Aperture's Blog, page 3

September 18, 2025

Inside the Bizarre Realm of AI Copyright Law

Spirits, monkeys, and Oscar Wilde form a strange trinity. Close your eyes and you might imagine some fin de siècle late night in a smoky room, where a blindfolded Wilde excitedly channels spirit voices. Maybe a leashed macaque looks on skeptically. Surely absinthe is being consumed. I’m guessing, however, that the US Copyright Office’s regulatory guidance on generative artificial intelligence did not find its way into your vision.

Yet somehow this triad forms the doctrinal basis for one of the most impactful and controversial sets of rules that body has promulgated in years: its guidance on how and when it will grant copyright registrations for works (including photographs) containing material generated by artificial intelligence. Wherever you might come out on that charged moral and policy question—the Copyright Office, incredibly, received more than ten thousand comments in response to its public inquiry in 2023—surprisingly little has been said of the strange, almost mystical legal precedents that the Copyright Office has relied on to develop its current position.

At its core, the question is one of authorship, and it is constitutional. The same foundational text that gave us the separation of powers allows Congress to grant intellectual property protection to “authors.” For almost one hundred and fifty years, the Supreme Court has interpreted that weighty term to limit copyright to works that “owe their origin” to the mental conceptions of a person as opposed to the mechanical reproductions of a machine.

Screenshot from Getty Images v. Stability AI complaint, 2024

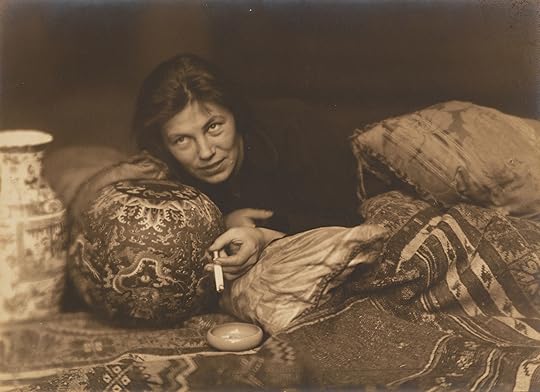

Screenshot from Getty Images v. Stability AI complaint, 2024In a leading early case from 1884, the photographer Napoleon Sarony succeeded in asserting copyright in his 1882 portrait of Oscar Wilde—but only because the photograph evidenced Sarony’s “intellectual invention.” Sarony had, according to the court, posed “Wilde in front of the camera, selecting and arranging the costume, draperies, and . . . arranging the subject so as to present graceful outlines, arranging and disposing the light and shade, suggesting and evoking the desired expression.” The court was clear, however, that this was no “ordinary” photograph, which in the usual case (without Sarony’s aesthetic sense behind it) might have remained a purely mechanical process meriting no copyright protection. Copyright, in other words, must come from the photographer and not the camera.

Despite the many decades that have passed since the obsolescence of the glass-plate negative, the case continues to speak to many of the core issues in the AI copyrightability debate. Is generative AI, like Sarony’s camera, simply a tool in the service of an artist’s skill and vision—a brush or burin for the 2020s—or is it, instead, the creator?

This leads us to the Copyright Office’s current legal test, shaped in no small part by Sarony’s precedent. When an applicant seeks to register a work containing some AI-generated material, the applicant must disclose which aspects were contributed by humans and which were not. The examiner will then decide whether the work is “basically one of human authorship, with the computer . . . merely being an assisting instrument, or whether the traditional elements of authorship in the work . . . were actually conceived and executed not by man but by a machine.’’ If the former, the Copyright Office will grant a copyright; if the latter, the work will be in the public domain for anyone to copy for any purpose.

When we call AI a black box, how different is that really from assigning agency to a spirit or the occult?

Sarony’s case is not the only precedent shaping this test. And that is where things start to get stranger. In justifying its current rules, the Copyright Office has also repeatedly pointed to a series of twentieth-century precedents involving claims over works created neither by man nor machine but by divine spirits. The leading citation here is Urantia Foundation v. Maaherra, an enigmatic case from the 1990s in which both the copyright claimant and the defendant agreed that The Urantia Book—a two-thousand-page religious text that emerged in the early twentieth century—had been written by “non-human spiritual beings” including “the Divine Counselor, the Chief of the Corps of Superuniverse Personalities, and the Chief of the Archangels of Nebadon.” Despite this spiritual baggage, the court recognized a valid copyright. While the teachings may have been divine, the court observed, a group of human interlocutors prompted the spirits to reveal those lessons and arranged the answers in a minimally creative way.

The Urantia court opinion pointed to a contrary holding from the 1940s in which the copyright claimant characterized himself as merely the amanuensis to whom a text was dictated by “Phylos, the Thibetan, a spirit.” That copyright assertion, unlike the one in Urantia, was rejected because the human scribe had claimed protection in the divine revelations themselves as opposed to any human arrangement of them. You can prompt the cosmos and remain a copyright author, it would seem, but straight transcription damns the work for all eternity.

David Slater, Monkey Selfie, 2011

David Slater, Monkey Selfie, 2011

© the artist and courtesy Caters Media Group

Better known than Urantia, but equally esoteric in its facts, is Naruto v. Slater, a litigation literally brought by a seven-year-old crested macaque against the wildlife photographer David Slater. Naruto the monkey, who had taken a few selfies with a camera left around by Slater, naturally took umbrage at seeing copies of his work reproduced without permission and saw fit (with a little help from People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) to sue Slater for copyright infringement. Suffice it to say, the monkey’s case was thrown out of federal court because copyright infringement remains a claim viable only to humans.

To be clear, these are not incidental, one-off citations by the Copyright Office. The government relied on Urantian revelations to support its position on AI-generated content in, for instance, its official statement of policy in its formal federal regulations, every one of its four published registration decisions in the AI section of its website, its official compendium of registration practices, its recent extended report on Copyright and AI, and its extensive appellate briefing on the leading case in this area, Thaler v. Perlmutter.

At this point, you may be wondering how exactly the Copyright Office is applying these extraordinary precedents to everyday copyright claims in the AI space. Take as an example the recent attempt by Ankit Sahni to register SURYAST (ca. 2021), a work that was essentially a mash-up of a source photograph taken by Sahni of a sunset with Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night (1889). Sahni inputted into an AI-powered tool known as RAGHAV a base image (his original sunset photograph), a style image (The Starry Night, which is in the public domain), and a value to determine the strength of the style transfer for the tool to use. RAGHAV then generated the final work without, we are told, further modification or input from Sahni.

The Copyright Office rejected the application. Despite the fact that the source photograph was taken by Sahni (and likely copyrightable on its own), it concluded that “the RAGHAV app, not Mr. Sahni, was responsible for determining how to interpolate the base and style images in accordance with the style transfer value. The fact that the Work contains sunset, clouds, and a building are the result of using an AI tool.” On what legal authority? It turned, naturally, to our cases on Oscar Wilde, the chief of the archangels of Nebadon, and a crested macaque.

Ankit Sahni, SURYAST, ca. 2021

Ankit Sahni, SURYAST, ca. 2021 Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889

Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889

© The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

What should we make of the fact that in setting critical policies for a truly paradigm-shifting technology, the Copyright Office is comparing generative artificial intelligence to a nineteenth-century albumen-silver print, revelatory channeling, and monkey selfies? Analogic legal reasoning, the core process by which common law develops through the selection and analysis of like precedents, inevitably involves some leaps. The rules governing digital music distribution were derived from cases on flea markets, the Sony Betamax, and the player piano before that.

We will naturally see this methodology at work soon as US courts start deciding the so-called ingestion photography cases (the negative, if you will, of the copyright registration authorship debate described above). Take, for instance, the photographer Jingna Zhang’s 2024 suit against Google, now consolidated into an even larger litigation, accusing the company of directly copying her photographs, without permission, for use in training Google’s Imagen text-to-image diffusion model. Or look to the recently refiled version of the case Getty Images v. Stability AI, in which Getty has accused Stability AI of not only copying twelve million Getty images to train its original Stable Diffusion model but allowing for the regeneration (in a somewhat grotesque form) of modified versions of those images as outputs.

Barring any settlement, both claims are likely to hinge on the fair use defense, with key precedents ranging from Lynn Goldsmith’s victory over the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts in 2023 to Google’s own successful assertion of fair use in defense of its Google Books initiative ten years ago. As we have seen in a handful of issued opinions this summer in AI cases involving the ingestion of books, these suits might turn on a simple choice between two metaphors: Is ingesting countless copyright-protected photographs into a dataset, and using that set to train Imagen or Stable Diffusion, more like the Warhol Foundation’s commercialization of unlicensed derivative illustrations to compete in the same market as Goldsmith’s original artist reference photograph (not fair use), or more like the volume scanning of every book ever to create a searchable corpus of the world’s literature (fair use)?

Still, there needs to be a core logic to any legal metaphor, particularly when the stakes are as high as they are: a technology poised to overtake so much creation. We can intuit why a court in these ingestion cases might compare the training of text-to-image AI software to either using a photograph without permission to create competing works or to the digitization of millions of books.

But the Copyright Office precedents on copyright authorship look to far more distant realms. Although the otherwise staid body would certainly deny it, there is something bordering on mystical in the government’s position. By relying on supernatural precedents, it is inherently assigning a spiritual ineffability to the AI-generative process. It is effectively stating that when photographers upload a source image to a generative AI program such as Midjourney, they are closer to animal or medium than artist.

Related Items

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]

What Is Realism in the Age of AI?

Learn More[image error]Not that this mysticism is necessarily unfounded. Almost every thoughtful account of generative artificial intelligence concedes, at a certain point, that its own developers really cannot explain or account for any given output from the tool. When we call AI a black box, how different is that really from assigning agency to a spirit or the occult? Aren’t we effectively attributing authorship to the ghost in the machine either way? The human is merely prompting the unknown in both cases, in every sense of that verb.

Andrew Ventimiglia, the author of an exemplary study of the Urantia cases, pushes the analogy even further, arguing that such precedents show how the physical objects of intellectual property—the hard-copy Urantia Book or Naruto’s, Sarony’s, or Sahni’s photographs—themselves “assert a kind of ghostly ontology.” That is, they are imbued by virtue of their litigation histories with the aura and spirit of law and the almost supernatural threat of copyright enforcement should one reproduce them.

However compelling these metaphysical analogies, though, copyright policy has real consequences on the ground. Whether and how we grant century-long monopolies in content has tangible stakes for countless people (including the many photographers reading this) and entire industries. It seems borderline absurd that we would build such monumental AI policy choices on a foundation of arcane precedents adjudicating the copyrightability of the aesthetics of Victorian photography, divine revelations, and the standing of monkeys.

I don’t mean to suggest that the Copyright Office has acted improperly here. That body is not empowered simply to create new rules out of whole cloth. It can only weave together the collection of opinions it has been handed by the federal courts, however crazy a quilt might result.

What this instead reveals is another limitation of the slow, rear-facing, and too-often nonrational development of our copyright doctrine. Confronted with a groundbreaking technology our copyright administrators are left divining old, mystic texts rather than asking straightforwardly what the best rule would be to incentivize some desirable outcome.

All that said, it remains fair to request, at the very least, that the Copyright Office shape its guidance on generative AI with a view more toward this world than the next.

A version of this article originally appeared in Aperture No. 257 “Image Worlds to Come: Photography & AI.”

Photographing the Night That Shook Seoul

In the midday sunlight of upstate New York, I had no way of knowing how cold the night of December 3, 2024, was in South Korea, how dark and long it had been. With a fourteen-hour time difference, martial law in South Korea felt incomprehensible to me, like seeing the future of my homeland. But for the Seoul-based photographer Yezoi Hwang, it was the present. The words martial law, heard while having dinner, communicated something she couldn’t believe without seeing with her own eyes. So she picked up her camera and went out into the square.

Hwang often uses her camera in an effort to understand the incomprehensible. After making series that focused on her family—capturing, for example, stories of conflict and reconciliation in Season (2016)—she gradually redirected her lens toward people on the margins, people who often bear invisible wounds. She developed a gaze of care, and as a result could see more clearly that she lived in a fragmented society masked by a fantasy of unity. Flashback Diary (2024–25) is Hwang’s documentary photography series of the protests from the moment former President Yoon Suk Yeoul declared martial law to his eventual impeachment.

Hwang witnessed: While men clashed with their bodies and raised their voices in combative protest, middle-aged women stood at the front lines to protect younger women. The uniforms of the police blocking the National Assembly and confronting the protesters failed to absorb light, reflecting it instead, turning them into ghosts. In contrast, hopeful handwritten notes, ribbons, and tiny, solidaristic snowmen became fixtures of the cityscape. So did the voices of countless women beyond the frame, through whom Hwang discovered what care truly means. And just like the lines in Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s 1982 novel Dictee that the artist continually returned to, it was “MAH-UHM,” the spirit: “It is burned into your ever-present memory. Memory less. Because it is not in the past. It cannot be. Not in the least of all pasts. It burns. Fire alight enflame.”

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Only seven years after the Korean War armistice, Koreans rose up in the April 19 Revolution of 1960, under martial law, to oppose the fraudulent election and dictatorship of the Syngman Rhee regime. In the October Restoration of 1972, former President Chung-hee Park imposed martial law to replace democracy with authoritarian rule in South Korea. In 1980, the Gwangju Uprising erupted in resistance to Doo-hwan Chun’s coup and the imposition of martial law, leading to mass killings. Martial law was present at every major political turning point in the country’s history. Because it granted “special measures” over freedom of the press, publication, assembly, and association, martial law was used as a tool for the government to wield coercive power over the basic rights of the people. It left indelible, inherited scars. A foreign journalist once said that democracy blooming in Korea is as unlikely as a rose sprouting from a trash can. Yet Koreans never hesitated to bleed red if it meant that rose might bloom. For more than sixty years, the people of Korea have protected that rose; the sudden reemergence of martial law was tantamount to its trampling.

To Hwang, the photographs in Flashback Diary are not a record of fear and violence. What she aimed to record with her camera was the strength of invisibles—those who built fortresses of warmth and hospitality against violence, and brought about a slow but democratic victory. The images act as a memoir of the artist as an autonomous woman engaging in dialogue with the social unrest surrounding her. As Hwang told me, “Photography becomes a tool that allows one individual to confront the multitude.” Her lens became a shield against a precarious world, and the resulting photographs became a fiercely burning “MAH–UHM” she carries, ever present.

All photographs Yezoi Hwang, Flashback Diary, 2024–25

All photographs Yezoi Hwang, Flashback Diary, 2024–25Courtesy the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 260, “The Seoul Issue.”

Photographing the Night that Shook Seoul

In the midday sunlight of upstate New York, I had no way of knowing how cold the night of December 3, 2024, was in South Korea, how dark and long it had been. With a fourteen-hour time difference, martial law in South Korea felt incomprehensible to me, like seeing the future of my homeland. But for the Seoul-based photographer Yezoi Hwang, it was the present. The words martial law, heard while having dinner, communicated something she couldn’t believe without seeing with her own eyes. So she picked up her camera and went out into the square.

Hwang often uses her camera in an effort to understand the incomprehensible. After making series that focused on her family—capturing, for example, stories of conflict and reconciliation in Season (2016)—she gradually redirected her lens toward people on the margins, people who often bear invisible wounds. She developed a gaze of care, and as a result could see more clearly that she lived in a fragmented society masked by a fantasy of unity. Flashback Diary (2024–25) is Hwang’s documentary photography series of the protests from the moment former President Yoon Suk Yeoul declared martial law to his eventual impeachment.

Hwang witnessed: While men clashed with their bodies and raised their voices in combative protest, middle-aged women stood at the front lines to protect younger women. The uniforms of the police blocking the National Assembly and confronting the protesters failed to absorb light, reflecting it instead, turning them into ghosts. In contrast, hopeful handwritten notes, ribbons, and tiny, solidaristic snowmen became fixtures of the cityscape. So did the voices of countless women beyond the frame, through whom Hwang discovered what care truly means. And just like the lines in Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s 1982 novel Dictee that the artist continually returned to, it was “MAH-UHM,” the spirit: “It is burned into your ever-present memory. Memory less. Because it is not in the past. It cannot be. Not in the least of all pasts. It burns. Fire alight enflame.”

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Only seven years after the Korean War armistice, Koreans rose up in the April 19 Revolution of 1960, under martial law, to oppose the fraudulent election and dictatorship of the Syngman Rhee regime. In the October Restoration of 1972, former President Chung-hee Park imposed martial law to replace democracy with authoritarian rule in South Korea. In 1980, the Gwangju Uprising erupted in resistance to Doo-hwan Chun’s coup and the imposition of martial law, leading to mass killings. Martial law was present at every major political turning point in the country’s history. Because it granted “special measures” over freedom of the press, publication, assembly, and association, martial law was used as a tool for the government to wield coercive power over the basic rights of the people. It left indelible, inherited scars. A foreign journalist once said that democracy blooming in Korea is as unlikely as a rose sprouting from a trash can. Yet Koreans never hesitated to bleed red if it meant that rose might bloom. For more than sixty years, the people of Korea have protected that rose; the sudden reemergence of martial law was tantamount to its trampling.

To Hwang, the photographs in Flashback Diary are not a record of fear and violence. What she aimed to record with her camera was the strength of invisibles—those who built fortresses of warmth and hospitality against violence, and brought about a slow but democratic victory. The images act as a memoir of the artist as an autonomous woman engaging in dialogue with the social unrest surrounding her. As Hwang told me, “Photography becomes a tool that allows one individual to confront the multitude.” Her lens became a shield against a precarious world, and the resulting photographs became a fiercely burning “MAH–UHM” she carries, ever present.

All photographs Yezoi Hwang, Flashback Diary, 2024–25

All photographs Yezoi Hwang, Flashback Diary, 2024–25Courtesy the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 260, “The Seoul Issue.”

September 11, 2025

Heinkuhn Oh’s People of the Twenty-First Century

Heinkuhn Oh rose to prominence with his photographs of social types—high school students, cosmetic girls, soldiers—often printed at gargantuan scale. Their faces greet visitors to Oh’s airy studio in southern Seoul. Uncanny, at times disarming expressions hint at the layered ambiguity present throughout his work. Although Oh’s portraits emerged from discrete series dedicated to groups, each subject’s eccentricities break through such categories, subtly dramatizing tensions between collective and personal identity in Korean society.

Oh’s early work was informed by his ambition to become a filmmaker and his years living and traveling in the United States. Equally influential was his experience growing up in Itaewon, a neighborhood in Seoul that was once a roiling tenderloin whose nightclubs and brothels catered to US soldiers. Today, it is one of the city’s trendiest neighborhoods, with bustling cafés, chic boutiques, and roaming influencers. Oh’s breakthrough series, Itaewon Story (1993), is a pregentrification tale, capturing the vivid underground characters who once defined the area. He has described Itaewon as a kind of in-between zone, a space “where people exist between cultures—neither fully one thing nor another.” It is a description that could be applied to Oh’s work as well, where his subjects often reside in liminal states: between the mainstream and the margins, childhood and adulthood, the individual and the collective, fiction and reality.

Heinkuhn Oh, Love Cupid Bar, on the Hill of Lucky Club, March 1993, from the series Itaewon Story

Heinkuhn Oh, Love Cupid Bar, on the Hill of Lucky Club, March 1993, from the series Itaewon Story  Heinkuhn Oh, Two Ajummas 1, March 26, 1997, from the series Ajumma

Heinkuhn Oh, Two Ajummas 1, March 26, 1997, from the series Ajumma Hyunjung Son: For readers new to your work, could you tell us about your background and what drew you to photography?

Heinkuhn Oh: Originally, my dream was to become a film director. I went to the United States to study filmmaking, but along the way, I fell in love with photography—more precisely, with documentary photography. I ended up going to graduate school and majoring in photography, but near the end, I still felt something was missing, so I added film as a second major. However, I ultimately received my final degree only in photography. I became so absorbed in my thesis project, Americans Them, that I didn’t have the time or energy to complete a film thesis. My mind was filled with the work of Garry Winogrand and Diane Arbus. Honestly, it was far more exciting to me than anything from Scorsese or Coppola.

From 1989 to 1991, I spent three crazy years traveling across cities in Ohio, West Virginia, and Illinois for Americans Them. Eventually, I made my way south to New Orleans. The camera I used back then was a fifty-year-old secondhand Speed Graphic, which I bought from a used-camera shop in Columbus. I attached a Metz flash to it and shot with 4-by-5-inch Type 55 Polaroid film. I felt like I had become Weegee. Initially, I used the camera’s range finder, but later, I started shooting everything by eye measurement. Although many shots came out of focus, not using the viewfinder made me look at my subjects with my naked eyes. It was a wonderful thing. These days, as I’m reprinting Americans Them, I realize just how much I learned about people and their gazes through that project.

Son: This word gaze comes up often when describing your work. You’ve said you discover, rather than create, these gazes.

Oh: In the late 1990s, I wanted to document the anxiety and social isolation experienced by middle-aged women in Korea, which was very much a country of ajeossi [middle-aged men]. This led me to photograph ajumma [middle-aged women]. Instead of taking the documentary approach I might have used earlier, I went directly to portraits. I had realized that if I could capture the narrative in their gazes and expressions, no further explanation was needed.

Creating a multilayered gaze artificially is impossible. These layers accumulate naturally through lived experience, visible in people’s expressions. The process of finding such gazes is time intensive. For my series Ajumma (1997), while the actual photography took less than two months, the casting period took over a year. I’ve done a lot of movie poster work as well, so I’ve sometimes been asked questions about the gaze of celebrities versus ordinary people. One question I received was, “What is the difference between the gaze of actors and that of ordinary people in your work?” With actors, I work to create layers in their gazes, while with ordinary people, I discover the layers already present in their expressions.

It was the same with my Cosmetic Girls (2005–8) project. From 2005 to 2007, I cast around five hundred heavily made-up teenage girls directly from the streets. Over the course of three years, I photographed one or two of them each day, and from those portraits, I looked for the gazes that carried the deepest layers of anxiety. This is because I believed that for these girls, makeup was an act of concealing their anxiety.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Son: Your use of the term casting is interesting, coming from your film background. How do you actually find and photograph your subjects?

Oh: My approach mirrors film casting because I believe great directors don’t so much direct actors as find the right people for each role. Once cast properly, actors naturally embody their characters. Similarly, I don’t try to create complex gazes—I find people who naturally possess them. My role then becomes creating the trust needed for them to reveal their authentic selves to the camera. That’s often the most challenging part.

Son: You’ve done a lot of commercial photography, including the movie posters you mentioned. How did you start this work?

Oh: In fact, all of my early black-and-white works are closely tied to my film background. Even Americans Them was fundamentally about capturing Americans as they appeared to be performing their lives as if in films—playing out cinematic storytelling or role-playing characters from movies. It seemed to me that they dressed, posed, and even joked as if they were in a film. It often reminded me of the movies by the Coen brothers. Itaewon Story was like an autobiographical film for me, capturing the images of celebrities I grew up watching in Itaewon during my childhood.

Heinkuhn Oh, A T-50A training jet with its pilot in the cockpit, July 2010, from the series Middlemen

Heinkuhn Oh, A T-50A training jet with its pilot in the cockpit, July 2010, from the series Middlemen  Heinkuhn Oh, Two honor guards wearing black formal dress, July 2010, from the series Middlemen

Heinkuhn Oh, Two honor guards wearing black formal dress, July 2010, from the series Middlemen Son: Your series Middlemen (2010–13) features military portraits, but I heard it was originally titled Absurd Play. Why did you change it?

Oh: In Korea, there is a mandatory system where most men serve in the military for a certain period. I, too, went to the military through this system when I was young, and after time passed, I came to look at that space again through photography. I completed my military service about thirty years ago. As a young man, my view of military service was straight-forward—it was about patriotism and duty. Returning to photograph the military in my fifties, everything appeared strange and awkward. The experience felt like watching an absurd play unfold, which inspired the original title. However, two months before the exhibition, our cultural liaison officer at the Ministry of National Defense privately expressed concern. The higher-ups had reacted negatively to the word absurd, interpreting it as suggesting something dysfunctional or improper. To protect our helpful liaison, I changed the title to Middlemen.

The work became subtitled Portraits of Young Korean Soldiers. During my two years observing these men, I recognized how they existed in a liminal state—neither fully civilian nor completely military. This realization led to the title Middlemen. It also sparked my broader interest in exploring these in-between states in society and, by extension, the nature of absurdity itself.

I don’t try to create complex gazes—I find people who naturally possess them.

Son: Would you share how you created works like the fighter pilot photographs?

Oh: For most of the photographs in my Middlemen project, the shooting process wasn’t particularly difficult. I didn’t try to capture or request any scenes that the military might find sensitive or uncomfortable. However, there was always a cultural liaison officer monitoring the images on a laptop connected to my camera—essentially conducting censorship. They said it was to prevent any accidental capture of military secrets, but I think they were really worried I might show something negative about the military. After a while, the officer even joked, “Why are you taking such boring pictures?”

But the fighter pilot shot was one that gave me a lot of trouble, even with this kindhearted liaison officer. The problem arose when I asked them to briefly halt a fighter jet during an operation. I thought they could simply stop it on the runway for a moment, not realizing that a fighter jet isn’t an automobile and costs tens of millions of dollars. Moreover, this was a military operational area, and stopping on the runway required approval from multiple levels of command. Eventually, the approval came through, and they did stop the jet, but the photography session took longer than expected. The officer kept pressuring me to hurry because the operation was ongoing, and the pilot was becoming increasingly irritated. What I found most interesting in this photograph, though, wasn’t the huge fighter jet or the pilot—it was the transparent canopy, stretching wide and open into the sky.

There was an incident that I couldn’t capture in a photograph, but even now, it remains with me like a trauma. During a shoot, I suddenly heard a sharp, piercing scream from behind me. When I quickly turned around, I saw something wrapped in a white cloth falling through the air. A soldier had jumped from an open window, from about the fifth floor of a building behind me. Tragically, I later heard that he had died. Military officials told me that the soldier had been suffering from severe depression, and that such incidents, while uncommon, did occur in the military.

Heinkuhn Oh, Four soldiers before a mock cavalry battle, May 2010, from the series Middlemen

Heinkuhn Oh, Four soldiers before a mock cavalry battle, May 2010, from the series MiddlemenSon: Your exhibition prints, including the Middlemen series, are often very large in scale. Why?

Oh: Starting with my Cosmetic Girls series, which I released in 2008, the scale of my work began to expand. There are two techniques in typological photography that can shift the subject toward abstraction: One is repetition, and the other is scale.

Cosmetic Girls was a portrait project that presented heavily made-up teenage girls in a format resembling a social report. The expressionless gazes of different girls were captured under identical lighting and with consistent framing, repeated again and again. At first, it may seem like each girl is being presented individually and concretely, but ultimately, through repetition, the images dissolve into abstraction.

I believe that when a photograph becomes excessively large, the subject itself begins to feel unfamiliar. This is one of the great ironies of large-scale photography. Especially in portraiture, the bigger the print, the more anonymous the subject becomes. I wanted the girls I photographed to appear anonymous and estranged. Because, for me, the series is ultimately about the underlying anxiety surrounding identity in Korean society that stems from feelings of anonymity, estrangement, disappearance, and abstraction.

In my more recent series, Left Face (2020–ongoing), the prints are also relatively large. But this time, the reason is slightly different. Lately, I’ve gotten interested in how large photographs create abstraction through their very obviousness. I think big photographs have this interesting thing where they switch between being clear and abstract. Having spent many years working in photography, I’ve started to feel that photography isn’t really about representation—it’s about abstraction, simply because it’s too obvious and straightforward.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Son: You’ve contrasted your philosophy with Henri Cartier-Bresson’s famous idea of the “decisive moment” by telling your students, “Don’t be decisive.”

Oh: Cartier-Bresson’s “decisive moment” refers to visual rather than conceptual decisiveness. However, I’ve come to believe that our contemporary world resists such clean distinctions. If photography reflects society, and society increasingly defies logical categorization, then perhaps photography should embrace this ambiguity. That’s why I tell my students, “Don’t be decisive.” Definitive statements and clear conclusions feel increasingly out of step with reality. When everything exists in shades of gray, why chase decisive moments? Even Cartier-Bresson often captured scenes that highlighted life’s fundamental absurdity.

Son: You have taught photography for many years. How has this shaped your thinking on image making?

Oh: Well, I’ve always tried to approach my students as an artist rather than as an educator. Observing the younger generation of photographers today, I feel they have highly developed visual sensibilities. But perhaps that’s only natural, as they consume so many more images than previous generations. During critique sessions, I often tell my students, “You are image addicts!” It’s as if they confuse reality and images. Today’s students look at reality and capture it as images, then look at images and discuss them as reality. While there’s nothing inherently wrong with this approach, I wish they could distinguish between the two.

Heinkuhn Oh, Huh jung, 20080428, 2022, from the series Left Face

Heinkuhn Oh, Huh jung, 20080428, 2022, from the series Left Face  Heinkuhn Oh, JU, 20160716, 2022, from the series Left Face

Heinkuhn Oh, JU, 20160716, 2022, from the series Left Face Son: Your early 1990s series Itaewon Story continues to resonate today. What makes it significant to you?

Oh: Itaewon has been my home since I was six years old. During my childhood in the ’60s and ’70s, Itaewon was dominated by the US Eighth Army presence and was known as a “camp town.” The alley near the fire station where my family lived was specifically designated as a “red-light district” under special administrative management. Because of that, there were lots of nightclubs and bars catering to American soldiers, and US goods smuggled out of the military base were everywhere. From an early age, I was exposed to drunken American GIs and Korean women working in the entertainment districts. I also got along well with waiters and waitresses who worked in the clubs and bars. Later, when I entered middle and high school and met friends who had more typical, ordinary childhoods, I realized that I had grown up in a very different environment. For a time, those early experiences became a kind of trauma for me, and a major source of insecurity. Itaewon Story explores these memories and the characters who populated them, including entertainers like Twist Kim and Shin Canaria, who were either familiar faces or local legends during my childhood.

Related Stories Portfolios Heinkuhn Oh’s Vivacious Portrait of Seoul in the 1990s

Portfolios Heinkuhn Oh’s Vivacious Portrait of Seoul in the 1990s Though the US Eighth Army has relocated, Itaewon remains a unique cultural space. The Seoul Central Mosque, situated at the neighborhood’s highest point, has drawn a significant Arab community, adding to the area’s diverse mix of residents. Yet calling Itaewon truly multicultural might be an overstatement. Different groups coexist physically but rarely truly integrate. This makes it a place where people exist between cultures—neither fully one thing nor another. It’s fitting that Itaewon sits geographically at Seoul’s center, embodying this in-betweenness. Sometimes I wonder if this fascination with in-between states is my destiny—the space between cultures, between definitions, between artistic forms.

Son: Photography seems to be gaining more recognition in Korea’s art world. What changes have you observed? And what concerns you as a photographer?

Oh: The landscape has definitely improved. More exhibition opportunities exist now, and major institutions increasingly embrace photography as contemporary art. We’re seeing more photography exhibitions in prestigious venues and more international exchange. However, I still maintain that there’s a distinction between photography within art and photography as its own medium. While this might seem like an outdated view in today’s cross-disciplinary art world, I believe photography maintains its own singular territory. We have plenty of discussions about photography in terms of aesthetics and social impact, but I miss deeper conversations about the fundamental elements that make photography unique as a medium.

Son: What directions are you exploring now? And what’s next for your work?

Oh: My immediate focus is completing Left Face, a project that has occupied the past five years. Its scope has grown beyond my initial expectations, and I’m still working to bring all the elements together.

I’m currently exploring the intersection of photography and text, but not in the usual documentary sense. I’m exploring how combining highly specific text with portraits can create a new kind of abstraction. I’m also planning to return to Itaewon for a new portrait series. The title is already decided—it’s Lucky Club. It will probably be work about various people living together in an old building in Itaewon. There, I need to find gazes that contain stories once again.

Son: Seoul is changing rapidly today. What’s your attitude toward the city’s development?

Oh: It’s absurd. This was a title I couldn’t use for the Middlemen project, but if I were to address Seoul as a subject, I would want to use it—a massive “absurd play” is unfolding here. Some describe Seoul’s transformation as diverse and dynamic, but I find it contextless and absurd. Yet photographically, I feel that’s what makes Seoul fascinating. Sometimes I find myself wondering if I should pick up my Speed Graphic again and head back out to the streets to shoot a documentary like Americans Them. I’ll need to think about whether it would become Koreans Them or Koreans We . . .

This interview originally appeared in Aperture No. 260, “The Seoul Issue.”

September 5, 2025

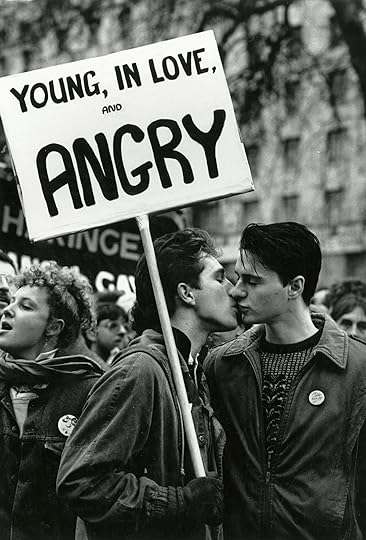

11 Exhibitions to See This Fall

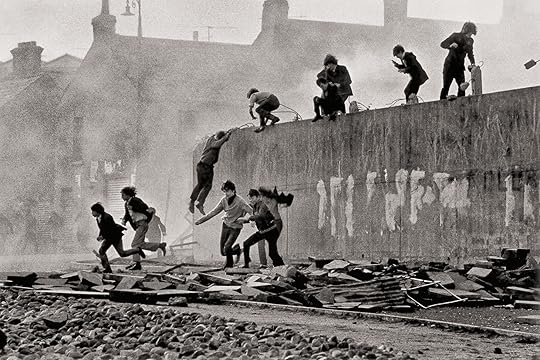

Don McCullin, Catholic youths escaping from CS gas, Londonderry, Northern Ireland, 1971

Don McCullin, Catholic youths escaping from CS gas, Londonderry, Northern Ireland, 1971Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Don McCullin – New York

A Desecrated Serenity charts seven decades of Don McCullin’s photojournalistic work across conflicts in Greece, Vietnam, Biafra, Bangladesh, Northern Ireland, and Beirut. The exhibition, his first New York show at Hauser and Wirth, presents his harrowing portraits and reportage from the front lines alongside cherished objects—like the Nikon F camera that once caught a stray bullet during battle. The exhibition moves from the stark landscapes of crime and poverty in postwar Britain; through unflinching records of global conflict; to images of vibrant cultural rituals in India, Indonesia, and the Sudan; to painterly meditations on the countrysides of France, Scotland, and Somerset, where McCullin sought solace late in his career.

Don McCullin: A Desecrated Serenity at Hauser & Wirth, through November 8, 2025.

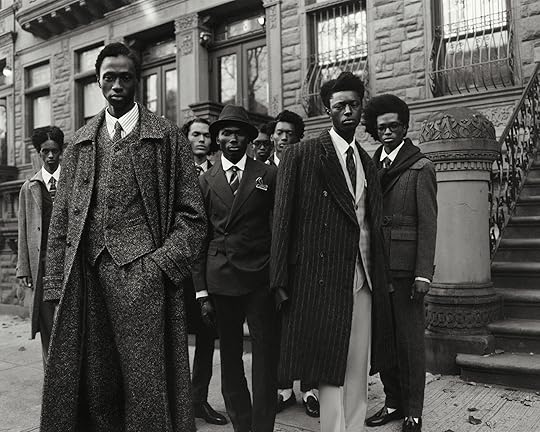

Tyler Mitchell, New Horizons II, 2022

Tyler Mitchell, New Horizons II, 2022© the artist and courtesy Gagosian

Tyler Mitchell – Paris

Growing up in a suburb of Atlanta, Georgia, Tyler Mitchell made skateboarding videos inspired by Spike Jonze and Ryan McGinley. After enrolling at New York University with plans to become a filmmaker, he began to make portraits full of energy, brash color, and sartorial panache, honing a signature look that landed him commissions for i-D and Vogue. This fall, Mitchell’s exhibition Wish This Was Real arrives in Paris after stops in Berlin, Helsinki, and Lausanne, Switzerland. Covering roughly a decade of image making, the show offers new perspectives on his abiding themes of masculinity, joy, and beauty. As the critic Salamishah Tillet writes in an accompanying monograph published by Aperture, “Mitchell’s work brilliantly reconceptualizes familiar spaces and teaches us that Black utopia has always been a place, constantly moving, unfolding, and being remade—like freedom.”

Tyler Mitchell: Wish This Was Real at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris, October 15, 2025–January 25, 2026

Katy Grannan, Damla, Mad River, CA, 2025

Katy Grannan, Damla, Mad River, CA, 2025© the artist and courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Katy Grannan – San Francisco

California’s Humboldt County is considered a place where people go to disappear. Katy Grannan first came to this bucolic backcountry in 2023 and began making portraits of people she found through Craigslist ads, flyers, and eventually word of mouth. Known for building long-term relationships with her subjects, Grannan conspired with those she photographed to create a kind of collaborative fiction, working both in the studio and in nature to thread together connections between site and self. Mad River unites these portraits for the first time, offering an intimate glimpse of the independent spirit of Humboldt County’s inhabitants.

Katy Grannan: Mad River at Fraenkel Gallery, New York, through October 25, 2025.

Tania Franco Klein, Mirrored Table, Person (Subject #14), from Subject Studies: Chapter 1, 2022

Tania Franco Klein, Mirrored Table, Person (Subject #14), from Subject Studies: Chapter 1, 2022Courtesy the artist

New Photography 2025: Lines of Belonging – New York

This year marks the fortieth anniversary of the Museum of Modern Art’s New Photography program of annual exhibitions that have, over the decades, brought then-emerging artists, including Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Rineke Dijkstra, and Lieko Shiga, to wider renown. MoMA’s latest edition considers themes of belonging as explored by a baker’s dozen of artists and collectives—hailing from Johannesburg, Kathmandu, New Orleans, and Mexico City—who weave personal stories with broader colonial histories. Gabrielle Goliath and Prasiit Sthapit are among the photographers, along with Sandra Blow—whose whose tender portraits of friends in Mexico City’s queer underground attest to photography’s community-making potential.

New Photography 2025: Lines of Belonging at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, September 14, 2025–January 17, 2026

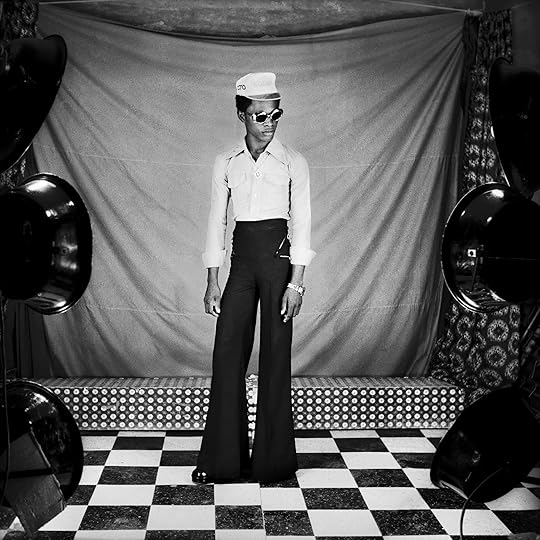

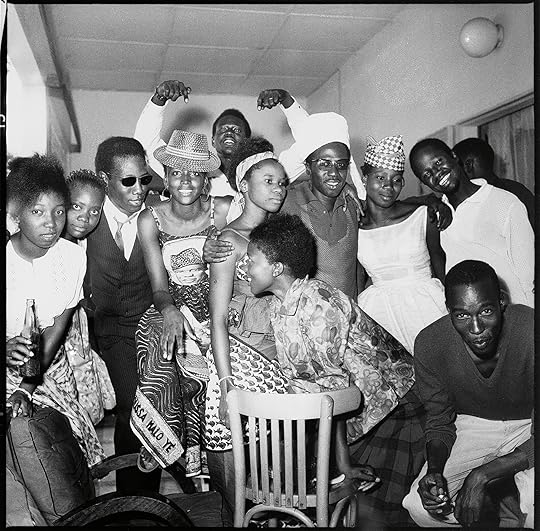

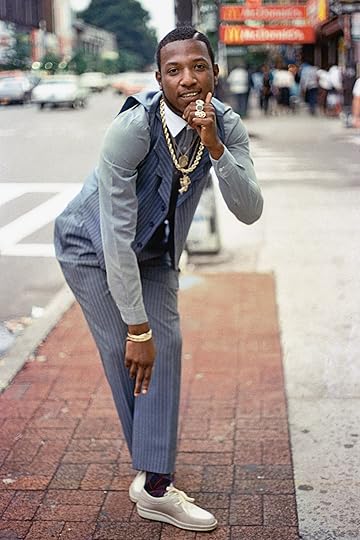

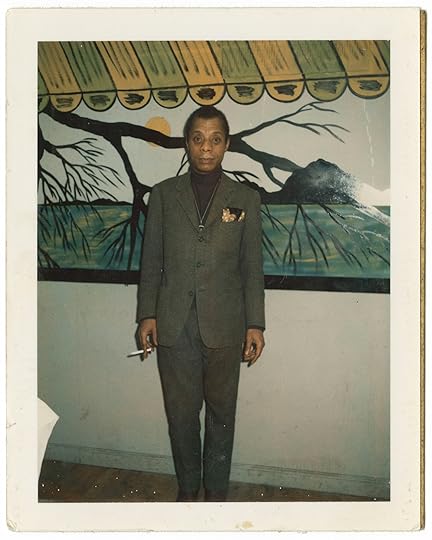

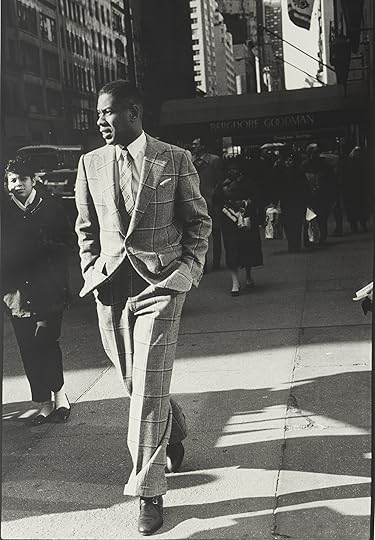

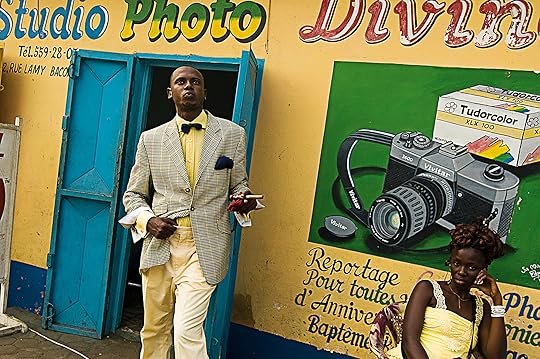

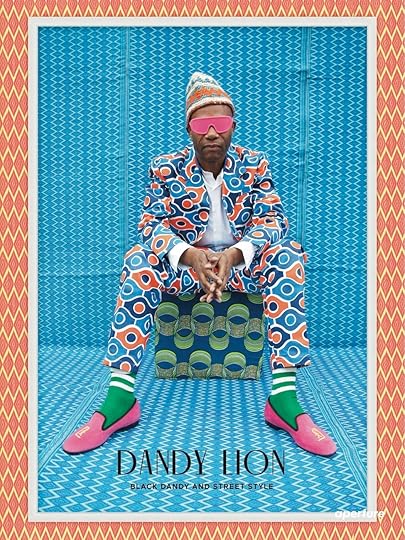

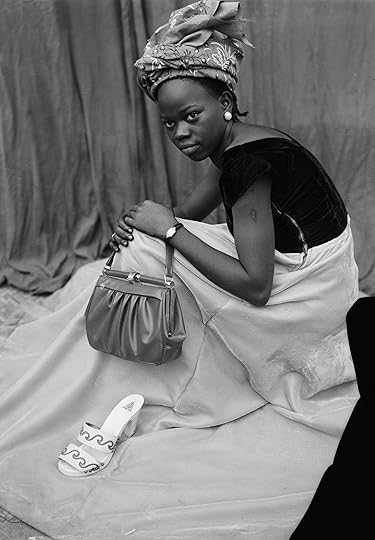

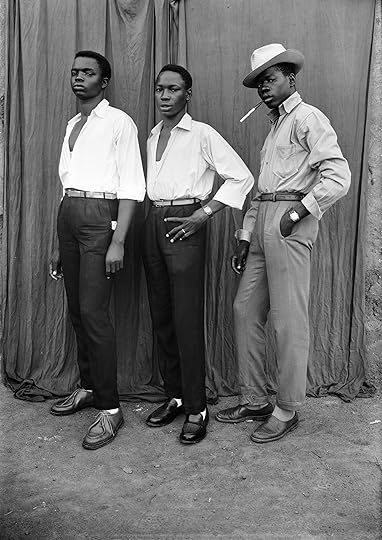

Samuel Fosso, Autoportrait, From the series 70’s Lifestyle, 1975–1978

Samuel Fosso, Autoportrait, From the series 70’s Lifestyle, 1975–1978© the artist and courtesy Yossi Milo, New York

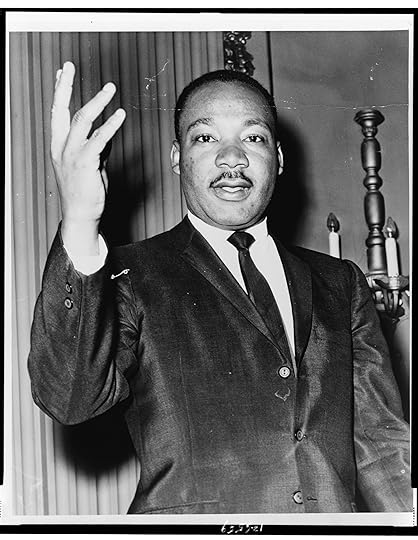

Samuel Fosso – New York

“I wanted to show how good I look,” Samuel Fosso once said of 70s Lifestyle (1975–78), a series he began as a teenager. Autoportrait, Fosso’s first solo exhibition in New York in two decades, certainly succeeds in this goal. The show celebrates the Cameroonian-Nigerian photographer’s self-portraiture, which calls upon and reinvents traditions of studio photography from West Africa and the African diaspora. In addition to 70s Lifestyle, which fuses the visual language of highlife culture with the bold attitude of young Black Americans as seen in magazines of the era, African Spirits (2008) features Fosso adopting the personae of such revolutionaries as Angela Davis, Patrice Lumumba, Martin Luther King Jr., and Nelson Mandela.

Samuel Fosso: Autoportrait at Yossi Milo, New York, through November 8, 2025.

Man Ray, Rayograph, 1922

Man Ray, Rayograph, 1922Courtesy The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles © Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY/ADAGP, Paris 2025

Man Ray – New York

“I have freed myself from the sticky medium of paint and am working directly with light itself,” declared a young American in Paris upon his invention of what he named, after himself, the “rayograph.” In 1921, Man Ray had discovered that, by placing everyday objects—such as scissors, keys, a wishbone, and a mousetrap—on photosensitive paper and exposing it to light, a new kind of photography was possible, one that dispensed with the camera entirely in its spectral, chance mash-ups, which quickly became the toast of Dadaist Paris. When Objects Dream includes some sixty rayographs, illuminating how the artist’s “crimes against chemistry and photography” (as he winkingly described them) informed the rest of his rebellious experimentation, which spans painting, cinema, drawing, and photography.

Man Ray: When Objects Dream at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, September 14 through February 1, 2026.

Kwame Brathwaite, Untitled (Jacksons on Boat from Goree Island), 1974

Kwame Brathwaite, Untitled (Jacksons on Boat from Goree Island), 1974© Kwame Brathwaite Estate

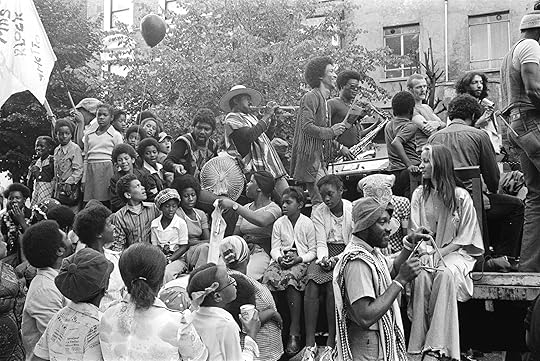

Black Photojournalism – Pittsburgh

At its height in the 1930s, the Pittsburgh Courier was read by hundreds of thousands of readers across the United States, one among many Black newspapers to report on the burgeoning civil rights movement and the struggles for equality and social justice. Newspapers such as the Courier, Atlanta Daily World, and The Chicago Defender take center stage in Black Photojournalism, an exhibition at the Carnegie Museum of Art focused on Black photographers who, from the post–World War II era through the 1980s, helped create the first draft of history. One searing image by Ming Smith, made in 1976, the year of the US bicentennial, points up the aspirations of the American Dream and its limitations: A man gazes outward in reflective sunglasses while the stripes of three flags appear like prison bars.

Black Photojournalism at the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, September 13, 2025–January 19, 2026

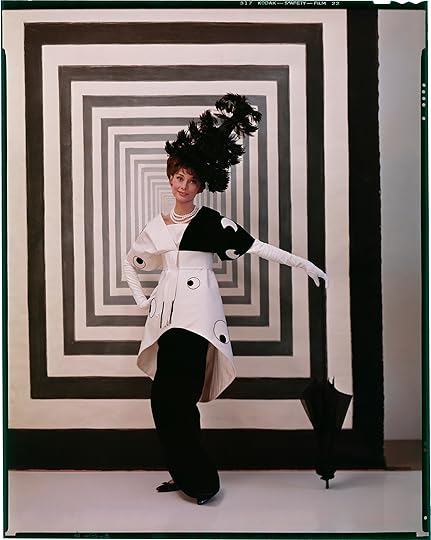

Cecil Beaton, Audrey Hepburn in costume for My Fair Lady, 1963

Cecil Beaton, Audrey Hepburn in costume for My Fair Lady, 1963Courtesy the Cecil Beaton Archive, London

Cecil Beaton – London

Renowned photographer, illustrator, costume designer, diarist, arriviste, and court photographer to the British royal family, Cecil Beaton is synonymous with glamour. Cecil Beaton: Fashionable World explores his groundbreaking society portraits, tracing an illustrious career from the Jazz Age of “Bright Young Things” to the glitterati of My Fair Lady (1956) and Gigi (1958). The show’s trove of photographs, costumes, and ephemera places the viewer into the mind’s eye of the acclaimed “King of Vogue,” whose stylized, highly theatrical portraits of a bygone beau monde once offered starry escapism during the interwar and early postwar era. As Beaton once said, “Be daring, be different, be impractical, be anything that will assert integrity of purpose and imaginative vision against the play-it-safers, the creatures of the commonplace, the slaves of the ordinary.”

Cecil Beaton: Fashionable World at the National Portrait Gallery, London, October 9 through January 11, 2026.

Ben Shahn, Liberation, 1945

Ben Shahn, Liberation, 1945© 2025 Estate of Ben Shahn/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Ben Shahn – New York

The painter Ben Shahn spent his career chronicling and confronting the social issues of his era—from censorship and authoritarianism to the labor movement and civil rights. Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity marks the first US retrospective of the artist’s work in nearly half a century, showcasing the enduring relevance of Shahn’s vision. A highlight includes a selection of photographs—both those taken by Shahn himself and by peers, such as those who worked for the Farm Security Administration—that served as his muse. “One of the main goals of this exhibition is to illuminate the under-appreciated complexity of his aesthetic, the multifaceted layered quality of his work, which is largely indebted to photography, both his own photographs and those of others,” notes curator and art historian Laura Katzman. “Photography was central to Shahn’s vision and his working process.”

Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity at The Jewish Museum, New York, through October 26, 2025.

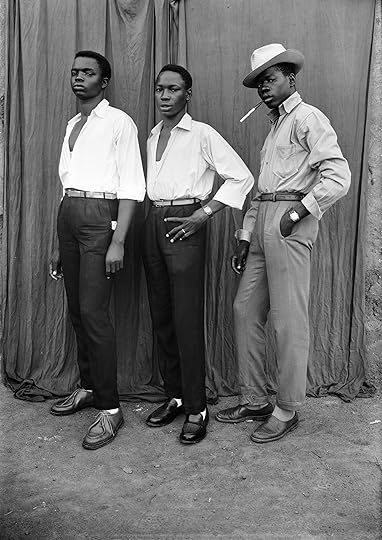

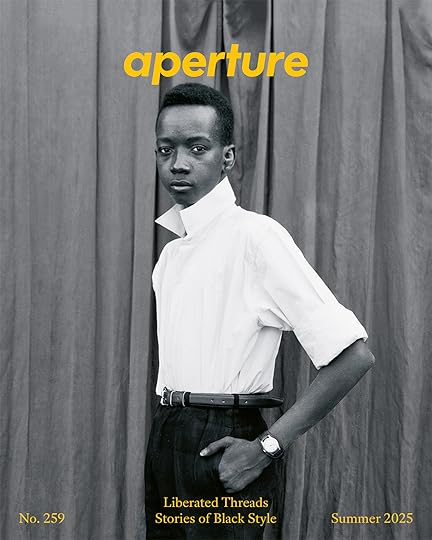

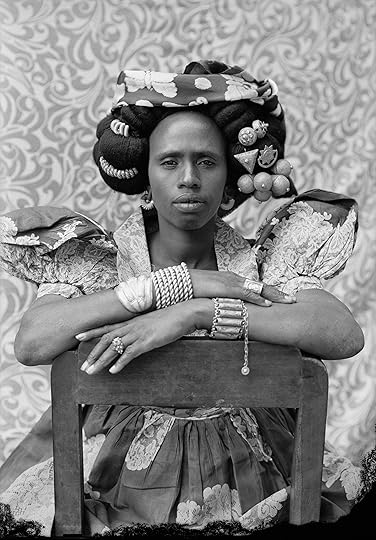

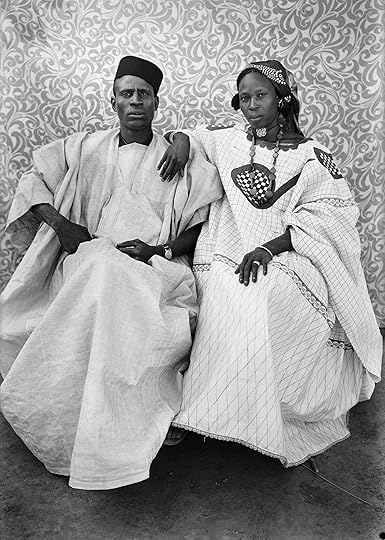

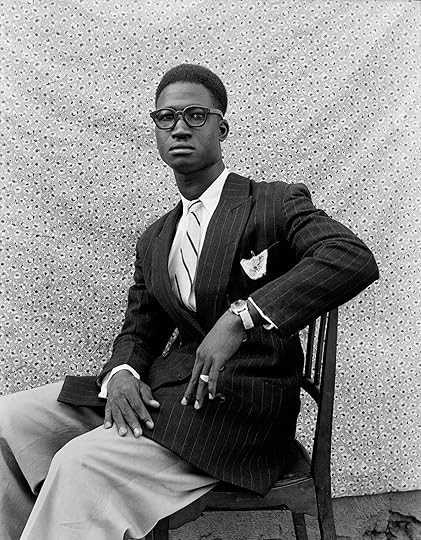

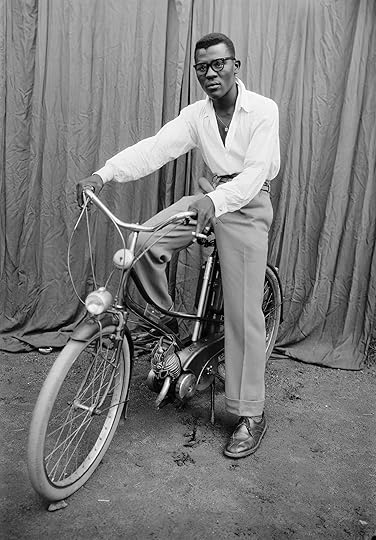

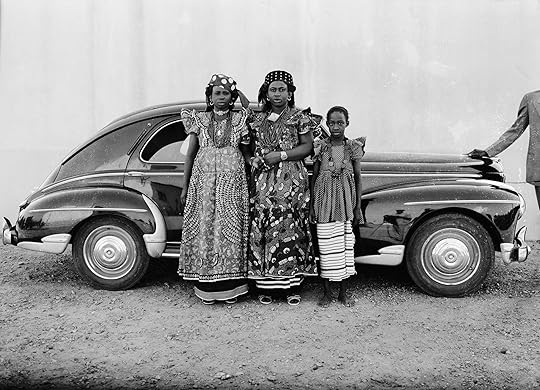

Seydou Keïta, Untitled, ca. 1952–55

Seydou Keïta, Untitled, ca. 1952–55© SKPEAC/the estate of Seydou Keïta and courtesy The Jean Pigozzi African Art Collection

Seydou Keïta – New York

Seydou Keïta captured the dignity and the dreams of the people who posed in his studio in midcentury Bamako, during Mali’s turn to independence. With his ingenious use of props and backdrops, the photographer struck an elegant balance between formality and intimacy, timelessness and urgency. As Kobby Ankomah Graham writes in Aperture’s Summer 2025 cover story, “Keïta’s subjects gaze directly into the camera and claim their place in history on their own terms.” A retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum celebrates Keïta’s own rightful place in history—as an all-time great whose name should be as well-known as that of August Sander, Irving Penn, or Richard Avedon.

Seydou Keïta: A Tactile Lens at Brooklyn Museum, New York, October 10 through March 8, 2026.

Hans Blaser, Portrait of Germaine Krull, Berlin, 1922

Hans Blaser, Portrait of Germaine Krull, Berlin, 1922 © Germaine Krull Estate, Museum Folkwang, Essen

Germaine Krull – Germany

Germaine Krull, the legendary modernist photographer, had many nicknames. One anarchist friend dubbed her the “Iron Valkyrie” for her interest in industrial forms, as seen in Métal (1928), a slight but epochal photobook whose tightly cropped, strange-making photographs of the Eiffel Tower and other steel structures launched her career in interwar Paris. She called herself chien fou—crazy dog—and this is the title of an exhibition opening at Museum Folkwang, the home of her estate since 1995. The show examines how Krull balanced her experimental vision with her role as a working photojournalist, drawing overdue attention to an oeuvre that spans reportage, writing, portraiture, and avant-garde photomontage across four continents.

Germaine Krull: Chien Fou at Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany, November 28, 2025–March 15, 2026

September 4, 2025

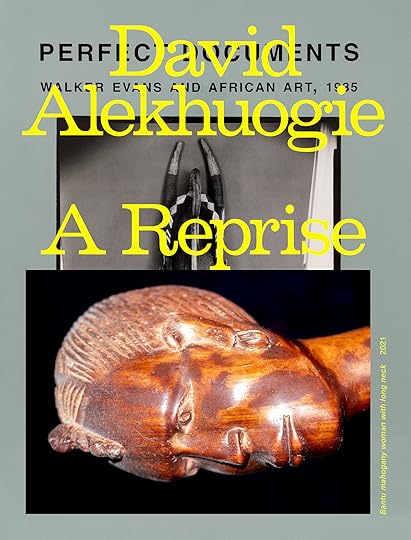

David Alekhuogie Sees Blackness at the Core of Modern Art

Look at the core of Western modernism. See the Blackness. See African aesthetics. Or, rather, see the ways that Western modernism claimed to know these aesthetics but failed to do so. See through a Black gaze instead.

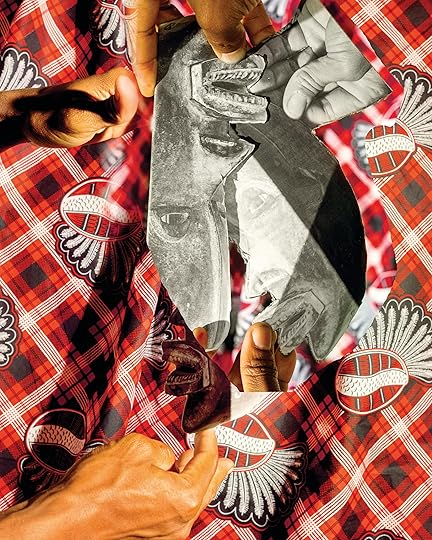

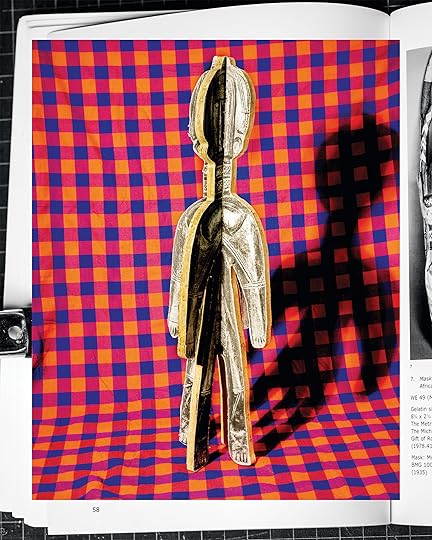

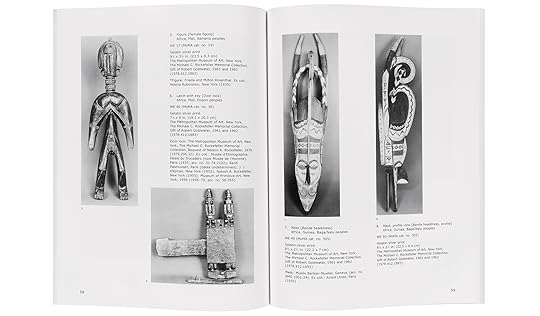

These are the invitations and redirections that animate David Alekhuogie’s project A Reprise (2019–ongoing). The series is anchored in a body of work by Walker Evans produced on the occasion of African Negro Art, a 1935 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, which showcased more than six hundred sculptures from the African continent—most of which had been pillaged to furnish American and European collections. Evans was commissioned to photograph selected sculptures; his images were subsequently published in seventeen portfolios—each with 477 photographs—which were circulated to institutions across the United States and used to teach African art history. Decades later, a selection of the photographs was republished in Perfect Documents (2000), a catalog for an exhibition of Evans’s photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

It was a Western lens that made Evans’s photographs possible. But in Alekhuogie’s Reprise, the West’s supposed claim to these sculptures—which was reiterated through both literal and photographic capture—is disrupted. Alekhuogie rephotographs Evans’s pictures and builds three-dimensional cutouts, turning photographed sculptures into sculpture-based photo collages. These are set against lively, brightly hued textiles and rephotographed again, sometimes with Alekhuogie’s hand in the frame.

The resulting assemblages, as Alekhuogie notes in this conversation, attest to a chain of transformations and cross-cultural translations between African aesthetics, Euro-American cultural modernism, and postcolonial critique. Here, having been metaphysically disassembled by the art-historical machinations that produce discrete and distantly beheld objects, the sculptures are reassembled by Alekhuogie. It’s as if they have regained the animacy and fullness of presence with which they were imbued prior to their expropriation and display for Western eyes.

David Alekhuogie, Pull_Up HillFigure, 2019

David Alekhuogie, Pull_Up HillFigure, 2019  David Alekhuogie, Pull_Up w,o,b 2, 2017

David Alekhuogie, Pull_Up w,o,b 2, 2017 Zoë Hopkins: David, before you were showing in galleries, you worked in fashion photography and commercial photography. I’m curious to know how that background informs this body of work, A Reprise. I’m looking at the fabrics in the backdrop and at the way the photographs are staged, and I’m reminded, of course, of the sartorial world and fashion editorials. I’m looking at the way things are staged and this kind of editorial language and wondering if you could give some hints of what aspects of your career rubbed off on this project.

David Alekhuogie: My relationship to photography really starts through music. The fashion photography, the editorial photography, came after working in music journalism. It’s interesting how Black musicians and artists have been able to formulate this language of the radical avant-garde. Even in pop culture, people have been able to thrive through using performance to circumvent things like ownership and cultural capital and being looked at. How do you deal with the task of being looked at or being watched, or having the expectations of your behavior mediated through what you’re supposed to do, not just as an artist but as a worker?

I wanted to make work from the perspective of an outsider, because I think that to grapple with broken, inherited cultural capital is to always be an outsider.

Sometime in grad school, I started thinking about modernism and the relationship to the working class. Things like domestic labor became really interesting to me: the history of quilt-making and cooking and various forms of domestic labor that felt specifically modernist. Whether it’s the history of modernist painting or architecture or design, there’s a tendency to look at the working class as part of a mechanistic structure. So, I became interested in the people in the background or the people in the periphery, post–Industrial Revolution. How people are existing in that space or affecting how we think about what it looks like, at least in America, dealing with whatever comes after Jim Crow, or right before. I wanted to find a language that didn’t seem as labored. One of the things I went through when I got to school is that I started to have a disdain for my language and how it didn’t feel like it was my own.

Hopkins: In terms of an artistic language?

Alekhuogie: Yeah. Not only that, but also how I showed up in the corporate world. How I showed up with my friends and family. How I behave when I get stopped by the police. If I was code-switching, I was doing it subconsciously, which made it worse. Anyway, I think of music, poetry, performance as places where I’ve been able to see Black writers, Black artists find space. There’s a sort of avant-garde language of Black aesthetics in taking pieces of things, like collage. I teach this class about what the remix is. I think those elements, at least, are the early things that are part of my practice.

Hopkins: I love your emphasis on the particular relationship that Blackness shares with fragmentation and remixing. What Fred Moten might call “the break”—or a kind of ruptured subjectivity that begins with slavery and reverberates in Black music—feels so important to the way that a reprise is figured or configured as an assemblage. Could you talk about some of the reading or ideas or research that was informing that project and its early phases? In what context did you actually learn about Walker Evans’s Perfect Documents and the MoMA show African Negro Art? What are the ideas and the more practical forms of knowledge that inform A Reprise?

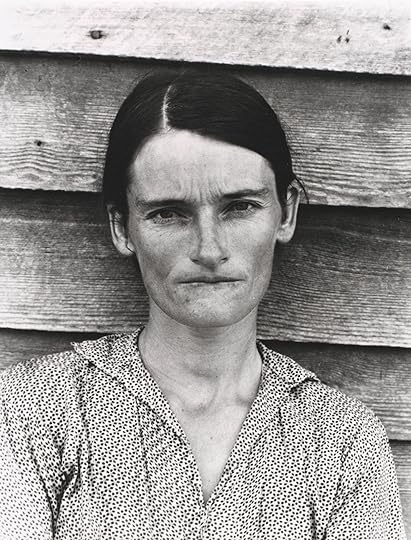

Alekhuogie: I became a student of documentary photography because I felt that was the work that could be the most meaningful for me and my community. I started taking interest in artists like Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Gordon Parks, and figuring out this relationship between being a working artist and a modernist artist. When you work in fields like photography, design, advertising, or illustration, you’re part of the service class—you’re providing a service. You learn to cultivate images through the client. In grad school, there was an anxiety about the point of view, which influences how people position documentary, and the desire to convince people—as if they need convincing—that straight photography is art. This kind of tension between the photographer who’s hired to provide a service and the artist who has a vision is how I became interested in Walker Evans’s work.

When I was eighteen or nineteen, I started working as a model. At the time, I was also working in fashion and music and all these different things. One of my good friends from high school was a dancer, and he was super interested in the entertainment industry. So, I had gotten into that world just by virtue of the friend group that I was around, and I started working with brands. For a while, I wanted to be a pro skater. I have multiple lives.

David Alekhuogie, Birth Home, 2013

David Alekhuogie, Birth Home, 2013  Sherrie Levine, After Walker Evans: 4, 1981

Sherrie Levine, After Walker Evans: 4, 1981© The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Courtesy Art Resource, NY

Hopkins: Yes, I can tell!

Alekhuogie: It’s all sort of revolved around this hip-hop lifestyle, which is very much an aesthetic now. But the Walker Evans stuff came really hard in graduate school. It was actually Sherrie Levine’s work that I had seen, where she was using the Walker Evans images as her own images, and this interesting commentary on authorship.

Hopkins: Right, she rephotographs pictures from Evans—and others like Edward Weston and Eliot Porter—straight from their catalogs and then claims authorship over the rephotographed images. And it’s been controversial, of course, because it’s quite easy to say she’s just copying these earlier modernist photographers. It’s the same gesture that Richard Prince is making.

Alekhuogie: Yeah. Just how ridiculous it is, it’s front and center. That’s how I became aware of the work. But at the same time, I had been working as a photographer. I had done people’s graduation pictures and baby pictures and engagement pictures and was doing skate photography. So, I knew what it was like for a person to hit your line and be like, “Could you do this thing?” You know what I mean? That’s what happened to Walker Evans, I’m very much convinced. It turned into this, Oh, now you’re this person who is tasked with doing this job but also with this responsibility for representing modernist photography. So there’s these two things happening at the same time.

David Alekhuogie: A Reprise 65.00 In A Reprise, David Alekhuogie remixes Walker Evans’s photographs of African art, provoking timely questions about authorship and authenticity.

David Alekhuogie: A Reprise 65.00 In A Reprise, David Alekhuogie remixes Walker Evans’s photographs of African art, provoking timely questions about authorship and authenticity. $65.0011Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

David Alekhuogie: A ReprisePhotographs by David Alekhuogie. Text by Wills Glasspiegel and Wendy A. Grossman. Interviewer Zoë Hopkins.

$ 65.00 –1+$65.0011Add to cart

View cart DescriptionIn A Reprise, David Alekhuogie remixes Walker Evans’s photographs of African art, provoking timely questions about authorship and authenticity.

A Reprise, David Alekhuogie’s first monograph, confronts the intriguing legacy of narrative and authorship behind Western presentations of African art, and poses timely questions about how Black aesthetics are circulated, accessed, valued, and interpreted today. In 1935, Walker Evans was commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, to photograph hundreds of African sculptures for the exhibition African Negro Art. Nearly ninety years later, Alekhuogie began investigating Evans’s images, provocatively remixing them into his own vibrant and multilayered photographic collages. Transposing facsimiles of Evans’s original images onto cardboard or paper structures of his own making, Alekhuogie rephotographs these image-sculptures against striking backdrops—often using East and West African textiles—thereby inviting multiple dimensions of viewership. Alekhuogie’s images draw upon the musical idiom of the reprise—a performance of repetition—and stake a claim to crucial, restorative ideas around Black antiquity by questioning our relationship to what we consider fake or original, art or archive.

DetailsFormat: Hardback

Number of pages: 156

Number of images: 110

Publication date: 2025-08-12

Measurements: 8.58 x 11.1 x 1.75 inches

ISBN: 9781597115742

David Alekhuogie (born in Los Angeles, 1986) is a documentary photographer. He received his MFA from Yale University and BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His work was included in Companion Pieces, the 2020 iteration of the Museum of Modern Art’s biennial New Photography series, and was presented in Men of Change: Power. Triumph. Truth. at the California African American Museum in Los Angeles. In 2019, he was the recipient of the Rema Hort Mann Foundation’s Emerging Artist Grant. Alekhuogie has had solo exhibitions at Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery; Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles; Skibum MacArthur, Los Angeles; and the Chicago Artist Coalition, and has participated in group shows at the Museum of Modern Art, New York; High Museum of Art, Atlanta; Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco; and Regen Projects, Los Angeles. His work has been published in Aperture, Foam, the New Yorker, the New York Times, Time magazine, Vice, and the Los Angeles Times. He is based in Los Angeles.

Wills Glasspiegel is a filmmaker, artist, and organizer from Chicago. He works with the Era Footwork Crew and codirects the nonprofit Open the Circle. He has directed a range of short films, including Footnotes (2021), Icy Lake (2014), Meet the Era (2016), and Bangin’ on King Drive (2015). He holds a PhD in American studies and African American studies from Yale University.

Wendy A. Grossman is an art and photography historian, writer, educator, and curator based in the Washington, DC, area.

Zoë Hopkins is a writer and critic based in New York. She received her BA in art history and African American studies from Harvard University and her MA in modern and contemporary art at Columbia University. Her writing has been published in Artforum, the Brooklyn Rail, Cultured, and Hyperallergic.

Related Content Interviews How David Alekhuogie Navigates the Colonial Past

Interviews How David Alekhuogie Navigates the Colonial Past Hopkins: And also making a living and finding work.

Alekhuogie: Right, yes. That was familiar to me. Also being in graduate school, really struggling with the expectations that I have put on myself as far as my own language and its authenticity. This is another thing that I have a little bit of disdain for, this fixation on Black authenticity from a spectator’s point of view. This is what makes hip-hop special, the realness. You’ve always got to be giving realness. So even if you’re talking in your true voice, you’re writing in your true voice, it comes from a very specific place.

One whole side of my family is pretty heavily gang-related. On the other side, I have gone to primarily private schools almost my entire life. So that causes a really strange dissonance. People don’t understand that the Black experience is not like The Wire. So, that was a serious reckoning in grad school; viewers didn’t have a reference point for the fact that Black interior life is very broad. For example, someone on my critique panel once said that they wouldn’t know I was Black from my images, but those were some of my most diaristic images. There was a need for certain things to point toward authenticity; there was an expectation to perform my Blackness in a way that was convincing. I took this as an opportunity to be a kind of heart-on-your-sleeve, very almost anti-intellectual kind of artist who was, like, “I’m just going to talk about me and my life and my experience.” I was coming to terms with the fact that that did feel like it quenched an appetite people have for looking at a thing that is not their own.

David Alekhuogie, Rene, 2024

David Alekhuogie, Rene, 2024  David Alekhuogie, Scramble for Africa pt. 3/3, 2024

David Alekhuogie, Scramble for Africa pt. 3/3, 2024 Hopkins: Which is exactly the appetite Walker Evans was commissioned to feed: he was photographing these African artworks that had been alienated so thoroughly from their natal context so that they could then be redirected toward an American audience, toward a MoMA audience. Some of the published portfolios were distributed to HBCUs in the US, which is so fascinating to me. It’s like the curators of the MoMA show were maybe trying to wipe their hands clean of the colonial context of the exhibition—the pillage and plunder that made it possible—by making a philanthropic gesture toward African Americans. It also suggests their interest in the relationship between African American culture and continental African culture, or in translating one to another. So, in some ways, the Evans photographs are translational documents. And then your sort of reiteration of his photographs is perhaps a metatranslation or a metatext that overlays that original translation.

Alekhuogie: Yes. Definitely. That’s definitely how I think of it. For a while, I have been interested in web-search criteria for what would qualify as African aesthetics or Black aesthetics, and seeing these images pop up, and being motivated by this idea that if this is a kind of cultural capital that people feel they’ve inherited or essentially feel kinship to, then it is going to be seen through this obtuse angle. It’s not going to be direct. I had started noticing: What does my domestic space look like? My dad is Nigerian. My mom is African American by way of Alabama; she eventually moved to Los Angeles in the 1960s, and she was the first in her family to go to college during this “Black Is Beautiful” movement. In her own self-presentation, she’s invested in the beginnings of what Afrocentrism looks like. So, I’m trying to parse how she’s seeking access to her own cultural capital.

That was my primary motivation—the idea of access to “authenticity” through all of these different channels. I exist on this really strange edge, where I feel simultaneously inside and outside. I’m in a perfect world, right? Somebody might hit my email and be, Hey, do you want to do a project with the museum of whatever to photograph these things, and do a whole show? When I was in my second year at Yale, I met Fred Wilson at a dinner. I became interested in his work, in its sort of interrogation of the institution.

Fred Wilson, Picasso/Whose Rules?, 1991

Fred Wilson, Picasso/Whose Rules?, 1991© the artist. Photograph © Ellen Labenski and courtesy Pace Gallery

Fred Wilson, Guarded View, 1991

Fred Wilson, Guarded View, 1991© the artist and courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art/SCALA

Hopkins: One of Wilson’s works is called Picasso/Whose Rules? (1991). He made a facsimile of Demoiselles d’Avignon and foisted a West African mask on the painting as if to not only call attention to the origins of Cubism, and the appropriative gestures that made that painting possible, but also to overlay and animate a postcolonial critique on its surface. He’s perhaps best known as an institutional-critique artist, but he’s also thinking about art history, about the place, or no-place, that African objects are afforded in Western institutions and the attendant discourse of Western art history.

Alekhuogie: What I find the most interesting is his work about being a security guard—Guarded View (1991).

Hopkins: Yes, that installation with headless Black mannequins wearing guard uniforms from the Whitney, the Jewish Museum, MoMA, and the Met.

Alekhuogie: That sort of approach is very different from how I see the world. I’m always thinking about the archive—books, texts, records, things that I can come to terms with after the fact. Because I’ve been a DJ since I was maybe sixteen or so. That is kind of my baseline for how I think through everything, really; that’s where all this stuff stems from. I’ve also been interested in how the DJ has changed, what the job is, what the task is. Is it your responsibility to represent whatever the zeitgeist is? Is it your responsibility to make people feel familiar? There’s a special moment as a DJ that happens when people in the room feel they’ve been seen, they’ve been recognized. That is what it means to rock a party—making people feel validated and seen.

For me, it all comes down to this stuff that everybody has access to. I wanted to make work from the perspective of an outsider, because I think that to grapple with broken, inherited cultural capital is to always be an outsider. That’s a part of the premise. I’m at my parents’ house now, and there’s tons of African sculpture. There’s always this negotiation around what’s real and what’s not, what’s vintage, what’s valuable—and that’s why I’m always interested in reproductions.

David Alekhuogie, Female Figure “A Reprise,” 2020

David Alekhuogie, Female Figure “A Reprise,” 2020  David Alekhuogie, Heddle Pulley 1/1 Speculative View, 2024

David Alekhuogie, Heddle Pulley 1/1 Speculative View, 2024 Hopkins: We also see that whole question of authenticity and value surface in Western discourses on African art that place a premium on the oldest, most traditional, most “authentic” African artworks. But what’s behind that is a colonial understanding of Africa as purely historical, as unable to participate in some telos of progress toward modernity, as a place without historical development at all, in Hegel’s famous assessment. So, when you have these old objects with patina accumulated over the centuries, the West exalts them as “the most” African, and whatever comes after is often seen as sort of secondary by virtue of its newness.

In A Reprise, you rebut this view by recontextualizing Evans’s black-and-white photographs and setting them against those bright fabrics, which are buzzing with vitality and freshness. Of course, we also get flashes of your subjectivity—your aliveness—with the hands that often appear in the frames. Could you talk about the staging? What kind of atmosphere or environment were you trying to conjure up in these images, and what kind of critique does it make?

Alekhuogie: I started to think about the studio as a performative space, the idea that the photographs were about this interrogation of looking at the original subject matter and trying to imagine what it coul be like in real life, but in an abstract way or in an imaginative way. And also, what it would mean if I took something as my own—and what the implications of that would be like. That’s when I became interested in the original fake. And that came from my trip to Nigeria in 2019, and seeing how people dealt with the value attached to branding. The value attached to knowing for sure that a thing was authentic. “Oh, you like this Prada shirt? I got you. Let me just sew that up for you. I made it. It’s real. What do you mean?” There was a kind of vitality. It wasn’t really about the brand so much as it was using that as a subversive force. If I make a Dutch wax-resist print with the Balenciaga logo all over it, then it circumvents or reappropriates the value associated with that brand. But that is a new thing altogether. I started thinking about that as an economic strategy. If I use material that is loaded in this way, then I can traffic with a kind of discursive strategy.

David Alekhuogie, NP16, O, 2015

David Alekhuogie, NP16, O, 2015  Constantin Brâncusi, Vue de l’atelier, 1927

Constantin Brâncusi, Vue de l’atelier, 1927© Brâncusi Estate and courtesy Peder Lund

Hopkins: There are two markers of authenticity that are being indexed and contested in your images. The first is the sculptures themselves, and the second is the Walker Evans images of the sculptures. There’s the original context of the sculptures, and then there’s the context of their entrance into the realm of the “Western art museum” or into the Western idea of art. You make an intriguing intervention of almost inserting the photographed sculptures back into a three-dimensional language: in your images, Evans’s photographs are pasted onto these wooden cutouts that give them the appearance of being three-dimensional. They’re like sculptures again, casting shadows on the backdrop. They also evoke the appearance of an almost Cubist assemblage, which again reminds us of the way Cubism latched onto a notion of African authenticity. Can you talk about that toggling between two- and three-dimensionality and what that does to these questions around authenticity and deracination?