Aperture's Blog, page 190

October 17, 2013

Protected: Bruno Ceschel The Self-Published Photobook Workshop

This post is password protected. To view it please enter your password below:

Password:

1/1 Preview: Lesley A. Martin on Mickalene Thomas

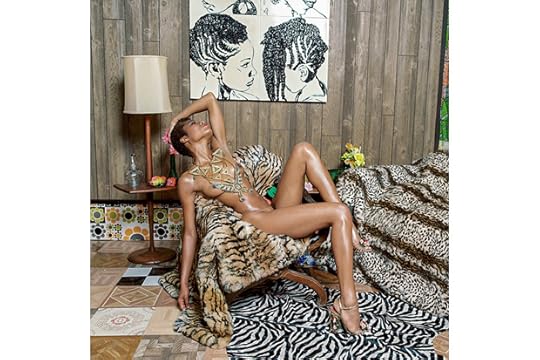

Mickalene Thomas, Liz and Chair with Zebra, 2013.

Mickalene Thomas is best known for her large-scale, multi-textured and rhinestone-bedecked paintings of domestic interiors and portraits. However, the Brooklyn-based artist has also identified the photographic image as an important touchstone for her work, both as source material and as a medium for creating work. In an interview in the catalog for her solo show at the Brooklyn Museum last year, Thomas described photography as something that “defines [her] practice. It provides a connection between all the works.” As a student at Yale, she took classes with photographer David Hilliard, who encouraged her to photograph herself and her mother—an experience that Thomas sees as an important pivot point for her as an artist.

Liz and Chair with Zebra (2013), available as part of Aperture’s 1/1 Auction, draws together several of Thomas’s foremost concerns and reference points. The work seems to draw equally from 1970s-glam, black-is-beautiful images of women such as Beverly Johnson, one of the first black supermodels, and actress Vonetta McGee (Shaft’s love interest in Shaft in Africa), in combination with Édouard Manet’s odalisque figures and the mise-en-scène studio portraiture of James Van Der Zee and Malick Sidibé. The interior space (including the titular “chair” and “zebra”) takes on as much of a performative role as does Liz, who is draped languorously across the image and adorned primarily with a large, Egyptian-style necklace. This corner of Thomas’s studio is an ongoing, palimpsest creation, a reappearing character in many of her photographs and echoed in her paintings; it is a site of physical collage, of the appropriation of textures, objects, and patterns. The space exudes a thick, cozy physicality from its layers of fur, rugs, wood paneling, and multi-patterned linoleum tiles—all of which are richly laden with sense-memory triggers of 1970s American rumpus-room semiotics.

Lesley A. Martin, Publisher, Books

Mickalene Thomas’s photograph Liz and Chair with Zebra will be available as part of the Aperture 1/1 Benefit & Auction on Monday, October 28. Pre-bidding has started online at Artspace. Find out more about the 1/1 Benefit & Auction and buy tickets here.

October 16, 2013

1/1 Preview: Denise Wolff on Aperture’s Instagram Silent Auction

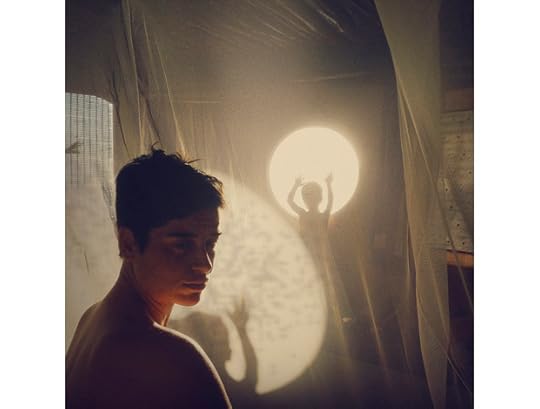

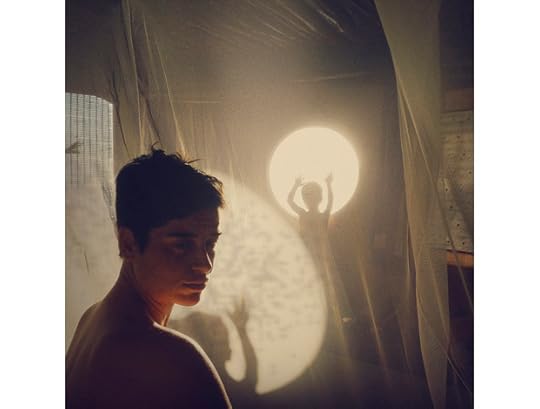

Christopher Anderson, Untitled, 2012.

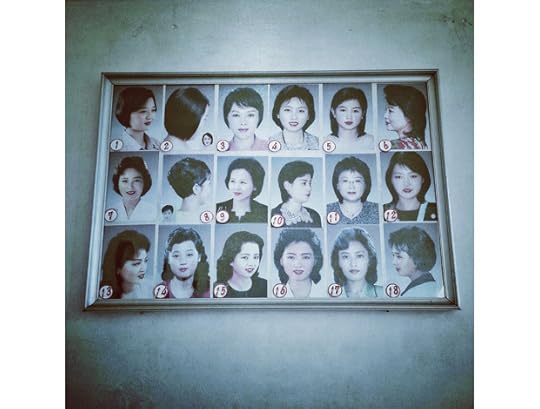

David Guttenfelder, DPRK Hairstyles, 2013.

Shane Lavalette, Black Raspberries, 2013.

Amy Elkins, Untitled, Drawing Breath, 2013.

Christina de Middel, Antipodes, 2013.

Barney Kulok, Queen Benazir, 2013.

Sara Cwynar, Studio Detritus, 2013.

Tierney Gearon, Untitled, 2013.

Massimo Vitali, The End of the Beach, 2013.

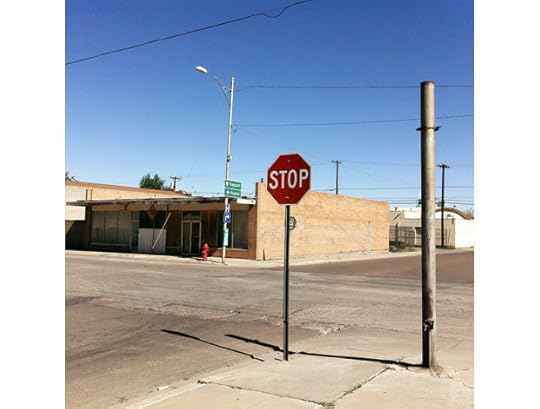

Stephen Shore, 3rd Street & Apache Avenue, Winslow, Arizona, September 19, 2013.

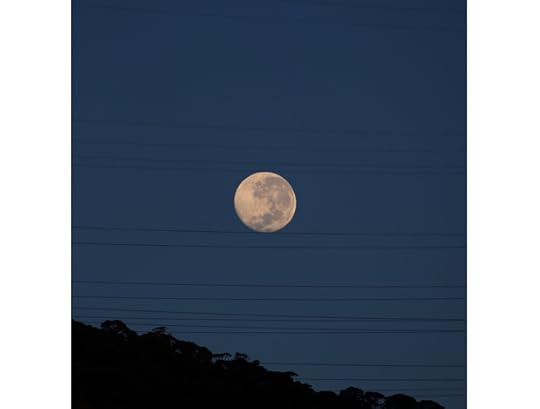

Vik Muniz, Full Moon, Rio de Janeiro, 2013.

Robin Schwartz, Dillie Coming Out From Her Bedroom, 2012.

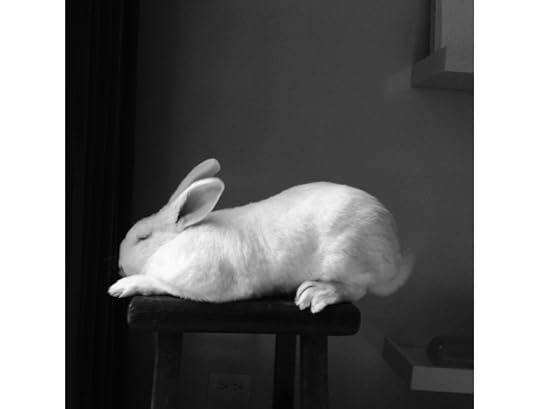

Maria Robledo, Cornilius , 2013.

It’s been exciting to see the images coming into the office from photographers all over the world for Aperture’s Instagram Silent Auction, part of the 1/1 Benefit & Auction taking place Monday, October 28. There will be nearly a hundred pieces available, all of which use—and transcend—Instagram’s familiar square format. The selection was curated by Kathy Ryan, avid Instagrammer and director of photography at the New York Times Magazine, and it includes a wonderful range of work: subjects and themes range from still lifes to animals, documentary to collage, personal to conceptual. Ryan has used her expert eye to hone a collection of photographs that feels unified but still attuned to each individual photographer’s aesthetic. The Instagram pieces start at an accessible price point, and bidding on them is a fun way to support Aperture’s education and visual literacy programs. Above is a selection of work I’m looking to bid on.

Denise Wolff, Senior Editor, Books

The above selection will be available as part of the Aperture’s Instagram Silent Auction at the Aperture 1/1 Benefit Auction on Monday, October 28, alongside work from more than eighty other artists. Aperture’s Instagram Silent Auction is curated by Kathy Ryan, Director of Photography, New York Times Magazine. Pre-bidding starts online on October 15 at 11:00 am. Find out more about the 1/1 Benefit & Auction and buy tickets here.

October 15, 2013

1/1 Preview: Annette Booth on Rinko Kawauchi

Untitled, 2013.

I first encountered the work of Rinko Kawauchi at Paris Photo in 2006. My mentor at the time had given me an assignment: to go around the fair and come back with just one artist’s name, just one body of work that moved me. It was a smart way to manage the endless maze of artworks. The bombardment of imagery meant I saw a lot but remembered little—until I discovered Rinko’s work.

The mystical beauty of her photographs struck me like nothing else I saw at the fair. With every deceptively simple image, Rinko accomplishes something all great photographers strive to do: she captures the universal and says something about the world as a whole with a single photograph.

Untitled (2013) is no different. In this divine image, pastel-pink flower petals curve gently inward to form soft sumptuous spheres, just barely open. Just outside of the frame, an ethereal white light bathes the bouquet in a heavenly glow. As always, Rinko’s genius lies in the way she can make a picture of a child, an egg, or a bouquet of flowers speak to wider experiences of childhood, nature, and the essence of life.

Annette Booth, Exhibitions Manager

Rinko Kawauchi’s photograph Untitled will be available as part of the Aperture Instagram Silent Auction at the Aperture 1/1 Benefit & Auction on Monday, October 28, alongside work from more than eighty other artists. The Aperture Instagram Silent Auction is curated by Kathy Ryan, Director of Photography, New York Times Magazine. Pre-bidding starts online on October 15 at 11:00 am. Find out more about the 1/1 Benefit & Auction and buy tickets here.

Ametsuchi , photographs by Rinko Kawauchi, is now available. An exhibition of photographs from the book is on view at Aperture Gallery until November 21.

Ametsuchi

Ametsuchi$80.00

October 10, 2013

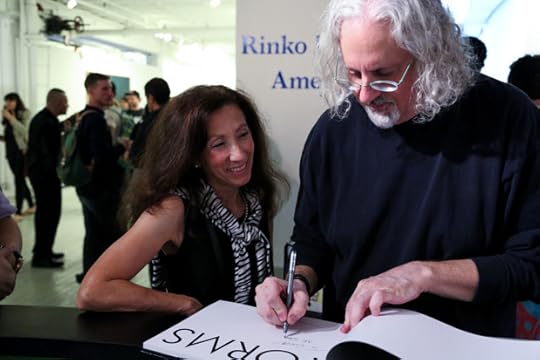

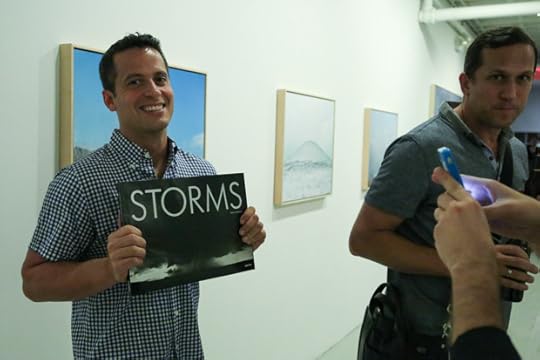

Storms Launch Party with Photographer Mitch Dobrowner

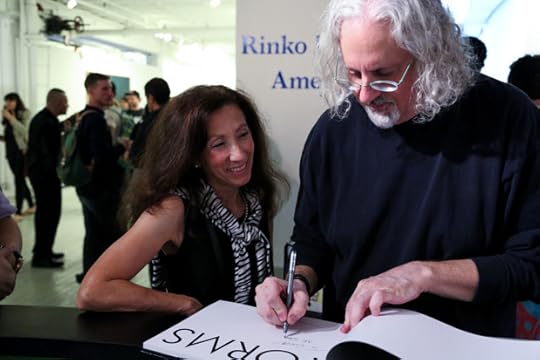

Photographer Mitch Dobrowner signs a copy of his photobook, Storms.

Storms book launch party.

Storms book launch party.

Storms book launch party.

Storms book launch party.

Storms book launch party.

Storms book launch party.

Storms book launch party.

Storms book launch party.

Storms book launch party.

Storms book launch party.

Storms book launch party.

Storms book launch party.

Storms book launch party.

Storms book launch party.

The launch party and book signing for Mitch Dobrowner’s photobook Storms (Aperture, 2013), a collection of awe-inspiring images taken throughout the American West, took place at Aperture Gallery on October 3. Since 2009, Dobrowner has been chasing storms with professional storm chaser Roger Hill and capturing nature’s monsoons, tornadoes, and massive thunderstorms on camera. The photobook is presented in a large-format edition and designed by Vince Frost, with an introduction by novelist and poet Gretel Ehrlich.

The launch was attended by special guest Raphael Miranda, NBC 4 New York weekend meteorologist and weather producer, and Dark & Stormy and Cyclone cocktails were enjoyed throughout the evening. In keeping with the tempest theme, the innovative Weather Live app was also on display and available for trial. The first thirty-five people to buy a copy of Storms that evening received a free download of the app.

Browse images from the event and book signing here or via Instagram (@aperturenyc).

—

Storms, photographs by Mitch Dobrowner, is now available.

Regular Price:

$50.00

Special Online Price:

$42.50

Pillar Cloud, 2011

Pillar Cloud, 2011$1,000.00

Protected: W. M. Hunt: Outsider / Insider Workshop

This post is password protected. To view it please enter your password below:

Password:

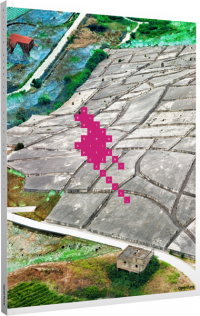

Site Specific: Olivo Barbieri in Conversation with Christopher Phillips

Olivo Barbieri’s Site Specific series is a ten-year project to record and reimagine over forty of the world’s cities from above, including Las Vegas, Mexico City, New Orleans, Rio de Janeiro, Rome, Shanghai, Tel Aviv, and Venice. On September 24, Barbieri was joined in conversation by International Center of Photography curator Christopher Phillips to discuss the series and the photobook of the same title, which was recently published by Aperture Foundation.

Phillips, who also wrote Site Specific’s introduction, spoke with Barbieri about the photographic processes the artist used to create his distinctive cityscapes, which began with the use of selective focus and tilt-shift techniques, and later evolved with the addition of digital manipulation.

The evening’s conversation also included a screening of Barbieri’s short film site specific_LAS VEGAS 05, followed by a Q&A and book signing. Browse images from the event’s reception and book signing via Instagram (@aperturenyc).

—

View “Olivo Barbieri in Conversation with Christopher Phillips, Part 2″ on Vimeo.

Site Specific

Site Specific

$75.00

site specific_LAS VEGAS 05, 2005

site specific_LAS VEGAS 05, 2005

$1,000.00

October 8, 2013

Recap: Workshop with Todd Hido

Sources and Influences, a workshop with Todd Hido, ran without a hitch over the weekend of September 21 and 22, providing students with a formidable lesson in how to shape one’s career as a photographer. A skilled professor, Hido lectured on his own experiences, principles, and methods. The course enabled students to draw inspiration not only from the precedent set by their instructor, but also from new perspectives on their own portfolios.

From the students:

“Todd was extremely generous sharing his experiences as a photographer and his vast knowledge of the history of photography. He also gave each student excellent feedback. This was a terrific experience!”

“Hearing Todd explain his sources and influences really got me to think about discovering my own.”

—

To find out more about workshops and classes at Aperture, click here.

#2077, from the series House Hunting, 1997

#2077, from the series House Hunting, 1997$1,750.00

September 30, 2013

Announcing the Paris Photo—Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards Final Jury

We are happy to announce the final panel of judges of the Paris Photo—Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards 2013:

· Maia-Mari Sutnik, Photography and Special Projects Curator of Art Gallery of Ontario (Toronto)

· Thyago Nogueira, Contemporary Photography Coordinator / ZUM Magazine Editor, Instituto Moreira Salles (Rio de Janeiro)

· Dr. Tobia Bezzola, Director of Folkwang Museum (Essen)

· Dr. Harald Falckenberg, Sammlung Falckenberg / Deichtorhallen Hamburg

· Gerry Badger, photographer, architect, and critic.

This jury will gather on Tuesday, November 12 from 3pm-5pm at the Grand Palais, to determine the PhotoBook of the Year Award (among 10 pre-selected books), as well as the First PhotoBook Award (among 20 pre-selected books). Winners will be announced on Friday, November 15 at 1 P.M.

Subscribe to Aperture magazine to receive your copy of The PhotoBook Review , which will feature the Paris Photo—Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards shortlist.

September 27, 2013

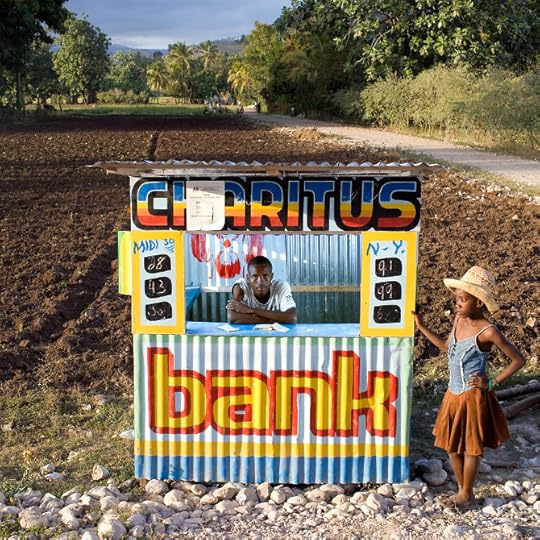

Haiti’s Invisible Orders

Paolo Woods has just inaugurated an exhibition of his photographs of Haiti at the Musée de l’Elysée in Lausanne, Switzerland. The show is the culmination of a three-year project documenting the institutions that have filled the void left by an absent or dysfunctional government. Photosynthese has published STATE, a book of the work, itself the product of a long collaboration between Woods and Swiss journalist-writer Arnaud Robert. Aperture magazine assistant editor Paula Kupfer speaks with Woods about his experience living and working on this fabled Caribbean island.

Sister Elsa is a catholic nun that runs the Collège Saint-Louis-de-Bourdon, a school for girls that has 800 pupils between the age of 3 and 15. © Paolo Woods/INSTITUTE

A group of American Christians from Watermark Community Church in Dallas (TX) come to pray with Haitians in the small village of Source Matelas, near Titanyen. They spend half a day in a village, talking trough a translator to the villagers, praying with and for them, hugging children and elders and evangelizing. A lot of emphasis is placed in “freeing the Haitians from Satan." This village gets a least two visits per week from mission tourists on a trip organized by Mission of Hope, a Christian NGO. Haiti 2012 © Paolo Woods/INSTITUTE

A borlette office. Haitians invest two billion dollars every year in these private lotteries – nearly a quarter of the GNP. They are often referred to as “banks” since the poor invest their money in them. Camp Perrin. Haiti

© Paolo Woods/INSTITUTE

Romel Jean-Pierre and Racine Polycarpe, two artists and members of the Timoun Rezistans, whose headquarters is on the Grand-Rue in Port-au-Prince. They are downloading their videos on Facebook in front of André Eugène’s sculptures that represent vodou spirits. Port-au-Prince. Haiti.

© Paolo Woods/INSTITUTE

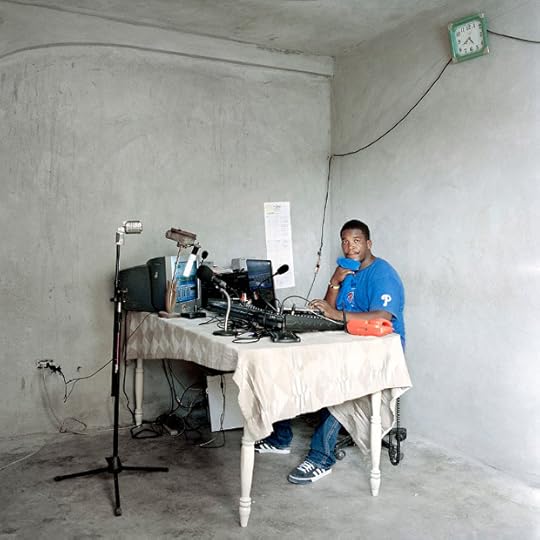

Radio Superdigital 96.9 FM. Wilkenson Charles endures the excruciating heat and wipes his perspiration with a handkerchief. Unfortunately the generator of the small communal radio is strong enough to power the antenna but not the AC as well. Les Cayes, Haiti, 2011 © Paolo Woods/INSTITUTE

Marianne Lehmann is a Swiss woman who moved to Haiti in 1957, several months before the election of François Duvalier. Over the years, she has built up one of the largest collections of vodou ritual objects in the world, including dolls from the Bizango secret society that contain real human skulls. Her collection has been exhibited in five European countries and Canada. Pétion-Ville.

© Paolo Woods/INSTITUTE

Paula Kupfer: Why did you choose to work in Haiti?

Paolo Woods: I got there in November after the January 2010 earthquake. Every photo editor told me, “You’re crazy, we don’t want to see any more images of Haiti; we are saturated.” This was interesting for me; it forced me not to take shortcuts, visually or in terms of content. I hadn’t planned to go for the earthquake; I’m not a news photographer.

The real drama of Haiti is not the earthquake. It’s a terrible event that brought a lot of destruction, but most of Haiti has not changed: the basic problems that existed before still endure. It was a catastrophic “fifteen minutes of fame”: for the people of Haiti, and for those who came to save Haiti. I was obliged, even more, to look at Haiti from a different perspective.

I decided to live there permanently. I worked on a project in Iran a few years ago and wanted to live there but it was not possible. The regime never granted me a long-term visa. So I decided that for my next project I wanted to live where I worked. It also gives you a completely different outlook on things.

PK: Was this your first visit?

PW: I’d been to Haiti before, when I was twenty years old, and it made a very strong impression. At the time, the work by photographers who’d worked in Haiti, such as Alex Webb, made a big impression on me. All the myths about the place contain some truth, but they become so big that they cast a shadow over everything else. And then you’re tempted to go and look only for that. It’s easy for photographers to confirm the visual images they already have in their head.

PK: What were your preconceptions, and how were they confirmed or dispelled? What was most shocking or surprising?

PW: I don’t think you can deny that Haiti is poor, that it is populated by black people, that it has a tradition of Vodou. . . . What I’m trying to investigate and show is that there are other, more interesting aspects—like its unique history—and how they have been perceived. Haiti’s history has scared the world.

A house made of tarps in Canaan. In the same zone, concrete houses, schools and orphanages are being built as emigration from the capital and the provinces increases. Croix-des-Bouquets. Haiti. © Paolo Woods/INSTITUTE

I’m still very shocked about the role of the American evangelicals there, and their verbal violence. My father was a protestant missionary, so I know this world well. But in Haiti you have a complex and different kind of approach by the evangelicals. It is really neocolonial. There is a complete misunderstanding, the presumption of where the right and wrong is, and the overrunning conviction that they’re right and the locals are wrong and slaves of Satan—it’s infuriating.

On another level, I was surprised that Haiti, a quite macho place, has a very lively gay community. Don’t get me wrong, Haiti is not gay-friendly per se; there has been quite a bit of recent violence against gays. But in general, religion in Haiti allows for some openness: someone who prefers men does so because his personal god or spirit—his Loa—is female, and when the spirit possesses and prefers men—this is accepted. It’s a workaround that allows gay men to be accepted by their family, by society.

PK: For State, the book of this project, you worked with Arnaud Robert, a Swiss journalist that has been working in Haiti for over a decade. Was it your idea from beginning to collaborate with a writer? Did you take inspiration from other historic collaborations, such as Walker Evans and James Agee or John Steinbeck and Robert Capa? How did your photographing and his reporting feed into each other?

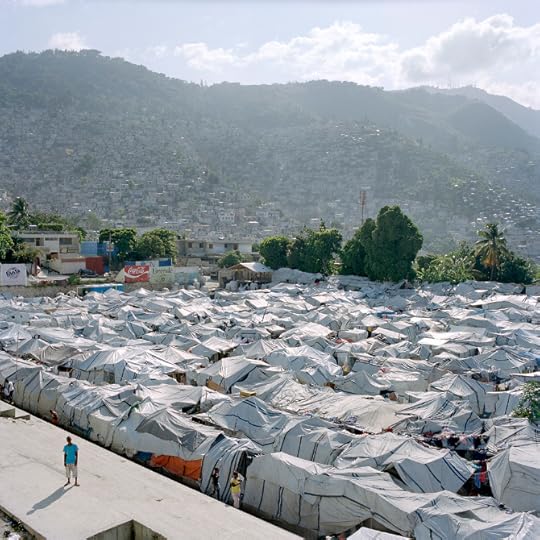

Tent city on a soccer field that belongs to a church. After the earthquake, inhabitants of makeshift districts (Jalousie, seen in the background) sometimes pitched tents in the camps to benefit from NGO help. The most visible camps in public squares were dismantled. Pétion-Ville. © Paolo Woods/INSTITUTE

PW: I’ve been obsessed with the relationship between text and images for a long time. In my previous books, developed with Serge Michel, we questioned how text and images work together in a longer form.

The examples you bring are some of the only ones that exist. I have to think also of Dorothea Lange and Paul Taylor. Collaborations between writers and photographers are very common in magazines but not in books. There are nice photo books, and coffee-table books with text that no one reads. Or you have books where a writer does an investigation and calls in stock photos.

I had lot of discussions with Arnaud; we don’t always agree. He had more experience and a lot more context, and we had to confront our thoughts about the place, how it’s organized, and how to put it in perspective.

PK: The book is organized according to key figures or institutions in Haiti, such as “Presidents,” “Owners,” “Whites,” “Substitutes.” Why did you choose this approach?

PW: I worked the structure out with Robert. He had written and investigated abundantly around the issues and institutions I was photographing. We tried to create a structure that would provide insight into how the society is organized. Because your first impression—this is important—is of complete disorder. But the more you work in Haiti, the more you learn that there are orders, invisible orders that structure the society. This is why it hasn’t collapsed, especially when the state, as we understand it, is not operating, or operating deficiently.

PK: “Substitutes” covers the role of NGOs, religious groups, and private companies that have sought to establish a sense of order in Haiti, often with contradictory initiatives and dubious results. One of the series is on the pèpè trade, the sale of second-hand clothing from the U.S. Many of the photos show Haitians wearing colorful T-shirts with ridiculous phrases in English.

PW: From a linguistic point of view, it’s a straightforward, indexical project; it’s one approach to understanding a phenomenon. It says a lot about Haiti, but also the world we live in, when all these Haitians are going around with the most terrible, obnoxious T-shirts, often originally produced in Haitian factories, shipped to the U.S., and sent back as donations. All this is the result of an agreement whereby no taxes are waged on clothes made in Haiti for export to the U.S.

Pèpè T-shirt, Haiti 2013. © Paolo Woods/INSTITUTE

The pèpè story went viral online some time ago. Many of the comments were making fun of Haitians. This clearly is not my intention. There’s always a view of misery, “the poor Haitians.” I hope viewers will go beyond that.

PK: How do you foresee this being received in a museum setting?

PW: Well, sharing the museum with Sebastiaõ Salgado is interesting; we have a very different approach to the world and I’m curious to see the reactions. A Haitian filmmaker will be making a film about this; he has followed me through Haiti and he will come to the opening in Switzerland, film the opening and people’s reactions, from Swiss bankers to NGO workers. In Haiti he will do the same.

PK: How will this work be shown in Haiti?

PW: As in all my projects, a big part has been bringing it back to where it came from. In the case of the Iran work, a collaboration with Serge [Michel], our big interest was to get the book back to Iranians. Of course, it’s easier to say something about Iran outside of Iran. We got a grant to get a book published in Persian but obviously couldn’t be printed in Iran. So we translated the book into Farsi, we had a PDF and hired someone—our fixer who’d left the country—to put the book on opposition websites, on the Facebook pages of prominent Iranians so people could download it for free. The New York Times correspondent in Iran, Thomas Erdbrink, told me it was one of the most widely read books; it was downloaded thousands of time, and this was one of the biggest satisfactions of the project.

For Haiti, this was also a consideration: up to this point, every Haiti story that we’ve published in foreign media we’ve given for free to the Haitian newspaper The Nouvelliste. We will bring the show to Haiti in 2014, and probably tour it to different locations around the country.

PK: Did you and Arnaud have a definitive mission or objective with this project?

I hope that people will ask themselves questions, that people can see different things in the photographs and understand the situation a bit more. The combination of text and images can be effective: some images inform the text, and sometimes it’s the opposite. It’s a lot more interesting to go through the micro to tell a story about the macro.

Ultimately, what I’m really interested is not a work, a book, or a show on Haiti. It’s a launching pad for a story that is more general, on North-South relationships, how certain forces in our economy work, and—this is probably the most important for me—how identity and state are shaped. I come from a mixed family identity, and I’ve always questioned what makes one person American, another German, and yet another Dutch, and how this shared identity between people enters into a relationship or not. Within a state organization, it’s even more complicated. Haiti and the Dominican Republic share a straight border, one traced by the colonial powers, and it divides two different countries, religions, languages, identities—and is a great vantage point to delve into these issues. I like to start with real stories.

—

Paula Kupfer is assistant editor of Aperture magazine.

Paolo Woods’s work is currently being featured at Photoville in Brooklyn, New York.

At 7pm today, Friday September 27, Woods will present this project as part of INSTITUTE Tells Stories. On Sunday September 29, Woods will appear in conversation with Fred Ritchin, also part of Photoville 2013.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers