Aperture's Blog, page 209

October 26, 2012

Aperture – Celebrating Sixty Years – Recap

Mary Ellen Mark, Donna Ferrato, Melissa Harris, Sylvia Plachy, Elliot Erwitt, Eugene Richards, Stephen Shore, Joel Meyerowitz, Bruce Davidson. Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Cathy Kaplan, Wendy Goldstein, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

W.M. Hunt, Jennifer Blessing, Howard Greenberg, Kathy Ryan, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Elizabeth Kabler, Joanne de Asis, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Mary Ellen Mark, Larry Fink, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Joan Parker, Kathy McCarver Root, Gail Albert Halaban, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Yancey Richardson, Cory Jacobs, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

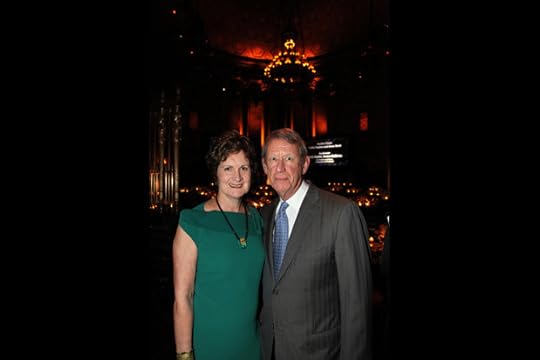

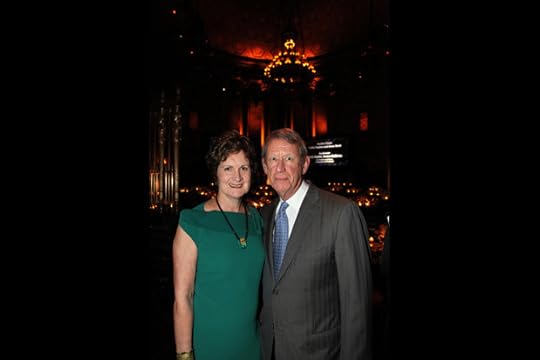

Celso Gonzalez-Falla, Sondra Gilman, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Kayla Lindquist, Elliot Erwitt, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Joey Arias, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Casey Weyand, Lauren Weyand, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Chris Boot, Melissa Harris, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Rachel Peart, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Gemma Sieff, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Susan Gutfreund, John Gutfreund, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Severn Taylor, Michael Hoeh, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Jessica Nagle, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Joan Parker, Peter Wolf, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

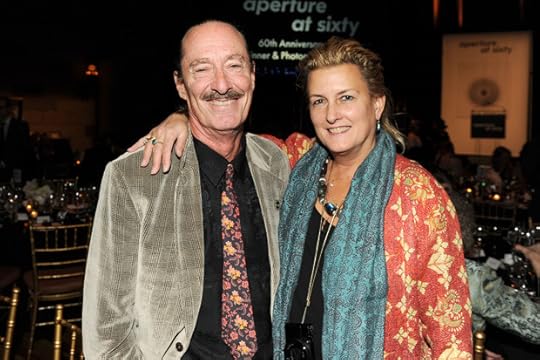

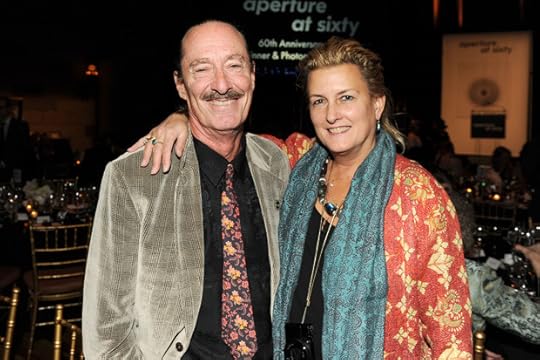

Robert Glenn Ketchum, Felicia Murray, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Lesley Martin, Joel Meyerowitz, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

More than 350 guests—including photographers and writers, photography collectors and dealers, and leading philanthropists—gathered for a glittering celebration at Gotham Hall on Tuesday, October 23, to mark the sixtieth anniversary of Aperture.

Thanks to all who attended, and to everyone who has supported Aperture over the past sixty years. Here’s to sixty more!

Recap: Celebrating Sixty Years

Mary Ellen Mark, Donna Ferrato, Melissa Harris, Sylvia Plachy, Elliot Erwitt, Eugene Richards, Stephen Shore, Joel Meyerowitz, Bruce Davidson. Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Cathy Kaplan, Wendy Goldstein, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

W.M. Hunt, Jennifer Blessing, Howard Greenberg, Kathy Ryan, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Elizabeth Kabler, Joanne de Asis, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Mary Ellen Mark, Larry Fink, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Joan Parker, Kathy McCarver Root, Gail Albert Halaban, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Yancey Richardson, Cory Jacobs, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Celso Gonzalez-Falla, Sondra Gilman, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Kayla Lindquist, Elliot Erwitt, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Joey Arias, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Casey Weyand, Lauren Weyand, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Chris Boot, Melissa Harris, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Rachel Peart, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Gemma Sieff, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Susan Gutfreund, John Gutfreund, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Severn Taylor, Michael Hoeh, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Jessica Nagle, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Joan Parker, Peter Wolf, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Robert Glenn Ketchum, Felicia Murray, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

Lesley Martin, Joel Meyerowitz, Photo: Patrick McMullan/PatrickMcMullan.com

More than 350 guests—including photographers and writers, photography collectors and dealers, and leading philanthropists—gathered for a glittering celebration at Gotham Hall on Tuesday, October 23, to mark the sixtieth anniversary of Aperture.

Thanks to all who attended, and to everyone who has supported Aperture over the past sixty years. Here’s to sixty more!

October 25, 2012

Brian Bress – Interventions

By Carmen Winant

Brian Bress, an artist who comfortably straddles the lines between painting, sculpture, video, and photography, has just closed his first solo museum exhibition in the United States at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. The show, titled Interventions, was comprised of five video portraits dispersed throughout the museum galleries. Here, Bress speaks with Carmen Winant about his evolution as a maker, the difference between humor and absurdity, and the pervasive influence of Los Angeles.

Carmen Winant: I think your videos are so curious, vexing, funny, and strange. We will get to all of those qualities, but before we do, I am curious about your art-making background. Did you start right away in video, or work your way there from other mediums such as photography or painting? Your current video portraits lead me to believe the latter.

Brian Bress: There has been a lot of back and forth between various mediums. I went to RISD as an undergradate thinking that I would be an illustrator. I don’t know what compelled me, but once there, I ended up majoring in film, video, and animation. I could already draw pretty well, and wanted to learn something totally new. That was before the popularity of non-linear editing, or computer editing, and I learned a lot of non-traditional filmmaking techniques in the program.

Right in the middle of that process, I decided to go to Rome through the RISD Honors program, and focus exclusively on painting. I did that for a year, and then came back to Providence and jumped right back into my animation projects. That back-and-forth between those mediums is how it’s been for most of my life. Right after I completed my undergrad degree, I started going back to traditional painting. When I applied to UCLA’s graduate program a few years later, I did so without any video or animation work. It was all painting and drawing. Pretty soon after arriving there, I started working on time-based projects.

CW: In retrospect, your interest and training in video/film and traditional painting—or your toggling between them—really seem to make sense in regard to your current practice.

BB: I like to think that the work that I am doing now holds the same concerns and interests for someone who is interested in painting as for someone interested in video.

CW: Your work has been frequently described as both absurd and humorous. That got me thinking about the difference between the two qualities, which are often conflated. Much more so than humor, absurdity is really about failure—failure to find real meaning or value in life. It’s entangled with nihilism in that sense. How would you define it?

BB: I definitely see them as distinct characteristics, totally separate from one another. Humor is for me about creating, and breaking, everyday patterns. There is a great Dick Van Dyke Show episode in which he has to go to a school and explain to a class what he does, which is writing comedy for television. He walks across the room, and trips and falls, and all the students laugh. He proceeds to explain to them why they found it funny: he was putting one foot after the other, which created the expectation that he was going to continue that pattern. But when he tripped it disrupted that expectation and it surprised them. That kind of wonderment is the pleasure that I get from humor and the way that it operates. As opposed to absurdity, which is more of a critique of reality and the ways in which it doesn’t add up. The absurd functions by critiquing what “makes sense” in the real world.

CW: Where does that interest figure in your own work?

BB: I don’t attempt to be funny or absurd in my work. That just wouldn’t be very smart or interesting. It would come off as hammy or overdone, or lacking real subtlety. My intention is not necessarily to ride between the two, though I can sometimes look back at work and observe that it behaves that way. Ultimately, absurdity and humor are the byproduct of ideas, rather than the ideas themselves.

CW: Your reference to the Dick Van Dyke Show is actually a nice segue; I’d like to talk a little about your relationship to the entertainment industry. You live in Los Angeles. I can’t help but wonder, as an artist making elaborate, vaguely narrative and character-based low-fi productions, how the industry town has affected your work.

BB: The more I live and make work in LA, from a logistical standpoint, the more I can’t imagine making work anywhere else. The technical resources here are incredible: equipment, cameras, props, experienced people. I just hired a great cinematographer named Michael Totten for a recent piece. He filmed the character with a high-speed, very sophisticated camera. So, I am aware that there are resources that only Los Angeles can provide.

CW: Does the industry affect you from a creative standpoint?

BB: To be honest, I am not always too conscious of how the entertainment industry rubs off on my studio practice. But it does, in funny ways. My girlfriend is a set decorator on Disney television shows. In the back of my mind, I know how it’s really done. I know what resources are available to create the aesthetic of the super-real—I am going to call it that as supposed to surreal. The aesthetics of those Disney shows is heightened and exaggerated. Sometimes I like that aesthetic and sometimes I don’t, but I am aware of it. But I deliberately try not to be too conscious of the ways that it affects my work.

CW: Do you work with your girlfriend collaboratively?

BB: No, not so much. She is more of a fixer. She knows where everything is. She knows all the prop houses. Which I don’t rent from—I make everything. But sometimes, if it’s a mechanical thing off-camera, she knows exactly where to get it. For instance, I recently needed a giant, rotating pedestal, and she told me exactly where to go in Burbank to find it. You can’t easily acquire that kind of knowledge on your own.

CW: Continuing that strand—the occasional challenge of working alone—I am wondering: are you in every video that you make?

BB: I appear in a lot of them, though not all of them. That is shifting. I used to be in all of them because I knew what I wanted, and it was easier to perform myself than direct someone else. Or sometimes I didn’t know what I wanted. In those cases, I just knew what I wanted the image to look like. The whole purpose in that sense was to create an environment that was inspiring enough, beautiful enough, interesting enough. I could try out unexpected things in front of the camera, edit later, and find the piece that way. So, it would have been impossible to direct someone else. What would I say? “Okay, improvise, because it’s so interesting to you to be here”? That’s not something I could ask of, or expect from, someone else. But, as I’ve worked with scripts and focused the experiments, I have been able to hand off that task to other people.

CW: When you were the only one performing, was someone else behind the camera?

BB: Before 2010, which is when I did my first scripted piece (with one prior exception), I would turn on the camera, run in front of the camera, and do my thing. Every clip ended with me walking back to press the red button.

CW: I’m interested in how our relationship to viewing (and curating) videos has shifted as the form becomes less marginal. I did an interview with last year with Ed Halter and Thomas Beard of Light Industry, and they made a really interesting point about how curators often show videos the same way they do two-dimensional work—without any sensitivity to the medium’s needs. They were trying to shift that paradigm by creating a “film program” during the 2012 Whitney Biennial, as opposed to, say, looping videos in the corner. Do you agree with that argument? What is the ideal way for your own work to be shown?

BB: More than anything, I think it depends on the piece. There are pieces that I’ve made in the past that have more of a narrative, cinematic bent to them. I would love for people to sit down in a dark room at the beginning and watch until the end, much like going to the movies. The works that I have been making recently, on flat panel monitors inside of colored frames, are much more about the entire object, not just about the image being displayed on the monitor. They are about the thing hanging on the wall, and sensing that there is space behind and around the object.

CW: You are referring to the work in the Santa Barbara Museum of Art show, correct? Can you speak a little more to it, and your interests in creating it?

BB: There are a few things that drove my curiosity. The first is the paring down of motion and gesture. There is an uncanny feeling that occurs when something that you didn’t expect to move in fact does. The other interest is what I just mentioned—playing with space and depth within an object on the wall.

CW : That show consists of five video portraits spread throughout several floors and across different galleries devoted to different artistic genres. It’s an unusual way to show work, particularly in a conventional museum space.

BB: That was [SBMA curator] Julie Joyce’s idea, and I loved it from the beginning. As I mentioned before, I am interested in playing with how people perceive the work, what their expectations are for a framed object on the wall, and the subtle movement in the videos. It was also my first opportunity to be in direct dialogue with an art history that, up until that point, I had only alluded to. It’s one thing to be influenced by the impressionists, or the futurists, or American Western painting; it’s another thing to be right next to them. It was a pleasure to see how the collection acted upon the work I made, and the other way around. SBMA gave me a lot of freedom to decide where the work went within the galleries. In the late nineteenth century/early twentieth century painting gallery—full of Monets, Pissarros, and Matisses—they gave me the opportunity to make a brand-new work in response to those paintings. It was an exciting opportunity to engage in conversation with pre-existing works.

CW: Coming full circle from your semester in Rome.

BB: Right! It never hurts to have an abiding love of art history.

———

Carmen Winant is an artist and writer currently based in Brooklyn. She is a regular contributor to Frieze magazine, Artforum.com, X-TRA Journal, and The Believer magazine, and is a co-editor of the online arts journal The Highlights.

Image: Brian Bress, Cowboy (Brian led by Peter Kirby), 2012

High definition single-channel video (color), high definition monitor and player, wall mount, framed.

Interventions: Brian Bress (installation view) at Santa Barbara Museum of Art, July 2012

Images courtesy of Santa Barbara Museum of Art

Brian Bress’s Interventions

By Carmen Winant

Brian Bress, an artist who comfortably straddles the lines between painting, sculpture, video and photography, has just closed his first solo museum exhibition in the United States at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. The show, titled Interventions, is comprised of five video portraits dispersed throughout the museum galleries. Here, Bress speaks with Carmen Winant about his evolution as a maker, the difference between humor and absurdity, and the pervasive influence of Los Angeles.

Carmen Winant: I think your videos are so curious, vexing, funny, and strange. We will get to all of those qualities, but before we do, I am curious about your art-making background. Did you start right away in video, or work your way there from other mediums such as photography or painting? Your current video portraits lead me to believe the latter.

Brian Bress: There has been a lot of back and forth between various mediums. I went to RISD as an undergradate thinking that I would be an illustrator. I don’t know what compelled me, but once there, I ended up majoring in film, video, and animation. I could already draw pretty well, and wanted to learn something totally new. That was before the popularity of non-linear editing, or computer editing, and I learned a lot of non-traditional filmmaking techniques in the program.

Right in the middle of that process, I decided to go to Rome through the RISD Honors program, and focus exclusively on painting. I did that for a year, and then came back to Providence and jumped right back into my animation projects. That back-and-forth between those mediums is how it’s been for most of my life. Right after I completed my undergrad degree, I started going back to traditional painting. When I applied to UCLA’s graduate program a few years later, I did so without any video or animation work. It was all painting and drawing. Pretty soon after arriving there, I started working on time-based projects.

CW: In retrospect, your interest and training in video/film and traditional painting—or your toggling between them—really seem to make sense in regard to your current practice.

BB: I like to think that the work that I am doing now holds the same concerns and interests for someone who is interested in painting as for someone interested in video.

CW: Your work has been frequently described as both absurd and humorous. That got me thinking about the difference between the two qualities, which are often conflated. Much more so than humor, absurdity is really about failure—failure to find real meaning or value in life. It’s entangled with nihilism in that sense. How would you define it?

BB: I definitely see them as distinct characteristics, totally separate from one another. Humor is for me about creating, and breaking, everyday patterns. There is a great Dick Van Dyke Show episode in which he has to go to a school and explain to a class what he does, which is writing comedy for television. He walks across the room, and trips and falls, and all the students laugh. He proceeds to explain to them why they found it funny: he was putting one foot after the other, which created the expectation that he was going to continue that pattern. But when he tripped it disrupted that expectation and it surprised them. That kind of wonderment is the pleasure that I get from humor and the way that it operates. As opposed to absurdity, which is more of a critique of reality and the ways in which it doesn’t add up. The absurd functions by critiquing what “makes sense” in the real world.

CW: Where does that interest figure in your own work?

BB: I don’t attempt to be funny or absurd in my work. That just wouldn’t be very smart or interesting. It would come off as hammy or overdone, or lacking real subtlety. My intention is not necessarily to ride between the two, though I can sometimes look back at work and observe that it behaves that way. Ultimately, absurdity and humor are the byproduct of ideas, rather than the ideas themselves.

CW: Your reference to the Dick Van Dyke Show is actually a nice segue; I’d like to talk a little about your relationship to the entertainment industry. You live in Los Angeles. I can’t help but wonder, as an artist making elaborate, vaguely narrative and character-based low-fi productions, how the industry town has affected your work.

BB: The more I live and make work in LA, from a logistical standpoint, the more I can’t imagine making work anywhere else. The technical resources here are incredible: equipment, cameras, props, experienced people. I just hired a great cinematographer named Michael Totten for a recent piece. He filmed the character with a high-speed, very sophisticated camera. So, I am aware that there are resources that only Los Angeles can provide.

CW: Does the industry affect you from a creative standpoint?

BB: To be honest, I am not always too conscious of how the entertainment industry rubs off on my studio practice. But it does, in funny ways. My girlfriend is a set decorator on Disney television shows. In the back of my mind, I know how it’s really done. I know what resources are available to create the aesthetic of the super-real—I am going to call it that as supposed to surreal. The aesthetics of those Disney shows is heightened and exaggerated. Sometimes I like that aesthetic and sometimes I don’t, but I am aware of it. But I deliberately try not to be too conscious of the ways that it affects my work.

CW: Do you work with your girlfriend collaboratively?

BB: No, not so much. She is more of a fixer. She knows where everything is. She knows all the prop houses. Which I don’t rent from—I make everything. But sometimes, if it’s a mechanical thing off-camera, she knows exactly where to get it. For instance, I recently needed a giant, rotating pedestal, and she told me exactly where to go in Burbank to find it. You can’t easily acquire that kind of knowledge on your own.

CW: Continuing that strand—the occasional challenge of working alone—I am wondering: are you in every video that you make?

BB: I appear in a lot of them, though not all of them. That is shifting. I used to be in all of them because I knew what I wanted, and it was easier to perform myself than direct someone else. Or sometimes I didn’t know what I wanted. In those cases, I just knew what I wanted the image to look like. The whole purpose in that sense was to create an environment that was inspiring enough, beautiful enough, interesting enough. I could try out unexpected things in front of the camera, edit later, and find the piece that way. So, it would have been impossible to direct someone else. What would I say? “Okay, improvise, because it’s so interesting to you to be here”? That’s not something I could ask of, or expect from, someone else. But, as I’ve worked with scripts and focused the experiments, I have been able to hand off that task to other people.

CW: When you were the only one performing, was someone else behind the camera?

BB: Before 2010, which is when I did my first scripted piece (with one prior exception), I would turn on the camera, run in front of the camera, and do my thing. Every clip ended with me walking back to press the red button.

CW: I’m interested in how our relationship to viewing (and curating) videos has shifted as the form becomes less marginal. I did an interview with last year with Ed Halter and Thomas Beard of Light Industry, and they made a really interesting point about how curators often show videos the same way they do two-dimensional work—without any sensitivity to the medium’s needs. They were trying to shift that paradigm by creating a “film program” during the 2012 Whitney Biennial, as opposed to, say, looping videos in the corner. Do you agree with that argument? What is the ideal way for your own work to be shown?

BB: More than anything, I think it depends on the piece. There are pieces that I’ve made in the past that have more of a narrative, cinematic bent to them. I would love for people to sit down in a dark room at the beginning and watch until the end, much like going to the movies. The works that I have been making recently, on flat panel monitors inside of colored frames, are much more about the entire object, not just about the image being displayed on the monitor. They are about the thing hanging on the wall, and sensing that there is space behind and around the object.

CW: You are referring to the work in the Santa Barbara Museum of Art show, correct? Can you speak a little more to it, and your interests in creating it?

BB: There are a few things that drove my curiosity. The first is the paring down of motion and gesture. There is an uncanny feeling that occurs when something that you didn’t expect to move in fact does. The other interest is what I just mentioned—playing with space and depth within an object on the wall.

CW : That show consists of five video portraits spread throughout several floors and across different galleries devoted to different artistic genres. It’s an unusual way to show work, particularly in a conventional museum space.

BB: That was [SBMA curator] Julie Joyce’s idea, and I loved it from the beginning. As I mentioned before, I am interested in playing with how people perceive the work, what their expectations are for a framed object on the wall, and the subtle movement in the videos. It was also my first opportunity to be in direct dialogue with an art history that, up until that point, I had only alluded to. It’s one thing to be influenced by the impressionists, or the futurists, or American Western painting; it’s another thing to be right next to them. It was a pleasure to see how the collection acted upon the work I made, and the other way around. SBMA gave me a lot of freedom to decide where the work went within the galleries. In the late nineteenth century/early twentieth century painting gallery—full of Monets, Pissarros, and Matisses—they gave me the opportunity to make a brand-new work in response to those paintings. It was an exciting opportunity to engage in conversation with pre-existing works.

CW: Coming full circle from your semester in Rome.

BB: Right! It never hurts to have an abiding love of art history.

———

Carmen Winant is an artist and writer currently based in Brooklyn. She is a regular contributor to Frieze magazine, Artforum.com, X-TRA Journal, and The Believer magazine, and is a co-editor of the online arts journal The Highlights.

Image: Brian Bress, Cowboy (Brian led by Peter Kirby), 2012

High definition single-channel video (color), high definition monitor and player, wall mount, framed.

Interventions: Brian Bress (installation view) at Santa Barbara Museum of Art, July 2012

Image Courtesy of Santa Barbara Museum of Art

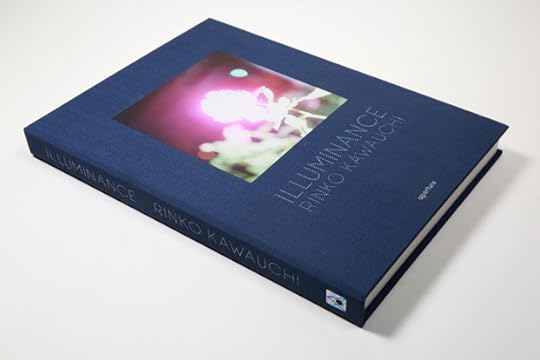

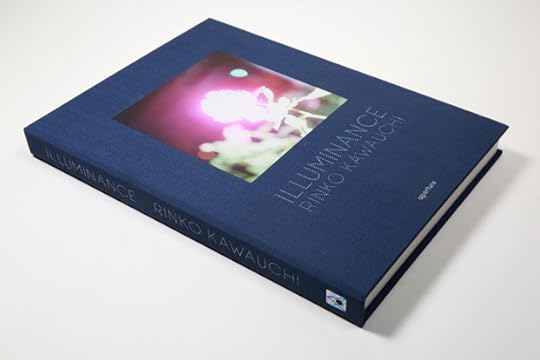

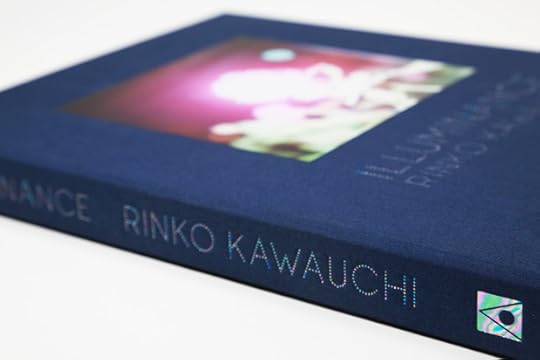

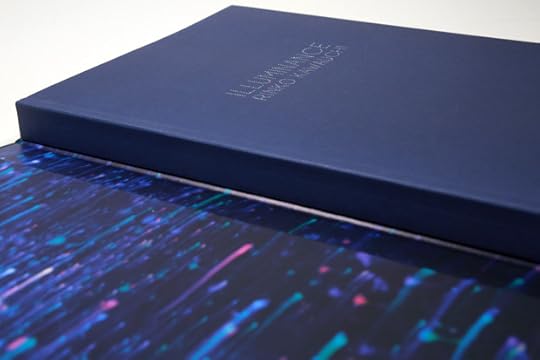

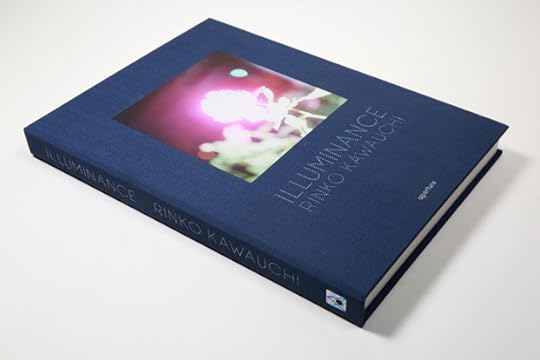

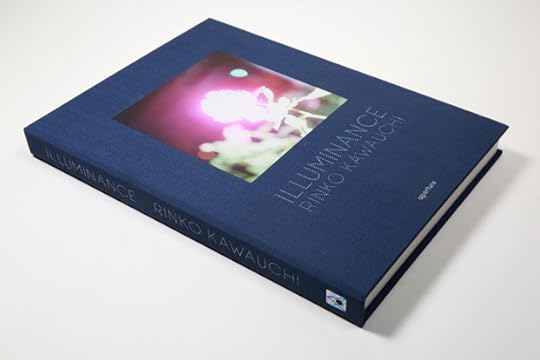

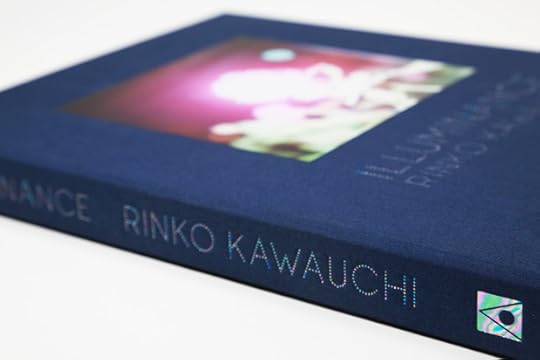

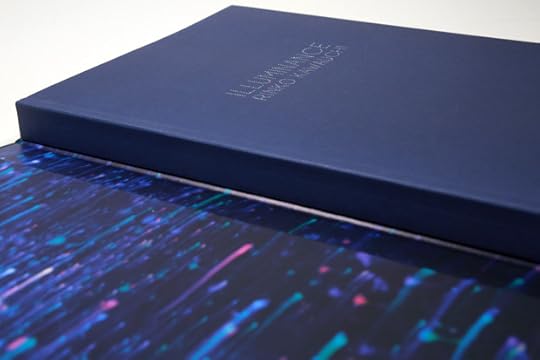

Rinko Kawauchi – Illuminance – reprinted

In 2001, Rinko Kawauchi published three astonishing photobooks simultaneously—Utatane, Hanabi, and Hanako—and established herself as one of the most innovative newcomers to contemporary photography. Her work was frequently lauded for its nuanced palette and offhand compositional mastery, as well as its ability to incite wonder via careful attention to tiny gestures and the incidental details of her everyday environment. Now, ten years after her precipitous entry onto the international stage, Aperture has published Illuminance, the first volume of Kawauchi’s work to be published outside of Japan.

In Illuminance , Rinko Kawauchi continues her exploration of the extraordinary in the mundane, drawn as she is to the fundamental cycles of life and to the fact that the seemingly inadvertent, fractal-like organization of the natural world resolve into formal patterns.

Gorgeously reprinted, bound in deep-blue cloth with Japanese binding, this impressive compilation of mostly previously unpublished images is proof of Kawauchi’s unparalleled, unique sensibility and her ongoing appeal to lovers of photography.

IlluminancePrice: $60.00

IlluminancePrice: $60.00  Untitled, from IlluminancePrice: $2,500.00

Untitled, from IlluminancePrice: $2,500.00

Reprint: Illuminance / Rinko Kawauchi

In 2001, Rinko Kawauchi published three astonishing photobooks simultaneously—Utatane, Hanabi, and Hanako—and established herself as one of the most innovative newcomers to contemporary photography. Her work was frequently lauded for its nuanced palette and offhand compositional mastery, as well as its ability to incite wonder via careful attention to tiny gestures and the incidental details of her everyday environment. Now, ten years after her precipitous entry onto the international stage, Aperture has published Illuminance, the first volume of Kawauchi’s work to be published outside of Japan.

In Illuminance , Rinko Kawauchi continues her exploration of the extraordinary in the mundane, drawn as she is to the fundamental cycles of life and to the fact that the seemingly inadvertent, fractal-like organization of the natural world resolve into formal patterns.

Gorgeously reprinted, bound in deep-blue cloth with Japanese binding, this impressive compilation of mostly previously unpublished images is proof of Kawauchi’s unparalleled, unique sensibility and her ongoing appeal to lovers of photography.

IlluminancePrice: $60.00

IlluminancePrice: $60.00  Untitled, from IlluminancePrice: $2,500.00

Untitled, from IlluminancePrice: $2,500.00

October 24, 2012

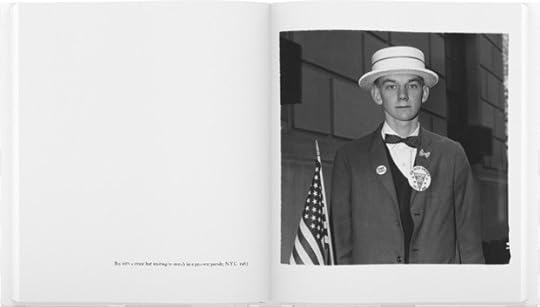

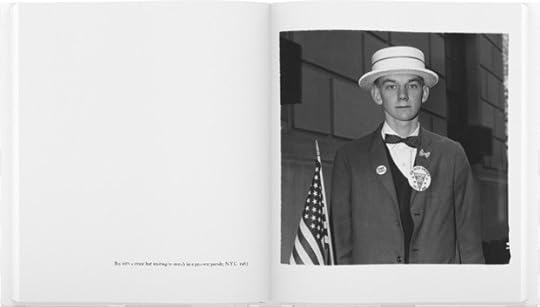

Diane Arbus – Guggenheim Grants exhibition at KMR Arts Gallery

A new photography exhibition, Diane Arbus: Guggenheim Grants, 1963–1967, will be on view at KMR Arts Gallery from October 26 through December 29, 2012.

This show of vintage prints by the influential photographer focuses on the critical turning point within Diane Arbus’s body of work as she applied for and was awarded two Guggenheim grants. Arbus received these grants at a time when her style was maturing and they provided Arbus complete artistic and financial freedom to explore her interest in “American Rites, Manners, and Customs,” and the intense, provocative images and subjects that would occupy her for much of her career.

Diane Arbus: Guggenheim Grants, 1963–1967

October 26–December 29, 2012

KMR Arts Gallery

Washington Depot, Connecticut

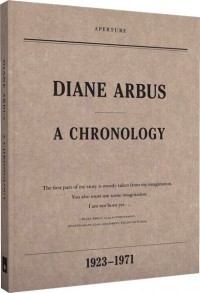

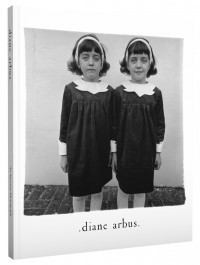

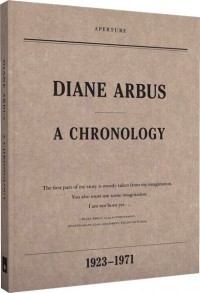

Diane Arbus: A ChronologyPrice: $29.95

Diane Arbus: A ChronologyPrice: $29.95  Diane Arbus: An Aperture MonographPrice: $39.95

Diane Arbus: An Aperture MonographPrice: $39.95

“Diane Arbus: Guggenheim Grants”

KMR Arts Gallery announces the opening of its latest show, Diane Arbus: Guggenheim Grants, 1963–1967, on view October 26 through December 29, 2012.

This show of vintage prints by the influential photographer focuses on the critical turning point within Diane Arbus’s body of work as she applied for and was awarded two Guggenheim grants. Arbus received these grants at a time when her style was maturing and they provided Arbus complete artistic and financial freedom to explore her interest in “American Rites, Manners, and Customs,” and the intense, provocative images and subjects that would occupy her for much of her career.

Diane Arbus: Guggenheim Grants, 1963–1967

October 26–December 29, 2012

KMR Arts Gallery

Washington Depot, Connecticut

Diane Arbus: A ChronologyPrice: $29.95

Diane Arbus: A ChronologyPrice: $29.95  Diane Arbus: An Aperture MonographPrice: $39.95

Diane Arbus: An Aperture MonographPrice: $39.95

October 23, 2012

Photography Reading Shortlist – 10.23.12

›› London’s Tate Modern Museum opens Moriyama + Klein, the first exhibition to look at the relationships between Daido Moriyama and William Klein—two photographers whose gritty, urgent contributions to street photography are inextricably linked. Time magazine’s LightBox has launched William Klein + Diado Moriyama: Double Feature, a duo of video profiles on Klein and Moriyama, shot in and around the studios of the men themselves, as The Guardian and Telegraph (which also offers a review and conversation with Moriyama) take a look at William Klein and Daido Moriyama: in pictures.

“If Eggleston is the 1970s TV sitcom with toilets tucked safely out of view, American Surfaces is Big Brother, the uncut version. This is what democracy looks like.”

›› Extremes of the banal and the sublime in the American landscape were under investigation in a post by Blake Andrews—who takes a closer look at the filthy photographs of Stephen Shore—and in Flak Photo’s Looking at the Land, a web-based exhibition looking at current ideas about photographing landscape and the tradition of picturing place.

›› The New Photography 2012 exhibition is on at MoMA, featuring the work of Michele Abeles, Anne Collier, Zoe Crosher (whose The Disappearance of Michelle DuBois Volume 4 has just been released), Shirana Shahbazi, and the collective Birdhead (Ji Weiyu and Song Tao), artists who, in MoMA’s words, “speak to the diverse permutations of photography in an era when the definition of the medium is continually changing.” LightBox and Photo Booth posted slideshow previews of the work in the show.

“It’s easy to forget now, but instant camera maker Polaroid once matched the mythos — and ubiquity — of Apple”

›› New York Magazine senior editor Christopher Bonanos maps the rise and near-collapse of Polaroid in a new book, offering up a concise cultural history of the brand and its visionary leader. Wired catches up with the Instant writer for “Why Polaroid Was the Apple of Its Time,” which inevitably addresses why it was the Instagram of its time as well. Also inspired by Instant: The Story of Polaroid, The Atlantic launches the headline “Before Sexting, There Was Polaroid”, a prelude to an excerpt from the book addressing privacy and intimacy in the age of instant film.

›› Books were celebrated and considered at the New York Art Book Fair late last month, in a Photo Booth slideshow of “Books as Muses,” and in the Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards shortlist, which will be narrowed down to winners in the First PhotoBook and PhotoBook of the Year categories and announced at Paris Photo on November 14. On the subject of photobooks, this clip of Life’s the Beach photographer Martin Parr introducing his latest limited-edition monograph has “viral” written all over it, no?

———

Follow Aperture on Twitter(@aperturefnd) for a daily feed of photography-related news and commentary.

Image: Print from The Disappearance of Michelle DuBois Volume 4, Zoe Crosher

October 19, 2012

Barney Kulok and Joel Smith: Artist Talk

Join photographer Barney Kulok and Joel Smith, curator of photography at the Morgan Library & Museum, for a conversation about photography’s interactions with the world of architecture, as well as Kulok’s experience photographing the construction of Four Freedoms Park on Roosevelt Island—the subject of his new book Building: Louis I. Kahn at Roosevelt Island ($75.00 via Aperture). The conversation will be followed by a book signing.

This event is presented in association with Archtober, Architecture and Design Month New York City.

In Conversation: Barney Kulok and Joel Smith

Rescheduled Time and Date: TBA

Aperture Gallery

New York

Image: Barney Kulok, Untitled (Cobble Constellation), 2011 Building:Price: $75.00

Building:Price: $75.00

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers