Aperture's Blog, page 192

September 8, 2013

About Face

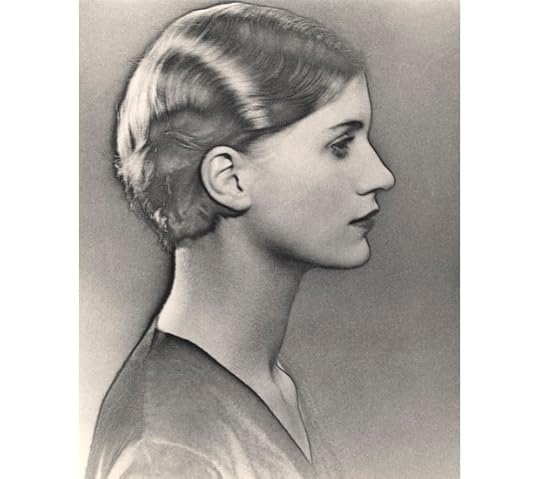

Man Ray, Solarized Portrait of Lee Miller, ca. 1929. The Penrose Collection; courtesy the Lee Miller Archives.

In his 1963 autobiography, Man Ray considers his long career and observes: “I photographed as I painted, transforming the subject as a painter would—idealizing or deforming as freely as does a painter.” This was a pragmatic freedom, which this versatile artist exerted also in his films and sculptural objects, indeed throughout his remarkably influential body of work.

Man Ray: Portraits, organized by Terence Pepper, curator of photographs at London’s National Portrait Gallery, is the first museum exhibition to focus on the artist’s photographic portraits, which constitute a hefty share of his creative output. With more than one hundred fifty prints, the show is divided into chronological segments that follow Man Ray’s career from 1916 to 1968, from New York to Paris to Hollywood and back, and from the artist’s earliest Dada-inflected experiments to images of society figures and movie stars, playful masqueraders, and a legion of artists, friends, and lovers.

Born Emmanuel Radnitzky in 1890, brought up in Brooklyn, Man Ray was eighteen and a student of painting when he first found his way to Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery, where he encountered the work of many of the most important and radical artists and photographers of the era. In 1915 he and Marcel Duchamp struck up a friendship that would lead to countless collaborations over the years, including many photographs by Man Ray of the French troublemaker in different guises—among those in the Portraits show are a 1916 image of Duchamp seated in a wicker chair, very much the upright, pensive young artist; the tiny, well-known shot of the back of his head shaved to reveal a shooting star; and a classic rendering of the mysterious and eternally straight-faced travesti known as Rrose Sélavy.

Man Ray left the United States in 1921 (complaining to his friend Tristan Tzara: “Dada cannot live in New York”)—following Duchamp and irresistibly drawn to what was then the vertex of the artistic universe: Paris. There his circle of acquaintances grew over the following two decades to include a stunning host of luminaries, and the Portraits exhibition is understandably weighted toward this period. Among the celestial litany featured here: Antonin Artaud, André Breton, Jean Cocteau, Salvador Dalí, Peggy Guggenheim, Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Dora Maar, Henri Matisse, Arnold Schönberg, Igor Stravinsky, and the full panoply of Surrealists, whose ranks Man Ray joined. (Particularly striking is the Johnny-Rotten-eyed Yves Tanguy, photographed in 1929.) The model Kiki de Montparnasse was Man Ray’s companion through most of the 1920s and the subject of hundreds of his photographs, including what may be his most famous, Le Violon d’Ingres (1924), in which her curvaceous back is transmogrified into a cello. (The inclusion of this and a few unnamed nudes in the exhibition may stretch the notion of “portraiture,” but the show’s rhythm is enhanced by their presence.)

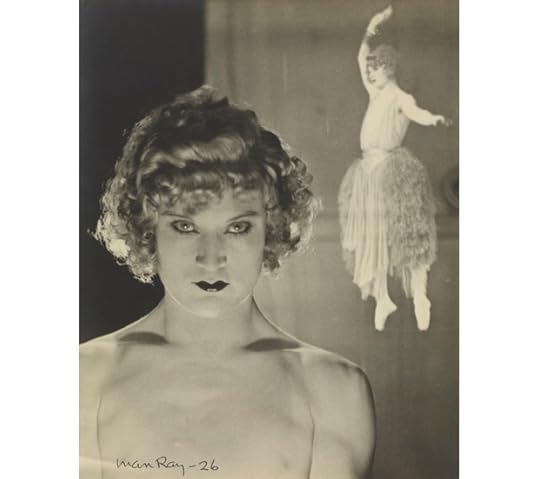

Many of Man Ray’s portraits were made on commission for journals, both avant-garde (New York Dada, Minotaure, Cahiers d’art) and mainstream (Vanity Fair, Harper’s Bazaar, even Ladies’ Home Journal). Pepper examines the artist’s interactions with these outlets in his catalog essay, and the exhibition sheds light on the degree of experimentation that was not only tolerated but apparently invited back then in the pages of even the most popular magazines. The forward-thinking editor of Vanity Fair, Frank Crowninshield, for example, published several of Man Ray’s innovative works in the early 1920s—among them a portrait of society maven Luisa Casati, her massive kohl-rimmed eyes blurred and doubled by a mistaken exposure (1922); the stolid Gertrude Stein at home in her Paris salon (1922); and a natty Pablo Picasso, looking into the lens with fathomless intelligence (1923). (Crowninshield also featured the artist’s rayographs—“A New Method of Realizing the Artistic Possibilities of Photography”—in 1922.) For Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar Man Ray provided society portraits, images of the literati (Virginia Woolf, the Sitwells, a dour Aldous Huxley), and performers (including the seductive 1926 image of cross-dresser Barbette, with dark bee-stung lips), as well as never-quite-conventional fashion shots. For a time, according to the artist’s biographer Neil Baldwin, “it was considered obligatory to stop in Man Ray’s studio and have yourself ‘done’ by him.”

Man Ray, Babette, 1926. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

The American model-turned-photographer Lee Miller came into Man Ray’s life in 1929 and made an indelible mark. She sought him out as a mentor in photography, and soon they became lovers. Together—through accident and experiment—they discovered the process of photographic solarization, which Man Ray would put to use in some of his best-known images, including the magnificent ca. 1929 profile portrait of Miller that serves as this exhibition’s centerpiece. His other photographs of Miller are by turns tender, elegant, creepy (particularly a 1931 picture of her sitting like a child on her stone-faced father’s lap), and profoundly sensuous. In a trio of images from 1930 she stands by a window, the dappled light streaming through it onto her half-naked body in an undulating grid. Even in this most classical of modes—the study of the female nude—Man Ray’s eye is restlessly inventive.

The artist moved to Hollywood in 1940 and stayed for a decade; he was surprised and disappointed that in the United States his reputation was based largely on photography alone—his work in painting, sculpture, and film had received far less attention. Many of his subjects from this period (Ava Gardner, Paulette Goddard, Dolores del Rio) are shown with the whipped-creamy, disaffected glam that was characteristic of the time and place. It seems clear that Man Ray was losing interest, or at least some of the visual potency that had energized his earlier images. He returned to Paris in 1951 and for the rest of his life focused more on painting than photography.

But the Portraits exhibition attests to the primacy of photography in Man Ray’s career. It was a medium that—particularly in the 1920s and ’30s, when he was at the height of his imaginative powers—allowed him great leeway, perhaps precisely because it had not yet been deemed one of the Lofty Arts. A supremely inquisitive and multitalented artist, in his photographic portraits Man Ray was not above engaging with editorial or fashionable conventions of his day—conventions that, in turn, were still capable of being shaped by him and others. He also had the temerity to toss protocol aside when the occasion was right, to “transform the subject,” blazing a path that was new, and entirely his own.

Man Ray: Portraits was presented at the National Portrait Gallery, London, February 7–May 27, 2013; it is on view at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh, through September 22; and will be on view at the State Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, October 14–January 19, 2014.

Diana C. Stoll is a writer and editor based in North Carolina.

September 6, 2013

Revisiting The Edge of Vision (Video)

From the beginning—The Edge of Vision author Lyle Rexer asserts—abstraction has been intrinsic to photography, and its persistent popularity reveals much about the medium. First printed by Aperture in 2009, The Edge of Vision: The Rise of Abstraction in Photography examines abstraction at pivotal moments in photography’s history, showcasing photographers who base their practice in some form of abstraction—from highly conceptual to more documentary approaches.

On the occasion of the 2013 reprint, Lyle Rexer recalls The Edge of Vision’s role in setting a historical context for abstraction, and the centrality of its rare and previously unpublished texts in illustrating the diversity of thinking that has gone on around issues in photography.

—

Join Lyle Rexer Monday, September 9 for The Edge of Vision Revisited: New Voices, a panel discussion with contemporary photographers Jessica Eaton, Niko Luoma, Yamini Nayar, and Mitch Paster, which will assess the growing importance of abstract practices, especially among younger photographers.

The Edge of Vision

The Edge of Vision$35.00

September 5, 2013

PhotoBook Awards 2013: New Arrivals Vol. 3

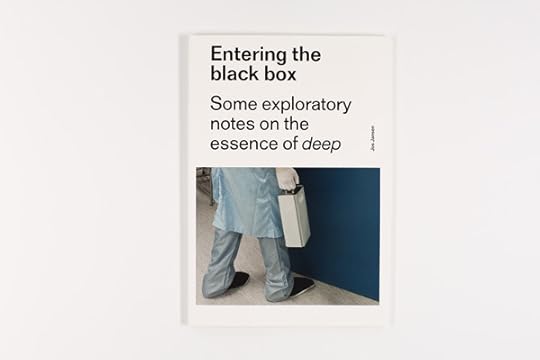

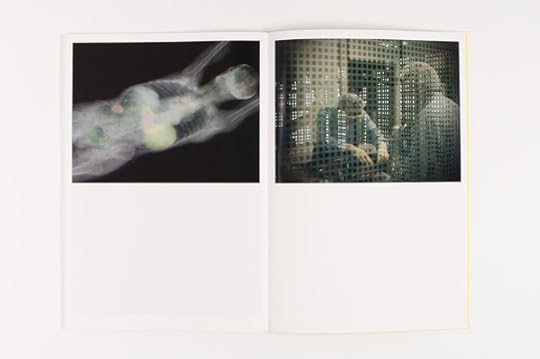

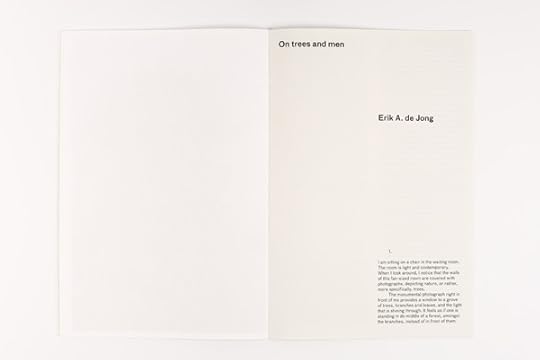

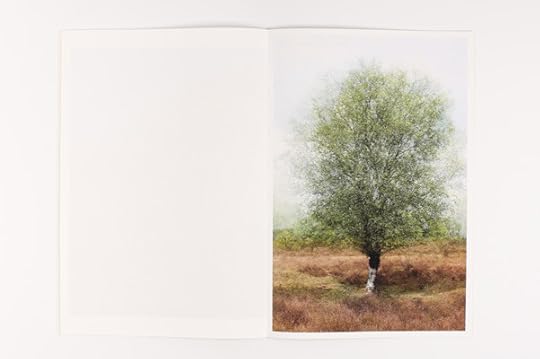

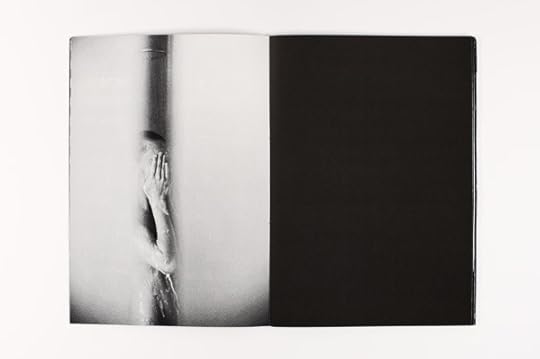

Entering the black box. Photographs by Jos Jansen.

Entering the black box. Photographs by Jos Jansen.

Entering the black box. Photographs by Jos Jansen.

Entering the black box. Photographs by Jos Jansen.

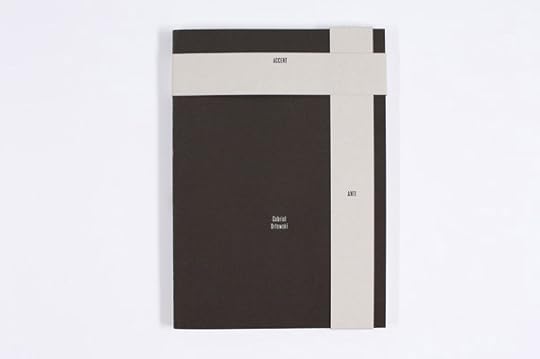

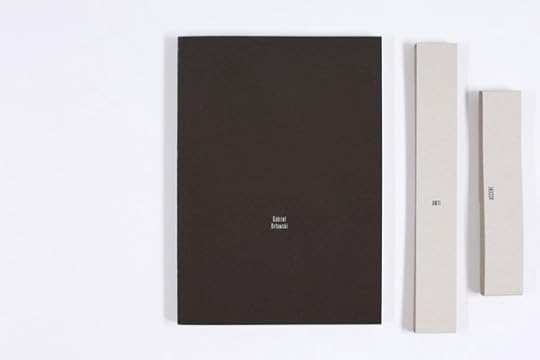

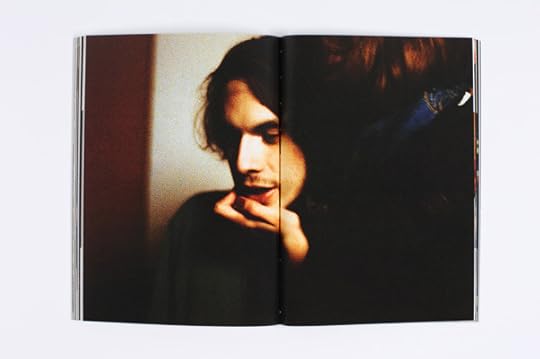

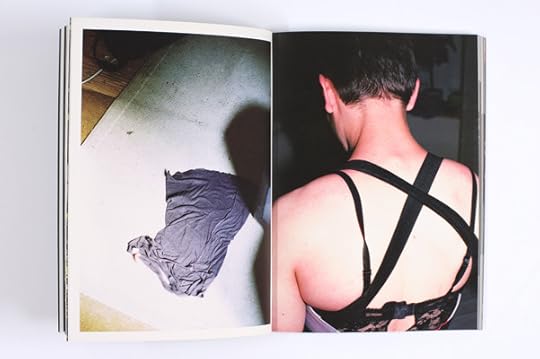

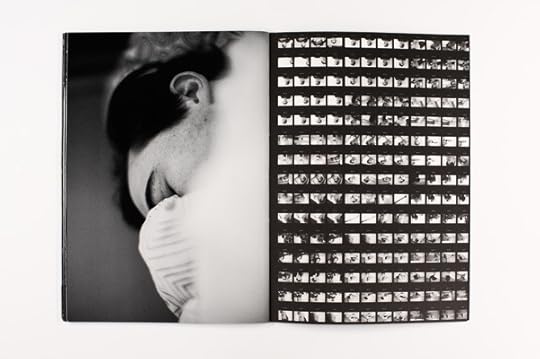

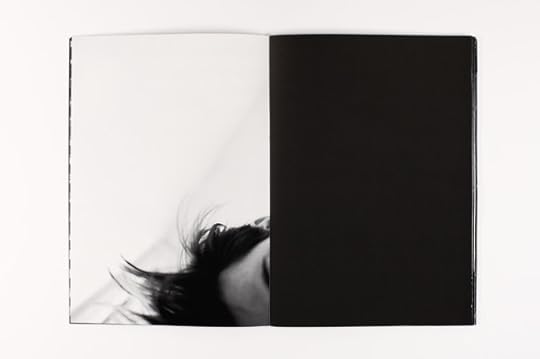

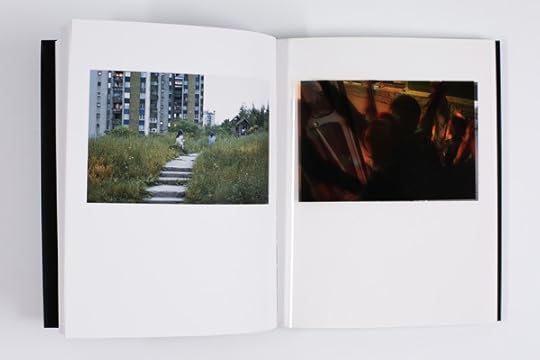

Anti-Accent. Photographs by Gabriel Orlowski.

Anti-Accent. Photographs by Gabriel Orlowski.

Anti-Accent. Photographs by Gabriel Orlowski.

Anti-Accent. Photographs by Gabriel Orlowski.

Anti-Accent. Photographs by Gabriel Orlowski.

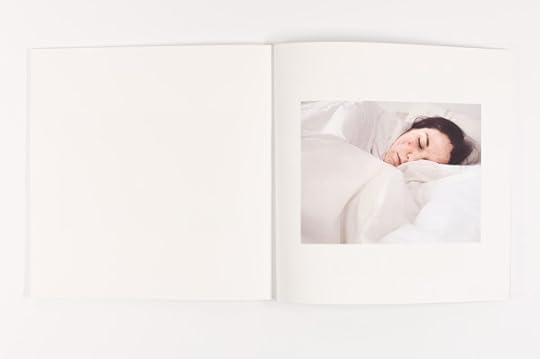

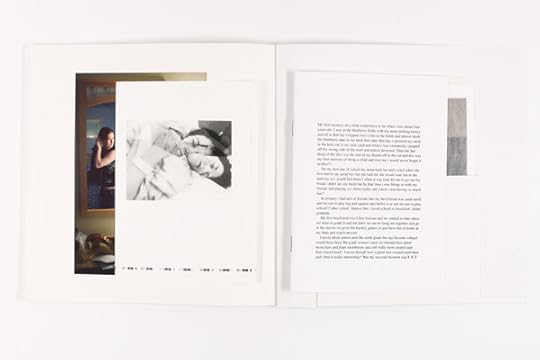

Live Through This. Tony Fouhse & Stephanie MacDonald.

Live Through This. Tony Fouhse & Stephanie MacDonald.

Live Through This. Tony Fouhse & Stephanie MacDonald.

Live Through This. Tony Fouhse & Stephanie MacDonald.

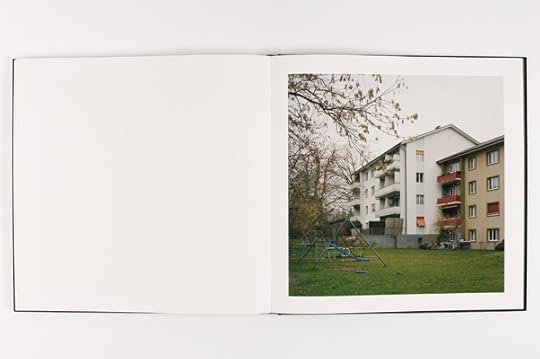

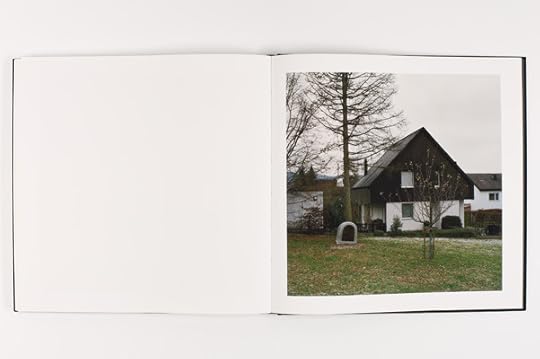

Mittelland. Photographs by Michael Blaser.

Mittelland. Photographs by Michael Blaser.

Mittelland. Photographs by Michael Blaser.

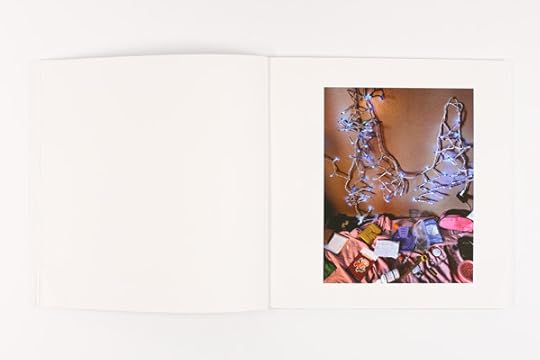

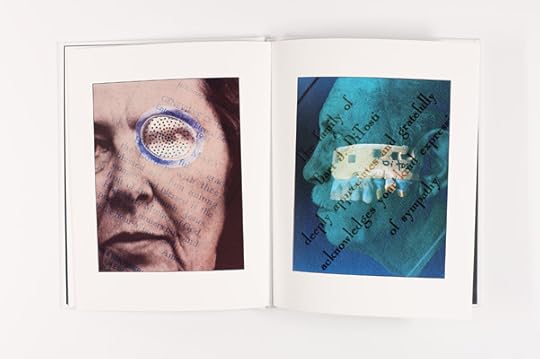

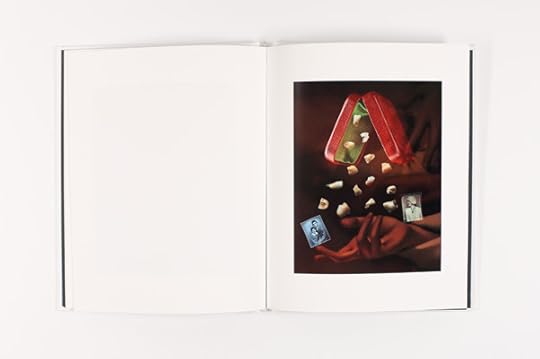

Personal Effects. Photographs by Roy DiTosti.

Personal Effects. Photographs by Roy DiTosti.

Personal Effects. Photographs by Roy DiTosti.

Personal Effects. Photographs by Roy DiTosti.

Mapping. Photgraphs by Kim Boske.

Mapping. Photgraphs by Kim Boske.

Mapping. Photgraphs by Kim Boske.

Mapping. Photgraphs by Kim Boske.

Mapping. Photgraphs by Kim Boske.

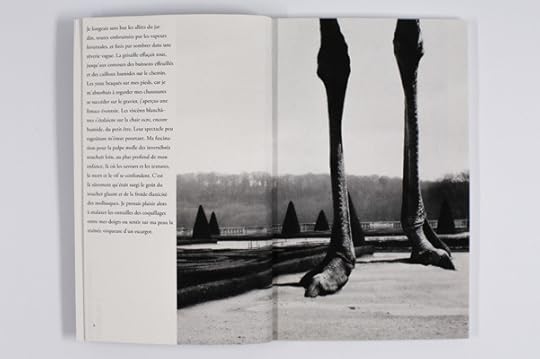

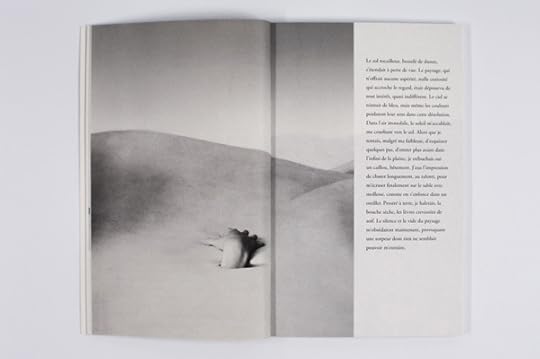

Sur Les Chemins Du Réel. Photographs by Jacques-Aurelien Brun.

Sur Les Chemins Du Réel. Photographs by Jacques-Aurelien Brun.

Sur Les Chemins Du Réel. Photographs by Jacques-Aurelien Brun.

Sur Les Chemins Du Réel. Photographs by Jacques-Aurelien Brun.

Sur Les Chemins Du Réel. Photographs by Jacques-Aurelien Brun.

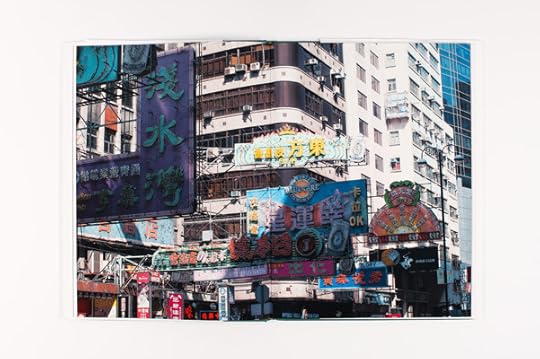

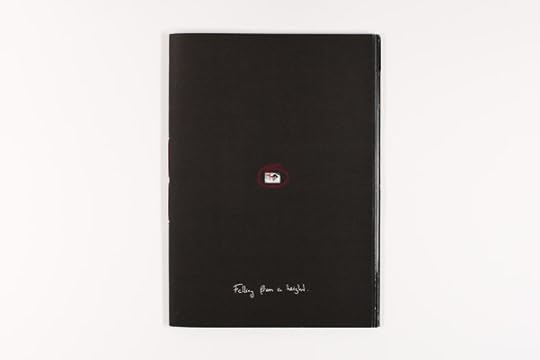

Falling from a height. Photgraphs by Martijn Berk.

Falling from a height. Photgraphs by Martijn Berk.

Falling from a height. Photgraphs by Martijn Berk.

Falling from a height. Photgraphs by Martijn Berk.

Falling from a height. Photgraphs by Martijn Berk.

Overnight Generation. Photographs by Italo Morales.

Overnight Generation. Photographs by Italo Morales.

Overnight Generation. Photographs by Italo Morales.

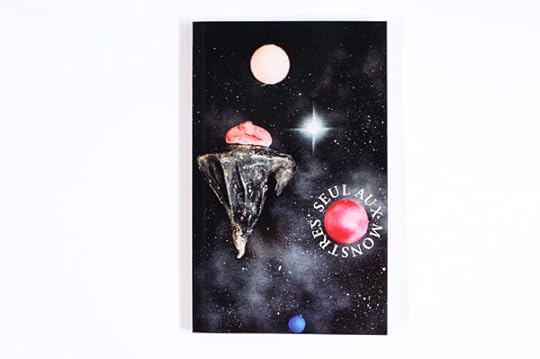

Seul Aux Monstres. Book by Brice Chatenoud & Fedora Parkmann.

Seul Aux Monstres. Book by Brice Chatenoud & Fedora Parkmann.

Seul Aux Monstres. Book by Brice Chatenoud & Fedora Parkmann.

Seul Aux Monstres. Book by Brice Chatenoud & Fedora Parkmann.

Seul Aux Monstres. Book by Brice Chatenoud & Fedora Parkmann.

Hay lugares en mí en los que nunca dejé que me visitaras. Photographs by Kemê Alicia Pellicer.

Hay lugares en mí en los que nunca dejé que me visitaras. Photographs by Kemê Alicia Pellicer.

Hay lugares en mí en los que nunca dejé que me visitaras. Photographs by Kemê Alicia Pellicer.

Hay lugares en mí en los que nunca dejé que me visitaras. Photographs by Kemê Alicia Pellicer.

We’re about to enter the final week of the Paris Photo—Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards 2013 call for entries, which remains open through Friday, September 13.

Here’s another chance to size up the photobook competition with a fresh selection of new arrivals in the First PhotoBook category, which includes recent publications by Kim Boske, Tony Fouhse & Stephanie MacDonald, and Misha Pedan.

Ready to submit? Just eight days remain. Visit the prize site for FAQ and full entry details.

Stay tuned to PhotoBook Awards news and streaming images via Twitter (@PhotoBookReview) and Instagram (@aperturenyc) in the months to come.

September 4, 2013

Survey Says

Humphrey Spender, Ashington—Washing in road between terraced housing, 1937–38. © Bolton Council, from the collection of Bolton Library and Museum Services; courtesy of the Mass Observation Archive.

Michael Wickham, The Kew Yead (Cow's Head), from Britain Revisited, 1960. © Wickham Estate; courtesy of the Mass Observation Archive, University of Sussex.

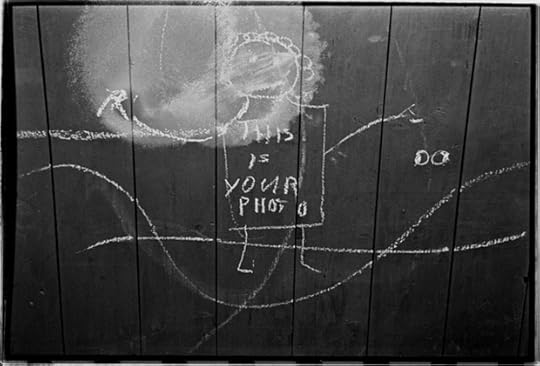

Humphrey Spender, Graffiti (This Is Your Photo), 1937–38. © Bolton Council, from the collection of Bolton Library and Museum Services; courtesy Humphrey Spender Archive.

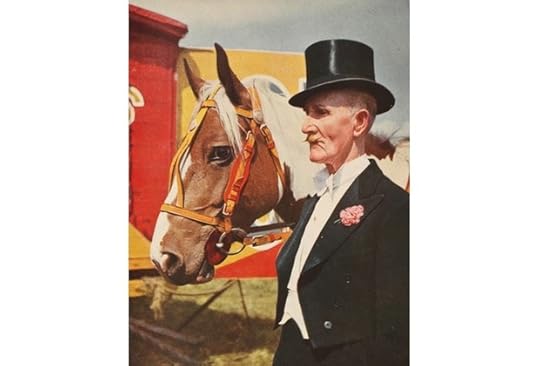

John Hinde, Ellis Cook, Ringmaster, with Trixie, the leader of the Liberty horses, from British Circus Life, 1948. © National Media Museum

Michael Wickham, MO surveys being taken outside the Britain Can Make It exhibition, 1946. © Wickham Estate; courtesy of the Mass Observation Archive, University of Sussex.

As was proclaimed in 1937, the year of its inauguration, Mass Observation (MO) was in part established to create an “anthropology of ourselves.” Understood as a radical experiment in social science, art, and documentary form, the MO was established by ornithologist and explorer Tom Harrisson, the journalist and poet Charles Madge, and the filmmaker Humphrey Jennings, soon accompanied by the photographer Humphrey Spender and later on by the less well-known photographers John Hinde and Michael Wickham. It sought to unpack both the banalities and mythologies of pre-war British life—with a problematic, but nevertheless utopian, desire to bring together science and art in the exploration of everyday experiences. It soon constituted a vast archive of collected data which ranged from anecdotal evidence gleaned in pubs and then meticulously recorded to questionnaires about the arrangement of ornaments on mantelpieces or the popularity of various pin-ups.

The MO’s expanding archive was conceived as a kind of vernacular museum of sounds, smells, foods, clothes, advertisements, newspapers—one largely created through texts, questionnaires, records, diaries, documents, and, of course, photographs. The current exhibition across two floors of the Photographers’ Gallery is dedicated to examining the role played by the latter in this archive. Indeed, while photographic documents were to wreak havoc with the rigorous and aestheticizing regimes of the traditional museum, the medium of photography and its messy complexities played a far more generative role in the sprawling, contradictory collections of MO. The first gallery relays this through the presentation of a jumble of photographic series, documents in vitrines, and other ephemera that focuses on life in rural England, Bolton, Blackpool, and London from 1937 to 1948. This includes a series of Spender’s black-and-white prints of working-class subjects made on the streets of Bolton in 1937–38. Spender’s characteristically surrealist eye alighted upon children’s chalk graffiti and provocative posters declaring “Truth Is Stranger than Fiction.” It’s a line that could also be taken as the photographer’s own manifesto. Indeed, exhibition curator Russell Roberts proposes this show in part as an attempt to grapple with the MO effort to produce “a new kind of realism.” The tensions between leisure and surveillance or between surrealism and sociology—certainly at the heart of artistic realism in the 1930s—have also come to be understood as dictating the central contradictions of the failed dream of MO: its instrumentalizing yet unscientific attempt at an anthropology from below.

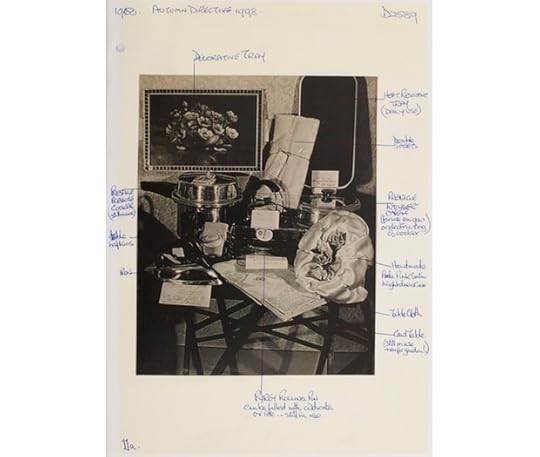

Taken from Present Giving and Receiving, 1998. © The Trustees of the Mass Observation Archive; courtesy of the Mass Observation Archive; reproduced with permission of Curtis Brown Group Ltd, London, on behalf of the Trustees of the Mass Observation Archive.

The MO project was also plagued by the obvious tensions between a group of largely middle-class observers and their working-class subjects. This is made clear at various points in the exhibition, but the potentially progressive aspects of MO are also highlighted in an engaging vitrine that brings together documentation of the establishment of art history classes by Northumberland miners and demonstrates the possibilities of working-class art education. The exhibition is most interesting when it tries to do more than neutrally illustrate such tensions. Too often it seems to skim these issues superficially, rather than historicize, critically examine, or politicize them. Despite the investment in presenting the unruly archive, there is also a latent aestheticization of some of its objects. For example, artist Julian Trevelyan’s shambolic suitcase, stuffed with various artistic materials, is presented very near the art-education vitrine (described above) as a kind of installation, nullifying any specific social tensions in favor of a rather poetic embrace of MO’s own mythologizing.

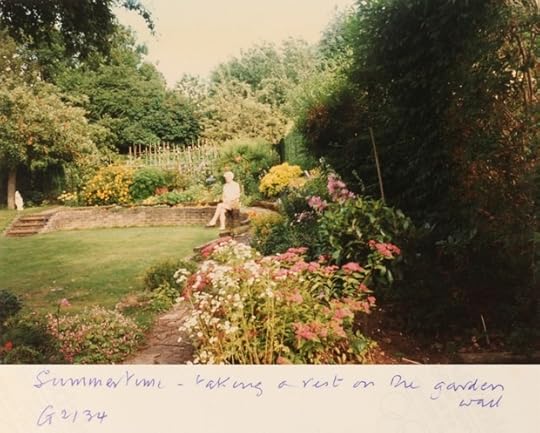

Alongside a careful investment in untangling photography’s role in the early history of MO, the major focus of this exhibition is to make concrete connections between the 1930s and the present day. In 1981, Mass Observation was re-inaugurated by the anthropologist David Pocock, and material from this new incarnation dominates the second-floor galleries. Volunteer participants’ photographic and textual responses to various “directives” from 1987 to 2012—encompassing their homes, gardens, and gift-giving habits, among other subjects—are presented on shelves behind Plexiglas screens. These include many fascinating images and offer social insights. They also suggest obvious connections between the kind of tensions that emerged between the public and private in the MO archive and those now endemic within social media and social networking. But it is not made clear enough that these later initiatives began after the original founders of the MO disbanded and the project was effectively privatized and transformed into a market research company. Such a critical examination of the MO might have required more ambition and a full three floors.

Taken from The Garden and Gardening, 1993. © The Trustees of the Mass Observation Archive; courtesy of the Mass Observation Archive; reproduced with permission of Curtis Brown Group Ltd, London, on behalf of the Trustees of the Mass Observation Archive.

As it is, so much more could have been done with the earlier material. For example, it would have been fascinating to know more about the fallout between Madge and Harrisson because of the latter’s decision to collaborate with the Home Intelligence Department of the Ministry of Information; or photography’s displacement in favor of graphic design in the frenzied desire to relay complex information in abstract form. (This is briefly alluded to in the show via diagrams by the bizarre Isotype Institution founded by Austrian émigrés Otto and Marie Neurath.) Further, so much is left unsaid about the unfolding exchange between photojournalism and the MO, or the relationship between psychoanalysis (also key to the MO) and photography. Both issues were central to the radical and reactionary new realism of the MO, as they must be to any attempt to properly reengage with its legacy.

Sarah James teaches in the History of Art Department at University College London. She writes frequently on photography and art for magazines including Frieze, Photoworks, and Art Monthly. Her book Common Ground: German Photographic Cultures Across the Iron Curtain was recently published by Yale University Press.

Mass Observation remains on view at the Photographers’ Gallery, London, until September 29.

Night Climbing

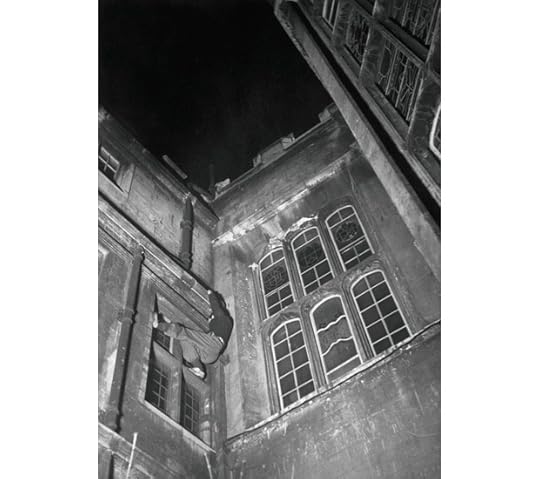

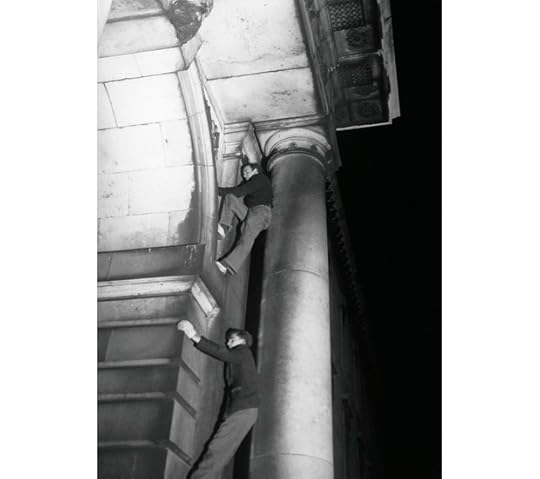

The Ivy Arch, St. John's College, St. John's Street. All photographs © Noël Howard Symington, The Night Climbers of Cambridge/Collection Thomas Mailaender.

Lion chimney (narrow climbing passage), Fitzwilliam Museum.

Note on the verso of the photograph, "The Face of [Gonville and] Caius [College]."

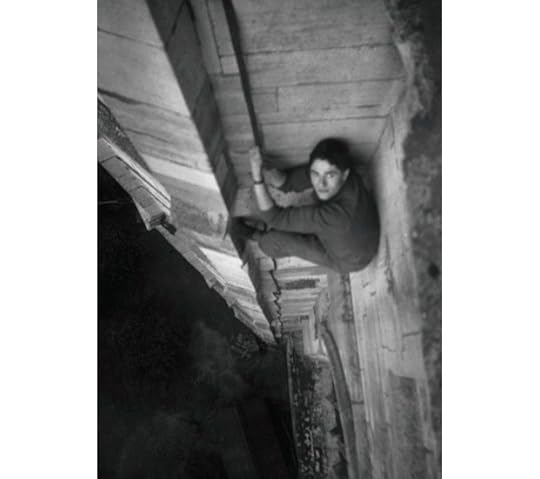

Trinity College, Fourth Court climb.

Back up Garrett Hostel Lane to Trinity Lane.

King's College Chapel (shown: Noël Howard Symington).

Why should Thomas Mailaender, a contemporary artist known for his impudent provocations, want to present us with photographs of students climbing on the roofs and walls of colleges at the University of Cambridge in the mid-1930s?

The Night Climbers of Cambridge was first published in 1937, by Chatto & Windus, a respectable publishing house in London. (The book, illustrated with photographs, was recently reissued by Oleander Press.) Mailaender, attracted by this peculiar venture, bought the original pictures and assembled them as a traveling exhibition. An odd choice, at first sight, but Mailaender has always been attracted by makeshift spoofs and charades. Nothing attracts him more than a tacky stunt where all the seams show. He is at home in the soft underbelly of the Internet, where self-satisfied egotists hog the limelight as they compete for delusional awards. In one noteworthy presentation he features as a beaming prize-winner holding on to outsize checks. He has a fondness for shaky facsimiles and rackety cover versions. His pictures of Algerian vehicles, piled high with possessions and discards, taken at the port of Marseille, look like nothing so much as a Joseph Beuys exhibition chanced upon in transit.

Mailaender is a saboteur. Bathos is his mode. His targets are credulity and complacency. He finds contemporary life, which includes contemporary art, ridiculous, pathetic, and entertaining. Long ago, before the night climbers plied their saucy trade on the walls of Cambridge, he would have been at one with Austrian writer Karl Kraus, who also appropriated pictures. Kraus’s leitmotif, you will remember, was the hanged body of the separatist Cesare Battisti displayed on a board in the moat of the Castello del Buonconsiglio in 1916 as part of a group portrait of executioners and accomplices all happy to be involved. Kraus saw it as a conclusive indictment of the Austrian Empire.

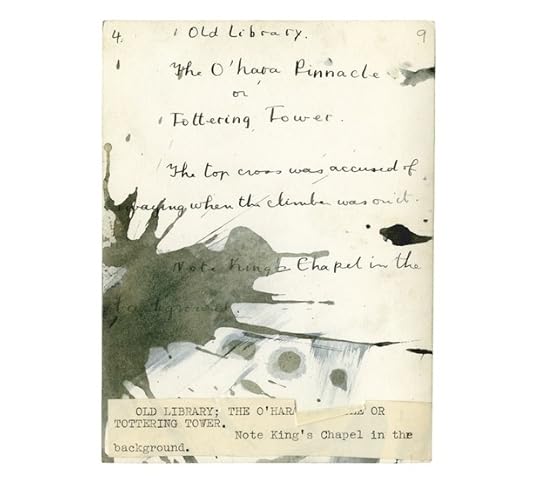

Note on verso of photograph, “Tottering Tower.”

The Cambridge adventurers fit Mailaender’s bill precisely. Maybe they meant no real harm. All the same they were climbing, which was a man’s business carried out regularly and hazardously on rock faces in the Lake District and in Wales—and sometimes in the Alps and on Everest where George Mallory and Andrew Irvine came stylishly to grief in 1924. In this context fooling around on the buttresses of King’s College or St. John’s couldn’t be taken seriously. The night climbers, headed by Noël Edward Symington, were, one might think, asking to be held in contempt.

They weren’t even doing anything very unusual, for any amount of famous names had amused themselves on those famous walls—Geoffrey Winthrop Young, for example, a famous alpinist and author of The Roof-Climber’s Guide to Trinity in 1899. What set the new generation apart was its interest in publicity. They photographed themselves in action, using flash—which drew the attention of passing policemen. They were, that is to say, interested in staged events, and at the time such events were popular in the British press: studio pictures, for instance, of films in the making and of early TV shoots at London’s Alexandra Palace.

“Tottering Tower,” Old Schools, Trinity Lane.

Meanwhile, in the real world the Spanish Civil War was in full swing—Guernica was bombed in 1937. In depressed Britain the government was at its wits’ end and the unemployed were up in arms—the famous Jarrow marches protesting unemployment and poverty also took place in 1937. The night climbers, cheeking the authorities and policemen, played their studiedly inconsequential part in this ghastly montage, and it is on this state of affairs that Mailaender has put his finger.

Ian Jeffrey is an art historian. Among many other projects, he was a major contributor to Thirties, a comprehensive survey of British art and design before the war, presented in 1979 at the Hayward Gallery, London.

Thomas Mailaender will exhibit The Night Climbers of Cambridge this September at Roman Road Project Space, London.

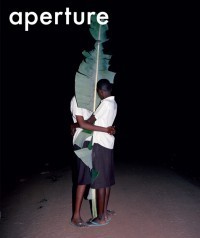

Aperture 212$19.95

Aperture 212$19.95

August 29, 2013

Gus the Bear

By Sylvia Plachy

This essay was first published in issue 206 of Aperture magazine (Spring 2012).

Stop and go: always on some journey. My bounty is a photograph or two. I remember what pulled me, an instant of clarity, a moment of perfection, but where was I? Beyond the edge it often fades to darkness: I don’t always remember the season or the place.

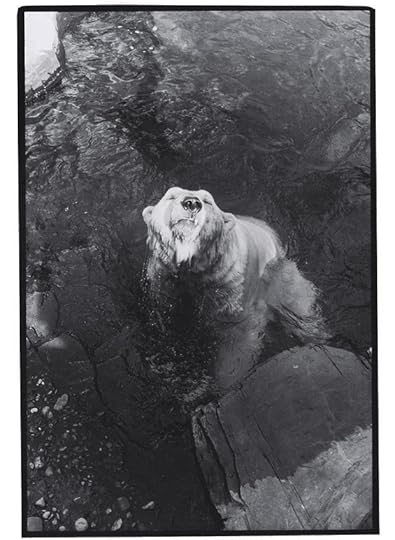

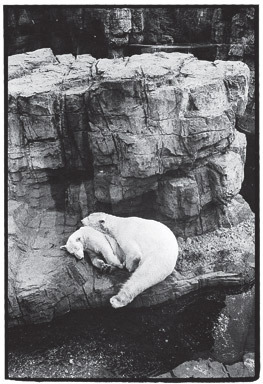

But with Gus and Ida, I do remember. It was 1988. They were new residents of the renovated Central Park Zoo, which finally saw the end of those cramped little nineteenth-century cages. Gus was brought from Toledo and Ida from Buffalo. They were both rambunctious and about three years old—preteens, in polar bear terms. I saw them through the glass wall of the pool gliding and frolicking in their white buoyant bulks. What joy! I saw them again in 1992 resting on a rock, quietly locked in an embrace.

Almost twenty years passed and then last summer, I read in the paper that Ida had died and Gus was now alone. The morning I went to see him, he was nowhere to be found. I asked a woman standing next to me if she knew where Gus was? “I think he is in mourning,” she said, as though mourning were a place—some dark cave— rather than a state of being.

When I came back that afternoon, I knew from the commotion and the way the children were squealing that Gus was present. And there he was, a glorious thousand pounds, with eyes half-shut swimming back and forth, as if pacing. Each time he reached the outer edge of the pool, and before he threw himself back again into the water, he pushed himself up, raised his bushy head, shook off the water and took deep whiffs of the air—looking for Ida, I thought. Poor Gus.

I tried to find someone who might have known Gus over the years. The zoo officials didn’t know, didn’t care, said they’d call me. The zookeepers were busy and too young. All channels were blocked. I turned to the chatter on the Internet. Through the noise and PR jargon and giddy superficiality, I gleaned that Gus had been depressed before; some called him “the bipolar polar bear.” He had had expensive psychiatric therapy, and occasional relief with toys and distractions. Ida joined him in 1987 and Lily, another female bear from Germany, came a few years later and shared the “enclosure.” Lily is gone, too; she died seven years ago.

Time stands still in photographs. Like the guys in John Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” the bears remain forever suspended in motion. Gus and Ida’s idyllic underwater dance, my illusion that all was well in some small corner of the world, was the truth only of that one second, a break in hours of tedium. Though there must have been many good moments and many visitors have been cheered, a zoo is a zoo: an enclosure is a prison. Outside, on the other hand, fear and hunger are frequent companions: Nature is not all it’s cracked up to be. Life anywhere is good only in spurts.

Now in this new portrait of Gus, he is alone. He is too old, I hear, to get used to yet another bear, his toys are really just plastic buckets, and as he continues his joyless swim at the dark side of the pendulum, he yearns for something—he doesn’t know what— perhaps not just his lost Ida.

As I leave the zoo, I read a sign on the fence: “Treat each bear as the last bear.” There is no source, no explanation. I am left with another riddle.

All photographs © Sylvia Plachy, 2012

Aperture 206$14.80

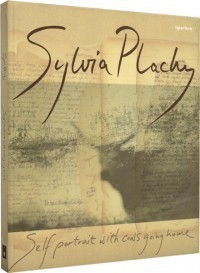

Aperture 206$14.80 Self Portrait With Cows Going Home

Self Portrait With Cows Going Home

$50.00

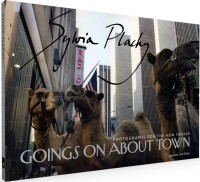

Goings On About Town

Goings On About Town

$29.95

August 28, 2013

Juan Garcia de Oteyza (1962–2013)

Juan García de Oteyza at opening reception of Eirik Johnson’s Sawdust Mountain at Aperture Gallery, 2010.

I am sad to report the death of Juan Garcia de Oteyza in Mexico City on Monday, August 26. Juan was director of Aperture Foundation from 2008 to 2010. During his tenure he increased our international presence in Brazil, Mexico, and Spain. He was a superb editor, an excellent diplomat, and a visionary. At the end of his life he was still working with Fundación Televisa and Aperture in editing a book on the French photographer Bernard Plossu.

Juan had a great career in publishing, in promoting the arts, and as a diplomat. He was director of Editorial Turner in Madrid (2000 to 2004) and later in Mexico City (2004 to 2007). He became Cultural Attaché of the Mexican Embassy, serving in Washington from 2007 to 2008, when he joined Aperture as director. In 1985 Juan founded Eridanos Press to publish contemporary literature of non-English writers in English. From 1996 to 2000, he was director of the Mexican Cultural Institute in New York. He worked with the Museum of Modern Art on the first retrospective of Manuel Álvarez Bravo and also organized a tribute to the poet and Nobel Prize winner Octavio Paz at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. I worked closely with Juan, and his enthusiasm, knowledge, and charisma will be missed by members of his family, friends, and all of us at Aperture.

—Celso Gonzalez-Falla, Chairman of the Board.

August 24, 2013

Redux: Italo Calvino’s “The Adventure of a Photographer”

Italo Calvino, Paris, January 1984. Photograph by Ulf Andersen/Getty Images.

Italo Calvino, the Italian writer, began his tribute to Roland Barthes in La Repubblica with a horrific image of defacement. Barthes, Calvino noted, had been disfigured beyond recognition by the accident that had killed him on February 25, 1980, lying unidentified for hours in the hospital. This reminded Calvino of the book that he was reading only a few weeks before its author’s death: La Chambre Claire, or Camera Lucida, as it is better known today. Sitting down to write the tribute in April 1980, Calvino was struck by how Camera Lucida was more a book about love and death than about photography. It made him think of Barthes lying dead, “name unknown,” in Salpêtrière, “the frail and anguished link with his own features . . . suddenly torn as one tears up a photograph.”

Most of us find it strangely difficult to tear up a photograph, even when it is of an inanimate object, a landscape, or someone we do not know. We find ourselves stopping short of the imagined violence of the act, finding it much easier to tear up, say, a letter. The flea markets of Europe, as Tacita Dean discovered while making Floh (2001), are full of photographs that have been abandoned rather than destroyed. Yet, the tearing up of photographs as an extreme gesture that fuses madness and violence forms the climax of a story written by Calvino in the mid-1950s. It is called “The Adventure of a Photographer” and became part of Difficult Loves, a collection of finely reflective short stories, or “adventures,” each involving a different figure: a poet, a reader, a traveler, a soldier. Written more than two decades before Camera Lucida and Susan Sontag’s On Photography, Calvino’s “The Adventure of a Photographer” reads, to me, like a far more contemporary parable about the medium than those canonical texts by the Sontag-Barthes-Benjamin trinity that remain mandatory for serious photographers or writers on photography today.

Calvino’s photographer, Antonino, is a “hunter of the unattainable.” Initially reluctant to pick up the camera his friends use so avidly, Antonino’s relationship with photography starts as a pursuit of “life as it flees,” but soon turns into a “passion difficult to put up with”—a state of isolation caught between obsessiveness and a pervasive sense of loss; everything that is not photographed is lost. Antonino realizes very quickly that what lurks in his “black instrument” is nothing but a kind of madness. This madness is a forking path. One path beckons outward, toward the doomed and impossible desire to document everything that exists and happens before it is lost forever. The camera must record all reality, all history; only then would it begin making some sort of crazy sense. The other one leads inexorably within, into the labyrinths from which the eyes, windows of the soul, look at the world outside. Yet, in his studio, as the photographer focuses the camera on his model, her body forced into a sequence of grotesque poses, the two roads, inner and outer, seem to cross again “in the glass rectangle.” It is “like a dream, when a presence coming from the depth of memory advances, is recognized, and then suddenly is transformed into something unexpected, something that even before the transformation is already frightening, because there’s no telling what it might be transformed into.” “Did he want to photograph dreams?” the half-mad photographer asks himself, and the suspicion strikes him dumb.

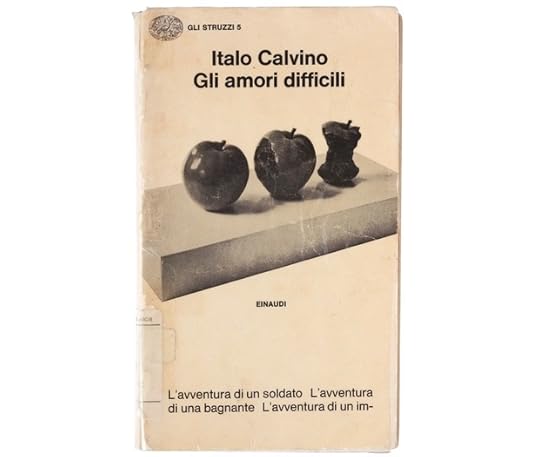

Italo Calvino, Gli amori difficili (Difficult Loves) (Einaudi, 1970). Courtesy Fondazioni Luigi Einaudi, Turin.

In recording Antonino’s descent into a psycho-pathology of everyday life driven by the camera, Calvino shows how photography could lead, through an obsession with capturing the real, toward the unhinging of the mind from that very reality. It is, paradoxically, the compulsion to document that dooms photography to transgress the limits of the visible, opening up a terrain that belongs to the imagination rather than to empirical certitude. In his tribute to Barthes, Calvino described the capacity of language to speak about things “that are not”: this was its fundamental difference from photography. Yet, in this story, Antonino takes photography close to the inwardness of the imagination unshackled from the real, and to the irreducible logic of memory, dream, and fantasy. This is also the domain of fiction and, dare one say, of art. It is the rigorous unruliness of fiction— rather than the discursiveness of theory, or the objectivity of history—that becomes the mode in which Calvino fathoms the meaning and possibilities of photography. It is fiction that rescues photography from the risk-averse middle path of empiricism by toppling the eye, and the eye’s mind, into the abyss of the invisible. As he lets go of the hope of capturing with his camera the “essence” of the woman he desires, Antonino stumbles upon his art’s most difficult secret: “Photography has a meaning only if it exhausts all possible images.”

Aveek Sen writes usually from Calcutta. In 2009, he was awarded the Infinity Award for Writing on Photography from New York’s International Center of Photography

August 23, 2013

Outside In

By Prajna Desai

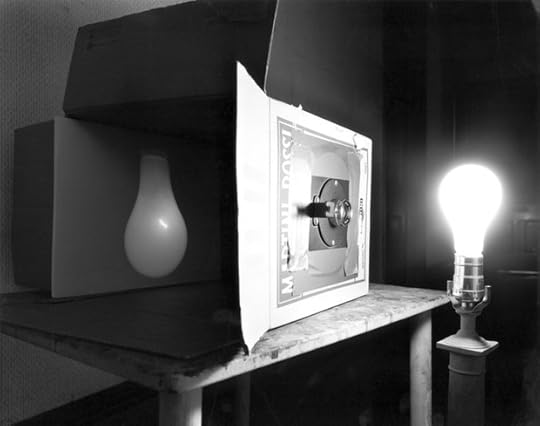

Abelardo Morell, Light Bulb, 1991. All images © Abelardo Morell and courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago.

Photographer Abelardo Morell is a cunning revivalist, or so it would seem from Abelardo Morell: The Universe Next Door. This retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago juxtaposes work inspired by nineteenth-century cameraless techniques with an impressive assortment of straight photography made over the last twenty-five years. Variety aside, the exhibition is mainly remarkable for the pictures made by camera obscura, the pre-photographic optical principle behind Morell’s most invigorating work since 1991.

On a basic level, the camera obscura operates like the human eye. Light entering a hole in a closed box projects onto the box’s interior an upside-down image of the world. In the case of the eye, the brain realigns the image to conform with reality. Early in his career, Morell built and photographed a camera obscura and the image it projected with a conventional camera placed outside the box. The resulting work, Lightbulb (1991), isolated an important characteristic of his visual vocabulary: an understated surrealism that reconsiders elementary photographic rules by inflecting a single frame with multiple perspectives and affects.

This emphasis on uncanny juxtaposition became more concrete when Morell enlarged the scope of his project and began using natural light. Manipulating a room in his house, this time with the camera inside, Morell shot only the image projected through the pinhole. Camera Obscura: Houses Across the Street in Our Bedroom, Quincy, Massachusetts (1991) required a prolonged exposure of eight hours. In the picture, the lone but massive bed seems to be dreaming. What is it dreaming? Perhaps the image above of several shrunken, dim, and upturned houses. Seminal for Morell, the picture established a symbolic affinity between private or interior space and the camera obscura; for him, both have the power to transform and subdue the outside world. In subsequent years, the camera obscura image invades blank areas, often walls and beds, as if they were screens. Sometimes it even belittles the external world. In Camera Obscura: The Sea in Attic (1994), the projection of the swirling sea becomes a dismal stain on the architectural space, itself self-assured and seductive.

Abelardo Morell, Camera Obscura: The Empire State Building in Bedroom, 1994.

As singular as they are, these camera obscura pictures fit neatly into an overarching view. For Morell, photography is not only a magical realm, as reflected in the exhibition’s title, which borrows from an e.e. cummings poem: “listen;there’s a hell / of a good universe next door;let’s go.” The everyday world is also inherently photographic—that is, ordinary things can unpredictably function as camera lenses. Both of these ideas repeat dogmatically throughout his work. For evidence of his first idea, one might look among his pictures of domesticity that frequently incorporate the silhouette of the classic American house. In Laura and Brady in the Shadow of Our House (1994), Morell’s children loll idly amid scratches in the dirt representing windows, a door, and a picket fence. Here, the shadow-house dignifies the scratched drawing as an architectural elevation, which in turn “house trains” the outdoor space, giving it the intimacy of a real home but the pixie charm of a dollhouse.

Morell’s second idea about lenses embedded everywhere in the world is encapsulated by a different picture made the same year. Shadows During Solar Eclipse (1994) seems fairly ordinary until we learn that the pockmarked silhouettes edged with light and covering the ground are so many pint-sized images of the semicircular sun in eclipse. Hundreds of intervals between the leaves above take up the role of pinholes. Though proving Morell’s argument about the world’s photographic nature, the picture also highlights an unfortunate feature of his work in general. The fascination with optical workings that uniformly infiltrates his oeuvre does not always produce pictures of great visual interest.

In 2005, Morell switched to color film and replaced the pinhole with a diopter lens to shorten exposure time and sharpen focus. A prism located within the camera obscura righted the projection. Upright Camera Obscura: The Piazetta San Marco Looking Southeast in Office (2007) is a later outcome of these modifications, by which the unprecedented clarity of the diopter projection allows the outside world to both dominate and solidify. In Morell’s earlier pictures, the projection of exterior architecture has a spectral quality. Here, it has the robustness of fact. Yet what stands out most is color itself, which saturates every aspect of the image. In Camera Obscura: Garden With Olive Tree Inside Room With Plants, Outside Florence, Italy (2009), color flattens the imaginative difference between the plushness of the natural verdure outside and the greenhouse artifice inside. Thus distracting from Morell’s previous emphasis on the strange encounter between incongruent worlds, color also changes the psychology of his camera obscura format. It goes from eerie fascination, earlier expressed by the tension between grayscale tones, to straightforward pleasure. Put simply, everything now looks equally, ecstatically beautiful.

Abelardo Morell, Tent Camera Image On Ground: View Looking Southeast Toward The Chisos Mountains, Big Bend National Park, Texas, 2010.

In 2010, Morell took the camera obscura outdoors. At Big Bend National Park in Texas, he erected a tent camera fitted with a periscope lens that directed the projected image onto the ground. Whereas nineteenth-century photographers used tent cameras to create precise records of the American West, Morell’s pictures took a pictorially adventurous route. Projecting a colossal elevation at a remove of miles onto the dirt at his feet distorted natural scale. Gravel, stone, and shrub pop out in pictures such as Tent Camera Image on Ground: View Looking Southeast Toward the Chisos Mountains, Big Bend National Park, Texas (2010). They are enlarged protoplasmic blotches among the miniaturized projections of gigantic limestone canyons and mountains. Dust powders the plane as irregular speckles. When Morell staged the tent in the urban outdoors of New York, mildly textured sidewalks or uniformly coarse park ground gave the projections a deliberately stippled appearance. The implied dialogue with late-nineteenth-century pointillism is particularly apparent.

Morell’s photographic wizardry is undoubtedly impressive, particularly in the tent-camera pictures. Yet his tenet of “abiding by the rigor of reality,” which he explains with a Zen saying about going to a tree if you want to write about it, would be admirable if the pictures exceeded the sum of their visual effects. Sadly, the plein-air camera obscura pictures fail to shake this trap; their pictorial highlights are simply equivalent to their optical tricks.

Pranja Desai is a writer of fiction and nonfiction currently based in Mumbai.

Abelardo Morell: The Universe Next Door is on view at the Art Institute of Chicago through September 2. For more information, click here.

August 20, 2013

Aperture #212 (Fall 2013)—Editors’ Note

Olaf Breuning, Pattern People, 2013. Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Over the course of her career Helen Levitt found no shortage of off-the-cuff comedy playing out in New York’s streets. It’s fitting then that Tim Davis shared Levitt’s images with his photography students as examples of both levity and joy in the medium. Davis, in a diagnosis in these pages of “ photogeliophobia”—fear of funny photographs—observes that photographers have tended to downplay their sense of humor while responding to a world full of unexpected hilarity. Famously laconic, Levitt didn’t comment much on her work— maybe explanation took the fun away—but she did once admit to “looking for comedy more and more,” a quality she often found by surreptitiously photographing children at play.

This issue is loosely organized around the title Playtime, a nod to French filmmaker Jacques Tati’s brilliant 1967 send-up of the absurdities of modern living. Tati’s signature pokerfaced slapstick is felt across these pages. Erwin Wurm, speaking of his jarringly illogical One-Minute Sculptures and other works, remarks that he views humor as a vehicle to arrive at other meanings, including pathos. With her Drape series, Eva Stenram digitally rewires vintage pinup pictures, performing a kind of détournement that takes the wind out of the original images’ erotic charge. Italian polymath Bruno Munari—who began his artistic career as a Futurist painter in the 1920s—also worked as an illustrator, designer, and inventor, and brought all these talents to bear upon his photographs, which are performative, inventive, and unabashedly fun.

What are games and play without rules? Invented, often arbitrary rules governed the work of the Conceptual artists of the 1960s and ’70s discussed by Robin Kelsey: figures such as John Baldessari and Eleanor Antin, who responded to a tumultuous, uncertain era—and to the machismo and self-importance of “serious” art—by making games and clever gags a purposeful artistic strategy. More recently, Maya Rochat, one of the artists in the portfolio of young Swiss photographers assembled by Bruno Ceschel, suggests that “ non-seriousness is a refusal to fall asleep.” This group of artists exchange austerity and formality for absurdity and humor, freely mixing media to create brash and messy images fueled by a curiosity about how the medium can be stretched and explored. A number of these figures are associated, as instructors or one-time students, with two of Switzerland’s major art academies.

Schools, clearly, can serve as incubators for experimentation, playful thinking, and productive distraction. Over the last few years, James Mollison has photographed the anarchic theater that unfolds each afternoon across the globe’s schoolyards. Campus antics are of course nothing new, as we see in a portfolio from the 1930s showing a group of daredevil students at the University of Cambridge performing a precursor to parkour: scaling the walls and turrets of King’s and Trinity Colleges as though they were alpine slopes. Their dizzying images are reminders of how vertigo can remove us from the everyday, that play is often purposeless—sometimes undertaken primarily for the benefit of a spectator. Jo Ann Callis’s darkly physical images, published here for the first time, suggest a game of what does-this-feel-like? enacted for the photographer.

Central Archway Gibbs building, King’s College, ca. 1937. © Noël Howard Symington, The Night Climbers of Cambridge. Collection Thomas Mailender.

In his 1961 book Man, Play, Games, philosopher Roger Callois noted that “secrecy, mystery, and even travesty can be transformed into play activity.” Sophie Calle, an artist celebrated for her clever, mischievous projects, discusses her new series revisiting the brazen theft of artworks from Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. In her conversation with Melissa Harris, Calle teasingly suggests of her “documentary” project: “Maybe everything is invented. . . . Who knows?” Inversely, Japanese photographer Kazuyoshi Usui offers us admittedly fictional images that appear to be real, spinning Japan’s bygone Showa era into a pink-tinged future that never really happened. Poet Frances Richard speaks with Christian Marclay about his snapshots of found musical notation, repurposed and then literally played by musicians. Marclay notes that his approach to photography “includes a sense of playfulness because you’re not sure what the consequences are going to be.” This inquisitive spirit unites the many guises of play found in this issue—play as games, as fictions, as digital simulations; role-playing, playing music, and so on. The beauty of play, it seems, is that you never quite know where the game will take you.

After this issue, Diana C. Stoll, Aperture’s longtime senior editor, will be moving on to pursue personal projects. We will greatly miss Diana’s endless wisdom, brilliant editing, and impeccable eye. We wish Diana the best of luck in her new endeavors, but we don’t consider this a good-bye as we look forward to having her as a writer in our pages.

—The Editors

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers