Aperture's Blog, page 207

November 15, 2012

PhotoBook of the Year Shortlist – VIDEO

PhotoBook of the Year Shortlist / Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards from Aperture Foundation on Vimeo.

In this installment we’re highlighting the ten titles shortlisted for the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook of the Year Award 2012.

Stay tuned for the final announcement, to be revealed November 16 at Paris Photo and on The PhotoBook Review website.

November 13, 2012

First PhotoBook Shortlist, Pt. 2 – VIDEO

First PhotoBook Shortlist Pt. 2 / Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards from Aperture Foundation on Vimeo.

With this week’s opening of Paris Photo, we’re highlighting the thirty shortlisted titles for the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards 2012.

Stay tuned for the final announcement, to be revealed November 16 at Paris Photo and on The PhotoBook Review website. In the meantime take a closer look at the publications competing for the prize in the First PhotoBook category.

November 12, 2012

First PhotoBook Shortlist, Pt. 1 – VIDEO

First PhotoBook Shortlist Pt. 1 / Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards from Aperture Foundation on Vimeo.

With this week’s opening of Paris Photo, we are thrilled to celebrate the thirty shortlisted titles for the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards 2012, soon to be on view in a full exhibition in the Grand Palais at Paris Photo, November 14–18.

Selected by a jury in New York and announced earlier this fall in The PhotoBook Review 003, the thirty shortlisted publications now await a final round of judging in Paris to determine the winners in the First PhotoBook and PhotoBook of the Year categories.

Stay tuned for the final announcement, to be revealed November 16 at Paris Photo and on The PhotoBook Review website. In the meantime take a closer look at the publications competing for the prize in the First PhotoBook category.

November 9, 2012

The Neighborhood Ketchup Ad: Photography and Housing in Unzoned America

Gregory Crewdson, Untitled, 1998-2002.

This essay appears in Aperture #209, the winter 2012 issue of the magazine.

By Tim Davis

Photography used to be a blue-collar job. You were on your feet all day, out in the elements, hands in chemical baths. Now it’s white-collar; in front of a monitor. Still I went ahead and bought a digital camera, thinking it’d make my world time more fluid. I could walk faster than I did with the view camera I’d been shouldering all my life, and it would balance out the screen time (which I call “watching TV”). This was 2008, and the world was turning loud and ugly. I would stroll around the small cities within my reach, being the Bear Who Went Over the Mountain. Remember why he did that? To see what he could see.

I didn’t make too many good pictures with that digital camera. It was almost as if, with every frame costing me nothing, I couldn’t make a picture matter. But it was okay for collecting. A digital camera makes a good Sherpa; it can carry your necessaries. I listened to the news on the way to these small cities: the Republicans were blaming the poor for the financial meltdown. Seems they had gone and bought a bunch of houses they couldn’t afford. Neil Cavuto on Fox News came out and said it: “Loaning to minorities and risky folks is a disaster.’”

But on the achy streets of Newburgh and Scranton and Pittsfield and Troy, it became obvious that very few of these “risky folks” owned their own homes. Mailboxes were festooned with names and coated and recoated with paint as families moved on. People rented, and their mailboxes told tales of just how hard it can be to get housed. These streets were very far from Ronald Reagan’s imaginary “Cadillac-driving welfare queens.” There were gas stations where the corner store ought to be, bathing porches in troubling alien light. Instead of McMansions bought with WIC checks, a lot of this country lives in an unzoned miasma of the almost-commercial. America loves its flux, and where we live is rarely solid, rarely stable. And it’s always been that way.

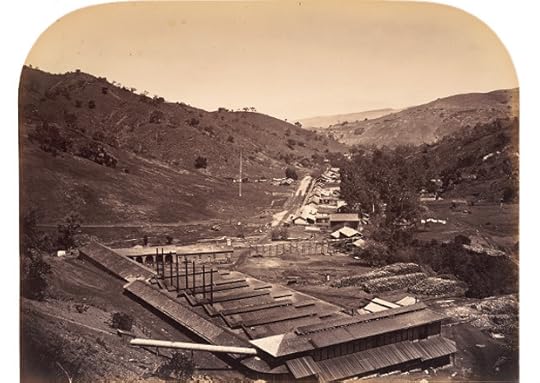

Carleton E. Watkins, Hacienda, View East, 1863.

De Tocqueville noticed how functional America’s landscape was: “If they repudiate all ornament from their architecture, and set no store on any but practical and homely advantages, it is not because they live under democratic institutions, but because they are a commercial nation.” Carleton E. Watkins was the first great poet of the American practical landscape. No one doubts why Watkins was photographing. A childhood friend of Collis P. Huntington—one of the robber barons Ambrose Bierce would refer to as “railrogues”— Watkins worked for logging and mine companies making majestic mammoth-plate pictures of their claims and processing plants. In among the factories and log piles, you can sometimes see where people lived. In Hacienda, View East (1863), the sprouting hamlet of New Almaden, California, trails off in the distance like tailings of the quicksilver mine enveloping the foreground. Housing in Watkins is almost always an afterthought to commerce. Tiny clapboard houses cling to the San Jose road like remoras on the mouth of a shark, hoping for scraps. The landscape is so barren, the nonpanchromatic film emulsion blasting the blue sky white, that it is difficult to imagine anyone living in this place except to work. It had only been fourteen years since Thoreau published A Week on the Concord and Merrimac Rivers, where he noticed: “Men are as busy as the brooks or bees, and postpone everything to their business; as carpenters discuss politics between the strokes of the hammer while they are shingling a roof.”

It is difficult to look at this image without imagining all this activity burning itself out. Today the mine is the perfect American hybrid: a Superfund site and a museum. The village’s population hasn’t changed since 1863. Its most famous resident, Pat Tillman, died on a hillside in Afghanistan that would not look odd superimposed into Watkins’s photograph.

In America the landscape changes. And so house and home, the very seats of human stability, are always subject to alteration. Zoning is a relatively new concept here. There was none at all until the rise of the Progressive movement in the teens. So, in 1936, when Walker Evans and Peter Sekaer rolled through the South following an itinerary set by Farm Security Administration director Roy Stryker, they found natural clashes between the domestic and the commercial. Evans’s signature image, of two Atlanta frame houses bounded by a wall of billboards, perfectly describes the commercially contingent state of U.S. housing.

Walker Evans, Houses, Atlanta, Georgia, 1936.

The long lens on Evans’s 8-by-10 view camera helped to flatten the space between these Victorian houses—already decaying— and the rush of Hollywood advertising on the street. Just a few months earlier, in New Orleans, Evans had found a similar situation, photographing a two-story house with a ketchup ad for a neighbor. In the New Orleans image, the house is skittering with activity. Whole families lean out over balconies. The house is framed in its entirety and can be read like an advent calendar, with each columned bay revealing human activity. The billboard is cut off at the edge of the picture. In Atlanta, the houses are unpeopled, maybe uninhabited. The commercial hunger of Hollywood is outpacing the architecture.

Despite this clash between the residential and the mercantile, Evans’s picture-making style is, as ever, formally direct and solid. Its straightforward geometry makes it easy to look at this image and imagine the movie posters lasting as long as Roman inscriptions. Three years later, however, John Vachon, having started at the FSA as a file clerk, was sent to the Deep South for the first time as a photographer. He immediately tried to locate the houses in Evans’s picture. “I found the very place, and it was like finding a first folio Shakespeare. The signs on the billboard had changed, but I photographed it, and it’s in the file.” The two pictures together are a Muybridge-ish study of the ways an American house is as much a unit of measure of the country’s commercial climate as it is a home.

John Vachon, Houses, Atlanta, Georgia, 1938.

Evans was delighted with his finds. Restlessly modern, he saw progress in old houses giving way to new advertisements. As the twentieth century rolled along, these piquant, ironic incursions into domestic life gave way to heady despair at the spread of the housing-industrial complex. Robert Adams’s What We Bought (1970–74) plotted the spread of housing as a metastasizing growth in the Denver landscape. In its opening image, a big square creosote bush sits in middle of the frame in the middle of the prairie. It’s white hot and timeless, except for the creep of prefab development deep in the background. From there, houses spring up on and are dug into the land. At the edge of the city, they struggle for space—both in the world and in the frame—in a jungle of convenience stores and service (Gigantic Cleaners, Birdie’s Hair Styling). By plate 51, beyond the final ring road, the new houses reign supreme, and it’s a wasteland of a kingdom. Houses are packed into lots spread soullessly to the horizon. It’s always midday. The housing itself has become industrial. You can’t imagine the buildings being built: they feel extruded or minted or mined. The photographer is angry at this development, and his pictures have some of the sentiment of Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang: “These machine-made wastes grew up in tumbleweed and real-estate development, a squalid plague of future slums constructed of green two-by-fours, dry-wall fiberboard and prefab roofs that blew off in the first good wind.”

Robert Adams, Untitled (Mobile home park), 1970-74.

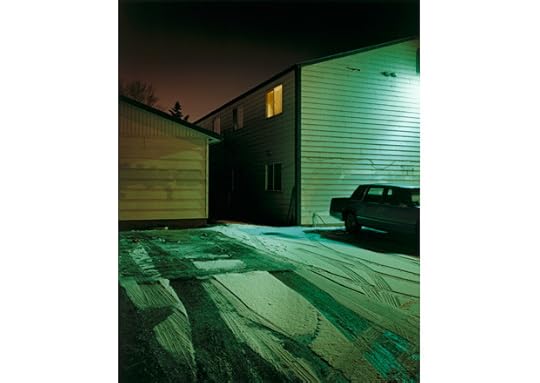

Photography is a complicated form of protest, though, because the camera is so accepting. Cameras are golden retrievers, and the world is a tennis ball. Adams is clearly horrified at the infectious spread of the prefab, but his photographs can’t help being moved by its patterns and symmetry and novelty. As photography moves to its new digs in the glitzy high rises of Contemporary Art, the seduction of American housing, even in its ticky-tacky suburban spread, tends to almost outstrip the politics and social concerns of its makers. Todd Hido’s series Houses at Night works are first-person accounts of life on the ground in this postpolitical neighborhood. The houses he photographs are exactly those Abbey described, barely able to survive their poor construction in the onslaught of car culture and the cul-de-sac. Hido’s pictures have a color palette all their own, an acidic roux of film emulsion and the color temperature of mercury- and sodium-vapor industrial lighting, in combinations no painter would stir up. And they are very much about this color, how photographic and how god-awful glamorous it is. Reasons and responsibilities, class and race and zoning and planning, fade into a sublime haze.

Todd Hido, #7373, 2009, from the series Houses at Night.

Larry Sultan’s series The Valley sums up the trajectory from house as social document to private fantasy beautifully. In Backyard, West Valley Studio (2003), we have landed back in Carleton E. Watkins’s California. Again housing slips to the background of a vital U.S. industry. But this one is designed to bypass sight and cognition, and head straight for the pleasure centers. The housing on the other side of the fence, which could have been cropped easily from an Adams or a Hido, is a scrim, put up to protect a pornographic spectacle from real neighbors in real houses. Someday, on this spot, there will be a Superfund site and a museum.

Larry Sultan, Suburban Street in Studio, 2000.

Tim Davis is an artist and writer living in Tivoli, New York. His new project, an album of songs with accompanying music videos, is called It’s OK to Hate Yourself. He teaches photography at Bard College.

Image credits:

Carelton E. Watkins, Hacienda, View East, 1863. Courtesy the Huntington Library, San Marino, California

Walker Evans, Houses, Atlanta, Georgia, 1936. Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection.

John Vachon, Houses, Atlanta, Georgia 1938. Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection.

Robert Adams, Untitled (Mobile home park), 1970-74. Courtesy Yale University Art Gallery.

Gregory Crewdson, Untitled, 1998-2002. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery.

Todd Hido, #7373, 2009, from the series Houses at Night. Courtesy Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York.

Larry Sultan, Suburban Street in Studio, 2000. From the series The Valley. Courtesy the Estate of Larry Sultan.

November 8, 2012

Alec Soth – on Influence, Summer Nights, and Allen Ginsberg

This video, Summer Nights at the Dollar Tree , is Soth’s response to Adams, and is featured in the Aperture Remix exhibition on view at Aperture Gallery through November 17.

Soth spoke with Aperture Remix’s curator Lesley A. Martin about influence, Summer Nights, and Allen Ginsberg. The resulting conversation appears below, and is also included in the artist book Soth created as part of Aperture Remix.

Lesley A. Martin: For this project, you were asked to engage directly with an influential body of work—and with the photographer who created that body of work. What was the most difficult thing about that process?

Alec Soth: A few years ago I became really frustrated with photography. In order to continue working, I felt like I needed to take apart my process and to examine things before putting them all back together. One of the things I did was make re-creations of other people’s photographs. For example, I shot half a dozen versions of Migrant Mother. The point of this wasn’t to try and make my own iconic image—I was a more in the role of a student going to the museum and sketching from the masters.

What made this project different, and more difficult, was the looming presence of Robert Adams. In the case of Migrant Mother, I didn’t have to worry about Dorothea Lange and her opinion. But since this particular experiment was initiated by Aperture, Adams’s blessing was a necessity.

In the beginning, Mr. Adams graciously engaged in a letter correspondence with me. This was great, of course, but it was also inhibiting—it actually prevented me from having a dialogue with the core of his influence.

LAM: In other words, your dialogue became more about attempting to chat with esteemed, iconic master Robert Adams, rather than about an engagement with a set of actual ideas and images?

AS: Basically. Also, to borrow from Blake, my appreciation of Adams is all about innocence and experience. When I discovered Summer Nights I was discovering photography. The world felt so new. But that was a lifetime ago. It is hard to scrub your eyeballs of all that experience.

LAM: Exhibitions are an important way to experience work, but more often than not a book falls into one’s hands and becomes a primary way to engage with a set of images. How did you first encounter Robert Adams’s work and, more specifically, what is it about Summer Nights that you’ve found to be inspirational, maddening, or otherwise of interest to you personally?

AS: Almost all of the work I discovered as a young photographer was in book form. More often than not, I found these books at place called Half Priced Books. This store would always have books by popular photographers like Annie Leibovitz and Ansel Adams. They would also often have Robert Adams books. The first time I saw an Adams book, I remember wondering if he was Ansel’s son.

Early on, I wasn’t particularly taken with his books. They were too dry for me. But when I was twenty and discovered Summer Nights, things clicked. It is easy to see why. Summer Nights is his easiest book to digest. I think of it as the Robert Adams gateway drug. It certainly worked that way for me. I immediately went out and started taking night pictures. I didn’t find the book maddening at all. It just lit a spark for a kind romantic solitude.

LAM: Summer Nights, with its dark, empty streets; views through lamp-lit windows; and the lights of the carnival ride at night definitely feels different from the cooler assessments he seems to make in some of his other books. It tips his hand as a sentimentalist—in the best possible sense of the word—in a way that few other of his books do. His work also operates on a highly moral level, which seems to come from a sense of loss as much as judgement. Would you agree with that assessment?

AS: Yes, I would describe Adams as both a romantic and a moralist. You might even say he is romantically moral.

LAM: Has that sense of morality challenged you as a photographer?

AS: Absolutely, yes. As I said, Summer Nights was the gateway drug. As the years went by, I took on the harder stuff and, in fact, came to appreciate most of it more than Summer Nights. Los Angeles Spring is probably my favorite Adams book.

That said, I’m always aware of the fact that my moral temperament is vastly different from Adams’s. While I admire his conviction, I don’t feel the same outrage. Part of what I love about Los Angeles Spring is that it teaches me to find beauty in difficult places. I’m more interested in that beauty than in the anger that fueled Adams to go out and find it.

But the issue of rigor is more complicated. Adams is an incredibly rigorous artist—he is almost pious in his practice. I admire that and have longed for it to be a part of my work. There were times as a young artist when I emulated people like Richard Long. And God knows I’ve had plenty of fantasies of retreating to an adobe hut in the desert and purifying my practice.

One of the lessons I’ve learned from studying Adams—and others who live and work with his kind of rigor—is that I’m simply not that person. I grew up playing in the woods with my imaginary friends, but then I would come in at night and sit in front of the TV for a few hours. I’m a product of both those experiences.

LAM: To what extent do you think a young photographer needs to confront his or her influences, and at what point does one need to identify what one has learned and move on?

AS: It has always been important for me to wrestle with my influences. In college I studied under Joel Sternfeld. At the time, I was sort of embarrassed by his influence, so I made work that was as different as possible. But that was a waste of time. It was only when I worked through his influence that I really started to grow. Over time, you begin to understand influences and the nuances of what makes your own work different.

Photography is a language. To communicate, you need to learn the language. The history of photography is like the vocabulary and influence is like a dialect. One shouldn’t be embarrassed about having an accent. That said, it has been important for me to reevaluate those influences as the years go by.

There is a kind of mythmaking that inevitably surrounds influential artists. For me, it is more and more important to figure out how to function as a real-life human being than to emulate some sort of myth. I feel like I can now learn more from my influences by understanding the compromises and everyday challenges they faced than by upholding a schoolboy fantasy.

LAM: The anxiety of influence is hard to escape: one of the most deflating commentaries that someone can make about artwork is that it is “derivative.” In the context of thinking about photography as a language, however, I like your imagining work as “accented” one way or another.

At the very beginning of Why People Photograph, Adams writes: “Your own photography is never enough. Every photographer who has lasted has depended on other people’s pictures too.” How easy is that to acknowledge—both in terms of people from whom you’ve learned from and in terms of people who are following in your own wake?

AS: I’d be lying if I didn’t say the “derivative” jab can be deflating. But I think it is dangerous to obsess over this issue. It is better to grapple with your influences than run away from them. I learned a lot about about what defines my particular vision by figuring out how it differs from those who’ve inspired me.

In Adams’s essay, “Making Art New,” he quotes Matisse, who said, “I have accepted influences but I think I have always known how to dominate them.” I’m no Matisse, nor have I always known how to dominate my influences, particularly as a young photographer. But as time goes by, I have a better sense of who I am and how I might be able to move my particular football a little further down the field.

So I’m comfortable talking about my influences. As for those who may have been influenced by me, well, I’m not sure what to say about that.

LAM: I’m curious about the other side of the coin of influence—i.e., the self-consciousness one can feel once one’s own path has been established, a path that might stray away from or push beyond one’s mentors. The Allen Ginsberg quote you’ve included in this book, about Whitman, seems to express Ginsberg’s own yearning for kinship and respect while also consciously throwing out a dissonant image—“neon fruit supermarket”—that is hardly Whitmanesque. What’s that about for you?

AS: Ginsberg saved the day for me. “A Supermarket in California” clearly illustrates Whitman’s profound influence on Ginsberg, but Ginsberg’s voice rises above it. He sings with Whitmanesque bravado, but it’s still Ginsberg’s world. The poem wouldn’t work if Ginsberg had written about Civil War soldiers. He needed to use his own universe of neon supermarkets in order to say anything meaningful about Whitman.

Along with reading Ginsberg’s poetry, I read some interviews with him in which he talked about influence. In an interview in the Paris Review he talked a lot about William Blake. I had been thinking about Blake because Adams quotes him at the beginning of Summer Nights. But, of course, Adams quotes him in a really understated way. In this interview, Ginsberg talks about a vision he had after masturbating while reading Blake. I found this kind of exuberance refreshing. It helped me shake loose from some of the somber reverence I sometimes feel when engaging with Adams’s world.

LAM: That’s definitely a different invocation of Blake than the one found at the beginning of Summer Nights. In the Paris Review piece you mention, the interviewer keeps bringing up classical reference points, trying to tie Ginsberg to various literary traditions. Ginsberg bats them away, insisting that his writing is arrived at “organically rather than synthetically.” He states that his own challenge was to be able to accept writing outside of preconceived notions of what literature should be—and instead to “approach the Muse to talk as frankly as you would talk with yourself or with your friend.” In other words, he seems to be encouraging us not to take the weight of literary tradition too seriously and to trust in our own intuitions and inspirations, which can be found in both old and new; to be both traditional and taboo-busting, if you are open to it. Is this relevant to your own process of making work, of having found an authentic voice for yourself?

AS: Absolutely, yes! Here’s the thing: I love Robert Adams. But I also love the TV show Breaking Bad. I don’t see that as a contradiction. In fact, I can see similar issues of morality and the American social landscape in both. Would Robert Adams like Breaking Bad? I doubt it—and that’s just fine. But for me to have an authentic voice, I need to follow whatever stirs me. Maybe it would make me a better citizen if I read Wendell Berry rather than watched Breaking Bad, but it wouldn’t make me a better artist.

LAM: I’m curious to hear about how you arrived at video as a response to this project?

AS: I needed to shake things up. When I tried going out to take night stills, I just couldn’t get the blood pumping through my veins. The world I was looking at didn’t feel new. It felt like Robert Adams’s world.

I had a new camera with a video option that I’d never used. I didn’t really know what I was doing technically, but that was an asset. It felt good to be a bit lost.

The biggest thing about using video was the sound. Playing back the footage after my first night of shooting, I was so aware of the sound of the evening. For me, this is what really evoked the feelings I first had of seeing Summer Nights—the sort of solace that one can find as darkness and quiet settles over the landscape.

Alec Soth (American, b. 1969) has been the subject of many exhibitions, including The Space Between Us, a major retrospective presented at the Jeu de Paume, Paris, and Fotomuseum Winterthur in Winterthur, Switzerland, in 2008, and From Here to There, presented at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, in 2010. Among Soth’s monographs are Sleeping by the Mississippi (2004) and Broken Manual (2010). In 2008 Soth started his own publishing company, Little Brown Mushroom. He is a member of Magnum Photos.

November 7, 2012

The Latin American Photobook

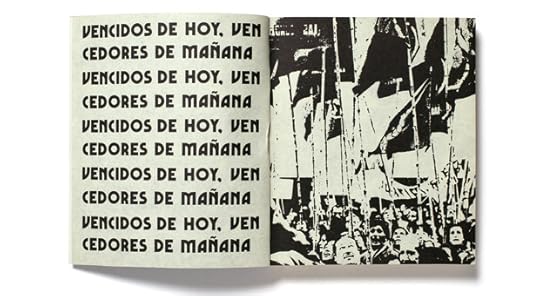

Chile o Muerte by Armindo Cardoso

Chile o Muerte by Armindo Cardoso

Doorway to Brasilia by Aloísio Magalhães and Eugene Feldman

Doorway to Brasilia by Aloísio Magalhães and Eugene Feldman

Amazonia by Claudia Andujar and George Love

Amazonia by Claudia Andujar and George Love

Retromundo by Paolo Gasparini

Retromundo by Paolo Gasparini

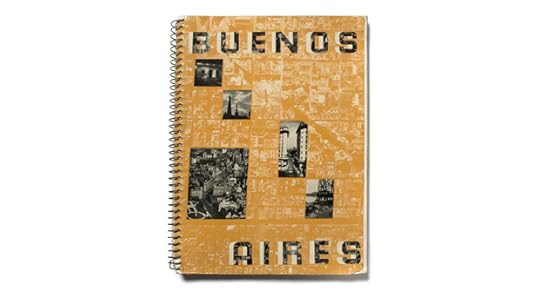

Buenos Aires by Horacio Coppola and Grete Coppola

Fotografias by Manuel Alvarez Bravo

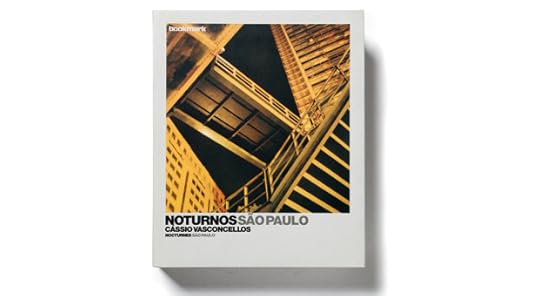

Noturnos Sao Paulo by Cassio Vasconcellos

Opening Reception: Thursday, November 29, 6:00-8:00 pm

The Latin American Photobook Symposium: Friday, November 30–Saturday, December 1

The Latin American Photobook, featuring a selection of volumes from the 1920s to the present, provides revelatory perspectives on the under-charted history of Latin American photography.

A growing appreciation of the photobook has encouraged a flood of new scholarship and connoisseurship of the form. Few projects have been as surprising and inspiring as The Latin American Photobook, the culmination of a four-year, cross-continental research effort led by Horacio Fernández (Spain), author of the seminal volume Fotografia Pública (1999). Compiled with the input of a committee of researchers, scholars, and photographers—including Marcelo Brodsky (Argentina), Iatã Cannabrava (Brazil), and Martin Parr (United Kingdom)—The Latin American Photobook publication presents one hundred and fifty volumes from Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, Mexico, Nicaragua, Peru, and Venezuela. The book was published in Spanish by Editorial RM, in English by Aperture Foundation and Fundación Televisa, in Portuguese by Cosac & Naify, and in French by Images en Manœuvres.

The accompanying exhibition, presented earlier in 2012 at Le Bal, Paris, and Ivory Press, Madrid, features work by great figures such as Claudia Andujar, Barbara Brändli, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Horacio Coppola, Paz Errázuriz, Graciela Iturbide, Sara Facio, Paolo Gasparini, Daniel González, Sergio Larraín, and many others. On view are photobooks, vintage and modern photographic prints, videos of books, maquettes, notes, and studies for mock-ups. The photobooks are divided into seven thematic sections: America Before America, History and Propaganda, Urban Photography, Photo Essays, Artist’s Photobooks, Literature and Photography, and Contemporary Photobooks. This not only allows the visitor to explore individual photobooks and photographers, but also Latin America’s manifold social, political, and art histories.

Curator Horacio Fernández is a photo-historian and author of numerous catalogs and books, including Fotografía Pública: Photography in Print 1919–1939 (1999). He has been a senior lecturer at the Facultad de Bellas Artes in Sevilla, Spain, since 1988. Between 2004 and 2006 he was general curator of PHotoEspaña, the annual international photography festival in Madrid.

The Latin American Photobook was co-published with Fundación Televisa.

The Latin American Photobook exhibition and symposium is made possible, in part, with support from the National Endowment for the Arts, Tinker Foundation, The Council for International Teaching and Research and the Program in Latin American Studies at Princeton University, the Instituto Moreira Salles, Estrellita and Daniel Brodsky, and the Mexican Cultural Institute of New York.

Aperture Remix Exhibition – Video

November 5, 2012

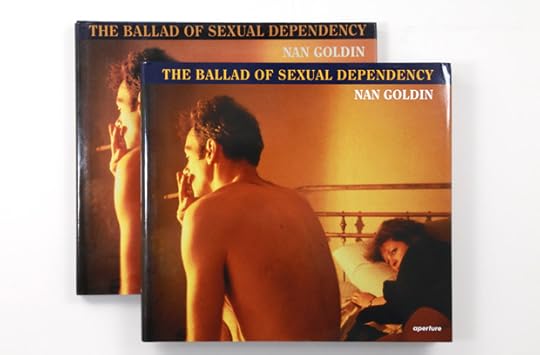

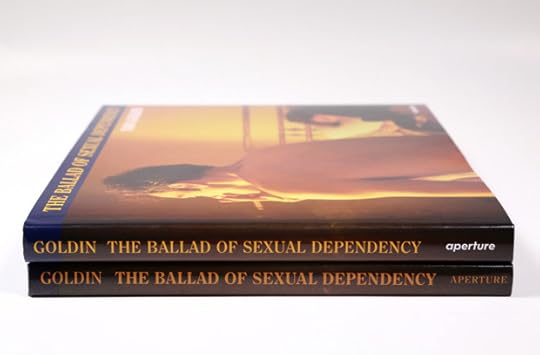

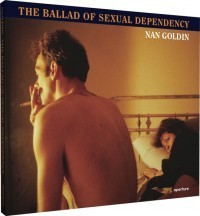

Nan Goldin – The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – Reprint

Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is a visual diary chronicling the struggle for intimacy and understanding between friends, family, and lovers—collectively described by Goldin as her “tribe.” Her work describes a world that is visceral, charged, and seething with life. As Goldin writes, “Real memory, which these pictures trigger, is an invocation of the color, smell, sound, and physical presence, the density and flavor of life.”

Through an accurate and detailed record of her life, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency reveals Goldin’s personal odyssey as well as a more universal understanding of the different languages men and women speak, and the struggle between autonomy and dependency.

First published in 1986, this reissue recognizes the persistent relevance and freshness of Nan Goldin’s cutting-edge photography. Over the past twenty-five years, the influence of Ballad on photography and other aesthetic realms has continually grown, making the work a contemporary classic.

This new edition of Ballad has been printed using new scans and separations created by master-separator Robert Hennessey from Goldin’s original transparencies, rendering them with unparalleled sumptuousness and impact.

For more on Nan Goldin and The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, see:

· The Guardian

· The Paris Review

· MoMA

· BOMB Magazine

· ASX

The Ballad of Sexual DependencyPrice: $50.00

The Ballad of Sexual DependencyPrice: $50.00

Lynne Cohen – Occupied Territory Exhibition & Book Signings

In 1987, Aperture published Lynne Cohen’s first photo book, Occupied Territory, an exploration of space as simulated experience—both idealized and standardized. The expanded reissue of Cohen’s monograph was released earlier this year, delivering her pioneering work to a contemporary audience and situating her images within the lineage of Lewis Baltz, Stephen Shore, and other widely celebrated New Topographics photographers.

In celebration of the Twenty-fifth Anniversary of Lynne Cohen’s Occupied Territory, join the photographer at two events in North America this month:

Montreal

Artist Talk and Book Signing: Lynne Cohen

Thursday, November 8, 2012, 6:00 pm

Paragraphe Bookstore

Montreal

New York

Lynne Cohen: Occupied Territory Opening Reception and Book Signing

Saturday, November 10, 2012, 4:00 pm–6:00 pm

Higher Pictures

New York

Image: Lynne Cohen, Corporate Office, from the series Occupied Territory Occupied Territory Price: $60.00

Occupied Territory Price: $60.00 Model Dining Room, from the series Occupied TerritoryPrice: $900.00

Model Dining Room, from the series Occupied TerritoryPrice: $900.00

A2/SW/HK – Designers for the new Aperture magazine

Aperture has hired the London-based graphic design team A2/SW/HK (Scott Williams and Henrik Kubel) to redesign the magazine. One of A2’s specialties is typography—they draw unique fonts for each client—and they are working on a set of fonts for their fresh design of Aperture. Scott and Henrik’s extensive portfolio is full of smart, beautiful projects. We’re excited about what they’re doing for us right now, which you’ll see very soon. In the meantime, visit A2/SW/HK’s website to see their work.

Above: Samuel Beckett, complete works, 2009—2010, Faber & Faber, London. Cover design & bespoke typefaces by A2/SW/HK

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers