Aperture's Blog, page 206

December 3, 2012

With an Eye Toward the Future: On the 2012 Johannesburg Art Fair

By Daniel M. Leers

This year’s FNB Johannesburg Art Fair (FNB stands for First National Bank, the primary sponsor), the fifth iteration of the event begun in 2008, was a surprising mix of modern and contemporary art shown by galleries from both Africa and Europe. With the disappearance of the Johannesburg Biennale in 1997, there is palpable hunger in this country for artwork with global ambitions. The FNB fair does not provide exactly that, but it’s not too far off.

In terms of quality of work the fair was on par with other art events on the continent, such as the Dak’Art Biennale in Senegal and the Rencontres de Bamako photography festival in Mali. With twenty-four galleries from England, France, Germany, Nigeria, and South Africa, the fair included a diverse array of work by artists predominantly from Africa (though some were European). This diversity stems, in part, from the makeup of the Johannesburg population itself; the city is a melting pot of immigrants from all over the continent, a place where Zimbabwean, Malawian, and South African people share culture and space.

© Bridget Baker, Only-Half-Taken, 1959/2011-2012, 16-mm colour and 16-mm black-and-white expanded film installation. Image by Daniel Isherwood

Some of the highlights were found in booths not directly associated with a gallery, such as a large-scale installation of Deborah Poynton’s Arcadia paintings, or Bridget Baker’s film Only Half Taken (1959/2011–12). Kudzanai Chiurai won this year’s FNB art prize, granting him a small solo show of videos, photos, and sculptures from his State of the Nation series. Printed materials were available through Clarke’s Bookshop and Jacana Publishing, and sales of limited-edition prints from Art South Africa and Art Throb, two of the most important critical resources in the country, helped raise money to support their programming. Finally, a series of presentations called Arts Alive Art Talks, featuring twenty-minute lectures by curators and artists alike, provided more depth and nuance for the general audience in attendance.

© Kudzanai Chiurai, Untitled III, 2011 (top); Revelations II, 2011 (bottom), both from the series State of the Nation

Stevenson Gallery stood out from the other commercial enterprises by presenting a single work, Michael MacGarry’s monumental sculpture Future Proof, 2012, a cement mixer studded with nails and bolts in the vein of an African fetish figure. WHATIFTHEWORLD Gallery showed a variety of work from a new wave of up-and-coming artists emerging from the Cape Town scene, including Julia Rosa-Clark, Dan Halter, and Athi Patra-Ruga. Goodman showcased its strong stable of artists, and its booth’s high points were works by William Kentridge and pieces from Mikhael Subotzky’s series Retinal Shift, which explores the act of looking. Two videos from the series used security-camera footage publicly available from the Johannesburg police that shows violent crimes between black South Africans; they end with each arrested person forced to look up into the security camera for the purposes of identification. One crowd favorite was a work by Ed Young, in the Stellenbosch Modern and Contemporary Gallery booth, of a lifelike miniature of the artist hanging naked from a nail in the wall. It was fittingly titled My Gallerist Made Me Do It, 2012.

That the FNB Johannesburg Art Fair was a professionally executed and commercially successful event—every gallerist I spoke with reported strong sales—is no small feat in a country where the arts are tragically underfunded. The fair also received significant media attention. Judging by the crowds of curators, collectors, dealers, and the general public, there is a desire in South Africa to have more such events take place in the future. Hopefully, that desire can translate into exhibitions propelled out of the commercial sphere and into the daily workings of one of the most bustling cities on the continent.

Unfortunately, the Sandton area of Johannesburg, where the fair took place, is a giant mall, isolated from any of the surrounding townships and lacking the vitality that courses through other parts of the metropolis. Relocation to one of the more vibrant, up-and-coming parts of downtown such as Braamfontein or the Arts-on-Main district would provide a welcome shot in the arm. Braamfontein, centered on the University of the Witwatersrand, is home to the new Wits Art Museum, which is located in a former 1970s-era car showroom. Galleries and cutting-edge design stores have begun popping up in the area. Main Street, a central artery of downtown, cuts through neighborhoods such as Milpark, with its industrial buildings repurposed to house restaurants and shops, and the newly christened Maboneng (“place of light,” in the local Sotho dialect), which features a compound of renovated buildings with cafes, lofts, and performance spaces.

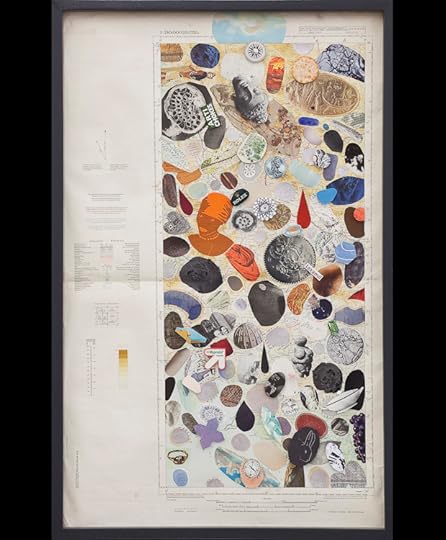

© Julia Rosa Clark, Coordinates of Gains & Sorrows, 2012

Moving the fair to a more centralized, diverse neighborhood—or, even better, bringing back the Johannesburg Biennale—would provide opportunities to expand the presence of art on the continent and beyond. Moreover, it could further the existing desire among young people in Johannesburg to create a new form of culture that participates in the greater global context while maintaining unique South African qualities. The philosophy behind this movement is one of Ubuntu (literally translated from the Xhosa as “I am because you are”), a bracingly fresh collectivist philosophy that looks back at South African history with an eye toward the future.

–

Daniel M. Leers is an independent curator based in New York City. Leers graduated with a BA in Art History from Lawrence University and an MA in Art History/Curatorial Studies from Columbia University. From 2007-2011 he was the Beaumont and Nancy Newhall Curatorial Fellow in the Department of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. During his tenure at MoMA, Leers worked on a variety of exhibitions, including New Photography 2011: Moyra Davey, George Georgiou, Deana Lawson, Doug Rickard, Viviane Sassen, Zhang Dali. Currently, Leers is acting as a Curatorial Advisor to the 2013 Venice Biennale.

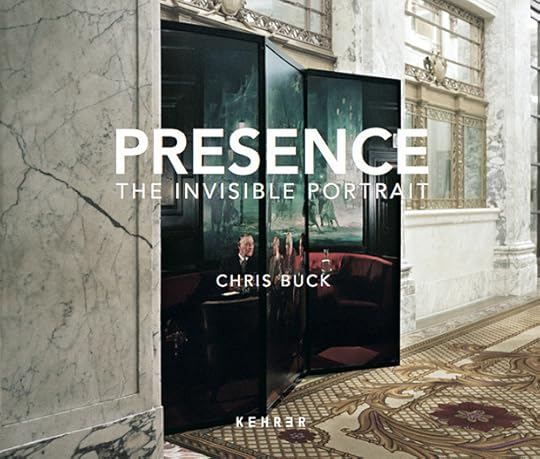

Chris Buck – Artist Talk and Signing

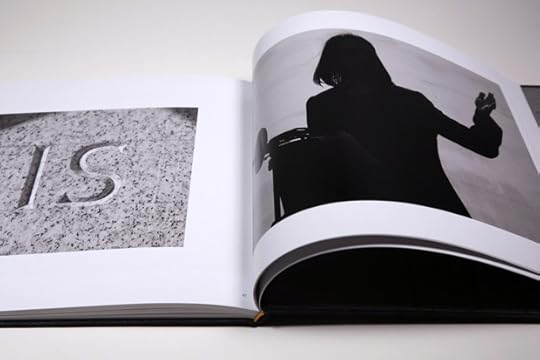

Tomorrow evening at Aperture Gallery, join Chris Buck for an artist talk about his first photobook, Presence: The Invisible Portrait.

Presence brings a counterintuitive and conceptual take on the desire to behold fame. A successful editorial portrait photographer, Buck ingeniously set up these shots so that, even without digital manipulation, no human figure can be seen. From the super-famous (Robert De Niro, Jay Leno, Snoop Dogg) to the legendary (Günter Grass, Chuck Close, Archbishop Desmond Tutu) to the notorious (Nick Cave, David Lynch, Sarah Silverman), the range of subjects and collaborators blurs the line between the indulgence of pop culture and the obliqueness of art photography. A book signing will follow the discussion.

For more on Presence: The Invisible Portrait, see:

· Cool Hunting

· Huffington Post

· GQ

Chris Buck Presence: The Invisible Portrait Talk and Signing

Tuesday, December 4, 2012

6:30 pm

Aperture Gallery and Bookstore

547 West 27th Street, New York

November 30, 2012

Trisha Ziff Discusses 101 Tragedies of Enrique Metinides

“There’s a huge contradiction for me between publishing and looking at these images, and how in the street—just in ordinary life—I respond to something gruesome that happens.”

Now available from Aperture, 101 Tragedies of Enrique Metinides is Metinides’s choice of the 101 key images from his life photographing crime scenes and accidents in Mexico for local newspapers and the nota roja (or “red pages,” for their bloody content) crime press. Alongside each image, extended captions give his account of the situation depicted, describing the characters and life of the streets, the sadness of families, the criminals, and the heroism of emergency workers—revealing much about himself in the process. Here, in conversation with Aperture Foundation executive director Chris Boot, editor, filmmaker and curator Trisha Ziff discusses her relationship to the images compiled with Metinides for 101 Tragedies of Enrique Metinides.

101 Tragedies of Enrique MetinidesPrice: $50.00

101 Tragedies of Enrique MetinidesPrice: $50.00

Taryn Simon and Lisa Hostetler – In Conversation

Listen to Taryn Simon present and discuss her work with Lisa Hostetler, McEvoy Family Curator of Photography at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, in this audiocast recorded Tuesday, November 27, at Aperture Gallery.

Simon is a contemporary photographer known for several bodies of work, including The Innocents (2003), Nonfiction (2006) An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar (2007), Contraband (2010), Image Atlas, and, most recently, A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters, I – XVIII (2011), which was exhibited last spring at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Presented by the Aperture Foundation and the photography program at the School of Art, Media, and Technology at Parsons The New School for Design.

November 28, 2012

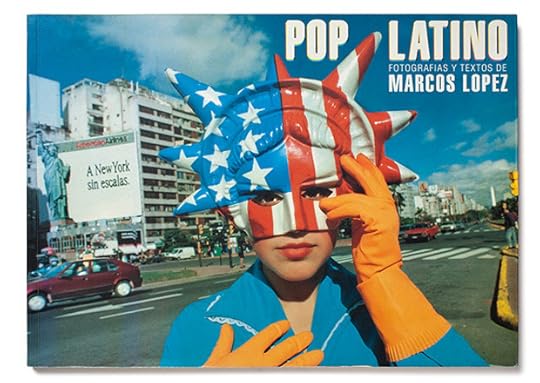

Latin American Photobook Exhibition & Saturday Symposium

“The Latin American Photobook: The best kept secret in the history of photography.” —Martin Parr

The Latin American Photobook presents a selection of volumes from the 1920s to the present, providing revelatory perspectives on the under-charted history of Latin American photography. Join us on Thursday evening for the opening reception of The Latin American Photobook exhibition, curated by Horatio Fernández, editor of The Latin American Photobook (Aperture, 2011), and again Saturday for a one-day symposium to accompany the exhibition, featuring a full day of discussion with photographers, curators, editors, professors, and publishers engaged with the Latin American photobook.

The exhibition, presented earlier in 2012 at Le Bal, Paris, and Ivorypress, Madrid, features work by great figures such as Claudia Andujar, Barbara Brändli, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Horacio Coppola, Paz Errázuriz, Graciela Iturbide, Sara Facio, Paolo Gasparini, Daniel González, Sergio Larraín, and many others.

The Latin American Photobook Opening Reception

Thursday, November 29, 6:00 pm

Aperture Gallery

New York

The Latin American Photobook Symposium

Saturday, December 1, 10:00 am–5:30 pm

Aperture Gallery

New York

FREE w/ RSVP

Related Press:

· The British Journal of Photography

· Wallpaper

The Latin American PhotobookPrice: $75.00

The Latin American PhotobookPrice: $75.00

November 21, 2012

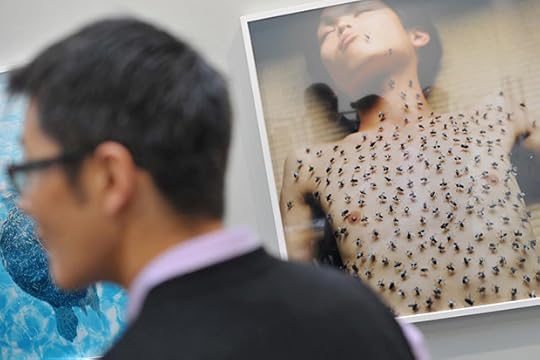

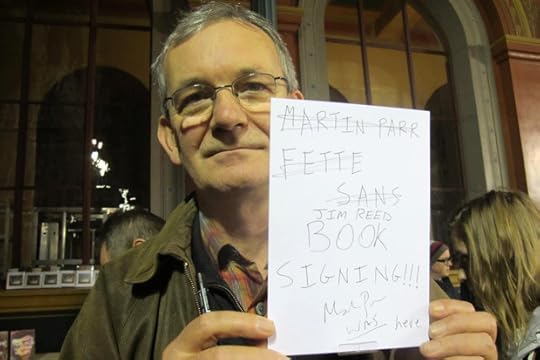

Paris Photo and Offprint Paris In Pictures

Last week, Aperture was at the photography fair Paris Photo, where, among many other things, the winners of the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards were announced. Take a look at photos from the week’s events at Paris’s Grand Palais, and at the neighboring art publishing fair Offprint Paris.

Also check out Paris Photo’s video round-up of the fair, our video previews of the shortlisted titles for the PhotoBook of the Year and First PhotoBook awards, and Instagram pictures from the week on our Facebook page.

Photos courtesy Christian Gapp, Paris Photo, and Lesley Martin.

November 20, 2012

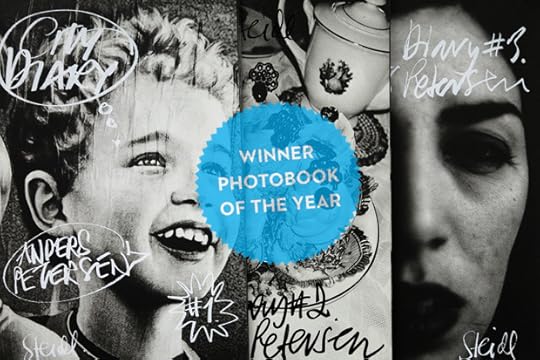

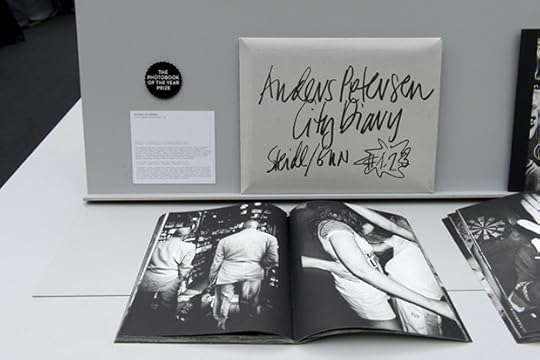

Anders Petersen – Finding a Fever

This conversation between Anders Petersen and J.H. Engström originally appeared in Aperture #198, the Spring 2010 issue of the magazine, as Petersen was editing the work that would become City Diary, the three-volume publication awarded PhotoBook of the Year during this year’s Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards.

One of Sweden’s most influential photographers, Anders Petersen has been producing bold and intimate black-and-white photographs since the late 1960s. His seminal book Café Lehmitz was published in 1978 and remains in print today. Shooting in a beer hall located in Hamburg’s red-light district over the course of three years, Petersen depicted in that project the drunken revelry of a rowdy cast of outsiders, and explored the boundary between ecstasy and desperation.

In the 1960s, Petersen studied with fellow Swede Christer Strömholm, famed for his highly personalized approach to photography. Like Strömholm, Petersen has not shied from engaging a wide spectrum of human experience in all its rawness, photographing in prisons, mental institutions, and a home for the elderly. The searing intimacy of his images is a testament to the amount of time—often years—he spends on each series. Petersen aptly describes his working process as “finding a fever: a kind of vibration between the people.” That fever, or psychological resonance, is one of the most compelling aspects of Petersen’s work.

Aperture recently asked photographer J.H. Engström, who once worked as Petersen’s assistant, to speak with him about the course of his career and his approach to the medium. The two recently completed the collaborative book project From Back Home, focusing on the Värmlands region of Sweden; the project was awarded the Contemporary Book Award at last year’s Recontres d’Arles. Petersen’s latest publication, the three-volume City Diary, was released last November by Steidl.

—The Editors

JH ENGSTRÖM: As I look at your new photographs, I’m thinking about the first book you did, Gröna Lund [1973]. What do you think connects these new photographs with the work in Gröna Lund?

ANDERS PETERSEN: The people. Meeting people, looking. New people. Always people. I like people.

JHE: But you have also said that there are too many people in the new book you’re working on now.

AP: Right now, in the process, there are too many people. If there are too many people I have difficulties finding a fever: a kind of vibration between the people. But if you connect the people to the landscape, to structures, to the sky, to water, to fire, then something starts to happen. Then you might have a fever.

JHE: The photographs in your books Gröna Lund, Café Lehmitz, and the three that followed were all made in single spaces, limited by four walls. But in your more recent work, such as Du Mich Auch [Same to you] and Close/Distance [both 2002], this isn’t the case.

AP: No, it’s not the case in my later work. I now photograph under freer circumstances. I don’t have that spatial limitation in my more recent work. If I were to stay within four walls, as I’ve done so often in the past, I would only repeat myself. I’m not attracted to such repetition.

JHE: Knowing your work and your photographs, I think on the one hand that there is a big difference now that you’ve left the four walls. But on the other hand maybe the difference isn’t that big. The biggest change, maybe, is that the limitation of the four walls is gone. Were the four walls a way for you to simplify your work?

AP: Of course, yes. It was easier that way: you had a consistent light, you had almost the same people coming every day. And if you build up a kind of communication with the people, it’s even easier. But after a while it’s also more difficult, because you do repeat yourself. I have played so much with different sets of four walls. I have to be freer now. No more limits—or rather, only my own limitations now.

But people do still interest me. I have two different ways of shooting. One is when I meet people; the encounter can go on for one hour or three days . . .

JHE: . . . like when you go home with someone, and stay there . . .

AP: Yes—and then you leave. And my other way of shooting is just snapshots. Cutting is a good word for it. I cut . . . that’s what it feels like, because it’s so fast. Then I peel away layers.

JHE: The first of your books that reached a wider international audience was Café Lehmitz. That book consisted of photographs taken in a beer hall in Hamburg, in the Reeperbahn neighborhood— Hamburg’s red-light district. You once told me that the process of doing those photographs “tattooed” you. What did you mean?

AP: There was the fantastic feeling of belonging to something—belonging to the people I was photographing, and to the mood, and to the atmosphere. You could sit there and feel absolutely alone. On the other hand, you were accepted as you were. And that was really a relief.

JHE: When I look at your photographs, and also when I make photographs myself, it makes me think: when does it all start, really? The photographs themselves don’t make the living more intense; it’s the act of photographing that makes life more intense. . . . People sometimes say that one can hide behind the camera. But I don’t agree. I think it’s the opposite.

AP: For me, it’s more intense to be with a camera than without. I talk more to people with a camera in my hand than I do without one. But all this is of course very individual.

JHE: After Café Lehmitz, you went back to Stockholm and started a trilogy that includes photographs from a prison, an old-people’s home, and a mental hospital. Those three books took you ten years to complete. Three years for each book, all done in very specific places. It’s a long journey. Was it your decision from the beginning to do this as a trilogy?

AP: No, not from the beginning. The decision to make a trilogy came to me after some time. The prison project, Fängelse [Prison; 1984], was a clear decision. I’m not interested in prison, really. I was interested in the feeling of being locked in. The feeling of it. It took a while for me to be accepted there. . . .

JHE: So the prison project was kind of a method to get closer to specific existential questions?

AP: That’s right.

JHE: What did you find out, being locked in?

AP: That there is no freedom. The word freedom and what it stands for is a bluff. The only way to relate to the word freedom is when you’re locked in: freedom is never bigger than when you’re locked in. But when you’re outside in the so-called free world, there is no freedom. So it’s all connected with longings. And that’s also true of photography, isn’t it?

JHE: I agree. To me, all your work has a very strong existential side. It’s not so much about describing your subjects. There’s more to the photographs than that.

AP: Yes, and this comes very much from the fact that I always keep going with what I’m photographing. I never stay for just three weeks and then go away. I stay for years. After a while things start happening, when you do that.

JHE: After the “issue of freedom,” you moved on to the “issue of death.” The second book in the trilogy is Rågång till Kärleken [On the line of love; 1991], with photographs made in an old-people’s home.

AP: Yes. That work made me feel very alive. To be close to death is a way to feel alive. A lot of people died while I was there—I think that twenty or twenty-five people died during my three years working on that project.

JHE: Did that scare you?

AP: Of course it scared me.

JHE: Did it scare you because you were starting to think about your own death? Or about how it is to get older?

AP: Not really. I was starting to think in more existential terms. I asked myself questions like who am I, and why, and what am I doing with my life? . . . One thing became obvious to me: you’re in a hurry—you’re not supposed to sit on a sofa, waiting around.

JHE: The clock is ticking.

AP: Absolutely. If you have visions, if you have a goal—then you’d better hurry up. It’s up to you. You make the choice to act; you can’t blame anyone else if you don’t. You think about this when you walk those corridors, when you sit down with these old people. What became very distinct and present for me were the dreams, the secrets, and the longings that these old people had. It was like coming home to a family of children. They were so innocent, so vulnerable.

JHE: Had they “let go” in some way?

AP: Yes. Maybe you could say that.

JHE: The third part of the trilogy, Ingen har sett allt [Nobody has seen it all; 1995], was made at a mental hospital. I was working with you then, as an assistant, and I remember you had a rough time.

AP: I know. You saw me collapse. Everything I did was very bad. I stayed away from the mental hospital for a while. Then I finally realized I had to do just the opposite: I had to live there, sleep there, together with the patients and the people working there. And they let me do that, because they had seen me there over quite a long period, and they saw how I was working—giving away photographs and so on—I always do that. Living and sleeping there changed my way of approach. I got closer. Because many things happen at night at the hospital. People communicate then; you can talk a lot with people. You see a lot of things. And of course, sometimes you can also take pictures. But many of the photographs I took there were censored, by the patients’ relatives and so on. When you take pictures in a mental hospital the result is always just the tip of the iceberg of the work you actually did there.

JHE: Often when I hear people talking about your photographs, I realize they don’t understand the amount of work you put in to them. And it’s not only the actual act of photographing. You are really with the people you’re photographing in these projects. For a long time.

AP: That’s totally right. Photography is not just about “photography.”

JHE: So how has all this work with people changed your way of thinking and feeling about your main interest: the human being?

AP: There is not a big difference between life and taking pictures. That’s my approach. The answer lies in that. But questions interest me more. You’re in the middle of life, you’re living, making love, eating, sleeping—and photography is part of it. And I don’t say this because I’m being romantic. I say this because that’s just the way it happens to be.

JHE: I sometimes say that I don’t go to places to photograph, I photograph because I am at places.

AP: Yes, but when you get older you have to focus. You have to really say to yourself: this life is interesting; these people are interesting. You have to stick around and see what’s happening. Sometimes you have to dominate the situation and really make clear that you are a photographer. This is a way to direct yourself. Pictures, like birds, never come to you; you have to move your ass to get them. You can’t just stand there and say: “Excuse me, I’m a photographer.” You have to be in it and be a part of it.

JHE: So, as you continue working, do you think this is what you will keep doing as long as you have the strength to lift the camera? Some photographers slow down when they get older. But you’re working even more now than you did ten or fifteen years ago.

AP: It’s like jumping on a trampoline . . . I have a lot of fun. I meet a lot of people. Actually, I would like to do even more.

JHE: I think that’s because you’re not thinking so much in terms of specific projects anymore. You live and you photograph at the same time—and suddenly you have this pile of contact sheets, and you didn’t see them coming, so to speak.

AP: This is true.

JHE: Every time I come down here to your lab I’m overwhelmed by the amount of production. The pictures lying around here are for your new book, coming out from Steidl.

AP: Yes, it’s called City Diary. But it’s not finished yet; there is still a lot to do. Always.

Aperture 198Price: $18.50short

Aperture 198Price: $18.50short

November 19, 2012

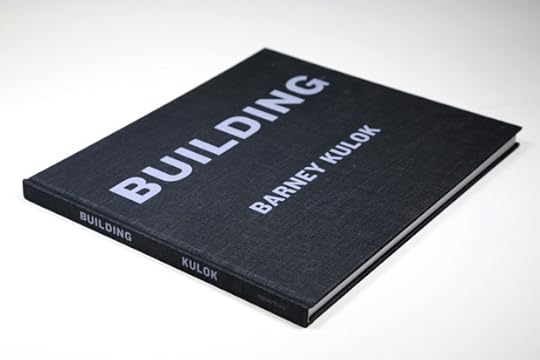

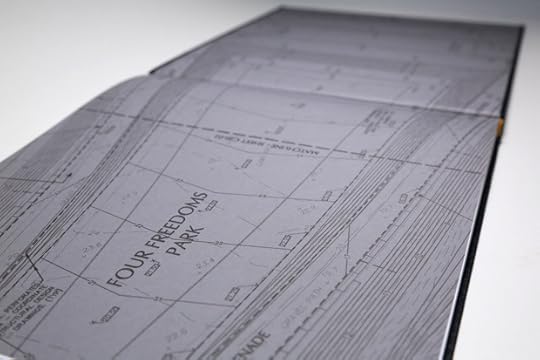

Barney Kulok – Building: Louis I. Kahn at Roosevelt Island – Now Available

Building: Louis I. Kahn at Roosevelt Island, a new photobook by Barney Kulok, is now available online.

In September 2011 Barney Kulok was granted special permission to create photographs at the construction site of Louis I. Kahnʼs Four Freedoms Park in New York, commissioned in 1970 as a memorial to Franklin D. Roosevelt. The last design Kahn completed before his untimely death in 1974, Four Freedoms Park became widely regarded as one of the great unbuilt masterpieces of twentieth-century architecture. Almost forty years after having been commissioned, it is finally being completed this year, as originally intended.

Kulokʼs black-and-white photographs function as a meditation on the materiality and formal underpinnings of Kahnʼs theories. As architect Steven Holl writes, “Kulokʼs photographs free the subject matter from a literal interpretation of the site. They stand as ʻEquivalentsʼ to the words about material, light, and shadow that Louis Kahn often spoke.”

14 x 11 inches

80 pages, 40 duotone images

Clothbound

978-1-59711-225-3

Fall 2012

Designed by And Smith, LLC

Essay by Steven Holl

Afterword by Nathaniel Kahn

Barney Kulok is a graduate of the Bard College photography program and is represented by Nicole Klagsburn Gallery, New York, and Galerie Hussenot, Paris. He lives and works in New York.

November 16, 2012

Holiday Sale Save 30-60% Off Books and 15-20% Off Prints*

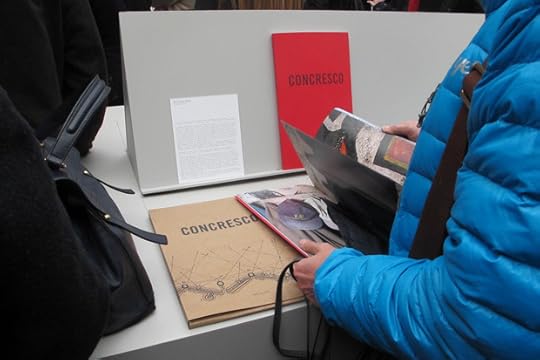

Announcing the Winners of The Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards

Paris, November 16, 2012—Paris Photo and Aperture Foundation are pleased to announce the winners of The Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards. City Diary (Volumes 1-3) by Anders Petersen (Steidl, 2012) has been selected as the PhotoBook of the Year, and Concresco by David Galjaard (Self-published, 2012) is the winner of $10,000 in the First PhotoBook category.

A jury in Paris, including Els Barents, director of the Huis Marseille Museum for Photography; Roxana Marcoci, curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and curator of the Paris Photo 2012 Platform; Britt Salvesen, curator and head of the Wallis Annenberg Department of Photography and the department of prints and drawings at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Thomas Seelig, curator and curator of collections at the Fotomuseum Winterthur, Winterthur, Switzerland; and Timothy Prus, curator of AMC Books, selected the winners for both prizes.

The thirty outstanding photobooks shortlisted for the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards 2012 are currently being exhibited at Paris Photo at the Grand Palais, after which they will be presented at Aperture Gallery in New York and other venues to be determined. The shortlist was first announced in The PhotoBook Review 003, Aperture’s biannual publication dedicated to the consideration of the photobook, and is also available at Paris Photo’s website.

The initial selection was made by Phillip Block, deputy director of programs and director of education at the International Center of Photography, New York; Chris Boot, executive director of Aperture Foundation; Julien Frydman, director of Paris Photo; Lesley A. Martin, publisher at Aperture Foundation; and James Wellford, senior international photo editor at Newsweek magazine.

In addition to the prize and the exhibitions of shortlisted books, Paris Photo at the Grand Palais is hosting the exhibition Livre ouvert, featuring prints by Bernd and Hilla Becher alongside the works from the exhibition Bernd & Hilla Becher-Printed Materials, 1964–2010. As always, the fair has dedicated a space to publishers and specialist booksellers presenting newly listed titles, old and rare books, and limited editions. Numerous signing sessions with photographers are organized during the five-day event.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers