Aperture's Blog, page 198

May 17, 2013

Observing by Watching: Joachim Schmid and the Art of Exchange

By Geoffrey Batchen

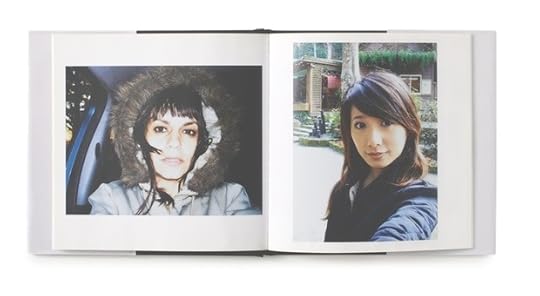

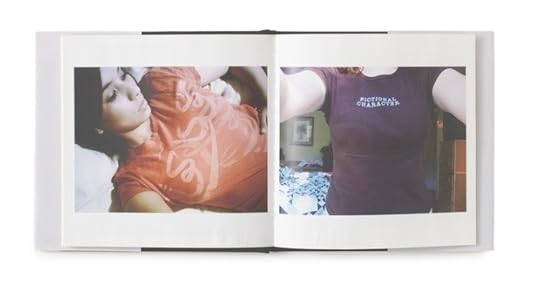

Joachim Schmid, from Other People’s Photographs: Self

It is surely telling that in the same month—January 2012—Eastman Kodak declared bankruptcy and Facebook, the world’s largest online social-network site, moved toward becoming a publicly traded company valued at $100 billion. The following April, Facebook spent one of those billions acquiring Instagram, a startup offering mobile apps that let people add quirky effects to their smartphone snapshots and share them with friends.

The inference could not be clearer: social media has triumphed over mere media, or at least over the photographic medium as we once knew it. But what is the nature of the social in digital image-sharing sites? And what about the nature of photography itself? Has it too become bankrupt, reduced to no more than a vehicle for conveying sentimental platitudes? Or does it continue more or less as it always has, banal or fascinating according to the prejudices or interests of each viewer, avoiding its own obsolescence through yet another one of its strategic technical transformations?

Everyone concedes that photography is now a medium of exchange as much as a mode of documentation. Able to be instantly disseminated around the globe, a digital snapshot initially functions as a message in the present (“Hey, I’m here right now, looking at this”) rather than only as a record of some past moment. This kind of photograph is meant primarily as a means of communication, and the images being sent are almost as ephemeral as speech, so rarely are they printed and made physical. As Michael Kimmelman once put it in the New York Times, photographing has become “the visual equivalent of cellphone chatter.” That chatter demands a different kind of body language than in the past, with arm outstretched and photographer looking at, rather than through, the camera. Contemporary photographers gaze at a little video screen and decide when to still (or not) the moving flow of potential images seen there. In operating that camera, they enact a sort of cultural convergence, in which the distinction between production and reception, and between moving and still images, has clouded. Danish scholar Mette Sandbye has proposed we consider this convergence a “signaletic” one, such that the “that-has-been” temporality of photography once described by Roland Barthes has been replaced with a “what-is-going-on,” a sharing of an immediacy of presence.

That said, the sheer number of photographic images being loaded onto social-media sites makes any analysis of the phenomenon difficult. Facebook has reported that more than three hundred million photographs are uploaded onto its site every day, meaning that the site currently hosts more than 140 billion images. That makes Facebook about forty-six times more photographic than Flickr, the next largest depository. Established in February 2004 by a Vancouver-based company, Flickr reportedly gains about 4,500 new photographs every minute (so nearly 6.5 million a day), mostly gathered into the electronic equivalent of personal photo-albums. Nevertheless, even the White House releases its official photographs there. And it’s just one of a number of such sites (the oldest, South Korea’s Cyworld, has boasted that at one stage 37 percent of the South Korean population had an account). How can anyone examine a representative sample of contemporary photographic practice in the face of such overwhelming statistics?

As it happens, a German artist named Joachim Schmid spends six hours a day perusing and grabbing images from Flickr, using them to illustrate his own artist books under the title Other People’s Photographs. When I asked him why, he told me: “I do it so that you don’t have to.” In the process of saving me the trouble, he also provides a kind of anecdotal, surrealist ethnography of global photography today. Again, it has become a truism to remark on the refashioning of privacy in our digital age, with social media stretching the word “friend” to include a vast array of relative strangers. Schmid’s unauthorized publication of Flickr photographs merely extends this array to comprise discriminating denizens of the art and book-collecting world. His website discusses Other People’s Photographs:

Assembled between 2008 and 2011, this series of ninety-six books explores the themes presented by modern everyday, amateur photographers. Images found on photo sharing sites such as Flickr have been gathered and ordered in a way to form a library of contemporary vernacular photography in the age of digital technology and online photo hosting. Each book is comprised of images that focus on a specific photographic event or idea, the grouping of photographs revealing recurring patterns in modern popular photography. The approach is encyclopedic, and the number of volumes is virtually endless but arbitrarily limited. The selection of themes is neither systematic nor does it follow any established criteria—the project’s structure mirrors the multifaceted, contradictory and chaotic practice of modern photography itself, based exclusively on the motto “You can observe a lot by watching.”

Joachim Schmid, from Other People’s Photographs: Self

For one such book, Schmid first gathered some ten thousand images of “currywurst,” the local fast food of his hometown of Berlin, lovingly photographed by those unlucky souls about to consume it (he tells me that, over his many earlier years spent gathering discarded analog photos, he found only a handful of such images). People visiting Berlin apparently want to remember the food they are about to eat, or at least to share the experience of that want with others. Even within the apparent global homogeneity of Flickr we can thus find viral traces of the local asserting themselves—if, that is, we care to look for them.

In fact, it is only Schmid’s looking that turns this otherwise international genre of food photography into a regional, even an autobiographical, focal point. Indeed, it might be said that a collapsing of the global into the personal is at the heart of his practice, making it true to the character of social media itself. Sitting at his computer screen, he downloads certain subjects and motifs that seem to recur in the constant stream of photographs he sees on Flickr’s “Most Recent Uploads” page, which he refreshes constantly. Of course, there are now sites that set out to facilitate this same sort of distillation process, such as Pinterest, a social-media website launched in 2010, on which its twelve million users compile collections of pictures they find on the Internet. But Schmid brings both a distinctively ironic eye and the play of chance to this process (he finds his images rather than searching for them), thus allowing us to take note of exhibitionist desires that might otherwise remain scattered and lost in the infinity of digital space. In short, each of the thirty-two-page samplers in Other People’s Photographs imposes a thematic unity on an otherwise unruly universe of images. A diverse group, these samplers include the titillating flash of Cleavage, the deadpan documentation of Mugshots, the concrete poetry of Fridge Doors, and the more literally concrete jungle of Parking Lots (surely a choice of category inspired by Ed Ruscha), to name only a few of his titles.

Among other things, Schmid has recognized the sudden popularity of previously unknown genres of image, such as the proliferation on Flickr of photographs of camera boxes, apparently now the first thing everyone takes with their new camera: takes, and then shares online. In a similar vein, one of his recent books comprises nothing but photographs of the photographer’s shadow. Some things, it seems, never change. Or maybe they do: what’s interesting about this digital genre is that all these shadow-pictures seem to have been deliberately made, a significant shift in an amateur practice in which clumsy accident once ruled the pictorial roost. Here on Flickr, through the mediating agency of Schmid’s hunting and gathering, we get to see the art world, which once upon a time mimicked this aspect of the so-called snapshot aesthetic, now having that mimicry copied and reabsorbed back into vernacular practice. It seems the analog snapshot is indeed remembered in digital form, but only via a historic artistic mediator.

Another frequent image appearing on Flickr is the selfportrait made with camera in hand, arm outstretched, a type of photograph made possible only with the advent of lightweight digital cameras. Schmid’s book on this genre implies that there are many more young photographers doing this than those over thirty, and more women than men. His selection also leaves the impression that this practice is more popular in Japan than in other countries (although, as he admits, this could be because Japanese teenagers upload their files onto Flickr as he starts work in Germany, whereas American members upload while he is asleep). In Korea, this kind of photograph has its own name: selca (self-camera). Korean scholar Jung Joon Lee reports that many young women who practice selca adopt specific angles and facial expressions that are designed to give them bigger eyes, a higher nose bridge, and a smaller face. But this kind of specificity, and a critical engagement with the Orientalism it internalizes, is subsumed in Schmid’s book to the startling conformity of the genre, to a blithe repetition of form that appears to obey no identifiable cultural imperative beyond narcissism. Here, then, is the challenge his project lays before us—not just to make sense of contemporary photography, but to find ways to creatively intervene within it; not just to wonder at its numbing sameness, but also to exacerbate into visibility the abrasive political economy of difference.

Geoffrey Batchen teaches the history of photography at Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand.

May 16, 2013

The Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation Photobook Awards 2013

The Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation Photobook Awards are now open for submissions. This year’s call for entries will run through September 13, 2013, with winners to be announced at Paris Photo, November 14–17, 2013, and in The PhotoBook Review issue 005.

This year we’ve launched a brand new online home for the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation Photobook Awards. In the coming months expect an expanded range of slideshows, videos, and editorial content highlighting selections from this year’s submission pool, documenting the behind-the-scenes process of jurying the Photobook Awards, and revisiting 2012′s shortlisted titles and winners.

Submit today, and stay tuned!

May 15, 2013

Interview with Michael Kamber

Baghdad, Iraq, February 12, 2003—Six weeks before the start of the war, a man sits drinking tea at the Al Zahawi cafe on Rashid Street. Cafes are a trademark of this ancient city, gathering places where men play dominos, blackjack, and socialize. Photograph by Bruno Stevens.

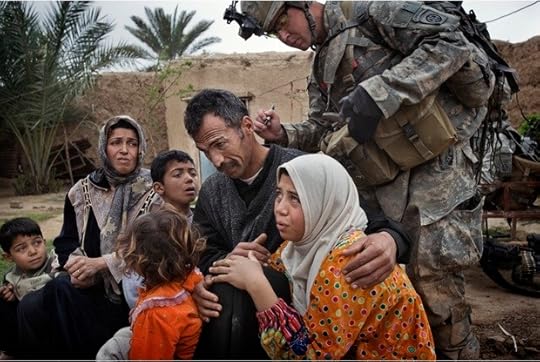

Qubah, Iraq, March 24, 2007—A US soldier marks the hands of women and the backs of the necks of men with numbers for their specific neighborhoods and homes. Lt Col. Andrew Poppas of the 73rd Cavalry, 82nd Airborne Division, said the numbering system allowed troops to determine if people were moving around the village of Qubah despite a lockdown following a US attack on insurgents. Photograph by Yuri Kozyrev/NOOR.

Tal Afar, Iraq, June 7, 2005—Terror suspects are detained and put inside an Armored Personel Carier to be transported to a local detention facility during an early morning raid in Tal Afar. Soldiers of the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment and Iraqi soldiers are moving into Tal Afar with Bradleys, Tanks and Humvees. Helicopters are flying overhead. The soldiers are searching houses and detaining terrorist suspects. Photograph by Christoph Bangert.

Karmah (Garma), Iraq, October 31, 2006—Sgt. Jesse E. Leach drags Lance Cpl. Juan Valdez of Weapons Company, 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines, to safety moments after he was shot by a sniper during a patrol. Valdez was shot through the arm and right torso but survived. Photograph by João Silva/the New York Times.

Photojournalist Michael Kamber, a recipient of the World Press Photo Award, has worked in the field for more than twenty-five years. He covered the war in Iraq as a writer and photographer for the New York Times between 2003 and 2012, and he was the paper’s principle photographer in Baghdad in 2007, the war’s bloodiest year. His new book, Photojournalists on War: The Untold Stories from Iraq, includes illustrated interviews with three dozen of the world’s leading photojournalists about their experiences in Iraq. Brian Sholis spoke with Kamber by phone.

Brian Sholis: In your introduction you write that “censorship became the starting point for this book.” Can you speak about the tightening of restrictions on photojournalists and the political ramifications of these changes?

Michael Kamber: We began to see changes in what photojournalists were allowed to document as early as 2004. During 2003 the journalistic landscape in Iraq was very open, and we could basically link up with a unit on the street, or find a commanding officer with whom to do quick embeds with very little paperwork. Yet as early as 2004 there were more forms to fill out, additional restrictions. When I went back in 2007, the scene had changed a lot. So much was off-limits, and that only increased.

Photographers were going to Iraq to show the reality of war. When you arrive and discovered you couldn’t show wounded American soldiers, or prisoners, or car-bomb scenes, or memorials for Americans who had been killed—at a certain point it just seemed like we were not able to get out to the American people the information we were trying to get out. I should point out, too, that even when we were able to get these types of images, editors back home frequently didn’t want to publish them. There were several explanations for this. Some editors feared that the images would upset American readers, and that people would cancel their subscriptions. Others were concerned that their Pentagon or military reporters would lose access. There was definitely a worry about backlash, and it was founded. I worked in situations with reporters where we did indeed lose access, and even were threatened . . .

Balad, Iraq, November 13, 2004—United States injured soldiers sit on a cargo plane before taking off to Germany from Balad Air Base. The interior lights of the plane are red because of an “alarm red” attack, which indicates that the base is under attack, usually by incoming mortar rounds. Since the attack on Fallujah began in early November, hundreds of soldiers have been injured and evacuated from the country. Photograph by © Lynsey Addario.

BJS: Which only exacerbated difficult conditions on the ground. Dexter Filkins, in his foreword, calls the Iraq experienced by photojournalists during the war a “wraparound battlefield.” Do you think this is now the default “setting,” so to speak, for the war environment? If so, how does this change things for photographers?

MK: Well, I think Iraq was pretty unique. You can see similar conditions in Afghanistan, but nonetheless there are some areas fairly clearly understood as Taliban territory. In Iraq, the battle was all around you. It was largely an urban war, yet there was plenty of fighting in the countryside, too. There was no front line. There were roadside bombs, bombs in the marketplaces, bombs in the trunks of cars. It was all around you, all the itme; you were always susceptible to it.

And photographers were also targets. As westerners, we had a price on our heads. So I think Iraq did mark a turning point. It was Chris Hondros who explained it best to me. In the past, there were different armed combatants, and they needed the press, relied on it to some degree. That gave us some immunity and safety. Now people have their own channels of communication. The insurgents in Iraq, and elsewhere in the Middle East, have their own media, basically. In Iraq, they had their own photo and video operations; they were filming their own attacks. They no longer needed the mainstream press. As Chris said, we were actually a hindrance; we were in their way. I’ve been doing this for twenty-five years, and in Iraq I could tell that the equation had changed.

BJS: In your interview with him, Patrick Chauvel comments on the relationship between photojournalists’ work and amateur photographs from Iraq. Did the environment for photojournalists and their work change after the Abu Ghraib revelations?

MK: The photos from Abu Ghraib did change a lot. Every single person I interviewed in the book, when I asked what are the most important images from Iraq, responded by mentioning the pictures taken by prison guards at Abu Ghraib. That’s remarkable, and there are complex reasons for it. Those photos changed everything in Iraq, especially Iraqis’ perception of us.

Yet there are a few different issues here, involving as well how the media is changing. Joao Silva said that the problem wasn’t that we hadn’t taken a good image in Iraq, but that we had taken too many. Every image is on a homepage for ten minutes and then is refreshed. When I grew up, we sat with magazines for a week. Additionally, a French photographer who has been working for nearly forty years and who is not in the book has noted how, in the past, when you needed a good photo you needed someone who could expose Kodachrome, travel the world, get the image, send the film back. There were not that many people with all the skills necessary. Today, anybody with a cell phone can get a photo that would be deemed useable, that could end up on the front page of newspapers. I wouldn’t say there is no longer a need for photojournalists, but the standards for what is deemed photojournalism have come down very far. Sometimes newspaper editors will print photographs without knowing their source, or without knowing the agenda of the person who took the picture. What’s missing, and what I hope to address with projects like the Bronx Documentary Center, is the ethical training, the training in standards and journalistic values.

Tikrit, Iraq, April 14, 2003—In Saddam’s hometown, a US Marine slides down a marble handrail in one of the dictator’s extravagant palaces. The residence contained carpets worth hundreds of thousands of dollars and at least one golden toilet. Tikrit was the last major city to fall to Allied forces during the invasion and, despite fighting that continued through Iraq, Marines celebrated victory. Photograph by Ashley Gilbertson/VII.

BJS: The book has specific boundaries: in its pages readers will find no military leaders, politicians, academics. There are few if any photos of daily life in Iraq. Can you speak about how you came to shape the book’s countours?

MK: I wanted to put forward a view of the war that I hadn’t seen in the media, that I didn’t feel was out there for the American public to encounter. That was at the bottom of it. I was coming back from a war that I knew well, and I simply wasn’t seeing it here in America. Americans didn’t seem to understand what was really happening. They knew the war was taking place, had vague ideas about it, had seen some TV footage and some statistics, but I felt like a broader understanding was mising.

BJS: How many pictures in the book are previously unpublished, or not widely published?

MK: Some had been published in Europe, but not in the US. Some had been published in smaller domestic outlets, or only months after the incident depicted had taken place, perhaps because editors weren’t comfortable publishing the images at the time. We really dug into people’s files; we did a lot of research. I pushed the photographers to send me the “hard stuff,” including stuff their editors wouldn’t publish. I can’t give you a percentage, but people are unlikely to have seen a fair number of the photographs included in the book.

BJS: You also mention in your note on methodology that you worked with the photographers to recaption some images. Did anything surprising come out of that process?

MK: [laughs] Yes! Certainly for me. Some of the pictures nobody has looked at for ten years, from spring 2003, had captions referring to “the end of the war.” “This picture was taken a week after the end of the war.” I realized quickly that us photographers had no idea of what was coming down the pike. None of us did. I remember taking a taxi to Baghdad and dragging my suitcase up the river until I found the New York Times bureau. I was there to photograph the dawn of a new day in Iraq. We just had no idea what was coming. Reworking the captions brought back how unprepared we were as we went into this military adventure.

BJS: You reproduce an Embed Agreement in the back of the book. What provisions within it might be surprising to the majority of people who have not read it?

MK: There are dozens and dozens of embed agreements. It changed every time I went back. Afghanistan has a different one; different regions in Afghanistan have different embed agreements. I must’ve signed twenty different versions of the document over the years. I’m hoping people will see that we were being made to get written signatures from wounded soldiers to take their pictures, which is completely impossible. After a guy’s been shot and he’s bleeding and being loaded into a helicopter, you can’t run over with a pen and ask him to sign a piece of paper. . . .

And you can’t do it beforehand. You can’t show up and ask a bunch of guys who are suspicious of you in the first place and say, “Hey, guys, in case you get wounded. . . .” The embed agreements put us into unworkable situations in which we’re not free to publish pictures of what is actually going on. Something like 25,000 Americans were wounded over there. We couldn’t get their pictures out to the American public. We don’t want to show blood and gore for gratuitous reasons, but this is our war. We invaded this country, rightly or wrongly. We should see what it looks like.

Al Musayyib, Iraq, May 27, 2003—An Iraqi child jumps over the remains of victims found in a mass grave south of Baghdad. The bodies had been brought to this school for identification by family members who searched for identity cards and other clues among the skeletons to identify missing family members. The victims were killed by Saddam Hussein’s government following a Shi’ite uprising here following the 1991 Gulf War. Photograph by Marco Di Lauro/Getty Images.

BJS: Several photographers comment on how their ranks eventually dwindled to about six. Approximately how many Western photojournalists are there today? Is there a different group of photographers who are reporting, or is it some of the same people you profile in the book?

MK: Well, conditions have changed. You almost can’t take a photo there anymore. It’s nearly a police state at this point. Literally the day the Americans pulled out, that was it. You walked outside with a camera and you were immediately sent home. You couldn’t go into the Green Zone with a camear, you couldn’t photograph in a fish market, you couldn’t leave Baghdad. Franco Pogetti, who has put in year after year in Iraq, said as much, and while I haven’t been there in over a year, I went to a public square one day to photograph a statue and was immediately told, “No pictures.”

I can’t say who’s there now. I don’t know if anybody is there now. I was there the week the Americans left, at the end of 2011. Every news operation in town was closing their bureau. There might be a handful of freelancers. NPR might have a stringer; the wire services might have people there; the Times still has its bureau. But it’s a done story, so far as I can tell.

We did get some work out. The frustration with Iraq was that you had to put in months. I would go for two months and come out with a handful of good photos. I could go to Libya or Afghanistan and come away with the same number in one day. In Iraq, photographers were so locked down, but they hung in there and got good stuff. It was a difficult exercise, but compared to the conditions after the Americans left … well, the Iraqi government has shut things down 100 percent.

May 14, 2013

Interview with Charlotte Cotton (Video)

In this short video, curator and author Charlotte Cotton discusses the value of photobooks and the principles that guided her as she guest-edited Issue 004 of The PhotoBook Review. As she states in her editor’s note in the issue, “My aims for this issue of The PhotoBook Review: to be pluralistic in its approach to the photobook and not merely to propose a checklist for a collectible canon of this essential form of photography.”

—

“Nine Years, A Million Conceptual Miles,” an essay by Charlotte Cotton, is featured in the Spring 2013 issue of Aperture magazine.

Aperture 210$19.95

Aperture 210$19.95

Pablo Ortiz Monasterio on Mexican Portraits

Mexican Portraits, co-published by Aperture and Fundación Televisa, includes more than 350 portraits by over eighty anonymous and well-known photographers, including Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Agustín V. Casasola, Romualdo García, Graciela Iturbide, and Enrique Metinides. In this short video, Mexican Portraits photographer and editor Pablo Ortiz Monasterio discusses the process of selecting and sequencing the photographs to tell a history of Mexico, and reflects on Mexican identity, both individual and collective.

___

Mexican Portraits is now available.

Mexican Portraits

Mexican Portraits$85.00

May 13, 2013

COMPILATION TOKYO: REMIX

On April 6–7, 2013, a screen-printed publication was created during a live event in Tokyo. Self Publish, Be Happy and GOLIGA created a Fluxus-style atelier on the first floor of the venue Harajuku VACANT. For two days, eleven young photographers had a silkscreen workshop facility to create and print their photography as part of a limited-edition publication, COMPILATION TOKYO. Each photographer prepared and silkscreen-printed his or her own work, making the publication an entirely handmade production. During the workshop, all digital production, preparation of printing plates, and silkscreen printing happened in full view of the public.

On April 30, 2013, artist Charlie Engman worked in-situ at Aperture Gallery in New York to create a new artist zine by remixing COMPILATION TOKYO. Engman cut apart, re-photographed, and digitally modified photographs in order to create an entirely new body of work. These new works were printed and photocopied on site to create a new, original limited-edition artist publication. In this video recap of the event, Bruno Ceschel, founder of Self Publish, Be Happy, discusses the project.

—

Compilation Tokyo: Remix is now available.

Compilation Tokyo: Remix

Compilation Tokyo: Remix$25.00

COMPILATION TOKYO: REMIX (Video)

On April 6–7, 2013, a screen-printed publication was created during a live event in Tokyo. Self Publish, Be Happy and GOLIGA created a Fluxus-style atelier on the first floor of the venue Harajuku VACANT. For two days, eleven young photographers had a silkscreen workshop facility to create and print their photography as part of a limited-edition publication, COMPILATION TOKYO. Each photographer prepared and silkscreen-printed his or her own work, making the publication an entirely handmade production. During the workshop, all digital production, preparation of printing plates, and silkscreen printing happened in full view of the public.

On April 30, 2013, artist Charlie Engman worked in-situ at Aperture Gallery in New York to create a new artist zine by remixing COMPILATION TOKYO. Engman cut apart, re-photographed, and digitally modified photographs in order to create an entirely new body of work. These new works were printed and photocopied on site to create a new, original limited-edition artist publication. In this video recap of the event, Bruno Ceschel, founder of Self Publish, Be Happy, discusses the project.

—

Compilation Tokyo: Remix is now available.

Compilation Tokyo: Remix

Compilation Tokyo: Remix$25.00

May 9, 2013

Reflections On the Concrete Mirror

By Barney Kulok

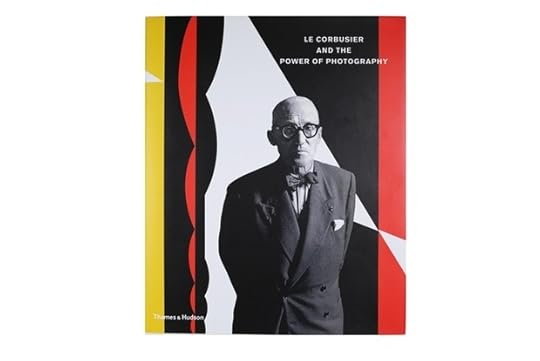

Charlotte Perriand and Fernand Léger, La France Agricole (Agricultural France), 1937. From the book Le Corbusier and the Power of Photography. Courtesy of the Charlotte Perriand Estate.

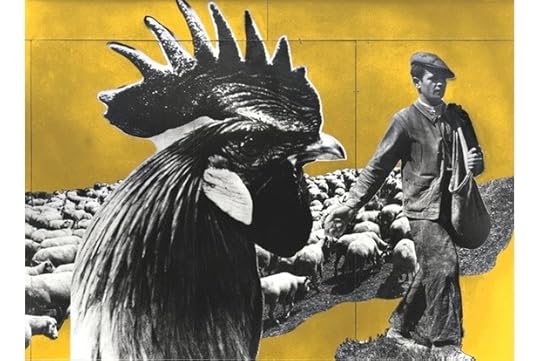

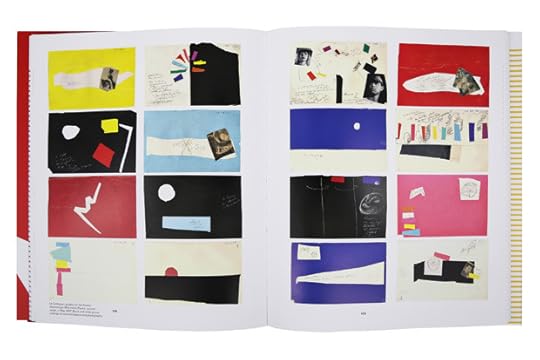

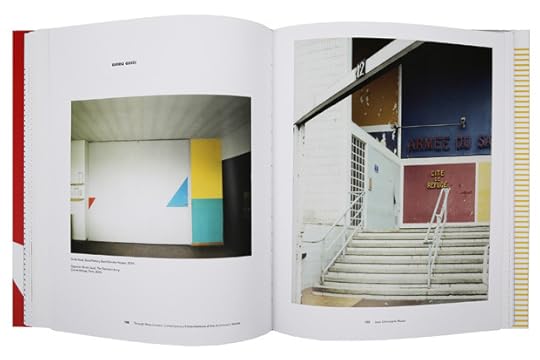

Spread from Le Corbusier and the Power of Photography.

Pavillon Philips, Exposition Universelle, Brussels, 1958, exterior view. From the book Le Corbusier and the Power of Photography. Courtesy of Fondation le Corbusier/2012, ProLitteris, Zurich.

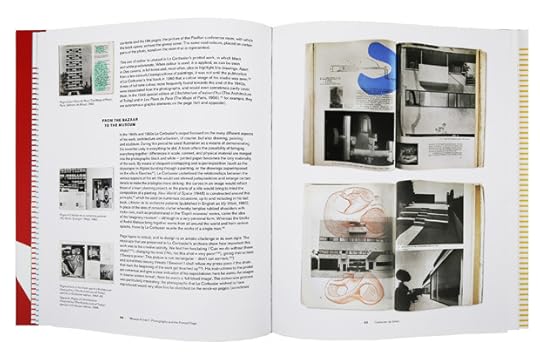

Spread from Le Corbusier and the Power of Photography.

Spread from Le Corbusier and the Power of Photography.

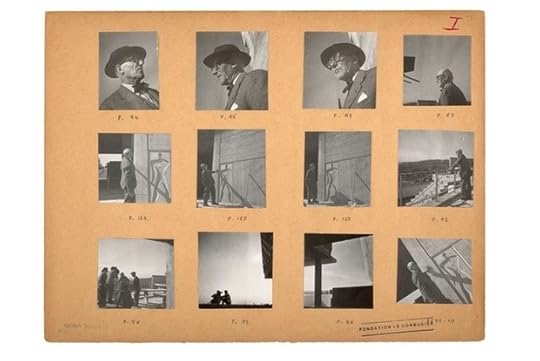

Lucien Hervé, contact sheet of photographs taken during the film of La Cité radieuse (The Radiant City) by Jean Sacha, 1952. From the book Le Corbusier and the Power of Photography. Copyright Lucien Hervé and the Research Library at the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

Resist whatever seems inevitable.

Resist any idea that contains the word algorithm.

Resist the idea that architecture is a building.

Resist the idea that drawing by hand is passé.

Resist the claim that history is concerned with the past.

—Lebbeus Woods, excerpts reordered from Architecture and Resistance

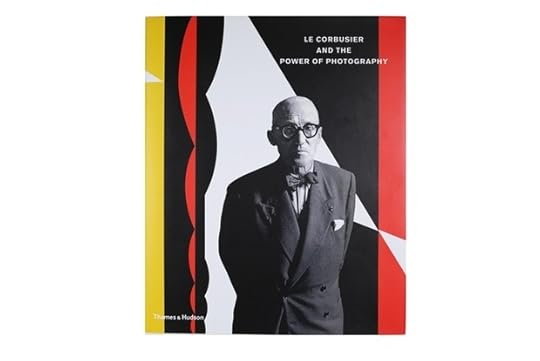

Anyone interested in photographs and buildings, or how the two intersect, might have noticed a recent spate of books devoted to the subject. I count at least two dozen, published in the first three years of this decade, devoted to the work of significant architectural photographers, photographic projects for which architecture is the main subject, collections of architectural photographs, or more focused studies of individual architects’ relationship to photography (in this case Le Corbusier and The Power of Photography, the first of three to come out this year addressing the architect’s relationship to the medium). In addition to the recent books, panel discussions have been organized and exhibitions have been mounted—and several more of each is forthcoming. (Le Corbusier: An Atlas of Modern Landscapes, a major exhibition of the architect’s work in various mediums opens at MoMA in June 2013.) This fact alone is not such a surprise; the question of how to represent architecture in two dimensions has engaged artists for centuries, and photographs of buildings are as old as the medium itself. Photography was born in the lap of architecture: the first chemically fixed photographic view, made from an upstairs room and framed by a window, depicts the slanting roof of a barn on Joseph Nicephore Niepce’s Burgundy estate. The history of photography is so tightly intertwined with architecture and the built environment that one wonders if this recent burst of attention is even worth noting. If it is not simply a coincidence, a question to consider might be, why now?

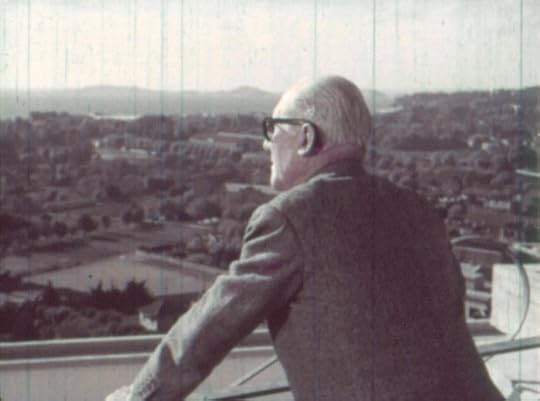

Le Corbusier and the Power of Photography is an excellent example of the recent intensification of interest in this topic. The book includes six essays by a diverse group of scholars and curators, encompassing the many ways the architect engaged with photography throughout his lifetime. The graphic design is bright and energetic; there is plenty of text, but it is primarily a book of images. Tim Benton writes about the young Charles-Edouard Jeanneret’s early experiments with a camera on his travels from 1907 to 1911, and the films and photographs he made when he returned to photography in the 1930s after abandoning his camera for a pencil and paper. Reproduced within this essay are many of the architect’s own photographs and stills he made with a moving film camera. Catherine de Smet lays out Corbusier’s masterful use of photographs in the design of his books and reproduces detailed mockups of many pages from Une Petite Maison (A Little House). Arthur Ruegg describes the photo-based murals Le Corbusier called “photographic frescoes” and the photo collages he designed for traveling exhibitions. Catherine Boone persuasively portrays Le Corbusier as a media-savvy propagandist, pioneering in his oversight of the manner in which his work was portrayed in pictures. He was so strictly controlling of the depiction of theUnité d’Habitation in Marseille that he restricted access to the construction site, forbade the publication of any photographs without his approval, and eventually produced a promotional film about the project for which he specified the film stock, wrote the script, and chose the camera angles, the dialogue, and even the music. In “Through Many Lenses: Contemporary Interpretations of the Architect’s Works,” Jean-Christophe Blasér, a curator at the Musee de l’Elysee in Lausanne, Switzerland, stumbles through an essay about Le Corbusier and contemporary photography, getting some facts wrong and concluding with a convoluted claim that architectural photography has “contaminated” contemporary practice and led to a decline in “humanist” photography. Lastly, Klaus Spechtenhauser catalogs the many candid and staged photographs of the architect himself, looking (seemingly always) stylish and serious, intense and focused on whatever he was drawing, smoking, pointing to, or driving—even holding up a small pig. This final chapter leaves no doubt that Le Corbusier was clearly aware of the presence and power of the camera.

Final scene of Jean Sacha’s film La Cité radieuse (The Radiant City), 1952. From the book Le Corbusier and the Power of Photography. Courtesy Editions René Château.

Architecture is big news and big business. Contemporary architects are major players on the world cultural stage and, following Le Corbusier’s example, most in the public eye have learned to carefully craft their image and exert some control over how their work is represented in the media. In the art world, it seems like every major museum is either adding a new wing, abandoning one space to set up shop somewhere else, or sometimes, tearing one building down to build a new one. This fact alone is not inherently problematic, although there are unfortunately few examples of expansion programs that challenge the prevailing conventions of museum design, which recently seem to prescribe little more than neatly tailored square footage for staging fundraising events; notable exceptions include Steven Holl’s addition to the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City, Missouri, and Peter Zumthor’s proposal for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s (LACMA) future campus. Over the last four years the Whitney Museum, Kimbell Museum, Art Institute of Chicago, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, LACMA, and three Harvard Art Museums have either added new wings or are currently constructing new buildings, all of which were designed by the office of Renzo Piano. The building boom in the museum world is of course just a side note to the construction boom happening all over the world. Cities are built practically overnight in China, and between 2010 and 2013 while all these books were being printed and published, the world record for tallest residential tower was broken three times. In one city. (Dubai.)

In the same three-year period a century ago, buildings in various corners of the world were designed and built by Antoni Gaudí, Adolf Loos, Frank Lloyd Wright, Cass Gilbert, and Walter Gropius, and the original Pennsylvania Station in New York, designed by McKim, Mead, and White, opened to the public. Frank Furness and Nadar died, and Eero Saarinen, Helen Levitt, Robert Capa, and Ray Eames were born. In a factory in Detroit, Henry Ford introduced the first moving assembly line, and while Europe was on the brink of World War I, engineers in Germany built the first prototype of the 35 mm Leica camera. In Paris, Igor Stravinsky premiered The Rite of Spring in the newly built Theatre des Champs-Elysees, an early example of reinforced concrete construction designed by architect Auguste Perret. (Le Corbusier had worked for Perret only a few years earlier.) Big machines for living and small machines for seeing were changing the way we experienced the world; the stage was set for a long affair between photographs and buildings, and Le Corbusier was squarely at the center of it.

Architecture in the modern movement developed in tandem with photography. The two disciplines, while fundamentally different, complimented each other perfectly. Buildings and photographs are both products of the convergence of art and science; even at their most ordinary and utilitarian, they each express the trace of some human ambition. If modern architecture provided photography with a perfect surface on which to project its own self-reflexive questions, photography gave architecture the perfect instrument to promote its image and safeguard its history. The parallel trajectories of photography and architecture in the twentieth century might explain their divergence in the beginning of the twenty-first. The argument can be made that photography was the most powerful force to shape our cultural memory of the twentieth century; indeed one underlying fact that unifies the books I have noted is that almost all of them address architecture of the previous century, even if the actual photographs were made in this one. Perhaps it is simply a matter of distance (even just over a decade) that could explain the recent surge of interest. Or maybe something has fundamentally changed about the way architects engage photography and the way photographers see architecture.

Olivo Barbieri, Interior of the chapel at Notre Dame du Haut, Ronchamp, France. From the book Le Corbusier and the Power of Photography. Courtesy Olivo Barbieri.

The “crisis” of the digital in contemporary photography has a parallel in discussions about recent architecture. Last September the architect Michael Graves wrote an op-ed in the New York Times entitled “Architecture and the Lost Art of Drawing.” He opened the piece with the statement, “It has become fashionable in many architectural circles to declare the death of drawing.” If declaring drawing “dead” is fashionable among architects, in the photography world it has become practically a professional obligation among curators and academics (and some artists) to proclaim and then celebrate or mourn not just the death of film but also the death of photography. Photography, of course, is still very much alive, more so in fact with the proliferation of new technologies and varied platforms; more photographs are made now than at any point in history, and they are being made by a more diverse group of people, in more places, than ever before. Forecasts of the digital revolution dismantling the medium as we know it have proven to be greatly exaggerated. Photography, after all, has always been a technology on the brink of transformation; its history is demarcated by the failed experiments and technological innovations that constitute its evolution. When daguerreotypes were displaced by tintypes and ambrotypes, which later fell out of use in favor of paper prints, there was both a gain and a loss. The same thing can be said for the invention of smaller, faster, hand-held cameras that liberated photographers from the unwieldy, tripod-mounted view cameras to which they had been bound. The transition from film to digital is not so different. It is also a notable fact that as one technology edged out another, the displaced processes remained largely available to any photographer willing to spend a little more time (and, often, money) in the darkroom (see Aperture’s recent publication of Chuck Close’s daguerreotypes, or any of the books on the work of Sally Mann).

Architecture begins on the page and strives to become a thing in the world: each phase of the design process adds a layer of complexity to a project as it moves closer and closer to becoming a real building. Photography begins with the world: a photographer selects a view; the camera simplifies it, transforms it into a digital file or negative; and, after further editing and interpretation, a positive impression of that image reenters the world. Today pictures are less and less likely to ever escape the confines of the screen. While technologies have changed the way both architects and photographers see and study buildings, it is the dematerialization of the photographic print that has most significantly changed the way we consume pictures. In the architecture world several notable figures have voiced concern over the increasing digitalization of design and the corresponding disappearance of drawing in schools and among young architects. Back to Graves, who wrote, “Drawings are not just end products: they are part of the thought process of architectural design. Drawings express the interaction of our minds, eyes, and hands.” Drawing, as part of the making and studying of architecture, has no parallel in photography. When learning how to use a camera, regardless of whether the image is projected onto a digital sensor or a piece of film, there is no better way to learn than by making and looking at lots and lots of photographs. Historically, photographs have been effective tools to illustrate and study architecture; they can describe surfaces and imply volumes, and they can highlight the spatial and geometric complexities of an architect’s design; but most importantly, especially for photographers and students of architecture, they travel well. Photographs of buildings act as stand-ins for the things themselves. As curator Joel Smith points out in another recent book, “A photograph preserves a sectional outtake of the past—the core sample of a moment in Alexandria or two minutes in Spain. When the camera’s subject is an enduring structure, the photograph accomplishes a kind of tunneling-through of space-time.” While pictures will never replace the multi-sensory experience of the body moving through space, photographs can carry the image of buildings through time.

Stéphane Couturier, Secretariat no. 3, from the series Chandigarh Replay, 2006–07. Courtesy Stéphane Couturier. From the book Le Corbusier and the Power of Photography.

The camera became the most powerful and effective mechanism to advance and diffuse the image of modern architecture in the twentieth century, and Le Corbusier was the first architect to recognize and harness the power of photography. Lucien Hervé was the photographer Le Corbusier turned to to provide the most vivid and flattering vision of his work; architects have followed his example and employed photographers to maximize the impact and reach of their buildings. New design tools have offered architects many options for drawing and rendering hypothetical spaces from different vantage points (including impossible ones); like virtual-fly-through animation, the camera view has become just one more tool in the architect’s expanding toolkit. Architects can virtually “photograph” their buildings before they are even built (3-D renderings of apartments are often listed on real estate brokers’ websites in place of photographs). These new technologies have many critics who, understandably, worry about the growing distance between architects and the world. Putting aside the voices of those who naïvely think that architecture can march into the future with no regard for the past, and the symmetrical bias of those who reject all the new digital models and technologies without thought or consideration, most would agree that the new technologies are undoubtedly changing architectural practice. Is it possible that the recent outpouring of interest in the relationship between photography and architecture is a reaction against the increasing digitalization of both? Is this a moment of collective longing for a not so distant past, or is it evidence of a desire to reconsider photography’s ongoing exchange with architecture? Are we looking to create a different kind of relationship between photographs and buildings, in the face of the relentless onslaught of images?

A few blocks from my studio in Long Island City there is a public park that was recently built along the Queens waterfront. Paid for in part by developers to attract residents to a new luxury housing project, the park lies in the shadow of the neighboring towers. There are some nice things about it, but above all I appreciate it as a generous seat from which to view Manhattan. This park is the third point in an important architectural triangle; to the northwest, at the southern tip of Roosevelt Island, is the newly built FDR Four Freedoms Park designed by Louis I. Kahn and directly across the river to the west are the United Nations Secretariat and General Assembly buildings, designed by Le Corbusier, Oscar Neimeyer, and others. The park, unfortunately, does not live up to its geographic potential.Something about it feels off. Maybe it is the uniformity of the undulating backs of the built-in lounge chairs, the height and shape of the brushed-steel lampposts, or the curves of the paths encircling the central lawn. Something about the perforated metal backing of the benches and bulging lines of the Cor-ten steel planters reads as computer-generated and cold, soulless. Even the trees look fake; planted awkwardly along the pixelated tile paths they feel like paper cutouts in an architect’s scale model. Crossing the wide avenue at the edge of Queens and entering the park, it feels as if you have left the city, and indeed the world, behind. The park stretches out before you like a life-size, but lifeless, AutoCAD rendering. At least that is how it looks, and feels, to this photographer. Nonetheless, when walking along the wide boardwalk or sitting and watching the city stand still, it is easy to forget about such things. The sky opens up at just that point along the coast in a way that feels unusual, and expansive, in this city of splintered skies. The view of Manhattan from the park is more vivid and exciting than any I know looking out from the island itself. Key architectural monuments line up across the river like they are posing for a class picture: The Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, the UN Headquarters, and, in the distance, the new World Trade Center. Soon a new public library, designed by Steven Holl, will be built at the edge of the park, and it promises to offer some relief to those of us, in this corner of the city, who have wished for a more thoughtful and exciting space to visit. What architecture gives us, after all, is more than just buildings to look at; it provides the framework for a set of accumulated experiences.

Barney Kulok is a photographer who lives and works in New York. He has presented solo exhibitions at Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery, New York, and Galerie Hussenot, Paris, and is currently included in the group exhibition Traces of Life at Wentrup Gallery, Berlin. His book Building: Louis I. Kahn at Roosevelt Island was published by Aperture in 2012.

Building:

Building:$75.00

May 7, 2013

Scenes from Paris Photo Los Angeles

Photo courtesy Stacey Clarkson

Photo courtesy Stacey Clarkson

The Aperture booth at Paris Photo Los Angeles, on the Paramount Pictures Studios' New York Street Backlot

The Aperture booth at Paris Photo Los Angeles, on the Paramount Pictures Studios' New York Street Backlot

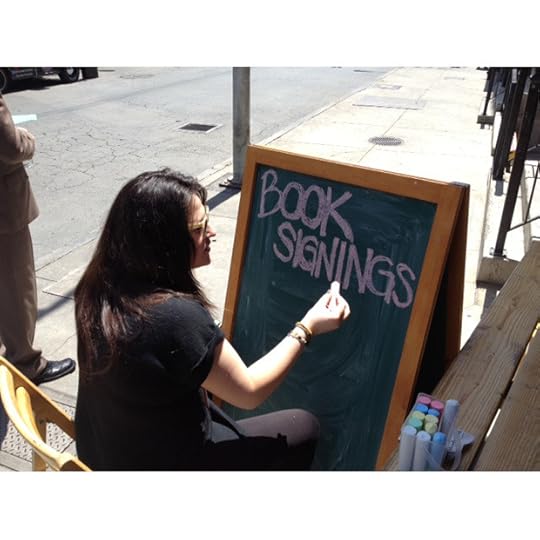

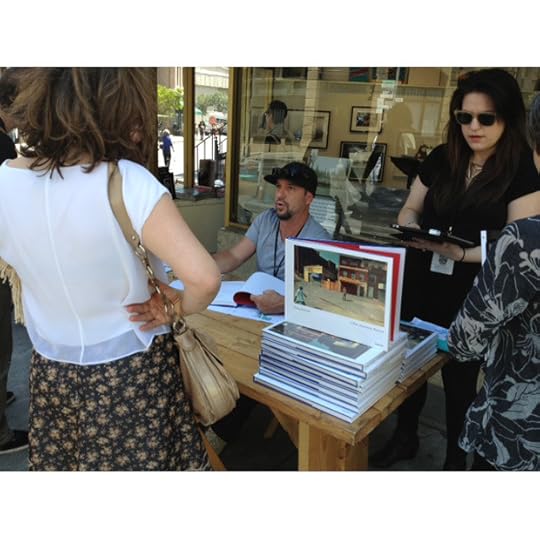

Doug Rickard book signing at Paris Photo Los Angeles

Zoe Crosher studio visit during the Paris Photo Los Angeles Patrons Trip

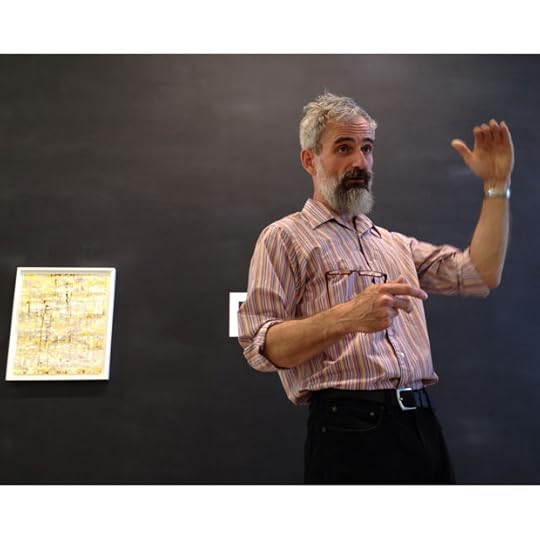

Shaun Caley Regen of Regen Projects during the Paris Photo Los Angeles Patrons Trip

An Aperture patron stands in front of a work by Marilyn Minter at Regen Projects. Photo courtesy Susan Ressler

Photo courtesy Susan Ressler

A behind-the-scenes tour of Regen Projects with gallery owner Shaun Caley Regen

Catherine Opie studio visit during the Paris Photo Los Angeles Patrons Trip

The PhotoBook Review 004 launch party at Paris Photo Los Angeles

The PhotoBook Review 004 launch party at Paris Photo Los Angeles

Paris Photo Los Angeles at Paramount Pictures Studios

Paris Photo made its debut in Los Angeles this spring and Aperture Foundation offered exclusive opportunities for patrons and guests. These included studio and gallery tours with Zoe Crosher, Sam Falls, Phil Chang, Catherine Opie, Marco Breuer, and Shaun Caley Regen of Regen Projects, as well as unique behind-the-scenes tours of the J. Paul Getty Museum and the LACMA Department of Photographs, a celebratory dinner, and a special private-collection visit.

Check out the sights, both on the Paramount Studios lot and throughout Los Angeles!

Announcing the Six Finalists for the 2013 Aperture Portfolio Prize

Akihiko Miyoshi, Abstract Photograph, 2011.

Eva Stenram, Drape VII, 2012.

Bryan Schutmaat, Ralph, 2011.

Clare Carter, Zanele Jonas, New Brighton, Port Elizabeth, 2011.

"Zanele was playing pool in a bar near her home in Port Elizabeth in April 2011. Shortly after stepping outside for a cigarette she was abducted by the uncle of a close friend. He told her, "I am going to show you what it is to be a woman." He had brought with him a pool cue, which he used to repeatedly penetrate her with. Zanele reported the case to the police but they have made no progress in the hunt for her rapist."

[image error]

[image error]

Pacifico Silano, Denim Selection, 2013.

Corey Escoto, House of Cards, 2012.

Aperture is pleased to announce the six finalists for the 2013 Aperture Portfolio Prize. This year, Aperture’s editorial and limited-edition-print staff—twelve members and fourteen work scholars in all—reviewed more than 800 portfolios. Our challenge was to select one top prize and five honorable mentions from this overwhelming response. We are delighted to announce the following finalists, one of whom will be selected as the winner of the 2013 Aperture Portfolio Prize:

Clare Carter

Corey Escoto

Akihiko Miyoshi

Bryan Schutmaat

Pacifico Silano

Eva Stenram

Stay tuned! The winner will be announced in June 2013, at which time all of the finalists’ portfolios and statements will be presented here on Aperture.org. The winning artist will receive a cash prize of $3,000 and an exhibition at Aperture Gallery in fall 2013. The winners of past Aperture Portfolio Prizes can be found on the Portfolio Prize homepage.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers