Aperture's Blog, page 10

March 31, 2025

Sally Mann’s Photographs of Girls on the Cusp of Adulthood

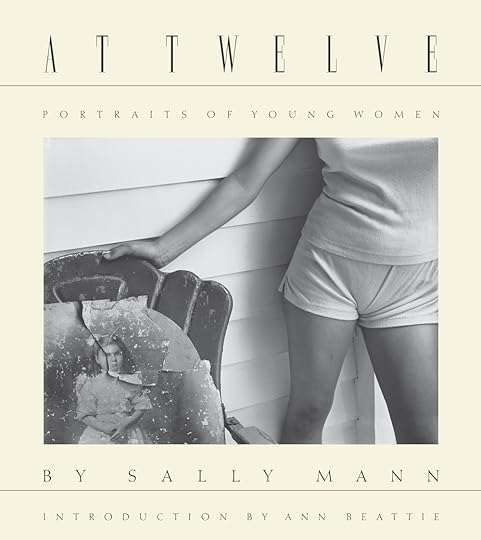

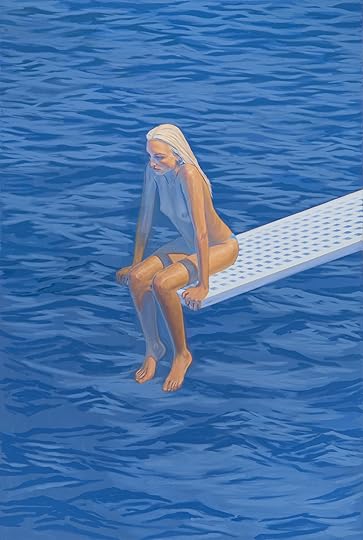

First published by Aperture in 1988, Sally Mann’s At Twelve, Portraits of Young Women is an intimate exploration of the complexities of the transition from girlhood to adulthood. Photographing in her native Rockbridge County, Virginia, Mann made portraits that capture the excitement and social possibilities of a tender age—while not shying away from alluding to experiences of abuse, poverty, or young pregnancy—and the girls in her photographs return the camera’s gaze with equanimity. On the occasion of Aperture’s reissue of the long sought-after volume, the writer Rebecca Bengal looks at At Twelve through a dozen reflections.

1.

Twelve. Auspicious and unrealized all at once. In English—on the heels of the sprinty lilt of eleven with its lucky seven-heaven rhyme—the sound of it is an awkward, monosyllabic clunk. It’s the last stop on the wheel of the clock, the year. Twelve, slant rhyming with elf, with wolf, a world of fairy tales. At twelve, still a girl, yet already preyed on by men. At twelve, split into a dozen selves.

2.

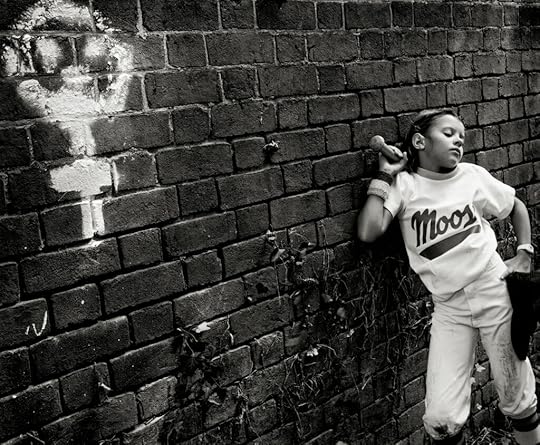

A cowgirl. A beauty queen in braces. The only girl on the softball team. Bathing suit, backyard, intransigent stare, one bare foot hooked protectively around the other. A sheath of dark bangs staring out from a painted Confederate battlefield. Businesslike in a blazer and skirt, a Persephone against a tree curiously bound with rope. In ribbons and lace, a belle perched on a patterned lounge, uncanny, unblinking, child and woman at once.

3.

Mann began making the At Twelve photographs in the early 1980s “in the odd hours … between jobs and diapers,” as she once put it (Sally Mann: A Thousand Crossings, 2018). The making of the series, first published in 1988, spans the Reagan presidency. Now the pictures speak back and forth across thirty-seven years. Three times twelve, and one to grow on.

A reissue of a decades-old work, the surfacing of images from decades before prompts reexamination, rediscovery, primes us to look for what they reveal about the era of their making, what they augur about the world we live in now.

Details of the era creep in, markers and emblems of the ’80s: hairstyles, a digital wristwatch, Calvin Klein sweatshirt on a corduroy sofa, the early-generation Nike swoosh, checkerboard Vans flung on the sidewalk, a glass liter-size bottle of Tab. But what Mann sought to make is not documentary, not a work about its time. Nor is it about these girls as individuals, though particularities of their lives enter the frame. The true subject of At Twelve is time itself, perceptions of time and youth, about being a girl, versus a woman, about the chasm between those two phases, and what it means to cross them, and what selves are lost and what selves are inhabited in that process.

I grew up four hours’ south of the place of their making, several years after, now of course long past the age her photographs have crystallized the girls in them. But when I go back to these images, I instinctively inhabit twelve again.

4.

Consider the subtitle. Portraits of Young Women. Twelve, not yet a teenager, but already a young woman? At twelve, as a girl, that is what you do, project yourself years ahead. Novels and films you don’t understand fully yet, but also do. Eavesdropping. Watching. Project yourself, because the world is already projecting, seeing you as it chooses if you let it. Portraits of Young Women, because the pictures try on other, possible selves.

For instance: Draped over the hood of a car, DOOM drawn in the dirty finish. Arms flung around her mother, eight months along in the summer heat. Arms flung around herself, a shield against the make-out scene behind her. Among the clotheslines neatly hung with the jeans of eleven other siblings. Camouflaged in flowers. Caught in a spray of light, languid and also precarious on a swinging footbridge, water rushing below. Showing how her mom’s boyfriend once pretended to hang himself from a tire swing. Only the dog (the consciousness of the picture) shows his eyes.

Sally Mann: At Twelve, Portraits of Young Women 50.00 A long sought-after reissue of an American classic, with all-new tritone reproductions.

Sally Mann: At Twelve, Portraits of Young Women 50.00 A long sought-after reissue of an American classic, with all-new tritone reproductions. $50.0011Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

Sally Mann: At Twelve, Portraits of Young WomenPhotographs by Sally Mann. Commentaries by Sally Mann. Introduction by Ann Beattie.

$ 50.00 –1+$50.0011Add to cart

View cart DescriptionFirst published by Aperture in 1988, At Twelve: Portraits of Young Women is a groundbreaking classic by one of photography’s most renowned artists.

At Twelve is Sally Mann’s illuminating, collective portrait of twelve-year-old girls, taken in the artist’s native Rockbridge County, Virginia. The age of twelve brings tremendous excitement and social possibilities; it is a trying time as well, caught between childhood and adulthood, when the difference is not entirely understood. As Ann Beattie writes in her perceptive introduction maintained from the 1988 original publication, “These girls still exist in an innocent world in which a pose is only a pose—what adults make of that pose may be the issue.” The consequences of this misunderstanding can be real: destitution, abuse, unwanted pregnancy. Within this book of portraits, many of which are accompanied by writings of the artist, the young women in Mann’s unflinching large-format photographs, however, are not victims. They return the viewer’s gaze with a disturbing equanimity.

This reissue of At Twelve has been printed using new scans and separations from Mann’s prints, which were taken with an 8-by-10-inch view camera, rendering them with a quality true to the original edition.

DetailsFormat: Hardback

Number of pages: 56

Number of images: 36

Publication date: 2024-12-01

Measurements: 9.38 x 10.88 x 0.53 inches

ISBN: 9781597114585

Sally Mann (born in Lexington, Virginia, 1951) is one of America’s most renowned photographers. She has received numerous awards, including NEA, NEH, and Guggenheim Foundation grants, and her work is held by major institutions internationally. Her many books include At Twelve (1988), Immediate Family (1992), Still Time (1994), What Remains (2003), Deep South (2005), Proud Flesh (2009), The Flesh and the Spirit (2010), Remembered Light (2016), and Sally Mann: A Thousand Crossings (2018). In 2001 Mann was named “America’s Best Photographer” by Time magazine. A 1994 documentary about her work, Blood Ties, was nominated for an Academy Award and the feature film, What Remains, was nominated for an Emmy Award in 2008. Her best-selling memoir, Hold Still (Little, Brown, 2015), received universal critical acclaim, and was named a finalist for the National Book Award. Mann is represented by Gagosian, New York. She lives in Virginia.

Ann Beattie has been included in four O. Henry Prize collections. She has received the PEN/Malamud Award for Excellence in the Short Story and the Rea Award for the Short Story, and she was the Edgar Allan Poe Professor of Literature and Creative Writing at the University of Virginia. She is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She currently lives in Maine, Virginia, and Florida.

Related Content Featured 15 Inspiring Photobooks by Women Photographers

Featured 15 Inspiring Photobooks by Women Photographers 5.

Once, as Mann recounts in her memoir Hold Still (2015), her teenage daughter Jessie gently schooled a person who worried unnecessarily how she’d feel at her mother’s art opening, out in public with a picture showing her naked body on the wall: “But that’s not me. That’s a photograph.”

The projected self is murky, a fiction. It’s a merger of the actual girl/woman, of the idea the actual presents for the photographer, of the interaction of the light and chemistry and invisible matter that transpires.

Consciously or not, the photographer seeks the twelves she might have become, those that might still exist within her. At Twelve is Mann’s second monograph, after the surreal The Lewis Law Portfolio (1977). Here she comes into her own as an artist, absorbing the influence of her mentor and friend Emmet Gowin (embracing the intimacy of the familiar) and her contemporary Nancy Rexroth (picturing the mythic in the familiar), and from numerous other masters of black-and-white photography, a stunning clarity, or what the novelist Reynolds Price described as Mann’s “serene technical brilliance.” Think of the book as a map, forking into divergent artistic paths, foreshadowing the work that would follow, the family pictures, the landscapes, the photographs of the human body altered by age and disease, decomposing and merging with the land.

6.

In the prologue to At Twelve, Mann writes that the portraits are equally about place. Lexington, Virginia, is itself an in-between; on the divide of North and South, mountains and ocean. It’s dominated by the mythic beauty of the Natural Bridge, a 215-foot geologic arch, the remains of an ancient cave, and it is soaked in Civil War bloodletting and the ruptures of colonialism and enslavement. The place where Mann had been a young girl, feral and country and clothing-averse, running down the road to chase after her family’s pack of dogs, pausing to pull hot tar from the asphalt to chew like gum. The place where she and her husband raised their three children. Twelve a natural bridge of its own. A crossing.

7.

This was her, Mick Kelly, walking in the daytime and by herself at night. In the hot sun and in the dark with all the plans and feelings. This music was her—the real plain her . . . This music did not take a long time or a short time. It did not have anything to do with time going by at all. She sat with her arms around her legs, biting her salty knee very hard. The whole world was this symphony, and there was not enough of her to listen.

—Carson McCullers, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter (1940)

Mann precedes the book with a picture of herself at twelve, and a quote from Anne Frank: “Who would ever think that so much can go on in the soul of a teenage girl?” But I think of Mick, thirteen in the Georgia of McCullers’s novel, “at the age when she looked as much like an overgrown boy as a girl,” besotted with the music of a composer she knows as “Motsart,” overwhelmed by desire. “I want—I want—I want—but what this want was she did not know.”

Carson McCullers was just twenty-three when her debut novel was published to success that overwhelmed the author as much as her character; not long after, McCullers was spending time in Lexington where, as Mann recalls in Hold Still, “she was once hauled out of a bathtub at a mutual friend’s house by my mother, drunk, drenched, and fully clothed.”

Throughout At Twelve, affixed to the photographs are Mann’s short texts, alluding to stories outside the frame: the girl who made paper flowers to line the walk to the family outhouse, who in a couple short years would’ve “gone and gotten herself a baby,” but at twelve just liked to ride around listening to the radio. Setting words to whatever music played in the heads of these girls.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

8.

In Hold Still, published nearly forty years after she began the At Twelve photographs, Mann seeks to posthumously get to know her father, a deeply private, death-obsessed Texan who’d harbored his own secret artistic desires, yet opened a medical practice and passed his camera on to his daughter. But she launched that investigation in these pictures, drawing on the connections her father made within the rural community, families whose babies he delivered. Her own drives to make her large format portraits echo a doctor’s rounds. Here are lives just a few miles from her own. Theresa, pregnant at eleven, a mother at twelve, protectively watching her baby daughter who rests outstretched on her blanket, a newborn amid a bedroom full of raggedy, well-loved baby dolls. She has, Mann’s caption tells us, “already begun to shoulder the weight of adult reality.”

9.

They pose with images of other girls and young women. On the cover of At Twelve: Torso and cocked hip in the 1980s present, a hand gestures toward an inevitably decaying photograph of another girl, late-nineteenth century maybe, a long-gone relative maybe, a crack running through her hair ribbon, down the side of her face, through the puffed sleeve of her white dress. Because the photograph shows only the midsection of the ’80s girl, we see the face of history as her own.

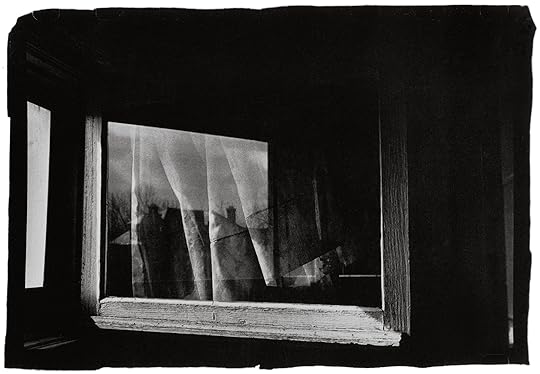

In the book’s interior: Two sisters posed against a portrait of their doppelgänger ancestors. Window reflections in the portrait, so much light the faces in it begin to dissolve as by time itself. The gaze of the sisters in the shadowy present. The portrait-within-a-portrait both a past and a future.

10.

Mann writes in Hold Still that photographs destroy memory. Some truth to that. Regardless, her At Twelve photographs also show how the camera (and time) still have the power to reveal things unperceived in the moment. It’s a testament to the strength of these pictures that, looking at them now, you can’t help but wonder how Mann didn’t consciously apprehend what lay below their surfaces. And yet, as most artists can attest, at some point the act of making work produces its own fugue state; it is not possible to see it in totality, or near totality, until later, sometimes much later. For a photographer, lost in the black vacuum under the hood of the camera, the world turned upside down and backwards in the ground glass, so many details flickering in the span of a shutter, the full picture clear only via photography’s more useful metaphors: being developed and processed.

11.

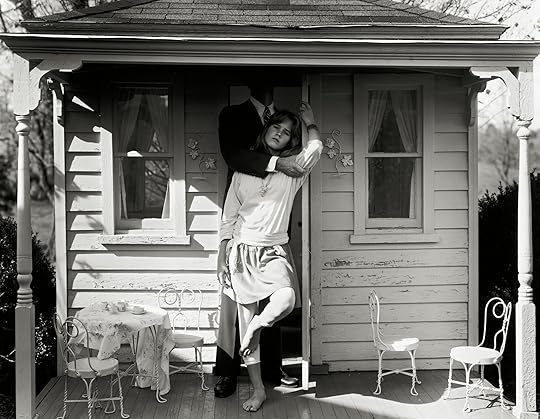

On the page laid bare: The stiffened posture, the distance a twelve-year-old refused to bridge to pose with her mother’s boyfriend. Mann’s text tells us the girl’s mother later shot him in the face; the picture, which in retrospect the photographer sees with “a jaggy chill of realization,” suggests why. On the porch of a life-size playhouse, the dark shadow of a father looms behind his daughter as he exacts an awkward and menacing grip on her arm. Unsettling, the way they both dwarf the little-girl tea-party furniture, Alice in Wonderland proportions. Mann affixes a reference from Lewis Carroll, whose own relationship with young girls was dubious. But the imprint of darkness bears out here too.

All photographs Sally Mann, from the series At Twelve, 1983–1985

All photographs Sally Mann, from the series At Twelve, 1983–1985© the artist

12.

In At Twelve, the eyes are the punctum. Mann dwells on the “knowing watchfulness” of the gazes of the twelve-year-olds in her frame, the way they disarm; how, for the photographer studying her own prints, the eyes are “sibylline, foreboding,” possessing a “direct, even provocative approach to the camera.” The eyes meet the lens, an acknowledgment: that the picture they are participating in is not-them, but also, that they have permitted something of their own selves to be seen.

In the parting frame, slouched on (her father’s?) lap around an outdoor table of adults and drinks, relaxed, faces blurred or obscured. Only hers sees and is seen fully by the camera. Her brows raised, her eyes unflinching, questioning the photographer’s stare, our own. In her eyes—in all their eyes—is the assertion of the self, the power of the self.

Looking again at these pictures we intuit how much change lies ahead for each of them, on the cusp of becoming women. And yet, also clear: how very precious little change has occurred in the eyes of men.

This is not a sociological body of work. But we are in the midst of a deeply darkening age of politics for freedom of speech, and for women, for girls, for whomever the women and girls in these portraits might identify as, and it is difficult not to view it now without also drawing a line between the repression of our own era, and theirs, to all time. The young women in these pictures understand this too.

March 28, 2025

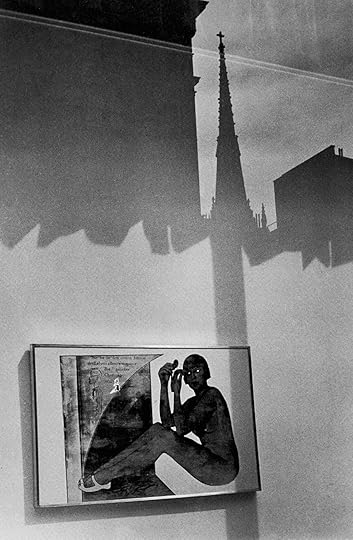

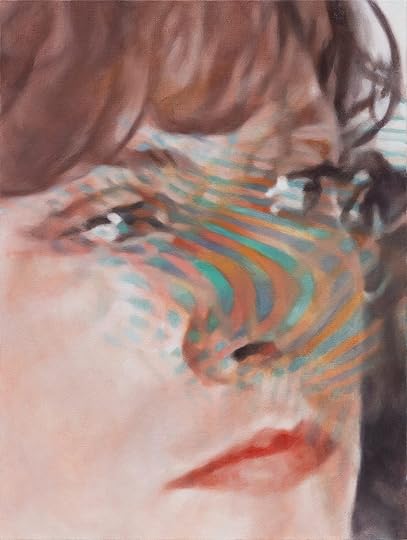

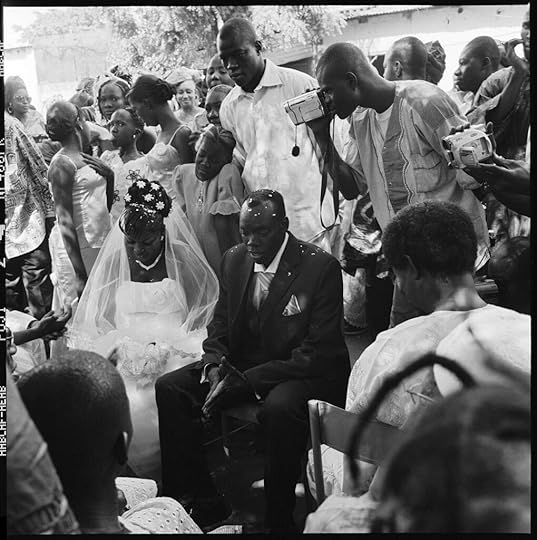

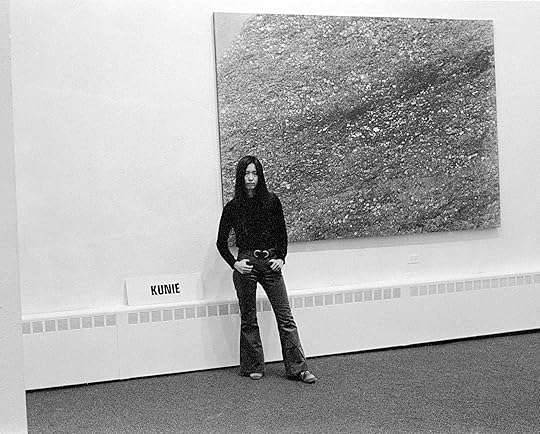

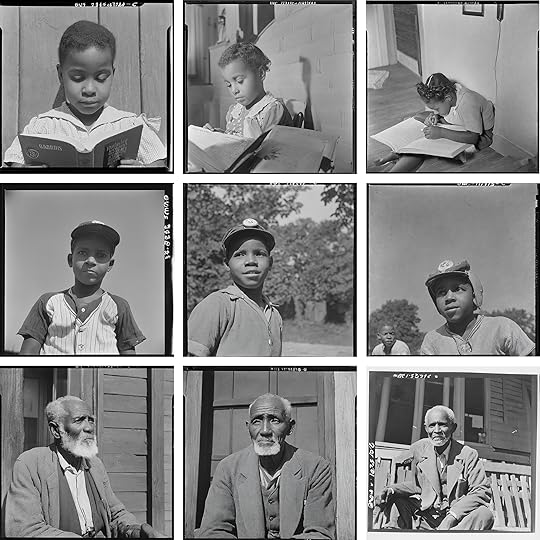

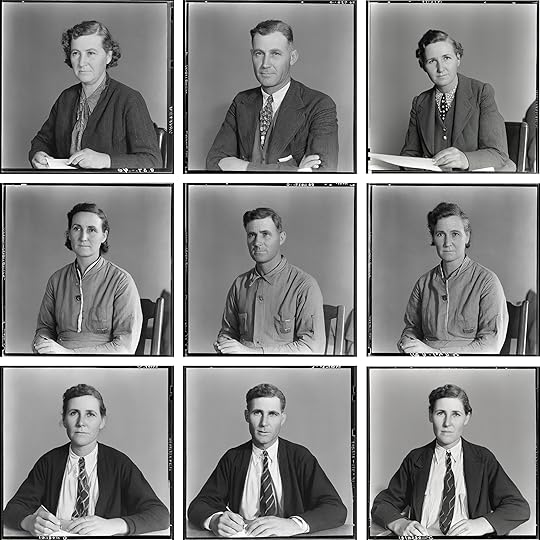

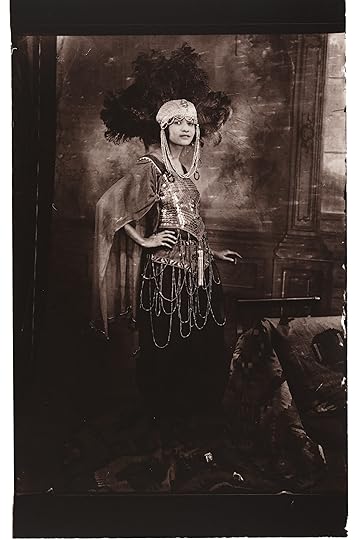

A Portrait of Ming Smith as an Artist in the Making

Ming Smith’s parents gave her a camera at a young age, and she fell in love with taking photographs. After college, she moved to New York to pursue a career as a photographer. In 1979, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, purchased several of Smith’s photographs, making her the first African American female photographer with that distinction.

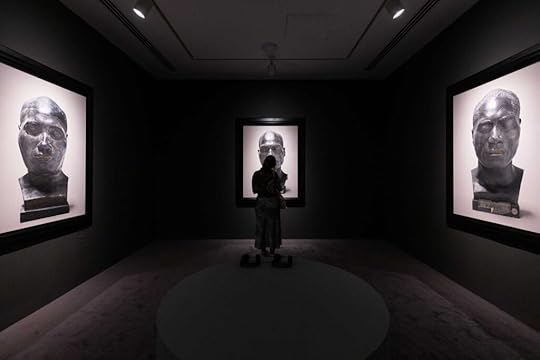

Smith’s career twisted and turned in the following decades. In 2017, a retrospective at Steven Kasher Gallery helped start a renaissance, and over the next few years, interest grew in the US and around the world, including her inclusion in Arthur Jafa’s exhibition A Series of Utterly Improbable, Yet Extraordinary Renditions at the Serpentine Galleries in London. In 2020, Aperture and Documentary Arts published Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph. Since then, Smith has had a plethora of solo and group exhibitions, including the fall 2024 extravaganza that could be called “Ming-a-palooza”—four glorious presentations that took place in Ohio, where Ming grew up.

Over three days, two exhibitions opened at the Columbus Museum of Art: Ming Smith: Transcendence and Ming Smith: August Moon. Ohio State University’s Wexner Center for the Arts presented Ming Smith: Wind Chime while Ming Smith: Jazz Requiem – Notations in Blue was on view at the Gund at Kenyon College. Other highlights from recent years include the solo shows Projects: Ming Smith at MoMA and Ming Smith: Feeling the Future at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, and numerous group shows at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, and Paris Noir: Artistic Circulations and Anti-colonial Resistance, 1950–2000 at the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

In this interview, originally published in Smith’s Aperture monograph, we learn about the many ways in which Smith was a pioneer in photography, including being both the first female to join the Kamoinge Workshop, the Black photography collective, founded by Roy DeCarava and Louis Draper, and the first African American woman to have photos purchased by MoMA. Perhaps, most importantly, Ming talks about chasing the light—something she has done her whole career, and continues to do all over the globe, stealing away in free moments or rolling down a back-seat car window and taking photographs on the way to an opening. What fuels Smith is her unquenchable desire to chase the light until she has seemingly defied time, making it stand still, taking the shot that she sees in her mind’s eye, the shot that’s ready to share with the world.

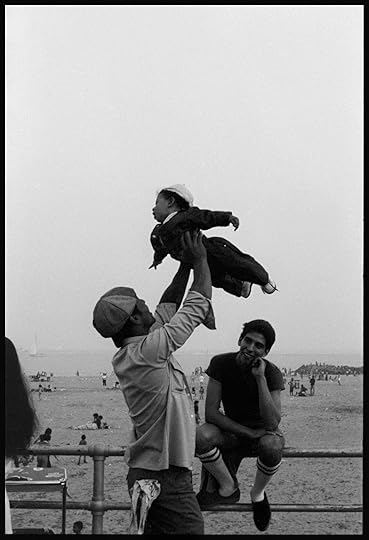

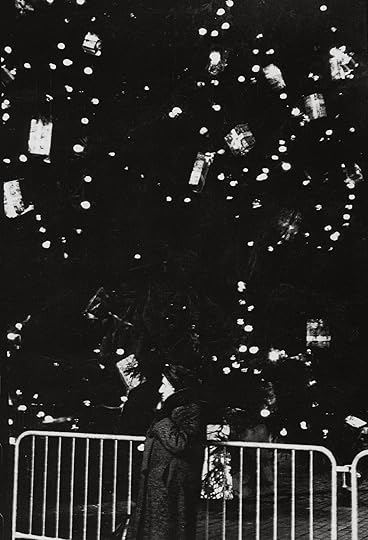

Ming Smith, West Indian Parade, Brooklyn, 1973

Ming Smith, West Indian Parade, Brooklyn, 1973  Ming Smith, Jump, Harlem, New York, 1976

Ming Smith, Jump, Harlem, New York, 1976 Janet Hill Talbert: When did you first start taking photos?

Ming Smith: My dad earned a living as a pharmacist, but he really was an artist. He did watercolors, linoleum cuts; he carved wood sculptures. He made home movies, and he was also an amateur photographer. And, of course, my mother would join in and share his world. He bought my mother a camera, a Brownie, but she didn’t use it much. It just hung in the closet. So, on my first day of kindergarten, I asked her if I could take it with me to school, and she let me. I took photos that day and I carried them around with me for years, but I lost them somewhere in my move to LA.

Talbert: You were born in Detroit and grew up in Columbus, Ohio. Tell me about your childhood.

Smith: I grew up in a culturally rich environment. My grandparents met at college. My grandmother was a teacher, but in Columbus she wasn’t allowed to teach—Black or white students—I’m not sure if that’s because she was African American or because she was married. Although he went to college, my grandfather worked as a postman—which was one of the few good jobs Black men could have back then. He and my dad each owned their own homes, and there was great pride in the fact that the homes had garages, gardens, and vegetable gardens, all lovingly maintained. Every fall my parents would plant a hundred tulip bulbs in our yard; and every spring a riot of red tulips would bloom. My grandparents grew all kinds of things—pastel pink peonies, fragrant lilacs, fascinating morning glories, and green bushes called Juniperus x pfitzeriana. I remember crickets chirping, fireflies, train whistles, and my grandmother sitting on the front-porch swing reciting poetry—Longfellow’s “The Song of Hiawatha”— along with my grandfather and other seniors, who would recite their favorite Paul Laurence Dunbar poem. My father also recited Shakespeare, “To be, or not to be . . .”—signifying nothing.

I was a quiet child, a loner—always in my own world. When everyone else was watching TV, I would be upstairs in my room alone, reading, drawing, coloring, making dolls, or outside jumping rope until the bats came out. But my grandfather was a breath of fresh air to me. He was the one who taught me about color. He was a postman, but he also painted the exterior of houses, and he had a thing about color. The colors he would paint on a house, on the trim, would delight him, and he would say to me, “Look at that color, really look at the color. Look at the whole house and then each part, each color.” I started to become aware of color, and color combinations. I became aware of different hues of color. I used to ask my relatives, “What’s your favorite color?” My father’s was blue. My grandfather and mother both liked red. My grandmother’s favorite color was yellow, and her favorite fabric was yellow dotted swiss, and that’s the name of one my photos. And when I married David Murray, a jazz musician, the fabric of my dress was yellow dotted swiss.

I loved my grandfather, and he’d always chuckle and say, “You’re my first grandbaby!” When I was about eleven, he took me on my first trip to New York, along with his youngest grandchild, a boy, as well as a daughter, who still lived at home. On another trip, he took us to the Paul Laurence Dunbar House in Dayton, Ohio. My grandparents weren’t wealthy, but they were aristocratic in nature. Education and culture were important to them, and that’s why I was going to be a doctor, because that was my grandfather’s dream for me.

Ming Smith, Self-Portrait, ca. 1988

Ming Smith, Self-Portrait, ca. 1988Talbert: You mentioned your early photos and drawings—do you still have any of them?

Smith: My mother was constantly throwing things out because my dad was a “collector,” so when I went to college, she threw away my drawings, and even some awards I’d won. I thought she’d thrown away everything, but after she died, we were going through her things and I found a box that said “Ming”; it was an old Kodak photo box, and it had a few of my early photos. Inside, I found a photo I’d taken of some girls who were my classmates. I was about ten, and we were in Columbus, Ohio. My mother also saved some photos that I’d taken while I was in college at Howard. One weekend, a friend and I had driven to New York and I took some photos in Washington Square Park. I would have completely forgotten that excursion if my mother hadn’t saved the photos. One’s pretty good, so I’m glad she saved them.

Talbert: You went to Howard University in Washington, DC, and you were pre-med and graduated with a BS in microbiology. At the time, Howard only had one photography class, and you took it.

Smith: I was always taking photos, so I took Howard’s only photography class. One day, I asked the instructor if I could earn a living doing photography, and he said that I could be a medical photographer, or I could photograph machinery. That was it. Those were the two options, and neither of those things appealed to me. So I was kind of lost, but I was still passionately taking photographs. At one point, I met the campus photographer, who said he would process my film for me. I gave him about a hundred rolls of two-and-a-quarter film, but I never saw the film again.

Talbert: After Howard, you moved to New York and became a model to support yourself. There are lots of misperceptions about you and your career, and I think it’s important to establish the fact that you weren’t a model who became a photographer, but a photographer who supported herself as a model.

Smith: I didn’t call myself a photographer, but I was constantly shooting. I was also dancing and modeling, but I didn’t define myself as a dancer or a model. I was just a young person in New York trying to find my way, and I had to support myself, so I took a job as a model. August Wilson worked as a dishwasher, and many other people take jobs to support themselves while they’re pursuing their art.

Ming Smith, Brown-Skinned Model and Steeple, New York, 1971

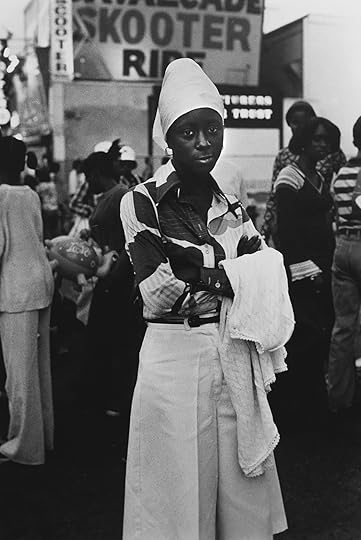

Ming Smith, Brown-Skinned Model and Steeple, New York, 1971  Ming Smith, Instant Model, Brooklyn, 1976, from the series Coney Island

Ming Smith, Instant Model, Brooklyn, 1976, from the series Coney Island Talbert: Nevertheless, because you were a model, and a beautiful woman, it seems that society assigned labels to you. In 1973, you joined the Kamoinge Workshop, a New York–based group of photographers. You were the only woman in the group. In the 1973 Black Photographers Annual, the first publication in which your photographs appeared, a text noted that you had started taking photos the year before, when in reality, you had been shooting since you were five. Can you talk about how you got into Kamoinge?

Smith: I was on a modeling job and I was sent to Anthony Barboza’s studio. As I was waiting in the foyer, I overheard some men talking—or rather, debating—about photography: was it an art form, or was it just nostalgia? I was fascinated. Every time I went to Barboza’s studio, I learned a bit more. Barboza was a commercial photographer, and people used his darkroom, so there were people coming in and out all the time. It was a meeting place, a hub of creativity. And that’s how I met Lou Draper and Joe Crawford. Lou was the one who invited me to join Kamoinge, and Kamoinge was my introduction to photography as an art form. That was a major awakening.

Talbert: Kamoinge gave you a framework?

Smith: Yeah, it let me know that there were fine-art photographers out there. There was a lot I didn’t know. I didn’t know about Roy DeCarava, one of the pioneers who got together and started Kamoinge in 1963. When I joined in the early ’70s, I did some research, and it seemed logical that these men, this group of Black male photographers, wanted to take control of their own images—their humanity—and not see stereotypes, or someone else’s propaganda about them. That was radical.

Talbert: It was also radical that you were the first woman to join Kamoinge.

Smith: People ask me, “How did it feel to be the first woman in Kamoinge?” But I never dealt with that at all. I just never dealt with it. I was just an artist, a photographer. And I think that within any profession, the way you carry yourself has a lot to do with everything. Everything.

Talbert: So what did you learn from Kamoinge?

Smith: Kamoinge was about the critique, but I also learned about lighting. I learned about W. Eugene Smith, even though I had seen a few of his images before. Lou worked for him; he used to print for Eugene Smith. So Kamoinge opened up the entire world of photography for me.

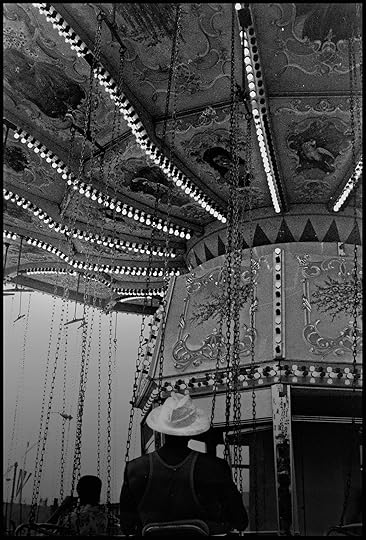

Ming Smith, Oopdeedoo, Brooklyn, 1976, from the series Coney Island

Ming Smith, Oopdeedoo, Brooklyn, 1976, from the series Coney Island  Ming Smith, Coney Island Detailed, Brooklyn, 1976, from the series Coney Island

Ming Smith, Coney Island Detailed, Brooklyn, 1976, from the series Coney Island Talbert: Kamoinge was about both critique and technique?

Smith: Yes, and a few other things, like setting up group shows. But the main thing was, you would bring your work and put it up on the wall and everyone would critique it. And they could be really cold—cold-blooded. I remember the first time I showed one of my photographs, someone said, “I don’t see that there’s anything to that photo—it’s just a photograph of a baby.” That was my first critique. But Lou Draper was the one who said that I was a really good photographer; in fact, he’s the reason why I had a show at Kasher (Steven Kasher Gallery retrospective, 2017). The first time I went to Kasher Gallery was to hear Lou Draper’s sister. She was giving a talk connected to Lou’s posthumous 2016 exhibition. I got very emotional while she was talking, because I loved Lou. He was a humble, kind, and nurturing man.

At Kamoinge, I also learned about printing, and what type of paper to use. I printed in college, but I didn’t know a lot about print quality. So I developed my sense of what I wanted the print quality to be. Technique is important, you have to have tools to build a craft, just like with acting or dance. It’s really about the artist and what they do with their tools. Because there are some folks who are fine technicians, fine photographers, but I’m not moved by their work.

Talbert: Did Kamoinge give you a sense of community?

Smith: It was a community, but eventually I didn’t really hang out with them. I was too much of a loner. I didn’t live in Harlem. I lived in the West Village. I had another life because I was modeling, so my friends were mainly in that industry—fashion designers, other models. But I wasn’t really deep into either of those lifestyles. When I was living in the Village, I became friends with photographer Lisette Model and her husband, Evsa. Lisette taught Diane Arbus. I learned about Katherine Dunham, and I started to dance. I learned about ballet mistress Syvilla Fort. So I was in a lot of different worlds. I liked to poke my head in and poke my head out—kind of like what I do with my lens.

Ming Smith, The Window Overlooking Wheatland Street Was My First Dreaming Place, Columbus, Ohio, 1979

Ming Smith, The Window Overlooking Wheatland Street Was My First Dreaming Place, Columbus, Ohio, 1979  Ming Smith, Aunt Ruth, Columbus, Ohio, 1979

Ming Smith, Aunt Ruth, Columbus, Ohio, 1979 Talbert: Many of your photographs have a lyrical, dreamy quality. One of your early images is called The Window Overlooking Wheatland Street Was My First Dreaming Place (1979). What were you dreaming about back then?

Smith: When I was a kid, I was a good student, but my teachers would frequently say on my report card, “She’s always daydreaming,” or “She daydreams too much.” But I loved school. I loved being away from home.

Talbert: Why?

Smith: My father was really strict, critical, and he had high expectations. He was a very disciplined kind of person. I wasn’t relaxed around my parents. At a very young age, I saw a lot of pain in people—in my father, in my mother, in my family.

Talbert: Do you think that taking photographs was a way of escaping that pain, or releasing it, or processing it?

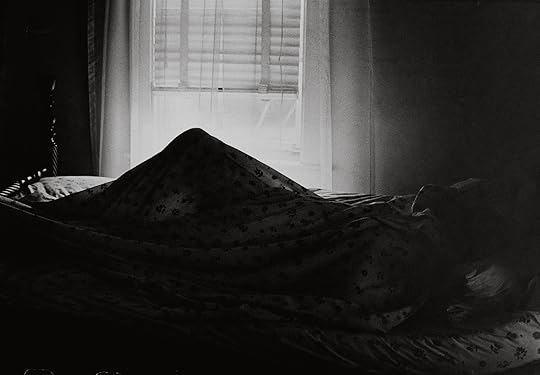

Smith: I guess it was just a way of . . . surviving. My aunt suffered from depression. In one of my photos, Aunt Ruth (1979), she’s in bed but you can’t see her; you only see her form under a sheet. But just seeing her in bed with the covers pulled over her head, that could represent all kinds of feelings of depression, oppression, fear, and the doubts in myself—things I’ve experienced. But because I can look at the photo, I am reminded of the pain, acknowledge it, but also keep moving.

A lot of women in my family were very strong. They were rebellious, they were definitely feminist in their own way, and many didn’t ever fit in. They were on the outside. So there was a lot of pain. And I was aware of that, because not only did some not fit in, some didn’t survive, and it seemed to me that their lives were tragically wasted. One committed suicide. Another was in and out of a mental institution. And others suffered nervous breakdowns. A lot of the women were very, very smart, and they weren’t just going for the “okeydoke”—meaning what was expected of them or acceptable at the time. Yet they didn’t survive.

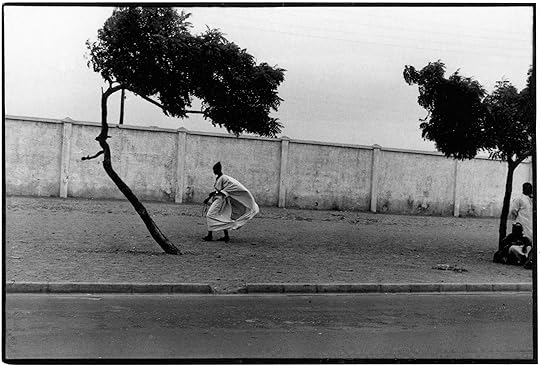

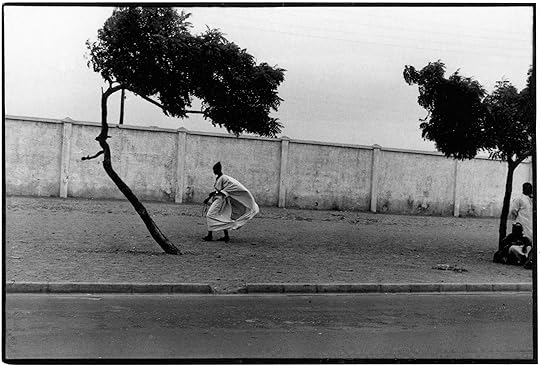

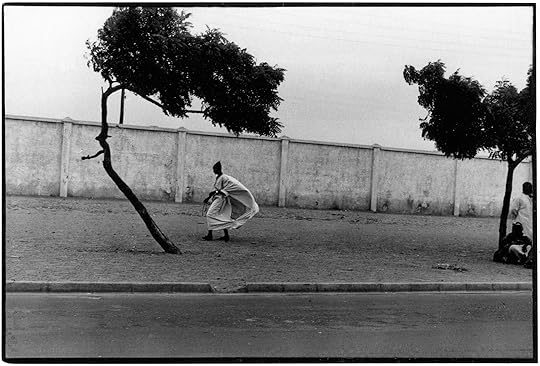

Dakar Roadside with Figures, Senegal, 1972 3000.00 Collect this iconic limited-edition print by Ming Smith, known for her lyricism, blurred silhouettes, and dynamic street scenes.

Dakar Roadside with Figures, Senegal, 1972 3000.00 Collect this iconic limited-edition print by Ming Smith, known for her lyricism, blurred silhouettes, and dynamic street scenes. $3,000.0011Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

Dakar Roadside with Figures, Senegal, 1972 $ 3000.00 –1+$3,000.0011Add to cart

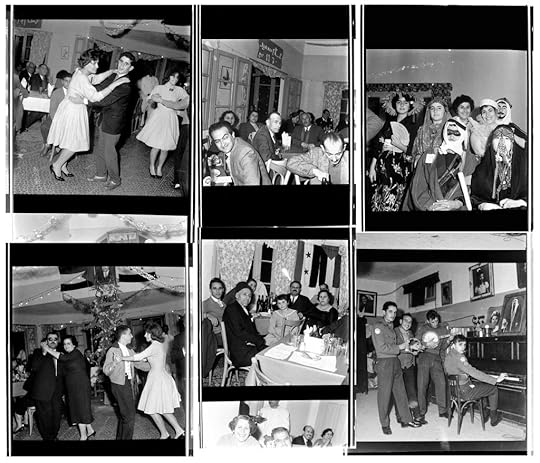

View cart Description Aperture is pleased to present an exclusive limited-edition print by Ming Smith, which is featured in Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (2020). The monograph is the first to bring together four decades of the artist’s work, celebrating her trademark lyricism, distinctively blurred silhouettes, dynamic street scenes, and deep devotion to theater, music, poetry, and dance. This iconic image of a man seen from a distance captures the essence of Smith’s artistic vision, exuding momentum and spiritual energy. The edition is limited to thirty signed and numbered copies and five artist’s proofs. Proceeds from this print sale directly support the artist as well as Aperture’s publishing, educational, and public programs. DetailsDakar Roadside with Figures, Senegal, 1972

Edition of 30 and 5 artist’s proofs

Archival pigment print

11 x 14 in.

Signed and numbered by the artist

Price to increase as edition sells

*Please allow two weeks for orders to ship

About the ArtistMing Smith was born in Detroit and raised in Columbus, Ohio. A self-taught artist and former model, in the 1970s, she published her early work in The Black Photographers Annual. Smith’s work has been collected by and presented in major museums, including the Museum of Modern Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, and Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York; Brooklyn Museum; National Museum of African American History and Culture, and National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC; and Serpentine Galleries, and Tate Modern, London. Beginning in 2017, her work was included in the celebrated traveling exhibitions We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85 and Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, as well as in Arthur Jafa’s exhibition A Series of Utterly Improbable, Yet Extraordinary Renditions, which traveled from London to Berlin, Prague, Stockholm, and Porto, Portugal. In 2019, Smith’s solo exhibition with Jenkins Johnson Gallery was awarded the Frieze Stand Prize at Frieze New York. Smith lives and works in New York.

Talbert: That’s powerful. You’ve talked about survival before. In your conversation with Arthur Jafa connected with his 2017 exhibition A Series of Utterly Improbable, Yet Extraordinary Renditions, which featured your work almost like a solo show, you mentioned the importance of thriving, and not just surviving. Some of your female relatives didn’t survive, but you survived through photography.

Smith: Part of getting through life is riding the tides. It takes effort, and I’m glad I kept going. When I was premed, I didn’t want to be a doctor. I was constantly taking photographs, but I never told anyone I had dreams of becoming an artist or a photographer, even when I came to New York.

Talbert: When did you finally declare yourself an artist?

Smith: When I started getting my first paycheck! [Laughs]

Ming Smith, David Murray in the Wings, Padua, Italy, 1978

Ming Smith, David Murray in the Wings, Padua, Italy, 1978  Ming Smith, Christmas Constellation, Brussels, 1978

Ming Smith, Christmas Constellation, Brussels, 1978 Talbert: What was your first paid job as a photographer?

Smith: Well, it wasn’t really a paycheck, but in 1979, when the Museum of Modern Art purchased two of my photographs (David Murray in the Wings, 1978; and Christmas Constellation, 1978), that was a validation. I thought my work was good—this wasn’t egotistical, because the conversation was between me and my work, no one else. But it was great to be validated by having your work purchased by a major institution.

Talbert: You were the first African American woman to have your photographs acquired by MoMA. How did that happen?

Smith: One day I was passing MoMA and I remember saying to myself, “I’m going to be in there one day.” I didn’t dare say it to anyone. Sometime later, I heard that they had an open call and you could drop off your portfolio on a certain day of the week. On the day I arrived, the receptionist thought I was a messenger—and she treated me like one. When I went to pick up my portfolio a few days later, the same receptionist told me to have seat, because the head photography curator, John Szarkowski, wanted to meet with me. The curator Susan Kismaric escorted me into a room where eight of my photographs were placed on a tabletop. Kismaric said that John loved my work, but they could only purchase two for their collection, and she made me an offer. It wasn’t even enough to cover my expenses—and I told her that. She said, “What! People try to give us work!” She couldn’t believe I wasn’t happy and was hesitant to accept the offer, but she gave me the weekend to reconsider. When I told my husband, he said take the money.

Talbert: Let’s talk about your technique.

Smith: Dealing with light is the main focus and attraction. I do a lot of night shooting, and even in the dark, I look for the light—the way light comes in. In all my work I improvise with light, with what’s there. I feel my way through things, and I let the spirit guide me. When I’m shooting, I usually have a sense: “This is the photograph that I’m going to print. This is the moment.” I kind of always sense that, but I continue to shoot anyway, because a lot of times you’re just shooting and grabbing moments—so you don’t really have time to do any editing in your mind, but sometimes you just know, “This is the shot.”

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Talbert: It’s a feeling that you have?

Smith: Yes, a feeling, and that’s the turn-on for me—photography is about the discovery. After the photo is printed and I look at it, I can define or refine the image in an artistic way. But basically, when I shoot there’s a moment that is the moment, and you kind of know that you have a good shot, at least I do.

I like catching the moment, catching the light, and the way it plays out. Because you can be focusing on an object and you know you have to hurry up, because a cloud may be coming. You know how the sun comes in and out because of the clouds? The image could be lost in a split second. I go with my intuition.

Talbert: Who are some of your influences?

Smith: Katherine Dunham, of course, and Zora Neale Hurston. Romare Bearden is my all-time favorite. But I would also say Monet, Chagall, Elizabeth Catlett, Charles White, Matisse, Roy DeCarava, Lou Draper, Gordon Parks, Lisette Model and Diane Arbus, Brassaï, W. Eugene Smith, Robert Frank, Deborah Turbeville, Sarah Moon, and on and on and on. And, of course, some of the Kamoinge members.

Talbert: Cartier-Bresson said, and I’m paraphrasing, that photographers deal in things that are continually vanishing.

Smith: It’s just being in that moment. You can’t be so much in your head. That’s why I like dance too. You have to be in the moment, you have to be right there—it’s like a form of meditation.

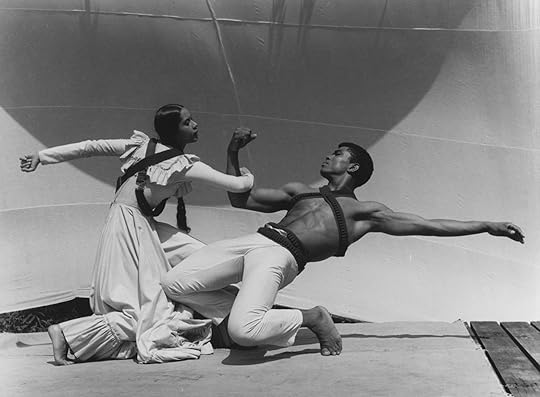

Talbert: What’s the relationship for you between dance and photography?

Smith: It’s about always looking at lines and the quality of the movement. It’s about seeking energy, breath, and light. The image is always moving, even if you’re standing still.

Ming Smith, America Seen through Stars and Stripes (Painted), New York, 1976

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }Talbert: You use many prost-production techniques, like tinting, painting, and collage. Why did you start painting your photographs?

Smith: Visually, I just wanted more. The quality of the image is the utmost important thing to me. So if I saw an imbalance in some way, I would apply paint. I didn’t want to throw away a print, but instead I wondered, “How can I make this better?”

The jumping-off point for a painter is the blank canvas. For me, the print became the blank canvas, and I wanted to explore. I wanted to see what I could do with that. I first started tinting my photos in the ’70s, but I didn’t know why. And then I remembered that my mother had had a job hand-tinting photographs. My father was furious, because I chose to go to Howard University instead of Ohio State—he would not give me a nickel, even though I was on a full scholarship. So my mother—who did beautiful embroidery—learned to tint photos from a neighbor and would slip money by mail to me to help me out while I was in college.

Some people like my photographs better with paint, some don’t. I like them both. Usually if I show a photograph, then it means I like it. Like America Seen through Stars and Stripes (1976), with the blood-red paint. That’s a good photo, but the paint adds more to our story—Deborah Willis uses the word “enhanced” when talking about my painted photos, meaning that the paint adds to the original image. The red paint in America Seen through Stars and Stripes emphasizes even more the violence that was done and is still being done to Black people. My Aunt Stella had an expression that she would use from time to time, and I remember her sitting in a chair and saying, “The things I’ve seen America do. The violence that I’ve seen them do to us . . .” She was referring to Emmett Till and moments like that. She never really said specifically, but when she said that statement, I felt it. So America Seen through Stars and Stripes comes from the feeling that I had when she said that.

Ming Smith, Sun Ra Space II, New York, 1978

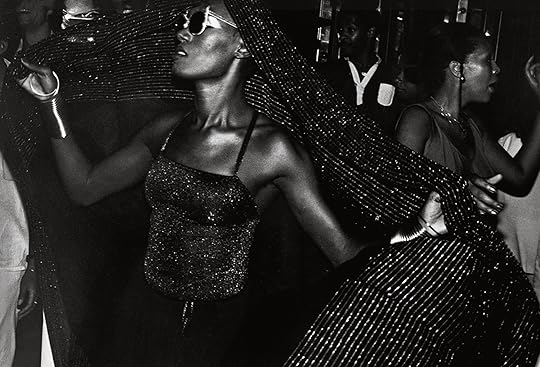

Ming Smith, Sun Ra Space II, New York, 1978  Ming Smith, Grace Jones, Studio 54, New York, 1970s

Ming Smith, Grace Jones, Studio 54, New York, 1970s Talbert: You frequently use double exposure in your work.

Smith: I had a photo of James Baldwin. I didn’t want a mediocre photograph of him, because he’s grand. He’s huge. Genius. He’s one of our most beloved icons. The same with James Van Der Zee. So I thought, Why not put them in the skies of Harlem? Because Baldwin and Van Der Zee are a part of who we are as a people. They are part of us, part of Harlem, part of our ethos.

Talbert: You were married to jazz musician David Murray, and music is important to you and your work. You’ve made photographs of musicians and entertainers. What was your introduction to jazz?

Smith: I had an older cousin, Eugenia, who I was very close to. She was brilliant. She had a pharmacy degree and a doctorate of psychology. She was so good to me. Eugenia’s style reminded me of Lorraine Hansberry. One day when I was about twelve, we were riding in her car from Detroit up to Ann Arbor, where she lived, and a song came on the radio. When I asked her, “What’s that?” she said, “That’s jazz.” And later another song came on and I said, “What’s that?” and she said, “The blues.” Then she asked me, “Which do you like better, jazz or blues?” And I said, “The bluuues!” drawing out the word. And she just laughed, but it was also a way of affirming me, like, “This girl is smart, she’s hip, she knows! She knows what’s going on.” But it was true! I really love the blues.

I think photography is mystical, spiritual, magical. It really is.

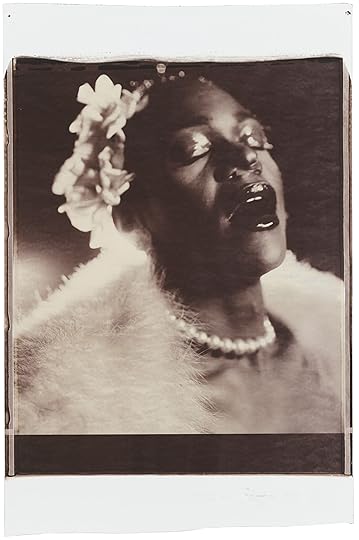

Talbert: How would you say the blues informs your work?

Smith: If people could feel what I feel when I hear a Billie Holiday song—that’s what I would want them to feel when they look at my work.

Talbert: You’re largely self taught; how did you learn?

Smith: I took photos. I photographed. If a writer wants to write, they’ve got to write. If someone wants to paint, they’ve got to paint, right? It’s in the doing of it, the repetition of it. Then the conversation is between your work and you. It’s not about anybody else. It’s just you and your work. That’s the way to develop as an artist. The answers are not on the outside. Part of me sticking with photography is that I could look at my work and see if it was good or not. I didn’t care what anyone else said. In modeling and dance, there was always someone scrutinizing me, but with my photography, I held myself to the highest scrutiny. I decided if my work was good or not.

Toni Morrison was a mother, and full-time editor, and she would get up early in the morning before she went to work—three or four hours early—so she could just write. She had commitment, discipline. She was discovering herself as a writer. It’s the discovery, the exploration of being an artist and doing the work. That’s the essence of it: your voice or your vision must come from you. It’s in the doing of it. It’s the trip along the way. That’s where the real work is. That’s when the talent comes through.

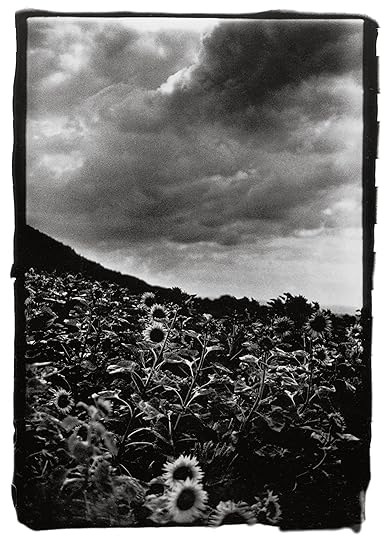

Ming Smith, Goghing with Darkness and Light, Sunflowers, Singen, West Germany, 1989

Ming Smith, Goghing with Darkness and Light, Sunflowers, Singen, West Germany, 1989Talbert: There’s a tendency to pigeonhole African American artists into particular locales, but you’ve traveled extensively and taken photos around the world. In a sense, you’ve chased light in many places on the globe. Can you talk about your photo Goghing with Darkness and Light, Sunflowers (1989), about the light on that particular day?

Smith: In 1989, I was in Germany traveling in a van [with the David Murray Octet] and my sons, Kahil and Mingus. We were passing fields and fields of sunflowers and I said, “Excuse me, we’ve got to stop! I just need to take this shot! Give me two minutes. I just need to stop and take this photograph.” And they did stop, because we’d been traveling for twelve to fifteen hours, and for me to ask one time to stop didn’t seem too much to ask. I was used to doing my work on the side, or in between. But when I saw that field I thought, “Of course, van Gogh is going to paint sunflowers because that field of sunflowers was the most beautiful scene.”

Talbert: How long did you stop?

Smith: I jumped off the bus and quickly took some shots, and that’s why it’s called Goghing with Darkness and Light, because we were on the go, and the sky was heavy with clouds, just like van Gogh’s light.

Talbert: Do you have any other moments like that that you remember vividly? Moments that you absolutely had to capture?

Smith: Years ago I was in Japan, again traveling with David, and I saw dewdrops on a tree and a full moon. It had been a full day. My husband and I had taken our son Mingus to the Japanese Disneyland. We had been in the studio with David. And now it was early evening and it was starting to rain. We’d been out since about seven o’clock in the morning, plus we had jet lag. I said, “I want to shoot this tree.” And David said, “O, no, do we have to stop?” And Mingus said, “O, Mommm! Do we have to?” [Laughs] We were very close to where we were staying, maybe a half a block, and I said, “Just go; go home.” So I stopped and took the photograph. I was tired, I didn’t feel like dealing with them saying, “O, come on, what are you doing? Do we have to wait for you?” [Laughs] I’d spent all day long doing everything that David wanted to do, and after that, everything Mingus wanted to do, and they didn’t want to wait a few minutes while I took a few shots. But I’m glad I asserted myself, because the images are still alive and treasured after thirty years.

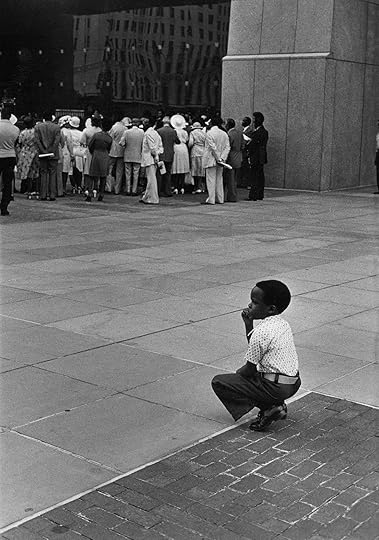

Ming Smith, What’s It All About?, Harlem, New York, 1976

Ming Smith, What’s It All About?, Harlem, New York, 1976  Ming Smith, Amen Corner Sisters, Harlem, New York, 1976

Ming Smith, Amen Corner Sisters, Harlem, New York, 1976 Talbert: Your career started in the 1970s, and then you had a show in 2000, twenty-five years later, in LA [at Watts Towers Arts Center] that was written up in the LA Times. Many other things happened in between, and recently there’s been a new appreciation—a resurgence of interest in your work. You’ve had a retrospective at Steven Kasher Gallery in New York, and your work appeared in 2017 in Soul of a Nation at Tate Modern and We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85 at the Brooklyn Museum. You’ve also shown at Frieze and Frieze Masters; and institutions including the Whitney, Getty, and National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC, as well as MoMA, have all acquired your work—and that’s just in the last few years. In the quieter times of your career, how did you keep going when your work wasn’t getting as much attention as it deserved? Were you still shooting? When did you start painting?

Smith: Going through a divorce in the early ’90s, I moved to LA. The first time I started painting, as opposed to color tinting, was on Easter 2000. Mingus was away at a basketball tournament, and I didn’t feel like going anywhere and socializing, so I had quiet time. But almost everything that I’ve ever created came from my quiet time. Even when I was married and on the road with David, I would leave the family in bed and I would go out and shoot, and by the time I returned, they were getting up.

Talbert: When it’s quiet.

Smith: Quiet. No distractions—versus distractions, like I’m painting and all of a sudden someone says, “Will you fix me a sandwich, or spaghetti?” just when I was in the middle of my thought. [Laughs]

Talbert: When you look back at your career thus far, what were the highlights? Do you have any regrets?

Smith: Well, of course, being in MoMA was the highlight, and being in We Wanted a Revolution. I was really happy to be included. Those were the two main highlights. But actually, it’s being acknowledged for my work.

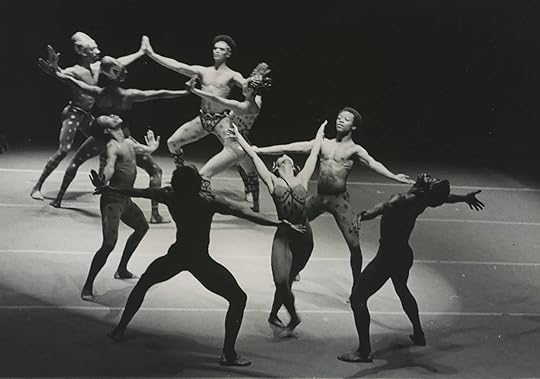

In 1981, I was in a show called Artists Who Do Other Art Forms at Linda Goode Bryant’s gallery, Just Above Midtown (JAM). I wasn’t really part of that scene, but I remember when Linda called and asked me to be in the show, I just said, “Sure.” She had heard I was a dancer too. In front of my installation, I danced and David played the saxophone, and my photographs were projected onto the wall, flashing in the background. Someone videotaped it, but I never received a copy. Someone somewhere has that tape . . . Because I was dancing, I wasn’t able to photograph, but I recently found a slide from that night. For the most part back then, I was shooting without getting any compensation or acknowledgment. So I was lucky to be a part of JAM, along with other artists, like David Hammons, Dawoud Bey, and Howardena Pindell.

Talbert: It goes back to your belief about doing the work. Being in that show was just part of doing the work.

Smith: And I was in complete support of Linda! A Black woman? Starting her own gallery? Linda Bryant had a dream.

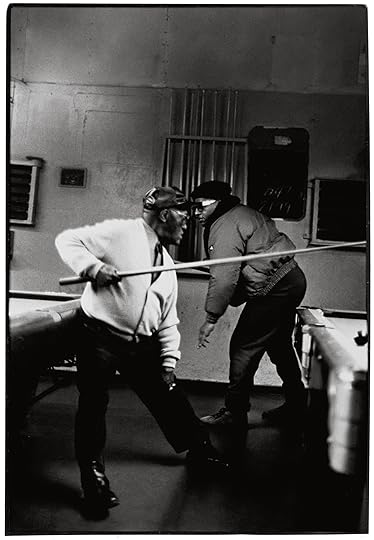

Ming Smith, Two Pool Players, Pittsburgh, 1991, from the series August Moon for August Wilson

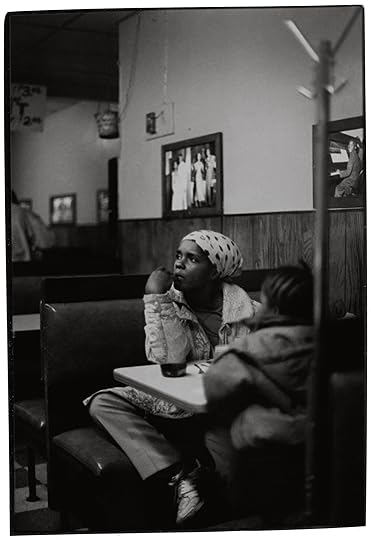

Ming Smith, Two Pool Players, Pittsburgh, 1991, from the series August Moon for August Wilson  Ming Smith, Mother and Child Deciding, Pittsburgh, 1991, from the series August Moon for August Wilson

Ming Smith, Mother and Child Deciding, Pittsburgh, 1991, from the series August Moon for August Wilson Talbert: You have about fifty to sixty photos that make up your series August Moon for August Wilson (1991), and you’ve talked about turning them into a book similar to The Sweet Flypaper of Life (1955), which had photographs by Roy DeCarava and text by Langston Hughes.

I just love that book. It was my inspiration. After I saw August Wilson’s play Two Trains Running (1990), I wanted to go to Pittsburgh and shoot. His characters were characters I knew and loved. In Pittsburgh, the people were light to me. They were light within all the violence and all of the pain. They were folkloric.

Talbert: Some of your photos have appeared on album covers.

Smith: I did some album covers for David, but also for the World Saxophone Quartet (WSQ). So along with the album covers, I took these beautiful photographs of the quartet and I had them framed—and framing was expensive. They were having a meeting and we took the framed photos to the meeting, and what did the guys do? They said to David, “You just want to promote your wife!” They didn’t want to look at the photos! Male egos! I hurried out of there and I was so furious, I threw them down on the sidewalk, breaking the glass.

Talbert: But the photos did make it onto the album, right?

Smith: Yes, but guess what? A year later, those same guys asked me, “Do you have a free PR photo we can use?” And for about ten years after that, those photos were still being used for promotion, including in DownBeat magazine.

Arthur Jafa first discovered my work on the album covers of David and WSQ. We’d never met, but he called me after he finished the cinematography for the film Daughters of the Dust (1991) and told me how much he loved my work and was inspired by my images. We didn’t meet face to face until years later.

Ming Smith, Pharoah Sanders at the Bottom Line, New York, 1977

Ming Smith, Pharoah Sanders at the Bottom Line, New York, 1977  Ming Smith, “Transcendence, Turiya and Ramakrishna,” for Alice Coltrane, 2006, from the series Transcendence

Ming Smith, “Transcendence, Turiya and Ramakrishna,” for Alice Coltrane, 2006, from the series TranscendenceAll photographs courtesy the artist

Talbert: Your Transcendence series (2006) was shot in Columbus, and many of the photographs have been enhanced with paint. Some have a little paint added to them, others are awash in paint. They are exquisite.

Smith: The title Transcendence comes from the music of Alice Coltrane. Transcendence was part of her spiritual journey, her musical journey, her life journey with her husband, John Coltrane. When I was growing up in Columbus, there was Jim Crow, the Ku Klux Klan, violence, and all kinds of injustices. Columbus, Ohio, could be very racist.

Talbert: So the Transcendence series is about elevating contemporary Columbus?

Smith: Elevating my experience of Columbus, because when I left Columbus to go to college, I said I would never go back. I didn’t have any help choosing a college. I just figured things out on my own. My high-school counselor kept saying to me, “Why do you want to go to college? You’re only going to be a domestic and scrub floors.” So I had to deal with that type of attitude. He didn’t understand. No one really understood. I used to be attacked by a little white girl almost every day on my way to school when I was in first grade. I had to pass by her house, and every day she called me the N-word. It was because the neighborhood that had been all white was becoming Black. So the Transcendence series was a way of transcending all of that, creating art out of that pain.

Talbert: Transcendence seems to be one of your long-running themes, maybe even your philosophy about photography.

Smith: I think photography is mystical, spiritual, magical. It really is. That’s what it is.

This interview originally appeared in Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture/Documentary Arts, 2020).

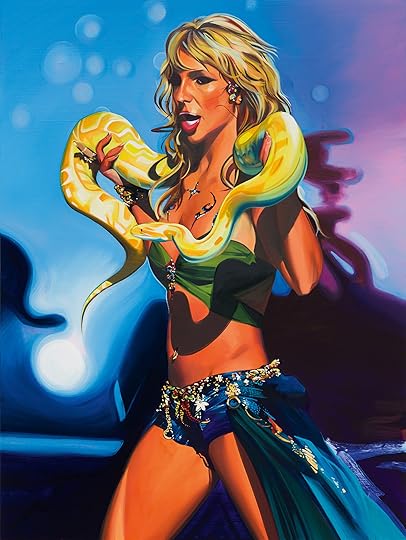

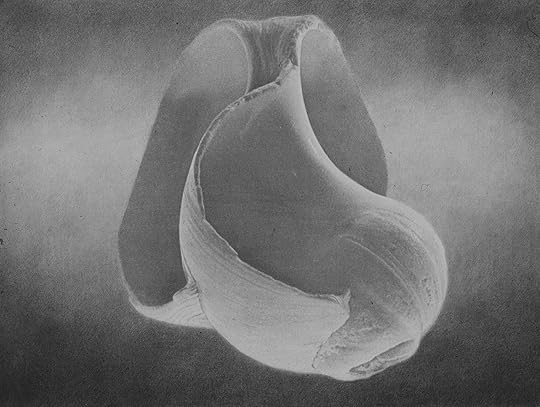

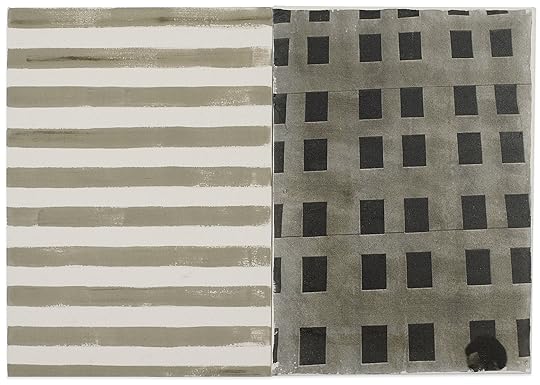

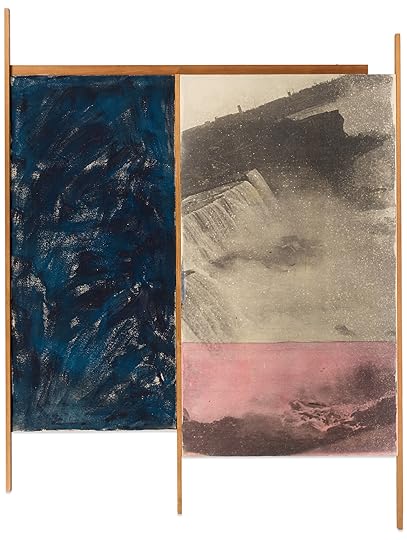

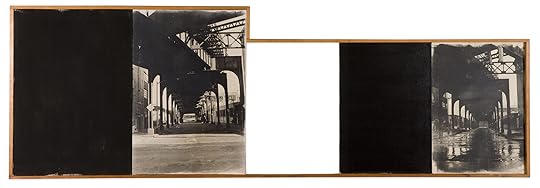

Vija Celmins Isn’t Interested in Photography

A star-streaked sky, the undulant surface of the sea, a gooseneck lamp, a glowing electric heater, the delicate architecture of a spiderweb, a Porsche cruising along a California freeway—these are some of the subjects that have captured the vivid attention of Vija Celmins. For more than half a century, the Latvian-born, US-raised artist has produced absorbing paintings and drawings that are often inspired by—and mistaken for—photographs. “The image is just a sort of armature on which I hang my marks and make my art,” she has said of her work, which is born of hallucinatory concentration and, in her view, never truly complete. Pieces are worked on and reworked, again and again, becoming less about depiction and more a record of mark making that describes the passage of time.

For Aperture’s spring issue, Celmins spoke with the photographer and her friend Richard Learoyd, who is, likewise, known for a decelerated, highly technical approach that gleans meaning from the limits of representation, in his case by using a camera obscura to create crisp, hyperreal portraits and still lifes haunted by the history of painting. The two artists discuss Celmins’s philosophy as an artist, falling in love with gray, and the rewards of slowness.

Vija Celmins with Comb (1969–70), 1970

Vija Celmins with Comb (1969–70), 1970Courtesy the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Richard Learoyd: I’ve looked at quite a bit of your pictures over the years, and it seems that photography is useful to you in some way. Do you think that’s true?

Vija Celmins: Well, you know, I am not really that interested in photography.

Learoyd: We know that!

Celmins: When I was really young and in school, I wanted to be an abstract painter, of course, because that was a going thing. I think that I agreed that the painting was about itself. But I was unable to really make the marks that were just marks, to build a space that I thought was the proper space. I couldn’t incorporate that two-dimensional plane, which is very important as a reality; it is not just a support, it is what keeps you out of the work and invites you in at the same time, because of the convention of hanging these two-dimensional things on the wall.

Learoyd: It’s a pictorial gravity, isn’t it? It’s something that draws you toward it and pushes and repels at the same time.

Celmins: Right. First of all, as you can probably tell, I’m not a big colorist. But I did try to make de Kooning paintings the best I could when I was in school because that was heroic art for me. I think I liked the fact that he was a European, that he came here, that he was sort of lost, then started all over again, and that he also had some skill in drawing. I had been drawing since I had come to the United States, not being able to speak English, and was put in school. I drew, and they left me alone because I couldn’t speak.

Learoyd: Where did you first arrive?

Celmins: We were brought by the Church World Service to the United States and put in a hotel until somebody who wanted to take in refugees after World War II signed up for us. And somebody did—unfortunately, in Indianapolis. I was nine when I came. I taught myself to speak. I used to go to the library and get first-grade books, although I could read a total book in Latvian. I was kind of a loner, which I still probably am.

Somehow, I got fascinated with art, but in a primitive way, let me tell you. I drew all the things that girls drew, like horses, movie stars. Somehow, it made a kind of life. When I was in high school, I happened to be the person that drew. If anybody needed anything, they pointed to me. I got into that mode like it was my life. So, I started getting a little more sophisticated and looking at paintings, and then I went to art school.

Learoyd: At that point, were your parents taking you to museums or galleries?

Celmins: No, no. Never been to a museum till I was in high school. I think they had a class in a museum, but I didn’t even realize what that was.

We sang all the time at home, with other people, and in the church. See, I never really understood the church. I’m not a religious person. But somehow, I stumbled into this world. I didn’t yet realize the complication of making something that you cannot explain.

Learoyd: Well, it’s the enigma, isn’t it?

Celmins: Right.

Learoyd: Which is the problem.

Celmins: Which is what we’re dealing with right here. It’s like making something that is full and meaningful but not accessible with words. You have to experience it.

Vija Celmins, Untitled (Source Materials), 1999. Iris print on paper

Vija Celmins, Untitled (Source Materials), 1999. Iris print on paper  Vija Celmins, Snowfall (coat), 2021–23. Oil on canvas

Vija Celmins, Snowfall (coat), 2021–23. Oil on canvas Learoyd: My personal experience is very different, but also similar in the fact that I was never dragged around museums and galleries and things as a kid. I was aware that those things existed, because television existed. You went to art school when you were how old?

Celmins: I got out of high school, and I got these scholarships for art school. My parents were both working and poor. I went. I found my set of people. My people who all ended up in art school because of something that attracted them, or because they were already good, or whatever. At that time, women weren’t supposed to be smart. I don’t know what the problem was in the ’50s, you know? I really liked science a lot, but it never occurred to me that I could also learn things that were very valuable, about how life turns . . . I used to catch bugs myself, and sometimes cut them apart to look at them, but I never really had that training, which is too bad. So, I was sort of funneled into the two-dimensional plane. Ha ha.

Learoyd: What I felt was that my life began when I started making photographs, because it was the only thing I was good at. I wasn’t even good at it at the time, but I was interested. And then what I found was that other adults, besides my parents, became interested in me.

Celmins: Yes. That happened, of course, to me too. My parents totally ignored me. I had to make my own relationships and so forth. When you started, did somebody give you a camera? You see, I never had a camera.

Learoyd: I used to look at magazines with pictures of cameras, and I thought they looked sort of cool.

Celmins: I like that. That’s great, thinking, What is that? You can make pictures out of this thing.

Learoyd: Yeah, they looked cool. I didn’t have a clue what to do, because I was terrible at everything. You eventually moved to LA, right?

Celmins: I moved to LA because I got a scholarship. Before that, I got a scholarship to Yale, at that summer school, where I met probably my favorite artist my own age, who was Brice Marden. He was so good right off the bat.

Then I went back to Indiana, and I tried to paint these big abstract paintings. Now they look very thin, because I never really saw the relationship of that plane. I know it sounds kind of old-fashioned, nobody thinks like this anymore.

Learoyd: What do you mean, thin?

Celmins: They were abstract blobs and lines and trying to make a structure that stayed on the canvas. Then when I went to LA, I kept that up. But I got to where I needed some other kind . . . I think I started doing landscapes.

Learoyd: What sort of landscapes?

Celmins: Oh, from California. I didn’t have enough money to buy canvas. Then I bought these big sheets of paper, and I made these drawings of LA, but they looked . . . What did they look like?

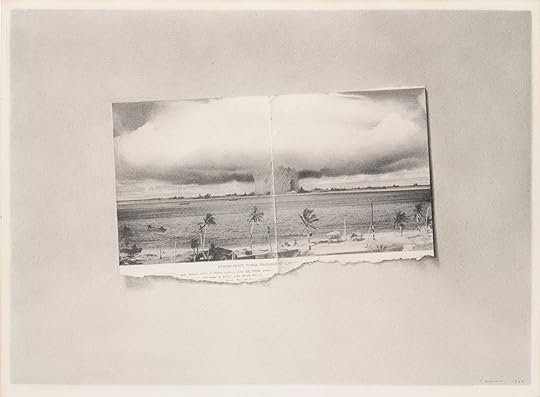

Vija Celmins, Bikini, 1968. Graphite on acrylic ground on paper

Vija Celmins, Bikini, 1968. Graphite on acrylic ground on paper© The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

Vija Celmins, Porsche, 1966–67. Oil on canvas

Vija Celmins, Porsche, 1966–67. Oil on canvas Learoyd: I saw a painting of yours. It was a painting looking out of the window of a car. I think it’s a Porsche driving down a highway.

Celmins: No, no. That was later. So anyway, in California, I veered away from doing totally abstract work because I didn’t think I could make it somehow strong enough. See, when you’re making a painting, it has to have some density. It’s a little more physical than just the photograph, I hate to tell you. The surface has so much art to play. Is it going to be a slick, dopey surface? Or is it going to be a thick, blobby surface? It has a visceral quality. I began to realize also that there was me that was not in the work— and I sort of started putting me in the work, my experiences. I started painting objects. Food. Everything.

Learoyd: The ham hock?

Celmins: I painted all the food I ate.

Learoyd: So, this is where the photographic thing comes in. Let me tell you . . .

Celmins: Wait. Let me tell you. I didn’t look at the photographs. But then, with Soup (1964), I had this bowl of soup. That actually came out of a little photograph from a housekeeping magazine.

Learoyd: But tonally, those paintings—the lamps, the ham hock—they have a relationship to photography because you’ve chosen not to overemphasize the color.

Celmins: I had this very gray studio, a long gray concrete studio. I was going to see what I could do with what I could see. But whatever you do is sort of whatever is inside you, I guess.

Learoyd: Things are gray. A lot of things are gray.

Celmins: Okay, so this is how I moved into sometimes using a photograph. I went looking for war books so I could understand what we went through, and there were very few war books at the time. This was in the early ’60s. I found a few things, which I tore out of books, and I painted some airplanes, because I used to love hearing the American bombers coming. ZzzzZZZZ. I went through this period where I tried to find a relationship to the work that was not so borrowed from what was out there. That’s when I fell in love with the grays, because the photographs were all gray for World War II. I got to painting the airplanes, seeing if I could make them fit like a painting, but still be like an object.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Learoyd: You look at a picture on the wall, and it’s either an object or a window, I guess.

Celmins: I never see a window. It’s a flat piece of paper, and it’s got a relationship in the real world in front of you. It’s a very subtle feeling that, somehow, is dimensional or flat at the same time. Then also, you try to figure out how you’re going to paint it, whether you’re going to paint it really smooth, whether you’re going to jazz it up, how are you going to handle the thing. You’ve got to remember that paint is like cheese. It’s just totally malleable.

Learoyd: All the possible permutations of what can happen with that bit of goo.

Celmins: Basically, you can’t really say too much about it without sounding a little stupid. But you’re actually making an experience for somebody. You’re not only experiencing an image, you’re experiencing the reality of the room and the flatness. I can’t stand it when things jump out of the painting.

Learoyd: We’re sitting here. We’re looking at a drawing. Could that drawing have existed without the photograph?

Celmins: I don’t know. I guess because it’s just graphite and paper that maybe it feels more like a photograph. I don’t think I could have done that kind of precise drawing without a photograph.

Learoyd: I think that people look at your drawings and paintings and think they look photographic sometimes. And when people look at my photographs, sometimes they say they look painterly, but they couldn’t be more photographic.

Celmins: You have a barrier, which is really the paper that you print on. My work can be very soft and dimensional.

Learoyd: The enormous problem with photography is its surface.

Celmins: People now look at art as if it is photography, which is also totally wrong. You have to let yourself experience how the edges are, how the thing sits.

Learoyd: There’s a weight to your work that’s often quite small. I know you’re painting bigger now. But a lot of the things were quite small. And there seems to be this sort of density of the object. Were the star drawings done from scientific photographs?

Celmins: I began to fall in love with the lead of a pencil. I have this whole thing where I got involved in space because I liked all that stuff coming back, all those images. And I used the images, and then I found these things of the outer stars and galaxies. They are not really stars. They’re galaxies. But it’s a way of pushing the pencil to the utmost degree, the very last things.

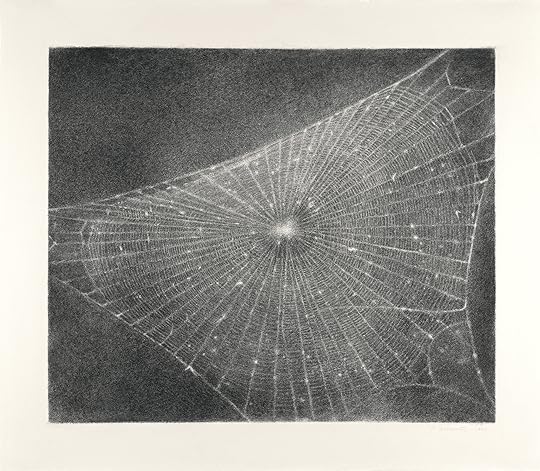

Vija Celmins, Web No. 1, 1999. Charcoal on paper

Vija Celmins, Web No. 1, 1999. Charcoal on paper  Richard Learoyd, Looking away from Lacock, 2013

Richard Learoyd, Looking away from Lacock, 2013© and courtesy the artist

Learoyd: And what about the spider webs?

Celmins: Oh, the spider webs? Well, I thought that I was sort of like a spider myself. I found these little books of spiders, and I thought, I’m like the spider myself, taking all the things. These were also all drawings. Then, did I do a painting of the spider web? I think I tried one. I liked the pencil.

Learoyd: Well, you can just pick it up.

Celmins: I probably liked it because I didn’t like sloshing around. And then finally, I said to myself, I have to start painting. By this time, I moved to New York, thank goodness, because the audience was more sophisticated here, and there were more museums, and there was more of a supporting group. I finally had to let go of the pencil and say, I’m going to pick up the brush, because it’s capable of doing a much more dimensional thing. When you’re looking at something, you’re actually looking at an object. You can’t run to the illusion. That’s what photography did, which was bad—you run to the image, because the image is so exquisite.

Learoyd: It’s perfect. It’s a perfect thing.

Celmins: But the experience is total. You actually made your photographs more interesting by making them so bit by bit by bit. But still, it’s not painting.

Learoyd: What photographers have to do is, they have to try to find excitement in the exterior world to make the object resonant enough to hold that illusion.

Celmins: Yeah, but you made some boring things, too, like the trees, which I love.

Learoyd: They’re very boring.

Celmins: I like the really boring thing. Yeah, that’s one thing that the photographer can do, which is very difficult to do in the painting, because somehow it kills the way that you’ve constructed the paint to act. And making the paint act in different ways is a big part of painting.

My tools are like hours, and it becomes a real part of the work. Whereas in photography, it’s instantaneous, and then you pick which image.

Learoyd: I was never interested in that side of photography, because my life isn’t very exciting. I just go home. I go to the studio.

Celmins: Well, we’re not talking about your life, we’re talking about the object you’re making.

Learoyd: The object. Exactly. But I think a lot of photographic people, they have to sort of go into the world and seek this subject.

Celmins: Yes, they get very interested in the subject matter. Your method involves that slow way of building the image and making it so precise that it hurts you to look at the thing. It’s really very shocking, in a way.

Learoyd: Yeah. But I think that my problem, going back to the idea of the surface, is that I use a paper that is incredibly shiny, because it means it has no surface. I hate photographic surfaces.

Celmins: I think people now look at all art as if it’s a photograph, which is really upsetting. And they also paint it as if it’s going to be a photograph, and it’s very graphic and sort of stays on the surface. I just saw a Francesca Woodman show, which is totally different. Really upsetting to look at the photographs, because it looks like the devil is after her.

Learoyd: It’s very raw, isn’t it? A very raw sort of expressionism.

Celmins: Right. You have a very different quality. With your work, your eyes think, Oh, my God, I can’t look at any more. It’s so incredibly precise. But hers is emotionally upsetting in a way. Like, I’m running through my short life with this instrument in my hand. See the corners of rooms and places to hide.

Learoyd: Pretty horrible. But so powerful. I didn’t get to see your show last year at Matthew Marks Gallery, but there were some quite big paintings, right?

Celmins: Yeah, I started letting, maybe, some of the paint be a little bit more. Sometimes, I sort of hide the painting, but I let it have a little bit more of an expression. You realize—finally, in my old age —that the paint has its own life, that it can be thin and fat, and it makes it very dimensional. And then sometimes, some of the work that was really small was very drawing related, but drawing with the paint.

Vija Celmins, T.V., 1964. Oil on canvas

Vija Celmins, T.V., 1964. Oil on canvas  Vija Celmins, Envelope, 1964. Oil on canvas

Vija Celmins, Envelope, 1964. Oil on canvasAll works © the artist and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Learoyd: If somebody sees something that relates to how they see it with their eyes, they think that’s photographic, right? So they go, “Oh, that’s a sort of photographic reference.” Because it’s an interpretation that they understand.

Celmins: I really resent that too.

Learoyd: Because the nuance of painting is the ability to do that, or not do that, but it’s a choice. Whereas in photography, there’s no choice.

Celmins: But the painting itself has a life that’s connected to the artist. The best photography has some relation to seeing something that relates more to life-experience seeing, and the way it’s made is much more hidden than in a painting, which is really made out of dust with your hands and brushes and stuff. Sometimes, I hide that, and sometimes, I show more of it.

Learoyd: I think it’s interesting that in photography now, there are more people interested in photography than ever, and yet, there’s so much terrible photography.

Celmins: Every single person is a photographer. And the subject is interesting without the experience of the room. Painting itself is more restrictive. The image is made out of other material, and it has a relation to your body, and how big it is, and how small it is, and how smooth it is, and how rough it is. It’s just got a little bit more experience.

Learoyd: The sort of success or failure as an artwork is whether it contains enigma in some way.

Celmins: Maybe enigma.

Learoyd: I think your relationship to photography is that it’s been of value to you.

Celmins: Well, sometimes there’s the image in my head, and I walk along, and I see a book that’s open in a bookstore, and there’s an image that I may have done myself. I see the grays that I’ve been looking for in the photograph, and I sometimes say, Oh, wow, I’ll follow this and see what I can do with it.

Learoyd: But the things themselves, the objects that you’re making, the paintings, they’re just very much of themselves. They have their own gravity.

Celmins: They don’t really mean the things that people think they mean.

Learoyd: One last topic that we can go into, which is about the sort of generation of a personality in artwork. The problem with photography is that everyone has the same tools. I decided I didn’t want to play with the tools that everybody else had. So, I made cameras, and I used materials in a different way. And you rejected abstract painting, asking instead, Well, what am I surrounded by?

Celmins: Abstraction actually is more complicated than that. But I don’t know what to think about the photograph. The photograph has its own life that I don’t know that much about. We have them everywhere. And for you to make such an unusual-looking experience is pretty extraordinary.

Learoyd: And you leave so much space for the person looking at your paintings and drawings. So much room for interpretation.

Celmins: But you’ve got to realize that it’s material. You see, it’s not an illusion, the painting.

Learoyd: It’s a thing.

Celmins: It’s real. There’s dust on it. It’s the pencil being pushed. It’s the material.

Learoyd: It’s not telling. It’s an invitation, isn’t it?

Celmins: Well, it’s an invitation to figure out . . . I don’t know what it is. But we’re all doing it, aren’t we? I mean, the question is how to be able to experience somebody else’s work in more than just a snap, and to be able to see aspects of it that are really unsayable and have to be in the area of experience.

Learoyd: They have to be experienced.

Celmins: They cannot be said. If you use an image, you realize that the image is an interpretation of something that is not in front of you, that is made by somebody, and how it’s made. It’s like all these instantaneous things that occur.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Learoyd: In a painting, there’re a million decisions.