Aperture's Blog, page 196

May 31, 2013

Karl Blossfeldt at the Whitechapel Gallery

By Sarah James

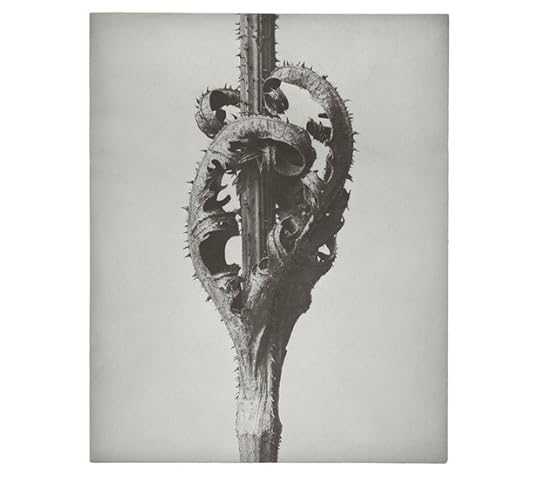

Karl Blossfeldt, Adiantum pedatum (Northern Maidenhair Fern), Young Rolled-up Fronds, undated. All photographs courtesy of Whitechapel Gallery, London.

Karl Blossfeldt, Aristolochia spec. (Birthwort), Shoots of Tendrils, undated.

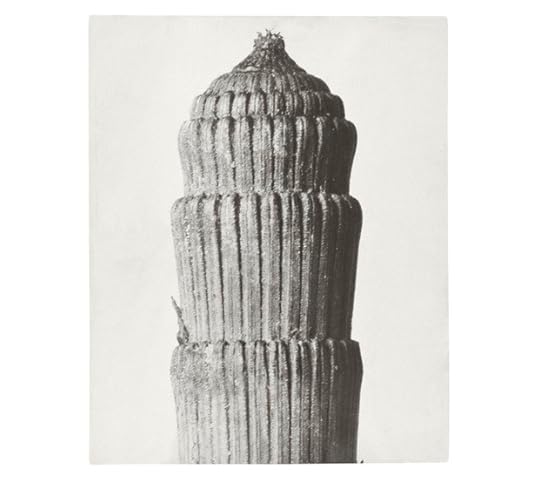

Karl Blossfeldt, Equisetum hyemale (Rough Horsetail), Top of Shoot, before 1926.

Karl Blossfeldt, Equisetum hyemale (Rough Horsetail), Cross Section of Stem, before 1926.

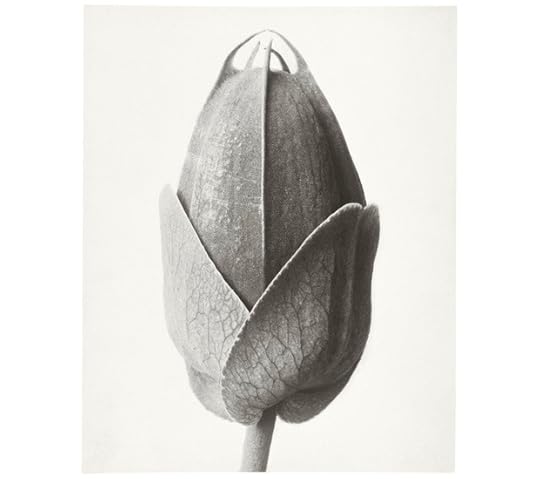

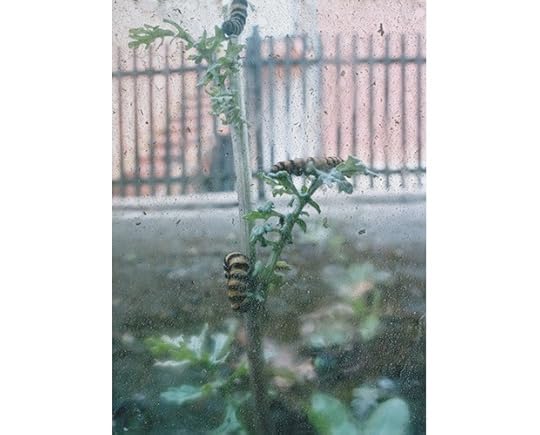

The German photographer Karl Blossfeldt spent a large portion of his life studying organic forms, selecting plant specimens like an entomologist who collects and catalogs butterflies. Yet, Blossfeldt captured his samples not with insect pins, but rather with a camera. Looking through the more than eighty original prints included in this exhibition, all produced using homemade cameras that allowed for extra magnification, one gains a clear sense of what fascinated Blossfeldt for over thirty-five years. The prints reveal grasping fronds, intricately unfolding tendrils, and stems covered in tiny rhizoids (root hairs) that seem to mutate into architectural structures, the frenetic patterned surfaces of modernist designs, or an anthropomorphic cast of curious actors.

Blossfeldt tends to be associated with the New Objectivity movement—the more realist wing of German modernism—alongside August Sander and Albert Renger-Patzsch. This grouping is not without problems, given these photographers’ profoundly different approaches to the camera, and the fact that Blossfeldt’s project, which he initiated during the 1890s, far predated German photographic modernism. The connection came about largely because the first major exhibition of Blossfeldt’s work, organized by the Berlin art dealer Karl Nierendorf, occurred in 1926, during the height of New Objectivity and Weimar photographic modernism. One of the strengths of Kirsty Ogg and Poppy Bowers’s curatorial framing is that it positions Blossfeldt’s epic project outside of New Objectivity and on its own terms, focusing on his working methods and the historical reception of his work.

Karl Blossfeldt, Dipsacus laciniatus (Cutleaf Teasel), Opposite Leaves at Stem, before 1926.

The first of the exhibition’s two galleries displays five of the photographer’s rarely seen working collages. These large-scale cardboard mounts—onto which cut-out contact-sheet images are assembled in jumbled grids and sequences, with handwritten notations scribbled on their edges and crosses and lines marked for cropping—were first unearthed in Blossfeldt’s estate in 1977. Their scrapbook-like appearance suggests a less clinical or systematic approach to his work than one gleans from viewing his black-and-white gelatin-silver prints. They are testimony to the playfulness of Blossfeldt’s comparative eye, which explored the graphic and aesthetic possibilities of the plant life he documented. This first gallery helps one to look anew at the prints displayed in the second. Far from the crisp, sharp, unforgiving lines and details of Renger-Patzsch’s photographs, many of Blossfeldt’s final images are closer to works-in-progress. Once magnified twenty-five times, the fuzzy outlines of a cross-sectioned horsetail stem, or the shadowy edges of its shoot-tip, suggest that his modified camera was not always capable of the dramatic enlargements he sought.

The reception of Blossfeldt’s monumental endeavor is framed by the display of a series of his photobooks, as well as a collection of newspapers, popular and avant-garde illustrated journals, and critical essays discussing his photographs. In the first gallery, three large vitrines contain Blossfeldt’s books from the late 1920s and early ’30s, beginning with the most well-known: Urformen der Kunst, published in Berlin in 1928. (The title is translated here, as it is most frequently, as Artforms in Nature, though the German original is perhaps better understood as Prototypes of Art.) In the second gallery, another two vitrines contain Walter Benjamin’s 1928 review of Blossfeldt’s book Neues von Blumen (News About Flowers) and a copy of Uhu, a Weimar general-interest magazine that often featured the photographs of such figures as László Moholy-Nagy, Martin Munkácsi, and Otto Umbehr, known as Umbo. There is also a copy of Georges Bataille’s 1929 essay on Blossfeldt, “The Language of Flowers,” which was published in the first issue of his radical surrealist journal Documents.

This emphasis on the historical reception of Blossfeldt’s photography is an important curatorial move, as it resituates Blossfeldt’s images in the publications where most people originally encountered them. It demonstrates how Blossfeldt’s strange organic corpus was received not only in the very different avant-garde worlds of Berlin and Paris, but also in the popular press. Crucially, it undermines a tendency to canonize Blossfeldt exclusively as a modernist art photographer.

Karl Blossfeldt, Passiflora (Passionflower) Bud, undated.

However, the Whitechapel’s presentation of Blossfeldt is not without its limitations, and ironically the commendable emphasis on production and contemporaneous reception serves to reveal these blind spots. Blossfeldt is claimed as the sole originator of the epic botanical documentary project, which in turn is presented as “one of the major influences in early-twentieth-century modernist art.” Yet the original intention of this ambitious photographic archive was not to produce modernist masterpieces, but rather pedagogical sources for German designers. Blossfeldt’s photographic studies were to serve as the basis of a manual or textbook not for fine or avant-garde artists, but for industrial, commercial, and technical designers and the mass-produced commodities they created. Further, the idea wasn’t Blossfeldt’s; it came from his professor and mentor, Moritz Meurer, who in 1889 was charged by the Prussian Board of Trade with bringing the design of Germany’s otherwise excellent technical and industrial products up to the level of international competitors at world fairs. Following in the footsteps of the architect Gottfried Semper, who in the mid-nineteenth century argued that the arts, like nature, were based on certain archetypal forms, Meurer turned to the natural world to provide a source for design. From this perspective—curiously sidelined at the Whitechapel—Blossfeldt’s nettle leaves and cow parsley stems cannot but transform before one’s eyes into the decorative wrought-iron forms of functional design and engineering—just as they surely must have done for Blossfeldt. Indeed, he must have brought this experience with industrial production and design to his photography. Prior to beginning this project, he had completed a casting apprenticeship at the Mägdesprung ironworks, a factory that produced, among other things, wrought-iron grilles and gates sumptuously decorated with plant motifs. Further, while photographically documenting the natural world, Blossfeldt produced a body of work even less well-known than his collages: a series of sculptural, educational, plant-like objects cast in bronze. Had these been included in this exhibition, they would have made clear just how much his curious and charismatic archive operated between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, between the industrial and the avant-garde, and between the sculpted or mass-produced object and the photograph.

Sarah James teaches in the History of Art Department at University College London. She writes frequently on photography and art for magazines including Frieze, Photoworks, and Art Monthly. Her book Common Ground: German Photographic Cultures Across the Iron Curtain was published this month by Yale University Press.

Karl Blossfeldt remains on view at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, until June 14.

May 28, 2013

On Travess Smalley’s Capture Physical Presence

By Lorenzo Durantini

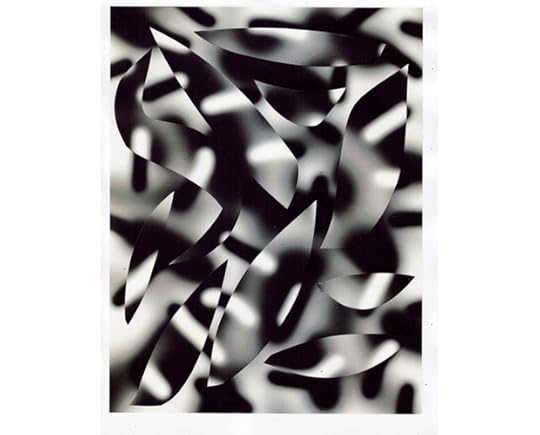

Travess Smalley, Capture Physical Presence #35, 2011.

Travess Smalley is a wonderful assembler. He pans and sifts like a digital prospector through the detritus of the computer screen, gleaning golden kernels of information that he recombines into images. He makes vibrantly colorful videos and digital prints—sometimes on paper, other times on silk, velvet, or vinyl. He creates works for web browsers, too; ultimately, he chooses whatever material or medium is most congenial to the particular strategy at hand. Smalley has a very intuitive and playful approach to imaging technology. His most recent work is based upon using the flatbed scanner as a creative tool. He applies to objects he scans a host of digital mark-making techniques, referencing modernist painting, 1990s-era digital culture, and the spuriously broad category of post-Internet art.

When I met Smalley in Chelsea recently, I mentioned James Welling’s distinction between pictures formed by a lens and images with a more immaterial provenance. It seemed to me that such a distinction is not particularly relevant to Smalley’s work. “I agree,” he said. “And neither is the distinction between photography and painting.” He continued, “In a recent interview Wolfgang Tillmans mentioned how he thinks of his photographs like paintings, and Gerhard Richter is using Photoshop to clone and mirror sections of his canvases, even though he still speaks of them as traditional paintings.” I asked Smalley whether the “photography” in his montage-like work is in the scanner used to capture the images. “Totally,” he responded. “It’s just light—applied and then recorded.”

Smalley’s first New York solo show, titled Capture Physical Presence, is at Higher Pictures on the Upper East Side. The exhibition consists of six handsomely framed inkjet prints of photomontages that range from approximately thirty-by-forty inches to forty-by-fifty inches. In this body of work, Smalley creates computer graphics that he then prints out, cuts up, and rearranges before scanning them back into the computer for further modification. Higher Pictures has an impressive track record of offering solo shows to young artists: Sam Falls, Jessica Eaton, Artie Vierkant, and Letha Wilson have all had solo exhibitions there in the last three years, and it has presented influential group shows that serve as useful context for thinking about Smalley’s current exhibition.

Travess Smalley, Capture Physical Presence #51, 2011.

Smalley’s work has a productive yet challenging relationship to photography. He does not use a camera. It is this distance that allows him to approach broader ontological questions: What is an image? How do images circulate within the technologies of contemporary culture? Smalley is interested in the physical quality of digital prints and the digital quality of physical things. The chance encounters he engenders between code and material also presciently forecast how technology is becoming increasingly entangled in both material and biological life. Smalley’s scalpel cuts mimic the vector tool of digital software; his deliberate degradation of gradients evokes halftone printing; and the printing and re-printing of inkjet prints misaligns and amplifies the invisible dot-matrix distribution of colors. Only two of the prints in the show have an even quadrilateral border. The rest have small protrusions that tug gently against the authority of the rectangle.

The abstract compositions in Capture Physical Presence are at once hurried and studied; they reflect the frenetic pace of screen-based productivity. Smalley diverts the quicker-faster-sharper attitude of networked image production into a more contemplative approach. The imperfections in Smalley’s process give his work an individual accessibility that is lost, for example, in Thomas Ruff’s epic photograms, recently exhibited in New York at David Zwirner. Ruff seems interested in digital tautologies that deceive the viewer into thinking they are analog; his photograms are created in a digital-imaging environment and then outputted with a simulated film grain that references silver-halide photography. Smalley instead veers towards intelligently fallacious syllogisms that falter in their logical coherence. It is these momentary losses of balance, this unease about slickness and perfection, that stymies the staid logic of digital information in his work.

The human scale and physical presence of Smalley’s works seem to resist the gravitational force of Tumblr and its daisy-chain of deauthored imagery. The sensation of standing in front of them is at once private and immersive, and the anti-reflective museum glass transmits all of the texture of the pigment prints. The scale feels like a close upright approximation of sitting in front of a desktop computer, yet the material qualities of the prints distinguishes them from the experience of the screen. As a case in point, while Smalley and I were chatting in the gallery he pulled out an iPad to show me more images from the twenty-five-strong series. We jokingly held up the high-resolution screen against a print for comparison, and I immediately recognized the difference between the flat pixels and the textured print, which had not been flush-mounted in its frame, allowing the paper to curl ever so slightly. These are the small pleasures that talented printmakers know how to appreciate and celebrate, however minute they might seem.

Lorenzo Durantini is an artist and curator working between New York, London, and Italy. In 2012 he curated Ristruttura at ProjectB, Milan, and Brush It In at Flowers, London. This year he will curate Debt & Riots at ProjectB and Syntax at the Museum for Contemporary Art MACRO, Rome. He reviewed a new book by David Benjamin Sherry for The PhotoBook Review Issue 004.

Travess Smalley, Capture Physical Presence #33, 2011.

Interview with Hans Gremmen, designer of Rinko Kawauchi’s Ametsuchi

On the occasion of the release of Japanese photographer Rinko Kawauchi’s new book, Ametsuchi , Aperture Foundation associate editor Brian Sholis spoke with Hans Gremmen, the book’s designer.

Rinko Kawauchi on press at Mart.Spruijt in The Netherlands.

Brian Sholis: You’ve worked on many photobooks, several of which deal with landscapes. Was this your first time working with a Japanese photographer? What was unique about your working relationship with Rinko Kawauchi?

Hans Gremmen: Many of the books I work on as a designer and/or editor indeed deal with the topic of the landscape. Almost always the artist approaches the landscape in a conceptual way. For instance, Cette Montagne, C’est Moi, by Witho Worms, is about the influence of the mine industry on the landscape, but it is also about photography itself, and the book is also about printing and poetry. When things come together in the right way, a publication can be about so much more thn its one ostensible topic.

This is also the case with Rinko Kawauchi’s Ametsuchi. It is a project about the changing landscape, religion, and circles of life and memory, but Ametsuchi is also very much about Rinko herself, and her relation to the medium of photography. The book itself—the way it is printed and bound—asks questions about the medium of the book, and how people tend to use them.

Rinko and Aperture publisher Lesley Martin challenged me to come up with design ideas that could make this a unique project. It was indeed my first collaboration with a Japanese photographer. But that is a great thing about photography: it tells stories, but does not speak a specific language.

BJS: Can you describe some of the “questions” you’ve asked about the medium of the book? What unusual printing and binding techniques will people discover when they encounter this book? And how do those techniques relate to Kawauchi’s photographs?

HG: The book is bound in a variation of Japanse binding. In regular Japanese binding you fold the paper in such a way that the sides are closed. In this book the closed side has moved to the top of the page; the sides and bottom are open. This results in a book that has an “parallel world” on the inside of the pages, in which some images are printed in inverted colors. By inverting the images the existential and poetic nature of Kawauchi’s work is enlarged: fire turns into water, night turns into day.

Reproductions from the book on press at Mart.Spruijt in The Netherlands.

BJS: In another interview you have spoken about how every design decision regarding a photobook should serve the photographs within it. The variation on Japanese binding is a bold, easily legible decision. Ametsuchi is also taller and narrower than many photobooks. What other, subtler design decisions characterize this project?

HG: The size of the book is very practical: it is the maximum size you can get out a sheet of paper with this way of binding. I could go a bit bigger, but that would have limited me in the choice of paper. I wanted to avoid that limitation because the paper is a very important factor in binding the book. The paper needed to be flexible (read: “thin”), but the opacity should also be high. Otherwise the inverted images would interfere too much with the images on the other side of the paper. We made tests with and without images printed on the back, to see what the effect on the photographs would be; and with the paper we ultimately chose, there was no effect.

The endpapers and dustjacket are printed on a special paper as well; a paper which is rough on one side, smooth on the other. The design of this book looks for opposites—on various levels. This reflects in the choice of paper, in the way the images are inverted, but also in typography. On the book’s case, the artist’s name is printed upside down.

The design of this book also refers to a cycle. The book begins and ends Rinko’s name, which appears on both “ends” fo the dust jacket, and the title of the book likewise appears on the first and last pages of the book. Also the image on the endpapers repeats, as does the typography on the case. For this book I sought to make its major themes visible not only in the standout decisions, but also its many small details.

Ametsuchi

Ametsuchi$80.00

May 22, 2013

Aperture 211—Editors’ Note: Curiosity

What provokes us to pursue something, to want to find out more? “Curiosity is an oddly ambivalent word,” notes critic Brian Dillon in this issue. It can lead, he points out, to a range of conditions, from utter distraction to deep concentration, all stemming from the “urge to discover.” Photography has long served as a medium of choice not only for the curious practitioner, but also for his or her audience, whose curiosity may be either aroused or appeased by an image. In the following pages, the desire to see and visualize—in the often interconnected fields of science and art—serves as a capacious framework for approaching photography’s relationship to curiosity.

Stephen Gill, from the series Coexistence, 2012. © Stephen Gill

As Berenice Abbott once noted, photography is “science’s child,” a familial relationship well illustrated by revisiting the medium’s early decades. Historian Jennifer Tucker looks back into the nineteenth century, when photographic “first glimpses” of microbes, solar eclipses, or the surface of Mars had lives as both news items and entertaining spectacles, and when the young medium of photography was itself still viewed as something of a technical marvel. Tucker points out that in today’s atmosphere of image inundation “first glimpses”—if they still exist at all—make a less breathtaking impression. The images recently transmitted from NASA’s Curiosity Mars Rover, for example, are uncannily similar to familiar photographs of the Earth’s deserts. Such comparisons of the terrestrial with the alien are investigated here by David Campany, who discusses photographs by an eclectic group—Man Ray, Frederick Sommer, and Sophie Ristelhueber, among others—that may cause viewers to wonder exactly what they are seeing. Curator Joel Smith examines an equally inscrutable group of images, by Katy Grannan, Frank Gohlke, Naoya Hatakeyama, and others, in his guide to making (and making sense of ) “photographs of nothing.”

While some artists have more or less intentionally confounded viewers, researchers in other realms of image making have used photographs to show us the world as it is, in an attempt to come to a deeper understanding of the phenomena that surround us. Science historian Peter Galison and artist Trevor Paglen discuss the history of objectivity, as well as how images—now digital, searchable, everywhere—may be shifting from being mere depictions to performing specific functions.

Whether obliquely sidling up to our attention or demanding it outright, one thing that photography has always done is reveal. Harold E. Edgerton, through his famous flash experiments, slowed time down to unveil what had once been “invisible” actions. Berenice Abbott, too, aimed to bring the strangeness and beauty of scientific subjects to the public—as with her renderings of interference patterns in light, or her illustration of static electricity, featured on this issue’s cover. Photography historian Kelley Wilder discusses Abbott’s work along with that of Edwin E. Jelley, a little-known research scientist at Kodak who was fascinated by the forms and structures of light. Jelley’s work paved the way for the commercially available color processes that would be taken up by artists such as Lázsló Moholy-Nagy, who experimented with color photograms in the 1930s. Moholy-Nagy’s images in turn offer a departure point for Thomas Ruff’s latest body of work, also featured in this issue: photograms for the digital era, created with 3-D imaging software. German photographer Horst Ademeit was, by contrast, terrified of technology: his enigmatic and obsessive project, introduced here by curator Lynne Cooke, used the instant Polaroid form to document what he named “cold rays,” an unseen force he believed emanated from his apartment’s electrical sockets. While Ademeit’s fraught attentions were absorbed in an intensely insular world, other photographers train their lenses with equal fervor outward, toward the mysteries of the atmosphere and the celestial bodies. Lisa Oppenheim follows this impulse with her recent “lunagrams,” heliograms, and more, taking her cue from nineteenth-century astronomical imagery.

Whether investigations originate in the nineteenth, twentieth, or twenty-first century, by using the latest technologies or by reviving older ones, the desire to lay bare the unknown is perpetual. Yet, whether the realm is art or science, photography—like any medium of investigation— may lead not to answers but to further questions: as Joel Smith observes here, photographs can “doubt as well as certify, negate as well as indicate, embody absence as well as substance.”

—The Editors

Lisa Oppenheim: Elemental Process

By Brian Sholis

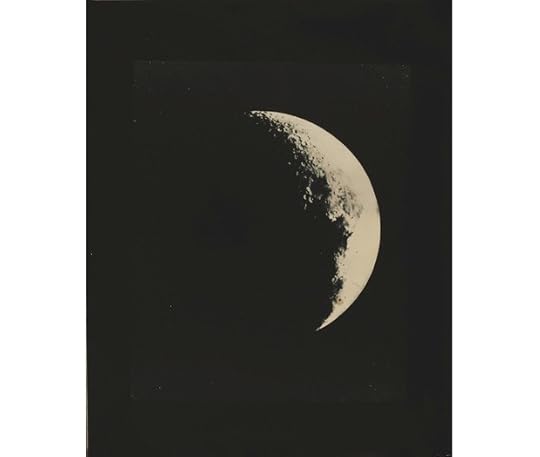

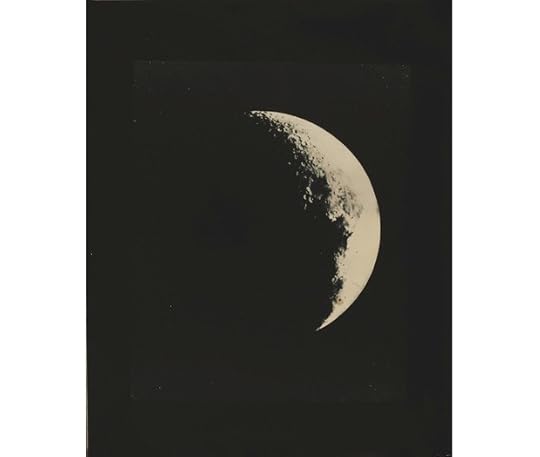

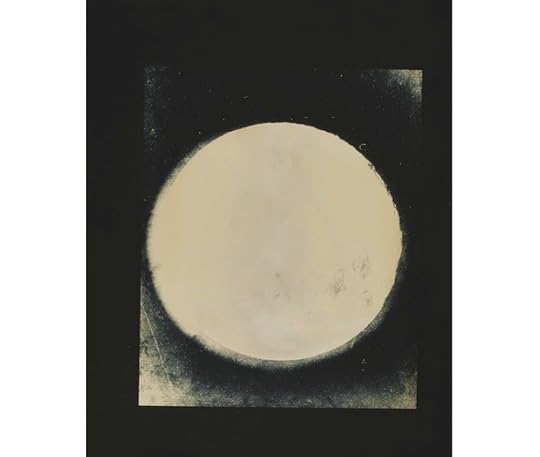

Lisa Oppenheim, Lunagram #1 (Version 2), 2010. All works © Lisa Oppenheim and courtesy Harris Lieberman, New York, and The Approach, London.

Lisa Oppenheim, Lunagram #3 (Version 2), 2010.

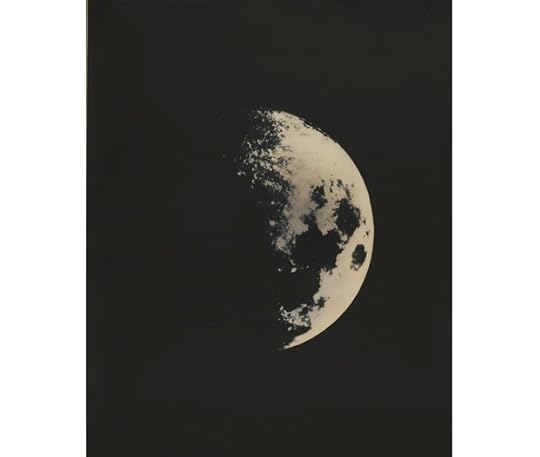

Lisa Oppenheim, Lunagram #9 (Version 2), 2010.

Lisa Oppenheim, A monstrous column of roaring flame. Star Oil Co. Loucke No. 3 on fire since Aug. 7, 1913. Most disastrous fire in Caddo oil field and largest single well fire in history of U.S. of A. Daily loss of oil estimated at 30,000 barrels. 1913/2012 (Version V), 2012. From the series Smoke, 2011–12.

Lisa Oppenheim, Billowing. As we were driving up to Norfolk yesterday I saw the Enfield fire; where a Sony distribution centre sat ablaze by rioters was just pouring out smoke over the motorway. The sheer amount of smoke was quite surprising, and today smoke was still covering the motorway. I feel such despair at people who have taken to looting; so angry at the destruction people can cause. 2011/2012. (Version V), 2012. From the series Smoke, 2011–12.

For nearly a decade, Lisa Oppenheim has teased apart the individual steps of picture-making, wringing from the medium’s technical apparatus a surprisingly broad range of meanings. She is informed by the legacy of Conceptual art, but her most recent series, sampled in the following pages, reach back further in time for their inspiration. Time is itself a central focus of this work, which meditates on the various ways photography registers duration—the length of the exposure, the gap between a picture’s making and its viewing—and how our sense of it dilates in a photograph’s presence. This effort is in the service, the New York– and Berlin-based artist has said, of recovering the surprises offered by photography’s materials, and of dwelling in “the magic of the photographic process.” Through cool calculation, Oppenheim has devised an art of surprising affectiveness, equal parts romantic and rigorous.

The emotional resonance of Oppenheim’s works has often rested in her use of (quite literally) universal subjects. The sun and the moon—giver of light and the ultimate light reflector—feature regularly, from a 2006 slide projection in which the artist holds postcards of sunsets in front of the real thing to a two-channel 16mm film installation, made in 2008, that is based upon images of the Earth and the moon made the night of the Apollo mission’s first lunar landing. The moon recurred as the subject of a 2010 series of unique silver-toned photograms she dubbed Lunagrams. To make these works, Oppenheim borrowed from the archives of New York University mid-nineteenthcentury glass-plate negatives by John and Henry Draper depicting the moon. She made large-format copy negatives, placed them on photographic paper, then exposed them to the moon at the time of the lunar phase depicted in the original. Decades collapse as one image, made by an enthusiast whose work was as much science as art, begets another. A related series of Heliograms was made in 2011: she exposed a photograph of the sun originally taken on July 8, 1876, to sunlight at different times of day during each month that year. Irregular amounts of sunlight means not every work is equally exposed, and there are gaps in the series where Oppenheim’s obligations prevented her from capturing a scheduled image. The individual results once again warp our understanding of two distinct instants, but when seen in aggregate, the Heliograms also chart the passage of the artist’s days. These silvery and golden works possess an elemental allure—the metals themselves, the primitive processes used by the medium’s first exponents—but also acknowledge that copies are always already imperfect, and that life and time conspire to make them so.

Lisa Oppenheim, Passage of the moon over two hours, Arcachon, France, ca. 1870s/2012, April 11, 2012.

Oppenheim literalizes her attempt to translate the essence of earlier images in her 2011–12 series Smoke. There, she isolated details of smoke from a wide range of images of fire, then turned these semiabstract compositions into digital internegatives. Rather than use the light of an enlarger to expose these negatives, Oppenheim used the flames from a match, from a culinary torch, and from other sources to expose—and solarize—these images. From a 1913 oil-field explosion to World War II–era aerial surveillance to journalists’ images of the 2011 North London riots, the absent fires implied by the smoke have been made visible by altogether different flames. The resultant works, which look like polished-silver outtakes from Alfred Stieglitz’s Equivalents series, add a canny rumination on presence and absence to Oppenheim’s usual investigation of temporality. As with all her recent works, the Smoke series resides in interstitial spaces: between two images separated by time and place; between materialist and conceptual approaches to the medium; between intellect and emotion. In these seams Oppenheim finds a locus of mystery.

Top row: Lisa Oppenheim, Heliograms, July 8th, 1876/December 8th, 2011, 2011. Middle row: Lisa Oppenheim, Heliograms, July 8th, 1876/December 14th, 2011, 2011. Bottom row: Heliograms, July 8th, 1876, December 21st, 2011, 2011.

Martin Parr Beach Party and Portrait Shoot (Photos)

Martin Parr Beach Party and Portrait Shoot.

Martin Parr Beach Party and Portrait Shoot.

Martin Parr Beach Party and Portrait Shoot.

Martin Parr Beach Party and Portrait Shoot. Photograph by Sophie Finkelstein.

Martin Parr Beach Party and Portrait Shoot. Photograph by Sophie Finkelstein.

Martin Parr Beach Party and Portrait Shoot. Photograph by Sophie Finkelstein.

Martin Parr Beach Party and Portrait Shoot. Photograph by Sophie Finkelstein.

Martin Parr Beach Party and Portrait Shoot. Photograph by Sophie Finkelstein.

Martin Parr Beach Party and Portrait Shoot. Photograph by Sophie Finkelstein.

Martin Parr Beach Party and Portrait Shoot. Photograph by Sophie Finkelstein.

Martin Parr Beach Party and Portrait Shoot. Photograph by Sophie Finkelstein.

Martin Parr Beach Party and Portrait Shoot. Photograph by Sophie Finkelstein.

Martin Parr Beach Party and Portrait Shoot. Photograph by Sophie Finkelstein.

Martin Parr Beach Party and Portrait Shoot. Photograph by Sophie Finkelstein.

Martin Parr Beach Party and Portrait Shoot. Photograph by Sophie Finkelstein.

Martin Parr Beach Party and Portrait Shoot. Photograph by Sophie Finkelstein.

Martin Parr Beach Party and Portrait Shoot. Photograph by Sophie Finkelstein.

On Saturday, May 18, Aperture presented an all-day portrait shoot and beach party with the one and only Martin Parr, in conjunction with the release of the beach-bag-size edition of his monograph Life’s a Beach and the related exhibition at Aperture Gallery. Aperture patrons and the public joined us to have beach-themed portraits snapped by Parr, accompanied by friends, family, and even cherished pets. Click through the slideshow above to see a selection of highlights from the event.

This event was made possible with support from Canon U.S.A., Inc., Gosling’s Rum, and Mondrian Soho. Music by Milo McBride. Event photography by Sophie Finkelstein.

— Life's a Beach Limited Edition Towel

Life's a Beach Limited Edition Towel

$75.00

Life's a Beach

Life's a Beach

$25.00

Life's a Beach

Life's a Beach

$300.00

May 21, 2013

Interview with Anne Hardy

For more than a decade, London-based artist Anne Hardy has exhibited photographs of interior spaces she has constructed in her studio. In her new exhibition at Maureen Paley in London, on view through May 26, she has included freestanding sculptural installations alongside her photographs. Brian Sholis spoke with Hardy by e-mail about this development in her art.

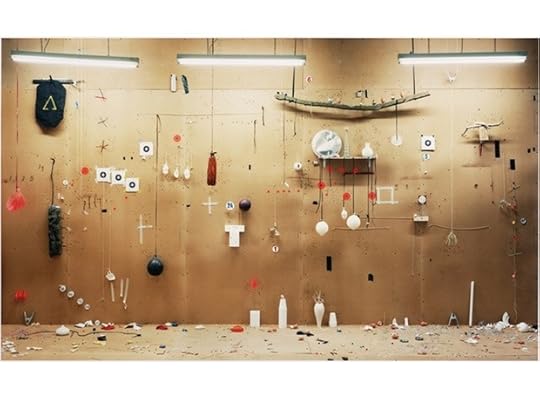

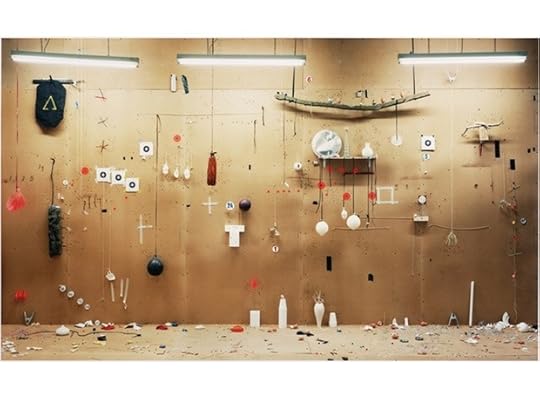

Anne Hardy, Notations (2012). All images © Anne Hardy and courtesy Maureen Paley, London.

Anne Hardy, Script (2012).

Anne Hardy, Two Joined Fields—Field (/\) and Field (decagon) (2013).

Anne Hardy, Fieldwork (materials) (2013). Interior view.

Installation view of Anne Hardy, Maureen Paley, London, 2013. From left: Fieldwork (materials) (2013); Shelf (2013); and Script (2012).

Brian Sholis: For years you’ve created objects and built environments to photograph, yet this is one of the first times you’ve allowed exhibition viewers to have access to these materials and spaces. Can you speak about the privacy of the studio and the decision to exhibit things that had otherwise gone unseen by the public?

Anne Hardy: In 2011 I was an artist-in-residence at the Camden Arts Centre. Though private, the studio itself felt like a gallery, and sits alongside the venue’s gallery spaces. My ambition for the residency was to build one of the “sets” I construct for my photos, but also to have the chance to evaluate one of these structures outside the context of my own studio, and to invite others to see it as well. In a way, the time at Camden was transitional for me, and allowed me to connect two environments that had previously been separate in my practice—the private space of the studio and the public space of the exhibition. I had become increasingly interested in the structures I was building in order to realize my images, and wanted to think about what further role—if any—they might play in my work, or if they (or something like them) might in fact be the work. They have physical and material qualities, and allow for the viewer’s movement through them, that I cannot replicate with photographs.

Working in the gallery for a month before this exhibition felt a bit like a second residency, but with the added clarity of the space being given over to an exhibition at the end. In this exhibition there are three sculptural spaces—rooms you can enter that have not been used to make the photographs that they are exhibited alongside. They are independent sculptures, built specifically to fit the space in a particular way. For example, it’s important to me that you do not see the doors of two of them as you walk into the gallery, but must walk around them in order to access their interiors.

BJS: So these constructions are no longer “process materials.”

AH: Well, last year, as I was preparing for my show at the Secession in Vienna and its accompanying book, I began to think about how I could open up other ways into my work without presenting work-in-progress studio shots. The small photograph Shelf (2013) is a product of this. It’s one of several smaller images meant to act as a detail without actually being a detail of any particular work—it’s like a newly made potential detail. The two larger photographs in the show at Maureen Paley also use materials from my working process in new ways.

Anne Hardy, Field (decagon) (2013). Interior view.

It’s exciting to finally exhibit physical spaces that people can enter. I have thought about it for a long time, and wanted to do it only at a point when I felt they would not be seen as subsidiary to the images. I’m happy to see the photographs and the structures face one another equally and hold their own ground. I now feel like I can explore the relationships between environments, images, and objects.

BJS: Was your years-long desire to find a way to achieve this balance intrinsic to your studio practice? Or was it fostered by the relationship between images and objects in the culture at large? Or both?

AH: I am interested in the indeterminate state I perceive in cast-off materials and objects—in rubbish. Something that appears unimportant can become significant and meaningful for an individual who chooses to invest time with it. I think these things can create a space for the imagination that is quite free. I want this quality to be intrinsic to the materials I use in my work, and in the relationship between physical spaces and the images. What previously was captured by single images can now, I hope, open out across an entire exhibition of works.

BJS: How does the fact that your photographs nearly always depict a shallow space, bounded at the back by a wall, play into this? Are you attempting to create an “inhabitable” space for this free play of thought?

AH: Yes, in recent images such as Rift, Script, and Notation I really concentrated on making image-spaces that are less interpretable, that are flatter or more confusing in their spatial layout, in order to open up how the image could be read. I want viewing these works to be in part about the process of reading them, coming to understand them.

Anne Hardy, Shelf, 2013.

BJS: And is making an image as much about the “process of reading” as about the actual space depicted a way of creating a metaphorical link between the construction of space and the “construction” of a self? Put more simply, to what extent are the spaces you photograph meant to be psychologically charged?

AH: I hope that the process of comprehending the new photographs is less about resolving a depiction of a particular kind of place, in which you say “Oh, this reminds me of that” and in so doing distance yourself from it. Instead I hope the ambiguity will cause viewers to be more aware of what they are projecting onto the image. The sculptural works take this one step further by involving you physically with the work—you can literally step into them.

I want the psychological charge of the work to come from this combination of myself, the viewer, and the imagined potential of these spaces and objects.

May 20, 2013

#MyApertureMag Instagram Contest Winner Announced

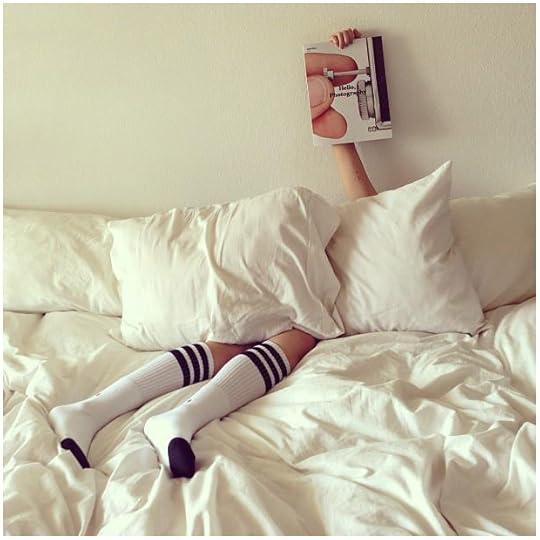

Photo by @heathersten on Instagram

We recently asked Aperture readers to post portraits of themselves with the Spring 2013 relaunch issue, “Hello, Photography,” on Instagram with the tag #myaperturemag. We sorted through dozens of great entries (see a slideshow, including the four runners-up, below) and chose the photo above, submitted by @heathersten, as the winner. For submitting the winning photo, @heathersten will receive a free one-year subscription to Aperture magazine and $125.00 to spend at the Aperture Gallery and Bookstore in New York or online.

Thanks to everyone who participated in the contest. Don’t forget to follow us on twitter @aperturefnd, and remember to check our Instagram feed regularly for future contests.

Also, stay tuned for Aperture magazine‘s Summer 2013 Issue, “Curiosity,” available this month on newsstands and online.

Photograph by @scriptorsum on Instagram

"(After Jeff Wall)" Photography by @clutterandvine on Instagram

Photo by @acmillerphoto on Instagram

Photograph by @ walkyourcamera on Instagram

Photograph by @heathersten on Instagram

May 19, 2013

Another workshop example

Description:

For over thirty years, the weekly New York Times Magazine has shaped the possibilities of magazine photography, through its commissioning and publishing of photographers’ work across the spectrum of the medium, from photojournalism to fashion photography and portraiture. In this exhibition, focusing primarily on the past fifteen years, long-time New York Times Magazine Photo Editor Kathy Ryan provides a behind-the-scenes look at the collaborative, creative processes that have made this magazine the leading venue for photographic storytelling within contemporary news media.

The exhibition is comprised of ten individual modules, each of which focuses on a notable project or series of projects that has been presented in the pages of the Magazine. The featured projects mirror the Magazine‘s eclecticism, presenting seminal examples of reportage and portraiture as well as fine art photography.

Kuwait Oil Fields, Sebastião Salgado; Dream House, Gregory Crewdson; Assignment: Times Square, featuring Chuck Close, Mary Ellen Mark, and Larry Towell; Olympic Portraiture, Ryan McGinley; Korengal Valley Afghanistan, Lynsey Addario; A Response to 9/11, featuring Andres Serrano and Steve McCurry; Great Performers, featuring Hellen van Meene and Rineke Dijkstra; Fashion Crossovers, featuring Lee Friedlander, Nan Goldin, and Jeff Koons; Where the Protons Will Play, Simon Norfolk; Conflict Photography, Paolo Pellegrin.

The exhibition also includes contextualizing reading material for all the projects on exhibit, and an extensive series of selected tearsheets and covers from the last thirty years of the Magazine.

Curated by Kathy Ryan and Lesley A. Martin.

This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Video from Palau Robert, Barcelona, On view: September 20, 2012–December 2, 2012

Contents:

The exhibition consists of 126 works by thirty-five artists spread over ten modules. Contextual material includes contact sheets, snapshots, six video works, personal correspondence, tear sheets and original magazines that offer further insight into the creative process. Artists are: Lynsey Addario, David Armstrong, Lyle Ashton Harris, Roger Ballen, Lillian Bassman, Chuck Close, Fred Conrad, Gregory Crewdson, Philip Lorca diCorcia, Rineke Dijkstra, Mitch Epstein, Angel Franco, Lee Friedlander, Nan Goldin, Edward Keating, Jeff Koons, Inez van Lamsweerde and Vinoodh Matadin, Annie Leibovitz, Mary Ellen Mark, Steve McCurry, Ryan McGinley, Jeff Mermelstein, Abelardo Morell, Simon Norfolk, Michael O’Neil, Paolo Pellegrin, Jack Pierson, Sebastião Salgado, Alfred Seiland, Nancy Seisel, Andres Serrano, Malick Sidibé, Larry Towell, Lars Tunbjörk, Hellen van Meene.

Book:

The New York Times Magazine Photographs

Edited by Kathy Ryan

Hardcover with jacket

11 1/2 x 9 1/2 in.

448 pages

500 4-color images

Participation Fee:

Please call Annette Booth at (212) 946-7128.

$25,000 for an 8-week showing. The host venue is responsible for pro-rated shipping and insurance.

Availability:

The exhibition is available through 2015.

Current Venue List:

Les Rencontres d’Arles

Église de Sainte-Anne, Arles, France

Monday, July 4 – Sunday, September 4, 2011

Foam

Keizersgracht 609 Amsterdam, Netherlands

Thursday, March 22 – Thursday, May 31, 2012

Palau Robert

Passeig de Gràcia, 107, Barcelona, Spain

Thursday, September 20 – Sunday, December 2, 2012

Centro de Extensión, Universidad Católica de Chile

Alameda 340, Santiago, Chile

Monday, April 15 – Friday, May 31, 2013

Fotofestiwal Lodz

Lodz, Poland

The New York Times Magazine Tearsheets

Thursday, June 6 – Tuesday, June 25, 2013

MOCA Jacksonville

333 North Laura Street

Jacksonville, FL 32202

Saturday, April 26 – Sunday, August 24, 2014

Hunter Museum of American Art

10 Bluff View Avenue, Chattanooga, TN

Monday, November 24, 2014 – Sunday, March 29, 2015

Featured workshop example

Description:

For over thirty years, the weekly New York Times Magazine has shaped the possibilities of magazine photography, through its commissioning and publishing of photographers’ work across the spectrum of the medium, from photojournalism to fashion photography and portraiture. In this exhibition, focusing primarily on the past fifteen years, long-time New York Times Magazine Photo Editor Kathy Ryan provides a behind-the-scenes look at the collaborative, creative processes that have made this magazine the leading venue for photographic storytelling within contemporary news media.

The exhibition is comprised of ten individual modules, each of which focuses on a notable project or series of projects that has been presented in the pages of the Magazine. The featured projects mirror the Magazine‘s eclecticism, presenting seminal examples of reportage and portraiture as well as fine art photography.

Kuwait Oil Fields, Sebastião Salgado; Dream House, Gregory Crewdson; Assignment: Times Square, featuring Chuck Close, Mary Ellen Mark, and Larry Towell; Olympic Portraiture, Ryan McGinley; Korengal Valley Afghanistan, Lynsey Addario; A Response to 9/11, featuring Andres Serrano and Steve McCurry; Great Performers, featuring Hellen van Meene and Rineke Dijkstra; Fashion Crossovers, featuring Lee Friedlander, Nan Goldin, and Jeff Koons; Where the Protons Will Play, Simon Norfolk; Conflict Photography, Paolo Pellegrin.

The exhibition also includes contextualizing reading material for all the projects on exhibit, and an extensive series of selected tearsheets and covers from the last thirty years of the Magazine.

Curated by Kathy Ryan and Lesley A. Martin.

This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Video from Palau Robert, Barcelona, On view: September 20, 2012–December 2, 2012

Contents:

The exhibition consists of 126 works by thirty-five artists spread over ten modules. Contextual material includes contact sheets, snapshots, six video works, personal correspondence, tear sheets and original magazines that offer further insight into the creative process. Artists are: Lynsey Addario, David Armstrong, Lyle Ashton Harris, Roger Ballen, Lillian Bassman, Chuck Close, Fred Conrad, Gregory Crewdson, Philip Lorca diCorcia, Rineke Dijkstra, Mitch Epstein, Angel Franco, Lee Friedlander, Nan Goldin, Edward Keating, Jeff Koons, Inez van Lamsweerde and Vinoodh Matadin, Annie Leibovitz, Mary Ellen Mark, Steve McCurry, Ryan McGinley, Jeff Mermelstein, Abelardo Morell, Simon Norfolk, Michael O’Neil, Paolo Pellegrin, Jack Pierson, Sebastião Salgado, Alfred Seiland, Nancy Seisel, Andres Serrano, Malick Sidibé, Larry Towell, Lars Tunbjörk, Hellen van Meene.

Book:

The New York Times Magazine Photographs

Edited by Kathy Ryan

Hardcover with jacket

11 1/2 x 9 1/2 in.

448 pages

500 4-color images

Participation Fee:

Please call Annette Booth at (212) 946-7128.

$25,000 for an 8-week showing. The host venue is responsible for pro-rated shipping and insurance.

Availability:

The exhibition is available through 2015.

Current Venue List:

Les Rencontres d’Arles

Église de Sainte-Anne, Arles, France

Monday, July 4 – Sunday, September 4, 2011

Foam

Keizersgracht 609 Amsterdam, Netherlands

Thursday, March 22 – Thursday, May 31, 2012

Palau Robert

Passeig de Gràcia, 107, Barcelona, Spain

Thursday, September 20 – Sunday, December 2, 2012

Centro de Extensión, Universidad Católica de Chile

Alameda 340, Santiago, Chile

Monday, April 15 – Friday, May 31, 2013

Fotofestiwal Lodz

Lodz, Poland

The New York Times Magazine Tearsheets

Thursday, June 6 – Tuesday, June 25, 2013

MOCA Jacksonville

333 North Laura Street

Jacksonville, FL 32202

Saturday, April 26 – Sunday, August 24, 2014

Hunter Museum of American Art

10 Bluff View Avenue, Chattanooga, TN

Monday, November 24, 2014 – Sunday, March 29, 2015

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers