Aperture's Blog, page 8

May 9, 2025

Consuelo Kanaga’s Restless Eye

Over six decades, Consuelo Kanaga, born in 1894, forged a career defined by an avant-garde, collaborative spirit and a photographic practice tied to social justice. In her home cities of San Francisco and New York, she was at the heart of close-knit circles of artists and writers, namely the California Camera Club, Group f.64, and The Photo League. She was an ardent documentarian of the Worker-Photography and New Negro movements of the 1920s and ’30s and the civil rights movement two decades later. It’s therefore confounding that in the years since her death, in 1978, Kanaga’s name and legacy, compared to those of her celebrated friends and contemporaries—Alfred Stieglitz, Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, Tina Modotti, and Louise Dahl-Wolfe—have fallen into obscurity.

Consuelo Kanaga, Clapboard Schoolhouse, ca. 1935

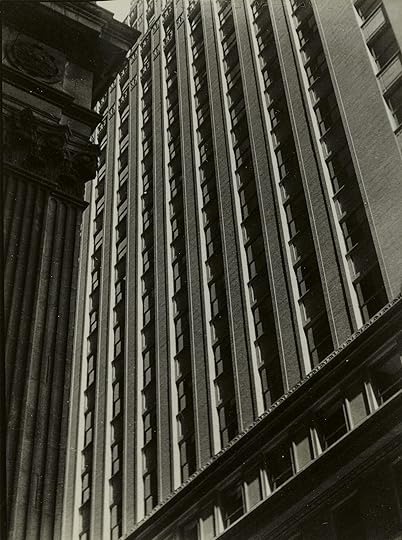

Consuelo Kanaga, Clapboard Schoolhouse, ca. 1935  Consuelo Kanaga, Untitled (New York), ca. 1940

Consuelo Kanaga, Untitled (New York), ca. 1940 A retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum, Consuelo Kanaga: Catch the Spirit, endeavors to introduce the photographer to a new generation and reestablish her place in the canon of modern American art history. Organized by Drew Sawyer, a curator of photography at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the exhibition first appeared at the Fundación MAPFRE in Barcelona and Madrid, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. With organizational support from Pauline Vermare, the show concludes its run at the Brooklyn Museum, the institutional home to some five hundred prints by the artist as well as many more negatives. Catch the Spirit generally follows the chronology of Kanaga’s life and career, but Sawyer groups the nearly two hundred photographs and contextual pieces of ephemera by style and subject, so that the viewer can sense the artist’s creative restlessness, exceptional versatility, and recurring preoccupations.

Kanaga’s practice began when she was working as a young reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle, an unconventional profession for women in the 1920s, and she discovered a penchant for directing the photographs that accompanied her articles. Encouraged by her editor, she began hauling the large-format view cameras of the day out to the field and shadowing colleagues in the darkroom. In the Brooklyn Museum installation, this photojournalism—penetrating scenes of poverty and tragedy in the twentieth-century American city—appears alongside portraits of wealthy clients and fellow artists that she made on the side. These are daring exercises in straight photography, made hauntingly beautiful by the almost surgical application of cropping and chiaroscuro.

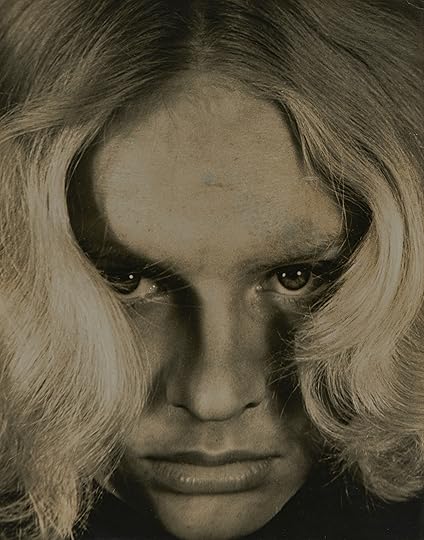

Consuelo Kanaga, Untitled, ca. 1925

Consuelo Kanaga, Untitled, ca. 1925  Consuelo Kanaga, The Widow Watson, 1922–24

Consuelo Kanaga, The Widow Watson, 1922–24 Kanaga favors dramatic closeups. Her gaze captures the piercing blue eyes and supple lips of an androgynous blonde studio model in Untitled (ca. 1925) and the dark, imploring eyes and sunken cheeks of a poor little boy, a recurring journalistic subject, in Malnutrition (1928) with the same devotional intensity. It takes a delicate boldness to get that close to a subject, and an impish curiosity. Kanaga wants to know them, through their faces and hands. Hers is a necessary violation, a shedding of the external signifiers binding her subjects to the realities they suffer. At times, her composition and framing are in service of sly allusions to the biblical and art historical, as in the deprived Madonna and Child of Untitled (New York) (1922–24) and the three mourning Fates of Fire, New York (1922), finely rendering the human experience specific and universal.

In the late 1920s, Kanaga made a sojourn through Europe and North Africa that shifted her work from documentary photography to liberated image making. She took inspiration from French and Italian painting, like the Pictorialists before her, and even tried her hand in watercolor. She felt challenged by photomontage, which was all the rage in Germany and Austria. In Tunisia, she was struck by otherworldly light and towering minarets. In portraits of the Kairouan locals, she eschewed anthropological and orientalist trappings, capturing them as she did the people back home, in their candid fullness. A smile or a glint in the subject’s eyes, as in those of the young woman in Young African, North Africa (1928), tell of an intimacy that has been broached and kindled.

Consuelo Kanaga, Hands, 1930

Consuelo Kanaga, Hands, 1930“I would sacrifice resemblance any day to get the inner feelings of a person,” Kanaga wrote home to her friend and patron Albert Bender. “It seems so much more of one than our face which is so often just a mask.” In the darkroom, she mixed formulas to achieve specific tones, experimented with burning and overexposure. She traced lines over a printed image with graphite, or smudged them altogether. She cropped prints and negatives with equal ferocity. All of this, a calibration of drama with dignity, or the feeling of connection to the subject with implication and self-awareness on the part of the viewer.

Time blurs magnificently at the midpoint of the show, a delightful interlude of Americana still lifes, landscapes, and abstract nature studies, showcasing Kanaga’s compulsion to push her medium to its limits. Mostly devoid of human subjects, the pictures are charged with her wit and worldview. The lipped porcelain pitcher in Untitled (1925) is a reclamation of the libido from the exploitation of capital, represented here by the hard-edged bar of Ivory soap. The Abstraction and Untitled series (1948), snapshots of the reflective surface of the pond by the Yorktown Heights home Kanaga shared with her husband, the painter Wallace B. Putnam, like Monet’s water lilies, occupy the threshold between the material world and the divine.

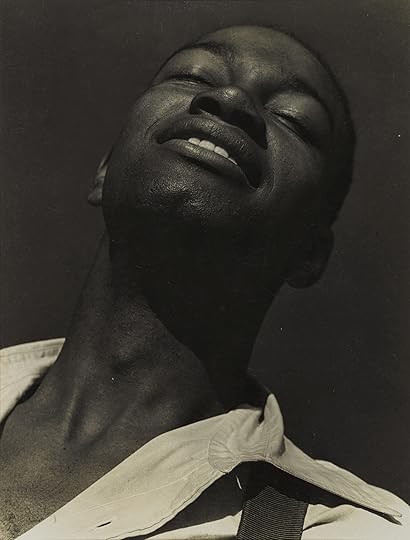

Consuelo Kanaga, Kenneth Spencer, 1933

Consuelo Kanaga, Kenneth Spencer, 1933  Consuelo Kanaga, She Is a Tree of Life, 1950

Consuelo Kanaga, She Is a Tree of Life, 1950 Among Kanaga’s most important works is She Is a Tree of Life, II, Florida (1950), which she made during a visit to the mucklands of Florida, where migrants worked the fields, picking lettuce and other vegetables. She had spent the day with her subjects, a mother and her family, learning about their life and toil, taking several pictures. This composition, practically sculptural, arrived in their parting moments when the light was just right. It would be immortalized in Edward Steichen’s landmark Family of Man exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, in 1955. “This woman has been drawing her children to her, protecting them, for thousands of years against hurt and discrimination,” Steichen captioned the photograph. The image is a technical study of contrasts, epitomizing Kanaga’s trademark blend of social documentary and expressive pictorialism.

Kanaga’s early descriptions of her affinity for Black subjects can sound naive, paternalistic, or overly romantic. Yet, in a time when discrimination was law and racial terror was ever-present, she aligned her work with Harlem Renaissance artists and intellectuals, celebrating Black beauty and self-expression while pushing for progressive reform. Many of these portraits were collaborations with the subjects, not only in the studio, but in life as close personal relationships. Kenneth Spencer (1933) is a tight close-up on the actor and singer. His head is lifted, soaking in the warmth of what appears almost like stage lighting. If you were to zoom out of the frame, he could be, blissfully, mid-pirouette. The poet is in repose on a méridienne in Langston Hughes (ca. 1934), Olympia in a smart suit, a playful assertion of the freedom to move between the worlds of desirability and respectability. Eluard Luchell McDaniel (1931) cradles Kanaga’s family friend and constant muse (the San Francisco police once detained them for driving in a car together). Eluard rests his head on the grass, hands pressed against his cheeks, eyes closed in unburdened tranquility. In these final rooms of Catch the Spirit, there is a surge of both fiery passion and gentle uplift.

Consuelo Kanaga, After Years of Hard Work (Tennessee), 1948

Consuelo Kanaga, After Years of Hard Work (Tennessee), 1948All photographs © Brooklyn Museum

Consuelo Kanaga, Untitled, 1936

Consuelo Kanaga, Untitled, 1936 Kanaga’s final assignment as a photojournalist, a favor for her friend, the poet Barbara Deming, was to document the Quebec-Washington-Guantanamo Walk for Peace, a series of marches, from 1963 to 1964, for Black liberation and in protest of the Vietnam War. The photographs, some of which Deming later published in Prison Notes, harken back to Kanaga’s early days of straight photography. Yet, even at this late stage, she could not resist the application of painterly flourishes. Dramatic shadow throws the smiling titular figure of Ray Robinson, Albany, Georgia (1963) into stark relief. While his more solemn comrade holds out an open palm, curved and questioning, Robinson’s arm grips with assurance a suitcase with the acronym “CORE,” for the Congress for Racial Equality, and the phrase “LOVE FORGIVES,” from Corinthians. The image is taken from a low angle, so the figures are elevated. Behind them are bare trees, leafless tendrils reaching to the sky.

Catch the Spirit arrives in a season of diminished public welfare, deportations of lawful residents, and criminalization of dissent, all government sanctioned. Kanaga’s creativity and conviction, therefore, feel especially timely, and the exhibition a call to action, as well as a case for beauty in the face of adversity. “I don’t feel I’m young enough to stand the rigors of peace walks,” Kanaga, who was almost seventy and suffering from emphysema, said about marching with the coalition of young people in Georgia, Black and white together. “But I’m heart and soul for peace and integration and if my camera can be of help, I want to use it to the fullest.”

Consuelo Kanaga: Catch the Spirit is on view at the Brooklyn Museum through August 3, 2025.

A Photographer Who Built a Career Through Listening

Sarker Protick found photography through music. Growing up in Dhaka in the 1990s, he remembers his mother’s fondness for singing and his father’s love of the Doors, Leonard Cohen, and the Beatles. “My father wasn’t a musician,” he recalls. “But he was a very good listener.” In college, Protick learned to play guitar and then the piano, formed a band, and began writing his own music.

Photography was merely a hobby then, a way of documenting life in college, his friends, and his city. After some encouragement from an uncle who saw his pictures, Protick decided to enroll in night classes at the Pathshala South Asian Media Institute in 2009. Established in 1998 by the photographer and activist Shahidul Alam, Pathshala was (and still is) unlike any other institution in South Asia, founded with a strong documentary focus. When Protick arrived, he was surrounded by photojournalists from the region, but it wasn’t until he saw the work of Robert Adams and William Eggleston, another photographer-musician, that he felt a deep resonance. “This is what photography can also be,” he recalls thinking. “This is what I wanted to create.”

Sarker Protick, from the series Leen (Of River and Lost Lands), 2011–ongoing

Sarker Protick, from the series Leen (Of River and Lost Lands), 2011–ongoing  Sarker Protick, from the series Leen (Of River and Lost Lands), 2011–ongoing

Sarker Protick, from the series Leen (Of River and Lost Lands), 2011–ongoing Protick splits music and images as two distinct parts of his journey as an artist, but over the last fifteen years—and across projects spanning photography, video, and sound—he’s built a career out of listening. His work uses historical frameworks rooted in Bangladesh and the wider Bengal region to unpack questions about photography’s relationship to time and memory. Combining deep research, a patient eye, and an intuition for visual rhythm, his approach negotiates the impulses of the photojournalist with those of the musician. “Musical composition is such an editorial process; you build a logic through it,” he says. “That selectiveness is vital, and it came to me naturally as a photographer.”

Protick’s compositions are quiet and spacious, inviting a wide field for association despite their highly specific context. In one of his earliest series, Leen (Of River and Lost Lands) (2011–ongoing), he photographs the Padma River that cuts through Bangladesh. Waterways dominate the country’s topography, and the river is embedded into its national and cultural story. In college, Protick read the novel Padma Nadir Majhi (The Boatman of the Padma) by prolific Bengali writer Manik Bandopadhyay, which exposed him to the narrative potential of the river, an artery signaling both life and destruction.

Sarker Protick, from the series Mr. & Mrs. Das, 2012–16

Sarker Protick, from the series Mr. & Mrs. Das, 2012–16  Sarker Protick, from the series Mr. & Mrs. Das, 2012–16

Sarker Protick, from the series Mr. & Mrs. Das, 2012–16 He later drew a connection to the American highway, and the work of Robert Frank, Ed Ruscha, and Stephen Shore from the 1950s to ’70s. “In the US, the entire country is road,” Protick says. “But it’s not the same here. The traveling mode is the river, and it’s always been the lifeblood.” On the riverbanks, land and livelihoods are at perpetual risk of being swallowed up by flooding. Over multiple trips, Protick observed the Padma’s eroding embankments with great care, using a subdued photographic palette to represent the calm yet alarming ticking of a geological clock.

In the series Mr. & Mrs. Das (2012–16), Protick telescopes into a single apartment in Dhaka, where Protick photographs his aging grandparents in their final days. His images of sparse interiors contrast with archival imagery of his subjects’ life as a young couple. The whitened, near-clinical palette reappears, isolating seemingly nondescript objects—telephones, vases, frames, loose wires, suitcases—to tell a larger story through fragments. As on the river, Protick attempts to grasp time’s pervasive crawl, and from this stillness honors the ordinary, intimate details that furnish a shared life.

Sarker Protick, from the series Jirno (Spaces of Separation), 2016–21

Sarker Protick, from the series Jirno (Spaces of Separation), 2016–21Nature, memory, and time gradually became thematic tentpoles for Protick. His video work Raśmi (2017–20) projects these ideas onto a cosmic scale. A montage of images creates a constellation of flashing associations between light and dark, abstract and figurative scenes, and planetary and microscopic degrees—all layered over music composed by Protick himself. We move from lightspeed to the lumbered march of historical time in the series Jirno (2016–ongoing), meaning “ruins” in Bangla. Here, Protick uses serene, long-exposure compositions to depict abandoned feudal estates, once owned by Hindu landlords from pre-Partition Bengal, now decayed and returning to the landscape.

Sarker Protick, from the series Jirno (Spaces of Separation), 2016–21

Sarker Protick, from the series Jirno (Spaces of Separation), 2016–21  Sarker Protick, from the series Jirno (Spaces of Separation), 2016–21

Sarker Protick, from the series Jirno (Spaces of Separation), 2016–21 The images, shot in black-and-white and often in hazy conditions, force dense greenery to flatten against the buildings’ architectural contours. “There’s always an extra thing happening, even in a very static, still moment,” Protick says of his approach. “Nature becomes more present in the photograph.” The colonial-era buildings stand as frozen testaments of the region’s transformation (or lack thereof), and the place of the past in the present. If the story of Bengal over the twentieth century is in some ways the story of migration, Protick mines for what is left behind.

Sarker Protick, from the series Leen (Of River and Lost Lands), 2011–ongoing

Sarker Protick, from the series Leen (Of River and Lost Lands), 2011–ongoing  Sarker Protick, from the series Ishpather Poth (Crossing), 2019–23

Sarker Protick, from the series Ishpather Poth (Crossing), 2019–23 The marks of movement reemerge as a theme in Ishpather Poth (Crossing) (2017–23), which traces the built legacy of the Bangladesh Railway, once part of the sprawling train network that traversed the historical Bengal region. Following two partitions—of India in 1947 and Pakistan in 1971—many lines on the railway were severed from their ends. As in Jirno, Protick expresses historical time through the stoic language of the built form; industrial remnants of colonial rail workshops and power stations, abandoned offices and bungalows, and aging railway towns.

In one image, the steel mouth of the Hardinge Bridge opens into a mile of track over the Padma. The bridge—which evokes the twin legacies of colonial engineering and the Bangladesh Liberation War—also appears in the Leen series, this time from the perspective of the Padma below. Both projects brought Protick back to the Pabna District in central Bangladesh, home to one of the largest railway junctions in the country, and to the Padma. “Every time I finish a project, I somehow find a layer for another,” he says.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Sarker Protick, from the series Awngar (Ash to Ash), 2022–24

Sarker Protick, from the series Awngar (Ash to Ash), 2022–24  Sarker Protick, from the series Awngar (Ash to Ash), 2022–24

Sarker Protick, from the series Awngar (Ash to Ash), 2022–24 Take a step back and a greater tapestry emerges. The river, the ruin, and the railway become interconnected protagonists in a story spanning centuries and national borders. Protick’s latest series, Awngar (Ash to Ash) (2024), recently exhibited at C/O Berlin, adds another layer. Made across modern-day India and Bangladesh, the series explores the linked development of railways and the coal mining industry under British rule. Its images and video works are characteristic of Protick’s style, atmospheric and rich in allusion. Landscape views of marred coal mines and videos of explosions juxtapose more meditative scenes of mining offices and coal-black surfaces. Predatory capitalist and colonial extraction have mercilessly shaped Bangladesh’s ecological reality, the series argues. “Awngar” is the Bengali word for coal in a red-hot state, ready to combust, and the series associates this catastrophic, latent energy with imperial and industrial ambitions in the region.

Installation view of Sarker Protick: Awngar at C/O Berlin, 2025

Installation view of Sarker Protick: Awngar at C/O Berlin, 2025Photograph by David von Becker

Installation view of Sarker Protick: Awngar at Crespo Open Space, Frankfurt, 2025

Installation view of Sarker Protick: Awngar at Crespo Open Space, Frankfurt, 2025Photograph by Jens Gerber

Memory is difficult source material. While many of these explorations are historically embedded, they raise universal questions about the power of the image to illuminate a place. These questions do not end behind the camera for Protick, who has been on the faculty of Pathshala since 2013 and acts as the co-curator of Asia’s longest-running international photography festival, Chobi Mela, which will return for its eleventh edition this December, in Dhaka. Across his work, Protick frames the past with the present, where looking constitutes both remembering and recomposing. Robert Adams once said of his forty years of work on the American West, that, “by looking closely at specifics in life, you discover a wider view.” In his stillness and attention, Protick composes his own.

Sarker Protick, from the series Awngar (Ash to Ash), 2022–24

Sarker Protick, from the series Awngar (Ash to Ash), 2022–24  Sarker Protick, from the series Awngar (Ash to Ash), 2022–24

Sarker Protick, from the series Awngar (Ash to Ash), 2022–24All photographs courtesy the artist

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.

April 28, 2025

Bruce Weber’s All-American Obsessions

Prague is a place shot through with satire. Kafka is considered a sort of mascot and the sculptures of David Černý—two men pissing onto a Czech Republic–shaped fountain’s basin, King Wenceslas riding his horse upside down, Sigmund Freud hanging from a flagpole—remain some of the city’s most visited attractions. Bruce Weber’s art, such as the pieces in his first retrospective My Education, which was on view last fall at Prague City Gallery (GHMP), is decidedly not satirical. A photograph titled The Duchess of Devonshire Feeding Her Chickens at Chatsworth (1995), for example, isn’t meant as social commentary, even if the duchess, Deborah Cavendish—whom Weber met through her granddaughter, the fashion model Stella Tennant—is feeding said chickens from a dented tin bucket while wearing diamonds and pearls. Taking in the 250-plus photographs and videos at GHMP’s Stone Bell House, I wondered: Why here? And, considering Weber currently occupies a gray area of that graying concept of “cancellation,” why now?

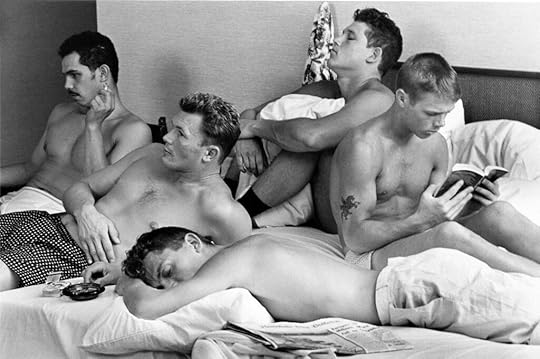

Bruce Weber, On Leave in Waikiki, 1982

Bruce Weber, On Leave in Waikiki, 1982Born in 1946, Weber left a Pennsylvania farm town to study film at New York University, and with help from his sister Barbara (then head of publicity for United Artists Records), found himself snapping photos of famous musicians: David Bowie, Ike and Tina Turner, Frank Zappa, Iggy Pop, Patti Smith. Next, a move to Paris, then back to New York to study at the New School under Lisette Model, whom he’d met through Diane Arbus. On a go-see in 1973—he modeled, too—Weber met Francesco Scavullo’s studio manager, Nan Bush, who became his agent, getting him his first fashion photography jobs: Dillard’s, GQ, and Ralph Lauren, with whom he would work closely for forty years.

In 1978, Weber shot a Calvin Klein jeans campaign, and in 1982, the brand’s first underwear ads. Throughout the 1980s and ’90s, his billboards caused a sensation, putting Waspy Adonises in blatantly seductive poses at massive scale. He developed an eye for interpreting artifice through the hallmarks of authenticity—imagine Dust Bowl documentary as Italian Neorealism, behind-the-scenes of pageantry, serious jocks goofing off. His photographs made up, in large part, the infamous plastic-wrapped Abercrombie & Fitch Quarterly (1997–2007)—a commercial catalogue that people actually paid for, with a peak circulation of over a million—which, depending on the critic, was an ingenious marketing tool or camouflaged pornography.

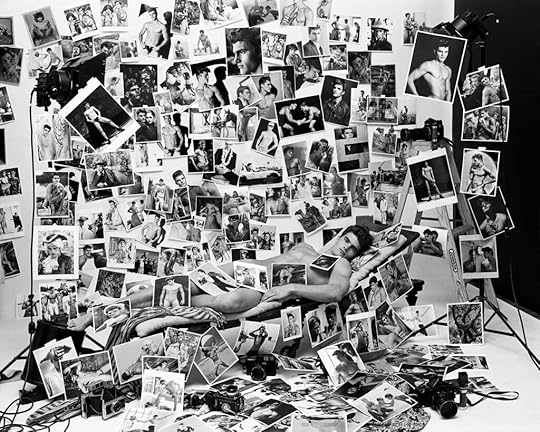

Bruce Weber, Peter Johnson at the Chop Suey Club Studio, New York, 1999

Bruce Weber, Peter Johnson at the Chop Suey Club Studio, New York, 1999For generations, magazine readers, mallgoers, and the habitues of galleries and museums encountered Weber’s singular but widely imitated style. Then, in 2017, he was accused by a male model of unwanted sexual advances. Others soon voiced similar sentiments, and most of his contracts promptly ended. Today, his vision remains ubiquitous, even as his name is decreasingly evoked in advertising and editorial meetings. Newer fashion brands are publishing campaigns that directly reference A&F’s homoerotic preppy handbook, perhaps most notably Raimundo Langlois, who has said of his own denim- and khaki-centric label, “It’s perversion of the familiar. It’s memory reconstruction.”

“What I love about Bruce Weber’s work is the possibility of being subversive within the most mainstream of channels,” said Matthew Leifheit, a visual artist who has appropriated A&F merchandising in his own photography. Leifheit discovered Weber’s work in the mall when he was growing up in Wisconsin. “I was seduced by the matter-of-factness of his photographs, thinking I wanted to be these guys, when truly I wanted to have them. Later, I recognized the pictures were transparently referencing a lineage of setups for ‘physique photography’ as well as the history of more formal gay erotica including George Platt Lynes and Wilhelm von Gloeden.”

Bruce Weber, Rugby players in Van Cortland Park, Bronx, New York, 2003

Bruce Weber, Rugby players in Van Cortland Park, Bronx, New York, 2003Weber’s dozens of monographs may amount to hundreds if we are to include catalogues and a self-published semiannual, All-American, now on its twenty-first issue, but a forthcoming book from Taschen, Bruce Weber: My Education, will mark the seventy-eight-year-old’s first official career survey. The book’s title refers to Weber’s own creative maturation, but the work provides so many markers of a zeitgeist, it naturally reflects our education as well. Beyond fashion callbacks, all the super-staged spontaneity, smiling bodybuilders, and rural stars-in-waiting now found on our social media feeds feel at times derived from that same bizarro America that Weber started to dream up about four decades ago.

Weber is attributed as an originator of what we now call lifestyle branding, a way of generating desire through imagery that isn’t product-oriented yet results in product sales. The ads for which Weber became in demand sold people and places, not clothing. How could a catalogue of nearly or naked youths horseplaying in the woods translate to a successful sportswear company? Ask anyone who couldn’t stay away from A&F stores as a teen. How did Calvin Klein, with its decidedly plain underwear line, become the essential logo on an elastic waistband? That arguably had much to do with Weber’s photograph of an Olympic pole-vaulter, which froze traffic when it appeared on a billboard in Times Square in 1983.

Bruce Weber, Stella Tennant and Valeria Mazza with friends at the nightclub, Punta del Este, Uruguay, 1998, for Vogue Italia

Bruce Weber, Stella Tennant and Valeria Mazza with friends at the nightclub, Punta del Este, Uruguay, 1998, for Vogue Italia  Bruce Weber, Naomi Campbell and her fan club, New York, for Vogue Italia, 1994

Bruce Weber, Naomi Campbell and her fan club, New York, for Vogue Italia, 1994To see these images now is to recognize them from an earlier, non-art context, and to recall their impact: a stirring of sexuality, a seed of aspiration. I didn’t know he did this is something the curators—Nathaniel Kilcer, a creative director who has worked with Weber for decades, and Helena Musilová, director at GHMP—say they hear often. The first picture in the exhibition was one of those early Calvin Klein shots, from 1988, for the fragrance Obsession: A nude man facing a nude woman, both standing on a rope swing and arching their backs. Maybe you remember it from a magazine. Nearby was a wall-sized print of a nude Peter Johnson, the protagonist of Weber’s film Chop Suey (2001), and a portrait of four golden retrievers collared with signs that read “Dogs for Peace,” a still from Weber’s tribute to one of them, A Letter to True (2003). The 1990 music video he directed for the Pet Shop Boys’ “Being Boring” was projected behind that first room’s Gothic archway, sound on. At the end of the exhibition’s suggested route: the video for their “Se a vida é (That’s the Way Life Is)” (1996).

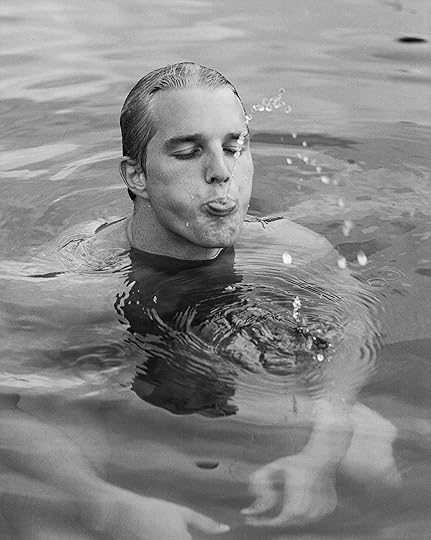

Bruce Weber, Jason, Bear Pond, Adirondack Park, New York, 1989

Bruce Weber, Jason, Bear Pond, Adirondack Park, New York, 1989  Bruce Weber, Ric and Natalie, Villa Tejas, Montecito, California, 1987

Bruce Weber, Ric and Natalie, Villa Tejas, Montecito, California, 1987 The embedded editorializing in Weber’s work served a challenge when curating the show, Kilcer told me. “So many times, you need the story to inform. In the fashion imagery, he is such a cinematic photographer, so it’s like you’re lifting these pictures out.” Though they were not as present in My Education, words—quotes, diary entries, lyrics, poetry—are usually everywhere in Weber’s work. Certainly, the choice of opening and closing numbers is not without intention. “I came across a cache of old photos,” begins “Being Boring,” a reminiscence of youth. It is also a song about death, written by singer Neil Tennant for a friend who suffered from AIDS in the ’80s.

To see these images now is to recognize them from an earlier, non-art context, and to recall their impact: a stirring of sexuality, a seed of aspiration.

What at first appears as pure joy is more accurately the tension between innocence and adulthood, life and its drive toward expiration. Haphazard collage is used as palimpsest, a way of seeing the dimensions of a moment—serious sentiment met with frolicking animals, just as, in life, a dog may sense despair and offer, bewilderingly, an expression like happiness. On a wall facing that first projection was Weber’s scribbled dedication “to my friends here,” listing first names of collaborators and subjects who attended the opening, mentioning “my dogs say Hi (Barking)” over a signature: “Bruce Weber + my wife Nan Bush.” (Yes: Commonly described as a preeminent gay artist, Weber has been happily married to a woman for nearly half a century.) Seeing this inscription facing the music video, I was reminded of Tennant’s repeated laments about publicly coming out, maybe best said in Hot Press: “I can’t see any reason to define gay people by their sexuality.”

Bruce Weber, Boys at Butterfly Beach, Santa Barbra, California, 1982

Bruce Weber, Boys at Butterfly Beach, Santa Barbra, California, 1982Weber hears music in his head when he looks at photography. Irving Penn, he told me, is classical, but “in Broadway terms, he’s strictly George Gershwin.” Whereas Richard Avedon is more “Harold Arlen, you know, ‘Somewhere Over the Rainbow.’” And what would soundtrack Weber’s work? “I’d have to say, maybe, Chet Baker.”

No surprise there. Weber directed the Oscar-nominated documentary feature Let’s Get Lost (1988), which follows the heroin-addled jazz trumpeter and singer during his forlorn final months. Mention of the name sent Weber into a reverie, not about that intense, sustained, ’80s interaction but a time of initial discovery, in the early ’60s: “I thought, Oh, god, it would be so much fun to be that guy.” A funny thing to say about a man he essentially watched deteriorate, I think. I mentioned the videos from the exhibition. “I like the Pet Shop Boys, too,” he said, “because their music was so exciting, and I was really shy.”

Bruce Weber, Pedro Almodóvar, Madrid, Spain 2000

Bruce Weber, Pedro Almodóvar, Madrid, Spain 2000  Bruce Weber, Louise Bourgeois, New York, 1996

Bruce Weber, Louise Bourgeois, New York, 1996 This is a man who isn’t afraid to meet his idols—who meets them all the time. As a child, he was obsessed with Elizabeth Taylor. He later befriended her while she sat for him. A room in My Education is dedicated to his portraits of some artist heroes: Andrew Wyeth, Paul Bowles, Sheila Hicks, Joan Didion, Pedro Almodóvar, Jane Campion, Francis Ford Coppola, Purvis Young, Louise Bourgeois, Helmut Newton, Georgia O’Keeffe, Allen Ginsberg.

Other rooms displayed stars of film, fashion, music, sport, and society, many of whom Weber he counts as close friends. Always present, though, is a calculated distance between photographer and subject, including street-cast models and pets. Everyone poses, sometimes in a paper crown or on a pedestal, propped up with the dizzy angles of fandom or an unrequited crush.

Such meditations on idolatry are ironically situated within the circa mid-fourteenth-century Stone Bell House, part of Prague’s long history of iconoclasm. When I arrived and met the exhibition’s creative and executive producers, Milosh Harajda and Markéta Tomková, I asked why we’re here, of all places, instead of, say, Weber’s Miami Beach HQ during that city’s Art Basel week? The two took this on as a pet project, they said, suggesting that their city would be the perfect jumping-off point for an international tour. After the allegations, the lost commercial clients, and then the pandemic, the studio needed a soft place to land—somewhere everyone in their inner circle might visit for an opening but sheltered from the unforgiving art or fashion world stages.

Installation view of Bruce Weber: My Education, Prague City Gallery, Stone Bell House, 2024

Installation view of Bruce Weber: My Education, Prague City Gallery, Stone Bell House, 2024Photograph by Noe DeWitt

Installation view of Bruce Weber: My Education, Prague City Gallery, Stone Bell House, 2024

Installation view of Bruce Weber: My Education, Prague City Gallery, Stone Bell House, 2024Photograph by Noe DeWitt

That My Education premiered in a city defined for centuries by its anti-establishment preachers gives it a sheen of Gothic agnosticism. Weber’s work might pray at the altars of the Bible Belt and Appalachia—athletes, beauty queens, and purebreds—but a larger story weighs the value of such dedication, juxtaposing all that religion with other tragic icons, such as those in show business. Hang on to the fantasy, it says, because facing reality won’t be what brings salvation.

In January 2018, Weber responded to his situation via Instagram, denying all charges. “I have spent my career capturing the human spirit through photographs and am confident, that, in due time, the truth will prevail,” he wrote. His legal battles concerning the misconduct allegations ended in 2021, after one model’s claim was dropped and a lawsuit involving a joint complaint made by five others was settled out of court. At a time when many fashion photographers (Mario Testino, Greg Kadel, Patrick Demarchelier, David Bellemere, and Terry Richardson, to name a few) were being cut off by editors and brands due to accusations of inappropriate behavior on set, the mass cancellation prompted broader consideration of the industry itself. What sells, after all? Would modeling be forever changed with the advent of the intimacy coach? How much doting, on the part of a photographer, crosses a line into flirtation, or harassment?

Bruce Weber, Shalom Harlow and friends, Paris, for Vogue, 1995

Bruce Weber, Shalom Harlow and friends, Paris, for Vogue, 1995Weber is soft-spoken, a white-bearded man with twinkling eyes. When we met, he was wearing a brown Carhartt canvas jacket over a denim Bode shirt, mentioning that the designer duo are his friends. He told stories he’s likely repeated many times, such as the one about when he and model Kate Moss visited an orphanage in Vietnam and had to pull themselves away from those poor smiling kids for their shoot, towing a tractor-sized trunk for a single John Galliano gown. It was Christmastime and he apologized for cutting our conversation short: He was already behind writing his holiday cards. I couldn’t quite bring myself to mention sex.

“If you asked him, he would say he is a gay man,” said Eva Lindemann-Sánchez, a film producer who has worked with Weber for decades. “But no one asks him. It is also true that he is married to a woman who he adores and greatly admires and respects and has been with for almost fifty years.” Kilcer added that one of Weber’s own adages says, “Photography is about having a crush. On a man, a woman—” Lindemann-Sánchez nodded. They said, in unison, “a dog.” I brought up the “queer artist” descriptor, to which Lindemann-Sánchez answered, “There’d be a part of him that would take ownership over that, but it would simultaneously surprise him.” “He leads with emotion,” Kilcer said. “He embraces the awkwardness of that, the disappointment that comes from that, the spontaneity, but also the vulnerability.”

“To answer the question,” Lindemann-Sánchez chimed in again, “he does not identify as a queer photographer. People want to put him there.”

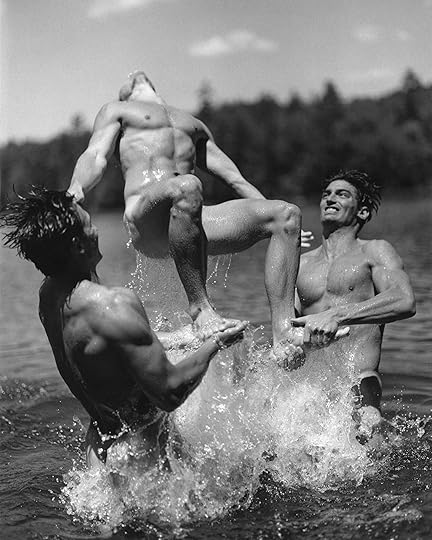

Bruce Weber, Ray, John and Eric, Bear Pond, Adirondack Park, New York, 1990

Bruce Weber, Ray, John and Eric, Bear Pond, Adirondack Park, New York, 1990  Bruce Weber, Jason, Bear Pond, Adirondack Park, New York, 1989

Bruce Weber, Jason, Bear Pond, Adirondack Park, New York, 1989 Weber’s well-documented live-laugh-loving home life doesn’t totally contradict the raw sensuality seen in his portfolios of male nudes, such as the much-coveted photographs in the book Bear Pond (1990), shot around his and Bush’s home in the Adirondacks. More often, heteronormative tropes, such as Hamptons luncheons and movie-star romances, are intertwined with homoerotic scenes, suggesting a world in which these ideas live in harmony.

In a small theater attached to the coat room of the exhibition, a few of Weber’s shorts, including Backyard Movie (1991), played on a loop. Via handwriting and voiceover, we learn that as a child, Weber didn’t play sports, preferring to practice showtunes in his sister’s bedroom and snuggle with the family French poodle, Coquette. He recalls his mother asking him, “Which way are you swinging?”

“I told her,” the text continues, overlayed on black-and-white home video clips spliced with a nude young man emerging from a swimming pool and dogs running on a beach, “that the night before I carried a drunken Tennessee Williams up the stairs of a restaurant and as I put him into a taxi he turned to me gently putting a hand to my cheek and just said ‘oh, beauty.’” The footage jumps into color, showing children walking through a flower garden. Animated handwriting details a trip to the famous gay bar Stonewall Inn, where a man asks young Weber to dance. Scared, he sits in a corner and watches the room morph into a salon of actors and authors. “Being lucky I can just close my eyes and transport myself to another time and place,” he writes. “A lot of people think having a big fantasy life is dangerous. That’s why people have tried to take it away from me.”

Bruce Weber, Self-portrait with Peter Johnson, during the last day of filming “Chop Suey,” Golden Beach, Florida, 1999

Bruce Weber, Self-portrait with Peter Johnson, during the last day of filming “Chop Suey,” Golden Beach, Florida, 1999In Chop Suey, Weber invokes Clive Bell describing to Virginia Woolf the feeling of anticipating a visit from a friend. “That sense of longing was what I wanted to put in my early pictures of him,” Weber continued, referring to his muse Peter Johnson. “When I was filming Peter and his friends in the shower, I remembered myself at that age. In that fantasy, I would have been one of those kids, clowning around without a care in the world, but back in my hometown of Greensburg, Pennsylvania, it was a different story. I’d be swimming all day at the country club and my mom would tell me to shower and dress for dinner. I’d tell her I couldn’t, because the locker room would be too crowded at that hour. It seemed to me that every guy in the whole Midwest would be in that locker room, showering. We sometimes photograph things we can never be.”

Love is mostly projection, idealization. We revisit our first crushes for the rest of our lives, wherein unattainability was paramount. For a gay youth in the 1950s and ’60s, this exciting period of discovery is twisted with shame, the other side of which is yearning for a heterosexual lifestyle so extremely romantic it could counterbalance any natural lust for the socially unaccepted. Weber’s work has spurred intense desire, but it is essentially an exploration of that desire, the wanting and the wanting to want.

The first and only other time Weber had been to the Czech Republic was in 2000 for a Vanity Fair cover story with Heath Ledger, who was filming A Knight’s Tale and who later died from a drug overdose at age twenty-eight. Jeff Buckley, who, Weber reminds me, drowned in the Mississippi River at thirty, is featured in My Education as well, as is Stella Tennant, who committed suicide at fifty, and Dash Snow and River Phoenix, who overdosed and died at twenty-seven and twenty-three, respectively. I asked about youth and tragedy, as a theme.

Bruce Weber, Madonna, New York, 1986

Bruce Weber, Madonna, New York, 1986 Bruce Weber, Eton Boys at Chiswick House, London, 1984

Bruce Weber, Eton Boys at Chiswick House, London, 1984All photographs © the artist

“I had amazing encounters with these people,” Weber said, the focus leaving his eyes. “They were so alive for me. I believed so much in what they thought, what they were doing, how much they loved doing things. They had that romance, that kind of honesty. Photographers and filmmakers are always trying to find that. Sometimes, if you look too hard, you’ll never find it, and it comes out as something else.” “People who are interesting defy the buckets you’re trying to put them in,” said Kilcer, of Weber. And Weber’s work rearticulates those very buckets: The impossible standards of masculinity and femininity, of innocence and stardom, the people who epitomize them. A room in My Education exclusively featured statuesque nude men, some printed as partitions and arrayed atop a mirrored floor like classical fountains. Gazing at an image of Madonna kissing her own reflection, one can almost hear the crowd’s hush that leaves a pop star lonely. Another room of documentary photography showed citizens in war-torn countries and post-industrial America. Inner-city kids, veterans, and orphans beam for the camera, just as the fashion models do.

April 15, 2025

Announcing the 2025 Aperture Portfolio Prize Shortlist

Founded in 2006, the annual Aperture Portfolio Prize aims to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography—identifying contemporary trends in the field and highlighting artists whose work deserves greater recognition. This year, over one thousand artists submitted entries from sixty-five countries, representing a broad and exciting range of styles in photography today.

Aperture invited a jury of cross-disciplinary creatives to judge the 2025 prize: Noelle Flores Théard, senior digital photo-editor, The New Yorker; Lucy Gallun, curator, Robert B. Menschel Department of Photography, MoMA; Zack Hatfield, managing editor, Aperture magazine; and Mark Armijo McKnight, artist and 2019 Aperture Portfolio Prize winner.

“We were drawn to how these five photographers approach expansive stories—whether of political upheaval, war, climate breakdown, or grief—with an intimate attention to the poetics of everyday life,” says Hatfield. “I was especially struck by how these artists manage to locate beauty even within experiences of deep uncertainty, and to do so without sacrificing formal inventiveness or conceptual depth.”

The shortlisted artists for the 2025 Aperture Portfolio Prize are:

Sara Abbaspour, Untitled (splashing water), 2024

Sara Abbaspour, Untitled (splashing water), 2024Sara Abbaspour counters conventional media portrayals of Iran by conjuring a poetic portrait of a society amid a wavering political landscape. Her series floating ocean considers both inner and exterior worlds in states of transition.

Alana Perino, Madi’s Hair, 2022

Alana Perino, Madi’s Hair, 2022Alana Perino’s Pictures of Birds constructs a mesmeric evocation of familial memory and mortality. Photographing in their parents’ home in Longboat Key, Florida, Perino tells a story of preservation as an act of representation and remembrance.

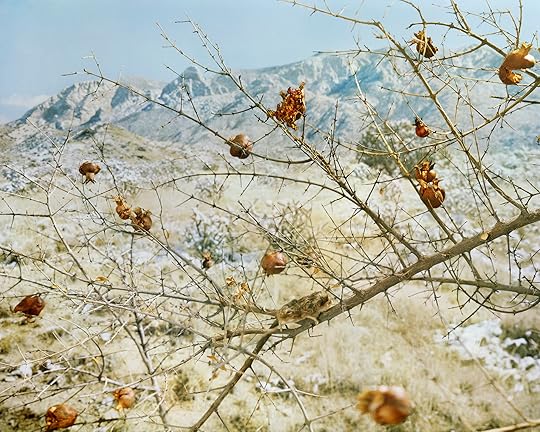

Emma Ressel, Fruit for the Underworld, 2023

Emma Ressel, Fruit for the Underworld, 2023Emma Ressel arranges taxidermized animals in still life tableaux to consider the precarity of damaged ecosystems. Glass Eyes Stare Back contends with the space between life and death, nature and artifice, exploring humanity’s destructive desire to possess the natural world.

Hashem Shakeri, Staring into the Abyss, Afghanistan, 2021–ongoing

Hashem Shakeri, Staring into the Abyss, Afghanistan, 2021–ongoingHashem Shakeri bears witness to daily life in Afghanistan as the country adapts to the return of the Taliban. Staring into the Abyss acts as both a testament to the irrepressible spirit of the country’s women and marginalized groups, and a vivid call to action.

Daria Svertilova, Protector of Kyiv, Ukraine, 2022

Daria Svertilova, Protector of Kyiv, Ukraine, 2022Daria Svertilova offers a generational, quietly searing portrait of present-day Ukraine. Her series Irreversibly Altered invokes a feeling of absence and displacement through dreamlike photographs of what has been left behind.

These photographers join the ranks of illustrious winners and shortlisted artists for the Portfolio Prize in past years, including Felipe Romero Beltrán, Dannielle Bowman, Alejandro Cartagena, Jessica Chou, River Claure, Eli Durst, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Janna Ireland, Abhishek Khedekar, Natalie Krick, Daniel Jack Lyons, Vân-Nhi Nguyễn, Drew Nikonowicz, Sarah Palmer, Avion Pearce, RaMell Ross, Bryan Schutmaat, Donavon Smallwood, Laila Stevens, Ka-Man Tse, and Guanyu Xu.

Selections of work by the five shortlisted artists will be presented at the Association of International Photography Art Dealers (AIPAD), April 23–27, with an opening reception on Wednesday, April 23.

The 2025 Portfolio Prize winner, to be announced on May 13, 2025, will be published in the Summer issue of Aperture magazine, receive a $5,000 cash prize and a $1,000 gift card to shop for gear at MPB.com, and have a presentation organized by Aperture in New York City. The four shortlisted artists will each receive a $1,000 cash prize and an editorial feature on Aperture.org.

Production for the presentation on view at AIPAD in 2025 is made possible by Laumont Editions.

April 12, 2025

On Small Books | With Jason Fulford, Kris Graves, and Carmen Winant

April 10, 2025

A Photographer’s Scavenged Still Lifes

The problem with still lifes is that they’re often lifeless, as suggested by the Italians’ term for the genre: natura morta. From this problem, the photographer Lia Darjes, based in Hamburg and Berlin, is making a life’s work. Her latest pictures, recently collected in her photobook Plates I–XXXI (2024), appear to be formal arrangements but are, in fact, highly improvised tableaux in which snails, squirrels, ladybugs, and other fauna pay visits to the backyards of Berlin and parts unknown. They scavenge the leftovers of human congregation, triggering Darjes’s camera. They revel and rest. One cat, imperious, stares into the lens with convincing intent. Ants line up on watermelon slices like animated seeds. Raccoons paw crumbs and scream into the night. Squirrels, they’re just like us. They party hard, knocking over glasses, making a scene.

Lia Darjes, Plate XXX, 2022

Lia Darjes, Plate XXX, 2022Photojournalism was Darjes’s first passion. Her previous series include portraits of Germans recently converted to Islam and photographs of temporary market stands by the roadside in Kaliningrad, Russia. Those images, with their hunks of meat and ripened fruit, summon the old tradition of vanitas, with its formal satisfaction, all vibrant foreground and dark beyond. Their ad hoc nature tells us that change—like the rubles piled before plastic cups of raspberries in one of her photographs—is all.

Lockdown came, and as the world stilled, memento mori were suddenly everywhere. Darjes relocated to her parents’ house in the German countryside. “I was sitting in the garden one day,” she said, “just thinking, What’s next? And I saw a squirrel jumping on our garden table. I thought, I wonder if I can recreate that.” The world reopened. She made plans—birthday parties for her kids, tea dates with mentors—and then plans for the after-parties, in which tablescapes of balloons and dirty dishes and cups of water to clean paintbrushes were left out overnight. The guest list was self-determined. A crow arrives and selects a perfect cherry from a bunch, seeming to offer it to the viewer. A field mouse sniffs out whether the printed image of a bird on a tablecloth might be a predator. Her images may tilt toward tweeness, particularly in comparison to the technical marvels made by the Dutch still life artists in the seventeenth century, whose painterly efforts embody the futility of trying to cheat mortality. But her work is anchored by the idea that when the stakes are life and death, we all must improvise.

Plate VI, 2022; from the series Plates I–XXXI 500.00 Collect this limited edition by Lia Darjes from the artist’s series Plates I-XXXI, featured in the “Photography & Painting” issue of Aperture.

Plate VI, 2022; from the series Plates I–XXXI 500.00 Collect this limited edition by Lia Darjes from the artist’s series Plates I-XXXI, featured in the “Photography & Painting” issue of Aperture. $500.0011Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

Plate VI, 2022; from the series Plates I–XXXI $ 500.00 –1+$500.0011Add to cart

View cart DescriptionDuring lockdown, the Berlin-based artist Lia Darjes relocated to her parents’ countryside home. In an essay by Jesse Dorris for the spring issue of Aperture magazine, “Photography & Painting,” Darjes reflects on that time: “I was sitting in the garden one day, just thinking, ‘What’s next?’” she recalls. “Then I saw a squirrel jump onto our garden table, and I thought, ‘I wonder if I can recreate that.’” Despite her early passion for photojournalism, Darjes has long been seduced by the dramatic artifice of the Dutch vanitas tradition. “I struggled, because I was always interested by still life, but it’s made up—arranged,” she says.

This photograph is part of the series Plates I–XXXI, the imaginative outcome of her first encounter with that neighborly squirrel. Inspired by that moment, she began orchestrating picnics and luncheons on tables in gardens of friends and family. She leaves behind delicate remnants of these meals, subtly coaxing future guests. Their movements, in turn, trigger the camera, which has been left in place for hours or even days. The result is a fairytale-like scene featuring a coal tit whose presence serves as a quiet testament to the space where the natural world and the human world gracefully intersect.

DetailsLia Darjes

Plate VI, 2022; from the series Plates I–XXXI

Archival pigment print

9 1/2 × 11 3/4 in.

Edition of 20 + 3 artist proofs

Printed, signed, and numbered by the artist

Lia Darjes (born in Berlin, 1984) lives and works in Hamburg and Berlin. She studied at the Hamburg University of Applied Sciences. Darjes is known for Tempora Morte, a documentary still life study about the small stalls seen at street markets in Kaliningrad, Russia. In 2018, Darjes began teaching photography at the Ostkreuzschule für Fotografie, Berlin, an institution she has ran together with the photographer Jörg Brüggemann since 2023. She is represented by Robert Morat Galerie.

Related Content Portfolios A Photographer’s Scavenged Still Lifes

Portfolios A Photographer’s Scavenged Still Lifes Of her previous work, Darjes said, “I struggled. Because I was always interested in the still life. But it’s made-up. Arranged.” The photographs in Plates offer ways out of that bind. They acknowledge the artificiality of documentation. The darkness at the edge of these frames is always a forest, but not always at night; the picnics were sometimes a pretext for the photographs, but you don’t know which ones. It’s hard to resist imposing a little vanitas-y symbolism on, say, Darjes’s image of a wasp attempting in vain to breach a Tupperware of kiwi. We’ve all been there. But we haven’t been alone, and we’re not solely in control. There are other, wilder partiers out there in the world. Here, for once, they get to call the shots.

Lia Darjes, Plate VII, 2022

Lia Darjes, Plate VII, 2022  Lia Darjes, Plate VI, 2022

Lia Darjes, Plate VI, 2022Courtesy the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 258, “Photography & Painting.”

2025 LA Art Book Fair

ArtCenter College of Design

950 S. Raymond Ave

Pasadena

VIP Passes to Photo London 2025

Somerset House

Strand

London

VIP Passes to Independent New York 2025

Spring Studios

50 Varick Street

New York

VIP Passes to 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair 2025

Halo

28 Liberty Street

New York

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers