Aperture's Blog, page 205

January 4, 2013

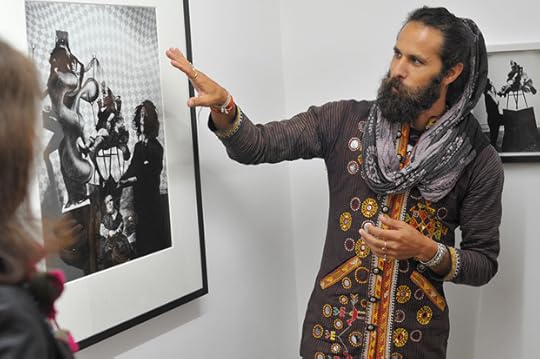

Interview with Okwui Enwezor

By Brian Sholis

This is the last weekend to view the exhibition “Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life” at New York’s International Center of Photography, which closes on January 6. The show, curated by Okwui Enwezor with Rory Bester, examines the manifold legacies of the apartheid system through some five hundred photographs, films, books, magazines, newspapers, and other archival documents. The densely packed exhibit offers insights into many aspects of South African society during the second half of the twentieth century. Aperture spoke with Enwezor about the exhibition, the relationship between the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa and the civil rights movement in the United States, and about how this exhibition aligns with other shows on African themes he has presented at New York institutions.

Greame Williams, Nelson Mandela with Winnie Mandela as he is released from the Victor Vester Prison, 1990. Courtesy the artist. © Greame Williams.

Brian Sholis: The exhibition’s title, Rise and Fall of Apartheid, is fairly self-explanatory, but for people who haven’t seen the exhibition, the subtitle, Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life, might benefit from a little bit of explanation. Can you elaborate on it?

Okwui Enwezor: Apartheid necessarily had to be constructed in order to be woven into the fabric of everyday life. Structures of regulation, structures of invigilation, structures of control, as well as the reformulation of identity, citizenship, the ability of people to circulate through space—the entire geography of apartheid, in a sense, was conceived purely to change what was a legislative document into a normative construct. Bureaucracy was key to these linked developments. The goal was to make sure everyone understood very clearly that if you were white, you lived in a particular neighborhood, while if you were black you lived in another, and if you were colored you lived in yet another. Each provided its own set of amenities: buses, trains, sidewalks, etc. There came to be an understanding across all of South Africa’s social, cultural, and political life that these orders of regulation had become the orders of everyday life.

Photography, in a sense, was a core instrument for making all of these new things normative. It was a way to document, to make visible, that which was about to be disappeared into a kind of normative experience. But let me make one important point that is essential to understanding the relationship between photography and the bureaucracy of everyday life, and to how we understand apartheid: South African photography was invented more or less on the eve of the juridical apartheid state. It accompanies the shift away from the colonial space…

BJS: …the anthropological space…

OE: Yes, away from the anthropological approach of depicting African life.

BJS: While the majority of the photographs in the show depict resistance to this new normative structure, you make a point of including depictions of white society. These are the people who are on top in this society, who enjoy the greatest freedoms. How important was it for you to include such scenes?

OE: We wanted to be careful, so far as was possible, to avoid a narrative of victimhood. I don’t think the exhibition is about victims and oppressors, but is rather about modes of subject formation, modes of production, modes of subjectivity. The deracination of subjectivity was at the very core of the apartheid regime.

It’s also important to remember that resistance to apartheid was a multiracial effort. The people who were most dispossessed in that society would most fear gathering on the barricades, you know, while those who were not victimized by the regime could still be angry with it. The movement to end apartheid reflected the intricacies and complexities of life in South Africa, and our exhibition hopefully reflects them with equal nuance. Apartheid was a society-changing event for both whites and blacks, so in that sense it was very important to be able to present all of its dimensions in the show.

Alf Khumalo, South Africa goes on trial. Police and crowd outside court. The whole world was watching when the three major sabotage trials started in Pretoria, Cape Town and Maritzburg. Outside the palace of Justice during the Rivonia Trial, 1963. Courtesy of Baileys African History Archive. © Baileys African History Archive.

However, the exhibition is not limited to protest pictures. The corrosiveness of the system affected other areas, and is reflected in other photographic genres—in landscapes, for example, and the absences and silences that haunt the spaces captured by photographers’ lenses. Consider David Goldblatt’s images of the destruction of District Six, or Roger Ballen’s pictorial essay on the small towns of South Africa.

BJS: The events that might be most familiar to American viewers—such as the Sharpeville Massacre, the Soweto Uprising, and the end of the system from 1991 to 1994—do not dominate the show in the way they dominate the public consciousness outside of South Africa.

OE: We all know that photography is an instrument crucial to the production of icons, and there are iconic moments that are etched into our collective consciousness. War is one of those moments. But I think that, for example, the Sharpeville massacre also resonated because it occured in the midst of the American civil rights movement. Albert Lutuli, president of the African National Congress, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1960, and he cosigned a letter with Martin Luther King, Jr. that outlined the links between the African-American struggle in the United States and the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa. So it makes sense that we have focused inordinately on those iconic markers.

But I think the epic trajectory of the anti-apartheid movement can be found in the little stories, in small events. Taken cumulatively, everyday acts of resistance, by people now obscure to history, create real change—and it’s these kinds of stories I wanted to encourage viewers to explore. There is the subject of a picture, and then there is the background or periphery; we were extremely curious to learn what kinds of narratives or ideas are embedded in photographs.

One of the things we discerned has to do with the idea of hand gestures. You can tell the story of resistance through the evolution of hand gestures. In the 1950s, the thumbs-up was a way of expressing solidarity. It was a moment in which people still believed in the power of nonviolence, in negotiation. And then Sharpeville happens in 1960, and this gesture of solidarity turns into one of defiance: the clenched fist. The more oppressive the apartheid regime became, the more defiant the resistance became. The clenched first becomes the raised weapons of self-defense. And then, of course, in 1994 everything transitions once again and we see the “V” for victory, the peace sign. These kinds of micro-narratives are lodged within the photographs. Another has to do with funerals: you can see in the settings of funeral photographs the ways that these ceremonies were deployed as ideological communication, both to the community of South Africans and to the world at large.

Jurgen Schadeberg, The 29 ANC Women’s League women are being arrested by the police for demonstrating against the permit laws, which prohibited them from entering townships without a permit, 26th August 1952. Courtesy the artist.

Peter Magubane, Sharpeville Funeral: More than 5,000 people were at the graveyard, May 1960. Courtesy Baileys African History Archive.

BJS: I would like to return to the relationship of the anti-apartheid movement and the civil rights movement. Scholars like Maurice Berger have been reassessing the visual culture of the civil rights movement in recent years. Given that this show is being presented in America, what other lessons, if any, might be found in this exhibition that can help us understand the visual culture of the civil rights movement?

OE: Well, first of all, I think the civil rights movement should be seen alongside and as part of African de-colonization movements. Together they comprise the key development of the middle of the twentieth century. This goes back to issues of subjectivity, as these movements represent both a belief in the modern category of the self and tensions between subjecthood and citizenship. It is these tensions, between subject and citizen, which most strongly link the two movements. There were, of course, great differences. In America the civil rights movement was linked to the church, whereas in South Africa anti-apartheid was almost entirely secular—and was even linked to the Communist party, something that would have been unimaginable in the United States.

BJS: That was certainly not possible in the mid-1950s to the late ’60s.

OE: So perhaps the anti-apartheid movement was a little bit more revolutionary, in terms of its political spirit and its identification with proletariat identities. But visually, in terms of iconographic depiction, the two movements are uncannily similar—right down to the way people dress. The pressed suit, the need to project an image of respectability . . . . I always wonder who was the creative director of the protests organized by the Black Sash Women. They must have had one, and a copywriter for all of their protest signs, and a choreographer for their movements, and a stylist—it’s such a complete performance. Think, too, of the American notion of linking arms, singing protest songs and spirituals…

BJS: It’s counterintuitive to think that a mass movement would be so image-conscious, but on both sides of the Atlantic, protesters seemed to know that visual media could be an assistive technology.

OE: And on the other hand, the apartheid state’s media consciousness was very crude; the political regime was unable to manage the deployment of propaganda extolling its virtues. Hendrik Verwoerd, prime minister from 1958 to 1966, said that the very term apartheid had been misunderstood, and emphasized that in Afrikaans, his language, it means “good neighborliness.” [Laughs.] The powers-that-be could not compete with the anti-apartheid movement in terms of its image consciousness and media savvy. The charismatic, smiling Mandela became an icon of an entire generation in part because he was a good salesperson, better than the dour, unsmiling, unattractive politicians in power. He had star quality, even in his rough moments.

Greame Williams, Right-wing groups gather in Pretoria’s Church Square to voice their anger at the F. W. de Klerk government’s attempts to transform the country, 1990. Courtesy the artist.

© Greame Williams.

BJS: I have a final question about the exhibition itself and how it fits into your chronology and your experience as a curator. Many of us in New York remember Snap Judgments (2006) and Archive Fever (2008), both presented at the International Center of Photography. Some who have been in the city longer will remember The Short Century, presented at MoMA/PS1 back in 2002. Will you situate Rise and Fall of Apartheid in the context of these earlier projects?

OE: Well, this isn’t meant to be the third of a trilogy at ICP, but rather the second. The archive show was a kind of anomaly.

Snap Judgments was very much about the new century, and the ways in which contemporary photographers and artists were trying both to think through the idea of Africa with their images, and to counteract Western constructions of the continent and its people. Rise and Fall of Apartheid is the second show, looking at the twentieth century. The original idea was not to limit it to a case study, but to make it Africa-wide. The final piece of the trilogy was supposed to engage with the nineteenth century; it was to be titled Sun In Their Eyes: Photography and the Invention of Africa. What I was interested in, or what I am interested in, since the show—or a book, or something—is still to be made, is examining the first hundred years of photography in Africa. The project will examine different types of photographic depiction, from Walker Evans to Paul Strand in Ghana to Désiré Charnay in Madagascar to Augustus Washington, the African-American photographer who worked in Monrovia, Liberia, during the 1850s.

Let me end by saying that The Short Century was the genesis of many of these shows. I am still walking down the path I started with that exhibition. There are many things I wanted to do in that show that couldn’t happen, and I am still engaged with them intellectually.

–

Brian Sholis is a member of the editorial staff of Aperture Foundation. He writes frequently on photography, landscapes, and American history.

January 2, 2013

Five Most Popular Interviews of 2012

Aperture’s five most popular conversations and interviews of 2012:

Richard Misrach and Kate Orff Discuss Petrochemical America

Melissa Harris talks with Richard Misrach and Kate Orff about the process of depicting and unpacking the complex ecologies of Louisiana’s industrial corridor for their latest project, Petrochemical America.

Alec Soth: On Influence, Summer Nights, and Allen Ginsberg

When asked to participate in Aperture Remix, Alec Soth chose to pay artistic homage to Robert Adams‘s Summer Nights. Soth spoke with Aperture Remix curator Lesley A. Martin about Adams, Summer Nights, and the influence of other artists on his work.

Anders Petersen: Finding a Fever

From Aperture 198, Anders Petersen and JH Engström discuss the work that would become Petersen’s City Diary, which was awarded PhotoBook of the Year in this year’s PhotoBook Awards.

David Galjaard: On Concresco

Dutch photographer David Galjaard won the First PhotoBook Award this year for Concresco. Thomas Bollier spoke with Galjaard about photographing in Albania, the design process, and self-publishing his first book.

Daido Moriyama: The Shock From Outside

From Aperture 203, Daido Moriyama speaks with Ivan Vartanian about vision and motivation, context and information, color and black and white, and the unending newness of photographs.

December 21, 2012

Aperture Patrons’ Weekend – Slideshow

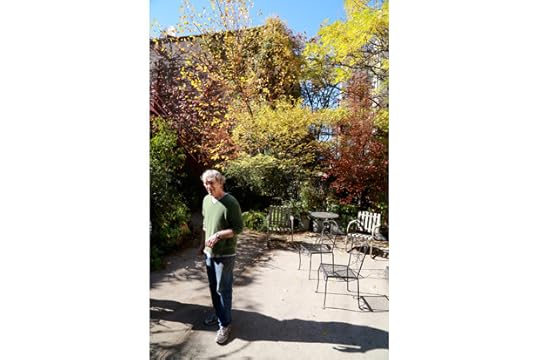

Guests at William Wegman's studio.

William Wegman

Barbara Goodbody, Minny Lee, Elizabeth Levine, Charles Gilman, and Aperture Chief Financial Officer Mary Colman St. John at William Wegman's studio.

William Wegman's studio

One of William Wegman's Weimaraners.

William Wegman

Kasper and Celso Gonzalez-Falla

David Levinthal's studio

Denise Wolff and Nina Cheney

Sondra Gilman and David Levy

David Levinthal's studio

Photographer Matthew Pillsbury and publisher of the Aperture book program Lesley A. Martin

Graphic designer Yolanda Cuomo's studio

Patrons at the Aperture Gallery

Chris Boot and Aperture patrons at Elliott Erwitt's studio

Elliott Erwitt's studio

Guests at the Patron Ticket and Table levels at Aperture Foundation’s Sixtieth Anniversary Gala Dinner & Photography Auction were invited to attend specially arranged visits to the studios of major New York–based photographers, including Elliott Erwitt, David Levinthal, Mary Ellen Mark, Matthew Pillsbury, and William Wegman, and a cocktail reception at the home of Aperture trustee Willard Taylor and his wife Virginia Davies.

Check out a slideshow of photos from the weekend’s visits.

December 19, 2012

Zoe Crosher: Stage Manager

By Carmen Winant

The Los Angeles–based photographer Zoe Crosher has had quite a big year. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art featured her work in a show called Figure and Form after purchasing it for the museum collection; she had her first solo show at Perry Rubenstein Gallery in Los Angeles; and she is included in New Photography 2012 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

In each of the exhibitions, Crosher has worked with, intervened in, and re-presented the self-portraits of one woman, Michelle duBois. It’s an archive comprised of over one thousand images of the same woman over the course of her life. In appropriating it, Crosher has tapped into the most American kind of fantasy, at once tragic and aspirational, fictional and sincere, and, above all, reliant on its own photographic documentation. Aperture’s relationship with Crosher predates these exhibitions; in 2011 and 2012, she worked with the organization to complete a four-volume, print-on-demand, limited-edition artist’s book using the duBois archive. I spoke with Crosher in late October.

Mae Wested no.3 (Crumpled) from the series 21 Ways to Mae Wested, 2012

Carmen Winant: This has been a very busy year for you, participating in exhibitions at LACMA and MoMA and presenting a solo show at Perry Rubenstein. Also, last year you won the Art Here and Now award, and the California Community Foundation Fellowship for Visual Arts. My first question to you is a practical one. How do you manage your time?

Zoe Crosher: Well, it helps to know that it is a finite period. One of the great things about being able to work with a fantastic gallery is the infrastructure. I have an incredible team, and a lot of my job at this point has become efficient delegation. I have a main assistant, plus the archivist and registrar at the gallery, along with three separate production teams. I had wanted to work this way for a while—I knew I would have to in order to realize specific, long-standing ideas—but didn’t quite have the support. Perry [Rubenstein] gave me the opportunity to work within a much larger production model, and that has been essential.

CW: How does being a manager suit you?

ZC: It’s one thing I like about being an artist; you can wear a lot of different hats at different moments. Of course, I am totally obsessed with every detail, the quality of every part of the production.

CW: And you are quite pregnant. I can only imagine that adds to the workload.

ZC: Right, I am going to retreat for a few months when the baby is born. I will start working on a new body of work after that break, so in some ways the timing has been ideal. But when it first happened, I looked at my calendar and thought, How the hell am I going to do this? I had pretty difficult morning sickness, so my functional hours diminished during the day.

To tell you the truth, I didn’t inform anyone for a very long time that I was pregnant because of the professional stigma. People can be very dismissive. I also didn’t think it that it was anybody’s business. When I was at the Dallas Contemporary, the work got a write up in Artforum’s “Scene & Herd” section, which was great. But I was described as a “pregnant Los Angeles artist.” I was shocked!

duBois’ Triple Vision Fantasy Landscapes (Sunset)

CW: You worked with the duBois archive for the above-mentioned shows in Los Angeles and New York this year. How much overlap—conceptually or materially—was there between the three? Was that something that you were trying to indulge or resist?

ZC: The duBois project is all about curation, and that shifts intentionally from show to show. The Aperture books really represent this quality of continually re-telling, of the re-writing of the fantasy archive, so maybe we could start there. The first book is titled The Reconsidered Archive of Michelle duBois, and it is full of what I call “Auto-portraits”—images that she planned, executed, and kept—along with all of her “companions.” The second book is about the physicality of the archive, looking at the backs of the photographs, the antiquated language of Kodak film and the front of the albums. The third book is The Unveiling of Michelle duBois. It concentrates largely on her collection Japanese objects, like kimonos, umbrellas, and dolls. She had over one hundred and fifty Japanese dolls! She also travelled to Asia and made a lot of tourist photographs, “collecting,” on some macro-level, the sites as she went. The fourth book, The Disappearance of Michelle duBois, concentrates on the physical disintegration of the archive, the final manipulation of the images into objects. A lot of works from that final grouping are in the MoMA show, and they play with a certain denial of visibility—images of duBois with her head turned away. Beyond that, I crumple and re-photograph the image with a flash, further imposing a sense of distance upon the images. The metaphor stands as an escape from a singular, conclusive, totalizing effort.

The whole project is about the relationship of fiction and the archive, and the impossibility of knowing oneself even after the accumulation of thousands of images. Simultaneously, the arc is about the end—and breaking down—of analog photo technologies.

No.9 from The Additive Dust Series (GUAM 1979) from The Disappearance of Michelle duBois

CW: Can you talk a little bit about these “wall” installations you’ve been creating? The work, which is hung in strategic clusters, often reads as one collective body.

ZC: I’ve worked this way in both the LACMA and MoMA shows, and in both cases it’s been very specific to the institutional wall. Those I’ll call the Disbanding of Michelle duBois. Both of the projects were focused mostly on The Disappearance of Michelle duBois. I was interested in her gaze darting back and forth, as well as the physical inability to see her. So, I come up with various versions, and then create them site-specifically for institutions.

LACMA bought the piece after I won the Art Here and Now award in 2011, and I didn’t ever imagine that they would show the whole thing. I wanted to make a flexible exhibit, so that one could mix and match it based on the surrounding works. The wall was really specific to the space, and the decisions made about the way that the work was hung happened during the installation, through conversations with the curators. Wolfgang Tillmans is in that LACMA show as well, on an opposite wall, and it occurred to me that we have an opposite approach in that regard. His work was choreographed—down to the millimeter—in its display. Conceptually, my overarching structure is consistent, but how it manifests is completely relative. It’s almost site-specific in that sense. I’m not married to a specific vision.

Tilt of her Head, Over Analog Time (from the series The Disbanding of Michelle Dubois), 2001–11

CW: It’s interesting how these shows relate specifically to the books. Almost as if the books were roadmaps.

ZC: The books are a critical component. They act as guides for both the viewer and for me. The intention of the whole project, books and installations included, is to interrupt our expectations of looking. At first she looks like a sexy blonde lady; once people look a little longer, that idea becomes stilted. In contrast to being about the story that surrounds the work (she was a friend of my aunt, she was a prostitute, anything else), the duBois project is about all of the elements that make up the gestalt. It resists narrative.

CW: Do people think it’s you?

ZC: All the time. I see it a lot on blogs. This is not a biopic! Even though it is from the archive of a real person, this is about fantasy. Both her fantasies and the fantasy of photography itself.

The Other Disappeared Nurse no.7 from The Vanishing of Michelle duBois, 2012

–

Carmen Winant is an artist and writer currently based in Brooklyn. She is a regular contributor to Frieze magazine, Artforum.com, X-TRA Journal, and The Believer magazine, and is a co-editor of the online arts journal The Highlights.

–

All images courtesy of the artist and Perry Rubenstein Gallery, Los Angeles. © Zoe Crosher

Mae Wested no.3 (Crumpled) from the series 21 Ways to Mae Wested, 2012

Digital C-Print

36 x 36 inches

Edition of 6 + 2 AP

duBois’ Triple Vision Fantasy Landscapes (Sunset)

2012 Digital C-Print

84 7/8 x 41 7/8 inches

Edition of 6 + 2 AP

No.9 from The Additive Dust Series (GUAM 1979) from The Disappearance of Michelle duBois

2012 Archival pigment print

13 x 19 inches

Edition of 6 + 2 AP

Tilt of her Head, Over Analog Time (from the series the Disbanding of Michelle Dubois), 2001-2011, by Zoe Crosher

(Nine) Photography and Mixed Media

Modern and Contemporary Art Council, 2011 Art Here and Now Purchase

© Zoe Crosher/ZC International 2012

Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

The Other Disappeared Nurse no.7 from The Vanishing of Michelle duBois, 2012

Pigmented Ink on Museo Silver Rag

29 7/8 x 23 3/8 inches

Edition of 6 + 2 AP

December 13, 2012

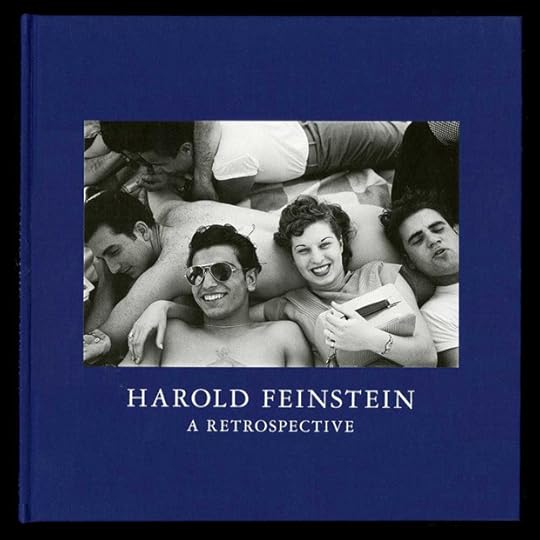

Harold Feinstein Book Party and Benefit

Join Harold Feinstein for a book party and celebration at Aperture Gallery and bookstore on Monday, December 17, 2012 from 6-9PM.

Harold will share memories from a lifetime of photography with gathered friends, fans, former students and colleagues, including historian and photo critic A.D. Coleman. Following the informal conversation there will be a party during which Feinstein will sign copies of his new book, Harold Feinstein: A Retrospective, which was just selected for the Photo-Eye Magazine’s list of best photography books in 2012.

Also at this event signed limited edition archival inkjet photographic posters of Feinstein’s iconic Coney Island images will be on display and for sale at a special one night only price. Additional unlimited edition offset printed posters will also be available. All proceeds will go towards the Hurricane Sandy relief efforts of North Star Fund and #ConeyRecovers.

Visit the website for more information on the Harold Feinstein Book Party and Benefit Sale. The event is free and open to the general public. Please RSVP by email.

December 12, 2012

Daido Moriyama: The Shock From Outside

Japanese master-photographer Daido Moriyama has been at the forefront of the medium for more than fifty years. He has published dozens of volumes of photographs, including Japanese Theatre (1968), Farewell, Photography (1972), Daidohysteric (1993), and Hokkaido (2008), as well as numerous collections of essays. On the occasion of his upcoming retrospective at Osaka’s National Museum of Art, Ivan Vartanian spoke with the photographer about vision and motivation, context and information, color and black and white, and the unending newness of photographs.

IVAN VARTANIAN: Could you speak about your thoughts on the connection between image and language?

DAIDO MORIYAMA: Language is a direct medium and communicates meaning and intention straight. A photograph, on the other hand, is subject to the viewer’s memory, aesthetics, and feelings—all of which affect how the photograph is seen. It isn’t conclusive the way language is. But that’s what makes photography interesting. There’s no point in taking photographs that use language in an expository way. Taking photographs for the purpose of language is for the most part meaningless for me. Rather, photography provokes language. It recasts language; within it, various gradations outline a new language. It provokes the world of language: looking at images leads to the discovery of a new language. That is what I am about. Certainly, photographers—in particular photographers like me, who take street snaps—don’t shuttle back to words with each shot. The outside world is suffused with language. I don’t carry language and apply it to the outside world; instead, messages come in from the outside. That is what provokes me and what I react to. That is the nature of the connection, I think.

That said, I cannot explain every image that I have taken. If I tried to, it would be a sham and boring; it would come across as trivial. That’s not the intention. Each photograph is felt, but there isn’t just one reason for releasing the shutter—there are several reasons, even with a single exposure. The act of photographing is a physiological and concrete response but there is definitely some awareness present. When I take snapshots, I am always guided by feeling, so even in that moment when I’m taking a photograph it is impossible to explain the reason for the exposure. Something might, for example, seem erotic to me. That in itself is a gradation that contains a multiplicity of elements.

IV: In your early magazine work, your photographs are often accompanied by texts you’ve written in an “editorial voice” of sorts.

DM: When I was young, I used to write accompanying texts for my images. Those writings had something of a didactic relationship with the images. In the end, the language with which the viewer sees the photograph changes the image’s content. Even if I chose a word or language with which to take an image, it would be impossible to have everyone feel the same way. Perhaps by chance, a viewer may have a similar feeling.

In working with my older photographs, I treat them as if they are something new—if I didn’t, presenting older work would be pointless. What I photographed at a certain point may have been vivid at the time, but with the passage of years, its luster weathers with it. All work is subject to format, ways of looking, editorial style—all of which influence and alter the work.

That process of alteration is one of the things I love about photography. In essence, through the process of recomposing the work, the photograph is revitalized as something that is contemporary—now. This can be done countless times with any image. In a way, this is like saying that within each image, there is a multitude of possibilities. A single photograph contains different images.

I happen to have produced many books of photographs. I work with others on them—people I trust to a certain extent—and I leave it to them to do the recomposition (as, for example, with Shashin yo, Sayonara [Farewell, Photography; 1972]). The work becomes more vivid than when I do it myself. If I do it myself, I cannot avoid being influenced by memory; I strain to stave off that impulse and inadvertently create a palpable tension—and the outcome is often odd! Whereas when I work with a third party—or even someone more removed—filtering the images through their eyes, the photographs come alive, I think. Photographs that I’ve taken ten years ago even now seem vivid. If an image is good, it is brought back to life by the feelings of the viewer.

IV: What about the function of the photograph as information? Your work, especially from the 1970s, had so much to do with destabilizing this aspect of photography.

DM: Photographs of any generation are in a basic sense, at that moment, information. Photography is underpinned by information. No matter how conceptual a photograph may be, it contains information at its most fundamental level. But the means by which information is communicated is specific to each generation. A recently shot photograph is just as viable to me as one shot ten years ago.

IV: Do you make a distinction between the different media in which your work appears—magazines and books, exhibitions?

DM: I don’t generally make a distinction between them. A magazine has a particular objective, namely it is about the now. In that sense, it uses the information aspects of photographs. And depending on the editorial direction, the photographs may radically change. So if the editorial direction of a particular magazine doesn’t sit well with me, I don’t allow my photographs to be used in it. But in principle, whether a photograph is framed and mounted as part of an exhibition or shown in a photo-book or magazine—these are just different modalities of the same image. Each is interesting in its way. For that reason, I don’t place a lower ranking on magazines. At times, in fact, the magazine reproduction has been the best format for an image, trumping other forms. Again, what interests me is seeing my photographs in a manner that makes them seem different. And in the magazine context, if the photograph doesn’t come alive, it doesn’t necessarily mean there was something wrong with the editorial direction; it probably means the photographs aren’t that strong. There are two sides of a coin.

All images Untitled, 2010, © Daido Moriyama

December 7, 2012

Documenting Tragedy – on NPR.org

Following the New York Post‘s controversial Tuesday cover photograph, a discussion on NPR’s Talk of the Nation considered the ethics of documenting tragedy. In addition to Stephen Mayes, managing director at VII Photo Agency, and Kelly McBride, senior faculty in ethics, reporting, and writing at the Poynter Institute, a number of photojournalists called in to talk about their own experiences documenting difficult situations. Definitely worth a listen, at NPR.org.

Stephen Mayes and others joined Aperture for a panel discussion on the ethics of conflict photojournalism back in September. More on that here.

December 5, 2012

Paris Photo In Pictures Vol. 2: The Patrons’ Eye

Fotomuseum Winterthur with curator Thomas Seelig. Photo courtesy Christian Gapp.

Photo courtesy Anne Stark.

Photo courtesy Celso Gonzalez-Falla.

Stéphane Couturier studio visit. Photo courtesy Christian Gapp.

Stéphane Couturier with Aperture Trustee Anne Stark. Photo courtesy Christian Gapp.

Photo courtesy Celso Gonzalez-Falla.

Annette Friedland, Trustee. Photo courtesy Celso Gonzalez-Falla.

Corinne Planche, Aperture Patron. Photo courtesy Anne Stark.

Corinne Planche, Anne Stark, and Jessica Nagle. Photo courtesy Anne Stark.

Lise Sarfati studio visit. Photo courtesy Christian Gapp.

Lise Sarfati studio visit. Photo courtesy Christian Gapp.

Philippe Halsman exhibition at Magnum Gallery, with Irene Halsman. Photo courtesy Christian Gapp.

Oliver Halsman Rosenberg with work of his grandfather Philippe Halsman. Photo courtesy Christian Gapp.

David Yu and Robert Delpire at Magnum Gallery. Photo courtesy Christian Gapp.

Sarah Moon and Trustee Jessica Nagle at Magnum Gallery reception. Photo courtesy Christian Gapp.

Chairman Celso Gonzales-Falla and Patrons at Le Meurice. Photo courtesy Christian Gapp.

Kellie McLaughlin, dinner at Le Meurice. Photo courtesy Christian Gapp.

Chris Boot and Elliott Erwitt, dinner at Le Meurice. Photo courtesy Christian Gapp.

Dinner at Le Meurice. Photo courtesy Christian Gapp.

A photo diary chronicling the Paris Photo Patron Trip 2012.

Patrons and Trustees joined Aperture in Paris for VIP Access to Paris Photo and all VIP activities organized by the fair, announcement of the first Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards, and guided tours of special exhibitions at Paris Photo.

December 4, 2012

David Galjaard: On Concresco

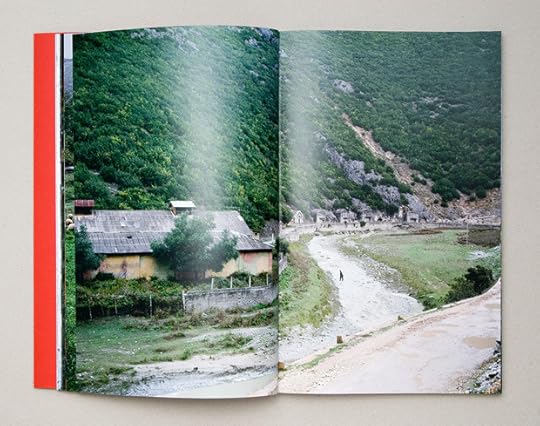

In 2009, David Galjaard began photographing the landscape of Albania, which is dotted with over 700,000 abandoned concrete bunkers built during the Communist dictatorship of Enver Hoxha. Galjaard’s work in Albania culminated in a self-published photobook, Concresco, which won the First PhotoBook Award in this year’s Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards. Thomas Bollier spoke with the Dutch photographer about his work.

Thomas Bollier: Can you tell me a little about your history as a photographer, when you got started, how you got started, and what’s brought you to here?

David Galjaard: To go way back, it feels like I got started as a photographer when I was 15. My father gave me a copy of the book Amsterdam by Ed van der Elsken, and as soon as I saw that book I knew I wanted to be a photographer and that never changed. I studied at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague, and while I was there I mainly worked the way van der Elsken did – with small film, really close to my subject, producing sort of emotional, social documentaries. As soon as I finished school, though, I found that that approach didn’t work for me anymore. I still love looking at those pictures but I wanted to do something else.

Around this time I got my own page in a national newspaper, called NRC Next, which had just started and hadn’t yet developed their visual vocabulary. They asked me if I wanted to work for them as a freelance photographer, and that’s where I feel my work as a photographer really began. We had an agreement that I would do a piece, and if they didn’t like it they would just tell me. But they never did. I could experiment while working, which was a big luxury. After three years at the paper, though, I felt the urge to work on a longer documentary project.

Around this time I also became interested in representing physical space in my photographs, exploring what environments without people can express. I had made a small series, When the siren goes, where I wanted to see if I could capture, in photographs, what I felt when I entered a space myself. I had explored Cold War bunkers in The Netherlands, in which I always felt a sort of ominous, uncanny feeling. I was wondering if it was possible to somehow capture that feeling…to take a photograph and show it to other people, and have them experience that place the same way. It was just a small experiment, but coming from the social documentary I was doing on the street, it was completely new to me.

One of the journalists from the newspaper saw my pictures from this series, and he asked me if I’d heard of the bunkers in Albania. I had traveled a lot through Eastern Europe, but never to Albania, and knew nothing of the history of the country. So I started reading about it, and bells started ringing when I read about the 750,000-1 million aboveground bunkers that were built in such a small country. I then traveled to Albania, just to look around. My first plan was to research how those bunkers have influenced the landscape and to see how, to the people who were still living there, those bunkers were still a reminder of a dictatorship that had lasted for almost fifty years. I traveled around Albania for a month, and took some good pictures, but it wasn’t much more than a small series, like something that would work in a magazine. I wanted to do more, but didn’t know what exactly. I kept reading and thinking about it, and after a couple of months realized that I wasn’t going to figure out what I wanted to do in Holland, so in October 2009 I traveled back to Albania. It was then that I decided that I should make a book.

TB: Albania, over the course of the past century, has been hindered by hardship and set-backs, and is still today finding its place in modern Europe. Were you daunted by the task of representing the complicated history and current problems of a country that is not your own?

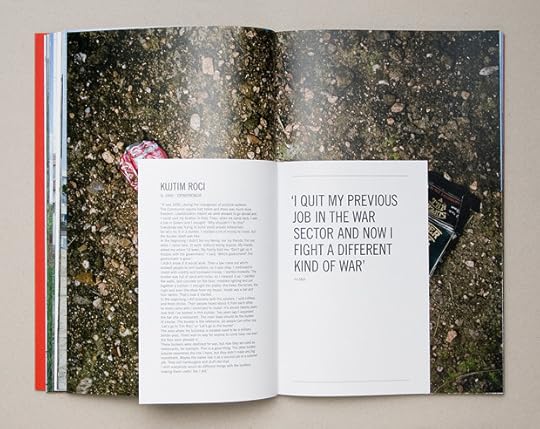

DG: Yes, there were two big questions for me: can I use the bunkers as a visual metaphor in the telling of a larger social story? And, can I tell a story about a country that I don’t live in? I read a lot and spoke to a lot of people, and I tried to work as closely to facts as I could. But in the end every text, from The Pillbox Effect by Slavenka Drakulić, to the interviews, to my pictures, are all personal impressions. There are even texts in the book that are in contradiction. My mission was not to say, “This is truth. This is Albania.” It’s just an impression of a country, as close to a truth as possible, but perhaps just one of many truths. I hope I found a way to not approach the country in an arrogant way, coming in and telling everybody, “This is Albania,” because that is not what I intended to do.

TB: The texts in Concresco are important for contextualizing the photographs, and I found that reading the intermittent booklets of personal testimonials heightened my interest in the images–the more I read, the more I wanted to see. Was it always your intention to include texts in the book, or did you ever consider Concresco exclusively as a book of photographs? How important for you is the interaction of words and images?

DG: I read [Drakulić’s] essay The Pillbox Effect during my second trip to Albania, and that really helped me decide that this project had to become a book. I was working with all this information I had about the country, and I was trying to put as much information as possible into my pictures. But I knew even without seeing my pictures yet that they would not be enough to tell the whole story. I wanted to do the best I could, but at a certain point you hit a wall, and need something more to really explain the story. I make my images with a lot of information in them, but you also need other information to understand them.

On my second trip, I was approached by a Dutch documentary filmmaker who was making a movie about the bunkers and we made a deal that I could use the raw material of his interviews and I would show him all the locations he needed. So the interviews of the [older] Albanians came from him. I did the interviews with the younger people myself, because I wanted to know more about the present and future [of Albania], and I could speak English with those people. The older people, who built the bunkers, or were trained in them, were done by Sarah Haaij and Martijn Payens. You can find texts from my book in their film Mushrooms of Concrete, and they used one of my pictures for the film poster, and my designer did the design of the poster, so there were some other crossovers too.

I knew quite early in the process that I needed text, so I also wrote to Drakulić and asked if I could use this essay from her book, and she said yes. So there are two different kinds of text in the book, the two longer stories [from Drakulić and Jaap Scholten] and the short interviews with Albanian people.

Regarding the different sizes of paper, first it started off as a solution to a practical problem, because I wanted to use as little text as possible. I’m a photographer, so of course I want to tell as much as possible with images, and only use text when I must. In the end we only had short pieces of interviews, and it just didn’t work out in the design to put them on a big page. So, we put them on a smaller page, and it was at that moment that I found out that it was a really great way to play in the editing, and things got exciting from there. It turned out to be a great way to make new connetions between the images and the text, and it gave me a lot more room to play, and that felt amazing. It really added another dimension to the book.

At Home with the Fotohof

by Amanda Hopkinson

Fotohof. Zhe Cehen installation view and exterior section.

Photography galleries no longer survive simply as rooms with framed pictures on the walls. Many are yet to assimilate this premise, with predictable—and often lamentable—results. A pioneering reinvention of one venue is the Fotohof that opened in Salzburg, Austria, in February 2012. It is an airy and alterable space that the innovative designers transparadiso describe as “open transparent architecture.” The Fotohof tempts passersby with an outward-facing panel of plasma screens of with scrolling images, beyond which they can see a changing spread of indoor exhibitions and activities integrating the social, educational, and cultural.

Even the name is suggestive: originally, a hof was a farmstead or a courtyard; today the term is most often applied to an inn or a pub. Somewhere homely, in short, and indeed the gallery was formerly located in the picturesque Nonntal district at the foot of a mountain. The new Fotohof retains an emphasis on warmth and welcomeness, without the chintzy associations. In the words of Fotohof photographer and collective member Kurt Kaindl, the new building was planned from scratch “by all of us working together with the architecture firm transparadiso. We all agreed on a lot of glass so you can look from outside into every single room (except the bathroom) and allow those inside to see what’s going on in the library, or the offices, or outdoors on the street.” As an example, the library’s more than ten thousand core volumes, a remarkable resource, are available for both research purposes and for presentation in exhibitions alongside photographic prints, affording an insight into how content alters with context.

Fotohof. Installation view.

This is the Fotohof ‘s fourth home in forty years. The organization was created and is run by a remarkably consistent photographic collective of around twenty members. The first gallery was in someone’s living room; the second was a couple of tiny rooms in a shared flat. What persists is a group of photographers who continually reach out to new audiences without being impelled by either commercialism or self-promotion. The new space may be more formal, but the motivation remains to present fine-art photography at the highest level. The institutionalization resides in the Fotohof’s newest aspects, which are paradoxically also the most traditional: in the library; the pedagogical remit; and the homage to Inge Morath (whose work is on regular display in a number of curated exhibitions). The innovation lies in the continual (re)discovery of new talent, from home and abroad; the flexible spaces in which photography can be shown; and in extending the book library to the new Artothek print-lending library. Visitors are encouraged to rent framed prints they like (for €4 per month and for up to one year) and so become accustomed to living with fine original artwork on their walls—whether or not they finally decide to purchase them, and with no pressure to do so.

The combination of high artistic standards and collective commitment is evidenced by the new premises. The building is sited in the working-class district of Lehen, where dilapidated 1960s-era apartment blocks were demolished and rebuilt as low-rises flanking a new square. Named Inge Morath Platz, after the seminal photographer who was an early member of Magnum Photos and wife of American playwright Arthur Miller, it is intended as at once an homage and a celebration. The name is reinforced by a new, annual Inge Morath award for female photographers under the age of thirty. Throughout the summer, the Fotohof screened work by recent finalists—Olivia Arthur, Lurdes R. Basoli, Zhe Chen, and Emily Schiffer—alongside Morath’s own early work from Spain.

Fotohof. Main gallery. (top) Fotohof. Dirk Braeckman installation view. (bottom)

Across and around the square original residents have been re-housed in ecologically sensitive buildings. All were invited to the opening, where they were greeted by the mayor of Salzburg, the Minister for Education, Arts and Culture, local City councillors, and Belgian photographer Dirk Braeckman, who spoke with Jeffrey Ladd about his work, which inaugurated the new galleries. To mark the festive occasion, new work by contemporary Austrian artists was presented on-screen and Fotohof staff provided tours of the different areas of the gallery.

Such a high-profile launch demonstrates the commitment, at municipal and federal level, to the project, which necessitated ten years of discussion and planning among officials, photography practitioners, and activists. The importance of the state in making this happen can hardly be over-estimated. Under a scheme to support cultural and social institutions the City of Salzburg negotiated a fifty-percent rent reduction on commercial rates with the property developers, adding a grant of €600,000 for furniture and equipment. Overall the Ministry of Culture now provides fifty percent of the Fotohof’s operating costs, while the city and county of Salzburg each provide an additional twenty-five percent. According to Fotohof member Kurt Kaindl: “We have remained a non-profit organisation since we started in 1981, and we are not employers. All those who work on our projects are remunerated according to the tasks they do. Roughly fifteen people who work in the gallery on a regular basis are on the executive committee, deciding on exhibitions, book projects, and the overall strategy of the gallery.”

Fotohof. Bookstore.

For government at both national and local level to back such a scheme is exceptional in modern Europe, even in a country whose contribution to the field of photography is as important as Austria’s. For the past decade, governments across Europe have increasingly assumed that the private sector should provide funding for culture, whether it actually does or not. Culture is subsumed within a changing grab-bag of ministerial portfolios, including leisure, tourism, women, media, or sport: at best it is an optional add-on. Within Austria, the Fotohof is regarded as a trailblazer, the first element in a cultural hub that will include the new Galerie der Stadt Salzburg; the Literaturhaus; the Galerie Eboran, and the City of Salzburg Library.

Andrew Phelps, an American photographer and Fotohof collective member since the early 1990s, embeds the national enterprise within a wider tradition. “The Fotohof was founded a decade after the British Photographers’ Gallery. Both London and Cardiff [where Ffotogallery was directed by American Bill Messer] were early models. And our first exhibitions included several that travelled from there.” While we can all do with state support to make things happen, the arts are everywhere at home.

Fotohof. Exterior view.

–

Amanda Hopkinson is Visiting Professor of both City (of London) and Manchester Universities. She has written and translated numerous books of both literature and photography, mainly from Latin America and Europe. Most recently she curated an exhibition and compiled the catalog of the work of her mother, Gerti Deutsch. Hopkinson wrote on London’s revamped Photographers’ Gallery for Aperture’s Summer 2012 issue.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers