Aperture's Blog, page 11

February 14, 2025

How Susan Meiselas Documented Nicaragua’s Revolution

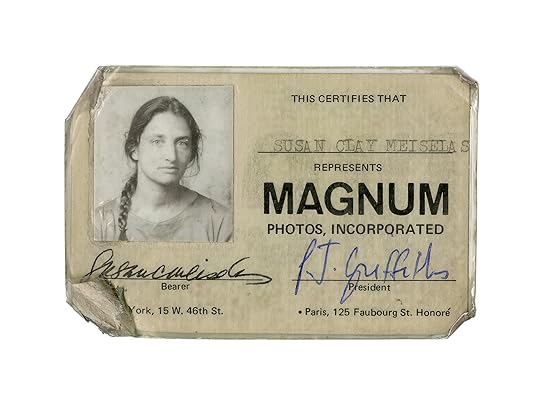

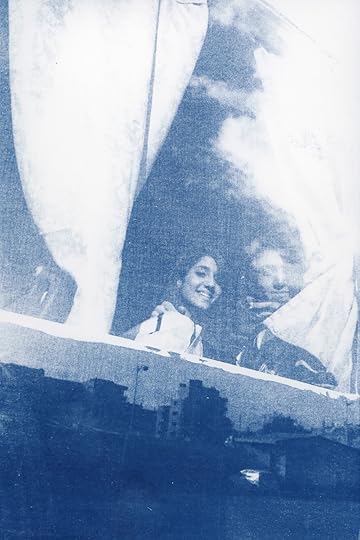

Susan Meiselas first traveled to Nicaragua in June 1978. Three years prior, Meiselas had joined Magnum Photos, and this trip marked her first experience working in conflict photography. Meiselas went on to spend just over a year in Nicaragua, documenting an extraordinary narrative of a nation in turmoil, from the powerful evocation of Somoza regime during its decline in the late 1970s, to the evolution of the popular resistance that led to the triumph of the Sandinista revolution in 1979.

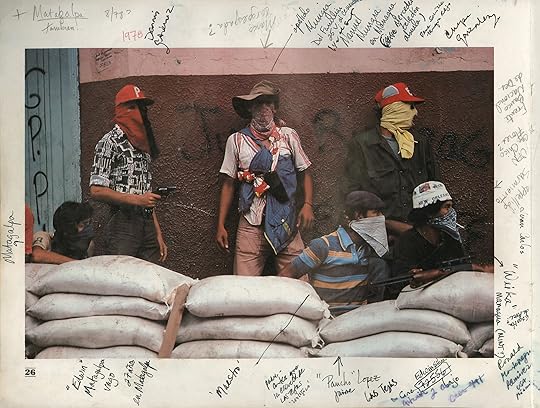

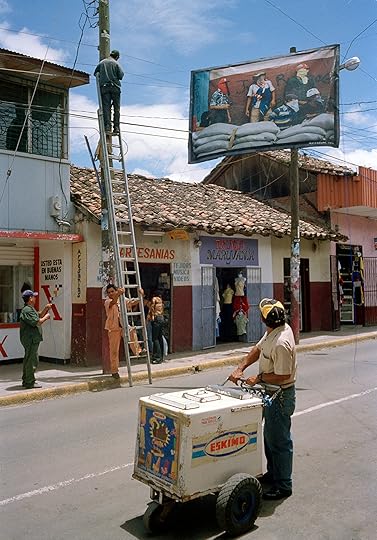

Originally published in 1981, and now in a third edition, Susan Meiselas’s Nicaragua: June 1978–July 1979 is a contemporary classic and formative contribution to the literature of concerned photography. In the decades following the original publication, Meiselas has continued to contextualize her photographs and relate them to history as it unfolded. In this new edition, thirty images are linked via QR codes to excerpts from films by the artist, including Pictures from a Revolution (1991, codirected with Richard P. Rogers and Alfred Guzzetti) in which Meiselas tracks down and interviews the people she photographed, and Reframing History (2004, codirected with Alfred Guzzetti), which highlights her collaborations with local communities installing mural-sized images in the places where they were originally taken, eliciting the memories and reflections of those passing by.

By extending and deepening her work, Meiselas asks us “to consider not only the specific timeframe of this book, but to think about the broader perspective of history unfolding, and how in the passage of time a photograph of a single moment in a person’s life shifts its meanings as well as our perception of it.” In an interview from the book, Meiselas speaks with Magnum Foundation’s director, Kristen Lubben, on how the work of this evolving project has been circulated, revisited, and repatriated—and how and why it endures.

Susan Meiselas, Awaiting counter attack by the Guard in Matagalpa, 1978–79

Susan Meiselas, Awaiting counter attack by the Guard in Matagalpa, 1978–79  Susan Meiselas, Car of a Somoza informer burning in Managua, 1978–79

Susan Meiselas, Car of a Somoza informer burning in Managua, 1978–79 Kristen Lubben: Before going to Nicaragua in 1978 you had never photographed conflict nor had you worked for the media. You were coming from what seems like a totally different universe than that of a war photographer: You were working on Prince Street Girls, portraits of adolescent girls in your Little Italy neighborhood, and two years earlier you had published Carnival Strippers, an extended photo-essay on women in traveling strip shows in New England, now a photo classic.

Susan Meiselas: Yes, Nicaragua was a quantum leap for me. Not only was the subject matter of Carnival Strippers and Prince Street Girls different than what I would encounter in Nicaragua, but I was also used to working in a different way—having extended relationships with subjects, and bringing back contact sheets for them to respond to. Carnival Strippers was the work I submitted to join Magnum, the photographer’s collective.

Magnum Photos press ID, 1978

Lubben: And did joining Magnum lead you to go to Nicaragua?

Meiselas: At Magnum there was a culture that supported taking initiative—going to a place not knowing more than whatever you could scrape together from afar. Remember, we are in a transformed world of information now; you can sit at home and do research online and feel you know a place without ever going there. But I had no idea what Nicaragua even looked like. I was reading snippets, these little stories that were ten lines long, and I wasn’t seeing any photographs with them. That made me think, “Maybe I should go—but how do you do that?”

The tipping point was a full-page New York Times article in January of 1978 about the assassination of Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal, the editor of the newspaper La Prensa and the country’s most outspoken opposition figure. Maybe it was the size of that article; maybe it was the way in which it implicated America in supporting the Somoza family. It all just started to turn in my head.

Through Gilles Peress at Magnum I met Peter Pringle, a British journalist working for the London Times. He had just been to Nicaragua, writing about the history of the English on the Atlantic coast, but hadn’t touched on what was happening with the brewing revolution, and was curious to do that. So I said, “Great.” I just assumed that’s what you do: find a writer you want to work with, and you go and do it. Then between February and when I ultimately left in June, there were more stories about Nicaragua—strikes and student protests, small events that kept percolating through the news. Peter, meanwhile, got bogged down and kept delaying the trip. One day I was at Magnum and [photographer] Richard Kalvar said, “I thought you were going to Nicaragua.” And I said, “Well, Peter can’t go . . . ” He said, “What do you need him for? You’re going to take the pictures.” It was kind of like, “Wow. Okay. That’s another idea.” That nudge helped me make the leap.

And I went. With no concrete plan in place. I didn’t speak Spanish. I didn’t even know where I would stay. It sounds nuts, but it’s true.

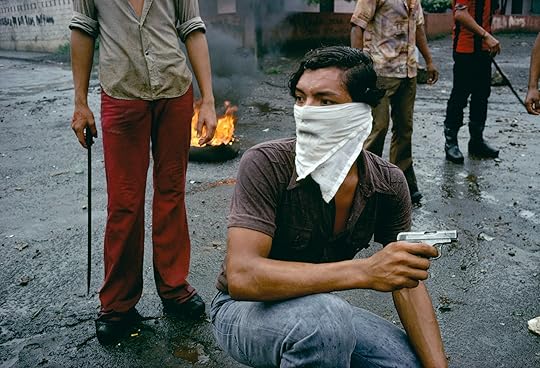

Susan Meiselas, Street fighter in Managua, 1978–79

Susan Meiselas, Street fighter in Managua, 1978–79  Susan Meiselas, Student demonstration broken up by the National Guard using tear gas, Managua, 1978–79

Susan Meiselas, Student demonstration broken up by the National Guard using tear gas, Managua, 1978–79 Lubben: So how did you get started? Did you just walk around Managua, taking pictures?

Meiselas: Yes, walking around, really feeling like I didn’t know what I was doing. But the first day, I went to La Prensa and I met with Carlos Fernando Chamorro, the son of the man who had been killed, and Margarita Montealegre, who was a young photographer at the newspaper. I was lucky that they both spoke English.

Lubben: Were there any other foreign photographers there?

Meiselas: There was one other, a Colombian photographer who came for a protest march, around the time Los Doce (The Twelve) returned to Nicaragua. Los Doce was an alliance of middle-class businessmen, lawyers, and professionals who aligned themselves with the Sandinistas against Somoza. They were kind of a legal front. The Sandinistas were underground. During that first trip I met many people who were sympathetic to the Sandinistas, but I didn’t meet anybody inside the organization. Or, if I did, I didn’t know that they were.

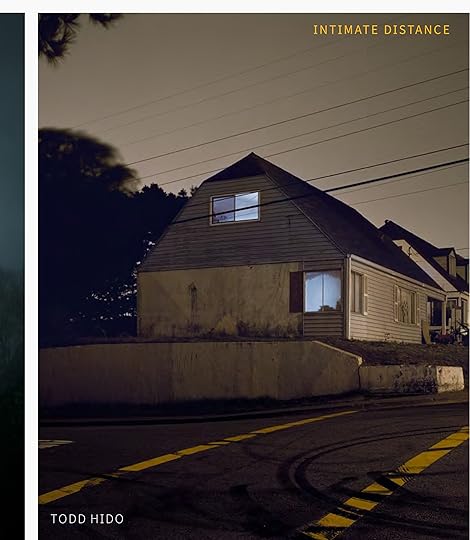

Susan Meiselas: Nicaragua 50.00 Originally published in 1981, and now in a third edition, Susan Meiselas’s Nicaragua is a contemporary classic—a seminal contribution to the literature of concerned photography.

Susan Meiselas: Nicaragua 50.00 Originally published in 1981, and now in a third edition, Susan Meiselas’s Nicaragua is a contemporary classic—a seminal contribution to the literature of concerned photography. $50.0011Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

Susan Meiselas: NicaraguaPhotographs by Susan Meiselas. Text by Kristen Lubben.

$ 50.00 –1+$50.0011Add to cart

View cart Description

Originally published in 1981, and now in a third edition, Susan Meiselas’s Nicaragua is a contemporary classic—a seminal contribution to the literature of concerned photography.

Nicaragua: June 1978–July 1979 forms an extraordinary narrative of a nation in turmoil. Starting with a powerful and chilling evocation of the Somoza regime during its decline in the late 1970s, the images trace the evolution of the popular resistance that led to the triumph of the Sandinista revolution in 1979. The book includes interviews with various participants in the revolution, along with letters, poems, and statistics.

In the decades following the original publication, Meiselas has continued to contextualize her photographs and relate them to history as it unfolded. Multiple editions build upon this body of work to evoke and conjure up the reality of people’s lives and aspirations, their victories and disappointments. In this new edition, thirty images are linked via QR codes to excerpts from the films Pictures from a Revolution (1991, codirected with Richard P. Rogers and Alfred Guzzetti) in which Meiselas tracks down and interviews the people she photographed, and Reframing History (2004, codirected with Alfred Guzzetti), her collaboration with local communities in installing mural-sized images in the places where they were originally taken, eliciting the memories and reflections of those passing by. By extending and deepening her work, Meiselas asks us “to consider not only the specific timeframe of this book, but to think about the broader perspective of history unfolding, and how in the passage of time a photograph of a single moment in a person’s life shifts its meanings as well as our perception of it.” An interview with the artist by Magnum Foundation’s director, Kristen Lubben, addresses how the work of this evolving project has been circulated, revisited, and repatriated—and how and why it endures.

DetailsFormat: Hardback

Number of pages: 128

Number of images: 75

Publication date: 2025-03-11

Measurements: 10.8 x 8.5 inches

ISBN: 9781597115902

Susan Meiselas (born in Baltimore, 1948) is a documentary photographer based in New York. She received her BA from Sarah Lawrence College and her MA in visual education from Harvard University. Her first book, Carnival Strippers, was published in 1976. That year, Meiselas joined Magnum Photos, where she remains a member, and since 2007 has served as president of the Magnum Foundation. Her numerous awards include a Guggenheim Fellowship, Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize, and the first Women in Motion Award from Kering and Rencontres d’Arles.

Kristen Lubben is a curator, writer, editor, and executive director of the Magnum Foundation.

Featured 15 Essential Photobooks by Women Photographers

Featured 15 Essential Photobooks by Women Photographers  Photobooks When Women Photographers Went to War

Photobooks When Women Photographers Went to War Lubben: Did you have any frame of reference in your own history for what you were experiencing in those early days in Nicaragua?

Meiselas: The students went on strike at the university in Managua when I was there. I might have chosen that image in the book because of the association I made with marching on Washington against the Vietnam War in ’68 during my own student years. I’m also of that generation where some people joined SDS (Students for a Democratic Society) and the Weather Underground, though that was not what I did. But the language of opposition was very strong at that time, along with the feeling that change was possible in America.

I think that’s probably why I was so intrigued by the question of how the Nicaraguans were going to overthrow a dictatorship that had been in place for fifty years. There were various sectors throwing their weight together, building momentum. The businessmen who owned the factories were supporting the workers who were on strike. Of course, no one believed they were really going to unify to the point that they would overthrow Somoza. The confrontation wasn’t constant, it wasn’t every day. It wasn’t until the insurrection in August 1978 that I was really in the middle of a war, and that was something totally unfamiliar to me.

Lubben: Is that when you shifted to shooting primarily in color rather than black and white?

Meiselas: When I first went to Nicaragua, I was working with two cameras, one loaded with black-and-white film and one with color. I started out thinking that I’d use mostly black and white, and it progressively became almost all color. It didn’t happen in the first six weeks; I think it just slowly evolved. I didn’t really switch; I think I just put more weight on one foot at a certain point. As time went on, the black and white became more like a sketchbook, so I knew what I had when I processed the film in Nicaragua. It was my reference set. I shot that way later in El Salvador, too. But in El Salvador I made the opposite decision. Although there is color from El Salvador that I like quite a lot, at that time I really decided the work was stronger in black and white.

Susan Meiselas, Youths practice throwing contact bombs in forest surrounding Monimbo, 1978–79

Susan Meiselas, Youths practice throwing contact bombs in forest surrounding Monimbo, 1978–79  Susan Meiselas, Traditional Indian dance mask from the town of Monimbo, adopted by the rebels during the fight against Somoza to conceal identity, 1978–79

Susan Meiselas, Traditional Indian dance mask from the town of Monimbo, adopted by the rebels during the fight against Somoza to conceal identity, 1978–79 Lubben: You felt Nicaragua was better served by color film.

Meiselas: Yes. Well, not “better served,” because that sounds like I’m in service of it. It’s that it captured what it felt like—the way people dressed, the way they painted their houses.

Lubben: But why wasn’t that true in El Salvador?

Meiselas: El Salvador was darker because of the brutality of the military dictatorship throughout the civil war. People dressed that same way, but I didn’t feel the same spirit of—maybe optimism—in El Salvador. It was really a crushing place to be. Black and white definitely captured that mood better.

Lubben: Your use of color film turned out to be controversial: In 1981 when you published the images in Nicaragua, critics challenged your choice.

Meiselas: Photographs in newspapers were still in black and white, and color images of war were not yet familiar to people. Of course, now no one even thinks about this. At the time, I wasn’t taking a position in the debate about whether war should or shouldn’t be shown only in black and white. And I wasn’t responding to editorial pressures to work in color, as has also been suggested. I worked in color because I was responding to what I was seeing, and maybe feeling.

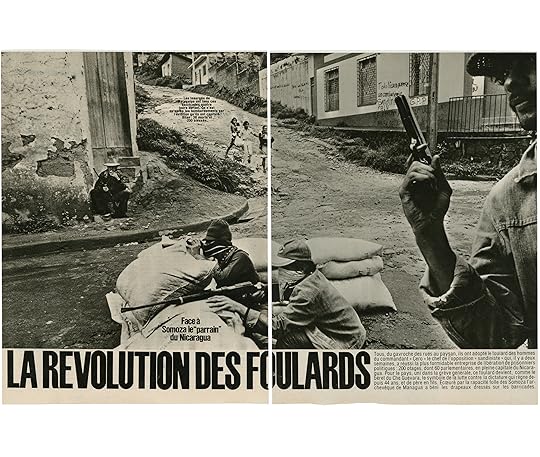

Paris Match, September 15, 1978

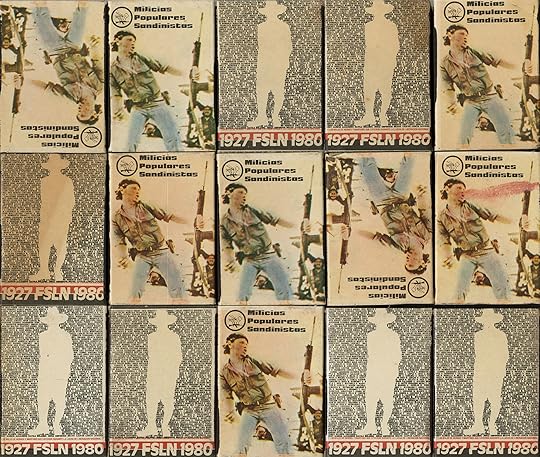

Paris Match, September 15, 1978  Matchboxes commemorating the first anniversary of the revolution, July 19, 1980

Matchboxes commemorating the first anniversary of the revolution, July 19, 1980 Lubben: Why did you decide to do the book? Were you responding to the way your images were used in the press?

Meiselas: With Strippers, the women and I were sharing a process. I was hearing them reflect on what their concerns were and how they saw the photographs of themselves. With the media distribution of my work in Nicaragua I had absolutely no connection at all to the process of selection, diffusion, and impact on peoples’ lives, or how they felt about it. When you ask the question, why did I do a book? I wanted to contextualize the work. It didn’t matter how many pictures had been reproduced in multiple magazines around the world. I wanted to bring them together in some way that would give coherence to my experience. At the same time, I was thoroughly aware that it was incomplete.

I continue to discover how pictures circulate, including in Nicaragua itself, where the images have often been reappropriated. One image in particular, known as “Molotov Man” [plate 64], appeared on matchbox covers, and then painted on walls. “Bareta,” the man in the picture, became a symbol for the revolution. Some images have separate lives. This one has now entered a complex debate about copyright and free use as well as who has the right to an image, including the subjects themselves.

Lubben: Two of your films about Nicaragua, Pictures from a Revolution (1991) and Reframing History (2004), both speak to your longstanding interest in returning to the scene and in repatriating your work. In Pictures, you went back to Nicaragua ten years after the revolution to track down the subjects in your photographs. What initially compelled you to do the film?

Meiselas: I became preoccupied with what had happened to the people in my photographs and wondered where they were and what they thought about the political shift in Nicaragua. It was something I thought about often, especially traveling between El Salvador and Nicaragua during those years of continuous civil war. Alfred Guzzetti and Dick Rogers and I had done an earlier film together in 1986, Living at Risk, about an upper-middle-class Nicaraguan family, but the stories behind my pictures of the insurrection had a more emotional center for me. Alfred had the idea for a more ambitious film of historical scope, consisting entirely of interviews, without a narrator. His model was Marcel Ophuls’s great documentary, The Sorrow and the Pity, about the French Resistance during the Nazi occupation. I honestly didn’t feel I had the depth of knowledge to do that idea justice. My proposal was more modest.

Notes gathered from Nicaraguans while searching for subjects of the original photos during the making of Pictures from a Revolution in 1989

Notes gathered from Nicaraguans while searching for subjects of the original photos during the making of Pictures from a Revolution in 1989  Susan Meiselas, Monimbo woman carrying her dead husband home to be buried in their backyard, 1978–79

Susan Meiselas, Monimbo woman carrying her dead husband home to be buried in their backyard, 1978–79 Lubben: What was it like to talk to these subjects after all this time?

Meiselas: I especially loved the “search mode,” as we called it then, finding the people, which is best captured in the sequence of smaller and smaller roads that we traveled in order to find Nubia, the woman in the red dress. Her interview with all the kids surrounding her was particularly moving. She and I had shared a moment in time, and she remembered the conditions better than I did; she was carrying her dead husband in a wheelbarrow while bullets were flying all around us. It was a very special moment when she touched the same earrings she was wearing in the photo or pointed to the new shoes she had buried him with. She had a real sense of pride, having buried him all by herself—and at age fourteen!

Lubben: In your view, how was the film received?

Meiselas: I suppose we were initially surprised by the response, especially that many people wanted to see the photographs, not hear from the people in them. I am still fascinated by that schism between the aesthetic object—the “frame”—versus the lives that come forth from behind the photograph. Is it that we at times want the distance that a formal composition can give us or that we just don’t want to know or feel too much involvement? A frozen life in a photograph is perplexing for me . . . I suppose it’s part of the “going back” that I am often inclined to do. As much as I like the formalism, I am propelled to reconnect. I seek the feeling that comes from the connection. I think that moment of engagement is ultimately what sustains me as a photographer.

Of course time allows us to reflect. In the case of our film, perhaps we were too close to the time of those events; no one wanted to think about the failure of the revolution, and the Left wanted to simply blame the electoral defeat of the Sandinistas on the aggression of the US. The complexity of those years still needs to be reconsidered.

Susan Meiselas, Toward Sandinista training camp in the mountains north of Estelí, 1978–79

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }Lubben: You also made a film with Marc Karlin in 1985 called Voyages, for Channel 4 in England, in which you reflect on your role in Nicaragua through a series of letters to the filmmaker. At the end of that film you say: “I have pictures; they have a revolution.” In that poetic statement you seem to be finally moving on from Nicaragua, saying, in effect: “This is done for me; I’m no longer inside it. I’m now outside it.”

Meiselas: It’s a really strong line for me still. I think it was a painful acknowledgment of the limits of my work. Ultimately, I was as inside as an outsider can be, but you’re always an outsider. They had a society to build. They were going to start from the sidewalks on up; they wanted to transform everything. And I wasn’t going to be part of that.

If El Salvador hadn’t erupted, maybe I would have stayed longer. But my guess is that I would have started to feel I had a role somewhere else. It’s not to say I didn’t want to go back; I wanted to sustain relationships there but not stay. What I chose to do within the first year following the triumph was work with local photographers as they built the first newspaper. So I contributed in the ways that felt within the bounds of what I particularly could do.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

From Reframing History,a mural in the landscape where the picture was originally taken, Matagalpa, 2004

From Reframing History,a mural in the landscape where the picture was originally taken, Matagalpa, 2004Lubben: And of course you went back with your project Reframing History and transformed nineteen of your pictures into murals and hung them in public places, on the sites where they were originally taken twenty-five years before.

Meiselas: Yes. Reframing History came from a different process. I was digitizing part of my archive, and I was looking at all that work thinking, “Why bother to digitize it? What value do these pictures have, and for whom?” I thought, “Would they be of any value to the archives in Nicaragua? Is it of interest even to the people who were in the pictures twenty-five years ago, or the people who weren’t there but had heard about it?” That’s what led me to the idea of bringing mural-sized images back.

I found out about the Institute of History and started a dialogue with them. I also asked Carlos Fernando, my old friend, and Gioconda Belli, a Nicaraguan poet, if they thought my idea would seem appropriate to people there.

Ultimately, I collaborated with the Institute of History, who contacted the mayors of the four towns, and I chose nineteen pictures—symbolic of July 19, the day of the triumph over Somoza in 1979. Even up to the day that we arrived with the murals, it wasn’t clear if we were going to be able to put the murals on what had been the National Palace. Everything got negotiated—in each town, with each mayor, with each wall. You know the famous photograph on the cover? The man who lives in that house didn’t want the photograph on the wall of his house, so we hung the banner over the street. He was fine about that. He just didn’t want to have anybody mistakenly think that he was a Sandinista. There were other people who identified with the photographs. Ernesto’s mother was deeply honored, having the photograph of her son running across the street illuminated at night by a street lamp. There were many different kinds of reactions to seeing the murals, which we recorded on video; listening to the comments and watching people look at the images back in the landscape.

At that same time, there was also a film festival. It was really amazing for people because they had not seen any films from the 1970s into the ’80s. There were all these college kids who had heard about the revolution from their parents, and suddenly they saw images of Nicaraguans in the streets and realized they really missed out. It was like the people who felt they missed ’68 in our country.

Susan Meiselas, First day of popular insurrection, August 26, 1978

Susan Meiselas, First day of popular insurrection, August 26, 1978  Susan Meiselas, Searching everyone traveling by car, truck, bus, or foot, 1978–79

Susan Meiselas, Searching everyone traveling by car, truck, bus, or foot, 1978–79Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Lubben: In the 2008 edition of the book you included a DVD with the films Pictures from a Revolution and Reframing History; in this 2016 edition, in place of the DVD—now well on its way to becoming a defunct technology—you have introduced an augmented reality (AR) customized app, which takes the reader to short clips of the films that relate to specific images in the book. (Editor’s note: In this 2025 edition, the AR has been replaced with QR codes, the video clips are expanded, and the number of linked images has increased.)

Meiselas: The change in how we are including the films is both pragmatic and conceptual. I am curious to see if linking film clips closer to selected images will create the possibility for greater engagement. The idea of bringing together the original images with snippets from the films was one I first explored in exhibition installations, when I paired photographs with their corresponding section of the films in which people reflected ten years after the image was made.

Lubben: You also have chosen to use AR technology to link to a portfolio of previously unpublished images of life in Nicaragua in the years following the revolution.

Meiselas: Yes, the selection of those images was inspired by what Padre Ernesto Cardenal, the renowned poet and priest, wrote about during and after the popular insurrection, including the excitement and challenges of transforming Nicaraguan culture in the wake of the triumph. The photographs show small everyday moments, alongside the dramatic events of that year, and their hopes for a normalized life. The revolution was the beginning of a process—of reconstruction and remembrance—not the end. A series of these images appears as a little movie that can be accessed at the end of the Chronology section.

Lubben: How do you imagine that accessing a film clip by holding a smartphone over a still image in the book will change the experience of the films?

Meiselas: With the Nicaragua project, I have always been really interested in the way that history evolves, and the AR process enables a different way to look at that extending timeline and relate it back to the images. The risk with AR is that unlike with a linear movie, where you can capture your viewer and hold them through a narrative, you can’t do that with this more fractured approach. Through twenty short excerpts, we will be including about one-third of the film Pictures from a Revolution. How is that a fundamentally different experience? Will readers then be propelled to download or stream the full ninety-minute film? I don’t know.

I’m asking the reader to consider not only the specific timeframe of this book (1978–79), but to think about the broader concept of history unfolding, and how a photograph from a single moment in a person’s life shifts and our perception expands over the passage of time.

This interview originally appeared in Susan Meiselas: Nicaragua (Aperture, 2025).

12 Photobooks That Celebrate Black Voices and History

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Grandma Ruby and Me, 2005

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Grandma Ruby and Me, 2005Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery

Race Stories: Essays on the Power of Images, by Maurice Berger (2024)

In Race Stories: Essays on the Power of Images, the late cultural historian Maurice Berger explores the intersections of photography, race, and visual culture. Between 2012 and 2019, Berger first shared these essays in a monthly column on the New York Times Lens blog. Copublished by Aperture and the New York Times, this volume marks the first title in Aperture’s Vision & Justice Book Series, created and coedited by Drs. Sarah E. Lewis, Leigh Raiford, and Deborah Willis, which reexamines and redresses historical narratives of photography, race, and justice.

Edited by Marvin Heiferman, this anthology brings together seventy-one essays that examine the transformational role photography plays in shaping ideas and attitudes about race, and how photographic images have been instrumental in both perpetuating and combating racial stereotypes. From pivotal moments in American history to the ways in which images by LaToya Ruby Frazier, Gordon Parks, Jamel Shabazz, Pete Souza help us see the world anew, Race Stories showcases Berger’s lifelong endeavor to distill complex ideas about racial equity. As Henry Louis Gates, Jr., writes in the book’s foreword: “This collection establishes not only Maurice Berger’s place in the history of the criticism of photography but also his role as a social philosopher determined to underscore, essay by essay, all that unites us as human beings.”

Dawoud Bey, Irrigation Ditch, 2019

Dawoud Bey, Irrigation Ditch, 2019Courtesy the artist

Dawoud Bey: Elegy (2023)

In Elegy, Dawoud Bey focuses on the landscape to create a portrait of the early African American presence in the United States. Renowned for his Harlem street scenes and expressive portraits, this volume marks a continuation of Bey’s ongoing work exploring African American history. Copublished by Aperture and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Elegy focuses on three of Bey’s landscape series—Night Coming Tenderly, Black (2017); In This Here Place (2021); and Stony the Road (2023)—shedding a light on the deep historical memory still embedded in the geography of the US.

Bey takes viewers to the historic Richmond Slave Trail in Virginia, where Africans were marched onto auction blocks; to the plantations of Louisiana, where they labored; and along the last stages of the Underground Railroad in Ohio, where fugitives sought self-emancipation. By interweaving these bodies of work into an elegy in three movements, Bey not only evokes history but retells it through historically grounded images that challenge viewers to go beyond seeing and imagine lived experiences. “This is ancestor work,” Bey tells the New York Times. “Stepping outside the art context, the project context, this is the work of keeping our ancestors present in the contemporary conversation.”

Arielle Bobb-Willis, Austin, 2020

Arielle Bobb-Willis, Austin, 2020Courtesy the artist

Arielle Bobb-Willis: Keep the Kid Alive (2024)

Born in 1994 in New York, Arielle Bobb-Willis first started to experiment with photography at the age of fourteen, when she was gifted an old Nikon N80 film camera by her high school history teacher after her family relocated to South Carolina. Since then, Bobb-Willis has become a rising photographer, having shot commissions for a range of magazines and fashion brands including Vogue, the New York Times, Vanity Fair, Nike, Hermès, and more. In 2024, Aperture published the artist’s first monograph, Keep the Kid Alive. Previously, Aperture had featured Bobb-Willis’s work in the The New Black Vanguard (2017), which highlights the work of fifteen contemporary Black photographers rethinking the possibilities of representation.

In Keep the Kid Alive, Bobb-Willis invites audiences into a brightly imaginative world, filled with dynamic colors, gestures, and unusual poses of the artist’s own creation. Transforming the streets of New Orleans, New York, and Los Angeles into lush backdrops for her wonderfully surreal tableaux, Bobb-Willis makes unforgettable images that expand the genres of fashion and art photography. As Bobb-Willis notes in an interview from the book, “Photography is, and will always be, a daily practice of falling in love with as many things as I can.”

Collect a limited-edition print by Arielle-Bobb Willis from Keep the Kid Alive.

Kwame Brathwaite, Model wearing a natural hairstyle, AJASS, Harlem, ca. 1970

Kwame Brathwaite, Model wearing a natural hairstyle, AJASS, Harlem, ca. 1970Courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

Kwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful (2019)

Kwame Brathwaite’s photographs from the 1950s and ’60s transformed how we define Blackness. Using his photography to popularize the slogan “Black Is Beautiful,” Brathwaite challenged mainstream beauty standards of the time that excluded women of color.

Brathwaite, who passed away in 2023, was born in Brooklyn and part of the second-wave Harlem Renaissance. Brathwaite and his brother Elombe Brath founded the African Jazz-Art Society & Studios (AJASS) and the Grandassa Models. AJASS was a collective of artists, playwrights, designers, and dancers; Grandassa Models was a modeling troupe for Black women. Working with these two organizations, Brathwaite organized fashion shows featuring clothing designed by the models themselves, created stunning portraits of jazz luminaries, and captured behind-the-scenes photographs of the Black arts community, including Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln, and Miles Davis.

Black Is Beautiful is the first-ever monograph of his work, showcasing Brathwaite’s riveting message about Black culture and freedom. “To ‘Think Black’ meant not only being politically conscious and concerned with issues facing the Black community,” writes Tanisha C. Ford, “but also reflecting that awareness of self through dress and self-presentation. . . . [They] were the woke set of their generation.”

Ernest Cole, Untitled, New York City, 1968–71

Ernest Cole, Untitled, New York City, 1968–71© The Ernest Cole Family Trust

Ernest Cole: The True America (2024)

After fleeing South Africa to publish his landmark book House of Bondage in 1967 (reissued by Aperture in 2022) on the horrors of apartheid, Ernest Cole became a “banned person” and resettled in New York. Supported by a grant from the Ford Foundation, Cole photographed the city’s streets extensively, chronicling daily life in Harlem and around Manhattan. In 1968 he traveled across the country to cities including Chicago, Cleveland, Memphis, Atlanta, Los Angeles, and Washington, DC, as well as to rural areas of the South, capturing the activism and emotional tenor in the months leading up to and just after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. These photographs reflect both the newfound freedom Cole experienced in the US and the photographer’s sharp eye for inequality as he became increasingly disillusioned by the systemic racism he witnessed.

Cole released very few images from this body of work while he was alive. Thought to be lost entirely, the negatives of Cole’s American pictures resurfaced in Sweden in 2017 and were returned to the Ernest Cole Family Trust. The True America marks the first time these photographs have been brought together in a major publication. This trove of rediscovered work acts as a vital window into American society and redefines the scope of Cole’s photographic work.

Collect a limited-edition print from Ernest Cole: The True America. An exhibition of The True America is on view at the Minneapolis Institute of Art through June 22, 2025.

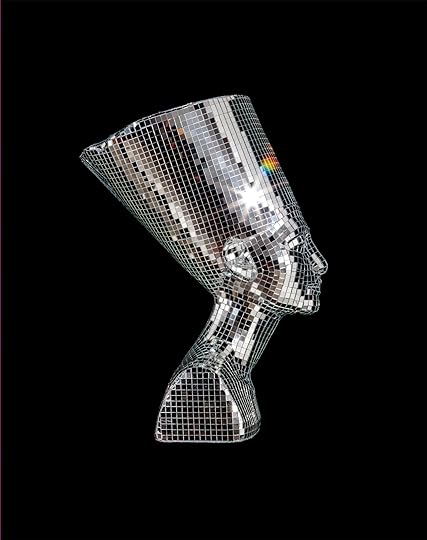

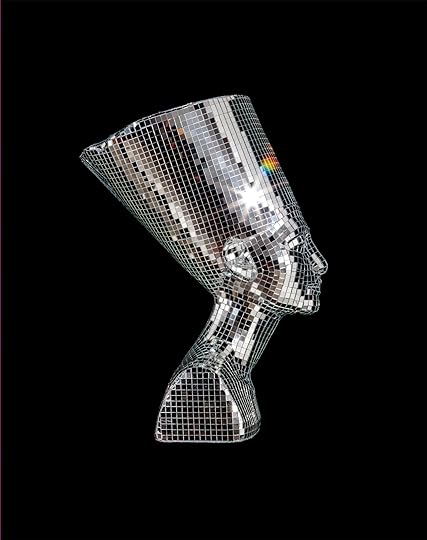

Awol Erizku, Love Is Bond (Young Queens), 2018–20

Awol Erizku, Love Is Bond (Young Queens), 2018–20Courtesy the artist

Awol Erizku: Mystic Parallax (2023)

Awol Erizku’s interdisciplinary practice references and reimagines African American and African visual culture, from hip-hop vernacular to Nefertiti, while nodding to traditions of spirituality and Surrealism. The 2023 volume Mystic Parallax is the first major monograph to trace the artist’s career. Spanning over ten years, the monograph blends together his studio practice with his work as an in-demand editorial photographer, including his conceptual portraits of cultural icons such as Solange, Amanda Gorman, and Michael B. Jordan.

Throughout his work, Erizku consistently questions and reimagines Western art, often by casting Black people in his contemporary reconstructions of canonical artworks. “I always think about my work as a constellation, and a new piece is just another star within the universe,” he asserts in his wide-ranging conversation with the curator Antwaun Sargent, included in the book. “This goes back to the idea of a continuum of the Black imagination. When it’s my turn, as an image maker, a visual griot, it is up to me to redefine a concept, give it a new tone, a new look, a new visual form.”

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

James Barnor, Drum Cover Girl Erlin Ibreck, Kilburn, London, 1966

James Barnor, Drum Cover Girl Erlin Ibreck, Kilburn, London, 1966Courtesy the artist

As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic (2021)

In 1997, Dr. Kenneth Montague founded the Wedge Collection in Toronto in an effort to acquire and exhibit work by artists of African descent. As We Rise features over one hundred works from the collection, bringing together artists from Canada, the Caribbean, Great Britain, the US, South America, and Africa in a timely exploration of Black identity on both sides of the Atlantic.

From Jamel Shabazz’s definitive street portraits to Lebohang Kganye’s blurring of self, mother, and family history in South Africa, As We Rise looks at multifaceted ideas of Black life through the lenses of community, identity, and power. As Teju Cole describes in his preface, “Too often in the larger culture, we see images of Black people in attitudes of despair, pain, or brutal isolation. As We Rise gently refuses that. It is not that people are always in an attitude of celebration—no, that would be a reverse but corresponding falsehood—but rather that they are present as human beings, credible, fully engaged in their world.”

Collect a special vinyl LP, As We Rise: Sounds from the Black Atlantic , featuring a celebratory collection of classic and contemporary Black music made throughout the diaspora.

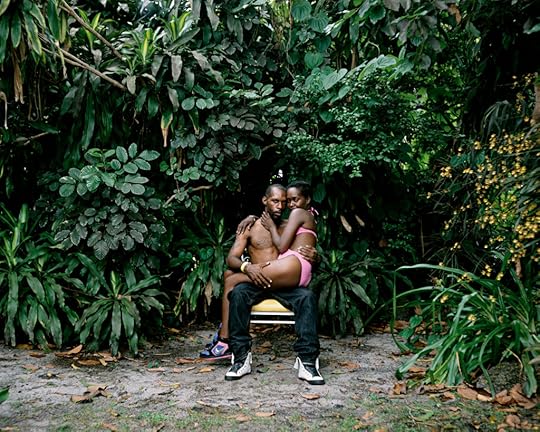

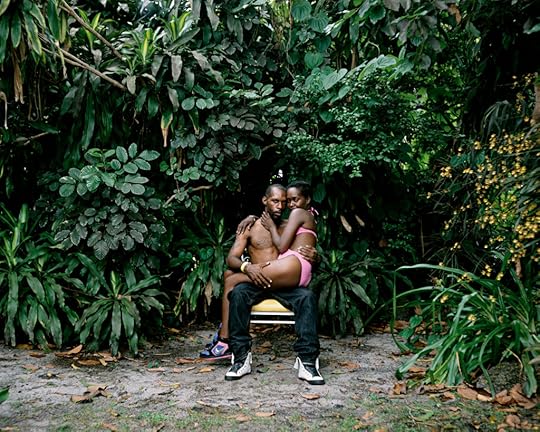

Deana Lawson, Oath, 2013

Deana Lawson, Oath, 2013Courtesy the artist

Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph (2018)

Deana Lawson has created a visionary language to describe identities through intimate portraiture and striking accounts of ceremonies and rituals. Using medium- and large-format cameras, Lawson works with models throughout the US, Caribbean, and Africa to construct arresting, highly structured, and deliberately theatrical scenes. Signature to Lawson’s work is an exquisite range of color and attention to detail—from the bedding and furniture in her domestic interiors to the lush plants and Edenic gardens that serve as dramatic backdrops.

Published in 2018, Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph was the first book by the acclaimed artist. In 2020, Lawson became the first photographer to be awarded the Hugo Boss Prize. Most recently, Lawson was the guest editor of Aperture’s Fall 2024 issue, “Arrhythmic Mythic Ra,” in which she curated a selection of artists past and present to explore the enigmatic nature of photography.

One of the most compelling photographers of her generation, Lawson portrays the personal and the powerful. “Outside a Lawson portrait you might be working three jobs, just keeping your head above water, struggling,” writes Zadie Smith in an essay for the book. “But inside her frame you are beautiful, imperious, unbroken, unfallen.”

Collect a limited edition of Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph, featuring a special slipcase and custom tipped-on C-print.

Zanele Muholi, Mihla IV, Port Edward, South Africa, 2020

Zanele Muholi, Mihla IV, Port Edward, South Africa, 2020Courtesy the artist

Zanele Muholi: Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness, Volume II (2024)

The South African artist Zanele Muholi is one of the most powerful visual activists of our time. Muholi first gained recognition for their 2006 series Faces and Phases that documents the LGBTQIA+ community, creating ambitiously bold portraits in an attempt to build a visual history and remedy Black queer erasure. From there, Muholi began to turn the camera inward, beginning a series of evocative self-portraits. Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness, Volume II (2024) is the follow-up to Muholi’s critically acclaimed first title featuring their self-portraits.

In their evocative self-portraits, Muholi explores and expands upon notions of Blackness, and the myriad possibilities of the self. Drawing on different materials or found objects referencing their environment, a specific event, or lived experience, Muholi boldly explores their own image and innate possibilities as a Black person in today’s global society, and speaks emphatically in response to contemporary and historical racisms. “I am producing this photographic document to encourage individuals in my community to be brave enough to occupy spaces—brave enough to create without fear of being vilified,” Muholi states in an interview from the 2018 volume. “To teach people about our history, to rethink what history is all about, to reclaim it for ourselves—to encourage people to use artistic tools such as cameras as weapons to fight back.”

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Drop Scene (_1030683), 2018

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Drop Scene (_1030683), 2018Courtesy the artist

Paul Mpagi Sepuya: Dark Room A–Z (2024)

Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s photography is grounded in a collaborative, rhizomatic approach to his studio practice and portraiture. Through collage, layering, fragmentation, and mirror imagery, Sepuya encourages multivalent narrative readings of each image.

Four years after publishing the first widely available volume of Sepuya’s work, Aperture released Dark Room A–Z, a comprehensive monograph that dives into the thick network of references and the interconnected community of artists and subjects that he has interwoven throughout the images. The volume unpacks Sepuya’s Dark Room series (2016–21), reflecting on the methodologies, strategies, and points of interest behind this expansive body of work. Alongside Sepuya’s work is a range of writings by critics, curators, friends, and the artist. Dark Room A–Z serves as an iterative return and exhaustive manual to the strategies and generative ways of working that have informed Sepuya’s image-making, after nearly two decades of practice.

Ming Smith, Sun Ra Space II, New York, 1978

Ming Smith, Sun Ra Space II, New York, 1978© the artist

Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (2020)

Ming Smith’s poetic and experimental images are icons of twentieth-century Black American life. Smith began experimenting with photography as early as kindergarten, when she made pictures of her classmates with her parents’ Brownie camera. She went on to attend Howard University, Washington, DC, where she continued her practice, and eventually moved to New York in the 1970s. Smith supported herself by modeling for agencies like Wilhelmina, and around the same time, joined the Kamoinge Workshop. In 1979, Smith became the first Black woman photographer to have work acquired by the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Throughout her career, Smith has photographed various forms of Black community and creativity—from mothers and children having an ordinary day in Harlem, to her photographic tribute to playwright August Wilson, to the majestic performance style of Sun Ra. Her trademark lyricism, distinctively blurred silhouettes, and dynamic street scenes established Smith as one of the greatest artist-photographers working today. As Yxta Maya Murray writes for the New Yorker, “Smith brings her passion and intellect to a remarkable body of photography that belongs in the canon for its wealth of ideas and its preservation of Black women’s lives during an age, much like today, when nothing could be taken for granted.”

Shikeith, O’ my body, make of me always a man who questions!, 2020

Shikeith, O’ my body, make of me always a man who questions!, 2020Courtesy the artist

Shikeith: Notes towards Becoming a Spill (2022)

A visceral and haunting exploration of Black male vulnerability, joy, and spirituality, Notes towards Becoming a Spill is the first monograph by the acclaimed multimedia artist Shikeith. Following the lyrical artistic expressions of contemporary portraitists such as Deana Lawson, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, and Mickalene Thomas, Shikeith photographs men as they inhabit various states of meditation, prayer, and ecstasy.

In work he describes as “leaning into the uncanny,” the faces and bodies of Shikeith’s collaborators glisten with sweat (and tears) in a manifestation and evidence of desire. This ecstasy is what the critic Antwaun Sargent proclaims as “an ideal, a warm depiction that insists on concrete possibility for another world.” Notes towards Becoming a Spill redefines the idea of sacred space and positions a queer ethic identified by its investment in vulnerability, tenderness, and joy.

Collect a limited-edition screenprint by Shikeith.

See here to browse the full collection of featured titles.

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }

11 Photobooks That Celebrate Black Voices and History

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Grandma Ruby and Me, 2005

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Grandma Ruby and Me, 2005Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery

Race Stories: Essays on the Power of Images, by Maurice Berger (2024)

In Race Stories: Essays on the Power of Images, the late cultural historian Maurice Berger explores the intersections of photography, race, and visual culture. Between 2012 and 2019, Berger first shared these essays in a monthly column on the New York Times Lens blog. Copublished by Aperture and the New York Times, this volume marks the first title in Aperture’s Vision & Justice Book Series, created and coedited by Drs. Sarah E. Lewis, Leigh Raiford, and Deborah Willis, which reexamines and redresses historical narratives of photography, race, and justice.

Edited by Marvin Heiferman, this anthology brings together seventy-one essays that examine the transformational role photography plays in shaping ideas and attitudes about race, and how photographic images have been instrumental in both perpetuating and combating racial stereotypes. From pivotal moments in American history to the ways in which images by LaToya Ruby Frazier, Gordon Parks, Jamel Shabazz, Pete Souza help us see the world anew, Race Stories showcases Berger’s lifelong endeavor to distill complex ideas about racial equity. As Henry Louis Gates, Jr., writes in the book’s foreword: “This collection establishes not only Maurice Berger’s place in the history of the criticism of photography but also his role as a social philosopher determined to underscore, essay by essay, all that unites us as human beings.”

Dawoud Bey, Irrigation Ditch, 2019

Dawoud Bey, Irrigation Ditch, 2019Courtesy the artist

Dawoud Bey: Elegy (2023)

In Elegy, Dawoud Bey focuses on the landscape to create a portrait of the early African American presence in the United States. Renowned for his Harlem street scenes and expressive portraits, this volume marks a continuation of Bey’s ongoing work exploring African American history. Copublished by Aperture and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Elegy focuses on three of Bey’s landscape series—Night Coming Tenderly, Black (2017); In This Here Place (2021); and Stony the Road (2023)—shedding a light on the deep historical memory still embedded in the geography of the US.

Bey takes viewers to the historic Richmond Slave Trail in Virginia, where Africans were marched onto auction blocks; to the plantations of Louisiana, where they labored; and along the last stages of the Underground Railroad in Ohio, where fugitives sought self-emancipation. By interweaving these bodies of work into an elegy in three movements, Bey not only evokes history but retells it through historically grounded images that challenge viewers to go beyond seeing and imagine lived experiences. “This is ancestor work,” Bey tells the New York Times. “Stepping outside the art context, the project context, this is the work of keeping our ancestors present in the contemporary conversation.”

Arielle Bobb-Willis, Austin, 2020

Arielle Bobb-Willis, Austin, 2020Courtesy the artist

Arielle Bobb-Willis: Keep the Kid Alive (2024)

Born in 1994 in New York, Arielle Bobb-Willis first started to experiment with photography at the age of fourteen, when she was gifted an old Nikon N80 film camera by her high school history teacher after her family relocated to South Carolina. Since then, Bobb-Willis has become a rising photographer, having shot commissions for a range of magazines and fashion brands including Vogue, the New York Times, Vanity Fair, Nike, Hermès, and more. In 2024, Aperture published the artist’s first monograph, Keep the Kid Alive. Previously, Aperture had featured Bobb-Willis’s work in the The New Black Vanguard (2017), which highlights the work of fifteen contemporary Black photographers rethinking the possibilities of representation.

In Keep the Kid Alive, Bobb-Willis invites audiences into a brightly imaginative world, filled with dynamic colors, gestures, and unusual poses of the artist’s own creation. Transforming the streets of New Orleans, New York, and Los Angeles into lush backdrops for her wonderfully surreal tableaux, Bobb-Willis makes unforgettable images that expand the genres of fashion and art photography. As Bobb-Willis notes in an interview from the book, “Photography is, and will always be, a daily practice of falling in love with as many things as I can.”

Collect a limited-edition print by Arielle-Bobb Willis from Keep the Kid Alive.

Ernest Cole, Untitled, New York City, 1968–71

Ernest Cole, Untitled, New York City, 1968–71© The Ernest Cole Family Trust

Ernest Cole: The True America (2024)

After fleeing South Africa to publish his landmark book House of Bondage in 1967 (reissued by Aperture in 2022) on the horrors of apartheid, Ernest Cole became a “banned person” and resettled in New York. Supported by a grant from the Ford Foundation, Cole photographed the city’s streets extensively, chronicling daily life in Harlem and around Manhattan. In 1968 he traveled across the country to cities including Chicago, Cleveland, Memphis, Atlanta, Los Angeles, and Washington, DC, as well as to rural areas of the South, capturing the activism and emotional tenor in the months leading up to and just after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. These photographs reflect both the newfound freedom Cole experienced in the US and the photographer’s sharp eye for inequality as he became increasingly disillusioned by the systemic racism he witnessed.

Cole released very few images from this body of work while he was alive. Thought to be lost entirely, the negatives of Cole’s American pictures resurfaced in Sweden in 2017 and were returned to the Ernest Cole Family Trust. The True America marks the first time these photographs have been brought together in a major publication. This trove of rediscovered work acts as a vital window into American society and redefines the scope of Cole’s photographic work.

Collect a limited-edition print from Ernest Cole: The True America. An exhibition of The True America is on view at the Minneapolis Institute of Art through June 22, 2025.

Awol Erizku, Love Is Bond (Young Queens), 2018–20

Awol Erizku, Love Is Bond (Young Queens), 2018–20Courtesy the artist

Awol Erizku: Mystic Parallax (2023)

Awol Erizku’s interdisciplinary practice references and reimagines African American and African visual culture, from hip-hop vernacular to Nefertiti, while nodding to traditions of spirituality and Surrealism. The 2023 volume Mystic Parallax is the first major monograph to trace the artist’s career. Spanning over ten years, the monograph blends together his studio practice with his work as an in-demand editorial photographer, including his conceptual portraits of cultural icons such as Solange, Amanda Gorman, and Michael B. Jordan.

Throughout his work, Erizku consistently questions and reimagines Western art, often by casting Black people in his contemporary reconstructions of canonical artworks. “I always think about my work as a constellation, and a new piece is just another star within the universe,” he asserts in his wide-ranging conversation with the curator Antwaun Sargent, included in the book. “This goes back to the idea of a continuum of the Black imagination. When it’s my turn, as an image maker, a visual griot, it is up to me to redefine a concept, give it a new tone, a new look, a new visual form.”

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

James Barnor, Drum Cover Girl Erlin Ibreck, Kilburn, London, 1966

James Barnor, Drum Cover Girl Erlin Ibreck, Kilburn, London, 1966Courtesy the artist

As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic (2021)

In 1997, Dr. Kenneth Montague founded the Wedge Collection in Toronto in an effort to acquire and exhibit work by artists of African descent. As We Rise features over one hundred works from the collection, bringing together artists from Canada, the Caribbean, Great Britain, the US, South America, and Africa in a timely exploration of Black identity on both sides of the Atlantic.

From Jamel Shabazz’s definitive street portraits to Lebohang Kganye’s blurring of self, mother, and family history in South Africa, As We Rise looks at multifaceted ideas of Black life through the lenses of community, identity, and power. As Teju Cole describes in his preface, “Too often in the larger culture, we see images of Black people in attitudes of despair, pain, or brutal isolation. As We Rise gently refuses that. It is not that people are always in an attitude of celebration—no, that would be a reverse but corresponding falsehood—but rather that they are present as human beings, credible, fully engaged in their world.”

Collect a special vinyl LP, As We Rise: Sounds from the Black Atlantic , featuring a celebratory collection of classic and contemporary Black music made throughout the diaspora.

Deana Lawson, Oath, 2013

Deana Lawson, Oath, 2013Courtesy the artist

Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph (2018)

Deana Lawson has created a visionary language to describe identities through intimate portraiture and striking accounts of ceremonies and rituals. Using medium- and large-format cameras, Lawson works with models throughout the US, Caribbean, and Africa to construct arresting, highly structured, and deliberately theatrical scenes. Signature to Lawson’s work is an exquisite range of color and attention to detail—from the bedding and furniture in her domestic interiors to the lush plants and Edenic gardens that serve as dramatic backdrops.

Published in 2018, Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph was the first book by the acclaimed artist. In 2020, Lawson became the first photographer to be awarded the Hugo Boss Prize. Most recently, Lawson was the guest editor of Aperture’s Fall 2024 issue, “Arrhythmic Mythic Ra,” in which she curated a selection of artists past and present to explore the enigmatic nature of photography.

One of the most compelling photographers of her generation, Lawson portrays the personal and the powerful. “Outside a Lawson portrait you might be working three jobs, just keeping your head above water, struggling,” writes Zadie Smith in an essay for the book. “But inside her frame you are beautiful, imperious, unbroken, unfallen.”

Collect a limited edition of Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph, featuring a special slipcase and custom tipped-on C-print.

Zanele Muholi, Mihla IV, Port Edward, South Africa, 2020

Zanele Muholi, Mihla IV, Port Edward, South Africa, 2020Courtesy the artist

Zanele Muholi: Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness, Volume II (2024)

The South African artist Zanele Muholi is one of the most powerful visual activists of our time. Muholi first gained recognition for their 2006 series Faces and Phases that documents the LGBTQIA+ community, creating ambitiously bold portraits in an attempt to build a visual history and remedy Black queer erasure. From there, Muholi began to turn the camera inward, beginning a series of evocative self-portraits. Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness, Volume II (2024) is the follow-up to Muholi’s critically acclaimed first title featuring their self-portraits.

In their evocative self-portraits, Muholi explores and expands upon notions of Blackness, and the myriad possibilities of the self. Drawing on different materials or found objects referencing their environment, a specific event, or lived experience, Muholi boldly explores their own image and innate possibilities as a Black person in today’s global society, and speaks emphatically in response to contemporary and historical racisms. “I am producing this photographic document to encourage individuals in my community to be brave enough to occupy spaces—brave enough to create without fear of being vilified,” Muholi states in an interview from the 2018 volume. “To teach people about our history, to rethink what history is all about, to reclaim it for ourselves—to encourage people to use artistic tools such as cameras as weapons to fight back.”

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Drop Scene (_1030683), 2018

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Drop Scene (_1030683), 2018Courtesy the artist

Paul Sepuya: Dark Room A–Z (2024)

Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s photography is grounded in a collaborative, rhizomatic approach to his studio practice and portraiture. Through collage, layering, fragmentation, and mirror imagery, Sepuya encourages multivalent narrative readings of each image.

Four years after publishing the first widely available volume of Sepuya’s work, Aperture released Dark Room A–Z, a comprehensive monograph that dives into the thick network of references and the interconnected community of artists and subjects that he has interwoven throughout the images. The volume unpacks Sepuya’s Dark Room series (2016–21), reflecting on the methodologies, strategies, and points of interest behind this expansive body of work. Alongside Sepuya’s work is a range of writings by critics, curators, friends, and the artist. Dark Room A–Z serves as an iterative return and exhaustive manual to the strategies and generative ways of working that have informed Sepuya’s image-making, after nearly two decades of practice.

Ming Smith, Sun Ra Space II, New York, 1978

Ming Smith, Sun Ra Space II, New York, 1978© the artist

Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (2020)

Ming Smith’s poetic and experimental images are icons of twentieth-century Black American life. Smith began experimenting with photography as early as kindergarten, when she made pictures of her classmates with her parents’ Brownie camera. She went on to attend Howard University, Washington, DC, where she continued her practice, and eventually moved to New York in the 1970s. Smith supported herself by modeling for agencies like Wilhelmina, and around the same time, joined the Kamoinge Workshop. In 1979, Smith became the first Black woman photographer to have work acquired by the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Throughout her career, Smith has photographed various forms of Black community and creativity—from mothers and children having an ordinary day in Harlem, to her photographic tribute to playwright August Wilson, to the majestic performance style of Sun Ra. Her trademark lyricism, distinctively blurred silhouettes, and dynamic street scenes established Smith as one of the greatest artist-photographers working today. As Yxta Maya Murray writes for the New Yorker, “Smith brings her passion and intellect to a remarkable body of photography that belongs in the canon for its wealth of ideas and its preservation of Black women’s lives during an age, much like today, when nothing could be taken for granted.”

Shikeith, O’ my body, make of me always a man who questions!, 2020

Shikeith, O’ my body, make of me always a man who questions!, 2020Courtesy the artist

Shikeith: Notes towards Becoming a Spill (2022)

A visceral and haunting exploration of Black male vulnerability, joy, and spirituality, Notes towards Becoming a Spill is the first monograph by the acclaimed multimedia artist Shikeith. Following the lyrical artistic expressions of contemporary portraitists such as Deana Lawson, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, and Mickalene Thomas, Shikeith photographs men as they inhabit various states of meditation, prayer, and ecstasy.

In work he describes as “leaning into the uncanny,” the faces and bodies of Shikeith’s collaborators glisten with sweat (and tears) in a manifestation and evidence of desire. This ecstasy is what the critic Antwaun Sargent proclaims as “an ideal, a warm depiction that insists on concrete possibility for another world.” Notes towards Becoming a Spill redefines the idea of sacred space and positions a queer ethic identified by its investment in vulnerability, tenderness, and joy.

Collect a limited-edition screenprint by Shikeith.

See here to browse the full collection of featured titles.

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }

February 7, 2025

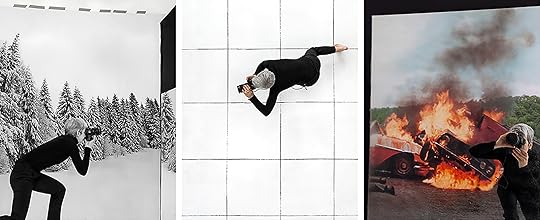

Barbara Probst’s Points of View

Twenty-five years ago, the German-born photographer Barbara Probst ascended a Midtown Manhattan high-rise, arranged a dozen cameras on tripods, and, at 10:47 p.m., leaped across the rooftop as an assistant triggered the shutters via a radio-controlled release system. The resulting grid of black-and-white and color images, a cross between Henri Cartier-Bresson and Michelangelo Antonioni, inaugurated the artist’s Exposures series (2000–ongoing), whose entries each consist of two or more photographs of the same scene, captured simultaneously at different perspectives and time-stamped with Teutonic precision, so that a single second shatters into a puzzle impossible to solve. The Exposures—which span landscapes, still lifes, fashion shoots, portraits, and street photography—may be read as philosophical treatises, each one coolly oppugning their medium’s purchase on the Truth. But they’re also beautiful, suffused with a surprising spontaneity and forensic mystery.

Below, the photographer discusses her work in the context of Barbara Probst: Subjective Evidence, a survey exhibition on view through February 9 at Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Center, which opened last November as part of the city’s seventh FotoFocus Biennial, Backstories.

Installation view of Barbara Probst, Exposure #1 2000, 2002, at the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center, 2024

Installation view of Barbara Probst, Exposure #1 2000, 2002, at the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center, 2024Photograph by Jacob Drabik

Zack Hatfield: Zaha Hadid’s Contemporary Arts Center is so perfect for your photographs. The building has a kind of baroque interplay of spatial compression and expansion that we find in your work too. What was it like making the exhibition here?

Barbara Probst: I came here a year ago with Kevin Moore, the curator of the exhibition, to look at the space. I immediately liked the architecture, because of all these different vantage points and the possibilities of creating relationships between the works in it. My assistant made a model of the space to see how the works can be placed in relation to each other. And it was a very difficult model to build. Hardly any ninety-degree angles.

Hatfield: You also make models for your actual photoshoots as well, right?

Probst: Yeah, or drawings. Sometimes I make clay figures of the people I’m photographing to better imagine how they relate to each other in the shoot and to figure out the angles and viewpoints of the cameras. Shooting with several cameras simultaneously is a complex procedure and needs to be prepared very well.

Barbara Probst, Exposure #185: Munich, Nederlingerstrasse 68, 04.21.23, 2:35 p.m., 2023

Barbara Probst, Exposure #185: Munich, Nederlingerstrasse 68, 04.21.23, 2:35 p.m., 2023Hatfield: People associate your exposures with meticulous orchestration and preparation, but there’s also a lot of improvisation that goes into it.

Probst: Sometimes I feel like a film director with all the details of a scene and all the viewpoints of the cameras in my mind before the shoot. Only when a shoot is planned and set up very accurately can I allow chance and improvisation. And often these unforeseeable changes add something really interesting to the pictures that I couldn’t have envisioned beforehand.

Barbara Probst, Exposure #32: N.Y.C., 249 W. 34th Street, 01.02.05, 5:04 p.m., 2005

Barbara Probst, Exposure #32: N.Y.C., 249 W. 34th Street, 01.02.05, 5:04 p.m., 2005Hatfield: Is there an example of a work in this show that turned out differently than you originally envisioned it?

Probst: Most of them are close to my conception. You need to realize that I hardly ever look through one of the viewfinders during a shoot. Usually, I find a position hidden from the cameras, and from there I release the shutters simultaneously. That’s why my control is limited. Envisioning a shoot and the outcome of the images is one thing—the realities during a shoot, another. For example, Exposure #106 was a shoot on the street with several models inside a building linked to an unstaged scene with a yellow cab on the street downstairs. The shoot was made with twelve cameras. I conceived the twelve images very precisely beforehand, but there was much going on in the shoot that was beyond my control. But even in a shoot like this, I came very close to the images I had in my mind. The works made in the studio, like the close-ups and still lifes, are much more controllable and calculable. It’s a very different way of working for me.

Hatfield: How do you see your work’s relationship to narrative?

Probst: To look simultaneously from different perspectives means to give up the single point of view to which we’re accustomed. It also means no longer believing that the narrative emanating from that single viewpoint is reliable or truthful. I feel that my work actually has a lot to do with life. We all are here on this planet at the same time, and we all look at this world in very different ways. What I have learned from my work is that instead of choosing one way of seeing or another, it’s much more realistic to acknowledge many. In today’s world, this might sound disconcerting, but it can also be a relief to recognize that we don’t really know.

Barbara Probst, Exposure #180, Munich, Nederlingerstrasse 68, 09.11.22, 3:40 p.m., 2022

Barbara Probst, Exposure #180, Munich, Nederlingerstrasse 68, 09.11.22, 3:40 p.m., 2022 Barbara Probst, Exposure #87: N.Y.C., 401 Broadway, 03.15.11, 4:22 p.m., 2011

Barbara Probst, Exposure #87: N.Y.C., 401 Broadway, 03.15.11, 4:22 p.m., 2011Hatfield: There’s a fascinating relationality that emerges through this distinct triangulation of photographer, model, and viewer. Your pictures ask a lot of the viewers’ imagination.

Probst: Yes, in some works, I try to draw the viewer into the images by creating this kind of triangulation. For example, in Exposure #87, there’s the space in which the model is located; there’s the space of the photographer in the backdrop on the wall of the studio, and there’s the “real” space of the viewer, all of which overlap and interact.

Hatfield: I’m interested in your beginnings as a sculptor. I know you were inspired early on by Rodin’s public statue The Burghers of Calais (1884–95), specifically how the figures are arranged nonhierarchically.

Probst: I chose a very classical training as a sculptor, which included daily nude modeling and drawing in the first year. Then I made abstract sculptures and later sculptures that included photography and finally installations containing sculptures and photographs before I dived deeply and exclusively into the medium of photography by starting the Exposure series in January 2000. I still feel that my work is very sculptural. Looking at something from different viewpoints is a sculptural interest. The Exposures can create a spatial impression in the mind of the viewer. The nudes, for example, are the works coming closest to this impression. I look at a nude from different angles, just like a sculptor while modeling one. These nude exposures are a nod to the classical genre of nudes, but they also break with it at the same time by reflecting the making of the pictures by showing all the cameras shooting the nude.

Barbara Probst, Exposure #152: N.Y.C., Broadway & Broome Street, 04.18.20, 10:46 a.m., 2020

Barbara Probst, Exposure #152: N.Y.C., Broadway & Broome Street, 04.18.20, 10:46 a.m., 2020 Barbara Probst, Exposure #124, Brooklyn, Industria Studios, 39 South 5th St, 04.13.17, 10:39 a.m., 2017

Barbara Probst, Exposure #124, Brooklyn, Industria Studios, 39 South 5th St, 04.13.17, 10:39 a.m., 2017Hatfield: The museum’s wall text draws a connection between the multiple perspectives at play in your work and this idea of empathy—of trying to share the experiences of other people. Yet I feel as though your work dramatizes the limitations of knowing other people. Is your work about trying to experience the world from other peoples’ viewpoints?

Probst: You said it beautifully: It dramatizes the limitation of knowing other people. The limitation of knowing how they see the world. Having said that, I’m also interested in empathy, which is about trying to inhabit other points of view. Which requires imagination.

Hatfield: You don’t call your photographs portraits, but close-ups.

Probst: There are works of mine that refer to the genre of portraiture, but they aren’t portraits, because my work is never about the people, their character, or their personality. It’s the relationship between them and the viewer I am interested in, the back and forth of gazes—the gaze of the protagonists at the viewer and vice versa. For example, in Exposure #124, two women look at two different cameras. When you stand in front of the images, the two viewpoints of the cameras merge into one in your eyes. The viewer’s otherwise all-so-certain point of view is in question here.

Hatfield: Throughout the show, it’s remarkable how the subtlest change to an angle can completely transform a composition and its emotional content.

Probst: Often a slight difference in viewpoint can make you see a completely different image, a completely different narrative. Like Exposure #48, the cameras weren’t far apart. But in one image, she seems to be very present and aware of being photographed, and in the other image, the mood is completely different. She looks dreamy and deep in thought.

Installation view of Barbara Probst: Subjective Evidence, at the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center, 2024

Installation view of Barbara Probst: Subjective Evidence, at the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center, 2024Photograph by Jacob Drabik

Barbara Probst, Exposure #48: Munich, Minerviusstrasse 11, 01.06.07, 3:17 p.m., 2007

Barbara Probst, Exposure #48: Munich, Minerviusstrasse 11, 01.06.07, 3:17 p.m., 2007All photographs courtesy the artist

Hatfield: Has your understanding of your own work changed in the almost twenty-five years since you did the first Exposure? Social media has enabled this sort of global simultaneity to accelerate at an unprecedented scale, and the idea of photographic truth has been pretty thoroughly vitiated.

Probst: It certainly has changed over the years. I started out being very conceptual. My interest in the relationship between photography and reality compelled me to conceive Exposure #1 and many other series afterward. Twenty-five years ago, this was a subject less questioned. Today, photography still has a tremendous influence on our subconscious as well as our conscious mind. This issue is inherent to my work, but it moved into the background over the years. Other aspects within the principle of simultaneity emerged, and I immersed myself in different photographic genres. And in more recent years, there’s more playfulness, and often there are references to painting. The still lifes, for example.

Hatfield: You’ve mined this concept for so long without exhausting its potential. You’ve been able to breathe new life into it through what you describe as tropes or clichés.