Aperture's Blog, page 189

October 24, 2013

Rupture, Reconnection: The Photography of Eikoh Hosoe (Video)

On October 9, Aperture Foundation and Miyako Yoshinaga Gallery hosted a panel discussion on the career and influence of Eikoh Hosoe, widely acknowledged as a pioneer of expressionistic post-World War II Japanese photography. Spanning over fifty years, Hosoe’s work explored the human body’s physicality as a subject that reveals a shifting interior landscape of dreams and desires.

Panelists Russet Lederman, Kunié Sugiura, and Charles Traub shared their knowledge as researchers, critics, and fellow artists on Hosoe’s work from the 1960s onward. Traub and Sugiura concentrated on the influence of Hosoe’s work on their generation, while Lederman introduced an overview of Hosoe as a post-war photographer, focusing on Hosoe’s role as a teacher and catalyst for an East-West dialogue. Alongside Hosoe’s photographs, an excerpt from his 1960 film Heso to genbaku (Navel and A-Bomb) was shown during the discussion.

This panel was made possible with the support of Miyako Yoshinaga Gallery, and was presented in conjunction with that gallery’s exhibition, Eikoh Hosoe: Curated Body 1959–1970, which was on view September 12–October 19.

View “The Photography of Eikoh Hosoe, Part 2, Part 3, & Part 4” on Vimeo.

—

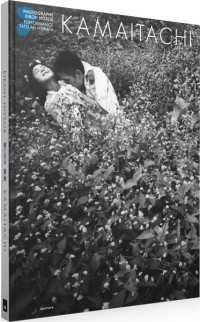

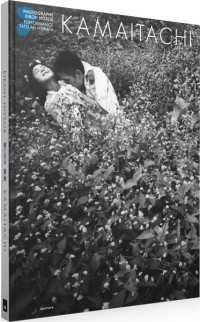

Eikoh Hosoe’s work is now available in Japanese Photobooks of the 1960′s and 1970′s (Aperture, 2009), Kamaitachi (Aperture, 2009), and in the Awakenings Portfolio. Kamaitachi

Kamaitachi

$60.00

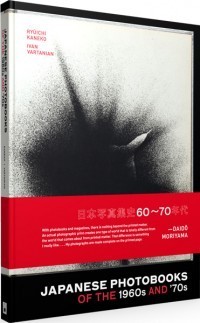

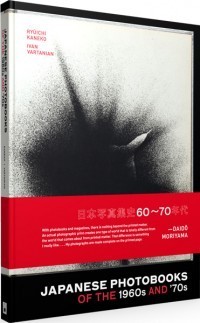

Japanese Photobooks of the 1960's and 1970's

Japanese Photobooks of the 1960's and 1970's

$75.00

Awakenings Portfolio

Awakenings Portfolio

$3,000.00

Rapture, Reconnection: The Photography of Eikoh Hosoe (Video)

On October 9, Aperture Foundation and Miyako Yoshinaga Gallery hosted a panel discussion on the career and influence of Eikoh Hosoe, widely acknowledged as a pioneer of expressionistic post-World War II Japanese photography. Spanning over fifty years, Hosoe’s work explored the human body’s physicality as a subject that reveals a shifting interior landscape of dreams and desires.

Panelists Russet Lederman, Kunié Sugiura, and Charles Traub shared their knowledge as researchers, critics, and fellow artists on Hosoe’s work from the 1960s onward. Traub and Sugiura concentrated on the influence of Hosoe’s work on their generation, while Lederman introduced an overview of Hosoe as a post-war photographer, focusing on Hosoe’s role as a teacher and catalyst for an East-West dialogue. Alongside Hosoe’s photographs, an excerpt from his 1960 film Heso to genbaku (Navel and A-Bomb) was shown during the discussion.

This panel was made possible with the support of Miyako Yoshinaga Gallery, and was presented in conjunction with that gallery’s exhibition, Eikoh Hosoe: Curated Body 1959–1970, which was on view September 12–October 19.

View “The Photography of Eikoh Hosoe, Part 2, Part 3, & Part 4” on Vimeo.

—

Eikoh Hosoe’s work is now available in Japanese Photobooks of the 1960′s and 1970′s (Aperture, 2009), Kamaitachi (Aperture, 2009), and in the Awakenings Portfolio. Kamaitachi

Kamaitachi

$60.00

Japanese Photobooks of the 1960's and 1970's

Japanese Photobooks of the 1960's and 1970's

$75.00

Awakenings Portfolio

Awakenings Portfolio

$3,000.00

Larry Fink

“. . . my developing identity was ensnarled with the camera, its natural power to encode and communicate that which was in front of me and that which was within me . . . “

—Larry Fink

Larry Fink’s photographs merge style, vision, and content so seamlessly that their meaning strikes us as given: something known and shared—an unequivocal truth about what things looked and felt like there in front of the camera. The art of this lies in Fink’s ability and willingness to penetrate the scene at hand, even when the politics may not be to his liking. Join Larry Fink for a workshop that will explore the relationship between subject and photographer, style and meaning. Fink has been a professor at Yale University School of Art, New Haven; Cooper Union School of Art and Architecture, New York; Parsons School of Design, New York; and Tyler School of Art, Temple University, Philadelphia. Currently he is a tenured professor of photography at Bard College. His work has been widely exhibited in the United States, including solo exhibitions at Light Gallery, New York; Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge; Museum of Modern Art, New York; and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Included in the workshop will be a portfolio review followed by an individualized assignment. Students will have three weeks to complete the assignment and will then return for a group critique led by Fink.

Refund / Cancellation Policy for Aperture Workshops

All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date if the workshop is under-enrolled, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

The post Larry Fink appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Protected: Larry Fink

This post is password protected. To view it please enter your password below:

Password:

October 23, 2013

Robert Cumming in Conversation with Sarah Bay Williams (Video)

On October 1, as part of the Aperture Magazine Live series, photographer Robert Cumming was joined in conversation by writer and curator Sarah Bay Williams on the subject of humor, absurdity, and perceptual play in Cumming’s 1970s photography. Currently working on a book about Cumming’s photography and art, Williams wrote on the subject for the “Curiosity”-themed Summer 2013 issue of Aperture magazine.

Cumming shared a slideshow of his 1970s work that played with visual perception. He would present a photograph followed by a second photograph of the same scene—but with a wider frame that revealed the behind-the-scenes deception of the previous image. These images showcased Cumming’s ability to manipulate the physical world and trick the eye into believing his fantastic environments were reality.

With the ability to illuminate the absurd through photography, Cumming kept his audience amused and intrigued. In creating these images, Cumming found photography to be the perfect medium through which to exercise his fascination with and the tension between reality and fiction, and between the commonplace and the fantasy.

View “Robert Cumming in Conversation with Sarah Bay Williams, Part 2” on Vimeo.

—

Aperture magazine issue #211 is now available. Aperture 211$19.95

Aperture 211$19.95

October 22, 2013

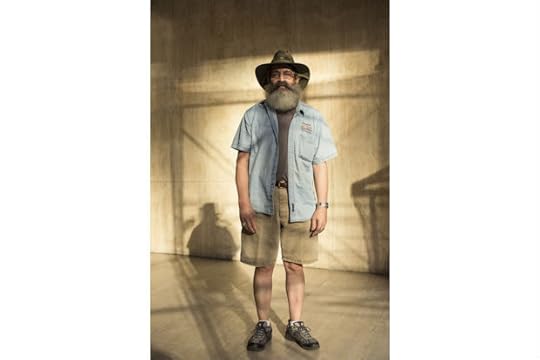

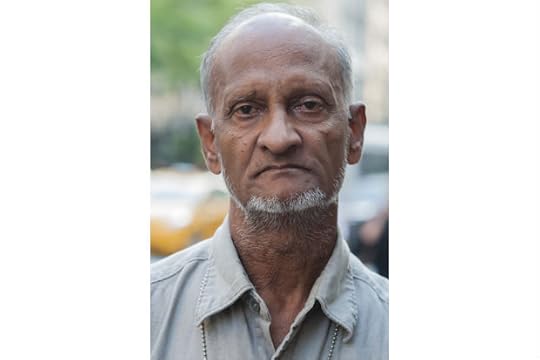

Recap: Workshop with Richard Renaldi

___

___

___

© Michael Joseph

© Oliver Parini

© Robin Odland

© Morgan Sloan

© Bill Kotsatos

© Ahmer Inam

© Jo Wayman

Richard Renaldi led an energetic workshop at Aperture on October 5 and 6 called Strangers in New York: Photographing People. He shared methods for photographing strangers—a focus in his own practice, such as in his series Touching Strangers. In the classroom, Renaldi provided students with subtle strategies for engaging with members of the public. Students then traveled to Herald Square, where they had the opportunity to work closely alongside Renaldi as they made portraits of people in the street. The course continued with the review of each student’s work and a discussion of techniques for improvement. The workshop was a valuable lesson in a fundamental photographic paradigm, the street portrait.

From the students:

“Loved this workshop. Richard was a great instructor and provided a lot of useful advice for making better portraits.”

“The one-on-one time that Richard spent with each of us on location was incredibly valuable.”

—

To find out more about workshops and classes at Aperture, click here.

Figure and Ground

Figure and Ground

$45.00

Christine, 2003

Christine, 2003

$600.00

October 21, 2013

1/1 Preview: Todd Hido, Study for Excerpts from Silver Meadows

Todd Hido, Study for Excerpts from Silver Meadows, 2013.

Todd Hido’s Study for Excerpts from Silver Meadows (2013) is a single work comprised of individual pictures, ranging from Hido’s signature suburban street views to sultry portraits and atmospheric landscapes. The prints in Study, which is available as part of Aperture’s 1/1 Auction, were drawn from Hido’s recent book Excerpts From Silver Meadows (2013), a highly personal, extended photo-essay about the artist’s hometown. Now mounted on board, they have been treated like snapshots; held, touched, bent, burned, and looked at. Text enters the array through pictures of signs reading, “WELCOME HOME,” “EXIT,” and “The End.” The loose grid of images, intuitively arranged, sketches scenes lifted from a rural American novel: furrows in a snowy field are set alongside a child’s-eye-view of a woman leaning through a car window; a phone left off its hook on a carpeted living-room floor is coupled with a portrait of a football player from a high-school yearbook; a nude reclining within the bare confines of a motel room is contrasted with an intricate study of a lakeside exterior.

These pairings draw a photographic cartography heading west, specifically midwest—Silver Meadows is in fact the name of a street in Hido’s hometown of Kent, Ohio. As one’s eyes glance over the pictures, making hazy, dreamlike associations, the bits of text affirm both nostalgic yearning as well as bereavement. Study for Excerpts from Silver Meadows reveals the concept of home to be a highly personal referent: it eludes definition, dissolving the very moment we come to find and appreciate it, only to be replaced by the new and unfamiliar. Musing photographically on his own origins, Hido alludes to the nostalgia and eroticism inherent in the process of outgrowing and leaving one’s childhood home.

Sarah McNear, Deputy Director of Public Programs and External Affairs

Schuyler Duffy, Education and Public Programs Assistant

—

Todd Hido’s Study for Excerpts from Silver Meadows will be available as part of the Aperture 1/1 Benefit & Auction on Monday, October 28. Pre-bidding has started online at Artspace. Find out more about the 1/1 Benefit & Auction and buy tickets here.

October 17, 2013

Protected: Todd Hido: Sources & Influences

This post is password protected. To view it please enter your password below:

Password:

Protected: Todd Hido: Sources & Influences Workshop

This post is password protected. To view it please enter your password below:

Password:

Protected: Bruno Ceschel The Self-Published Photobook

This post is password protected. To view it please enter your password below:

Password:

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers