How An-My Lê Makes Meaning from History’s Psychic Debris

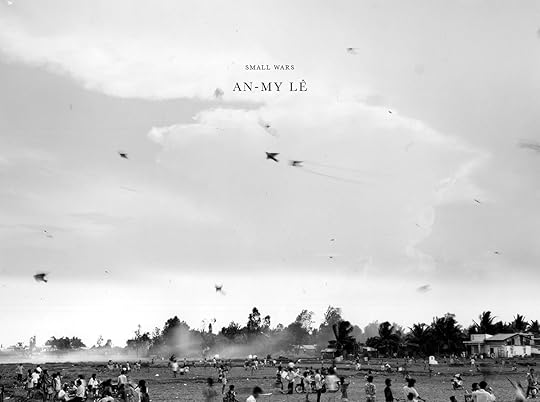

It is tempting, when considering An-My Lê’s body of work, now spanning three decades, to mention the depth and scope of the projects, which include vexed approaches to landscape, still life, portraiture, and detailed, photographic studies of social and industrial processes. However, such variegated modes are already evident in Lê’s first monograph from twenty years ago, Small Wars. While debut projects, in any medium, often bear the crude joints where nascent, searching forays were pruned back by mentors or colleagues in graduate workshops or formal schooling, Lê’s first effort marks a subversive, even defiant, commitment to variations in subject, style, and obsessions. It is immediately sure-footed, richly intelligent, and momentous in its seeking.

An-My Lê, Lesson, 1999–2002, from the series Small Wars

An-My Lê, Lesson, 1999–2002, from the series Small Wars  An-My Lê, Bac Giang, Northern Vietnam, 1995, from the series Viêt Nam

An-My Lê, Bac Giang, Northern Vietnam, 1995, from the series Viêt Nam Bringing together three projects—all with distinct approaches—that cross two continents and multiple tonal gradients, what immediately becomes clear is Lê’s dismissal of the novice artist’s anxiety to find and establish a signature, and in theory “marketable,” voice and style. And while Lê’s stylistic language is remarkable across the entire book, she has decidedly allowed the project’s inquiry to determine how these frames are shot, refusing to warp them into the narrow cage of affect and thesis. This is perhaps why, despite being shot on a view camera at slower shutter speeds, the photographs give off the distinct sensation of both being found and fashioned at once. It is not surprising, least of all to a fellow Vietnamese refugee like myself, that Lê’s work would be mimetic of the myriad, layered, and often contradictory history of imperial war, humanitarian crisis, and the violence endured by displaced bodies and their memories. What might be seen, often to Western standards of art-making, as a disorientation, or lack of cohesion or logical accretion, is actually an accurate representation of photography’s more global attempt to fashion meaning, however tenuous, out of history’s material and psychic debris.

An-My Lê, Mekong Delta, 1994, from the series Viêt Nam

An-My Lê, Mekong Delta, 1994, from the series Viêt Nam  An-My Lê, Tien Phuong, 1995, from the series Viêt Nam

An-My Lê, Tien Phuong, 1995, from the series Viêt Nam Most striking of these techniques is Lê’s masterful understanding of blur and stillness. In one frame, a Vietnamese boy aims a slingshot toward the branches of a tree, the coiled charge of his body and the sling’s flexion giving the scene an anticipatory torque. The man to the left is blurred in motion, his presence more weather-like and haunting. In another shot of a typical apartment courtyard in Ho Chi Minh City, a man crouches in critical focus while others, caught in the flow of an impromptu soccer game, foam around him, their gestures both graceful and ghostly, giving a scene of recreation the finest touch of elegy and loss. The tension of stillness as agency, pleasure, play, and rest are potent treatments of the Vietnamese body, whose presence in American media has often been trafficked as corpses. The stillness Lê captures is not one of lifelessness—but of life lived so fully—the arrested movement of these figures, as in another shot of a crowd of people observing a solar eclipse, is a reclamation from the semiotics of war and tragedy.

An-My Lê: Small Wars 60.00 The twentieth anniversary edition of An-My Lê’s acclaimed first book Small Wars, reissued with five new images and an afterword by Ocean Vuong.

An-My Lê: Small Wars 60.00 The twentieth anniversary edition of An-My Lê’s acclaimed first book Small Wars, reissued with five new images and an afterword by Ocean Vuong. $60.0011Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

An-My Lê: Small WarsPhotographs by An-My Lê. Text by Richard B. Woodward. Interviewer Hilton Als. Afterword by Ocean Vuong. Designed by Andrew Sloat.

$ 60.00 –1+$60.0011Add to cart

View cart DescriptionThe twentieth anniversary edition of An-My Lê’s acclaimed first book Small Wars, reissued with five new images and an afterword by Ocean Vuong.

For the past three decades, An-My Lê has used photography to examine her personal history and the legacies of US military power, probing the tension between experience and storytelling.

First published in 2005, Small Wars brings together three interconnected series. In Viêt Nam, Lê returns to the country she left in her teens and attempts to reconcile memories of her childhood home with the contemporary landscape; in Small Wars, she engages a small community of Vietnam War reenactors; and in 29 Palms, she documents the preparations of marines in the California desert as they undergo training for conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan. Taken together, this trilogy brilliantly presents a complexly layered exploration of the issues surrounding landscape, memory, and the representation of violence and war.

With great precision and clarity, Lê is able to evoke the work of nineteenth-century landscapes as well as that of the New Topographics—but by weaving in her own personal narrative of refuge and return, she pushes beyond both to produce a uniquely revelatory body of work. The twentieth anniversary edition of Small Wars is a lush reissue of the original, with five additional images and a new afterword by Ocean Vuong, who discusses how these bodies of work resonate twenty years later.

DetailsFormat: Hardback

Number of pages: 144

Number of images: 82

Publication date: 2025-05-27

Measurements: 11.75 x 8.75 x 11.75 inches

ISBN: 9781597115773

An-My Lê (born in Saigon, Vietnam, 1960) is a Vietnamese American photographer, filmmaker, author, and the Charles Franklin Kellogg and Grace E. Ramsey Kellogg Professor in the Arts at Bard College. Lê came to the United States as a political refugee at age fifteen. She received a grant to return to her homeland just after US-Vietnamese relations were formally restored, and traveled there several times between 1994 and 1997. She is the recipient of numerous awards, including fellowships from the New York Foundation for the Arts, John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, and MacArthur Foundation, and her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally. Most recently a major retrospective of her work was organized by the Museum of Modern Art, New York. She is based in New York.

Richard B. Woodward was an arts critic whose essays on art and photography were featured in dozens of monographs, catalogs, and publications, including the Wall Street Journal, New York Times, Atlantic, Bookforum, Film Comment, American Scholar, New Yorker, and Vogue.

Hilton Als is a staff writer and theater critic at the New Yorker. A recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism, he is the author of The Women (1996), White Girls (2013), and Joan Didion: What She Means (2022). He is a teaching professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and an associate professor of writing at Columbia University.

Ocean Vuong is author of the critically acclaimed poetry collections Night Sky with Exit Wounds (2016) and Time Is a Mother (2022), and the novel On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (2019). A recipient of the MacArthur Fellowship and the American Book Award, he was born in Saigon, Vietnam, and is professor of creative writing at New York University.

From the Archive An-My Lê on Vietnam, the Chaos of War, and the Tangibility of Memory

From the Archive An-My Lê on Vietnam, the Chaos of War, and the Tangibility of Memory  Featured 12 Essential Photobooks by Women Photographers

Featured 12 Essential Photobooks by Women Photographers In a maneuver of potent irony, the book builds on this examination of restful, rejuvenated aftermath in Vietnam toward America’s obsession with its own wars. As the epicenter of conflict grows further away, Lê reveals the desperate, even obsessive, desire for American reenactors to reanimate the war in Vietnam in Virginia, a site of Indigenous oppression, chattel slavery, and a major stage in this country’s own civil war. Though the performance of violence carried out on grounds where actual violence occurred is somehow quintessentially American, throughout the book, Lê troubles the fraught idea of national and cultural authenticity. Who is more real, the Vietnamese carrying on a mundane existence, embodying a seldom-observed ordinariness, or the Americans, enacting the cumbersome, boyish mime of the death machine that established America’s ongoing paradox?

An-My Lê, Rescue, 1999–2002, from the series Small Wars

An-My Lê, Rescue, 1999–2002, from the series Small Wars  An-My Lê, Night Operations III, 2003–4, from the series 29 Palms

An-My Lê, Night Operations III, 2003–4, from the series 29 Palms Lê leans into the view camera’s capacity for detail, creating tableaus that, as she’s mentioned in interviews, should be “read” as much as seen. The idea of the photograph offering narrative description is apt considering photography’s historically evidentiary function, but like most “evidence,” meaning is established by composition and context. Here lies Lê’s deft handling of subject matter: her own skepticism for the camera’s ability to tell any complete story, her gaze inflecting not only what is inside the frame but also what’s been left out, either through omission or because it no longer exists.

Lê’s rare achievement is that she makes us see, not just the possibility of the subject, but also the fragility of the frame.

As the book moves toward the final sequence, depicting US military forces training for the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, conflicts that parallel the ethical breaches of the war in Vietnam, the frames start to describe the doomed obsession with war as a cyclical curse in the American dream. As the photographs fan out to show Americans simulating war, replete with politicized faux graffiti curling across building facades, Marx’s warning that “history repeats itself, first by tragedy, then by farce” is echoed with chilling accuracy.

An-My Lê, Infantry Platoon, Alpha Company, 2003–4, from the series 29 Palms

An-My Lê, Infantry Platoon, Alpha Company, 2003–4, from the series 29 Palms  An-My Lê, Colonel Greenwood, 2003–4, from the series 29 Palms

An-My Lê, Colonel Greenwood, 2003–4, from the series 29 Palms Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

But for all its focus on geopolitical shifts, performance, and large-scale composition, Small Wars is, at its core, an autobiographical project—but one that upends the term’s expected conventions. Here, autobiography is not so much confessional revelation of a singular point of view but literally “the writing of a self,” that is, a personhood that includes the trajectory of migration, time, memory, and even the recollection of places where loved ones once inhabited. Here, the self is built through the detritus of a lived life, which includes the ceremonies and rituals of communities Lê has witnessed, both as member and outsider. By drawing with light, as photography’s etymology implies, Lê refigures the lines in the geographical map of her and her family’s migration. Where the diminutive human form common in nineteenth-century American Romantic paintings was meant to entice the viewer toward the capaciousness of “unsettled” land, the same scale in her work reads as an ominous reminder of the Anthropocene’s death drive. For Lê, no personal narrative can be told without the telling of a species-wide propensity for both wonder and destruction. No landscape is without human intervention, often for the worse.

Since a book is, in some ways, a linear form, the presentation of Vietnamese bodies in stillness, rest, potent contemplation and poise, color this monochromatic project, like a die cast in water, with tones of joy, possibility, dignity—and even hope. It is hard to see the tanks in the final section of battlefield exercises and not be reminded of the boy across the world in the first section aiming his slingshot at something outside the frame. Harder still to not see the naivety—one innocuous, the other deadly—in both frames. Lê utilizes the canonical gaze to show us an “elsewhere,” borrowing the omniscient view to reveal who we are, what we always were: small people in small wars trapped in history so large, so momentous, it breaches all compositions. Lê’s rare achievement is that she makes us see, not just the possibility of the subject, but also the fragility of the frame.

This essay originally appeared in An-My Lê: Small Wars, Twentieth Anniversary Edition (Aperture 2025).

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers