Aperture's Blog, page 204

January 22, 2013

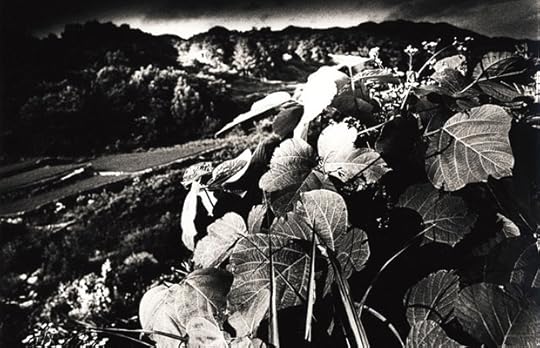

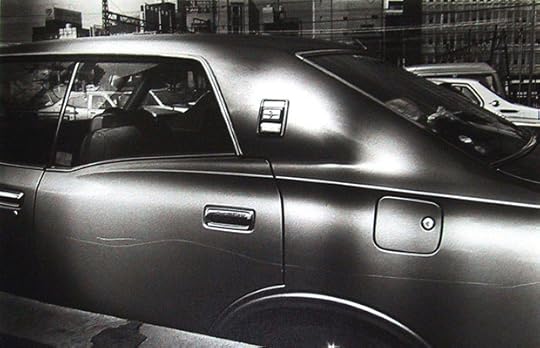

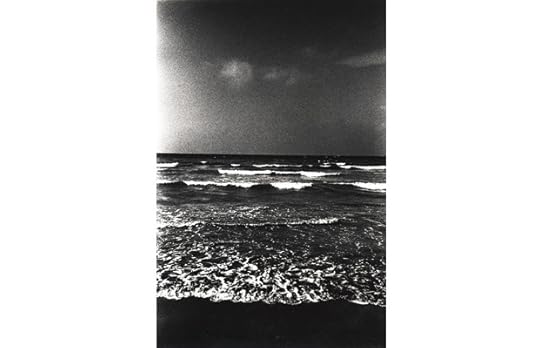

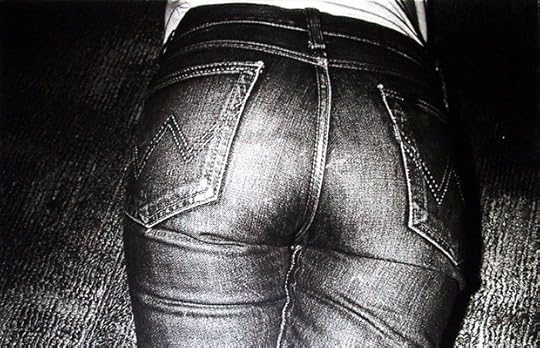

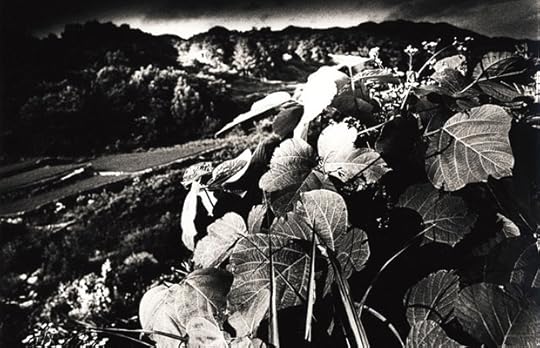

Daido Moriyama: Vintage Prints

Mt. Daibosasu (No. 2001), 1981 © Daido Moriyama

In recent years, Japanese photographer Daido Moriyama has been the subject of increasing curatorial and critical interest, a trend that culminated with large survey exhibitions of his work at the National Museum of Art in Osaka, Japan, in 2011 and, with photographer William Klein, at London’s Tate Modern until January 20. Now on view in Zurich is an exhibition of vintage prints at Galerie Bob van Orsouw. In addition to Moriyama’s familiar themes—close-up views of women seen from behind; light reflecting on cars; blurry shots of people passing through public spaces—the show also includes lesser-known landscape views. Moriyama’s high-contrast printing gives an almost hallucinogenic quality to the sea seen from above, the choppy water appearing like the hide of an enormous beast. The sunlight streaming around a giant sunflower nearly burns the edges of the image.

Guardrail (No. 2231), 1983

Memory of a Dog 2 (No. 2044), 1982 © Daido Moriyama

How to Create a Beautiful Picture 14: Zushi (No. 2735), 1988 © Daido Moriyama

How to Create a Beautiful Picture 1: View from the Window (No. 2608), 1986 © Daido Moriyama

New Japan Scenic Trio 2: Ueno Terminal Station, 1982 © Daido Moriyama

A Journey To Nakaij 1 (No. 2364), 1984/2003 © Daido Moriyama

Mt. Daibosasu (No. 2001), 1981 © Daido Moriyama

Aperture has enjoyed a fruitful relationship with Moriyama, which includes the publication of two books—the limited-edition TKY, in 2011, and the brand-new Labyrinth—and the re-creation of his 1974 performance Printing Show at our New York gallery. For more about Moriyama, see this interview, originally published in Aperture magazine issue 203.

The exhibition at Galerie Bob van Orsouw in Zurich remains on view until February 23, 2013.

January 17, 2013

Remembering Shomei Tomatsu (1930-2012)

Shomei Tomatsu and John Junkerman, May 2011.

“Shomei Tomatsu: Occupation Okinawa,” by Lesley A. Martin

Shomei Tomatsu’s work served a critical purpose at a transitional moment in Japanese postwar photography: as a catalyst toward the rejection of a classic photojournalistic approach. As members of VIVO, a photographers’ collective formed in 1959, he and his colleagues were inspired, in part, by Magnum and the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Capa—yet determined to move beyond what they considered to be the reductionist humanism of war-era reportage, finding greater affinity with the work of William Klein and Robert Frank. VIVO, with Tomatsu at its core, defined and defended a “subjective documentary” approach, producing work that hovered between pure description and an expressionistic use of stylized printing techniques, dramatic angles, and carefully embedded symbolism. While the collective was ultimately short-lived (it disbanded in 1961), many of the VIVO photographers produced bodies of work that attempted to narrate their own memories and experiences of war, the dramatic shifts of postwar Japanese society, and the shattering impact of the atomic bombs and defeat on the Japanese landscape and psyche. Among the most powerful of these artistic responses is Tomatsu’s own Nagasaki—11:02 (1966), a meditation on the lingering effects, both psychological and physical, of that city’s bombing.

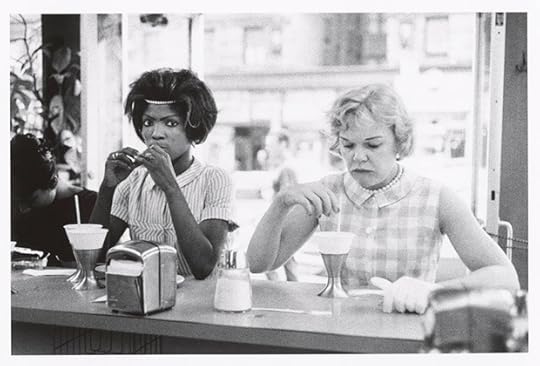

In the late 1950s Tomatsu initiated a major series focusing on the American occupation in Japan, committing to photograph many of the U.S. bases on Japanese soil. While the U.S. occupation officially came to an end in 1952, the presence of American forces remained a major influence on the social landscape into the 1970s—and indeed, it is still a point of contention today. Tomatsu’s pilgrimage culminated in a 1968 visit to Okinawa, which remained officially off-limits for Japanese nationals until its reversion to Japanese sovereignty in 1972. Published sporadically as series, titled Occupation and Chewing Gum and Chocolate, the work encompasses themes of the friction between American and traditional Japanese mores; the alien-presence of white and black soldiers in an otherwise homogeneous society, with a particular focus on the impact of U.S. soldiers’ presence on traditional Japanese gender roles; and the profoundly changed nature of Japanese society at large—in a word, its Americanization. Or, as Tomatsu identified it in some of his extensive writings at the time, the “Coca-Colonization” of the world, and especially of Japan.

Untitled (Kadena), 1972 © Shomei Tomatsu

While these issues were pervasive in much of postwar Japan, Okinawa came to hold particularly compelling interest for Tomatsu. A chain of islands off the southernmost tip of “mainland” Japan, Okinawa has a charged history—as a site of epically brutal and intense fighting during the war, and then as a captive territory with a slow and controversial reversion back into Japanese hands. Additionally, its heavy use as a staging area for bombing runs to Vietnam in the late 1960s and early ’70s solidified Okinawa’s role as a symbol for the abuses of American power.

Untitled (Okinawa City), 1979 © Shomei Tomatsu

Equally critically, however, Okinawa holds a semi-sacred place in many Japanese minds—despite the mainland’s own fraught history of colonization of the islands—thanks to its unique, Polynesian-influenced native culture and history. In this era, many came to see Okinawa as a repository for the native roots of Japanese culture, then under attack from modernization and Westernization—not unlike the American Indian and Hawaiian cultures, which took on similar symbolic value in the United States during that same time.

As such, Okinawa has long been a crucial point of reference for Japanese protest and for photographers—the subject of many politically and sociologically concerned books. Included in this roster are several by Tomatsu, such as the renowned Okinawa, Okinawa, Okinawa (Shaken, 1969), a politically driven book deeply obsessed with the presence of the American air force, which he published after his first extended visit to the islands. In fact, from that very first visit, Tomatsu was enamored with Okinawa—which was paradoxically one of the areas most impacted and defined by the presence of the U.S. military and yet also a refuge of sorts from what he considered the anathematic if inexorable mutations of Japanese society. It is this circulation between critique and celebration of the Okinawan urban landscape, marked by clear signs of both pop Americana and a cheery South Seas palette, that gives Tomatsu’s work tension and form—in particular in his more recent color photographs. (The selection in these pages includes images taken as early as 1971, when he first began to use color film; he continues to shoot primarily in color today.) To a large degree, the photographer credits his switch to color photography as a response to Okinawa’s color- saturated landscape, writing in his 1975 book Taiyo no empitsu (The pencil of the sun): “In Okinawa, it seemed a natural step to switch to color photography . . . but even after returning to Tokyo, I did not go back to monochrome . . . I realized later that this was because my fixation on America had weakened. America flashes into and out of view in black and white. In color, America’s presence is diminished” (translated in his 2004 retrospective survey, Skin of the Nation, from Yale University Press).

Untitled (Okinawa City), 1972 © Shomei Tomatsu

The images reproduced here and in the original article comprise a selection from Tomatsu’s earlier work alongside some of his more recent photographs. In 2010, after several extended stays interrupted by stints of living on mainland Japan, Tomatsu retired permanently to the main island of Okinawa, where he photographed until his death in December 2012.

–

Lesley A. Martin is publisher of the Aperture book program and of The PhotoBook Review, a newsprint journal dedicated to the evolving conversation surrounding the photobook.

January 15, 2013

Philip Gourevitch: Varieties of the Apocalypse

For What Matters Now, a regular column in the new Aperture, our editors ask leading thinkers, scholars, and artists to explain new developments and examine pressing matters in photography. Below is journalist Philip Gourevitch’s contribution to the Spring issue; for the other four, subscribe now or pick up the magazine when it launches on February 26.

Jonas Bendiksen, Klo, Norway, 2012. Courtesy Jonas Bendiksen.

Long before the words “climate change” were part of daily discourse and our understanding of our destiny, Robert Frost wrote a short poem that told us what to expect: “Some say the world will end in fire, / Some say in ice.” Those lines leapt to mind when I saw this fantastic picture—at once operatic and existential—and got to thinking about how Jonas Bendiksen harnesses Instagram, the most to-the-minute smartphone technology, to depict indelibly the primal line humankind is walking (individually and as a species) between varieties of apocalypse.

He reminds us beautifully, too, that “man-made” is also natural, and he makes us ask if perhaps that means it is natural for us to be destroying nature.

—Philip Gourevitch, a longtime staff writer at the New Yorker, is the author most recently of The Ballad of Abu Ghraib (originally published as Standard Operating Procedure, Penguin, 2008)

Everything Was Moving: Photography from the 60s and 70s

By Isabel Stevens

Li Zhensheng, Several hundred thousand Red Guards attend a “Learning and Applying Mao Zedong Thought” rally in Red Guard Square (formerly People’s Stadium). Harbin, Heilongjiang province, September 13, 1966

The Barbican’s ambitious survey of photography from the 1960s and ’70s offered up a dual portrait of the times. On one hand, it was an exhibition about history, charting the seismic shifts occurring all over the world in those decades. Its itinerary took in Apartheid-era South Africa, the American civil rights movement, post-colonial Mali, the Vietnam war, China in the grip of the Cultural Revolution, and more, exploring the myriad ways such events could be captured through a lens. Compare Li Zhensheng’s records of Maoist China in the early ’60s—spectacular, stitched-together panoramas of epic rallies—with Ernest Cole’s tender but damning sketches of township life under Apartheid for an example of two photographers both recording vital, chilling moments furtively, under oppressive regimes, and at the same point in history but in utterly contrasting styles.

On the other hand, the exhibition delved deeper into the medium’s own history, including figures such as William Eggleston, Boris Mikhailov, Shomei Tomatsu, and even the Pop artist Sigmar Polke, who were all trying to wrestle photography away from documentary and the “decisive moment” during these years by experimenting formally and conceptually. This gave a largely successful insight into photography’s splintering form and status at that time. Tomatsu’s conjuring of the horror of Nagasaki from only a bizarre, enigmatic shot of a melted bottle, and Eggleston’s infamous Los Alamos series, in particular, bring a welcome sense of ambiguity and the unreal, although these aesthetic experimenters do feel outnumbered at times. The mindset that dominates throughout is definitely a documentary one—the photograph as evidence, or, as in many cases here, as protest song.

Boris Mikhailov, Yesterday’s Sandwich / Superimpositions, late 1960s–late 1970s. Courtesy Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin © Boris Mikhailov, DACS 2012

With so many historical excavations, the exhibition occasionally felt too expansive, but such a refreshing, revisionist stance on photography’s Western-oriented history threw up novel, intriguing cross-global juxtapositions and moments of unexpected simultaneity. (Remarkably, of the twelve photographers included in the exhibition, Western figures were in the minority—there were even more African than American photographers on show.)

Oppositions came into play where violence is concerned. Although Larry Burrows’s close-up testimonials of soldiers’ suffering never slide into glorification, Polke’s grainy glimpses of animal fights in Afghanistan make them seem even more monumental, more in awe of warfare. Differing attitudes towards America’s infiltration of foreign cultures was also evident. Whereas Malick Sidibé’s portrait of burgeoning Bamako youth culture high on James Brown welcomes it, Tomatsu remains wary, capturing fragmented views of postwar Japan on the fringes of American military bases.

Four unlikely companions came together here: Raghubir Singh with his rebellion against the monochrome colonial view of India; Eggleston and his dye-transfer transformation of the American South; Burrows and his dramatic action tableaux, which brought the hues of Vietnam’s mud and blood alive on the pages of Life; and Mikhailov and his surreal “sandwiches,” darkroom concoctions which deliberately abuse the techniques of Soviet social realist montage—all are linked by their bold rejection of black and white at a time when color wasn’t allowed in photography’s vocabulary.

Above: Raghubir Singh, Below the Howrah bridge a Marwari bride and groom after rites by the Ganges, 1968 © 2012 Succession Raghubir Singh. Below: Bruce Davidson, Black Americans, New York City. From the series ‘New York (Life)’ From New York, 1961-65 © Bruce Davidson / Magnum Photos

Unexpected connections surfaced elsewhere. Stylistically, there’s not much common ground between Graciela Iturbide’s lyrical portraits of Mexico’s indigenous peoples (sadly a little squeezed here) and Bruce Davidson’s first-hand account of the civil rights movement, but their methodology binds them: both photographers were roaming outside their comfort zones, daring to choose intimacy over detachment. Davidson’s troubled landscapes also infect Eggleston’s survey of the same terrain only a few years later, highlighting the sense of unease lingering in Eggleston’s peculiar, off-kilter snapshots of empty diners and motels.

The show’s most powerful instance of synchronicity was also its most harrowing, and was plucked from another segregated landscape. Ernest Cole and David Goldblatt both prowled the streets of Johannesburg—the latter able to wander and photograph where he pleased, the former forced to record Apartheid’s stark and cruel divisions illicitly, only able to work as a photographer after somehow convincing the authorities he was “colored” and not “black.” Yet they were both drawn to the same subjects—in particular, that anomalous, caring relationship between black nannies and white children. Goldblatt pictures a young boy standing, his hand resting on his seated nanny’s shoulder in a quiet moment of affection, but the boy’s unsettling, paternalistic pose also doesn’t go unnoticed. Cole meanwhile meets the gaze of a boy as he twists away from the faceless nanny who tightly grips his hand. Small, subtle gestures they may be, but they’re devastating in their condemnation of a society that would make such a loving relationship so fleeting. Indeed, lesser-known agitators such as Cole and Li are the show’s heroes, providing some of the most shocking images. Both were snapping furtively, Cole concealing his camera in a paper bag, Li his negatives under floorboards. Cole’s fate was impoverished exile; while at the height of the cultural revolution, Li spent two years in a labor camp.

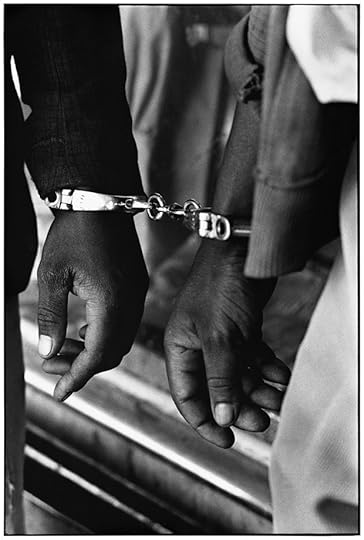

Ernest Cole, Handcuffed blacks were arrested for being in white area illegally, from House of Bondage, ca. 1960–1966. The Ernest Cole Family Trust, Courtesy of the Hasselblad Foundation, Gothenburg, Sweden

This was an ambitious marathon of an exhibition—one that pressed “pause” at a tumultuous time in history, offering myriad glimpses into different societies all over the world, drawing together a truly global selection of photography’s pioneers and protesters who are rarely exhibited side by side.

–

Isabel Stevens works at the film magazine Sight & Sound and writes on photography and film for a variety of publications, including Source and The Wire.

January 14, 2013

Vik Muniz Studio Visit—01.10.13

Artist Vik Muniz in his studio. Photo courtesy of Sb Cooper.

The artist speaks to event attendees in his studio. Photo by Sammy Marrus.

Artist Vik Muniz in his studio. Photo courtesy of Sb Cooper.

Artist Vik Muniz in his studio. Photo courtesy of Sb Cooper.

Artist Vik Muniz in his studio. Photo courtesy of Sb Cooper.

Artist Vik Muniz with his wife, Malu Barreto and their daughter, Dora. Photo courtesy of Sb Cooper.

Artist Vik Muniz signing books in his studio. Photo courtesy of Sb Cooper.

Artist Vik Muniz signing books in his studio. Photo courtesy of Sb Cooper.

Vik Muniz with Aperture patrons in his studio. Photo courtesy of Sb Cooper.

Artist Vik Muniz in his studio. Photo courtesy of Sb Cooper.

Glimpse of the artist. Photo courtesy of Sb Cooper.

A photo gallery highlighting the January 10 Vik Muniz Studio Visit

Patrons, board members, and supporters joined Aperture in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, for an exclusive tour of Vik Muniz‘s studio. Muniz is an American artist of Brazilian origin that uses unconventional materials—like chocolate sauce or spaghetti marinara—to create artful images. Muniz discussed his multiple projects with Aperture and signed copies of his book Reflex: A Vik Muniz Primer (Aperture, 2005). Following the tour, the group enjoyed lunch at a popular Brooklyn restaurant, The General Greene.

This tour was the first in a series of events exclusively organized for Aperture Patrons. Aperture Patrons support the organization with a $1,000 annual contribution and receive a number of benefits including invitations to private openings, discounts on Aperture published books and photographs, a complimentary subscription to Aperture magazine, and much more!

For more information on Aperture Foundation’s Patron Program please visit our website.

Reflex

Reflex$39.95

January 10, 2013

Remembering Gigi Giannuzzi

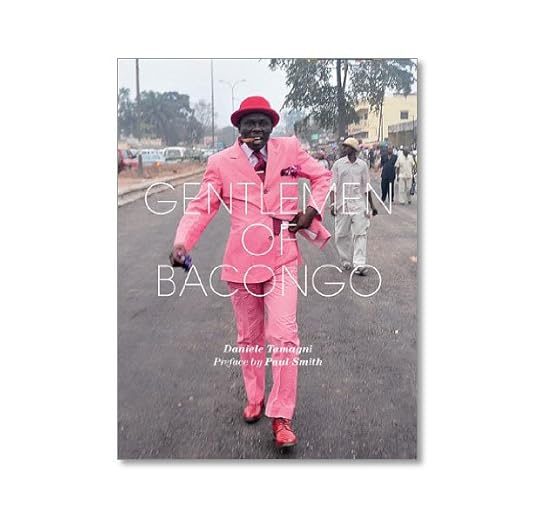

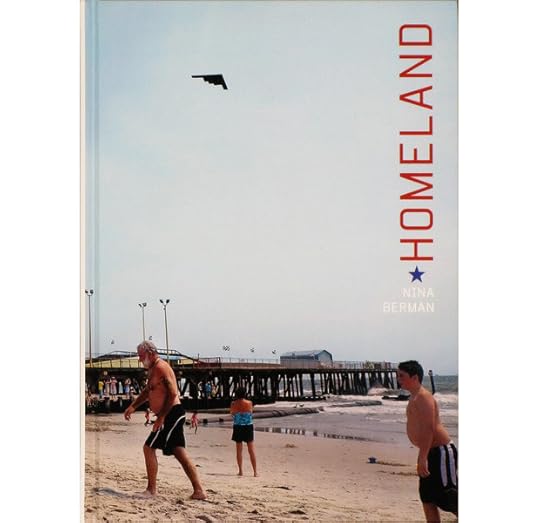

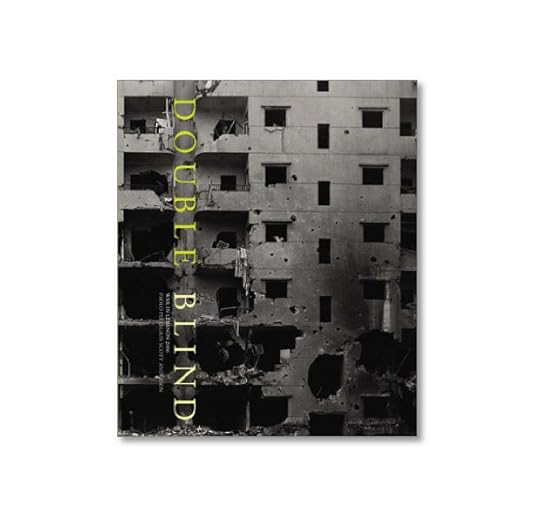

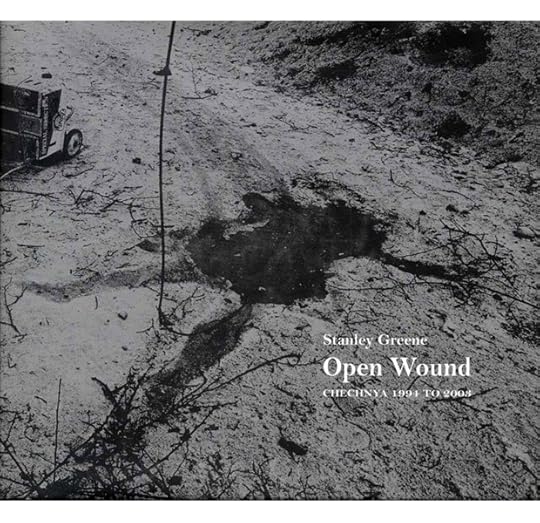

The end of 2012 was a sad one for the photography community with the loss of Trolley Books publisher Gigi Giannuzzi. (Read the Guardian’s obituary here.) The photobook community is small and passionate, and Gigi was a true maverick within it. He was a courageous publisher, known for championing hard-hitting projects that challenged viewers. He was also a maverick character—in a passionate, mad-genius kind of way. No matter the subject or the photographer, Gigi knew how to make a beautiful book. As chaotic and larger-than-life as his persona and presence were, his books provide a quiet place of ordered and nuanced complexity. The selection, the sequencing, and the pacing of his books are flawless. There are never too many pictures, and the books achieve a kind of simplicity that looks easy but is incredibly difficult to pull off. He knew how to shape a story and to engage viewers page to page over a sustained period of looking. The books he published continue to unfold over multiple readings. His talent as a bookmaker and especially his belief in photography and photographers will be missed. He leaves behind an important and lasting legacy. Here is a selection of a few of our favorite books he helped bring into the world.

–

Denise Wolff is senior editor of Aperture’s book-publishing program.

Gentlemen of Bakongo, Photographs by Daniele Tamagni

Trolley, London, 2009

A Million Shillings: Escape from Somalia, Photographs by Alixandra Fazzina

Trolley, London, 2008

Homeland, Photographs by Nina Berman

Trolley, London, 2008

Double Blind: Lebanon Conflict 2006, Photographs by Paolo Pellegrin

Trolley, London, 2007

iWitness, Photographs by Tom Stoddart

Trolley, London, 2004

Phil and Me, Photographs by Amanda Tetrault

Trolley, London, 2004

Purple Hearts, Photographs by Nina Berman

Trolley, London, 2004

Ghetto, Photographs and text by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin

Trolley, London, 2003

Open Wound: Chechnya 1994–2003, Photographs by Stanley Greene

Trolley, London, 2003

Agent Orange: "Collateral Damage" in Viet Nam, Photographs by Philip Jones Griffiths

Trolley Books, London, 2003

The Chain, Photographs by Chien-Chi Chang

Trolley, London, 2002

January 9, 2013

Aperture Portfolio Prize 2013

January 8, 2013

Aperture Magazine’s 2013 Relaunch

On the cover of Aperture’s Spring 2013 issue (#210) is a detail from an untitled 2012 photograph by Cologne- and Amsterdam-based artist Christopher Williams. The image is part of a new series of pictures he has taken of an East German Exakta camera, notable for the placement of shutter release, aperture dials, and other important components on the left-hand side of the camera body.

The issue’s theme is “Hello Photography,” and offers articles on a broad selection of concerns for photography now. Beginning today, each week we will offer an exclusive insight into the design, production, and contents of the newly reconceived and redesigned Aperture. Stay tuned! The magazine launches on February 26.

The Brighton Photo Biennial 2012

By Jason Oddy

Corinne Silva, Plastic Mountain I, plastic recycling plant, from Badlands, 2008–11.

© Corinne Silva

To Londoners, the seaside town of Brighton is synonymous with crowds, fun-fair rides, and ice cream. Close enough for a day trip, the very idea of it shimmers carefree. On the train there, perusing the brochure for the Brighton Photography Biennial, I’m reminded that away from the beach and the jauntiness it is also an enclave of progressive values, counterculture, and dissent.

Addressing some of the most pressing issues of the past few years, Agents of Change: Photography and the Politics of Space appears to be a biennial at the right time in the right place. Its title suggests the belief that photography can make a difference. Ranging over the financial crisis, street-level poverty, the Arab Spring, the domestic war on terror, the rich-poor divide, the effects of globalization, drone warfare, and Occupy and other protest movements, a total of fourteen shows consider how the camera, rather than just being an instrument of mediation, might sometimes take hold of reality instead.

The exhibition Uneven Development pairs the work of two photographers who examine ways the division of space creates and reinforces inequalities. In his extended photo essay Cairo Divided, published in the Guardian in 2011, Jason Larkin documents the construction of new gated suburbs around Cairo. Distributed in Egypt as a free newspaper, Larkin’s work, accompanied by the Guardian’s Jack Shenker’s text, is a first-rate example of nuanced, deep-digging journalism.

For her series Imported Landscapes, Corinne Silva pasted her own photographs of Moroccan landscapes across billboards in southern Spain. By compressing the landscapes of these neighbouring countries into a single frame, Silva forces attention onto their interwoven histories, economies, and geographies. The theme of shifting boundaries brought on by globalization runs through her conceptually beguiling work. Making unashamed use of the local Mediterranean light, her pictures are compositionally flawless. Next to them, Larkin’s journalistic aesthetic looks almost out of place.

Above: Trevor Paglen, Large Hangars and Fuel Storage; Tonopah Test Range, NV; Distance approx.18 miles; 10:44 am, 2005. Below: Trevor Paglen, KEYHOLE 12-3 (IMPROVED CRYSTAL) Optical Reconnaissance Satellite Near Scorpio (USA 129), 2007 © Trevor Paglen

A short walk away, The Beautiful Horizon is a photographic collaboration between artists Julian Germain, Patricia Azevedo, Murilo Godoy, and a group of young Brazilian street people. The results, adroitly presented in a church-turned-gallery, provide an unexpurgated glimpse into the lives of some of the planet’s most disadvantaged citizens. The project, like many others, attempts to give a voice to the dispossessed, though whether, as the catalogue claims, “the project demonstrates how photography can intervene in the urban landscape” remains open to question. True to the spirit of the biennial, The Beautiful Horizon is predicated on a Panglossian faith in photography: a hope that it can make things better. For without hope, what remains?

Perhaps the answer, if there is one, can be found in the work of Trevor Paglen, an artist who specializes in what has been termed counter-surveillance. Using astronomical lenses with focal lengths of up to 7,000 mm, he photographs secret U.S. military installations as far as sixty-five miles away. The grainy pictures show Predator drones skulking in their hangars. In perhaps the most arresting image the tiny silhouette of a drone is pinned, insect-like, against the clouds. For his series The Other Night Sky, Paglen tracked classified military intelligence satellites as they passed overhead. The results, reminiscent of photographs of outer space, are as beautiful as they are chilling.

Returning power’s gaze is a theme that runs throughout the biennial. Edmund Clark’s Control Order House is another project in which photography becomes a battle zone. After months spent negotiating with the United Kingdom’s Home Office, Clark was finally allowed to take pictures of the interior of a house where a terrorist, suspect subject to a Control Order, was living. Rather than being arrested, a “controlled person” is obliged to live in government-designated accommodations and must follow a strict set of rules. Similarly, the photographs Clark was permitted to take reveal nothing about either the suspect or the house’s true identity. The resulting images are bland—impersonal rooms with no distinguishing features—visual counterparts of the existence that controlled persons are obliged to lead. Compulsory immersion in English suburban life may be one way of dampening the fires of jihadism, but consider that alongside this forced relocation you also live under constant surveillance. With cameras possibly everywhere, hemmed in by myriad regulations, the controlled person must internalize authority’s gaze, self-correcting at every step.

Above Images: Omer Fast, from 5000 Feet is the Best, digital film, 30 minute loop, stills by Yonn Thomas, 2011. © Omer Fast

While such an exercise of power might be far-reaching, it is Omer Fast’s film about the effects of drone warfare that truly demonstrates the camera’s full force. If we can all imagine how drone strikes impact upon their targets, then Five Thousand Feet Is Best also focuses on the drones’ operator-pilots, splicing together restaged and documentary interviews alongside fictionalized scenes. In voiceover narration, we hear an ex-pilot complain how after his first “kill” he began to suffer from “virtual stress,” bad dreams and loss of sleep, brought on not only by the disconnection that characterizes such remote assassinations, but perhaps also by the overload of grisly information furnished by the powerful cameras on the drones. “What it does is lock on those pixels,” he says, talking of a target, seemingly unaware that a job like his would probably lock him into the same pixel zone. An update of Michael Powell’s 1960 film Peeping Tom, Fast’s Five Thousand Feet Is Best exposes the camera as a weapon. Nowadays it’s hard to escape the feeling that we’re all caught in the crosshairs of this irresistible image world.

––

Jason Oddy is a photographer and writer. His exhibition A Is for will be at the James Hockey Gallery, Farnham, England from February 1–March 13, 2013. His book Notes From The Desert will be published in France by Grasset later in 2013.

––

Corinne Silva, Plastic Mountain I, plastic recycling plant, from Badlands, 2008–2011.

© Corinne Silva

Trevor Paglen, Large Hangars and Fuel Storage; Tonopah Test Range, NV; Distance approx.18 miles; 10:44 am

C-type print, 30” x 36”, 2005.

Courtesy of Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne, and Altman Siegel Gallery, San Francisco,

© Trevor Paglen

KEYHOLE 12-3 (IMPROVED CRYSTAL) Optical Reconnaissance Satellite Near Scorpio (USA 129), 2007

C-Print 60 x 48 in. (152,4 x 121,9 cm)

Courtesy of Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne, and Altman Siegel Gallery, San Francisco,

© Trevor Paglen

Omer Fast, from 5000 Feet is the Best, digital film, 30 minute loop, still by Yonn Thomas, 2011.

Courtesy of the artist, Arratia, Beer, Berlin, and gb agency, Paris, © Omer Fast

Omer Fast, 5000 Feet is the Best, digital film, 30 minute loop, still by Yonn Thomas, 2011.

Courtesy of the artist, Arratia, Beer, Berlin, and gb agency, Paris, © Omer Fast

Omer Fast, 5000 Feet is the Best, digital film, 30 minute loop, still by Yonn Thomas, 2011.

Courtesy of the artist, Arratia, Beer, Berlin, and gb agency, Paris, © Omer Fast

January 7, 2013

Call for Entries: Aperture Portfolio Prize

Artists are invited to enter the Aperture Portfolio Prize 2013 contest, an international photography competition.

Through the Aperture Portfolio Prize, we aim to identify trends in contemporary photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition. When choosing the first-prize winner and runners-up, our editorial and curatorial staff look for innovative bodies of work that haven’t been widely seen in major publications or exhibition venues. The first-prize winner receives $3,000 and has his or her work exhibited at Aperture Gallery. The winner and up to five runners-up are featured on Aperture’s website, accompanied by a brief statement written by Aperture’s staff. Previous winners and runners-up include Sarah Palmer, Thibault Brunet, David Favrod, Alexander Gronsky, and Andrew McConnell.

Entries for the 2013 Aperture Portfolio Prize can be submitted from Monday, January 7, through Thursday, February 28, at 12:00 noon EDT, at callforentry.org. The winners and runners-up will be announced in July. For specific details, see the Guidelines and FAQs pages.

Please stay tuned for more details about our other competition, the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation Book Prize, to be announced in April 2013.

The Bomb (Also) is a Flower, 2010

The Bomb (Also) is a Flower, 2010$700.00

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers