Aperture's Blog, page 202

February 26, 2013

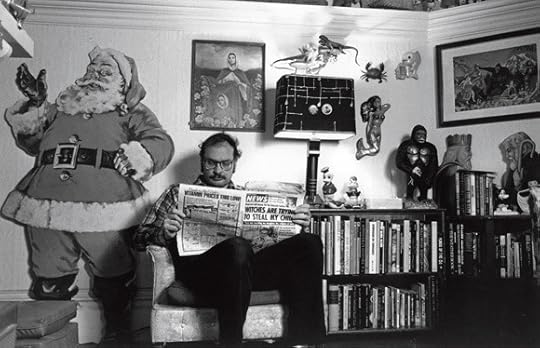

Dispatches: Jason Fulford on San Francisco

Jason Fulford, San Francisco, 2012 © Jason Fulford

It’s been a year now since I drove from Scranton, Pennsylvania, to San Francisco and let the air out of the tires. My wife was given a yearlong fellowship here to work for an idealistic nonprofit that creates new technology for city governments. I tagged along, excited to wander the same streets as Henry Wessel. We arrived in October—still summer in San Francisco—to a warm reception. Frish Brandt from the Fraenkel Gallery, Joseph del Pesco from the Kadist Art Foundation, and Chris McCall from Pier 24 introduced themselves as the welcoming committee.

On week two, I received an invitation from Richard Misrach to join a photo-study group. He was starting a new incarnation of an old idea, and explained it like this: “Since the 1970s I have held ‘salons’ … I reach out to a handful of local artists, we generally meet at my studio, or rotate to the other studios, everyone contributes to a potluck meal, we look at work, share readings, and sometimes create collective projects. There’s no set agenda—it evolves democratically. It’s an old-school model, for sure, but I highly recommend it.” The group focuses on one topic each meeting— ethical problems related to shooting documentary portraits, for example—and discusses it from different angles. There is sometimes friction, and often follow-up over email. It’s a sort of spirited continuing-ed class that ends up resonating in the background between meetings.

Misrach’s salon is one small slice of a large photography scene here. In the past twelve months, I’ve made my way from dinner table to dinner table on both sides of San Francisco Bay. I’ve found that there are three generations of local photographers that feel connected, like an extended family.

One figure who is brought up at nearly every dinner is Larry Sultan, whose work tended to comment on community and family. Larry passed away three years ago, but his presence is still felt. On top of his career as a photographer, he was known for his generosity as a teacher. I asked artist Dru Donovan, who worked at his studio for a time, what made Larry so special. “He mixed wisdom with doubt,” she said, “and critical intellect with vulnerability and honesty.” Dru also told me that Sultan insisted on regular “study halls” during the workday: “For about a half hour or so, he and I would drop everything work-related and pick up something to read. Study hall was founded because life is rich, full, and for the making and participating in.”

Communities here are shaped by those who are missing as well as by those who are present. Another important influence, who died last year, was the filmmaker George Kuchar. George inspired his students as much as Larry did, though using very different teaching methods. A professor at the San Francisco Art Institute, he threw his students into the chaotic productions of his own insane films. Artist and curator Jordan Stein fondly recalls Kuchar’s “AC/DC Psychotronic Teleplays” class, during which he was cast in a movie with a script that was “basically one enormously unsavory food pun.”

George Kuchar, 1960′s. Photographer unknown. Photofest.

Sultan and Kuchar both fostered a real sense of community as teachers and mentors. If you attend any of the lectures sponsored by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and Pier 24, you’re likely to run into some of the working photographers in town. Many of them also teach at SFAI and at the California College of the Arts.

Jim Goldberg studied under Sultan decades ago, and now teaches at CCA. His studio is located above one of the cavernous Mission Street thrift stores (where I imagine Kuchar’s students hunted for props). Talented photographers pass through, and often end up working for Jim: Lindsey White and Eric William Carroll are two who have put in time at the Goldberg studio, and are now making smart and thoughtful work.

The photographic output in the San Francisco community varies wildly—analog, cameraless darkroom experiments; traditional social documentary; conceptual installationbased work; and giant homemade cameras. More than any unifying sensibility or aesthetic, there is a strong network of support between photographers. And—maybe this is a California thing—the support is heavy on positivity, light on criticism.

The diversity of styles is seen in the number of artist-run photobook presses in the Bay Area. Each has its own sensibility and reaches out to a different audience. Paul Schiek publishes TBW Books from an overgrown industrial pier in Oakland. He hires local printers to produce his Subscription series, which features a mix of local photographers (Abner Nolan, Todd Hido, Katy Grannan) and out-of-towners (Mark Steinmetz, Elaine Stocki, Alec Soth). Paul generally gives artists free reign, within a set of restrictions—page count and trim size. Nick Haymes, a recent transplant via London and New York, is publishing a mix of international work under his imprint, Little Big Man. Many of his books bring to light decades-old pictures from photographers’ archives—Surf Riot by Nick Waplington documents a 1986 beach riot; To the Past by Nobuyoshi Araki is a sort of photographic diary going back to 1979; and Kitajima Keizo’s 1991 USSR is a collection of pictures that has been aging in storage like whiskey. On the lighter side, Ray Potes, a.k.a. Hamburger Eyes, pumps out black-and white ’zines and “mega-zines” (more than one hundred) with energy and humor, filled with work from a collective of local photographers.

Nick Waplington, Surf Riot, 1986 © Nick Waplington, courtesy Little Big Man

Regionalism seems to be on the rise in the United States, and I think the trend may have started in San Francisco. Many of the restaurants have long supported local farms. Composting is mandatory. Tech companies open up workshops and lectures to the public (including their competitors). A friend described the local cuisine this way, and I think it’s an astute metaphor for photography: yes, it’s about the way it looks and tastes, but it’s more about the way it makes you feel, once it’s inside your body.

Jason Fulford is a photographer and cofounder of the nonprofit J&L Books. He is a contributing editor to Blind Spot magazine and a frequent lecturer at universities.

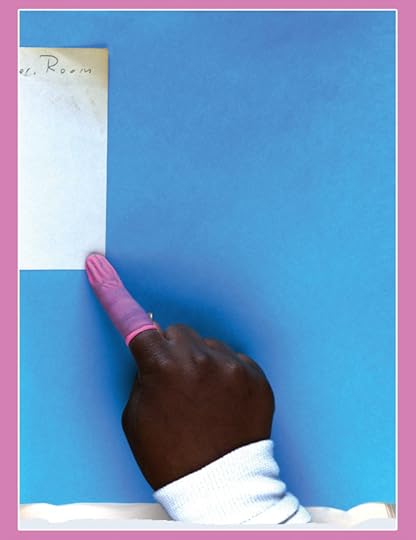

Andrew Norman Wilson with Laurel Ptak: ScanOps

Laurel Ptak: Tell us about your recent photographic series ScanOps. How did the project develop?

Andrew Norman Wilson: I have been collecting “anomalies” from Google Books for a couple of years: images in which software distortions, the imaging site, or the hands of the Google employees doing the scanning are visible. The fingers and software distortions obscure the information in the books—which complicates the notion of universally accessible knowledge.

Andrew Norman Wilson, The Inland Printer-164, 2012

LP: Where does the title ScanOps come from?

ANW: It’s the departmental name for Google’s onsite book-scanning operations at their headquarters in Mountain View, California. I’m pretty sure the name “ScanOps” was never public—I found it searching around Google’s Intranet.

In 2011 I made a video called Workers Leaving the Googleplex. I worked for a year in 2007–8 on Google’s campus. While there, I wore a red badge—like most other contracted employees. The fulltime Google employees wore white badges, and interns wore green badges. In the video, these “classes” of employees are seen passing by, entering and exiting buildings at the Googleplex. Some of them ride Google loaner bikes; some are seen getting into a Google limo shuttle headed toward San Francisco. Some of them are leaving work, some may be walking to another building to exercise in one of the Google gyms or pick up their laundry, some may be just arriving at the Google campus to eat a free meal from one of the twenty gourmet cafés after a day of working at home.

But from my office, I noticed a fourth class of workers operating in the building next to where I worked; they wore yellow badges. They stood out on the Google campus because of their races—many are people of color—and their attire, which was not that of the usual tech worker. In the Workers Leaving video, the yellow-badge employees are seen leaving the one building they are allowed access to. They all leave at the same time every day—2:15 pm—because their superiors have asked them to. It is a separate departure time from the other workers, so their exit is its own “movement.”

LP: Can you talk about the films by the Lumière brothers and Harun Farocki that influenced you in putting your film together?

ANW: In Farocki’s 1995 film Workers Leaving the Factory, he discusses how in the Lumière brothers’ film, also called Workers Leaving the Factory (1895), the primary aim was to represent motion; in particular to create an image of a work force in motion, organized by the work structure (a temporal construct), the factory gates (a spatial grouping), and the filmmakers’ choreography of this time-space relationship. But of course moving images don’t only represent movement, they can also grasp for concepts. This is what Farocki’s film is about—how signs and symbols are taken from reality, as if “the world itself wanted to tell us something.” He uses a particular motif in film history—that of workers leaving the factory—to interpret what the world is telling us.

The Lumières’ Workers and my own each present the social and technological conditions of their time. Both represent movement—but in my representation of movement, we see clearly defined tiers of workers … so the movement is “scripted” by what class they are in.

LP: ScanOps continues to follow these Google Books workers in another way.

ANW: While I was working as a video editor and videographer at Google, I started to document and talk to the ScanOps employees—but was fired rather quickly. It was intended to be a larger project, but it ended up being quite simple and limited because I wasn’t left with much more than my footage and my account of what happened.

At some point later I heard about the scanning mistakes and accidents that occur in Google’s book-scanning operations and decided to look closer. The work of the ScanOps employees is an interesting hybrid—it is a labor of digitizing informational materials that requires no cognitive involvement with the content of those materials. The labor process is quite Fordist—press button, turn page, repeat.

The workers compose part of the photographic apparatus, which in a broad sense includes not only the machinery but the social systems in which photography operates. The anonymous workers, Google founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page, the pink “finger condoms,” infrared cameras, the auto-correction software, the capital required to fund the project, the ink on my rag-paper prints, me—we’re all part of it.

LP: Would you discuss the thinking process behind your photographic work?

ANW: Each stop along the way in my work involves machines and humans. I like the idea that my work is part of a living, expanding process, and I am trying to underscore the fact that we are all complicit in and responsible for our social and technological arrangements. I want to dispel any notion that we are passively, subjectively impacted by foreign objects and systems.

LP: Take us through the steps in your work’s production, the logic of each decision in ScanOps.

ANW: Production starts before I get involved. The books are photographed at the libraries where they are stored, or are shipped to the Google Books facilities to be photographed. Software auto-corrects and converts the images and uploads them online. I browse for images that fulfill my criteria, download them, convert the pages I want, and edit out the Google watermark. There’s no resizing or additional editing.

Next I have them inkjet printed to scale, they are mounted and sent to the framers, who make a custom frame for each print. Then I bring the prints to Home Depot, and pick a color from each print for them to match. They mix up the paint in that color and I bring everything to an autobody shop, where the frames are sprayed in their respective colors. It’s a whole production line.

I’m choosing materials and production processes—some of them subcontracted to other people—that allow the materiality of the work to be emphasized. There are also preexisting conditions that communicate that for me, and I let them alone—for instance, leaving the images at their original size keeps them in direct correlation to the printed matter they came from. In a gallery or on the page of a magazine each work occupies a unique volume of space, and so when put together their spatial/sculptural qualities are emphasized.

LP: It’s compelling to think of ScanOps as a kind of update to the tradition of documentary photography, but for the online image.

Andrew Norman Wilson, The Inland Printer-152, 2012

ANW: I do look toward the work of certain documentary photographers—Dorothea Lange, Jacob Riis, Lewis Hine, and so on—whose socially engaged, journalistic photography represents marginalized populations, and in particular their labor.

In addition to the work engaging photography’s materiality and an interest in the abstraction that the anomalies can present, I like to think of each image—whether it contains accidents or not—as a view of the world. They reveal traces of the humans and technology that produced them.

LP: We most often encounter digital recordings of books as scans, but you refer to these as “photographs”—why is that? Who are the photographers here?

ANW: Mass-market books can be sliced open and fed into scanners, but the books I’m looking at come from library collections and can’t be dismantled; they need to be photographed with a camera from above. The fingers we see in some of the images could mistakenly be called the photographers’ hands—but their actions have been dictated by superiors at Google, so really they are the camera operators. The photographers are Sergey Brin and Larry Page, who proposed the digitization of all the world’s books when Google was just a fledgling startup. Because the copying of an entire book violates copyright, the photographers have been faced with lawsuits from the Authors’ Guild, the Association of American Publishers, and more.

Google is in the sole possession of the means of search and distribution for most of the books published in the United States in the twentieth century. For the first time, elements of public library collections are offered for sale through a private contractor, with additional revenue coming in from the ad space for sale next to the online books.

Everyone who uses Gmail, Google Docs, Google Books, Blogger, YouTube, etc. becomes a knowledge worker for the company. We’re all performing freelance data entry. Where knowledge is perceived as a public good, Google gathers its income from the exchange of information and knowledge, creating additional value in this process. Google, as we know it and use it, is a factory.

—

Top image: Andrew Norman Wilson, The Rainbow Girl-9, 2012 (detail)

Andrew Norman Wilson lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. He is currently working on a ScanOps book to be published by Art Metropole, and lecturing on ScanOps and Workers Leaving the Googleplex in his Powerpoint performance Movement Materials and What We Can Do.

Laurel Ptak is a New York–based curator. With artist Marysia Lewandowska, she is currently co-editing a book titled Undoing Property, examining relationships among artistic practice, intellectual property, immaterial production, and political economy, to be published this year by Sternberg Press.

Nine Years, A Million Conceptual Miles – By Charlotte Cotton

It has been nine years since I wrote The Photograph as Contemporary Art (Thames & Hudson, 2004), my survey of photographic practice over the previous five years. The slow and cumulative battle to validate photography as contemporary art had long been won by the time we went to print. The market for photography as art—at the time this almost invariably meant Lightjet color prints laminated behind sheets of Plexiglas, at least 30 by 40 inches in size—was buoyant. With the final death throes of traditional editorial photography as a means to earn a living, there was a shift of emphasis in the realms of documentary photography and photojournalism, away from the pages of magazines and newspapers and into museums and galleries and the pages of photobooks. Few knew how digital capture or postproduction would impact independent and artistic photography. And I suspect that no one anticipated the extent to which digital dissemination would increase the number of independent photographers and the potential to self-publish. If anything, the schools of and growing market for contemporary art photography seemed content with digital photography mimicking its analog predecessors’ conventions and not particularly interested in deciphering what might be uniquely digital characteristics, in either its aesthetics or its channels of dissemination.

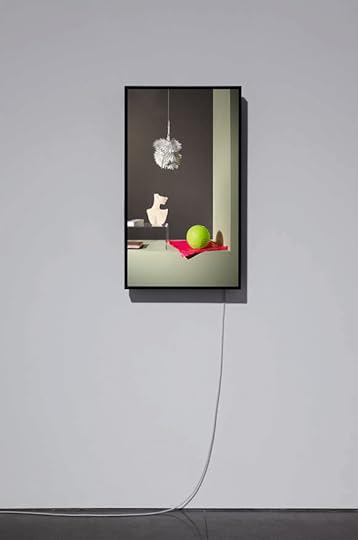

Owen Kidd, Canvas Leaves, Torso, and Lantern, August 2011, 2012. Installation photograph by Michael Underwood. Courtesy Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, New York

Watching these developments, I’ve oscillated between feeling we are on the cusp of seeing unimaginably brilliant, liberated, and different iterations of photographic ideas in a wholesale digital world and being worried that we may be marking the cynical end of a once-central visual medium that is now being put out to a niche pasture.

My own drama over this problematic cultural paradigm doesn’t stem from a sense of photographic practice per se becoming redundant in its capability for social and cultural awakening. Far from it. Instead, it comes from a genuine concern that the very mechanisms of the medium’s dissemination—publishing houses, museums, commercial galleries, and art schools—that could be seen as having won the good fight to legitimize photography as a contemporary art form with its own medium-specific history are becoming part of the problem. These structures, with their gamut of agendas, unwittingly risk placing a stranglehold upon the evolution of the medium.

It may be stating the obvious to say that no one person—indeed, no institutional matrix—is powerful enough to hold back the momentum of creative change or its full cluster of mitigating factors. The ecosystem of image making continues to evolve, and does not require the validation of art galleries and museums. What is at stake is how the mainstream instruments of “photography as culture” can deal with the arrival of the first wave of independent photographic practice that does not look like or model itself upon the separatist story of photography that institutions have already told.

I have worked as a curator of photography in museums for most of my professional life; perhaps I should be more generous than I feel toward the cultural organizations that have attempted to engage with the newly dominant forms of photography—such as citizen journalism, visual social media, photography as activism and social practice, and collective creativity. Perhaps there is a way to blend some contemporary photography into a seamless continuum of the museological story of the medium, a story that began in the 1840s. But in my own experience, museums’ engagement with contemporary photography—outside the increasingly narrow band of consciously, conventionally, unwaveringly “high art” photography—is littered with misunderstandings and meanings lost in translation, and has accomplished little to expand a cultural understanding of this beautifully complex medium.

Photography is, and has been since its conception, a fabulously broad church. Contemporary practice demonstrates that the medium can be a prompt, a process, a vehicle, a collective pursuit, and not just the physical end product of solitary artists’ endeavors. Addressing that multifarious terrain is a hefty challenge for most museums and galleries, and a genuinely impossible task for those who continue to believe photography is best sliced into monographic exhibitions and sometimes into classic genres and themes. (What other medium is still exhibited so regularly in those dreadfully tired categories “landscape,” “portraiture,” and “still life,” as per forty years ago?)

Of course it’s a tough economic moment for museums and nonprofit spaces to rethink both their remit and their mode of operation. It is chancy to change rather than to go into a holding pattern, doing what you have always done for whom you have always done it, but with much less money. It is no wonder that in recessionary times such as these, galleries and museums cling hard to the work and narratives of photographers with watertight authorship, blue-chip track records of collectability, and blatant signature styles, even though the glory days of such an approach seem to be over. This would be sad but fine if it weren’t for the fact that practically everything that surrounds mainstream cultural organizations engaged with photography has changed, and this, by extension, changes the meaning of even an unchanging enterprise.

Our attitudes to authorship, shifted massively by our common use of the Internet, confuse our understanding of where photography will fit in the cultural landscape of the future. Anyone invested in high-art photography (where authorship is king, where influences are conventionally hidden, and where reusing existing imagery is consciously acknowledged as appropriation) sees this intellectual-property amnesia of the age of the “digital native” as a problem, at least on the level of terminology. All photographic imagery circulating on the Internet is the raw material for millions of “unique” stories of (educators, hold your breath) “self-expression”: found illustrations that quasi-communicate millions of people’s homogenized experiences and emotions. The Internet does not adhere to the inherent, necessary asymmetry of high- versus low-art categorizations that we use in the cultural sector: in a banal sense, all photographs on the Web are orphans ready to be claimed.

We are not only a civilization of amateur photographers; we are amateur curators, editors, and publishers. Some of the new amateurs are pretty noble—like the citizen journalists who put in serious hours of work and comprehend so thoroughly the intelligent capacities of our pervasive image-led technologies. And just as this pro/am (professional/amateur) school of journalism seems to be a counterpoint to the ever-decreasing realm of independent news media, we at least have to think through the groundswell of pro/am photographic artists who self-publish, collectivize, and find their audiences themselves, knowing full well that the professional infrastructure for art photography is never going to accommodate them during their productive lifetimes.

And what really is the difference between a serious amateur who is disciplined enough to use his or her nonprofessional hours to create independent photography (subsidized by first and second jobs) and the economic reality for most artists who are not among the handful of well-known names whose practice is underwritten by sales? On an individual level, I’d guess the main difference is a debt of somewhere in the region of sixty to eighty thousand dollars, built up during the span of an MFA program. Of course there is a handsome number of MFA photography graduates who have made good use of their education to store up a degree of criticality and experience that will nourish them throughout their creative lives. But there is an underlying conservatism that graduates have to wrestle with when considering how such an expensive education will literally pay off. It’s a risk to propose new forms of photographic art to a market that took almost ten years to feel comfortable with the idea of pigment prints. And it is the same pressure for postgraduates entering curatorial work—except they have to deal with curating being a newly fashionable lifestyle choice (see J.Crew’s “curator pants” for starters).

I don’t think it’s good for anyone if the new professionals of curating distinguish themselves from pro/am lifestylers, stylists, picture editors, artist-curators, and even their more enlightened professional predecessors by aligning themselves with photographers who produce splendid, unmistakably “high-art” spectacles. It’s like a generation of photography curators not being allowed to wage their battle to expand the notion of photography as a subject and potentially to win new terrain within cultural discourses for the medium.

*

Still, within this mercurial climate, I see something magical beginning to happen: a critical mass of contemporary art photographers whose clarity and sentience to the image-making epoch in which we live transcend all the blockages I’ve outlined. It’s a critical mass rather than a grouping because, mercifully, the ways in which they open up the subject of photography are diverse. Some of these image creators have found their footing in the haptic and social era of photography; they make works that think through how new technologies feed into the analog-framed discourses of photography as contemporary art. Invariably these digital-native photographers experiment across platforms: the gallery context is one of several; there are also online formats, and traditional and e-publishing. This latest generation of practitioners is distinctly high-versus-low agnostic while being meticulous about the meaning and values of photographic language in its different contexts, and cognizant of the variance in the types of engagement that these different sites create with an audience.

Other contemporary art photographers that are giving cause for robust hope began their relationship with photography through analog thinking and processes, marveling at the prospect of photography as an expanding field while perhaps more acutely treasuring the sensory pleasure of traditional photographic prints for their pronounced craftsmanship and authorship. Contemporary art photographers are the only full-time creators of photography who labor over the production of photographic prints destined only for the spaces of art galleries and museums. Photography’s materials (straddling analog and digital technologies) have never been more readily understood by artists or audiences as a series of conscious choices.

At its most literal, contemporary art photography is beautifully dialogical. Photography is the central subject within photography as an artistic medium, an entity best understood in relation to a host of mitigating factors, from its quotidian cousins in social image-making to the elder statesmen of highbrow art—especially painting and sculpture but also installation arts, including video.

For instance, Carter Mull’s floor-based installation of scattered prints Connection (2011–12) offers a deeply visceral experience of photography that combines a heritage of conceptual art references with a very contemporary meditation upon the state of the mediated photographic image. Connection places us in a space that fuses the dissemination and production methods of photographic imagery. The installation takes into account the permeation of imagery on the pages of the declining empires of print media, and our promiscuous capturing of transitory visual experience via mobile devices—specifically the iPhone. Connection encourages us to take stock of both the plethora of contemporary imagery and its impact on our consciousness, while showing our disregard as we tread on its physical detritus. It is an experience that could only be so abstracted and pinpointed in the rarefied context of a contemporary art gallery and through the authorial voice of the artist.

The relationship between photography and sculpture has perhaps been the most imposing signature of contemporary photography of the twenty-first century so far. About a decade ago, Sara VanDerBeek made a significant contribution to the art-world celebration of photography’s materiality with gorgeous photographs of her handmade sculptures. With her recent installations (including her 2011–12 commission for the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles) she breaks important new ground. Every element of VanDerBeek’s Hammer installation was clearly an intricate web of finely crafted acts and artistic decisions that rendered a tangible sense of the photographic. Small, framed black-and-white photographs (a portrait, a still life, a lunar image) seemed pronounced in their material perfection; sculptural pieces incorporated found objects, including bird feathers and a beaded curtain. The elements on display prompted the curiosity of looking that has driven the history of observational photography. Each framing device, from the exterior walls of the installation to the sculptural frames and supports within the space, reiterated the construction of classical photographic vantage points.

Much of the production of digital video art by photographers in the past five years does not go beyond an explorative sketching out of ideas, but in some cases we are starting to see important artistic proposals for how the “photographic” can credibly be explored through video. Owen Kydd creates short, fixed-shot video works that are also meditations upon the notion of the photographic. In what he calls “durational photographs,” Kydd sets up a dynamic for the viewer to search in his thirty- or forty-second videos for the photographic moment, anticipating the single, decisive observation. We forget the distinction between our own looking (for a determined length of time, given the seamless looping of the video imagery) and the durational and endlessly repeating video recording of a now-past moment.

We also see a confident use of the photographic frame, holding and condensing an impossibly large amount of visual information. I enjoy the way Matt Lipps literally cuts and pastes imagery, principally from mid-twentieth-century magazines and books, and carefully creates sculptural photomontages. It is so unreconstructed of him! His most ambitious work so far is the six-panel Untitled (Horizon Archive) (2010), in which a huge cast of real-life and art-historical characters are lined up for an imaginary photo-call. With the theatrical use of lighting, Lipps re-animates these orphaned images into his own story construction—in a way that brings to mind the compiling and connecting of the best Tumblr “curators,” but with more gorgeous photographic drama.

Lipps’s work is not unconnected to the mesmerizing strangeness in the composite work of Daniel Gordon and also the videos of Brian Bress. The three share a knowing originality in the ways they physically rework the mass of image production, mediation, and crass default settings to create works that function in high-art settings. For me, this mode of taking the essence, rather than the aesthetic, of default lowbrow photographic imagery into the art world feels like the planting of intellectual incendiary devices that at some point are going to explode the conventional ideas of where photography can be positioned in contemporary art.

The manner in which future generations of image makers will configure the idea of photography as contemporary art can be as seemingly effortless and open to the happenstance of photographic observation as ever. Jason Evans’s recent installations, including the one at the 2012 Krakow Photomonth, set up a joyous binary dance between photography and sculpture by coupling sculptural arrangements of objects on plinths with photographic posters of still-life arrangements pinned to gallery walls. Evans’s photographs of lyrical still lifes are titled Pictures for Looking At (2007–11) and his plinth-based sculptural arrangements of mass-produced, handmade, and found objects are titled Sculptures for Photography (2012), delightfully inviting us to perceive these constructions as photographs just waiting to happen.

*

It is clear that we are a million conceptual miles from where we were even nine years ago—when there was a pernicious idea that photography had to adopt the values, traditions, and rhetoric of other art forms and simultaneously deny its own broad lexicon of dynamic and quotidian meaning in order to have credibility. I look at the work of photographers such as Artie Vierkant and Kate Steciw, as well as that of Asha Schechter and Lucas Blalock, for instance, and get a mighty rush of excitement about photography’s bright new future. I find myself struggling to find the words to discuss their work—though I am neither short of opinions nor inexperienced at looking at new photography. My stumbling block is this: for the first time in my professional life, I am seeing independent photography that doesn’t operate in a conventional art-photography way … and I don’t know how to position myself. It is beyond the discourse that I know, and I experience this as a really positive expectation for the field of photography as art. This is why I think that those of us who have a genuine vested interest in the future of photography as contemporary art should open our doors and just let this new life come in.

Charlotte Cotton is a curator and writer. Among the positions she has held are director of the Wallis Annenberg Department of Photographs at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and curator of photographs at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Cotton is the author of The Photograph as Contemporary Art (2004) and founder of Words Without Pictures (2008-9) and Eitherand.org (2012). Words Without Pictures was published as a print and eBook by Aperture in 2010.

February 25, 2013

101 Tragedies of Enrique Metinides February 20–April 20, 2013

Aperture 210, Spring 2013

February 22, 2013

Aperture Magazine Instagram Competition

Love the relaunched Aperture magazine?

Show us! We invite you to send us your portraits—of yourself, friends, or family members—showcasing a copy of the Spring 2013 issue of Aperture magazine for the chance to win* a one-year subscription to Aperture magazine.

Submit often! Share your portraits on Instagram and Twitter with the tag #myaperturemag now through April 2, 2013.

Participants may also e-mail submissions as a link or attachment to blog [at] aperture.org. Please include “My Aperture Mag” in the subject line.

*For additional information about the contest, see our Official Rules below.

—

No purchase necessary. A purchase will not increase your chances of winning.

1. Eligibility: The Aperture magazine “My Aperture Mag” Subscription Giveaway Contest (the “Contest”) is only open to legal residents of the United States who are at least thirteen (13) years old. Employees of Aperture magazine, its parent, subsidiaries, or affiliates, as well as the immediate family (spouse, parents, siblings, and children) and household members of each such employee, are not eligible to enter.

2. Sponsor: The Contest is sponsored by Aperture Foundation (the “Sponsor”), located at 547 West 27th Street, New York, N.Y. 10001. The Contest is in no way sponsored, endorsed, administered by, or associated with Instagram, Twitter, Facebook and/or any other social media website or platform on which it may appear. Any questions, comments, or complaints regarding the Contest should be directed to Sponsor.

3. Agreement to Official Rules: By entering the Contest, you indicate your full and unconditional agreement to, and acceptance of, (a) these Official Rules and (b) Sponsor’s decisions regarding the Contest, which are final and binding. Winning a prize is contingent upon fulfilling all requirements set forth herein.

4. How to Enter: To enter: (1) Take a portrait (of yourself, a friend, or family member) while displaying a copy of the Spring 2013 issue of Aperture magazine (#210); (2) upload your picture through your Instagram or Twitter account using the hashtag #myaperturemag. Only submissions posted between 9:00 a.m. ET on Friday, February 22, 2013, and 6:00 p.m. ET on Thursday, April 2, 2013 (the “Entry Period”), will be eligible. Sponsor’s computer is the official time-keeping device for the Contest.

5. Content Requirements: Your Entry must not: (a) violate any third party rights, including, but not limited to, copyrights, trademark rights, or rights of privacy and publicity; (b) contain defamatory statements; (c) include threats to any person, place, business, or group; (d) be obscene or indecent; (e) depict any risky behavior, as determined by Sponsor in its sole discretion; (f) contain any third party trademarks or logos; and (g) have been entered in any other contest or have been published or distributed in any other media. Sponsor reserves the right to refuse to post any Entry for any reason.

6. Entrant’s Warranties and Representations: By submitting an Entry, you warrant and represent that: (a) the Entry is an original work created solely by you for entry in the Contest; (b) you own all rights to the Entry; (c) to the extent the Entry depicts any individual or features the voice of any individual, you are the individual pictured and heard in the submission, or, alternatively, that you have obtained written permission from each person appearing in the Entry to grant the rights to Sponsor described in the “Sponsor’s Rights to Entries” section below, and can make written copies of such permissions available to Sponsor upon request; and (d) the Entry complies with all requirements of these Official Rules.

7. Sponsor’s Rights to Entries: By participating, you: (a) irrevocably grant Sponsor, its agents, licensees, and assigns the unconditional and perpetual (non-exclusive) right and permission to reproduce, encode, store, copy, transmit, publish, post, broadcast, display, publicly perform, adapt, modify, create derivative works of, exhibit, and otherwise use your Entry as-is or as-edited (with or without using your name) in any media throughout the world for any purpose, without limitation, and without additional review, compensation, or approval from you or any other party; (b) forever waive any rights of copyrights, trademark rights, privacy rights, and any other legal or moral rights that may preclude Sponsor’s use of your Entry, or require any further permission for Sponsor to use the Entry; and (c) agree not to instigate, support, maintain, or authorize any action, claim, or lawsuit against Sponsor on the grounds that any use of the Entry, or any derivative works, infringes any of your rights as creator of the Entry, including, without limitation, copyrights, trademark rights, and moral rights.

8. Selection of Potential Winners: After the Entry Period, the Sponsor will evaluate all Entries and select three (3) potential winners based on the following Judging Criteria: originality and creativity. If the Sponsor suspects any fraud, tampering, or any activity that the Sponsor believes may impair the integrity of the entry process, the Sponsor may, in its sole discretion, select an additional potential winner.

9. Notification and Requirements of Potential Winners: Sponsor will attempt to notify the potential winner within one (1) business day of the date of selection. Except where prohibited, a potential winner may be required to complete and return an affidavit of eligibility, a liability/publicity release, and a release in which he/she irrevocably assigns and transfers to Sponsor any and all usage rights, title, and interest in Entry, including, without limitation, all copyrights and trademark rights, and waives all moral rights in the Entry. If a potential winner is a minor, his/her parent or legal guardian will be required to sign the documents on his/her behalf. If a potential winner fails to sign and return these documents within the required time period, an alternate potential winner may be selected in his/her place according to the Judging Criteria. Only three (3) alternate potential winners may be contacted.

10. Prize: One (1) winner will be selected. The winner will receive a one-year subscription to Aperture magazine. The approximate retail value of the prize is $75.00. In the case that the winner is a current Aperture magazine subscriber, the current subscription will be extended one year. A winner is responsible for paying any applicable income taxes and any and all other costs and expenses not listed above. Any prize details not specified above will be determined by Sponsor in its sole discretion. A prize may not be transferred and must be accepted as awarded. You may not request cash or a substitute prize; however, Sponsor reserves the right to substitute a prize with another prize of equal or greater value if the prize is not available for any reason, as determined by Sponsor in its sole discretion.

11. General Conditions: In the event that the operation, security, or administration of the Contest is impaired in any way for any reason, including, but not limited to fraud, virus, or other technical problem, Sponsor may, in its sole discretion, either: (a) suspend the Contest to address the impairment and then resume the Contest in a manner that best conforms to the spirit of these Official Rules; or (b) award the prize(s) according to the Judging Criteria from among the eligible entries received up to the time of the impairment. Sponsor reserves the right in its sole discretion to disqualify any individual it finds to be tampering with the entry process or the operation of the Contest or to be acting in violation of these Official Rules or in an unsportsmanlike or disruptive manner. Any attempt by any person to undermine the legitimate operation of the Contest may be a violation of criminal and civil law, and, should such an attempt be made, Sponsor reserves the right to seek damages from any such person to the fullest extent permitted by law. Failure by Sponsor to enforce any term of these Official Rules shall not constitute a waiver of that provision. Proof of sending any communication to Sponsor by mail shall not be deemed proof of receipt of that communication by Sponsor. In the event of a dispute as to any online entry, the authorized account holder of the email address, Twitter Handle, or other user name used to enter will be deemed to be the participant. The Contest is subject to federal, state, and local laws and regulations and is void where prohibited.

12. Release and Limitations of Liability: By participating in the Contest, you agree to release and hold harmless Sponsor, Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, and/or any other social media website or platform on which the Contest may appear, their respective parent, subsidiaries, affiliates, and each of their respective officers, directors, employees, and agents (the “Released Parties”) from and against any claim or cause of action arising out of participation in the Contest or receipt or use of any prize, including, but not limited to: (a) unauthorized human intervention in the Contest; (b) technical errors related to computers, servers, providers, or telephone, or network lines; (c) printing errors; (d) lost, late, postage-due, misdirected, or undeliverable mail; (e) errors in the administration of the Contest or the processing of entries; or (f) injury or damage to persons or property which may be caused, directly or indirectly, in whole or in part, from entrant’s participation in the Contest or receipt or use of any prize. You further agree that in any cause of action, the Released Parties’ liability will be limited to the cost of entering and participating in the Contest, and in no event shall the Released Parties be liable for attorney’s fees. You waive the right to claim any damages whatsoever, including, but not limited to, punitive, consequential, direct, or indirect damages.

13. Privacy and Publicity: Any information you submit as part of the Contest is provided to the Sponsor, and not to Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, or any other social media site or platform on which the Contest may appear, and it will be used for purposes of this Contest and treated in accordance with Sponsor’s Privacy Policy. Except where prohibited, participation in the Contest constitutes an entrant’s consent to Sponsor’s use of his/her name, likeness, voice, opinions, biographical information, and state of residence for promotional purposes in any media without further payment or consideration.

14. Disputes: Except where prohibited, you agree that any and all disputes, claims and causes of action arising out of, or connected with, the Contest or any prize awarded shall be resolved individually, without resort to any form of class action, and exclusively by the appropriate court located in New York. All issues and questions concerning the construction, validity, interpretation and enforceability of these Official Rules, your rights and obligations, or the rights and obligations of Sponsor in connection with the Contest, shall be governed by, and construed in accordance with, the laws of New York, without giving effect to any choice of law or conflict of law rules (whether of New York or any other jurisdiction), which would cause the application of the laws of any jurisdiction other than New York.

15. Results: To request a winners list, send a self-addressed, stamped envelope to Aperture Foundation Social Media Department, 547 West 27th Street, 4th floor, New York, N.Y. 10001.

February 19, 2013

Editors’ Note from Spring 2013 Issue

What should a photography magazine be? This question propelled a long conversation at Aperture Foundation about how we can navigate the next chapter of photography’s evolution and make a vital contribution as a print publication. The new Aperture was created with two steady assumptions in mind: First, that in a time when photography is abundant on digital platforms, images in print—ink on paper—continue to offer a uniquely actual experience. Second, that a magazine can engage photography’s changing narrative—while remaining attentive to the medium’s history—through thoughtful, accessible writing.

For these reasons, the main section of the magazine is now divided into two parts, “Words” and “Pictures.” In each issue, these two will cohere around an inquiry into a field or topic: the “Words” section will feature the longer, more substantial textual contributions, as well as interviews; in “Pictures” the emphasis will be on individual artists’ projects and photo series, generally introduced by short statements. A2/SW/HK, our new art directors, have re-envisioned the magazine to capitalize on how this print publication can continue to assert itself as an object, through its tactile presence, dynamic typography, and high-quality reproductions—all housed in an elegant design geared toward both reading and viewing.

We thought it fitting to organize our relaunch issue around a broad set of concerns for photography today. To get started, we called upon a group of thinkers, curators, and photographers to consider language from Aperture’s original 1952 mission statement proposing that the magazine should serve as a platform to “comment on what goes on” and to “descry the new potentials” of the medium. Our title, Hello, Photography, is a reversal of Daido Moriyama’s 1972 title Bye Bye Photography, his book of blown-out, fractured photographs that seemed designed to thwart easy comprehension—an acknowledgment that the medium was shedding its skin, becoming something else. Today, it’s a truism to talk of photography being in flux. The definition of photography, always multivalent, charting a promiscuous course across disciplines and contexts, feels especially slippery now, and this has caused much recent consternation and reevaluation. This installment of the magazine does not seek to replicate such inquiries, but rather to begin with the premise that all bets are on for the medium.

In his essay on contemporary scholarship, photography historian Robin Kelsey notes that the central concern for the medium today may be the fact that it occupies two homes: a tangible, material world of objects and prints, and a digital world of files and servers. The conflicting characteristics between the two can be felt across the photographic contexts represented here, as contributors to the “Words” section grapple with a host of ideas: the mandates and expectations for institutions dedicated to photography; how we might rethink photography education to better reflect our image culture (and how this image culture, which fluidly flattens and divorces images from context, potentially alters their evidentiary capacity); the interplay, as well as the familiar conflicts, of digital and analog; how to establish a taxonomy of vernacular photography when image output has grown too voluminous to parse; and how it might be productive, from our current vantage shaped by technological innovation and antic image traffic, to revisit older ideas—like that of artistic freedom—which take on new shadings in the current terrain.

In “Pictures,” opening with a selection from Christopher Williams’s new series based on a manual for an East German camera (also featured on this issue’s cover), it is primarily the photographers who, through their own work, make the arguments. Williams’s images of hands manipulating an analog apparatus lead into a series of portfolios that address a diversity of topics, such as our media-saturated society, the medium’s history and mechanics, photography’s indexical relationship to the world, as well as new modes for producing documentary work.

Like Hello, Photography, future issues of Aperture will be organized around specific inquiries: we will engage with photography as an art form, as a social phenomenon, and as an elastic lexicon for creating and shaping ideas. Hence our new tagline: “Speaking the language of photography.” Some issues will be guest-edited; others will be produced offsite, through the prism of a specific city or institution. The two main sections will carry the principal investigation, whereas the front and back will feature a series of rotating columns, including “Studio Visit,” “Collectors,” “Redux,” “Dispatches,” “What Matters Now?” and our new closing page, “Object Lessons.” While we are required, for the first time in a decade, to raise the subscription and newsstand prices of the print edition, all of Aperture’s content is now accessible in the digital version of the magazine at a new, lower price. Print subscriptions will include access to the digital edition as well as our semiannual publication, The PhotoBook Review. The magazine will also be more closely integrated with Aperture Foundation’s live and online programming: the debates, ideas, and work published in print will be explored through events at the Aperture Gallery and other venues, as well as on our website.

For sixty years now, Aperture has charted the concepts and changes shaping photography’s evolving narrative. Minor White, the magazine’s founding editor, noted in an editorial of 1953, a moment when the photography world was much smaller: “Photography seems to be reevaluating itself these days—probably preparatory to taking off in a new direction.” The magazine has always had as its mandate a goal of serious disquisition on the state of the medium. The following pages introduce a range of vital questions with a view to animating—and reanimating—key ideas on photography. This lies at the heart of Aperture’s purpose as it moves in a new direction, the better to respond to the medium’s many new directions.

— The Editors

Ben Lowy: Camera-Phone Technology and Craft Weekend Workshop

February 14, 2013

Aperture’s 2013 Traveling Exhibitions

Aperture Gallery in New York City hosted the reGeneration 2 exhibition in early 2011. The show is scheduled to open at the Devos Art Museum in Marquette, Michigan, on February 22.

The Edge of Vision: Abstraction in Contemporary Photography

Louisiana Museum of Art and Science

January 16–April 14

On Thursday, February 28, the Louisiana Museum of Art and Science will host “Art After Hours: Photography at the Edge.” Louisiana State University assistant professor Kristine Thompson will guide visitors through The Edge of Vision, which was curated by Lyle Rexer, author of The Edge of Vision: The Rise of Abstraction in Photography (Aperture, 2009) and features abstract imagery in all forms. The Aperture gallery hosted The Edge of Vision exhibition in May 2009.

Chuck Close: A Couple Ways of Doing Something

Florida Museum of Photographic Arts, Tampa

February 7–March 31

An exhibition of work by Chuck Close, A Couple Ways of Doing Something features fifteen daguerrotypes of leading contemporary artists, including Andres Serrano and Cindy Sherman. Close’s daguerrotype prints are accompanied by Bob Holman’s witty and beautifully typset poetry.

The Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards

Visual Studies Workshop, Rochester, New York

February 15–March 31

Last year, Paris Photo and Aperture Foundation hosted the inaugural Paris Photo—Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards. This accompanying exhibition features the thirty outstanding books shortlisted for the First Photobook and Photobook of the Year prizes. Look out for City Diary (Volumes 1–3) by Anders Peterson (Steidl, 2012), which was selected as PhotoBook of the Year, and Concresco by David Galjaard (self-published, 2012), which won $10,000 in the First PhotoBook category.

reGeneration(2): Tomorrow’s Photographers Today

The DeVos Art Museum, Marquette, Michigan

February 25–April 7

reGeneration(2) will open at the DeVos Art Museum on February 25. The exhibition features a collection of work from the world’s best up-and-coming photographers. The Aperture Gallery showcased this exhibition January 2011.

Paul Strand: The Mexican Portfolio

Louisville Art Center, Louisville, Kentucky

March 15–May 12

The Mexican Portfolio, originally titled “Photographs of Mexico,” features twenty of Strand’s photogravure images depicting the people, landscapes, architecture, and objects he encountered in Mexico between 1932–1933. The photos are drawn from the collection of the Paul Strand Archive of Aperture Foundation.

The New York Times Magazine Photographs

Sala Gasco Art Contemporaneo, Santiago, Chile

April 15–May 31

The New York Times Magazine Photographs exhibition, which consists of 126 works by thirty-five artists, celebrates eclecticism in magazine photography—from photojournalism to fashion photography and portraiture. Curated by New York Times Magazine photo editor Kathy Ryan, the show features pieces by Lynsey Addario, Gregory Crewdson, Mitch Epstein, Nan Goldin, Annie Liebovitz, Mary Ellen Mark, Steve McCurry, and more.

The Edge of Vision

The Edge of Vision

$49.95

A Couple of Ways of Doing Something

A Couple of Ways of Doing Something

$50.00

Paul Strand in Mexico Limited-Edition Box Set

Paul Strand in Mexico Limited-Edition Box Set

$2,000.00

reGeneration 2

reGeneration 2

$39.95

The New York Times Magazine Photographs

The New York Times Magazine Photographs

$75.00

Paul Strand in Mexico

Paul Strand in Mexico

$75.00

February 12, 2013

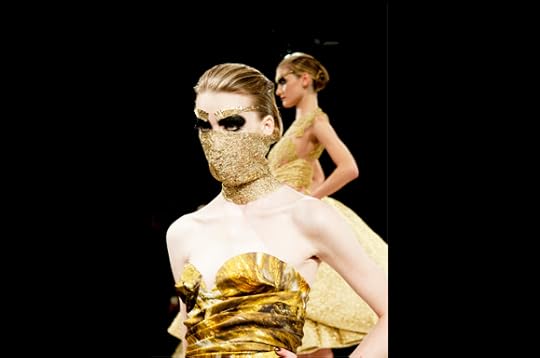

Aperture at New York Fashion Week

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture magazine visited the tents at Mercedes Benz Fashion Week for last Saturday’s presentation of the Rafael Cennamo Fall 2013 collection. Presentation attendees went home with special Aperture at Sixty totes containing advance issues of Aperture magazine #210.

Still waiting on yours? Stay tuned. There are just two weeks until Aperture magazine’s Spring 2013 issue, “Hello, Photography,” hits newsstands and reaches current subscribers.

Not yet an Aperture magazine subscriber? Subscribe today.

All images courtesy Rodin Hamidi.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers