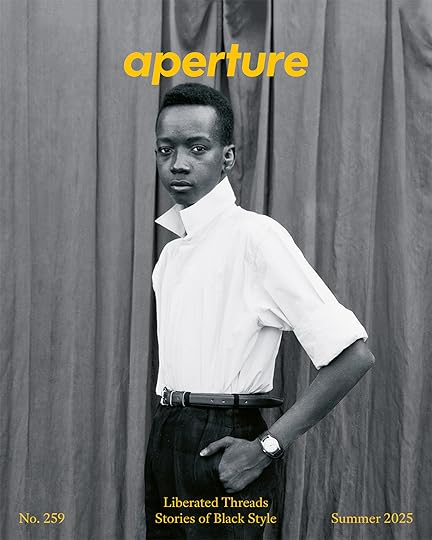

Aperture's Blog, page 6

June 26, 2025

Richard Avedon’s Rugged American West Comes to Paris

By the late 1970s, Richard Avedon was known as the preeminent fashion photographer, the master whose pictures appeared on almost every single cover of Vogue, who brought Brooke Shields into the limelight, who captured a normally shimmery and ebullient Marilyn Monroe looking unusually forlorn, and whose technicolor photos of the Beatles for Look Magazine were tacked on the walls of thousands of teenage girls’ bedrooms.

Yet it was a photograph of a different nature that caught the eye of Mitchell A. Wilder, the founding director of the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas: a modest portrait Avedon made of a ranch hand in Montana in 1978. Wilder called Avedon and proposed that, with the museum’s assistance, Avedon continue photographing the people of the West, culminating in an exhibition. It was perhaps shocking to some, when the resultant exhibition and book In the American West appeared in 1985, that a glamorous New Yorker would take on such a rugged project, and critics were disdainful of what they perceived as an improper portrait of America. “This is not the vanishing West, all perfumed and riding into the sunset,” a Los Angeles Times critic wrote of the show’s opening. “It’s the unsavory West that’s with us.”

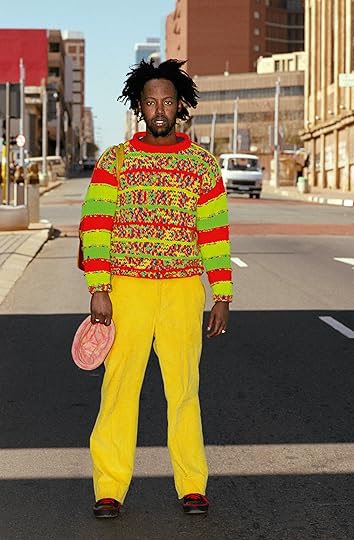

Installation view of Richard Avedon: In the American West, Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, 2025

Installation view of Richard Avedon: In the American West, Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, 2025On the fortieth anniversary of the exhibition, Abrams is reissuing the publication, and the Fondation Cartier-Bresson in Paris is displaying all 110 of the original images from the book, in a presentation curated by Clément Chéroux. The portraits from In the American West may not be romantic images—no pomp and circumstance—but they are dignified. Coal miners, cotton farmers, and cowboys stand tall and proud. Avedon worked quickly, street-casting his subjects alongside his assistant Laura Wilson, setting up white paper backdrops and shooting instinctively. Post-production was another matter entirely: Chéroux’s exhibition showcases the meticulous care that went into each print, with Avedon’s instructions for dodging and burning scrawled across pictures. I recently sat down with Chéroux to discuss the enduring legacy of Avedon’s West, and its documentary value.

Richard Avedon, Ronald Fischer, beekeeper, Davis, California, May 9, 1981

Richard Avedon, Ronald Fischer, beekeeper, Davis, California, May 9, 1981Christina Cacouris: In the opening to In the American West, Richard Avedon wrote that all photographs are accurate, but none of them are the truth. I was trying to parse if he means that photography generally is just a simulacrum of reality; if there is no such thing as true documentary photography. As the Director of the Cartier-Bresson Foundation, how do you interpret that statement?

Clément Chéroux: I think that every photograph has documentary value even if it’s a photograph that was set up and that was made as a work of fiction, and this is exactly what Avedon was interested in doing. When the show opened in 1985, he started a few interviews by saying this is a fiction, there is no more truth in my photographs than in the Western films of John Wayne. Most of these photographs were made with the desire to make a statement about the United States in the beginning of the 1980s. But Avedon was clear about the fact that the photographs were not necessarily the truth; they were an interpretation from his point of view about America at that time. It still has a documentary value, but I don’t think that he ever thought of this project as representing the truth of the United States.

The subjective part of the project is clear. And most of the photographs were from encounters where he photographed people he met as they were. He also stated very clearly that a few photographs were set up, and the photograph of the Bee Man is a good example of that. He first published an advertisement in the American Bee Journal to find the type of person he was interested in—we have the advertisement in the exhibition, we found the original magazine where it was published. So, he looked for that person and made some drawings in preparation for the shoot. He clearly had a dream of a specific image that he wanted to realize. And he made clear that he wanted to have this photograph to show the subjective part of the project, that it was not exclusively a documentary project. I think the Bee Man shows us that there isn’t truth on one side and fiction on the other. It’s much more complex.

Richard Avedon, Jesse Kleinsasser, pig man, Hutterite colony, Harlowton, Montana, June 23, 1983

Richard Avedon, Jesse Kleinsasser, pig man, Hutterite colony, Harlowton, Montana, June 23, 1983  Richard Avedon, Boyd Fortin, thirteen year old rattlesnake skinner, Sweetwater, Texas, March 10, 1979

Richard Avedon, Boyd Fortin, thirteen year old rattlesnake skinner, Sweetwater, Texas, March 10, 1979 Cacouris: I love that you get to see so much of the behind the scenes in the way that you’ve staged this exhibition, especially with the bee photograph. It was also really valuable to see all these preparatory Polaroids; there were quite a few where people were smiling and excited, but you don’t really feel that sentiment within the final images, which goes back to what you’re saying about how he had a very specific image in mind when shooting. Why was it important to you to show all of the preparation?

Chéroux: Two reasons; the first one is that I was interested in reminding visitors to the exhibition that there is someone behind each photograph. And by introducing some letters, some Polaroids, it was a good way to remind the visitors that a human being is behind all of these. But it can easily become very anecdotal to have all these stories behind each image, so I tried to find a way to give some information but not have it systematically throughout the exhibition. I was also interested in helping the public to understand the work that goes into each photograph and the way that Avedon was transforming someone he was encountering into a subject. If you compare some of these Polaroids with the final results, you can clearly see that there is a lot of work behind the image: it’s not only the photographic skill, it’s not only the white background, the light, the framing, the composition of the image, it’s also something that happened during the shoot.

We have some testimonies about the way that Avedon was working, and we know that he was not behind his camera, he was standing next to it. He had a strong connection with his subjects, mimicking their position, and asking them to respond to a very small gesture by showing himself moving in one direction or another, and I think a lot of the work is in this relationship that he was establishing with the subject. Photographic literature usually focuses on the framing, the composition, but for me, this kind of interaction he was able to develop with the subject is where the work is, where he’s transforming the people that he met into a Richard Avedon photograph.

Richard Avedon, Roger Tims, Jim Duncan, Leonard Markley and Don Belak, coal miners, Reliance, Wyoming, August 29, 1979

Richard Avedon, Roger Tims, Jim Duncan, Leonard Markley and Don Belak, coal miners, Reliance, Wyoming, August 29, 1979Cacouris: In the foreword to the book, he is very clear about what type of camera he uses, the exact size of the paper that he’s using, how he photographed in shade or natural light and how he achieved the final pictures. But even armed with that knowledge, nobody would be able to recreate any of this work because there’s something ineffable about the way that he related to people and the way that created these images. Do you recall the first time you encountered In the American West?

Chéroux: I first looked at the book in the 1990s, and I was very impressed by the development of the whole project. So, when I was developing this exhibition, I was interested in showing the entire group of photographs, not only the icons. I was also interested in showing the reference set that he had been using for printing the book. When we were working on preparing the exhibition, I tried different things; I tried to have a different kind of organization of the whole group of photographs, and of course it didn’t work at all. After a few hours of working, it was clear that we had to respect the layout of the book, and so we chose very quickly to start with the first image of the book and to end with the last image. We found a way to respect the rhythm of the book—when there is a white page, there is a space on the wall equivalent to the size of a frame. If you step back and have a look at the wall, you clearly see that he and Marvin Israel had been working on the layout very carefully and that they are playing with rhythm, with the size of the body in the frame, with the tonality of the image. Just before the Bee Man, we have the coal miners, these very strong dark images and then suddenly you have the white body of Ronald Fisher with all these little bees. We wanted to respect this in the exhibition, the sense that it was not just a collection of twentieth-century photographs of Americans, but it was a group of images, a full sentence.

Richard Avedon, Petra Alvarado, factory worker, on her birthday, El Paso, Texas, April 22, 1982

Richard Avedon, Petra Alvarado, factory worker, on her birthday, El Paso, Texas, April 22, 1982  Richard Avedon, David Beason, shipping clerk, Denver, Colorado, July 25, 1981

Richard Avedon, David Beason, shipping clerk, Denver, Colorado, July 25, 1981 Cacouris: You mentioned that he knew that the work would be a bit divisive and that that may have been part of the intention. I was reading a New York Times review from 1985, where they compared his work to what Ansel Adams had done in the West, showing it as this majestic landscape versus the way that Avedon has depicted it, what they described as hell broken open.

Chéroux: The response at the time was quite critical. It’s clear that it did not correspond to the idea that a lot of Americans had of their country at the time. In the ’80s, shows like Dallas or Dynasty were on TV showing an America with a lot of success and money, and Richard Avedon clearly chose to show the other side of that. When the project was launched, a lot of journalists assumed that Avedon was fed up with the elite or was bored of photographing beautiful people, but I truly believe that it was not the case. If you look at the development of Avedon’s career, you can clearly see that he was interested in making a statement about the social and political climate of the US, like his project with James Baldwin in the ’60s about the civil rights movement.

I believe that his interest here was not about just showing the dark side of America. He was much more interested in making a statement in a moment that was a very difficult moment for America, after all these oil crises from the ’70’s, the free market capitalism of the Reagan government, there was a lot of deindustrialization, people losing their jobs and going under the poverty line. The first image in the book is an unemployed person. It was a political statement from Richard Avedon. And of course, this was not well received. It was heavily criticized, especially coming from someone who was one of the highest paid photographers of the time. A few critics were also saying that he was exploiting his subjects, which is not true; he was paying them. He was not just stealing an image. He was really spending time with his subjects, having conversation with them, not just taking a photograph and leaving. He tried to help some of them. He really had a relationship with the people that he was photographing.

Richard Avedon, Ruby Mercer, publicist, Frontier Days, Cheyenne, Wyoming, July 31, 1982

Richard Avedon, Ruby Mercer, publicist, Frontier Days, Cheyenne, Wyoming, July 31, 1982All photographs © The Richard Avedon Foundation

Cacouris: When I was looking through the show and through the book, one of the images that really stuck with me most is a woman from a mental hospital; her hand is moving and it’s, I think, the only image where there is a blur. And that one really struck me. There was something so powerful, and seeing the way that she’s looking outside of the camera, and there was something poignant captured in it. I’m curious if there are any images in particular that stick with you more than others or ones that have especially gripped you.

Chéroux: Every time I look at the book I find something new; this is part of the pleasure of curating such a project. You establish a strong relationship with some of these images. You discover some new details. So, I hope visitors will go beyond the famous photographs and have encounters like Avedon had during his journey through the West. There’s an amazing photograph of Juan Patricio Lobato, a carnie. We are exhibiting a letter that we found in the Avedon Foundation archives from a woman who clearly fell in love with Juan from seeing him in the book. The letter is amazing: she writes, “I bought your book, I saw this photograph, and this is something that happens only once in a lifetime, that you meet someone.” But she’s not asking to meet with the guy. She’s not asking for his address. She is asking for other photographs. She wants more. She’s trying to explain what she felt in front of that photograph; there was clearly an encounter between a viewer and the subject of a photograph. That letter shows the power of photography. I truly hope that people will make more encounters like this one.

Richard Avedon: In the American West is on view at the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris, through October 12, 2025.

June 25, 2025

The Brilliant Light of California’s Beaches

In 1975, the thirty-five-year-old photographer Tod Papageorge took a cross-country trip that ended on the beaches of Los Angeles. There, challenged by the play of the brilliant light on skin, swimsuits, sand, water, and surfboards, he experimented with the descriptive qualities of the medium-format camera he brought with him. Employing a machine that produced a negative four times larger than his usual Leicas, Papageorge aimed to create poetry from the details of the physical world. Over the years, he returned to those beaches, and several others along the coast, three more times. Now, fifty years later, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Connecticut is presenting an exhibition of these images, previously shown on the West Coast at James Danziger Gallery and in Europe at Thomas Zander Galerie, and published as a book in 2023.

Papageorge began taking photographs during his final semester at the University of New Hampshire. In a basic technical class, he saw a few early pictures by Henri Cartier-Bresson, which struck him as the visual equivalent of the poetry he was studying and attempting to write. Observing how the French photographer created pictures à la sauvette changed the course of his life. Following graduation, and a year each in San Francisco and Boston, he set out for Europe and cities like Seville and Paris, where Cartier-Bresson also had made much of his early work. On his return to the states, in late 1965, Papageorge moved to New York, and soon became part of a group of photographers—including his boyhood friend Paul McDonough, as well as Joel Meyerowitz, and Garry Winogrand—that met regularly to photograph together, and, for one extraordinary period, convened in a weekly salon at Winogrand’s apartment, where they would look at work and discuss their shared passion.

Papageorge, a distinguished teacher, was himself schooled in the streets, sidewalks, parks, and nightclubs of Manhattan, and on his cross-country trips. His work has been collected in numerous monographs, including Passing Through Eden: Photographs of Central Park (2007); American Sports, 1970, or How We Spent the War in Vietnam (2007); Opera Città (2010); Core Curriculum: Writings on Photography (2011); Studio 54 (2014); Dr. Blankman’s New York: Kodachromes 1966–1967 (2017); On The Acropolis (2019); and At the Beach (2023). After curating Public Relations, the influential 1977 Garry Winogrand exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Papageorge embarked on a new chapter. He led the MFA program in Photography at the Yale School of Art from 1979 through 2013. Graduates during his tenure include Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Abelardo Morell, Dawoud Bey, Mark Steinmetz, An-My Le, Justine Kurland, Katy Grannan, Victoria Sambunaris, Richard Mosse, Kristine Potter, and the program’s current director, Gregory Crewdson. Ahead of the exhibition in Connecticut, I spoke with Papageorge about concentration, good vibrations, and why the hard work of photography is always a pleasure. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for space.

Lisa Kereszi: I read that you made the first round of beach pictures in Los Angeles at the tail-end of a road trip in 1975. What was the intention of driving cross-country?

Tod Papageorge: To photograph.

Kereszi: In the tradition of Robert Frank’s The Americans and Walker Evans’s American Photographs?

Papageorge: Every serious photographer was still thinking about The Americans in 1975, twenty years after the pictures were made, at least every photographer with a heart or brain. I was also thinking a lot about Garry Winogrand’s cross-country trip in 1964, which I consider one of the miracles of twentieth-century American photography, equally important in its own way as The Americans, in how it extended Frank’s discoveries.

Kereszi: How long would you stay in LA? A couple of weeks, a month, a couple of months each time?

Papageorge: Not months—a week or two at a time.

Kereszi: Did you come back from each trip with twenty rolls, fifty rolls?

Papageorge: We’re talking about less than one hundred and fifty rolls of 120 film over the four trips I eventually made to the beaches, eight exposures a roll. I’d started using medium-format cameras in 1973, which, because they produced negatives four times larger than my usual Leicas, beautifully described the brilliant light and casual lifestyle I found in California. Those six-neuf cameras (6-by-9 cm) also had the same 2-by-3 shape as the Leica, one that, by 1975, after thirteen years of practice, was hard-stamped on my picture-making brain-apparatus machine. So, because I generally knew what the edges of the frame were going to be when I was ready to take a picture, the act itself was simply a case of lifting the machine in a single gesture and pressing the shutter, tout de suite. Because the shutter speed was relatively slow at 125th of a second, this process was necessarily somewhat deliberate, but, again, consisted of a single action, usually for a single exposure, up and done. By that point in my evolution as a photographer, I was pretty good at recognizing the moment when my subject, or subject field, was cohering enough that I had a good chance of capturing at least a clear picture, if not a strong one . . . a long way of explaining that I didn’t shoot a lot of film.

Kereszi: On the nude beach, did people have a problem with you photographing?

Papageorge: No. I was discreet and quick.

Kereszi: But you had that big camera.

Papageorge: I’d wait and wait. When I talk about the picture being clarified, that’s exactly what I mean, the form being clear, or coalescing into clarity, across the frame. Which, of course, is what I was waiting for. And I’m not talking about simple pictures. On the contrary, they’re generally complex, where the challenge to making them was to really concentrate until I saw, or sensed—since, before anything else, this is a physical process—that the action in front of me was gathering into a readable form.

Kereszi: I am still trying to picture the entire scene with you in it.

Papageorge: I was dressed normally on both the regular beach and the nude beach. I wasn’t walking around in a bathing suit.

Kereszi: I’m imagining you’re standing there composing.

Papageorge: But I’m not composing. I’m watching intently, more animal than citizen. The camera’s not at my eye. I’m never looking through the camera.

Kereszi: Did you feel separate from what was going on, like there was a stage?

Papageorge: Good question. A stage. Particularly when I was using those 6-by-9 cameras: a stage, almost literally so.

Kereszi: There’s a physical distance?

Papageorge: Yes. With that machine, you need a certain physical distance to get the necessary depth of field and definition.

Kereszi: You say you felt separate, but did you interact with the people on the beach? Like, did you have a towel that you sat on? Or were you always walking?

Papageorge: I had no friends with me. And I never said a word to anyone there.

Kereszi: Are there pictures of people making eye contact that have been edited out?

Papageorge: Why? Did you notice that there were people making eye contact?

Kereszi: They’re not. It’s incredible. Which makes me wonder if the beach project was somehow an experiment for you?

Papageorge: In a way, yes, as in, Can this really be done? Or, Is it possible to use a clunky camera to contain and form coherent, meaningful pictures out of this complicated, shifting energy field of bodies? It’s always an experiment, but yes, the beach presented its own special problem.

Kereszi: When I asked you if there were any poems or a piece of writing that I could reference or think about in relation to these pictures, you mentioned the chorus to the Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations.”

Papageorge: Yes, but I didn’t know from the Beach Boys back then, or even today. I just felt a vibration when you asked the question.

Kereszi: But in retrospect, were you serious in mentioning it, was there some meaning to it?

Papageorge: Well, in a short text that I wrote in 1988 about these pictures, I suggested that the typical red-blooded American male carried around some mental image of the surfer and the California beach girl. So, I guess to that degree, I was serious. But I can’t really say I knew what I was talking about, beyond making an obvious reference to a cultural image created a few miles away from those beaches, in Hollywood. I’d never even seen an Annette Funicello movie—Beach Bikini, or whatever it was called, or any of the others.

Kereszi: Beach Blanket Bingo. I dug into the lyrics a little bit and tried to think about what you might be suggesting in mentioning it. There was a lot written at that time around the idea of psychedelia and “tuning in,” that “vibrations” had something to do with the ’60s idea that everybody was connecting to something and with one another, connecting with a vibe. But that has nothing to do with anything you’re saying, it seems.

Papageorge: It certainly has nothing to do with anything that I was working at. As you know, photography, at least out in the world of the “social landscape,” requires tremendous concentration and a virtually inflexible dedication to the job at hand, which, again, is to look intently. So, yes, good vibrations are fine for the people I might be photographing on the beach; in fact, the more they’re feeling them, the better it is for me because they’re acting within their own zone. But my zone is a different one—a zone of attention, you might say.

Kereszi: In your essay on Robert Adams, published in Core Curriculum, you discuss writing poetry, which you’d done as a college student, versus making photographs, and how the raw materials used in each medium might be related.

Papageorge: Both poetry and photography deal in the world, the world of things. To quote W. H. Auden: “It is both the glory and the shame of poetry that its medium is not its private property, that a poet cannot invent his words and that words are products, not of Nature, but of a human society which uses them for a thousand different purposes.” It’s an observation that also applies to the photographer and his or her dependence on the “ten thousand facts” of the physical world and, of course, Auden’s “human society.” To say it gracelessly, the job for the poet is to arrange the myriad “word-products” of language into poems that own the resonance of world-reflecting meanings as well as, one would hope, the music of sound, just as it is for the photographer to set his or her subjective curation of the world into a visible order that might be described as the music of things caught in a satisfying visual resolution.

Which reminds me to mention my love of music, something as important to my formation as an artist as anything else, including poetry or, once I’d started, making photographs. As it happened, by my junior year of college I knew, in a half-conscious way, that I was good at music, good at writing, and, later, good at photography. I eventually decided on photography (since it seems that I was destined to follow some kind of artistic trail) because I’d never been interested in being an orchestral musician and found poetry devastatingly difficult to deal with, given that my standard for it was very, very high. So photography came to supplant everything else. Not because it was easier, or because my eventual ambitions for it were any lower than my ambitions for poetry had been, but because it gave relatively quick and specific results, one frame after the next, where the elemental, binary vote of “good picture or bad picture” could be cast almost reflexively, with finality. No frustratingly incomplete poems to keep track of, or wither in the face of.

Kereszi: When you were a child, was there music in the house, or poetry?

Papageorge: Yes, there was music. My mother cared nothing for conventional homemaking; for example, I had to iron my own shirt for school every morning once I was tall enough to stand at the board. But there was an upright piano in the house, and every day she would sit at it and play. She’d taught herself, had perfect pitch, and every day she’d sit there to play and sing the popular American songbook. I’m sure that had a big effect on me.

Kereszi: You talk about symbols a lot in your essay on Evans and on Frank and in an interview with John Pilson. Are there symbols in the beach work?

Papageorge: No. There are bodies.

Kereszi: Bodies. Well, I also think about politics when I think about Frank’s work and symbols. And you started to make these beach pictures four years after American Sports, 1970, or How We Spent the War in Vietnam, right? I read in the same interview that you described yourself as being in a rage over Kent State while making the American Sports work. With this beach work being made just four years later, are you totally switching gears here—is there any political content?

Papageorge: There’s no political content, which isn’t to say that I wasn’t outraged by the political scene, certainly through the conduct of the Vietnam War and then later with Reagan. He was maddening to me. As were the two Bushes, totally maddening. Not that I was ever active politically. I never joined a group or marched or anything like that. So, no, the beach pictures are not political.

Kereszi: Well, it’s hedonism that you’re depicting; you’re showing hedonism, you’re showing escapism, recreation, while all this other stuff just goes on. Isn’t that part of your point? That subtitle of the sports book, How We Spent the War in Vietnam, makes it feel like you’re making a value judgment about all the mass distraction.

Papageorge: Yes, in that particular book. But when you consider my work in Central Park, Studio 54, the Acropolis, and, here, the beaches, you’ll see that these subjects share what might be called bounded realms or landscapes not unrelated to those we know from classical painting, poetry, music, and opera. In other words, there’s a more purely aesthetic ambition being explored in the work. I’m not saying it’s exalted: it’s not a Bach mass. But it is its own category, an aesthetic as distinct from the Leica pictures that make up my sports book as the Acropolis is distinct from Yankee Stadium.

Kereszi: On the escapism theme, though—when I think about these places that you’ve mentioned, like the island of Studio 54, the island of Central Park, the island of the beach, where people are getting away and escaping: you’re on the sidelines just watching?

Papageorge: No. And I don’t see those places as escapist at all. Rather they’re gifts, vivid and bright in themselves, but also grist for being transformed into poetry—as photographs! As crazy as Studio 54 is, as hot and exhausting as the Acropolis might be, as vibratory as Malibu seems, they’re all prelude to the possibility of becoming still pictures charged with meaning. My problem, then, far from simply watching, is to try to make pictures that express the feelings I’m imaginatively projecting from my experiences of life and art onto these arenas and ever shifting groups of people. To trace this process in any artist is complicated, if not impossible, as it’s necessarily tied up with the psycho-physio-cultural makeup of the person propelling it. It might be enough, though, to say, with Goethe, that “One only sees what one looks for. One only looks for what one knows,” which, in my case, has been the stew of poetry, art, and music—mixed with the meat and bones of a lucky life—that has effectively shaped me.

Kereszi: So these places and gatherings are occasions?

Papageorge: Yes, a good word.

Kereszi: Like occasions for compositions—for art?

Papageorge: Yes. In these cases, encouraged by the surrounding “realm.”

Kereszi: Right, they’re in that realm. But again, you’re not?

Papageorge: No. I’m totally in mine, while watching intently for what I’ve described as a kind of visual/musical gathering toward a picture—and, with that, perhaps, meaning. It’s not as if you’re making compositions, though; it’s more that you’re employing a unique system of visual indication—photographic description—to describe a discrete part of the world in a transparent way.

Kereszi: Speaking of that kind of visual clarity, in your essay on Robert Adams in Core Curriculum, you referred to the sun in his pictures as “pitiless.” And I would say some of that same light is in Walker Evans’s pictures: pitiless. Is it pitiless in your beach pictures?

Papageorge: No, no. On the contrary. It’s Titian blue, ultramarine (perfect word). Bouncing off the sand, picking up reflections and color. It’s glorious. Glorious light. And I think the photographs suggest that.

Kereszi: How did you know when this body of work was finished?

Papageorge: It’s all in the course of a life being lived and photographs being made. It’s not as if I’m just thinking about photographing with a big camera on a beach in Los Angeles through that period. I was also working in New York and, in the ’80s, making a lot of trips to Europe, to Paris, back and forth, photographing intensely, often with my Leicas.

All photographs by Tod Papageorge from At the Beach, 1975–80

All photographs by Tod Papageorge from At the Beach, 1975–80Courtesy the artist and Stanley/Barker

Kereszi: So did you not feel pulled back to LA to photograph on a fifth trip?

Papageorge: At some point years after the fact of the four trips and making these pictures, I noticed on one of my contact sheets a few frames of Wilt Chamberlain sprawled in the sand. And I asked myself, Well, what are you going to do with these? There was also the more extensive beach work I’d done in 1988, on a grant from AT&T, sitting in a box. Not to mention that my wife, Deborah, a ballet dancer, always loved the pictures she’d seen from this body of work and encouraged me to push ahead with it. Leading me, finally, to collect the contact sheets, edit them, scan the selects, and discover that the whole thing added up to something worth exhibiting.

Kereszi: Earlier we were talking about this being something of an experiment. Can you define what you think you were looking for versus what you found?

Papageorge: Imagine first seeing it, the beach, the California beach, the California beach in glorious light: that’s the given. Which is a lot. But I don’t receive that gift expecting anything in particular from it. I have no image of that. I just know enough to realize it will be a process filled with delight. Because no matter how hard the work is, it’s a pleasure. It’s the pleasure of my life to make photographs.

Tod Papageorge: At the Beach is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Connecticut, Westport, June 26–October 26, 2025, along with In the Pool, a group show of selected graduate student work from the years Papageorge headed the photography program at the Yale School of Art.

Why Photographs Mean So Much to People in Prison

The oldest photo I have is of my father. My aunt Terry sent it to me fifteen years ago. My dad and I never had a loving relationship, and I never shook the bitterness I held for him. He was a hard man who never quite figured out how to be loving. He was distant and, probably because of his alcoholism, sometimes cruel.

I had shared that hurt with my aunt. In response, she sent me an elementary school photo of my dad to reveal another side of him. In the picture I saw an unsmiling boy trying to mask his pain.

Childhood photograph of Derek LeCompte’s father, ca. 1964

Childhood photograph of Derek LeCompte’s father, ca. 1964My father had a blind eye from a childhood injury, with only whiteness in it. He was sensitive to people staring at his eye, so I can imagine how mean kids were about it growing up. He probably became hardened as a strategy for coping with the way his peers treated him. Through this photo, I developed a new connection to my father—relating my own personal suffering to the pain he had experienced. The picture reminds me to find sympathy for everyone, even people who have harmed me.

In prison, photos are some of the most cherished treasures we have. We lose so much to incarceration; photos are a safeguard against further loss. I have hundreds kept in photo-albums that I dressed up like scrapbooks. I also taped some to the bottom of the bunk above mine so I see them every time I wake up. Those pictures are of the people I love most.

Now that I have an electronic tablet and electronic messaging, it’s easier for people to send me photos. I frequently scroll through pictures on my tablet for a refresher. But there are a few prized photos, in particular that I hold so dear I refuse to give them up.

Derek LeCompte’s father (right) and grandmother (left), ca. 1976–77

Derek LeCompte’s father (right) and grandmother (left), ca. 1976–77One of those gems is a photo of my father and grandmother dancing at my parents’ wedding. It brings a smile to my face because my grandmother looked beautiful; other than that picture, I’ve never seen her wearing a nice dress, with her hair styled. She had a smile on her face as she danced with her boy.

The photo also makes me laugh because it reveals how much my father idolized Elvis. He only loved two things: Elvis and country music. He had the same hairstyle and fashion sense as Elvis, but he looked like a heavier version of the rock star. I like to imagine that the reason my dad is smiling in the image, which he rarely did, was because they were dancing to country music or Elvis.

Christina VanGaasbeck, ca. 1990s

Christina VanGaasbeck, ca. 1990sI have quite a few photos of my sister Christina, who was an infant when I was arrested. I only met her after I was sent to prison. She means the world to me. Most of my photos of her are posed and formal, but the one I love most is a picture in which she’s acting goofy and scared by a T-Rex at Universal Studios in Orlando.

She was able to go places I never got to visit, so I have enjoyed living vicariously through her. My mother took the photo as my sister threw her hands up in an “oh my God!” pose with a silly face. Seeing my sister in her naturally goofy state warms my heart because I would have been doing the same thing with her if I had been there.

Derek LeCompte (right) with his mother (left), holding Christina VanGaasbeck (center), ca. 1990s

Derek LeCompte (right) with his mother (left), holding Christina VanGaasbeck (center), ca. 1990sUnfortunately, over the last quarter decade, I’ve changed prisons several times and lost a few cherished photos. This has been devastating.

A photo I wish I still had is of my mother standing in the grass outside of her home from before I was born. She’s barefoot in what I would call a hippie outfit with bell-bottoms and a frilly white blouse, wearing a bunch of bracelets and a flower in her hair. She looked stunning in the photo, happy and smiling broadly. There was a radiance to my mother I had never seen.

She was a hippie, so maybe she was a little high. But I sometimes feel like I took that radiance away from her because she never smiled at me that way. During my time with her, I remember my mother having a sad plainness to her. She didn’t try to dress with any particular flair, style her hair or even accessorize her outfits. That’s why seeing her in this different light was so meaningful to me.

Derek LeCompte (center), with his mother (left) and Christina VanGaasbeck (right), ca. 1990s

Derek LeCompte (center), with his mother (left) and Christina VanGaasbeck (right), ca. 1990sThe other photo that comes to mind is another one of my father. An uncle sent it to me to prove my father didn’t always lack a fun personality. It was a photo of him in his early twenties. He’s wearing bright orange bell-bottoms and a super-tight silk shirt.

He tried so hard to be fun in this photo, but he still looked miserable. Someone probably convinced him to let them dress him up. Anyone who has ever tried to dress a cat in a costume knows the look I’m talking about—pure misery and an expression that says, “Take this damned thing off of me!” When my dad found out my uncle sent the photo to me, he ordered me to burn it. He was too embarrassed to have anyone see him in bright orange bell-bottoms.

Left to right: Derek LeCompte at his High School graduation, ca. 1990s; Derek LeCompte (left) and Christina VanGaasbeck (right) at LeCompte’s graduation, ca. 1990s

Left to right: Derek LeCompte at his High School graduation, ca. 1990s; Derek LeCompte (left) and Christina VanGaasbeck (right) at LeCompte’s graduation, ca. 1990sAll photographs courtesy Christina VanGaasbeck

I had that photo up until I was transferred to my current New Jersey prison in 2018, where it was yet another casualty of a transfer. I like to think my father paid a guard to “lose” it.

When you spend decades locked up like I have, you learn that loss is at the core of prison life. I’ve been incarcerated since I was nineteen, for more than twenty-five years. Since then, I’ve missed out on a lot of things, and I’ve lost all of my grandparents and parents. That’s why I hold on to pictures of them. I can no longer make new memories, or have new moments to capture with them, and the photos I’ve lost are gone forever.

Over time, memories of my parents and grandparents are fading too. I try to preserve those memories by closing my eyes and envisioning them, but some memories have gotten fuzzy. Memories often bring solace in prison, so capturing them in photos brings a layer of permanence. Remembering cherished moments is the best I can do to shield myself from how swiftly time passes on the outside.

But even more than that, those captured moments are a reminder that life is full, and there are going to be opportunities to make new, joyful memories in the future. Maybe those memories will be just as meaningful to someone else.

This article is copublished with the Prison Journalism Project.

June 24, 2025

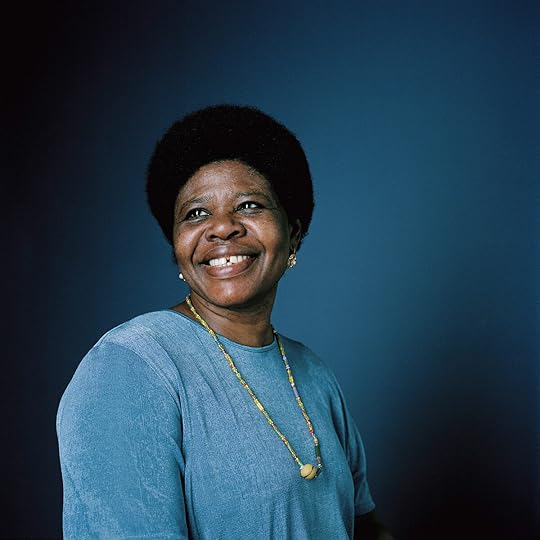

Eileen Perrier’s Alluring Portraits Show How Love and Fear Are Intertwined

Like many photographers, Eileen Perrier was given a camera as a child, and that’s where her story began. While studying for her university entrance exams, she took an introductory course in photography, and another in dressmaking, and found she loved photography. She studied at the Royal College of Art in London. Her initial images were of people she encountered in Ladbroke Grove and other parts of the city. Soon she met the photographer Armet Francis, one of her heroes, who became a mentor, showing her how to handle her prints and encouraging her to put work forward for publication.

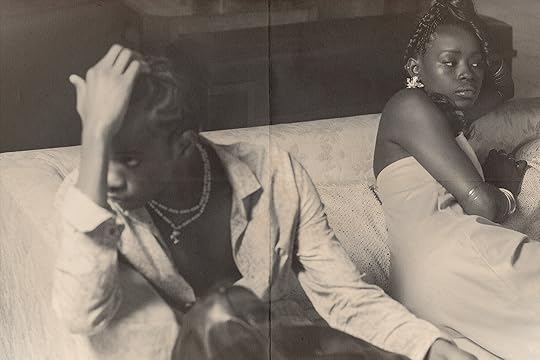

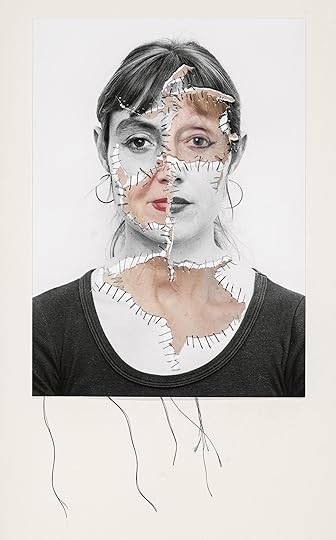

Eileen Perrier, from the series When am I gonna stop being wise beyond my years?, 2023

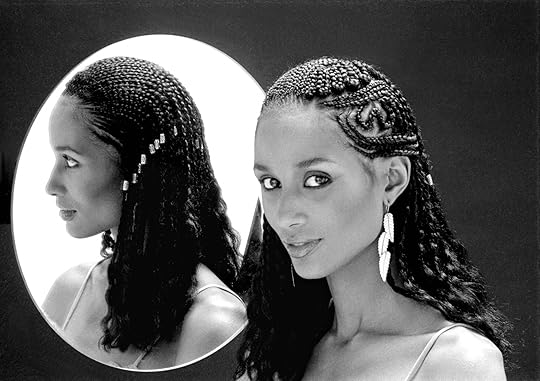

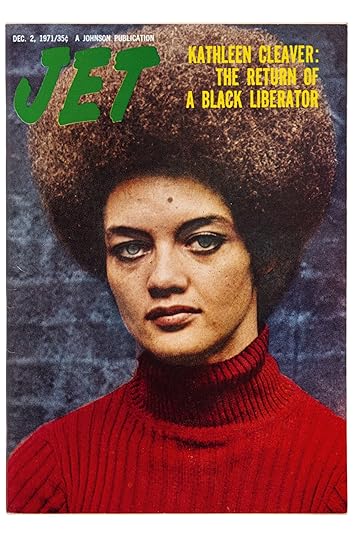

Eileen Perrier, from the series When am I gonna stop being wise beyond my years?, 2023 Eileen Perrier, from the series Afro Hair and Beauty Show, 1998–2003

Eileen Perrier, from the series Afro Hair and Beauty Show, 1998–2003‘‘I just got the bug, you know, that thing where everyone says the magic of being in a dark room and then you see an image appearing in there,” Perrier said recently. Her work is now the subject of a solo exhibition, A Thousand Small Stories, at Autograph, in London’s East End. As the curator Bindi Vora explained, the title illustrates how each individual experience, no matter how minor it may appear, contributes to a bigger, shared narrative. This concept aligns closely with the sociologist Stuart Hall’s insight that images can express meanings that reach far beyond their immediate surroundings, enabling us to envision and comprehend more than just what is presented in the frame.

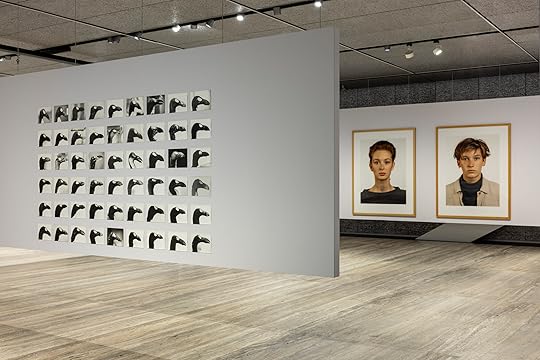

Installation view of Eileen Perrier: A Thousand Small Stories, Autograph, 2025. Photograph by Kate Elliott

Installation view of Eileen Perrier: A Thousand Small Stories, Autograph, 2025. Photograph by Kate ElliottThe exhibition opens with When am I gonna stop being wise beyond my years?, a series from 2024 that delves into the challenges teenage girls encounter as they navigate social media, body image, and misogyny. Perrier’s fascination with the complex politics surrounding beauty is further evident in her renowned portraits from the late 1990s and early 2000s, particularly in Afro Hair and Beauty Show (1998–2003), which emphasize the important role of hair and hairstyles as markers of cultural pride and resilience. The young participants sit there, oozing self-confidence.

What makes this section special is an installation created with replicas of Black haircare products from the ’90s, on plinths. Perrier has collected these products over the years, and Vora noticed, in her research, that their packaging has often stayed consistent. Vora felt that displaying them would demonstrate “in a very tangible way, the aspirational branding still in use today.”

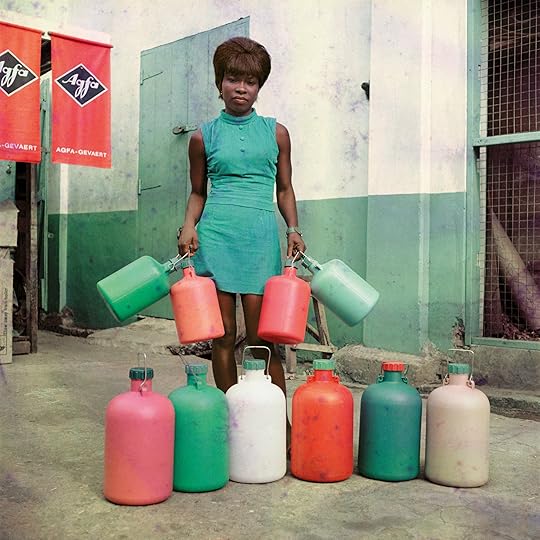

Eileen Perrier, from the series Ghana, 1995–96

Eileen Perrier, from the series Ghana, 1995–96 Eileen Perrier, from the series Ghana, 1995–96

Eileen Perrier, from the series Ghana, 1995–96In 1995, Perrier made a pivotal trip to Ghana. Until then, most of her images were made in black and white. In Ghana, she gained confidence in using colour. “All the images I was seeing at that time were black and white,” she said, mentioning the kind of photography commissioned for foreign charities. “And I just didn’t want to emulate or recreate the images they were portraying.” In one close-up of a bottle of Cussons baby powder, the pale blue wall in the background complements a white bottle with a picture of a blonde baby and the name of the product in baby blue. Perrier, who regularly used Cussons as a child, sees it as an emblem of neocolonial economics: at the time, the company did not bother to differentiate the packaging for an African market.

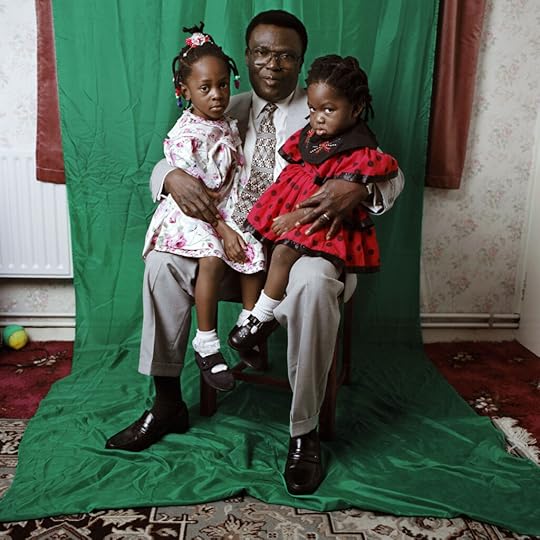

Perrier frequently immerses herself in communities, a spirit of collaboration that resonates in her series Red Gold and Green (1996–97), which was commissioned by Autograph. Here, she joined forces with first-, second-, and third-generation British Ghanaians, friends of her mother’s and extended family, to craft intimate portraits within the comfort of her subjects’ London homes. Perrier’s temporary home studios beautifully reflect the complex blending of modern migrant identities. Symbols from various homelands subtly appear in the background, and vibrant textiles recall longstanding traditions of African studio portraiture. In the exhibition, a vitrine displays ephemera connected to the series, showing, as Vora notes, how Perrier’s “three decades of working as an artist come together beyond just the final images.”

Eileen Perrier, from the series Red, Gold and Green, 1996–97

Eileen Perrier, from the series Red, Gold and Green, 1996–97 Eileen Perrier, from the series Grace, 2000

Eileen Perrier, from the series Grace, 2000All photographs courtesy the artist and Autograph, London

Another celebrated series considers a painful memory. As a child, Perrier faced teasing for the gap in her teeth, a feature she rarely saw in others around her. Aware that it is seen as a sign of beauty in various cultures, she made the series Grace (2000), which comprises images of people with their faces angled towards the camera, facing right and smiling so their teeth are on display. Perrier herself features in a self-portrait along with a portrait of her mother. The personal connection Perrier builds with her subjects goes beyond simply taking their photographs. Instead, a sense of social engagement permeates her work—an alluring reminder that our experiences of love and fear are intertwined, allowing us to perceive them through one another’s perspectives.

Eileen Perrier: A Thousand Small Stories is on view at Autograph, London, through September 13, 2025.

Inside Rosalind Fox Solomon’s New York Studio

This article originally appeared in Aperture, Spring 2023, “We Make Pictures in Order to Live,” under the column Studio Visit.

Rosalind Fox Solomon’s home and studio are on an upper floor of an eight-story former commercial building in the NoHo Historic District of New York. Completed in 1893 and named by the Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1999, it was designed by the German American architect Alfred Zucker at a time when the area’s Federal-style mansions were being replaced by high-rise structures.

Fox Solomon has lived and worked inside Zucker’s iron, granite, and terra-cotta building on Broadway since 1984. Her loft is a treasury for a nomadic life spent traveling around the world taking photographs of people—meeting them where they live. For more than fifty-five years, she has built an affecting body of images attentive to the human condition, probing its vulnerability and struggles, scrutinizing the pleasures and toxicities that define us. “What I was interested in was psychological . . . what was going on inside people,” Fox Solomon told me.

Entering for a recent visit, I’m greeted by the photographer’s cat, Little Lady Lola, and immediately encounter a large sculpture, of human height, created by the artist in 1980. Titled Adios, the piece (something of an homage to her divorce around that date) is based on tombs in Peru. “I really loved working there,” Fox Solomon says. “At that time, people came to mountain climb; otherwise there weren’t any tourists. It was kind of untouched.” Fox Solomon has traveled extensively throughout the United States, as well as to remote places in Asia and Latin America. The studio’s walls are filled with her own images, interspersed with art and objects collected on the many trips. Portraits by Julia Margaret Cameron and Richard Avedon—of John Szarkowski—also adorn the walls.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Born in a Chicago suburb in 1930, Fox Solomon began photographing with an Instamatic camera at the age of thirty-eight while living in Chattanooga, Tennessee, with her then husband and two children. While participating in a cultural exchange program called the Experiment in International Living, she cultivated an interest in travel and photography. On a visit to New York, she was introduced to Lisette Model, the legendary Austrian-born American artist who helped redefine street photography. In 1974, Fox Solomon began studying privately with Model, continuing until 1976. A mere decade later, the Museum of Modern Art organized Rosalind Solomon: Ritual, an exhibition of thirty-four pictures made between 1975 and 1985.

Her photographs complicate and layer meaning, challenging viewers to go beyond familiar narratives. Early examples taken in the 1970s pointedly capture the legally desegregated but still racially divided American South, a place Fox Solomon would photograph into the 1990s. A collection of these images is featured in the book Liberty Theater (2018), named after one of the last cinemas in Chattanooga to remain segregated. Abroad, Fox Solomon made photographs that depict cultures and locations amid political strife—violent terrorism in Peru, apartheid in South Africa, ethnic violence in Northern Ireland—but that move beyond conventional documentary description to work that is suggestive of her relationship with her subjects. “I don’t like to talk too much to people when I’m photographing because I’m interested in reaching the interior. I don’t want them to be functioning on a superficial level,” she says.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

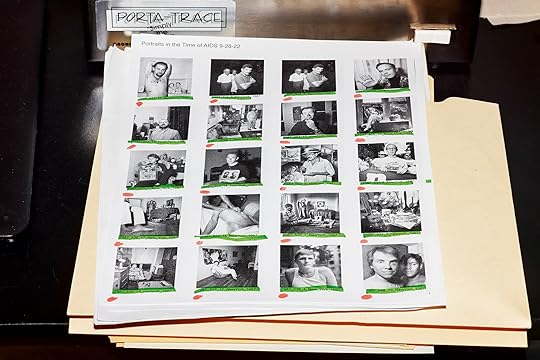

At ninety-two, Fox Solomon shows no signs of slowing down. Her groundbreaking and intimate project Portraits in the Time of AIDS (1987–88), first exhibited at the Grey Art Gallery at New York University, three blocks from her apartment, was recently acquired by the National Gallery of Art. Last year’s edition of Paris Photo included a solo exhibition, organized by MUUS Collection, of Fox Solomon’s early series from the 1970s portraying scenes at a flea market in Scottsboro, Alabama. She is currently focused on a new book due out this year. “I’m enjoying having my work get out the way it’s been getting out,” she says. “It’s exciting to have all this going on at my age. I’m really fortunate to have lived to see this recognition. It’s kind of beyond belief.”

All photographs Rosalind Fox Solomon home studio, New York, October 2022

All photographs Rosalind Fox Solomon home studio, New York, October 2022Photographs by Jason Nocito for Aperture

Never one to photograph commercially, and rarely on commission, Fox Solomon has had a prolific career that includes more than thirty solo exhibitions and a hundred group shows; her work is held in prominent museum collections worldwide. Even decades after she photographed them, Fox Solomon’s remarkable pictures continue to hold their power. They are as much about the subjects and how they see themselves as they are about how we see and understand the subjects. Her particular method of portraiture urges us to examine people and our preconceptions more carefully.

“If I had the courage, today I would go photograph people on the extreme right. That’s what I would be attracted to doing,” says Fox Solomon. “And probably I could do it because I’m old and nobody would think of me as dangerous. That was how I did a lot of my work. Because I was always older and I just don’t think that people were afraid, although I think they could have been.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 250, “We Make Pictures in Order to Live,” Spring 2023.

June 20, 2025

A Portrait of Creative Community in Ivory Coast

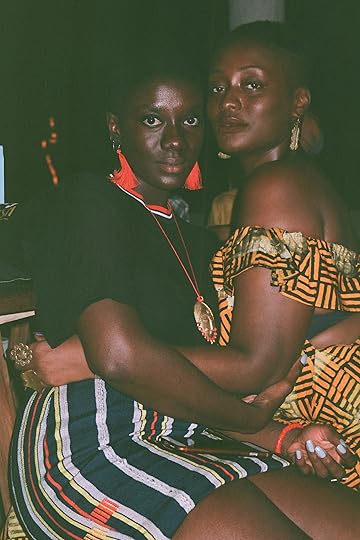

A slinky crease of a jacket, a streetlight lurking in the background, marbles resting in the scoop of a collarbone, flowers forming a shadow on a model’s face. These intense details of light, shape, and form heighten an atmosphere of crepuscular intimacy in the brooding and buoyant images of Nuits Balnéaires, a photographer, musician, filmmaker, poet, and set designer based in Grand-Bassam, Ivory Coast.

Nuits Balnéaires’s interest in photography can be traced back to some high school modeling he did casually for friends. “In that age, it was the boom of Facebook,” he told me recently. “It was all about doing cool photos for social media.” When his mother came back from a trip with a compact Sony camera, he began to make his own pictures. This eventually led him to the fashion industry—magazines, advertising, brand photography, as well as deep admiration for the know-how of local artists and designers in Abidjan, Accra, Lagos, and Dakar. “It was a great environment to learn,” he said. “But at some point, I had that need to focus on more personal stories.”

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

After moving in 2019 from his former home in Abidjan (Ivory Coast’s de facto capital) to a new-to-him scene in the small, historic town of Grand-Bassam, Nuits Balnéaires was renewed by nature. His embrace of landscape is evident in depictions of soft water bathed in twilight. After all, the moniker Nuits Balnéaires translates to “seaside nights” in English and is also meant to provoke what he refers to as an “idea of nostalgia, this melancholy of the Gulf of Guinea, this strong relationship to memory.”

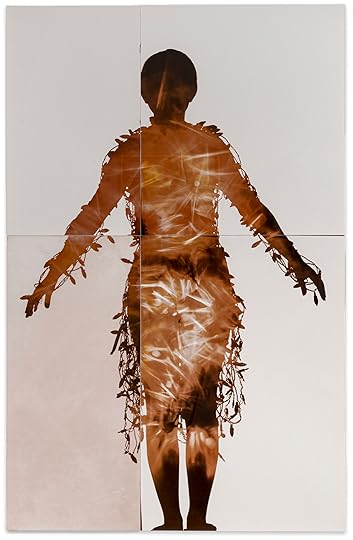

In Grand-Bassam, he created a meditative series called Scent of Appolonia (2021), in which he pays homage to the land of the N’zima Kôtôkô people, an ethnic group of southwestern Ghana and southeastern Ivory Coast. “I was very interested about the link between those territories and the resilience and the sustainability of this whole culture, despite the borders that we inherited from the colonial era,” he explained. “These people still coexist, still share things, even if they exist in those two lands and are separated by these borders.”

Nuits Balnéaires, from Dreaming, Ivory Coast, 2020

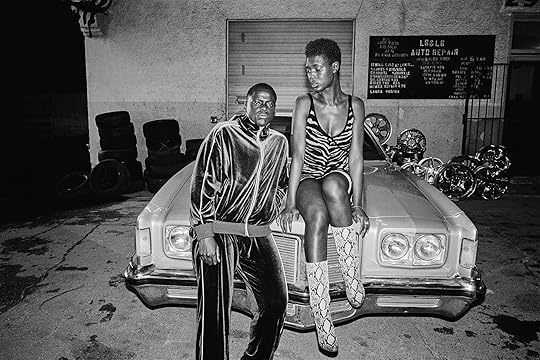

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }Nuits Balnéaires’s interventions, then, mark a wider community. His subjects include friends, professional models, and family. “I work a lot with my sister, who is definitely my main muse,” he said. Another series stems from a partnership with a curatorial platform, Yua Hair, which focuses on textured hair in Africa and the African diaspora. These exquisitely staged photographs take their inspiration from 1960s and 1970s West African studio portraiture, where self-fashioning was understood as a political act within Africa’s postcolonial cultures. A relentless respect for fashion, tailoring, jewelry, craft, and aesthetics are, to Nuits Balnéaires, “a way to really reclaim that identity which is strongly African, but also with a lightness that equals an openness to the world, to this contemporary world, to this global world in which we exist today.”

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

While Nuits Balnéaires’s crisp and ecstatic images suggest an homage to iconic West African photographic practices, they also attempt to forge ahead, naming and creating a contemporary culture that is specific to his community in Ivory Coast but encouraged by friends in Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal, Europe, and the United States. “I feel like I’ve been so nourished and built up by the space I come from and its people,” he said with pride. “I think I’ve been lucky.”

Nuits Balnéaires, from Infinite Stories for Yua Hair, 2024

Nuits Balnéaires, from Infinite Stories for Yua Hair, 2024  Nuits Balnéaires, from Infinite Stories for Yua Hair, 2024

Nuits Balnéaires, from Infinite Stories for Yua Hair, 2024  Nuits Balnéaires, Keren Lasme et Noella Elloh, Ivory Coast, 2018

Nuits Balnéaires, Keren Lasme et Noella Elloh, Ivory Coast, 2018  Nuits Balnéaires, Guy Martial, Ivory Coast, 2018

Nuits Balnéaires, Guy Martial, Ivory Coast, 2018  Nuits Balnéaires, from Infinite Stories for Yua Hair, 2024

Nuits Balnéaires, from Infinite Stories for Yua Hair, 2024  Nuits Balnéaires, La Fleur D’Appolonie (Scent of Appolonia), 2021

Nuits Balnéaires, La Fleur D’Appolonie (Scent of Appolonia), 2021All photographs courtesy the artist

This interview originally appeared in Aperture No. 259, “Liberated Threads.”

June 14, 2025

Melina Matsoukas Creates Space for Black Stories in Hollywood and Beyond

Melina Matsoukas has made a lasting mark on visual culture as the director of unforgettable music videos—among them Rihanna’s “We Found Love” and Beyoncé’s “Formation”—and the 2019 feature film Queen & Slim, which bends the romance outlaw genre into an utterly contemporary meditation on police brutality and Black love.

In some ways, though, it feels like Matsoukas is just getting started. The Los Angeles–based polymath is currently developing a flurry of passion projects (the only projects she does), among them adapting a legendary female mobster’s life for the screen and documenting her own experience as a new mother. On top of everything, Matsoukas also runs De La Revolución, a bicoastal collective of photographers and directors that she founded in 2021 as an alternative to exploitative models of inclusion in the creative sphere.

Solange Knowles, the singer-songwriter, recently sat down with Matsoukas for the “Barbara Walters treatment,” interviewing her friend and collaborator about her expansive image making across the fields of photography, music, television, commercials, and film.

Andre D. Wagner, for Melina Matsoukas’s “Precious Cargo” campaign, Levi’s, 2023

Andre D. Wagner, for Melina Matsoukas’s “Precious Cargo” campaign, Levi’s, 2023  Ming Smith, Sun Ra, Space II, New York, 1978

Ming Smith, Sun Ra, Space II, New York, 1978Courtesy the artist

Solange Knowles: One of the powerful things about an image is that it lives far beyond us, forever. At what age did you understand the gravity of image making?

Melina Matsoukas: I was raised by freedom fighters. My parents were part of a socialist movement called the Progressive Labor Party, and I was raised to create change and incite dialogue, to challenge the status quo and how people think. I always felt like I had this purpose to do these things and honor my family and the people that empowered me. I just didn’t know what the tool or medium would be to do that.

In high school, I started dabbling in photography. My father was an amateur photographer, and he introduced me to the power of the lens and the idea of documentation and what that can do as a tool in the revolution. And then, when I got to college—I went to New York University—I really started understanding the reach and the scope and the conversation and the story you could create with the photograph, and understanding the power of filmmaking to reach the world and to give voice to the unheard, to document communities that we don’t necessarily see all the time, and use that power to unify people. That felt like my purpose.

Knowles: I love this origin story. I didn’t know your father was an amateur photographer.

Matsoukas: He’s going through all his slides now, thousands of slides of our family and friends, and just our lives. It’s so beautiful to have that archive.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Knowles: I think a lot about the photographs that you took in Cuba in 2001 and how personal and intimate and special they are, and the gravity they hold. Although, obviously, your style has evolved and changed, I still see the loving, tender, and attentive gaze of how you see Black women—and have always seen Black women—in those images, celebrating their strength and vulnerability, but also allowing them to just be. I wonder how your adult self sees those images.

Matsoukas: NYU had a summer exchange program where I went to Cuba and studied photography for a summer. That was actually my first time in Cuba, my first time returning to my mother’s homeland. It was an incredible experience to be able to take that camera and have the courage to photograph people—and learning how to do that and thinking of Ming Smith and Gordon Parks and Anthony Barboza, all these people who have documented our history. I remember being shy, and not wanting to essentially steal these images of people without asking permission. But then, it’s a hard dance to play. You ask permission and then people start posing, and that’s not necessarily what you want. Anyway, I was able to really hone the skill of being a street photographer there.

At the same time, I had this other side of me, and I still do, where I like fashion and celebrating Black women and bodies, and embracing our sexuality and our beauty. One of my main goals in life is to change the idea of what traditional beauty looks like in our culture. I was also able to photograph some of my friends and the people that were on the trip with me, and other Cuban women. I did a series of nudes, I remember.

Knowles: And some pregnant women.

Matsoukas: Yes, that was a friend of mine. When I look back at those pictures, I feel like, Oh, they’re very amateur. It was definitely part of my journey to understand the technicality of how to take a photograph. But there’s a lot of themes in that work that have continued and evolved through my career, which seems pretty evident, in terms of how I look at Black women and try to celebrate them and honor the role that they’ve played in my life and my artistry.

Still from Melina Matsoukas’s music video for Solange Knowles’s “Losing You,” 2012

Courtesy the artist

Knowles: When you talk about the song and dance between the gaze and the lens, and also finding that trust with people to capture them authentically, I often think about our first time—well, second time—working together, which was the video for “Losing You,” and being in South Africa, and us wanting to enter the continent with as much sensitivity as possible. When you pull out the camera, you feel definitely a little shy or hesitant in some ways. But as soon as the cameras came out, the sapeurs came to life. I know from being on the other side of the lens, sometimes the photographer can have all of the technical skills in the world, the best lighting, the best set design, or can capture on an expert level—but if the synergy is not there and I don’t feel comfortable or safe, then my jaw is tight and it’s clenched, and you can see that in the image. Are there any specific skill sets you bring to the experience to have people put their guard down and feel safe with you to capture them at their most vulnerable and authentic?

Matsoukas: I think the key to that, and to my success, is humility and respect for the subject. My job has always been to tell someone else’s story. It’s never to tell my story. I’m trying to document and bring out somebody else’s influences and feelings and values and inspirations. So it never begins or ends with me.

Knowles: I think that you are one of the best commercial directors of our generation, and I know it’s really difficult to find a way to maintain a sense of authenticity and integrity and even spirituality when working with commerce and the idea of selling something. It’s something that I actually have thought a lot about in my practice, because in our creative industries, people sneer or frown upon commercial work, despite the gravity to storytelling and the incredible ways that you can use commercial work to tell stories. That’s something that I’m fascinated by.

What is your approach to commercial work? And how do you choose the projects that you wish to be a part of?

Matsoukas: I was so influenced by pop culture, with MTV and music videos and, honestly, with commercials. I always wanted to start on music videos. In my younger years, I definitely did things just to pay bills. But at one point in my career, I was like, I can’t do this anymore; it’s not worth enough to work on things I’m not passionate about.

So in my commercial work, I try to find brands or stories that I believe in. And with commercial work, the reach is so much greater because of the money behind it. I find that it’s actually a great way to create change. When we talk about changing what the standard of beauty is, that’s created by commercials—commercial advertising and what you see on television and all of that. So in order to be a part of that dialogue, you have to actually enter that dialogue.

I try not to get too product heavy. I hate shooting products, so that’s kind of a deal breaker for me. But I love to tell stories. I made a Levi’s commercial two years ago, in Jamaica. I’m part Jamaican, and they sent me a story of how Levi’s in the ’70s made its way to Jamaica, and these people made it their own, and it was kind of the staple of reggae and dancehall, and the role that denim played in that culture. I felt such closeness to that subject matter and that era and time and that visual language.

Anthony Barboza, Portrait of Beverly Johnson, 1970s

Anthony Barboza, Portrait of Beverly Johnson, 1970sCourtesy Getty Images

Andre D. Wagner, Still from Melina Matsoukas, Queen & Slim, 2019

Andre D. Wagner, Still from Melina Matsoukas, Queen & Slim, 2019Courtesy the artist

Knowles: I want to use that as a segue into De La Revolución and talk about how you have transitioned not only as a businesswoman and an agency but as a mentor to emerging directors and photographers, and what that day-to-day looks like for you, how that’s changed the way that you approach your own work. Tell us more about that.

Matsoukas: So I did a film called Queen & Slim. I fought really hard to bring in four different photographers to shoot alongside me as I was making that film, to interpret the film in a way that was different than what I was shooting. One of them was Andre Wagner. He’s an amazing, primarily street, photographer. I call him our generation’s Gordon Parks. I also invited the incredibly talented photographer Lelanie Foster, who was there the whole time. She’s my cousin, too, so that helps. She was able to photograph the actors and the behind-the-scenes, and have access in a way that I thought was just so powerful. I brought Awol Erizku there a couple times to take objects from the film that symbolize the story and create still lifes around them.

I loved the idea of this collective coming together to tell one story. I thought back to the Kamoinge Workshop, the Black collective in the ’60s. Anthony Barboza was part of it, Ming Smith, Shawn Walker, Daniel Dawson, Jimmie Mannas, and many others.

In my journey, I’ve gone from photography to music videos, to commercials, to narrative and film, to TV—and they’re all very separated. There’s not a lot of crossover in terms of the people you work with, and the crew. They like to keep it so segregated. I hate that, because obviously there’s incredible crossover. So being a part of this collective during my film inspired me to create a space that actually helps guide directors and photographers in their goals and what they want to achieve.

De La Revolución was born of a time when people were starting to exploit Black artists, and feeling like, Oh, I want to have this person on my roster because they’re Black, and I want them to shoot Black people, but I have no understanding of the culture, I don’t care about who this is profiting, where it’s going, I just want to check a box. I wanted to provide a safe space that felt more like community, a collective of support and empowerment. So that’s why I started De La Revolución over one banner. My mother is from Cuba and was a child of the revolution, so I feel like I’m a child of the revolution in ways that I’ve inherited from her.

I always felt like I had this purpose to do these things and honor my family and the people that empowered me.

Knowles: I’m so proud of you and what you’ve done with. . . would you call it an agency? A studio?

Matsoukas: It’s all of that. Agency, studio, production company, collective, whatever you want it to be. That’s family. That’s who we are.

Knowles: It’s been incredible to watch it unfold. Thinking about Queen & Slim, and the world that you created not only with just the film but with the music and with the style and with the rollout and the stills, what have you learned from that process of world making and the importance of the space that surrounds the film just as much as the film itself?

Matsoukas: That was an incredibly challenging journey, creating the film. I didn’t realize it, because I had never done a film, that the way that you market it is just as important to the success of the film as the film itself. So for me, it actually was a way that I was able to take what I felt my skill set was and bring it all together. Obviously, I started in music, so the music’s going to be really important. The collaborative nature of filmmaking is what I truly enjoy and flourish in, and is one of the reasons I became a filmmaker. So to have all these different, incredible artists involved in the making, but also the rollout, of the film was really important, and it felt important to stay true to the messaging behind the film.

We wanted to make sure our community had access to the film first. So we had a screening at the Underground Museum in LA and the Brooklyn Academy of Music in New York before it was out, and we focused on Black publications and journalists first before we brought it to the broader audience.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Knowles: I’m curious how at this stage, after your success with Insecure and The Changeling, you decide on other projects you want to pursue.

Matsoukas: I’m working on a lot of things. I’m developing a film based on Marlon James’s novel A Brief History of Seven Killings (2014), which is a story that takes place in ’70s Jamaica and moves to ’80s New York—two periods that are very important to me in my life and my artistry. I’m working on a film on Stephanie St. Clair, who was this West Indian woman who ran Harlem during the Harlem Renaissance and protected it from white mobsters. It’s a gangster flick about this incredible woman who has been erased from history. And I’m working on a TV show on Jack Johnson, who was the first Black heavyweight boxing champion—he’s from Galveston, your place—with HBO. That’s a series. There’s a bunch of other projects that are in the works that I hope will come to fruition in the next couple of years. I’m also working on raising my baby and documenting that journey of motherhood and life.

Knowles: I love seeing you as a mother to Charli, and I’m very excited to see how that will impact and influence your work in your lens as well—because I know that it will.

I had a few other questions. My favorite moment, among my top three Melina moments, was Master of None’s “Thanksgiving” episode. The fact that you created such iconography with one episode.

Matsoukas: I never really wanted to do episodic work because I like to create the world from inception. But Lena Waithe is a very persistent person, and she really wanted me to direct this episode of Master of None, which was a bottle episode about her character coming out as a lesbian to her mother, played by Angela Bassett. The story is told through several Thanksgivings, from childhood to adulthood. Like I say with everybody, “Send me the script or the song or whatever it is, and if I love it, I’ll do it.” And I fell in love with the script.

Photographer unknown, Portrait of Madame Stephanie St. Clair, 1930

Photographer unknown, Portrait of Madame Stephanie St. Clair, 1930

Courtesy Bettmann/Getty Images

Knowles: I love that about your work, that no matter what the medium is you have such a distinctive fingerprint. Whether it’s a music video, a film, just one episode, or a photograph, we can quickly identify that it is your language.

My last question is about the power of image making through the lens of Blackness. I feel like there was a renaissance in photography and filmmaking of Black artists, but that renaissance was through the gaze of whiteness and white validation. It’s been really interesting to see this moment in 2020 when everybody was running out to prove that they saw us and that they valued us in one way or another. What do you think the future looks like for Black artists, Black filmmakers, Black photographers in this space? And what would you like to see the world look like and evolve into?

Matsoukas: I feel like there was a renaissance when I was growing up, when there were these beautiful Black films and filmmakers that were actually kind of blacklisted afterward, like Julie Dash, Darnell Martin, Theodore Witcher, and Ernest Dickerson, to name a few. And then, yes, around 2020 or 2019, there was another renaissance for Black film, and a lot of what maybe you can call white guilt about the systemic racism within filmmaking. People were trying to move against it, which was necessary. There was a lot more space for Black stories and for those to be told by Black artists. Now a lot of people are reverting back to their racist ways, and they’re like, We never really felt differently, and now we don’t have that same pressure, and we can go back to excluding Black and people of color from this conversation, and denying access to them. Honestly, this last year has been very difficult, even for me, to get projects made that are about people of color. Many of my projects have been dropped.

I would like to see that change. I would like to see that renaissance not be a renaissance, but just be a standard. I will continue to make room for artists of color involved in filmmaking and stills and image making, period. But I think it’s also about creating that access and us being on the other side of it. I was just talking about working on a film on Stephanie St. Clair, which I had taken to a bunch of people, and nobody was interested in making it until I took it to this Black executive who was looking for a gangster film that centered on a Black woman, and she was very excited about it—and now, we’re developing that together and getting it made. A lot of other people who I have great relationships with just didn’t see the value or the idea that that has appeal to an audience—of any color. So it’s important that we’re on the other side. It’s important that we’re creating our own platforms, so that we’re creating these opportunities, and having ownership on the business and the decision-making side of things, and are on some of these boards. Until that happens, we are relinquishing the power to control our image, which is really upsetting.

Knowles: Well, we look to you.

Matsoukas: Thanks. I mean, I’m going to keep on fighting the good fight. And I will continue standing on the shoulders of many who came before me, who fought that good fight, and be influenced by them and their work, and even stand arm in arm with my fellow comrades, you being one of them, and creating Black art, and archiving it, and creating space for other Black artists, and collaborating with each other. And, also, just being able to be a cheerleader at times and showing that there’s value to our stories and our image, and we need that. That’s what feeds us. And it’s not just us. It’s the world. I feel like, especially as African Americans, our greatest commodity is our culture, and it has been shipped around the world and appropriated, and we need to regain ownership of it. And you are very much a part of that story. One of the things I love most about you is not only your art but your appreciation for our artists and our stories and the idea that we have to own them and own that history and also protect it. That’s what we need to do.

Knowles: Yes. We can end it with the words of the great NeNe Leakes: We see each other!

Matsoukas: Exactly.

This interview originally appeared in Aperture No. 259, “Liberated Threads.”

June 5, 2025

8 Exhibitions to See This Summer