeth and William Kahane, Cathy M. Kaplan and Renwick D. Martin, Melissa and James O’Shaughnessy, and Yesim and Dusty Philip; and Ansel Adams Advocates: Bloomberg Philanthropies, S. B. Cooper and R. L. Besson, Terry Hermanson, Florian Koenigsberger, Leica Camera USA, Alice Walton, and Casey Weyand.

Thanks to those who made the live auction possible, including Phillips, along with the Kwame Brathwaite Archive, Fraenkel Gallery, Lyle Ashton Harris, Wendy Red Star and Sargent’s Daughters, and Carrie Mae Weems. The Self-Portrait Project installed a fun photo booth for guests in the reception. Images from the evening posted on BFA.com.

Related Items

Tyler Mitchell: Wish This Was Real

Shop Now[image error]

Tyler Mitchell: Wish This Was Real (Collectors’ Edition)

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture 223

Shop Now[image error]Daniel Arnold’s New Pleasure? Missing the Shot.

In the past three years, the photographer Daniel Arnold has lost a father, a grandfather, an uncle, a younger brother, and a cat. Arnold—who first garnered fame in the 2010s for New York street photographs that converge on moments of offbeat serendipity—entered Aperture’s offices in Chelsea wearing a threadbare hoodie, a film camera slung over one shoulder. It’s unsurprising, given his commitment to doing this interview only a few days after his uncle’s funeral, that our conversation touched on the metaphysical: questions on art, God, the Vatican.

Arnold isn’t shy to admit failure or shame. He wears as a badge of honor his lack of technical prowess when he first started photography. This was more than ten years ago, when he abruptly dropped his career as a writer to begin a quixotic quest of self-realization. In this way, the camera that has brought him recognition on the street can be seen as a talisman: the bijou in which he gathers evidence of the primordial, those fleeting instances in public life that speak to not only love or heartbreak, but also his own dogged searching.

On the eve of the publication of You Are What You Do (Loose Joints, 2025), I talked with Arnold about Sichuan peppercorns, authenticity, and his second monograph.

Freddy Martinez: You start your editorial photoshoots with playful icebreakers. I’d like to do the same. I read that you called Lee Friedlander a Sichuan peppercorn.

Daniel Arnold: Did I? That sounds like me. I back that. I don’t remember it, but I believe it, and I think it’s right.

Martinez: How does Friedlander’s work remind you of a Sichuan peppercorn?

Arnold: I do a lot of archive review, a lot of editing. It’s my nighttime activity. I’m such a junkie for pictures. And there are times when your mind gets deadened to what’s in front of you, especially when it’s your own output. There are times when I’ve been stumped and really over it, and I’ll flip through that big yellow MoMA retrospective of Friedlander’s, or it’s any Friedlander sequence, and I’ll experience that flavor-tripping phenomenon: When I go back to my work, it looks completely different to me. I can apply his brilliant formality to my own sloppy world and make new sense of it.

Martinez: Does that comparison ever feel troubling to you?

Arnold: You mean, does it make me feel insecure?

Martinez: Yes.

Arnold: If you’re going to struggle with insecurity, you’re probably in the wrong business. Insecurity is formative. It’s helpful, early on, but if I saw myself in competition with the rest of the photographers, I’d be cooked. I wouldn’t be able to go outside. There’s a tendency, especially in academia, to put everything in a lineage and see how moments in history speak to each other, how different voices compare. That’s for somebody else to do. For me, I deal with the world. I deal with my own little habit and keep it at that.

Martinez: You announced yourself in the early 2010s on Instagram. Looking back more than ten years ago, now at age forty-five, how would you describe your place in life right now?

Arnold: There was more ambitious ego at play in that first public push between 2012 and 2014. But I was very lucky to put a lot of that first desirous, ambitious energy into the writing chapter of my career. By the time photography presented itself to me, I had already moved past that New York thing of seeking glamour. I started photography in touch with the necessity to make a mess and fail. I didn’t even know how to use a camera properly then. I just knew I loved pictures. So I pointed the simplest camera that I could and crossed my fingers and made a lot of mistakes. But anyway, forty-five. Looking back, it has been an insanely consequential ten years. I think I’m now much more rooted in—not to be a downer—but in grief and alienation. There’s still heavy curiosity and clinging respect for naivety. I try to find that and cultivate it wherever I can. But now and then are different worlds. I definitely don’t work with the same energy that I used to, which is not to say that I’m tired. It’s just that my priorities have changed. My appetites have changed.

Martinez: You mentioned grief and naivety. It brings to mind vulnerability as an artist. What do you think about the idea of nakedness? This idea that a person may have no pretense. How do you think people reach that? How do you think people can—

Arnold: Aspire to nudity?

Martinez: [laughs] Yes.

Arnold: I think I operate from shame, and shame is obviously the number one enemy of nudity. But I aspire to it. What you call nakedness I find it in those glimpses, in flashes of insight. I find it through relentless practice.

Martinez: Is shame tied to the grief that you mentioned?

Arnold: Oh, for sure. Good eye. My father died last summer. And my clearest memory of his funeral is flopping on a joke I attempted to make in his eulogy. The joke was, “I’m really smart.” I have a weird, dry sense of humor that takes for granted that people are actually paying attention and thinking about everything I say, and everybody there just took it straight, like I was using my dad’s funeral as an opportunity to promote myself. Laugh, it’s fine. That’s the right response. But the possibility that somebody could think that I was celebrating myself so horrifies me—that this is the lone souvenir I take away from losing the great male lead of my life. All I can really remember is when I looked smug and embarrassed myself.

Martinez: I think it’s insightful to know that a photographer is not just their camera, not just their eye: There’s also heart. You said that the guiding light of finding photographs that “double as a proof of magic” no longer compels you. What is guiding you right now?

Arnold: That statement comes across more definitive than I meant it. Do you know Wings of Desire? That film’s depiction of magic—the angel with a notepad noticing when the wind blows up someone’s jacket or when someone is crying alone in a parking lot—that breeze that blows through your life is still a guiding light. I mean, if not guiding, at least one of the great pleasures.

What I was referring to when I said that was this feedback-driven appetite for knockout, punch-line pictures—ones with bold and direct communication. Those work great on Instagram, or at least, they did for me early on. I spent a lot of time, whether I meant to or not, oiling my gears for making those pictures. It just got to a point where even landing thirty-six of them felt kind of boring and contrived. It was like I was imitating myself.

Martinez: Driven by an algorithm in a feedback loop—did you feel like you were being used by a machine in a way?

Arnold: Not exactly. But I was definitely being corrupted by social media. I can’t say my departure was as calculated as it now feels. I mean, it was COVID and the George Floyd protests were raging, and I couldn’t stand to use any aspect of that moment to draw attention to myself or to advertise my cute little insights. It felt disgusting. I stepped away from Instagram and almost immediately had no idea how to get back. I had a week, maybe a day, of disoriented panic about that, but it was really liberating. Leaving definitely stirs up more insecurity than staying, because when you’re checking in with an audience you have this confidence about whether you’re getting it right or wrong. Now, it’s hard to tell if it’s good anymore, but I don’t think it matters. I’m not swinging for the fences. I’m trying to do that Wings of Desire ritual every day and just be open to noticing the breeze on my cheek.

Martinez: The writer Denis Johnson would describe it as seeing mystery wink at us. Photographers are pointing at something and saying, “Look this way. I want you to see this.”

Arnold: I think that’s the structure of the game. Any game you play by yourself, exhaustively, every day of your life, you get to have an impish relationship with it. Now, I take great pleasure in missing a great picture. Like if I had taken one big step to the right and lifted the camera a little higher, you would see that there was this great thing happening, but I shoot from the wrong spot, so it’s loaded with dramatic irony that only I feel. It’s like a puzzle box. There’s some pleasure in that, dumb pleasure probably. But how do I keep the game entertaining for myself? I mean, there’s still that very basic caveman thing, “Oh, look at that. That’s funny. That makes me sad.”

For better or for worse, I’ve tried to make myself a world where I can work without the disruptive noise of my brain, one in which I can be a servant of my instincts, and then I can bring intention and analysis back to work at night in the edit. I’ve talked for a long time about a Jekyll and Hyde relationship with the editor within me, and I stand by it. The guy who’s deciding what the pictures are is different than the guy who’s taking them.

Martinez: Would you say the editor is the driving force of your work ethic?

Arnold: I don’t think you can really separate the two. The edit work that I do at night is bringing reason to a mostly unconscious part of my brain. But I also learn about the daytime guy’s shortcomings, and I’m able to carry those lessons into the next day, like little Post-It reminders for my automatic brain, “Hey, maybe you need to get a little bit closer today, or maybe you should pay a little bit more attention to framing. Maybe don’t be so loose about shooting from your belly and having everything be way too far to the left.” It’s kind of self-contradictory now that I’m hearing myself say it out loud, but on one hand, the rigor enables this mindless kind of work, and on the other hand, it also infuses that mindlessness with a gut discipline.

Martinez: You’ve spoken about storytelling. Looking through your work, I imagined what folklore could look like in New York City.

Arnold: Music to my ears.

Martinez: There’s an idea that folklore is a slow, traditional type of narrative that forms over centuries. I think it’s also tied to moments when somebody shows us that the past is still present now. I was wondering what you think about folklore as it relates to your photography?

Arnold: The title You Are What You Do comes from one of the pictures. It’s written in yellow chalk on a red wall where some girls are playing hide-and-seek. It’s also a phrase from Carl Jung. I bought myself a particular edition of Joseph Campbell’s Hero with a Thousand Faces because, although Loose Joints has their hands on the reins of production, I wanted to make a bootleg T-shirt with the Thousand Faces cover, so that I could give it away on the side when they’re not looking. What do you do when you empower your unconsciousness to create a document of your emotional experience? It’s archetype, it’s all archetype, and when it comes to storytelling, I think that becomes observable and distinct in any street picture, no matter who’s making it. You see a cop, a kiss. There are all these things that are shortcuts, or signifiers, that if you just point your camera in that direction—even if you have no idea what else is going on—you dramatically increase the odds that a story is there.

I haven’t had this conversation before. Nobody has put it to me that way, but I aspire to folklore and that outsider, practical documentation. Sometimes I feel like a sculptor, like time is a procession of constantly changing surfaces that I peel off and stick on a cave wall to make my own extra peculiar, inverted world. There’s primordial energy. That’s why I try to work without ego or ambition. Aspiring to success just leads to homogeneity and imitation, and there’s something interesting there, for sure, but I don’t know. Maybe the most moving, thought-provoking art experience I ever had was going to the Vatican.

I don’t have any religious affiliation there, but it’s a masterpiece. The whole thing. Not just the Sistine Chapel, because the Sistine Chapel, you know who did it. For the rest of the place, so many nameless people who put their heart into work that they didn’t start and didn’t finish. It took generations of devotion. And the driving force of it all was—fingers crossed—the existence of “God,” you know, this screaming into the void: “Just in case you’re there, this is how much I love you.” Of that sentiment, I can’t imagine anything more worthy of my energy.

Martinez: That’s beautiful. I’m thinking of family now. Because like those artists who generation after generation say, “In case you can hear me, I love you,” our ancestors might say the same to their descendants—each generation, moving forward, doing its own small part, so that the next one can feel some connection to the past or love. Your father passed away, and you were close.

Arnold: Yes, and I just got home from a very close uncle’s funeral this past weekend, and my little brother before that and my grandpa and my beautiful cat. It’s been all in the past three years. I mean, whatever, this is not an era for, I don’t know, comparing tragedy. There’s so much. I just mean to say that I have some intimacy with death these days.

Martinez: Is that in any way a motivating factor for the book, or was it incidental?

Arnold: It’s there. You Are What You Do is an interesting marker of the moment. Because in my own rambling, messy way, I tried to articulate where I was with Loose Joints. I made them an edit of probably three thousand photos to show the scope of what’s there from my current point of view: Here’s my trajectory from those very crude photographs when I couldn’t use a camera to now trying to work without my brain noticing.

I told them that I had no interest in greatest hits, or “The wide world of Daniel Arnold.” I gave them a loose indication that I’m doing things differently lately, that different things are important to me. I mean, ideally, what I wanted to do was a Rosalind Fox Solomon–type book, where twenty years of puzzle pieces are decontextualized and rearranged to say something new, and I still like that idea, but that’s for me to do alone. And I think that Sarah Chaplin Espenon, who did the editing for the most part, saw that there was this more romantic, more wounded thing happening in my work that offered an alternative to what people usually think of me, and she stubbornly stuck to that as her thesis. She wanted another side.

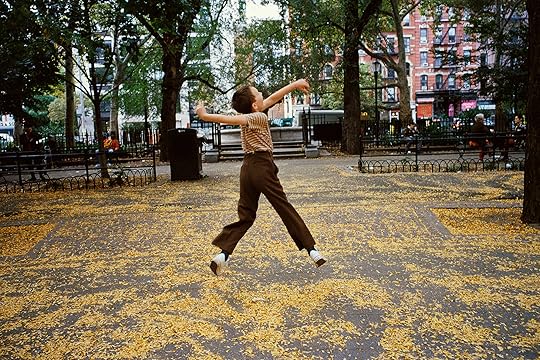

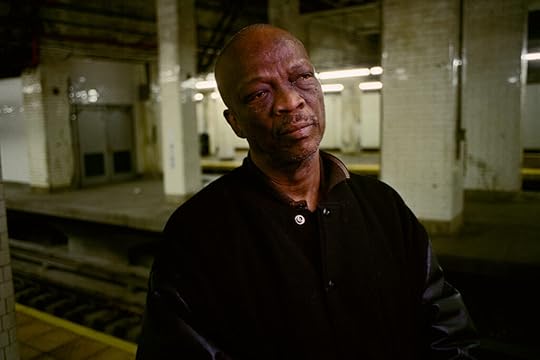

All photographs Daniel Arnold, Untitled, from You Are What You Do (Loose Joints, 2025)

All photographs Daniel Arnold, Untitled, from You Are What You Do (Loose Joints, 2025)© the artist and courtesy Loose Joints

Martinez: Do you have any feelings or intuitions for what lies ahead?

Arnold: I don’t, but I preordered Jeff Mermelstein’s What If Jeff Were a Butterfly? I have a new appreciation for that title after talking through this with you for a couple hours. I don’t really know Jeff at all, but I so admire his curiosity. What a free and special brain to have the insight, so many years deep in obsessive work, to say, What if I don’t even know what I am yet? I would hate to predict tomorrow because anything I guess will hem me in. I don’t want a goal. I think that life is scary and stressful, and we’re in hard times. I would love to stay loose and stay open and, more than anything, keep surprising myself. But what will come next? I have no idea.

Martinez: That’s okay.

Arnold: Yeah, it’s better that way.

What Is Gen Z’s Influence on Photography?

“There is no work of art in our age so attentively viewed as the portrait photograph of oneself, one’s closest friends and relatives, one’s beloved,” wrote the art historian Alfred Lichtwark in 1907. More than a century later, with the newfound ubiquity of the camera, Lichtwark’s prescience can be felt all around: the empty streets and cafés so tenderly photographed by Eugène Atget at that time are no longer empty in modern pictures. Today’s young photographers predominantly cite Cindy Sherman, dressed up as different characters in her eerie and melancholic self-portraits, as their greatest inspiration.

For twenty years, Photo Elysée in Lausanne, Switzerland, has sought to give a platform to young artists—and explore what defines their generation’s artistic output—first with the exhibition ReGeneration: 50 Photographers of Tomorrow in 2005 and, most recently, with Gen-Z: Shaping a New Gaze, which opened in September and brings together sixty-six image makers from around the world. Curators Nathalie Herschdorfer, Julie Dayer, and Hannah Pröbsting decided to shape the show in collaboration with the photographers, allowing each to include a statement that is showcased alongside their work. It was important, Pröbsting says, to create a show that includes the artists’ perspectives, rather than leaving them outside the process, which might have resulted in an anthropological approach. Instead, distinctive themes emerge from the photographers’ words as much as from their images.

What connects this group of emerging artists is their use of the camera as a tool for self-expression. Not much traditional documentary work is found on the walls; instead, interiority abounds. But this is not a study in myopia. Rather, the exhibition provides insight into how young artists are using photography to grapple with self-understanding and rebelling against the crushing weight of conformity imposed by various cultural norms and expectations. I recently spoke with artists Isabella Madrid (Colombia), Fatimazohra Serri (Morocco), Ben Hubert (United Kingdom), and exhibition curator Hannah Pröbsting to discuss this new generation of image makers, how growing up in a digital landscape has shaped their work, and their outspoken approach to identity.

Isabella Madrid, Self-portrait with Faja as Myself During My First Communion, 2024, from the series Buena, Bonita, y Barata

Isabella Madrid, Self-portrait with Faja as Myself During My First Communion, 2024, from the series Buena, Bonita, y Barata© the artist

Isabella Madrid, Self-portrait with Horse, 2024, from the series Buena, Bonita, y Barata

Isabella Madrid, Self-portrait with Horse, 2024, from the series Buena, Bonita, y Barata© the artist

Christina Cacouris: Self-portraiture was a predominant motif of the exhibition; the word identity came up a lot in the artistic statements. What role do you see identity playing within your work?

Isabella Madrid: Self-portraiture has been a tool since I was thirteen years old. It’s the window that allowed me to begin making art. It shaped how I understand my identity. It’s this combination of so many stories that are mine but also don’t only belong to me—this whole universe of Colombian women, how my mother’s identity has been shaped by her upbringing, my grandma’s, my friends’—how all of these stories come together. I take little pieces from everything and make the image and make my own identity. I think that plays into my relationship with social media and building these characters, storylines, plays where you have all these elements coming from so many different places.

Fatimazohra Serri: I grew up in a conservative community in Morocco. I was forced to wear a hijab at the age of fourteen. I grew up in that community not having my whole freedom, so photography was the thing that helped me to express myself, my struggles, and the women that were in the same community as me. I didn’t study art; I was an autodidact. I started with my phone at first. I tried to express my anger and my denial for my situation in pictures and turn them into a narrative that speaks for itself.

Ben Hubert: The project that I’ve been doing recently is an observation on social shifts. It’s still quite personal to me. Self-portraiture also just lends itself to the way that I work. I go into a studio without much of an idea of what I’m aiming to get out of it.

Hannah Pröbsting: I think that identity is always at the center of an awful lot of people’s work. What I think was really different about this generation of work was the strong number of artists in particular presenting their work as self-portraiture in a very performative way. There is this very performative nature of not just saying this work is about identity, but this work is a self portrait, and I am completely in control of how I am reappropriating something.

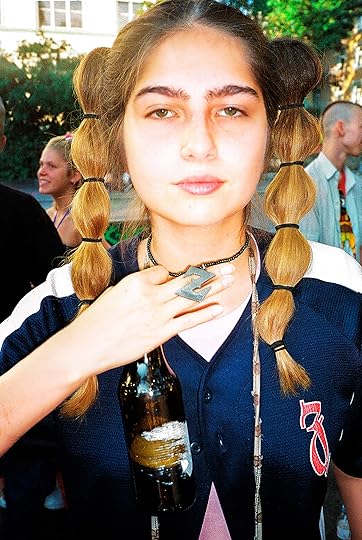

Ziyu Wang, Lads, from the series Go Get ‘Em Boys, 2022

Ziyu Wang, Lads, from the series Go Get ‘Em Boys, 2022© the artist

Cacouris: Building off the theme of performance, the concept of gender as a type of performance felt inherent in a lot of the work. How do you see gender in terms of a performance? How did you want to relate that in your work?

Madrid: In this project specifically, I was looking into what being a woman in Colombia meant. And that’s a whole universe that I had to really dissect and translate into visual codes and have a reading of gender in Colombia. It was very tied into how you look physically, what your body is supposed to look like, what your role in society is supposed to be, and tied into religion, into violence with your own body, subjecting your body to very violent procedures like plastic surgery.

Serri: As I mentioned before, my work is centered around women, especially in the conservative community. Ironically, when I wanted to work with males, I couldn’t; in my city, you can’t go into an apartment or somewhere with a man and do that. Someone would call the police. So I was limited to shooting on the roof of my house with my sister. Even when I wanted to talk about women and how they are oppressed, I couldn’t include men to express those things. I was even oppressed in speaking about these women.

This generation, they are not afraid of anything. They are more courageous, they are more bold, more creative.

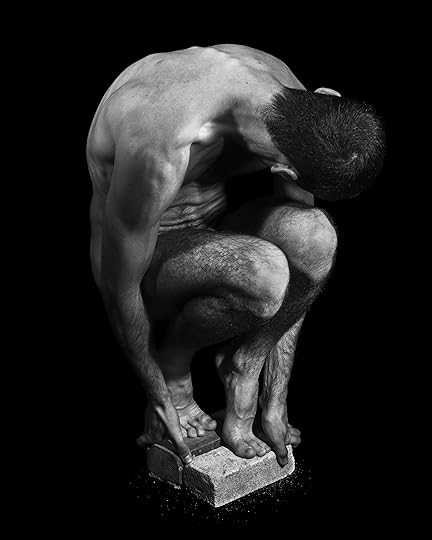

Hubert: Initially, there was some part of me that wanted to fight or at least push in the right direction for a general representation of men in terms of their ability to be vulnerable, to be comfortable and confident with what their sexualities are. The work took more of a quiet observatory approach on that subject, but within that, I was definitely using history in art as a way to try and tackle gender.

In a sense of sculptures of the male form throughout history—if you’re looking maybe at the Renaissance period or even ancient Greek—there’s this femininity and vulnerability that you see in some of these sculptures, and I’ve always found it interesting how idolized they are and how people look up to those. But in the present day, where I’m from, people have something against the idea of a naked man, predominantly straight men, that is probably homophobic. Photography for me was a way to bridge the gap between the male form within art and the actual male form, and find a space for it to exist comfortably.

Noah Noyan Wenzinger, from the series Noyan, 2015–22

Noah Noyan Wenzinger, from the series Noyan, 2015–22© the artist

River Claure, Yatiri, Puma-Punku, Bolivia, 2019, from the series Warawar Wawa (Son of The Stars), 2019–20

River Claure, Yatiri, Puma-Punku, Bolivia, 2019, from the series Warawar Wawa (Son of The Stars), 2019–20© the artist

Cacouris: How did your upbringings in a digital world impact your decisions to make photographs as an artistic practice?

Madrid: For me, there’s no photography without social media. Around eleven or twelve I started getting access to digital devices, and all I was doing was looking at images. I had already tried drawing, I had tried painting, but it never felt interesting because it was a kind of replication. And I think it was missing a subject, a person. I wanted a face, I wanted an expression, I wanted a character from the beginning. And I wanted to play into these social media websites, like Tumblr, where my visual collective was born. So it’s completely connected, and I’ve been sharing my self-portraits from when I was thirteen.

Serri: I was introduced to photography by friends. I had a lot of Moroccan friends who were doing photography online. I grabbed my phone, and I started shooting street photography for a few months just with my phone, and I was posting them on Instagram. Then I thought about experimenting in conceptual photography. And I didn’t think about it as art; I didn’t say I was doing something artistic. I was just posting on social media. Then people started liking my work. The algorithm was boosting pictures and art, so it reached a lot of people.

Ben Hubert, Untitled, 2024, from the series Plinthos

Ben Hubert, Untitled, 2024, from the series Plinthos© the aritst

Ben Hubert, Untitled, 2024, from the series Plinthos

Ben Hubert, Untitled, 2024, from the series Plinthos© the aritst

Cacouris: Something I found interesting in your work was the idea of the masks we wear. Ben, in one of your images you’re holding a plaster mask in front of your face; Isabella, you’ve painted your face in gold; and Fatimazohra, you’re concealing your face with the camera. I’d love to know more about the interplay between revealing yourself through self-portraiture and simultaneously obscuring a part of yourself.

Hubert: With a lot of the images that I’ve taken, I’m avoiding my face being in the work. I wanted a sense of it being about more than just myself, with the subjects that I’m tackling. Putting the mask into it, because it’s molded on my face, it empowered me slightly while also giving me a space personally within the project, which I don’t think otherwise would have been there. There’s something theatrical about it as well—the performance aspect—it feels like the old theater masks, in some ways. Also, a little bit like a death mask. The material has sculptural qualities, in a decaying way, and a level of that idea of the man crumbling.

Madrid: For me, it started with gold as a material because I wanted to think of different representations of Colombian bodies in history, and then my mind went to pre-Columbian Indigenous artifacts, and how we are known for these sculptures and masks made in gold, which were stolen through colonization. But it’s still a big part of our culture, this material and what it represents, also this shiny object to be commercialized—that was the starting point to turn it into this mask, this way of commercializing my own body, and then it became this drag thing. In each photo I wanted to have these drag characters, and that helped me understand what each mask was doing for each character. But it started with the material itself.

Serri: For me, it was for protection. As in most of my earliest works, you can see that the face is always hidden under the burka, or the camera, because back then I was only shooting myself, my sister, or some friends. I was living in Nador, and taking a picture of yourself and posting it online was a terrifying idea. My family had no idea I was doing that, and I couldn’t risk putting my friends’ faces online. It was a way to protect me, my sister, my friends, from the society, because the pictures were a bit controversial in my community. But since I moved from Nador—I’m in Marrakesh—I have more freedom to work with male, female models, I’m free to show faces. The situation has changed a lot, but back then it was for protection.

Fatimazohra Serri, L’origine du monde, 2018, from the series Shades of Black

Fatimazohra Serri, L’origine du monde, 2018, from the series Shades of Black © the artist

Cacouris: I understand. It makes sense why you were making pictures, and what it did for you, but why do you think your sister and friends wanted to participate? What do you think being photographed offered them?

Serri: I’ve never thought about it, but I think my sister did it because it was an exciting idea; maybe she wanted to support me. I assured them their faces were not going to be online, and they felt it was safe, but I appreciated that from them. Maybe because they wanted to do something new, something different. They believed in what I was doing.

Cacouris: I noticed that remote releases are prevalent in a lot of the work in the exhibition, including yours, Isabella. It almost feels like an anachronism to see them in photographs today. I’m curious why you decided to include it.

Madrid: I had always done digital photography, and I had also used a digital remote control. But I hid it. I was always trying to hide it and to contort my body so you wouldn’t see it. And then starting to study photography and studying photographers who actively reveal the device gave me another layer of understanding of what it means to build a self-portrait.

Pröbsting: So many of the projects that are in the exhibition are about reappropriating different things. Some are reappropriating words that have been used as slurs against them or reappropriating expectations that have been forced upon people. This is about saying, I am in complete control of this. No one is making me take this picture. I’m in this position. And this is me putting myself in this position to tell you something.

Fatimazohra Serri, Half Seen, Half Imagined, 2023, from the series Shades of Black

Fatimazohra Serri, Half Seen, Half Imagined, 2023, from the series Shades of Black© the artist

Cacouris: In response to the title of the exhibition, how would you each define the “new gaze” this generation is creating?

Madrid: It’s just so honest. I love the honesty and the rawness of it all. We’re not afraid to be greedy anymore. We’re not afraid of anything, really. Because the situation right now feels so hopeless, in a way, it’s like, we have nothing else to lose.

Hubert: Thinking about the future, there are so many common goals and topics being tackled across so many cultures and so many countries. The world’s never been as connected as it is now, online and in real life.

Serri: I agree with Isabella. This generation, I think they are not afraid of anything. They are more courageous, they are more bold, more creative.

Pröbsting: Photography has offered this generation a platform to speak for themselves, and maybe that comes from platforms like Instagram, maybe it comes from the fact that many, many young people even from an early age have a camera with them. But no longer are we relying on people from the outside to go in and represent different cultures, different communities, different voices. Through photography, this generation is able to advocate for themselves and have their own voice.

Gen Z: Shaping a New Gaze is on view at Photo Elysée, Lausanne, Switzerland, through January 2, 2026.

October 24, 2025

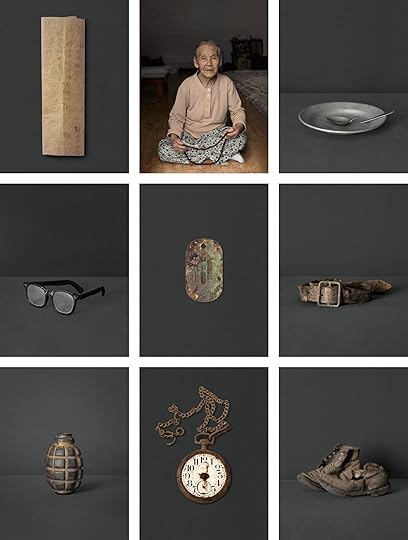

Korean History as Told Through Objects

An hour’s drive south of Seoul’s center, in Seongnam City, the photographer Bohnchang Koo occupies two small buildings resting on a verdant hillside. Designed by an architect friend twenty-five years ago, the airy buildings serve as Koo’s living space, studio, and home for a sprawling, eclectic collection. Ceramic vessels sit atop bookshelves, a decorative paper lantern in the shape of a lotus flower hangs from the ceiling, a rusted cash register proudly presents itself as an objet trouvé, and ancient wooden doors from the late Joseon dynasty enjoy a new life as window shutters. Under a vitrine is a recent acquisition: a thousand-year-old figure from Inner Mongolia, part human, part animal. “I could feel the touch of the craftsman who made it,” Koo tells me, recalling what attracted him to the curious form when he came across it at a local antique shop. His chockablock but orderly interiors have the feel of a well-selected antiques market—or the back room of a museum—and are the inevitable domain of an artist who chronicles how histories are revealed through talismanic objects.

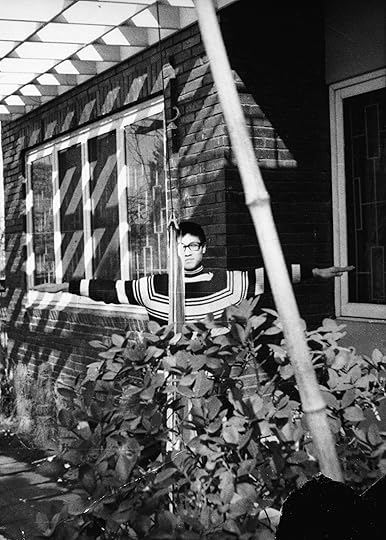

Bohnchang Koo, Self-portrait, 1968

Bohnchang Koo, Self-portrait, 1968Koo, a slim, gregarious man in his early seventies, traces his impulse to observe and collect to his childhood. The self-described shy one in a family of six children, his introversion drew him to become a diligent gleaner while growing up in Seoul, excavating shards of porcelain, pocketing peculiar rocks, pieces of colored paper, boxes, and other street detritus. He would assemble small collections of castaway treasure only to have his mother, concerned about space in the crowded family home, toss them into the trash bin. One acquisition, though, points to when his twin arts of collecting and photography first became intertwined. A 1964 brochure for the Tokyo Olympic Games—acquired by his father, who frequently traveled for his job in the textile industry—made an early impression about the allure of visual storytelling and, perhaps, Korea’s fraught relationship with its nearby island neighbor.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Although Koo studied business administration at Yonsei University, in Korea, he moved to Germany in 1979 to pursue art at the Hamburg Fachhochschule für Gestaltung (University of Applied Sciences for Design). He thought he might become a painter, maybe a graphic designer. A life as a photographer hadn’t yet occurred to him, nor had the idea that anyone might pursue this as an occupation. Even so, he picked up the camera and began capturing, in both color and black and white, the abstracted textures of European cities. His professors, in response, encouraged him to bring more of himself, his own background and subjectivity, into the work. When he returned to Seoul in 1985, having encountered the work of Joseph Beuys, Irving Penn, Josef Sudek, and others, he embarked on projects that rejected the then-dominant style of social documentary. He experimented with photograms, Polaroids, and photo collage, stitching images together into elaborate tactile patchworks that emphasized the physicality of images and their capacity for personal expression.

In 1988, he organized an exhibition at Seoul’s Walker Hill Art Center titled The New Wave of Photography, participating as one of the artists. “It was considered a decisive turning point in the history of Korean photography,” said Hee Jean Han, curator at the Photography Seoul Museum of Art, who recently organized a retrospective of Koo’s work and credits him with fostering experimentation in the Korean photography scene. “Amid the politically repressive 1980s under Korea’s military dictatorship and the rapidly transforming city of Seoul, Koo’s personal feelings of anxiety and alienation became a catalyst for his exploration of self and society. It was ultimately a journey that established him as a pioneer bridging photography and contemporary art in Korea,” Han explained. Although Koo only taught for around two years at Kaywon University of Art & Design, his expanded notion of photography would serve as a model for younger generations.

Bohnchang Koo’s studio, Seoul, 2025

Bohnchang Koo’s studio, Seoul, 2025  Bohnchang Koo, Yeouido Hangang Park, Seoul, ca. 1985

Bohnchang Koo, Yeouido Hangang Park, Seoul, ca. 1985 Koo’s penchant for formal experimentation, however, didn’t mark a complete abandonment of an observational way of working. He made a body of work on Seoul, rendered in saturated color, around the time of the 1988 Olympic Games. The city’s multibillion-dollar civic project saw the construction of new highways, subways, stadiums, and the cleanup of the Han River. This was an era also marked by political change and street protests, as the country evolved from dictatorship to democracy. Koo’s read of urban space in this transitional time, despite the punchy Ektachrome and Kodachrome colors, is melancholic. Six years abroad afforded critical distance. Missing the calm gray days in Germany, all he saw was color, sometimes in garish expressions. Picnickers find refuge on a solitary patch of green grass in an expanse of dirt; a family poses in front of the river with a partly constructed bridge in the background; pedestrians pass under a monolithic elevated highway; a rack of women’s shoes is left abandoned. The air of optimism is deflated by an undercurrent of uncertainty. Koo recalls this period in Seoul as one of change and chaos; it was not uncommon to hear tear gas being fired onto the streets somewhere off in the distance.

South Korea would chart a future of economic ascent, realized in the ubiquitous clusters of high-rises that today dominate Seoul’s skyline. As his city transformed into shimmering glass and steel, Koo began to look closely at what older surfaces transmitted, seeking trapdoors to the metaphysical in the everyday. A series on his terminally ill father, Breath (1995), a kind of memento mori, homes in on textures and details: his father’s leathery skin, a stopped pocket watch, a decaying bird—among inky images of nature suggestive of temporal ebb and flow.

Bohnchang Koo, Concrete Gwanghwamun 01, 2010

Bohnchang Koo, Concrete Gwanghwamun 01, 2010  Bohnchang Koo, Horse Riding Kkokdu 02, 1998, from the collection of the Ockrang Cultural Foundation, Seoul