David Alekhuogie Sees Blackness at the Core of Modern Art

Look at the core of Western modernism. See the Blackness. See African aesthetics. Or, rather, see the ways that Western modernism claimed to know these aesthetics but failed to do so. See through a Black gaze instead.

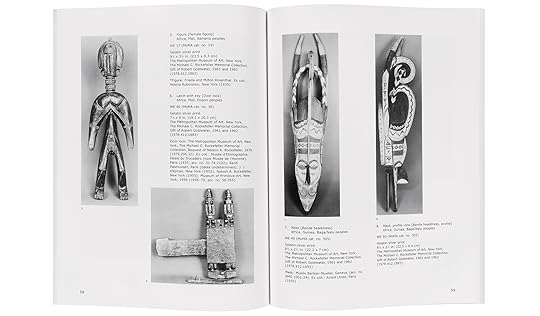

These are the invitations and redirections that animate David Alekhuogie’s project A Reprise (2019–ongoing). The series is anchored in a body of work by Walker Evans produced on the occasion of African Negro Art, a 1935 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, which showcased more than six hundred sculptures from the African continent—most of which had been pillaged to furnish American and European collections. Evans was commissioned to photograph selected sculptures; his images were subsequently published in seventeen portfolios—each with 477 photographs—which were circulated to institutions across the United States and used to teach African art history. Decades later, a selection of the photographs was republished in Perfect Documents (2000), a catalog for an exhibition of Evans’s photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

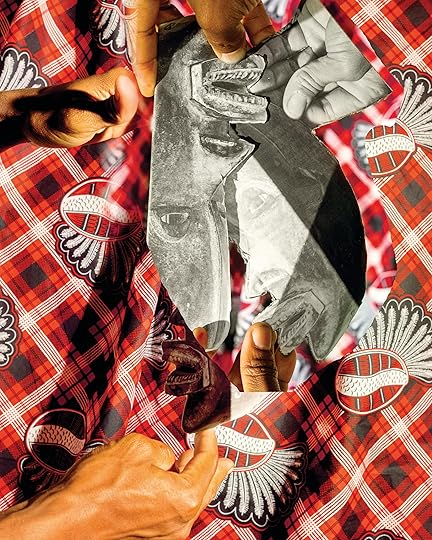

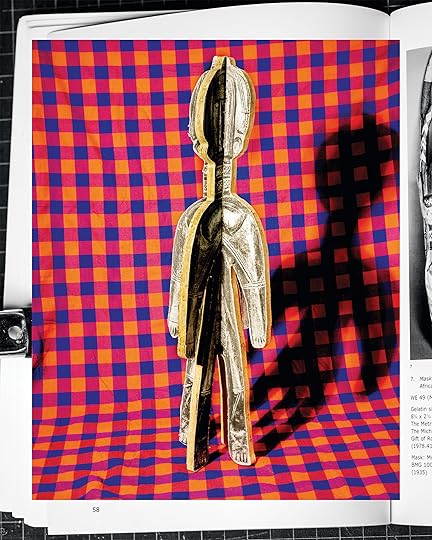

It was a Western lens that made Evans’s photographs possible. But in Alekhuogie’s Reprise, the West’s supposed claim to these sculptures—which was reiterated through both literal and photographic capture—is disrupted. Alekhuogie rephotographs Evans’s pictures and builds three-dimensional cutouts, turning photographed sculptures into sculpture-based photo collages. These are set against lively, brightly hued textiles and rephotographed again, sometimes with Alekhuogie’s hand in the frame.

The resulting assemblages, as Alekhuogie notes in this conversation, attest to a chain of transformations and cross-cultural translations between African aesthetics, Euro-American cultural modernism, and postcolonial critique. Here, having been metaphysically disassembled by the art-historical machinations that produce discrete and distantly beheld objects, the sculptures are reassembled by Alekhuogie. It’s as if they have regained the animacy and fullness of presence with which they were imbued prior to their expropriation and display for Western eyes.

David Alekhuogie, Pull_Up HillFigure, 2019

David Alekhuogie, Pull_Up HillFigure, 2019  David Alekhuogie, Pull_Up w,o,b 2, 2017

David Alekhuogie, Pull_Up w,o,b 2, 2017 Zoë Hopkins: David, before you were showing in galleries, you worked in fashion photography and commercial photography. I’m curious to know how that background informs this body of work, A Reprise. I’m looking at the fabrics in the backdrop and at the way the photographs are staged, and I’m reminded, of course, of the sartorial world and fashion editorials. I’m looking at the way things are staged and this kind of editorial language and wondering if you could give some hints of what aspects of your career rubbed off on this project.

David Alekhuogie: My relationship to photography really starts through music. The fashion photography, the editorial photography, came after working in music journalism. It’s interesting how Black musicians and artists have been able to formulate this language of the radical avant-garde. Even in pop culture, people have been able to thrive through using performance to circumvent things like ownership and cultural capital and being looked at. How do you deal with the task of being looked at or being watched, or having the expectations of your behavior mediated through what you’re supposed to do, not just as an artist but as a worker?

I wanted to make work from the perspective of an outsider, because I think that to grapple with broken, inherited cultural capital is to always be an outsider.

Sometime in grad school, I started thinking about modernism and the relationship to the working class. Things like domestic labor became really interesting to me: the history of quilt-making and cooking and various forms of domestic labor that felt specifically modernist. Whether it’s the history of modernist painting or architecture or design, there’s a tendency to look at the working class as part of a mechanistic structure. So, I became interested in the people in the background or the people in the periphery, post–Industrial Revolution. How people are existing in that space or affecting how we think about what it looks like, at least in America, dealing with whatever comes after Jim Crow, or right before. I wanted to find a language that didn’t seem as labored. One of the things I went through when I got to school is that I started to have a disdain for my language and how it didn’t feel like it was my own.

Hopkins: In terms of an artistic language?

Alekhuogie: Yeah. Not only that, but also how I showed up in the corporate world. How I showed up with my friends and family. How I behave when I get stopped by the police. If I was code-switching, I was doing it subconsciously, which made it worse. Anyway, I think of music, poetry, performance as places where I’ve been able to see Black writers, Black artists find space. There’s a sort of avant-garde language of Black aesthetics in taking pieces of things, like collage. I teach this class about what the remix is. I think those elements, at least, are the early things that are part of my practice.

Hopkins: I love your emphasis on the particular relationship that Blackness shares with fragmentation and remixing. What Fred Moten might call “the break”—or a kind of ruptured subjectivity that begins with slavery and reverberates in Black music—feels so important to the way that a reprise is figured or configured as an assemblage. Could you talk about some of the reading or ideas or research that was informing that project and its early phases? In what context did you actually learn about Walker Evans’s Perfect Documents and the MoMA show African Negro Art? What are the ideas and the more practical forms of knowledge that inform A Reprise?

Alekhuogie: I became a student of documentary photography because I felt that was the work that could be the most meaningful for me and my community. I started taking interest in artists like Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Gordon Parks, and figuring out this relationship between being a working artist and a modernist artist. When you work in fields like photography, design, advertising, or illustration, you’re part of the service class—you’re providing a service. You learn to cultivate images through the client. In grad school, there was an anxiety about the point of view, which influences how people position documentary, and the desire to convince people—as if they need convincing—that straight photography is art. This kind of tension between the photographer who’s hired to provide a service and the artist who has a vision is how I became interested in Walker Evans’s work.

When I was eighteen or nineteen, I started working as a model. At the time, I was also working in fashion and music and all these different things. One of my good friends from high school was a dancer, and he was super interested in the entertainment industry. So, I had gotten into that world just by virtue of the friend group that I was around, and I started working with brands. For a while, I wanted to be a pro skater. I have multiple lives.

David Alekhuogie, Birth Home, 2013

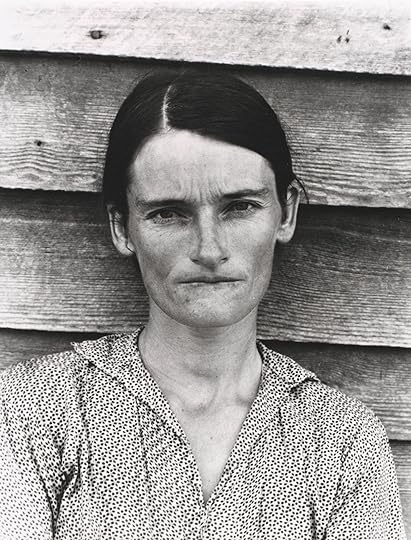

David Alekhuogie, Birth Home, 2013  Sherrie Levine, After Walker Evans: 4, 1981

Sherrie Levine, After Walker Evans: 4, 1981© The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Courtesy Art Resource, NY

Hopkins: Yes, I can tell!

Alekhuogie: It’s all sort of revolved around this hip-hop lifestyle, which is very much an aesthetic now. But the Walker Evans stuff came really hard in graduate school. It was actually Sherrie Levine’s work that I had seen, where she was using the Walker Evans images as her own images, and this interesting commentary on authorship.

Hopkins: Right, she rephotographs pictures from Evans—and others like Edward Weston and Eliot Porter—straight from their catalogs and then claims authorship over the rephotographed images. And it’s been controversial, of course, because it’s quite easy to say she’s just copying these earlier modernist photographers. It’s the same gesture that Richard Prince is making.

Alekhuogie: Yeah. Just how ridiculous it is, it’s front and center. That’s how I became aware of the work. But at the same time, I had been working as a photographer. I had done people’s graduation pictures and baby pictures and engagement pictures and was doing skate photography. So, I knew what it was like for a person to hit your line and be like, “Could you do this thing?” You know what I mean? That’s what happened to Walker Evans, I’m very much convinced. It turned into this, Oh, now you’re this person who is tasked with doing this job but also with this responsibility for representing modernist photography. So there’s these two things happening at the same time.

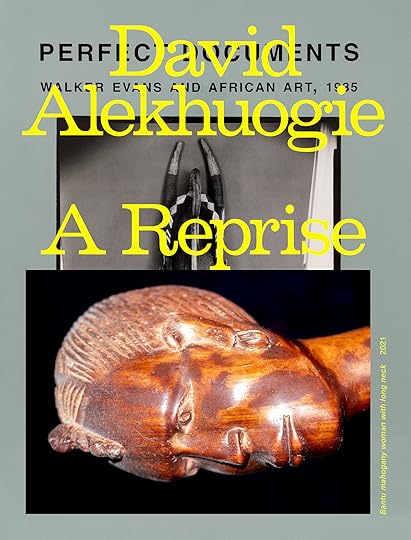

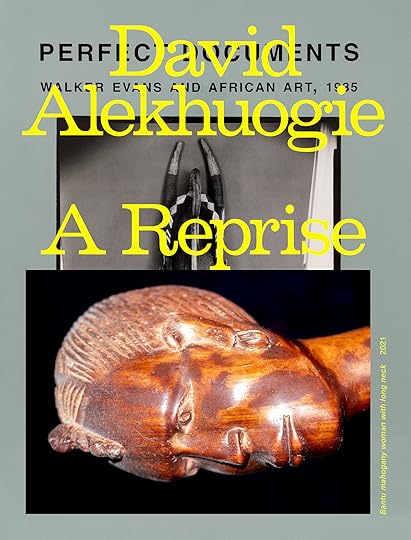

David Alekhuogie: A Reprise 65.00 In A Reprise, David Alekhuogie remixes Walker Evans’s photographs of African art, provoking timely questions about authorship and authenticity.

David Alekhuogie: A Reprise 65.00 In A Reprise, David Alekhuogie remixes Walker Evans’s photographs of African art, provoking timely questions about authorship and authenticity. $65.0011Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

David Alekhuogie: A ReprisePhotographs by David Alekhuogie. Text by Wills Glasspiegel and Wendy A. Grossman. Interviewer Zoë Hopkins.

$ 65.00 –1+$65.0011Add to cart

View cart DescriptionIn A Reprise, David Alekhuogie remixes Walker Evans’s photographs of African art, provoking timely questions about authorship and authenticity.

A Reprise, David Alekhuogie’s first monograph, confronts the intriguing legacy of narrative and authorship behind Western presentations of African art, and poses timely questions about how Black aesthetics are circulated, accessed, valued, and interpreted today. In 1935, Walker Evans was commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, to photograph hundreds of African sculptures for the exhibition African Negro Art. Nearly ninety years later, Alekhuogie began investigating Evans’s images, provocatively remixing them into his own vibrant and multilayered photographic collages. Transposing facsimiles of Evans’s original images onto cardboard or paper structures of his own making, Alekhuogie rephotographs these image-sculptures against striking backdrops—often using East and West African textiles—thereby inviting multiple dimensions of viewership. Alekhuogie’s images draw upon the musical idiom of the reprise—a performance of repetition—and stake a claim to crucial, restorative ideas around Black antiquity by questioning our relationship to what we consider fake or original, art or archive.

DetailsFormat: Hardback

Number of pages: 156

Number of images: 110

Publication date: 2025-08-12

Measurements: 8.58 x 11.1 x 1.75 inches

ISBN: 9781597115742

David Alekhuogie (born in Los Angeles, 1986) is a documentary photographer. He received his MFA from Yale University and BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His work was included in Companion Pieces, the 2020 iteration of the Museum of Modern Art’s biennial New Photography series, and was presented in Men of Change: Power. Triumph. Truth. at the California African American Museum in Los Angeles. In 2019, he was the recipient of the Rema Hort Mann Foundation’s Emerging Artist Grant. Alekhuogie has had solo exhibitions at Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery; Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles; Skibum MacArthur, Los Angeles; and the Chicago Artist Coalition, and has participated in group shows at the Museum of Modern Art, New York; High Museum of Art, Atlanta; Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco; and Regen Projects, Los Angeles. His work has been published in Aperture, Foam, the New Yorker, the New York Times, Time magazine, Vice, and the Los Angeles Times. He is based in Los Angeles.

Wills Glasspiegel is a filmmaker, artist, and organizer from Chicago. He works with the Era Footwork Crew and codirects the nonprofit Open the Circle. He has directed a range of short films, including Footnotes (2021), Icy Lake (2014), Meet the Era (2016), and Bangin’ on King Drive (2015). He holds a PhD in American studies and African American studies from Yale University.

Wendy A. Grossman is an art and photography historian, writer, educator, and curator based in the Washington, DC, area.

Zoë Hopkins is a writer and critic based in New York. She received her BA in art history and African American studies from Harvard University and her MA in modern and contemporary art at Columbia University. Her writing has been published in Artforum, the Brooklyn Rail, Cultured, and Hyperallergic.

Related Content Interviews How David Alekhuogie Navigates the Colonial Past

Interviews How David Alekhuogie Navigates the Colonial Past Hopkins: And also making a living and finding work.

Alekhuogie: Right, yes. That was familiar to me. Also being in graduate school, really struggling with the expectations that I have put on myself as far as my own language and its authenticity. This is another thing that I have a little bit of disdain for, this fixation on Black authenticity from a spectator’s point of view. This is what makes hip-hop special, the realness. You’ve always got to be giving realness. So even if you’re talking in your true voice, you’re writing in your true voice, it comes from a very specific place.

One whole side of my family is pretty heavily gang-related. On the other side, I have gone to primarily private schools almost my entire life. So that causes a really strange dissonance. People don’t understand that the Black experience is not like The Wire. So, that was a serious reckoning in grad school; viewers didn’t have a reference point for the fact that Black interior life is very broad. For example, someone on my critique panel once said that they wouldn’t know I was Black from my images, but those were some of my most diaristic images. There was a need for certain things to point toward authenticity; there was an expectation to perform my Blackness in a way that was convincing. I took this as an opportunity to be a kind of heart-on-your-sleeve, very almost anti-intellectual kind of artist who was, like, “I’m just going to talk about me and my life and my experience.” I was coming to terms with the fact that that did feel like it quenched an appetite people have for looking at a thing that is not their own.

David Alekhuogie, Rene, 2024

David Alekhuogie, Rene, 2024  David Alekhuogie, Scramble for Africa pt. 3/3, 2024

David Alekhuogie, Scramble for Africa pt. 3/3, 2024 Hopkins: Which is exactly the appetite Walker Evans was commissioned to feed: he was photographing these African artworks that had been alienated so thoroughly from their natal context so that they could then be redirected toward an American audience, toward a MoMA audience. Some of the published portfolios were distributed to HBCUs in the US, which is so fascinating to me. It’s like the curators of the MoMA show were maybe trying to wipe their hands clean of the colonial context of the exhibition—the pillage and plunder that made it possible—by making a philanthropic gesture toward African Americans. It also suggests their interest in the relationship between African American culture and continental African culture, or in translating one to another. So, in some ways, the Evans photographs are translational documents. And then your sort of reiteration of his photographs is perhaps a metatranslation or a metatext that overlays that original translation.

Alekhuogie: Yes. Definitely. That’s definitely how I think of it. For a while, I have been interested in web-search criteria for what would qualify as African aesthetics or Black aesthetics, and seeing these images pop up, and being motivated by this idea that if this is a kind of cultural capital that people feel they’ve inherited or essentially feel kinship to, then it is going to be seen through this obtuse angle. It’s not going to be direct. I had started noticing: What does my domestic space look like? My dad is Nigerian. My mom is African American by way of Alabama; she eventually moved to Los Angeles in the 1960s, and she was the first in her family to go to college during this “Black Is Beautiful” movement. In her own self-presentation, she’s invested in the beginnings of what Afrocentrism looks like. So, I’m trying to parse how she’s seeking access to her own cultural capital.

That was my primary motivation—the idea of access to “authenticity” through all of these different channels. I exist on this really strange edge, where I feel simultaneously inside and outside. I’m in a perfect world, right? Somebody might hit my email and be, Hey, do you want to do a project with the museum of whatever to photograph these things, and do a whole show? When I was in my second year at Yale, I met Fred Wilson at a dinner. I became interested in his work, in its sort of interrogation of the institution.

Fred Wilson, Picasso/Whose Rules?, 1991

Fred Wilson, Picasso/Whose Rules?, 1991© the artist. Photograph © Ellen Labenski and courtesy Pace Gallery

Fred Wilson, Guarded View, 1991

Fred Wilson, Guarded View, 1991© the artist and courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art/SCALA

Hopkins: One of Wilson’s works is called Picasso/Whose Rules? (1991). He made a facsimile of Demoiselles d’Avignon and foisted a West African mask on the painting as if to not only call attention to the origins of Cubism, and the appropriative gestures that made that painting possible, but also to overlay and animate a postcolonial critique on its surface. He’s perhaps best known as an institutional-critique artist, but he’s also thinking about art history, about the place, or no-place, that African objects are afforded in Western institutions and the attendant discourse of Western art history.

Alekhuogie: What I find the most interesting is his work about being a security guard—Guarded View (1991).

Hopkins: Yes, that installation with headless Black mannequins wearing guard uniforms from the Whitney, the Jewish Museum, MoMA, and the Met.

Alekhuogie: That sort of approach is very different from how I see the world. I’m always thinking about the archive—books, texts, records, things that I can come to terms with after the fact. Because I’ve been a DJ since I was maybe sixteen or so. That is kind of my baseline for how I think through everything, really; that’s where all this stuff stems from. I’ve also been interested in how the DJ has changed, what the job is, what the task is. Is it your responsibility to represent whatever the zeitgeist is? Is it your responsibility to make people feel familiar? There’s a special moment as a DJ that happens when people in the room feel they’ve been seen, they’ve been recognized. That is what it means to rock a party—making people feel validated and seen.

For me, it all comes down to this stuff that everybody has access to. I wanted to make work from the perspective of an outsider, because I think that to grapple with broken, inherited cultural capital is to always be an outsider. That’s a part of the premise. I’m at my parents’ house now, and there’s tons of African sculpture. There’s always this negotiation around what’s real and what’s not, what’s vintage, what’s valuable—and that’s why I’m always interested in reproductions.

David Alekhuogie, Female Figure “A Reprise,” 2020

David Alekhuogie, Female Figure “A Reprise,” 2020  David Alekhuogie, Heddle Pulley 1/1 Speculative View, 2024

David Alekhuogie, Heddle Pulley 1/1 Speculative View, 2024 Hopkins: We also see that whole question of authenticity and value surface in Western discourses on African art that place a premium on the oldest, most traditional, most “authentic” African artworks. But what’s behind that is a colonial understanding of Africa as purely historical, as unable to participate in some telos of progress toward modernity, as a place without historical development at all, in Hegel’s famous assessment. So, when you have these old objects with patina accumulated over the centuries, the West exalts them as “the most” African, and whatever comes after is often seen as sort of secondary by virtue of its newness.

In A Reprise, you rebut this view by recontextualizing Evans’s black-and-white photographs and setting them against those bright fabrics, which are buzzing with vitality and freshness. Of course, we also get flashes of your subjectivity—your aliveness—with the hands that often appear in the frames. Could you talk about the staging? What kind of atmosphere or environment were you trying to conjure up in these images, and what kind of critique does it make?

Alekhuogie: I started to think about the studio as a performative space, the idea that the photographs were about this interrogation of looking at the original subject matter and trying to imagine what it coul be like in real life, but in an abstract way or in an imaginative way. And also, what it would mean if I took something as my own—and what the implications of that would be like. That’s when I became interested in the original fake. And that came from my trip to Nigeria in 2019, and seeing how people dealt with the value attached to branding. The value attached to knowing for sure that a thing was authentic. “Oh, you like this Prada shirt? I got you. Let me just sew that up for you. I made it. It’s real. What do you mean?” There was a kind of vitality. It wasn’t really about the brand so much as it was using that as a subversive force. If I make a Dutch wax-resist print with the Balenciaga logo all over it, then it circumvents or reappropriates the value associated with that brand. But that is a new thing altogether. I started thinking about that as an economic strategy. If I use material that is loaded in this way, then I can traffic with a kind of discursive strategy.

David Alekhuogie, NP16, O, 2015

David Alekhuogie, NP16, O, 2015  Constantin Brâncusi, Vue de l’atelier, 1927

Constantin Brâncusi, Vue de l’atelier, 1927© Brâncusi Estate and courtesy Peder Lund

Hopkins: There are two markers of authenticity that are being indexed and contested in your images. The first is the sculptures themselves, and the second is the Walker Evans images of the sculptures. There’s the original context of the sculptures, and then there’s the context of their entrance into the realm of the “Western art museum” or into the Western idea of art. You make an intriguing intervention of almost inserting the photographed sculptures back into a three-dimensional language: in your images, Evans’s photographs are pasted onto these wooden cutouts that give them the appearance of being three-dimensional. They’re like sculptures again, casting shadows on the backdrop. They also evoke the appearance of an almost Cubist assemblage, which again reminds us of the way Cubism latched onto a notion of African authenticity. Can you talk about that toggling between two- and three-dimensionality and what that does to these questions around authenticity and deracination?

Alekhuogie: When you become interested in being an artist, you start looking at paintings constantly. I became interested in Cubist paintings, but I was more interested in Cubism as a strategy for looking at the world, and then from there, I started thinking about Dadaist art and Futurist art, and what it meant to try to look at a thing from multiple different angles at the same time, and that being this kind of impossible task. For me, that felt specifically like a photographic problem that people were trying to negotiate through painting. As a sculptor who is trying to represent their sculptures photographically, this is a thing that I immediately noticed when looking at Brâncuși’s work, when looking at Picasso’s work, when looking at Braque’s work, anything that you would look at and think it’s been inspired by African sculpture. The questions with those original sculptures, whether they’re from West Africa or wherever, are: How are they dealing with figuration in this way? Where does that idea come from?

Spread from Virginia-Lee Webb, Perfect Documents (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2000)

Spread from Virginia-Lee Webb, Perfect Documents (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2000)  Still from Chris Marker and Alain Resnais, Statues Also Die, 1953

Still from Chris Marker and Alain Resnais, Statues Also Die, 1953© Revue Présence Africaine

Hopkins: In the catalog essay that accompanied African Negro Art, the curator, James Johnson Sweeney, opens with, “Today the art of Negro Africa has its place of respect among the esthetic traditions of the world.” He then elaborates on its “essential plastic seriousness, moving dramatic qualities, eminent craftsmanship and sensibility to material.” We recognize quite readily the terribly patronizing endeavor of a Westerner declaring the aesthetic viability of African art as such. But honestly, I don’t find the Evans photographs in Perfect Documents to be very artful. Perhaps it’s just the constraints that he was working around, but they don’t do much to illuminate the aesthetic power of the sculptures. For example, they’re really tightly cropped, so there’s not much room for the sculptures to breathe in each frame. They feel almost stuck. Though there are a few works that were photographed from multiple angles, for the most part they are either photographed frontally or completely in profile, which makes it difficult to appreciate more angles in the way that you’re talking about.

I’m reminded of a Chris Marker film that came out in 1953 called Statues Also Die, which argues for the art museum as mausoleum, as a place where objects go to die. He focuses on African sculptures that have been pillaged and then brought into these contexts, where there’s nothing suturing them to the people that made them and the communal contexts that gave them life. The way Evans photographs these objects and freezes them in those tight, lifeless frames feels like another instantiation of that death grip. All to say that your project strikes me as one of reanimating the sculptures or reclaiming their livelihood, perhaps from this project of Western institutionalization. And the fabrics have some role to play in that. The hands have some role to play in that.

Alekhuogie: Well, yeah! Absolutely. That’s such an interesting way to put it. Oftentimes I’m trying to figure out the joinery around whether you’re interested in storytelling or whether you’re trying to be as descriptive or articulate as possible about an event and what transpired—your responsibility to what something looks like or feels like, or the texture of it. What motivates the hiring of a person to document these sculptures? It’s so people have an idea of who made them, and why, and what the history is. At that point, you, as the photographer, become part of the process of objectification. But when the question of how you’ve objectified or exploited the sculptures comes up, you want to pull back and be like, I’m a service provider. When it suits you, your authorship is illuminating. When it doesn’t suit you, it’s like, I just work here. One way around that tension is to tell stories that you’re motivated to tell. When the documentary process becomes more subjective, it doesn’t become more truthful, it becomes more honest.

In my first photography class, there was this idea about being a fly on the wall. But that’s not something that I relate to. There’s this discomfort around documentary photography, this fear or anxiety. Or shame. If somebody sees you while you’re looking, you’ve been caught. I had started to notice that a lot of other artists were approaching documentary practices without this “Don’t look at me while I’m doing this thing.”

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Hopkins: It’s completely voyeuristic.

Alekhuogie: Yeah. That was never how I approached it, even when I was doing all this stuff for music publications. I feel in order for me to do that work and make that work, I had to really be at least somewhat exposed in that process. It doesn’t work any other way for me. The lens is mine.

Hopkins: You have to risk something.

Alekhuogie: Yeah. But also, maybe that has to do with legitimacy and why you access these Walker Evans images. Because if I show up to a place and my bio says I went to Yale, what that means is that I’m attached to the history of Walker Evans. This kind of stuff is a part of how people navigate telling stories. I’m always trying to advocate for people to get where they’re trying to go. I’m at the point in my career as an artist or as an educator where I’m trying to figure out how to mentor people through the process. In many ways, I did a bunch of things just to have the privilege of talking how I want to talk, and people not being, Oh, you don’t know what the hell you’re talking about. Which is wild.

Hopkins: Yeah, it is. The lengths that one must pursue to feel at home in oneself. So much of your personhood feels imbricated in this project though. We feel that sense of risk bristling in these photographs, in the way that you’re involving yourself and placing your hands in the frame. An intentional voice emerges.

Could you also talk about where you sourced those fabrics?

Alekhuogie: A lot of them are from my sister. She was a seamstress and designer. They came from trips to Nigeria. Anytime my dad would go to Nigeria, he would bring her fabric. I had started doing textile research in graduate school. Well, not just textiles, but a lot of these craft arts as having all this storytelling potential in the same way that jazz does. My initial point of view was through mostly West African histories. Growing up, my closest friends were Tanzanian and Kenyan, and so a lot of my interest was in those fabrics as well. A lot of my friends who I met when I first started becoming interested in DJing and poetry, we used to go to these poetry nights in Pomona, California. I initially had seen a lot of these fabrics in popular fashion, whether it was Burberry or Prada or Gucci, and I’m figuring out, Oh, that’s northern Kenyan motifs. And then seeing the history of portrait fabrics in Nigeria. Whereas in the States, you might see the shirts from the swap meet where people have their loved ones and stuff on the shirts, and so I became interested in the potential for the craft arts.

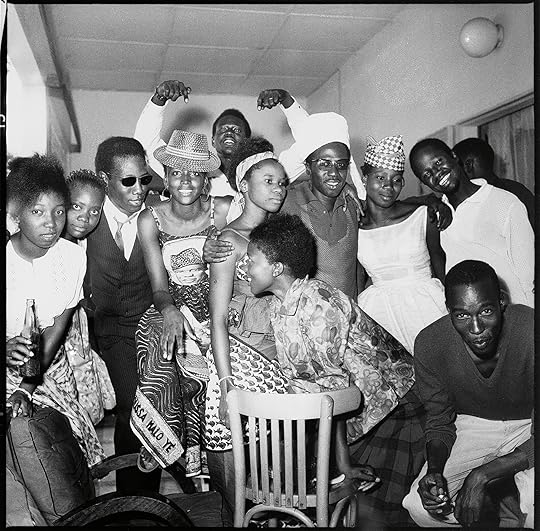

Malick Sidibé, Soirée familiale, 1966–2008

Malick Sidibé, Soirée familiale, 1966–2008© the artist and courtesy the Estate of Malick Sidibé and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

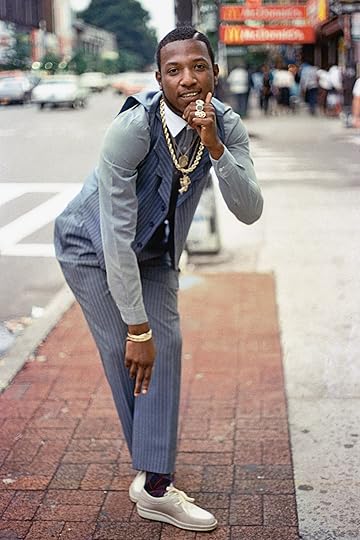

Jamel Shabazz, Rude Boy, East Flatbush, Brooklyn, 1982

Jamel Shabazz, Rude Boy, East Flatbush, Brooklyn, 1982© the artist

Hopkins: So the fabric networks the sculptures into these multiple layers of connective tissue that you’re talking about with your sister and your father, and your own research practices, and your friends from Kenya and Tanzania. It brings all of that into the room with the sculptures. I also love that the fabric is given volume and shape; it’s not just this flat backdrop, it’s actually a very animated form. And then the emphasis on staging, for me, also brings to mind a whole canon of African photography from the 1960s and ’70s, like Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé, who amplified the staginess of their images rather than masking it, which came, for many of them, from an interest in fashion as well. It feels that your photographs are also invoking a kind of lineage in that sense.

Alekhuogie: Oh, absolutely. I love that. I remember when I first came across some of those pictures. The performance and the richness—I felt this kinship immediately. Jamel Shabazz’s work feels like that too. I was like, That’s how I want to photograph people. People feeling good about how they look, how they’re showing up and being represented, and not feeling as though they’ve been caught.

David Alekhuogie, Vince Staples for Justsmile, 2022

David Alekhuogie, Vince Staples for Justsmile, 2022All photographs by David Alekhuogie courtesy the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery

Hopkins: When we last talked, you said something to the effect of, What are the apparatuses by which Walker Evans becomes part of the authorship of Black modernism and Black aesthetics? I want to turn that question back to you because I was stunned by it.

Alekhuogie: Well, for me, it’s hard to run from. It’s central. There’s a performativity of Black aesthetics connected to the idea that you’re always being looked at. There’s a reason why all the funny memes are about Black people—that’s what I love about Black comedy, Black music. It comes from this radical performance. So, it’s hard to avoid Evans’s lens when it comes to African sculpture: it’s a layered, metadialogue about who’s deciding what things look like, what they mean. If you didn’t go to the museum to see the sculptures yourself, you rely on Evans. And his images have influenced what we think about when we think about Black modernism.

One of the things that I’ve been trying to do, for better or worse, in my professional life and my private life, is to figure out all of the things that people love about being Black, the things that people take pride in when it comes to Black aesthetics. A few days ago, I was talking about this concept of swag. Why is it that you might see a working-class Black man, and the hairline is like it was hit by a razor and it was freshly done, and the shoes are spotless. You know what I’m saying? But he might work in a warehouse or something. I feel it’s not controversial to say that Black people probably invest more in this kind of self-beautification. How does that function? You can ask the same question and make it global as well.

One of the things that I noticed in Nigeria was people’s fashioning, how much pride they took in their appearance, and this kind of dandyism. You might see somebody who is very much a corner boy, selling drugs or something, but he literally could be on a runway. On Wednesday, some kids are trying to rob you, but on Sunday they are pristine. I’m trying to figure out these very notable, specific ways that you recognize Blackness.

One of my professors at Yale, the late Robert Farris Thompson, wrote this amazing book Aesthetic of the Cool (2011). He was trying to figure, at least in my perspective, a kind of attempt at a post-racial dialogue around what the aesthetic looks like. What is it about Black people that we recognize as uniquely Black? Does all of this fixation on beauty, or the way beauty is developed or crystallized, come from this feeling of being looked at: I need to be clean; I need to be crisp. To this day, I recognize that it’s much easier for me to look bummy or sort of unhoused or—what’s the term now?—dusty and ashy. It’s much easier for me to make people aware of that than somebody non-Black. When the beard is crisp and the hairline is lined up. I was having this conversation with one of my buddies, about feeling depressed and going to get a haircut and feeling like, You’re back in the game. Don’t count me out. I’m back in there.

Hopkins: Back in the ring.

Alekhuogie: Absolutely.

This interview originally appeared in David Alekhuogie: A Reprise (Aperture, 2025).

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers