Aperture's Blog, page 191

September 27, 2013

Alec Soth: The Current State of the PhotoBook (Video)

On September 20th, 2013, Alec Soth spoke on the current state of the photobook in advance of revealing the thirty books shortlisted for the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation First PhotoBook and PhotoBook of the Year Awards.

Stay tuned! All shortlisted titles will be featured in the forthcoming issue of The PhotoBook Review and exhibited at Paris Photo, November 14–17, 2013. The winners in each category will be announced at the fair on November 15, 2013.

September 23, 2013

Recap: Workshop with Rinko Kawauchi

Leading up to the opening of Ametsuchi at Aperture Gallery, Rinko Kawauchi led an insightful workshop over the weekend of September 14 and 15. Students spent a rare eight hours with the Japanese artist, working through presentations and conducting a portfolio review. The course cultivated an intuitive approach to all aspects of photographic workflow, from shooting to bookmaking, and students were left with a refreshed conception of the poetics of photography.

From the students:

“Rinko’s ability to expand on ideas about process and the nature of photography was very helpful.”

“The discussion was enlightening . . .”

—

To find out more about workshops and classes at Aperture, click here.

Ametsuchi, photographs by Rinko Kawauchi, is now available.

Ametsuchi

Ametsuchi$80.00

Recap: Rinko Kawauchi Workshop

Leading up to the opening of Ametsuchi at Aperture Gallery, Rinko Kawauchi led an insightful workshop over the weekend of September 14 and 15. Students spent a rare eight hours with the Japanese artist, working through presentations and conducting a portfolio review. The course cultivated an intuitive approach to all aspects of photographic workflow, from shooting to bookmaking, and students were left with a refreshed conception of the poetics of photography.

From the students:

“Rinko’s ability to expand on ideas about process and the nature of photography was very helpful.”

“The discussion was enlightening . . .”

—

To find out more about workshops and classes at Aperture, click here.

Ametsuchi, photographs by Rinko Kawauchi, is now available.

Ametsuchi

Ametsuchi$80.00

Announcing The Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards Shortlist Selections

Alec Soth, photographer, photobook maker, and publisher, greeted an eager crowd at the New York Art Book Fair this past Friday to announce the thirty outstanding photobooks shortlisted for the 2013 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards.

This year’s shortlist selection was made by Vince Aletti, curator, critic, and author who writes photography reviews for the New Yorker; Julien Frydman, director of Paris Photo; Lesley A. Martin, publisher of the Aperture book program and of The PhotoBook Review; Mutsuko Ota, editorial director of IMA magazine; and Barbara Tannenbaum, curator of photography at the Cleveland Museum of Art.

The jury felt that a diversity of approaches and styles were represented in this year’s entries, and they spent over ten hours to reach their final decisions. “Both content and form are inextricably partnered,” in the shortlisted photobooks, said Tannenbaum. “The content supports the form, the form supports the content. The design and all the aspects of the book are matched by the quality of the pictures. Both have to be very high.” Aletti summarized the list by noting, “The final selection offers a strong, international mix of genres, styles, and approaches to the photobook. It also represents a particular attention to the book as an object, in which selection of images, sequence, scale, typography, and materials are all carefully considered.”

The ten shortlisted titles for PhotoBook of the Year are:

Holy Bible

Photographers: Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin

Publisher: MACK, London / Archive of Modern Conflict, London

New York Arbor

Photographer: Mitch Epstein

Publisher: Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

Iris Garden

Photographer: William Gedney

Text: John Cage

Publisher: Little Brown Mushroom, Minneapolis

The Black Photo Album / Look at Me: 1890–1950

Photographer: Santu Mofokeng

Publisher: Steidl / The Walther Collection, Göttingen / New York

Surrendered Myself to the Chair of Life

Photographer: Jin Ohashi

Text: Nobuyoshi Araki

Publisher: AKAAKA, Tokyo

A01 [COD.19.1.1.43] — A27 [S | COD.23]

Photographer: Rosângela Rennó

Publisher: RR Edições, Rio de Janeiro

Rasen Kaigan

Photographer: Lieko Shiga

Publisher: AKAAKA, Tokyo

Birds of the West Indies

Photographer: Taryn Simon

Publisher: Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern, Germany

The PIGS

Photographer: Carlos Spottorno

Publisher: Phree and Editorial RM, Madrid

War/Photography: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath

Photographers: Various

Authors: Anne Wilkes Tucker and Will Michels, with Natalie Zelt

Publisher: Museum of Fine Arts Houston / Yale University Press, New Haven

The twenty shortlisted titles for First PhotoBook are:

World of Details

Photographer: Viktoria Binschtok

Publisher: Distanz, Berlin

A Period of Juvenile Prosperity

Photographer: Mike Brodie

Publisher: Twin Palms Publishers, Santa Fe

Encouble—Paraître

Photographer: Delphine Burtin

Publisher: Self-published

Speaking of Scars

Photographer: Teresa Eng

Publisher: If / Then Books, London

Pools

Photographer: Craig Fineman

Publisher: Stussy / Dashwood Books, New York

The Canaries

Photographer: Thilde Jensen

Publisher: LENA Publications, Truxton, New York

Nine Nameless Mountains

Photographer: Maanantai Collective

Publisher: Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany

Top Secret: Images from the Stasi Archives

Photographer: Simon Menner

Publisher: Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern, Germany

KARMA

Photographer: Óscar Monzón

Publisher: RVB Books, Paris

Karczeby

Photographer: Adam Pańczuk

Publisher: Self-published

The Fourth Wall

Photographer: Max Pinckers

Publisher: Self-published

History of the Visit

Photographer: Daniel Reuter

Publisher: Self-published

Silvermine

Photographer: Thomas Sauvin

Publisher: Archive of Modern Conflict, London

Beautiful Pig

Photographer: Ben Schonberger

Publisher: Self-published

Grays the Mountain Sends

Photographer: Bryan Schutmaat

Publisher: Silas Finch Foundation, New York

Dawn These Mean Streets

Photographer: Will Steacy

Publisher: b. frank books, Zürich

Return to Sender

Photographer: Sipke Visser

Publisher: Self-published

Ad Infinitum

Photographer: Kris Vervaeke

Publisher: Self-published

Dalston Anatomy

Photographer: Lorenzo Vitturi

Publisher: Jibijana Books in association with SPBH Editions, London and Milan

La Montagne Dorée

Photographer: Myriam Ziehli

Publisher: Self-published

—

The selected photobooks will be exhibited at Paris Photo at the Grand Palais and at Aperture Gallery in New York and will tour to other venues, to be determined. They will also be profiled in issue 005 of The PhotoBook Review, Aperture’s biannual publication dedicated to the consideration of the photobook.

A final jury in Paris will select the winners for both prizes, which will be revealed at Paris Photo on November 15, 2013. The winner of First PhotoBook will be awarded $10,000. Immediately preceding the announcement, the fair will host book signings of the shortlisted titles.

PhotoBook Awards Pre-Jury:

Vince Aletti reviews photography exhibitions for the New Yorker and writes a regular column about photo books for Photograph. He was a contributing author to Andrew Roth’s The Book of 101 Books: Seminal Photographic Books of the Twentieth Century and is the winner of the 2005 Infinity Award in writing from the International Center of Photography. In 2009, Aletti co-curated Weird Beauty: Fashion Photography Now with Carol Squiers at the ICP and was the curator of This Is Not a Fashion Photograph, among other exhibitions. His most recent book, Rodeo, featuring the work of Bruce of Los Angeles, was published this fall by ACNE Studios.

Barbara Tannenbaum is curator of photography at the Cleveland Museum of Art, where she recently organized DIY: Photographers and Books, an exhibition on print-on-demand photobooks. Previously, she spent twenty-six years as chief curator of the Akron Art Museum, where she organized over eighty exhibitions including the first large-scale exhibition chronicling women’s historic achievements in photography; the first solo museum show of Adam Fuss; and Ralph Eugene Meatyard: An American Visionary. Tannenbaum has edited and authored numerous publications, including Detroit Disassembled by Andrew Moore (2010). She serves on the board of the Fred and Laura Ruth Bidwell Foundation.

Mutsuko Ota is editorial director of IMA magazine. After graduating from Waseda University, she started her career as an editor at Marie Claire. She then worked at several men’s magazines such as Esquire and GQ as a features editor on travel, gastronomy, culture, art, and photography, among other subjects. In addition to collaborating with several magazines as a freelance editor, she has also been involved in the development and production of various art projects, book and catalog editing, and film promotion throughout her career. She became the editorial director of IMA in January 2012.

Since March 2011, Julien Frydman has been director of Paris Photo, the international fair dedicated to photography. In April 2013, he launched Paris Photo Los Angeles at Paramount Pictures Studios. From 2006–2011, Frydman was general director of Magnum Photos Paris, where he was responsible for a team that developed the careers of eighty agency photographers throughout Europe and the United Arab Emirates. Prior to Magnum, he worked in the French Ministry for Culture and National Education and as a consulting director at the TBWA Advertising Group.

Lesley A. Martin is publisher of Aperture Foundation’s book program and of The PhotoBook Review. Her writing on photography has been published in Aperture, American Photo, Stay Flat, and FOAM, among other publications, and she has edited over eighty books of photography, including Reflex: A Vik Muniz Primer; Richard Misrach: On the Beach; Penelope Umbrico: Photographs; and Rinko Kawauchi: Ametsuchi.

September 18, 2013

Call for Participation: Collaboration – Revisiting the History of Photography

[image error]

Aperture Foundation, New York

Saturday, December 7, 2013

Curated by Ariella Azoulay, Wendy Ewald, and Susan Meiselas, in association with graduate students at Modern Culture and Media Department, Brown University

We invite the public to participate in our effort to create a complex and rich timeline of collaboration in photography. On December 7, 2013, we will present at the Aperture Gallery a first draft of the timeline based on our research conducted with graduate students from Brown University who will have participated in a seminar on “Collaboration and the Event of Photography,” as well as from the input collected as responses to this call (see the guidelines for submission below). The public is invited to send in advance references to existing collaborative projects from different times and places for eventual inclusion in the timeline. At this point, we are especially interested in projects from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries. The projects constituting the timeline will be displayed through archival documentation and small reference prints in a laboratory mode, and will be open for discussions and changes on the opening day. The curators reserve the right not to include all the submitted projects. The timeline shaped during this process will be used in the next phase of the project.

In this project we seek to reconstruct the material, practical, and ideological conditions of collaboration through photography and of photography through collaboration. We will seek ways to foreground—and create—the tension between the collaborative process and the photographic product (which does not necessarily bear visible traces of this process) by reconstructing the participation of others, usually the more “silent” participants. We will do this through the presentation of a repertoire of types of collaborations, those which take place at the moment when a photograph is taken, or others that are understood as collaboration only later, when a photograph is reproduced and disseminated, juxtaposed to another, read by others, investigated, explored, preserved, and accumulated in an archive to create a new database.

Our first assumption is that a certain degree of collaboration is implicit in photography. This may become explicit when the collaboration between photographers and photographed persons is continued by their transformation into spectators, spectators among others. Against the prevalent practice and the entrenched notion of the photographer as a figure who arrives at an unfamiliar place, takes pictures and vanishes with the photographs that s/he will show elsewhere, in collaborative projects, the duration, attention, and exchange are negotiated differently.

The second assumption is that revisiting the history of photography through the notion of collaboration should be done collaboratively with others who are familiar with different times, places, and contexts.

Guidelines:

Please send a short description of the collaborative project that you want to suggest for the timeline including photographer’s name, title of the project, production year, location, and 2–3 photos.

Submissions can be sent to collaboration.timeline@gmail.com until October 1, 2013.

The curators reserve the right not to include all the submitted projects. Research for the selected projects should be completed by mid-November. Each project will be displayed in the timeline in a condensed way through up to five hundred words and 3–5 photos. The text should foreground the various aspects of the collaboration, indicating (if known): name of the photographed people and other participants, type of camera used, process of viewing and displaying the photographs, a description of the process of collaboration, and 3–5 photos, and any additional material should be sent to collaboration.timeline@gmail.com.

Selected projects will have the opportunity to participate in the working session to create the timeline on December 6 for public viewing on December 7.

Topics that we are currently working with include but are not limited to:

● The Archive belongs to the Community (e.g., Palestine Remembered, Kurdistan - Susan Meiselas, We are all children of Algeria, Nicholas Mirzoeff)

● The Exhibition as an Image of Community (e.g. Negro Exhibit- W.E.B. Du Bois’, American Alphabets – Wendy Ewald)

● Resistance / Advocacy – Conversations with the Dead – Danny Lyon

● Intimacy, Violation, Exposure (e.g. Alfred Steiglitz and Georgia O’Keefe)

● Inventing the archive – Akram Zaatari, Walid Raad

● The Invention of the Photographed Person (e.g. Pierre-Louis Pierson and Countess di Castiglione, Suffragists)

● Forced Collaboration (e.g. Femmes Algeriennes – Marc Garanger, Secret Police, IDF search practices)

● The Child as Model/Author/ Full Participant (Wendy Ewald, B’tselem)

● The Icon Claims Subjectivity (eg Sharbat Gula, ‘the Afghan Girl,’ eg Kim Phuc, ‘the napalm girl’)

● The Resistance of the Photographed Person (eg Dorothea Lange and Florence Owen Thompson, Neji Bensalah)

● Documenting the Body at Risk (e.g. Eugene Richards and Dorothea Lynch)

● Woman As Muse and other fantasies of collaboration (e.g. Jessie Mann and Len Prince)

● The Photographed Person becomes His/Her Own Spectator (e.g. People of San Francisco – Jim Goldberg)

● Prison, Hospital, and Camera (Nhem Ein, Chanarin & Broomberg, The Center for Investigative Reporting)

September 13, 2013

We’re Now Closed for Entries, but Stay Tuned!

The 2013 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards are now closed for entries. Thank you to all who submitted and participated!

The thirty titles shortlisted for the awards will be announced by Alec Soth next Friday, September 20, 2013, at the New York Art Book Fair. All shortlisted titles will be featured in the forthcoming issue of The PhotoBook Review and exhibited at Paris Photo, November 14–17, 2013. The winners of each category will be announced at the fair on November 15, 2013.

Be sure to stay tuned to PhotoBook Awards news, streaming images, and video via Twitter (@PhotoBookReview) and Instagram (@aperturenyc) in the months to come. Also, subscribe to Aperture magazine to receive your copy of The PhotoBook Review, featuring the thirty shortlisted entries.

Visit Aperture at EXPO CHICAGO

Andrea Galvani, Death of an Image #4C, 2005/2012. Available at the Aperture booth at EXPO Chicago and online.

Photograph by Richard Misrach. Courtesy of Robert Mann Gallery, New York.

Photograph by Alec Soth. Courtesy Weinstein Gallery, Minneapolis.

Photograph by Joel Sternfeld. Courtesy Luhring Augustine, New York.

Photograph by Angela Strassheim. Courtesy Andrea Meislin Gallery, New York.

Photograph by Shomei Tomatsu. Courtesy Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo.

Visit Aperture at booth 101 at EXPO CHICAGO, which will feature selections from the limited-edition print program by Jason Evans, Andrea Galvani, Richard Mosse, and James Welling, as well as a collection of new book releases. The fair is open from Thursday, September 19, to Sunday, September 22.

On September 22, join Aperture for a talk with artist LaToya Ruby Frazier and Karen Irvine, curator and associate director of the Museum of Contemporary Photography (MOCP) at Columbia College Chicago.

Many exhibitors at EXPO CHICAGO will feature photography. Among the artists whose work will be on view are Shomei Tomatsu (at Taka Ishii Gallery), Joel Sternfeld (at Luhring Augustine), Angela Strassheim (at Andrea Meislin Gallery), Christopher Williams (at David Zwirner), and Alec Soth (at Weinstein Gallery).

Photography exhibitions and events will take place throughout the city during the fair weekend, including a Kenneth Josephson exhibition at Stephen Daiter Gallery For more information, visit EXPO CHICAGO‘s website.

September 11, 2013

The Form of the PhotoBook (Video)

More than six hundred photobook submissions have filled Aperture Foundation’s shelves over the past twenty-one weeks, and we expect yet more to arrive as we approach the final days of the Paris Photo—Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards call for entries.

On this occasion, Lesley A. Martin, publisher of Aperture’s books, sat down to discuss selections from the submission pool, the details that compel a juror to spend time with a book, and thoughts on the form of the photobook in relation to the images within.

Ready to submit? Visit the prize site for full entry details through Friday, September 13, 2013.

Stay tuned to PhotoBook Awards news and streaming images via Twitter (@PhotoBookReview) and Instagram (@aperturenyc) in the months to come.

Site Specific: Introduction by Christopher Phillips

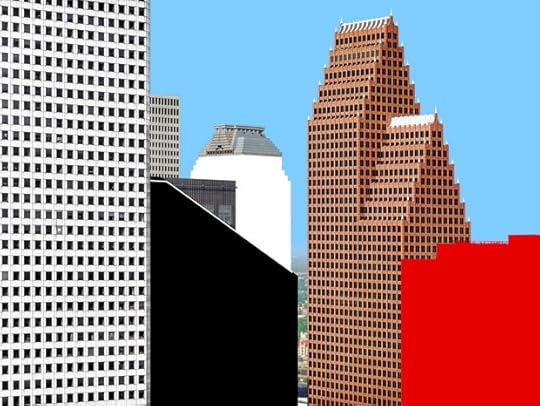

site specific_ROMA 04 from Site Specific. All photographs © Olivo Barbieri and courtesy of Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

Olivo Barbieri is one of the world’s most restless photographers. Between 2003 and 2012, while working on his Site Specific series, he photographed more than forty of the world’s cities from a helicopter hovering in midair. The geographic scope of the project took him to every corner of the planet; his artistic ambition prompted him to employ an unprecedented range of photographic techniques in making his images. Temperamentally, Barbieri has never really been a documentary photographer, and he has never been convinced that straight-forward images can fully convey the hallucinatory qualities that he finds in modern urban spaces. During the first five years of the Site Specific series, he used a special tilt-and-shift lens that enabled him to drastically alter perspective and scale within his photographs. Later, he used digital post-production techniques to modify the color balance, tonal relations, and even the pixel structure of his images. If Site Specific provides an almost anthropological commentary on the human drive to create and inhabit densely layered urban environments, it is simultaneously a stylistic tour de force that takes photography’s visual language far beyond its customary boundaries.

An engagement with the built environment and a need to expand photography’s expressive means have characterized Barbieri’s work since he began seriously photographing in the early 1970s. Living and working in the vicinity of Modena, in Italy’s Emilia-Romagna province, he was in his early twenties when he met Luigi Ghirri (1943–1992), one of the most significant Italian photographers of his era. Ghirri made it his mission to introduce younger Italian photographers to the heritage of classic photographers such as Eugène Atget and August Sander, but he also made them aware of vital contemporary directions, such as the new explorations of color photography being carried out in the 1970s by figures such as William Eggleston and Stephen Shore. Barbieri’s early familiarity with photography’s past and present, and his fascination with modern painting, prepared him to recognize that his own sensibility was not well matched to the documentary style of even so sophisticated a practitioner as Walker Evans. He was drawn instead to the dreamlike visual spaces created by painters like Giorgio di Chirico and photographers like Man Ray. “I started out from classical photography,” Barbieri has recalled, “from an attempt to describe the world around me as objectively and aseptically as possible. It turned out the results of this approach showed a world which seemed absolutely phantasmagoric and unreal.”

···

From the outset, Barbieri felt that the aim of Site Specific was not to produce an objective document of the world’s cities but to somehow push photography’s language into new territory. He was captivated by a vision of the twenty-first-century city as a kind of site-specific installation—temporary, malleable, and constantly in flux—and he sought a photographic corollary for the radical mutations of urban form that he saw taking place. By using a medium-format camera outfitted with a tilt-and-shift lens, he found that he was able to register enormous quantities of precise visual information and at the same time throw whole sections of the image disorientingly out of focus. The resulting photographs made modern cities appear to be reduced-scale architectural models—a vision, as Barbieri put it, of “the city as an avatar of itself.” He was also keenly aware of the deadly events of September 11, 2001, which had revealed the shocking vulnerability of such architectural monuments as New York’s twin towers. “After 9/11,” he observed, “the world had become a little bit blurred because things that seemed impossible happened.”

···

In Rome and Las Vegas Barbieri used his tilt-and-shift lens technique to bring an air of unreality to his images of those cities, but for Site Specific SHANGHAI 05 he decided that a different approach was called for. “Shanghai,” he said, “is so much like a model that it was not necessary to use the lens.” Surprisingly, he paid little attention to the most celebrated buildings, making no photographs of the lavishly renovated neoclassical buildings along the Bund, nor of the thicket of glass-and-steel towers crowding the new Pudong business district. Instead Barbieri presented Shanghai as an immense, amorphous terrain packed with clusters of indistinguishable twenty- and thirty-story residential high-rise developments. These mega-complexes, built to house Shanghai’s eighteen million inhabitants, spill over the city’s peripheries and stretch as far as the helicopter-borne eye can see. From this vantage, Shanghai suggests what Barbieri called a barely controlled “biological experiment”—an organism whose pure expansive energy was pushing relentlessly up to the heavens and out to the horizon.

Olivo Barbieri, site specific_SHANGHAI 04.

Such a wildly sprawling urban form, which represents one of the latest turns in the evolution of the modern city, can be grasped fully only from the air. It has been described by the architectural historian Kennneth Frampton as marking the transition from the age of the metropolis to that of the “megaform.” This is Frampton’s term for the city type produced by the contemporary urban explosion set off by the unleashed social forces and vast accumulations of capital in Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East, sending waves of new built structures sweeping over entire regional landscapes. Barbieri’s decision to extend the Site Specific series beyond his original plan was made in part to allow him to photograph such emerging centers as São Paulo, Istanbul, Bangkok, and Mexico City. The transformative dynamic that he found in the developing world also prompted him to revisit and photograph a number of cities in his native Italy, such as Milan, Florence, Genoa, Venice, and Naples. In the recent changes he discovered there, he could now perceive echoes of larger processes occurring around the world.

Because Barbieri never regarded the Site Specific series as documentary in intent but as part of his continuing effort to enlarge photography’s visual language, he continued to seek out new means of picturing the cities that he scrutinized from his aerial perch. He was quick to notice that new, Web-based imaging technologies were providing fresh ways to portray the world we inhabit. Google Earth, for example, began in 2005 to put on-line high-resolution satellite views of much of the planet’s surface. Google Street View, launched in 2007, offered interactive panoramic photos of virtually every block in most world cities.

···

Olivo Barbieri, site specific_HOUSTON 12.

The boundless visual inventiveness of the Site Specific project ultimately masks a cautionary message, as Barbieri himself acknowledges. “Today,” he said, “we humans are surprised at how good we are at doing impressive construction. But we’re also a little afraid of what we’ve done. We’ve created a new kind of urban sublime that combines the elements of awe and fear, just as the nineteenth-century sublime regarded the great mountains of the Alps.” In the end, his successive reimaginings of the look of the twenty-first-century city teach us to regard it in the distanced manner as an architect or city planner: as a set of essentially impermanent, transformable spaces awaiting the imperious intervention of the urban designer. It is this calculated ambivalence, which lies at the heart of the Site Specific project, that makes it something more than a decade-long exercise in photographic virtuosity. “I’ve never been interested in photography,” Barbieri says, “but in images. I believe my work starts when photography ends.”

—

This piece is excerpted from a longer essay included in Site Specific: Photographs by Olivio Barbieri (Aperture, 2013).

Writings by, and an interview with, Christopher Phillips are also included in Aperture magazine issues #184 and #191.

Site Specific

Site Specific

$75.00

Aperture 184$14.80

Aperture 184$14.80 Aperture 191$14.80

Aperture 191$14.80

September 9, 2013

Shelby Lee Adams Workshop Recap

Photo by Elli Trier

Photo by Anne Connor

Photo by Linda Cicero

Photo by Shelby Lee Adams

We are pleased to report the success of Shelby Lee Adams’s environmental portraiture workshop, held on July 13 and 14. The course exposed students to the varying psychological and technical faculties of portraiture through the study of images and an on-location shoot in New York’s Tompkins Square Park. The resulting photographs stand as testament to the tenacious and astute observations made by this group of students over the course of the workshop.

From the students:

“This workshop exceeded my expectations. I had questions answered that I didn’t even know I had. . . . I will go home with many things to practice and dissect.”

“I never shot with studio lighting because I thought it would be too difficult. The workshop helped to ease that fear, and now I feel confident.”

From Adams:

“Tompkins Square Park was great and we had good weather. People were willing to pose for photos and a diverse range of people were present. The quality of the students was good, with at least three professional photographers, an economics professor, a published author of architecture books, a nationally recognized documentary filmmaker, an Appalachian photographer from West Virginia, and two people who flew in from Madison, Wisconsin. All eleven participated to the end.”

To find out more about workshops & classes at Aperture, click here.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers