Aperture's Blog, page 7

May 27, 2025

Sebastião Salgado’s Vision of the Human Condition

Sebastião Salgado, the Brazilian documentarian renowned for his searing black-and-white images capturing humanitarian crises, industrial labor, and environmental destruction, passed away on May 23, 2025, in Paris, at the age of 81. Initially trained as an economist, Salgado transitioned to photography in the 1970s, and dedicated his life to documenting global social issues, all with empathy and uncommon visual power. Aperture had the privilege of publishing several of Salgado’s books throughout his career, including An Uncertain Grace (1990), Workers: An Archaeology of the Industrial Age (1993), Migrations: Humanity in Transition (2000), and Other Americas (2015).

Salgado’s work had an indelible impact on documentary photography, sometimes arousing debate and raising fundamental questions about the power relationships inherent in the field. Even so, his images endure as vivid records of a turbulent and fragile world. In 2014, Melissa Harris spoke with Salgado on the occasion of his exhibition, Genesis, at the International Center of Photography. The traveling show focused on the natural world and outlined how engaged photography was for Salgado a way of life. —The Editors

Sebastião Salgado, Bolivia, 1983, from Other Americas (Aperture, 2015)

Sebastião Salgado, Bolivia, 1983, from Other Americas (Aperture, 2015)Courtesy the artist/Amazonas Images

The timing for the opening of Sebastião Salgado’s eight-years-in-the-making, epic project Genesis (2004–2011), on view at the International Center of Photography from September 19 to January 11, 2015, could not be more ideal or inspiring. With both a UN Climate Summit and a People’s Climate March (expected to include an unprecedented number of participants) also taking place in New York within the next week, Salgado’s exhibition, curated by his wife Lélia Wanick Salgado, is a call to action. Salgado—who has focused on poverty and starvation in his work in the Sahel, child refugees and migrants, the struggle of the landless peasants in Brazil, the end of manual labor, and the displacement of the world’s people at the end of the twentieth century—does not consider himself an activist. Rather, he said to me simply, “I am a photographer. Photography is my life, and my way of life.”

And yes, he is first and foremost a photographer, committed to rendering our quickly evolving world as he experiences it. His view is infused with empathy and a deep engagement with his subject. With Genesis, which was published as a book in 2013, for the first time he has focused on animals and the landscape, as well as people who are still living as they lived for centuries. In his book, From My Land to the Planet (2014), Salgado writes of Genesis: “I wanted to recount the dignity and the beauty of life in all its forms and show how we all share the same origins. . . . For me, it has nothing to do with religion, but indicates that harmony in the beginning that enabled the diversification of the species: this miracle of which we are all part.”

Speaking with him for thirty minutes or so during the final stages of the exhibition’s installation, his sense of wonder and his belief in the planet’s resilience resonate passionately. His prognosis for humanity? Well, he’s more circumspect . . . but still hopeful. What follows are a few excerpts from our conversation. —Melissa Harris

Sebastião Salgado, Fishing in the Piulaga Laguna during the Kuarup ceremony of the Waura Group, Upper Xingu Basin, Mato Grosso, Brazil, 2005

Sebastião Salgado, Fishing in the Piulaga Laguna during the Kuarup ceremony of the Waura Group, Upper Xingu Basin, Mato Grosso, Brazil, 2005© Amazonas Images, Courtesy Peter Fetterman Gallery

Sebastião Salgado, Jaú River, Jaú National State Park, 2019

Sebastião Salgado, Jaú River, Jaú National State Park, 2019© Amazonas Images, Courtesy Peter Fetterman Gallery

Melissa Harris: I’m looking at the reforestation project you and Lélia did in Brazil through your [nonprofit organization] Instituto Terra on the land your parents gave you, where you planted over 2.5 million trees and really reestablished the whole ecosystem. Were you thinking about ecosystems with Genesis?

Sebastião Salgado: These are macro ecosystems. These are huge regions of the planet that are, in a sense, with a certain equilibrium. In this section of the show, all this is Africa. Africa we cannot say is just one ecosystem. But it is a macro region of the planet. If you go from one ecosystem to the other, to the other, to the other, it creates a huge movement of ecosystems—and so you understand it in a more macro way. I made nine trips to Africa in order to get these pictures, working from the desert in the south of Africa to the Sahara Desert in the north of Africa, and working in between in Ethiopia, in Zambia, in Botswana, in Namibia . . .

We had another chapter in the north of the planet with an entirely different group of ecosystems, because I worked in the Kamchatka in Russia; worked on Wrangel Island, north of Siberia; worked with the movement of reindeers in the north of Siberia also, in the Yamal Peninsula; worked in the Brooks Range in Alaska; worked in Canada, the border of Canada and Alaska on the Pacific side; worked in the United States in the Colorado Plateau.

Sebastião Salgado, Eastern Part of the Brooks Range, Alaska, United States, 2009

© Amazonas Images, Courtesy Peter Fetterman Gallery

Harris: What happened to you in this process? Did you experience something you hadn’t experienced before?

Salgado: Incredible. For me, it was incredible, this thing. I did eight years of trips, eight months a year. I went to thirty-two regions or countries. But the big trip that I did was inside myself. I discovered that I am part of all this, that I am part of the animals. That we are part of everything alive in the planet. We are part of this huge equilibrium. You know? For me, it was the most important thing.

We came out of the planet. We must go back to the planet. And I went back to the planet. I thought before, being human, that I was part of the only rational species. That’s a big lie. Because each species is deeply rational inside its own species. We are all—the mineral species, the vegetable species, the animal species—we are all the same. We have the same life. We are all alive.

Once I was with a scientist here in the United States in this incredible chain of mountains—the Rocky Mountains. The guy tells me, “Sebastião, these are young mountains.” I said, “You are lying; these are billions of years old.” He said, “Yes, but this is the second generation of the Rocky Mountains, because the one that was there before was eroded to the ground zero, and the new one is young because she is growing still.” The Rocky Mountains are still growing! Incredible!

I’ll show you a picture of a mountain in Africa that is two days old. We were in front of the mountains here, which are billions of years old. In these I discover all that we are … we are part of all this. We are not important. We give too much importance to ourselves. The life of this land is as important as we are, and we are part of it. I was astonished. You see, [in this picture] a volcano is going off, and it projected this new material, this new mountain. But I had to keep lifting my feet up and down as I photographed, or my shoes would start to melt.

It was amazing. To see these stones when they have just come out of the oven. It was so amazing. So amazing to discover these things.

And working on Galápagos, that was . . . I can show to you a cactus, one cactus, that you can touch—it has no nails that hit you. So soft. So small. But this cactus was born in the middle of these stones that came out of a volcano, which created these lives!

I remember once I was working in Alaska. I was in the Brooks Range. I had a small plane that drove me to a point, and left me there, and came back for me one week or ten days later. Because in Alaska, you cannot fly always. It was June. You have the cold air coming from the Arctic and hot air from inside Alaska, and they meet over this Brooks Range, over this mountain, and it creates a lot of micro-climates. In June, I had a lot of snow, a lot of rain—hot, cold, everything happened there. The plane sometimes was forced to leave me there. I’m sitting there all day long in front of the mountain. You are the planet; you are part of all this together. And you see how the wind cuts at these mountains like a knife, and it creates sand that will create soil, and you see all the vegetation, the small vegetation fights to survive. It’s amazing.

You see, that is the important thing. No? Even before, I photographed all one species, and with Genesis I became so open to every other species.

Sebastião Salgado, Mexico, 1980, from Other Americas (Aperture, 2015)

Sebastião Salgado, Mexico, 1980, from Other Americas (Aperture, 2015)Courtesy the artist/Amazonas Images

Sebastião Salgado, Church Gate Station, Western Railroad Line, Bombay, India, 1995

Sebastião Salgado, Church Gate Station, Western Railroad Line, Bombay, India, 1995© Amazonas Images, Courtesy Peter Fetterman Gallery

Harris: Do you feel differently about man now?

Salgado: Completely different about man. If you consider the history of it: our earth, it started here—the beginning of this wall. At the end of this wall came the animal, then the human. We arrive in the last millimeter here. That’s the important idea. All of this lived before us. All this creation was happening. All these relations, linked to evolution, creating this kind of huge intelligence and evolution that was born from all these things. This for me was fantastic, so great.

Harris: Is there still such a thing as “wild,” Sebastião? Is it possible to find something that is pristine and wild?

Salgado: There are places where no one from Western civilization has gone; there are humans who still live like we lived fifty thousand years before. There are a lot of groups that never made any contact with anyone else. They are the same as us. There is still a percentage of the planet that is in the state of genesis.

Harris: That’s extraordinary.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Salgado: What we think is no more, what has been destroyed, is true—but it is not the whole thing. In the desert, in the Arctic, in the Amazon.

Yes, a good half of the planet—where we built our farms, where we built our agriculture—we destroyed. It’s ecologically destroyed. But a good half is there, and we must hold on to this if we want to survive as a species. Because we are not a danger to the planet; we are a danger to ourselves. It will be the end of our species. Because the moment that we go, the planet renews itself in five hundred years or a thousand years. It’s always done that. The forests come back. The planet can renew quite quickly. It’s not that damaging for the planet. It’s damaging for us. If we want to survive as a species, we must change our behavior.

These chemicals introduced to the planet with war or poison or anything damaging are the chemicals of the planet that we put in concentrated portions through here or through there. But the planet has a capacity to absorb all these things in the long term. Now we live longer lives. And we live outside of nature. We are the only species that has a real consciousness, I believe, that we will be dying. The others just live. And this consciousness that we’ll be dying happens in this modern urbanization. Because when you work with the Indians in the Amazon, they use their body. They have their body to be used. If they cut, they cut. If they break a leg, they break a leg. If they become old, they separate from the others, they go to the forest . . .

If we don’t change our behavior, we’ll disappear very fast. We’ll disappear as a species. You see, we have species that lived for a hundred and fifty million years. They were much more strong than us. The dinosaurs. They’re gone a hundred million years ago. And we are here after a few hundreds of thousands of years, no more than this. We are cutting the trees at a very high speed. They could help save us, and we are destroying the trees.

If we go, there are a lot of species that will go with us. But there are a lot of species that will not go—that will stay. For example, the species inside of the ocean will stay. The process can start again. In billions of years, the humans can come back again.

I believe at least that we must try to go back to the planet, probably not to live more inside the forests—that won’t happen. But we must, at least spiritually, go back into the planet. Feel that we are part of the planet. Add to the beautiful part of the planet, not destroy it. We have money, we have technology; we must have a spiritual comeback to the planet, being part of the planet. If we do this, we can control a majority of the carbon emissions that we have. If you control the quantity of the emissions, we can reduce them. We can use solar energy. We can use the movement of the world, the wind, so many things, to produce energy. We can change our concept of consumption.

Sebastião Salgado, Iceberg between the Paulet Island and the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica, 2005

Sebastião Salgado, Iceberg between the Paulet Island and the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica, 2005© Amazonas Images, Courtesy Peter Fetterman Gallery

Sebastião Salgado, Chinstrap Penguins, South Sandwich Islands, 2009

Sebastião Salgado, Chinstrap Penguins, South Sandwich Islands, 2009© Amazonas Images, Courtesy Peter Fetterman Gallery

Harris: Are you sure you’re not an activist?

Salgado: No, it’s not activism. This is a way of life. It’s different. It’s my life. Activists are putting people in the street. We are planting the trees. I chose the word genesis just to say we live here with the beginning of life. That is also the planting—the beginning of life.

Harris: Sebastião, was it different to photograph landscape and animals?

Salgado: You must respect people. You must respect nature. This [photograph of a giant tortoise] was one of my first pictures in Genesis. To make her portrait was at first impossible. She was afraid. In a moment, I was so tired that I put myself on my knees. When I put myself on my knees, by chance, I was at her level and it happened. I lay down. I started to work with her like this [gestures crawling, using his knees and elbows]. She came to me! And I moved back a little bit, to show her that I was respecting the territory, and she was as curious of me as I was of her. I stayed two hours with her, because she wasn’t afraid of me. It’s fantastic, our planet, and we are just a micro part of this huge life.

Harris: What did you read? Were you reading Darwin? Were you reading poetry?

Salgado: I read Darwin, absolutely. I came to start at Galápagos because Darwin finished all his trip up with the Beagle, his boat. It is here that he finalized all the research to create the theory of evolution, and I came here trying to understand what he understood. I had all the writings. I went to exactly the same place Darwin came.

Harris: So now what are you going to do? What’s next?

Salgado: Now I am working on another story. After last year, I started to do a story with the Indian movement in the Amazon. I want to do a story about the Amazon Indians and the Amazon forest, link the two.

Harris: Man and nature, and the nature of man. Is it complicated to get access?

Salgado: It is. I am working with the National Indian Foundation, the Ministry of Justice. You must get authorization to be accepted by the Indians. It’s a long preparation. Now we were in Brazil this past winter for them to get three authorizations for the next year. I go to three different tribes next year.

This interview was published in Aperture Conversations: 1985 to the Present (Aperture, 2018).

May 16, 2025

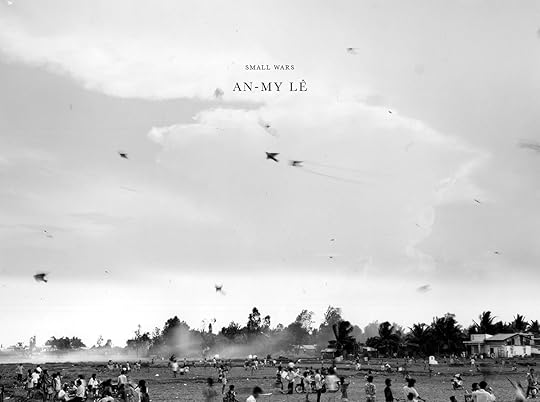

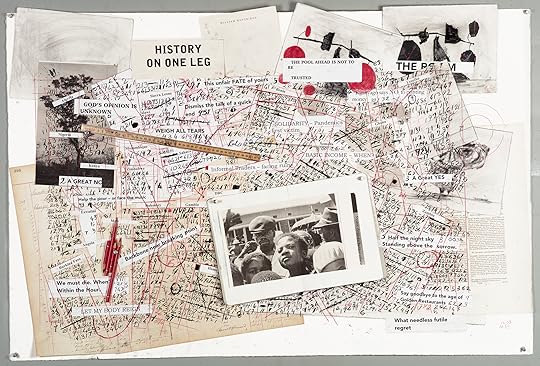

How An-My Lê Makes Meaning from History’s Psychic Debris

It is tempting, when considering An-My Lê’s body of work, now spanning three decades, to mention the depth and scope of the projects, which include vexed approaches to landscape, still life, portraiture, and detailed, photographic studies of social and industrial processes. However, such variegated modes are already evident in Lê’s first monograph from twenty years ago, Small Wars. While debut projects, in any medium, often bear the crude joints where nascent, searching forays were pruned back by mentors or colleagues in graduate workshops or formal schooling, Lê’s first effort marks a subversive, even defiant, commitment to variations in subject, style, and obsessions. It is immediately sure-footed, richly intelligent, and momentous in its seeking.

An-My Lê, Lesson, 1999–2002, from the series Small Wars

An-My Lê, Lesson, 1999–2002, from the series Small Wars  An-My Lê, Bac Giang, Northern Vietnam, 1995, from the series Viêt Nam

An-My Lê, Bac Giang, Northern Vietnam, 1995, from the series Viêt Nam Bringing together three projects—all with distinct approaches—that cross two continents and multiple tonal gradients, what immediately becomes clear is Lê’s dismissal of the novice artist’s anxiety to find and establish a signature, and in theory “marketable,” voice and style. And while Lê’s stylistic language is remarkable across the entire book, she has decidedly allowed the project’s inquiry to determine how these frames are shot, refusing to warp them into the narrow cage of affect and thesis. This is perhaps why, despite being shot on a view camera at slower shutter speeds, the photographs give off the distinct sensation of both being found and fashioned at once. It is not surprising, least of all to a fellow Vietnamese refugee like myself, that Lê’s work would be mimetic of the myriad, layered, and often contradictory history of imperial war, humanitarian crisis, and the violence endured by displaced bodies and their memories. What might be seen, often to Western standards of art-making, as a disorientation, or lack of cohesion or logical accretion, is actually an accurate representation of photography’s more global attempt to fashion meaning, however tenuous, out of history’s material and psychic debris.

An-My Lê, Mekong Delta, 1994, from the series Viêt Nam

An-My Lê, Mekong Delta, 1994, from the series Viêt Nam  An-My Lê, Tien Phuong, 1995, from the series Viêt Nam

An-My Lê, Tien Phuong, 1995, from the series Viêt Nam Most striking of these techniques is Lê’s masterful understanding of blur and stillness. In one frame, a Vietnamese boy aims a slingshot toward the branches of a tree, the coiled charge of his body and the sling’s flexion giving the scene an anticipatory torque. The man to the left is blurred in motion, his presence more weather-like and haunting. In another shot of a typical apartment courtyard in Ho Chi Minh City, a man crouches in critical focus while others, caught in the flow of an impromptu soccer game, foam around him, their gestures both graceful and ghostly, giving a scene of recreation the finest touch of elegy and loss. The tension of stillness as agency, pleasure, play, and rest are potent treatments of the Vietnamese body, whose presence in American media has often been trafficked as corpses. The stillness Lê captures is not one of lifelessness—but of life lived so fully—the arrested movement of these figures, as in another shot of a crowd of people observing a solar eclipse, is a reclamation from the semiotics of war and tragedy.

An-My Lê: Small Wars 60.00 The twentieth anniversary edition of An-My Lê’s acclaimed first book Small Wars, reissued with five new images and an afterword by Ocean Vuong.

An-My Lê: Small Wars 60.00 The twentieth anniversary edition of An-My Lê’s acclaimed first book Small Wars, reissued with five new images and an afterword by Ocean Vuong. $60.0011Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

An-My Lê: Small WarsPhotographs by An-My Lê. Text by Richard B. Woodward. Interviewer Hilton Als. Afterword by Ocean Vuong. Designed by Andrew Sloat.

$ 60.00 –1+$60.0011Add to cart

View cart DescriptionThe twentieth anniversary edition of An-My Lê’s acclaimed first book Small Wars, reissued with five new images and an afterword by Ocean Vuong.

For the past three decades, An-My Lê has used photography to examine her personal history and the legacies of US military power, probing the tension between experience and storytelling.

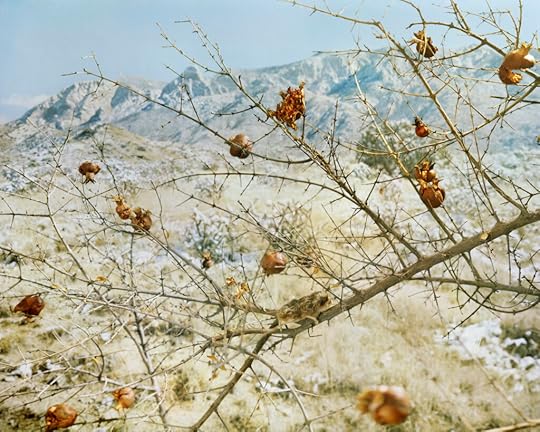

First published in 2005, Small Wars brings together three interconnected series. In Viêt Nam, Lê returns to the country she left in her teens and attempts to reconcile memories of her childhood home with the contemporary landscape; in Small Wars, she engages a small community of Vietnam War reenactors; and in 29 Palms, she documents the preparations of marines in the California desert as they undergo training for conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan. Taken together, this trilogy brilliantly presents a complexly layered exploration of the issues surrounding landscape, memory, and the representation of violence and war.

With great precision and clarity, Lê is able to evoke the work of nineteenth-century landscapes as well as that of the New Topographics—but by weaving in her own personal narrative of refuge and return, she pushes beyond both to produce a uniquely revelatory body of work. The twentieth anniversary edition of Small Wars is a lush reissue of the original, with five additional images and a new afterword by Ocean Vuong, who discusses how these bodies of work resonate twenty years later.

DetailsFormat: Hardback

Number of pages: 144

Number of images: 82

Publication date: 2025-05-27

Measurements: 11.75 x 8.75 x 11.75 inches

ISBN: 9781597115773

An-My Lê (born in Saigon, Vietnam, 1960) is a Vietnamese American photographer, filmmaker, author, and the Charles Franklin Kellogg and Grace E. Ramsey Kellogg Professor in the Arts at Bard College. Lê came to the United States as a political refugee at age fifteen. She received a grant to return to her homeland just after US-Vietnamese relations were formally restored, and traveled there several times between 1994 and 1997. She is the recipient of numerous awards, including fellowships from the New York Foundation for the Arts, John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, and MacArthur Foundation, and her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally. Most recently a major retrospective of her work was organized by the Museum of Modern Art, New York. She is based in New York.

Richard B. Woodward was an arts critic whose essays on art and photography were featured in dozens of monographs, catalogs, and publications, including the Wall Street Journal, New York Times, Atlantic, Bookforum, Film Comment, American Scholar, New Yorker, and Vogue.

Hilton Als is a staff writer and theater critic at the New Yorker. A recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism, he is the author of The Women (1996), White Girls (2013), and Joan Didion: What She Means (2022). He is a teaching professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and an associate professor of writing at Columbia University.

Ocean Vuong is author of the critically acclaimed poetry collections Night Sky with Exit Wounds (2016) and Time Is a Mother (2022), and the novel On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (2019). A recipient of the MacArthur Fellowship and the American Book Award, he was born in Saigon, Vietnam, and is professor of creative writing at New York University.

From the Archive An-My Lê on Vietnam, the Chaos of War, and the Tangibility of Memory

From the Archive An-My Lê on Vietnam, the Chaos of War, and the Tangibility of Memory  Featured 12 Essential Photobooks by Women Photographers

Featured 12 Essential Photobooks by Women Photographers In a maneuver of potent irony, the book builds on this examination of restful, rejuvenated aftermath in Vietnam toward America’s obsession with its own wars. As the epicenter of conflict grows further away, Lê reveals the desperate, even obsessive, desire for American reenactors to reanimate the war in Vietnam in Virginia, a site of Indigenous oppression, chattel slavery, and a major stage in this country’s own civil war. Though the performance of violence carried out on grounds where actual violence occurred is somehow quintessentially American, throughout the book, Lê troubles the fraught idea of national and cultural authenticity. Who is more real, the Vietnamese carrying on a mundane existence, embodying a seldom-observed ordinariness, or the Americans, enacting the cumbersome, boyish mime of the death machine that established America’s ongoing paradox?

An-My Lê, Rescue, 1999–2002, from the series Small Wars

An-My Lê, Rescue, 1999–2002, from the series Small Wars  An-My Lê, Night Operations III, 2003–4, from the series 29 Palms

An-My Lê, Night Operations III, 2003–4, from the series 29 Palms Lê leans into the view camera’s capacity for detail, creating tableaus that, as she’s mentioned in interviews, should be “read” as much as seen. The idea of the photograph offering narrative description is apt considering photography’s historically evidentiary function, but like most “evidence,” meaning is established by composition and context. Here lies Lê’s deft handling of subject matter: her own skepticism for the camera’s ability to tell any complete story, her gaze inflecting not only what is inside the frame but also what’s been left out, either through omission or because it no longer exists.

Lê’s rare achievement is that she makes us see, not just the possibility of the subject, but also the fragility of the frame.

As the book moves toward the final sequence, depicting US military forces training for the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, conflicts that parallel the ethical breaches of the war in Vietnam, the frames start to describe the doomed obsession with war as a cyclical curse in the American dream. As the photographs fan out to show Americans simulating war, replete with politicized faux graffiti curling across building facades, Marx’s warning that “history repeats itself, first by tragedy, then by farce” is echoed with chilling accuracy.

An-My Lê, Infantry Platoon, Alpha Company, 2003–4, from the series 29 Palms

An-My Lê, Infantry Platoon, Alpha Company, 2003–4, from the series 29 Palms  An-My Lê, Colonel Greenwood, 2003–4, from the series 29 Palms

An-My Lê, Colonel Greenwood, 2003–4, from the series 29 Palms Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

But for all its focus on geopolitical shifts, performance, and large-scale composition, Small Wars is, at its core, an autobiographical project—but one that upends the term’s expected conventions. Here, autobiography is not so much confessional revelation of a singular point of view but literally “the writing of a self,” that is, a personhood that includes the trajectory of migration, time, memory, and even the recollection of places where loved ones once inhabited. Here, the self is built through the detritus of a lived life, which includes the ceremonies and rituals of communities Lê has witnessed, both as member and outsider. By drawing with light, as photography’s etymology implies, Lê refigures the lines in the geographical map of her and her family’s migration. Where the diminutive human form common in nineteenth-century American Romantic paintings was meant to entice the viewer toward the capaciousness of “unsettled” land, the same scale in her work reads as an ominous reminder of the Anthropocene’s death drive. For Lê, no personal narrative can be told without the telling of a species-wide propensity for both wonder and destruction. No landscape is without human intervention, often for the worse.

Since a book is, in some ways, a linear form, the presentation of Vietnamese bodies in stillness, rest, potent contemplation and poise, color this monochromatic project, like a die cast in water, with tones of joy, possibility, dignity—and even hope. It is hard to see the tanks in the final section of battlefield exercises and not be reminded of the boy across the world in the first section aiming his slingshot at something outside the frame. Harder still to not see the naivety—one innocuous, the other deadly—in both frames. Lê utilizes the canonical gaze to show us an “elsewhere,” borrowing the omniscient view to reveal who we are, what we always were: small people in small wars trapped in history so large, so momentous, it breaches all compositions. Lê’s rare achievement is that she makes us see, not just the possibility of the subject, but also the fragility of the frame.

This essay originally appeared in An-My Lê: Small Wars, Twentieth Anniversary Edition (Aperture 2025).

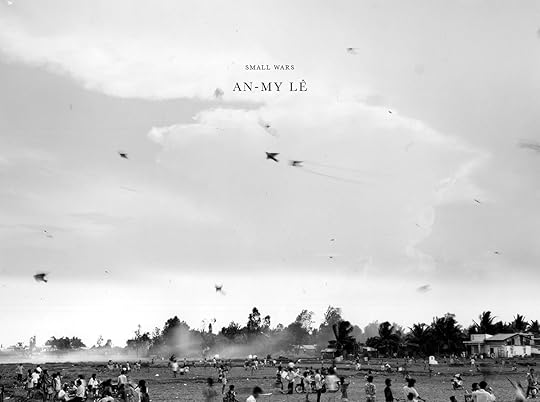

Why Does the Italian Polymath Bruno Munari Still Spark Joy?

Bruno Munari is a monumental figure in Italian twentieth-century design: a polymath who throughout his seven-decade career seamlessly created book series, lamps, toys, ashtrays, and useless machines (a dig at the Futurist obsession with technology). He taught to adults and children with the same unwavering credos: that art, life, and design should be one, that playing is the best education, and that books make life better. That his path should cross with Jason Fulford, a US photographer and publisher working today, is not strange at all. They share an obsession with open-endedness, a childlike sense of wonder, and a love for the printed page. Luckily for us, the publisher of Munari’s books today, Pietro Corraini, brought them together. Corraini fished unpublished Munari photographs from all over Milan and set up a perfect fotochiacchierata (an Italian wordplay meaning “informal chat with pictures”), resulting in a 2024 exhibition with the same title and a book with a slightly cryptic one: 47 Fotos.

Bruno Munari, Untitled, date unknown

Bruno Munari, Untitled, date unknown  Ugo Mulas, Untitled (Bruno Munari), 1967

Ugo Mulas, Untitled (Bruno Munari), 1967© Ugo Mulas Heirs

Chiara Bardelli Nonino: Why forty-seven?

Jason Fulford: It’s a restriction. I picked a couple of numbers I liked: thirty-three, my favorite, and forty-seven, the favorite number of a writer I used to collaborate with, a good friend of mine who died. I knew that I wanted to add pictures of my own, but they had to be fewer than Munari’s, so out of the forty-seven images, thirty-three are Munari’s. Then I did what I usually do to edit: I printed images out small, and I started to play with them, like a deck of cards. When you do that, you just start to see things, to find connections, to feel a flow. Our images were activating each other, like a chemical reaction.

Bardelli Nonino: Basically, you played a Munari game with Munari. How did you discover his work?

Fulford: A friend gave me and my wife a book about his life, and it just . . . blew our minds. Immediately, I wanted to know more, and the more I learned, the more I wanted to know.

Bardelli Nonino: What resonated with you?

Fulford: The fact that he was a Futurist in his teenage years and left them because he felt uncomfortable with their dogmatic nature. The fact that he always made his own way, that he was really difficult to define. His freedom of movement through mediums, from the hardware store to museums.

Bardelli Nonino: He had a penchant for subverting rules. I remember listening to an interview where he said that to spark creativity in children, you have to teach them a rule, and then tell them to break it.

Fulford: He is a great teacher. And there’s a specific type of play that he does. It’s a play that’s rigorous, that’s both on the surface and deep. It reminds me of a quote from a 1970s novel by Don DeLillo. The character is a football coach in college, and when he’s trying to psych up his team before a game, he tells them: “It’s only a game but it’s the only game.”

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Bardelli Nonino: Munari was very invested in the idea of democratizing culture. “While the artist dreams of museums,” he wrote, “the designer dreams of street markets.” He thought that there should not be beautiful things to look at and ugly things to use.

Fulford: Almost every year, I teach a workshop in Urbino, in a school that people such as Bruno Munari or Italo Calvino visited, people who remain major influences in Italy. It seemed like they all came out of World War II with a lot of ideas about rebuilding things, redesigning society.

Bardelli Nonino: And making things simpler. Another Munari quote: “Complicating is easy; it’s simplifying that’s difficult.”

Fulford: One of the things that I learned through studying graphic design is how you can take something complex and reduce it to a simple form. I apply it to my photographs: I want them to have an easy entry point, but with deep levels of things the pictures can give you if you spend time with them or if you think about your life through the picture’s filter.

Bardelli Nonino: Have you ever felt intimidated by Munari?

Fulford: I put a lot of pressure on myself. I worked on the book as if I had to show it to him, and I wanted him to be happy with it. I even tried to add some writing into the book, to channel his voice—but it didn’t feel like me, and it didn’t feel as good as his. So I removed it all. What I like to do with images is to show very specific things that are also open. It’s really difficult, at least to me, to do that with words. You either sound totally pretentious or overly sentimental.

There’s a specific type of play that Munari does. It’s a play that’s rigorous, that’s both on the surface and deep.

Bardelli Nonino: Why is this openness so important to you?

Fulford: Probably two things. One is that the aesthetic experience lasts longer. You can think of pictures that expose something or teach you something, but then you don’t need to look at them again. I remember reading Benjamin Buchloh, a German art critic, talking about Gerhard Richter’s paintings as these puzzles that remain a vexation for the viewer, that resist any attempt to solve them. There’s something in that.

Bardelli Nonino: I remember that Munari in an interview was talking about the importance of toys being open-ended, otherwise they kill children’s creativity.

Fulford: I love that.

Bardelli Nonino: What’s the second reason?

Fulford: When I was growing up, I was raised in a pretty intense fundamentalist Christian faith. The only thing I want to preach now is an open mind.

Jason Fulford, Sea Circus, 2009. Photogram

Jason Fulford, Sea Circus, 2009. Photogram  Bruno Munari, Untitled, date unknown

Bruno Munari, Untitled, date unknown© Bruno Munari and Courtesy Corraini Edizioni

Bardelli Nonino: You know, Munari used to say that his name in Japanese meant “to make something out of nothing.” I think you have a similar approach to photography.

Fulford: I remember talking to a curator once, he was looking at some work of mine and asking questions like, “Why this picture?” And I said something along the lines of, “Oh, I could have just grabbed stuff from the garbage and made something, it would have been the same.” I never heard from him again. But it was true.

Bardelli Nonino: What do you think about Munari’s relationship with photography?

Fulford: I worked on a book last year about Corita Kent, the Catholic nun who became a famous Pop artist, and there’s a lot of crossover. Looking at her archives, I realized that the camera for her was just a tool that was always around. She used it for many different things: to remember something, to make aesthetic images, or as a scanning tool in the process of making silkscreens. Photography was a tool to make something else, in the same way that Munari takes a fork, bends it, and makes it into all these different characters.

Bardelli Nonino: Like in your work, where a photograph can be a whole universe or just there to affect the meaning of another.

Fulford: When I teach, I ask the students to bring images. We print them small, and we put everything into the middle in a big ocean of images. We use them for most exercises, but I don’t let anybody use pictures that they brought themselves. They have to work with other people’s images, so nothing is precious, or definitive. That immediately makes things go faster, looser. As soon as they change the sequence of the images, they realize their meaning changes, that they become alive.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Bardelli Nonino: Photobooks are your primary creative language. Does it ever bother you that they can be kind of niche?

Fulford: It’s hard to say. If you make a thousand or two thousand books, that’s a lot of people but also not many people at all. Numbers are really difficult. People get obsessed with them on social media. Let’s say you have a few hundred people who like something, but you wish it was a few thousand. A few hundred is still a lot of people. I mean, think of how many friends you have.

Bardelli Nonino: Oh, like, three.

Fulford: [Laughs] I was thinking about this today, though. When the Velvet Underground’s first album came out, it didn’t sell very well. But people said that everybody who bought that record started a band, and all of those bands were great. So they had a huge influence. It’s the same with books. You can go back to them at different times in your life, and they tell different stories, because you are a different person. Your book can speak after you are dead, it can find its way to people by accident. I love that a book can do that.

Bardelli Nonino: You can enter into people’s minds through books.

Fulford: That’s why I feel this affinity for Munari —through the printed page.

Bardelli Nonino: What books are you working on now?

Fulford: There’s one I’ve been working on for several years, and I recently printed it in Italy. It’s called Lots of Lots, and it’s eighty pages of grids of images.

Bardelli Nonino: Why the three-by-three grids?

Fulford: Well, Sol LeWitt made two books that I love, Photogrids, from 1977, and Autobiography, from 1980, and mine reference those a lot, in a whimsical, less conceptual way.

Bardelli Nonino: It looks like a captcha test or a beautiful visual Turing test.

Fulford: I hadn’t thought about that. That’s hilarious. I remember one time I got an email from someone who found my 2006 book Raising Frogs for $$$. He said that he loved how I connected the images, that he was working on this computer-learning model and wanted to replicate my way of working, and asked me if I wanted to get involved. It must have been early AI research. I wrote back an email that said something like: “That sounds awful. It sounds like Satan. Why would I want to do that?” I never heard from him again either.

This interview originally appeared in Aperture No. 258, “Photography & Painting,” in The PhotoBook Review.

May 13, 2025

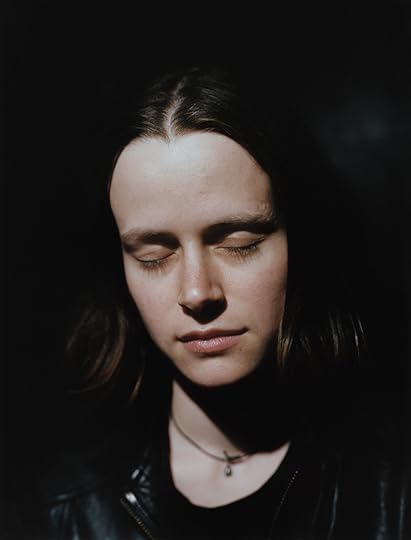

Alana Perino Crafts a Haunting Story of Family and Memory

In a spare, domestic tableau, a bare-chested older man sits pensively on the edge of a nightstand. He looks down at a white bird resting on his hand as a lamp casts light across his body and an empty mattress. Above the bed, a small wooden frame holds a painting of an angel.

The figures within this image—man, bird, angel—permeate Alana Perino’s Pictures of Birds (2017–24), an elegiac series of photographs that searches for meaning in memory and mortality.

Perino, who was born in New York and raised by separated parents, finds home in many places. In 2020, they moved to live with their father, Joe, and stepmother, Letty, on the small Floridian island known as Longboat Key. Perino had begun to photograph their family in the Longboat Key condo a few years earlier, as they noticed Letty first experiencing symptoms of early-onset Alzheimer’s. By the time Perino relocated to Florida, Letty’s condition had worsened.

Alana Perino, Dad and Samuel, 2024

Alana Perino, Dad and Samuel, 2024  Alana Perino, Lori’s Shell, 2023

Alana Perino, Lori’s Shell, 2023 In these years, their sense of home was upended along with the “strange, unwritten contract of the family,” as Perino put it. Letty was younger than Joe, and ostensibly would have cared for him as he aged; now, new family roles formed in which Perino and their sister became caretakers of their stepmother. “The entire island became this eulogized space,” they said. “Everything began to represent her death.”

At night, Letty would speak aloud in the room Perino shared with her. “I realized, after many nights, that she was talking to the same people in the room,” Perino said. “She was talking to ghosts.” Pictures of Birds does not shy away from the idea that spirits dwell in this home, and in many ways, the photographs take comfort in their presence. Perino’s family on their father’s side is Catholic, though the photographer was raised Jewish; in the spiritual treatment of ancestral remembrance and protection, they find common ground among traditions. Outside Longboat Key’s Catholic church, Perino photographs the three wise men conjured as statues shrouded in plastic, an uncanny scene mediating the animate and inanimate.

Perino’s sense of home was upended along with the “strange, unwritten contract of the family.”

Letty died in 2021. Perino continued to photograph their father, sister, niece, and a few other family members until 2024, when their father sold the Longboat Key condo and moved away. The later photographs resonate with the loss and Letty’s continued presence in their lives. A portrait of Perino’s niece Madi floating in a pool recalls an earlier photograph of their father, though where his face turns toward the sky, Madi’s is obscured by her hair as she looks down into the water. In a self-portrait, Perino, eyes closed, lays on their back in a pit dug in the sand on a beach.

Alana Perino, Nina’s Afghan, 2020

Alana Perino, Nina’s Afghan, 2020  Alana Perino, Madi on Stair Lift, 2020

Alana Perino, Madi on Stair Lift, 2020 Letty would repeatedly ask Perino as they photographed around the house, “Why don’t you take pictures of birds?” After all, that is what most people do on Longboat Key. Perino initially decided to photograph anything but the flamingos and egrets of Sarasota County. In time, they came to understand everything they photographed as birdlike, every portrait as a self-portrait. The mutability and fluidity of corporeal figures was never more apparent than in the countless seashells cast aside on the shore. Letty had collected shells for years; Perino viewed them as an extension of nonhuman ghosts, long discomfited by the removal and disruption of a creature’s life cycle. They eventually photographed the shells, too, and made excursions around the island to photograph a wider perspective: the ocean, statues, a shark living in an aquarium.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

“This is when the project really began to expand from this notion of memorializing a really sad event for our family that was prolonged and changed the shape of all of our roles, to a kind of internalization of these realities, of our lived everyday experience with the dead and their presence in our home,” Perino said. “How all of these ecosystems—and this particular ecosystem within Longboat Key, the humidity, the scope of life—it highlights how interconnected all of the different species are and how reliant we are on the shells, the mangroves, the water, and even things like the aquarium to survive and to proceed from one generation to another.” Perino’s photographs rarely depict Letty, who resisted the camera’s presence. In one of her few appearances, only an out-of-focus glimpse of a hand at rest is visible in the foreground. The picture’s title, Nina’s Afghan (2020), refers to the shawl made by Perino’s grandmother and draped over the back of a chair. A painted portrait of their father and Letty hangs on the wall above the chair, their faces just out of the photograph’s frame. Nobody ever sat in that chair. Instead it stayed empty, an outsize and invisible presence filling it, a ghostly apparition just out of reach.

Alana Perino, Letty’s Shells, 2020

Alana Perino, Letty’s Shells, 2020  Alana Perino, Gulf of Mexico, 2022

Alana Perino, Gulf of Mexico, 2022Courtesy the artist

Alana Perino is the winner of the 2025 Aperture Portfolio Prize. A solo presentation of their work will be organized by Aperture in New York City.

This piece appears in Aperture No. 259, “Liberated Threads,” Summer 2025.

A Shimmering Portrait of Contemporary Iran

Everything seems quiet and calm in Sara Abbaspour’s series Floating Ocean, yet quiet and calm are not words immediately associated with the image of Iran, where the photographs were made between 2019 and 2024. The absence of the usual clichés was a deliberate choice by Abbaspour, who imbued the geography of her country of birth with the aesthetics of the place where she discovered portrait photography as a way to tell her stories.

Abbaspour first experienced photography as a tool in her undergraduate program in urban planning and design in the city of Mashhad, in the northeast of Iran. It turned out she enjoyed photographing the city more than trying to plan it, and so she changed course. Her first photography degree at University of Tehran was theory heavy; seeking a practice-based education, she enrolled at the Yale School of Art in 2017.

Sara Abbaspour, Untitled (fire at sunset), 2024

Sara Abbaspour, Untitled (fire at sunset), 2024In her first series, White (2015–16), Abbaspour’s training as an urban planner collides with practical constraints—it is illegal to take photographs in public spaces in Iran. In these images, she captured the remains of houses destroyed in the name of renewal in the pilgrimage city of Mashad. Unseen interior walls, once the site of private lives, become external walls, exposed to the city’s traffic. The municipality’s whitewash inadvertently turns the unsightly into the monumental. “I didn’t make portraits when I was in Iran. I thought I could work with the urban fabric metaphorically to talk about the ideas that I had,” Abbaspour says. The liminal state of these walls, pulled down but never rebuilt, provided her with the kind of poetics that many Iranian artists find useful in a country where direct statements can easily cause trouble with the authorities.

Abbaspour’s move to the US pushed her in a new direction and a new way of looking. “I was lost when I got to the US. I didn’t have any connection to the place. My English wasn’t very good at the time, so I made myself go out every day to photograph people. I started to enjoy the process of meeting and collaborating with them.” Through portraiture, she connected to her new country, and that newfound territory in turn changed the way she photographed Iran when she returned after almost six years.

She began Floating Ocean on her first visit back to Iran, but issues around her US visa stopped her from visiting again to finish the project until the summer of 2024. By this time, she had found a route away from the safety of the metaphor and was settled into the American tradition of portraiture. Influenced by the work of Judith Joy Ross, Mark Steinmetz, and Dawoud Bey, she blended her newfound confidence in photographing people up close with her idea to evade a specific geography. There is poetry here, but no conundrums. Her frames are occupied by individuals at ease with themselves in front of her camera.

Sara Abbaspour, Untitled (girl looking down from rooftop), 2024

Sara Abbaspour, Untitled (girl looking down from rooftop), 2024The name of the series points to the vastness of Iran and how it and she have both changed so radically since she departed for the US. For returning expats these days, the most eye-catching change is the number of women who defy the compulsory Hijab rules, eradicating one of the easy visual markers of the country. In 2020, Iranians protested the Hijab rules after a young woman, Mahsa Jina Amini, was killed in the custody of the moral police who enforce them. Many young people were killed and maimed, and women still face punitive measures for refusal to comply.

Throughout the series, Abbaspour photographed her subjects without the mandatory cover. Without that signifier, the background is the only way to pin the geography. The subjects don’t give away many clues. The girls holding each other or the boys wrestling could be somewhere in the American Midwest. The woman washing her face with a hose could be in South America. Even where some material elements may point to the geography, it is very unspecific, the rooftop in Mashad where a young woman is leaning over the parapet could be any Middle Eastern country. Abbaspour directs our attention to the person in the frame and not their environment. To that end, she deliberately avoids color as she feels it provides too much documentary information.

Abbaspour’s use of black-and-white photography creates a sense of timeless, placeless landscape. As does her framing. Robert Capa’s famous assertion that if your photographs are not good enough, you are not close enough, takes new life in Abbaspour’s method of photographing Iran, where she proves that if you zoom in hard enough, you will discover the universal.

Sara Abbaspour, Untitled (splashing water), 2024

Sara Abbaspour, Untitled (splashing water), 2024 Sara Abbaspour, Untitled (boys wrestling), 2024

Sara Abbaspour, Untitled (boys wrestling), 2024  Sara Abbaspour, Untitled (boy and mirror), 2024

Sara Abbaspour, Untitled (boy and mirror), 2024  Sara Abbaspour, Untitled (two girls in the landscape), 2024

Sara Abbaspour, Untitled (two girls in the landscape), 2024  Sara Abbaspour, Untitled (lighting cigarettes), 2024

Sara Abbaspour, Untitled (lighting cigarettes), 2024Courtesy the artist

Sara Abbaspour is a shortlisted artist for the 2025 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.

How the War in Ukraine Altered Life for a Lost Generation

One evening in the winter of 2022, Daria Svertilova was wandering through one of Kyiv’s central parks. Amid a months-long invasion by Russia, and plunged into darkness by a city-wide blackout, she stumbled on a statue of the archangel Michael, the patron saint of Kyiv. In the Bible, the archangel Michael acts as god’s chief prince; he often appears in dreamlike, prophetic visions of the future that promise the fall of empire.

“It was the darkest time of the year, and I was feeling deeply sad,” she told me. “In that moment, the archangel’s presence amidst the darkness felt deeply symbolic.”

The image she took—Protector of Kyiv—anchors her series Irreversibly Altered, which documents the grief and emptiness of the war in Ukraine. The archangel is situated against a blue-black sky in full regalia, fighting off an unseen foe.

Daria Svertilova, Protector of Kyiv, Ukraine, 2022

Daria Svertilova, Protector of Kyiv, Ukraine, 2022When the full-scale invasion of Ukraine began in February 2022, Svertilova was in Paris, finishing her master’s degree in photography and video at École nationale supérieure des Arts Décoratifs (ENSAD). Ultimately, she decided to postpone her graduation, abandon that project, and respond to the present moment—her present moment.

In the months following the invasion, Svertilova stayed in France, reading updates about the war during the day and dreaming about it at night. The tendency toward expressive images came from her own need to excise her nightmarish visions and the realization that many other talented photographers were documenting the war in a straightforward way. She had no interest in replicating their work when she went back to Ukraine.

The characters and scenes in Irreversibly Altered hint at dispossession and pain, but never show it directly: an empty, red-tinged street a night, portraits of exhausted youths, a still life of dying flowers, shadowy figures floating around dimly lit interiors. While many photographers around her were documenting the war in Ukraine journalistically, Svertilova chose to channel the emotional dislocation around her into impressionistic images instead.

Daria Svertilova, Sana Shahmuradova in her studio during electricity shortages, Ukraine, 2022

Daria Svertilova, Sana Shahmuradova in her studio during electricity shortages, Ukraine, 2022Irreversibly Altered’s aesthetics are also rooted in Svertilova’s childhood training. Growing up, she took drawing classes and found inspiration in Renaissance paintings. She became interested in photography at age thirteen, experimenting with digital SLR cameras and an old Soviet Zenith camera inherited from her grandfather. She moved to Paris to become a working artist.

“I didn’t come from an artistic family, and in Ukraine, art has never really been seen as a “real” profession—something you could do full-time.”

Svertilova admits that while it pains her to see waning support for Ukraine abroad, she feels it’s natural to want to tune out of war, especially explicit images of war. More than ten years after the war started and with no end in sight, she is constantly asking: How can photographers speak about a war in a way that connects to people who are far from it?

Irreversibly Altered offers answers. Rather than trying to capture a broader narrative, Svertilova focuses on her tight knit circle of friends and acquaintances: Artists working in freezing cold studios, former art curators and students who joined the army. They are all part of a lost generation who have undergone a dramatic transformation over the past three years.

There were times when she felt like giving up, especially during constant power outages and living for days without heat and water during the dead of winter. She didn’t.

“I realized that this work is about resistance—the resistance of Ukrainians who live through the war every day, and also my own, personal resistance,” she said. “This project taught me that you have to find strength and keep going, because in the end, the effort is worth it.”

Daria Svertilova, Untitled, Ukraine, 2022

Daria Svertilova, Untitled, Ukraine, 2022 Daria Svertilova, Untitled, Ukraine, 2023

Daria Svertilova, Untitled, Ukraine, 2023 Daria Svertilova,

Hostomel car cemetery

, Ukraine, 2022

Daria Svertilova,

Hostomel car cemetery

, Ukraine, 2022 Daria Svertilova, Roses blossoming in limbo, Ukraine, 2022

Daria Svertilova, Roses blossoming in limbo, Ukraine, 2022 Daria Svertilova, Untitled, Ukraine, 2023

Daria Svertilova, Untitled, Ukraine, 2023Courtesy the artist

Daria Svertilova is a shortlisted artist for the 2025 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.

Life in Afghanistan after the Fall of Kabul

On August 15, 2021, Kabul was in chaos. Photographs of desperate crowds at Hamid Karzai International Airport and refugees packed onto US military planes were shared widely around the world as the Taliban encircled the city. Taken three years after the end of American occupation, Hashem Shakeri’s The Fall of Kabul is a far quieter—and ultimately more disconcerting—image: the photograph shows three young Taliban soldiers, scarcely older than teenagers, looking listless as they guard the dusty top of Wazir Akbar Khan Hill. Clad in sandals and holding Kalashnikovs, they make a pathetic picture of one of the world’s most repressive, fundamentalist regimes. These rough-shod provincials working for starvation wages are among the many Afghans betrayed by their government in Shakeri’s series Staring into the Abyss (2024). Kabul may have long since fallen, but these photographs offer a rare glimpse at how the country slides further still.

Based in Tehran, Shakeri is used to taking pictures in hard-to-reach places, but he’s not a documentary photographer in the conventional sense. Since 2019, when his eerie photographs of derelict public housing estates far from Tehran’s center were published in The New Yorker, he has mostly received international attention from art and fashion magazines. Perhaps that’s because, while Shakeri aims his lens at appalling social issues, his technique is extraordinarily refined. These are beautiful images of ugly truths, and for any photographer, that’s a very difficult needle to thread. Taken with a medium-format camera and 120 film several stops overexposed, an image of unfinished apartment blocks rising beyond mountains of industrial waste, for instance, assumes a searing atmosphere of desolation. Even the vivid, artificial colors of a child’s swing set or a group of oversized pinwheel sculptures do little to enliven the bleached and barren landscape.

Shakeri began experimenting with overexposure in 2018 while shooting in Sistan and Baluchestan, a large but remote Iranian province on the border with Afghanistan. In his Book of Roads and Kingdoms, an atlas of the Muslim world, the tenth-century Persian geographer al-Istakhri described the region as a “fertile” land full of green, irrigated fields along the Helmand River. It was a cradle of ancient civilization stretching back to the settlement of Shahr-e-Sukteh around 3550 BC. Now, the ruins of the neolithic “Burnt City” sit in a drought-riddled wasteland plagued by conflicts over rights to Helmand water. The photographs in Shakeri’s An Elegy for the Death of Hamun (2018) feel appropriately parched, as the people in them wander through fields and ravines lacking any sense of warmth or moisture. Crucially, however, Shakeri gives us glimpses of humanity, like a five-year-old boy dangling from an improvised rope-swing along a dry riverbed. If they locate a certain sublimity in scenes of ecological devastation, these photographs also empathize deeply with the people—mostly members of the oppressed ethnic Hazara minority—who’ve been left behind.

Staring into the Abyss was perhaps Shakeri’s most difficult project to date. As an independent photographer without institutional backing, he was repeatedly threatened by government agents—even as Taliban soldiers agreed to pose for him. “The situation was highly volatile, and everyone lived in uncertainty. I tried to reflect this fluidity and ambiguous, uncertain perspective in my photographs,” he says. There’s no violence on display, but scant sentimentality either. Rather, Shakeri shows the texture of daily life in a place the rest of the world has seemingly forgotten. Soldiers crack open and share a watermelon on the pavement; a boy plays with an albino pigeon in an auto body shop; an assortment of pink clothes and homewares for sale gather dust by the roadside.

While many of the images are overexposed, the series is also a departure in terms of Shakeri’s process. In several photographs, he uses new techniques to conceal their subjects’ identities from the Taliban: a photograph of an underground girls’ school, framed so we only see its pupils’ hands, has been doubly exposed, as if shot through curtained glass. Another depicts a ten-year-old refugee charging his family’s solar panel in a Kabul park, but solarized so that only the panel itself is fully visible, shining white against a field of fire. Shakeri says the photograph inspired the series title, a reference to Nietzsche’s proclamation that “If you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss stares back at you.” But it seems especially true of another haunting, black-and-white image: taken with flash at twilight, it shows ruins in the shadows of the niche that once held the ancient and monumental Bamiyan buddhas, destroyed by the Taliban in 2001. In the wake of violence, their absence has become a yawning void.

All photographs by Hashem Shakeri, Staring into the Abyss, Afghanistan, 2021–ongoing

All photographs by Hashem Shakeri, Staring into the Abyss, Afghanistan, 2021–ongoingCourtesy the artist

Hashem Shakeri is a shortlisted artist for the 2025 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.

A Transfixing Look at Nature at Its Most Unnatural

In environmental science, Shifting Baseline Syndrome is a concept that describes how people’s perception of what is “normal” or “natural” changes over time as ecosystems deteriorate. In other words, each generation accepts the environment they grew up with as the baseline, even if it’s already been significantly altered from its original state, leading to a gradual acceptance of environmental degradation as the memory of the original condition is lost. For Emma Ressel, this idea is central to her project Glass Eyes Stare Back, which questions the human relationship to animals and the environment during an era of increasing climate anxiety. Using museological dioramas of animals as inspiration, Ressel creates her own vibrant and layered studio constructions of flora and taxidermized fauna that veer more toward fantasy and formal experimentation than biological accuracy. “I want to think about how, collectively, we’re living in very confusing and quickly changing environments,” explains Ressel. “The pace at which species and environments are disappearing, and the rate at which natural disasters are happening is so disorienting, and I want to express that in the images.”

Emma Ressel, Shifting Baseline Syndrome, 2023

Emma Ressel, Shifting Baseline Syndrome, 2023These questions of ecology and preservation have always been personal. Ressel has seen winters in her native Maine change drastically over her lifetime, and she’s begun studying the local ecosystem in New Mexico. Her relationship with photography and nature is equally longstanding—Ressel grew up helping her father, a herpetologist and professor, with his research. On his sabbaticals, the two would take trips to the desert, where she would help him catch lizards for his slides, arranging and photographing the reptiles to be recorded and shown to his classes. At Bard, where she studied photography, she was inspired by the work of seventeenth-century Dutch still life painters and began creating scenes and constructing playfully grotesque still life photographs of food.

In 2019, Ressel began making the photographs that would lead to this project in the small natural history museum that housed her dad’s office. “I was thinking about the museum and I just kind of realized that habitat dioramas are still lifes. That’s so much of the same techniques of composition and framing nature and creating a narrative.”

Since the taxidermized animals in her local museum were housed in simple, plexiglass vitrines and lacked any theatrical staging, she began to make her own backdrops from photographs that she printed at large scale. “I started playing with the false backdrop and pairing that with the animal and the scene. I was thinking about how I could start to build these layers of fiction through my constructions, and distort the setting that the animal was in,” she explains.

Emma Ressel, Deep Time Storage, 2024

Emma Ressel, Deep Time Storage, 2024Since these initial experiments, Ressel has explored the collections of natural history museums in the Northeast and Southwest, and her project has expanded to consider the ways these museums and ecological collections inform our ideas around climate and the environment. Deep Time Storage, for instance, is a behind-the-scenes moment—models of two ancient reptiles from different epochs rest amongst filing cabinets, archival boxes, and a large print of a fossil—exemplifying the banal theater of how we preserve, research, and present the history of the natural world.

Images like Dusty Galaxy, in which a turkey’s feathers gleam prism-like against a backdrop of the night sky, or Surrender the Decomposers, in which a mantis is posed against an alien ecosystem of fungus, are more theatrical gestures that suggest imagined ecological pasts, or distant futures. Other photographs feel more immediate and sinister—in Whooping Crane Efforts, we’re grimly reminded of our ecological and political reality. As more and more species and habitats become critically endangered, the research and conservation efforts to stymie environmental degradation are equally under threat from federal funding cuts and policy changes. “I want people to care. I want people to worry with me about the environment and about animals,” urges Ressel. “I don’t want to lead with a message of outright conservation or environmentalism, because I think that we’re sort of bombarded with that day-to-day. But I hope that I can jostle something loose, or prompt a different way to think about our circumstances.”

Emma Ressel, Whooping Crane Efforts, 2024

Emma Ressel, Whooping Crane Efforts, 2024  Emma Ressel, Dusty Galaxy, 2021

Emma Ressel, Dusty Galaxy, 2021  Emma Ressel, Moldy Bee, 2021

Emma Ressel, Moldy Bee, 2021  Emma Ressel, Fruit for the Underworld, 2023

Emma Ressel, Fruit for the Underworld, 2023 Emma Ressel, Red Efts in the Full Moon, 2023

Emma Ressel, Red Efts in the Full Moon, 2023Courtesy the artist

Emma Ressel is a shortlisted artist for the 2025 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.

May 9, 2025

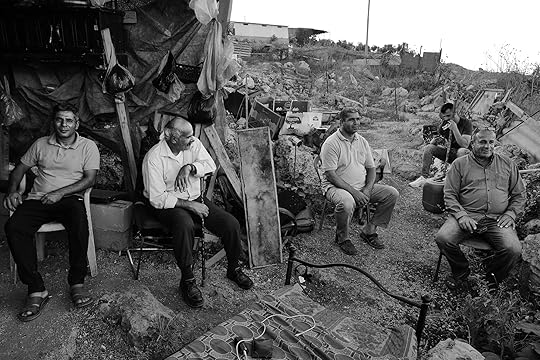

Sakir Khader’s Portraits of Palestinian Perseverance

When Sakir Khader was a young journalist working for a Dutch newspaper in the aftermath of the ill-fated Arab Spring, he wanted to report on the civil war in Syria. His editors refused to send him, so Khader left the paper and joined the Dutch public television broadcasting network instead. There, he undertook a formidable education in the logistics and ethics of documentary filmmaking. Again, he turned his attention to Syria. This time, Khader managed to line up a trip. But the situation was volatile. The regime of Bashar al-Assad had brutally crushed a fledging revolution, setting off an unpredictable conflagration of multiple open-ended conflicts among rebels, insurgents, foreign mercenaries, and more. Things never seemed to get any better—only worse.

Sakir Khader, The shepherd and his sheep, Khattab, Northern Hama, Syria, 2025

Sakir Khader, The shepherd and his sheep, Khattab, Northern Hama, Syria, 2025Khader’s trip to Syria was canceled. But by that time he was no longer taking no for an answer. He decided to apply what he had learned and go anyway, on his own, as a freelancer. As soon as he arrived, Khader began looking for Abdul Baset al-Sarout, the former goalkeeper for Syria’s youth soccer team who had become a rebel commander with the Syrian Martyrs’ Brigade. Sarout was famous for popularizing revolutionary anthems. For that reason, he was hugely irritating to the Syrian regime. Government forces eventually killed him, in 2019, during a chaotic battle in the country’s northwest. Sarout was just twenty-seven years old. Khader was around the same age when he found him, a year earlier, and spent three months living with him and the men of his battalion. Khader made a film and a book and took many photographs, including a portrait of Sarout, close-up, face ablaze with an irresistible smile, tired eyes, and a crown of cherubic curls.

Sakir Khader, A friends’ gathering on the mountain, Rujib, Nablus, Palestine, March 2025

Sakir Khader, A friends’ gathering on the mountain, Rujib, Nablus, Palestine, March 2025 Sakir Khader, The mothers of the Martyrs, Jenin refugee camp, 2023

Sakir Khader, The mothers of the Martyrs, Jenin refugee camp, 2023Blurring the line between still and moving images by making extremely short films, which Khader refers to as “moving still lifes,” as well as singular photographs that play with high contrasts and the conventions of tableau vivant, Khader’s work combines the beauty of Italian neorealist cinema with the horrifying churn of contemporary warfare. He photographs and prints almost exclusively in black and white. He has won a slew of awards. He joined Magnum last summer as a nominee. His second photobook, Dying to Exist, was published last year. His “moving still lifes” add up to over fifty-five hours of footage, which he is slowly transforming into a feature-length film. His first solo museum show, focused on Israel’s occupation of Palestine and titled Yawm al-firak (Farewell Day), after a line from a poem by the great eighth-century poet of the Islamic world Abu Nuwas, is currently on view at Foam in Amsterdam, accompanied by a forthcoming publication of the same name featuring handwritten notes and Polaroids, subtitled Diary of an Invisible Genocide. For Khader, who lives between the Netherlands and Palestine, his success has been both remarkably efficient and impressively assured. More so than achievements or critical acclaim, however, the story of how Khader got himself to Syria reveals how an all-consuming methodology has defined his visual style.

“I like to stay with people,” Khader says. “A lot of the real work happens when the camera is off.”

In Arabic, Khader’s first name means “falcon” or “hawk.” When I spoke to him by phone during a brief stay in Paris, he joked that his name had predestined him to become a photographer. “See? Sharp-eyed,” he said, laughing. Because he was born in 1990, Khader’s first camera was, in fact, an LG Prada smartphone, which he used as a teenager to take pictures in the West Bank district of Nablus. He wanted to be able to look at them after he’d left, to summon images of the homeland in his mind whenever he was away. This was a pre-professional pursuit. By the time Khader landed at the start of his career and was finding his way through several different modes of image making all at once, it struck him that no one in the mainstream news media was paying enough attention to how, in places such as Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Palestine, which had been destroyed by years, even decades, of chaotic yet systematic violence, people were carrying on with their daily lives. Khader’s ongoing bodies of work show people young and old, combatants and bystanders, as they fight, survive, grieve, and mourn but also dance, sing, play games, and experience quieter moments of tenderness or reprieve: men and boys resting sideways on oversize armchairs, a balloon seller eating a Popsicle, two boys waiting for a pair of bumper cars to begin, kids celebrating a holiday in absurdly matching festive dress.

Sakir Khader, On this earth we belong, Rudjib, Nablus, 2023

Sakir Khader, On this earth we belong, Rudjib, Nablus, 2023Khader doesn’t parachute into war zones. He doesn’t join official military embeds. Without narrative or polemic, his images create a withering critique of US foreign policy from the so-called War on Terror until today. He immerses himself in the lives of his subjects, who are people he knows or has come to know. “I like to stay with people,” he explained. “I blend in fully. I build relationships. A lot of the real work happens when the camera is off.”

Related Items

Aperture No. 258

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]Given that he no longer considers himself (or introduces himself as) a journalist, Khader’s status as a Dutch-born, Arabic-speaking, Muslim-observant Palestinian has served him well. It has opened doors to communities that otherwise might not have been so welcoming.

But Khader is also excruciatingly careful not to instrumentalize his or his subjects’ identities. He doesn’t resort to clichés. “I don’t want to shoot olive trees and kaffiyehs,” he said, citing two well-worn symbols of Palestinian struggle. What holds his still and moving images together—and protects them from glorifying the violence that is undeniably his milieu—is Khader’s ability to find in his subjects the same pluck, charm, and relentless perseverance that brought him to Syria six years ago.

Sakir Khader, The neighborhood is no more, Darayya, Syria, 2025

Sakir Khader, The neighborhood is no more, Darayya, Syria, 2025  Sakir Khader, Deep scars in a paradise, Darayya, Syria, 2025

Sakir Khader, Deep scars in a paradise, Darayya, Syria, 2025All photographs © the artist/Magnum Photos

Sakir Khader, Intifada in the village: The battle for Mount Sabih, Beita, Nablus, Palestine, 2021

Sakir Khader, Intifada in the village: The battle for Mount Sabih, Beita, Nablus, Palestine, 2021 To be sure, Khader has photographed a prodigious amount of weaponry, including slingshots, rocket launchers, hand grenades, pistols, and AK-47s. His portraits include men in balaclavas, men missing eyes and limbs, and boys who lift their shirts to show gruesome scars. Although he has, on occasion, captured groups of women joking for the camera, his image world is largely male and shattered by violence. “This is the raw reality,” Khader told me. “I can’t filter it out.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 258, “Photography & Painting,” under the column Viewfinder.

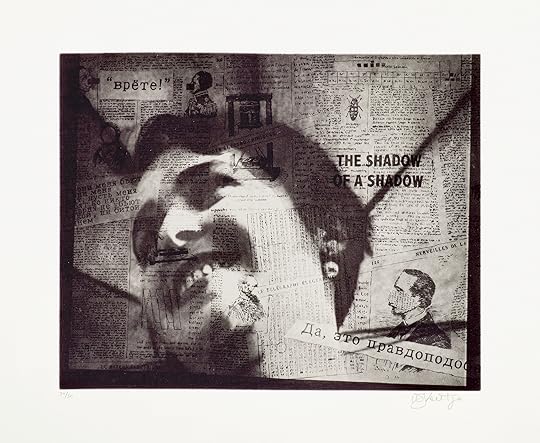

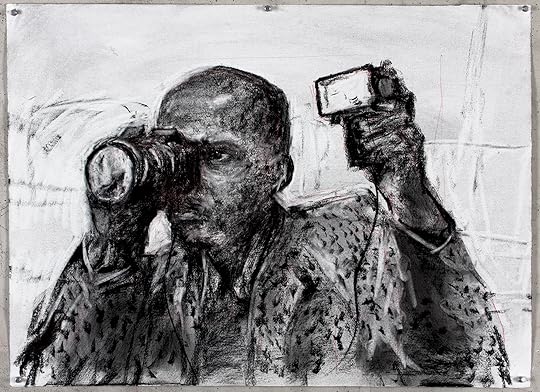

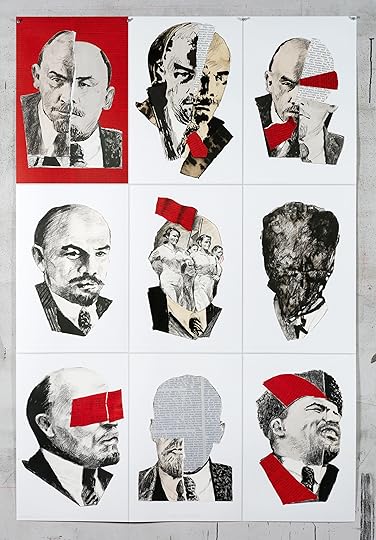

William Kentridge on the Excess of the Studio

This interview originally appeared in Aperture, issue 249, “Reference” (Winter 2022).

In the video artwork Drawing Lesson 47 (Interview for New York Studio School) (2010), William Kentridge stages a split-screen conversation with himself. William Kentridge stubbornly refuses to answer William Kentridge’s straightforward questions: “Can you describe your life as an artist? Can you say, rather, what it is that you did today to give us some sense of how you fill your hours?”

Speaking from his studio in Johannesburg, Kentridge tells the writer and fellow South African Jonathan Cane, in response to those same questions, that he had been in his studio collaborating with editors and artists; working on a large ink drawing for his career-spanning solo show at the Royal Academy of Arts, London; preparing for a major presentation at the Broad, in Los Angeles; and revitalizing a nineteenth-century theatrical technique called Pepper’s Ghost. Internationally recognized for his drawings, animated films, theater and opera sets, sculptures, tapestries, and performance pieces, Kentridge is not, in fact, a photographer. Yet, as he describes, his childhood discovery of forensic photographs recording a terrible massacre, his boxes of reference pictures, and the images Instagram’s algorithm filters into his feed have all informed a photographic approach when Kentridge puts charcoal to paper.

Ian Berry, The police open fire and the crowd flees, Sharpeville, South Africa, March 21, 1960

Ian Berry, The police open fire and the crowd flees, Sharpeville, South Africa, March 21, 1960© the artist/Magnum Photos

William Kentridge, Untitled (The Shadow of a Shadow), 2010. Photogravure

William Kentridge, Untitled (The Shadow of a Shadow), 2010. Photogravure Jonathan Cane: I interviewed David Goldblatt for Aperture in 2015, and I think that’s why they’ve asked me to do this.

William Kentridge: He was a real photographer. [Laughs]

Crane: Can we start with you discovering the box of photographs in your father’s office?

Kentridge: In 1961, when I was six, my father was one of the lawyers representing families at the inquest into the Sharpeville Massacre. He had his study down the corridor in the house we lived in. I went in there one afternoon, and there was a yellow box, which I thought looked like a box of chocolates. It was bright yellow and was, in fact, a box of Kodak 8-by-10 film. I opened it, expecting to find chocolates. So that was already kind of transgressive, to be stealing a chocolate in the middle of the afternoon.

But instead of chocolates, what it contained was a pile of glossy, black-and- white photographs by Ian Berry. Photographs of crowds gathering, and then of the shooting itself. The police on top of Saracens [armored vehicles], photographed from the vantage point of the crowd outside the gates of the police station. And then shots of people running. And then, also, many photographs, both close-up and wider shots, of bodies on the ground—of someone lying with what looked like a small stain on the back of their jacket, and then, in the next photograph, the body rolled over so you can see the exit wound with the whole chest blown open.

It was completely shocking, as if this was my dessert for looking. There was a huge amount of guilt. It was only many years later, when my father and I had a public conversation in Munich, organized by Okwui Enwezor as part of Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life, in 2013, that I had to tell the story again. My father said that, yes, he’d heard the story, but he’d never had a chance to apologize to me for having allowed those photographs to be where a six-year-old could find them.

It was the shock of the forensic image, so much less present now, that gave me a lingering sense of the photograph holding a kind of truth, a record of the world, rather than a construction of the world. Now, Photoshop, algorithms, and filters on your phone give the sense of a photograph being something there to be altered, something not to be accepted at face value.

Crane: You aren’t, in fact, a photographer.