Aperture's Blog, page 193

August 8, 2013

PhotoBook Awards 2013: New Arrivals Vol. 2

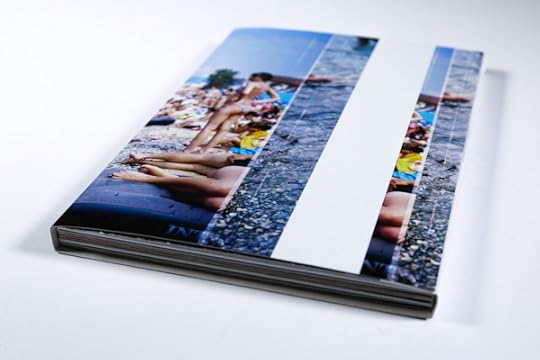

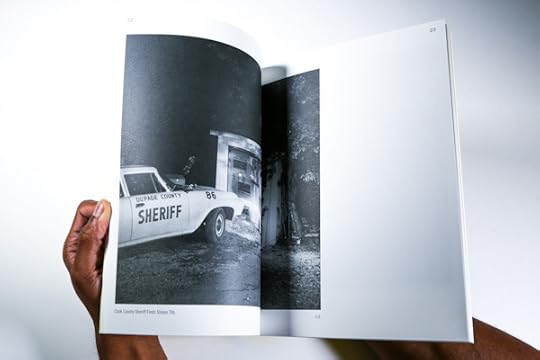

From College. Photographs by Michael Jang.

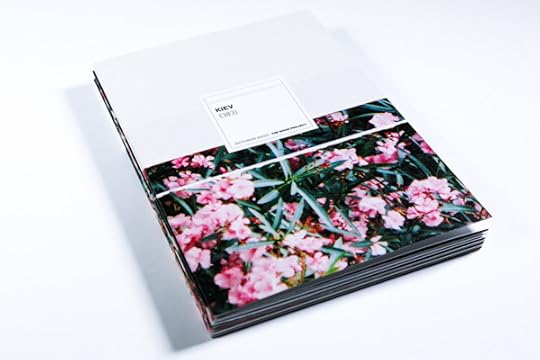

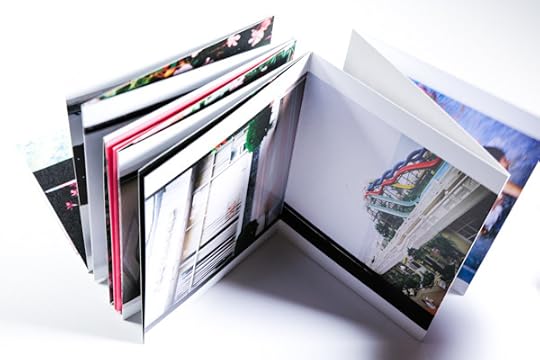

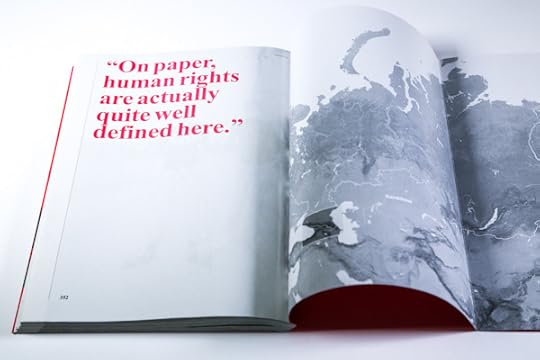

From KIEV. Book by Rob Hornstra/The Sochi Project.

From KIEV. Book by Rob Hornstra/The Sochi Project.

From KIEV. Book by Rob Hornstra/The Sochi Project.

From KIEV. Book by Rob Hornstra/The Sochi Project.

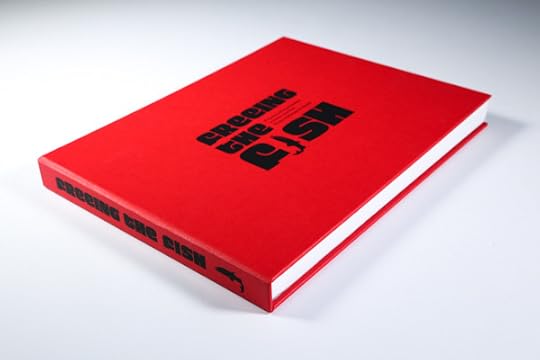

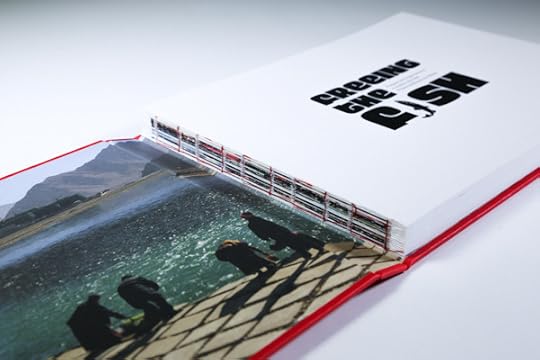

From Freeing the Fish. Photographs by Marieke ten Wolde.

From Freeing the Fish. Photographs by Marieke ten Wolde.

From Freeing the Fish. Photographs by Marieke ten Wolde.

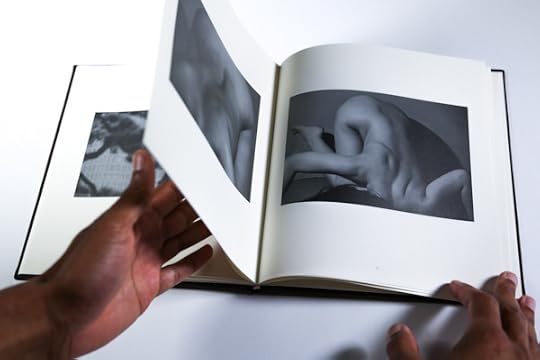

From I Love You, Stupid!. Photographs by Dash Snow.

From I Love You, Stupid!. Photographs by Dash Snow.

From Black Sea of Concrete. Photographs by Rafal Milach.

From Black Sea of Concrete. Photographs by Rafal Milach.

From Black Sea of Concrete. Photographs by Rafal Milach.

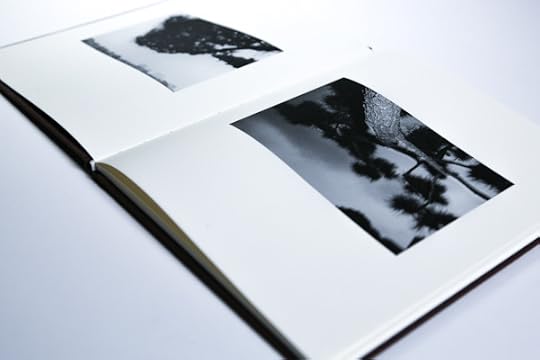

From Monogatari of Pines. Photographs by Suda Issei.

From Monogatari of Pines. Photographs by Suda Issei.

From Monogatari of Pines. Photographs by Suda Issei.

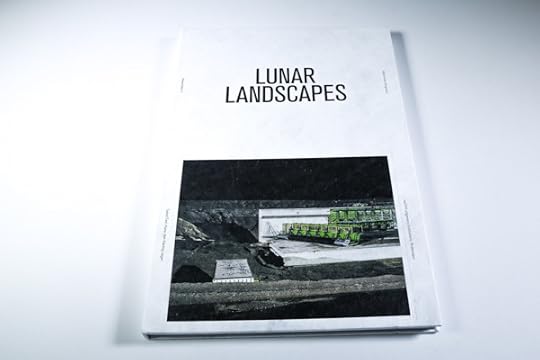

From Lunar Landscapes - Maasvlakte 2. Photographs by Marie-José Jongerius.

From Lunar Landscapes - Maasvlakte 2. Photographs by Marie-José Jongerius.

From Lunar Landscapes - Maasvlakte 2. Photographs by Marie-José Jongerius.

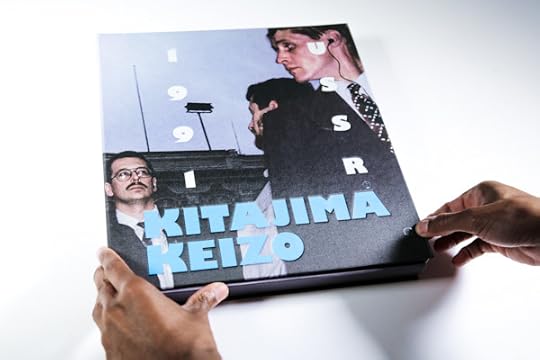

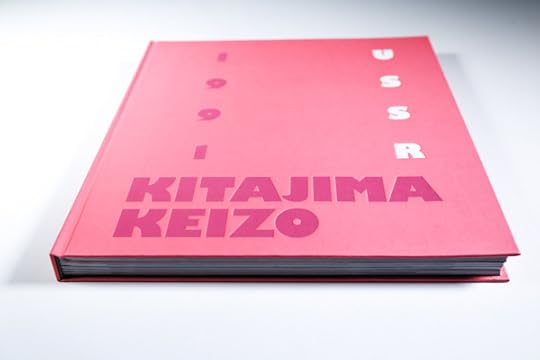

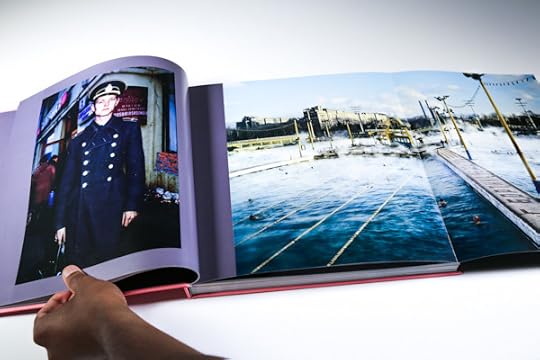

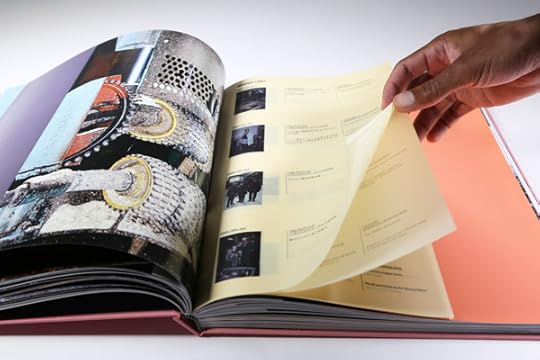

From USSR 1991. Photographs by Keizō Kitajima.

From USSR 1991. Photographs by Keizō Kitajima.

From USSR 1991. Photographs by Keizō Kitajima.

From USSR 1991. Photographs by Keizō Kitajima.

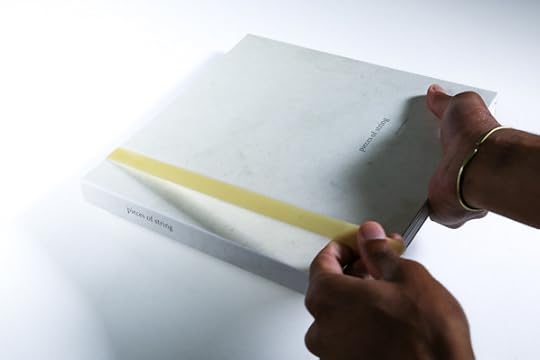

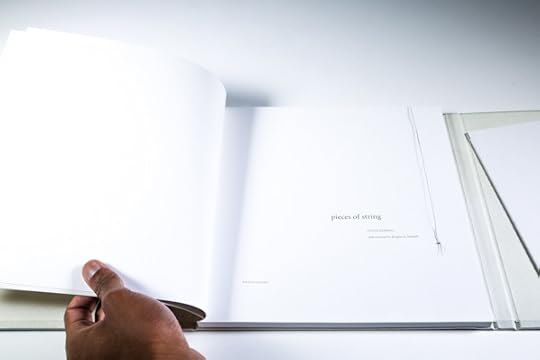

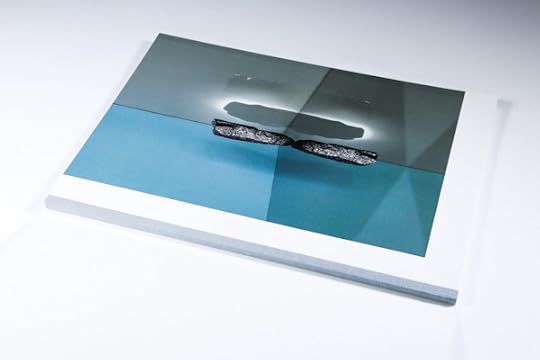

From Pieces of String. Photographs by Justin Kimball.

From Pieces of String. Photographs by Justin Kimball.

From Pieces of String. Photographs by Justin Kimball.

From Formationen – Formations. Photographs by Samuel Henne.

From Formationen – Formations. Photographs by Samuel Henne.

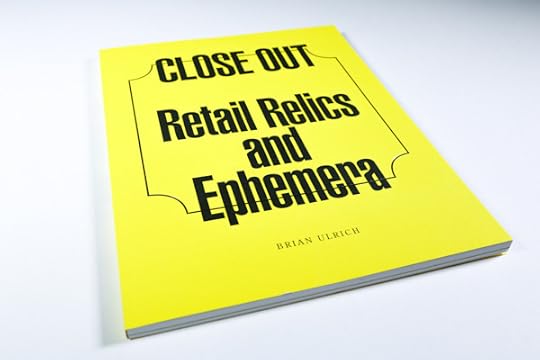

From Close Out: Retail Relics and Ephemera. Photographs by Brian Ulrich.

From Close Out: Retail Relics and Ephemera. Photographs by Brian Ulrich.

From The Secret History of Khava Gaisanova. Book by Rob Hornstra/The Sochi Project.

From The Secret History of Khava Gaisanova. Book by Rob Hornstra/The Sochi Project.

With just six weeks remaining in the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards 2013 call for entries, we offer the second in a series of looks at the latest photobook arrivals in each award category. In this installment we present a selection of entries to the PhotoBook of the Year category, which includes recently published books by photographers Rob Hornstra, Keizō Kitajima, Dash Snow, and Brian Ulrich.

In case you missed it, take a look back at Latest Arrivals Vol. 1, which highlighted selections from the First PhotoBook category. And stay tuned for more images from the 2013 entry pool, which will be featured on the PhotoBook Awards site and on Instagram (@aperturenyc) in the months to come.

Ready to submit? Visit the prize site for FAQ and full entry details.

August 6, 2013

Economy Class

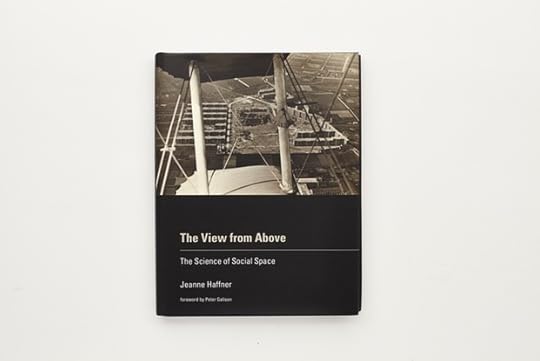

In fall 2005, as riots surged across the outskirts of Paris, English got a new Gallicism—one that, for once, concerned neither food nor fashion. That word, banlieue, wedged itself between its translation, suburb, which in America signifies a middle-class Elysium, and the peripheral housing blocks where the deaths of two teenage boys had fomented large-scale wide-civil unrest. Yet to go by the insights of Jeanne Haffner’s recent book, the real distinction may lie not in what we call these spaces, but in how we see them. If America, land of the automobile, sees itself through a windshield, France views its cities from the airplane cockpit. From that vantage, the banlieue is not a haven; it is a margin, a banned place.

The View from Above: The Science of Social Space charts fifty years of aerial photography in France, from its early use in military intelligence and ethnographic research to its role in constructing and critiquing the contemporary banlieue. Readers looking for a history of aerial photography, however, won’t find it here. Haffner’s book is a genealogical study not so much of a photographic genre as the discipline it by turns formed and undergirded: the study of social space. Although it parallels new studies in cultural geography and technologies of vision by the likes of Denis Cosgrove and Jonathan Crary, View from Above shifts our attention from the formation of subjects to the birth of discourses.

For Haffner, the “production of space,” in Henri Lefebvre’s phrase, became a viable field of study through the aerial photograph. The view from above gave a motley crew of French sociologists, politicians, theorists, and ethnographers tools to read space as a network of social, economic, and environmental relations. Haffner moves nimbly from outlining the professional utility of aerial photography, which lent a young, interdisciplinary field an air of objectivity and scientism, to describing its political potential as an instrument to analyze economic disparity. In the course of these insights, she unearths a cast of lesser-known heroes of the ether—“human geographer” Pierre Gourou, socialist sociologist Raymond Ledrut, and the proto-urban sociologist Paul-Henry Chombart, who emerges as the book’s central protagonist.

Chombart’s privileged position reflects less the influence of his work than its exemplary nature. Chombart, argues Haffner, hit a disciplinary sweet spot, embracing the scientific promises of the vue d’ensemble while using its findings to advance a humanist agenda. Aerial photography emerges as a fallen Esperanto for urban planners and sociologists, a Tower of Babel of interdisciplinary Marxism struck down by the very field it once structured. In the final chapter, Haffner traces the rejection of aerial photography as the French New Left began to suspect that such distanced views obscured rather than revealed the realities of everyday life. To these intellectuals, Lefebvre central among them, aerial photography signaled an oppressive, technocratic approach to urban planning at loggerheads with a socialist critique of capitalism. While clearly sympathetic to this critique, Haffner doesn’t conceal her dismay at its rejection of the “view from above.” Holistic viewpoints, she urges, are more than ever necessary. The view from above exposes the global consequences of capitalism, social and environmental injustices that can be read on the surface of the world. But few can claim ignorance of those injustices today, with or without the vue d’ensemble. Any larger claim to the significance of aerial photography would seem to depend on the particular moral force of the photographs themselves—a force Haffner does not directly address.

Be that as it may, the aerial view’s charms turn here on the aesthetic of its golden years. The View from Above is richly illustrated with photographs and diagrams, from Marcel Griaule’s low-flying shots of Dogon territory to Le Corbusier’s doodles of Latin American urban organicism—with nary a Situationist collage or satellite image in sight. As Haffner notes, one development behind the left’s rejection of the aerial photograph was a dramatic change in scale, marking not just a different degree of visual information, but a new vantage. The cockpit became the satellite, and with that change came new authorities: the pilot-cum-photographer gave way to state-controlled surveillance. By choosing to narrate the development of a discourse rather than a technology, Haffner neglects to discuss who owned and controlled aerial photography, and how that history might inflect her research.

I suspect such a focus might have displaced the spirit of contradiction in this book—a sign, perhaps, of any good study of modernism. The conflicts here are abundant and intriguing, swinging with a kind of simian agility across political and ontological positions. They occur between the “mechanical objectivity” of the aerial view and its interpretive burden; between its usefulness for critiquing capitalism and its deployment by Vichy-era politicians; and between its capacity to glean the underlying social structure of a culture, and the observation, made by Claude Levi-Strauss, that spatial configurations reflect not the reality of a culture, but the ideals of its elite. This discernment into the limits of aerial photography, however, is muffled by those thinkers—Haffner, perhaps, included—who would see in the technology a means of speaking across disciplines to improve the lot of the many. At times, Haffner herself seems to slip from recounting the early faith in aerial photography’s legibility to adopting that faith herself, and thereby excluding the contemporary critiques. For Lefebvre, in any case, it was the supposed absolute legibility of these methods that allowed them to colonize everyday life. Lefebvre’s own insight, cited by Haffner, is instructive here: “Inasmuch as the act of seeing and what is seen is confused, both become impotent.”

Joanna Fiduccia is a critic, curator, and PhD student in the Department of Art History at the University of California, Los Angeles. She lives in New York.

Jeanne Haffner’s The View from Above is available now from MIT Press.

August 3, 2013

This another workshop

Tuition: $500 ($450 for currently enrolled photography students and Aperture Patrons)

Do you know where you’re going next with your photography—or where it’s taking you? This intensive weekend workshop will help photographers begin to understand their own distinct way of seeing the world. It will also help photographers figure out their next step photographically, from deepening a unique vision to discovering and completing a long-term project to translating a body of work into books and exhibitions. This is a workshop for serious amateurs and professionals alike, taught by Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb, a creative team who often edit projects and books together, including their joint book and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, exhibition Violet Isle: A Duet of Photographs from Cuba; Alex’s recent Aperture book, The Suffering of Light; and Rebecca’s new book My Dakota. Included in the workshop will be an editing exercise as well as an optional photography assignment or long-term-project review. Participants should be prepared to ask questions, as these concerns will help shape the ultimate direction of the workshop.

Alex Webb is best known for his vibrant and complex color photography, often made in Latin America and the Caribbean. He has published nine books, including Istanbul: City of a Hundred Names, Aperture and Violet Isle: A Duet of Photographs from Cuba (with Rebecca Norris Webb). His latest book, The Suffering of Light, a collection of thirty years of his color work, was published by Aperture (2011). Alex has exhibited at museums worldwide, including the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; High Museum of Art, Atlanta; and Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego. Alex became a full member of Magnum Photos in 1979. His work has appeared in National Geographic, New York Times Magazine, Geo, and other magazines. He has received numerous awards and grants.

Originally a poet, Rebecca Norris Webb has published three photography books that explore the complicated relationship between people and the natural world: The Glass Between Us, Violet Isle: A Duet of Photographs from Cuba (with Alex Webb), and My Dakota, which interweaves her text and photographs from her home state of South Dakota. In 2012, My Dakota was selected as a Time, PDN, and Photo-Eye best photography book of the year. Her work has been exhibited internationally, including at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the George Eastman House, Rochester, New York In 2012, My Dakota was exhibited at the Dahl Arts Center in Rapid City, South Dakota, and the Robert Klein Gallery, Boston, and will be exhibited in summer 2013 at the Ricco/Maresca Gallery, New York, and the North Dakota Museum of Art, Grand Forks. Her work has appeared in Time, Orion, and Le Monde Magazine.

WORKSHOP SCHEDULE

Friday, June 21

7:00–8:30 p.m.—Alex and Rebecca’s joint slide talk, book signing, and Q&A, open to the public.

Saturday & Sunday, June 22–23

10:00 a.m.–6:00 p.m.—This weekend workshop will begin with reviews of each participant’s work on Saturday morning, a process that will spark a larger discussion about various photographic issues, including the process of photographing spontaneously and intuitively; how to edit photographs; how to work in cultures different than one’s own; and how long-term projects can evolve into books and exhibitions. The first day will end with a group editing exercise and an optional photography or editing assignment. Sunday will be dedicated to reviewing each participant’s assignments, as well as a series of presentations about bookmaking and exhibitions that will end with an informal Q&A session with the Webbs. Lunch will be served.

Refund/Cancellation Policy for Aperture Workshops

All fees are nonrefundable if you withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date if the workshop is under-enrolled, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

August 2, 2013

Picking Up the Pieces

Thomas Hirschhorn, Touching Reality, 2012. Courtesy the artist; Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris; and Barbara Gladstone Gallery, New York.

Mishka Henner, Unknown Site, Noordwijk aan Zee, South Holland, 2011. Courtesy the artist.

Hito Steyerl, still from Abstract, 2012. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Ray Anastas and Leon Kahane.

Shimpei Takeda, Trace #7, Nihonmatsu Castle, 2012. Courtesy the artist.

Lucas Foglia, Acorn with Possum Stew, Wildroots Homestead, North Carolina, 2006. Courtesy the artist.

Oliver Laric, still from Versions, 2010. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin; and Seventeen, London.

Implicit in the purposefully vague title of the third International Center of Photography triennial, A Different Kind of Order, is a sense that some substantial schism has recently taken place, within photography as much as within broader society, and has upset our normal ways of thinking and doing. It begs the question: how? Though the exhibition’s curators—Kristen Lubben, Christopher Phillips, Carol Squiers, and Joanna Lehan—have provided myriad provisional answers by way of an eclectic collection of work produced by a largely interesting assortment of artists, it is telling that the show’s working title was less sanguine: Chaos.

Indeed, chaos rears its head frequently in the show, most notably in the form of strong works that allude to various political and environmental crises. Chief among these is Thomas Hirschhorn’s deeply disquieting, deceptively simple Touching Reality (2012), a looping five-minute video of a woman’s hand scrolling through iPad images that depict the battered, broken bodies of people killed in recent conflicts. These images, which are readily available on the Internet but rarely, if ever, surface in the mainstream media, are unspeakably horrific: brain matter oozing out of shattered skulls, slick viscera flopped on dusty pavement, severed heads decorated with macabre tassels of tendon, vein, and bone. They form a relentless, stomach-churning parade of death and suffering. Incongruously, however, the hand guiding us through this grizzly landscape is slender, pretty, and well manicured. It caresses the glossy surface of the space-age tablet gingerly, lingering on certain images or zooming in on details both terrible and banal, as if conducting a virtual forensic investigation. Just as often, it blithely flips past gruesome scenes as if it belonged to a distracted teenager idly cruising her Instragram feed. In this, the piece vaults past mere agitprop to become a metaphor for our own state of digitized distraction and desensitization, providing a holistic dissection of a particularly fraught aspect of contemporary image politics through an elegant economy of means.

Videos by Hito Steyerl and Rabih Mroué also provide nuanced looks at the intersection of politics and image culture. Steyerl, for her part, presents a pair of videos concerning the death of her friend Andrea Wolf at the hands of the Turkish government, a result of her participation in the PKK, a Kurdish separatist movement. The best, and most well-known, of these videos, November (2004), tracks Wolf’s transmogrification from the ersatz revolutionary that she often played in her and Steyerl’s homemade B-movies into the real thing, and ends with her image’s immortalization by way of protest placards commemorating her martyrdom. The accompanying two-channel video, Abstract (2012), is something of a contemporary take on Brecht’s famous observation about a photograph of a factory revealing nothing of social and political relations that undergird it. It pairs scenes of Steyerl photographing the Berlin outpost of American defense contractor Lockheed Martin with those showing her and a friend being guided around a placid patch of mountainous terrain where Wolf and a group of her compatriots were bombarded with Lockheed-manufactured Hellfire missiles. Mroué’s contribution, the video version of a performance lecture entitled The Pixilated Revolution (2013), operates in a similar vein: the artist delivers a complexly poetic “non-academic lecture” on citizen journalism during the current Syrian civil war, inspired by a friend’s observation that in the absence of official media coverage “the Syrian people are filming their own death.”

Trevor Paglen, The Fence (Lake Kickapoo, Texas), 2010. Collection New School Art Collection. Courtesy the artist; Altman Siegel, San Francisco; Metro Pictures, New York; and Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne.

Other notable works in the show point to contemporary chaos and upheaval but mostly shy away from self-reflexivity. These include a collection of striking photograms by Shimpei Takeda that resemble rudimentary images of the cosmos, exposed by way of contact with radioactive soil from areas surrounding the Fukushima nuclear disaster; Gideon Mendel’s affecting though slightly stagey images of victims of massive flooding precipitated by manmade climate change; and Lucas Foglia’s more lyrically inflected photojournalistic studies of American secular and religious intentional communities whose pastoralism, in this context, is tinged with an air of the post-apocalyptic.

Of all the politically inflected pieces in the show, however, only two bodies of work—by Mishka Henner and Trevor Paglen—suggest what one aspect of the exhibition’s titular “different order” might be. Both examine the shadowy doings of government. Henner appropriates sections of Google Maps that have been censored in an inadvertently artful, kaleidoscopic manner to conceal sensitive sites. Paglen presents a pair of sublime, horizonless skyscapes intruded upon by the nearly imperceptible presence of unmanned drones. A companion video, Drone Vision (2010), consists of an eerie snippet of drone’s-eye-view footage intercepted from a communications satellite, and an image, created in collaboration with an amateur radio astronomer, of the vast United States government radar system known as “The Fence,” designed to detect foreign spacecraft and intercontinental ballistic missiles. While chaos runs roughshod over the tender earth, these works intimate a new order being instilled from above: a global, high-tech network of surveillance and control whose construction within the United States was aptly characterized by NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden as the foundation of “turnkey tyranny”—an architecture that, once in place, could usher in an Orwellian future with a mere flick of a switch.

This, however, is only half the story. The triennial’s secondary, more parochial concern lies not with the fate of the world, but with the medium of photography itself. Of course, taken in the context of an institution whose very existence is predicated on medium specificity, this concern’s parochialism is relative.

Photography, in its traditional incarnations, is at a crossroads. Perhaps paradoxically, at the moment of the medium’s greatest profusion—2012 statistics place the number of photos uploaded to Facebook alone at three hundred million per day—it has begun appearing to teeter on brink of exhaustion. Everything, it often seems, has already been catalogued in the Internet’s vast Borgesian library of images, or soon will be. This sense, whether true or not, appears to have provoked a number of the artists in the show to either high-tail it towards analog processes and hybrid forms (Sam Falls’s ubiquitous fabric fades, the ones here made by wrapping hand-dyed bed sheets around boulders in Joshua Tree and leaving them to blanch in the desert sun) or to engage in self-reflexive analysis of the rapidly shifting image culture in which they find themselves (Oliver Laric’s Versions videos, widely known in Europe, which examine the ontologically destabilizing nature of copies, bootlegs, and remixes).

Rabih Mroué, Blow Up 4, 2012. Courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut / Hamburg.

Tellingly, neither Falls’s fades nor Laric’s videos fit comfortably in the traditional category of “photography,” an assessment that could be made about many of the best works in the show. This, of course, is to the curators’ credit, but it raises a serious question for ICP and institutions like it around the world: with the medium chafing against its historical constraints and its boundaries becoming increasingly blurred, isn’t it time, once and for all, to tear down the barriers that have kept photography from expanding its territory? In short: is the “photography museum” necessary?

Chris Wiley is an artist and writer. His work was recently on view in the exhibition Lens Drawings at Marian Goodman Gallery, Paris.

A Different Kind of Order remains on view at the International Center of Photography through September 22.

August 1, 2013

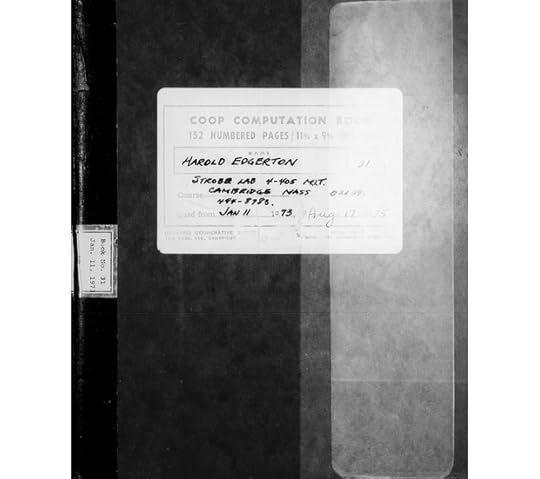

Harold E. Edgerton—”Doc” Edgerton and His Laboratory Notebooks

By Jimena Canales

Front cover of notebook 31, in use January 11, 1973–August 17, 1975.

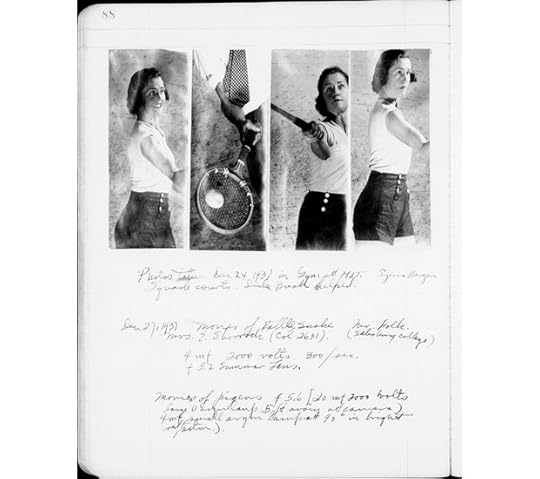

Page 88 from notebook 8, in use June 1, 1937–April 16, 1938.

Page 47 from notebook 1, in use June 18, 1948–February 7, 1950.

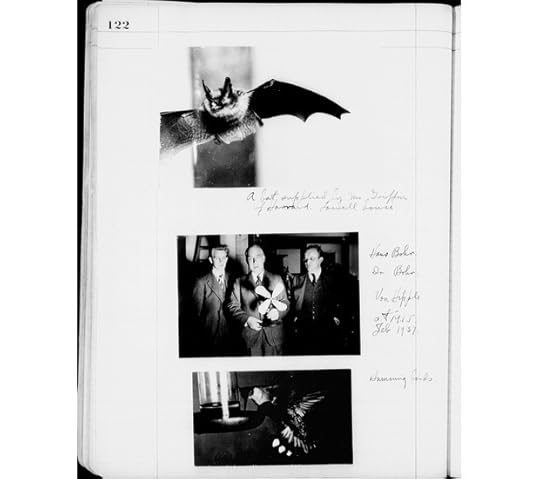

Page 122 from notebook 7, in use April 28, 1936–May 27, 1937.

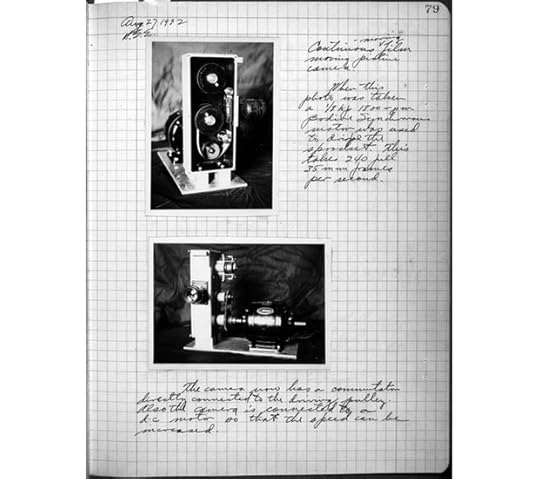

Page 79 from notebook T-3, in use January 20–July 13, 1932.

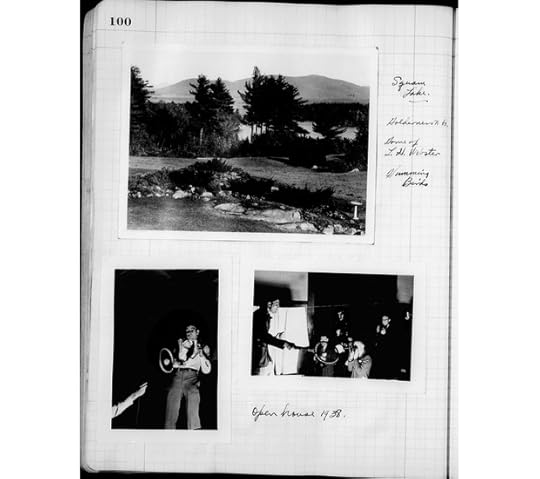

Page 100 from notebook 9, in use April 18, 1938–June 12, 1939.

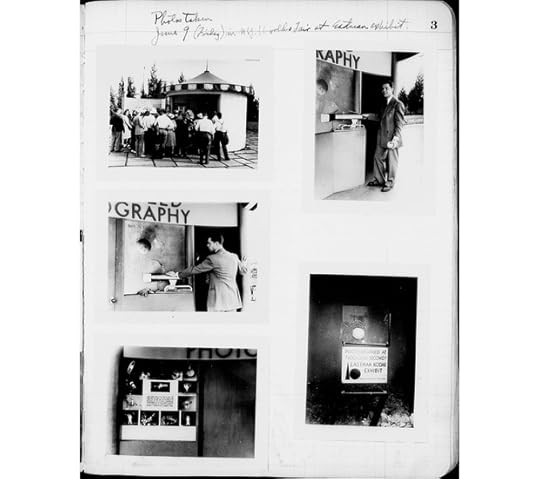

Page 3 from notebook 10, in use June 13, 1939–September 17, 1940.

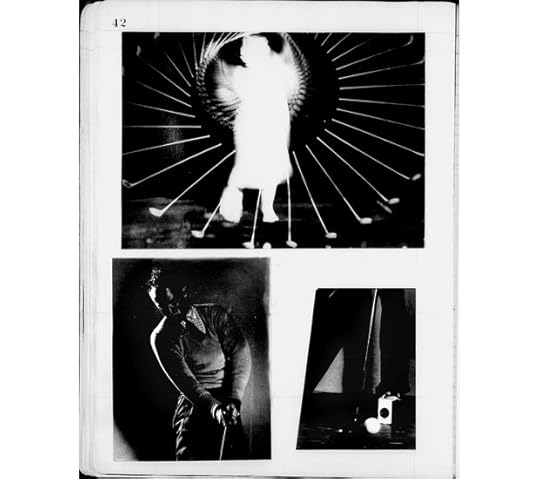

Page 42 from notebook 9, in use April 18, 1938–June 12, 1939.

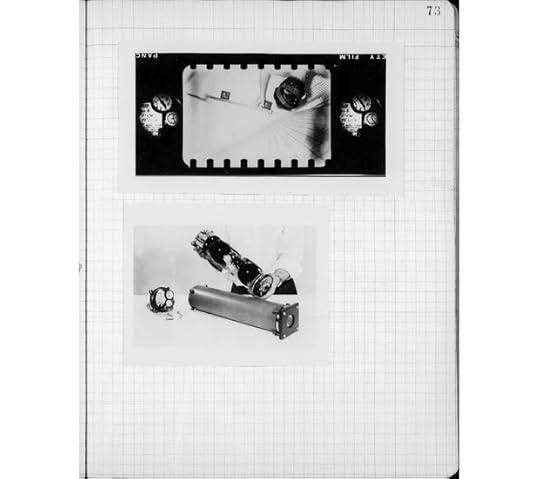

Page 73 from notebook 25, in use April 29, 1938–May 14, 1960.

Page 78 from notebook EE, in use December 8, 1948–April 8, 1951.

“Let a cannon-bullet pass through a room, and in its way take with it any limb or fleshy part of man.” This dramatic scenario was envisaged by the great Enlightenment thinker John Locke in 1689. The bullet, he reasoned, “must touch one part of the flesh first, and another after, and so in succession.” But the action would happen so instantaneously that no one would be able to “perceive any succession, either in the pain or sound of so swift a stroke.” Our rational minds tell us that rapid events occur in a certain order, even though this order cannot be perceived. Since Locke’s early speculations, generations of researchers have worked hard to understand an increasingly fast-paced world. With the help of electronic flash, photographers were able to arrest Locke’s imagined projectile in midair: in the 1930s, Harold E. “Doc” Edgerton, working at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, captured a rifle’s bullet flying at the vertiginous speed of 2,700 feet per second. The first use of flash is usually attributed to one of the inventors of photography, William Henry Fox Talbot. In 1851 Talbot used a simple electric spark to illuminate a moving target—a page of the London Times that was pinned on a rapidly rotating wheel. To his amazement, the resulting photograph was legible. At the turn of the century, the British physicist A. M. Worthington used sparks to illuminate splashing drops, and in France during the 1920s the Seguin brothers developed the “stroborama”— a machine made first with mercury and then with neon arc lamps. As scientists extended the field of flash illumination beyond the spark, they increased the range of their visual studies.

Edgerton’s first announcement of strobe technologies appeared in a 1931 issue of the journal Electrical Engineering. James R. Killian, a young science writer (later president of MIT and one of Dwight Eisenhower’s most trusted scientific advisors), was immediately fascinated by strobe lights. For more than forty years, Edgerton and Killian worked as a team: one taking the photographs and the other writing about the “meaning of the pictures.”

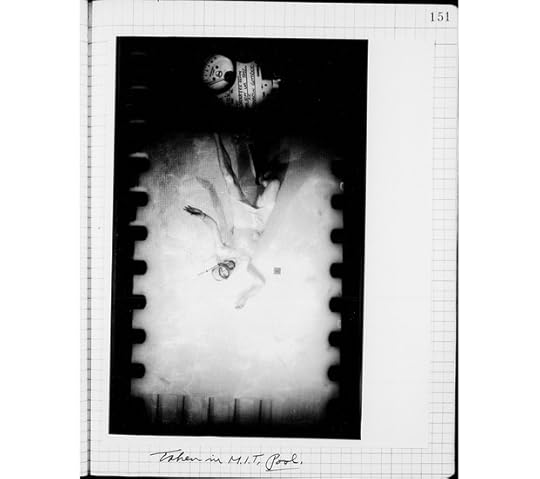

Page 151 from notebook 26, in use May 14, 1960–January 18, 1962.

In 1932 Edgerton’s images were published in Technology Review, a student-run MIT journal edited by Killian, who also wrote the preface to Edgerton’s first book about strobe technology, the handsomely illustrated Flash! Seeing the Unseen by Ultra High-Speed Photography (1939). When the United States joined World War II, Edgerton went on active duty; his night-reconnaissance work (using a 40,000-watt-per-second xenon flash) won him the Medal of Freedom. Upon returning home, he cofounded a highly lucrative defense-contract business from which he and his partners made a munificent living. Among their many endeavors, they developed a shutterless “rapatronic” (“rapid” and “electronic”) camera that was able to photograph the first stages of superfast nuclear explosions. In 1954 Killian and Edgerton republished Flash!. The original 1939 edition had included a photograph of a golf club hitting a ball; in the later volume this image was replaced with one of an atomic bomb explosion. While much had changed during a decade and a half of war and Cold War, Killian’s preface to the book was unaltered. Edgerton was, Killian noted there, “first of all a scientist and an electrical engineer, investigating, measuring, seeking new facts about natural phenomena.” Nonetheless, Killian also insisted that “these pictures are not only facts, but new aesthetic experiences,” which he compared to Edward Weston’s cypress trees and rocks, Edward Steichen’s sunflowers, and Alfred Stieglitz’s clouds and hands. He described Edgerton’s images as “literal transcriptions” of nature, broadly fitting within a realist theory of representation. They were, Killian asserted, “scientific records” written in a “universal language for all to appreciate.”

For Edgerton himself, strobe photographs were something else: records of the unforeseen and the unexpected. As he would put it decades later: “A good experiment is simply one that reveals something previously unknown to the student.” Many aspiring young engineers arrived at his MIT Strobe Lab believing otherwise: “Some students expect the results to prove the initial assumption, but I have always empathized with the student who sees new discoveries and knowledge that were not anticipated flowing from the laboratory.” According to Edgerton, there was “no such thing as a ‘perfect’ result or a complete study of the phenomenon.” His laboratory notebooks, filled with notes, handscrawled diagrams, and snapshots documenting his work, reveal the flowing stage of production—often referred to as “science in action”—which belies the static, “ready-made” outcome presented at the end. In contrast to the published photographs, those in his lab notebooks show a different behind-the-scenes spectacle: most interestingly, scientists (including Edgerton himself) working their machines. Killian was not concerned with the production process of science or with unexpected results that could suddenly surface in real time. For a number of like-minded thinkers—including Aristotle and Albert Einstein—time was as predictable as space. Edgerton’s machines “manipulate time as the microscope or telescope manipulates space,” Killian wrote. Modern science “ enabled us to see and understand by contracting and expanding not only space but time.”

Edgerton was not as optimistic as Killian. “Although I’ve tried for years to photograph a drop of milk splashing on a plate with all the coronet’s points spaced equally apart, I have never succeeded.” But he was hardly disappointed: “In many ways, unexpected results are what have most inspired my photography.”

Page 46 from notebook 19, in use June 18, 1948–February 7, 1950.

Edgerton expected the unexpected. In 1952 came an ultimate case in point: in approximately ten nanoseconds, one of the handheld cameras he and his associates had developed captured the initial stages of the first hydrogen bomb explosion, which obliterated Elugelab Island, part of the Enewetak Atoll in the Marshall Islands of the Pacific. Even those who had witnessed atomic tests were stunned by the bomb’s capacity for destruction: the explosion was more than twenty times the size of the Hiroshima fireball. Not only was Elugelab vaporized, but life on the surrounding islands was destroyed. Radiation blanketed most of the atoll, and hundreds of natives expelled from the island were left with nowhere to return to. As in Locke’s seventeenthcentury description, the pain on the ground did not match with the knowledge of the succession of events—this time on a scale never before imagined.

Jimena Canales is associate professor of the history of science at Harvard University. She is the author of A Tenth of a Second: A History (University of Chicago press, 2010) and numerous articles on the history of science, film, photography, art, and architecture.

All images courtesy MIT Libraries, Institute Archives and Special Collections, Harold Eugene Edgerton Papers, Cambridge, Massachusetts. All rights reserved.

July 25, 2013

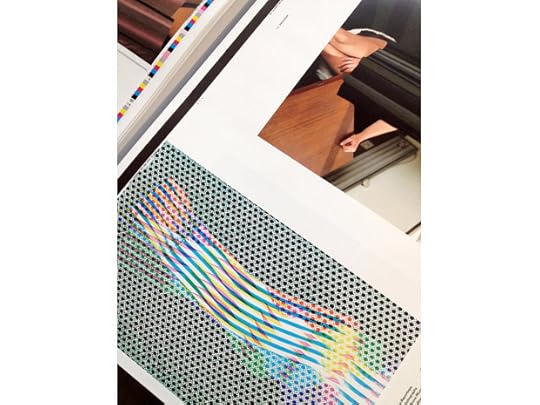

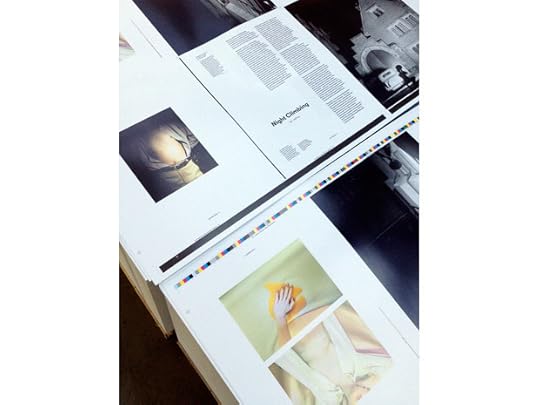

Sneak Peek: Aperture Magazine’s Fall Issue

Here’s a first look at the Fall 2013 issue of Aperture magazine. These images were taken on press this summer at Optimal Media in Röbel, Germany. The Fall issue, which is loosely organized around the theme “Playtime,” features work by Christian Marclay, Sophie Calle, Erwin Wurm, and Saul Leiter, among others, plus contributions by artist Tim Davis, photo historian Robin Kelsey, film director Mike Mills, and many more.

Not yet a subscriber? Sign up before July 29 to receive the Fall issue in your mailbox this August. The issue’s full table of contents, with selected articles available to read for free, will be placed live on the website in August.

All images courtesy Scott Williams, A2/SW/HK

Video: The Fine Art Photo Market from Birth to Today

Last April, the Association of International Photography Art Dealers held a series of panel discussions in conjunction with its annual AIPAD Photography Show. Among the topics discussed was “The Fine Art Photo Market from Birth to Today.” Noting that the transformation of photography in recent decades has been nothing short of revolutionary, the panel explored how developments in the field have been driven by the marketplace.

Speakers on the hourlong panel, which you can watch in its entirety in the video above, included Catherine Edelman, of Catherine Edelman Gallery, Chicago; Celso Gonzalez-Falla, chairman of the board, Aperture Foundation; Duane Michals, artist; and Susanna Wenniger, senior specialist, photography, Artnet. The moderator is Jill Arnold, director, business development, AXA Art Insurance Corporation.

July 24, 2013

David Horvitz’s Sad, Depressed, People

Installation view at Recess, New York.

Attention New Yorkers: Are you feeling sad? Depressed? Even if not, can you plausibly fake it? If so, you may wish to visit Recess, the artists’ workspace located in Soho at 41 Grand Street. Artist David Horvitz is in residence there through tomorrow at 1:00 p.m. He’s shooting portraits of people “acting out stock depictions of sadness and depression” as a continuation of the project collected in his 2012 book Sad, Depressed, People. As the artist says: “This is a fake sadness. It is a superficial depression. One sold on stock sites. A sadness that has been hijacked and auctioned off….”

Even if you can’t make it in time to pose, the show remains on view through August 10, and Horvitz will present a 35-mm slide show of the images in the series he has made to date. Paired with Horvitz’s presentation is a related project by artist Penelope Umbrico. For more information, visit the Recess website.

July 23, 2013

Video: Richard Renaldi, Chris Boot on Touching Strangers

Richard Renaldi spoke with Chris Boot last week on the recent progress that has been made on the Touching Strangers project, upcoming plans to shoot in New Mexico, Arizona, and Los Angeles, and the impact of the overwhelming support—via Kickstarter and elsewhere—on the growth and future of the series, which includes expanded plans for the photobook and an exhibition at Aperture Gallery.

Richard also offers a look at the 17-by-22-inch print Jeromy and Matthew, 2011, which will be available exclusively to Kickstarter supporters who pledge at the $1,500 level and above before August 5.

Jeromy and Matthew, 2011, Columbus, OH, from the series Touching Strangers. Available in a limited edition of 15, exclusively through Kickstarter.

July 22, 2013

Embedded Images

By Susie Linfield

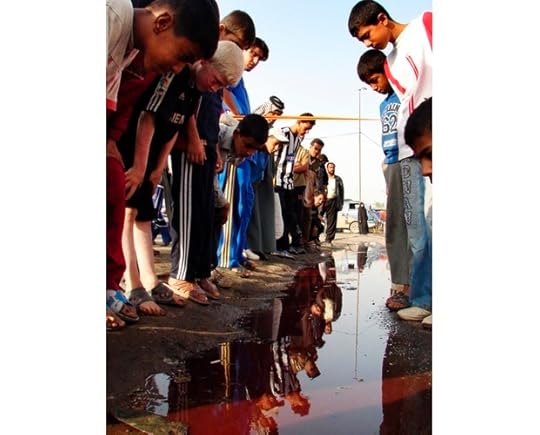

Ghaith Abdul-Ahad, An Iraqi boy celebrates after setting fire to a damaged US vehicle that was attacked earlier by insurgents, Baghdad, April 4, 2004. © Ghaith Abdul-Ahad

Julian Stallabrass describes his anthology Memory of Fire: Images of War and the War of Images as comprised of “pairs of loosely associated essays and interviews.” Stallabrass is an unusually thoughtful photography critic, but this is an overly generous description. Reading this anthology—many of whose pieces date from 2008, and some of which were previously published—is like trolling through a flea market looking for gems. The book mounts no sustained argument, or arguments; instead, it covers—in a fairly haphazard fashion—such issues as the role of embedded photographers; the use of torture in the wars in Afghanistan and, especially, Iraq; and the ways in which technological changes are affecting the reception of photojournalism and the work of photojournalists. Still, I like flea markets, and there is enough of value in this volume to make it worthwhile to anyone interested in the contemporary challenges of war photojournalism.

The best parts of this book are its surprises. Rita Leistner, a co-author of the 2005 volume Unembedded, mounts a surprising defense of the much-maligned practice of embedding, which she has practiced; she also notes, though, that she always felt “queasy and a little dirty” watching checkpoint interrogations of Iraqi civilians by American troops. Ashley Gilbertson, who for years has taken extremely powerful images from Iraq and Afghanistan for the New York Times, bluntly defends the practice—and the importance—of showing these wars from all sides, including that of American soldiers. Embedding, he explains, is not “anything different from what we normally do. The reason to embed is . . . for the access, for that intimacy, to see what they see and to feel what they feel.” Another surprise is Welsh photojournalist Philip Jones Griffiths—author of the canonical, 1971 anti-war book Vietnam Inc.—revealing that he “distrusted” the anti-war movement. As for the Vietnamese, he observes: “I was struck throughout the 1980s by the way the Vietnamese cared for one another and were kind to each other in a way that I never saw during the war years.” So much for the nobility of war.

The inadequacy of photography to portray the anguish of war is a theme that runs, if somewhat haphazardly, throughout this book. Stallabrass opens the volume by discussing “the apparent failure of photojournalism to describe the new circumstances of war and occupation,” and sets an exigent moral tone by noting how “easy [it is] to forget that bloody subterranean murmur”—the continuing carnage in Iraq and Afghanistan—“which should stain our whole experience.” Geert van Kesteren—who turned to Iraqis’ cell-phone pictures as a way of presenting and understanding the war from their perspective—rues the gap between photograph and experience, especially in his own work: “the stories that people were telling me were so extreme and the pictures I could take so mundane.” Similarly, Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin remark that the images they took of wounded British soldiers “failed and would always fail to represent any of the trauma.” But the helplessness that is sometimes expressed is, I think, exaggerated. The critic Sarah James complains that “the technological nature of today’s warfare has resulted in a war that is nearly impossible to document as it happens” and wonders if “the terror of death can no longer be photographed.” Yet she never makes clear why, when it comes to the wars discussed here, the sorrow is deeper and the meaning more occluded; photojournalists—at least thoughtful ones—have struggled with the gap between suffering and image almost since the medium’s inception. In fact, some of the photographs in this book—and elsewhere—refute James’s claims, which she states but does not substantiate. And why does she describe “today’s globalized, technological warfare” as “unfathomable”?

When it comes to technology, Memory of Fire throws a nice cold splash of water on the illusions of the techno-utopians. Trevor Paglen, who has photographed hidden military installations, warns against “equating Google Earth and Google image search with political transparency.” He’s refreshingly humble, too; his work, he explains, is an attempt to answer the question: “How do I . . . engage with . . . something that I don’t quite understand? The answer often has to do with trying to represent . . . that moment of incomprehension.” Gilbertson notes that the 24/7 news cycle created by digital cameras, laptops, satellites phones, etc. has become a nightmare for photojournalists: “I was told by mast-head editors at The Times. . . . ‘We’ll now judge you by what you put on the website and the blog’—which is crap.” The demand for immediacy has resulted in more—but, often, less thoughtful—images.

Memory of Fire addresses “images of war and the war of images” almost entirely in relation to the U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq: the wars sometimes (though I think too lazily) described as “imperialist.” Stallabrass is not interested, for example, in the carnage in Pakistan, where the Taliban continues to murder secularists, women, girls, Shias, and assorted other civilians; or with the long-running conflict in the Congo (dubbed “the world’s worst war” by the New York Times last year), where an estimated five million people have died from war-related causes and hundreds of thousands of women and girls have been raped; or with mass murder in Darfur and other parts of Sudan. The choice to focus on Afghanistan and Iraq is defensible: one can argue that, politically, these are the stories of our time. But even within this relatively narrow prism, the political analysis put forth—if implicitly—by Memory of Fire is inadequate. Comparisons are sometimes attempted between these recent wars to the one in Vietnam. But the history and politics of that country have virtually nothing in common with either Afghanistan or Iraq; and so when, in a group interview, van Kesteren asks Griffiths about the similarities, he is basically swatted away. “There are more parallels, paradoxically, with the Algerian war where the FLN discovered very quickly that there was no way to beat the French army but they could create a civil war with huge numbers of deaths so that people related all their problems to the invaders,” Griffiths explains—a devastating analysis whose implications for Iraq are ignored. Stallabrass quickly raises another topic.

Similarly, the murder of journalists and photojournalists by the Iraqi “resistance”—something the Vietnamese certainly did not practice—isn’t fully understood by Stallabrass. “We’re targets, we’re infidels,” Gilbertson explains to him. “We’ve got communiqués from [Abu Musab] al-Zarqawi [leader of Al Queda in Iraq] himself that say, ‘We’re going after the Western press.’ . . . They don’t want to reach out to us. In the case of Al-Qaeda, they just want us finished.” But Memory of Fire never places these attacks within the larger context in which they have occurred. The murder of journalists and photojournalists—one of the distinguishing characteristics of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan—can’t be separated from the murder of United Nations workers, humanitarian aid providers, schoolgirls, secularists, doctors, lawyers, teachers, intellectuals, feminists, Christians, Kurds, and anyone, including fellow Muslims, belonging to an “infidel” group. The Iraqi “resistance” recognized the humanity of no one other than itself; though Stallabrass briefly mentions this at one point, his book heavily emphasizes American-caused violence. (Leistner’s chapter is called “Embedded with Murderers.”) This violence surely needs to be documented, analyzed, and morally reckoned with. Yet Stallabrass’s emphasis places him, in 2013, in an awkward position; he never answers, or even broaches, the obvious question: Why has the Iraqi “resistance”—which Stallabrass describes as “a natural reaction to the savagery of the invasion and the occupation”—continued to murder fellow Iraqis, in appalling numbers, even after the U.S. withdrawal? Who or what is it resisting? Nor does describing sectarianism as a colonialist trope seem to adequately describe what is happening in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan—or, now, Syria.

Wissam Al-Okaili, Iraqi youth gather around a pool of blood left behind following a bomb blast in the Shiite neighborhood of Sadr City, Baghdad, October 30, 2006. © Wissam-Al-Okaili

What of the images in Memory of Fire? Though most if not all have been published before, they remain startling, horrifying, and moving—and refute the commonly voiced claim that repeated viewing hardens us to the pain of others. There is Griffiths’s frightening black-and-white photograph, taken in 1967 and reproduced from Vietnam Inc., of a group of Vietcong suspects—roped together at their necks, like animals or slaves—being led through a windswept field by two American soldiers to probable torture or death; and a much quieter photograph from 1981 of a Vietnamese woman, her face grotesquely scarred from napalm, beside the beautiful, smooth-skinned girl she adopted. We see Simon Norfolk’s 2003 photograph of Shalal Moussa Al-Zubeidi’s remains, which amount to a sad little heap of bones. (Al-Zubeidi was executed in Abu Ghraib by Sadddam’s regime in 1993; after Saddam’s overthrow, his family dug him up so they could move him to a proper grave.) There are Coco Fusco’s disarmingly simple, cartoon-like color drawings depicting the creepily intimate relationship between sexuality and torture, including one of a blonde, female interrogator—dressed in fatigues and a black bra—smearing menstrual blood on the face of a kneeling, handcuffed Iraqi prisoner in an orange jumpsuit. There is Gilbertson’s 2004 photo, taken from the vantage point of an American soldier, showing his huge gun pointed at a small Iraqi boy holding a white flag (actually, a little scrap of drooping cloth) and the older, frightened man next him: a succinct exposition of American power and Iraqi vulnerability. There is van Kesteren’s happier image, circa 2005–2007, of a Muslim Iraqi family celebrating Christmas in Baghdad: smiling forthrightly at the camera, they wear red-and-white Santa Claus hats. Despite the potential danger, the family insisted that “it would be a total insult if you did not show our faces.” (This image originally appeared in van Kesteren’s 2008 book called Baghdad Calling, a riveting document that depicts—and discusses—the violence in Iraq with greater complexity than Memory of Fire.)

And Stallabrass shows us, more than once, the torture photographs from Abu Ghraib; indeed, he opens the volume with one of these. It is several years since I have seen these pictures, but they have lost none of their power: to alarm, to repel, to shame. The smiles of the American soldiers remain as disgusting as the humiliation of, and attacks on, the terrified Iraqi prisoners; indeed, there is no better illustration of Rita Leistner’s apt observation that atrocity photographs “say more about the perpetrators than the victims.” It is the well-fed, well-clothed American soldiers—not the naked Iraqis—whom these pictures strip and, at the same time, so glaringly reveal.

Susie Linfield’s The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence has recently been translated into Italian and will soon appear in Turkish. She directs the Cultural Reporting and Criticism program at New York University.

Memory of Fire: Images of War and the War of Images is available now from Photoworks.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers