Aperture's Blog, page 200

April 1, 2013

Joel Meyerowitz Reads from “The Gravity of Time”

After a lifetime of working on a series of “collective portraits” in far-flung places such as Mexico; Ghana; Italy; Tir a’Mhurain, Scotland; and his adoptive country, France, an aging Paul Strand decided to concentrate on still lifes and the stony beauty of his own garden at Orgeval, France, as a site in which to distill his discoveries as a photographer. The work that constitutes Paul Strand’s The Garden at Orgeval (Aperture, 2012) is marked by close and careful study of the forms and patterns within nature. While the images bear the same directness and precise vision that is quintessentially Strand, the work also reflects a growing metaphorical turn.

Here, renowned photographer Joel Meyerowitz reads from “The Gravity of Time,” a personal essay included in Paul Strand: The Garden at Orgeval, in which the photographer addresses his first encounters with Strand’s work, returning to nature as an enduring subject, and growing old.

—

Aperture published Paul Strand: The Garden at Orgeval in fall 2012. Paul Strand: The Garden at Orgeval

Paul Strand: The Garden at Orgeval

$45.00

Joel Meyerowitz Reads from The Gravity of Time

After a lifetime of working on a series of “collective portraits” in far-flung places such as Mexico; Ghana; Italy; Tir a’Mhurain, Scotland; and his adoptive country, France, an aging Paul Strand decided to concentrate on still lifes and the stony beauty of his own garden at Orgeval, France, as a site in which to distill his discoveries as a photographer. The work that constitutes Paul Strand’s The Garden at Orgeval (Aperture, 2012) is marked by close and careful study of the forms and patterns within nature. While the images bear the same directness and precise vision that is quintessentially Strand, the work also reflects a growing metaphorical turn.

Here, renowned photographer Joel Meyerowitz reads from “The Gravity of Time,” a personal essay included in Paul Strand: The Garden at Orgeval, in which the photographer addresses his first encounters with Strand’s work, returning to nature as an enduring subject, and growing old.

—

Aperture published Paul Strand: The Garden at Orgeval in fall 2012. Paul Strand: The Garden at Orgeval

Paul Strand: The Garden at Orgeval

$45.00

Video: Thinking in Color – A Conversation with Bill Armstrong and W.M. Hunt

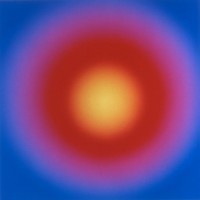

On March 18, 2013, acclaimed art photographer Bill Armstrong and collector, curator, and consultant W. M. Hunt presented “Thinking In Color,” a lively conversation on color photography. Taking inspiration from the book I Send You This Cadmium Red, which features correspondence between critic John Berger and artist John Christie, Hunt and Armstrong have initiated a dialogue about color in photography. Starting with Armstrong’s technical overview of color photography and its history, as well as Hunt’s observations about color and its empathic power, the exchange was a means for the longtime friends to challenge each other through their ideas.

Throughout their conversation at Aperture, Armstrong and Hunt offered thoughts about how color behaves, read from some of their written exchanges with each other, and took the audience on an unexpected and fresh journey through interpreting color in photographs.

Watch Part 2 of Thinking in Color: A Conversation with Bill Armstrong and W.M. Hunt

—

In 2011, Aperture published The Unseen Eye: Photographs from the Unconscious, a catalog of anti-portraiture amassed over the course of thirty years by W. M. Hunt, which includes works by masters such as Richard Avedon, Diane Arbus, Imogen Cunningham, William Klein, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Robert Frank.

Bill Armstrong’s work was featured on the cover of The Edge of Vision: The Rise of Abstraction in Photography (Aperture, 2009), author Lyle Rexer’s examination of abstraction at pivotal moments in photography.

Related article: Interview with Bill Armstrong

The Edge of Vision

The Edge of Vision

$49.95

The Edge of Vision Limited-Edition Portfolio

The Edge of Vision Limited-Edition Portfolio

$3,000.00

The Unseen Eye

The Unseen Eye

$75.00

March 29, 2013

Video: Hank Willis Thomas Artist Talk

On March 12, 2013, Aperture Foundation, in collaboration with the School of Art, Media, and Technology at Parsons the New School for Design, was pleased to present an artist talk with Hank Willis Thomas, a photo-conceptual artist working with themes related to identity, history, and popular culture. Appropriation and juxtaposition are two of many strategies with which Thomas orchestrates his interdisciplinary practice. In this video excerpt, Thomas discusses his series Branded (2011), which adopts a commercial vernacular to decry the commodification of African-Americans, both in contemporary sports and in the historical slave trade. A basketball player dunks into a noose, for example, or a Nike swoosh is branded onto a man’s head. Thomas’s images confront our difficult history through the universal legibility of advertising.

In Part 2, Thomas discusses his series Unbranded (2008), which uses advertisements lifted from the pages African-American-interest magazines; Thomas subtly reworks them, removing key text, logos, and/or products. The skeletal remains betray immediately the subliminal prejudice common throughout consumer culture.

—

In 2008 Aperture published Pitch Blackness, Hank Willis Thomas’s first monograph, which includes selections from his series Unbranded (2008), and several others.

Pitch Blackness

Pitch Blackness$35.00

On the Edge

Willie Doherty, Without Trace (Hidden), 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Peter Kilchmann, Zurich.

Willie Doherty, Without Trace (Into Thin Air), 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Peter Kilchmann, Zurich.

Willie Doherty, Without Traces. Installation view at Peter Kilchmann, Zurich. Courtesy of the artist and Peter Kilchmann, Zurich.

Willie Doherty, Without Trace (Between), 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Peter Kilchmann, Zurich.

The eleven photographs in the first room of Willie Doherty’s exhibition Without Trace seem both strangely immediate and familiar. They are all views of Zurich’s snow-covered outskirts in winter, the season that has just passed. They were taken on several visits to Zurich that Doherty undertook in recent months, an unusual move for an artist whose work has mostly focused on his native Northern Ireland. And although locals will easily recognize some locations, in particular those taken near the two rivers that run through the city, the large-format prints also look like they could have been taken anywhere in continental Europe. The peripheral places they show seem generic and anonymous—the snow-covered bank of river, concrete modernist buildings, a highway overpass in the woods, a panoramic view of the city on a grey day, dish antennas next to some modular temporary housing. The sky, save for one image, is gray, the light even and fallow. The snow eliminates details and colors, making the sites even more indeterminate. The strict composition of the photographs, often emphasizing a central perspective, underlines their severity. This seems to be a documentary series about the margins of the city where the built environment and nature intersect, often in a jarring contrast.

The wall-size video projection in the second room cunningly transforms this first impression. The video includes views similar to those in the photographs, yet the temporality of the moving images makes the sites appear more still, more forlorn. A female voice with strong foreign accent, seemingly Eastern European, tells the story of a man who had decided to spend a winter in Zurich. It’s not the photographer, as the viewer might have surmised, but instead a construction worker who has disappeared without any trace on the morning of December 12. A number of notebooks found in his apartment indicate that he felt increasingly isolated in the city. The narrator intones, “He had given up his construction job and spent his days wandering,” and he seems to have spent most of his time in places like those shown in the photographs and the video. An increasing sense of paranoia and dread had gripped him. He had sensed that the city harbored dreadful secrets, and only the rivers and the snow offered him solace. One day, he simply disappeared. The video ends with views of a frozen lake in the woods, while the woman relates that she dreamt “last night” that his corpse was lying in a frozen lake, waiting to be uncovered by the spring sun.

Willie Doherty, Without Traces, 2013. Installation view at Peter Kilchmann, Zurich. Courtesy of the artist and Peter Kilchmann, Zurich.

Doherty used a similar combination of landscape views and a voice-over narration in his video Secretion (2012), presented last summer at Documenta 13. It showed decrepit industrial landscapes near Kassel, while the voice-over told the similarly Poe-like story of a former concentration-camp warden who is killed, some years after World War II, by the seepage of human remains into the drinking water, destroying his body in the form of fungal spores. Both works examine the traces of the past harbored by industrial landscapes, and the alienation they induce. The photographs in Without Traces add yet another layer of complexity to Doherty’s dense docu-fictions. At the outset, they appear to be rather straight-on documentary images. Seeing them a second time, after encountering the video projection, they are imbued with the construction worker’s narrative. They appear to show Doherty’s retracing of the construction worker’s fatal stay in Zurich. Indeed, these might be the photographs the anonymous worker would have taken himself. Doherty’s adroit manipulation of our perception points to the inherent malleability of photographic images whose content is easily twisted by additional information. A paranoia similar to the one experienced by the story’s construction worker begins to haunt the viewer, who acutely experiences how easily she may be manipulated. The images are indeed not what they seem—just like the city that refuses to yield its dreadful secrets.

Martin Jaeggi is an independent writer and curator. He writes frequently about photography and contemporary art and teaches in the photography department of the Zurich University of the Arts.

Willie Doherty’s exhibition remains on view at Peter Kilchmann, Zurich, until April 13.

March 27, 2013

Thomas Ruff: photograms and ma.r.s. at David Zwirner

Photograms (detail) © Thomas Ruff, Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London

Thomas Ruff is among the most important international photographers to emerge in the last twenty years, and one of the most enigmatic and prolific of Bernd and Hilla Becher’s former students, a group that includes Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth, Candida Höfer, and Axel Hutte. Known for employing a range of techniques in his photographic work—spanning analog and digital exposures, computer-generated imagery, appropriation and manipulation—Ruff’s work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at prominent venues internationally, most recently in 2012 with a comprehensive large-scale survey presented at the Haus der Kunst in Munich.

Thomas Ruff: photograms and ma.r.s., on view March 28–April 27, 2013, at David Zwirner Gallery, will feature the world debut of Ruff’s new series, photograms, a body of work depicting abstract shapes, lines, and spirals in seemingly random formations with varying degrees of transparency and illumination. Reminiscent of 1920s-era experiments in camera-less photography, Ruff’s “photograms” derive from a virtual darkroom built by a custom-made software program. This new work will be presented alongside his ongoing series, ma.r.s., in which Ruff transforms black-and-white satellite photographs of the surface of Mars, taken by high-resolution cameras aboard NASA spacecraft, with interjections of saturated color.

Thomas Ruff: photograms and ma.r.s.

March 28–April 27, 2013

David Zwirner Gallery, New York

—

In 2009, Aperture released the first monograph dedicated exclusively to the publication of Ruff’s remarkable series JPEGS (completed in 2007), in which he explores the distribution and reception of images in the digital age.

JPEGS

JPEGS

$250.00

JPEGS

JPEGS

$85.00

The Dusseldorf School of Photography

The Dusseldorf School of Photography

$95.00

Luigi Ghirri: Kodachrome

When he published Kodachromes, Ghirri wrote a short exposé on his sources of inspiration, the notion of “deleted space,” and the things he is not interested in. That essay is reproduced below. It was included in Aperture’s 2008 volume It’s Beautiful Here, Isn’t It.

—Paula Kupfer

Luigi Ghirri, Bologna, 1973. © Estate of Luigi Ghirri, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Kodachrome: Introduction

I

In 1969 the newspapers published the photograph taken from the spaceship traveling to the moon. This was the first photograph of the entire Earth.

The image that man had pursued for centuries was presented for our view; it held within it all previous, incomplete images, all books that had been written, all signs, those that had been deciphered and those that had not. It was not only the image of the entire world, but the only image that contained all other images of the world: graffiti, frescoes, paintings, writings, photographs, books, films. It was at once the representation of the world and all representations of the world.

And yet this total vision, this re-description of everything, obviated the possibility of translating the total hieroglyph. The power of containing everything was annulled in the face of the impossibility of seeing everything all at once. The event and its representation, seeing and being contained, were presented—once again—to humanity as an insufficient response to the same old questions.

This possibility of total duplication, however, enabled us to glimpse the potential for deciphering the hieroglyph; we had the two poles of doubt and secular mystery: the image of the atom and the image of the world, finally looking at each other face to face. The space between the infinitely small and the infinitely large was filled by the infinitely complex: man and his life, nature.

The need for information or for knowledge emerges from these two extremes—fluctuating between the microscope and the telescope—to be able to translate and interpret reality or hieroglyph.

Luigi Ghirri, Paris, 1972. © Estate of Luigi Ghirri, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

II

My work emerges from the desire and the need to interpret and translate the sense of this sum of hieroglyphs—not only the easily identifiable reality of the reality that has highly symbolic content, but also thoughts, memories, imagination, and fantastical or alienated content.

For my purposes, photography is extraordinarily important, because of its specific characteristics. In photography, the deletion of the space that surrounds the framed portion is as important for me as what is represented: it is thanks to this deletion that the image takes on meaning, becoming measurable. The image continues, of course, in the visible realm of the deleted space, inviting us to see the rest of reality that is not represented.

This double aspect of representing and deleting not only evokes the absence of limits, excluding every idea of completeness of finitude, but shows us something that cannot be delimited: reality itself.

The possibility of seeing and penetrating the universe of reality instead passes through all representations and cultural models that are known and given to us as defined and decisive. Our relationship with reality and life is that same relationship that exists between the satellite image and the actual earth.

Thus photography, with its indeterminacy, becomes a privileged subject it allows us to move away from the symbolic nature of defined representations, and we can attribute to it a value of truth. The possibility of analysis in time and space of the signs that form reality (the entirety of which has always been elusive) thus allows photography, with its fragmentary nature, to be closer to what also cannot be delimited: physical existence.

So I am not interested in images and “decisive moments,” the analysis of language in and of itself, aesthetics, the concept of all-consuming idea, the emotion of the poet, the culled quotation, the search for a new aesthetic creed, the use of a style.

My duty is to see with clarity, and this is why I am interested in all possible functions—without separating any of them out, but taking them on as a whole, in order to be able, from time to time, to see the hieroglyphs I have encountered and make them recognizable.

Luigi Ghirri, Chartres, 1977. © Estate of Luigi Ghirri, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

III

The daily encounter with reality, the fictions, the surrogates, the ambiguous, poetic, or alienating aspects, all seem to preclude any way out of the labyrinth, the walls of which are ever more illusory… to the point at which we might merge with them.

The meaning that I am trying to render through my work is a verification of how it is still possible to desire and face a path of knowledge, to be able finally to distinguish the precise identity of man, things, life, from the image of man, things, and life.

—1978

Text © Estate of Luigi Ghirri; images © Estate of Luigi Ghirri and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York.

It's Beautiful Here, Isn't It...

It's Beautiful Here, Isn't It...$55.00

Luigi Ghirri – Kodachrome

When he published Kodachromes, Ghirri wrote a short exposé on his sources of inspiration, the notion of “deleted space,” and the things he is not interested in. That essay is reproduced below. It was included in Aperture’s 2008 volume It’s Beautiful Here, Isn’t It.

—Paula Kupfer

Luigi Ghirri, Bologna, 1973. © Estate of Luigi Ghirri, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Kodachrome: Introduction

I

In 1969 the newspapers published the photograph taken from the spaceship traveling to the moon. This was the first photograph of the entire Earth.

The image that man had pursued for centuries was presented for our view; it held within it all previous, incomplete images, all books that had been written, all signs, those that had been deciphered and those that had not. It was not only the image of the entire world, but the only image that contained all other images of the world: graffiti, frescoes, paintings, writings, photographs, books, films. It was at once the representation of the world and all representations of the world.

And yet this total vision, this re-description of everything, obviated the possibility of translating the total hieroglyph. The power of containing everything was annulled in the face of the impossibility of seeing everything all at once. The event and its representation, seeing and being contained, were presented—once again—to humanity as an insufficient response to the same old questions.

This possibility of total duplication, however, enabled us to glimpse the potential for deciphering the hieroglyph; we had the two poles of doubt and secular mystery: the image of the atom and the image of the world, finally looking at each other face to face. The space between the infinitely small and the infinitely large was filled by the infinitely complex: man and his life, nature.

The need for information or for knowledge emerges from these two extremes—fluctuating between the microscope and the telescope—to be able to translate and interpret reality or hieroglyph.

Luigi Ghirri, Paris, 1972. © Estate of Luigi Ghirri, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

II

My work emerges from the desire and the need to interpret and translate the sense of this sum of hieroglyphs—not only the easily identifiable reality of the reality that has highly symbolic content, but also thoughts, memories, imagination, and fantastical or alienated content.

For my purposes, photography is extraordinarily important, because of its specific characteristics. In photography, the deletion of the space that surrounds the framed portion is as important for me as what is represented: it is thanks to this deletion that the image takes on meaning, becoming measurable. The image continues, of course, in the visible realm of the deleted space, inviting us to see the rest of reality that is not represented.

This double aspect of representing and deleting not only evokes the absence of limits, excluding every idea of completeness of finitude, but shows us something that cannot be delimited: reality itself.

The possibility of seeing and penetrating the universe of reality instead passes through all representations and cultural models that are known and given to us as defined and decisive. Our relationship with reality and life is that same relationship that exists between the satellite image and the actual earth.

Thus photography, with its indeterminacy, becomes a privileged subject it allows us to move away from the symbolic nature of defined representations, and we can attribute to it a value of truth. The possibility of analysis in time and space of the signs that form reality (the entirety of which has always been elusive) thus allows photography, with its fragmentary nature, to be closer to what also cannot be delimited: physical existence.

So I am not interested in images and “decisive moments,” the analysis of language in and of itself, aesthetics, the concept of all-consuming idea, the emotion of the poet, the culled quotation, the search for a new aesthetic creed, the use of a style.

My duty is to see with clarity, and this is why I am interested in all possible functions—without separating any of them out, but taking them on as a whole, in order to be able, from time to time, to see the hieroglyphs I have encountered and make them recognizable.

Luigi Ghirri, Chartres, 1977. © Estate of Luigi Ghirri, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

III

The daily encounter with reality, the fictions, the surrogates, the ambiguous, poetic, or alienating aspects, all seem to preclude any way out of the labyrinth, the walls of which are ever more illusory… to the point at which we might merge with them.

The meaning that I am trying to render through my work is a verification of how it is still possible to desire and face a path of knowledge, to be able finally to distinguish the precise identity of man, things, life, from the image of man, things, and life.

—1978

Text © Estate of Luigi Ghirri; images © Estate of Luigi Ghirri and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York.

It's Beautiful Here, Isn't It...

It's Beautiful Here, Isn't It...$55.00

March 22, 2013

See, Memory

Chirodeep Chaudhuri’s exhibition A Village in Bengal is on view at Project 88, Mumbai, until March 25.

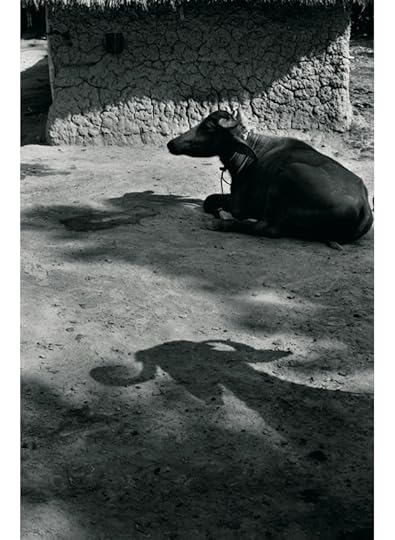

Chirodeep Chaudhuri, Untitled–11, 2012, from the series A Village in Bengal. Courtesy of the artist and Project 88, Mumbai.

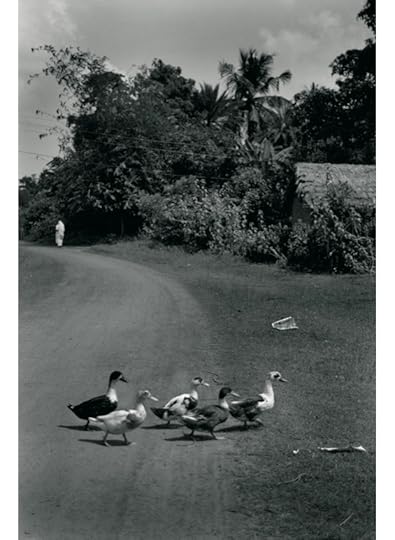

Chirodeep Chaudhuri, Untitled–13, 2012, from the series A Village in Bengal. Courtesy of the artist and Project 88, Mumbai.

Chirodeep Chaudhuri, Untitled–03, 2012, from the series A Village in Bengal. Courtesy of the artist and Project 88, Mumbai.

Chirodeep Chaudhuri, Untitled–12, 2012, from the series A Village in Bengal. Courtesy of the artist and Project 88, Mumbai.

Chirodeep Chaudhuri, Untitled–20, 2012, from the series A Village in Bengal. Courtesy of the artist and Project 88, Mumbai.

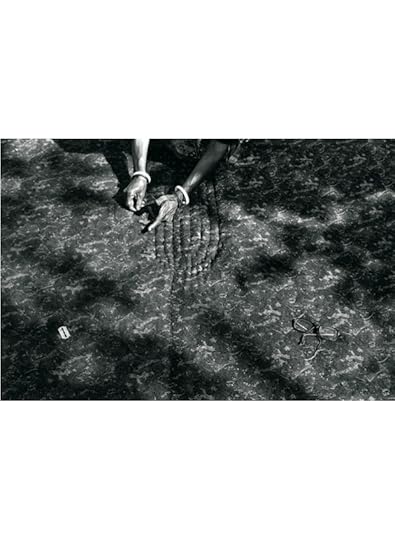

Chirodeep Chaudhuri, Untitled–14, 2012, from the series A Village in Bengal. Courtesy of the artist and Project 88, Mumbai.

This exhibition of twenty-two black-and-white photographs samples the images included in Chirodeep Chaudhuri’s recent book A Village in Bengal, which records life in Amadpur, his parents’ ancestral village in the northeast Indian state of West Bengal, where he spent holidays as a child. Travelling to Amadpur annually over twelve years, Chaudhuri has captured the town’s life thoroughly and unsentimentally. His intense gaze takes in many inhabitants, animals, and architectural details: there is a decrepit terra-cotta temple; ducks crossing an unpaved road, single file, like the Beatles on the cover of Abbey Road; a bull at rest, his expressive shadow merging with that of the shade he’s sought; and a throng of women standing before an elegant landowner’s villa. This range of imagery could very well describe rural settings elsewhere in India. Yet Chaudhuri’s ability to capture gestures, architecture, and landscape distils these scenes of a symbolic home into a coherent, singular narrative which treats the photographer’s stated intention—“to see, store, and air again the unutterably fragile experience of home.” A Village in Bengal is a serious exploration of memory and uncertain recollection, filtered through the vivid panorama of the annual festival of Durga Pujo.

Durga Pujo is an autumnal fête celebrating a principal female Hindu deity of destruction. To adherents and outsiders alike, Pujo, as the festival is sometimes called, is emblematic of Hindu Bengali identity. Many view this vibrant five-day event as the religious counterpart to the Bengali discursiveness that suffuses daily life, from fiery polemical discussions and a passion for the arts to political zeal and culinary profligacy. To his credit, Chaudhuri’s record of the kaleidoscopic activities around Durga Pujo stays this expectation. The show does not replicate the flamboyance traditionally associated with Durga Pujo by mechanically archiving exemplary moments. Rather, he has created a narrative complicated by silent passages about Amadpur that relate only metonymically to the festival. The resulting photo-essay is forcefully ordinary yet persuasively structured by combining precise details and necessary distance. It is here one begins to understand how a personal album can also function, as the photographer suggests, as a historical chronicle of “traces of a lifestyle that once existed.”

Chirodeep Chaudhuri, Untitled–18, 2012, from the series A Village in Bengal. Courtesy of the artist and Project 88, Mumbai.

The album-like quality of this series has an obvious derivation: the subjects include the photographer’s distant relatives in their palatial ancestral home in Amadpur. Untitled-18 depicts a group of women headed by one man assembled at a dining table topped with plates of food, possibly the ingredients of festival cuisine, and a boy of about two or three years old. The scene has all the traits of a conference at an impasse or at its end. Several of the figures cover their mouths with their hands; speech is absent; body language is static, detached. The torpor of the situation is strongly conveyed by the proximity of the camera. Ironically, this intimate stock-taking effectively lends the image the character of a political event, as though it were documented by an official recorder granted security clearance. Seen another way, however, the image also conveys the boredom of a certain kind of gaze, that of a child uninterested in a group of adults engaged in boring adult things—here literalized by the child’s listless body near the center of the composition, possibly a proxy for the photographer in his early years.

Likewise, Untitled-22, perhaps the best image in the show, is also a visual argument about the fickle nature of photographic meaning. In this case an archetypal episode drawn from the Pujo rituals offers a window onto people’s changing relationships to religious customs. The photograph features the multi-armed Durga at the moment of her immersion, the definitive endpoint of the festival. The camera is positioned above a body of water to show a group of boys who are thrusting a large, Ferris wheel–shaped contraption into its depths. The wheel-shaped contraption is the rear frame of a three-part Durga idol structure. Durga and the flanking idols are naked, as if disrobed in preparation for their watery commute. Surprisingly, they are missing their heads. The image is charged with movement and a romantic excess of luminosity. This arguably timeless scene of play and happiness might also represent what Pujo means to a band of frolicking boys at any moment in Bengali history. But key aspects of the scene caution against facile judgement, beginning with the headless, naked idols, whose schematic bodies, minus the ritual clothing, are less sexual than campy.In contrast, the half-naked boys are emphatically sensual. Caught between the sterile idols and our living gaze, they signal a palpably cinematic sensibility of compressed time: psychologically anachronistic frames joined into a one-shot face-off. It is as if Chaudhuri’s childhood self can recall not how fun looked but felt, which his adult photographer’s eye has stolen of innocence.

Chirodeep Chaudhuri, Untitled–22, 2012, from the series A Village in Bengal. Courtesy of the artist and Project 88, Mumbai.

Two other images explore the show’s central theme: how perception shifts in recollection. Untitled–11 (2012) is a twelve-by-eighteen-inch image of a man floating, belly-up, in a pond. His face is clear while the rest of his body is obscured by cloudy water. The play between clarity and ambiguity is obvious, as is the perceptual uncertainty of apprehending a physical body in an inherently murky medium; here the pond could easily stand in for the dark well of the past. In Untitled–14 (2012), a wiry set of hands are depicting quilting a bedspread. The hands’ shadows mask the needle and throw in doubt whether the act of sewing is taking place. After all, the bedspread is only minimally worked. At left in the foreground is a safety razor, and to the right a pair of glasses, which emphasize yet again the mental processes of editing and refraction that impact how memories form.

Prajna Desai is a writer of fiction and nonfiction, and an academic editor. She teaches architectural history in Mumbai, which is currently her home.

March 18, 2013

Art Directors Club 92nd Annual Awards

[image error]

The Art Directors Club (ADC), the first global creative collective of its kind, will host its ADC 92nd Annual Awards + Festival of Art and Craft in Advertising and Design next month. The three-day festival will be based at the W South Beach Hotel in Miami Beach, and will take place from April 2–4.

Unlike any other industry event, the ADC 92nd Annual Awards + Festival inspires international advertising, design, and visual communications professionals to reconnect and recommit to the art and craft of their industries by inspiring their inner artist. The festival will feature interactive, hands-on workshops led by key industry visionaries throughout each day, the ADC Design Night Celebration, the ADC 92nd Annual Awards Gala, parties and social gatherings throughout the week, and, of course, the beauty and culture that is South Beach.

For more information and details about the ADC 92nd Annual Awards + Festival of Art and Craft in Advertising and Design please visit the Art Director’s Club Award and Festival site.

ADC 92nd Annual Awards + Festival of Art and Craft in Advertising and Design

April 2–4, 2013

Miami Beach

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers