Aperture's Blog, page 5

August 1, 2025

How Baghdad Is Rebuilding its Arts Community

Iraq’s capital has endured waves of violence, from civil unrest to foreign invasions, leaving little room for arts infrastructure. But the launch of Baghdad Photo Week, the country’s first photography festival, marks a notable turning point. Organized by the photographer Aymen Al-Ameri and his partner Meena Alyassin, who also cofounded the Iraqi arts magazine Henna, the event took place last December at The Gallery, a commercial art space in Baghdad.

The festival’s theme, “Forgotten,” paid tribute to two pioneering Iraqi photographers of the past, Nadhim Ramzi and Hadi Al-Najjar—key figures, alongside Latif al-Ani, in establishing the medium in the country. Much of the photography on view carried an aesthetic shaped by conflict and melancholy. Al-Ameri, Amir Hazim, and Alhassan Jamal Aldeen each capture daily life in high-contrast black and white, depicting ecological pollution, antiestablishment protestors, and the month of Muharram, the start of the Islamic New Year when Shias mourn Imam Ali, whose face is plastered on every street corner.

Aymen Al-Ameri, from the series Halves, 2012–23

Aymen Al-Ameri, from the series Halves, 2012–23 Charles Thiefaine, Ala Allah, Mosul, Iraq, 2018

Charles Thiefaine, Ala Allah, Mosul, Iraq, 2018The program aimed to foster collaboration between diasporic Iraqis, image makers from throughout the country, and international photographers such as Charles Thiefaine, who is based in Paris and has made work about the massive 2019 protests in the capital that left hundreds dead, the subject of his project Tahrir Disobedience. Another body of his work, Ala Allah (On God), offers a quieter, warmer portrayal of daily life in Iraq —a more humanizing view than typically seen abroad.

The wide accessibility of photography, which requires little more than a smartphone, has accelerated its growth in Baghdad. With more photographers emerging, the need for a communal space to share images has become crucial. Al-Ameri, the festival organizer, is committed to working with photographers to develop a diverse range of projects. “We have many good Iraqi photographers, but most of the pictures are of the marshes and Karbala,” he told me, referring to Iraq’s southern marshlands and the Shia pilgrimage city. “We need to see more exhibitions. We donʼt have many galleries, and most photographers are stuck in the same cycle.”

The need for a communal space to share images has become crucial.

Documentary photography remains dominant, shaped by heavy international coverage of wars in Iraq. Abdullah Dhiaa Al-Deen’s work is notable for capturing pivotal political moments and social issues with striking honesty. Professional photography in Iraq often prioritizes income potential over artistry, reflecting the country’s high unemployment rates. Bearing witness to decades of tragedy has been central, but now, with the country’s relative stability and recent urban development, visual narratives are evolving.

Wisam Mutwak, Holy soil, 2023

Wisam Mutwak, Holy soil, 2023Coming to Iraq for the first time as a war correspondent in 2015, Thiefaine noted that many international journalists reproduced similar imagery. “I started to realize there was a big gap between what international photographers show and the lived experience,” he said. Befriending Iraqi youth, Thiefaine noticed that people were very open to being photographed. “Even during the protest, people wanted to show what they have in mind as a society. They were proud of what they were trying to do. I try to stay far from the imagery of violence in my personal work.”

Thiefaine believes that although Western journalism has contributed to shaping Iraq’s maligned global image, the “political situation is changing very fast, which brings about new representation,” pointing to different subcultures, queer culture, and how the festival itself aimed to show diverse perspectives. With Iraq frequently cited as one of the world’s fastest-warming nations, environmental concerns also drove projects on view, such as Tamara Abdul Hadi’s pictures of the iconic marshes and the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, as well as Emily Garthwaite’s photographs of Kurdistan’s biodiverse landscapes and minority communities, including Yazidis, Zoroastrians, and Bahá’ís.

Aline Deschamps, Two friends hold arms and walk around the fairy amusement park, 2022

Aline Deschamps, Two friends hold arms and walk around the fairy amusement park, 2022  Paul Hennebelle, from the series Brown Eyes and Sand, 2016–21

Paul Hennebelle, from the series Brown Eyes and Sand, 2016–21  Claudia Willmitzer, light source of a vehicle headlight spot at the desert of Dasht e lut, Iran, 2014

Claudia Willmitzer, light source of a vehicle headlight spot at the desert of Dasht e lut, Iran, 2014Female representation in Iraqi photography is growing, albeit slowly. Initiatives such as Iraqi Female Photographers, founded by Ishtar Obaid, spotlight women, including Asmaa Turki, Saba Kareem, and Tiba Sadeq. Turki’s work ranges from young ballerinas in Baghdad to serene abaya embroidery in Najaf, vitalizing traditional themes with quiet beauty. Kareem’s images of the marshes and pilgrimages add to this expanding repertoire.

Al-Ameri organized Baghdad Photo Week with minimal funding—an impressive and steadfast effort emblematic of the Iraqi attitude to life. “Habibi, send me photos right now, let’s talk tonight,” he recalls saying to friends just months before the festival. “To deal with Iraqis is not easy,” he added. “Everything is al Allah [with God],” a phrase symbolizing a relaxed approach to deadlines. Creative problem-solving became vital for handling damaged prints and mismatched frames. Censorship presents another challenge. Political content, nudity, and drug-related themes are taboo. Social media offers some freedom, but constraints still limit expression. Despite Baghdad Photo Week’s groundbreaking success, significant obstacles remain. The country’s cultural infrastructure is underdeveloped, with minimal arts education, scant media coverage, and few exhibition spaces. Yet Baghdad Photo Week highlighted not only Iraq’s wealth of talent but also its need to rebuild an artistic community and, after decades of relentless conflict, reimagine its global image.

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 259, “Liberated Threads,” under the column Dispatches.

Richard Misrach and Rebecca Solnit at City Arts & Lectures

Sydney Goldstein Theater

275 Hayes Street

San Francisco

Susan Meiselas and Kristen Lubben in Conversation

Wollman Hall

Eugene Lang Building, Room B500, 65 West 11th Street

New York

July 17, 2025

The Quiet Melodrama of Todd Hido’s Photographs

We all begin in the middle. We are born, and that is the start of something, but becoming an artist happens later, and it happens in relation to what came before. I can tell you that Todd Hido was born in Kent, Ohio, in 1968. I can tell you he came to photography through his love of skateboarding and BMX culture. He’ll tell you that too:

When people skateboard or ride bikes or whatever, they’re doing something cool that only happens for a second or two, so they inevitably want to record it—that’s the nature of it. You’re doing a jump or a trick; you want to record it. What do you record it with? Photography. It’s a totally natural progression. You can capture and share what you’re doing with people. That’s how I got started. I picked up a camera because I wanted to take pictures of my friends.

But it’s a hell of a “jump or a trick” from such snapshots to the kinds of photographs that have made Hido one of the most admired and influential photographers of his generation. When a person picks up a camera and starts to feel photography is for them, it is usually for reasons so complex that simple biography will not do. If you suddenly find that a camera really is your means of expression, it is not so much because it gives you the chance of a brave new start, but because it’s a way of drawing on the unspoken experience of your life lived so far. Making photographs is so often an act of recognition, conscious or otherwise, that what is before you resonates with things that came before. Those things might be direct experiences. They might be movies, picture books, music, or novels. We can never know for sure. And when we look at the photographs of others we are doing something similar: responding now through an elusive then. We all begin in the middle.

Todd Hido, #2133, 1998

Todd Hido, #2133, 1998  Todd Hido, #12084-4048, 2021

Todd Hido, #12084-4048, 2021 Early in the last century, when cinema was very young and photography had not yet found its modern calling, the young artist André Breton and his friend, the writer Jacques Vaché, spent their afternoons in the many movie theaters of the French city of Nantes. They would watch with great intent, but not quite give themselves up to the flickering fantasies. Their hyperactive minds were attuned to the first hint of boredom, that bad turn when a film becomes predictable. Popular cinema being what it is, the moment would sometimes arrive within minutes. Then the pair would rise, fumble to the exit, stroll through daylight to the next movie theater, plunge into the dark, and repeat.

It was a kind of stop-start montage, poetic and even radical. In thrall to chance encounters yet keeping control, Breton and Vaché had no concrete aim beyond the accumulation of mental impressions, which would influence their future work. (The ideas of both men soon shaped the emergence of Surrealism.) They were remaking their own dream world of pictures, in a culture where it was increasingly difficult to distinguish images that were truly one’s own from those received from somewhere else. Living in the mind, pictures can never really belong to anyone. The unconscious does not recognize authors, origins, or destinations. What matters for imagery is resonance and restlessness.

#2024, 1996 1200.00 Collect a special limited-edition print by Todd Hido, from his series House Hunting.

#2024, 1996 1200.00 Collect a special limited-edition print by Todd Hido, from his series House Hunting. $1,200.0011Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

#2024, 1996Collect a special limited-edition print by Todd Hido, from his series “House Hunting.”

$ 1200.00 –1+$1,200.0011Add to cart

View cart DescriptionWell known for his photography of landscapes and suburban housing, the acclaimed American photographer Todd Hido casts a distinctly cinematic eye across all that he photographs. In this image, from his series House Hunting, Hido captures a view of a suburban house at night. Framed by a desolate street, windows glow with light from the home’s interior—quietly hinting at the unknown within. Aperture is pleased to present this exclusive limited-edition print by Hido upon the release of the newly revised and expanded Intimate Distance: Over Thirty Years of Photographs, A Chronological Album (2025), which includes ten years of new work since the book’s first publication. The proceeds from the sale of this limited-edition print directly supports the artist and Aperture’s nonprofit publishing, educational, and public programs.

Intimate Distance: Over Thirty Years of Photographs, A Chronological Album accompanies a related exhibition at the Rencontres d’Arles, France, on view through October 5, 2025.

DetailsTodd Hido

#2024, 1996, from the series House Hunting

Archival pigment print

16 x 20 in.

Edition of 20 and 3 artist’s proofs

Printed, signed, and numbered by the artist

About the Artist

Todd Hido (born in Kent, Ohio, 1968) is a San Francisco Bay Area–based artist whose work has been featured in Artforum, The New York Times Magazine, Wired, Elephant, Foam, and Vanity Fair. His photographs are in the permanent collections of over fifty museums, including the Getty Center, Los Angeles; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; and Los Angeles County Museum of Art. He has authored over a dozen books, including House Hunting (2001), Excerpts from Silver Meadows (2013), Todd Hido on Landscapes, Interiors, and the Nude (Aperture, 2014), and The End Sends Advance Warning (2024). Hido is also an avid photobook collector with a library of over 8,500 titles.

A century on, such a montage can still be poetic, but it barely seems radical. Zapping between channels and clicking through websites are now prosaic activities in an age of distraction. And yet assembling a creative life from fragments, be they one’s own or those of others, is more important now than it has ever been. Some say it is the only creative act left.

Perhaps Breton and Vaché were avoiding conclusions. They preferred to start in the middle and defer The End forever. As we watch a narrative film, the plot and conclusion dominate our experience, but this is not how we will remember it. What we will recall are unpredictable bits and pieces: short strings of association, lucid scenes, colors, spaces, gestures, textures, vectors. In memory, cinema’s images are freed from narrative obligation and resume their essential ambiguity. Narrative is the booster rocket that gets the image pieces into orbit so they can circle the mind, coming around unbidden.

In 1974, the great photographer Walker Evans gave a lecture to students. Like so many artists of his generation, Evans was a lifelong cinephile, and, when asked if he still watched movies, he mentioned Robert Altman’s then-recent films The Long Goodbye and McCabe and Mrs. Miller. He wondered aloud if they were both shot by the same person (they were—by Vilmos Zsigmond). Evans said he thought them “a marvelous bunch of photography” and something to really learn from.

Todd Hido, #12083-3664, 2020

Todd Hido, #12083-3664, 2020  Todd Hido, #12081-2383, 2021

Todd Hido, #12081-2383, 2021 Influence cannot be confined to one’s own medium. It comes from anywhere. A line from Virginia Woolf or Raymond Carver may strike us with a force comparable to that of a snapshot. A musical phrase may dance like a picture. A word may link one ineffable vision to another. A shot from a film can have more vitality as an isolated image than it does in the service of a story.

Still photography has never been too burdened by the weight of narrative. Since its essence lies in the thingness of things observed, it has only ever dealt in description and suggestion. Moreover, its muteness and fixity are so different from the noise of the spoken word. Even when sequenced carefully across pages, an arrangement of silent photographs will always feel a little provisional, the concrete particulars of each image finessed by so many open questions. What if this picture is placed alongside this one? What if a turn of the page is a shift from reverie to piqued curiosity, or political urgency? What if a change of scale causes a minor tremor in your attention? What if a smudged view of an unknown landscape resonates with the smudged mascara of an unknown woman?

Todd Hido, #1447-a, 1995

Todd Hido, #1447-a, 1995  Todd Hido, #11506-3940, 2016

Todd Hido, #11506-3940, 2016 Good pictures in a book are the “marvelous bunch of photography” that a good movie is in the memory.

The photographs gathered in Intimate Distance were made over the course of the last thirty years. During that time, Todd Hido has worked on several substantial groups of pictures, often simultaneously. When each group has come into focus as a project, Hido has published it as a book and exhibited it as a suite of prints. But what we have here is a chronological sequence drawn from the full depth and breadth of his singular oeuvre. It’s not exactly a retrospective; instead, like a novelist reviewing his manuscripts or a filmmaker going back to the editing suite, this book hints at its maker’s development and working processes. We are invited to see how Hido has spiraled through his motifs and preoccupations. True to the book’s title, you will find several kinds of intimacy here. You will also find the ambiguous distances signaled by the titles of some of his previous books: House Hunting, A Road Divided, Roaming, Between the Two, Outskirts. Wandering through and around, searching and returning.

If these photographs and their arrangement seem narrative, it is because they suggest untold tales and possibility. The suggestions are as much yours as they are Hido’s, and as likely to come from cinema and literature as they are from personal experience. Hido is an avid movie lover who says the TV in his house is always on. Impressions sink in and leave their traces, but even he is not sure what they are.

Todd Hido, #2479-a, 1999

Todd Hido, #2479-a, 1999  Todd Hido, #7373, 2008

Todd Hido, #7373, 2008 These photographs are made slowly—there are few grabbed shutter instants here—but like so much of the best photography, they seem to have been prompted by flashes of recognition, when the world-as-image corresponded to something half-remembered, unstated but insistent. The images are sumptuous and full of things to look at: landscapes, byways, signs, suburbia, interiors, fabrics, and faces. But they give the equally strong impression that this factual-fictional world is less than full. Each image is plenty, yet not quite enough. For all the river of color, for all the thickness of these atmospheres, Hido has the economy of a minimalist.

Can one empty out a photograph? How little would it need? A road trip can be sketched with little more than a horizon and a telephone pole. The anomie of suburbia is all in the paint palette of a real estate brochure washed in sodium light. A door with a number—216—is an unknown motel room, allocated at random. A young woman in such a room is enough to signal hope, fear, loss, or desire. Fill in the gaps as you wish; perhaps your unconscious has already.

The iconography here is perfectly familiar. Hido is confident enough to inhabit clichés and emerge with something that is his own. His photographs confirm the idea that in much of American culture, motifs matter only because of the inflections they are given. Consider the picket fence: it has been a permanent presence in the nation’s literature, cinema, and photography because it is so open to interpretation. Think of the fence at the start of Mark Twain’s 1876 novel The Adventures of Tom Sawyer: “Tom appeared on the sidewalk with a bucket of whitewash and a long-handled brush. He surveyed the fence, and all gladness left him and a deep melancholy settled down upon his spirit. Thirty yards of board fence nine feet high. Life to him seemed hollow, and existence but a burden.”

Todd Hido, #3737, 2005

Todd Hido, #3737, 2005  Todd Hido, #2690, 2000

Todd Hido, #2690, 2000 That picket fence is and isn’t the picket fence of Paul Strand’s celebrated photograph of 1916, or the one in Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life, or those in the 1950s TV series Father Knows Best and Beulah; or the glowing white fence that opens David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, set against that too-blue sky and lurid roses. All these fences divide home from town, private fear from public life, and are loaded in so many other ways too.

Since appearing on the cover of his 2001 book House Hunting, Hido’s own interpretation of the picket fence has become something of an emblem for his work as a whole. It is an image that permits the memory of all the fences that have come before. Its composition has the simplicity of a nineteenth-century illustration; the architecture it describes has existed for generations. The colors, seductive and queasy, have the infinite gradation of very mixed emotions. The fence itself, like all American fences, is in need of attention. Behind the house’s curtains, something or nothing may be going on: one room has the warmth of a bedside lamp, while another has the cooler light of a TV screen. No drama is represented here. Instead, we have the drama of representation itself, and perhaps the drama of photography itself.

A camera is a dark chamber pierced by light. Through a small opening the light passes, falling as an inverted image on a sensitized surface. The light may be too bright or too dim, but adjustments can be made: apertures, shutter speeds, film sensitivities. Such chambers abound in Hido’s work. By daytime, the rooms he photographs are darkly sequestered spaces, resisting the sun. At night, houses become glowing chambers.

Todd Hido, #1637, 1996

Todd Hido, #1637, 1996  Todd Hido, #6405, 2007

Todd Hido, #6405, 2007 To move through the pages of this book is to move from one chamber to another, feeling how light itself can be observed, calibrated, and made thinkable. The fall of light can be affectionate or indifferent or even cruel, just like the human life it illuminates. In one photograph, a stained mattress is propped against the window of an exhausted room. Bright sunlight pushes around its edges and seeps into the space. You can see how light is a force. It can be harnessed, or even be created with fire or electricity, but it is a force, with all the beauty of flowing water. Whatever is happening in that room finds its echo in the camera that is there to make an image of it. The room preceded the camera’s presence, but without the camera you would never have seen it. Hido entered, exposed the negative that had the potential to become this picture, left the room, and walked out into the light. Everything else that makes the picture what it is—Hido’s intentions or yours—is conjecture.

For some of his landscape images Hido has used the chamber of his car. Cruising rural roads, he scrolls through endless vistas in the hope of catching some epiphany of light and form. Many a “road trip” photographer has talked about how their windshield feels like cinema’s wide screen—it is a framing device. Hido’s windshield is more than that: you can see it in his images, diffusing and refracting the view. The glass also catches Hido’s own breath, which condenses into cataracts before him. He stays in the car with his camera, looking out, shooting out, a chamber within a chamber.

To move through the pages of this book is to move from one chamber to another, feeling how light itself can be observed, calibrated, and made thinkable.

In 1975 Roland Barthes published a perfect little essay, “En sortant du cinéma” (On leaving the cinema). Its subject is the pleasurable yet strange sensation that comes over us when a film is over. Our body must awaken, “a little numb, a little awkward, chilly,” as he puts it, “sloppy, soft, peaceful: limp as a sleeping cat.” Our mind must also move from one state, one reality, to another. We need time to adjust. It is a precious feeling, but so transitive that we are rarely encouraged to take it seriously. Barthes does. The sensation of leaving that dark chamber can be quite dramatic. (Maybe this is what Breton and Vaché loved, or feared, prompting them to choose their own moments to leave.) Watching a film in a cinema, you are supposed to forget where you are. To enter the illusion, the apparatus must melt away. At the end of the film you mentally reenter your surroundings and once again become aware of the movie theater, only to leave it.

This never really happens with still photography. There is no comparable suspension of disbelief. Yes, a photograph or book of photographs may be immersive, but not in the cinematic sense. The pleasures are very different. Looking at photographs, we never quite “lose ourselves.” And in a book, it is in the mental movement from one image to another that meaning is made, without forgetting where you are. Hido’s pictures are as immersive as any in contemporary photography, but the pleasures of his sequencing keep churning. One is pulled into the imaginative depths of a picture, only to be lured toward another and another. And unlike a narrative movie, a book allows one to feel what one is feeling—to grasp the pleasure and the churn consciously, as sensations in themselves.

Todd Hido, #11685-2448, 2017

Todd Hido, #11685-2448, 2017  Todd Hido, #6426, 2007

Todd Hido, #6426, 2007All photographs courtesy the artist

Before a movie is made, the director or location scout goes looking for places to shoot. Usually they will take a still camera. If you have ever seen the pictures made on such reconnaissance trips, you will have sensed their strange status. They are documents, records of places, yet they are also invitations to propose, or suppose, what has not yet happened but could. A good location photograph will leave space for imaginative projection. I think Hido’s landscapes and townscapes have this quality. A similar feeling is present in actor portraits made by casting directors, and in the preliminary photos taken of fashion models on go-sees for style magazines. Look at Hido’s photographs of solitary women that populate this book. In each case there was an encounter, of which the photograph is the palpable result, but what, or who, was there? A player, star or extra, with an unwritten script.

So many of Hido’s images hinge on this duality: the retrospective and the prospective. The fact and the wish. The presence and the possibility. His statement that he “photographs like a documentarian but prints like a painter” confirms this, and indicates how the effect is rooted in the very substance of his pictures. It is a constant balancing act, avoiding the sentimentality of “what was” and the cheap melodrama of performed fiction.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

But what of the found photos that punctuate the sequence of Hido’s own images in this book? They appear to have been rescued from family albums long abandoned, and they also express something of this duality. They come from somewhere undoubtedly specific but unknown to us, and their future is uncertain. For now they have found a resting place amid these porous landscapes and portraits, and the mix is heady. But who knows? It is in the nature of photographs to wander and recombine.

Hido himself has wandered. He has shuffled his deck of photos, spread it out, and made his choices. There is great value in looking back, and risk too. Photographers know this better than most. Can Hido really know who he was when he made an image thirty years ago, or even last year? Which is the best moment to be making that call? Now is as good as any. What really matters is the honesty and the intensity of the backward glance, while accepting that one can never know one’s own motivations absolutely. In a printed book the choices are definite. The sequence is locked, and the binding is tight. Even so, for all the fixing of appearances, for all the stopping of time and reshaping of history, everything flows onward around a photograph; sooner or later, it gets swept along. As Hido himself once put it: “Whatever I have accomplished, I just keep going.” This book is a milestone on that journey.

This essay originally appeared in Todd Hido: Intimate Distance (Aperture, 2025).

July 11, 2025

Richard Misrach on the Eerie Grandeur of Global Trade

Phenomena that appear blue at one time will at others look orange or golden or gray or black as light and weather shift, because color is not inherent in land or water or sky, but an interaction between light and surface, because change is the one constant, because there is a rhythm of light that, like the tides, comes and goes daily. Ships that appear on the water may themselves be coming or going, may be carrying products for import or export, may belong to global conglomerates or oil corporations, may have been on the open ocean for weeks before they came into the San Francisco Bay. Some are fossil fuel tankers, more are cargo ships. The word cargo, meaning burden or load, was itself exported from Spanish to English in the seventeenth century.

Cargo as in burden, horizon as in horizontal. This is a place divided by the horizon line between water and sky, a world drawn together by the enchantments of light, a world of moods made by time of day and weather, by clouds and sun and wind and fog, a world that if you ignore the ships is primordial, sublime, spacious, serene on clear days, other days battered by wind or smothered in fog or dull with smog that gives the sky brown edges. Or maybe two horizons of sorts, two horizontals, waterline and skyline. Horizon as the meeting place of water and air, or sky and earth, lends a kind of stability in a landscape—seascape—skyscape—made of the eternal instability of the cycles of light and darkness, seasons, tides, weather, and human histories.

Richard Misrach, Cargo (February 1, 2024, 7:53 a.m.)

Richard Misrach, Cargo (February 1, 2024, 7:53 a.m.)  Richard Misrach, (November 22, 2021, 6:41 a.m.)

Richard Misrach, (November 22, 2021, 6:41 a.m.) But the ships are not easy to ignore. Sometimes, they appear as a kind of transgression against the aesthetic grandeur, a disturbance in the space, an industrialization of what still seems natural. At other times, in their monumental size, the way their hulls catch the light, their own lights in the gloaming, they are beautiful themselves. They are reminders that the world comes into this bay again and again as commerce, the way it came in as military might in the decades when the Bay Area’s ports and bases were strongholds meant to defend the West Coast against invaders who never came1, or to launch troops and armadas into the Pacific theater of war. They are easy to see, but it’s less easy to perceive the immense environmental harm of the shipping industry, of mass consumption, of the fossil fuel that fills the hulls of the tankers come to load and unload the foul stuff on which our world runs. These ships carry specific burdens, but they also transport the burden of the industrial age’s consumption and production and its impacts. They carry a burden, a cargo, of meanings.

Richard Misrach, (January 11, 2022, 2:01 p.m.)

Richard Misrach, (January 11, 2022, 2:01 p.m.)  Richard Misrach, Cargo (January 18, 2024, 7:57 a.m.)

Richard Misrach, Cargo (January 18, 2024, 7:57 a.m.) The Golden Gate is a breach in the great wall of the coast range, the one place for hundreds of miles where major waterways exit the continent and enter the Pacific Ocean. It’s a place for ships, for sea creatures, and for weather to enter. The low-lying clouds we call fog often stream through the gap in a long snaking column heading east, though other times the fog spreads more widely across land and water like a gray blanket. I say “a place” and “it,” as if it is singular, but the San Francisco Bay is many things, even by name: the Delta and Suisun Bay up where the rivers draining the Sierra Nevada meet tidal water, San Pablo Bay to the north, San Francisco Bay otherwise, with Richardson Bay tucked between Sausalito and Tiburon.

Technically, it’s not just a bay, which is merely an inlet on a body of water, but also an estuary, a liminal space where waters join, a realm between fresh water and salt water, between water following gravity downhill and tidal water undulating according to the pull of the moon. The fresh water is the result of rainfall and high-altitude snowmelt from clouds that arose over the Pacific and moved east on ocean winds, so that all these forces—the sea, the clouds, the precipitation, the snowpack and spring thaw, the bay—are one great annual pulse of water.

Hydrological map of Northern and Central California

Hydrological map of Northern and Central CaliforniaThe bay is the terminus of this western slope’s water system and the beginning of the Pacific, which covers one-third of the globe. It mediates between the rivers and the ocean, a meeting place, a gateway. Though the term gate has been appended only to the San Francisco and Marin Headlands through which the bay meets the sea, it’s all a transition zone. US Army Lieutenant John C. Frémont gave the Golden Gate its name in 1846, as part of his campaign of American expansion, when California still nominally belonged to Mexico but was largely inhabited by the some two hundred Indigenous nations that had been here for millennia. In the Bay Area, those included the Ohlone, Coast Miwok, Pomo, Patwin, and Wappo, all of whom are still here.

To live here is to stand at the far end of what was once called Western Civilization and to know that the solid land on the other side of that largest of all wildernesses is what was once called the Far East. The Golden Gate (the subject of another Richard Misrach book) is a threshold. It is a deep gulch through which enormous quantities of water surge inward and ebb outward, by one estimate about three and a half times the volume of the Mississippi River at its mouth, on average, but sometimes twice that figure. The dangerous power of that tide is well known to those who venture into the waters.

Richard Misrach, Cargo Ship and Golden Gate Bridge, 1999

Richard Misrach, Cargo Ship and Golden Gate Bridge, 1999  Richard Misrach, (February 26, 2024, 6:13 a.m.)

Richard Misrach, (February 26, 2024, 6:13 a.m.) I have spent more than half a century on the shores of San Francisco Bay, gradually learning its inexhaustible meanings and fluctuating spaces and watching the endless change of light and weather and tide, sunrises and sunsets, sunny days when the water is the color of the sky when seen from afar, even if it is green up close. On gray days, when the light breaks through but the water reflects the clouds, the bay sometimes looks like beaten silver, solid and utterly opaque. When I cross the Bay Bridge I often glance south, to where the huge cargo ships seem monumental and still, as if the arrangement were permanent, as if the vessels were knights and bishops resting on water as solid and stable as a chessboard. As if the players had left the room midgame.

These ships carry specific burdens, but they also transport the burden of the industrial age’s consumption and production and its impacts.

In another sense, the players had never been in the room but beyond it, as the multinationals that owned the ships or the products they carried, as the hands moving these pieces across the larger chessboard of the seven-tenths of the earth’s surface that is liquid, as the invisible forces behind these eminently visible large objects, as the laborers at every stage of producing and loading and transporting and unloading the goods and getting them to consumers. From the shore, the workers managing the ships are rarely seen, and nothing much discloses the content of the containers, stacked up like colossal bricks. Every once in a while a news story includes the crews and captains of vessels like these, offering brief glimpses into their lives and labor and the law of the sea and the ports.

Cargo (January 2, 2024, 7:06 a.m.) 10000.00 Eerie and undeniably beautiful, Cargo (January 2, 2024, 7:06 a.m.) is from Misrach’s series documenting often-unseen patterns of global trade and commerce at the Port of Oakland, California.

Cargo (January 2, 2024, 7:06 a.m.) 10000.00 Eerie and undeniably beautiful, Cargo (January 2, 2024, 7:06 a.m.) is from Misrach’s series documenting often-unseen patterns of global trade and commerce at the Port of Oakland, California. $10,000.0011Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

Cargo (January 2, 2024, 7:06 a.m.) $ 10000.00 –1+$10,000.0011Add to cart

View cart DescriptionAperture is pleased to release this limited-edition print by Richard Misrach on the occasion of the publication Cargo (Aperture, 2025).

Richard Misrach works in grand scale. Photographing throughout the American West since the mid-1970s, he has produced a wide-ranging survey of the political, environmental, industrial, and social changes of the last half-century. A pioneering documentarian, Misrach constructs large-format compositions that lean into the tension between formal aesthetics and political idealism. He formed what would become his epic masterpiece Desert Cantos, in 1979; the ongoing work remains an indelible record of the human impact on nature.

In 2021, Misrach began to document the Port of Oakland from a vantage point overlooking the San Francisco Bay. Cargo (January 2, 2024, 7:06 a.m.) is among the works in this series. Vast, painterly seascapes pockmarked with ships take new meaning for Misrach, referencing global supply chain issues and the realities of global capitalism. “To me, the work I do is a means of interpreting unsettling truths, of bearing witness, and of sounding an alarm,” Misrach has said. “The beauty of formal representation both carries an affirmation of life and subversively brings us face to face with news from our besieged world.”

Proceeds from the sale of this work directly support Aperture’s nonprofit publishing, educational and public programs. Details

Cargo (January 2, 2024, 7:06 a.m.)

Pigment print

20 x 24 inches

Edition of 20

Signed and numbered by the artist

Richard Misrach is one of the most influential color photographers of his generation. His work is held in the collections of over fifty major institutions, including the Museum of Modern Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, and Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. He is the recipient of numerous awards, including a Guggenheim Fellowship. His previous Aperture titles include Destroy This Memory (2010), Golden Gate (2012), Petrochemical America (with Kate Orff, 2012), The Mysterious Opacity of Other Beings (2015), and Border Cantos (with Guillermo Galindo, 2016).

With the water flowing in from the heights and out through the gate, with the swelling and shrinking of the tides that mean the water’s height fluctuates dramatically twice a day, with the waves and the currents, what we call the bay is an oscillation, a nonstop process, beating like a heart and morphing like a jellyfish. A lot of its liminal edges, the former wetlands and old shoreline, have been lost to landfill, beginning with the filling in of the cove that was once downtown San Francisco’s waterline. A little monument on the pavement marks where the old shoreline was, several blocks inland from the current one, but sea level rise, driven by climate change, will take back much of what we have taken from the bay. Turning liquid into solid places began during the Gold Rush, when “water lots”—parts of the bay abutting San Francisco’s downtown—were sold off to be infilled and developed.

Huge amounts of soil and gravel from hydraulic mining (turning powerful jets of water onto the slopes of the Sierra Nevada to get at the gold) washed into the bay before the practice was banned, further diminishing its size. By one estimate, one and a half billion cubic yards of sediment were deposited thanks to this practice, along with tons of mercury, widely used in that era to refine gold, meaning that whatever profit was extracted incurred an ecological debt we are still paying. Signs around the bay in English, Spanish, Tagalog, and Chinese have long cautioned anglers about mercury poisoning if they eat their catch, but miners from the nineteenth century are still poisoning children born in the twenty-first. The same could be said of the fossil fuels moved in such alarming abundance in and out of the Bay, to and from the refineries in Richmond and the Carquinez Straits: the profit will burn up as fast as the gasoline, but the consequences will be with us for millennia.

Richard Misrach, Cargo (January 17, 2022, 5:33 p.m.)

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }In the postwar era, many plans were made to fill in more or most of the bay, with the logic that liquid spaces are useless and should be turned into solid land for development. Sylvia McLaughlin, a wealthy Berkeley resident, helped found Save the Bay in 1961 to push back at these land grabs, and part of the East Bay shoreline that was preserved now bears her name. In her oral history, she remembers seeing dump trucks going down to the shore to deposit their loads. She remembers the stench of raw sewage, the shoreline heaped with discarded junk. The bay was imagined then as a sewer to dump things into, as a void to be filled. That it was an ecosystem, a beautiful and valuable part of nature, at the heart of all this human development was largely ignored in that era. Now it is seen more clearly as a wilderness as well as an industrialized space and is more widely protected. Along some stretches wetland restoration has taken place. But the ships still come.

There are so many kinds of invisibility here. The opacity of the water in all but the shallowest, calmest stretches means the vast underwater world is easy to ignore, though seaweed and shellfish are visible at low tide and dead creatures wash ashore along with debris. After storms, twigs, branches, and sometimes trees ride the waters. After a major storm, soil washes into the creeks, rivers, and bay itself, forming a tongue of brown water that extends far beyond the Golden Gate. The bay is treacherous in many ways—much of it is too shallow for large vessels, obstacles stud it, the force of tides and storms can be colossal. Pilot boats and tug boats are required to guide oceangoing vessels into the bay. Among the other things underwater around the mouth of the Golden Gate are shipwrecks from the days before GPS, radar, and other navigational technology. The foghorns are relics of that era, when sound served ships whose crew could no longer see any distance.

Richard Misrach, Cargo (January 16, 2024, 7:03 a.m.)

Richard Misrach, Cargo (January 16, 2024, 7:03 a.m.)  Richard Misrach, Cargo (November 12, 2023, 7:20 a.m.)

Richard Misrach, Cargo (November 12, 2023, 7:20 a.m.) Wildlife still abounds: fish—sometimes in astonishing if fading abundance as herring runs and salmon migrations—seals and sea lions, crustaceans and shellfish, shorebirds and seabirds. But even the whales that occasionally swim under the Golden Gate Bridge are dwarfed by the ships. The ships are troublesome reminders of industrial civilization at its most aggressive, behemoths that cross the Pacific to feed American appetites for fuel and manufactured goods. The goods are now mostly unloaded in the Port of Oakland. The oil tankers go to the Port of Richmond, where oil from California, Alaska, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Colombia, and Ecuador is piped to the Chevron Richmond Refinery and other fossil fuel companies in the vicinity. Half of the oil extracted from the Amazon goes to California, where it is turned into jet fuel, diesel for delivery vehicles, and gasoline. The ghosts of the rainforest are part of what haunts the Bay.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

The ships are protagonists in the drama of the changing climate, though that too is among the things that can be understood but not seen directly. Four tenths of the global shipping industry’s activity is moving fossil fuel around, because the stuff is so unevenly distributed across the earth and the appetite for it so voracious. When we transition away from fossil fuel, the comparatively even distribution of sun and wind across the globe means that much of this traffic will become obsolete. In that context, you can look at these ships as a threat and trouble as part of their cargo. And you can see sunlight as another protagonist visible in all these pictures, see wind discernable in the rough surface of the waters.

Time itself is invisible when it operates on scales longer than our attention spans, when we fall prey to thinking that what looks stable on the scale of a day or a decade is stable, when we fail to gather the sources that let us know that stability is just a snapshot decontextualizing instability. Understanding this place requires an imagination that reaches beyond the visible to scales of time and space the eyes cannot take in but the imagination can. A photograph is a moment, a fraction of a second to a few seconds, of time; but the Bay in its current size and shape is also a finite era in time that is coming to an end. This knowledge is cargo we all carry.

Richard Misrach, Cargo (December 19, 2023, 7:50 a.m.)

Richard Misrach, Cargo (December 19, 2023, 7:50 a.m.)  Richard Misrach, Cargo (February 20, 2024, 7:00 a.m.)

Richard Misrach, Cargo (February 20, 2024, 7:00 a.m.)All photographs © Richard Misrach

This essay originally appeared in Richard Misrach: Cargo (Aperture, 2025).

July 3, 2025

Silvia Rosi Reimagines the Family Album

Silvia Rosi picked up photography in her teenage years, documenting friends and family in the northern Italian region of Reggio Emilia, to which her parents had immigrated from Togo in the late 1980s. Rosi’s own move from Italy to England, to attend the photography program at the London College of Communication from 2013 to 2016, instigated a period of introspection about what it means to leave home and put down roots elsewhere. The feeling of being between cultures is at the heart of her practice.

“I was going back to my memories of Italy and looking back at images in family albums that would reconnect me with a sense of my identity,” she told me recently. Far from her familial networks, Rosi, who is still based in London, turned the lens on herself. “You use what you have at hand,” she noted with a wry smile.

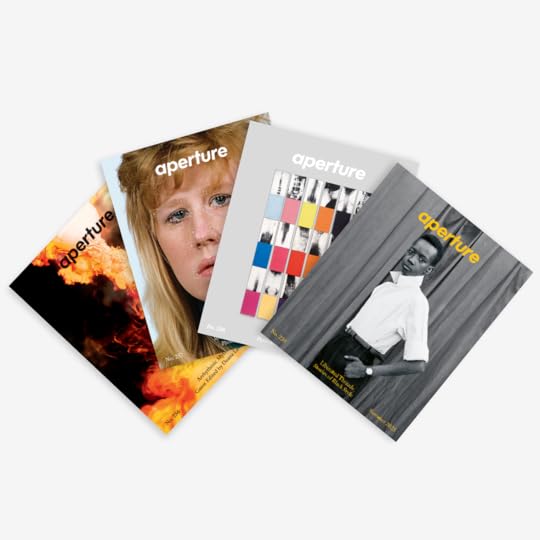

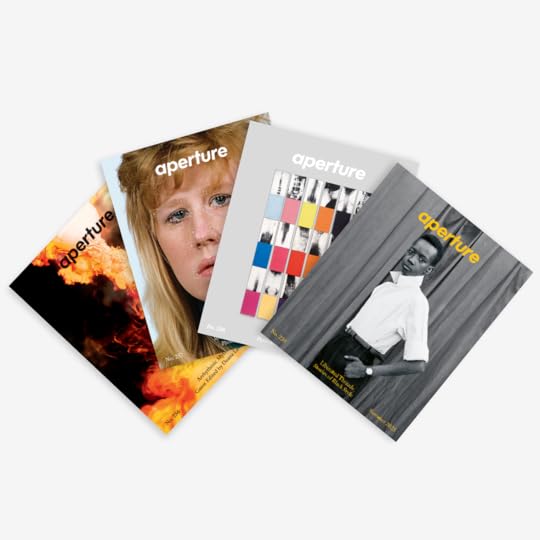

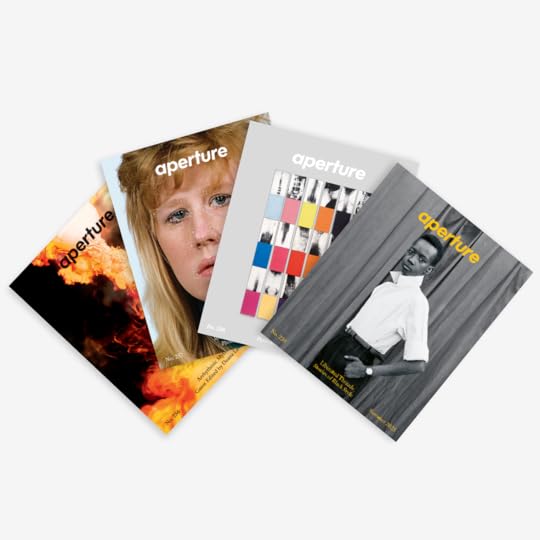

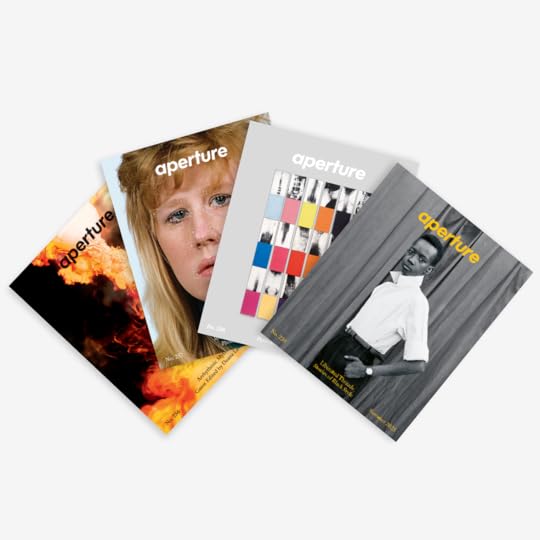

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

From the series Disintegrata (Disintegrated, 2024), the image Disintegrata con Foto di Famiglia (Disintegrated with Family Photo) shows Rosi standing between two wooden cabinets with framed photographs placed on them. The pictures—a woman in a wedding dress, family snapshots, a black-and-white studio portrait—suggest the ways vernacular photography has been used in the African diaspora as a means of documenting lives in transit. Her work also speaks to visual and oral modes of memory and transmission in family lineages. In Self-Portrait as My Father (2019), Rosi sits on a chair against a blue backdrop, balancing books on her head, wearing glasses and a formal shirt, tie, and trousers, like a clerk about to head to the office. On the ground next to her feet are tomatoes stacked in small pyramids. Here, Rosi steps into the metaphorical shoes of her father, whom she never met, filling in the gaps between his physical absence and the stories passed down about him by her mother. Though he arrived in Italy an educated man, Rosi said, “I know that when my father lived in Italy, he worked as a tomato picker. He ended up being part of the exploitation of migrants. This happened in the late 1980s, but it is also something that is still happening now.”

Silvia Rosi, Disintegrata con Foto di Famiglia (Disintegrated with family photo), 2024

Silvia Rosi, Disintegrata con Foto di Famiglia (Disintegrated with family photo), 2024  Silvia Rosi, Self-Portrait as My Mother in School Uniform, 2019

Silvia Rosi, Self-Portrait as My Mother in School Uniform, 2019 In Self-Portrait as My Mother in School Uniform (2019), Rosi carries toothpicks, reminiscences of the items her mother sold at roadsides and markets to passersby as a young trader in Togo, as her mother’s mother had before her. Styled in clothing similar to her mother’s school uniform, with books placed on her lap and her gaze fixed firmly on the viewer, Rosi inhabits the vulnerable yet entrepreneurial spirit of her mother as a young woman before motherhood. In another image, Self-Portrait as My Mother (2019), Rosi carries a radio on her head—a reference to highlife and Afro jazz but also a symbol of a deeply personal memory of her mother’s.

“The radio represents a moment when my mother was working for an Italian family. She overheard on the radio that a law would be passed that would legalize migrants present in Italian territory at that time, which enabled my parents to stay and live in Italy,” Rosi explained. Style and clothing, much of it sourced from secondhand shops, are key to Rosi’s work. In her inhabitations, the glasses or suit her father wore transcend their status as middle-class signifiers to become objects imbued with private meanings. Shutter release cables snake across the floor and lead to the hand of the artist, as if to show she is in complete control.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Rosi’s recent work is openly indebted to West African studio photographers such as Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé, who helped visualize a kind of post-independence modernity. In one photograph, Disintegrata di Profilo (Disintegrated Profile, 2024), the artist, clad in a preppy blazer and khakis, poses with an Agfa-Gevaert book: an apparent reference to the legendary photographer James Barnor, who moved from London back to his native Ghana in 1970 to set up the first Agfa color-processing laboratory in the country. Rosi holds the book up to obscure her face, as if to resist the camera’s capacity to fix identity in place.

In bringing together the performative elements of self-portraiture and the commitment to preservation found in family albums, Rosi stages a different kind of performance, similar to the ways in which Samuel Fosso used his own body in the 2008 series African Spirits to perform and embody famous pan-African figures, including Patrice Lumumba and Kwame Nkrumah. Rather than reaching toward historical personages, Rosi emulates those who aren’t written about, the lives of immigrants trying to establish themselves in a new country in the face of economic precarity and cultural dislocation. Her images beautifully highlight tender, painful feelings of misrecognition and alienation, and the difficulties of starting anew.

Silvia Rosi, Neither Could Exist Alone, 2021

Silvia Rosi, Neither Could Exist Alone, 2021  Silvia Rosi, Sposa Italiana Disintegrata (Disintegrated Italian bride), 2024

Silvia Rosi, Sposa Italiana Disintegrata (Disintegrated Italian bride), 2024  Silvia Rosi, Self-Portrait as My Mother, 2019

Silvia Rosi, Self-Portrait as My Mother, 2019  Silvia Rosi, Disintegrata di Profilo (Disintegrated profile), 2024

Silvia Rosi, Disintegrata di Profilo (Disintegrated profile), 2024  Silvia Rosi, ABC VLISCO 14/0017, 2022

Silvia Rosi, ABC VLISCO 14/0017, 2022All photographs courtesy Autograph APB, Collezione Maramotti, MAXXI and Bvlgari, and Jerwood Arts/ Photobooks

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 259, “Liberated Threads.”

June 26, 2025

Rosalind Fox Solomon’s New York City

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 242, “New York,” Spring 2021.

Rosalind Fox Solomon found her calling, photography, in her late thirties. Fox Solomon’s teacher, Lisette Model, encouraged her daring and self-confidence. With a camera, Fox Solomon could view life from her own angle, her distinctive vision.

Fox Solomon has traveled widely, photographing in Peru, the American South, Israel, and the West Bank, to name a few places. But, she tells me, “I did not find myself shooting in New York City in a different way. I made portraits of people and imagined their concerns. As I shoot, there is always inner tension, a trance-like state that contrasts with a nice-girl smile. That’s how I work everywhere.”

Rosalind Fox Solomon, Inside the Gate, Staten Island Ferry, 1986

Rosalind Fox Solomon, Inside the Gate, Staten Island Ferry, 1986  Rosalind Fox Solomon, Seeing Beyond, Staten Island Ferry, 1986

Rosalind Fox Solomon, Seeing Beyond, Staten Island Ferry, 1986 Over the last five decades, Fox Solomon has pictured New York through its events, inhabitants, and objects. Her commitment to social justice animates her choice of subjects, and her pictures often show those who are troubled, suffering, or in crisis.

A young man with AIDS looks solemnly at the camera. He appears resolute, an implacable expression on his face. “It was wrenching shooting people with AIDS,” Fox Solomon tells me. “I met and photographed them, and some died soon after.” Her exhibition Portraits in the Time of AIDS at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery in 1988, in the midst of the epidemic, insisted on the public’s awareness of the suffering of so-called ordinary people.

People in wheelchairs on the Staten Island Ferry, people standing, all with their backs to the viewer, are looking at the water or the skyline, or inwardly. What they are thinking about, how they feel, is unknowable; but imaginations are spurred to wonder.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

After 9/11, handmade posters of the missing showed up on walls all over Lower Manhattan. “From a poster, I learned about the death of a friend, the artist Michael Richards,” Fox Solomon says. The attack on the Twin Towers was political, but the effects were instantly personal, each poster a death. Fox Solomon’s photograph of the desperate pleas of families and friends, and not the city’s physical devastation, emphasized her concern with wrecked lives, not buildings.

A Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade balloon, lying on a street, is a template for interpretation. This poetic image could register a tragic reality: Americans celebrate a family holiday, which elides North America’s first families, almost entirely wiped out by the US government. Or, it might represent the melancholy that comes after the fun ends, or how temporary pleasure is. There are many ways to see it.

Rosalind Fox Solomon, Has anyone seen artist Michael Richards? After 9/11, 2001

Rosalind Fox Solomon, Has anyone seen artist Michael Richards? After 9/11, 2001  Rosalind Fox Solomon, Stuck, before the Macy’s Parade, 1977

Rosalind Fox Solomon, Stuck, before the Macy’s Parade, 1977 People can see so differently from each other, so idiosyncratically. Eyewitnesses have different eyes. There may sometimes be a consensus about a photograph—this is a good picture—but judgments about its meanings vary. Photographs don’t reveal themselves, don’t investigate, don’t tell us how to see them. Reactions to any picture depend on a viewer’s subjectivity, psychology, sympathies, sensibility, and more. An understanding of that dissonance inheres in Fox Solomon’s imagery. These photographs are gentle, also tough and unsentimental, sometimes tender yet unsettling.

Fox Solomon’s New York photographs look at the past and augment public and private histories. They are impressions of what compelled her, or disturbed her, about how people lived and what shaped their lives. Her photographs intend an intimacy, a connection and closeness to this place.

Looking at this work now, Fox Solomon says, “I am struck by the fact that my themes and interests are consistent—people, their differences and similarities; relationships; and issues such as race relations, politics, women’s roles, illness.”

Rosalind Fox Solomon, I Love NY, Staten Island Ferry, 1984

Rosalind Fox Solomon, I Love NY, Staten Island Ferry, 1984  Rosalind Fox Solomon, The Artist’s Wife, Meta Cohen Bolotowsky, 1978

Rosalind Fox Solomon, The Artist’s Wife, Meta Cohen Bolotowsky, 1978  Rosalind Fox Solomon, Jeff Engleken, Nuclear War?! There Goes my Career!, 1987

Rosalind Fox Solomon, Jeff Engleken, Nuclear War?! There Goes my Career!, 1987  Rosalind Fox Solomon, What Lies Ahead?, 1987

Rosalind Fox Solomon, What Lies Ahead?, 1987  Rosalind Fox Solomon, Singing Revival, Washington Square Park, 1986

Rosalind Fox Solomon, Singing Revival, Washington Square Park, 1986  Rosalind Fox Solomon, High School Chums, 1987

Rosalind Fox Solomon, High School Chums, 1987  Rosalind Fox Solomon, Cashier, Cozy Soup and Burger, 1984

Rosalind Fox Solomon, Cashier, Cozy Soup and Burger, 1984All photographs courtesy the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 242, “New York,” Spring 2021.

Elle Pérez Brings Everyone Along

On an early spring afternoon in Washington Heights, sitting on the steps by the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, I listened to a mockingbird sing to me from a nearby tulip poplar. The song of the mockingbird mimicked the community of birds that lived in the area: sparrow, thrush, wren, flicker. How do we remember our lives? In song, in name, in pictures, in words? How do we carry histories with us, like the mockingbird?

I thought of the words of the photographer Elle Pérez as I sat in the shade that hot afternoon: Dogs in the morning. Clothes on the line. Bronco in the Crowd. And STILL!!! The words came from poems adhered to the walls throughout their recent solo show, The World Is Always Again Beginning, History with the Present. The exhibition gathers twenty years of photographs, words, collages, and video—naming, seeing, finding and celebrating their friends, family, and community, frame by frame. From Puerto Rico to Rome, from Monet’s garden in Giverny to sweaty punk shows at the First Lutheran Church in the Bronx, Elle sings their song, bringing everyone along with them. From our respective homes in New York and Philadelphia, Elle and I discussed the ways they see the world.

Elle Pérez, Kiss, from the series Somewhere We Belong, 2009/2025

Elle Pérez, Kiss, from the series Somewhere We Belong, 2009/2025Alex Da Corte: There’s a performative aspect to your work, and then there’s a documentary or diaristic aspect—you’re making the work and understanding the world, and understanding culture. It’s like being on stage and offstage at the same time. Could you speak a about that space, how you do both or do everything?

Elle Pérez: I feel really lucky for having come to art, and being an artist, not through an institution, but through a group of people I was in direct conversation with.

I must have been twelve or thirteen when I went to a Bronx Underground (BXUG) punk show at the First Lutheran Church (FLC) for the first time. Then I got a camera, joined the collective, and immediately started making photographs of my friends.

The pictures I make have always had the option of being more than just art, and taking on a utility. Back then, I would share them immediately on a hosted website I linked to Myspace. A picture could then be used on someone’s profile page, it could be an advertisement for a band, it could be someone’s memory of a night. Later, as time passed, people started to pass away and then the photographs became a kind of dynamic memorial of someone. I could go back and find two hundred photographs of someone who had died; here they are on the back steps, here they are making a funny face, here they are with their girlfriend, and here they are at their own funeral. What I’ve been struck by in putting this show together is the profound amount of trust that endures between myself and everyone else from those days.

Recently, I got back in touch with the younger brother of my friend whose funeral is depicted in that front room at Arts and Letters. I reached out to ask for permission to put the photograph in the show. The picture is from 2009, so I was like, “I don’t want to upset you, I don’t want to upset your family. But I do feel like this is one of the most important pictures I have ever made, and it would be an honor to put it up.” He responded almost instantly like, “Do it. You never have to ask.” That’s such a profound gift for an artist, I think, that level of trust. Because that picture is not separate from real life, and it’s not something that someone feels is separate from the truth of what happened. You know what I mean?

Elle Pérez, Boog’s Tattoo, from the series Somewhere We Belong, 2009/2025

Elle Pérez, Boog’s Tattoo, from the series Somewhere We Belong, 2009/2025 Elle Pérez, In Memory of Critic, Rest in Peace, John, from the series Somewhere We Belong, 2009/2025

Elle Pérez, In Memory of Critic, Rest in Peace, John, from the series Somewhere We Belong, 2009/2025Da Corte: I do know what you mean. You are deeply invested in a community of people and your friends. You’re a righteous friend, and you make room for so much. People feel that. So of course, it doesn’t surprise me that that trust is apparent in the pictures you make and in the relationships you make. I anticipated that from seeing your work before I ever met you.

It’s funny, I was thinking about the Italian word for camera being room, and I was like, Oh, wow, Elle makes rooms for people, or the work is a room, it’s a basement of FLC, it’s a garden, it’s Pedro’s backyard, it’s the wrestling ring. A room is a thing that holds people, it holds things together. It can make space for people, there’s room to have discourse, there’s a kind of seat at the table to discuss or argue or be different and be okay with these differences. And I find that that is so much what I see in your work, it’s what I think makes it quite humane.

Pérez: I’m glad to hear that for so many different reasons. Some of them are personal and some of them are formal. I’m like, Oh, phew, the work is working.

Elle Pérez, Flag, from the series Somewhere We Belong, 2009/2025

Elle Pérez, Flag, from the series Somewhere We Belong, 2009/2025Da Corte: You’re clearly at work. You’re always engaged in thinking and absorbing and being present and actively looking. And that takes quite a bit of energy. Because I find that people sort of are lazier viewers of things, maybe less impressed or a little bit numb, this brain rot in a way of just casually being in the world. And yet it seems as though micro light shows almost invisible moments that are quite special.

I keep thinking back to this photograph of your grandfather’s garden and that beautiful dog, and the boat—the Mona Lisa—and thinking, Here is such a rich space of so many things. It’s a portrait of your family, it’s a portrait of nature, it’s a portrait of art history—and how you saw it and frame it—and it’s all there for you.

Pérez: That series came out of nowhere, in a way. I had been making pictures in Puerto Rico around my grandfather’s impending death that I wasn’t putting pressure on. Then, by chance, I was invited to Giverny, which I had never been to before. That is where I encountered Monet’s garden, and became interested in Monet as a person.

One of the ideas that surfaced while I was working on this show was the idea of chance. The chance that one gets to be an artist, and the chance that one’s art is then understood, and the chance that someone else—a viewer—feels the feelings in the work. While contemplating Monet’s life and studio in Giverny, I began thinking about the dehumanization and myths that result from fame. Because it’s not being an artist that dehumanizes you, it’s something else. It’s like, to become myth you have to in some ways become less human, and what causes that?

Elle Pérez, Untitled (car body), from the series La Despedida, 2025

Elle Pérez, Untitled (car body), from the series La Despedida, 2025Da Corte: I think it’s capitalism.

Pérez: Yes, for sure. Myth feeds the money machine. For instance, Monet’s garden. There were tourists pouring in by the busload to see it. I paid eleven euros to go look with everyone else. It felt like all of Europe was there at the same time. Everyone was responding to the garden with their cameras, even if only an iPhone. No one was making the exact same picture. So wild. And yet it was so interesting to me. I was very impressed by this paradigm for seeing and making that he’d set up. The prompt was simple: how could Monet see something new every day? It was so powerful even in its conserved state, as a museum. It was fundamentally different than something like the Frida Kahlo or Luis Barragan house where everyone takes the same photograph.

At that moment, I was also searching for how I could continue to make art. How do you continue to innovate? How do you continue to work against and with yourself, to push yourself, and respond to new ideas while contending with the things that you have to do—work, laundry, kids—in order to make a life?

It was fun to play with answering that question in the accompanying essay for the exhibition: I wrote through the figure of Monet. I wanted to break him out of his myth and think about him like he was a friend. Part of that was referring to him in the essay not as Monet, or even Claude, but as Oscar, because I read that Oscar was what his family called him. I have a cousin named Oscar, who I love. So, it was kind of fun to make this swap, almost as if my cousin Oscar was playing Monet in the movie in my mind. It helped me orient a more personal history, like I was describing a friend. Now, being in my mid-thirties, I’ve watched my friends go through various cycles of the art world and their various relationships to it. I could find compassion for someone who had really been evacuated of humanity because of that kind of consumption capitalism can provoke, or even demand.

Elle Pérez, Untitled (cleaning the pond), from the series La Despedida, 2025

Elle Pérez, Untitled (cleaning the pond), from the series La Despedida, 2025Da Corte: And that’s sort of where you have to find and bolster this magic in your own life outside of if you’re Claude or an Oscar. It relocates or resituates this idea of “artists,” in quotes or a capital A. You’re a person in the world and you would be doing this or something else regardless of who was seeing it. That seems so obvious in the photographs in those first rooms of Arts and Letters. That you are just looking, and that the kind of picture you’re sharing is not reliant on necessarily the particularities of who we’re looking at, there’s something there. It makes me wonder, how does that framing happen or that selection happen for you? Is it about a balanced space of finding the formal and finding the—not sentimental, as you’ve refuted that, but the sparkle or something? I feel like there’s a little game there, or maybe that’s the itch you have to scratch.

Pérez: I started making art because I wanted people to see it, not because I wanted to do it only for myself. It was always about relationships. The spark of wanting to photograph was also the spark of wanting to look. It was how I wanted to look at other people as much as it was about how other people wanted to see through my eyes. And there were a couple other people who then started photographing as well, it was like, “Cool! what are you seeing!?” Style became something to contend with. My pictures became less of “the news” and became more authored. I started responding to my pictures, challenging myself to heighten the feeling of emotion, to make more evocative portraits, and photograph who I wanted to look at.

I kept photographing even when I went to college in Baltimore. I would come back monthly to the Bronx, shoot, and go right back to Baltimore. While I was in Maryland, I was totally doing the art school thing and experimenting wildly. I took that influence home with me. I would go back to the Bronx Underground and experiment with film, or experiment with a new style. I could always try something new there, because I felt no anxiety about losing access to the space, or not having people’s trust. I felt it not as a subject to make art about, but as my life.

There’s this little arc in my archive, I think it’s around 2009 or 2010. I must’ve gotten really into the Düsseldorf School of Photography, because everyone is in this side profile, high flash, like all German indexical. Zoomed in, tight crop. It’s somewhere in between Dijkstra and Tillmans.

Elle Pérez, Untitled (wet and tired flowers), from the series La Despedida, 2025

Elle Pérez, Untitled (wet and tired flowers), from the series La Despedida, 2025 Elle Pérez, Untitled (king), from the series La Despedida, 2009/2025

Elle Pérez, Untitled (king), from the series La Despedida, 2009/2025Da Corte: All those folks.

Pérez: Yeah, all those folks. It’s a very Becher-esque punk index of my friends. Like punk water towers or something. Finally somebody was like, “You need to back up!” I was like, “You’re right, you’re right.” [laughs]

That last year of BXUG coincided with my last year of graduate school. I felt like all of my education ended at the same moment. FLC ended in February 2015, and I graduated from Yale that May. It felt like I lost access to both of these places for experimentation at the same time. While I was in Puerto Rico last year, I realized my grandfather’s garden was another one of my artistic laboratories.

I was going to Puerto Rico because my grandfather was dying; my life was occurring and I was responding to it. I started photographing in his garden around 2012. And as I grew up, like the others, this laboratory was coming to a natural conclusion. A very human conclusion, in that my grandfather was passing away. I knew that the space would change. I was like, Okay, I know this change is coming and I’m going to respond to it. I don’t know exactly when it’s going to happen, but I know it’s going to happen. For about a year, I was making photographs around his home and garden, unpressured and unassigned, made in premeditated grief. It was when I went to Monet’s garden that the threads came together.

This show is so much about audience as a photographic subject. For me, part of the pleasure of making the work is the audience.

The scholar Horace Ballard had been the one to suggest that I photograph Monet’s garden. I was like, “You know what? I think you’re right about that.” I had no idea what I’d do. I looked at what others had done a little bit, but I didn’t want to look too much, and I figured I would simply respond to the site. I thought like, okay, I’m going to apply all of the things that I learned photographing my grandfather’s backyard in Puerto Rico to this new place.

One of those revelations was about responding to what was there. Observing, accepting, and taking on the pictorial challenges presented, even if it was something like undesirable light at high noon. I realized all the flexibility that “undesirable” light gave me in terms of how much I could work with the tools of the camera to create that space or to compress it. I was wrangling pictures, not predetermining them. That made anything a photograph. Every single thing I looked at was like, “I’m a picture! Over here! I’m a picture too!”

I was actually quite overwhelmed. My grandmother and my aunt were sitting on the porch, watching me. They were smoking their cigarettes and they were laughing like, “What are you doing?” Because I’m photographing the dog’s bowl with the garden hose and the random trash that’s in the yard, and I was like, “It is all so beautiful!” And they’re like, “Okay, you have lost your damn mind.” [laughs]

Da Corte: But it must be wonderful—

Pérez: And yeah, they just let me do my thing.

Elle Pérez, Pedro in his garden, 2025

Elle Pérez, Pedro in his garden, 2025Da Corte: Well, it must be wonderful to then find that sort of illumination that might be in a water lily, in a dog’s bowl. And to fold yourself back into these histories that maybe seem so far away, but they’re also your life. It makes me think of your last show at 47 Canal and the work you were doing in Rome when we were there, and now this latest collage work and how that then almost becomes its own sort of analysis or diagram of a book in open form—of your life, or a life that can be read and understood and is quite active. It’s a real living thing, whatever that may be. It doesn’t necessarily have to be beholden to you, but it is definitely an active way of looking. And I wonder if you could speak a little bit to how you arrived at this sort of open plan, this kind of brilliant mind schema.

Pérez: I’ve always made those collages for myself in the studio. A lot of people do, I don’t really think that they’re a unique structure to me. They started to feel like they were important to show alongside the pictures. They serve an interpretive purpose for people that can extend beyond the wall label or the text and provide a different mode of interpretation for the work, one that is open-ended. The collages allow people to re-experience putting the show together. When you look at the collage you aren’t looking at something that has formed a conclusion. You are looking at the process.

And you might have a different conclusion than I did! And in that, people can maybe see how I put things together. It creates a point of contrast between what I have selected as the work on the wall, and what other photographs also exist. That creates an opportunity for people to get to know both the work and me better. I love seeing people looking at it. This one I kind of designed to be playful, this one has—

Installation view of Elle Pérez, The World Is Always Again Beginning, History with the Present, 2025

Installation view of Elle Pérez, The World Is Always Again Beginning, History with the Present, 2025Da Corte: It has a small disco ball in it.

Pérez: Which is very appropriate, I feel like, for anyone who knows me personally.

You referred to this collage like a form of Facebook, and that resonates with me. Viewers have a very parasocial relationship to photography now. The subject, once presumed silent, is now expected to speak on their experience regularly. And people will often feel they are entitled to a response. It has been this way now for a while. I mean, even at the 2019 Whitney Biennial opening, someone sought out Aurora Mattia after seeing her in the photograph Mae (Three days after) (2019), interrupted her conversation, and without even introducing themselves was like, “What happened to you?”

At first, that assumed right to access was a shock to me. After a while I started to ask, how do I subvert this? Knowing that people had a tendency to see someone, take a picture of them, and send it to that person, I devised this collage almost as a postcard machine that generates notes for my friends from people who they might otherwise not necessarily hear from. So, it became a little game of love, of being this person that sent you a picture of you as a way to be like, “I see you! I’m thinking about you.” It is also from me, but it’s a different type of reaching for someone than what happens on Instagram. It is using the work to create intimate experiences.

In my studio practice, the collages help me think new ideas. There it’s a completely fluid possibility. Parts go up and go down, photographs move around, more things come in, articles are Xeroxed, thing are different sizes. Seeing what works, what did I not expect, all helps me see how can I get a little further along in my thinking. How can my pictures work in a way that I didn’t see before? And through that, I can understand my work better, and see where I can make them more complex, and make the pictures deeper in both form and content.

Da Corte: You give them new life.

Pérez: Yes.

Installation view of Elle Pérez: The World Is Always Again Beginning, American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, 2025. Photograph by Charles Benton

Installation view of Elle Pérez: The World Is Always Again Beginning, American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, 2025. Photograph by Charles Benton Installation view of Elle Pérez: The World Is Always Again Beginning, American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, 2025. Photograph by Charles Benton

Installation view of Elle Pérez: The World Is Always Again Beginning, American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, 2025. Photograph by Charles BentonDa Corte: Yes, you give them new life. You extend the frame, like we were talking about earlier, the space in the photograph is the stage. And then there’s this outside kind of bubbling, living, strange, and unpredictable thing that is unfixed. And this method seems to be able to bridge that gap, your generosity to give more and extend the thing that you’re seeing, and the photograph then is found in these other spaces. It feels more like the way we understand images now, too, and pictures, because they’re active and they’re talking. And there’s all of this kind of effervescence there that wasn’t before, in an open paper picture of the past.