Aperture's Blog, page 199

May 6, 2013

Interview with Sara VanDerBeek

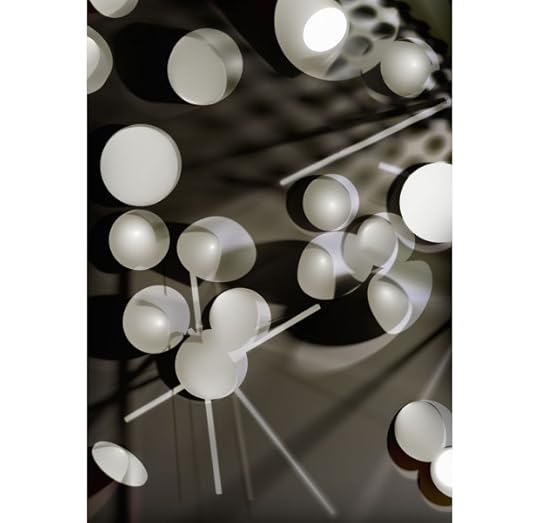

For her first solo exhibition at Metro Pictures, on view through June 8, New York–based artist Sara VanDerBeek made photographs at museums of antiquity and archeological sites in several European cities. These images have been given unique frames and are paired with cast-concrete sculptures similar to those VanDerBeek photographed for her earlier work. Brian Sholis, who wrote about VanDerBeek’s work in Aperture #202 , spoke with the artist by phone.

Installation view, Metro Pictures, New York, 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

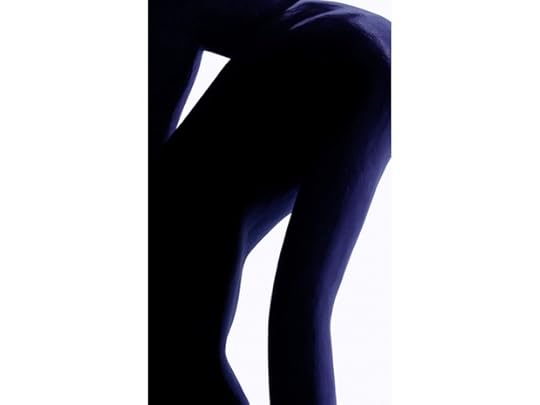

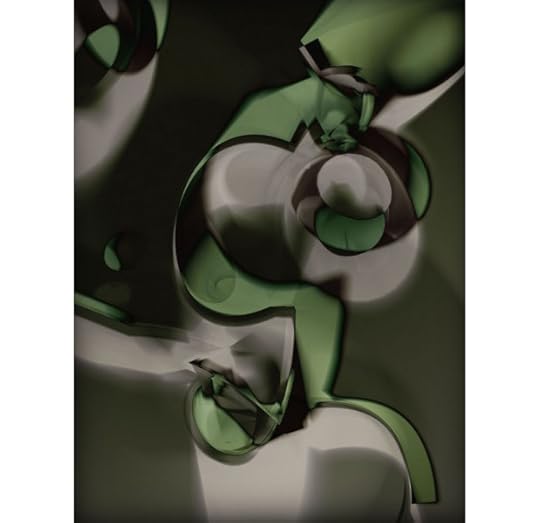

Sara VanDerBeek, Black Nude, 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Installation view, Metro Pictures, New York, 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Installation view, Metro Pictures, New York, 2013.

Sara VanDerBeek, Temple, 2010. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York. [Note: This work is not included in the present exhibition.]

Brian Sholis: In recent years you’ve made work in several US cities—Detroit, New Orleans, and your hometown, Baltimore. What are some of the differences you noticed when working in cities like Paris, Rome, and Naples?

Sara VanDerBeek: One big difference was in the way I navigated them. In America I chose to walk around and respond to the outdoor environment. I chose sites and spaces that resonated with the life of the city, or an impactful event in its recent past; for example, I made images of building foundations in the Lower Ninth Ward in New Orleans. But in Europe I worked mostly indoors, in various museums and collections. I’m not sure whether my familiarity with American cities allowed me to explore them with more confidence, or whether it was in part because I traveled to Europe with the specific purpose of exploring some of these pre-eminent collections of sculpture.

I will say, however, that I feel like history—as a larger, more abstract idea, as something taught and learned—suffuses European cities and museums, whereas a more specific and tangible history is present in the surfaces of American cities. That’s part of why I chose to focus on the ancient and neo-classical sculptures that are the subjects of some of the photographs in this exhibition. I wanted to explore figures that are already iconographic. Although they are three-dimensional, I think of them almost as images. I did engage and connect with the contemporary life of these European cities—I met and befriended a number of young artists and curators, and was very intrigued by their perspective on both the current and historical nature of their cities. But something about this whole endeavor led me to become focused on certain aspects of the past as they connected to the present. As I was photographing these sculptures and visiting different sites, I considered the changing depictions of the body, and how those depictions reflected larger changes in the cultures of their creation. The repetition of the figures was very intriguing to me, too. Most of all, I was interested in discovering, through the arrangement of the objects and the images in the show, a way to create an experience that in some way translated my original experience of visiting these sites.

BJS: Were you cognizant of being under the spell of these environments? Did you try to respond to them in terms other than those handed to you by art history books?

SV: I think “under the spell” is a good phrase. I was very inspired, or even mesmerized, at times. Sometimes the environments were dreamlike; at the very least they are different from what I have experienced of American institutions. Smaller collections in Rome, for example, allowed me extended time alone with the objects. I felt a connection to these figures, could begin to make sense of their gravitational force; I was able to move around them and study them intently. I was able to slow down, and I spent lots of time with each object so that my idea of them was formed out of direct observation and the camera’s view.

BJS: You also were not encumbered with a lot of equipment.

SV: I had a camera, but no tripod, and I used existing light. I tried to embrace the specific qualities of the objects emphasized by their environments, to understand how they were lit and staged. The tableaux are fascinating. However, after working in the museums, I did a lot of things during the printing and framing processes to alter the colors in the imagery, to try and re-create the imaginative, dreamlike way I experienced them.

I really enjoy the simplicity of this way of working. It was just me, with my camera, out in the world—I was trying to be present in the moment. This initial phase is the most exciting and invigorating part of the process; it’s when I get the ideas from which everything evolves, the sculptures, the overall installation, and the quality I hope to achieve in the final printed image.

Sara VanDerBeek, Roman Woman I, 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

BJS: Let’s talk briefly about the presentation at Metro Pictures. The show marks the first time you’ve exhibited a large number of your sculptures in New York. You have also made very specific decisions regarding framing. The show can be understood as an exploration of the relationship between images and objects. Though you were working simply, you are not presenting straight, “documentary” photographs.

SV: When I began exhibiting the sculptures I had previously used only for my studio-based photographs, I was encouraged to further consider the photograph as an object. I have often thought about how prints themselves fluctuate between image and object, and I wanted my photographs to have some other, possibly three-dimensional quality.

I had been exploring these questions during the last year, but hadn’t worked out the details until I began thinking about how classical sculptures had at one point been painted. They were themselves a meeting of image and object. The paint, its colors, was a means of communication, a literal and symbolic adornment. Today we see these figures without most of their color. They have changed over time, and to see them now is to be able to contemplate those differences.

Coloring the photographs by placing them behind semitransparent Plexiglas emulates the original act of coloring the sculptures. The Plexiglas I chose is quite a dark, deep blue. The figures become more like shapes or apparitions; they are semi-abstract textures and forms, though still legible as figures. I have also used mirrored glass for the larger, abstract photographs I’m presenting in one room at Metro Pictures. With them I’m trying to create a fleeting, ephemeral experience, one that mirrors what I felt while trying to capture particular moments in these sites. I wanted images that would change and fluctuate. Your reflection in the mirrored glass does that, but the color and texture you can see behind it will change, too. I keep going back to notions of dreams, of dreamlike images. Dreams, too, are specific but not fixed.

BJS: You mentioned earlier that this careful calibration of works in Metro Pictures’s three separate galleries is an attempt, on some level, to re-create your experience of these museum collections in Europe. Can you explain that further?

SV: I tried to take into account shifts in scale, and the viewer’s relationship to the objects and photographs as he or she moves through the galleries. Some objects are composed of human-scale modules, while other sculptures are a little bit larger than human scale, as were the figures I saw in Naples, at the National Archeological Museum. I was surprised to discover how large some of the classical sculptures were—in particular the figures that had adorned the Baths of Caracalla in Rome. I had never seen classical figures that large, and I hope that in my exhibition you get a sense of the proportion and mass that I felt when viewing these sculptures, as well as the quality and changes in your sense of scale as you move around them.

I have always been interested in how photography affects the reading of scale, time, and place. It can be disorienting or confusing to encounter a photograph of something, but it can also usefully enlighten some little-perceived aspect of real-life experience.

Sara VanDerBeek, Metal Mirror I (Magia Naturalis), 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

BJS: It was sometimes difficult to discern the actual size of the studio-based constructions you photographed earlier in your career. Can you speak about the contrasts between your early work, which was primarily in the studio, and your recent work, which has mostly taken place out in the world?

SV: I enjoy mixing different ways of working. Working out in the world involves a level of reactiveness, of being open to chance, that wasn’t as much a part of my earlier practice. When shooting in these European museums and gardens I was moving fairly quickly, responding to the qualities of light I encountered. Despite this dependence on context, the process can be as gestural as creating and staging tableaux in the studio. And it has changed my work in the studio, as well. Today when I create still lifes in the studio, I often work with natural light, shoot fewer frames. And I’m more open to trying alternate vantage points. For the early photographs of layered assemblages, made circa 2005 or 2006, I would shoot rolls and rolls of film. I’ve become a little bit more focused now, and I think that has come from lessons learned while shooting out in the world.

The studio now functions for me in a manner similar to my understanding of these classical figures: it’s a meeting point of different times. I take images, print them out, bring them into the studio, and consider them alongside sculptures or other, earlier photographs—it creates a “still life” of various pasts in the present. We all recognize that the present is imbued with the past; what I hope is that the exhibition itself communicates a sense of the feedback loops I experience while working, whereby sculptures generate images and images generate sculptures. That loop is itself a metaphor for the continually evolving process of thinking, making, and interpretation that is any artist’s or individual’s experience in life. We are continually trying to understand and process our past as we address ongoing issues. I feel these works are representative of that kind of grappling, of coming to terms with the foundations on which we build.

April 19, 2013

Coming Soon: The Paris Photo—Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards 2013

![2013_03_21_Photobook-awards[4]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1385795324i/7230026._SY540_.jpg)

![2013_03_21_Photobook-awards[4]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1385795324i/7230026._SY540_.jpg)

Next month Aperture and Paris Photo will launch the second annual Paris Photo—Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards, celebrating the book’s contribution to the evolving narrative of photography. This year’s call for entries will run May 6 through September 13, 2013, with winners to be announced at Paris Photo, November 14–17, 2013, and in The PhotoBook Review issue 005.

Stay tuned! More information and details for entry will be made available at the beginning of May.

April 17, 2013

New York Times Magazine Photographs in Santiago, Chile

Installation images courtesy of Stacey Baker and Annette Booth.

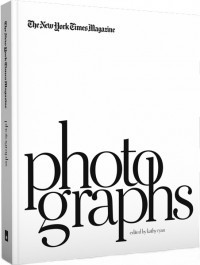

The latest installation of The New York Times Magazine Photographs is on view at Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, in Santiago, Chile, through June 15, 2013. The exhibition, curated by New York Times Magazine photo editor Kathy Ryan and Lesley A. Martin, consists of 126 works by thirty-five artists, including Lynsey Addario, Gregory Crewdson, Mitch Epstein, Nan Goldin, Annie Liebovitz, Mary Ellen Mark, Steve McCurry, and more.

For more details, and a full list of future venues for The New York Times Magazine Photographs, visit our traveling exhibitions page.

—

Aperture published The New York Times Magazine Photographs, edited by Kathy Ryan, in fall 2011.

The New York Times Magazine Photographs

The New York Times Magazine Photographs$75.00

April 15, 2013

Canon Rebels

Light from the Middle East: New Photography was on view at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, from November 13, 2012, to April 7, 2013. For more information, click here.

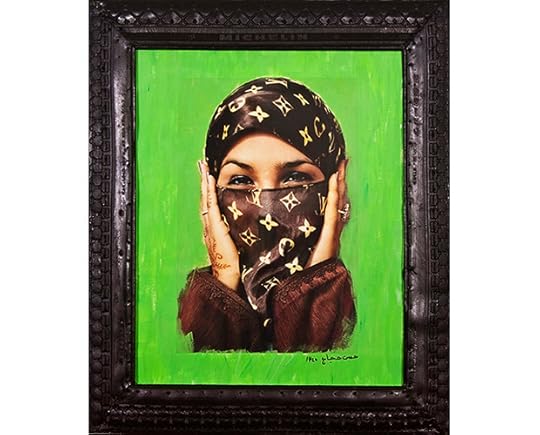

Hassan Hajjaj, Saida in Green, 2000. Copyright and courtesy the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

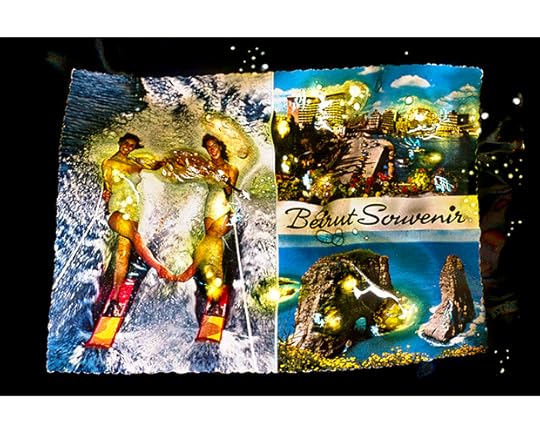

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, Wonder Beirut #13, Modern Beirut, International Centre of Water-Skiing, from the series Wonder Beirut, 1997–2006. Copyright the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, courtesy the artists and CRG Gallery, New York and In Situ / Fabienne Leclerc, Paris.

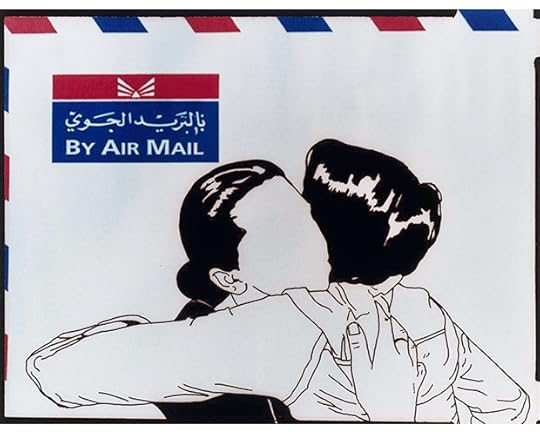

Jowhara AlSaud, Airmail, from the series Out of Line, 2008. Copyright and courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

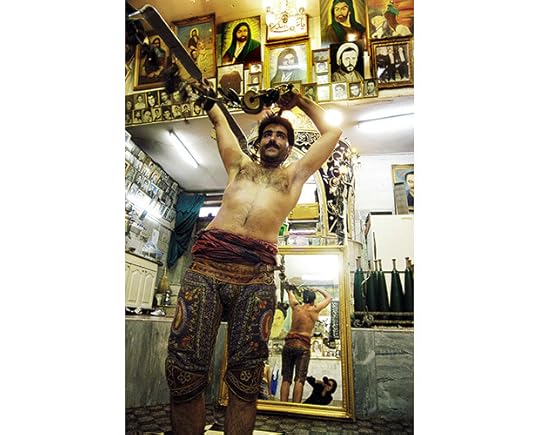

Mehraneh Atashi, Bodiless I, from the series Zourkhaneh Project (House of Strength), 2004. Copyright and courtesy the British Museum, London.

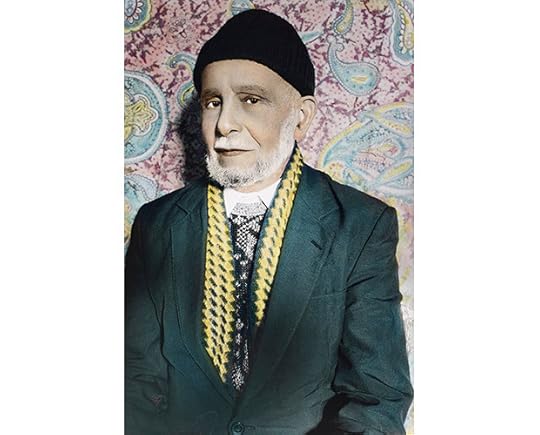

Youssef Nabil, detail from the series The Yemeni Sailors of South Shields, 2006. Courtesy and copyright the British Museum, London.

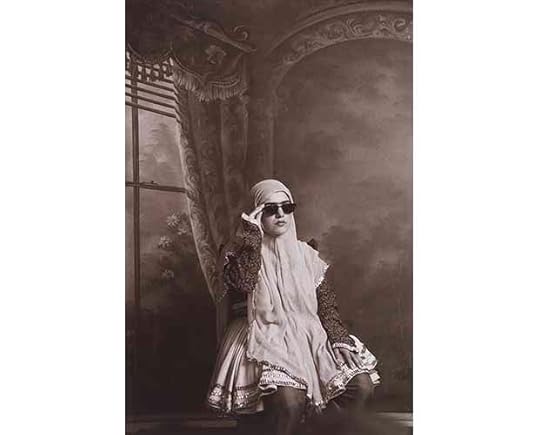

Shadi Ghadirian, from the series Qajar, 1998. Copyright and courtesy the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

From images of fists and banners in Tahrir Square to photos of resistance fighters in Syria to silhouettes of burkas amidst the ruins in Kabul, in recent years no area has been so recorded and defined by media photographs—whether hazy phone snaps or photojournalists’ work—as the Middle East.

Tampering with and staging photographs is common practice for artists today. As Light from the Middle East: New Photography at the Victoria and Albert Museum demonstrated, rebelling against the medium’s ability to represent reality, and the ensuing visual stereotypes, is even more relevant for photographers from the region. Regardless of whether the images were found in the “recording,” “reframing,” or “resisting” sections of exhibition, many are abstracted, distorted, redacted, burnt, or manipulated to resemble mid-century studio portraits. Fictive back stories for the images are imagined, or their subjects and scenes are minutely choreographed. In the exhibition’s best moments, nothing is what it first appears to be.

Very few of the photographs have a straightforward genesis, and those that do seem out of place. For his series Sufis: The Day of al-Ziyara (1995–2006), Syrian photographer Issa Touma spent ten years gaining the trust of Sufi pilgrims in order to photograph their annual procession and flesh-mortification ritual from the midst of the pilgrimage. His fish-eye lens revels in the spectacle. No challenge to the medium is mounted here, nor in Magnum alumnus Abbas’s images of militants, protests, and morgues during the 1979 Iranian revolution, a photojournalist’s diary that can hardly be considered contemporary. Such documentary records are powerful—testimonies taken by photographers immersed in the moments they capture. But their inclusion here simply highlights what most of the selected artists aren’t doing, and points to the fact that this is not merely an exhibition, but selections from a collection, and the needs of the two don’t necessarily correlate.

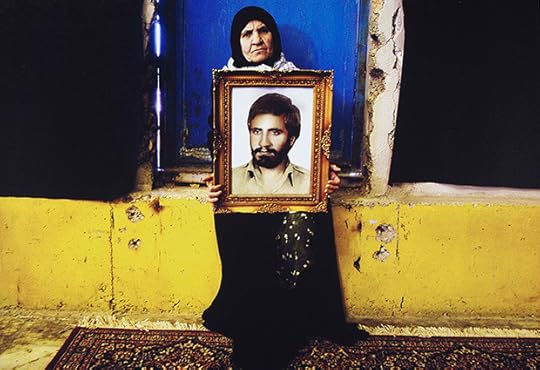

Newsha Tavakolian, from the series Mothers of Martyrs, 2006. Copyright and courtesy the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

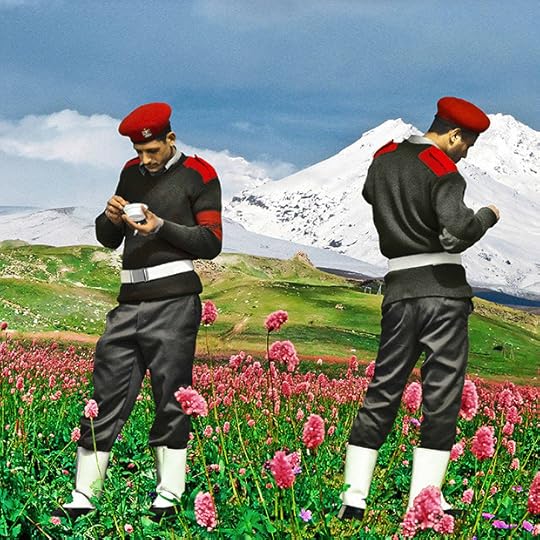

Up until this point, the V&A’s collection of Middle Eastern photography ended in the 1970s with Western views of the region, such as surveys of Iran by Henri Cartier-Bresson and Mary Ellen Mark. Recent funding, shared with the British Museum, has sought to correct this, and the institutions’ joint acquisitions make up the show. Yet while Abbas’s Iran Diary—and traditional forms of photojournalism—play a vital part in updating the collection, they feel tangential in the context of the exhibition. Abbas Kowsari, a photo editor at Tehran’s Shargh newspaper who worked previously at ten Iranian newspapers that have since been shut down, is a more fitting example of a photographer pushing the boundaries of photojournalism. Sadly he is only represented here by one image, a tightly composed close-up of a Kurdish combatant wearing a Bryan Adams T-shirt. The gaze of the Canadian singer is fixed on the weapons stuffed in the miltant’s belt, with Kowsari musing on the unlikely conflation of warfare and Western pop culture.

Elsewhere, however, manipulated images do not necessarily yield interesting results: often, the photographers fall too readily upon obvious symbolism or one-note juxtapositions. Sükran Moral’s Despair (2003) leaves viewers in no doubt about the desperate plight of a group of migrant workers huddled in a boat, even had the Turkish photographer not digitally perched nightingales on their shoulders and arms. Just in case we missed the disjunction between the symbol of hope and freedom and the wingless workers, the birds are gaudily colored in comparison to the black-and-white men. Meanwhile, Newsha Tavakolian’s scenes of elderly mothers clutching photographs of their young soldier sons killed in the 1980–88 Iran-Iraq war are poignant, tender protest images, but also rather familiar ones.

Too often ambiguity and subtlety are in short supply, or the theme or subject of a photograph too literally echoes its manner of execution. Amirali Ghasemi rebels against photography and the Iranian authorities by redacting snapshots of Tehran’s partying youth; John Jurayj’s images of blistered buildings, concocted by burning holes onto enlarged, found photographs and filling them with red Plexiglas, rather glaringly highlight the brutality of war.

Far more intricate and intriguing is a neighboring set of images from Lebanese artist duo Joana Hadjithomas and Kahlil Joreige, which takes as its starting point idyllic tourist postcards of pre-civil-war Beirut that are then stretched and abused. Their distorted and damaged but glossy and still seductive vistas quiver between dream and nightmare, past and present. The couple’s invention of an imaginary photographer commissioned to take the images, and the story that he burnt them during the civil war to reflect the destruction around him, adds another layer to the works.

Nermine Hammam, The Break, from the series Upekkha, 2011. Copyright and courtesy the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Authorship comes further under fire in excerpts from Walid Raad’s fabricated log of car bombs used during the Lebanese Civil War. (Raad lurks under not one but two fake monikers: the Atlas Group, proprietors of a photographic archive, and the historian Dr. Fakhouri.) Similar questions arise in relation to Taysir Batniji’s Bernd & Hilla Becher–inspired views of Israeli watchtowers, the latter series bearing a particularly curious relationship to its original inspiration. Just as the German photographers highlighted design similarities and singularities, so too does Batniji, yet his blurred, spontaneous snaps are anything but celebratory or carefully composed. They also are far more political: Batniji was forced to commission a local photographer to catalog the watchtowers, as the Gaza-born Palestinian is forbidden to travel to the West Bank.

Indeed, investigations of landscapes and architecture provide the show with its most memorable, most enigmatic images: Israeli photographer Tal Shochat’s lush but bizarre views of fruit trees at night, preened and lit as if they were models in a studio; Yto Barrada’s views of rubble and partially built homes in Tangier’s suburbs; and, most poignantly, Iraqi-born, London-based artist Jananne Al-Ani’s ghostly, hypnotic video Shadow Sites II (2011).

Taking Desert Storm–esque aerial photographs, Al-Ani challenges the long-propagated Western myth of the uninhibited Iraqi desert by gradually advancing in on these monochrome abstracted landscapes to reveal signs of human civilization. A sense of both lyricism and strangeness prevails: these settlements and traces are only visible when the sun is at its lowest point and shadows delineate their contours. Yet as soon as the markings are on the cusp of being decipherable, she dissolves to another shot. Al-Ani here succeeds in musing on photography—its reliability and legibility—where others around her falter. Her calling card is mystery.

Until recently, the few Middle Eastern artist-photographers celebrated in the West were Iranian (Abbas, Kaveh Golestan, Shirin Neshat, Shirana Shahbazi). The exhibition strives to correct this, and to update the collections of two major institutions. The problems plague this exhibition are those that plague every geographical survey: the pressures of covering every corner of the area; limitations on the number of prints from each photographer. But they were exacerbated here by a selection of artists that was often less than inspired.

Isabel Stevens works at the film magazine Sight & Sound and writes on photography and film for a variety of publications, including Source and The Wire.

April 12, 2013

Cihad Caner Wins the Photographic Museum of Humanity 2013 Grant

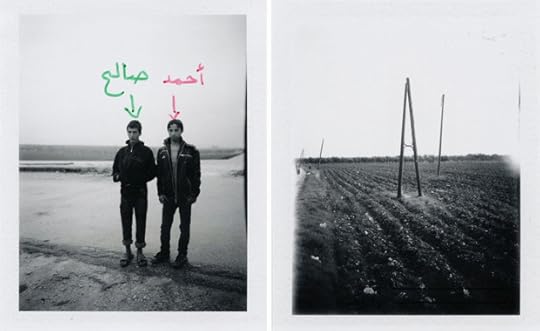

Cihad Caner, from the series Remaining, 2012

Instanbul-based photographer Cihad Caner has won the Photographic Museum of Humanity 2013 Grant for his documentary series Remaining, which tackles the ongoing civil war in Syria through portraits and environmental photographs. From March 2011 to the present, over sixty thousand people have died in the Syrian civil war, and seven hundred thousand have taken refuge in other countries. The individuals who remain in the region are the focus of Caner’s series, for which the photographer captures black-and-white portraits with Polaroid film, as well as images of surrounding landscapes, anonymous interiors, and urban decay. “This series is not about the explosions, neither about the conflicts, nor dead people, but about the effects of war,” says the twenty-three-year-old photographer. “It shows the relationship of the remaining people with the remaining places and their environments.”

Cihad Caner, from the series Remaining, 2012

A prestigious jury formed by Magnum photographer Martin Parr; Kira Pollack, director of photography at TIME; and Young Reporter of Perpignan 2012 winner Sebastian Liste selected Caner’s series from a pool of over one thousand one hundred international submissions. Of Caner’s winning series, Parr commented, “Cihad offers a very fresh approach to dealing with the tired and depressing Syrian problem. By taking a side view and combining these elegant portraits and urban decay with text, he brings a fresh perspective that is most welcome.”

—

Currently in its inaugural year, the Photographic Museum of Humanity Grant is an international photographic contest organized with the aim of providing financial support for talented photographers and discovering new talents. For more on Cihad Caner and the Remaining series, visit Cihad’s Photographic Museum of Humanity Grant 2013 portfolio page.

April 10, 2013

Interview with Greg Allen

Greg Allen, a writer and filmmaker in Washington, D.C., has organized Exhibition Space , an exhibition at apexart in New York that revisits images, objects, and perspectives from the early days of the Cold War space race. Included in the show are a ten-foot-diameter re-creation of a Project Echo satelloon and two photographic series created for utilitarian purposes that blur the lines between science and Conceptual art. The exhibition is on view through May 8. For more on the overlaps between science, exploration, and photography, subscribe now to Aperture magazine in order to receive the forthcoming Summer 2013 issue on the theme of “Curiosity.” —Brian Sholis

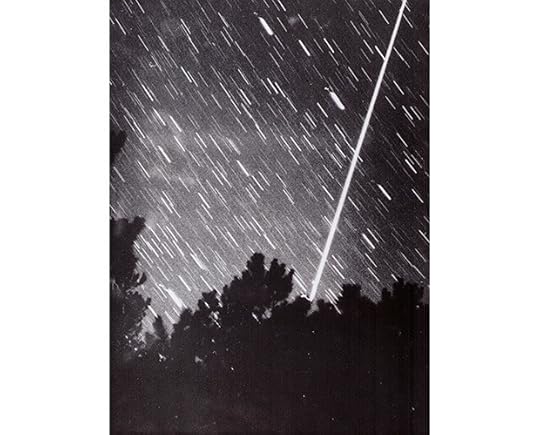

Photographer unknown, Echo I over South Dakota, August 31, 1960.

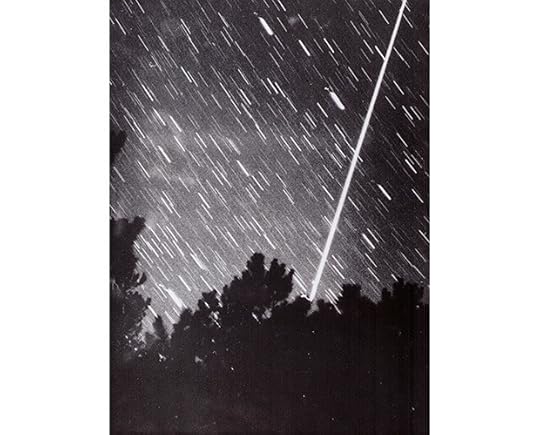

NGS-POSS1 Plate E-161 showing NGC-5792, a spiral galaxy, observed 27 Apr 1957, 00h44 - 01h40.

Unknown photographer, Project Echo Inflation Test, Weeksville, N.C., April 1960.

NGS-POSS Plate O12, taken November 18, 1949.

Photographer unknown, Edwin Hubble at Palomar Observatory's 48-inch Oschin Schmidt Telescope, ca. 1948.

Brian Sholis: Your exhibition uses scientific, press, and amateur photographs to demonstrate a shift in Americans’ conception of outer space, a shift conditioned in part by the escalation of the Cold War. Will you elaborate on this idea and tell us whether you see a connection to more explicit links between culture and Cold War propaganda, such as those uncovered by Frances Stonor Saunders [in her book The Cultural Cold War]?

Greg Allen: The short answer is yes, I do see links to the cultural Cold War, though I was originally drawn to these things largely for their aesthetic value. I was looking at how these scientific and astronomical artifacts might bear on the art historical discussion, in particular, of the beginnings of conceptual photography and minimalism.

Despite having written on my blog many times over the years about both the NGS–Palomar Observatory Sky Survey and NASA’s Project Echo, I had never considered either of them in terms of each other, nor of the Cold War, which was the overriding political dynamic of their time. Project Echo figures only marginally in it, but I found Walter McDougall’s 1986 book The Heavens and The Earth: A Political History of the Space Age, to be really useful for understanding how space became a site of political conflict.

BJS: How did that understanding of space evolve?

GA: In some real way after World War II, space became “the next frontier,” the natural successor to the American West, the landscape onto which American dreams of expansion and dominance were projected. But after the launch of Sputnik in 1957 and a few years of US failures and setbacks, space was seen as “the next front,” a site of Cold War conflict where US supremacy was uncertain or faltering. While there were direct military and technological implications for the space race, there were also significant propaganda impacts when space-related achievements were considered alongside cultural production as evidence of the superiority or failure of national ideological systems.

Saunders has a great analysis of how the US-Soviet ideological rivalries and de-Nazification efforts in occupied Germany laid the groundwork for the Cold War’s cultural competition. That’s the same milieu in which the Allies were each scrambling to secure for themselves as many German V-2 rockets and rocket scientists as they could. The US shipped back parts for hundreds of V-2s, as well as Wernher von Braun. NASA’s own official Project Echo histories don’t mention him at all, but von Braun was the first and most prominent advocate of the US launching a one-hundred-foot inflatable satellite into space for unabashedly propagandistic purposes. He called it “The American Star,” and he was confident it would sway the hearts and minds of Asia (i.e., China and India) toward the US cause.

McDougall makes a persuasive case that the US space program, led by civilians at NASA interested in science and exploration, was itself an ideological refutation of the Soviets’ attempted militarization of space. This also provided public cover, he argues, for an entire military/intelligence shadow space program, including the development of ICBMs and missile targeting systems, and the deployment of surveillance satellites. Though Project Echo satellites served multiple nontrivial roles in this evolution, I didn’t discover until working on the show that their propagandistic mission—to be seen by the entire world—wasn’t a side point: it was the main point.

Photographer unknown, Beacon satellites on display in the US Pavilion at Expo67, Montreal, 1967.

BJS: I want to pick up on your initial impetus to research these images, which shouldn’t be lost in the discussions of scientific and political imperatives. How might these photographs be understood as predecessors to Conceptual photography and Minimalism? Were you able to uncover any evidence that these images, which were widely distributed, impacted the thinking of artists whom we now consider part of the photographic and sculptural canon?

GA: In several years of archive diving I did find some connections between these projects and images and various postwar and contemporary artists, but no Rosetta Stone–style revelations. In the 1980s Chris Burden created a little-known proposal called The Moon Project that was basically a restaging of Project Echo as art, only bigger.

But I was really motivated more, I think, by the desire to question or expand the photographic and sculptural canon, not just to add to the footnotes of the stories that were already being written.

BJS: These photographs deserve consideration as aesthetic objects—

GA: —In the most basic sense, these prints and satellites are indeed extraordinary objects, extraordinarily made. They embodied the characteristics of and exerted major influence on the culture of their day. It’s not just coincidence that they happen to look like art, or rather, that art soon emerged that looked like them. Considered on their own terms and in their own contexts, these projects can bring a lot formally, aesthetically, conceptually, and ideologically to art discourse.

Take the Palomar Observatory Sky Survey, which is an archetype of the non-subjective, anti-aesthetic scientific photography that informed Bernd & Hilla Becher beginning in the mid-1950s. Indexicality, typology, obsolescence, mankind’s place in the world—these are all central elements of both POSS and the Bechers’ work. The timing is such that I don’t think the Bechers could have known or seen POSS in the 1950s. But I shouldn’t have been surprised to learn that it was overseen at Caltech by a German refugee astronomer, and thus shared the same socio-political foundation, 1930s German objectivism, that the Bechers consciously sought out. Maybe it’s the photographic equivalent of how Québécois forked from Old French, thus preserving some of its structure and vocabulary. And that’s all without really addressing the issues of seriality or the grid. And on a completely different plane, of course, there’s the sheer ambition and folly of deciding to take a picture of the entire universe. I mean, what artwork can measure up to that?

BJS: Douglas Huebler would announce his intention to do just that in the early 1970s.

GA: Yes. And the Echo satellite, meanwhile, even though it predates Judd’s and Morris’s concepts by almost a decade, seems like a “specific object” to me. It’s not—or not just—a case of “this looks like that.” Walking back the history of Project Echo, it turns out that visibility—direct experience with the object itself, in its space—was a the central point of the endeavor. Echo was an object made to be seen—and photographed—in space, from everywhere on earth. And on top of all that, the idea was first promoted by none other than Wernher von Braun as pure, unabashed propaganda.

Rather than influence, it’s context, and Echo makes me think of critic Michael Fried and Robert Smithson’s exchange over Minimalism’s theatricality and atemporality. Smithson wrote, “What Fried fears most is the consciousness of what he is doing—namely being himself theatrical,” an internally conflicted position that applies equally well to Echo’s spectacle. It’s funny, and kind of a bummer, actually, because though my affinity for Minimalism and Smithson was what drew me to Project Echo in the first place, the more I discovered about its history and politics, the more problematic Minimalism’s claims of objectivity became for me. I just kept thinking, “Man, they had to have known about all this.”

April 3, 2013

Thomas Ruff: Photograms for the New Age

For more than thirty years, German photographer Thomas Ruff has investigated the grammar and structures of photography, through his many celebrated series, Sterne/Stars (1989), maschinen/machines (2003), and cassini (2008)—to name just a few. After turning away from straight photography in the mid-1990s, Ruff has worked mainly with found imagery culled from a variety of sources—from print catalogs and scientific negatives to the Internet, from which he purloined pornographic images for his nudes series, which he began in the 1990s. More recently, he has turned his attention to 3-D imaging software to continue his investigations of the medium. For his newest project, Ruff has taken up a study of the photogram, updating the form for the digital era by creating his works in a 3-D digital studio environment and outputting the resulting images in the large scale he tends to favor. Michael Famighetti spoke with Ruff, who is based in Düsseldorf, by phone in February as he finished work on this new series in preparation for its debut at New York’s David Zwirner Gallery . That exhibition is on view now through April 27.

This article is included in the Summer 2013 issue of Aperture, which is organized around the theme of “Curiosity” and which hits newsstands on May 21. Click here to subscribe to Aperture magazine. Ruff is also featured in The Düsseldorf School of Photography (Aperture, 2010).

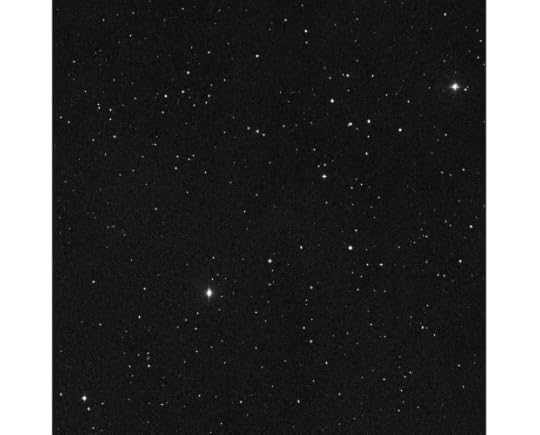

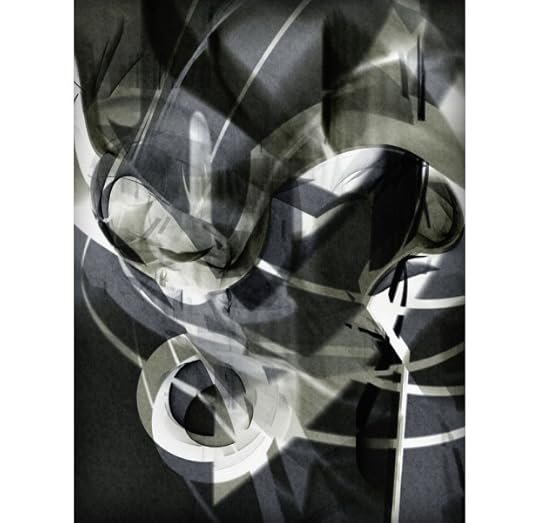

Thomas Ruff, phg.02, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York and London.

Thomas Ruff, phg.10, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York and London.

Thomas Ruff, phg.04, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York and London.

Thomas Ruff, r.phg.s.03, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York and London.

Thomas Ruff, r.phg.03, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York and London.

Thomas Ruff, phg.06, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York and London.

Thomas Ruff, phg.s.01, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York and London.

Michael Famighetti: Can you tell us about the process behind this new body of work? What were you after when you decided to produce photograms in a digital studio?

Thomas Ruff: The decision was quite simple. I have two photograms by Art Siegel in my collection and I passed by them again and again. Two years ago, I had the idea to begin making some of my own photograms. When I started analyzing how these photograms were made, I realized that it would be quite complicated; photograms are limited to the size of the paper and to the limitations of the black-and-white darkroom. You don’t have much color—only a brownish or bluish tone. And the other thing was if you put objects on the photographic paper and remove them, and then realize that these objects would have been better shifted to the left or the right, you have to start over again. You need a lot of luck to get a good photogram, so I considered how could I do it in a different way. I had already been working with a 3-D software on my series zycles, so I thought, maybe this is the right tool to try with the photograms. I developed a virtual setup: the paper on the bottom, and the objects—lenses, chopsticks, spirals, paper strips, all kind of objects—I put on the paper. There is a camera above, recording the paper, and then I set the lights with different colors.

MF: You have continuously investigated a range of mostly representational photographic types: the jpeg, the nude, the scientific image. What attracted you to the photogram as a form?

TR: The photogram is a kind of “pencil of nature.” It’s cameraless photography—you don’t see the objects but only shadows, which reminds me of Plato’s cave. It’s a very vague photography; you can’t recognize things very clearly but you recognize something. Soon I realized if I use too much color, it doesn’t look like a photogram, it just looks strange and abstract.

MF: The images here are reminiscent of László Moholy-Nagy’s experiments with color photograms from the 1930s. How active did you want such historical references to be?

TR: The goal was really to make a kind of “new generation” of the photogram. So it still should look like a photogram, but not old-fashioned. I tried different types of photograms: some with lenses, some with spirals. I want to experiment more with the possibilities of this kind of software to create different kinds of images. I can imagine that Moholy-Nagy would have been absolutely glad if he could have used my technology! You can do so much more than with the limitations of the analog darkroom. I am sure he would have loved the software.

MF: The “types” of photograms here are entirely determined by the objects?

TR: Yes, mainly by the objects. If you look at Moholy-Nagy’s photograms they show different typologies within the photograms. I wanted to make variations of these different types.

MF: Photograms are usually quite small—they are limited to the size of the paper available, as you mentioned. Will these images be on par with the usual large scale of your work?

TR: Yes, they will be really big.

Thomas Ruff, phg.06, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York and London.

MF: Why is large scale important?

TR: First of all, I wanted to break the world record of the size for the photogram! [laughs] The early photograms, from the 1920s and ’30s, are quite small, more postcard size. Photograms from the New Bauhaus school—by Art Siegel and his colleagues, for example—are approximately fifty by sixty centimeters. I work with the large format; I like the physical presence of the big size.

MF: You mentioned the connection between this new body of work and your zycles series, computer-generated abstract line drawings based on algorithms. Tthroughout your career you have worked in strictly delineated series. Is it common for one series to bleed into the next?

TR: Yes and no. I am using the same software, the same techniques—but one series doesn’t emerge from the other. It’s more like you have a Leica, and then you have a Linhof: a 4-by-5 camera, and then an 8-by-10 camera. They are just different tools, or cameras, or techniques. The output looks completely different.

MF: Much of your work investigates “systems” and the role of genre in photography. You’ve worked with many forms of found photography, from catalog to online imagery. Considering how much photography has transitioned in recent years—this explosion of imaging—do you see new systems and genres emerging?

TR: I see photography as a very classical medium, with of course all kind of genres—portrait, abstract, science photography, and so on. What I am also interested in right now is the negative, since it seems that it is going to disappear soon. When I ask my nine-year-old daughter, “What’s a negative?” she can’t say, as she knows only digital photography.

“Polaroid? What’s that?” she asked me some time ago. What interests me is the outcome of all these different kinds of photography and how they change our lives and our perception of the world. I just turned some photographs that I own into negatives, and they look strange. My interest in this process comes from working on the photograms—I make reverse photograms. And you still have these strange, old-fashioned darkroom techniques, like solarization, which I now also practice in the photograms series.

MF: How do you see photograms, or abstract images, shaping our perception of the world?

TR: The photograms are not so much about the perception and influence of photography in our daily lives. Maybe I just want to recall that artists used techniques in photography that enabled them to make completely artificial and abstract photographs and that these techniques are, unfortunately, nearly forgotten.

MF: You’ve taught at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, where you also studied. How does your interest in the history and evolution of photographic technologies come into play in the classroom?

TR: I’ve used a lot of different photographic techniques in the past thirty years. I realize there isn’t just one way to take a photograph, there are a thousand different ways—and that’s what I’ve taught the students. They should not insist on their beautiful Leica, or their Hasselblad, or whatever they use. The technique must result from the idea that you have—and you may have to develop your own technology to bring out the images. I’m not much interested in “straight” photography anymore. It has been practiced for more than 150 years, and most of it is too conventional. I’ve always wanted to go beyond the limits.

MF: But you are interested in photographic conventions. Why?

TR: I think photography is still the most influential medium in the world, and I have to deconstruct these conventions.

Thomas Ruff, phg.s.01, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York and London.

MF: Do you ever take pictures, in the traditional sense?

TR: The last photographs that I took in the traditional way, with an 8-by-10 camera and negative film, were architectural photographs of my studio some months ago. And, of course, if an idea for a new series requires a traditional analog photograph, I will use the camera again.

MF: Could you talk about the role of research in your work? Where does a project begin?

TR: If I see an image that attracts, upsets, or astonishes me—one that stays in my mind for a long time—I begin working. This is the starting point of the research: I try to find out how the image was created and in what context—historical, political, or social—the image belongs. After clarifying these questions I begin to create “my own” image, the image I have in my mind, the image that was triggered by the image I saw. Sometimes it can be done in a straightforward way, with a camera, but sometimes you need to reflect on how you can manage to make this technically. For example, when I had the idea of photographing the night sky, I realized that with my small telescope, I had no chance of getting high-quality images of stars, so I looked for an observatory with a big telescope where I could take the photographs myself. But they wouldn’t let me in. So I had to give up the idea of being the author of the photograph, and worked with large-format negatives from the observatory’s archive.

MF: It’s been written that when you were in high school you wanted to be either an astronomer or a photographer. Your cassini series connects the two occupations.

TR: I have an affinity for astronomy, so from time to time astronomical issues show up in my work. The cassini series consists of images of Saturn, its moons and rings, taken by a machine camera within the Cassini spacecraft. They are black-and-white photographs with an abstract quality that I really like. To highlight the abstraction, I colored these photographs so that they resemble a kind of “post-Suprematist” image.

MF: You’ve spoken of your interest in the writings of Vilém Flusser, whose ideas about imaging, written in the 1970s and ’80s, feel prescient today.

TR: [Flusser’s 1983 Towards a Philosophy of Photography] is a book I read twenty years ago. He was writing about the shifting of photography. There are a lot of different photographs, and different photographs have different intentions. Fine art, medical, propaganda, and of course the most influential image-production machine is advertisement. This transformation, let’s say, of the scientific photography into the art world, or advertising photography into politics (as seen in the last U.S. election)—this modification of images from one intention to another brings about interferences. The image, and the meaning of the image, changes.

MF: This notion of shifting contexts—and thereby shifting meanings—is central to your work. This is true with your nudes series, your first using Internet imagery. How does your image-collecting process work?

TR: I have a particular curiosity; I see things, I collect them, with no intention or without knowing what to do with them. I just keep them, because they trigger something within myself. A couple of years later, maybe even ten years later, these things appear in my mind again and lead to a new body of work. There’s no straight line or conscious scheme of collecting. It could be any kind of image—it’s just that I’m attracted to it.

MF: Does the medium continue to surprise you?

TR: No, not really. But of course I’m always happy when I see a new, never-before-seen example of a photograph. An image is just an image—it all depends on what you do with it.

April 2, 2013

Interview with Owen Kydd

Owen Kydd is a Los Angeles–based artist who has recently garnered attention for his “durational photographs,” video works that run four to six minutes and explore the interstitial space between still photography and cinema. Curator Charlotte Cotton discussed Kydd’s work in her article “Nine Years, A Million Conceptual Miles,” published in Aperture’s Spring 2013 issue. Here, Kydd speaks with Aperture about his work and its relation to still imagery, experimental cinema, and technology. The interview is one of a series of online-only texts commissioned to accompany the Spring 2013 issue, “Hello, Photography,” which examines the state of the medium in a time of great change. —The Editors

Owen Kydd, Excerpt from Canvas Leaves, Torso, and Lantern, 2011, video on forty-inch display screen

Aperture: How did you arrive at the concept of “durational photographs”?

Owen Kydd: I was thinking about the differences between cinematic moments with photographic qualities and static images with time added and decided that “durational” applied more to the latter. The idea of duration as “incomplete time” seemed to be a way of categorizing a flow of pictures without relying on models drawn from cinematic discourse. It was not a direct challenge to the definition of cinema—my work would likely fall into a strict definition of that category—but a way of proposing the possibility of undoing the time signature of the photograph. Whether a snapshot or a tableau, a photograph denotes the flow of time by its very lack of duration. It reveals the possibility of two types of time, one that is frozen and one that is always mobile. I am trying to reverse the typical effect of the still photograph, to ask people to think about creating stillness out of duration. It’s a performance of photography that I don’t think occurs so readily in the narrative activity of cinema.

AP: Photography’s evolution has always been determined by technology and your work reflects the fact that many cameras can now shoot both stills and video.

OK: That’s exactly it. I started making this work in 2006, when still cameras began to include decent video options. It seems so normal now, but I think when we look back at this development it will be seen not only as a democratization of filmmaking, but also as a considerable marker in the history of still images. In addition to these hybrid cameras, flat screens with resolution that made video look photographic became affordable. Before this people had to rely on projectors, which meant a darkened room, and, even in the gallery space, that’s cinema. It was really in about 2005 or 2006 that technology allowed duration to be a constant variable. I was hoping my project would retroactively define certain conditions of still photographs while actively reversing the absolute time of the photograph.

AP: Can you talk more about what you wanted to explore about “the conditions of still photographs”?

OK: I was looking for a set of “static” conditions that would make something look like it was in the middle of being photographed, even when in motion. That’s a difficult effect to categorize, and I decided that instead of directly trying to reproduce a set of photographic circumstances, I should start by confronting things that I found limiting in photography. I guessed that I might find this in the some of the clichés of the medium; for example, I started with straight or documentary photographs because they were problematic for me as still images. I wanted to know if adding time could allow me to avoid some classic presumptions associated with the documentary form yet still make good pictures. I was asking questions: if the subject of a photograph moves, can I say I’ve captured something decisive? And if not, can I create an image that continues to hold this type of charged moment?

Owen Kydd, Excerpt from Two-Way Polyester Flowers (For L.B.), 2012, video on forty-inch display screen

AP: What was problematic to you about documentary images?

OK: It’s a big category and difficult to define, but I could say that certain photographs which claim to report the real have always had difficulties on some level. But luckily all photographs contain cells that eventually disrupt the certainties that were originally ascribed to them. I wondered if I could accelerate this process by changing the temporal status of the image enough to create a tension, or distance, between subject and viewer that would make us think about documenting in a more fluid form. The snapshot street image seemed like a good place to start because it is understood as the most instantaneous type of photograph.

AP: But many of your works are well-planned still lifes, not snapshots taken on the street. How does duration relate to the still life form?

OK: There were instances I felt like I was creating a camera-based “street” picture without a decisive moment, where I found a version of stillness that expressed an event. But there were other times when I felt duration trapped the subject in a succession of static moments that mimicked a more traditional search for the “essential” and did little to create the tension I was seeking. Ultimately though, I was learning about what made durational photographs work—different things that resisted the need to close the shutter just once. These were found in subtle temporal and atmospheric effects such as the movement of air and light, or materials and surfaces I was using—plastics, inorganic reflective surfaces, objects that had a trompe l’oeil or ambiguous appearance on the video screen. I brought back a collection of these elements to the studio to be assembled and filmed.

The most important thing for me, aside from the instrumental control that a studio offers, is the way it introduces a present tense. The studio erases temporal markers. I wanted to record the present-ness of the studio, possibly to ensure that there was even less chance of interning an event, but perhaps also to confuse the experience of viewing. I have been asked if my studio images are live feeds from another location, which I hope is a clue that something irregular is occurring.

AP: There is a sense of “crime scene” in some of the images—the atmosphere, the sense of oddity …

OK: I am both documenting and remaking storefronts from Los Angeles as a way of performing classic photographic subject matter; storefronts have been a consistent subject for wandering photographers like Atget, Walker Evans, or Lee Friedlander. I found window displays on Pico Boulevard that clearly hadn’t changed in years and that were lit all night, which is mostly when I filmed them, without pedestrians and only the traces of headlights in the glass. It wasn’t quite clear what many of the stores were selling—a florist selling party supplies and trophies, for example, and stores with the word “museum” in their name. Maybe it’s also the imagined history of L.A., but instead of Atget–like scenes, these locations took on a noir effect, meaning they still felt like the crime hadn’t been committed. A key to noir is the separation of subjects from the world around them through the contrast of light and dark, and this contrast helps create sense of distance in the picture, providing a tableaux effect.

Owen Kydd, installation view of Color Shift, 2013, Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, New York. Courtesy of the artist and Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, New York.

AP: In terms of the concentrated looking and observation involved in your durational photographs, I’m wondering about how experimental filmmakers—people such as Michael Snow, Peter Hutton, or Andy Warhol—have been a point of reference for you.

OK: I am in debt to expanded cinema and works like Empire, Wavelength, or James Benning’s films, and the last eight minutes of Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’eclisse, for making moving images appear as if they contain still photographic moments. But with most of those films, the viewer is always located in the same space as the work; there is a projector behind you, and a beam of light that situates you physically within the process of forming the image on the wall in front of you. And I should make the point here that even if you are able to watch these films on an LED screen today, they were initially constructed for projection in a darkened room. I chose flatness as a parameter in my work, and am thus bound to a form of picturing. Fiona Tan’s monitor portraits and David Claerbout’s slide shows, even though they are mostly projected, operate in a similar field. Essentially, I think that if the photographic instant has been aligned with the conditions of modernist pictorial space, then its inverse performance should share similar concerns with surface, distance, and time.

Matthew Pillsbury: City Stages

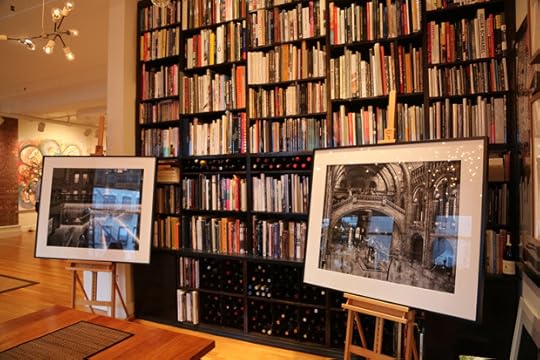

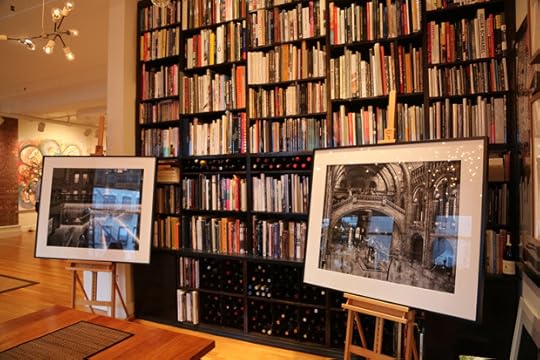

Matthew Pillsbury City Stages prints on display.

Aperture Trustee and host Michael-Hoeh speaking at City Stages cocktail reception.

Photographer Matthew Pillsbury speaking at City Stages cocktail reception.

Kurt Locher, Barney Kulok, Elaine-Goldman, and Lesley A. Martin at City Stages cocktail reception.

Anne Stark, Kathy Ryan and Bill Hunt at City Stages cocktail reception.

Dennis Powers, Michael Hoeh and Andrew Lewin at City Stages cocktail reception.

Photographer Mary Ellen Mark at City Stages cocktail reception.

Gallerists Deborah Davis and Emily Jane Kirwan at City Stages cocktail reception.

Fabiola Alondra, Balarama-Heller at City Stages cocktail reception.

David and Jane Walentas, with Gabby Pasternak at City Stages cocktail reception.

Aperture Magazine Spring 2013 issue on display.

Matthew Pillsbury City Stages prints.

Guests celebrating at the art collection of Michael Hoeh.

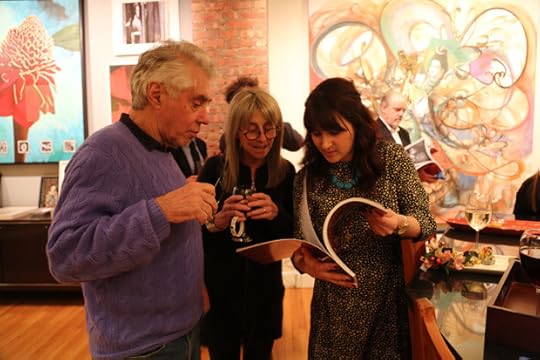

On Tuesday, March 19, nearly fifty photography collectors, gallerists, and Aperture donors gathered at the art collection of Aperture Trustee Michael Hoeh to celebrate the upcoming release of Matthew Pillsbury’s monograph City Stages. The proposed cover image for the publication, High Line, was on display, as was a 30” x 40” limited-edition print Matthew created exclusively for project supporters. If you are interested in supporting Matthew’s monograph, please e-mail development[at]aperture.org or call 212.946.7103.

Bonni Benrubi Gallery will contribute ten percent of all Matthew Pillsbury print sales to Aperture through May 15. When making a purchase at the gallery, please let the staff know that you are supporting the book project.

The New York Times Magazine Photographs

The New York Times Magazine Photographs$75.00

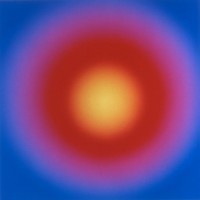

The Edge of Vision Interview Series: Bill Armstrong

In this 2009 interview photographer Bill Armstrong discusses his work Mandala #450 within the context of the Aperture exhibition The Edge of Vision: Abstraction in Contemporary Photography, as well as his Infinity series, for which he photographs printed source material with his camera’s focus ring set to infinity. Going through his work since the 1980s, Armstrong explains why he uses blurring as a process, as well as his “painterly approach to photography.” At the end, he also introduces his newer video work.

This clip is part of an interview series produced on the occasion of The Edge of Vision: Abstraction in Contemporary Photography, curated by Lyle Rexer, which showcased the work of nineteen international contemporary photographers—including Bill Armstrong, Michael Flomen, Manuel Geerinck, Barbara Kasten, Chris McCaw, Penelope Umbrico, and Silvio Wolf—who base their practice in some form of abstraction from highly conceptual to more documentary approaches. The works explore diverse aspects of the photographic experience, including the chemistry of traditional photography, the direct capture of light without a camera, temporal extensions, digital sampling of found images, radical cropping, and various deliberate destabilizations of photographic reference. This abstract use of photography often combines other mediums such as painting, sculpture, drawing or video. All artists join a broad contemporary trend to look critically and freshly at a medium commonly considered transparent.

—

The exhibition was accompanied by The Edge of Vision Limited-Edition Portfolio, as well as the book The Edge of Vision: The Rise of Abstraction in Photography by Lyle Rexer (Aperture, 2009).

Related article: Interview with Bill Armstrong

Related video: Thinking In Color: A Conversation with Bill Armstrong and W.M. Hunt

The Edge of Vision

The Edge of Vision

$49.95

The Edge of Vision Limited-Edition Portfolio

The Edge of Vision Limited-Edition Portfolio

$3,000.00

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers