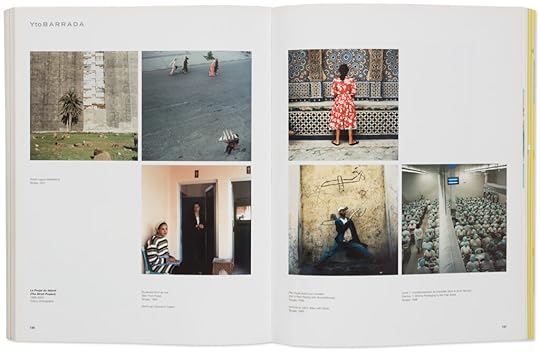

Aperture's Blog, page 15

September 26, 2024

A Collective Portrait of Contemporary Ukraine

On a three-week trip to Ukraine last spring, I experienced the innovative and engrossing exhibition Essential Goods, which felt like a labyrinthine voyage of discovery. It featured 166 photographs by twenty-four younger Ukrainians, the “next generation,” according to curators Isabella van Marle and Sonya Kvasha, of photographers and lens-based artists. This was a relatively rare and extremely welcome exhibition in Ukraine, where the art world has long skewed toward painting and sculpture.

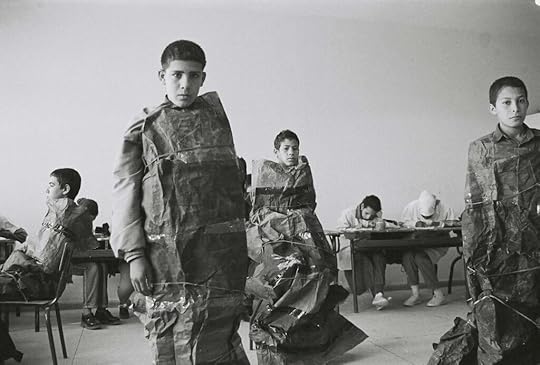

All of the photographs in Essential Goods, which was on view briefly in late May through early June, were made during wartime, many since Russia’s full-scale invasion, on February 24, 2022, and others before. The earliest images dated from 2014, when Russia and its proxies “temporarily occupied” (a term employed all the time in Ukraine) Crimea and parts of both Luhansk and Donetsk in the East. There was an expansive range of subjects, themes, and sites: a bullet-pocked wall in Kyiv, partially demolished buildings, and sandbags in a pile; vibrant nature and a fresh cemetery; youth culture and family life; alienation and memory, loss and connection; among numerous others. Flat-out talent abounded and deep feeling was palpable in this collective, multipart portrait of contemporary Ukraine.

Installation view of Essential Goods, Pavilion of Culture, Kyiv, Ukraine, 2024. Photograph by Sergei Illin

Installation view of Essential Goods, Pavilion of Culture, Kyiv, Ukraine, 2024. Photograph by Sergei IllinThe exhibition’s setting was the glass-walled Pavilion of Culture, in a massive and imposing Soviet-era complex. In 1967, the Pavilion was constructed as an exhibition space, also to celebrate the coal mining industry in the Ukrainian SSR. Soon after the full-scale invasion, it was repurposed as a warehouse for humanitarian aid, while still presenting exhibitions. That a building so emblematic of Russian domination and oppression is now being utilized to assist Ukrainians suffering from renewed Russian aggression is striking. Novel architecture by the Ukrainian firm FORMA allowed for photographs to be displayed alongside boxes of aid supplies.

The exhibition showcased the vitality, intensity, and vision of Ukrainian photographers. (Russia has been suppressing, imprisoning, and murdering Ukrainian cultural figures for centuries.) Near the end of the final class in his Yale University course “The Making of Modern Ukraine” (which is available online), Professor Timothy Snyder quotes the contemporary Ukrainian poet Yuliya Musakovska: “I thank all of the Ukrainians who are continuing to create in times of war.” Essential Goods was full of such creators.

Installation views of Essential Goods, Pavilion of Culture, Kyiv, Ukraine, 2024. Photographs by Sergei Illin

Installation views of Essential Goods, Pavilion of Culture, Kyiv, Ukraine, 2024. Photographs by Sergei Illin

Back in New York, where I live, I met with three of the participating artists—Vladyslav Andrievsky, George Ivanchenko, and Daria Svertilova—on Zoom or WhatsApp. Ivanchenko photographed Izium’s residents; the city was brutally occupied by Russians and later liberated by Ukrainian forces, who discovered a mass grave full of civilians in a forest. Svertilova made distinctive images of scenes especially significant for her in post-invasion Kyiv and Hostomel, the site of the first major battle between Ukrainian and Russian forces. Andrievsky’s pre-invasion photos of gray and alienating Soviet-style, high-rise apartment buildings on the outskirts of Kyiv show the young adults (his peers) living in that environment. In our conversations, which have been condensed and edited for clarity, they each spoke about how the war has changed their lives and work, and how Ukrainian identity itself has been transformed by the conflict.

Daria Svertilova, Artist Sana Shahmuradova in her studio, Kyiv, December 2022

Daria Svertilova, Artist Sana Shahmuradova in her studio, Kyiv, December 2022Gregory Volk: Could you speak about your work that’s in that exhibition, where it came from, what your concerns and motivations were?

Vladyslav Andrievsky: I was showing my main series at this moment, it’s called District (2017–22). This is a series about the outskirts of a big city. Most of the buildings here are constructions from the Soviet era. So, they are buildings of economic changes, of new ideas, but they are not really comfortable. They are concrete, and they became even more raw and dull after the Soviet Union collapsed. And now, this place feels quite depressing. But despite that, many young people were born there, grew up there, and still live there, and I feel a certain tension between these faceless buildings of the outskirts, and the young generation growing up in the internet reality. We are scrolling Instagram, we see a lot of beautiful places, we see that we are the same as our peers in England or the US, but we have a different environment. That is why I was interested in outskirts and in the young generation, and how we can dream about something different. So, it is about a tension between this depressive, concrete, and gray environment and a young generation with bright minds and hearts.

Vladyslav Andrievsky, District view III (Rain), Kyiv, 2020, from the series District

Vladyslav Andrievsky, District view III (Rain), Kyiv, 2020, from the series District  Vladyslav Andrievsky, Prince of his own pattern I, Kyiv, 2021, from the series District

Vladyslav Andrievsky, Prince of his own pattern I, Kyiv, 2021, from the series District Daria Svertilova: The series that was partially presented in Essential Goods was my reflection on the first year of the full-scale invasion. I was working on a long-term project before the full-scale invasion started, and then, all of a sudden, nothing was making sense to me. I was abroad at the time. For seven years, I have been partially living in Paris. Now, I can say that I’m based between two countries, because I have been returning to Ukraine constantly. I spend half of my time here and half of my time in France.

During the first month of the invasion, I was overwhelmed with journalistic images, and I was questioning my practice, my place as a photographer in that context, whether I was ready to do journalistic photography, or if I needed some more time to reflect and create other imagery. When I came back to Ukraine after the invasion, it was August 2022, so I started to take pictures that were kind of like what everybody was taking. I wanted to go to liberated towns around Kyiv. I wanted to photograph the remains of the destruction.

Daria Svertilova, Invisible museum, Kyiv, 2023

Daria Svertilova, Invisible museum, Kyiv, 2023And then, throughout the first year, between 2022 and 2023, I was focusing on things that I found different every time I came back. I called the series Irreversibly Altered because everything was kind of altered to me. I constructed it around a notion of a dream, because since the full-scale invasion started, I was dreaming a lot about the war.

It doesn’t have the classic narration of a documentary series. It’s really like a puzzle of impressions of some parts of the reality that I would find every time I would come back. For example, in December ’22, there were blackouts. In summer, there were still ruins in the Kyiv Oblast, but then they were quite quickly cleaned away. I also photographed some women members of the military. My series, it was really like reactive photography. It was some kind of sublimation of the things that I was living through.

George Ivanchenko: I’m not an art photographer. I work with reportage. But for this exhibition, I sent the pictures of people who were living together, in a building, during the occupation of Izium. I just love these people; we speak a lot. I lived there in a flat because I was working with volunteers. I started to make pictures about these people. I see the simple soul of the East of Ukraine and in Izium it’s special, it’s not like in Donbas, it’s not like in Kharkiv.

George Ivanchenko, from the series 13IUM, Izium, Donbas region, Ukraine, 2024

George Ivanchenko, from the series 13IUM, Izium, Donbas region, Ukraine, 2024

Volk: How did you come to photography? Did you first explore other mediums, or have you long known that photography is your calling in art?

Andrievsky: First I wanted to be an artist. I used to draw, but then I discovered photography when my mother gave me a camera and a few rolls of film. From that point, I started to document my life during summer camp. That’s how I got involved in photography. I started to buy some photography magazines, to watch some documentaries. Later, I met Viktor Marushchenko, a Ukrainian master of photography and a great teacher. I was studying in his photography school for about three or four months, and that experience changed me forever. That was a very, very big influence on me as a person and as a photographer. Unfortunately, Viktor died in 2020, and I think this was a huge loss for the future of Ukrainian photography.

Svertilova: I took painting classes as a kid. I was a teenager when I started trying to do photography, and it was a kind of hobby. My grandfather gave me this old Soviet film camera, and I was also experimenting with just taking pictures on film. Basically, it all started at school, and at some moment, I was taking pictures of my classmates and they were encouraging me to continue. And progressively, I started to take photography more seriously. I met some people older than me who would advise me about books, some photographers to look at, and that’s how it developed.

When I was 21, I entered an art school in France, and basically, since then, I had access. I feel quite privileged to have access to photography events, to exhibitions, to bookstores. And it’s true that in Ukraine, we are quite limited with all this photography market, let’s say, because photography is not really taken seriously here. It is starting to be taken more seriously, but we’re not very supported by institutions like it is in Europe, or in the US.

Ivanchenko: I had been studying journalism for one year in Lviv when the big invasion came. The first day I understood, I can do this now or never.

George Ivanchenko, from the series 13IUM, Izium, Donbas region, Ukraine, 2024

George Ivanchenko, from the series 13IUM, Izium, Donbas region, Ukraine, 2024Volk: How has the war affected you personally and as lens-based artists? Have your work or motivations substantially changed? I’m guessing that none of you ever imagined you would be wartime artists.

Svertilova: It’s a big, big question. We have been speaking about it with a lot of friends and we’re still speaking about it. We are Ukrainians, we were born here, raised here, and even if some of us are working abroad, partially, we still identify ourselves as Ukrainian artists. So, basically, all the work we’ll do, it’ll be war-related in some point.

The full-scale invasion, it stole a lot of things from us, but it also stole our ability to speak about other non-war-related subjects. The war has been taking place since 2014, but still, we had more freedom to speak about some things that were, maybe, less tragic, let’s say. Now, it’s so overwhelming.

I believe that art is political, and I believe that the work we do is political, because we witness something, we work with the medium of art photography or documentary photography. We’re not making collages, or completely abstract things, so we work with the reality, and the reality is tragic. I believe that my personal work changed. I don’t see now a possibility to do work that is completely un-related to the invasion, or to politics somehow. That can be tough, sometimes, because I don’t feel like I’m able to do the work that is purely aesthetic.

George Ivanchenko, from the series 13IUM, Izium, Donbas region, Ukraine, 2024

George Ivanchenko, from the series 13IUM, Izium, Donbas region, Ukraine, 2024Andrievsky: It is also quite tough for me as well, because I have not been practicing photography since February. I don’t understand how to react to this reality today, as I see that a lot of works that artists are doing now in Ukraine, they are more documentary reflection of reality. And I’m not really sure that I want to be a documentary photographer.

At some point, I decided just to live through this experience, and maybe, in the future, I will try to say something, with distance. But, of course, I take photographs on my phone and I somehow experiment with Xerox, because I like this filter that Xerox does. It is like broken images. It is not smooth, it is not perfect, and it somehow reflects and shows this current time.

Ivanchenko: Gregory, I can’t say I’m an artist.

Volk: Just wartime photographer?

Ivanchenko: Yes, it’s like that. The war makes faster all the processes in your life and all relationships with people. You change many times during these three years. You want to find something, you learn, you do stupid things, you study, in your way. In the first week, I went to Kyiv from Lviv, and for one and a half years, I didn’t have a room, a house, someplace where I stay and keep all my things. I have everything in a bag, my camera, and then it’s another city, it’s the front line. It’s south, it’s east. You just live somewhere, sometimes without money. You don’t know exactly what you do, but you just feel it and you understand. It’s a lot of experience, a lot of really important moments with this big pain.

Daria Svertilova, Archangel Michael—protector of Kyiv, Kyiv, 2023

Daria Svertilova, Archangel Michael—protector of Kyiv, Kyiv, 2023  Daria Svertilova, August in Hostomel, Kyiv Oblast, 2022

Daria Svertilova, August in Hostomel, Kyiv Oblast, 2022 Volk: The first night I arrived in Kyiv, Russia sent fifty-three Iranian-made Shahed drones and five missiles, including at Kyiv, and there was a big explosion not far away from me. And then, the next morning, I went to your innovative show, in which humanitarian aid was exhibited alongside your works. And I understand that the Pavilion of Culture, since the start of the full-scale invasion, has been used to store and distribute humanitarian aid. How did you feel, as artists, as photographers, showing in that context?

Svertilova: I knew Isabella van Marle, the curator, from a Pictures for Purpose fundraiser, and she contacted me to ask if I was willing to participate. Initially, she planned to organize a show in Paris. And then, she said that the show would be in Kyiv. There are not lot of photography exhibitions taking place in Kyiv right now. The exhibitions that are there are mostly photojournalistic ones, and art photography is very underrepresented, in my opinion. It was right to use this space, because it’s like an old Soviet pavilion. The humanitarian aid was part of the context, because we were speaking about war-related subjects, even if they’re non-explicit. I think I wouldn’t like to see these pictures in a white cube gallery space. For me, the choice was right for the time we showed this work.

Andrievsky: I agree with Daria, because it is how everything is now, it couldn’t be separated. We live in this time where everything is all together—war, life, death, and so on. It is a reflection of today.

Related Items

The Photographers Who Showed the Whimsy and Eros of Ukraine before the War

Learn More[image error]

An Uncanny Chronicle of Ukraine, Before and After the War

Learn More[image error]Volk: I’m wondering about the role of artists in Ukraine. One thing I know is that artists, poets, and writers have long been essential for Ukraine and Ukrainian culture, and have often suffered greatly at the hands of Russia. But right now, there is resurgent interest in Ukraine, in contemporary art and literature, and I hope this extends to photography. Can you talk a little bit about your audience, or what you want your works to do in the world in terms of connecting with other people?

Svertilova: For me, personally, it’s horrible to say, but the only positive thing of what’s happening is that all foreign countries, finally, started to distinguish who are Ukrainians and who are Russians. What is happening now is very brutal process of decolonization. Basically, we had the same cultural context with Russia for a long time. I remember, when I was a teenager, we would watch Russian TV series because we had Russian TV channels.

It’s crazy how tricky it was that so many people were identifying themselves with a Russian context. And now, we realize that it’s totally different, and it was artificially-implemented during Soviet times. And also, there is this complex of inferiority, that we were growing up with the idea that Russian language is better. It’s equivalent to you being educated that Russian culture is better, that everything is better.

What’s happening now, it’s very complex. The war is not just about life and death. It’s also about moral choices and a lot of cultural processes taking place at very accelerated speed. In a very, very short amount of time, like in three years, we are completely changing our mind, and understanding who we are.

Vladyslav Andrievsky, Corner, Kyiv, Ukraine, 2021, from the series District

Vladyslav Andrievsky, Corner, Kyiv, Ukraine, 2021, from the series DistrictVolk: And art is an important part of that.

Svertilova: Absolutely. In this context, I would like to bring attention to some things that matter to me through my own prism, because I’m not a war photographer. I don’t see myself going to trenches with soldiers and taking journalistic pictures. I don’t feel that’s my place, because there are so many people who are doing it much better than I would do.

I’m more in slow documentary photography, processing things and speaking to people and also living through all this experience. For me, photography is always about this double-sided, let’s say, position, like you are supposed to be a bit insider to understand the context and to treat the subject in the right way. But also, you are supposed to have this distance. I’m trying to balance between these two because I’m trying to reflect on things which I’m a part of, but at the same time, I try a bit to take a step away to understand what’s it all about. And sometimes, it’s overwhelming.

Andrievsky: I also think that it is good for us that we investigate a lot of Ukrainian culture now. There are not many exhibitions of photography, but we have a lot of art exhibitions of the masters of earlier times. It is really important to be an artist, and I think we should not just be artists, but be Ukrainian artists.

We need to be supported by the institutions. We need education programs for the young generation. Unfortunately, our universities are very Soviet. They have a very strict vision of what is beautiful, what is not beautiful, what is right, what is not right. We need new programs, new visions, new names. It’s very important to talk about Ukraine abroad and about culture, but it’s even more important to do exhibitions and programs here to raise and educate a new generation who will know what it means to be Ukrainian and what Ukraine is.

George Ivanchenko, from the series 13IUM, Izium, Donbas region, Ukraine, 2024

George Ivanchenko, from the series 13IUM, Izium, Donbas region, Ukraine, 2024All photographs courtesy the artists

Volk: George, what is your role as a photographer in Ukraine now? You took photographs in Izium when it was occupied. The Russians left a mass grave, you’re photographing people who lived there, who lived under occupation and now are liberated, so your photographs are important.

Ivanchenko: It’s important because you can give information via your pictures, and they’re also part of history. People really see this and they will think about it.

Essential Goods: Ukrainian Photography Now was on view at the Pavilion of Culture, Kyiv, Ukraine, May 23–June 6, 2024.

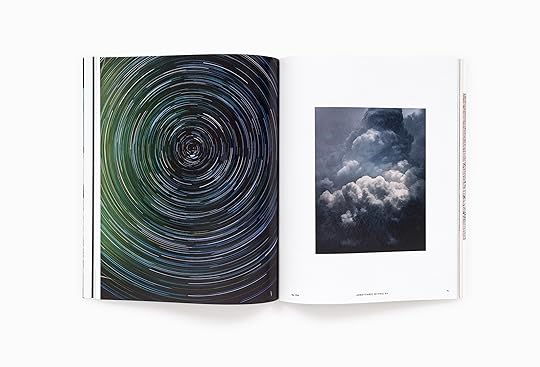

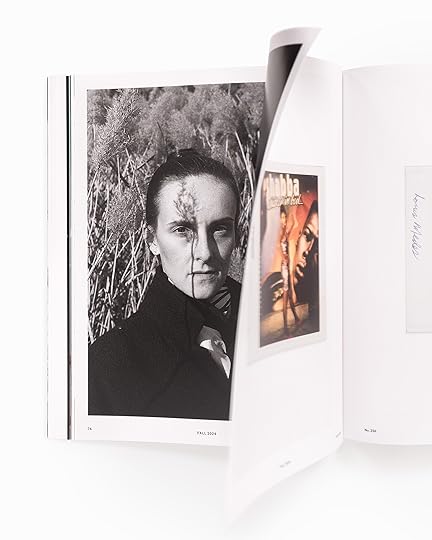

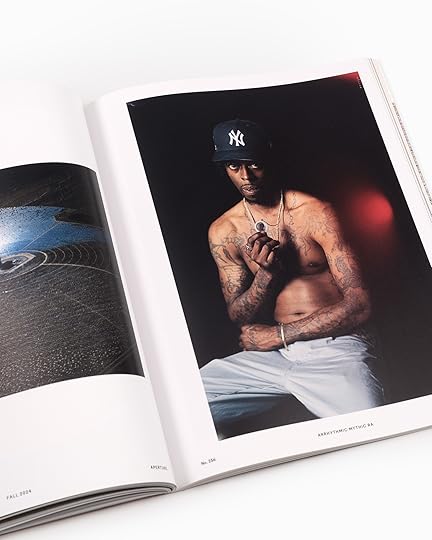

September 25, 2024

Announcing the Winners of the 2024 Creator Labs Photo Fund

Google’s Creator Labs and Aperture are thrilled to announce the winners of the 2024 Creator Labs Photo Fund—an initiative providing financial support and visibility to encourage artists at formative moments in their careers. Inaugurated in 2021, the Creator Labs Photo Fund is now in its third season, continuing its mission of supporting image makers. In partnership with Aperture, Creator Labs Photo Fund provides one-time $6,000 grants and a Google Pixel device to thirty artists working in photography and lens-based practices.

The winning artists of this year’s Creator Labs Photo Fund are:

Farah Al Qasimi, Luke Austin, Bruce Bennett, Morganne Boulden, Harlan Bozeman, Oyè Diran, Brayan Enriquez, Camille Farrah Lenain, Naima Green, Pia Paulina Guilmoth, Shravya Kag, Mary Kang, Brian Van Lau, Spandita Malik, Dom Marker, Ana Rosa Marx, Will Matsuda, Steven Molina Contreras, Rachelle Mozman Solano, Mathilde Mujanayi, Anh Nguyen, Nathan Olsen, Obinna Onyeka, Andina Marie Osorio, Tanner Pendleton, Chris Perez, Mateo Ruiz González, Jennifer Sakai, Rachel Elise Thomas, and Jaclyn Wright.

“Aperture is excited to recognize the depth and rigor of these thirty selected artists,” notes Brendan Embser, senior editor at Aperture. “Our partnership with Google on the Creator Labs Photo Fund remains central to our mission to support artists and shape critical dialogues about photography today.”

Below, read more about this year’s winning artists.

Farah Al Qasimi, Marwa Braiding Marah’s Hair, 2020, from the series Brotherville

Farah Al Qasimi, Marwa Braiding Marah’s Hair, 2020, from the series BrothervilleFarah Al Qasimi

Dearborn, Michigan, is home to the largest concentration of Arabs outside the Middle East. Its first immigrants were workers for the Ford Motor Company, and successive generations arrived from Iraq, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, and Yemen, many fleeing conflicts fueled by US intervention. Farah Al Qasimi first visited the city in 2019. There she met people wrestling with an ever-growing presence of anti-Arab sentiment. “Since then, I have tried to find excuses to return,” she says. Brotherville is a product of this sustained engagement. Al Qasimi grew up between the UAE and the US, and her photographs investigate the anxieties of immigration and diaspora in a post-oil world. In one image that slips between the metaphorical and documentary, a woman looks out at the Marathon oil refinery, a major pollutant in the area, framed between its signage and two McDonalds cups. “I have embodied that duality for all of my life,” says Al Qasimi, on balancing US assimilation with preserving her own identity, “and this is what draws me to this place again and again.”

Luke Austin, Untitled, 2020, from the series A Dislocation of Time

Luke Austin, Untitled, 2020, from the series A Dislocation of TimeLuke Austin

Near the end of 2020, stuck at home, Luke Austin experimented in the studio. Gathering self-portraits from men he followed on Instagram, Austin printed the images on paper, cut out the figures, and began a process of rephotographing the photo-sculptures he created. The two-dimensional became three-dimensional, then two-dimensional again. “There is something hollow yet rich about the silhouette cast from a cutout image of a person,” Austin says. “This work explores that, encouraging the viewer to look beneath the surface.” The series title, A Dislocation of Time, comes from a David Wojnarowicz journal entry; years later, it feels apt to the situation in which Austin made these images, as he reflected on a time-consuming process of photo-making, collaborating with men he met online while quarantining during a global pandemic. “I’ve spent the last few years thinking about the people who aren’t in my life anymore,” he says, “and I think subconsciously that showed up in the ghostly figured shapes and shadows in the works.”

Bruce Bennett, 4, 2021, from the series Love II

Bruce Bennett, 4, 2021, from the series Love IIBruce Bennett

The relationship between the photographic gaze and Black love is central to Love II, a series by Chicago-born and New York–based artist Bruce Bennett. Through black-and-white portraits and self-portraits with his partner, Bennett brings his imagined viewer into an intimate, egalitarian conversation. In a careful subversion, the subjects of this invited gaze—who almost always look back—reclaim agency. They become coconspirators in a style of representation that demands their presence. “I’ve always dreamed of seeing myself in the third-person perspective,” says Bennet. In one image, Bennett sits with his partner in their bathtub, her hands wrapped around his forehead as he points his lens to a mirror that reflects the scene. While Bennet’s head cranes lovingly toward her, casting a shadow on the bathroom wall, her eyes remain fixed on us. This charged exchange, between them and us, is a fulcrum of Bennet’s work. “We want you to feel the contact and energy,” he says.

Morganne Boulden, Butterfly, 2021, from the series When Flies Sit Still

Morganne Boulden, Butterfly, 2021, from the series When Flies Sit StillMorganne Boulden

From Robert Frank to Ryan McGinley, the allure of the open road permeates American photographic history. Morganne Boulden’s When Flies Sit Still contributes to this rich lineage with the eerie solitude of the post-pandemic era. Since 2020, Boulden has made multiple cross-country road trips, intuitively capturing various scenes and friends along the way, in North Carolina, Missouri, Colorado, Nevada, and more. The result is a photographic map of disillusioned young America, though Boulden thinks of each photograph as the conversation surrounding it rather than a singular moment in time. “Times have been changing very rapidly,” she says. “Being able to have that conversation, and to capture a moment when that conversation is happening, is something that helps me deal with everything.” In Michigan, she photographed a young woman at a shooting range, a butterfly perched on her finger as a man aims and fires in the background, a beautiful moment of quiet amid the noise.

Harlan Bozeman, Wilt, 2021, from the series Out The E

Harlan Bozeman, Wilt, 2021, from the series Out The EHarlan Bozeman

The Elaine Massacre is often overlooked in US history. In 1919, a gathering of formerly enslaved Black sharecroppers organizing for fair payment was disrupted by several white men, one of whom was killed. The ensuing racist hysteria led to a white mob, including federal troops, indiscriminately killing hundreds of Black farmers and their families. “As someone who was raised in Arkansas, I was upset that I had never learned about what took place there so long ago,” says Harlan Bozeman. His series Out the E captures how this history continues to shape the lives of contemporary residents of Elaine, where the school district closed in 2005. Bozeman’s role exceeds photography; he is also a facilitator and collaborator. For the past two summers, he has been working with youth at the Elaine Legacy Center, the former elementary school, where he uses photography as a tool for education and self-expression. “I’m helping to ensure that the legacy of Elaine is preserved and carried forward,” says Bozeman. “There is now more to this project than making images.”

Oyè Diran, Shadow Embrace, 2024, from the series Rêve Bleu

Oyè Diran, Shadow Embrace, 2024, from the series Rêve BleuOyè Diran

“To me, the color blue represents the emotional and spiritual experiences I’ve had in my life,” says Oyè Diran, whose series Rêve Bleu unfolds like a visual poem, capturing the dimensions of the color. Born in Lagos and based in New York, Diran cut his teeth in the worlds of portraiture and fashion, publishing with several international brands, including Vogue Italia, CNN Africa, Kenya Airlines, and Afropunk. However, he thinks of his work against a much broader canvas of conceptual photography. Diran’s expansive blue tones endow his subjects—mostly people of color—with a regal grace. Poppy pods, silhouettes, shadow play, and geometric postures all elevate the emotional register of his images. These arrangements come from “an exploration that has required deep introspection,” says Diran. “In essence, I am exploring the human experience.”

Brayan Enriquez, Untitled (Self-Portrait), 2023, from the series And Taste the Dirt Below

Brayan Enriquez, Untitled (Self-Portrait), 2023, from the series And Taste the Dirt BelowBrayan Enriquez

Born in the United States to undocumented parents who had emigrated from Mexico only a few years earlier, Brayan Enriquez grew up knowing only pieces of their story. “Sometimes that history can go unsaid—can get lost in time,” he says. And Taste the Dirt Below documents Enriquez’s process of uncovering his parents’ odyssey through portraiture and video collaborations with his immediate family. Enriquez obscures some of his sitters, either by blurring them, covering their faces, or photographing them facing away from his camera. “The familiarity I had with my parents hindered me in picture making,” he says. “I needed to create some distance to approach this subject matter constructively.” Distanced as they are, the photographs are unmistakably intimate views into the domestic life Enriquez’s parents made in Atlanta. Shoes sit idle in an entryway, keychain photos hang next to a printout of an ultrasound. Set within his childhood home, And Taste the Dirt Below creates a refuge for Enriquez to tell his own story.

Camille Farrah Lenain, Uncle Farid and the Mediterranean Sea, 2020, from the series Made Of Smokeless Fire

Camille Farrah Lenain, Uncle Farid and the Mediterranean Sea, 2020, from the series Made Of Smokeless FireCamille Farrah Lenain

How to represent those who have been made invisible? How can portraiture address the endangerment visibility also creates? Made Of Smokeless Fire, by the French Algerian photographer Camille Farrah Lenain, represents the experience of queer Muslims in France against photography’s historically troubled dynamic of visibility and invisibility, power and consent. For Farrah Lenain, who now lives between Paris and New Orleans, what we don’t see is as important as what we do. Her sitters are often anonymous, while their presence and testimony takes center stage. “My approach to portraiture has a double function,” she says. “It hides the identity of the participants for their own safety and comfort, but also sheds light on the experience of invisibility in society and religion.” The project has a personal origin. It began as an homage to her beloved uncle, who lived with diabetes and AIDS and died in 2013; amid her portraiture, Farrah Lenain interjects archival imagery of him, drawing a broader connection. In a refusal to categorize what it means to be queer and Muslim in France, she instead asks: “What does silencing an identity look like?”

Naima Green, Untitled (Riis), 2023, from the series I Keep Missing My Water

Naima Green, Untitled (Riis), 2023, from the series I Keep Missing My WaterNaima Green

“The beach and being near the water have always been a site of freedom, a safe space, especially during the height of the pandemic,” says Naima Green. Photographing friends and collaborators within her community, Green navigates the symbolism of water, finding and pushing its boundaries in order to better understand queer life in the contemporary world. Her series I Keep Missing My Water spans locations, from the ocean at Jacob Riis Park to a constructed studio set. “I started at the edge of large bodies of water and moved into smaller vessels: faucets, carafes, boiling pots of salty water, a bowl on the altar, a glass,” says Green, “places around domestic spaces that are mobile through different homes and thresholds.” Green’s camera often catches an embrace, on the studio floor or on the beach, waist deep in the tide, one woman’s hand resting on another’s pregnant figure. Throughout, a sense of community prevails—fluid in the spaces Green inhabits, but preserved in each moment of her photographs.

Pia Paulina Guilmoth, we built a flower, 2022, from the series flowers drink the river

Pia Paulina Guilmoth, we built a flower, 2022, from the series flowers drink the riverPia Paulina Guilmoth

Maine-based photographer Pia Paulina Guilmoth’s series flowers drink the river reflects on her deep, evolving, and complex relationship to her surrounding landscape and community. “I live in a rural, predominantly right-wing town,” says Guilmoth. “When I started (medically) transitioning last year my relationship to this place, this landscape, changed drastically.” Her compositions present a transfixing, dreamy utopia, where the cover of night allows phenomena that teeter on the knife-edge of reality—moths circle the waxy drip of a lone candle, five hands stretch out a glimmering spiderweb, luminous figures of dust emerge on a dirt road. Photography is meditative for Guilmoth, who uses a large-format camera and often needs several rounds of trial and error to get each living element to remain in frame and focus. Her photographs have evolved with her. “I started this series before I started my transition,” says Guilmoth. “This work was a release of emotions and compassion for life and for living my truth.”

Shravya Kag, there, there, 2024, from the series వెళ్ళొస్తా (vellostha)

Shravya Kag, there, there, 2024, from the series వెళ్ళొస్తా (vellostha)Shravya Kag

Shravya Kag navigates two worlds: her adopted home in Brooklyn and Vijayawada, her hometown in southern India. “It takes 24 hours, door-to-door, to travel from the current version of myself to an old, familiar one in my hometown,” she adds. Kag’s evolving genderqueer identity and its expressions stretch across this iterative journey, and form the focus of her series వెళ్ళొస్తా , which translates, in her native Telugu, to “I will go and come back.” Over the last four years, and several trips, Kag has attempted to observe—with great care and strength—how a place can form a person, and then question how a person might exert agency over that formation. In negotiating the internal and geographical split between her current gender nonconforming self and a nostalgic, traditionally gendered self, Kag uses photography to construct a space for reflection. We see her trying on a chudidar for a friend’s wedding, her father hidden behind the morning paper, her mother in the middle of prayer. Each photograph contributes to a larger picture, where the goal is not just reconciliation, but understanding, and more importantly, compassion.

Mary Kang, Korean Sword Dance, 2024, from the series Norigae

Mary Kang, Korean Sword Dance, 2024, from the series NorigaeMary Kang

Growing up in Austin, Texas, Mary Kang and her mother would make frequent grocery trips to the neighboring city of Killeen, which had a significant Korean community. Years later, in college, Kang studied the history of the women who immigrated to the United States—including to Killeen—after the Korean War, and their experiences of racial stereotyping and oppression. These women were pejoratively called “military wives,” and presented as vulnerable and dependent, obfuscating their role as resilient community builders. On seeing a tongue-in-cheek resurgence of the term among TikTok fans of the Korean boy band BTS, Kang became curious about the power of existing media narratives and the role of historical amnesia. In Norigae, Kang documents the personal stories of a group of military wives practicing and performing traditional Korean dances in Killeen and across Texas. “In mainstream journalism, we are often consumed with depictions of marginalized communities suffering,” say Kang. “My goal is to share their stories in a way that honors them beyond the stereotypes and limitations imposed by society.”

Brian Van Lau, Family Portrait, 2024, from the series We’re Just Here For the Bad Guys

Brian Van Lau, Family Portrait, 2024, from the series We’re Just Here For the Bad GuysBrian Van Lau

When his father was diagnosed with brain cancer in 2019, Brian Van Lau traveled from the US to Vietnam to see him. Their relationship had been fractured since Lau was young, and the trip began a years-long visual investigation of a complicated family history. We’re Just Here For the Bad Guys comprises photographs from their time in Vietnam with images of Lau’s family in the Pacific Northwest and his birthplace, Hawaii, and documents from the family archive. A distinctly coherent mosaic of black-and-white photographs collapses decades of history into one ongoing narrative. (Lau’s father began treatment, but he died in 2020.) “I had always framed the project as both a moment of catharsis and as a moment of condemnation,” says Lau. Finding parallel images across time to illustrate his father’s return into his life, Lau interrogates what this relationship means to him.

Spandita Malik, Noshad Bee, 2023, from the series Jāḷī

Spandita Malik, Noshad Bee, 2023, from the series JāḷīSpandita Malik

Spandita Malik’s collaborative series of embroidered photographs, Jāḷī, gives a voice to women in India who have survived gendered violence. For the past five years, Malik has worked within women’s shelters across the country to make portraits, which are then printed onto local homespun muslin and embroidered by the women in the images. The results are distinctly personal works of art—Malik’s portraits become a canvas for each woman to express an individuality that is often stripped away in discussions of domestic abuse survivors. Malik was in graduate school when she made the images, and realized that her photographic education leaned strongly on a Western perspective. “I started being very conscious of that when I started photographing the women,” she says. “I might never be able to get rid of the bias that I have in photographing my own country. What I can do is start sharing power in creating a narrative.”

Dom Marker, Fynn + Maksym + Stas, 2023, from the series Borderlander

Dom Marker, Fynn + Maksym + Stas, 2023, from the series BorderlanderDom Marker

Soon after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, Dom Marker returned to the country his family left when he was just three years old, primarily to volunteer with frontline humanitarian organizations. Over time, with a patient eye and an instant Polaroid SX-70 camera, Marker began to make portraits and photographs of the scenes around him. “There was no shortage of journalists in the region,” he says. “The idea was that maybe we could still make our own family album, for me and my friends, as defiance against the void.” Marker’s images challenge traditional conflict photography. The photographs in Borderlander and their subjects—Fynn, Maksym, and Stas holding flares against the night sky; Alex and Georgie leaning against one another, shirtless torsos smeared with ink—each capture an authentic human relationship. Pointing to various influences, from Boris Mikhailov’s Polaroid photographs, to the Kharkiv School of Photography and Susan Sontag’s writing on conflict photography, Marker understands the context of these photographs within this historical moment. “Witnessing is no longer enough; participation is necessary,” he says.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Ana Rosa Marx, Unspeakable, Unknown, 2024, from the series The Aphrodite

Ana Rosa Marx, Unspeakable, Unknown, 2024, from the series The AphroditeAna Rosa Marx

Ana Rosa Marx is drawn to the role of the trickster. “The trickster in mythology is someone who uses their knowledge to disrupt, to challenge and disobey normative structures of hierarchy and power,” says Marx, who grew up between Chicago and Havana. Her series The Aphrodite presents a speculative, mixed-media account of the cruising scene at a fictional lesbian porn cinema in 1980s Times Square, reconstructing an imagined history where an actual one was erased. Marx draws from real locations, such as the Fair Theater in Queens, the last porn cinema house in New York. Her cast of characters is people from her own life, and her restagings take on “a kind of performance documentation,” featuring photography and ephemera that ask what vision a ritual of reimagining might offer for more inclusive futures. Marx’s portrayal engages with a tradition of thinkers and artists who came before her, including Samuel R. Delaney, David Wojnarowicz, Saidiya Hartman, Walid Raad (another trickster), Isaac Julien, Janet Cardiff, Zoe Leonard, and more. “I want my work to stoke that inner-child desire to believe,” says Marx, “for fantasy to be a place of rapture.”

Will Matsuda, Myojo-in Temple, 2023, from the series Hibakujumoku

Will Matsuda, Myojo-in Temple, 2023, from the series HibakujumokuWill Matsuda

Will Matsuda’s grandmother never talked about Hiroshima. Recently, his family uncovered documents showing that members of her family had died in the bombing. Hiroshima carries its history in moments trapped in light—the photographer Kikuji Kawada began his seminal work Chizu documenting the permanent shadows left on walls by the bomb. In Hibakujumoku, Matsuda sets forth on a new path. The project’s title refers to the gingko trees that survived the bomb and still stand in the city. “There is a strong component of ecological life—trees, animals, rivers,” he says, “that to me speaks to something other than sadness.” In a poetic and abstracted depiction of his family history and the horror of the bombing, Matsuda photographs Hiroshima with a sense of wonder and hope amid the overwhelming context of history. “More than anything, I was thinking about finding a connection to this place for myself,” he says.

Steven Molina Contreras, Trinity, El Salvador, 2021, from the series Adelante

Steven Molina Contreras, Trinity, El Salvador, 2021, from the series AdelanteSteven Molina Contreras

In photographs made between El Salvador and New York, Steven Molina Contreras’s Adelante portrays a tender view of a family and culture caught between two places, enmeshed in the global story of immigration. Primarily told through softly toned portraits, the narrative of Adelante is its direct English translation: Forward. Born in El Salvador and raised on Long Island, away from much of his extended family, Molina Contreras does not shy away from emotion. His portraits are as familiar as family snapshots: two boys sprawled on a tile floor; an uncle leaning casually against a cabinet. “I’m moved by the intimacy and awkwardness that portraiture allows one to experience and process,” he says. In a self-portrait, he raises one hand slightly, his face covered by the camera and framed inside a mirror on a pink wall. On its own, each image does not attempt to speak to immigration, but as a whole, the series projects a sense of distance, contracted in the intimate space of the portraits. The only direction is forward.

Rachelle Mozman Solano, Im not going to tell you that Mexicans are the best people on the face of the earth, 2021, from the series Venas Abiertas

Rachelle Mozman Solano, Im not going to tell you that Mexicans are the best people on the face of the earth, 2021, from the series Venas AbiertasRachelle Anayansi Mozman Solano

Rachelle Anayansi Mozman Solano’s Venas Abiertas transforms written text into staged photographs. Each image visually reinterprets literary or scholarly source material to depict the effects of policy on individual and collective bodies. In one, a woman’s body splits a cutout of a redwood tree, referencing the redwoods’ early conservators’ ties to eugenics movements in California. The project’s title comes from Eduardo Galeano’s book Open Veins of Latin America (1971), which deals primarily with US imperialism across the continent. For Mozman, the work is both personal and political, stemming from anti-Latino sentiments that came into prominent view during the 2016 election. “I wanted to continue with using historical text in a journalistic way,” she says, “to address the history of anti-Latinx views in our nation and parallel this with a mirroring sentiment today.” Mozman arranges, repositions, and collages her collaborators and various props. The resulting photographs play with viewers’ expectations of studio portraiture, offering an expanded site of historical negotiation.

Mathilde Mujanayi, A Ma Mère Qui Me Regarde Avec Des Fleurs Dans Ses Yeux, 2023, from the series As Close As I Can Get To You

Mathilde Mujanayi, A Ma Mère Qui Me Regarde Avec Des Fleurs Dans Ses Yeux, 2023, from the series As Close As I Can Get To YouMathilde Mujanayi

Bringing together self-portraits, still lifes, and staged scenes, the Congolese American photographer Mathilde Mujanayi navigates her identity as an immigrant and a woman living in America for the past twelve years. Her abstract images—a smashed Coke bottle, fabric half buried in sand—read as fleeting memories that Mujanayi searches for meaning, while others, such as a nude self-portrait under a large American flag, are more direct. “How can I close the distance between my land and I, my identity and I, my mother and I?” asks Mujanayi. “What acts can I perform to get me close to that?” As Close As I Can Get To You shows the artist using photography to reach back toward her mother and the culture she left behind. In one self-portrait, Mujanayi, wearing a Congolese fabric skirt, carries a water jug over her head as it drips down her back. “The Congo that I left is not the same Congo that exists now,” she says.

Anh Nguyen, Offering Table, 2024, from The Kitchen God Series

Anh Nguyen, Offering Table, 2024, from The Kitchen God SeriesAnh Nguyen

All rituals involve performance. After nearly a decade away from her home in Vietnam, Brooklyn-based photographer Anh Nguyen began evaluating the role of tradition in her life. “Once you take a tradition outside of its original context, it becomes inherently open to interpretation,” she says. Through her staged photographs in The Kitchen God Series, Nguyen shows the performance of cultural traditions refracted in new contexts. The title refers to a popular Vietnamese myth of three figures often placed in the kitchen to watch over the family. Nguyen made the photographs in the homes of Vietnamese people across New York. The resulting images articulate how each subject interprets and adapts their shared cultural traditions in unique ways. In constructing these whimsical commentaries, Nguyen realized she too took on the role of a Kitchen God. “The myth became a playground for me to explore the confines of identity through the exchange of reality and fiction, of myth and personal history,” she says.

Nathan Olsen, 2023, from the series Touchstone

Nathan Olsen, 2023, from the series TouchstoneNathan Olsen

Santa Maria del Oro is tucked into the western Mexican state of Jalisco. The Chicago-based photographer Nathan Olsen first visited his ancestral town to see family, and for the Catholic Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe celebration, but his exploration soon turned inward, prompting a deeper search. Olsen’s series Touchstone is an attempt to make meaning from the fragments of his mixed ancestry; the title refers to a black siliceous stone used to test the purity of metals, as well as the history of rich deposits of gold in the region. It also functions as a metaphor for his own mixed-race background. “Photographing and spending time in Santa Maria del Oro literally widens the idea of where I come from in a physical and spiritual sense,” says Olsen. His soft black-and-white images, captured with a view camera, give the impression of a place still crystalizing into memory—landscapes and tender domestic scenes where people are barely visible, or facing away. They are hands reaching both ways into time. As Olsen explains: “Exploring the land is an exploration of self.”

Obinna Onyeka, Untitled, 2024

Obinna Onyeka, Untitled, 2024Obinna Onyeka

Two distinct influences define Chicago-based Nigerian American photographer Obinna Onyeka’s visual language. “Fashion photography brings out a stylish boldness and a designer’s editorial sensibilities,” he says. “On the other hand, the family archive carries candid warmth, and a sense of nostalgic presence.” While Onyeka’s commercial portraits of athletes, artists, and broader cultural figures have been published by Nike, New Balance, Red Bull, and the New York Times, his latest project finds subjects closer to home. Interpersonal connection and the Nigerian immigrant experience inspire the title of his series Beyond Distance, and features family, friends, and community members of individual and cultural importance to Onyeka. Combining portraiture, photographs of traditional events, and personal testimonies, the ongoing series aims to present a mosaic of a rich and shared diasporic experience. “I want to make portraits of my friends and family that help us feel close, reflect on our diasporic culture, and deepen our bonds,” Onyeka says.

Andina Marie Osorio, Untitled (jahne in our home), 2023, from the series i’m so glad you’re here

Andina Marie Osorio, Untitled (jahne in our home), 2023, from the series i’m so glad you’re hereAndina Marie Osorio

“My work is based on other people’s images, things that are deeply personal to me and to my family,” says Andina Marie Osorio. Her series i’m so glad you’re here explores two tangential archives: that of her family , and her own queer photographs made on her Contax T2. “What makes an image queer?” she asks. The sitter? The photographer? Something within the image itself? Drawing upon influences such as Nan Goldin and Wolfgang Tillmans, Osorio’s photographs range from blurred and shadowy intimate moments to a still life of a just-removed IUD. When the work is viewed as an installation, these photographs mingle on the wall among their antecedents in the family archive, newly imbued with nostalgia. Metal sheets hang behind some of the images, which are all printed at different sizes to form a work of assemblage beyond each image alone, providing an alternate narrative—a queer family archive of her own.

Tanner Pendleton, Mik, 2023, from the series What Does Marble Think As It’s Being Sculpted?

Tanner Pendleton, Mik, 2023, from the series What Does Marble Think As It’s Being Sculpted?Tanner Pendleton

“Photography, to me,” says Tanner Pendleton, “feels like a never-ending exercise in speculation.” In What Does Marble Think As It’s Being Sculpted?, Pendleton explores the limits of photography and science in strongly lit black-and-white images. One set of photographs documents both real and pseudo-science; Pendleton’s interests range from physics to hypnotherapy to new-age spiritualism, but he sums up his work as finding the convergence between the outward search for the cosmos and the inward search for the self. Through exercises in Kirlian photography, which uses high-voltage electricity on film rather than a traditional camera and lens, Pendleton leans into the murky reality of alternative processes, reveling in the loss of control. To him, Kirlian photography is “a spiritual intervention of sorts.” Together, his documentary and experimental work form a wide-reaching, nearly universal questioning of truth. “Blending different formal conventions,” he says, “feels like an opportunity to take things out of context and create a sense of confusion between artifice and reality.”

Chris Perez, Self-Portrait with Flower, Guardarraya, Dominican Republic, 2023, from the series Dominican

Chris Perez, Self-Portrait with Flower, Guardarraya, Dominican Republic, 2023, from the series DominicanChris Perez

“I began to take photos as an attempt to learn how to be Dominican,” says Chris Perez. In 2021, during a visit to his father’s birthplace in the northern Cibao region of the Caribbean nation, the New York–based photographer remembered feeling like a foreigner. It was Perez’s first overseas photography trip, and he quickly realized how the camera could serve as a cultural bridge between a familiar and unfamiliar home. Dominican is an ongoing body of work made through several visits since that first experience. Perez’s photographs are suffused with a delicate palette—we are drawn in by the aged pink wall of a small palm-wood shack, or the soft brown of a dirt mound that contrasts the green landscape behind it. Each detail feels colored with the gentle curiosity of a distant cousin returning, each face opens a new story in a widening network. “It is as if photography has given me a way to reclaim something about myself,” says Perez.

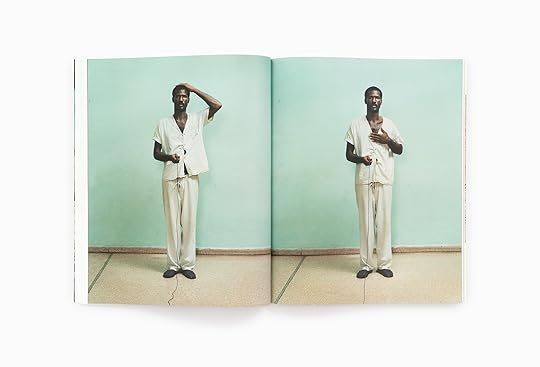

Mateo Ruiz González, Cameron (Pose Number One), 2023, from the series Humble

Mateo Ruiz González, Cameron (Pose Number One), 2023, from the series HumbleMateo Ruiz González

Mateo Ruiz González read about Humble School of Martial Arts in Bedford-Stuyvesant in a local Brooklyn news publication. He was moved by the story of its founder, Master Sabu Lewis, who has been a teacher and community pillar for decades, through his school’s financial hardships, COVID-19, and a recent relocation. Ruiz González saw in Lewis a figure that has made Brooklyn what it is, and one who is also endangered by the growing pressures of urban development. “For me, it is a matter of choosing where you stand,” says Ruiz González, who was born in Bogotá and immigrated to Brooklyn eleven years ago. “It’s important to tell the stories of the people that build community.” Humble is a portrait of a school that represents something bigger in a fight against displacement. Ruiz González’s use of a field camera lends his images—specifically his portraits—a candid and personal touch. “I think there’s no better way to photograph than to first make the person in front of the camera understand that there will not be a photograph without their stories,” he says.

Jennifer Sakai, No.1, 2023, from the series When We Return Home

Jennifer Sakai, No.1, 2023, from the series When We Return HomeJennifer Sakai

At first glance, the pairs of photographs that comprise Jennifer Sakai’s When We Return Home have an almost dreamlike connection. In each pair, the larger photograph of nature or quotidian domestic life dominates the space, yet offers an entry point to the postcard-sized archival family photograph alongside it. The calm quality of Sakai’s photographs belies the horrors within: a personal history of Japanese-American internment during World War II. After the war broke out, Sakai’s grandparents were removed from their homes in California and sent to a camp in Poston, Arizona. In fragments, Sakai shares a photograph of her uncles playing baseball in the camp, personal effects, and images from after the war, when the family relocated to the Midwest. The more recent photographs ground these moments in the present. (In one set, tree branches reach across the two images, tethering past to present.) The pairings make the process, in a sense, collaborative, says Sakai. “There was this unseen tether that was connecting their voice to my voice.”

Rachel Elise Thomas, All in the Family, 2022, from the series Crowded House

Rachel Elise Thomas, All in the Family, 2022, from the series Crowded HouseRachel Elise Thomas

Michigan-based interdisciplinary artist Rachel Elise Thomas is driven by a deep desire to honor her past. “I am collaborating with memory, a spirit, and my environment,” she says about her series Crowded House, which engages with her relationship to her family home in the suburbs of Detroit, where she moved in 1993. Drawing from her experience with collage, Thomas uses photography and projection to produce palimpsests of image and memory. The approach is direct and powerful; Thomas projects 4-by-6-inch family photographs onto the rooms of her home, and then captures the result with a digital camera. These rooms serve as both a place and prompt for her memories—which include birthdays, holidays, and homecomings—and give her family archive a new, glowing physicality. In this way, the series enacts both a resurrection and a reexamination. “These memories perpetually overlap,” says Thomas, “and depending on the image’s placement, the composition changes, and so does its narrative.”

Jaclyn Wright, Archives, I, 2022, from the series High Visibility (Blaze Orange)

Jaclyn Wright, Archives, I, 2022, from the series High Visibility (Blaze Orange)Jaclyn Wright

When Jaclyn Wright moved to Salt Lake City, in 2018, she says, “it was the first time that I could really visibly see the climate crisis playing out in real time.” In High Visibility (Blaze Orange), Wright photographs Western landscapes to explore the visual and material history of climate change, land expansion, and capitalism. Utah’s West Desert includes the rapidly drying Great Salt Lake, the Dugway Proving Ground, and various mineral extraction sites, but Wright focuses on the improvised gun ranges that dot the public land. “It’s this Hollywood Western mythology,” she says, “this idea of playing out that fantasy on this land that has been stolen, and is now public, is why those sites are so jarring.” Wright first collects objects and debris left behind at the gun ranges, makes photographs at each site, and then creates a collage in her studio, adding images from university and historical archives. Visually and conceptually dense, each piece forms a critical treatise on the built environment of the American West.

Artist statements by Eli Cohen and Varun Nayar.

September 20, 2024

The Japanese Women Who Transformed Photography

In her book Women Making Art, Marsha Meskimmon poses the question, “What new knowledge can women making art produce in terms of history, subjectivity, and aesthetics?” Studying the disparate examples of Yamazawa Eiko, Tokiwa Toyoko, Ishikawa Mao, Ushioda Tokuko, and Komatsu Hiroko, we can see how women and photography come together to “remake meaning in particular social situations and aesthetic encounters.” We understand and use Meskimmon’s idea of remaking meaning as a form of creative and critical world-building, a feminist practice that Sara Ahmed describes as seizing on the promise of “loud acts of refusal and rebellion as well as the quiet ways we might have of not holding on to things that diminish us . . . in the struggle for more bearable worlds.” Just as Ahmed describes feminism as a praxis for women to “live better in an unjust and unequal world,” to “create relationships with others that are more equal,” and to “keep coming up against histories that have become concrete, histories that have become solid as walls,” so, too, can photography be a means for women to claim the world as their own. While chronicling a history of Japanese women photographers akin to the scope and depth of the canon of male photographers may not be possible, nor is it our goal, we have found that the stories uncovered by doing this work not only diversify the canon but also reveal ever more absences and gaps in the ways that photographic history has been written in the first place.

Domon Ken, Saiki Sachiko and Yamazawa Eiko in Yamazawa’s studio, from “Kamera ni ikiru josei” (Women who make a living with cameras), Photo Times, March 1940

Domon Ken, Saiki Sachiko and Yamazawa Eiko in Yamazawa’s studio, from “Kamera ni ikiru josei” (Women who make a living with cameras), Photo Times, March 1940  Yamazawa Eiko, Yamamoto Yasue in character as Sonya in Anton Chekov’s Uncle Vanya, ca. 1943–44

Yamazawa Eiko, Yamamoto Yasue in character as Sonya in Anton Chekov’s Uncle Vanya, ca. 1943–44 From 1926 to 1928, Yamazawa Eiko worked in San Francisco as Consuelo Kanaga’s studio assistant and in New York with the American Hungarian fashion photographer Nickolas Muray learning the trade of studio operation and experiencing how portrait photography offered a space for experimentation and innovation. Following in the footsteps of her mentor, Yamazawa became the first woman to open a photography studio in Osaka and was often represented in Japanese newspapers and magazines as an example of the shokugyō fujin (white-collar professional woman). Yamazawa wrote in 1935, “There can be no liberation of women while they are hired by men and always work in worse conditions than men. A bright future is promised only when as many women as possible learn their own mission to live and discover their jobs.” Yamazawa’s self-representation as a business owner, mentor, and artist demonstrates how she made meaning not only with her images, but also through how she decided to live her life. Operating her own studio was a way to intervene in the discourses and social restraints around women’s labor, and her success speaks to how photography offered women opportunities to build community through their cameras.

After her return from the US, Yamazawa moved her studio to the newly opened Sogo department store in Osaka, a modern space that she transformed into an important site to mentor budding women photographers. In 1939, Keizai Magajin (Economics magazine) featured Yamazawa as a successful business owner who made a name for herself by popularizing a new photographic portraiture technique the writer called shiruetto geijutsu shashin (silhouette-art photography). The magazine held her up as a community leader and builder, citing that she had by then trained at least thirty women in her studio, many of whom went on to open their own studios. Saiki Sachiko, one such student, opened her own studio in Kyoto that her student Saeki Keiko in turn operates to this day. That these women earned a living through the studio differentiates their work from Ladies’ Camera Club in Tokyo (1937–39), whose members were led by the alpinist Murai Yoneko and included architect Tsuchiura Nobuko and novelist Muraoka Hanako. Still, the prevalence of women who made a living through photography and women who organized photography clubs demonstrates a commitment to creating work places and social organizations centered on fostering opportunities for economic emancipation and visual expression that they did not have access to elsewhere.

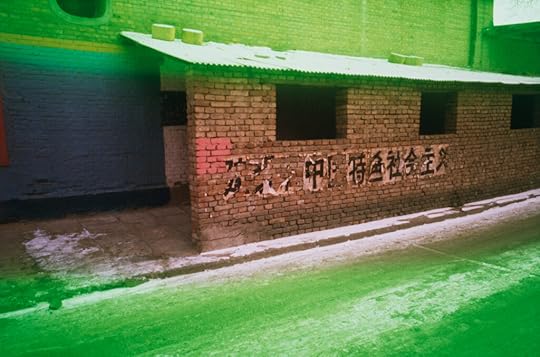

Cover of Shashin Shūhō (Pictorial Weekly Report) magazine, June 1940, featuring an image by Sasamoto Tsuneko

Cover of Shashin Shūhō (Pictorial Weekly Report) magazine, June 1940, featuring an image by Sasamoto Tsuneko  “Ashita o tsukuru hitobito” (The people who make tomorrow), Fujin Koron (Women’s Review) magazine, April 1956, featuring a photograph by Fujimoto Shihachi

“Ashita o tsukuru hitobito” (The people who make tomorrow), Fujin Koron (Women’s Review) magazine, April 1956, featuring a photograph by Fujimoto Shihachi As it became increasingly difficult and unsafe to live and work in urban centers during the Fifteen-Year War (1931–1945), Yamazawa moved to Shinshu (present-day Nagano), where she repurposed a tofu mill as her studio. Whether making keepsake portraits for soldiers and their families or producing intimate portraits of her friend and muse, the actor Yamamoto Yasue, Yamazawa continued to use portraiture as a means for survival and as a creative refusal of the status quo. In one example, she collaborated with Yamamoto to use portrait photography to capture and communicate the ethos of particular plays and characters performed by the actor. In a visual tradition in which women’s bodies are often used as symbols of national meaning on the one hand and erotic props for the photographer’s homo-socialization on the other, Yamazawa reclaimed the portrait as a form of partnership with her subject. These portraits are documents of women who existed vividly, if briefly, for Yamazawa as their only audience at the height of armed conflict.

“La Jeune Fille au Travail,” in Images du Japon magazine, “La Vie de la Femme,” 1943, featuring a portrait of Sasamoto by an unknown photographer

“La Jeune Fille au Travail,” in Images du Japon magazine, “La Vie de la Femme,” 1943, featuring a portrait of Sasamoto by an unknown photographer  Page from an issue of Images du Japon magazine, “La Vie de la Femme,” 1943, featuring photographs by Sasamoto Tsuneko

Page from an issue of Images du Japon magazine, “La Vie de la Femme,” 1943, featuring photographs by Sasamoto Tsuneko Though seeking to create a photographic practice that was their own, ulitamately the intimate photographic exchange between Yamamoto and Yamazawa could not escape the time and space of total war. As such, what does it mean to read them alongside photographs taken in support of the war that Yamazawa and Yamamoto sought to flee from? If Yamazawa saw in portraiture the potential to build her own photographic world around an all-women staffed studio, her contemporary Sasamoto Tsuneko seized the opportunity presented by war to insert herself into the male-dominated world of reportage, famously making claim to the title of Japan’s “first female photo-journalist.” Significantly, she achieved this status only because others interpreted her wartime propaganda photographs as “documentary photographs.” Sasamoto’s work is worth considering to understand how war provided new spaces for women to take up the camera, but that their photography was recognized as service to the wartime state. For instance, Sasamoto’s photograph of three young women singing patriotic songs became what is possibly the first photograph by a woman on the cover of a major magazine, in this case, Shashin Shūhō (Photographic Weekly Report), a propaganda mouthpiece of the Ministry of Information. Images du Japon, another publication produced by the Japanese empire, used Sasamoto’s photographs of Japanese women in the metropole as aspirational symbols for imperial subjects abroad. The same magazine published a photograph of Sasamoto as one such model of the modern working woman for viewers in Southeast Asia. Thus, Sasamoto both created and was the model of idealized images of women at play and work who supported the wartime goals of the Japanese empire. Her work from this era demonstrates how, in the context of total war, men and women alike developed photography careers by contributing to the state, just as the state sought to control their bodies and activities. Celebrating Sasamoto as Japan’s first woman photojournalist while failing to account for the dependency of this legacy on her war-time work perpetuates an ingrained pattern in Japanese photographic history—namely, the fact that most of the photographers who have entered the canon for their work documenting Japan’s war recovery, had survived in the preceding years by working in support of the wartime state.

“Shokuba no ichinensei” (First years at the workplace), Fujin Koron (Women’s Review), June 1957, featuring photographs by Tokiwa Toyoko

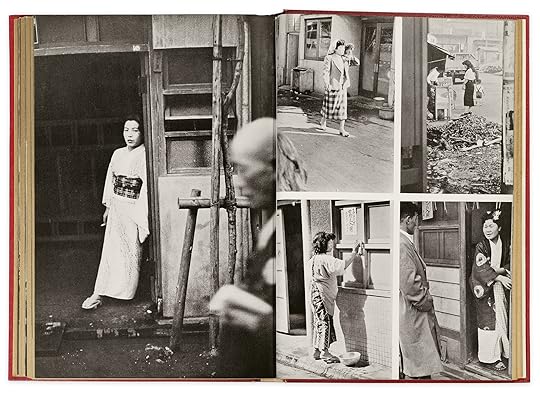

“Shokuba no ichinensei” (First years at the workplace), Fujin Koron (Women’s Review), June 1957, featuring photographs by Tokiwa Toyoko  Tokiwa Toyoko, spread from Kiken na adabana (Dangerous poison flowers), 1957

Tokiwa Toyoko, spread from Kiken na adabana (Dangerous poison flowers), 1957 In the postwar era, women’s photographic labor was represented in the Japanese mass media as flexible, temporary labor—a field one might participate in until marriage. Those who did take up photography as a full-time career, such as Tokiwa Toyoko, were often described as exceptional cases and reported on with much curiosity by photography and women’s magazines. Tokiwa became one of the most well-known women photographers of the 1950s for her best-selling book, Kiken na adabana (Dangerous poison flowers, 1957), which details her journey into the field of photography and her dedication to photographing women at work. Tokiwa photographed women in the Tokyo and Kanagawa areas, making visible their labor and commenting on the wide-spread view of them as anomalies. They were varied in their professions, including receptionists, fashion designers, bus drivers, sandwich-board wearers, wrestlers, pearl divers, nude models, and sex workers. Women’s magazines such as Fujin Kōron (Women’s Review) published representations of Tokiwa as an inspirational figure for the generation of women photographers who began to photograph in the 1950s. It was also the main place where Tokiwa’s series Hataraku josei (Working women) was published. This work is another example of how the placement of photographs in women’s magazines, rather than photography publications, has meant that much of this series has long been disregarded by photo historians.

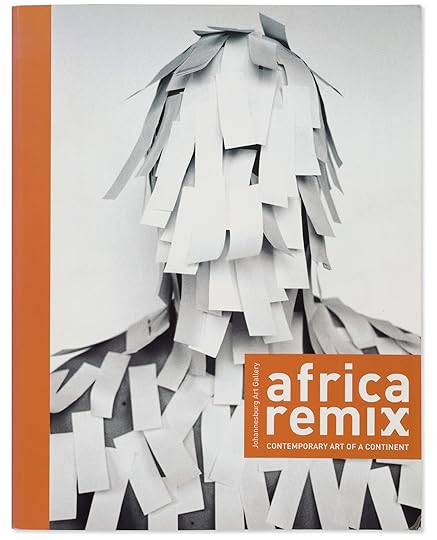

I’m So Happy You Are Here: Japanese Women Photographers from the 1950s to Now 75.00 A critical and celebratory counter-narrative to what we know of Japanese photography today.

I’m So Happy You Are Here: Japanese Women Photographers from the 1950s to Now 75.00 A critical and celebratory counter-narrative to what we know of Japanese photography today. $75.00Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

I’m So Happy You Are Here: Japanese Women Photographers from the 1950s to NowEdited by Pauline Vermare and Lesley A. Martin. Text by Takeuchi Mariko, Carrie Cushman, and Kelly Midori McCormick. Contributions by Marc Feustel and Russet Lederman. Photographs by Hara Mikiko, Ishikawa Mao, Ishiuchi Miyako, Katayama Mari, Kawauchi Rinko, Komatsu Hiroko, Kon Michiko, Nagashima Yurie, Narahashi Asako, Ninagawa Mika, Nishimura Tamiko, Noguchi Rika, Nomura Sakiko, Okabe Momo, Okanoue Toshiko, Onodera Yuki, Sawada Tomoko, Shiga Lieko, Sugiura Kunié, Tawada Yuki, Tokiwa Toyoko, Ushioda Tokuko, Watanabe Hitomi, Yamazawa Eiko, and Yanagi Miwa. Designed by Ayumi Higuchi.

$ 75.00 –1+$75.00Add to cart

View cart Description A critical and celebratory counternarrative to what we know of Japanese photography today.I’m So Happy You Are Here presents a much-needed counterpoint, complement, and challenge to historical precedents and the established canon of Japanese photography. This restorative history presents a wide range of photographic approaches brought to bear on the lived experiences and perspectives of women in Japanese society. Editors Pauline Vermare and Lesley A. Martin, curator and writer Takeuchi Mariko, and photo-historians Carrie Cushman and Kelly Midori McCormick provide a critical historical and contemporary framework for understanding the work in three richly illustrated essays. Additional context is provided by an in-depth illustrated bibliography by Marc Feustel and Russet Lederman, and a selection of key critical writings from leading Japanese curators, critics, and historians such as Kasahara Michiko, Fuku Noriko, and others, many of which will be published in translation for the first time. While this book does not claim to be fully comprehensive or encyclopedic, its goal is to provide a solid foundation for a more thorough conversation about the contributions of Japanese women to photography—and an indispensable resource for anyone interested in a more robust history of Japanese photography.

Made possible in partnership with the Rencontres d’Arles and Kering.

Format: Hardback

Number of pages: 440

Number of images: 518

Publication date: 2024-09-17

Measurements: 8.25 x 11 inches

ISBN: 9781597115537

Pauline Vermare is the Phillip and Edith Leonian Curator of Photography, Brooklyn Museum. She was previously the cultural director of Magnum Photos NY, and a curator at the International Center of Photography, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation, Paris.

Lesley A. Martin is executive director of Printed Matter. Previously, she was the creative director of Aperture, where she served as editor on more than one hundred fifty books on photography, and was the founding publisher of The PhotoBook Review.

Takeuchi Mariko is a photography critic, curator, and professor at Kyoto University of the Arts. Previously, she served as visiting researcher at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, and at the National Museum of Art, Osaka.

Carrie Cushman is the Edith Dale Monson Gallery Director and Curator at the Hartford Art School. She holds a PhD in art history from Columbia University and is a specialist in postwar and contemporary art and photography from Japan. With Kelly Midori McCormick, she was principal investigator and codirector of the website Behind the Camera: Gender, Power, and Politics in the History of Japanese Photography.

Kelly Midori McCormick is an assistant professor at the University of British Columbia. She received her PhD from University of California, Los Angeles, and an MA in East Asian languages and cultures from Columbia University. With Carrie Cushman, she was principal investigator and codirector of the website Behind the Camera: Gender, Power, and Politics in the History of Japanese Photography.

Marc Feustel is a Paris-based independent curator, writer, and editor specializing in Japanese photography.

Russet Lederman is a writer, editor, and photobook collector based in New York. Previously, she taught art writing at the School of Visual Arts and cofounded 10×10 Photobooks.

Related Content Essays The Luminous Openness of Rinko Kawauchi’s Photographs

Essays The Luminous Openness of Rinko Kawauchi’s Photographs  From the Archive Ishiuchi Miyako’s Chronicles of Time and History

From the Archive Ishiuchi Miyako’s Chronicles of Time and History  Featured 7 Essential Japanese Photobooks

Featured 7 Essential Japanese Photobooks Tokiwa’s approach to photographing working women transformed over time, specifically in response to her experiences in red-light districts. When Tokiwa’s exhibition, named for the Hataraku josei series, opened in 1956 at the Konishiroku Gallery in Tokyo, male critics noted that these were photographs that could have been made only by a woman due to the nature of the subject matter. Tokiwa expressed ambivalence over the suggestion that women could make exhibition-worthy photographs only when given the opportunity to enter spaces that male photographers could not. Tokiwa had first photographed sex workers in the red-light district of Yokohama by spying on them from behind bathhouses, through the windows of okonomiyaki shops, and by concealing her camera behind a doctor’s white coat as she pretended to be a nurse in a clinic treating STDs. Hiding, as she later recounted in her bestselling autobiographical photobook, “on the second floor like a hunter taking aim at deer from a blind,” she photographed street scenes in front of unlicensed dealers of Philopon, or methamphetamine. Many of her images, she wrote, reflect the physical, social, and psychological distance she initially felt from those she photographed as she used techniques of photojournalism. Dressing in skirts and geta to blend in with the women, she recounted how “caught in extreme nervousness, divided between fear and skill, I walked in search of my prey (the photographic subject).” Over time, however, Tokiwa’s photographs shifted to reflect how she built relationships with the women of the red-light districts and, through this connection, photographed them from a place of empathy in an attempt to change the popular perception of them as symbols of society’s ills. No longer a photographer who lay in wait to capture an unaware subject, she became a woman faced with the difficulty of making a living in a country recovering from the devastation of total war.

Ishikawa Mao, Kin, Koza (present-day Okinawa City), Okinawa Prefecture, 1975–77, from the series Akabanaa (Red Flower)

Ishikawa Mao, Kin, Koza (present-day Okinawa City), Okinawa Prefecture, 1975–77, from the series Akabanaa (Red Flower)  Ishikawa Mao, Kin, Koza (present-day Okinawa City), Okinawa Prefecture, 1975–77, from the series Akabanaa (Red Flower)

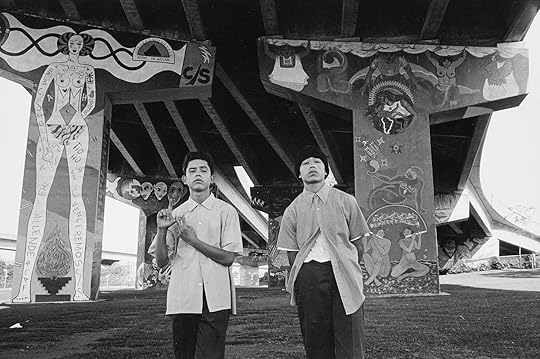

Ishikawa Mao, Kin, Koza (present-day Okinawa City), Okinawa Prefecture, 1975–77, from the series Akabanaa (Red Flower) Ishikawa Mao saw herself from the start of her career in the women who worked the bars around the American military bases in Okinawa—the subject of her early photography projects, which resulted in the photobooks Atsuki hibi in Kyanpu Hansen!! (Hot days in Camp Hansen!!, 1982) and Firipin (Philippines, 1989). As Ishikawa describes her process: “This is not an infiltration report. I did not intend to take ‘sneak-peek photo’ on the sidelines. I am neither a magazine photographer nor a photojournalist. I started taking photos by involving myself in the situation. It is not only a documentary but also my own emotional record. So working at a bar for African American personnel is important for me. I decided to become a lady in Kin Town.” Even including herself in some of the photographs, Ishikawa adopted an approach that differentiates her work from that of many of her teachers and contemporaries who, though questioning the role of the photographer in creating a photographic document, most often did not see themselves as making photographs from within their own communities. Ishikawa was drawn to these women, stating: “There was a freedom to say what you wanted and to live your own life. That is why these women lived freely; they were joyful, powerful, and strong. Before I knew it I had become one of them.”

Throughout her career, Ishikawa photographed from inside the worlds she inhabited, often accompanying members of Okinawan communities to their home countries to better understand how Okinawa was a point of connection for people across the world. Ishikawa’s extended work depicts the intimacy that emerged during American militarization as a trans-Pacific event, shaping the lives and identities of Okinawan women and men, Black American military men, and Filipina communities. These raucous and tender portraits speak to the “reciprocal solidarity” felt between Okinawans and Black US servicemen in the 1980s. Ishikawa has continued to photograph the American military’s ongoing—at times violent—presence in Okinawa, bringing into focus new angles on the affected communities.

Ishikawa Mao, Manila, the Philippines, 1989, from the series

Philippine

Dancers

Ishikawa Mao, Manila, the Philippines, 1989, from the series

Philippine